Abstract

The number of children with autism is increasing worldwide. These children like all other children should be provided with equal chances for learning and education. Thus, English language education is not an exception as the need to learn it in today’s world is inevitable. The present study sought to investigate the effect of employing Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) on English as a foreign language vocabulary learning relying on its effectiveness in first language communication. As a single-subject study an experimental A-B design was employed through repeated measurement. The participants were two high-functioning children with autism aged 9 and 12 at a school for students with special needs. The treatment phase included 15 sessions. An analysis of visual inspection and graphic representation revealed performance improvement in both cases after the intervention. Moreover, some problems while educating the two participants for English vocabulary including lack of cooperation in phase 2, lack of attention and cooperation in mid-intervention, sense problems such as proprioceptive and vestibular are reported through qualitative analysis of the reports made of weekly sessions.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Currently, there is an increasing demand for the teaching of English as an international language to children with and without special needs. While the number of children with autism is growing all over the word more need is felt to find ways for educating them. In the present research we sought to find out if Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) that had been suggested for teaching the first language communication for such children could be used for improving their vocabulary in English as a foreign language. The findings suggest that PECS can be effective in vocabulary learning of the children with autism.

1. Introduction

Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a large and complex disorder which includes many elements and children with a diagnosis of ASD can display varied behaviours and difficulties. The occurrence of ASD has raised concerns at the local, national as well as international levels which has led to action (Rice et al., Citation2012) and in the recent decade there has been a rapid increase in the number of children with autism worldwide (Hasan, Citation2020). Some of these children, highly functioning autism, are getting integrated into the mainstream educational systems (Jelínková, Citation2019). Despite all the disabilities, this group of students also have the right to be facilitated in being educated in all areas including learning the English language. Accordingly, several researchers also suggest the possibility of communication and education in a foreign/second language in children with autism (Elder et al., Citation2006; Petersen, Citation2010; Reppond, Citation2015; Szymkowiak, Citation2013; etc.). Kuparinen (Citation2017) highlights that “one does not need to be intellectually gifted in order to learn a foreign language. However, certain methods of language learning should be intelligently followed to make the language learning process more fruitful.” (p. 39). Also, Wire (Citation2005) highlights that even those who have little speech, possibly an elective mute, may have a good understanding of the foreign language and may be able to respond by actions in a role play, by nodding, drawing and by practicing with a pocket translator.

Different methods have been developed to improve communication, PECS was also developed as a communication system that could be taught very rapidly to children with autism who have no or few functional communication skills (Ryan et al., Citation1990). According to Wire (Citation2005), facing repetitive and familiar phrases or sequences visually will make this group of students excited and this repetition is a constructive factor. Moreover, the pictorial approach of PECS can be a facilitating element as it has an increasing effect on such students’ concentration (Dyrbjerg et al., Citation2007).

2. Foreign and second language teaching to students with autism

Several researchers have attempted to look for possibilities in teaching English as a foreign or second language to this group of students. Some have employed behavioral and cognitive coaching (Khodaverdi et al., Citation2018), others have implemented Montessori-Oriented versus Audio-Lingual Methods (Rezvani, Citation2018), Individual Education Plan (IEP) provided with visual media and co-teaching (Padmadewi & Artini, Citation2017). Employing technology other researchers have made attempts in using humanoid robots for teaching English to these children (Alemi et al., Citation2015). However, concerning the strengths of such students in visual channel (Kuparinen, Citation2017; Schopler et al., Citation1995) as well as its emphasis on applied behaviour analysis and social communication which are efficient strategies in teaching English to children with autism (Castillo & Sanchez, Citation2016), PECS can be a promising approach to be implemented with an aim of teaching a foreign language.

3. Picture exchange communication system

Picture exchange communication system is an approach which is based on behavioural analysis. It promotes meaningful communication that has to be initiated from the child’s side rather than the others. Here the focus is on the “exchange” through which the child learns the ideas related to communication such as approaching or interacting (Baker, Citation2007). The underlying concept of PECS, which is based on the behaviourism theory, is that learning is a result of particular behaviours related to the receiving of a reward. This rewarding system will reinforce the child’s behaviour that will have the consequence of the child’s repetition of the behaviour (Bondy & Frost, Citation2011). Frost (Citation2002), when PECS is used for autism, considers communication as a behaviour and determines the need for a speaker and a listener. However, it is highlighted by Frost that this communication is in the form of an exchange with a requested item which can encourage the child’s skill of requesting while the child receives the required item as a sort of reward.

Numerous articles are published in support of the use of the PECS. These studies, focusing and concerning communication in the first language, have indicated rapid acquisition of a functional communication system (Ganz & Simpson, Citation2004; Kravits et al., Citation2002; Magiati & Howlin, Citation2003; Schwartz et al., Citation1998), increased speech (Ganz et al., Citation2012; Kravits et al., Citation2002); decreased problem behaviours (Frea et al., Citation2001; Greenberg et al., Citation2012). However, the implementation of this system in instructing the child with autism to learn a second or a foreign language has still been an untouched area in research.

Picture exchange communication system involves six phases (Ganz et al., Citation2012; Welch, Citation2010). Each phase is described in detail below:

3.1. Phase 1: how to communicate which aims at the “initial communication training”

In this phase, PECS teaches the child to pick up a single picture, reach toward the communication partner, and release it in his/her hand. This skill is taught with two trainers initially. One trainer, in front of the child, acts as the communication partner. The second trainer, behind or next to the child, provides physical prompts. However, the presence of two trainers is key if the student does not make initiations and then a physical prompt’s function (a second prompter) is to “physically prompt pick up, reach, or release” (Bondy & Frost, Citation2011, p. 4). However, if the child has the initiation no second prompter is needed. Also, a preferred reinforcer is also provided for which the child reaches to gain. After releasing the picture the child can have access to the reinforcer. This reinforce has to be desirable to the child and must be among the items that the child likes to hold or have. And it has to be located out of the reach of the child to encourage the communication through exchange. Verbal prompts are not used all over the training. A trial starts with the communication partner through presenting a preferred item. The physical prompter has to wait for the learner’s initiation that can be in the form of reaching for the item, and then the trainer provides an immediate physical prompt. Waiting for initiation leads to spontaneity and that will decrease the risk of dependence on the prompt (Welch, Citation2010). Following the later trials, physical prompting fades until the learner exchanges the picture independently.

