Abstract

This paper reports an investigation of biology students’ discussion of knowing in work placements, as accounted in blogs. Twenty-two blogs, containing 78 individual entries, written in conjunction with a work placement course for students in a tertiary level biology program, have been analysed in the study (The blogs are publicly available here: https://biopraksis.w.uib.no). The aim of the paper is to increase understanding of how work placements shape biology students’ personal epistemological trajectories. The analysis is performed by employing a theoretical lens that emphasizes the situated nature of knowing, as enacted in working practices. The blog accounts consist of the students’ appraisal of their own learning and knowing in work placements, situated in biology undergraduate education. The investigation suggests that the students’ personal epistemologies develop in an interplay with context and personal epistemologies to shape their trajectories toward biology knowing. These trajectories have been analysed in terms of their procedural, conceptual, and dispositional dimensions. The use of blogs as a data source is argued to be appropriate to analyse personal epistemologies. Other strengths and weaknesses of this design are discussed.

Public Interest Statement

Work placements are, as of yet, a sparsely implemented measure in tertiary biology education, with a large variety of potential work experiences in which biology students can partake. This is a salient contrast to professional education programs, such as medicine or teaching where all students attend specific workplaces in their education.

This study aimed to examine how work placement experiences intersect with biology students’ personal epistemologies. We found several valuable procedures and concepts that students have engaged with, and which impacts their understanding of themselves and their values when engaging in work. We also propose a conceptual model that underlies the relationships between the contexts of work, knowing, and personal epistemologies. We urge researchers and educators to consider the model and our other findings when implementing work placements for biology students in tertiary education. As it outlines the diverse contributions to students’ learning in work placements.

1. Introduction

This study addresses the following research question: How do biology students describe their development of personal epistemologies in their work placement blogs? Based on an analysis of biology students’ blog accounts we propose a new conceptual model of biology students’ development of personal epistemologies as a sociocultural concept. Particularly, as to how personal epistemologies pertain to workplace circumstances.

Work placements (i.e., placing tertiary students in workplaces during their organized education) are increasingly implemented as a legitimate educational provision in higher education (Costley, Citation2011; Kennedy, Citation2015). This increase is a likely effect of a higher number of students in higher education, thereby underpinning the need to secure employment for students after graduation, which has increased the need for measures to secure employment for students after graduation (Mok & Neubauer, Citation2016). Aside from the emphasis on employability, cultural (i.e., situated, relevant here as students engage with contexts in work) contributions for learning as they relate to students’ situatedness into work placements should be examined (Loftus & Higgs, Citation2010).

The affordance of work placement training in biology education has so far received little attention. The few studies that have been carried out, have pointed to some possible benefits, such as increased skills training and preference among students for increased workplace integration (e.g., Parker & Morris, Citation2016; Scholz, Steiner, & Hansmann, Citation2004). To examine cultural contributions to learning, the emphasis is put on students’ enactment of science as they participate in practices. This enactment can be captured through students’ epistemological accounts. The role of epistemological development in work placements has a particular interest because students’ epistemologies can be a crucial component of science education (Berland & Crucet, Citation2016; Collins, Brown, & Newman, Citation1989; Roth & Roychoudhury, Citation1994). It is generally believed that the advancement of epistemologies will precipitate students’ independent scientific knowing (i.e., seek out and appropriately handle new knowledge without teacher supervision, see Deng, Chen, Tsai, & Chai, Citation2011). Epistemology refers to theoretical frameworks about the nature of knowledge, and individually held beliefs that derive from individual life histories. Individuals’ thesis of epistemology are referred to as personal epistemologies, Hofer describes it as the following:

[Personal epistemology addresses students’ thinking and beliefs about knowledge and knowing, and typically includes some or all of the following elements: beliefs about the definition of knowledge, how knowledge is constructed, how knowledge is evaluated, where knowledge resides, and how knowing occurs. (Citation2001, p. 355)

This description is helpful to conceptualize the core of personal epistemologies, though it pertains especially to individual students’ perspectives, and does not account for circumstances in which the students are situated as they develop their personal epistemologies. In the present study, we examine biology students’ development of epistemologies in relation to their work placements. Thus, there is a need to expand available knowledge concerning students’ enacted epistemologies in workplaces, particularly the manner in which workplace circumstances contributes to scientific (biological) knowing. Here, scientific knowing refers to the practices by which biologists develop available understandings about the world, this includes concepts and procedures that are continuously enacted and remade in practices by biologists (Kelly & Licona, Citation2018; Knorr Cetina, Citation1999; Kuhn, Citation2012). It is not limited to research Institutes, and applies to all enactment of knowing of the natural world in communities, workplaces, and otherwise in individuals’ lives (Roth & Lee, Citation2004).

Workplaces are, among other things, characterized by the enacted practices of its members (Nicolini, Citation2012). Practices emerge through patterns of human behaviour, constituted of individuals enacting symbols, for instance through “instrumental, linguistic, theoretical, organizational, and many other frameworks” (Knorr Cetina, Citation1999, p. 10). Knowing is enacted through a practice of understanding (Chaiklin & Lave, Citation1996), that transcends traditional school-oriented learning metaphors, towards a situated conception of learning. Situated learning refers to knowing that emerges as individuals find themselves in new circumstance (Lave, Citation1997), when they come into contact with materials and practices which individuals might participate in. Roth (Citation2003) has developed sociocultural theorizing in the sciences in particular by advancing that science should not be restricted to researchers’ labs, but an integrated facet of local communities. Based on this theorizing, situating students into workplaces, where they can participate in practices and enact science themselves, should be encouraged.

