Abstract

This paper examines the ways in which parents talk about their participation in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC), and the factors that, according to them, promote parental participation. Although parental participation has been studied to an extent as regards children’s academic attainment, up-to-date knowledge on the broader phenomena related to parental participation is lacking. The data were collected from a Finnish ECEC center that has a long tradition of encouraging parental participation in its operational environment in municipal ECEC center and were analyzed through the Social Capital Index. The results provide targeted knowledge on what tools could perhaps be functional in supporting parental participation. The findings indicate that the feeling of participating and being active is strongly influenced by the feeling of connectedness to and within the ECEC community among parents, children, and ECEC educators. The opportunities, structures, and traditions that enable parental participation are essential.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The findings in this article indicate that parental participation has studied largely but there are still new information to learn. Using variable models to study parental participation in Finnish Early Childhood Education and Care context can be found the triggers that urge parents to participate. The findings indicate how important the feeling of participating and being active is for parents in the ECEC community among parents, children, and ECEC educators. Parental participation is studied here through Social Capital Index, which broaden the concept of parental participation.

1. Introduction

This article examines parental participation and connectedness in Finnish Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC), the ways in which the parents themselves view their participation, and the factors that they consider meaningful regarding their activeness in participation. The data were collected from parents from a Finnish ECEC center which has long traditions and structures of encouraging parental participation in its operational environment as a part of its wider support for the care, growth, and learning of children within the municipal ECEC center. In this article, we refer to “parents” when we mean the children’s guardians and other caregivers in the homes.

Parental participation has been analyzed in previous empirical and conceptual literature; much of this research defines parental participation or involvement—here used synonymously—as a notion and categorizes its elements in different ways. In 1995, Epstein (as sited in Epstein, Citation2010) characterized six types of parental involvement include parenting, communicating, volunteering, participating in a child’s learning at home, decision making, and collaborating with community. In another classification by Formosinho and Passos (Citation2019), parental involvement has been divided into four dimensions: pedagogic, organizational, community and policy parental involvement. In the study of Janssen and Vandenbroeck (Citation2018), they divided parental involvement based on 13 curricula from around the world, into five categories: creating child-centered learning environments, monitoring developmental progress, negotiating pedagogical practice, ensuring smooth transition, and providing parental support. These categories seem to be largely created from the perspective of researchers or organizations such as school or childcare.

Parental participation has been studied from a range of perspectives, including in relation to enhancing children’s academic results (Krieg & Curtis, Citation2017; Polat & Bayindir, Citation2020; Smyth, Citation2017; Sylva et al., Citation2008) and from children’s perspective (Yngvesson & Garvis, Citation2019) in the ECEC settings. Furthermore, the parents’ expectations of the teaching and the quality of ECEC has been researched (Hu et al., Citation2017; Kekkonen, Citation2009; Zhang, Citation2015). There are also studies of parents’ potential to influence and become involved in ECEC (Formosinho & Passos, Citation2019; Heiskanen et al., Citation2019), but there is a lack of studies and literature on parents’ own views of participation and connectedness among the parents in the ECEC. The aim of this study is to begin to fill this gap by locating some of the factors that parents consider meaningful to them regarding their activeness in participation.

As described above, parental participation can be divided by elements or can take different forms such as participation in activities, or the feeling of being trusted and appreciated. These same elements are found in social capital theories, which we will thereby briefly present in the following, because this then enables us to examine parental participation more widely through the triangulate interaction of parents, children, and teachers.

1.1. Social capital index

This study continues the work of Onyx and Bullen (Citation2000) as they created and tested a Social Capital Index. We use those categories that were considered meaningful for the present examination. Onyx and Bullen (Citation2000) founded their theoretical framework on the social capital work of Coleman (Citation1988) and Putnam (Citation1993, Citation1994, Citation1995). Social capital has been seen as generated through several factors (Onyx & Bullen, Citation2000). These are: 1) participation in the local community; 2) social agency (plan and initiate action); 3) feeling of trust and safety; 4) informal neighborhood connections; 5) family and friends connections; 6) tolerance of diversity; 7) feeling valued by society, and 8) work connections. This notion and analytical tool of social capital and the elements or factors constructing it, enables a wider perspective on parental participation, because it provides an opportunity to further examine the connectedness among parents, educators, and children, and can facilitate the evaluation of the consequences of participation.

Parents may have their own agendas for influencing ECEC provision as desired or intended future states (Coleman, Citation1990). An active, trusting connection with other parents has positive effects on family wellbeing and both family and community social capital (R. D. Putnam, Citation2000; Onyx & Bullen, Citation2000). According to R. D. Putnam (Citation2000, 19), social capital is generated through the “connections among individuals—social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them.” It is an “aspect of social structures [–] making possible the achievement of certain ends that in its absence would not be possible” (Coleman, Citation1988, 98). They further elaborate that, “The social capital of the family is the relations between children and parents,” and other family members (Coleman, Citation1988, 110). Parents can convey social capital to their children through time spent together.