3.2. Phase 2: distance and persistence which aims at “retrieval and delivery of icons”

In Phase 2 the learner is taught to walk to the communication book, remove a single card from the communication book cover, and then approach the communication partner. These skills are trained progressively by increasing the distance between the child, the partner, and the communication book slowly. This encourages the child to put some effort in achieving a desired result (Bondy & Frost, 2002). Similar to the first phase there is no verbal prompt. The physical prompts provided by the second trainer have to fade away through backward chaining (Welch, Citation2010). Backward chaining includes the instruction of the last stage to let the child enjoy the success gained by completing a task. It can develop confidence (Hanna, Citation2001). This focus on the terminal stage will lead to the independence of the child (Granpeesheh et al., Citation2014). Gradually the effort amount as well as persistence need to be increased for the learner. The learner has to retrieve those items that he/she desires from the communication book (Ganz et al., Citation2012).

3.3. Phase 3: picture discrimination which aims at “icon and item discrimination”

This phase instructs the learner to recognize that presenting the partner with different icons will lead to various consequences (Ganz et al., Citation2012). Two items including a much desired one and a less-desired one are presented at this stage. In fact the learner discriminates between a picture of an item which is highly preferred and a neutral item. Having mastered this skill, the learner discriminates between pictures of the items that are preferred. The learner has to recognize that he will receive the item if he chooses the right preferred item. To do so, the communication partner has to arrange two pictures on the communication book cover, and must present a neutral item as well as an item which is preferred. Having learnt to identify the more preferred one, the learner must be presented with two equally desired items. Once the child touches the picture of the preferred item, social reinforcement such as praise is brought, to immediately reinforce the new skill. When the preferred card is exchanged, the child receives the item. If the child touches the non-preferred icon, no social reinforcement is offered and the child receives the non-preferred item. In this case, an error correction policy is used as is described below (Welch, Citation2010, p. 4):

Model – The trainer models the correct response by pointing to the picture of the preferred item.

Prompt – The trainer prompts the child to exchange the correct picture, for example, by holding her hand open near the picture. This is called physical prompt. Social praise is used to reinforce the correct exchange.

Switch – A brief pause or single trial of a non-related, mastered skill is performed.

Repeat- The communication partner again offers the preferred and non-preferred items to give the child a new opportunity to request.

Doing so prevents the reinforcement of prompted responses by way of demanding for a correct response prior to delivering the desired item. If the exchange of the non-preferred picture continues, the error correction procedure may be repeated up to three times. If no success is gained, the trainer will only show one picture on the book with the aim of returning the child to a previously grasped skill. In case of success in discriminating between preferred and non-preferred pictures, discrimination between preferred pictures is introduced. In exchange of a picture, a correspondence check is completed through presenting both items to the child and allowing him to choose. If the child chooses the item which corresponds to the exchanged icon, the correspondence check proves the accuracy of picture discrimination. However, choosing the other item, the child in fact has not accurately discriminated between pictures. Then and there, the procedure of error-correction will be employed as explained previously (Ganz et al., Citation2012; Welch, Citation2010).

3.4. Phase 4: sentence structure aims at making phrases

The child is taught to arrange several icons on a strip in order to communicate the phrase “I want” added to a specific item. Then, he/she hands in the entire strip to the communication partner. Backward chaining is implemented for this skill. In order to provide sentence structure the “I want” icon is already put in the sentence strip. As the next stage, after the learner initiates through handing in a single card there must be physical prompts. As soon as the learner initiates he is prompted for putting the card on the strip and for an exchange in the strip.

For the next stage, the learner is prompted to arrange the “I want” card together with the item picture on the strip. Next, the learner points to every picture on the strip after exchanging. A time delay together with “differential reinforcement” is employed motivate verbalization. If verbalization happens then a greater amount of the reinforcer is given to the student. But if it does not happen the learner will still be given the reinforcer in a smaller amount. Attributes are used to as a means to request for particular reinforcers. Having learned the combination of icons on the sentence strip, the learner then learns to use attributes for achieving specific items. The child has to arrange three icons on the sentence strip; however, there is no need to discriminate between attribute icons. Having mastered this skill, the child will learn to distinguish between high and low preference attributes. Picture discrimination is taught by the four-step error correction explained before. Mastery of picture discrimination will let the discrimination between preferred attributes as well as using correspondence checks. Finally, a variety of attributes are introduced and the learner can apply them to other items. Learning to communicate using the sentence strip will compensate for lack or no verbalization and children to lack the tendency to reach for an item or point to it will benefit this method (Ganz et al., Citation2012).

3.5. Phase 5: responding to “what do you want?” aims at answering questions

This phase includes using the sentence strip (exchanging) for answering verbal questions (Bondy & Frost, 2002). Progressive-time delay is implemented for the mastery of this skill. This is done “with an immediate prompt to begin with increasing time delay to the prompt over subsequent trials” (Welch, Citation2010, p. 6). Thus, some time delay is considered here. The student continues to have many opportunities to spontaneously request items. This is done by prompting the child to use the “I want” icon subsequent to which she/he can have access to the desired item. This process also includes reinforcers. Little by little other related questions can be asked such as “what do you see?” which will lead the child to the next phase.

3.6. Phase 6: commenting which aims at spontaneous commenting

In this phase, there will be spontaneous commenting of the student by responding to other questions such as “What do you see?”, “What do you hear?”, “What do you have?”, and “What is it?”. Indirect reinforcement in the form of social reinforcers is used at this stage rather than the actual access to the desired item (Ganz et al., Citation2012). This permits comments to be noticeably distinguished from commands and makes the reinforcing of appropriate responses more challenging as compared with the previous stages (Bondy & Frost, 2002). Thus, a variety of sentences can be used by the learner. Arrangement of the environment is necessary so that there would be something interesting to comment on. “Using social reinforcement only is important, because the skill is a comment rather than a request” (Welch, Citation2010, p. 6). Over successive attempts, the lengthening of the time delay for the prompt is implemented while waiting for the student’s independent exchanges “of the sentence strip with the comment icon”. Following that, the student learns to discriminate between “I want” and commenting icons and may also use the attributess. Picture discrimination is taught by the four-step error correction explained previously.