Based on a situated conception of science learning, personal epistemologies in work can be construed as they have been advanced by Billett (Citation2009); to be inexorably linked to enacted, situated practices, that must be analysed through context (i.e., as a sociocultural practice). According to Billett, “personal epistemologies are seen as including how individuals’ ways of knowing and acting arise from their capacities, earlier experiences, and negotiations with the social and brute world across their life histories” (Citation2009, p. 231). Billett provides an account of how individuals engage with knowing derived from their workplace experiences, with what seems to be a clear emphasis on individuals’ situatedness to conceptualize this process. Thus, Hofer’s (Citation2001) conceptualization of personal epistemologies will here be amended to include an account for the situated practice in which individuals enact knowing. This precipitates an account for individuals’ subjectivity (i.e., their backgrounds, their dispositions, and their beliefs about their own stance in the practices for which their personal epistemology develops) as they participate in work.

Finally, by examining students’ blog accounts, we aim to expand on the available literature on ways in which to investigate digital experience (Pink et al., Citation2015). When properly structured, for instance by providing clear guidelines, blogs are found to be a useful avenue through which students can reflect on practices and their own learning (Jones & Ryan, Citation2014; Stoszkowski & Collins, Citation2017). As such, they suit our purposes to examine students’ epistemologies in relation to their work placement experiences. Our aim is not to promote blogs as a particularly beneficial way in which to examine students’ accounts, but one among others that can be useful given appropriate structure and student contribution. As Hew and Cheung (Citation2013) have found in their review, blogs as an educational measure seems to be more dependent on its particular pedagogical method rather than the digital nature of blogs specifically. Thus, we wish to contribute to available understandings of blogs and assessment through blogs.

2. Methods

2.1. Context and data source

A sociocultural analysis of personal epistemologies in work placements, requires the opportunity to follow actors in their daily routines. This requires access to events as they occur and repeat themselves in context (Eraut, Citation2004), and preferably narrated from the perspective of the participants. The biology students in work placements were geographically scattered, which made a participatory approach to data collection demanding. The solution in the present study was to build on students’ individual accounts from their everyday work practices, as they are presented in blog entries. The blogs were written as part of the students’ course assignment and were by teachers expected to promote student reflection. At the same time, the blog entries constitute the main material for assessment, that is, as part of the course evaluation. In research terms, the blog entries reflect the interaction between the students and their contexts as it proceeds in a situated practice. They are written alongside the work placement and specify students’ unfolding experiences and their developing views on their own participation and knowing.

Data collection based on internet resources has been advanced by several researchers who argue that practices can be discerned through digital media, documents, and other digital expressions of behaviour (e.g., Hine, Citation2000; Kozinets, Citation2015; Postill, Citation2016). That is, digital data is as legitimate as non-digital expressions, though gathered in a different format than traditional inquiry. In the present investigation, the work placement experiences occur regularly, over time, and in several locations (i.e., workplaces) simultaneously. Hence, the students’ blogs allow for data collection of the specific and simultaneous instances that are relevant for the study. The blogs thus constitute a site for exploring the development of personal epistemologies, it is not a study of how these epistemologies are impacted by the digital (Markham, Citation2018).

2.1.1. Students

The 22 participating students (19 women and three men) were all enrolled in tertiary level biology education. The eschewed gender balance represents the over-representation of women in this particular course, a fact that also holds for biology in general. Gender was not analysed in the study. The majority of students had finished two semesters of tertiary level biology studies at the time they participated in the study. At this time, the students have also completed courses in philosophy, mathematics and chemistry. The participating students were aged 20–30 and were either enrolled in a Bachelor of Science or a Master of Science programme. All participating students were Norwegian nationals, except one student from North America. The blog entries are public accounts accessible through the internet. Students’ active consent to participate in the study was secured through e-mail- and telephone correspondence, 22 of a total of 23 students agreed to participate. The procedure to obtain students’ consent was determined in consultation with the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD, http://www.nsd.uib.no/nsd/english).

2.1.2. Workplace course

The students attended a selective university course implemented every semester across 2015 and 2016 to provision work placements for biology students in a Norwegian University (the course development is detailed here, Velle, Hole, Førland, Simonelli, & Vandvik, Citation2017). The students were assigned a work placement by the course teachers based on a three-line application form. The course was assessed as pass/fail based on completion of both the workplace attendance and a report, which comprised the blogs, an oral presentation of the work placement, and a short reflection note. Workplace attendance was assessed by the work placement host, while the report was assessed by the course teachers.

2.1.3. Blogs

Blogs are public, often periodical, composite representations that can integrate expressions, such as written texts, pictures, and videos. Blogs, like journals, are often written concurrently, and seldom refer to a far-removed instance. Frequent use of photographs, hyperlinks and other expressions further emphasize the situated nature of blogs.

One strength of blogs as data sources is transparency, since readers can question and interrogate into claims made about the students’ expositions (Snee, Citation2008). The students also narrate their experiences conscious that the entries are public. The data are self-reported which means that the students’ perspective on experiences and participation are prioritised. However, the public nature of the blogs, which are easily discernible by work placement hosts and peers, can be expected to reflect an account which can be collectively accepted. The students’ reports of their thinking and their activities are also substantiated by photographs, and short end-of-term presentations (which the researchers were able to attend), of which no discrepancy between these expressions and blog content were revealed.

The data consists of 85 blog entries. The students were asked to write an average of 400 words divided among four entries. Students could also choose to write three entries, provided that they responded to all tasks, and had a similar overall word count. Nineteen students wrote four entries each three students wrote three entries each. This adds up to 189 pages of written material including pictures. The blogs were published on a site administrated by teachers; students could publish entries themselves once they were given author privileges at the commencement of the course. The blogs were hosted on a single site to ensure that readers could easily find accounts of various workplaces, to ensure the quality of the webpage, and to ensure that inappropriate content such as personal characteristics could be edited if needed. To date, editing by teachers has not been needed or carried out in the course. Students were asked to include a picture or illustration in every entry. The students were prompted to write the entries as popular science, meaning that it should be readable by non-biologists. References were allowed but not encouraged. To give the students a better understanding of the expectations for the blogs, it was emphasized that they should write about their learning, and not overly detailed accounts of the technical procedures of their work. To provide structure for the blogs, the following expectations for each of the blog entries were given (these could be responded to interchangeably, though this was a suggested succession):

Before the work placement: In the first blog entry, the students were tasked with presenting themselves, and their expectations of the work placements.

