Abstract

Recent trends in formative assessment seek innovations to link assessment, teaching, and learning characterized as assessment for learning. This new assessment stance has rarely been studied in the context of English language teaching. Hence, there is a need for research to shed light on assessment for learning practices. The current study set out to investigate Iranian EFL teachers’ perceptions of two salient elements of assessment for learning namely scaffolding and monitoring practices as a function of their demographic characteristics. The study employed a triangulation mixed methods approach to provide a detailed picture of EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning practices. To this end, 384 Iranian EFL teachers completed a self-report assessment for learning questionnaire consisting of 28 items on a Likert scale. Likewise, semi-structured interviews and classroom observations were conducted. The qualitative results substantiated those of the questionnaire manifesting that the absolute majority of EFL teachers perceived the use of assessment for learning as beneficial and effective. However, slight discrepancies were found in classroom observations in terms of monitoring practices of assessment for learning. Further, EFL teachers’ perceived monitoring and perceived scaffolding of assessment for learning practices were not significantly different with regard to their years of teaching experience, academic degree, and proficiency levels taught. This study provides insights into the promotion of assessment for learning culture among EFL teachers. It also carries important implications for teacher educators and researchers to explore new avenues to integrate assessment for learning into instruction as a means of enhancing student learning.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

There is ample evidence corroborating that assessment for learning enhances student learning. Informed of the integration of assessment, instruction, and learning as central to assessment for learning, EFL teachers have turned the spotlight on the necessity of employing assessment for learning practices in the classroom. The authors in this study investigated Iranian EFL perceptions of two salient cornerstones of assessment for learning practices namely monitoring and scaffolding. Having collected the data through a self-report questionnaire, semi-structured interviews, and classroom observations, the authors concluded that the absolute majority of EFL teachers assigned great values to assessment for learning practices. Also, EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning did not vary as a function of their years of teaching experience, academic degrees and the proficiency levels taught.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests

1. Introduction

Recently, formative assessment practices have been refined into a learner-directed approach conceptualized as assessment for learning (henceforth, AFL), a collaborative, learning-oriented instruction (Colby-Kelly & Turner, Citation2007) wherein assessment and learning are inextricably intertwined with the overriding aim of nurturing student learning (Davison & Leung, Citation2009; Stiggins, Citation2008). To give new assessment paradigm a momentum, Carless (Citation2015) and Sambell, McDowell, and Montgomery (Citation2012) explored practical assessment approaches so as to advance student learning. Similarly, in the light of the current trend in assessment, researchers in the field of language education have attempted to use high -stakes tests formatively to refine language teaching and learning in the classroom (Wei, Citation2017). This assessment culture embraces a move from testing for testing’s sake to assessment for the sake of learning (Elizabeth, Citation2017).

Performed informally as part of teachers’ individual teaching styles, AFL is embedded in all facets of the teaching and learning process (Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall, & Wiliams, Citation2003). In essence, as Hargreaves (Citation2005) puts forth, assessment for learning is an effective teaching strategy that promotes personalized learning. Central to AFL is the idea that teachers integrate teaching, learning, and assessment to reap the maximum benefits for learners (Lee, Citation2007).

The underlying themes of AFL in most studies center around four major categories: 1) classroom questioning techniques, 2) enhancing self- assessment and peer -assessment, 3) setting learning goals and criteria, and 4) offering feedback/feedforward (Assessment Reform Group, Citation2002; Black & Wiliam, Citation1998). These themes were encapsulated in two elements namely scaffolding and monitoring by Pat-El, Tillema, Segers & Vedder (Citation2013). In practice, teachers perform assessment for learning formally and informally by means of monitoring and scaffolding practices which work in tandem with classroom instruction to enhance student learning (Black et al., Citation2003; Black & Wiliam, Citation1998; Davison & Leung, Citation2009).

Notwithstanding a plethora of studies regarding AFL in mainstream education, there is a paucity of research in the realm of language teaching (Rea-Dickins, Citation2004). Nonetheless, two studies on AFL in the context of language teaching (e.g., Hasan & Zubairi, Citation2016; Oz, Citation2014) delved into EFL teachers’ scaffolding and monitoring practices of AFL and investigated such practices in relation to their demographic characteristics. Particularly absent in the literature is a study on EFL teachers’ AFL practices with regard to variables such as teachers’ academic degree and proficiency levels taught. Inspired by these gaps, we made an attempt to delve into EFL teachers’ perceptions of AFL with respect to monitoring and scaffolding practices. More specifically, the following research questions are addressed:

(1) Are there significant differences in Iranian EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning practices in terms of academic degree, years of teaching experience, and language proficiency levels taught?

(2) What perceptions do Iranian EFL teachers hold about assessment for learning?

2. Review of literature

2.1. Assessment for learning

“Assessment for learning is the process of seeking and interpreting evidence for use by both learners and their teachers to decide where the learners are in their learning, where they need to go, and how best to get there”(Assessment Reform Group, Citation2002, p.2). Indeed, it is the process of analyzing classroom assessment data to improve rather than to check on student learning (Stiggins, Citation2002b). According to Stiggins (Citation2006), AFL is the application of formative assessment and its results which serve as an instructional intervention with the intention of fostering learning. It is then for students to learn and for teachers to plan more effective instruction (White, Citation2009). As part of teachers’ everyday practice in the classroom, AFL helps teachers identify students’ needs, provide them with feedback, and plan the next steps in teaching (Stiggins, Arter, Chappuis, & Chappuis, Citation2004). In an AFL context, classroom practices emanate from teachers’ intuition (Poehner & Lantolf, Citation2005). It is an intrinsic aspect of an assessment culture hinging on scaffolding which drives instruction in support of student learning (Black & Wiliam, Citation1998). Teachers in an AFL -styled approach promote learner autonomy by involving learners in reflecting on self-sufficiency, goals, and motivation (Tsagari, Citation2016). Besides, as a developmental process, AFL boosts learners’ motivation and self-esteem (Pattalitan, Citation2016).

Grounded in sociocultural paradigm, assessment approaches including assessment for learning, formative assessment, teacher-based assessment, and dynamic assessment share common orientations to a great degree. Such assessment modes work hand in hand with assessment of learning otherwise known as summative assessment serving different purposes (Davison & Leung, Citation2009). However, AFL and formative assessment are seen as distinct (Green, Citation2013). One important distinction between the two terms is that the former is characterized by descriptive feedback, while the latter provides evaluative feedback to learners (Stiggins, Citation2002a).

2.2. Monitoring and assessment for learning

Monitoring lies at the heart of informal assessment and learning assisting the teacher in evaluating how instruction is going and what needs to be done when guidance is required (Wragg, Citation2004). Hargreaves (Citation2005) noted that in AFL, the teacher monitors learners’ achievement by providing them with feedback and by keeping track of how they learn. Monitoring entails assessment practices centering on feedback and self-monitoring intended to maximize learning (Pat‐El et al., Citation2013). Assessment practices highlighting learners’ strengths and weaknesses in learning are fundamental to monitoring (Lee & Mak, Citation2014). Monitoring is a means of examining student learning progress with the intention of stimulating learner self-monitoring to identify challenges and opportunities which optimize learning (Pat-El, Tillema, Segers, & Vedder, Citation2015). Indeed, AFL aims to monitor learner progress toward an intended goal and to fill the gap between a learner’s current level of understanding and the desired outcome (Clark, Citation2012). During AFL, students are taught to improve their performance and to monitor their own progress over time (Stiggins, Citation2005). To monitor their learning, teachers involve learners in self-reflection practices (Chappuis, Stiggins, Arter, & Chappuis, Citation2005). Active classroom-level monitoring entails practices focusing on setting high standards or success criteria, holding students responsible for their work, being clear about expectations, and providing immediate feedback (Cotton, Citation1988). During AFL, teachers monitor learners by observing and assessing their learning over time. Then, they interact with students in different ways. For example, by encouraging them to reflect on how to improve their language learning processes and by discussing the progress they have made in learning (Oz, Citation2014). Monitoring practices are premised on metacognitive strategies as cornerstones of assessment (Berry, Citation2008). Likewise, monitoring involves practices centering on self-reflection, self- monitoring, and learner autonomy.

