Abstract

Teacher autonomy (TA) in parallel with learner autonomy affects the standards of education. In this survey, the relationship between teachers’ autonomy was focused on along with second language teaching styles and personality traits. To respond to three research questions, the required data were gathered through convenience sampling by online distributing three sets of questionnaires, namely Pearson and Moomaw’s Teacher Autonomy Scale, Grasha’s Teaching Style Inventory, and Costa and McCrae’s NEO-Personality Inventory, which was responded by 156 EFL teachers, including both males and females. Then, SPSS 26 and AMOS 24 were used to analyze the data and the following results were obtained: (a) four items out of the five sub-constructs of a teaching style as well as four of the five sub-constructs of the personality traits were significant predictors of the teachers` autonomy; and (b) the mean score of the male teachers` overall autonomy was higher than that of the female teachers. Meanwhile, the findings are best suited for EFL academics who want to be more autonomous but are unaware of the influence it has on their teaching styles and personality traits.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

From the mid-1990s till today teacher autonomy has been defined and analyzed in different dimensions by many scholars and researchers, but its role in learner autonomy cannot be neglected. An autonomous teacher is the one who first, has enough freedom and responsibility in administering his own teaching curriculum and then, be acquainted with the learner’s psychology, learning styles and strategies, learning personal plans, and learning evaluation process to develop an autonomous learner. For becoming an autonomous teacher, there are many factors that must be considered. In this study, three of them as teaching styles, teacher’s personality, and gender were focused. Findings were displayed in a three-dimensional model presenting significant relationships among these features. Results can be practical for EFL teachers and learners, educators, and curriculum planners, all who want to boost the quality of language teaching and learning.

1. Introduction

In the traditional era, the main focus of teaching was more on teacher-centered methods to just transmit data to learners; however, today academics are inspired to construct their theories of action by using a lot of innovative methods of teaching a second language within the best manner which suits with learners’ learning process. The crucial role of teachers in students’ learning process is proven sure enough (e.g., Akbari et al., Citation2008; Saha & Dworkin, Citation2009), and teachers are valuable assets to the education system, notably in an exceedingly post-method era that has introduced a replacement definition for a “teacher” and a new responsibility for him. This is partially what Wallace (Citation1991) has also noticed that “The way to behave reflectively, the way to analyze and assess their teaching acts, the way to initiate changes in their classroom and the way to observe the consequences of such changes” (as cited in Kumaravadivelu, Citation2006, p. 178) are what a post-method teacher faces.

Kumaravadivelu (Citation2001) remarked that language academics should transcend the constraints of methods and not be simply the consumers of the theories projected by others, and “construct their context-sensitive pedagogical data which will build their observance of every day teaching a worthy endeavor” (p. 541). For this to achieve, academics ought to observe, hear, and mirror their daily teaching practices finding strengths and weaknesses of the methods and strategies utilized within the educational environment. Also, they should have a holistic understanding of what happens within the class, assess outcomes, establish issues, and notice solutions that resulted in planning the applicable techniques which fit the students’ wants in the classroom.

This is where autonomous teachers are needed more than the ones who suffice to run through what their bosses, supervisors, and guidebook writers instruct them to do. To highlight this issue, Castle (Citation2004), Ingersoll (Citation2007), Pearson and Moomaw (Citation2006), and Webb (Citation2002), among others, have underlined the importance of the professional autonomy in the enhancement of the teachers’ role in education.

By being autonomous, we here mean being independent in and having control over the choices a teacher can make to accomplish his duty in classrooms. However, Piaget’s interpretation of autonomy is “ego directed behavior, free from arbitrary outer pressures or from irrational inner pressures” (as cited in Peck & Havighurst, Citation1960, p. 17). Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (Citation2002) also defined autonomy as “the quality of being self-governing” (p. 78).

Moreover, there are many other viewpoints about teacher autonomy; however, all of these theories and definitions should be aimed at the teacher’s and learner’s development and success. In the 1990s, the first definition of the teacher autonomy was presented by Little (Citation1995) as the “teachers’ capacity to engage in self-directed teaching” in foreign language education (p. 176). In Oxford Dictionaries (Citation2015), autonomy is derived from the Greek word autonomous meaning ‘having its own laws’.

However, some others believe that the teacher autonomy may be the freedom of choosing curricular directions with no supervision or interference. Aoki (Citation2002), for instance, regarded teacher autonomy as a teacher’s capacity and responsibility in selecting his own teaching process. Javadi (Citation2014) called teacher autonomy a kind of skill in which teachers can make their teaching condition without any limitations. The main issue of autonomous teaching is, for teachers, to have freedom in creating vital choices in the process of teaching to meet the students’ needs and necessities. According to Singer (Citation2006), the teachers’ autonomy relates to their control over their syllabus, pedagogy, assessment, student discipline, and classroom setting.

Still others have taken into account the teacher’s capability to guide the students’ autonomy. To Yan (Citation2010), teacher autonomy is his ability to control knowledge, skills, and attitudes in the learner’s acquisition of a language. Keeping in mind this definition, Esfandyari (Citation2017) warned that if teachers act autonomously, this autonomous acting will be conveyed to their learners, too. Moomaw (Citation2005) also demonstrated that teachers must invent their rules under the classroom’s necessities. Besides, an autonomous teacher should have the ability to recognize the learners’ needs and to develop them toward autonomy (Reinders & Balcikanli, Citation2011). Therefore, the teacher’s autonomy can lead to making a good environment for students to acquire and practice knowledge autonomously (Mollaei & Riasati, Citation2013).

On the other hand, Hanson (Citation1991) prompted that if a teacher needs his own autonomy over an educational method, he ought to have so much experience in particular fields and even have the right of organizing his teaching method. Benson (Citation2001) conjointly targeted autonomy as the “ideas of professional freedom and independent professional development” (Citing in McGrath, Citation2000, p. 174). According to Esfandyari (Citation2017) if teachers have the needed autonomy, they will be more motivated and consent since they can select their teaching styles and materials as well as the evaluation methods. If academics do not feel they have the autonomy, then this autonomy does not make sense (cited in Skinner, Citation2008).

However, some teachers cannot get the entire autonomy and act dependently (Arkott, Citation1968). Hughes (Citation1975), Sayles and Strauss (1966), and Willner (Citation1990) in confirming this statement found out that some academics are compelled to have guidance from the leadership of the school or institute they work in, and prefer to try what are told to them.

In Iran, and perhaps in many of the other countries, most English institutes and high schools have some issues with their teachers’ methodologies and force them to adapt their rule-based curricula. In such a context, academics lose the right to form their own classroom decisions due to the learners’ individual differences. This is happening while a considerable amount of literature exists that links teacher autonomy as a significant variable to factors such as (a) job satisfaction, (b) professionalism, (c) motivation, (d) empowerment (e) school climate, and (f) stress. Most importantly, “teachers’ activities are the main component in any respect steps of education” (Saha & Dworkin, Citation2009).

