Abstract

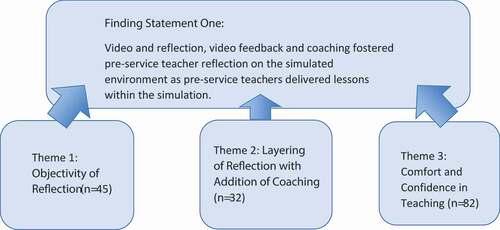

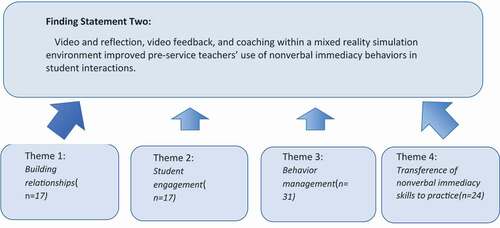

The purpose of this mixed method embedded design study was to examine the effect of a treatment package consisting of video and reflection, video feedback, and coaching on pre-service teachers’ use of nonverbal immediacy behaviors as they delivered lessons to student avatars in mixed reality simulations. Pre-service teachers delivered lessons at three points of time over the course of a semester within a teacher preparation course. Following each simulation, participants received three components of a treatment package targeted at improving nonverbal immediacy behaviors of teachers. The quantitative data were collected via nonverbal immediacy scores. Qualitative data were collected via observations of simulations and participant exit interviews. Statistical analysis resulted in a significant difference in pre-service teachers’ nonverbal immediacy when Time 2 and Time 3 were compared. An analysis of qualitative data resulted in two findings. Finding one was: Video and reflection, video feedback, and coaching fostered pre-service teachers’ reflections on the simulated environment as they delivered lessons within the simulations. Finding two was: Video and reflection, video feedback and coaching within a mixed reality simulation environment improved pre-service teachers’ use of nonverbal immediacy behaviors in student interactions. Connections to literature and implications are provided.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Mixed reality simulations are an emerging technology that allow for pre-service teachers to interact with student avatars to practice skills and rehearse teaching strategies in a safe environment without impacting real students. This study examined how the use of video and reflection, video feedback, and coaching within mixed reality simulation environments were utilized within a teacher preparation program to develop teacher nonverbal immediacy skills that aligned with high leverage practices.

The art of teaching is communication-rich, employing verbal, nonverbal and written modalities. Teachers and students, consciously and subconsciously, send and receive messages that can convey cognitive and affective information as they interact in the classroom (Miller, Citation2000). Research in communication indicates that the majority of what we communicate is done through nonverbal behaviors (Burgoon et al., Citation1996). Teachers must be able to effectively communicate with students to promote positive learning outcomes (Hunt et al., Citation2002), including communicating in non-verbal ways.

Nonverbal immediacy skills include nonverbal communication behaviors such as smiling, use of proximity, gesturing, and having a relaxed posture that indicate openness for communication. Teachers’ use of nonverbal immediacy behaviors have positive effects on students (Burroughs, Citation2007; Christophel, Citation1990; V.P. Richmond et al., Citation2003; Witt et al., Citation2004). Students of teachers who are perceived as more immediate exhibit more compliant classroom behaviors (Burroughs, Citation2007; Kearney et al., Citation1988), be more motivated to attend class, and experience positive learning outcomes (LeFebvre & Allen, Citation2014; Witt et al., Citation2004). Pre-service teachers may be able to practice and refine nonverbal immediacy skills within technology rich environments, such as mixed reality simulations.

Mixed reality simulation environments are an emerging technology that allow for pre-service teachers to interact with student avatars to practice skills and rehearse teaching strategies in a safe environment without impacting real students (Dieker et al., Citation2017; L Dieker et al., Citation2008; Dieker et al., Citation2013). Mixed reality environments lie in the middle of a continuum between actual reality and virtual reality (Milgram & Kishino, Citation1994). A mixed reality simulation environment combines elements of reality and virtual reality. Teacher candidates interact in a classroom with virtual student-avatars as they deliver lessons (Dieker et al., Citation2013; O’Callaghan & Piro, Citation2016). Simulated learning environments allow for pre-service teachers to practice communication and pedagogical skills with student avatars before honing their competencies with live students (Dieker et al., Citation2017, Citation2013; Pankowski & Walker, Citation2016).

There is an emerging body of research within the field of education on the use of virtual learning environments in teacher preparation programs (Dieker et al., Citation2013; Judge et al., Citation2013); however, few studies have examined the impact of using mixed reality simulations to promote communication competencies (Taylor et al., Citation2017; Walker et al., Citation2016). This study examined how the use of video and reflection, video feedback, and coaching within mixed reality simulation environments were utilized within a teacher preparation program to develop teacher nonverbal immediacy skills that aligned with high leverage practices.

1. Literature review

1.1. Immediacy

The immediacy construct, often proposed to be grounded in approach-avoidance theory (Mehrabian, Citation1971; Witt et al., Citation2010, Citation2004), evolved from the work of Albert Mehrabian (Citation1971, Citation1972)) who described his “principle of immediacy” and stated that, “people are drawn toward persons and things they like, evaluate highly, and prefer; and they avoid or move away from things they dislike, evaluate negatively, or do not prefer” (Mehrabian, Citation1971, p. 1). Immediate communication behaviors decrease the perceived physical or psychological distance between people and include verbal and nonverbal behaviors that convey warmth, positive affect, approachability, and availability for communication (Andersen, Citation1978, Citation1979; Mehrabian, Citation1971; V. P. Richmond et al., Citation2008; Velez & Cano, Citation2008). Nonimmediate behaviors can signal unfriendliness, disinterest, and even hostility (V. P. Richmond et al., Citation2008). Immediate behaviors relate to an approach tendency while nonimmediate behaviors relate to an avoidance tendency (Mehrabian, Citation1971; V. P. Richmond et al., Citation2008). V. P. Richmond et al. (Citation2008) suggest a communication immediacy principle from the communicator’s point of view in that, “the more communicators employ immediate behaviors, the more others will like, evaluate highly, and prefer such communicators; and the less communicators employ immediate behaviors, the more others will dislike, evaluate negatively, and reject such communicators” (p. 191). Mehrabian (Citation1971) also addressed the reciprocal nature of immediacy stating that, “immediacy and liking are two sides of the same coin. That is, liking encourages greater immediacy and immediacy produces more liking” (p. 77). Thus, in human communication interactions, the sender’s use of immediate behaviors influences perceptions by the receiver in the communication dyad.

Within educational contexts, verbal immediate behaviors include addressing students by name, using inclusive pronouns (e.g., “we” versus “I”), including personal examples, praising students, and using humor in class (Gorham, Citation1988). Nonverbal immediacy behaviors include smiling, eye contact, use of gestures, and having a relaxed body position (Andersen & Andersen, Citation2005; McCroskey & Richmond, Citation1992; V. P. Richmond et al., Citation2008; Woolfolk & Brooks, Citation1985) that can decrease the physical and perceived psychological distance between teachers and students to promote positive student outcomes (Gorham, Citation1988; Mehrabian, Citation1971; Nayernia et al., Citation2020).

Teacher’s use of nonverbal immediacy behaviors has been shown to affect students’ levels of motivation, compliance, affective learning, and academic achievement (Burroughs, Citation2007; Christophel, Citation1990; Kyaruzi et al., Citation2019; Witt et al., Citation2004).To understand the construct of immediacy in the educational context, and its impact on positive educational outcomes, a focused review of empirical research was conducted. Explorations included the effect on student learning, motivation, and behavior management for successful student academic outcomes. Most of the literature on the impact of teachers’ nonverbal immediacy on student educational outcomes are studies that were conducted within higher education settings and are included in the review.