2.3. Scaffolding and assessment for learning

Scaffolding is characterized as the temporary assistance given by teachers to help students learn how to perform a task so that they would later be able to perform a similar task on their own (Gibbons, Citation2002). Some scholars perceive that the assistance given to learners while completing a task can develop their zone of proximal development (ZPD). This is, in reality, a development-oriented approach (Poehner, Citation2008). In Vygotsky’s view (Citation1978), ZPD refers to the gap between the actual development level during independent task performance and the potential development level as determined by guided and collaborative performance. This gap or ZPD is accurately gauged by AFL (Heritage, Citation2007). Indeed, assessment for learning and scaffolding are strategies through which teachers enhance learning in the ZPD. During AFL as an interactive process, teachers make learners activate their ZPD and move them forward to the next step in their learning (Shepard, Citation2005). As the sine qua non of classroom interactions, scaffolded feedback provides learners with ZPD-oriented assistance which speeds up development (Rassaei, Citation2014).

On the other hand, other scholars view scaffolding as an effective teaching strategy performed for the purpose of providing assistance to learners which is a task-focused approach to classroom assessment (Poehner, Citation2008). In this sense, scaffolding embodies practices enabling learners to find out the areas they need to improve (Pat-El et al., Citation2013; Stiggins, Citation2005). Scaffolding is a collaborative and interactional process by which the teacher provides assistance to the student in the form of hints, encouragement, and cognitive structures to carry out a particular learning task with explicit learning goals (Joshi & Sasikuma, Citation2012). In other words, scaffolding is a classroom interaction wherein learning goals and evaluation criteria are shared (Pat‐El et al., Citation2015). It embraces instruction-oriented processes associated with learning goals and classroom questioning (Pat‐El et al., Citation2013). Such scaffolds are mechanisms to perform assessment for learning by teachers with a view to assisting students to promote their understanding and to take charge of their learning (Joshi & Sasikumar, Citation2012). An important hallmark of scaffolding practices is feed-up. According to Frey and Fisher (Citation2011), feed-up ensures that learners understand the purpose of the task, learning goals, and evaluation criteria.

2.4. Studies on AFL in the context of English language teaching

A review of the literature indicates that few studies have investigated assessment for learning in the context of language teaching. Black and Jones (Citation2006) studied how to put AFL into practice in the context of language learning and teaching in primary/secondary language schools in England.

Colby (Citation2010) examined the impacts of employing AFL practices in an L2 classroom setting where AFL principles were implemented in two pre-university English for academic purposes classes. The results indicated some evidence of the assessment bridge. The results also demonstrated that the implementation of AFL procedures in language teaching classrooms might enhance student learning.

In a study by Oz (Citation2014), Turkish teachers’ practices of AFL were explored in the context of English as a foreign language. He also studied their AFL practices as a function of variables including years of teaching experience, gender, and public vs. private school context. Although EFL teachers in his study showed high levels of perceived monitoring (82.86%) and perceived scaffolding (86.94%) of AFL practices, significant differences were observed in their perceptions and practices of assessment for learning mainly in their monitoring practices with regard to years of teaching experience, gender, and the context of teaching (private vs. public school).

Hasan and Zubairi (Citation2016) conducted a similar study to identify monitoring and scaffolding practices of AFL among primary school English language teachers in Malaysia. Based on the results of their study, most AFL practices were frequently implemented by English teachers in primary school classrooms.

Finally, Gan Liu and Yang (Citation2017) explored prospective Chinese EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning practices in terms of their learning approaches. They found a significant positive correlation between their AFL perceptions and their propensity to employ an achieving or in-depth approach to learning.

3. Methodology

A triangulation data collection approach was employed to address the objectives of the current study. Quantitative data including independent and dependent variables were collected through a questionnaire and were then analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Also, a series of semi-structured interviews along with nonparticipant classroom observations were conducted for further elaboration of EFL teachers’ perceptions of AFL.

3.1. Instruments

Three different instruments were employed in this study for triangulation. The instrument for the quantitative phase of the study was a questionnaire adapted from Pat-El et al. (Citation2013). They constructed and validated the English translation of the instrument which was originally in Dutch in a recent study. It consists of 28 statements gauging two major constructs of AFL namely perceived monitoring (16 items) and perceived scaffolding (12 items) on a 5-point (ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree) Likert scale. The questionnaire consists of the most important themes of AFL in the literature.

In addition, to get a detailed picture of EFL teachers’ perceptions of AFL practices, the researchers conducted semi-structured interviews with 40 EFL teachers to delve into their perceptions of AFL practices. The semi-structured questions were given as Appendix A.

Classroom observation was used as the third instrument of the study to explore EFL teachers’ actual AFL practices. To make the observations more structured, we designed a non-participant observation checklist in accordance with the AFL questionnaire of the present study as well as 10 principles of AFL (Assessment Reform Group, Citation2002). The checklist is composed of two parts. The first section captures demographic characteristics of EFL teachers and the second part consists of 30 AFL practices on a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from none to high). The checklist was reviewed and approved by a panel of three experts in the field of applied linguistics. Noteworthy to mention is that the checklist was pilot-tested during two observation sessions. The reliability of the checklist administered to 38 EFL teachers turned out to be .801.

3.2. Sampling of quantitative phase

A pool of 384 Iranian EFL teachers (199 females and 185 males) constituted the sample size of the quantitative phase of the study selected according to convenience sampling. The participants were EFL teachers currently teaching English in language institutes as well as high schools across the country.

As the number of EFL teachers in Iran is unknown, the sample size was determined as 384 based on Krejcie and Morgan’s Table (1970) considering the 95% of the level of confidence and 0.05 degree of accuracy. Considering educational setting, 203 EFL teachers were teaching English in language institutes and 181 were EFL teachers in high schools. The age range of the participants was 25 to 60 years. Regarding their academic degrees, 135 had bachelor degrees, 169 held master degrees and 80 were Ph.D. candidates or Ph.D. holders. Furthermore, all the participants studied English related fields. In terms of teaching experience, the sample included five categories: less than 5 years (n = 82), 6 −10 years (n = 80), 11–15 years (n = 68), 16–20 years (n = 77) and more than 20 years (n = 77). As for proficiency levels taught, 99,143,142 EFL teachers were teaching elementary, intermediate, and advanced levels, respectively.

