Abstract

This study aims at examining the relationship between entrepreneurship education, culture, and the entrepreneurial intention of college students as well as investigating the moderating role of the entrepreneurial mindset. Structural equation modeling was adopted to gain a detailed understanding of the influence among variables. This study involved approximately 376 university students who enrolled in the entrepreneurship course. The findings indicate that the entrepreneurial mindset has successfully accelerated the entrepreneurial intention of university students. Partially, entrepreneurial culture has an impact on entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention. Additionally, both entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial culture have a robust correlation with students’ entrepreneurial mindset. Contrary to expectations, this study did not find a significant difference between entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial intention. These results imply that the university has positioned itself as a critical intervention in encouraging students’ intention through an effective entrepreneurship education model.

Public interest statement

Enhancing the number of entrepreneurs has been a global challenge. With its vast population and its unique cultures, Indonesia has a great opportunity to accelerate new business creations from university graduates. This study involves entrepreneurship education, cultures, and mindset in promoting students’ entrepreneurial intention. The findings are useful for government and policy research in crafting an effective entrepreneurship education for students as well as integrating cultures and mindset in fostering the intention of being entrepreneurs.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship education has received considerable critical attention in the last decade (Santos et al., Citation2019; Sarooghi et al., Citation2019). The underlying rationale is that entrepreneurship can diminish social and economic issues such as unemployment, poverty, and living standards. Evidence also suggests that entrepreneurship can escalate the community’s income and welfare through new job creations (Linan & Fayolle, Citation2015). Additionally, Naminse et al. (Citation2018) revealed that entrepreneurship has a relationship with poverty alleviation as well as regional development and economic growth. Considering the importance of entrepreneurship, both developed and developing countries have responded by campaigning to enhance entrepreneurs in their countries (Klofsten et al., Citation2019).

Enhancing the number of entrepreneurs has been a global challenge. In the Indonesian context, the government has responded to this matter by optimizing of entrepreneurship education in all levels of education. For example, in higher education, several programs have been initiated, including the integrated work learning program, the Indonesian student business competition program, to increase students’ entrepreneurial intentions. The revitalization of entrepreneurship education in higher education also intends to equip students with skills, character, and mentality that is expected to lead a stimulation in intention to become entrepreneurs (Hidayati & Satmaka, Citation2018).

Several prior studies have shown that the entrepreneurial intention of students increases after participating in entrepreneurship education and engaging in business classes (Anwar & Saleem, Citation2019; Boldureanu et al., Citation2020). Entrepreneurship education enables students to progress based on innovation and future career directions (Ratten & Jones, Citation2020). This implies that students have alternative careers choice as entrepreneurs on a small business scale to a well-established company. Entrepreneurial education also allows students to hold skills and management training that enhances entrepreneurial knowledge, encourages entrepreneurial mindset, improves management understanding and entrepreneurial intention (Hahn et al., Citation2017).

In addition to entrepreneurship education, Solesvik et al. (Citation2013) and Pfeifer et al. (Citation2016) pointed out that the intention of starting a business is linked with mindset. The entrepreneurial mindset that is conducive to every action can lead to cognitive diversion and enhance the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and activities (Mathisen & Arnulf, Citation2013). Additionally, an entrepreneurial mindset is needed for students to address changes and construct creative thinking dealing with new economic circumstances. On the other hand, Jabeen et al. (Citation2017) demonstrated the role of culture for entrepreneurship. A cultural element can drive individual behavior, including decision-making and career choice as entrepreneurs. Investing in entrepreneurship has a long-term positive influence on both economic development and nation contention, so providing an entrepreneurial culture for young people is essential.

The study provides two primary contributions. First, this study offers an insight into entrepreneurial studies by elaborating on all the crucial components, including culture, education, mindset, and intention, elements that are missing in the prior studies. Research on the topic has been mainly confined to a limited examination of entrepreneurship education and intention. However, few scholars have provided any systematic study into the cultural, mindset, and entrepreneurial intentions (e.g., Ashourizadeh et al., Citation2014; Bogatyreva et al., Citation2019; Westhead & Solesvik, Citation2016). Second, focusing the study on Indonesia provides a unique perspective given the vast size of populations. It faces a crisis as its picturesque cultures that are well-known for collective work, togetherness, equality, and respect lack the necessary number of entrepreneurs to promote its business opportunities. The data from the Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index in 2017 showed Indonesia posits the rank 94 of the total 137 countries surveyed and left behind other ASEAN countries, such as Singapore (27), Malaysia (58), Thailand (71), and Philipines (84).