In the ECEC community setting, the network-generated social capital can lead to positive “gains” for all stakeholders: children, parents, and staff. This can take various forms; for example, intergenerational closure (Coleman, Citation1988) supports both parenting and the children’s value learning when some of the norms and values are shared across families in the community. Social capital can also support social connectedness. Among peers, this can cement the connections among children/staff/parents known as bonding social capital (R. D. Putnam, Citation2000). It can also create connections between individuals from different age groups or socioeconomic backgrounds and be considered bridging social capital (R. D. Putnam, Citation2000), when people who would not necessarily interact in other settings outside the ECEC community do have interactions. This is especially so in Finland where the nearby municipal ECEC center is commonly utilized by the families living in a particular area regardless of their income, educational level, or cultural and religious backgrounds.

Parental participation and parents’ social networks related to the ECEC community can be expected to hold a significance here: if the parents have an opportunity to form positive relationships to other parents as well as the ECEC staff, this may well motivate them to participate more in community events and activities. In the previous literature, social networks have been found to bring various gains to their members in the form of social capital effects. We have chosen to use the categories of Onyx and Bullen (Citation2000) that are based on the theories on social capital by Coleman (Citation1988) and Putnam (Citation1993, Citation1994, Citation1995).

1.2. Parental participation

In this study, parental participation is considered to comprise a partnership and participating in activities in reciprocal communication with children, other parents, and teachers on several levels (see Arnstein, Citation1969; Shier, Citation2001). Parents bring their cultural backgrounds, values, expectations, and knowledge of their child to the teachers and the teachers bring their professional skills and “know how” to the mutual conversations (Keyes, Citation2002). Naturally, the ECEC staff members also have their personal values, worldviews, cultures, perhaps also fears and prejudices that would contribute to the interaction (e.g., Kuusisto & Lamminmäki-Vartia, Citation2012; Rissanen et al., Citation2016). The various stakeholders are in different ways active agents and capable participants in the ECEC community. Parental agency is here understood in relation to the parents’ feeling of being valued, listened to, and enabled as participants to take an active role in the planning, implementation, and decision making in the ECEC (Kumpulainen et al., Citation2010).

Parental participation can include parents’ involvement in a range of activities and using the strengths of the child and the family in the mutual ECEC community activities. Continuous, open, and bi-directional communication between parents and ECEC teachers can improve the collaboration between them; this would support the child’s development (Garrity & Canavan, Citation2017; Reedy & McGrath, Citation2010). Parental participation requires trust, communication skills, and the willingness to negotiate and agree on various matters according to Shaeffer (Citation1999). Trust, as an intuitive feeling between the parent and ECEC teachers, can also constitute a two-way reciprocal conversation (Garrity & Canavan, Citation2017; McGrath, Citation2007; Reedy & McGrath, Citation2010) and respectful, appreciative collaboration (Souto-Manning & Swick, Citation2006). In the Finnish context, multicultural parents were satisfied with the information and conversations with the ECEC teachers according to Lastikka’s (2019) study.

The sense of community among parents is created through shared values, sentiments and beliefs combined with parents’ intrinsic and extrinsic involvement in mutual activities (Sergiovanni, Citation1999). A welcoming environment, working together, investing in communication, and building trust increase parents’ feelings of connectedness; this has also been shown to have a positive effect on the whole community’s connectedness (Rowe & Stewart, Citation2009). Additionally, shared actions give parents a wider perspective of the capabilities of their children (Tayler et al., Citation2006). Parents were more comfortable participating in school activities when they were acquainted with other parents, and were invited by other parents rather than only teachers (Curry & Holter, Citation2019). The parents modeled parenting to each other, and supported relationships between their children according to Curry and Holter (Citation2019). These studies are conducted with parents of school age children; however, there is lack of studies of ECEC parents’ perspectives.

The study by Van Laere et al. (Citation2018) presents parents’ perceptions of their participation connecting to childcare, whereas the ECEC teachers had a perception that parental participation connects to matters of teaching. In their study it became obvious that parents own perceptions were not noticed when there was a lack of time for reciprocal conversations between parents and teachers. Unequal power dynamics hinder parents’ abilities to express their perspectives in ECEC according to the study of Van Laere et al. (Citation2018).The perception of what is considered to be parental participation can vary between parents and teachers. Parents can have a feeling of participating as they prepare children for school, communicate with other parents (Curry & Holter, Citation2019), go through children’s artwork from school (Miller et al., Citation2014), or take part in parent evenings or other events.