1.2. Immediacy and teacher effectiveness

The construct of immediacy was first applied to the educational context by Andersen (Citation1978, Citation1979)) in her seminal work which examined the construct of teacher immediacy and its impact on teacher effectiveness (Özmen, Citation2010) and spurred subsequent investigations of teacher immediacy and its relationship with student learning (Witt et al., Citation2004). Teacher effectiveness was conceptualized as the ability of teachers to produce cognitive, affective, and behavioral student learning.

Teacher nonverbal immediacy was examined as a possible predictor of cognitive, affective, and behavioral learning (Andersen, Citation1979). Data were collected from 238 college students enrolled in an introductory communications course (n = 238) taught by 13 different professors (n = 13) simultaneously. Four aspects of affect were examined in the study. Student affect toward the communication practices suggested in the course, the content of the course, the course instructor, and the course in general, was measured using previously validated scale instruments. Two aspects of students’ behavioral commitment, the likelihood of attempting to engage in practices suggested in the course and the likelihood of enrolling in another course of similar content, were measured using four semantic differential scales (Andersen, Citation1979). Student performance on a 50-item multiple choice exam served as the measure of cognitive learning for this investigation. The construct of immediacy was measured using two instruments, the Behavioral Indicants of Immediacy Scale (BII) and the Generalized Immediacy Scale (GI). The BII, a 15-item, Likert-type scale instrument, examined specific nonverbal behaviors related to the immediacy construct (e.g., instructor use of gesturing, smiling, eye contact, and vocal expressiveness) while the GI scale, a 9-item scale instrument, measured the students’ general perception of the level of immediacy of their instructor (Andersen, Citation1979).

Multiple regression statistical analysis was employed to determine the predictive role of teacher nonverbal immediacy in affective, behavioral, and cognitive learning. Andersen (Citation1979) found that immediacy contributed 21.93% of the variance in student affect toward communication practices suggested in the course (F(2/235) = 33.01, 19.19% of the variance in student affect toward the content of the course (F(2/235) = 27.90, 13.37% of the variance in student affect toward the course in general (F(2/202) = 15.59 and 46.32% of the variance of student affect toward the instructor (F(2/235) = 101.41). Andersen (Citation1979) found that with respect to behavioral commitment and students’ likelihood of engaging in the communication practices as suggested in the course, immediacy predicted 18% of the variance (F(2/235) = 25.80). Additionally, Andersen’s (Citation1979) results revealed that teacher immediacy also predicted 18.31% of the variance in students’ likelihood of enrolling in a course of similar content (F(2/235) = 26.34).

Teacher immediacy, however, did not significantly predict students’ measure of cognitive learning in the study. Andersen (Citation1979) noted that the single score on the exam may not have accurately measured cognitive learning. Additionally, she suggested the possibility that the timing of the measure, administered early in the semester, may not have allowed for the relationship to develop. Andersen (Citation1979) suggested that “teacher-student relationships may be improved by teaching teachers to be more immediate,” (p. 557) as the results indicated that nonverbal immediacy is a strong predictor of student affect toward the instructor.

1.3. Teacher immediacy and student learning

The introduction of a measure of cognitive learning, a perceived “learning loss” measure (Richmond, McCroskey, & Johnson, Citation2003), spurred several studies that were used to explore the relationship of nonverbal immediacy and perceived cognitive learning (Witt et al., Citation2004). The “learning loss” score was obtained by asking participants to rate their level of learning in a class on a zero through nine scale (Richmond, McCroskey, et al., 1987). Secondly, respondents followed the same procedure about their level of perceived learning had they had an ideal instructor. The first rating was subtracted from the second, which resulted in a “learning loss” score. This measure served to adjust the initial rating of cognitive learning to consider students’ preconceived attitudes toward certain classes (Richmond, McCroskey, et al., 1987).

In their meta-analysis of 81 studies (n = 24,474), Witt, Wheeless, and Allen (Citation2004) examined the relationship between immediacy and student cognitive, affective, and perceived learning. The scholars created a “perceived learning” category before conducting their investigation “… because of the large number of studies using the learning loss measure and the questions surrounding the validity of learning loss as a cognitive measure” (Witt et al., Citation2004, p. 198). Results of the meta-analysis revealed a strong, positive relationship was found between overall teacher immediacy and overall student learning, average r = .500, var. = .037, k = 81, n = 24,474 (Witt et al., Citation2004). Overall student learning included studies that examined cognitive learning and used traditional measures (i.e., tests), affective learning which included behavioral aspects, and perceived learning which used the self-reported measure. Similar results were obtained (average r = .481, var. = .040, k = 68, n = 21,171) when only the effect of nonverbal immediacy on overall student learning was examined (Witt et al., Citation2004).

When the relationship of nonverbal immediacy and each of the three categories of learning were examined individually, meta-analysis revealed studies that examined nonverbal immediacy and perceived learning (average r = .510, k = 44, n = 13,313) were similar to results from studies that examined the relationship of nonverbal immediacy and affective learning (average r = .490, k = 55, n = 17,328). Outcomes of studies that examined nonverbal immediacy and cognitive learning, (average r = .166, k = 11, n = 3,777), revealed the lowest associations. The authors noted that the studies included in their meta-analysis did not investigate cognitive learning over time, and that if affect provides motivation for cognitive learning over time, “then the statistically significant (albeit small) results provide credibility and have implications for future research” (Witt et al., Citation2004, p. 200). Longitudinal studies may offer more insight into the relationship of teacher immediacy on student learning.

1.4. Beginning teacher immediacy and student learning

The relationship between nonverbal immediacy of teaching assistants or beginning teachers, teaching in self-contained or lecture/laboratory settings, and students’ affective and cognitive learning, was recently studied at a mid-western public university (LeFebvre & Allen, Citation2014). In their investigation, 256 undergraduate students enrolled in one of 20 sections of an introductory public speaking course, taught by a total of 20 teaching assistants, were surveyed. The Nonverbal Immediacy Scale—Self Report (V.P. Richmond et al., Citation2003) was used to evaluate students’ perceptions of their instructors’ level of immediacy. Students’ perceptions of affective learning, which included their feelings about the course content and instructor, were collected utilizing the Affective Learning Measure (McCroskey, Citation1994). The students’ overall grade for the course served as the measure of cognitive learning.

No statistical difference (t(254), p = .88) on the level of immediacy was found between teaching assistants teaching in a self-contained setting (M = 97.55, SD = 10.50, n = 139) and teachers instructing in a setting which consisted of a combination of a lecture/laboratory (M = 97.74, SD = 9.99, n = 117). However, teacher immediacy impacted cognitive and affective learning of students in both settings. A significant, positive relationship between teachers’ nonverbal immediacy behaviors and students’ cognitive learning, as measured by the final grade for the course, was found (r = .21, p < .001, n = 256). Students that perceived their teachers to be more immediate received higher course grades. Additionally, immediacy correlated positively with students’ affective learning (r = .43, p = < .01, n = 256). Student learning was impacted by immediacy regardless of the class format. The researchers concluded that the findings in the investigation supports the training and development of beginning teachers’ nonverbal immediacy skills to promote positive educational outcomes for students (LeFebvre & Allen, Citation2014).

1.5. Relationship among teacher immediacy, student motivation, and student perceived learning

Christophel (Citation1990) sought to understand the relationship among teacher immediacy, student state motivation, and perceived cognitive learning. Students’ state motivation for learning is temporary in nature, and reflective of students’ attitudes toward a course at a period of time. Conversely, trait motivation is reflective of a students’ general level of motivation or attitudes toward learning that are consistent over time (Christophel, Citation1990).