3.3. Sampling of qualitative phase

A sample of 40 EFL teachers (12 males and 18 females) was selected purposefully based on maximum variation sampling from among the questionnaire respondents who expressed willingness to participate in semi-structured interviews. Based on Dornyei (Citation2007), maximum variation sampling helps researchers identify the variation within the participants. To establish maximum variation sampling, the researchers selected EFL teachers with various educational, teaching experience backgrounds, and proficiency levels taught. The age range of the interviewees was 27 to 55 years. 25 participant teachers were selected from the provinces of Tehran and Shiraz where they were easily accessible to the researchers. The remaining 15 were from other provinces of Iran who took part in a phone interview.

Concerning the classroom observation, 38 EFL teachers (17 females and 21 males) were selected based on maximum variation sampling from among the respondents to the questionnaire. The age range of the interviewees was 25 to 58 years. Table shows the demographic characteristics of EFL teachers in the interviews and classroom observations.

Table 1. EFL teachers’ demographics in interviews and classroom observations

3.4. Data-collection procedures

The data collection method for the quantitative phase was in the form of a questionnaire administered on social media network Telegram. Using Telegram for completing the questionnaire could save time and capture a wide range of EFL teachers in geographically diverse locations in Iran. A questionnaire invitation together with a link to the survey was forwarded to EFL teachers who were subscribers of different Telegram groups of EFL teachers working in language institutes as well as high schools. By clicking the link to proceed to the survey questions, EFL teachers consented that they were willing to participate in the study. It took them 5 minutes to complete the questionnaire. The data collection took place over a period of 10 months starting from June 2017 and ending in April 2018.

Also, semi-structured interviews were employed to cross-check the results of the quantitative analyses of the AFL questionnaire. Interviews, however, provide rich evidence by probing deeply into individuals’ perceptions (Richards, Citation2009).

To preserve confidentiality, we employed T1 (Teacher 1), T2… T40 to number transcripts. The interviews were performed in EFL teachers’ offices and their consent was obtained to audiotape the interviews. As some teachers were not easily accessible, we interviewed 15 EFL teachers on the phone. Also, informed consent was obtained to record their voices. The interviews were carried out in the participants’ native language (Persian). Interview questions were aimed at investigating EFL teachers’ perceptions of AFL and their current AFL practices. Each interview took approximately 15 to 20 minutes.

To gather data about EFL teachers’ actual AFL practices, we conducted 38 sessions of classroom observations. The classroom observations were conducted at 10 language institutes and high schools in Boushehr and Tehran provinces where it was easier for the observer to access EFL teachers and to agree on a classroom observation schedule. Having obtained permissions of language institute supervisors and EFL teachers, one of the researchers observed each class for one hour during when he filled out the observation checklist.

3.5. Piloting the questionnaire

Firstly, the questionnaire was pilot-tested on 50 EFL teachers who were identical to the target respondents of the study to fine tune the final version. They were not included in the final sample. The internal consistency was examined using Cronbach’s alpha for the whole instrument (α = .857) as well as the two subscales namely perceived monitoring (α = .826) and perceived scaffolding (α = .778). As Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .70 or higher reflects a good degree of reliability (Salkind, Citation2007), the reliability coefficients obtained were considered high.

3.6. Reliability of the questionnaire

As shown in Table , the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient) of the entire instrument was.87. Also, the internal consistency of the perceived monitoring and the perceived scaffolding turned out to be .86 and .84, respectively.

3.7. Data analysis

Statistical data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 for accurate and quick statistical analyses to address the research questions formulated previously. Descriptive and inferential statistics were computed to analyze the data collected.

Concerning the semi-structured interviews, thematic analysis was deployed to analyze main patterns within the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Dornyei, Citation2007). The interview data were first transcribed. In the next step, the data were repeatedly reviewed and key terms and phrases were coded. The codes were analyzed on a semantic level and were collated to form themes and sub-themes. Next, the recurrent themes were flagged and refined several times. In the light of the focus of the study and the literature review, final themes and names were generated.

It is noteworthy to mention that the interviews were coded and analyzed in Persian. Also, for the purposes of this study, emerging themes and sub-themes, along with exemplary quotes were translated into English by one of the researchers. Attempts were made to translate interviewees’ responses as accurately as possible to retain the original meaning. Then, a professional English translator checked the English translations for accuracy. The original exemplary quotes reported in this study were given as Appendix B.

The classroom observation checklists were analyzed quantitatively to identify the extent to which AFL practices were implemented by EFL teachers.

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory factor analysis

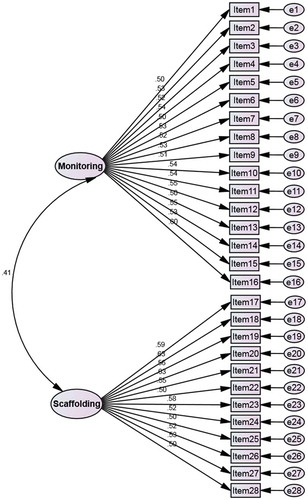

A confirmatory factor analysis was run to examine the extent to which the model fitted the questionnaire data of Iranian EFL teachers’ monitoring and scaffolding practices of assessment for learning. In confirmatory factor analysis, the measurement model is used to determine a priori the number of latent variables and their associated indicators (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Citation2010). The confirmatory factor analysis was performed via AMOS Graphics 24 and the maximum likelihood estimation method was computed to analyze the data.

4.2. The overall model fit

To check whether the model was appropriate for Iranian EFL context, different goodness-of-fit indices were used. As there are no generally accepted indices which best represent model fit, a combination of several indices including CMIN/DF, RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index), IFI (Incremental Fit Index) and GFI (goodness-of-fit index) were employed in order to examine the construct validity of the questionnaire.

The RMSEA is an error of approximation index assessing how well a model fits a population (Brown, Citation2006). The lower the value of RMSEA, the better the model fits the data (Hair et al., Citation2010). The values between .05 and .08 are indicative of fair fit (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1993). The RMSEA value for the current model is .033, with the 90% confidence interval ranging from .026 to .039.

The other goodness-of-fit indices employed in this study were baseline comparisons indices including CFI, TLI, and IFI. The indices range from 0 to 1. The greater values indicate a better fit (Hair et al., Citation2010). A cut-off value close to .90 is commonly used for these incremental fit indices (Ho, Citation2006).

The value of CMIN/DF with 349 degrees of freedom was 1.413, which is well below the recommended level of 3 indicating an acceptable fit. GFI showed a moderate value of 0.915 marginally above the cut -off point of .90 which seems to be affected by the large number of observed variables in the model (Lacobucci, Citation2010). The baseline comparisons fit indices of CFI, TLI, and IFI lay beyond the threshold value of .90 suggested by Byrne (Citation2010). The values for the model as depicted in Table indicate a good fit of the AFL model to the sample data confirming the factor structure of the measurement model by the CFA.

Table 2. Reliability analysis

Table 3. Fit indices of the measurement model

Figure depicts the measurement model of latent variables of scaffolding and monitoring of assessment for learning practices in the standardized estimate. It also displays factor loadings which represent the correlations between each item and the latent variable.

4.3. Results of the quantitative phase

4.3.1. Research question 1

Three One-way ANOVAs were conducted for each independent variable to investigate if there were any significant differences in Iranian EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning practices in terms of academic degree, years of teaching experience, and language proficiency level taught,

As for the academic degree, a One-way ANOVA was performed. Tables and show the descriptive statistics results and the One-way ANOVA, respectively.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning of academic degree groups

Table 5. One-way ANOVA to compare bachelor, master and doctoral candidate participants’ perceptions of assessment for learning practices

According to Table , the bachelor, master and doctoral candidate Teachers’ perception mean scores were 4.34, 4.33 and 4.34, respectively.