Accordingly, teachers ought to build a balance between a method-based pedagogy imposed on them and a methodology which is jury-rigged by them. Since, it is the teacher who deals with the psychology of the learner and is aware of the learner’s learning strategies. Nevertheless, today, those teachers are needed who are generally independent and active individuals with different identities and personality traits, and are also able to make their own decisions for the teaching process. Having such a capability, they can take into consideration the learners’ wants and needs through their practices and adopted teaching styles. Akbari et al. (Citation2005) considered a teaching style as an affective component in the teacher’s development and, as also Cooper (Citation2001) offered, in keeping with the teacher’s personality.

Consequently, aiming to seek out the relationship between the EFL teachers’ autonomy and their teaching styles and personality traits, we organized this correlational study by online-distributing the three below-mentioned questionnaire among Iranian EFL teachers. Therefore, by keeping an eye on the results of past studies (See Baradaran, Citation2016; Baradaran & Hosseinzadeh, Citation2015; Mahmoodi, Citation2017; Reeve et al., Citation2017; Larenas et al., Citation2010; Zhang, Citation2007 among others), we designed the following research questions:

What is the relationship between an EFL teacher’s autonomy and his/her teaching styles?

What is the relationship between an EFL teacher’s autonomy and his/her personality traits?

Which group of teachers, males or females, is generally more autonomous?

Based on the past studies, we hypothesize some correlations, either positive or negative, to be between our chosen variables. In this regard, Piaget believed that autonomy comes from within and results from a “free decision”. It is of intrinsic value and the morality of autonomy is not only accepted but obligatory. For Piaget, the term autonomous can be used to explain the idea that rules are self-chosen. By choosing which rules to follow or not, we are in turn determining our own behavior (Sugarman, Citation1990).

Lamb and Simpson (Citation2003, p. 56) explicated that teacher autonomy is thought to be a capability for “escaping from the treadmill” of our own undisputed beliefs concerning however things ought to be done. However, one of the difficult tasks of today’s teachers is being autonomous within curriculum obligations and constraints. Although curriculum determines many instructions for teachers which involve the analysis of philosophy, social forces, needs, goals and objectives, treatment of data, human development, and learning process, it faces a variety of challenges in the process of development, as it disregards the mediator role of teachers. As Adamson and Sert (Citation2012) stated if autonomy is accomplished effectively, it will be an all-pervading philosophy of life and it will shape the personal behavior and cognition within community

On the other hand, by styles we mean the teachers’ dominant tendencies in presenting materials to their students. One’s selection of styles depends on what (s)he would like to teach, whom (s)he tends to teach, and also the level of competence expected. Larsen-Freeman (Citation2000) suggested that teachers resist or argue against the imposition of some methods and are drawn to the others. Therefore, there are mismatches between language policy and also the actual run-through in class. Besides, considering the relationship between autonomy and teaching styles helps teachers to become acquainted with the strengths and weaknesses of the particular style(s) they use in classroom. It also makes them aware of the need for administering a specific style for a specific learner in a specific learning situation.

2. Literature review

In relation to this study, some other similar researches have been done before which are mentioned hereafter.

Aoki (Citation2002) aknowledged that an autonomy-supportive teaching style is associated positively with better school adjustment, higher grades, and more school engagement (Aoki, Citation2002).

In another study, Baradaran (Citation2016) reached no significant correlation between female EFL teachers’ teaching styles and their autonomy. Similarly, in another survey on the relationship between Iranian EFL teachers’ teaching styles and their curriculum and general autonomy, Baradaran and Hosseinzadeh (Citation2015) concluded that the relationship between curriculum autonomy and the teachers’ expert, personal model, and delegator styles was negative; Mahmoodi (Citation2017) also confirmed that teachers’ autonomy and their various teaching styles were not significantly related to each other.

Regarding the relationship between teaching styles and personality traits, findings by Reeve et al. (Citation2017) suggested a robust relationship between personality and teachers’ motivating styles. The results of Larenas et al. (Citation2010) indicated that the public sector participants show a facilitator teaching style and an extrovert personality type, whereas the private sector participants reveal a more authoritative teaching style and an introverted type of personality. The results of Zhang’s (Citation2007) studies also affirmed a significant contribution between teachers’ personality traits measured by Costa and McCrae`s (Citation1992) NEO Five-Factor Inventory and teachers’ teaching styles.

Paiva and Braga (Citation2008) argued that autonomy is inextricably linked to its environment since in the perspective of complexity, it encompasses properties and conditions for complex emergence. Its dynamic structure governs the nature of its interactions with the environment in which it is nested (Baradaran, Citation2016).

As it can be observed, there are many contradictory statements concerning autonomy and its contributions to education which signifies the importance of doing more studies. On the other side, the teacher’s internal characteristics have today found a valuable and affective position in both teaching and learning pedagogical development, as an example Galluzzo (Citation2005) believed that the teacher’s personality traits are the foremost vital factors about the learners’ learning. It is clear each teacher has a particular character and temperament, therefore, his personality could also be mirrored in his adopted approach, methods, and specific styles by which he may prefer to manage the class and teach the scholars. Since teachers are the key components in pedagogic success, there is an urgent need to apprehend them and their personality factors. Knowing and categorizing the teacher’s personal and psychological factors on the premise of varied classifications are a part of the complicated areas of a teacher preparation for an EFL classroom (Saha & Dworkin, Citation2009).

2.1. Teaching styles

The choice of teaching styles is within the teachers’ control (Smith, Citation2005). The teaching style is the one that guides the teaching process and also has effects on students’ learning strategies. Teaching styles can be varied based on the factors like the context of teaching, the subject materials, or the due curriculum and the learners’ learning trends. Brew (Citation2002) claimed that the factors like gender, the educational level, and the learning process may affect the teaching styles Grasha (Citation2002) suggested that like an artist’s palette composed of different colors, the teachers’ styles differ from each other; they can be integrated, though. Here, the Grasha’s (Citation2002) Teaching Style Scale is reviewed along with its five sub-constructs which are expert, formal authority, personal model, facilitator, and delegator.

2.1.1. Expert style

In this style, those knowledgeable and experienced academics are focused on who convey the proper information and are well ready within the discipline. The goal is to transmit information to students to prepare them for assignments, exams, and further studies. This model is often harmful to less experienced students and as Grasha (Citation1996, p. 2) emphasized “it is often daunting to them”. Also, it considers facts and figures, not the thought processes in reaching conclusions and outcomes; so it is helpful a lot for mature subjects and categories in higher education.

2.1.2. Formal authority style

The academics who employ this method differ totally from the expert ones, since they are considered not only to be knowledgeable but also they may supply their students with negative or positive feedback, setting their goals and expectations. Its focus is on the commonplace ways in which the structures needed by students can be provided. However, this may be a drawback, since it can cause rigid, standardized, and fewer versatile ways in which students are managed. This style is more teacher-centered and targets on the dominant actual transmission of contents without any requirement for the students’ participation in classroom. It will work effectively in studies like law or music, wherever there are established rules that require to be followed.

2.1.3. Personal model style

In this form of style, teaching is done by personal examples, providing directions, having an epitome for how to think and behave, guiding students to try things, and inspiring them to observe and follow the instructor’s approaches.

Direct observations and active expertise are involved. The disadvantage of this method is that teachers attempt to run their way as the best one and if students cannot live up to the standards, it will cause them to feel inadequate. In the higher education settings, this methodology may work well because students are engaged on an equivalent level and have a decent grasp of the fabric.