During the work placement: In the second and third blog entries, the students were asked to narrate experiences, with an emphasis on what they had learned. The students were also asked to discuss whether they became curious about exploring new knowledge as a result of their experiences.

After the work placement: In the fourth entry, the students were asked to sum up their workplace experiences, whether it had impacted their thoughts about being a biologist, and whether it had fulfilled expectations.

Pass/fail was based on whether the students had responded to the above. The students were able to edit their blog entries freely until the point where they were assessed by teachers at the end of the course.

2.1.4. Workplaces

The students could apply to several work placements (see Table ). These consisted of both public agencies, private research enterprises, and non-governmental organizations. All work placement hosts were selected based on whether they made use of biological competence, and had available work tasks for students. The hosts had to appoint a supervisor, with whom the student had everyday contact. A supervisor was necessary to ensure that course teachers and students had a contact person, and to ensure work hosts’ responsibility to supervise the students. The students needed to attend 140 h of work to pass the course. Time used to write blogs, and other related work came in addition to this.

Table 1. Overview of student distribution in workplaces

The students participated in a large variety of practices, both inside a particular workplace and between different companies. For example, one student worked on research on marine resources, another worked as an assistant upper secondary school biology teacher, one in a small research station in a rural area, and another in a municipal environmental agency. Although most students attended research institution workplaces, the work tasks within these varied. First, the research institutions focused on different disciplinary domains; one conducted most of its research in the marine domain, another on terrestrial research, and another focused on both terrestrial, marine, and aquatic research. Also, within each domain some students worked more on research (i.e., the actual gathering and analysis of data with an aim to publish in peer-reviewed journals or other commissioned reports) while others worked more on dissemination and public outreach within a research institution (i.e., collaboration with local schools, municipality, and other activities founded in biological science without an explicit aim to publish peer-reviewed research). Thus, students engaged with work in office-, field-, and lab-settings throughout their work placement periods.

3. Analysis

To make sense of students’ personal epistemologies in their work placements, the blog entries have been analysed as texts including images. The images provide additional empirical information. Both text and images were analysed within a hermeneutic interpretative approach and with a reflexive and continuous relationship to theoretical concepts and ideas (Jackson & Mazzei, Citation2018). The analysis process commenced during the design of the study and continued throughout. The blog entries were all compiled into a single document for each student. The blog entries were imported in their entirety including images. The analysis consisted of two phases, one initial compilation and a second where the material was construed through the sociocultural lens. Analysis in both phases was supported by the use of Nvivo (NVivo for Windows, version 11.4.1).

The first phase consisted of representing several successive points of time regarding individual students’ experiences, blogs allow for inquiring into aspects of students’ epistemological development. Due to the large number of documents, we initially read the texts to get an impression of the whole content. To map practices as students engage with them, the students’ expositions were in the first phase of the analysis construed by identifying i) how they first introduced themselves and their interests, and ii) how those dispositions manifested, or were otherwise negotiated in response to their participation in workplace practices. Thus, we gained an overall estimation of the students’ breadth of experiences and compiled an overview of students’ workplaces. The first phase also revealed students’ inherent dispositions as they engaged with their respective workplaces.

In the second phase, Billett’s (Citation2009) perspectives were employed as a lens to both analyse personal epistemologies as they emerged in students’ accounts of their work will, and to identify the nature of the scientific endeavours the students enacted. An ordering of knowing had to be established to make the data useful to address the research question. Billett (Citation2009) advances that implementing differentiated dimensions of knowing can help account for personal and social contributions to personal epistemologies. The students’ accounts were analysed in terms of knowing that was enacted, propositional, and related to personal and situated antecedents to their work placement.

Given the sociocultural nature of personal epistemologies in workplace practices, the analysis needed to provide an account for the contributions of situated activity as well as conceptual contributions that are inherent to scientific culture, that is, propositional knowing. The notion of knowing how and knowing what was introduced by Ryle (Citation2009), and is a well-suited ordering of knowing as it lends legitimacy both to propositional knowing and situated activity, and their intertwined nature (Brown & Duguid, Citation2001). The notion states that individuals can know concepts regarding a phenomenon, and procedures by which the phenomenon is enacted. Both concepts and procedures are more or less interdependent, yet clearly distinctive (Ryle, Citation2009). To account for individuals and their relationship to the circumstance, individuals’ dispositions are also included. The inclusion of dispositions is in line with more recent theorizing regarding individuals’ knowing and their engagement with practices, whereby the ability to apply knowing in work has little worth without individuals’ propensity to actually engage with any given activity (Billett, Citation2001; Hodkinson & Hodkinson, Citation2004; Kennedy, Citation2015). Thus, biology students can, as an example, know traits of any specific plant species (e.g., typical length, appearance, and geographical distribution), the procedure by which information about this species is accumulated (e.g., research, taxonomy, other biology practices), and the value and cultural role of working with, and employing knowledge about the species (e.g., environmental concerns, use in agriculture). Students’ accounts of their knowing related to these activities will be the focus of the present investigation.

Thus, we selected instances of procedural and conceptual knowing, and instances where students narrated dispositional content, and compiled these into a table to create an overview of how the students’ experiences could be construed to represent knowledges of different epistemological character. Images were treated as “parts of the culture” and analysed with reference to its relation to the text. For instance, the students often provided illustrations that displayed the procedural creation of a product. The illustration could, for instance, display the situated nature of the work, that is, the local community or workplace in which the work took place. The blogs could otherwise give other textual representations of thoughts and beliefs about the biological knowing that was enacted in the work that the students participated in.