Following Table , EFL the difference between the bachelor, master, and doctoral candidate participants in terms of their perceptions of assessment for learning practices was not significant (sig. = .88, p < .05). Additionally, the results showed that there was not any significant difference between these groups with respect to perceived monitoring (sig. = .37) and perceived scaffolding (sig. = .28).

In the next step, a One-way ANOVA was run to investigate whether there were significant differences in Iranian EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning practices with regard to years of teaching experience. The descriptive statistics results and the One-way ANOVA are depicted in Tables and .

Table 6. Descriptive statistics of EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning practices of experience groups

Table 7. One-way ANOVA to compare EFL teachers’ perceptions concerning experience groups

As displayed in Table , the perception mean scores of the groups in terms of teaching experience were: 1–5 years of experience (Mean = 4.37), 6–10 years of experience (Mean = 4.30), 11–15 years of experience (Mean = 4.34), 16–20 years of experience old (Mean = 4.32), and more than 20 years of experience (Mean = 4.35).

As Table portrays, the results of the One-way ANOVA suggested no statistically significant difference in EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning practices (sig. = .70), perceived monitoring (sig. = .70), and perceived scaffolding (sig. = .88) in terms of years of teaching experience.

A One-way ANOVA was also utilized to investigate if the language proficiency level taught influenced EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning practices. Tables and illustrate the descriptive statistics results and the One-way ANOVA, respectively.

Table 8. Descriptive statistics of EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning practices of proficiency groups

Table 9. One-way ANOVA to compare EFL teachers’ perceptions of assessment for learning practices in terms of proficiency level groups

According to Table , the perception mean scores of the elementary, intermediate, and advanced groups were 4.32, 4.33, and 4.35, respectively.

As determined by the One-way ANOVA, there was not any statistically significant difference between groups in terms of the perceptions of assessment for learning practices (sig. = .63), perceived monitoring (sig. = .62), and perceived scaffolding (sig. = .85).

4.3.2. Research question 2

Descriptive statistics were obtained in order to determine Iranian EFL teachers’ perceptions of the assessment for learning. Since the average score for each item as well as the whole questionnaire fell between 1 to 5, point 3 was considered as the mid-point. That is, the mean scores above 3 represent positive perceptions. Tables and 1 depict the descriptive statistics results of teachers’ responses to the questionnaire items.

Table 10. Descriptive statistics of EFL teachers’ perceived monitoring

Table 11. Descriptive statistics of EFL teachers’ perceived scaffolding

Analysis of the items subsumed under perceived monitoring revealed that EFL teachers assigned a high value to these practices.

The absolute majority of EFL teachers reported being strongly in favor of scaffolding practices. The descriptive statistics results revealed that they helped their students gain an understanding of the content taught by asking questions during class (Item 22). The results also depicted that EFL teachers were open to student contribution in the language class (Item 21).

Table depicts the three most frequent perceived AFL practices of EFL teachers. Based on the descriptive statistics, the highest mean score (Mean = 4.52, SD = .55) was ascribed to Item 22 indicating that 97.1 % of EFL teachers employ questioning as a scaffolding practice. Likewise, giving guidance (Item11) and student contribution in the class (Item 21) were perceived to be extensively implemented by EFL teachers.

Table 12. Descriptive statistics of the most frequent perceived AFL practices

It appeared that EFL teachers were quite unsure of some items including (3, 5, and 16). As shown in Table , the lowest mean scores were obtained for items 3, 5, and 16 which are subsumed under monitoring practices.

Table 13. Descriptive statistics of the least frequent perceived AFL practices

Additional descriptive statistics were run to get an overall picture of teachers’ perceptions of AFL, perceived monitoring, and perceived scaffolding. Table demonstrates the pertaining results.

Table 14. Descriptive Statistics of Teachers’ Perceptions about the Assessment for Learning

Based on Table , EFL teachers’ perception mean score was 4.34 suggesting that AFL was positively conceived by EFL teachers (Mean = 4.34). Furthermore, the participants also held welcoming attitudes toward monitoring (Mean = 4.32) and scaffolding (Mean = 4.36) practices.

4.3.3. Results of semi-structured interviews analysis

Following the thematic analysis of the interview data, four main themes were identified: 1) EFL teachers’ perceptions of AFL implementation, 2) benefits of AFL implementation, 3) EFL teachers’ AFL strategies, and 4) EFL teachers’ perceptions of factors promoting AFL.

By and large, the interview findings, substantiating those of the questionnaire yielded further insights into EFL teachers’ perceptions toward AFL. As for the first theme namely EFL teachers’ perceptions of AFL implementation, three different views were unfolded. In the first place, AFL to a great majority of EFL teachers (80%) was seen as effective and beneficial to learners. This was abundantly evident from the answers given to the interview questions. Holding strongly positive perceptions toward AFL, this group reported capitalizing upon AFL practices in the classroom. However, there were very few teachers (10%) who were not adequately cognizant both in theory and practice of AFL knowledge. These teachers held ambivalent attitudes toward AFL. The third group of EFL teachers (10%) held both positive and negative attitudes toward AFL. On the one hand, they accorded high priority on some EFL practices including questioning, group work, and decision making, but on the other, they did not seem to be supportive of some AFL practices focusing on learners’ weaknesses and self-reflection. The following three interview excerpts clarify their perceptions of AFL:

Well, I think, assessment for learning is an effective strategy for teaching. You know, I believe that it makes students have an in-depth understanding of the subject matter taught. (T13)

For me, I think assessment for learning is really practical and useful. It is my favorite practice in the classroom. I guess my language learners love it when I employ assessment for learning practices. I really enjoy practicing assessment for learning as it brings about substantial improvements in learning. (T 22)

I guess questioning, learner’s contribution, giving guidance, and providing positive feedbacks are beneficial to learners. However, to me, highlighting learners’ weak points, allowing them to decide on learning objectives, and making learners reflect on the learning processes involved are not equally important. (T11)

Closely associated with teachers’ perceptions of AFL and also in response to the question pertaining to the reasons for implementing AFL, the second main theme, that is, benefits of AFL implementation was extracted. Building on this, EFL teachers viewed AFL as an effective vehicle for teaching, satisfying a number of different purposes in addition to assessment and instruction. The most common purposes or merits of AFL in terms of monitoring and scaffolding were those of checking understanding (75%) and enhancing learning (85%), respectively. Further, some EFL teachers (67%) pointed to descriptive feedback given during AFL as a means to enhance learning. Half of the teachers favored AFL due to the role it plays in scaffolding students for the end of the term exam. Some EFL teachers (37%) viewed AFL as central to monitoring their students’ progress. Moreover, AFL was reported as being practiced by EFL teachers to modify instruction, make learners self-monitor their learning, and make learning authentic. Some of their accounts are as follows:

… it is also a good source of information based on which I can review my instruction and make necessary modifications…… assessment for learning informs me of my students’ progress. (T25)

Well, assessment for learning can capture students’ attention for learning… and makes them more focused on their learning tasks. (T37)

Once I use assessment for learning in my classes… well, my students feel more confident and less stressed. I guess they are more willing to communicate and interact with their peers. In fact, assessment for learning affords better opportunities for learner interaction. This is a real; I mean an authentic method of teaching. (T8)

I always try to offer my students timely feedbacks. My feedbacks are usually precise and descriptive. However, sometimes…. I give evaluative feedbacks as well. (T10)

Table depicts the benefits of AFL implementation and its associated sub-themes drawn from the interview data.