2. Literature review

2.1. Entrepreneurial culture

The development of entrepreneurial culture for students has become a great matter of concern in entrepreneurship study. Entrepreneurial culture is defined as the values, behaviors, and skills of communities or individuals which engage creativity and innovativeness (Danish et al., Citation2019). Entrepreneurial culture in educational institutions plays a role in promoting students to improve the confidence level and creativity (Bogatyreva et al., Citation2019). It also incorporates students’ awareness of the opportunities of being entrepreneurs instead of being workers in the future (Arranz et al., Citation2019). Previous studies and empirical evidence have predominantly supported that entrepreneurial culture can stimulate the intention of being entrepreneurs (Chukwuma-Nwuba, Citation2018; Fragoso et al., Citation2020; Sesen & Pruett, Citation2014).

The growing body of literature argues that entrepreneurial culture can shape students’ mindset on entrepreneurship (Dewi et al., Citation2019; Yusof et al., Citation2017). To explain this relation, the social cognitive theory (SCT) is performed in this study. The SCT shows the interactions between cognitive variables, environmental factors, culture, and individuals’ behavior (Bandura, Citation2001). The entrepreneurial mindset is one type of personal cognitive variable influenced by entrepreneurial culture, entrepreneurship education, and extra-curricular activities (Cui et al., Citation2019). Several prior studies show that an entrepreneurial mindset can be influenced and learned through the individual’s initial knowledge and interactions with today’s culture and environment (Mathisen & Arnulf, Citation2013). Similarly, Shepherd et al. (Citation2010); Jabeen et al. (Citation2017) remarks that entrepreneurial culture in an institution actively encouraged them to learn and improve their entrepreneurial knowledge and mindset.

In addition to promoting entrepreneurial mindset, culture in communities or educational organization has also linked with entrepreneurship education. Education is a public medium for realizing the embedding of fundamental and objective to immerse entrepreneurial education throughout the curriculum at all education grades (Nowinski et al., Citation2019). A prior study by Blenker et al. (Citation2012) indicates that there has been a remarkable increase in the number of entrepreneurship courses which support a cultural shifting in Western countries. Supporting this fact, policymakers have also provided an academic focus to enhance cultural involvement in the educational organization (Khalid et al., Citation2019). One aspect of this cultural influence looks for the number of educational institutions that teach entrepreneurship courses (Farny et al., Citation2016). The trial hegemony of starting a new business needs to be critically examined. The entrepreneurial culture resonates with a heroic entrepreneurial outlook so that the industrial-based and modern business structures are maintained (Sesen & Pruett, Citation2014). Therefore, the hypotheses are proposed as follows:

H1: Entrepreneurial culture positively impacts entrepreneurial intention

H2: Entrepreneurial culture positively impacts entrepreneurial mindset

H3: Entrepreneurial culture positively impacts entrepreneurial education

2.2. Entrepreneurship education

Entrepreneurship education has become a central topic of discussion on the economy, and it has gained attention among scholars in the entrepreneurial field. Entrepreneurship education is the entire educational activity with the ultimate goal of developing students’ entrepreneurial intentions (Li & Wu, Citation2019). Entrepreneurship education enables students to enhance awareness and skills of entrepreneurship and provides students with alternative careers as entrepreneurs (Ratten & Jones, Citation2020; Jena, 2020). Additionally, Viaz and Rivera-Cruz (Citation2020) provides different interpretations of entrepreneurship education concept as a teaching and learning activities that can determine business attitudes such as autonomy, creativity, innovation or risk taking, and business creation. Meanwhile, Wu and Wu (Citation2008) inform that entrepreneurship education can enhance students’ managerial abilities to support business activities. The model entrepreneurship education in university equips students with skills to pursue entrepreneurial careers, especially in the entrepreneurship lecturing material. This implicates that entrepreneurial education has a robust correlation with entrepreneurial intention (Hassi, Citation2016; Khalifa & Dhiaf, Citation2016).

Entrepreneurship education is an important and strategic dimension to enhance competitiveness, and it can be adopted in an integrated manner with educational activities in universities (Fernandez-Serrano et al., Citation2018). Besides, some studies believe that entrepreneurial education can stimulate students’ mindsets on entrepreneurship (Daniel, Citation2016; Solesvik et al., Citation2013; Zhang et al., Citation2020). Entrepreneurial mindset is defined as ability to feel, think, and act about opportunities rather than obstacles (Jabeen et al., Citation2017). Additionally, Ridley et al. (Citation2017) explains that the entrepreneurial mindset covers an individual’s ability to response decisions under uncertainty situation. The learning approach and activities engaged in the classroom are more likely to have a direct influence on enhancing college students’ cognitive ability, which will allow them to positively participate in entrepreneurial activities (Solesvik et al., Citation2013). It also enables students to grow as learners and gain vital experience. The educational learning process consists of such activities as ethnographic user studies, brainstorming approaches, cooperation activities, and business enhancement practices that authorize university students to engage their capability to seek out creative and critical solutions based on their learning experiences (Dehghani et al., Citation2018). These practical aspects are critical in enhancing an entrepreneurial mindset (Bogatyreva et al., Citation2019). Therefore, this research provides hypotheses as follow:

H4: Entrepreneurial education positively impacts entrepreneurial mindset

H5: Entrepreneurial education positively impacts entrepreneurial intention

2.3. The mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset

Several preliminary studies have demonstrated the belief of entrepreneurial mindset as a certain of mind that drives individuals’ behavior toward culture and output related to entrepreneurship (Akmaliah et al., Citation2016; Linan & Fayolle, Citation2015). Those researchers note that the entrepreneurial mindset has an acquaintance with how individuals thinking. Shepherd et al. (Citation2010) supports this perspective and confirms that the entrepreneurial mindset enables possible insights into some outcomes needed for entrepreneurial studies. To explain how the entrepreneurial mindset’s role mediates entrepreneurial culture and entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial intention, we refer to the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) by Bandura (2001). In detail, SCT proposes the interaction between cognitive variables, environmental factors including culture, and individual behavior (Bandura, 2001).

The most recent study by Cui et al. (Citation2019) shows that SCT provides a coherent framework for understanding the role of determinant factors in holistic entrepreneurship education, particularly from a cognitive psychology perspective. Previously, Winkler and Case (Citation2014) applied SCT theory to the context of entrepreneurship education and developed a dynamic framework related to the impact of entrepreneurship education that contributes to investigate how entrepreneurial education factors can affect student cognition and subsequent entrepreneurial intentions. Winkler (2014) and Cui et al. (Citation2019) further identify cultural, curriculum, and non-academic factors such as learning activities or experiences that influence cognitive factors such as entrepreneurial mindset, entrepreneurial inspiration, motivation, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intentions. In summary, entrepreneurial culture and entrepreneurial education lead to mindset shifts and emotional changes (Gibb, Citation2002; Haynie et al., Citation2010), which ultimately affect student intentions. Based on those descriptions, this study contributes to the framework of Winkler (Citation2014) and Cui et al. (Citation2019) by emphasizing the entrepreneurial mindset variable as a new type of cognitive variable. Referring to the SCT theory, entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial culture affect the entrepreneurial mindset and students’ entrepreneurial intention. Thus, this research proposes the following hypotheses:

H6: Entrepreneurial mindset positively influences entrepreneurial intention

H7: Entrepreneurial mindset mediates the influence of entrepreneurial culture and entrepreneurial intention

3. Method

3.1. Research design

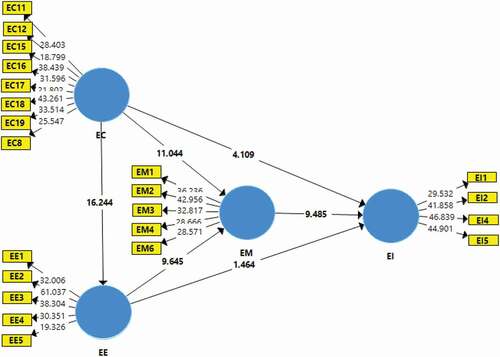

This survey model with a quantitative approach was adopted to comprehend how entrepreneurship education, culture, and mindset explain college students’ entrepreneurial intention. The study was carried out in Malang, East Java of Indonesia is reasonable since Malang is the biggest educational city in Indonesia that consists of more than 50 universities throughout the city/municipality. As depicted in , the relationship between variables in this study waswas performed from previous studies’ empirical evidence and literature.

3.2. Participant and data collection

A convenience sample was applied in this research that was frequently adopted in the entrepreneurship study. To ensure privacy and ethical issue, the respondents in this work were informed of their anonymity, and the Institutional Research Committee approved the ethical rules of Universitas Negeri Malang. We provided 430 questionnaires using the Google forms platform, which was distributed via email and WhatsApp. After removing approximately 12.55 percent of incomplete questionnaires, 376 responses from volunteers could be further used for data analysis (see for detailed respondents).

Table 1. The demographic participants

informs the details of demographic respondents in this survey. Overall, the study’s participants were dominated by male students with a total of almost double than females ranging between the study year of 2015 and 2019. Most respondents came from the class year of 2017, with a percentage of approximately 65 percent with an almost equal percentage in terms of the subject area. Lastly, the student’s parent of this study was dominated by entrepreneurs with about 65 percent, followed by farmers as the main job.

3.3. Measurement and data analysis

To estimate respondent reactions to entrepreneurial intention (EI), we used six instruments developed by Krueger et al. (Citation2000); Linan and Chen (Citation2009), whilst entrepreneurial mindset (EM) was proxied by seven indicators from Mathisen and Arnulf (Citation2013). For entrepreneurial culture (EC), we adapted 19 indicators from MacKenzie et al. (Citation2011); Ireland et al. (Citation2009). Lastly, to calculate entrepreneurship education (EE), we engaged six indicators from Denanyoh et al. (Citation2015). All survey questions utilized a five-point Likert scale. After calculating each variable, we regressed using Structural Equation Modelling Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS) with SmartPLS version 3.0. This study adopted Hair et al. (Citation2014) by providing a five-stage structural model assessment procedure, including assessing the structural model for collinearity issue, path coefficients, R-square (R2), the effect size (f2), and the predictive relevance (Q2).