4. Vocabulary learning in children with autism

Word knowledge is a foundation for many other aspects of language and for achievement (Davis et al., Citation2016). In other words, vocabulary learning is a very important part of language learning. A number of intervention strategies have been successful at improving vocabulary in pre-school-aged children with autism with vocabulary deficits.

Other studies on children with autism have also focused on vocabulary learning gains (Alemi et al., Citation2015; Khodaverdi et al., Citation2018; Moghadam et al., Citation2012; Romadlon, Citation2017; Szymkowiak, Citation2013) as the basic component of communication. Practical vocabulary can be the core in successful communication in a foreign language (Kuparinen, Citation2017). PECS, an augmentative and alternative instruction for students with autism, is based mainly on word-picture-object associations and the students’ gains in learning English in this study is mainly concerned with the teaching of vocabulary.

Accordingly, the present study aimed at contributing to the intact area of English language teaching to children with autism by employing PECS as a well-established form of communication training among these children. The following research questions were answered based on the objectives which were to find out the effect of PECS on English vocabulary learning as well as the problems a teacher could encounter while using this system for teaching English vocabulary.

(1). To what extent does using PECS have any significant effect on English vocabulary learning on Iranian children with autism?

(2). What are the problems faced by teacher while using PECS to teach English vocabularies to children with autism?

5. Materials and methods

The present study employed a single-subject experimental A-B design having the three components: (a) repeated measurement, (b) baseline phase, and (c) treatment phase (Engel & Schutt, Citation2017). The baseline included the evaluation of the children on their English knowledge which was consistently zero throughout the three sessions. The treatment phase included the employment of PECS in teaching English vocabulary. The repeated measurement included the assessment of the vocabulary learnt every session together with the previous session’s words.

5.1. Participants

The sampling procedure in this study was through purposive sampling. In such an approach, the participants are selected based on specific features according to the objectives of the study and the inclusion criteria (Jacobson et al., Citation2016). While this research enjoyed a single-subject design, which is very common in autism, two male participants were selected. Due to the heterogeneous feature of autism, the findings cannot be readily generalized to other contexts (Cardon & Azuma, Citation2011). Thus, the findings may not be generalized to female or other age groups with a different level of functioning. The two male participants, aged 12 years and 3 months and 9 years and 3 months, attended a public school.

Both of the participants were diagnosed with ASD previously by a medical and educational professional independently of this research in their school. The researchers confirmed the participants’ diagnoses through the implementation of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (Schopler et al., Citation1988). The participants were deficient in social skills (e.g., few interactions with typical peers, few initiations of conversations) as described by their parents, teachers and therapists. Pseudo names are used to introduce the participants.

Arman’s (the first participant) diagnosis was confirmed by a current rating in the moderate autism range on the CARS (Total score = 36.5). His intellectual ability was “below average” according to the TONI-3 (Q = 80). Though Arman could speak spontaneously, he did not frequently initiate conversations. He was able to answer basic conversational questions except for novel or abstract ideas in his first language. Arman occasionally got engaged in delayed echolalia, repeating lines from songs or movies.

Saman’s (the second participant) diagnosis was confirmed by a current CARS score in the severe autism range (Total score = 38.5). His score indicated “average” intellectual ability (Q = 85). Saman often spoke spontaneously and initiated conversations, though he did so in a rote manner.

5.2. Instrumentation

This research was mainly concerned with the assessment and evaluation of the English vocabulary learnt by these two cases instructed by PECS. However, the assessment of the vocabulary learning was based on the understanding of the students as well as their ability to recognise the pictures related to the words. There was no written test as the teaching of the English alphabet was not the concern. So, vocabulary learning was assessed through the student’s ability to either point to the related picture or hold and show the picture. To collect data on the problems and challenges faced by the teacher the sessions were all video recorded which is one of the most advocated techniques in conducing single-subject studies (Gast & Ledford, Citation2014; Jewitt, Citation2012; Knoblauch & Schnettler, Citation2012).

5.3. Procedure

The researchers received permission from the Special Education Organization (#9716.314.13006, date: 23.10.2018). Also, consent was received from the principal of the School where the students studied (#157, date: 21.01.2019) as ethical clearance. All 50 students were evaluated for the possibility of being a part of this study. Based on the teachers’ recommendations, 2 students were selected as they were highly cooperative in their regular courses. For ethical issues consent was received from the parents of the two participants. It was also clarified in the consent that they had the right to withdraw from the experiment at any time as their participation was voluntary.

Materials employed in this study included a variety of flashcards, mini objects, plastic boxes, a picture book, a camera, rewards, and toys. The snacks included cake, candy, fruits, cookies and toys. The content of the flash cards included 45 words related to the categories of animals, clothes, family members, colours, school objects, shapes, foods, fruits, feelings, etc.

At the onset of the study as a single-subject A-B design, which is also termed as simple variant of the baseline and the intervention, the baseline data for three sessions was collected to illustrate a stable pre-intervention pattern of English vocabulary knowledge. Before the study started the researchers prepared the required materials such as the flash cards and the picture book where the student could stick the pictures to form short sentences using the pictures in later phases of PECS. The words that the teacher taught were among a list of possibilities that could include the interest of the students.

The two students were instructed separately in different classes for a length of 15 sessions and for one session per week. The different steps of PECS were taken apart from the inclusion of another partner as the physical prompter in phase 1 which was not implemented due to the fact that the students made initiations and a physical prompt’s function is to wait for initiations from the child and if this does not happen that physical prompter will “physically prompt pick up, reach, or release” (Bondy & Frost, Citation2011, p. 4). The phases of PECS were taken as described by (Welch, Citation2010) and Ganz et al. (Citation2012). Also assessment on vocabulary learning was done all through the sessions.