Findings were analysed continuously by engaging peers and theoretical perspectives during the investigation (Pink & Morgan, Citation2013). In the present study, this was done by discussing the findings in groups and applying the theoretical lens as described above to continuously discern students’ epistemological accounts. The initial findings were presented in symposia with other researchers and authors, to ensure that the framing into procedural, conceptual and dispositional units made sense to the given data, and to make sure that the results align with the students’ utterances. As suggested by Creswell and Poth (Citation2018), the themes were established by discerning patterns in the students’ expositions, this includes reading and challenging findings continuously (i.e., as we performed in symposia and through repeated interactions with the material).

4. Findings

The students’ accounts revealed three distinct personal epistemological developments. In the present findings, not all students described all three themes in their experiences, though at least one of the three was present in all students’ expositions. No students described an opposite experience from the three themes that emerged.

The themes adhere to well-described concepts; (i) tenacity, working in the face of adversity (Kwon, Citation2017); (ii) subjective, or personal willingness to change to accommodate to the new practices in which the students participate (Rogoff, Citation1995); (iii) finding cohesion between campus- and workplace-based practices (Gherardi, Citation2009). The students’ appraisal of these practices should not be conflated with Piaget’s (Citation1964) notion of equilibrium. In Piaget’s conceptualization, new experiences have to be accommodated in relation to previous experiences. Rather, Gherardi (Citation2009) holds that “a field of practices arises in the interwoven texture that connects practices to each other, and that this texture is held together by a certain number of practices which provide anchorage for others” (p. 524). So that practices in campus and at various workplaces interact as students enact biology in work.

The diversity in experiences is an important first characteristic of work placements for the students, and perhaps reflects the diversity of workplaces that employ biology. Personal epistemological developments for students will at times be specific to certain circumstances, while others transcend several circumstances. For instance, one students’ work placement in a municipal environmental agency consisted of both species taxonomy, report writing, and local community outreach to ensure the safe passage of deer across roads with heavy traffic. To provide a comprehensive overview and to reflect the digital ethnographic techniques utilized, both short vignette descriptions, illustrations, as well as excerpts from the students’ blogs are provided below. All excerpts are translated from Norwegian.

5. Working in the face of adversity

Several students worked on projects that followed the ebb and flow that accompany project work. In encountering challenges, the students had to mobilize values, such as willingness to engage in and overcome difficulties. Kwon (Citation2017) suggests that this disposition is an expression of agency in working experiences. An account from a student’s work on a project on marine resources is presented below. It is our summary from two different blog entries.

Blog 1 vignette.

The blog entry starts with a short biographical note. There is a picture of a creature seemingly growing on the seafloor. By reading the rest of the blog post it is clear that it is a tunicate, a marine invertebrate. The student goes on to account for how she has been assigned to a private research institute that has an ongoing research project on tunicates. The student then goes on at some length about tunicate properties, their anatomy, behaviour and other traits. She also includes a second tunicate picture that visualises tunicate anatomy. The experiment she will partake in aims to explore how tunicates can help clean wastes from fish farms.

Blog 3 vignette.

The third blog entry first displays what seems to be a laboratory setting. Two gloved hands are holding on to pincers above a tunicate lying on a white, sterile surface. The student writes that it is “lovely when we are starting to learn things”, and “we are just able to do what we are asked to do without [supervisor] having to show us how we do it.” The student then goes on to discuss the state of the experiments. We learn that one experiment is to take place indoors while others are performed outdoors. The student also gives some additional information about tunicate behaviour, she describes how the experiment has to accommodate for the life phases of tunicates. There is an additional photograph of a person looking through a microscope, and a picture of a person working on a tank. Presumably, the tank contains tunicates and have been treated with different materials to determine the tunicates’ ability to filter waste from fish farms.

These vignettes display one initial pre-work placement blog entry and one entry further into the work placement period. The student was focused on providing straightforward conceptual knowledge about tunicates, while the pictures showed both tunicates and others focused on how the students engaged in laboratory procedures. In other words, they focused more on work rather than the subject of the work. As the project advanced, the students encountered difficulties:

Unfortunately, experiments do not always follow the course we wish, [but] then there is nothing else to do but to start again. We were unlucky and many tunicates died after a cold weekend. It was too cold and they froze in their tanks. We had to remove all the dead animals, clean and wash all the equipment and wait for new animals to be old enough to restart the experiment. […] I have discovered that patience is an important factor while performing experiments, and often you have to do things again and again to get precise results.

The above excerpt displays a crucial advancement of personal epistemologies. The enactment of an experiment requires a correct execution of consecutive actions, founded on understanding of scientific knowledge. And even if an experiment is carefully planned, the student realised that unforeseen critical events may occur. The student emphasizes the rigorousness and tenacity required to complete a successful experiment. When her test subjects died, the student had to repeat the experiment at the cost of several days of work. Thus, the student has come to engaged with the values (research ethics, will to complete work) and approaches required in the context (i.e., workplace) in which she found herself.