2.1.4. Facilitator style

This teacher–student interaction style specializes in creating students freelance. The teacher acts as a helper and advisor as he asks queries, explores and helps students think independently, takes a lot of responsibility in their learning procedure, has a lot of flexibility within the class, and focuses on their goals and wishes; therefore, the role of the teacher is much of a consultative one. Not using this style in an exceedingly appropriate situation may be time-consuming. This style works well in small settings or superior and graduate courses.

2.1.5. Delegator style

Delegator teachers are those who make students autonomous. Therefore, students can work independently within the class, and the teacher may be a resource at the request of the learner. The disadvantage of this style is that students will become anxious as they are not prepared for such autonomy. “It might contribute to students’ anxiety as they will tend an excessive amount of autonomy before being ready” (Grasha, Citation1996, p. 11). This style facilitates students to be confident and independent learners and is great for higher-level studies wherever students have already got an acceptable level of knowledge.

2.2. Personality traits

In defining personality, Mayer (Citation2007) mentioned that each individual has an organized and developed system within himself representing the psychological actions of subsystems. Myers and McCaulley (Citation1985) emphasized on personality as the most desirable way fascinating for us to receive information, get energy, focus our attention, and make decisions with the outer world. In addition, personality supported by Matthews et al. (Citation2006) affected student’s behavior within the classroom and tutorial success, contributing to the relationships students have with their teachers and their classmates.

Personality of an individual is a vital issue of success in teaching (Brown, Citation2000), and it should meet students’ desires. Teachers’ temperament will replicate in their daily practices, the way to solve classroom issues, how they organize the class, their perception, and attention within the class. To improve their teaching styles and therefore the strategies in disciplining students, teachers ought to find out their personality traits.

Among several personality traits presented by theoreticians, the Costa and McCrae`s (Citation1992) personality model having five factors namely extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience was selected for this survey, which is the foremost wide accepted and used model of personality.

2.2.1. Extroversion

Extroverts as Rushton et al. (Citation2007) stressed are interested people in the external world, filled with energy, talk with others, and draw their attention to social teams. They are not quiet, low-key, or deliberate. They think aloud and are active.

2.2.2. Agreeableness

These types of people are in social harmony with others, more friendly, generous, and helpful. Being optimistic, they are getting along with others and are more likable ones.

2.2.3. Conscientiousness

These groups of individuals have purposeful planning and high levels of success. They are more reliable and intelligent.

2.2.4. Neuroticism

Neuroticists who deal with anxiety, depression, or anger may have a quite negative feeling. These individuals are more intense in reactions and feel that the usual situations are threatening.

2.2.5. Openness to experience

More imaginative, more creative, intellectually curious, aware of their feelings, appreciative of art, sensitive to beauty, and healthier are some dominant characteristics of this kind of people.

3. Method

According to the above-mentioned issues, the two-fold aim of this survey are clearly stated again. First, in an exceedingly second language context, i.e. Iran, we took into consideration the dominant teaching styles of teachers influenced by their autonomy which is in itself affected by the authority of institutes and high schools. Second, in this research, the teacher personality in a second language classroom was also focused on as it was thought to have a relationship with the teacher’s autonomy.

3.1. Participants and their educational contexts

To collect the needed data for this study, the three selected questionnaires were distributed among 170 Iranian EFL academics who 156 of them sent back their answers to the authors. Sixty-three of these participants were males and 93 were females with different university degrees e. g. B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. These academics had totally different years of teaching experiences ranging in years from 22 to 54, and they were employed by English language institutes, universities, state and private schools across Iran. The data sampling was supported by the researcher’s accessibility and availability through online social networks. It is worthy of note that before answering the questionnaire, participants were assured their personal information as well as their responses would be kept confidential. Also, they were requested to study and tick consent statement which shows their willingness of taking part in this research.

3.2. Instrumentation

Three instruments, i.e., questionnaires, were used to investigate the relationship between the teachers’ autonomy in one side and their teaching styles and personality traits on the other side:

3.2.1. Teacher Autonomy Scale (TAS)

This scale presented by Pearson and Moomaw (Citation2005) includes 18 items with these 5 options: always true for me, often true for me, sometimes true for me, almost never true for me, and never true for me. Conjointly, this need to be mentioned that this questionnaire was administrated before in different investigations and it is the foremost documented one in many researches (See Lepine, Citation2007; Saljoughi & Nemati, Citation2015, among others); Thus its content validity and reliability are high. Moomaw (Citation2005) confirmed acceptable construct validity and reported internal consistency as r = 0.83. The reliability of the Teacher Autonomy Scale acquired for this research is r = 0.92.

3.2.2. Teaching Style urvey (TSS)

The second questionnaire, developed by Grasha (Citation1996), is the most documented one (See Baradaran, Citation2016; Ghanizadeh et al., Citation2016; Lucas, Citation2005 among others), and includes 40 items each of which targets one of the five mentioned subcategories of teaching styles. For instance, Items numbered 1-6-11-16-21-26-31-36 refer to the expert-style questions; formal authority style includes the questions numbered 2-7-12-17-22-27-32-37; questions numbered 3-8-13-18-23-28-33-38 target the personal model style; the questions of the facilitator style are 4-9-14-19-24-29-34-39; and the remaining items which are 5–10-15-20-25-30-35-40 signify the delegator style. The range of responses for each question is a five-point Likert rating scale as strongly disagree, moderately disagree, undecided, moderately agree, and strongly agree. For this instrument, reported by Grasha (Citation1996), the acceptable reliability is r = 0.72; and in this study, the gained reliability of Teaching Style Survey for the five subscales ranges from 0.78 to 0.91 which can be called acceptable.

3.2.3. NEO PI-R

Costa and McCrae (Citation1992) compiled the NEO Personality Inventory questionnaire measuring the personality traits by 60 questions each one of which targets on of the five sub-constructs as: extroversion (Qs: 2-7-12-17-22-27-32-37-42-47-52-57), agreeableness (Qs: 4-9-14-19-24-29-34-39-44-49-54-59), conscientiousness (Qs: 5–10-15-20-25-30-35-40-45-50-55-60), neuroticism (Qs: 1-6-11-16-21-26-31-36-41-46-51-56), and openness to experience (Qs: 3-8-13-18-23-28-33-38-43-48-53-58). A Likert scale including five options was designed for each question as strongly disagree, disagree, neither, agree, and strongly agree.

Reported by Costa and McCrae (Citation1992), McIlveen et al. (Citation2013) offered internal consistency coefficients between 0.72 and 0.88. The reliability of the Personality Inventory for the five-subscales of this research ranges from 0.74 to 0.92 which is an acceptable range.

3.3. Data collection procedure

After distributing three questionnaires among EFL teachers and collecting the required data, their teaching styles and major personality tendencies were attained by employing descriptive statistics. Pearson Product Moment Correlation was used to investigate the attainable relationship between the teachers’ autonomy and the five sub-categories of their teaching styles. Similarly, another Pearson Correlation was run to seek out the type of relationship between the participants’ autonomy and their five sub-categories of personality traits.