Two separate studies comprised the total of this research. In the first study, 562 graduate and undergraduate students completed three survey instruments related to their perceived level of teacher immediacy, trait/state motivation or affective learning, and cognitive learning. In an effort to collect immediacy behavior data from a wide variety of teachers and classes, students were asked to rate the level of teacher immediacy and their perception of their level of trait/state motivation and cognitive learning from the class they were enrolled in that took place immediately prior to the class in which the surveys were administered. Teacher immediacy was measured via the Immediacy Behavior Scale which included items that reflected verbal immediacy (Gorham, Citation1988) and nonverbal immediacy (Richmond, Gorham, & McCroskey, 1987) behaviors. The Trait/State Motivation Scales (Christophel, Citation1990) measured perceived student motivation or attitudes for learning in general, and for the course immediately preceding the one in which they were enrolled. Perceived cognitive learning was measured using two items related to students’ perceived learning in the class and perceived learning had they had an ideal instructor. The resulting “learning loss” score (Richmond, McCroskey, et al., 1987), obtained by subtracting students’ rating in the first question from the second, generated the students’ overall cognitive learning scores. Affective learning, or positive attitudes about the instructor, the course in general and content, and likelihood of enrolling in a similar course or in a course taught by the same instructor, was also measured via an affective learning scale instrument (McCroskey et al., Citation1985). Six elements were measured and an overall affective learning score, as well as sub-scores, were computed.

In the second study, approximately half of the students in each class were asked to complete the immediacy and motivation scales and the other half of the students were asked to complete the motivation and learning scales based on the class in which they were currently enrolled. Correlational and regression analyses of data collected in the first study were conducted to determine the relationship among teacher immediacy, motivation, and learning. Results of correlational analyses found significant, positive relationships between overall teacher immediacy and student state motivation (r = .49, n = 562, p < .001), verbal immediacy and student state motivation (r = .47, n = 562, p < .001), and nonverbal immediacy and student state motivation (r = .34, n = 562, p < .001). Therefore, students who reported higher levels of immediate behaviors by their teachers also reported higher levels of student motivation. A positive, significant relationship between teacher immediacy and perceived cognitive learning (r = .45, n = 562, p < .001) was found; regression analysis indicated that nonverbal immediacy was more predictive of student learning than verbal immediacy. Partial correlation analysis revealed that much of the variance in learning scores predicted by nonverbal immediacy was due to the predictor variable, state motivation. According to Christophel (Citation1990), the data suggested that nonverbal immediacy initially modifies student state motivation before affecting student perceived learning, which aligns with the approach-avoidance aspect of motivation theory.

In the second study, scores obtained from Group A (n = 624) were comprised of student trait/state motivation and immediacy scales and represented half of the class. The remaining half, Group B (n = 624), reported scores for the motivation scales and learning instruments. Group C, or “Classes,” were the average of reported scores of participants in Group A and B. Correlations and regression analysis of data obtained in the second study revealed similar findings as the first study. Teacher immediacy was positively correlated with student motivation (r = .60, n = 60, p < .001), cognitive learning (r = .40, n = 60, p < .001), and total affective learning (r = .53, n = 60, p < .001). Further data analysis exploring the degree that teacher immediacy and student state motivation were collinear predictors of learning, revealed similar findings as in the first study. Therefore, findings suggest that in general, teacher nonverbal immediacy initially modifies student state motivation to affect student perceived learning (Christophel, Citation1990).

1.6. A causal model: immediacy, affective learning, and cognitive learning

A causal model which explored the relationship of teacher immediacy and students’ affective learning as an intermediary outcome leading to potential higher levels of cognitive learning was investigated through meta-analysis by Allen et al. (Citation2006). The researchers posited that teacher immediacy would function as a source of positive reinforcement for students, which would in turn motivate students to perform (Allen et al., Citation2006). Two-thirds of the required correlational data were obtained from another meta-analysis by the same researchers (Witt et al., Citation2004) and used to test the model. The relationship between immediacy and cognitive learning was estimated, r = .13, k = 16, n = 5,437. The relationship between immediacy and affective learning was estimated, r = .50, k = 81, n = 24,474. Eight studies were identified from the first study (Witt et al., Citation2004) that met the criteria to allow for estimation of an average correlation between cognitive and affective learning (Allen et al., Citation2006), and a positive correlation was found (r = .08, k = 8, n = 1,449). The model was tested, and results supported the notion that teacher immediacy behaviors predict student affective learning (Allen et al., Citation2006). Results suggested a direct relationship between teacher immediacy and affective learning and motivation and an indirect relationship with cognitive learning (mediated by student motivation). The scholars contended that teacher immediacy may have more of an impact on student learning than the data show, as the small effect revealed by the data reflected only a snapshot in time in an individual class. In their view, the cumulative effect of teacher immediacy should be considered (Allen et al., Citation2006).

1.7. Teacher immediacy and student behavior management

Teachers promote student learning by effectively establishing positive learning climates where students behave appropriately, are engaged in learning, and are motivated to complete coursework that leads to positive educational outcomes (Barr, Citation2016). Kearney et al. (Citation1988) investigated the interaction between teachers’ nonverbal immediacy behaviors and use of verbal prosocial and antisocial strategies to gain student compliance. Prosocial strategies were conceptualized as reward-based and meant to encourage students and convey concern for a student’s success. Conversely, antisocial strategies are punishment-based and foster competitiveness and erode students’ dignity (Kearney et al., Citation1988). The researchers hypothesized that teacher nonverbal immediacy and use of compliance-gaining verbal strategy would affect students’ resistance to comply with teacher requests. The researchers posited that “the use of verbal strategies that are asynchronous with teachers’ immediacy or nonimmediacy orientation may prompt more student resistance than the use of verbal strategies that are synchronous with teachers’ nonverbal immediacy” (Kearney et al., Citation1988, p. 58). Therefore, there would be less student resistance to immediate teachers employing prosocial strategies than antisocial strategies. However, nonimmediate teachers employing prosocial verbal strategies would be resisted more than instructors employing antisocial strategies, as the verbal and nonverbal messages are inconsistent, and may seem disingenuous (Kearney et al., Citation1988).

One of four scenarios or treatments were administered to undergraduate students enrolled in communication classes (n = 629). The scenarios described a teacher that exhibited one of four combinations of nonverbal immediacy and verbal strategies: nonverbally immediate, employing prosocial verbal strategies; immediate using antisocial strategies; nonimmediate utilizing prosocial strategies; and nonimmediate applying antisocial verbal compliance-gaining strategies.

Results of a two-way ANOVA were significant, F(1,15) = 9.21, p < .01, eta squared = 1%. Follow-up tests employing Tukey’s test for unconfounded means (critical value for mean differences = .712) revealed that student resistance to a teacher perceived as immediate and employing antisocial verbal strategies (M = 8.5) was significantly more than resistance to a teacher that was perceived as immediate employing prosocial verbal messages (M = 7.7). Student resistance was significantly more when the teacher was perceived as nonimmediate employing antisocial strategies (M = 13.36) than the immediate teacher using prosocial messages (M = 7.7). However, student resistance to the nonimmediate teacher employing prosocial verbal messages (M = 15.2) was resisted more than the nonimmediate teacher utilizing antisocial messages (M = 13.36). Therefore, the results suggest the important role of consistency when one considers the role of nonverbal behavior and verbal communication. Further statistical analysis that examined the main effects for immediacy (F(1,515) = 199.67, p < .001, eta squared = 27%) and strategy type (F(1,515) = 2.29, p > .05, eta squared = .004%) revealed a significant immediacy effect (F(1,515) = 21.678, p < .001), suggesting the important role of nonverbal immediacy behaviors and their effect on student behavior management (Kearney et al., Citation1988).

1.8. Video as a feedback tool

The use of video as a feedback tool for teacher self-reflection in teacher professional development is well-documented (Fukkink et al., Citation2011; Fuller & Manning, Citation1973; Tripp & Rich, Citation2012). In their analysis of 63 studies involving pre-service and in-service teachers where participants used video to examine and reflect on their own teaching performance, Tripp and Rich (Citation2012) provided evidence for the use of video to foster teachers’ abilities to self-reflect and to make instructional changes. The use of video grounds the process of reflection in one’s actual performance of teaching instead of relying on a memory of the performance (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018).