4. Results and discussion

4.1. The outer and inner assessment model

The first process of this was to conduct a predictive model evaluation with two assessments, including the outer and inner evaluation models. For the outer model evaluation, this study followed four stages by Hair et al. (Citation2013), consisting of convergent validity, discriminant validity, composite reliability, and construct reliability. informs the details of the outer model measurement. From the table, it can be seen that the calculation of convergent validity for these variables (EE, EC, EM, EI) has a loading factor between 0.719 to 0.876, which meaning that variables satisfied the convergent validity (loading factor > 0.70) (Chin, Citation2009; Hair et al., Citation2013). The table also illustrates that the variables involved in this study have AVE higher than 0.5, implicating that the variables confirmed the discriminant validity. Accordingly, the variables of EE, EC, EM, and EI have the CR value of 0.900, 0.938, 0.919, and 0.919 (> 0.70), which implies that those variables met the composite reliability criteria (Chin, Citation2009; Hair et al., Citation2013).

Table 2. Results of measurement (outer) model

The discriminant calculation is provided in . From the table, it can be illustrated that the value of cross-loading for EE, EM, and EI is upper 0.70, which indicates that the variables satisfied the convergent validity criteria (Chin, Citation2009; Hair et al., Citation2013).

Table 3. Discriminant validity

Apart from using the Fornell-Larcker (Citation1981) model and cross-loading (Chin, Citation2009), we also applied a heterotrait-monotrait ratio procedure by Henseler et al. (Citation2014) to estimate the discriminant validity. The test results for each variable (see ) showed that the heterotrait-monotrait ratio is less than 0.90, which implies that the variables confirmed the discriminant validity (Henseler et al., Citation2014).

Table 4. Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio

4.2. The collinearity and R-square test

The collinearity test of this study was determined using the VIF score, which ranges from 1.62 to 3.67 (< 5.00). This result showed that the model satisfied the collinearity criteria and valid for further analysis. Accordingly, the R-square (R2) test in this study followed the category from Chin (Citation2009), which has the category of 0.67 for substantial, 0.33 for moderate, and 0.19 for weak criteria. From the R2 test, it can be concluded that EC has a value of 0.480, meaning that 48 percent variable EC can be moderately explained by the variable of EE. Additionally, the EM was substantially provided by EE and EC with a score of 0.718, while the variable of EI was substantially explained by EE, EC, and EM with a percentage of 71.9 percent.

4.3. The size effect test (f2)

The size effect test (f2) aims to calculate the extent of the correlation of the latent predictor variable (exogenous latent variable) on the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2013). The f2 test consists of three main classifications: small (0.02), medium (0.15), and large effect (0.35). The test results show that the size effect of EE, EC toward EM were 0.937, which meaning that it has a large effect size. Additionally, the EE, EC, EM toward EI have a score of 0.423, which shows a large effect size.

4.4. Predictive relevant test (Q2)

The Q-square (Q2) predictive test is intended to examine how the observed score is provided by the model and plays a role as parameter estimation. This study adopted the criteria from Hair et al. (Citation2013) which the value of Q2 > 0 shows that the model is having predictive relevance value and vice versa. Based on the calculation, it can be known that the Q2 of each variable was higher than 0, thus meaning that the model satisfied predictive relevance criteria.

4.5. The coefficient path analysis

The path analysis aims at evaluating the constructed model of this research. For the SEM-PLS, the bootstrapping stages have been initiated to assess the score of t-statistic and t-value. and provide the information about the hypothesis testing between variables. From seven hypotheses testing, we found that six hypotheses were accepted, while the fifth hypothesis was rejected with a p-value of 0.131.

Table 5. The summary of testing results

5. Discussion

The finding of this work addresses the seventh hypothesis proposed. The first hypothesis in this study sought to determine the connectivity between entrepreneurial culture and students’ entrepreneurial intention. This study confirmed that entrepreneurial culture can explain students’ intention of being entrepreneurs. The fundamental rationale is that culture in an institution promoted students to learn and improve to be more confident. This implies that a good culture that has been provided in the college drives students to be more open-minded to receive new information and knowledge that needed for entrepreneurial activities. Additionally, the finding of this study notes that the university has successfully provided creative ideas to become entrepreneurs as an alternative career. Students also have been given the provision of knowledge about entrepreneurship that makes them capable and becomes an expert in the field of business. The result of this research supports several antecedent scholars by Ao and Liu (Citation2014), Sesen and Pruett (Citation2014), and Adekiya and Ibrahim (Citation2016).