Parents have different reasons for their lack of participation in ECEC community activities or conversations, such as difficulties in their work time schedules, or duties at home, (Purola, Citation2011; Reedy & McGrath, Citation2010). Sometimes the meetings are simply not convenient (Rouse & O’Brien, Citation2017). The teachers’ sensitivity (Kuusisto & Lamminmäki-Vartia, Citation2012) and teachers’ responsiveness towards parents and children (Powell et al., Citation2010) also affect parents’ desire to participate. Furthermore, ECEC teachers’ attitudes and perspectives of parents, their ideas, input, and feedback (Souto-Manning & Swick, Citation2006), abilities and justification for participation in ECEC settings (Venninen & Purola, Citation2013) have a significant impact on parental participation.

Previous literature illustrates a need to study parent participation through unique samples in order to learn more about how to further advance the relationships between families and teachers, as well as to examine what kind of practices could better support the parents’ sense of belonging in the ECEC provision (for example, Moorman Kim et al., Citation2012; Purola, Citation2011). The present study contributes to filling the gap in research in this area by providing new information on how Finnish parents see their participation in ECEC, and which factors they perceive as meaningful to them.

1.3. Parental participation in finnish ECEC

In Finland, parents’ interest in the ECEC of their children has recently mainly focused on the ECE’s contribution to the development of their children’s social skills and general wellbeing (Broekhuizen et al., Citation2015; Hujala, Citation1999; Kekkonen, Citation2009; Ojala, Citation2000), rather than their academic performance.

The first Finnish National Core Curriculum for ECEC (FNAE (Finnish National Agency for Education), Citation2016) guides ECE teachers toward co-operation with children’s parents providing them with the opportunity to participate in the planning and evaluation of the action in ECEC center. Many ECEC centers met these aims by having special introductory activities, such as having the teacher visit a child’s home before the family’s first visit the ECEC center. The parents are offered an opportunity to participate in designing and evaluating the educational program in the ECEC center. They can also join in the process to regularly create, implement, and assess their child’s individual ECEC plan. The curriculum also requires ECEC centers to have structures for parental participation.

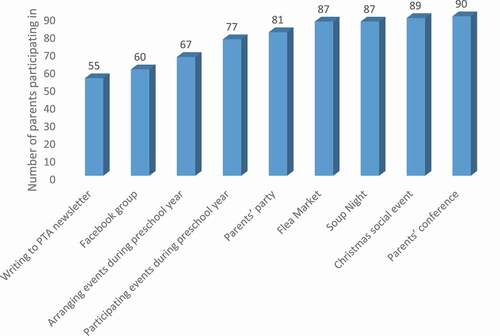

In previous year, the ECEC center studied here had also created many traditions to in which families could participate. Alongside traditional parents’ conferences, they had a flea market, soup night, PTA newsletter writing, Facebook group, and parents’ party and other events that parents organized with the ECEC staff. Having this many different events for parents to organize and participate is quite rare in Finnish ECEC.

2. Data and methods

This article presents an analysis of survey data from an ECEC center, which has emphasized the meaning of parental participation in supporting childcare, growth, and learning.

The research problems can be addressed through the following question:

What are the parental participation factors that are meaningful for parents in ECEC center?

Due to the nature of the functioning of the particular ECEC center in a research context, this article portrays a survey of successful parental participation in a municipal ECEC center in Finland. This ECEC center was selected because the methods of ensuring the participation of the children and their parents in the ECEC community were known. One of the special characteristics of this ECEC center was the strong structures that consciously support parental participation. Furthermore, this ECEC center had strong traditions of events that were executed together with ECEC teachers, children, and parents, such as soup nights, flea markets, parents’ parties, and other organized fixed events during the preschool year. In their comments on the communal atmosphere in the ECEC center, parents reported that ECEC teachers engaged new parents in this value since the first meeting by telling them to greet others and invite them to join in coming events at the ECEC center.

The data were gathered in 2015 through a semi-structured electronic questionnaire, and present the views of the parents from the ECEC center in question. The questionnaire link was sent to 115 current and former client families. All these parents received a cover letter that explained the meaning of this research and advised them of the opportunity to refuse to participate in the research at any time, according to ethical procedures. The responses were received from 93 parents giving the survey a response rate of 80%. Although there is always a possible bias in that it may be the more active parents that take the time to respond and send their answers, at least the high response rate gives this study a reliable ground of comprehensive representation of the views of these parents.