3.4. Data analysis

First, the normality of data distribution was tested by using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Then, an independent-samples t-test came to be used to investigate the difference between male and female English academics regarding their autonomy. After that, the reliability of data was gained by Cronbach Alpha analysis. At last, Goodness-of-Fit Indices was calculated for the interrelationship between teachers’ autonomy and their teaching styles and personality traits. All the statistical analysis of the study were done by SPSS 26, AMOS 24, and SEM modeling. Tables and figures were applied to represent the results of both descriptive and inferential statistical analysis.

4. Results

Three major hypotheses evolved from the research questions and therefore the literature review. For a straightforward review, after the data analysis, the acquired results were categorized regarding the three research questions. Below, the findings illustrated by the tables and figures are followed by some elaborated descriptions.

4.1. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test

This test was used to attain the normality of the data distribution that is to understand whether the distribution deviates from a comparable normal distribution or not. If p > 0.05, which is significant, it implies a normal distribution. On the other hand, p < 0.05 indicates an abnormal distribution.

The results of Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for the five sub-constructs of second language teaching styles, the five sub-constructs of personality, and autonomy are illustrated by .

Table 1. The results of K-S test

It is clear that for all variables in this table, the sig value is >0.05, which shows the normal distribution of all variables.

4.2. Descriptive statistics

In as it is observed, the number of participants (156), the gained maximum and minimum scores, the mean, and the standard deviation are mentioned for each of the five sub-constructs of personality.

Table 2. The descriptive statistics of the sub-constructs of personality

According to the designer of this personality test, the possible range of scores for each of the sub-constructs is between 12 and 60. This means that 12 questions out of the whole test refer to each personality trait, each question has five options scored from 1 to 5 points (five-point Likert scale), thus making a range of scores from 12 to 60 points. Therefore, according to the figures in , for instance, the lowest score (minimum) gained by the agreeableness sub-construct is 25 points and the highest (Maximum) is 59; the mean score 43.96 is also the average of all scores of agreeableness gained by each of the 156 participants. In this case, if we consider 12 points, the lowest, 36, the middest, and 60, the highest of all scores which can be gained by each personality sub-construct, the mean scores fallen in-between 12 and 36 indicate a low degree and the mean scores in-between 36 and 60 show a high degree of tendency toward the due sub-constructs.

In addition, the highest mean scores belong to extroversion and agreeableness and the lowest one goes to neuroticism. Disregarding if it can be generalized to the whole research population or not, according to the above indications, these mean scores indicate that most of our participants are likely to have relatively high and almost equal tendencies toward extroversion (44.27), agreeableness (43.96), conscientiousness (42.40) and openness (41.13). Also, by the mean score of (26.95), there is observed a very low degree of neuroticism, i.e. being threatened by one’s working environment.

Like , also represents the descriptive statistics of the participants’ five sub-constructs teaching styles.

Table 3. The descriptive statistics of the participants’ teaching styles

According to the designer of this instrument, each of the sub-constructs has a range of scores from 8 to 40 points. This means that, from the whole test, each 8 questions targets one of the style sub-constructs; each question has 5 options one of which needed to be chosen scored ranging from 1 to 5 (5-point Likert scale), thus making a range of scores from 8 to 40 for each sub-construct.

Therefore, according to the figures in , for instance, the lowest score (minimum) gained by the delegator sub-construct is 16 points and the highest (Maximum) is 35; the mean score 25.76 is also the average of all scores of this sub-construct gained by each of the 156 participants. In this case, if we consider 8 points, the lowest, 24, the middest, and 40, the highest of all scores which can be gained by each style sub-construct, the mean scores fallen in-between 8 and 24 indicate a low degree and the mean scores in-between 24 and 40 show a high degree of tendency to use the due style sub-constructs.

In addition, as the figures in indicate, the ranking of the average scores of the style sub-constructs is as follows: the facilitator standing on top (28.30), the expert on the second place (27.32), the delegator next (25.76), the model (24.97), and the formal authority on the last rank (24.44).

According to the above indications, the min, the max, and the mean score gained by the facilitator indicate most of our participants are likely to have relatively high tendency toward using this style sub-construct.

The descriptive statistics of the participants’ autonomy scores are shown in . The possible range of scores for this test is from 18 to 90 points, i.e. the test has 18 five-option questions dedicated from 1 to 5 points based on the chosen option.

Table 4. The descriptive statistics of TA scores

represents the minimum score for autonomy as 33 and the maximum score as 79. Moreover, the mean score is 56.55 with a standard deviation of 5.24.

4.3. The reliability of the questionnaires

The data obtained from the Cronbach’s alpha analysis are summarized in .

Table 5. The results of the Cronbach's alpha indexes after the reliability analysis

According to this table, the acquired indexes of Cronbach’s Alpha are acceptable for these three questionnaires and all of their variables.

The reliability of the Teaching Style questionnaire for the subscales ranges from 0.78 to 0.91 which is an acceptable range. Moreover, the reliability of the Personality Traits questionnaire for the subscales ranges from 0.74 to 0.92 which is an acceptable range, too. Finally, the reliability for the Autonomy scale with 18 items is 0.92.

4.4. Inferential statistics

Here, the results of the statistical analysis to answer the three research questions are shown in the following tables and figures:

To answer the first research question, the relationship between the teachers autonomy and each of the five teaching styles, namely expert, formal authority, personal model, facilitator, and delegator were analyzed and illustrated below.

summarizes the above-mentioned relationships concerning the participants’ autonomy and the second language teaching style sub-constructs as a whole.

Table 6. The correlation results of TA and SL teaching styles

The figures illustrated by show the relationships of different sub-constructs of teaching styles to each other in one side and each sub-construct to autonomy in the other side, illustrated in Figure 12, too. So, the highest relationship with autonomy belongs to the facilitator style (r = 0.63, p < 0.05), and the lowest relationship with autonomy belongs to the formal authority style (r = −0.09, p > 0.05).

In addition, presents a significant relationship (r = 0.46, p < 0.05) between the expert sub-construct and the participants’ overall autonomy which indicates a positive correlation. also shows the scatter plot of the relationship between these two variables.

offers a positive significant relationship (r = 0.09, p > 0.05) between the formal authority and overall autonomy. also shows the scatter plot of the relationship between these two variables.

Moreover, indicates a positive significant relationship (r = 0.54, p > 0.05) between the personal model and the overall autonomy. Also, shows the scatter plot of these two variables’ relationship.

Again, there is a positive significant relationship (r = 0.63, p > 0.05) between the participants’ facilitator style and their overall autonomy shown by . shows the scatter plot of the relationship between the facilitator style and the overall autonomy.

Illustrated by , a positive significant relationship (r = 0.55, p > 0.05) is there between the delegator style and overall autonomy. also shows the scatter plot of the relationship between these two variables.

In response to the second research question, the Pearson correlation was used to find the relationship between the teachers’ autonomy and each of the five personality sub-constructs mentioned above. summarizes the teachers’ autonomy and their personality traits’ Correlation.