6. Participatory appropriation

Rogoff (Citation1995) has shown how a considerable dimension of individuals’ participation in sociocultural activity derives from an accommodation of the practices for which the individual participates. She refers to this as participatory appropriation, and holds that individuals’ development intersects with practices of communities. Rogoff emphasizes that participatory appropriation “contributes both to the direction of the evolving event and to the individual’s preparation for involvement in other similar events” (Citation1995, p. 153). Thus, the students came to engage with workplace practices, they emerged as biologists: in the blogs the students showed how these practices precipitated future work, learning and biology knowing. These advancements pertains to development of personal epistemology, or as Billett holds “[students’] intentionalities when engaging in activities and interactions and the subsequent responses to them” (Billett, Citation2014). Below is an example of a student’s propensity, as she came to engage with the workplace practice that coincided with her interests:

The last time the trawl entered the ocean, it raked the ocean floor. This was not supposed to happen, but for me, it didn’t hurt that much, because up with the trawl came a cacophony of life, which one will never encounter among the pebbles of [the local lake]. You’d better believe that I was on deck and having a great time with just observing the many amazing lifeforms. It was as if seven-year-old me was back, eager to live and to learn.

The above excerpt displays a dramatic account of the work of a species inventory. It seems clear that the student found the experience to be exhilarating, especially in how it afforded her with engagement with real life biology. These sentiments tie into her previous blog entries, where she professes a deep interest into marine life, something that steered her higher education choices. Here she states:

After spending several hours and days along the coast with my nose pointing down, the choice for higher education was easy. It had to be (marine) biology. Being able to work with what you like is probably every workers’ dream, but what sort of jobs can a biologist really have and what do you do? Hopefully, [the work placement] will help me get better insight.

One student found that the interaction with local communities, co-workers, and other persons associated with the work was an important workplace experience. For instance, one student who worked with the municipality conservation office found that some hunters were hostile to assessment and control, while others found it to be an opportune moment to relay old war- and hunting stories. Another aspect of the personal investment required by the students, was a perceived alignment between values and conceptions about useful work, environmental impacts, and advancing a financially viable enterprise: “I felt like I worked with and for the local community for causes I truly believe in and support. I´m talking about renewable and environmentally friendly resources and practices that aim for sustainability”.

7. Finding cohesion between workplace and campus practices

Kennedy (Citation2015) suggested that there is an inherent tension between knowing as conceptualized in what she calls Academy settings and Practice settings. This tension has been examined by theorists such as Dewey (Citation2011) in the early 1900s and can be traced as far back as Aristotle. This tension is a potential crisis of epistemology that individuals can encounter during their work placements. On one hand, knowing is authoritative, validated, and propositional, while on the other hand, it is experiential, situated, and derives from participation in practices. These perspectives blend with the analytic assumptions of knowing employed here, which comprises both procedural, conceptual, and dispositional dimensions (Billett, Citation2009). These dimensions apply to all settings the students have engaged in. For instance, procedural knowing is often associated with working, and conceptual knowing in turn associated with academic settings (Duguid, Citation2005). Rather, procedures and concepts emerged throughout the students’ working experiences. Given the students’ individual life histories, dispositions emerged as a matter of course during their experiences. The cohesion between settings, however, remains a pressing issue, not least for science education where there is tradition to remain esoteric (Knorr Cetina, Citation1999).

Considering their everyday activity as biology students, it is perhaps not surprising that the students frequently give accounts of their learning by contrasting experiences in the workplace with experiences at the campus. In the blog posts written before the work placements, students iterated how they wanted to “actually do biology”. One student stated that “it’s incredibly cool that I am allowed to use the knowledge I have acquired in the last two years, and finally exhibit it. Everything you learn in lectures become so much more real and exciting when you are able to see it in front of you”. Another student iterated how the work placement could spur further studies: “the more knowledge I gained through the biology study, not least [the work placement course], the more I wish to know and acquire even more knowledge. Perhaps I want to be a scientist?” Once the students started their work placement, some found that the more conceptual knowing they had engaged with at campus aided them in more procedural tasks. For instance, one student iterated:

The learning curve has therefore been a steep one, as I have to familiarize myself with all aspects of a very broad field, including—but not limited to—the factors that affect the health and condition of soil and the different nutrients that plants need. As such, I find it useful and beneficial to have background knowledge in ecology.

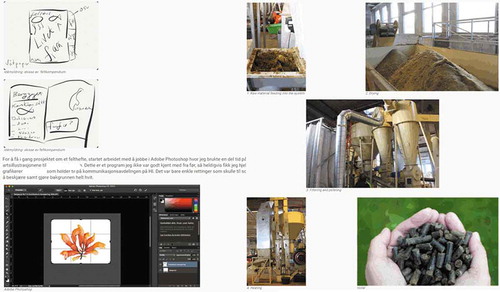

The students’ pictures also effectively displayed the procedural knowing prevalent in their work activities. One student displays this by showing the working process for creating pamphlets concerning marine life, and another displayed the processing work for creating fertilizers from horse waste.

One student found that the initial planned work tasks had to be amended and transformed during the work placement, and iterates:

I was tasked with reading up on how to estimate the stock of deer in [the local city], by using faeces-taxonomy. I quickly discovered there was little available literature on the subject, and even less related to deer, that we were supposed to read about. We then decided to freeze that project in favour of smaller projects and working on smaller, but more, tasks instead. Now, the focus is to update the mapping of deer trails in [the local city]. The method that we will use is to use maps in the wildlife registry and investigates where there are most [car] accidents with deer.

As shown in the above excerpt, finding that their learning transformed over the course of the work placements, ties into other students’ experience with adversity and problem-solving over the course of their work placements. According to students’ accounts, they had to mobilize new procedures and new concepts in conjunction with their tenacity to complete their work. As the excerpt above suggests, when the student refers to “we decided”, these shifts occurred in consultation with supervisors.

In Figure , the students explained the procedures they employed at work through illustrations. In both cases, they show successive steps to arrive at the finished product. In their written accounts, the students explain how these procedures are enacted in various ways to create a useful product, as a particular salient aspect of their engagement in work.