The questionnaire comprised 19 open-ended, and three multiple-choice questions, of which one had 10 options concerning forms of participation by parents. The participants were also asked to complete two open-ended sentences according to their experiences, views, and opinions about the ECEC center in question:

As I observed the other parents I thought_____________________________

For parents, their involvement is ___________________________________

There were a total of 619/651 answers for the seven open end questions used in this study. The data were analyzed through the Atlas ti. 6.2 program by an inductive process (Lodico et al., Citation2006). The coding of the parents’ written responses was based on words parents used such as the concepts of trust, atmosphere, conversation, connectedness, togetherness, worthiness, acknowledgment, and participation. These words or concepts constituted the data codes that were then formed into themes. Thereafter, each theme category was further examined to synthesize into main themes according to the social capital categories presented by Onyx and Bullen (Citation2000). The inductive process was completed twice to increase the reliability of this study. All the questions and written answers were originally in Finnish and translated in English by the author.

2.1. Limitations

This article is based on a survey which was conducted at one ECEC center. Hence, the findings cannot be generalized to the Finnish ECEC setting in general, as this ECEC center has already emphasized parental involvement in its practices. Therefore, we are very much aware that this setting is in many ways an exceptional case presenting good practices for supporting parent participation. Still, for the purposes of this research focus, these results align with our expectations. Furthermore, these findings can provide answers about what worked in one ECEC setting, suggesting what could also be tried at other ECEC centers to enhance parental participation. Most of the parents seemed very happy with the ECEC center; the study is strongly focused on the positive aspects of parental participation. Likewise, the survey questions investigated the factors that strengthened parental participation, the main interest in this study. Furthermore, the perspectives of ECEC teachers and the ECEC center director were not a part of this research. Observations on the actual moments of parent participation would have been useful additions to these data at the time. Even so, the findings provide a valuable foundation for further research and practice in particular for pursuing ways to strengthen further parental participation in ECEC settings. As mentioned later in this study, the diversity of parents’ ethnic, cultural, religious or language backgrounds was not found to influence their participation in the ECEC community. However, the present sample was small and possibly selected through the nature of the particular ECEC setting,

2.2. Ethical considerations

The ethical approval for this study has been gained through the municipal ECEC department. Parents’ consent for participation was attached in the questionnaire that included information on the study, its research ethics, and the proposed publication of findings. The right to interrupt or cease participation in the study at any time was also granted (see e.g., All European Academies, Citation2017).

Ethical considerations have been consciously implemented throughout the research process, from the initial planning and design and formulating the focus, through the choices made regarding the literature, methods, research context, participants, data gathering and analysis, and the reporting of the results. Parental participation can be considered a private and sensitive topic by some of the parents. Furthermore, there may be particular perceptions of “ideal,” “good,” or “right” responses connected to the personal or shared ideals of what is “good parenting,” that may also contribute to directing both the contents and the forms of the responses. We have been aware of this in interpreting the findings and realize the limitations and possible biases connected with research carried out with people.

3. Results

3.1. Participation in the community

In this study parents felt strongly about being in the ECEC community. In parents’ responses there were 211 mentions of being or doing together in the community, which represents the largest number of mentions in this study. Most of the parents were happy to be a part of this ECEC community within which they felt comfortable and at ease; as one parent commented: “I felt really fortunate about the fact that my own child and I were able to be a part of such an amazing community.”

The social capital effects that these parents can generate through the networks of trust can be seen in the data in their emphasis on the “connectedness” among the parents. This was seen as a result of a functional relationship and mutual communication between parents and teachers. Furthermore, it was perceived to result in positive feelings of togetherness within the network. One of the parent respondents summarized: “Connectedness can be created only by action and participation.” Parents also experience support from the ECEC teachers as well as from their peers, seeing that “[Parental participation] enhances the togetherness between families and provides support in challenging situations and life stages.” Parents’ active participation in ECEC activities, has made the ECEC center community stronger, as another of the respondents writes:

We have become a larger group, a part of a larger village, a family; we have people to whom we can turn, with whom we can speak in confidence about anything, gain friendship, genuine caring, and growth for the whole family.

The events organized within the ECEC center, also include families; other forms of parental participation in the ECEC center that were mentioned were social events (in the Finnish context), such as a flea market, a soup night, a Christmas social event (with snacks like rice pudding and gingerbread cookies), a Facebook group, a parents’ party, a parents’ conference, writing to the PTA Newsletter, a preschool play, and arranging special events during the preschool year when the children are six years old, and taking part in these events. All the events were highly rated by the parents, and even the least appreciated activity was still favored by 59% of respondents [. below]. In fact, most parents liked all the activities and events that the ECEC community offered them.

Taking part in the activities of the ECEC community was perceived to be demanding, but also resulted in the best of times for some of the parents: “It is hard at times, with all the hassle, but it is often also really rewarding and it constructs bonds between teachers, parents and children.”