Table 15. Benefits of AFL implementation (N = 40)

In order to explore AFL practices employed by EFL teachers in the classroom, the researchers partly discussed the questionnaire items with the interviewees. Accordingly, they were asked to elaborate on the AFL practices and the reason(s) for their agreement or disagreement to the items. In addition, they named the most frequent AFL practices in their instruction. The most significant were practices subsuming under scaffolding including classroom questioning (95%), guidance (87%), and group work (87%), thereby, substantiating the quantitative findings related to the second research question. EFL teachers also displayed variations in AFL practices indicating their AFL awareness. Portfolio assessment (12%) and peer assessment (12%) were reported to be least used by EFL teachers. Table presents the practices along with the number of times they were mentioned.

Table 16. EFL teachers’ AFL practices (N = 40)

Some AFL practices as stated by EFL teachers are reported in the following interview extracts:

Umm…there are some assessments for learning practices which I adopt in my classes. I guess I use questioning; I also provide different scaffolds. Sometimes, I discuss the points to assess my students’ understanding. (T2)

I usually have a five-minute recap of what I taught before; mostly I review new vocabulary items or grammatical structures at the end of the class. (T1)

Well, I try to give my students the opportunity to think about the way they are learning English, I also help them decide on their learning objectives. By doing this, I try to resolve difficulties they may encounter while learning English. (T6)

The fourth theme drawn from the interview data concerned EFL teachers’ perceptions of factors promoting AFL. The data demonstrated that EFL teachers’ motivation, commitment, and innovation were instrumental in AFL implementation. They further stated that AFL culture in educational settings along with the class size (the number of learners in the class) assuredly impacted their use of AFL. To effectively support AFL, EFL teachers reported adopting various AFL practices to diversify instruction and to ideally optimize student learning. Table portrays the sub-themes representing the main theme of EFL teachers’ perceptions of factors promoting AFL.

Table 17. EFL teachers’ perceptions of factors promoting AFL

To some EFL teachers, the development of AFL practices calls for a cultural change in educational centers. Without the support of all stakeholders, it would be difficult to culturally encourage AFL. At the same time, the AFL ethos of assessment for the sake of learning should be put high on agenda. Along the same lines, few EFL teachers reported that they could not make use of AFL practices regularly. On this point, two English teachers reflected on the impact of school culture on AFL implementation as follows:

I feel my school does not hold a favorable view on assessment for learning and we are to stick to the school curriculum. Besides, we are pressed for time, and implementing AFL is difficult. (T7)

In high schools, conventional assessment is in the forefront and assessment for learning is of a low priority. You know, I guess, there is little room, for the implementation of assessment for learning. (T30)

Some EFL teachers stated in the interviews that their creativity and innovative assessment strategies in English teaching can develop assessment culture with learning as its core. Clearly, AFL serves to supplement instruction. For instance, a highly experienced English instructor mentioned that:

I have developed some assessment for learning practices through 25 years of teaching English. You need to be creative to devise practices to help your students move forward. Creative teachers always generate new ideas to make learning more effective. (T38)

Few EFL teachers held that the implementation of AFL requires a strong commitment to student learning. Having said that, they argued that some AFL practices are integral to their instruction. The following interview extract can better clarify the point.

I am strongly committed to employ assessment for learning in my classes. I adopt some AFL practices more than others……… although it is not an absolute duty, I enjoy practicing assessment for learning. (T21)

4.3.4. Results of classroom observations

To investigate the extent to which EFL teachers applied AFL practices in the classroom and to identify the most common AFL practices, the researchers utilized the classroom observation checklist. The results of non-participant observations as presented in Table1 showed that active questioning (Mean = 3.89), detailed guidance (Mean = 3.76), and student contribution (Mean = 3.58) were most widely adopted by EFL teachers. These practices were observed in action and ongoing. On the other end of the spectrum, there were few practices that were observed much less frequently including items 7, 9, 15, and 1 indicating that EFL teachers did not seem to be in support of peer-assessment (Item 9) and student self-reflection (Item 1). Likewise, they did not encourage learners to set learning targets (Item 7) and to self-monitor their learning (Item 15). On the whole, except for very few items in the checklist, namely the least frequent ones, EFL teachers showed to zero in on AFL practices during instruction. Table depicts the AFL practices which were in place in descending rank order.

Table 18. Descriptive statistics of EFL teachers’ classroom observation checklist

The observations of thirty-eight classes revealed important points concerning EFL teachers’ actual practice of AFL. The results indicated varying degrees of AFL use among EFL teachers. As expected, questioning was one of the main AFL practices employed by teachers. They posed different questioning techniques and encouraged language learners to ask questions from their peers and teachers. Teachers’ questions meant to raise student understanding. Based on language learners’ questions, teachers tried to provide assistance and feedback. Overall, teachers tended to create tasks and activities conducive to learning. Group discussion was also a common practice through which teachers employed a wide range of AFL practices with a view to promoting learners’ accountability and engagement. There were very few instances of peer-assessment in writing skill. There was also a downside to allowing learners to set learning targets. Overall, observations suggested that AFL practices featured in classroom settings where teachers honored a collaborative learner-centered approach to teaching.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore Iranian EFL teachers’ perceptions of monitoring and scaffolding practices of assessment for learning. The study also investigated AFL practices as a function of years of teaching experience, proficiency level taught, and academic degree.

5.1. Discussion of the first research question

The first research question explored the possible significant differences in Iranian EFL teachers’ perceived monitoring and perceived scaffolding of assessment for learning practices in terms of academic degree, years of teaching experience, and language proficiency level taught.

5.2. Years of teaching experience

Although perceived monitoring and perceived scaffolding practices of Iranian EFL teachers did not reach statistical significance as a function of teaching experience, the average mean of perceived scaffolding of experienced teachers, more specifically those having more than 20 years of experience (M = 4.39) was higher than that of novice teachers of 1–5 years of experience(M = 4.38). As for monitoring practices, the mean score of novice teachers was higher than those of the other groups which agrees with Oz (Citation2014) in which teachers of 1 to 6 years of experienced differed significantly with those of 11 to 15 years of experience. Along the same lines, based on Pishghadam and Shayesteh (Citation2012), there was no significant relationship between the different perceptions of assessment and teachers’ level of experience. Similarly, Estaji and Fassihi (Citation2016) found no statistically significant relationship between EFL teachers’ implementation of formative assessment strategies and the level of experience.

Novice teachers were more likely to monitor seatwork. They seemed to be reluctant to implement scaffolding practices. This is due to the fact that they may not have developed the teaching skill. Seasoned teachers, by contrast, were more accountable in establishing appropriate classroom practices and providing guidance.

Experienced EFL teachers were more likely to take scaffolding stances regarding AFL practices. One reason might be concerned with self-efficacy. According to Akbari and Moradkhani (Citation2010), experienced teachers enjoy higher levels of efficacy than do their novice counterparts.