In addition to the first hypothesis, it was forecasted that entrepreneurial culture has a positive impact on the entrepreneurial mindset. The finding of this study is in agreement with the social cognitive theory (SCT) by Bandura (2001), which revealed the interactions between cognitive variables, environmental factors, culture, and individual behavior. Referring to the social cognitive theory, an entrepreneurial mindset is one type of personal cognitive variable that is influenced by entrepreneurial culture, entrepreneurship education, in this case, curriculum and extra-curricular activities. Similarly, the finding supports some preliminary studies by Mathisen and Arnulf (Citation2013); Cui et al. (Citation2019), who remarked that the entrepreneurial mindset can be influenced and learned through the individual’s initial knowledge and interactions with today’s culture and circumstances. The results match with the observed in earlier studies by Shepherd et al. (Citation2010); Jabeen et al. (Citation2017), which mentioned that students who participated in this study think that entrepreneurial culture in an institution actively encouraged them to learn and improve their entrepreneurial knowledge.

With respect to the first and second research hypothesis, it was found that there is a positive influence between entrepreneurial culture and entrepreneurship education. A possible explanation for this finding is that entrepreneurial culture drives social legitimation and creates a circumstance that supports teaching and learning in entrepreneurship. Additionally, entrepreneurial culture, with its value, has affected the psychological attitude that relevant to entrepreneurship education. A conducive culture in relation to entrepreneurship in the college promotes students to be more open-minded to receive new information and knowledge. This study found that the university enables students to provide creative ideas to become entrepreneurs as an alternative career and the provision of knowledge about entrepreneurship that makes them capable in the field of business. Entrepreneurship through education is more structured and directed in learning due to its supporting curriculum has been prepared. This finding supports several antecedent scholars by Ao and Liu (Citation2014), Sesen and Pruett (Citation2014), and Adekiya and Ibrahim (Citation2016), which confirmed this relationship.

The fourth objective of the study was to identify the impact of entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial mindset. The finding of this work confirmed that entrepreneurial education can determine students’ mindset related to entrepreneurship. The result of this work reinforces preliminary findings of Sowmya et al. (Citation2010); Akmaliah et al. (Citation2016), Ridley et al. (Citation2017), and Wardana et al. (Citation2020), which demonstrated this relation relationship. An underlying reason for this result is that the pedagogical approach in education has a positive impact on students’ cognitive ability to register in the proposed activities in class and has created a favorable atmosphere for learning, with students playing an active role in gaining experience from their activities. This finding is in agreement with social cognitive theory by Bandura (2001), which revealed that education allows an individual’s cognitive from environmental factors and behavior that can lead to mindset. Indeed, Cui et al. (Citation2019) also argued that social cognitive theory provides a coherent framework for understanding entrepreneurship education holistically, particularly from a cognitive psychology point of view.

The next hypothesis in this study was intended to determine the connectivity between entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial intention. Surprisingly, in this work, entrepreneurship education failed in explaining Indonesian students’ intention of being entrepreneurs. The result is in contrast with the majority of works by Barnir, Watson, and Hutchins (Citation2011); Martin, Mcnally, and Kay (Citation2013); Wibowo et al. (Citation2018); Wardana et al. (Citation2020), which remarked that entrepreneurship education can drive students’ entrepreneurial intention. A possible explanation for this result may be the lack of entrepreneurship education in inspiring and growing students’ motivation to choose entrepreneurs as a career choice. The fact that entrepreneurship education model needs to elaborate on more practical experiences and training instead of theoretical in the classroom. An interesting result in our study can be an entry point and valuable suggestion for the college and the Indonesian government to involve and elaborate on more practical experience, workshop, training, field studies instead of focusing on the entrepreneurial theories.

The following hypothesis is that there is a positive impact on the entrepreneurial mindset on entrepreneurial intention. The result confirmed and supported prior scholars by Pfeifer et al. (Citation2016); Ayalew and Zeleke (Citation2018). The basic explanation for this finding is that the characteristics of an entrepreneurial mindset, such as awareness of opportunities, risk tendencies, tolerance for ambiguity, and optimism in doing business, have been perceived appropriately by university students that leads to intention. Similarly, Cui et al. (Citation2019) emphasized that the entrepreneurial intention is formed by one of them is the entrepreneurial mindset. This implicates that the campus with conducive entrepreneurial activities inspires and shapes the mindset of students to become entrepreneurs. In addition, the campus also supports various student entrepreneur product competitions and facilitates the birth of new entrepreneurs from students in college. Indeed, this study is robustly approved the prior studies by Jabeen et al. (Citation2017), Adekiya and Ibrahim (Citation2016), and Ao and Liu (Citation2014), which showed this connectivity.

Furthermore, entrepreneurial culture has a significant indirect effect on entrepreneurial intention through entrepreneurial mindset proven significant. The involvement of entrepreneurial education towards entrepreneurial intention is supporting by increasing students’ entrepreneurial mindset. The result of this work is in accord with recent studies by Ayalew and Zeleke (Citation2018), Solesvik et al. (Citation2013), Wach and Wojciechowski (Citation2016), Daniel (Citation2016), and Jabeen et al. (Citation2017) indicating a mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset. Referring to the social cognitive theory by Bandura (Citation2001), entrepreneurial mindset is a type of personal cognitive variable that is influenced and becomes the mediator of the next variable. In summary, entrepreneurial culture and entrepreneurial education lead to a mindset shifting and emotional changing (Gibb Citation2002; Haynie et al., Citation2010), which ultimately influence student intentions. Based on the preliminary descriptions, this study contributes to the framework of Winkler (2014) and Cui et al. (Citation2019) by emphasizing the entrepreneurial mindset variable as a new type of cognitive variable. Thus, referring to the social cognitive theory, entrepreneurial education and culture affects the entrepreneurial mindset and students’ entrepreneurial intention.