This study shows that by participating in ECEC center activities, the parents learn to know their children’s ECEC world and their role in it. One of our research participants found: “It gives a whole new dimension to the children’s world. It is a privilege to be able to visit the ECEC center any time and to observe and participate whenever.”

At the core of these conversations in the ECEC community was the wellbeing of the child. As one of the parents noted: “There is a fair and available listening connection, time spent together, and parents and teachers share mutual goals for the best interests of the child.” Along similar lines, another parent pointed out: “Parents experience the staff more as partners in their children’s everyday lives and their upbringing, rather than just as the staff of a child care unit of a municipal ECEC department.”

3.2. Social agency

In this study, parents regarded themselves as having equal responsibility for creating a functional connection between themselves and the ECEC teachers, as well as with the other parents in the ECEC community. One parent wrote: “It is everybody’s task [to do it] together: ECEC adults, leaders, families, and hopefully also the administration.” Additionally, another parent describes: “It is the task of both parties: also parents ought to show interest towards their child’s ECEC.” Parental participation was also thought to include the support for the ECEC teachers: “People get into interactions. The relationships in the ECEC center become meaningful and support both families and the work carried out in the ECEC center.”

Teachers shared information in different ways with parents and parents shared information with each other, and they felt informed. As one of the parents wrote: ’Matters are communicated [to families], feedback is provided and opinions are enquired.’ In the data, parents indicated that they enjoyed the familiar structure of gaining information about the ECEC center’s events and topical matters through reading newsletters. One parent noted, “I like it when I can sit for a while on the porch of the ECEC center or reads the newsletters. ”On the other hand, inadequate information from a teacher to a parent caused disappointment and mistrust towards the whole ECEC center. As one respondent writes: “[Informing the parents] WOULD HAVE meant a working discussion liaison, and that parents would hear what is happening at the ECEC center”.

Parents getting to know each other as community members takes place mainly through joining different kinds of events in the ECEC community. As one of the parents noted: “The ECEC center welcomes the whole family and they organize activities and events that are open for everyone, which makes it easier to get to know each other better.” Parents helped the ECEC teachers to organize these events: they made soup, built props, made costumes for the play, and cleaned the stage afterwards: “We all helped out together in the ECEC center events, or participated in them as the audience. ”Doing things together and not just being a bystander was significant to some of the parents. “I also had to break down my own role as a bystander to become an active agent. I am very grateful for all this, and its influence is also visible in other areas of life.”

In this study, the ECEC welcomed parents to participate, and according to the parents, their perspective on children’s abilities were expanded. Enjoying mutual activities and sharing experiences through joint conversation connects parents and children. The world inside and outside the home were combined through the continuation of the mutual conversations at home. The parents considered their involvement, and doing things together in the ECEC community to be very important and good for the wellbeing of their child. They also gave each other advice and formed a peer support network. For instance, one parent wrote: “It is important! I learn to know my own child better; we have things to talk about together, since I know about her day, her friends, and her teachers.”

3.3. Feeling of trust and safety

In this study, parents’ trust towards teachers consists of intuition and reciprocal conversations; the parents did not consider trust to be a passively formed feeling. Instead, the parents integrated trust with practical level action, such as participating in mutual projects in the ECEC community. Parents’ trust towards the teachers was built in joint activities and communication as parents noted: “The trust was constructed through (participation in) mutual action,” and “[There was] active communication and trust.’

The feeling of trust relates closely to being heard according to these parents as one commented: “A sense of security is created: I am being heard and appreciated as a human being, so surely my child is also being heard and appreciated as his/her own person.’

3.4. Informal neighborhood connections

Meeting other parents begins from the very first day at the ECEC center one parent reported: “I visited [the ECEC center] for the first time. It was easy to get to know everyone, since the whole operational culture is targeted towards that.” The greatest opportunity to get to know other parents was in the daily meetings in the ECEC vestibule or other situations when dropping off and picking up children: “Every day we met at the [ECEC center] vestibule.” In addition, the parents met each other in the evenings at the ECEC center activities, and they also met each other outside the ECEC premises when they held children’s birthday parties or “play dates” at somebody’s home; sometimes they met in parks and playgrounds.

In this study, parents made many observations about other parents and they seemed to be a little surprised for the impression that all the parents apparently knew each other. For example, one parent wrote: “[I was surprised] that so many people seemed to know each other, as well as the personnel really well.” Parents also found wider community connectedness valuable for the ECEC center. As one parent stated:

[For the parents, the fact that they are involved] constructs the communality in the whole neighborhood. It is important that people know each other and the area around the ECEC center where their children spend their days. And they also get to know their child’s friends.