Figure 1. Students display their working procedures using pictures. To the left is shown the working procedures of a student who constructed a pamphlet. To the right, another student depicts the successive steps to create manure

The students’ accounts of activity show a close proximity between design, procedures, and analysis. This was, for example, shown by two students who narrate their experiences with completing a tunicate experiment. This experiment is performed (procedurally) on the basis of conceptual knowing about the need for fish feed in commercial aquaculture. Likewise, this procedure at first fails and is amended by engaging conceptual knowing about tunicate development. By carrying out these amendments the students engaged with biology knowing, both procedurally and conceptually.

In this work placement, it is also clear that most of these dimensions of knowing are engaged by the students in regular courses at the campus. Indeed, statistics, laboratory work and taxonomy are considered to be core competencies in a comprehensive biology education (Singer, Nielsen, & Schweingruber, Citation2013). Thus, procedural and conceptual knowing is afforded to the students prior to their work placements, the students’ accounts emphasize a development (i.e., enactment of statistics, laboratory work, and taxonomy) in relation to their work placement.

8. Discussion

It has been suggested that novel contexts and engagement with new circumstances are of particular value in the development of scientific knowing (Rennie, Citation2014). These authors particularly refer to the enacted nature of many scientific activities, such as sampling, laboratory work, and otherwise gathering data about the natural world. This enactment represents practices in which students should engage to develop their scientific knowing. Roth (Citation2003) also suggests that students’ engagement with communities is helpful to advance their understanding of themselves and of the viability of scientific knowing. This could, for instance, be to support communities in how to handle local challenges such as pollution, clean water, and power supply. In this perspective, the development of scientific epistemology is not simply a personal trajectory. It derives from societal underpinnings, and the community in which the student finds him- or herself.

Given the primacy of context in our examination of individuals’ personal epistemologies, it is worth noting that the blog entries are concerned with individuals’ trajectories into a new circumstance. The entries are cast in a context of previous education experiences, potential employment opportunities in their work placements, and enactment of biology in work. The blog entries display the students’ thoughts about biology as a scientific discipline, its role in societal developments, and its efficacy to solve difficulties at hand. That is, general statements about epistemology. In the following, it will be argued that these sentiments regarding science are closely interlinked when understanding students’ personal epistemology.

The analysis shows how dispositions and personal epistemologies intertwine during the students’ work placements, this manifested both in response to challenges and through participatory appropriation. For instance, environmentally conscious students perceived that the use of different methods has to be economically viable on one hand. On the other hand, the results can provide an alternative to current practices which are not environmentally friendly. Both considerations have to be fulfilled for the workplace to be at all viable for the student, both as a present and future workplace. The alignment with epistemology is relevant because certain expressions of knowing are relevant in order to investigate phenomena, and this knowing is enacted (i.e., practiced) at campus prior- and subsequent to the work placement, and employed at the workplace.

Thus, some instances of work placements advanced students’ thinking toward research-oriented conceptions of knowing. For example adapting approaches (i.e., research design) based on results, procuring and using appropriate tools and literature, and seeking out new knowledge (i.e., from peers, supervisors, and others with applicable skills) where required to advance the quality of their work.

9. To work and to enact biology: a conceptual model

The analysis has shown how students emphasise their personal values in their accounts; how these values developed prior- and subsequent to their work placement. This emerged through the students’ focus on how previous experiences align with current choices (i.e., choice of work placement) and then deliberations about future career trajectories.

As epistemologies are here discerned by three major expressions (procedural and conceptual knowing, and dispositions), it is evident that the students have engaged in activities which have developed diverse expressions of knowing through work (i.e., the students have engaged with practices where this knowing was enacted). The students’ dispositions were accounted through life histories. For example, for one student, interest in marine life and diving, has led one student on her current path in marine biology, whereas occurrences in work placements have impacted their subsequent desires for approaches to knowing. For example, species identification is a practice with nested conceptual and procedural knowing that has an increased relevance to future work. Participating in practices that integrated relevant (i.e., for individual students) capabilities, values and potential for steady employment permeated many of the students’ accounts.

Given that individuals’ personal epistemologies precipitates the way in which scientific knowing is employed, and brought to bear in response to challenges (Kelly & Licona, Citation2018; Schommer, Citation1990). It is worth noticing that the students detail development of personal epistemology in face of adversity, and personal development (i.e. participatory appropriation). This can be suggested based on students’ appraisement about how knowing with which they have previously engaged (particularly at campus settings) is useful when responding to workplace challenges, and that they had the ability to engage both conceptual and procedural knowing while fulfilling occupational obligations. According to the perspectives on personal engagement, increased emphasis on personal epistemologies as defined here can help create a cohesive learning strategy for individuals. In respect to the students’ expositions of their learning, these are useful in biology education, where somewhat complex conceptual representations and procedures can be enacted, and otherwise engaged with through working (see for instance the many levels of expert knowing required to complete the students’ research project on tunicates).

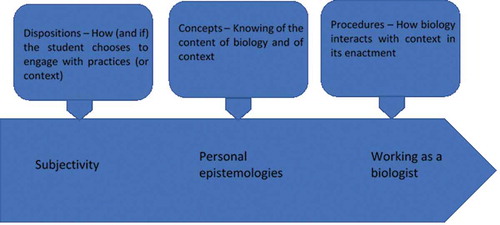

Finally, the situated nature of the students’ experiences should not be undervalued when considering individual students’ development of personal epistemologies. Students finding themselves in circumstances both novel and exhilarating, is fully in line with theories on situated learning. Within a sociocultural framework, expositions of context are also expositions of learning (Rogoff, Citation2003). Given the wide variation in a circumstance in the biology students’ workplace, it is crucial to recognize that this is also an epistemological expression. It is significant that the elicited accounts of learning go to great detail about how new contexts affords access to new practices and thereby new learning. We propose a conceptual model to illustrate the contributions of knowing in context to the students’ personal epistemologies and their development towards becoming a biologist (see Figure ).