Microteaching, conceptualized in the early 1960s at Stanford University, involved the recording of teachers as they tried out an instructional strategy and the receipt of feedback and coaching by an expert for the purposes of teacher development (Knight, Citation2014). Today, instructional coaching is a collaborative process where the coach and teacher analyze, “… current reality, set goals, identify and explain teaching strategies to meet goals, and provide support until goals are met” (Knight, Citation2017, p. 2). The use of video analysis to ground the instructional coaching process is powerful, as often a truer picture of reality is illuminated. Video analysis allows for the focusing on specific behaviors or strategies while helping to alleviate habituation or confirmation bias (Knight, Citation2014). This grounding in reality is critical for the processes of goal setting and the monitoring of progress toward meeting goals.

In their seminal work on video playback in educationFuller and Manning (Citation1973) described the viewing of one’s performance on video as “self-confrontation,” and the identification of discrepancies between one’s perceived experience and observations from video playback as one’s ability to realistically assess one’s self. In focused observations, they asserted that behavioral changes could occur when an outside observer’s perceptions are compared with one’s own, the level of realism with respect to the experience is increased, and the outside observer possesses facilitating characteristics (Fuller & Manning, Citation1973). The researchers cautioned that the process causes one to intently focus on the self and may induce stress in some students (Fuller & Manning, Citation1973). However, Xiao and Tobin (Citation2018) asserted that today’s students, raised in an age where sharing images and video of themselves via social media is common, may not experience the same feelings of discomfort as the students referred to by Fuller and Manning over 40 (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018).

1.8.1. Video feedback, reflection, and pre-service teacher communication skills

Self-examination through the use of video technology can be an important part of a learning cycle which includes reflection, conceptualization and revision, and practice (Kolb, Citation1984). The impact of a video reflection system on the communication skills of undergraduate pre-service teachers was investigated in a mixed methods study in Australia (Bower et al., Citation2011). Participants included undergraduate pre-service teachers enrolled in a mathematics methods course (n = 10) or a language methods course (n = 14).

A video reflection system was used to facilitate pre-service teachers’ self-reflection as part of a learning cycle aimed at improving communication skills. Pre-service teachers presented, reviewed their presentations individually via video technology, reflected on their performances and wrote reflections via a blogging tool, received peer feedback and viewed peers’ presentations, and revised practices to improve communication skills in a subsequent presentation (Bower et al., Citation2011). Over the course of one semester, pre-service teachers completed this process twice. Following the completion of both presentations, pre-service teachers completed an online questionnaire consisting of 10 questions about their performances, the video reflection process and its features, and suggestions for improvements in the process.

Between both courses, a total of 50 video posts which included self-reflections and 106 posts consisting of peer feedback were completed. Results of a two-sample two-tailed t- test revealed that the average rating of the second presentation was significantly higher than the first presentation, t(21) = 2.55, p = .02. Pre-service teachers’ average self-ratings of the first presentation was 5.1 out of 10. For the second presentation, the average of self-ratings was 6.3 out of 10 (Bower et al., Citation2011).

An examination of pre-service teachers’ qualitative data revealed that the teachers believed that nervousness and behaviors that convey anxiety (e.g., rigid or stiff posture) were underlying factors that contributed to the low scores of the first presentations. With respect to contributing factors that improved their scoring of the second presentations, pre-service teachers indicated that they felt more confident to present and intentionally tried to increase nonverbal behaviors such as eye gaze, gesture, and using an effective tone of voice (Bower et al., Citation2011). Overall, 86.3% of the teachers indicated that they felt the video reflection system helped them learn and improve in their ability to communicate and appreciated the opportunity to see and hear themselves perform. The process, which included peer-review, allowed the students to anchor their self-reflections while comparing their performances to those of their peers.

An analysis of student comments also illustrated that the opportunity to view one’s self using communication strategies with students, the process of self-critique, and the receipt of feedback and support from peers contributed to their growth in learning about classroom communication and its effect on students. According to the researchers, “student reflections on the physical aspects of communication (such as eye contact, body movements, pace of delivery) shaped their understanding of how to effectively construct meaning for the onlookers (their pupils)” (Bower et al., Citation2011, p. 323). The researchers point out that following the first video reflection process, pre-service teachers gained confidence in their abilities, and communication anxiety was reduced for the second presentation. Video analysis of their performances allowed for a comprehensive analysis of communication skills and promoted understanding of the effect of these behaviors on the receivers of the communication. This study supports the use of video technology to promote self-reflection combined with feedback to nurture growth in communication skills of pre-service teachers.

1.8.2. Video feedback, reflection, and embodied aspects of teaching

The impact of video for self-reflection on the use of nonverbal or embodied aspects of teaching behaviors was explored in a study of 23 pre-service teachers enrolled in an early childhood education certification program (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018). Students’ videotaped lessons taught during a field experience and narrative reflections served as the main source of data. Acknowledging the use of video in teacher preparation focusing on verbal aspects of teaching, the researchers argued that video could be used as a tool to promote the embodied or nonverbal aspects of teaching, “… by drawing attention to aspects of teaching that are unplanned, tacit, and embodied such as pedagogical tact, the teacher’s use of materials, gaze, gesture, posture, positioning in the classroom, and withitness” (p. 329). Video can capture important nonverbal communication data.

At the midpoint and end of the semester in which participants were immersed in their first field experiences, pre-service teachers planned, taught, and videotaped themselves teaching a lesson and interacting with pre-kindergarten students (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018). The pre-service teachers were instructed to watch their videos with sound and without sound, and to reflect on the lesson while focusing on nonverbal communication behaviors such as gesturing, posture, eye gaze, and touch. Additionally, the pre-service teachers reflected on the experience of videotaping themselves and the process of watching and assessing the videos through written narratives (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018).

Following the first round of video data and narrative collection, the instructor presented information about embodied aspects of teaching such as use of gestures, voice, facial expressions, and touch. The class and instructor then reviewed the students’ videos, pointing out effective and ineffective pedagogical practices related to embodied aspects of the pre-service teachers as they taught their lessons (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018). These procedures were duplicated at the end of the semester, and students’ video submissions were coded for eight embodied aspects of teaching including use of gestures, posture, and touch as well as non-embodied aspects of teaching, such as use of wait time (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018). Students’ narrative reflections were coded and a content analysis procedure was completed that classified reflections into one of three categories—embodied aspects (e.g., eye gaze), non-embodied aspects of teaching (e.g., wait time) and other aspects of the video (e.g., comments about being videotaped). Video data analysis consisted of identifying and counting the categories of embodied teaching techniques used in lessons at the midterm and end of the semester, yielding frequency counts for each category. Once an identified embodied technique was used, it was counted once, even if used multiple times throughout the lesson. Frequency counts of body techniques that were mentioned in students’ narrative reflections were also obtained in addition to students’ reflections about the experience of being videotaped (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018).

When video data from the midterm were compared to the final, the number of categorized embodied teaching techniques increased 11%, with the most marked increases in the techniques of positioning and touch (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018). At midterm, 15 students utilized positioning in their lessons, while at the end of the semester, 21 students used positioning. Touch was used by seven students at midterm, while 11 students used touch as an embodied pedagogical practice during the final lesson. An analysis of students’ reflections revealed that students increased their comments on their use of bodily techniques by 13%, with body positioning mentioned by 13 students at midterm, while all 23 students commented on their body positioning on the final reflections. The second largest increases in students’ mentions of behaviors were in the categories of touch and eye gaze; five more students reflected on these behaviors when the midterm and final reflections were compared. The researchers assert that based on the increases in embodied techniques displayed in lessons on the videos and mentioned in pre-service teachers’ reflection papers in their study, there is some evidence that bodily techniques used in teaching can be, “… learned, practiced, and improved” (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018, p. 337).