5.3. Academic degree

The findings of the study revealed that EFL teachers did not significantly differ in their perceived monitoring and scaffolding practices as a function of academic degree. One possible line of explanation for this is that conventional assessment is dominant in the context of language teaching in Iran. Generally, assessment issues including assessment for learning, formative assessment, and assessment of learning are mostly addressed during MA/Ph.D. programs. Likewise, advanced assessment training offered at graduate levels may impact EFL teachers’ perceptions of AFL. BA holders might have had in-service courses on assessment. However, the mean score of the perceived scaffolding of Ph.D. group (M = 4.42) was higher than those of BA (M = 4.34) and MA holders (M = 4.36). This implies that EFL teachers with Ph.D. degree conceived of scaffolding practices of AFL as more important than teachers with MA or BA degrees. In contrast, EFL teachers with BA degrees obtained a higher mean score of perceived monitoring (M = 4.35) than those of MA (M = 4.31) and Ph.D. holders (M = 4.28). Based on the results, a regular pattern was observed between the mean scores of perceived monitoring and perceived scaffolding with regard to EFL academic degree. That is, the higher the academic degree, the more scaffolding and the less monitoring practices were adopted on the side of EFL teachers.

5.4. Language proficiency levels taught

Significant differences did not emerge on assessment for learning practices among EFL teachers in relation to proficiency level taught. One could reason that EFL teachers may teach English across different proficiency levels and their AFL practices are not strictly associated with a specific proficiency level taught. This could imply that EFL teachers implement AFL practices irrespective of the proficiency levels which they teach. Although the proficiency level was not a distinguishing factor in employing AFL factors, the mean scores of perceived monitoring and perceived scaffolding of EFL teachers conducting advanced levels were higher than those of elementary and intermediate. It seems AFL practices including self-assessment, questioning, and students’ involvement were more attended to in advanced levels. Such practices, however, seem to be best suited to advanced learners. This is due to the fact that EFL teachers are methodologically unable to utilize some of the AFL practices in elementary classes.

5.5. Discussion of the second research question

With regard to the second research question concerning AFL perceptions of EFL teachers, the findings demonstrated that AFL practices were held in high regard by EFL teachers. The quantitative data suggested that EFL teachers in this study effectively integrated assessment for learning into instruction.

In general, the findings showed that EFL teachers perceived the use of assessment for learning as beneficial and effective. This favorable attitude of EFL teachers toward AFL might be indicative of their high confidence in the implementation of AFL practices.

Based on the results of descriptive analyses, the mean scores of the indicators within the perceived monitoring construct showed remarkable consistency within the scale. The highest mean score (M = 4.52, SD = .55) was received for item 22 (I am open to student contribution in my language class.), indicating that the overwhelming majority EFL teachers (94.16%) were disposed to scaffold their students through instruction. That is, EFL teachers were strongly in favor of student contribution in the classroom. In contrast, the lowest mean scores pertained to items (3, 5, and 16). The items 3 and 5 obtained the lowest mean scores in a similar study by Oz (Citation2014). Indeed, these items are subsumed under monitoring practices which are basically concerned with learners’ involvement in language learning. It is inferred that EFL teachers were not favorably inclined towards learner involvement and decision- making in the process of language learning.

On the other hand, the results of descriptive analyses demonstrated that the mean scores for the indicators of perceived scaffolding were also highly consistent within the instrument. The majority of EFL teachers rated the instrument items more positively. Considering the most frequent scaffolding practices namely items 22 (I am open to student contribution in my language class), and item 21(By asking questions during class, I help my students gain an understanding of the content taught), we can infer that most of the EFL teachers used questioning in their instruction and supported student involvement in the class. In the same vein, Sardareh and Saad (Citation2012) found that teachers extensively utilize questioning as an essential learning and instructional technique. Likewise, Kayi-Aydar (Citation2013) views teachers’ questioning as a scaffolding strategy which promotes student contribution in the classroom.

The lowest mean score of scaffolding practices, on the other hand, was related to item 19 (During my class, students are given the opportunity to show what they have learned). Though EFL teachers proved to be in favor of their student contribution in class, they may be disinclined to offer them opportunities to show what they have learned.

Four main themes embracing most recurring sub-themes emerged from the responses given to the interview questions. The sub-themes related to the benefits of AFL implementation and EFL teachers’ perceptions of factors promoting AFL were in part reflected in other studies on assessment, particularly formative assessment. These themes as part of our findings were arrived at inductively with the literature review in mind.

The results of semi-structured interviews were in concert with the quantitative findings manifesting that EFL teachers put a high premium on quite the same AFL practices. Here again, EFL teachers showed to be more favorably disposed toward scaffolding practices including questioning techniques, guidance, and encouragement strategies. It is also noteworthy that EFL teachers did not report to extensively perform practices subsumed under monitoring. They showed to be less favorably inclined to check on their students while doing language tasks and to encourage self-reflection and self-assessment.

The findings of the classroom observations corroborated completely those of the interviews. The observations confirmed classrooms environments rich in AFL. Teachers’ actual practices as revealed through the observations substantiated in part the questionnaire results in which EFL teachers’ showed to favor AFL practices. Nevertheless, a slight mismatch was detected between their espoused perceptions of AFL and the beliefs in action. What was markedly absent in the classroom observations was the monitoring practices of AFL associated with self-reflection, metacognitive, and learner autonomy. The minor mismatches could be attributed to the fact that, teachers tend to overestimate their teaching abilities by providing biased responses to the questionnaire items. This discrepancy indeed accounted for adopting a mixed methods approach to study the issue.

6. Conclusion

In keeping with the new assessment trend to promote AFL culture among EFL teachers and to empower them to take advantage of the AFL practices, the present study probed into Iranian EFL teachers’ perceptions of scaffolding and monitoring practices of AFL. The study also investigated Iranian EFL teachers’ perceived scaffolding and perceived monitoring practices of AFL in terms of their demographic characteristics including academic degree, proficiency levels taught, and years of teaching experience. This study exhibited a clear picture of EFL teachers’ perceptions of AFL through a triangulated method.

The findings of the study demonstrated that the absolute majority of EFL teachers embarked on assessment for learning practices. Pat‐El et al. (Citation2015) put it that teachers’ beliefs about AFL contribute to the understanding of effective AFL implementation. Thus, this study might prove fruitful in a greater appreciation of scaffolding and monitoring practices of AFL by EFL teachers. The results also suggested that EFL teachers’ demographics namely, years of teaching experience, academic degree, and proficiency levels taught were not distinguishing factors in AFL implementation.

The findings gleaned from the questionnaire, were generally in concordance with those of the interviews and the classroom observations. However, the classroom observations illustrated a small discrepancy between Iranian EFL teachers’ positive responses to the AFL questionnaire and their actual practice of AFL in the classroom. More convergence was observed between EFL teachers’ perceptions of AFL from the three sources of data with regard to scaffolding compared to monitoring. In view of this, EFL teachers should strive to strike a better balance between these two elements of AFL in their instruction. Ideally, instruction and monitoring should be seamlessly integrated by teachers within classrooms.

An important finding emerging from the present study was that EFL teachers were less appreciative of monitoring practices, namely encouraging learners to set learning objectives, enhancing self-monitoring and self-reflection. On this point, in-service training courses on learning-oriented instruction could provide opportunities for EFL teachers to draw on a wider palette of AFL practice to enrich learning. In order for monitoring practices of AFL to play a more effective role in student learning, they should be performed throughout instruction rather than the end-point of instruction.