Table 7. The results of the correlation between TA and personality traits

According to the above results, among the five sub-constructs of personality traits, the highest correlation belongs to the relationship between autonomy and extroversion (r = 0.65, p < 0.05), and the lowest one belongs to the relationship between autonomy and neuroticism (r = −0.21, p < 0.05). Additionally, the correlation between the different sub-constructs of personality is also shown in the above table (Consider the negative correlations between neuroticism and the other sub-constructs).

As said above, a positive significant relationship (r = 0.65, p > 0.05) exists between extroversion and overall autonomy. also shows the scatter plot of the relationship between extroversion and overall autonomy.

indicates a positive significant relationship (r = 0.42, p > 0.05) between agreeableness and overall autonomy. also shows the scatter plot of the relationship between these two variables.

As shown by , there is a positive significant relationship (r = 0.47, p > 0.05) between conscientiousness and overall autonomy. Below, also shows the scatter plot of the relationship between these two variables.

Moreover, shows a negative significant relationship (r = −0.21, p > 0.05) between neuroticism and overall autonomy. Also, shows the scatter plot of the relationship between these two factors:

As the last one of the correlations between TA and each of the five personality sub-constructs, there is also a positive significant relationship (r = 0.41, p > 0.05) between openness to experience and overall autonomy, shown in . In addition, shows the scatter plot of the openness to experience and overall autonomy’s relationship.

As another step taken toward accomplishing our statistical analysis, an independent-samples t-test was performed to investigate the last research question. shows the descriptive statistics of the male and female teachers’ mean scores of their overall autonomy in two groups. also represents the findings of the independent-samples t-test for their overall autonomy as well.

Table 8. The descriptive statistics of the male and female teachers’ scores of autonomy

Table 9. The results of independent-samples t-test for autonomy

As indicates, the number of the male teachers (63) is less than that of the female teachers (93). However, the male teachers’ mean score of overall autonomy (63.44) is higher than that of the female teachers (51.88). A t-test was done to recognize that these differences are significant or not. In , the results of the independent-samples t-test are given for the participants’ autonomy.

shows a significant difference between two genders’ autonomy (t = −5.85, p= .000).

5. Discussion

In order to confirm the interrelationships among teachers’ autonomy, and their adopted second language teaching styles and personality traits, a path analysis explaining the directed dependencies among our collections of variables was employed using AMOS 24 software. This analysis is a part of SEM modeling with a structural model not a measurement one. To evaluate the model fitness, these indices were used:

Chi-square magnitude which should not be significant,

Chi-square/df ratio which should be lower than 2 or 3,

NFI: Normed Fit Index,

GFI: Good Fit Index,

CFI: Comparative Fit Index with the cut value greater than 0.90,

RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error about 0.06 or 0.07.

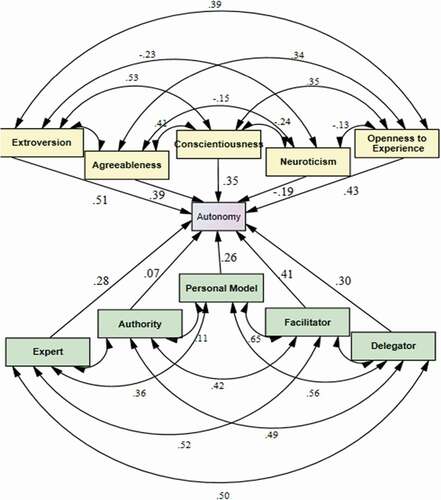

shows the model of the interrelationships among the participant teachers’ autonomy and their adopted second language teaching styles and personality traits.

Figure 11. The model of the interrelationships between teachers’ autonomy, second language teaching styles, and personality traits

A number of fit indices were examined to evaluate the model fitness. In , the goodness-of-fit indices can be seen for the model of path analysis.

Table 10. The goodness-of-fit indices for the model

In this table, all the fit indices as df ratio (2.85), RMSEA (0.070), GFI (0.93), and CFI (0.90) have the acceptable fitness thresholds; therefore, the model in is in correspondence with the empirical data.

indicates that four out of the five sub-constructs of teaching styles are positive significant predictors of autonomy, i.e. the facilitator (B = 0.63, p < 0.05), the delegator (B = 0.55, p < 0.05), the expert (B = 0.46, p < 0.05), the personal model (B = 0.54, p < 0.05), leaving behind the formal authority by a non-significant correlation (B = −0.09, p < 0.05).

These results are in line with Kassaian and Ayatollahi (Citation2010) findings. They concluded that the facilitator and personal model styles—having a relatively high 0.75 correlation due to our statistics—were used more in communicative situations. However, the expert and formal authority styles—having an almost average 0.36 correlation due to our analysis—were more focused on in the content situations like text translation. In this regard, Esfandyari (Citation2017) mentioned that EFL teachers prefer the facilitator and personal model styles which lead to more learners’ autonomy. However, since these two are time-consuming, they have to be used in small settings or in the fittest situations. Besides, the results of Ghanizadeh et al.’s (Citation2016) research indicated that the personal model, facilitator, and delegator styles prevent teaching burnout, but the expert and authority styles have no effect on decreasing burnout.

According to Richards and Rodgers (Citation2014), these days the commander role of teachers is replaced by the facilitator one. Instead of being an expert or a knowledgeable teacher as Belcher (Citation2006), and Pearson and Moomaw (Citation2005) also expressed, the focus of teaching must be on the extroverted interacting teachers with consummate skills and independency. So, they must be familiar with the different teaching styles and personality traits as the two main factors.

On the other hand, our findings conflicts with Esfandyari’s (Citation2017) findings indicating that EFL teachers do not prefer to use the delegator style because their students do not like to study isolated without a close relationship with their teachers. Zhang (Citation2007) and Kassaian and Ayatollahi (Citation2010) also preferred not to use the delegator style, as their learners were not in favor of working independently and autonomously. Still, it is the delegator teachers who may make students more autonomous. However, they have to make sure that their students will not get anxious and stressful since they may not be confident and ready enough to be that much independent or autonomous.

As the data needed for this research were gathered from a combination of EFL teachers working for institutes, universities, and schools—of course to increase generalizability, it is not clear which type of styles was specifically used in each of these contexts. However, it can be generally inferred that EFL university and school teachers focus on expert style to convey more contents and knowledge to their learners, and also they stick to the delegator style to give more responsibility to them, as A. F. Grasha (Citation1996) also suggested. These groups are more rule-based and book-centered, and they try to convey knowledge to students and give them more homework and personal activities during the course; they tend to define a certain goal for themselves, follow their beliefs and perform their own decisions during the semesters without taking any attention to the student`s needs. English institutes’ teachers, however, emphasize on the facilitator style much more, showing that they are more autonomous than university and school teachers. They perform a wider variety of tasks and activities in the classroom to make more communications and interactions, as they are free from class-bound decisions. Reeve et al. (Citation2004) stated that if teachers use more autonomy supports, like using the facilitator style in their instructions, students will be engaged more in class activities.

Nevertheless, each teacher may select different styles of teaching suggesting that the styles are context-bound. (Karimi Moonaghi et al., Citation2010; McCollin, Citation2000; Rahimi & Nabilou, Citation2011; Wilkesmann & Lauer, Citation2015). As an instance, the same teacher may use the facilitator style in an English institute, but the expert style in school or university. Most of the autonomous teachers are not in favor of only one single particular teaching style or strategy; Wise (Citation1996), Vaughn and Baker (Citation2001) also confirmed the importance of applying different strategies, methods, and styles. Thompson (Citation1997) said that teachers may adapt to the teaching styles that feel better with them or have more experience and knowledge about them.