Qualitative data analysis of students’ narrative reflections indicated that many students felt they were better able to focus on the embodied aspects of their teaching when they viewed the video with the sound off, allowing for a more focused review of the nonverbal facets of their teaching. Some students indicated they had a better understanding of the power of some embodied teaching techniques for presenting information, such as the use of gesturing, following reviewing their video and receiving peer feedback (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018). An analysis of the final reflections on the experience revealed that although some students found the experience initially awkward, they grew more comfortable with the process as the semester progressed. Data indicated that students began to assess themselves more positively, as the ratio of positive to negative comments about their embodied teaching behaviors grew from a ratio of 2:1 at midterm to a ratio of 3:1 at the end of the semester (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018). Taken as a whole, the study supports the use of video feedback and reflection as powerful tools in assisting pre-service teachers in developing their nonverbal teaching skills to communicate more effectively, manage classroom behaviors, and promote their students’ understanding of concepts (Xiao & Tobin, Citation2018).

2. Simulations

Sauvé et al. (Citation2007) define a simulation as, “a simplified, dynamic, and accurate model of reality that is a system used in a learning context” (p. 253). Unlike games, simulations are non-competitive, serve as a model of real-life scenarios, are often tied to educational objectives, and allow learners to study real phenomena that is often complex in nature (Kaufman & Ireland, Citation2016; Suavé et al., Citation2007). Simulations offer novices in fields such as medicine, business, and teaching the opportunity to practice and apply theoretical skills learned in coursework to realistic situations and environments (Bradley & Kendall, Citation2014; Dawson & Lignugaris Kraft, Citation2017; Dede, Citation2009; Dieker et al., Citation2017; Wang & Su, Citation2018). Simulations have been used for training purposes in complex and often risky fields such as aviation, the military, and medical fields for decades. In the field of education, however, the application of simulations is relatively new (Bradley & Kendall, Citation2014; Dieker et al., Citation2013; Kaufman & Ireland, Citation2016; Shaffer et al., Citation2001).

2.1. Simulations in education

In the educational context, simulations originated as written case studies, videos, or role-plays within teacher preparation classes for the purpose of learning targeted skills (Dieker et al., Citation2014). As technology evolved, simulations have evolved, and several types of simulations are available to be used for educational purposes. These simulations can be categorized as single user programs, Multi-User Virtual Environments, and mixed reality virtual puppetry simulations (Bradley & Kendall, Citation2014). Simulations that use virtual puppetry within a real learning laboratory allow the student to feel as though they are present within the virtual environment as they teach (Dede, Citation2009). Due to the scope and context of the present study, the discussion pertaining to mixed reality simulations is limited exclusively to the field of educational simulations and those using the fully immersive virtual puppetry environments via Mursion®.

2.2. Mixed reality simulations

A mixed reality simulation environment, like augmented reality, combines elements of reality and virtual reality. According to Milgram and Kishino (Citation1994), augmented reality and mixed reality environments lie in the middle of a continuum between actual reality and virtual reality. Effective simulations are realistic, personalized learning experiences where participants feel a sense of immersion and an impression of participation within the digital environment (Dede, Citation2009). Mixed reality simulations allow for repeated practice of targeted skills without harm to others (L Dieker et al., Citation2008; Dieker et al., 2014; Kaufman & Ireland, Citation2016). In the field of teacher preparation, mixed reality environments allow for virtual situated learning experiences (Brown et al., Citation1989) that enable teacher candidates to take on the role of a teacher and practice communication and pedagogical skills in an immersive environment (Dieker et al., Citation2013; Dieker et al., 2014).

A multidisciplinary group of educators and scientists at the University of Central Florida created the TeachLivE® mixed reality simulation environment, now commercialized as Mursion®, to help recruit and prepare pre-service math, science, and special education teachers for the demands of the complex teaching environment (L Dieker et al., Citation2008; Hudson et al., Citation2018). Mursion® provides simulation environments for the development of technical and interpersonal skills of personnel in fields such as business, health care, defense, and education (Mursion, Inc., Citation2019a).

Pre-service teachers, in this environment, begin to apply their understanding of diversity in utilizing their knowledge of teaching strategies with student avatars of differing personalities, abilities, and cultural backgrounds that are reflective of real classrooms (Dawson & Lignugaris/Kraft, 2017; Dieker et al., Citation2013). In this environment, the pre-service teacher can practice a teaching strategy, behavior management technique, or other targeted practice while having the opportunity to pause the simulation to correct any errors or to get feedback and restart the simulation (Dieker et al., Citation2013; Dieker et al., 2014). The controlled environment, unlike a real classroom, allows for pre-service teachers to engage in multiple rehearsals of a practice without affecting live students or taking up valuable classroom instructional time (Dieker et al., Citation2013; Dieker et al., 2014).

2.2.1. Mixed reality simulations and coaching for teacher training

Garland et al. (Citation2012) examined the effect of coaching within mixed reality simulations on special education teachers’ development of an evidence-based teaching strategy that is recommended for students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The use of the simulation environment, TeachLivE™, was used to train four special education teachers in the learning and implementation of a teaching technique known as Discrete Trial Teaching (DTT). The technique, rooted in applied behavior analysis, breaks down objectives into smaller components and utilizes positive reinforcement when objectives are met (Garland et al., Citation2012). A student avatar exhibiting behaviors consistent with students with ASD was used throughout the course of the study to train special education teachers in the practice of DTT. A multiple baseline research design across four female participants examined the effect of coaching within the mixed reality simulation on the participants’ implementation of the DTT teaching strategy, as measured by an evaluation rubric aligned to the DTT technique (Garland et al., Citation2012).

Data were collected from four baseline sessions, in which teachers were given instruction in the DTT teaching strategy and practiced implementing the technique with Austin, a student avatar in the simulation environment. The treatment consisted of a review of participants’ previous simulation session, feedback, and coaching in the components of the DTT teaching strategy. Following the training session, participants then interacted with the avatar and performed ten discrete trials which were scored using a rubric.

Results showed consistent and positive gains in scores from baseline to treatment phases of the study. Overall, the average gain in scores was 49.9% over three participants that participated in all treatment sessions; while an increase of 41% was obtained for a participant who completed only one treatment session (Garland et al., Citation2012).

Interview data revealed that teacher participants appreciated the opportunity to practice learning about and implementing the teaching strategy with the student avatar that could be manipulated so a focus on the technique could be achieved, and the student avatar could not be harmed like a real student (Garland et al., Citation2012). The small number of participants is a limitation to this study; however, the results show that positive results in the learning and implementation of a specialized technique, DTT, were realized when the mixed reality environment and follow-up coaching was used for special education teacher professional development.

2.2.2. Data-driven feedback and coaching within mixed reality simulations for teacher training

DeSantis (Citation2018) examined the impact of data-driven feedback and coaching on pre-service teachers’ sense of self-efficacy and on the development of higher order questioning strategies to elicit student thinking. In the mixed method study, a quasi-experimental treatment and control group design was employed where the treatment group (n = 15) experienced data-driven feedback and coaching related to the participants’ use of higher order questioning techniques as they delivered lessons to student avatars in a mixed reality simulation environment. Participants in the comparison group (n = 15) did not receive the feedback and coaching but did experience the mixed reality simulation environment.