The findings of this study hold important implications for teacher educators and researchers to explore new avenues to integrate AFL into instruction. It also affords an opportunity for EFL teachers to broaden their knowledge through reflection on the findings of the study. Equipped with the knowledge of assessment for learning practices, EFL teachers are more likely to spur more implementation of AFL practices in the classroom. This awareness will result in the promotion of AFL culture in EFL contexts.

Informed by the limitations of the current study, future researchers are invited to replicate it using larger sample sizes for the qualitative data particularly classroom observations to accurately identify potential areas of mismatch. More importantly, longitudinal classroom observations are called for to shed more light on EFL teachers’ use of AFL.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohammadreza Nasr

Mohammadreza Nasr is a Ph.D. candidate in TEFL at Islamic Azad University, Shiraz branch. His research interests are language assessment, educational linguistics, and psycholinguistics.

Mohammad Sadegh Bagheri

Mohammad Sadegh Bagheri is an assistant professor of TEFL at Islamic Azad University, Shiraz branch. He maintains active research interests in second language research methods, e-learning and language assessment.

Firooz Sadighi

Firooz Sadighi is a professor of applied linguistics. He has published numerous books and articles. His teaching and research areas include first/second language acquisition, second language education, and syntax.

Ehsan Rassaei

Ehsan rassaei is an associate professor of TEFL at Islamic Azad University, Shiraz branch. His main research interests include second language teacher education and second language acquisition.

References

- Akbari, R., & Moradkhani, S. (2010). Iranian English teachers’ self-efficacy: Do academic degree and experience make a difference? Pazhuhesh-e Zabanha-ye Khareji, 56, 25–47.

- Assessment Reform Group. (2002). Assessment for learning: 10 principles. Retrieved June 20, 2017, from http://arg.educ.cam.ac.uk/CIE3.pdf

- Berry, R. (2008). Assessment for learning. Aberdeen: Hong Kong University Press.

- Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliams, D. (2003). Assessment for learning. Putting it into practice. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Black, P., & Jones, J. (2006). Formative assessment and the learning and teaching of MFL: Sharing the language learning roadmap with the learners. Language Learning Journal, 34, 4–9. doi:10.1080/09571730685200171

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education, 5(1), 7–73. doi:10.1080/0969595980050102

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Byrne, M. B. (2010). Structural equation modeling with Amos: Basic concepts, application, and programming. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Carless, D. (2015). Excellence in university assessment: Learning from award-winning practice. London: Routledge.

- Chappuis, S., Stiggins, R. J., Arter, J., & Chappuis, J. (2005). Assessment for learning: An action guide for school leaders. Portland, OR: Assessment Training Institute.

- Clark, I. (2012). Formative assessment: Assessment is for self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 24(2), 205–249. doi:10.1007/s10648-011-9191-6

- Colby, D. C. (2010). Using assessment for learning practices with pre-university level ESL students: A mixed methods study of teacher and student performance and beliefs ( Doctoral dissertation), McGill University, Montreal.

- Colby-Kelly, C., & Turner, C. E. (2007). AFL research in the L2 classroom and evidence of usefulness: Taking formative assessment to the next level. Canadian Modern Language Review, 64(1), 9–37. doi:10.3138/cmlr.64.1.009

- Cotton, K. (1988). Monitoring student learning in the classroom. Portland, OR: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory.

- Davison, C., & Leung, C. (2009). Current issues in English language teacher‐based assessment. Tesol Quarterly, 43(3), 393–415. doi:10.1002/tesq.2009.43.issue-3

- Dornyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Elizabeth, N. (2017). From a culture of testing to a culture of assessment: Implementing writing portfolios in micro context. In R. Al-Mahrooqi, C. Coombe, F. Al-Maamari, & V. Thakur (Eds.), Revisiting EFL assessment: Critical perspectives (pp. 221–235). Cham: Springer.

- Estaji, M., & Fassihi, S. (2016). On the relationship between the implementation of formative assessment strategies and Iranian EFL teachers’ self-efficacy: Do gender and experience make a difference? Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 8(18), 65–86.

- Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2011). The formative assessment action plan: Practical steps to more successful teaching and learning. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Gan, Z., Liu, F., & Yang, C. C. R. (2017). Assessment for learning in the Chinese context: Prospective EFL teachers’ perceptions and their relations to learning approach. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 8(6), 1126–1134. doi:10.17507/jltr.0806.13

- Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching second language learners in the mainstream classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Green, A. (2013). Exploring language assessment and testing: Language in action. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. B., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River: NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Hargreaves, E. (2005). Assessment for learning? Thinking outside of the (black) box. Cambridge Journal of Education, 35(2), 213–224. doi:10.1080/03057640500146880

- Hasan, W. M. M. W., & Zubairi, A. M. (2016). Assessment competency among primary English language teachers in Malaysia. Proceedings of MAC-ETL 2016, 66.

- Heritage, M. (2007). Formative assessment: What do teachers need to know and do? Phi Delta Kappan., 89(2), 140–145. doi:10.1177/003172170708900210

- Ho, R. (2006). Handbook of univariate and multivariate data analysis and interpretation with SPSS.Boca. Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

- Joshi, A., & Sasikumar, M. (2012). A scaffolding model-An assessment for learning of Indian language. Proceedings of the International Conference on Education and e-Learning Innovations (pp. 1–6). Sousse, Tunisia: IEEE.

- Kayi-Aydar, H. (2013). Scaffolding language learning in an academic ESL classroom. ELT Journal, 67(3), 324–335. doi:10.1093/elt/cct016

- Lacobucci, D. (2010). Structural equations modeling: Fit indices, sample size, and advanced topics. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20, 90–98. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2009.09.003

- Lee, I. (2007). Assessment for learning: Integrating assessment, teaching, and learning in the ESL/EFL writing classroom. Canadian Modern Language Review, 64(1), 199–213. doi:10.3138/cmlr.64.1.199

- Lee, I., & Mak, P. (2014). Assessment as learning in the language classroom. Assessment as learning. Hong Kong: Education Bureau.

- Oz, H. (2014). Turkish teachers’ practices of assessment for learning in English as a foreign language classroom. Journal of Language Teaching & Research, 5, 4. doi:10.4304/jltr.5.4.775-785

- Pat-El, R. J., Tillema, H., & Segers, M. (2013). Validation of assessment for learning questionnaires for teachers and students. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(1), 98–113. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02057.x

- Pat-El, R. J., Tillema, H., Segers, M., & Vedder, P. (2015). Multilevel predictors of differing perceptions of assessment for learning practices between teachers and students. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(2), 282–298. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2014.975675

- Pattalitan, J. A. (2016). The implications of learning theories to assessment and instructional scaffolding techniques. American Journal of Educational Research, 4(9), 695–700.

- Pishghadam, R., & Shayesteh, S. (2012). Conceptions of assessment among Iranian EFL teachers. Iranian EFL Journal, 8(3), 9–23.

- Poehner, M. E. (2008). Dynamic assessment: A Vygotskian approach to understanding and promoting L2 development. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Poehner, M. E., & Lantolf, J. P. (2005). Dynamic assessment in the language classroom. Language Teaching Research, 9(3), 233–265. doi:10.1191/1362168805lr166oa

- Rassaei, E. (2014). Scaffolded feedback, recasts, and L2 development: A sociocultural perspective. The Modern Language Journal, 98(1), 417–431. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2014.12060.x

- Rea-Dickins, P. (2004). Understanding teachers as agents of assessment. Language Testing, 21(3), 249–258. doi:10.1191/0265532204lt283ed

- Richards, K. (2009). Trends in qualitative research in language teaching since 2000. Language Teaching, 42(2), 147–180. doi:10.1017/S0261444808005612

- Salkind, N. J. (2007). Encyclopedia of measurement and statistics. London: Sage Publications.