The researchers videotaped all the 15 sessions in order to collect data on different phases of PECS and problems which were faced by the teacher while using PECS to teach English vocabularies. To clarify the intervention, one session of the treatment is explained in detail as follows.

The session aimed at teaching English vocabulary related to animals. First of all, the teacher provided a list of animals the student preferred (the list changed every session according to the topic). The preference was evaluated based on the pictures. The student would offer a variety of these items (e.g., dog, cat, fish …), to determine which he chose most often. The teacher attempted to train the student to hand a line drawing to the teacher for a desired item. During this and the following phases, the teacher verbally modelled the pictures the student handed to her.

After that, a duplicate of each item was placed in a small, clear plastic box and placed in front of the student. When the student touched the box within 10 seconds it was put on the table, and he was given the item and the teacher verbally labelled it. After that, Phase 2 procedures which were the same as phase 1 followed, except that a photograph of the item was attached to the box and the student was required to pick up the box. Next, discrimination with Boxes (modified) was done. In phase 3 there were two boxes: one with a preferred item and one with a non-preferred item. When the student picked up a box with a preferred item, he was given the item. After that, in Phase 4 the two boxes containing preferred items were placed on the table. Correspondence checks and error correction procedures were also conducted (Bondy & Frost, Citation2011). Finally, the same as Phase 5, with the boxes removed, only the photograph was left. In all phases of PECS as soon as the student chose the desired item the English word related to it was pronounced and also reinforced by repetition. Moreover, to improve communication short conversations related to greetings were used and practiced with the student. Also, in final stages of PECS the student could respond to questions such as “what do you want?” or could complete the statement “I want … … ” .Also, he could make short sentences using the pictures and sticking them in the picture book by maintaining the correct order of words including “I want”.

Moreover, it needs to be mentioned that at the beginning of every session except the first session a review of the previous words was done by the teacher. Also, an assessment of the student was conducted at the end of every session. As for the purpose of repeated measurement assessment of the vocabulary knowledge was done in sessions 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15. All through the study a PhD holder in occupational therapy who had expertise in autism rated the evaluations of the qualitative data, qualitative data analysis and the children. Thus, there were two raters, one of the researchers and the occupational therapist. To achieve inter-rater (inter-observer) agreement the percentage of agreement on observations was calculated for a frequency ratio (Colton & Covert, Citation2007) which is calculated based on the number of agreements and disagreements.

6. Data analysis

Each of the treatment integrity observations was performed with 100% accuracy. The inter-observer reliability was calculated as the total number of agreements divided by the total number of agreements plus disagreements, then multiplied by 100. Inter-observer agreement was assessed throughout baseline, treatment for 28% of Arman’s probes with reliability averaging 98% (range = 88%–100%), assessed for 34% of Saman’s probes with reliability averaging 100%.

The researchers also calculated the Percentage of Non-overlapping Data (PND) for both participants to supplement visual analysis of graphed data in order to determine the effects of the intervention (Scruggs & Mastropieri, Citation1998).

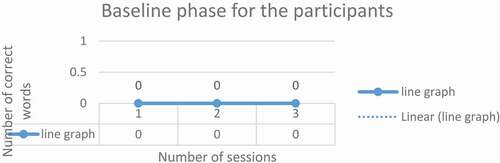

6.1. The Baseline phase

Baseline data were collected until each participant demonstrated a consistent level of performance. As a result of the constraint of the limited duration of research time it was determined that 3 sessions of baseline measurement using three data collection points was adequate for the learners to demonstrate a consistent and definite pattern in English word knowledge. The results were graphed immediately on a line graph to provide a visual description and the information was consistently examined to focus on the visual trend as well as the level and variability. In this regard, as the visual representation of each participant’s performance revealed scores which fell within a non-range, this demonstrated observable stability in the English word knowledge.

The condition was also conducive to make the prediction that the application of the independent variable (PECS) could result in an improvement in the English word knowledge level. presents the number of correct responses for words for the two participants.

During the baseline, they had an average performance of 0 correct responses. Data trend in the baseline was steady. The data trend in this phase was flat.

6.2. The intervention phase

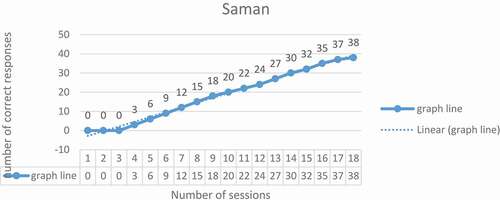

Identified as “B-B”, for this phase numerical and graphical data were used to measure and evaluate each participant’s vocabulary learning (the dependent variable). According to Gay and Airasian (Citation2003), “data analysis in single subject research is typically based on visual inspection and the analysis of graphic presentation of results”. The data for the two participants during the 15 weeks of the intervention are presented below.

As presents, a rapid movement upwards from baseline data point 3 to data point 9 in intervention was observed. There was moderate variation between his performance at data points 9 and 17, indicating that his level of improvement was slower than before when he learned two words per session. The results suggest that he maintained the level of improved performance. On the last point (18) word learning was 33% with a low level of improvement. Overall, the data revealed a marked improvement in Saman’s vocabulary learning at the intervention phase; this improved to competent vocabulary learning (84%) when compared to his performance at the baseline phase (0 %).

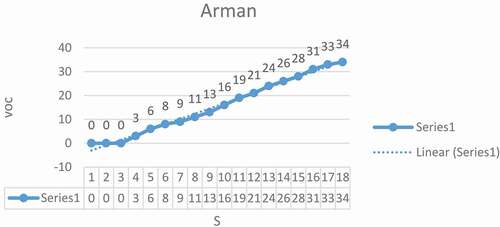

provides a summary of Arman’s total number of correct words during baseline and intervention phases.

During baseline, Arman had a rapid upward movement (100%) in his performance at the intervention phase in the variable at data points 3 to 5. Although his performance showed a moderate increase (66%) at points 6, 8, 9,12,14,15 and 17. Arman also showed a trend in his performance of a marginal increase (33%) at data points 7 and 18. Arman’s performance at the intervention phase was 100% in data points 10, 11, 13 and 16. In the intervention phase, his improved performance resulted in an upward trend, based on an increase in percentages from data point 3 through data point 18. Significantly, a comparison of the data from the baseline phase with the intervention phase shows that the application of PECS resulted in an improved performance and a higher level of vocabulary learning. Hence, this satisfies the prediction at the baseline that Arman’s performance was consistent, and suitable for intervention. His vocabulary learning improved from 0% at the baseline to 75% distinguished at the intervention.