When the number and type of higher order thinking questions (HOTs) generated between the groups were analyzed via a Chi-Square analysis, a statistically significant difference (χ2 = (1) = 47.56, p < .01) between basic knowledge and comprehension questioning (K/C) and HOT questioning performance between the treatment and comparison groups resulted. Follow-up analysis of the participants’ creation of HOT questions via a Sign test procedure revealed statistically significant results for all pairwise comparisons of scores among the treatment group; p values ranged from .002 to .005. However, no statistically significant differences in scores were found for any of the pairwise comparisons among scores of the comparison group. An examination of pre-post self-efficacy scores, as measured by the Teacher’s Sense of Self-efficacy Scale (TSES), did not reveal a statistically significant result when the treatment and comparison groups’ scores were analyzed. Therefore, results from the TSES appear to indicate that while the treatment did not affect pre-service teachers’ sense of self-efficacy, an impact on the skill of generating higher order thinking questions was realized. The researcher noted that the participants typically experienced six mixed reality simulations as part of their program prior to the study, and the TSES focuses on perceptions of self-efficacy with respect to teaching overall, not on just the skill of higher order questioning practices. Qualitative analysis of interview and coaching data revealed that pre-service teacher–student participants in the treatment group appreciated the data-driven feedback and coaching treatment and recognized their overall growth in their ability in utilizing higher order questioning techniques, lesson planning, and lesson delivery. Comparison group participants expressed they did not experience growth in the skill of higher order questioning, and some members expressed confusion as to the basics of the strategy. Results of the study indicated that data-driven feedback and coaching within mixed reality simulations can help foster the development of higher order questioning techniques among pre-service teachers.

2.2.3. Mixed reality simulations and instructional skills

An exploration of the effect of virtual professional development on teachers’ application of pedagogical knowledge and improvement in student outcomes in mathematics was conducted in a large-scale national research study (Dieker et al., Citation2017). Participants were in-service middle school mathematics teachers (n = 135), teaching in 10 schools across six states. A quasi-experimental four-group randomized trial research design measured teachers pre-post in their classrooms and, as the case with two of the groups, four times in the mixed reality simulation environment (Dieker et al., Citation2017).

Each participant in all four groups was provided a lesson plan aligned to Common Core Standards in Mathematics, while different types of professional development were implemented with three of the four groups. Group 1 received the lesson plans only and served as the comparison group (Dieker et al., Citation2017). Group 2 received professional development in the form of one 40-minute online session that focused on formative assessment strategies and included the teachers’ analysis of student work samples and follow-up discussion of teacher questioning and feedback strategies (Dieker et al., Citation2017). Teachers in Group 3 received four 10-minute sessions in the TeachLivE™ simulator (now known as Mursion®) over the course of four to six weeks. Participants in this group reviewed the same student work samples as those used in Group 2 and taught a whole class discussion to the five student avatars under the premise the work samples were from these virtual students (Dieker et al., Citation2017). Following the simulation session, participants took part in a review process that included their individual reflections on their performance with respect to the use of higher-order questioning and feedback strategies, and the receipt of feedback in the form of data on their frequencies of those strategies during the session. Upon completion of this review process, participants completed another 10-minute simulation session and, approximately one month later, experienced two additional 10-minute simulations that included the review process after leading a discussion with the student avatars (Dieker et al., Citation2017). Participants in Group 4 received the 40-minute online professional development experienced by participants in Group 2 as well as four, 10-minute simulation sessions. However, participants in this group did not participate in the review process (Dieker et al., Citation2017).

Qualitative and quantitative data were collected pre-post treatment utilizing the Teacher Practice Observation Tool (TPOT) to measure teachers’ practices in their actual classrooms (Dieker et al., Citation2017). Frequency data with respect to teachers’ use of high leverage practices, specifically higher-order questioning techniques, type of feedback, and amount of wait time, were collected during classroom observations (Dieker et al., Citation2017). Frequency data on the specific high leverage practice targeted in a simulation session were also collected for participants experiencing the sessions as part of the treatment condition. Additionally, teacher data were collected on eight modified sub-constructs from the 2011 Danielson Framework for Teaching Evaluation Instrument and qualitative field notes. Student data, specifically 10 items from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) assessment were collected pre-post intervention.

For data analysis purposes, teaching practices were measured pre-post intervention along three dimensions: describe/explain questions (DE), specific feedback (SF), and score on the TPOT instrument (Dieker et al., Citation2017). A two-factor mixed design ANOVA was employed to analyze whether differential effects on teacher performance occurred over four 10-minute simulations, depending on whether participants received online PD. Time served as the within-subjects factor while condition (online PD or no online PD) served as the between-subjects factor; SF and DE were the dependent variables. Results indicated no differential effects with respect to DE questions (F(3,171) = .735, p = .532, ηp2 = .13) nor SF given to student avatars (F(3,168) = 1.989, p = .118, ηp2 = .034) based on whether teachers experienced online PD. However, there was a significant large effect for time when DE questions were analyzed (F(3,171) = 9.993, p = .000, ηp2 = .149) and a significant effect for time when SF was analyzed (F(3,168) = 2.306, p = .079, ηp2 = .040). Teacher performance scores, with respect to those high leverage practices, significantly increased over the four sessions of the simulations regardless of whether they received the online PD.

The researchers investigated whether differential effects of development of targeted skills in the simulation environment transferred to teachers’ practices in their actual classrooms (Dieker et al., Citation2017). Results of a three-way mixed ANOVA examining the effects of the simulations, online PD, and time on the percentage of DE questions asked during a 45–90 minute classroom lesson indicated no statistical differential effect of time for online PD when combined with the simulation sessions (F(1,130) = .168, p = .682, ηp2 = .001). However, there was a statistically significant interaction between time and the simulations (F(1,130) = 3.479, p = .064, ηp2 = .026). Teachers who participated in the simulations asked a significantly higher (t(132) = 3.198, p = .002) percentage of DE questions post-intervention (M = 24%) than teachers who did not experience the simulations (M = 14%). The results indicated that the targeted skill developed in the simulations transferred to actual classroom environments and support the efficacy of mixed reality simulations as a professional development tool to support teacher learning that is applied to actual classrooms (Dieker et al., Citation2017). Please see Dieker et al. (Citation2017) for further analyses, findings, implications, and limitations of the study.

2.2.4. Mixed reality simulations, teacher education, and behavior management

Results of a research study (Pas et al., Citation2016) over the course of a school year in which mixed reality simulations were embedded within a formal coaching framework, indicated positive effects on teachers’ use of behavior management strategies and student classroom behavior. An intervention employing the use of a mixed reality simulation environment within a coaching model targeted toward teachers’ use of behavior management strategies was conducted with 19 special education teachers working in non-public schools (Pas et al., Citation2016). Participants taught in self-contained classrooms that served students aged 5–13 (n = 10) and 14–21 years (n = 9). Students were identified as those with moderate to severe needs in terms of academic, emotional, and behavioral supports and included students with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

The research employed the use of a formal coaching model, the Classroom Check Up (CCU) designed to support effective classroom behavior management strategies aimed at proactive teacher behaviors that help prevent student behavior issues before they occur (Reinke, Citation2018). These strategies include active supervision, use of praise, and communicating clear behavioral expectations (Reinke, 2013). Coaches, following the CCU model, observed teachers in their classrooms and worked with teachers at the beginning of the study to identify and select one or two target teacher behaviors to improve positive student behavior in the classroom (Pas et al., Citation2016). Teachers then practiced the identified skills in the mixed reality simulation environment. Teachers practiced with middle school or high school avatars, depending on the grade level taught, for 10 minutes while being observed by the coach and another teacher (Pas et al., Citation2016). Following the simulation, each teacher received immediate feedback from the coach and observed the other teacher practice the targeted skills and receive feedback. This procedure was then repeated for a total of two practice sessions within one simulation (Pas et al., Citation2016). After the first simulation, the coach then observed the teacher in their classroom to determine the extent to which the teacher was able to apply the skills that were practiced in the simulator to their classroom (Pas et al., Citation2016). During classroom observations, coaches provided feedback to teachers to support their use of identified classroom management strategies. Teachers experienced a total of three TeachLivE™ simulations over the course of about 10 weeks (Pas et al., Citation2016).