The conceptualization in Figure should be of particular interest in tertiary education pedagogies, as students’ dispositions are increasingly emphasized alongside conceptual and procedural knowing (Hodkinson, Biesta, & James, Citation2008). By providing links between various dimensions of knowing and dispositions as they are engaged in work placements, blogs can be a fruitful avenue through which these aspects of knowing can be facilitated and assessed. Furthermore, we did not aim to find whether or not work placements provide specific outcomes in comparison to campus-based pedagogical measures. However, we suggest ways in which work placements provide specific experiences. In these experiences, students find their conceptions of knowing developed and they consider ways in which their overall education is useful in various occupations.

Figure 2. Conceptual overview of students’ development of personal epistemologies in their trajectory to develop as biologists in work. Context interplays in all dimensions and reflects the sociocultural (i.e., situated) theorizing that is foundational to understand stundets’ development of personal epistemologies in work. Subjectivity refers to individuals’ standpoint, and the life history that proffers them in their trajectory towards engaging with biology knowing

10. Conclusions and limitations

The present study has shown how blogs can function to explore students’ personal epistemologies. Through the students’ accounts, important aspects of learning during work placements have become clearer. These aspects emerged as students’ engaged and enacted their work in the face of adversity, such as project setbacks and financial limits. The participatory appropriation in which students engaged in their work. And their accounts regarding the relationship between campus and workplace epistemologies. Through these themes, students engaged in specific applications and integrations in their knowing. They also gave accounts of knowing in relation to personal values, and volition to engage with specific sets of practices (and knowing). This shows the primacy of individuals’ dispositions as they come to engage with work. The advancements presented by work can also respond to challenges presented by the diverse dimensions of biology knowing (all those practices the students come into contact with during their education), and thus assuaging the partitioned conception of learning (i.e., weak connection between work and campus) that can arise in science education.

In ending, we wish to highlight specific limitations to our study. First, we base our findings on students’ self-reported experiences. As argued in our method section, we deem blog accounts valuable without including other measures to further question students on their experiences, such as semi-structured interviews. Second, the public nature of blogs can skew students’ accounts in favour of less problematic, but nonetheless salient experiences in their work placements. However, we do not wish to engage various experiences as more or less interesting and students’ accounts should be taken as honest. Third, more in-depth examination of various workplaces could lead to deeper understandings of particular students’ experiences. This calls for future ethnographic-type studies on biology students’ experiences in work placements.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Torstein Nielsen Hole

Torstein Nielsen Hole is a PhD student at the Department of Bioscience, University of Bergen. He has a background in educational science at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, and the department of education, University of Bergen (UoB).

G. Velle

G. Velle is a researcher at NORCE Norwegian Research Centre, and a professor at the Department of Bioscience (UoB).

H. Riese

H. Riese is an associate professor at the Department of Education (UoB).

A. Raaheim

A. Raaheim is a professor of higher education at the Department of Education (UoB).

A. L. Simonelli

A. L. Simonelli is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Bioscience (UoB).

All authors are involved in the Center of Excellence in Biology Education (bioCEED), in which developers from education science, biology, and other academic disciplines work together to evolve higher education pedagogies. One of the main aims of bioCEED is the integration of content knowledge, societal developments, and practical work in biology education.

References

- Berland, L., & Crucet, K. (2016). Epistemological trade-offs: Accounting for context when evaluating epistemological sophistication of student engagement in scientific practices. Science Education, 100(1), 5–29. doi:10.1002/sce.21196

- Billett, S. (2001). Learning in the workplace: Strategies for effective practicei. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

- Billett, S. (2009). Personal epistemologies, work and learning. Educational Research Review, 4(3), 210–219. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2009.06.001

- Billett, S. (2014). Integrating learning experiences across tertiary education and practice settings: A socio-personal account. Educational Research Review, 12, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2014.01.002

- Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (2001). Knowledge and organization: A social-practice perspective. Organization Science, 12(2), 198–213. doi:10.1287/orsc.12.2.198.10116

- Chaiklin, S., & Lave, J. (1996). Understanding practice - perspectives on activity and context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Collins, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the crafts of reading, writing and mathematics. In Ed. (L. B. Resnick), Knowing, learning and instruction: Essays in honour of Robert Glaser (pp. 453–494). Hillsdale, New Jersey, Hove, & London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. doi:10.5840/thinking19888129

- Costley, C. (2011). Workplace learning and higher education. In M. Malloch, L. Cairns, K. Evans, & B. N. O’Connor (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of workplace learning (pp. 395–406). London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi:10.4135/9781446200940.n29

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. doi:10.1177/1524839915580941

- Deng, F., Chen, D.-T., Tsai, -C.-C., & Chai, C. S. (2011). Students’ views of the nature of science: A critical review of research. Science Education, 95(6), 961–999. doi:10.1002/sce.20460

- Dewey, J. (2011). Democracy and education. Hollywood: Simon & Brown.

- Duguid, P. (2005). “The art of knowing”: Social and tacit dimensions of knowledge and the limits of the community of practice. Information Society, 21(2), 109–118. doi:10.1080/01972240590925311

- Eraut, M. (2004). Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 26(2), 247–273. doi:10.1080/158037042000225245

- Gherardi, S. (2009). Community of practice or practices of a community? In S. J. Armstrong & C. V. Fukami (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of management learning, education, and development (pp. 514–530). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi:10.4135/9780857021038.n27

- Hew, K. F., & Cheung, W. S. (2013). Use of Web 2.0 technologies in K-12 and higher education: The search for evidence-based practice. Educational Research Review, 9, 47–64. doi:10.1016/J.EDUREV.2012.08.001

- Hine, C. (2000). Virtual ethnography. London: SAGE.