Considering the other aspect of this research, the findings of this research are consistent with Alibakhshi (Citation2011) which concluded that extroverted EFL teachers were the predominant personality type. As stated above, our statistics showed a relatively high 0.65 correlation between autonomy and extroversion besides placing on top of the other personality sub-constructs in terms of their correlation with teacher autonomy. More interestingly, not only has the neuroticism factor a negative relationship with autonomy (−0.19) but also it has some negative correlations with the other four sub-constructs of personality. This finding by itself has some important implications for teachers’ supervisors and the education authorities that they have to first eliminate whatever makes a teacher have stress, depression, anxiety and other negative feelings, even if it costs increasing their freedom and autonomy.

Likewise, Khodadady (Citation2010) suggested that among these five personality traits, agreeableness was not in a relationship with the features of a successful teacher. On the contrary, our statistical results indicate that not only is agreeableness correlated to the other four personality traits by 0.41, 0.43, 0.30, and −0.14 amounts but also it has an average 0.42 correlation with autonomy, too. This is also in harmony with the study by Reeve et al. (Citation2017) indicating that the levels of openness to experience and agreeableness have relationships with teachers’ autonomy-supportive motivating style.

Meanwhile, in a study by Akbari et al. (Citation2005), there was a significant difference between teaching styles and the Myers–Briggs Type Indicators of personality traits as each personality type represented a particular teaching style. Also, Behnam and Bayazidi (Citation2013) showed that the personality type was not a significant predictor of teaching styles. However, what is clear is that extroverted and open-to-experience teachers try to use more negotiations and social activities in their class making a more enjoyable condition for learning. These types of teachers use their freedom in choosing communicative styles of teaching to have an attractive process of learning. Still, some believe that the teachers with the traits of agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism also have little adherence among learners.

Taking steps into the gender-oriented debates and studies, Baradaran (Citation2016) conducted a single-gendered research and reached no significant correlation between female EFL teachers’ teaching styles and their autonomy. Simmilarly, Ololube (Citation2006) and Usop et al. (Citation2013) declared that no effect of gender was observed on teacher autonomy. Qashang’s (Citation2015) findings also showed that the teachers’ gender had no significant role in their autonomy sense. Besides, Behnam and Bayazidi’s (Citation2013) research showed no effect of gender on the teaching styles

On the other hand, according to our statistics, the mean score of the female teachers’ overall autonomy was interestingly 11.5 units lower than that of the male teachers, while, in number, females were 50% more than males. Considering the difference in numbers of the two groups, the difference in the mean scores can be very significant, which has led to an almost 7-point decrease in the autonomy average level of the whole participants as a single sample group. It can, therefore, be inferred that some higher and stronger correlations between TA and teaching styles we would obtain if the study group were only males.

However, there are other studies confirming that gender has a significant relationship with teacher autonomy, particularly in Iran which the concept of gender affects all dimensions of society, even teachers’ lives and their preferences in the teaching process; In most of the educational settings, men are preferred to women in professional conditions. Karimvand (Citation2011), for example, noted that given the dominance of either gender, usually male influences teachers’ teaching styles. In another study by Amini et al. (Citation2012), male faculty members chose the expert style while female faculty members focused on the expert and delegator styles.

However, as Aoki (Citation2002) stated, teacher autonomy is double-aged; it can lead to learner autonomy and development in one hand, and can be against the learner's success in another hand: Giving freedom and autonomy to the teacher may result in negative effects; the teacher could not take any responsibility for instructing the class, try to perform his own beliefs and ideas in the process of learning which must not be ethical somehow. Also, teacher autonomy can lead to learner autonomy and learner success, but constraints by managers and supervisors may bound the autonomy of the teacher conducting to the limited domain of teaching styles, too.

Consequently, as Aoki (Citation2002), and Breen and Mann (Citation1997) mentioned if academics be aware of how to be an autonomous teacher, they can select appropriate styles and appropriate behavior in teaching procedures. Of course, before this to happen for academic English teachers, granting autonomy and empowering them is an appropriate starting point, if the authorities of education systems are to take some steps toward building enhanced educational environments.

6. Conclusion

This study was conducted to clarify the link between teachers’ autonomy and their second language teaching styles and personality traits. So, through convenience sampling, a sample group was formed of 156 EFL Iranian teachers including both males and females with different university degrees from B.A. to Ph.D. The participants were to fill three questionnaires: (a) Teacher Autonomy Scale by Pearson and Moomaw (Citation2005), (b) Teaching Style Survey by Grasha (Citation1996) and (c) Costa and McCrae`s (Citation1992) NEO Personality Inventory.

At first, and also in response to the first research question, the relationship between the participants’ autonomy and their teaching styles was statistically analyzed by calculating the mean scores of the group’s autonomy and each of the Grasha’s five sub-constructs of teaching styles. In this case, the results show that there is a fairly strong correlation (0.63) between TA and the facilitator sub-construct. Other correlations are as follows: TA and the delegator (0.55), TA and the expert (0.46), TA and the personal model (0.54); however, there was seen no significant relationship between TA and the formal authority sub-construct (−0.09).

Second, to respond the second question, the relationship between our participants’ autonomy and their personality traits was also analyzed statistically by calculating the mean scores of the group’s autonomy and each of the personality sub-constructs of the Costa and McCrae`s (Citation1992) NEO Personality Inventory. The analysis shows that four personality sub-constructs can be positive significant predictors of autonomy. The correlations are as follows: TA and extroversion (0.65), TA and openness to experience (0.41), TA and agreeableness (0.42), TA and conscientiousness (0.47). What is left is the relationship between TA and neuroticism with a very weak negative correlation (−0.21). Meanwhile, correlations were also calculated between the different personality sub-constructs in one side and between the different sub-constructs of teaching styles in the other side, illustrated in .

Third, dividing the sample group into two parts of males and females, we separately calculated their autonomy level. Interestingly, the autonomy mean score of the males (63.44) was higher than that of the females (51.88). This difference in the mean scores can be very significant, which has led to an almost 7-point decrease in the autonomy level of the whole sample group. This can be why some of the past studies have not reached to any significant relationships between TA and teaching styles.

7. Implications and limitations

This study can have impacts in a variety of ways on language teachers, language learners, material developers, teacher educators, language policy manufacturers, and test developers as outcomes of the study are very useful in these fields.

First, this survey can facilitate EFL teachers to become acquainted with more autonomous teaching styles. Second, learners’ learning styles being in line with teachers’ autonomy and teaching styles build a meeting between learning and teaching styles or learners’ and teachers’ autonomy. Third, curriculum planners will use empirical information of teaching styles bestowed here to facilitate curricular policies and programs, the ones which do not put constraints on teachers’ autonomy. Fourth, educators will adapt the results of this analysis to use in their educational courses, educational curriculum, and course examinations, and to also reinforce autonomy in their trainees. Fifth, policy-makers will coordinate with academics in choosing educational policies, mainly in screening more qualified, creative, and autonomous teachers. Sixth, test developers become more convenient in choosing the test sorts and assessment sorts in accordance with teaching styles and can cooperate with teachers to prepare their own questions.