Frequency counts of individual teacher and student behaviors, as well as overall rating scales of behaviors, were collected by research assistants via the Assessing School Settings: Interactions of Students and Teachers (ASSIST) instrument at three time points throughout the study (Pas et al., Citation2016). Data were collected before the coaching/mixed reality intervention which served as baseline data, following the coaching/mixed reality intervention, and then after about 3 months’ time, which served as follow-up data (Pas et al., Citation2016). Frequencies of individual teacher behaviors collected via this instrument were proactive behavioral expectations, reactive behavior management, approval, disapproval, and opportunities to respond. Frequencies of individual student behaviors were collected and consisted of noncompliance, disruptions, profanity, verbal aggression, and physical aggression (Pas et al., Citation2016). The ASSIST instrument consists of overall rating scales of teacher and student behaviors using a 5-point Likert scale (Pas et al., Citation2016). Overall ratings of teacher and student behavior with respect to teacher positive behavior management, teacher control, teacher monitoring, teacher anticipation, teacher and student meaningful participation, student compliance, and student socially disruptive behavior were collected using this instrument (Pas et al., Citation2016).

Frequency data of teachers’ classroom management strategies and students’ classroom behaviors were collected and analyzed via repeated measures MANOVA. When teachers’ classroom management behaviors over time were examined, significant results for time (F(2, 13) = 4.33, p = .04, partial η2 = .40), frequency counts of teacher behaviors (F(3,12) = 43.36, p < .01, partial η2 = .92), and the interaction between time and frequencies (F(6,9) = 5.25, p = .01, partial η2 = .79) were obtained indicating that teacher behaviors varied across individual behaviors and changed over time. Follow-up data analysis employing ANOVAs revealed significant increases in frequencies of teachers’ use of proactive behavioral expectations (F(2, 28) = 6.73, p < .01, partial η2 = .33), and approval (F(2,28) = 8.12, p < .01, partial η2 = .37). Moderate to large effects were observed between baseline and follow-up data for teachers’ use of proactive behavioral expectations (d = .092) and use of strategies related to approval of student behavior (d = 1.06). When differences in student behaviors over time was examined via a repeated measures MANOVA, a significant result for frequencies of student behaviors (F(4, 11) = 10.72, p < .01, partial η2 = .80) was realized. No significant results for time nor an interaction between time and frequencies of behaviors were obtained. Follow-up data analysis employing the ANOVA statistic revealed significant results over time for student non-compliance (F(2, 28) = 3.58, p = .04, partial η2 = .20).

When overall observer ratings of teacher behavior and student behavior were analyzed, significant results of the MANOVA were obtained for teacher behaviors over time (F(2, 8) = 10.64, p < .01, partial η2 = .73), scale (F(7, 3) = 46.17, p < .01, partial η2 = .95), and an interaction for time by scale (F(4, 6) = 19.28, p < .01, partial η2 = .97). With respect to student rating scales, significant results for time (F(2,13) = 7.60, p < .01, partial η2 = .54), by student rating scale (F(2, 13) = 564.24, p < .01, partial η2 = .99), and an interaction between time and student rating scale (F(4, 11) = 9.34, p < .01, partial η2 = .77) were obtained. Taken together, improvements in teachers’ use of behavior management strategies and students’ classroom behaviors were realized over time.

Significant results of follow-up data analysis via ANOVAs were obtained for observer ratings of teacher proactive behavior management (F(2,28) = 6.92, p < .01, partial η2 = .33), teacher control (F(2,28) = 17.11, p < .01, partial η2 = .55), teacher monitoring (F(2,28) = 14.10, p < .01, partial η2 = .50), teacher and student meaningful participation (F(2,28) = 9.81, p < .01, partial η2 = .41), indicating that ratings for these teacher scales increased significantly over time. A significant result for ratings of student social disruption (F(2,28) = 3.19, p = .057, partial η2 = .19) indicated improvements in ratings over time.

The acceptability of coaching and the use of the TeachLivE™ simulations were examined, as data were collected from coaches and teachers about their perceptions of the coaching experience using the coach-teacher alliance scales and ratings of the TeachLivE™ simulations (Pas et al., Citation2016). A zero to four (never to always) 5-point Likert scale was employed, and overall results for both coaching and the TeachLivE™ simulations were positive. Teachers’ scores for coaching which examined the working relationship, process, investment, and perceived benefits from the experience ranged from an average of 3.13 to 3.69; teachers scored the TeachLivE™ simulations more moderately (M = 2.77, SD = .60; Pas et al., Citation2016). Coaches’ ratings for the coaching experience ranged from an average of 2.5 to 3.26; coaches scored the TeachLivE™ simulations higher than the teachers (M = 3.05, SD = .39; Pas et al., Citation2016). Overall results of this study appear to indicate the viability of the use of mixed reality simulations and coaching to promote positive changes in special education teachers’ use of behavior management strategies that positively impact students’ behaviors in classrooms. Moreover, the results show that some positive changes were sustained, as follow-up data appear to indicate.

2.2.5. Mixed reality simulations and pre-service teachers’ perceived self-efficacy

The possible effect of increased levels of exposure to mixed reality simulations on pre-service teachers’ sense of self-efficacy was conducted within a teacher preparation program (Gundel et al., Citation2019). In the study, participants (n = 53) experienced 30, 60, or 90 minutes of mixed reality simulations embedded within their teacher education coursework. A repeated measures, one group with three levels, pretest/posttest design was employed to examine the effect of exposure level on pre-service teachers’ sense of self-efficacy, as measured by the Teachers Sense of Self Efficacy Scale (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2001). An analysis of the data, employing a 3 × 2 one-between-one-within subjects ANOVA, and follow-up t-tests, revealed a significant main effect for exposure (F(2, 50) = 5.91, p < .01) and a significant interaction between total exposure and time before and after simulations (F(2, 50) = 5.45, p < .01). The self-efficacy scores of participants in the 90 minute exposure group were significantly different than scores of participants in the 30 minute or 60 minute groups. The researchers noted that for the 60-minute exposure time, a small, nonsignificant decrease in scores from before exposure to after exposure was revealed, and this drop in scores were observed in other studies (Bautista & Boone, Citation2015).

2.2.6. Mixed reality simulation and coaching—communication skills

A pilot study was conducted to explore the effect of a mixed reality simulation environment on the learning of interprofessional communication skills of doctoral-level physical therapy students (Taylor et al., Citation2017). This simulation environment requires a human simulation specialist who operates, through digital puppetry, avatars that represent students or adults in various roles and interacts with the simulation participant in real time (L Dieker et al., Citation2008). For this study, the specialist was a teacher, trained in school-based education, and was made familiar with physical therapy medical terminology and the scenario for the simulation (Taylor et al., Citation2017). The simulations were guided by a scenario which centered around making recommendations for mobility, including a wheelchair, for a 13-year-old girl who experienced a traumatic brain injury. Adult avatars represented three adult stakeholders—a parent, teacher, and physician. Three participants experienced the simulation environment and interacted with each adult stakeholder for a period of five minutes. After each session, a 5-minute period for feedback and reflection took place. The participant then experienced communicating with the same adult avatar for another five minutes for a second simulation session. This process was repeated for all three adult avatar stakeholders; each participant experienced the simulation environment for a total of 60 minutes (Taylor et al., Citation2017). A quasi-experimental, pre-test and post-test case study design was employed, and each of the three participants were scored using a modified version of the Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) too, which provides a framework for medical professionals when communicating with health team members (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2019). Results of the study revealed that all three participants, following the simulations which included a period for feedback and reflection, were able to more effectively communicate situational and background information, as well as discuss treatment and make recommendations with all three adult stakeholders in the scenario (Taylor et al., Citation2017). Among all three participants, interactions with the parent avatar were the most challenging, whereas interactions with the physician avatar were the most successful (Taylor et al., Citation2017). However, each participant scored higher for every adult avatar interaction following the first simulation. Therefore, the results of this pilot study provide support for the use of a mixed reality simulation environment in developing interprofessional skills of medical personnel.