6. Conclusion

This study has discussed how the causality between entrepreneurship education, culture, and entrepreneurial intention as well as understanding the mediation role of an entrepreneurial mindset. The findings of this research, therefore, confirm that culture and mindset have a robust correlation with students’ entrepreneurial intention, while at the same time, entrepreneurial education surprisingly has no impact on student’s entrepreneurial intention. Additionally, both entrepreneurial education and culture play a significant role in accelerating students’ mindset on entrepreneurship. Lastly, this study indicates that an entrepreneurial mindset can explain the relationship between entrepreneurial education, entrepreneurial culture and students’ entrepreneurial intention in Indonesia.

This study has several practical implications primarily for students, lecturers, universities, and the government. For students, this study showed that entrepreneurial education and culture play a crucial role in preparing students for entrepreneurship. Therefore, students should think that entrepreneurial education has the same degree of importance as other subjects. For lecturers, the classroom’s learning process should elaborate on the cognitive aspect and inspire students to enhance their intention of being entrepreneurs. The entrepreneurial learning model classes should also involve successful entrepreneurs to share their experiences in doing business. This study also recommends that at the beginning of semesters, entrepreneurship lecturers focus on enhancing psychological characteristics, i.e., motivating to start up business, risk perception, behavioral control, willingness to do business, and prepare for entrepreneurship. Furthermore, in the following semester, an entrepreneurial practice should be reproduced based on the development of students’ creative ideas in the classroom.

For the university, this study provides valuable input that the entrepreneurship curriculum needs to be updated to be relevant to technological advances and increase students’ entrepreneurial intentions further. Lastly, for the government, this research shows that the socialization of the government’s siding with young entrepreneurs must continue to be carried out and make it easier for various business establishment permits. The government also needs visiting campuses to disseminate various policies supporting young entrepreneurs, such as providing a conducive business climate, access to accessible funding sources, and conducting continuous entrepreneurship education.

The main limitation is that this work did not apply a cross-sectional design and triangulation model for data saturation, which enables authors to understand the relationship between variables and examine the moderating variables. This study used an undergraduate student as samples, which categorized as a homogeneous group. Therefore, the generalizability of this finding to the broader population remains questionable. For this reason, we suggest that future scholarships in the field may concern a more significant population by elaborating both private and state universities to acquire more heterogeneous subjects.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Saparuddin Mukhtar

Saparuddin Mukhtar is an associate professor specializing in economics, small-medium enterprises, and entrepreneurship at the Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia. Ludi Wishnu Wardana is an associate professor at Universitas Negeri Malang, concerning entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial education. Agus Wibowo is an assistant professor of entrepreneurship at the Faculty of Economics Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia. Bagus Shandy Narmaditya is a lecturer at the Economic Education Program, Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia.

References

- Adekiya, A. A., & Ibrahim, F. (2016). Entrepreneurship intention among students. The antecedent role of culture and entrepreneurship training and development. International Journal of Management Education, 14(2), 116–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2016.03.001

- Akmaliah, Z., Pihie, L., & Arivayagan, K. (2016). Predictors of Entrepreneurial Mindset among University Students. International Journal of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education, 3(7), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0307001

- Anwar, I., & Saleem, I. (2019). Exploring entrepreneurial characteristics among university students: An evidence from India. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(3), 282–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-07-2018-0044

- Ao, J., & Liu, Z. (2014). What impact entrepreneurial intention? Cultural, environmental, and educational factors. Journal of Management Analytics, 1(3), 224–239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23270012.2014.994232

- Arranz, N., Arroyabe, M. F., & Fdez. De Arroyabe, J. C. (2019). Entrepreneurial intention and obstacles of undergraduate students: The case of the universities of Andalusia. Studies in Higher Education, 44(11), 2011–2024. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1486812

- Ashourizadeh, S., Chavoushi, Z. H., & Schøtt, T. (2014). People’s confidence in innovation: A component of the entrepreneurial mindset, embedded in gender and culture, affecting entrepreneurial intention. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 23(1–2), 235–251. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2014.065310

- Ayalew, M. M., & Zeleke, S. A. (2018). Modeling the impact of entrepreneurial attitude on self-employment intention among engineering students in Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 7(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-018-0088-1

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media psychology,3(3), 265–299.

- Barnir, A., Watson, W. E., & Hutchins, H. M. (2011). Mediation and moderated mediation in the relationship among role models, self‐efficacy, entrepreneurial career intention, and gender. Journal of Applied Social Psychology,41(2), 270–297.