3.5. Tolerance of diversity

The ECEC community is formed by a heterogeneous group of individuals: children, parents, and teachers. The community gathered individuals and families from varying social backgrounds or status, religious beliefs, ethnicity, goal settings, who were all connected through their affiliation to the particular ECEC center. New parents whose children were only just beginning their attendance at the ECEC center noticed how the families and parents communicated with each other, and how little the sociodemographic backgrounds influenced their collaboration. A parent wrote, “We are so different in our backgrounds and income levels, and it does create different layers that some parents are not necessarily even aware of. However, this hasn’t been an obstacle in our co-operation and action. ”In this study, the diversity of parents’ ethnic, cultural, religious, or language backgrounds was not found to influence parental participation in the ECEC community.

3.6. Feeling valued in society

The experience of a welcoming atmosphere in a community has been an important factor in strengthening parental participation in this study and was also found in previous literature (Onyx & Bullen, Citation2000). The way teachers presented themselves as equals and not as civil servants was acknowledged by parents: “Natural and low threshold discussions both ways, being equals in the relationship with staff; rather than ‘a professional attitude towards customers’ always open doors for participation in the ECEC every day.” Furthermore, the community participation among parents, children, and ECEC teachers was experienced as being important in the data: “[I liked] feeling as a member of [the center], and experiencing all actors as equals in the ECEC community (children, staff and parents).’ Likewise, the nature of the cooperative relationships was mentioned in the data, as one of the parents said: “The relationships are close, and not civil servant-like.”

Parents had positive feelings towards the ECEC community and other parents and doing things together, and another parent exclaimed: “It is also important and fun. I have become friends with many wonderful people!” The common events and activities within the ECEC community gave more meaning to life. As one of the parents commented: It brings added content to everyday life.’

4. Discussion

In this article we identified parental participation from parents’ perspectives in the light of social capital categories presented by Onyx and Bullen (Citation2000) to give a wider perspective of parental participation in the ECEC community. The ECEC center parents participated in their local community by participating in ECEC activities with other parents from the same neighborhood. Through shared action with children and ECEC teachers, parents gained a better perspective on the entire world in which their children lived as the separate parts of the world at home and the unknown world at the ECEC provision were combined; this is in line with the results of Tayler et al. (Citation2006). Parents were able to join activities and have an impact on the ECEC “world” together with their children. Parents’ participation encouraged other parents to participate more than invitations from the ECEC staff (see Curry & Holter, Citation2019)

Parents’ social agency in the ECEC center and its community was clearly seen in their answers. The role of parents themselves taking responsibility for cooperation and building connectedness within the social network in this particular ECEC center seems remarkable. The parents did not consider trust to be a passively formed feeling. Instead, the parents’ integrated trust with practical level action, such as participating in mutual projects in the ECEC is community. These actions are consistent with the findings of Souto-Manning and Swick (Citation2006). Parental participation from the parents’ perspective is accomplished by doing things together, with other parents, teachers, and children. In line with the study of Rowe and Stewart (Citation2009), these parents found that making and doing things together generates a feeling of connectedness, when the responsibility for co-operation falls on both teachers and parents. The atmosphere in the ECEC center had a great influence on the parents’ feeling of connectedness. The atmosphere was created by the ECEC teachers as well as the parents and the children. As an agent, every parent molds participation and the atmosphere at ECEC community by such a simple acts as greeting or not greeting each other every day.

The parents felt that they were given the space and trust to act as a part of the ECEC community. Mutual trust was built through shared action, knowledge, responsibility, conversations, and numerous opportunities to select the form of participation that felt most comfortable for each of them from a range of events and activities organized in the ECEC. Parental participation was found to stem from a number of succeeding, open and reciprocal conversations between parents and ECEC teachers, requiring, but also further generating, mutual trust on both sides as in the studies of McGrath (Citation2007), Garrity and Canavan (Citation2017), Reedy and McGrath (Citation2010), and Van Laere et al. (Citation2018). Here, trust, which as a notion also holds a key role in the theories on social capital, was seen as being built through common activities in the social network of the ECEC community. Knowledge can be seen as power that creates feelings of trust, and in contrast, the lack of information can create mistrust on the part of both teachers and parents, according to McGrath (Citation2007). In one case parent’s feeling of not being heard by the teachers caused mistrust and feelings of disconnection from the community when unequal power dynamics between a parent and a teacher are met as was reported in the study by Van Laere et al. (Citation2018).

As parents got to know each other and their children made friends at the ECEC center, parents and children connected outside of the ECEC center. Parents and children met each other in the local park, at children’s’ birthday parties, and during other play events. Thus, parents supported children´s friendships, as was shown in the study of the school context by Curry and Holter (Citation2019).