The researchers also calculated the Percentage of Nonoverlapping Data (PND) for each participant to supplement visual analysis of graphed data to determine the effects of the intervention. PND is calculated by dividing the number of intervention data points that exceed the highest baseline data point by the total number of intervention phases data point, multiplied by 100 (Scruggs et al., Citation1987). Scruggs and Mastropieri (Citation1998) recommend the following guidelines to evaluate PND scores: scores higher than 90% suggest highly effective interventions, scores from 70% to 90% indicate effective interventions, scores between 50% and 70% indicate questionable interventions, and scores below 50% suggest ineffective interventions. Both participants rapidly responded to the intervention in an upward trend and had high PNDs with 84% and 75%, which again suggest the effectiveness of the intervention through the employment of PECS.

6.3. Analysis of the videotaped observations

“Naturally occurring” data which were videoed were used especially as the research involved some interaction (Jewitt, Citation2012). In the present study the data were qualitatively analysed to determine the participants’ actions (Bowman, Citation1994) to look for motivation, attention, cooperation, instruction time, echolalia, daily mood, environmental interruptions, fatigue, stereotypical moments, etc. An interpretive method was employed focusing on actors, setting and the interactive context (Knoblauch & Schnettler, Citation2012). Moreover, to ensure that the effect of subjectivity on the part of the interpreters (researchers) is controlled another expert (a PhD holder in occupational therapy) who has experience working with students’ with autism also confirmed the analysis results.

6.3.1. Analysis of the data related to Arman

6.3.1.1. Phase 1 (Generalizing)

He had a high cooperation up to sessions 7 and 8. He did not cooperate after these sessions and he was inattentive.

6.3.1.2. Phase 2 (Distancing)

During the early sessions he was interested to this phase. After sessions 7 and 8 however he showed no interest to continue this phase. Even if he stood up to do the phase he would push himself against the surroundings. These behaviours were evident from session 9 to 15. Thus, the teacher was forced to eliminate this phase in some sessions.

6.3.1.3. Phase 3 (Discriminating)

This phase was completed with full cooperation up to sessions 7 and 8. As the number of words increased, he needed the teacher’s assistance to remember the words. He would sometimes ask “what was this?” or “what do we call this?”

6.3.1.4. Phase 4: (Sentence making)

Up to session 8 the cooperation was complete and he would easily say “I want … … ”. However, as the number of vocabularies and structures increased, Arman needed assistance to remember.

6.3.1.5. Phase 5: (Answering questions)

He would complete this phase successfully up to sessions 5 and 6 by answering questions “What is it?” or “What do you want?”. However, after that as the number of words and structures increased he needed the teacher’s help after sessions 8 and 9.

6.3.1.6. Phase 6 (Commenting)

This phase was done well by Arman up to session 10. After session 10 he needed teacher’s assistance. He would still answer questions such as “What is it?” or “What do you want?” easily but would answer questions such as “Are you happy?” Or “Who is she?” with difficulty.

6.3.2. Analysis of the data related to Saman

6.3.2.1. Phase 1 (Generalizing)

He would cooperate with full interest and preference to exchange flash cards and real objects. However, this interest would differ with the kinds of words that were taught in sessions (for example, he would show high interest to animals and toys rather than geometric shapes). This phase was followed by him effectively all through the 15 sessions.

6.3.2.2. Phase 2 (Distancing)

This phase was interesting to him up to sessions 7 and 8 as he would change place and move around the class but gradually after session 8 on he did not show interest to do this phase. Even if he did, he would be distracted to the environment and lost attention. The teacher would prefer to omit this phase on and off during sessions 8 to 15.

6.3.2.3. Phase 3 (Discriminating)

Discrimination was easy for him during the initial sessions but as the number of words and structures increased he had difficulty. For example, he would remember the same session words but would not be able to remember the previous sessions’ words. It became more difficult from sessions 7 and 8 on.

6.3.2.4. Phase 4: (Sentence making)

He would use “I want … .” with ease up to session 5 and without any hesitation. But from sessions 8 on as the number of words and structures increased he faced difficulty to produce sentences using the new words and structures.

6.3.2.5. Phase 5: (Answering questions)

The answering questions phase was completed smoothly up to sessions 7 and 8 because the structures and words were limited in number.

6.3.2.6. Phase 6 (Commenting)

This phase completed with ease and fully up to sessions 7 and 8. However, as the number of words and structures increased he needed the teacher’s assistance

6.4. Specialized analysis of the occupational therapist for Saman

Employing conditioning for the child with food and verbal incentives.

The researchers used incentives for Saman to attract his attention to the teaching and PECS phases. This was done before, during, and after teaching.

Having limited interest and the use of repeated words or asking for a specific item such as “the laptop”.

Having limited span of attention.

If an item attracted his attention he was careless of the phases and the teaching and devoted all his attention to that item.

Preferring a predictable rhythm.

When the rhythm of teaching and activities differed he demonstrated intense behavioural reactions.

6.5. Specialized analysis of the occupational therapist for Arman

Taking medications which led to being drowsy and bored.

This was evident during most sessions and it negatively affected Arman’s learning and concentration.

Preferring a predictable rhythm in class.

In case the order of activities changed he would demonstrate excessive behavioural reactions.

Demonstrating several sense problems including proprioceptive and vestibular.

Arman threw himself on the table and pushed the chairs and desk. Also, he hit himself against the desks and chairs while walking.

Having high and low moods.

It was also observed that the child’s cooperation differed in various sessions. This can be justified according to the fact that different environmental factors may affect such children’s attention including the arrangement of chairs.

Having limited verbal skills and not using the pronoun “I”.

There was a confined use of the pronoun “I”.

Not recognizing and understanding body language and abstract ideas.