However, considering the limitations of this survey, there were various areas that need much more research. For conducting this research, only Iranian EFL teachers were selected through online networks which limited the number of participants and hence, might not be generalized to other non-Iranian teachers. Also, the three factors were focused as teaching styles, teachers’ personality traits, and teachers’ gender, while there were more criteria, such as the level of teaching experience, age, or teachers’ education which could be taken into account in relation to teachers’ autonomy. In Addition, including interviews and observance of teachers’ personality and their demographic characteristics in the classroom would result in more practical and creative domains of study. At last, studying learning styles and strategies in parallel with teaching styles may be valuable for future researches.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amir Marzban

Elaheh Fadaee is a Ph.D. candidate in English Language Teaching at Qaemshahr Islamic Azad University, Iran. Her research interests include second language teaching, teacher education, and translation.

References

- Adamson, J., & Sert, N. (2012). Autonomy in learning English as a foreign language. IJGE: International Journal of Global Education, 1(2). http:// www.ijtase.net/ojs/index.php/ijge/article/viewFile/69/83

- Akbari, R. (2007). Reflection on reflection: A critical appraisal of reflective practices in L2 teacher education. System, 35(2), 192–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2006.12.008

- Akbari, R., Kiany, G. R., Imani Naeeni, M., & Karimi Allvar, N. (2008). Teachers’ teaching styles, sense of efficacy, and reflectivity as correlates of students’ achievement outcomes. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 11(1), 1-28. https://ijal.khu.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-3-5&sid=1&slc_lang=en

- Akbari, R., Mirhassani, A., & Bahri, H. (2005). The relationship between teaching style and personality type of Iranian EFL teachers. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8(1), 1–22. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=58398

- Alibakhshi, G. (2011). On the impacts of gender and personality types on Iranian EFL teachers’ teaching efficacy and teaching activities preferences. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 14(1), 1–22. https://ijal.khu.ac.ir/article-1-29-en.html

- Amini, M., Samani, S., & Lotfi, F. (2012). Reviewing Grasha teaching methods among faculty members of Shiraz Medical School. Research and Development in Medical Education, 1(2), 37–43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n7p68

- Aoki, N. (2002). Aspects of teacher autonomy: Capacity, freedom, and responsibility. In P. Benson & S. Toogood (Eds.), Learner autonomy: Challenges to research and practice (pp. 110–124). Authentik.

- Arkott, A. (1968). Adjustment and mental health. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Baradaran, A. (2016). The relationship between teaching styles and autonomy among Iranian female EFL teachers, teaching at advanced levels. English Language Teaching, 9(3), 223–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v9n3p223

- Baradaran, A., & Hosseinzadeh, E. (2015). Investigating the relationship between Iranian EFL teachers’ teaching styles and their autonomy. International Journal of Language Learning and Applied Linguistics World, 9(1), 34–48. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n7p68

- Behnam, B. & Bayazidi, M. (2013). The relationship between personality types and teaching styles in Iranian adult TEFL contexts. Global Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 2(2013), 21-32. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258344172_The_relationship_between_personality_types_and_teaching_styles_in_Iranian_adult_TEFL_context/link/0c960527fd7f4e7ce6000000/download

- Belcher, D. D. (2006). English for specific purposes: Teaching to perceived needs and imagined futures in worlds of work, study, and everyday life. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 133–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/40264514

- Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching: Autonomy in language learning. England: Routledge

- Breen, M. P., & Mann, S. (1997). Shooting arrows at the sun: Perspectives on a pedagogy for autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 132–149). Longman.

- Brew, R. (2002). Kolb’s learning style instrument: Sensitive to gender. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 62(2), 373–390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164402062002011

- Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching (4 ed.). Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.

- Castle, K. (2004). The meaning of autonomy in early childhood teacher education. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 25(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1090102040250103

- Cooper., C., Th. (2001). Foreign language teaching and personality. Foreign Language Annals, 34(4), 301–317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2001.tb02062.x.

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Dictionaries, O. (2015). Autonomy. http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/autonomy

- Esfandyari, M. (2017). Iranian teachers’ perceived sense of autonomy and pedagogical style in EAP and EFL contexts (Master`s thesis). Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran. https://ganj.irandoc.ac.ir/viewer/f1f3a401aa8fc0304335de3dc8b7182d?sample=1

- Galluzzo, G. R. (2005). Performance assessment and renewing teacher education. The Clearing House, 78(4), 142–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.78.4.142-145

- Ghanizadeh, A., Jahedizadeh, S., & Boylan, M. (2016). EFL teachers’ teaching style, creativity, and burnout: A path analysis approach. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1151997

- Grasha, A. F. (1996). Teaching with style: A practical guide to enhance learning by understanding learning and teaching style. Pittsburgh: Alliance Publishers.

- Grasha, A. F. (2002). The dynamics of one-on-one teaching. College Teaching, 50(4), 139–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/87567550209595895

- Hanson, E. M. (1991). Educational administration and organizational behavior (3 ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

- Hughes, M. (Ed.). (1975). Administering education: International challenge. Athlone.

- Ingersoll, R. M. (2007). Short on power long on responsibility. Educational Leadership, 65(1), 20–25. https://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/129/

- Javadi, F. (2014). On the relationship between teacher autonomy and feeling of burnout among Iranian EFL teachers. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 98, 770–774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.480

- Karimi Moonaghi, H., Dabbaghi, F., Oskouie, F., Katri, V., & Binaghi, T. (2010). Teaching style in clinical nursing education: A qualitative study of Iranian nursing teachers’ experiences. Nurse Education in Practice, 10(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2009.01.016

- Karimvand, P. N. (2011). The nexus between Iranian EFL teachers’ self-efficacy, teaching experience and gender. English Language Teaching, 4(3), 171–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n3p171

- Kassaian, Z., & Ayatollahi, M. A. (2010). Teaching styles and optimal guidance in English language major. Quarterly Journal of Research and Planning in Higher Education, 16(1), 131–152. http://journal.irphe.ac.ir/article-1-764-en.html

- Khodadady, E. (2010). Factors underlying characteristics of effective English language teachers: Validity and sample effect. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 13(2), 47–73. http://ijal.khu.ac.ir/article-1–38-en.html

- Kumaravadivelu, B. (2001). Toward a post-method pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly, 35(4), 537–559. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3588427

- Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). TESOL methods: Changing tracks, challenging trends. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 59–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/40264511

- Lamb, T., & Simpson, M. (2003). Escaping from the treadmill: Practitioner research and professional autonomy. The Language Learning Journal, 28(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09571730385200211

- Larenas, C. H. D., Moran, A. V. R., & Rivera, K. J. P. (2010). Comparing teaching styles and personality types of EFL instructors in the public and private sectors. SciELO Colombia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262444997_Comparing_Teaching_Styles_and_Personality_Types_of_EFL_Instructors_in_the_Public_and_Private_Sectors

- Larsen-Freeman, D. (2000). Techniques and principles in language teaching (2 ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Lepine, S. A. (2007). The ruler and the ruled: Complicating a theory of teaching autonomy. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. University of Texas libraries. (UMI NO. 3291145). http://hdl.handle.net/2152/3738

- Little, D. (1995). Learning as dialogue: The dependence of learner autonomy on teacher autonomy. System, 23(2), 175–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0346-251X9500006-6

- Lucas, S. B. (2005). Who am I? The influence of teacher beliefs on the incorporation of instructional technology by higher education faculty (Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Alabama). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI NO. 3193807).