Parents’ responses did not bring up any discrimination, but on the contrary, parents emphasized through the survey, that working together is important. One parent wrote how different the parents were, and still they fit together very well. In Finland, there is lack of information about parental participation concerning culturally and linguistically diverse parents (Lastikka, Citation2019). However, in the study by Lastikka (Citation2019), parents were content with the information and reciprocal conversations with the ECEC teachers. In the study, it was indicated that these conversations and getting to know different cultures at the ECEC center, create a good ground for co-operation in the ECEC center.

Parents felt as members of a community and had friends at the ECEC center. The parents felt that continuous, open, and bi-directional communications between parents and ECEC teachers were a way to improve the collaboration, contributing towards supporting the child’s development; these findings also align with Reedy and McGrath (Citation2010), and Garrity and Canavan (Citation2017). The structure of the ECEC center was formed to empower the parents and their children, teachers, and other parents. Social knowledge grew stronger and parents gained a feeling of connectedness by getting and giving support from both the teachers and the peers.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to locate the factors that parents themselves find meaningful for their participation in ECEC. In the search for elements or aspects with which to enhance the parental participation in the ECEC settings, we discovered six factors related to the previous literature on social capital in the data from these parents (Onyx & Bullen, Citation2000) which parents recognized as important for their participation and which at the same time enhanced social capital in the ECEC center. Firstly, (1) participating in the ECEC community’s formal gatherings and (2) being active members of community made parents (3) feel valued by the community. Furthermore, they also became acquainted with other parents in the neighborhood; that made it possible for them to (4) take part in informal gatherings in the neighborhood. As the parents got to know each other, they felt trusted, and they trusted each other in the community regardless of the (5) community diversity and the variance between the parents’ social, cultural, educational, economic backgrounds. Finally, we concluded that the connection of successful parent participation, from parents’ perspective, contributed to the parents’ experience of mutual connectedness as they (6) felt valued in the society. In this study two categories of the Social Capital Index was not found since questions related to parents’ work or family connections were not enquired. Parents did not emphasize their participation in pedagogical matters, but more the social aspect of being part of the community and taking part in events and enjoying the feeling of connectedness. As so, these six Social Capital Index categories give a wider perspective on parents answers than the more pedagogical parental participation categories by Epstein (Citation1995) or Formosinho and Passos (Citation2019), or the finding of 13 curriculums from around the world (Janssen & Vandenbroeck, Citation2018).

Although a limited survey sample like this cannot provide generalizable knowledge or quick-fix solutions for enhancing parental involvement and participation as such, these results do further signify the importance of reciprocal communication in the ECEC community. The findings also indicate that in order for the ECEC community to actually enhance parent participation and connectedness in its operational environment, the mutual activities should in fact gather all members of the ECEC community—children, staff, and families—as active participants. That way, parents can mutually take responsibility for their own participation, and create connectedness and social capital for themselves and their children. Parent’s also indicated that they supported the ECEC staff and other parents alongside participating in the ECEC center events.

Equality was not shown in this study; hence, we suggest that in further studies, diversity is an important aspect to examine in a wider sampling in order to support equal opportunities for all parents to participate in early childhood education communities.

This study indicates that parental participation in the ECEC center can enhance social capital more widely, and can be an important factor to promote equality in a community. These results also indicate that parental participation should be studied more by using different theories than so far have been used. Thus, parents’ own perspectives could be more deeply analyzed. The Social Capital Index presents a new perspective on parental participation, and opens new possible structures to support parents’ experiences of participation from another angle than pedagogical. The ECEC should create structures and traditions that enable parents to participate, and help to connect parents to each other.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Karoliina Purola

Karoliina Purola is completing her PhD at the University of Helsinki. Throughout her career, she has worked as a service leader in the Finnish municipal early childhood education and care (ECEC) setting. Her research focuses on parental participation in ECEC, with several published articles on this topic.

Arniika Kuusisto

Arniika Kuusisto is a Professor of Child and Youth Studies, especially Early Childhood Development and Care, at Stockholm University, Sweden. She is also an Honorary Research Fellow at the Department of Education, University of Oxford, UK, and Research Director and Docent at the Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland.

References

- All European Academies. (2017). The European code of conduct for research integrity. Retrieved from http://www.allea.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ALLEA-European-Code-of-Conduct-for-Research-Integrity-2017.pdf

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Broekhuizen, M., Leseman, P., Moser, T., & Van Trijp, K. (2015). Stakeholders study: Values, beliefs and concerns of parents, staff and policy representatives regarding ECEC services in nine European countries: First report on parents. D 6.2. Retrieved from http://ecec-care.org/resources/publications/

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology, 94(94), 95–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

- Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of Social Theory. Harvard University.

- Curry, K. A., & Holter, A. (2019). The influence of parent social networks on parent perceptions and motivation for involvement. Urban Education, 54(4), 535–563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085915623334

- Epstein, J. L. (1995). School/family/community partnerships. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(9), 701–712.