For example, if he did something wrong such as pushing the chair the teacher’s facial expressions could not work the situation out and the teacher had to say directly that “You should not do this”.

7. Discussion of the findings

Despite its common clinical use, no well‐controlled empirical investigations have been conducted to test the effectiveness of PECS in teaching foreign languages to ASD children. Based on the analysis, the percentage of non-overlapping data points were 84% and 75% for Saman and Arman, respectively, indicating that PECS was a highly effective intervention for these two learners. This study extends the line of research for students with ASD. Across phases, Saman’s data illustrated an increasing trend, particularly during the intervention. Also, the PND calculated for Saman resulted in a score of 84%, which suggests a highly effective intervention.

In addition to word learning within the classroom, Saman generalized these skills across settings and people. Saman demonstrated a skill learning via initiating to others or self-initiation. Saman’s teacher reported anecdotally that following PECS, he frequently and spontaneously, at home and school, asked adults and the siblings to tell him the name of items. Though this could be interpreted as delayed echolalia, Saman used it in a functional manner, incorporating others’ answers into his own verbal repertoire.

The results indicate that the application of the intervention was effective for the improvement in their English vocabulary learning. Other researchers have also proven PECS as an effective technique in increasing speech (Ganz & Simpson, Citation2004; Kravits et al., Citation2002), acquiring a functional communication system (Ganz & Simpson, Citation2004; Kravits et al., Citation2002; Magiati & Howlin, Citation2003) as far as first language communication is concerned. However, its employment is also recommended for the teaching of foreign languages (Ganz et al., Citation2012) which can be viewed in support for the present study. In the same vein, having reviewed a number of 13 studies involving 125 participants, Tien (Citation2008) concludes that it “is an effective intervention for improving functional communication skills appeared to be supported by the available research evidence” (P. 1).

Analysis of the videos also revealed some of the problematic areas. Firstly, cooperation in phase 1 was evident in both children. However, it declined through sessions following sessions 7 and 8 in phase 2. Despite this decline, both children learnt the steps very easily and fast. This might be due to the fact that this group of children have the tendency to acquire tasks which are presented in an organized and concrete format rather than an abstract format (Schopler et al., Citation1995). Moreover, the same situation was observed by Charlop-christy et al. (Citation2002) who experienced a longer time and more challenge working through phases 2 and 3.

Additionally, with the number of words increasing, phase 3 became more difficult and recycling of the previously taught words was desired. Also, after session 8 when new grammatical structures were introduced the students encountered difficulty in uttering the sentences. More pauses were employed by the students after session 8 in response to the question ”What do you want?” To overcome this issue it is advisable that the sentence making and question answering stages be based on more simple forms and shorter syllable words.

Also, throughout sessions one to eight a more approachable interaction was achieved by the teacher and the students were engaged in one activity for longer times. This is called cooperative play which entails social-communicative category when a child settles on a task for more than 10 seconds (Charlop-christy et al., Citation2002). While lack of interaction is widely accepted as a problem for this group of children, the intervention seems to have been successful for providing this context in which the children could keep interacting with the instructor.

Another problem faced by the teacher was throwing of objects which is also mentioned by Charlop-christy et al. (Citation2002) as disruption. Furthermore, repetitive questioning and requesting were observed as hindering learning which is in line with the findings of the study conducted by Travis and Geiger (Citation2010) who observed this as “self-talk and echolalia”. The teacher also confronted the challenge of conveying messages through body language. Other researchers (Alshurman & Alsreaa, Citation2015; Reed et al., Citation2007) also refer to this as a challenge in educating ASD children. Besides, high and low moods were quite evident in one of the children’s routine which can be attributed to autism spectrum disorder and as a featuring characteristic of this group of children (De-la-iglesia & Olivar, Citation2015). Similarly, this can relate to the fact that such children desire predictable patterns. Thus, the teachers are advised to set up and build routine activities and also ask parents to provide routine similar patterns of activities to prevent disorganization (Nason, Citation2014). Finally, several sensory complications including proprioceptive and vestibular problems were observable during training sessions. This was demonstrated through pushing themselves against the table and chairs and hitting against the walls and refraining from settling in the chair. These kinds of sensory problems are known to be characteristic features of these children (Ghanavati et al., Citation2013) and awareness on these issues can help instructors including the English teachers to exert more tolerance instructing this group of students.

8. Conclusion

The findings of the study revealed that PECS can be an effective system in early stages of language teaching to teach English vocabulary and simple conversational chunks. Kaduk (Citation2017) also maintains that this system can be efficient in early stages of communication in the first language. Using PECS can enhance communication abilities as well as understanding communication functions (Flippin et al., Citation2010). However, as far as foreign language teaching is concerned, PECS has been recommended as a system to teach English as a foreign language (Ganz et al., Citation2012). While using PECS can reinforce verbal speech in first language (Bondy & Frost, 2001) and improve functional communication skills (Tien, Citation2008), the findings of this study also suggest its promising effects on foreign language learning in simple levels. As English is an international language and also recently known as a Lingua Franca (Mishan & Timmis, Citation2015), the findings of the current study can be employed in different contexts where English has to be taught specially as a foreign language.

Based on the findings of the study and because PECS proved to be generally an effective augmentative system which had a functional effect, it is recommended that English teachers can get some training to get familiar with PECS and to employ it at the early stages of foreign language teaching (here English) specially to start with the vocabulary and also for the improvement of simple conversational chunks of the language. As far as the materials for teaching are concerned teachers are recommended to use realia as well as flash cards especially for teaching toys and animals. Teachers also need to be aware that reviewing and recycling has to be an indispensable part of their teaching especially throughout the later sessions when the bulk of the vocabulary increases in number. Despite the heterogeneity among children with autism, there are common features among children with autism at the international level including better visual perception and interest to circumscribed or favourite objects and realia (Sasson & Touchstone, Citation2014). Thus, these outcomes can be useful for children with autism having these features.