- Sambell, K., McDowell, L., & Montgomery, C. (2012). Assessment for learning in higher education. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Sardareh, S. A., & Saad, M. R. M. (2012). A sociocultural perspective on assessment for learning: The case of a Malaysian primary school ESL context. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 66, 343–353. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.277

- Shepard, L. A. (2005). Linking formative assessment to scaffolding. Educational Leadership, 63(3), 66–70.

- Stiggins, R. J. (2002a). Assessment crisis: The absence of assessment for learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 83(10), 758–765. doi:10.1177/003172170208301010

- Stiggins, R. J. (2002b). Assessment for learning. Education Week, 21(26), 30–33.

- Stiggins, R. J. (2005). From formative assessment to assessment for learning: A path to success in standards-based schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 87, 324–328. doi:10.1177/003172170508700414

- Stiggins, R. J. (2006). Assessment for learning: A key to student motivation and learning. Phi Delta Kappa EDGE, 2(2), 1–19.

- Stiggins, R. J. (2008). Correcting errors of measurement that sabotage student learning. In C. A. Dwyer (Ed.), The future of assessment: Shaping teaching and learning (pp. 229–243). New York, NY: Erlbaum.

- Stiggins, R. J., Arter, J. A., Chappuis, J., & Chappuis, S. (2004). Classroom assessment for student learning: Doing it right–using it well. Portland, OR: Assessment Training Institute.

- Tsagari, D. (Ed.). (2016). Classroom-based assessment in L2 contexts. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wei, W. (2017). A critical review of washback studies: Hypothesis and evidence. In R. Al-Mahrooqi, C. Coombe, F. Al-Maamari, & V. Thakur (Eds.), Revisiting EFL Assessment: Critical Perspective (pp. 49–67). Cham: Springer.

- White, E. (2009). Putting assessment for learning into practice in a higher education EFL context. Sydney: Universal-Publishers.

- Wragg, E. C. (2004). Assessment and learning in the secondary school. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Appendix A

Semi-structured Interview Questions

1. What is your perception of assessment for learning?

2. What monitoring and scaffolding practices do you perceive you most/least widely adopt in your instruction?

3. Do you use assessment for learning in your classroom? If so, what kind?

4. Why do you employ assessment for learning in your classroom? What do you think are the benefits of AFL implementation?

5. Could you elaborate more on assessment for learning practices in the questionnaire?

Appendix B

Semi-structured Interview Original Quotes Reported in the Study

خوب، فکر می کنم سنجش برای یادگیری استراتژی موثری برای تدریس به شمار می رود.در واقع، بر این باورم که که سنجش برای یادگیری باعث می شود دانش آموزان درک عمیقی از موضوع تحت آموزش به دست آورند.(مدرس شماره 13)

از دید من، فکر می کنم سنجش برای یادگیری واقعا موثر و عملی است. این روش مورد علاقه من در کلاس درس است. به گمانم، وقتی از این روش استفاده می کنم، زبان آموزانم نیز لذت می برند. واقعا ازاجرای این روش لذت می برم چون پیشرفت های زیادی در یادگیری به همراه دارد. (مدرس شماره 22)

فکر می کنم، سوال پرسیدن، مشارکت دادن زبان آموز، راهنمایی و ارائه بازخوردهای مثبت به آنها مفید است. به هر حال، به نظر، برجسته کردن نقاط ضعف زبان آموزان ، اجازه تصمیم گیری دادن به زبان آموزان در مورد اهداف یادگیرشان و ملزم کردن آنها به اینکه در مورد فرایندهای یادگیری تفکر کنند، اهمیت یکسانی ندارد.(مدرس شماره 11)

… همچنین سنجش برای یادگیری منبع خوبی است که بر اساس آن می توانم آموزشم را بررسی و تغییرات لازم را انجام بدهم … سنجش برای یادگیری، معلم را از پیشرفت دانش آموزانشان مطلع می سازد.(مدرس شماره 25)

بسیار خوب،سنجش برای یادگیری توجه دانش آموزان را به خود جلب می کند و…باعث می شود دانش آموزان بر تکالیف خود بیشتر تمرکز نمایند.(مدرس شماره 37)

وقتی از سنجش برای یادگیری استفاده می کنم…خب، دانش آموزانم احساس اعتماد به نفس می کنند وکمتر دچار استرس می شوند.فکر می کنم، آنها تمایل بیشتری برای ارتباط و تعامل با همکلاسیهای خود دارند.در واقع ،سنجش برای یادگیری فرصت های بهتری برای تعامل ایجاد می کند.سنجش برای یادگیری روشی طبیعی و واقعی برای تدریس است.(مدرس شماره 8)

همیشه به دانش آموزانم بازخوردهای به موقع می دهم. بازخوردهای من دقیق وحالت توصیفی دارند.اما گاهی نیز بازخوردهای به دانش آموزانم می دهم که جنبه ارزیابی دارد.(مدرس شماره 10)

از روشهای سنجش برای یادگیری در کلاس استفاده می کنم. فکر می کنم، بیشتر سوال می پرسم و از روش های راهنمایی استفاده می نمایم .گاهی نیز،مطالب را مورد بحث قرار می دهم تا فهم زبان آموزانم را از موضوع ارزیابی کنم.(مدرس شماره 2)

معمولا، پنج دقیقه مطالبی را که قبلا تدریس کرده ام، مرور می کنم:بیشتر واژگان و ساختارهای دستوری را در آخر کلاس با زبان آموزان مرور می کنم.(مدرس شماره 1)

خب،سعی می کنم به دانش آموزانم فرصت بدهم تا در مورد روش یادگیری زبان انگلیسی خود،تفکر نمایند.همچنین به آنها کمک می کنم تا در مورد اهداف یادگیری خود تصمیم گیری نمایند.با این روش، سعی می کنم مشکلاتشان را در یادگیری زبان انگلیسی مرتفع نمایم.(مدرس شماره 6)

احساس می کنم در دبیرستان دیدگاه مثبتی در مورد سنجش برای یادگیری وجود ندارد. به هر حال معلم زبان باید طبق طرح درس عمل کند.همچنین، زمان کافی برای اجرای روش های سنجش برای یادگیری وجود ندارد.(مدرس شماره 7)

در دبیرستان روش های سنتی مرسوم است و سنجش برای یادگیری از اولویت کمی برخوردار است.بر این باورم که فضای مناسبی نیز برای اجرای سنجش برای یادگیری وجود ندارد.(مدرس شماره 30)

در طول 25 سال تدریس زبان انگلیسی، روش هایی برای سنجش برای یادگیری به وجود آورده ام.این روش ها حاصل خلاقیت بوده است که باعث پیشبرد زبان آموزانم می شود.معلمان خلاق معمولا ایده های جدیدی برای آموزش موثر دارند.(مدرس شماره 38)

خیلی زیاد به استفاده از روش های سنجش برای یادگیری پایبند هستم. البته از بعضی از این روش ها بیشتراز بقیه استفاده می کنم.اگر چه به کار گیری سنجش برای یادگیری،خیلی هم وظیفه اساسی نیست اما ازاجرای آن لذت می برم.(مدرس شماره 21)