2.3. Conclusion

The use of video as a feedback tool in teacher professional development is well-documented (Fuller & Manning, Citation1973; Knight, Citation2014; Tripp & Rich, Citation2012) and coaching within mixed reality simulations has been shown to impact teachers’ targeted behaviors (DeSantis, Citation2018). However, mixed reality simulation environments are an emerging technology, and there is a lack of research in this area (L Dieker et al., Citation2008; Dieker et al., 2014). Additionally, pre-service teachers’ use of nonverbal immediacy skills within technology-rich environments, such as mixed reality simulations, offers another gap in the literature.

3. Research questions

Teacher immediacy skills are important in developing positive student–teacher relationships and have been shown to positively affect student motivation and learning (Christophel, Citation1990; LeFebvre & Allen, Citation2014), and align with high-leverage teaching practices. High-leverage practices are foundational teaching practices that are critical to advance student learning and teacher pedagogical skills (Ball & Forzani, Citation2010; Teaching Works, Citation2020). Further study is needed to determine the effectiveness of the emerging technology of mixed reality simulations within teacher preparation programs to impact teacher learning and practice to positively affect students (L Dieker et al., Citation2008) and specifically, to understand pre-service teachers’ immediacy behaviors those simulations. The purpose of this study was to explore the effect of video and reflection, video feedback and coaching within mixed reality simulations on pre-service teachers’ nonverbal immediacy skills within a teacher preparation program. To guide this inquiry, the following research questions were addressed:

Using the Nonverbal Immediacy Scale—Observer Report (NIS-O), is there a statistically significant difference over time between pre-service teachers’ nonverbal immediacy behaviors for three rounds of data collected, before, during, and at the conclusion of a semester, in which a video and reflection, video feedback, and coaching treatment package is administered following mixed reality simulations?

What are the perceptions of pre-service teachers’ reflection and use of nonverbal immediacy behaviors over the course of a semester in which they received video, video feedback, and coaching while utilizing a mixed reality simulation environment?

4. Method

The overall design was an embedded mixed methods research design (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2011). Quasi-experimental quantitative, one-group-within-subjects design (Gall et al., Citation2003; Hinkle et al., Citation1998) was utilized to address the quantitative research question. Time served as the independent variable and scores obtained via the NIS-O (V.P. Richmond et al., Citation2003) was the dependent variable. A qualitative case study design (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018; Yin, Citation2014) was used for the qualitative data, which were secondary and supported triangulation of data sources.

4.1. Setting and participants

The current study took place at a university located in the northeastern United States. A total of 15 (n = 15) undergraduate pre-service teachers participated in the study; 10 participants identified as female, while 5 participants identified as male. Twelve participants indicated they were Caucasian while the remaining 3 participants stated their ethnicity as Hispanic/Latino. Most participants had experienced the mixed reality simulations a total of two previous times as part of previous coursework within their teacher preparation program.

Pre-service teachers were in their second, third, or fourth year of study and were enrolled in a second course in a series of two-part coursework in educational psychology. The simulations employed the use of scenarios (Piro & O’Callaghan, Citation2016b) that were aligned with the high leverage teaching practice of using questioning techniques to elicit student thinking (Ball & Forzani, Citation2010; Teaching Works, Citation2020). The course embedded mixed reality simulations within its curriculum and focused on verbal teaching strategies, namely higher order questioning skills. There was no focus on nonverbal communication skills within the course curricula and the majority of participants indicated they had never received training in nonverbal communication. The curriculum for the course embedded three simulations and a field experience.

4.2. Simulation lab

The Mursion® environment looks much like an elementary, middle school, or high school classroom and includes props such as whiteboards, books, and desks (Dieker et al., 2014; Mursion, Inc.). Sitting at a desk are a diverse group of student avatars representing a range of personality types and abilities, that can exhibit certain behaviors depending on the objectives of the simulation (Dieker et al., 2014). Simulation specialists are trained to control the student avatars to enable learners to “… become empathetic to the emotions, abilities, and circumstances of the avatar” (Mursion, Inc., p. 2). In this environment, the pre-service teacher can practice a teaching strategy, behavior management technique, or other targeted practice while having the opportunity to pause the simulation to correct any errors or to get feedback and restart the simulation (Dieker et al., 2014; Dieker, Rodriguez, Lignugaris/Kraft, Hynes & Hughes, 2013). The controlled environment, unlike a real classroom, allows for pre-service teachers to engage in multiple rehearsals of a practice without affecting live students or taking up valuable classroom instructional time (Dieker, Rodriguez, Lignugaris/Kraft, Hynes, & Hughes, 2013; Dieker et al., 2014). The simulations provide pre-service teachers the opportunity to deliver lessons to student avatars of different personalities, abilities, and cultural backgrounds that are reflective of real classrooms today (Dawson & Lignugaris/Kraft, 2017; Dieker, Rodriguez, Lignugaris/Kraft, Hynes, & Hughes, 2013). illustrates the participant view of the virtual classroom.

Figure 1. Virtual classroom in simulation lab (Mursion, Inc., Citation2019b)

4.3. Quantitative design

A quasi-experimental, one-group within-subjects design, with three levels (Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3), was employed within the embedded mixed method design to address research question one (Gall et al., Citation2003; Hinkle et al., Citation1998). The independent variable was time, with three levels (Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3) and the dependent variable was the scores obtained from the NIS-O instrument. Observations with analysis and the administering of the three components of the treatment package were conducted as shown in a visual representation of the quantitative design in .

4.4. Qualitative design

A case study design (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018; Yin, Citation2014) was employed to address research question two. The case was bounded by enrollment and participation in an educational psychology course over one semester where mixed reality simulations were embedded into the curriculum (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018; Yin, Citation2014).

5. Treatment package introduction

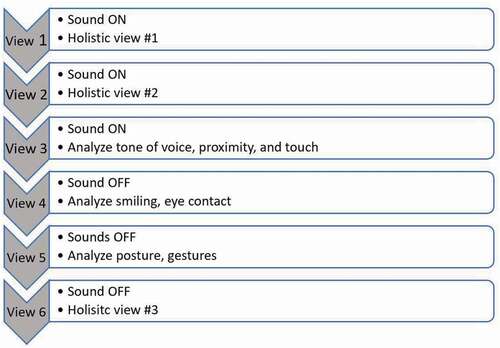

A video analysis process following each of three mixed reality simulations experienced by pre-service teacher participants preceded the treatment. Participants received a treatment package following each simulation consisting of three components: video and reflection, video feedback, and coaching, that was targeted at improving the pre-service teachers’ nonverbal immediacy skills as they delivered lessons to student avatars.

5.1. Treatment instruments

Mixed Reality Simulation Video Capture. The mixed reality simulations were recorded using a customized recording system that captured both participants and student avatars as the pre-service teachers delivered lessons and interacted with the simulated students (see ). The video recording captured each entire mixed reality simulation session for all participants in one video file.

Figure 3. The mixed reality simulation video capture recorded the face and body of the standing pre-service teacher participant and the seated student avatars as the pre-service teacher delivered a lesson and interacted with the avatars

The professor of the course and pre-service teachers enrolled in the course were captured in the background. Image used with permission (Mursion, Citation2019b).

Nonverbal Communication Behavior Observation Tool (NCBOT). The researcher-created NCBOT collected frequencies and durations of participants’ use of nonverbal immediacy behaviors with student avatars within simulations via video reviews of performances. The nonverbal immediacy behaviors of gesturing, smiling, proximity, eye contact, relaxed posture, varied tone of voice, and touch were identified, however, the behavior of “touch” was not included in data collection or analysis due to the nature of simulations. Video time stamp information, total length of the video of the simulation, and researcher notes were also collected via this observational tool.