Relying on the second objective of the study which was the identification of the problematic areas and issues, the analyses of the video based observation conducted by one of the researchers and a rater (a PhD holder in occupational therapy) suggest that English teachers may encounter some challenges while using PECS including lack of cooperation in phase 2, lack of attention and cooperation in mid-intervention, sense problems such as proprioceptive and vestibular, high and low moods, and drowsiness. However, these same behavioural and sensing problems may also occur in teaching communication skills in the first language. Thus, to employ PECS to teach a foreign language, English teachers have to be aware of the stereotypical behaviours of this group of children, which is common among them irrespective of their nationalities, to be able to tackle successfully with these possible challenges.

While the number of students with ASD who wish to study foreign languages is increasing which has led to teachers concerns (Wire, Citation2005). The main reason of this concern is that students with autism need special training and they are not the same as other students. The effects of PECS in this study will guide this group of students in seeking effective ways to follow foreign language learning. The increasing number of students with autism who seek to learn foreign languages also invokes teachers’ attention and concern to look for alternatives to be employed. Syllabus designers as well as curriculum developers can also use the findings of the present study to decide on what to include and how to present materials if the teaching of a foreign language is concerned.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zahra Zohoorian

ZZ and MZ are assistant professors at the English department of the Islamic Azad University of Mashhad. Their fields of interest for research are mainly concerned with language education. NMS is also an assistant professor and the dean of the Department of Occupational Therapy of the Medical University of Mashhad. He is involved in research on education and the rehabilitation of children with special needs including children with autism. The authors are interested in investigating the effectiveness of different teaching methodologies on learners with and without special needs including children with autism. The number of children with autism is increasing worldwide and they also need to be provided with equal chances for learning as well as education. Hence, language education is not an exception. Accordingly, the present paper includes the description of an experiment conducted on children with autism and their vocabulary learning using Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS).

References

- Alemi, M., Meghdari, A., Basiri, N. M., & Taheri, A. (2015). The effect of applying humanoid robots as teacher assistants to help Iranian autistic pupils learn English as a foreign language. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Social Robotics (pp. 1–16).

- Alshurman, W., & Alsreaa, I. (2015). The efficiency of peer teaching of developing non- verbal communication to children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Journal of Education and Practice, 6(29), 33–38.

- Baker, S. (2007). The picture exchange communication system. In Approaches to autism (pp. 51). The national autism society.

- Bondy, A., & Frost, L. (2011). A picture’s worth: PECS and other visual communication strategies in autism. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 34(2), 163–166.

- Bowman, M. D. (1994). Using video in research. Scottish Council for Research in Education.

- Cardon, T. A., & Azuma, T. (2011). Deciphering single-subject research design and autism spectrum disorders. The ASHA Leader, 16(7), online–only. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1044/leader.FTR4.16072011.np

- Castillo, C. S. V., & Sanchez, D. F. M. (2016). Strategies to teach English as a foreign language to autistic children at a basic level at Saint Mary school [Bachelor’s thesis]. Universidad Centro Americana. htttp://repositorio.uca.edu.ni/4501/1/UCANI4960.Pdf

- Charlop-christy, M. H., Le, M. C. L., LeBlanc, L. A., & Kellet, K. (2002). Using the picture exchange communication system (PECS) with children with autism: Assessment of pecs acquisition, speech, social-communicative behaviour, and problem behaviour. Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis, 35(3), 213–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2002.35-213

- Colton, D., & Covert, R. W. (2007). Designing and constructing instruments for social research and evaluation. John Wiley & Sons.

- Davis, T. N., Lancaster, H. S., & Camarata, S. (2016). Expressive and receptive vocabulary learning in children with diverse disability typologies. Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 62(2), 77–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1179/2047387715Y.0000000010

- De-la-iglesia, M., & Olivar, J. S. (2015). Risk factors for depression in children and adolescents with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. The Scientific World Journal, 127853, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/127853

- Dyrbjerg, P., Vedel, M., & Pedersen, L. (2007). Everyday education: Visual support for children with autism. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Elder, J. H., Seung, H., & Siddiqui, S. (2006). Intervention outcomes of a bilingual child with autism. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 14(1), 53–63.

- Engel, R. J., & Schutt, R. K. (2017). The practice of research in social work. Sage Publication.

- Flippin, M., Reszka, S., & Watson, L. R. (2010). Effectiveness of the picture exchange communication system (PECS) on communication and speech for children with autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19(2), 178–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2010/09-0022)

- Frea, W. D., Arnold, C. L., & Vittimberga, G. L. (2001). A demonstration of the effects of augmentative communication on the extreme aggressive behaviour of a child with autism within an integrated preschool setting. Journal of Positive Behaviour Interventions, 3(4), 194–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/109830070100300401

- Frost, L. (2002). The picture exchange communication system. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education, 9(2), 13–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1044/lle9.2.13

- Ganz, J. B., & Simpson, R. L. (2004). Effects on communicative requesting and speech development of the picture exchange communication system in children with characteristics of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(4), 395–409. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000037416.59095.d7

- Ganz, J. B., Simpson, R. L., & Lund, E. M. (2012). The picture exchange communication system (PECS): A promising method for improving communication skills of learners with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 47(2), 176–186.

- Gast, D. L., & Ledford, J. R. (Eds.) (2014). Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioural sciences. Routledge.

- Gay, L. R., & Airasian. (2003). Educational research competencies for analysis and applications (7th ed.). Prentice Hal.

- Ghanavati, E., Zarbakhsh, M., & Haghgoo, H. A. (2013). Effects of vestibular and tactile stimulation on behavioural disorders due to sensory processing deficiency in 3-13 years old Iranian autistic children. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal, 11, 52–57.

- Granpeesheh, D., Torbox, J., Najdowski, A. C., & Kornack, J. (2014). Evidence-based treatment for children with autism. Elsevier.

- Greenberg, A. L., Tomaino, M. A. E., & Charlop, M. H. (2012). Assessing generalization of the picture exchange communication system in children with autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24(6), 539–558. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-012-9288-y

- Hanna, L. (2001). Teaching young children with autistic spectrum disorders to learn. Tthe national autistic society.

- Hasan, A. A. (2020). Assessment of family knowledge toward their children with autism spectrum disorder at Al-Hilla City, Iraq. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology, 14(3), 1801.