- Hodkinson, P., Biesta, G., & James, D. (2008). Understanding learning culturally: Overcoming the dualism between social and individual views of learning. Vocations and Learning, 1(1), 27–47. doi:10.1007/s12186-007-9001-y

- Hodkinson, P., & Hodkinson, H. (2004). The significance of individuals’ dispositions in workplace learning: A case study of two teachers. Journal of Education and Work, 17(2), 167–182. doi:10.1080/13639080410001677383

- Hofer, B. K. (2001). Personal epistemology research: Implications for learning and teaching. Educational Psychology Review, 13(4), 353–383. doi:10.1023/A:1011965830686

- Jackson, A. Y., & Mazzei, L. A. (2018). Thinking with theory. A new analytic for qualitative inquiry. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 717–737). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Jones, M., & Ryan, J. (2014). Learning in the practicum: Engaging pre-service teachers in reflective practice in the online space. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 42(2), 132–146. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2014.892058.

- Kelly, G. J., & Licona, P. (2018). Epistemic practices and science education. In M. Matthews (Ed.), Science: Philosophy, history and education (pp. 139–165). Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-62616-1_5

- Kennedy, M. (2015). Knowledge claims and values in higher education. In M. Kennedy, S. Billett, S. Gherardi, & L. Grealish (Eds.), Practice-based Learning in Higher Education (pp. 31–45). Dordrecht, Heidelberg, New York & London: Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9502-9_3

- Knorr Cetina, K. (1999). Epistemic cultures: How the sciences make knowledge. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Kozinets, R. V. (2015). Netnography : Redefined. London: SAGE.

- Kuhn, T. S. (2012). The structure of scientific revolutions (4th ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.1119/1.1969660

- Kwon, H. W. (2017). Expanding the notion of agency: Introducing grit as an additional facet of agency. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work (pp. 105–120). Cham: Springer, Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-60943-0_6

- Lave, J. (1997). The culture of acquisition and the practice of understanding. In D. Kirshner & J. A. Whitson (Eds.), Situated cognition: Social, semiotic, and psychological perspectives (pp. 63–82). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Loftus, S., & Higgs, J. (2010). Researching the individual in workplace research. Journal of Education and Work, 23(4), 377–388. doi:10.1080/13639080.2010.495712

- Markham, A. N. (2018). Ethnography in the digital internet era: From fields to flows, descriptions to interventions. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (pp. 650–668). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Mok, K. H., & Neubauer, D. (2016). Higher education governance in crisis: A critical reflection on the massification of higher education, graduate employment and social mobility. Journal of Education and Work, 29(1), 1–12. doi:10.1080/13639080.2015.1049023

- Nicolini, D. (2012). Practice theory, work, and organization: An introduction (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University press.

- Parker, L. E., & Morris, S. R. (2016). A survey of practical experiences & co-curricular activities to support undergraduate biology education. The American Biology Teacher, 78(9), 719–724. doi:10.1525/abt.2016.78.9.719

- Piaget, J. (1964). Part I: Cognitive development in children: Piaget. Development and learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2(3), 176–186. doi:10.1002/tea.3660020306

- Pink, S., Horst, H., Postill, J., Hjorth, L., Lewis, T., & Tacchi, J. (2015). Digital ethnography: Principles and practice. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Pink, S., & Morgan, J. (2013). Short-term ethnography: Intense routes to knowing. Symbolic Interaction, 36(3), 351–361. doi:10.1002/symb.66

- Postill, J. (2016). Remote ethnograpy: Studying culture from afar. In L. Hjorth, H. Horst, A. Galloway, & G. Bell (Eds.), The Routledge companion to digital ethnography (pp. 61–70). London, UK: Routledge. doi:10.1128/AAC.03728-14

- Rennie, L. J. (2014). Learning science outside of school. In S. K. Abell & N. G. Lederman (Eds.), Handbook of research on science education Volume II (pp. 120–144). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Rogoff, B. (1995). Observing sociocultural activity on three planes: Participatory appropriation, guided participation, and apprenticeship. In J. V. Wertsch, P. Del Río, & A. Alvarez (Eds.), Sociocultural studies of mind (pp. 139–164). Los Angeles, CA: Cambridge University Press.

- Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford: Oxford University press.

- Roth, W.-M. (2003). Scientific literacy as an emergent feature of collective human praxis. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 35(1), 9–23. doi:10.1080/00220270210134600

- Roth, W.-M., & Lee, S. (2004). Science education as/for participation in the community. Science Education, 88(2), 263–291. doi:10.1002/sce.10113

- Roth, W.-M., & Roychoudhury, A. (1994). Physics students’ epistemologies and views about knowing and learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 31(1), 5–30. doi:10.1002/tea.3660310104

- Ryle, G. (2009). The concept of mind. London, UK: Routledge.

- Scholz, R. W., Steiner, R., & Hansmann, R. (2004). Role of internship in higher education in environmental sciences. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(1), 24–46. doi:10.1002/tea.10123

- Schommer, M. (1990). Effects of beliefs about the nature of knowledge on comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(3), 498–504. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.82.3.498

- Singer, S. R., Nielsen, N. R., & Schweingruber, H. A. (2013). Biology education research: Lessons and future directions. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 12(2), 129–132. doi:10.1187/cbe.13-03-0058

- Snee, H. (2008). Web 2.0 as a social science research tool. British Library, 4(November), 1–34.

- Stoszkowski, J., & Collins, D. (2017). Using shared online blogs to structure and support informal coach learning-part 1: A tool to promote reflection and communities of practice. Sport, Education and Society, 22(2), 247–270. doi:10.1080/13573322.2015.1019447

- Velle, G., Hole, T. N., Førland, O. K., Simonelli, A. L., & Vandvik, V. (2017). Developing work placements in a discipline-oriented education. Nordic Journal of STEM Education, 1(1), 294–306. doi:10.5324/njsteme.v1i1.2344