- Blenker, P., Frederiksen, S. H., Korsgaard, S., Müller, S., Neergaard, H., & Thrane, C. (2012). Entrepreneurship as everyday practice: towards a personalized pedagogy of enterprise education. Industry and Higher Education,26(6), 417–430.

- Bogatyreva, K., Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T. S., Osiyevskyy, O., & Shirokova, G. (2019). When do entrepreneurial intentions lead to actions? The role of national culture. Journal of Business Research, 96, 309–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.034

- Boldureanu, G., Ionescu, A. M., Bercu, A. M., Bedrule-Grigoruță, M. V., & Boldureanu, D. (2020). Entrepreneurship education through successful entrepreneurial models in higher education institutions. Sustainability, 12(3), 1–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031267

- Chin, W. W. (2009). How to write up and report PLS analyses. Handbook of Partial Least Squares, 655–690. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-32827-8_29

- Chukwuma-Nwuba, E. O. (2018). The influence of culture on entrepreneurial intentions: A Nigerian university graduates’ perspective. Transnational Corporations Review, 10(3), 213–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19186444.2018.1507877

- Cui, J., Sun, J., & Bell, R. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial mindset of college students in China: The mediating role of inspiration and the role of educational attributes. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.04.001

- Daniel, A. D. (2016). Fostering an entrepreneurial mindset by using a design thinking approach in entrepreneurship education. Industry and Higher Education, 30(3), 215–223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422216653195

- Danish, R. Q., Asghar, J., Ahmad, Z., & Ali, H. F. (2019). Factors affecting “entrepreneurial culture”: The mediating role of creativity. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 8(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-019-0108-9

- Dehghani, M., Dehghani, M., Zali, M. R., & Zali, M. R. (2018). Analysis of entrepreneurial competency training in the curriculum of bachelor of physical education in universities in Iran. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1462423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1462423

- Denanyoh, R., Adjei, K., & Nyemekye, G. E. (2015). Factors that impact on entrepreneurial intention of tertiary students in Ghana. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 5(3), 19–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18533/ijbsr.v5i3.693

- Dewi, D. P., Nurfajar, A. A., & Dardiri, A. (2019, January). Creating entrepreneurship mindset based on culture and creative industry in challenges of the 21st century vocational education. In 2nd International Conference on Vocational Education and Training (ICOVET 2018) (pp. 67–70) Indonesia. Atlantis Press.

- Farny, S., Frederiksen, S. H., Hannibal, M., & Jones, S. (2016). A CULTure of entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development,28(7–8), 514–535.

- Fernandez-Serrano, J., Berbegal, V., Velasco, F., & Expósito, A. (2018). Efficient entrepreneurial culture: A cross-country analysis of developed countries. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(1), 105–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0440-0

- Fornell, C. G., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research,18(1), 39–50.

- Fragoso, R., Rocha-Junior, W., & Xavier, A. (2020). Determinant factors of entrepreneurial intention among university students in Brazil and Portugal. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 32(1), 33–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2018.1551459

- Gibb, A. (2002). In pursuit of a new ‘enterprise’and ‘entrepreneurship’paradigm for learning: creative destruction, new values, new ways of doing things and new combinations of knowledge. International journal of management reviews,4(3), 233–269.

- Hahn, D., Minola, T., Van Gils, A., & Huybrechts, J. (2017). Entrepreneurial education and learning at universities: Exploring multilevel contingencies. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(9–10), 945–974. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1376542

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

- Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European business review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013–0128

- Hassi, A. (2016). Effectiveness of early entrepreneurship education at the primary school level: Evidence from a field research in Morocco. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 15(2), 83–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2047173416650448

- Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D., Mosakowski, E., & Earley, P. C. (2010). A situated metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of business venturing,25(2), 217–229.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hidayati, A., & Satmaka, N. I. (2018). Nurturing entrepreneurship: The role of entrepreneurship education in student readiness to start new venture. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 18(1), 121–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2018.18.1.10

- Ireland, R. D., Covin, J. G., & Kuratko, D. F. (2009). Conceptualizing Corporate Entrepreneurship Strategy. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 33(1), 19–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00279.x

- Jabeen, F., Faisal, M. N., & Katsioloudes, M. I. (2017). Entrepreneurial mindset and the role of universities as strategic drivers of entrepreneurship: Evidence from the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(1), 136–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-07-2016-0117

- Khalid, N., Ahmed, U., Tundikbayeva, B., & Ahmed, M. (2019). Entrepreneurship and organizational performance: Empirical insight into the role of entrepreneurial training, culture and government funding across higher education institutions in Pakistan. Management Science Letters, 9(5), 755–770. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.1.013

- Khalifa, A. H., & Dhiaf, M. M. (2016). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: The UAE context. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 14(1), 119–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2016.14.1.11

- Klofsten, M., Fayolle, A., Guerrero, M., Mian, S., Urbano, D., & Wright, M. (2019). The entrepreneurial university as driver for economic growth and social change-Key strategic challenges. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 149–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.12.004

- Krueger, N. F. J., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing Models of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Journal of Business Venturing. Journal of Business Venturing2, 15(98), 411–432. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Li, L., & Wu, D. (2019). Entrepreneurial education and students' entrepreneurial intention: does team cooperation matter?. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research,9(1), 1–13.