- Jacobson, J. W., Mulick, J. A., Foxx, R. M., & Kryszak, E. (2016). History of fad, pseudoscientific, and dubious treatments in intellectual disabilities: From the 1800s to today. In M. Richard & J. A. Mulick (Eds.), Controversial therapies for autism and intellectual disabilities (pp. 45–70). Routledge.

- Jelínková, B. (2019). ICT as an enhancing tool of foreign language teaching children with autistic spectrum disorders. International Journal of Information and Communication Technologies in Education, 8(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2478/ijicte-2019-0004

- Jewitt, C. (2012). An introduction to using video for research. National center for research methods.

- Kaduk, L. (2017). The effectiveness of the picture exchange communication system for children who have autism. Culminating Projects in Special Education. 40. http://repository.stcloudstate.edu/sped_etds/40

- Khodaverdi, N., Ashayeri, H., & Maftoon, P. (2018). Teaching English as a foreign language to high-functioning autistic children. Neuropsychology Journal, 3(4), 39–54. http://clpsy.journals.pnu.ac.ir/article_4867_93592e693dc854d6a9d9a36e68ae8e27.pdf?lang=en

- Knoblauch, H., & Schnettler, B. (2012). Videography: Analysing video data as a ‘focused’ ethnographic and hermeneutical exercise. Qualitative Research, 12(3), 334–356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111436147

- Kravits, T. R., Kamps, D. M., Kemmerer, K., & Potucek, J. (2002). Brief report: Increasing communication skills for an elementary-aged student with autism using the picture exchange communication system. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(3), 225–230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015457931788

- Kuparinen, T. (2017). Perceptions of EFL learning and teaching by autistic students, their teachers and their school assistants [Master’s Thesis]. University of Jyväskylä. https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/55292/1/URN%3ANBN%3Afi%3Ajyu-201709073681.pdf

- Magiati, I., & Howlin, P. (2003). A pilot evaluation study of the picture exchange communication system (PECS) for children with autistic spectrum disorders. Autism, 7(3), 297–320. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613030073006

- Mishan, F., & Timmis, I. (2015). Materials development for TESOL. Edinburgh University Press.

- Moghadam, A. S., Karami, M., & Dehbozorgi, Z. (2012). Second language learning in autistic children compared with typically developing children: “procedures and difficulties”. Proceedings of the First Conference on Language Learning & Teaching: An Interdisciplinary Approach (pp. 1–13), October 31–32, 2012, Ferdowsi University.

- Nason, B. (2014). The autism discussion page on the core challenges of autism. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Padmadewi, N. N., & Artini, L. P. (2017). Teaching English to a student with autism spectrum disorder in regular classroom in Indonesia. International Journal of Instruction, 10(3), 159–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2017.10311a

- Petersen, J. (2010). Lexical skills in bilingual children with autism spectrum disorders [master’s thesis]. https://circle.ubc.ca/handle/2429/23471

- Reed, C. L., Beall, P. M., Stone, V. E., Kopelioff, L., Pulham, D. J., & Hepburn, S. L. (2007). Brief report: Perception of body posture, what individuals with autism spectrum disorder might be missing. Journal of Autism Developmental Disorder, 37(8), 1576–1584. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0220-0

- Reppond, J. S. (2015). English language learners on the autism spectrum: Identifying gaps in learning. Hamline University. http://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/cgi/viewcontent.gi?article=1241&context=hse_all

- Rezvani, M. (2018). Teaching English to students with autism: Montessori-oriented versus audio-lingual method. International Journal of Science, Engineering and Management, 3(2), 19–23. https://www.technoarete.org/common_abstract/pdf/IJSEM/v5/i2/Ext_41830.pdf

- Rice, C. E., Rosanoff, M., Dawson, G., Durkin, M. S., Croen, L. A., Singer, A., & Yeargin-Allsopp, M. (2012). Evaluating changes in the prevalence of the autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Public Health Reviews, 34(2), 17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391685

- Romadlon, F. N. (2017). Speech therapy to promote English for autistic students. Proceedings of the 5th International seminar on English language and teaching (pp. 56–61), May 9–10,2017, Universitas Negeri Padang. ejournal.unp.ac.id/index.php/selt/article/download/7984/6087

- Ryan, L., Bondy, A., & Finnegan, C. (1990, May). Please don’t point! Interactive augmentative communication systems for young children. Paper presented at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

- Sasson, N. J., & Touchstone, E. W. (2014). Visual attention to competing social and object images by preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(3), 584–592. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1910-z

- Schopler, E., Mesibov, G., & Hearsey, K. (1995). Structured teaching in the TEACCH system. In E. Schopler & G. Mesibov (Eds.), Learning and cognition in autism (pp. 243–267). Plenum.

- Schopler, E., Reichler, R., & DeVellis, R. (1988). Toward objective classification of childhood autism: Childhood autism rating scale (CARS). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 10(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02408436

- Schwartz, I. S., Garfinkle, A. N., & Bauer, J. (1998). The picture exchange communication system: Communicative outcomes for young children with disabilities. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 18(3), 144–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/027112149801800305

- Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (1998). Summarizing single-subject research: Issues and applications. Behaviour Modification, 22(3), 221–242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/01454455980223001

- Scruggs, T. E., Mastropieri, M. A., & Casto, G. (1987). The quantitative synthesis of single-subject research: Methodology and validation. Remedial and Special Education, 8(2), 24–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258700800206

- Szymkowiak, C. (2013). Using effective strategies for the elementary English language learner with autism spectrum disorder: A curriculum project. State University of New York.

- Tien, K. (2008). Effectiveness of the picture exchange communication system as a functional communication intervention for individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A practice-based research. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 43(1), 61–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23879744?seq=1

- Travis, J., & Geiger, M. (2010). The effectiveness of the picture exchange communication system (PECS) for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A South African pilot study. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 26(1), 39–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659009349971

- Welch, A. (2010). The effects of picture exchange communication system training on the communication behaviours of young children with autism or severe language disabilities [Master’s thesis]. Ohio State University. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/

- Wire, V. (2005). Autistic spectrum disorders and learning foreign languages. Support for Learning, 20(3), 123–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0268-2141.2005.00375.x