- Mahmoodi, T. (2017). The relationship between Iranian EFL teachers’ personality (Master`s thesis). Marvdasht Islamic Azad University, Fars, Iran. https://ganj.irandoc.ac.ir/viewer/d5d060c89d55c65f6d0c87db5a190da9?sample=1

- Matthews, G., Zeidner, M., & Roberts, R. D. (2006). Models of personality and affect for education: A review and synthesis. In P. A. Alexander & P. H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 163–186). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Mayer, J. D. (2007). Personality: A systems approach. Allyn & Bacon.

- McCollin, E. (2000). Faculty and student perceptions of teaching styles: Do teaching styles differ for traditional and nontraditional students? Retrieved from ERIC Document Reproduction Service. The College of the Bahamas. (ED 447139)

- McGrath, I. (2000). Teacher autonomy. In B. Sinclair, I. McGrath, & T. Lamb (Eds.), Learner autonomy, teacher autonomy (pp. Longman). London.

- McIlveen, P., Beccaria, G., & Burton, L. J. (2013). Beyond conscientiousness: Career optimism and satisfaction with academic major. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 229–236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.05.005

- Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (10 ed.). (2002). MerriamWebster.

- Mollaei, F., & Riasati, M. J. (2013). Autonomous learning and teaching in foreign language education. Journal of Studies in Learning and Teaching English, 1(3), 105–120. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=385336

- Moomaw, W. E. (2005). Teacher-perceived autonomy: A construct validation of the teacher autonomy scale (Doctoral dissertation). The University of West Florida. http://etd.fcla.edu/WF/WFE0000027/Moomaw_William_Edward_200512_EdD.pdf

- Myers, I. B., & McCaulley, M. H. (1985). Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Ololube, N. P. (2006). Teachers job satisfaction and motivation for school effectiveness: An assessment. University of Helsinki: Organizational Culture and Climate, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229824348_Teachers_Job_Satisfaction_and_Motivation_for_School_Effectiveness_An_Assessment/link/57b491d308aede8a665a55b3/download

- Paiva, V. & Braga, J. (2008). The complex nature of autonomy. DELTA. 24(2008), 441–468. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-44502008000300004

- Pearson, L. C., & Moomaw, W. (2005). The relationship between teacher autonomy and stress, work satisfaction, empowerment, and professionalism. Educational Research Quarterly, 29(1), 38–54. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ718115

- Pearson, L. C., & Moomaw, W. (2006). Continuing validation of the teaching autonomy scale. The Journal of Educational Research, 100(1), 44–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.100.1.44-51

- Peck, R. F., & Havighurst, R. J. (1960). The psychology of character development. John Whiley and Sons.

- Qashang, M. (2015). Relationship between Iranian EFL teachers’ job satisfaction level and their autonomy (Master`s thesis). Tabaran University, Mashhad, Iran. https://ganj.irandoc.ac.ir/viewer/883a9698ce10901e229e266e00555cf3?sample=1

- Rahimi, M., & Nabilou, Z. (2011). Iranian EFL teachers’ effectiveness of instructional behavior in public and private high schools. Asia Pacific Education Review, 12(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-010-9111-3

- Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., & Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing students’ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motivation and Emotion, 28(2), 147–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MOEM.0000032312.95499.6f

- Reeve, J., Jang., H., & Jang,, H. S. H. (2017). Personality-based antecedents of teachers’ autonomy-supportive and controlling motivating styles. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322537514_Personality-based_antecedents_of_teachers%27_autonomy-supportive_and_controlling_motivating_styles

- Reinders, H., & Balcikanli, C. (2011). Learning to foster autonomy: The role of teacher education materials. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.37237/020103

- Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2014). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

- Rushton, S., Morgan, J., & Richard, M. (2007). Teacher’s Myers Briggs personality profiles: Identifying effective teacher personality traits. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(3), 432–441. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.12.011

- Saha, L. J., & Dworkin, A. G. (2009). Teachers and teaching in an era of heightened school accountability: A forward look. Springer.

- Saljoughi, S., & Nemati, A. (2015). The relationship between teacher autonomy and learner autonomy among EFL students in Bandar Abbas. International Journal of Language Learning and Applied Linguistics World, 9(2), 178–185. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/317095925_Saljoughi_Sahar_Nemati_Azadeh_2015_The_relationship_between_teacher_autonomy_and_learner_autonomy_among_EFL_students_in_Bandar_Abbas_International_Journal_of_Language_learning_and_Applied_Linguistics

- Sayles, L. R., & Strauss, G. (1966). Human behavior in organizations. Prentice-Hall.

- Singer, J. (2006). The influence of repeated teaching and reflection on pre-service teachers’ views of inquiry and nature of science. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 20(6), 553–582. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-009-9144-9

- Skinner, R. R. (2008). Autonomy. Does the public charter school bargain make a difference?. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No.

- Smith, K. (2005). New methods and perspectives on teacher evaluation. In D. Beijaard, P. C. Meijer, G. Morine-Dershimer, & H. Tillema (Eds.), Teacher professional development in changing conditions (pp. 95–114). Springer.

- Sugarman, S. (1990). Piaget’s construction of the child’s reality. Cambridge University Press.

- Thompson, T. C. (1997). Learning styles and teaching styles: Who should adapt to whom? Business Communication Quarterly, 60(2), 125127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/108056999706000212

- Usop, A. M., Askandar, D. K., Langguyuan-Kadtong, M., & Usop, D. A. S. O. (2013). Work performance and job satisfaction among teachers. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3(5), 245–252. www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_3_No_5_March_2013/25.pdf

- Vaughn, L., & Baker, R. (2001). Teaching in the medical setting: Balancing teaching styles, learning styles and teaching methods. Medical Teacher, 23(6), 610–612. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590120091000

- Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press

- Webb, P. T. (2002). Teacher power: The exercise of professional autonomy in an era of strict accountability. Teacher Development, 6(1), 47–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530200200156

- Wilkesmann, U., & Lauer, S. (2015). What affects the teaching style of German professors? Evidence from two nationwide surveys. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 18(4), 713–736. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-015-0628-4

- Willner, R. G. (1990). Images of the future now: Autonomy, professionalism, and efficacy (Doctoral dissertation, Fordham University). Dissertation abstracts International, 52(3A), 0776. https://research.library.fordham.edu/dissertations/AAI9123118

- Wise, K. C. (1996). Strategies for teaching science: What works? The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 69(6), 337–338. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.1996.10114334

- Yan, H. (2010). A brief analysis of teacher autonomy in second language acquisition. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 1(2), 175–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.1.2.175-176

- Zhang, L. (2007). Do personality traits make a difference in teaching styles among Chinese high school teachers?. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0191886907000384