- Linan, F., & Chen, Y. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

- Linan, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 907–933. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0356-5

- MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2011). Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: Integrating new and existing techniques. MIS Quarterly, 35(2), 293–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/23044045

- Martin, B. C., McNally, J. J., & Kay, M. J. (2013). Examining the formation of human capital in entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship education outcomes. Journal of business venturing,28(2), 211–224.

- Mathisen, J. E., & Arnulf, J. K. (2013). Competing mindsets in entrepreneurship: The cost of doubt. The International Journal of Management Education, 11(3), 132–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2013.03.003

- Naminse, E. Y., Zhuang, J., & Khan, H. T. A. (2018). Does farmer entrepreneurship alleviate rural poverty in China? Evidence from Guangxi Province. PloS One, 13(3), e0194912. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194912

- Nowiński, W., Haddoud, M. Y., Lančarič, D., Egerová, D., & Czeglédi, C. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Studies in Higher Education,44(2), 361–379.

- Pfeifer, S., Šarlija, N., & Zekić Sušac, M. (2016). Shaping the Entrepreneurial Mindset: Entrepreneurial Intentions of Business Students in Croatia. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 102–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12133

- Ratten, V., & Jones, P. (2020). Entrepreneurship and management education: Exploring trends and gaps. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100431. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100431

- Ridley, D., Davis, B., & Korovyakovskaya, I. (2017). Entrepreneurial Mindset and the University Curriculum. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 17(2), 79–100. http://www.na-businesspress.com/JHETP/RidleyD_Web17_2_.pdf

- Santos, S. C., Neumeyer, X., & Morris, M. H. (2019). Entrepreneurship education in a poverty context: An empowerment perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(sup1), 6–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12485

- Sarooghi, H., Sunny, S., Hornsby, J., & Fernhaber, S. (2019). Design thinking and entrepreneurship education: Where are we, and what are the possibilities? Journal of Small Business Management, 57(sup1), 78–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12541

- Sesen, H., & Pruett, M. (2014). The impact of education, economy and culture on entrepreneurial motives, barriers and intentions: A comparative study of the United States and Turkey. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 23(2), 231–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0971355714535309

- Shepherd, D. A., Patzelt, H., & Haynie, J. M. (2010). Entrepreneurial spirals: Deviation-amplifying loops of an entrepreneurial mindset and organizational culture. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 34(1), 59–82.

- Solesvik, M. Z., Westhead, P., Matlay, H., Parsyak, V. N., & Harry Matlay, P. (2013). Entrepreneurial assets and mindsets: Benefit from university entrepreneurship education investment. Education + Training, 55(8/9), 748–762. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2013-0075

- Sowmya, D. V., Majumdar, S., & Gallant, M. (2010). Relevance of education for potential entrepreneurs: an international investigation. Journal of small business and enterprise development,171, 626–640. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001011088769

- Vías, C. M., & Rivera-Cruz, B. (2020). Fostering innovation and entrepreneurial culture at the business school: A competency-based education framework. Industry and Higher Education,34(3), 160–176.

- Wach, K., & Wojciechowski, L. (2016). Entrepreneurial intentions of students in Poland in the view of Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 4(1), 83–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2016.040106

- Wardana, L. W., Handayati, P., Narmaditya, B. S., Wibowo, A., Patma, T. S., & Suprajan, S. E. (2020). Determinant factors of young people in preparing for entrepreneurship: Lesson from Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(8), 555–566. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no8.555

- Westhead, P., & Solesvik, M. Z. (2016). Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: Do female students benefit? International Small Business Journal, 34(8), 979–1003. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615612534

- Wibowo, A., Saptono, A., & Suparno. (2018). Does teachers’ creativity impact on vocational students’ entrepreneurial intention? Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 21(3), 1-12.

- Winkler, C., & Case, J. R. (2014). Chicken or egg: Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions revisited. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship,26(1), 37–62.

- Wu, S., & Wu, L. (2008). The impact of higher education on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in China. Journal of small business and enterprise development,15(4), 752–774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000810917843

- Yusof, S. W. M., Jabar, J., Murad, M. A., & Ortega, R. T. (2017). Exploring the cultural determinants of entrepreneurial success: The case of Malaysia. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences, 4(12), 287–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21833/ijaas.2017.012.048

- Zhang, S. N., Li, Y. Q., Liu, C. H., & Ruan, W. Q. (2020). Critical factors identification and prediction of tourism and hospitality students’ entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education, 26, 100234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2019.100234