- Epstein, J. L. (2010). School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools. Westview Press. EBook ISBN 9780813391861.

- FNAE (Finnish National Agency for Education). (2016). The National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care. Regulations and Guidelines: 10. Finnish National Agency for Education.

- Formosinho, J., & Passos, F. (2019). The development of a rights-based approach to participation: From peripheral involvement to central participation of children, parents and professionals. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 27(3), 305–317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2019.1600801

- Garrity, S., & Canavan, J. (2017). Trust, responsiveness and communities of care: An ethnographic study of the significance and development of parent-caregiver relationships in irish early years settings. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, (5), 1–21, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1356546

- Heiskanen, N., Alasuutari, M., & Vehkakoski, T. (2019). Intertextual voices of children, parents, and specialists in individual education plans. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1650825

- Hu, B. Y., Zhou, Y., & Li, K. (2017). Variations in Chinese parental perceptions of early childhood education quality. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(4), 519–540. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1331066

- Hujala, E. (1999). Challenges of Childhood Education in a Changing Society. In C. H. Keng, F. Haron, M. Dhamotharan, & A. Bala (Eds.), Excellence in Early Childhood Education (pp. 133–151). Pelanduk.

- Janssen, J., & Vandenbroeck, M. (2018). (De)constructing parental involvement in early childhood curricular frameworks. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26(6), 813–832. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1533703

- Kekkonen, M. (2009). Vanhempien näkemyksiä varhaiskasvatuksen kehittämiseksi. [Parents’ Perceptions to Develop Early Childhood Education.]. In J. Lammi-Taskula, S. Karvonen, & S. Ahlström (Eds.), Lapsiperheiden hyvinvointi (pp. 162–171). Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos.

- Keyes, C. R. (2002). A way of thinking about parent/teacher partnerships for teachers. International Journal of Early Years Education, 10(3), 177–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0966976022000044726

- Krieg, S., & Curtis, D. (2017). Involving parents in early childhood research as reliable assessors. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(5), 717–731. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1356601

- Kumpulainen, K., Krokfors, L., Lipponen, L., Tissari, V., Hilppö, J., & Rajala, A. (2010). Learning Bridges. In Toward Participatory Learning Environments. University Print.

- Kuusisto, A., & Lamminmäki-Vartia, J. (2012). Moral foundation of the kindergarten teacher’s educational approach: self-reflection facilitated educator response to pluralism in educational context. Education Research International, 2012,1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/303565

- Lastikka, A -L. (2019). Culturally and linguistically diverse children’s and families’ experiences of participation and inclusion in the Finnish early childhood education and care. University of Helsinki. http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2019102835162

- Lodico, M. G., Spaulding, D. T., & Voegtle, K. H. (2006). Methods in educational research: From theory to practice. Jossey-Bass.

- McGrath, W. H. (2007). Ambivalent partners: power, trust, and partnership in relationships between mothers and teachers in a full-time child care center. Teachers College Record, 109(6), 1401–1422.

- Miller, K., Hilgendorf, A., & Dilworth-Bart, J. (2014). Cultural capital and home–school connections in early childhood. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 15(4), 329–345. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2014.15.4.329

- Moorman Kim, E., Coutts, M. J., Holmes, S. R., Sheridan, S. M., Ransom, K. A., Sjuts, T. M., & Rispoli, K. M. (2012). Parent involvement and family-school partnerships: examining the content, processes, and outcomes of structural versus relationship-based approaches. The Nebraska Center for Research on Children, Youth, Families and Schools. Working Paper 6. http://cyfs.unl.edu/resources/downloads/working-papers/CYFS_Working_Paper_2012_6.pdf

- Ojala, M. (2000). Parent and teacher expectations for developing young children: A crosscultural comparison between Ireland and Finland. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 8(2), 39–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930085208561

- Onyx, J., & Bullen, P. (2000). Measuring social capital in five communities. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 36(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886300361002

- Polat, Ö., & Bayindir, D. (2020). The relation between parental involvement and school readiness: The mediating role of preschoolers’ self-regulation skills. Early Child Development and Care, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1806255

- Powell, D. R., Son, S.-H., File, N., & San Juan, R. R. (2010). Parent-school relationships and children’s academic and social outcomes in public school pre-kindergarten. Journal of School Psychology, 48(4), 269–292. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2010.03.002

- Purola, K. (2011). Päiväkodin vanhempien, kasvattajien ja johtajan sekä VKK-Metron toimijoiden näkemyksiä vanhempien osallisuudesta päivähoidon toiminnassa. [Parents’, Daycare Personel´s, Leaders’ and VKK-Metro Actives’ Perceptions on Parents’ Involvement in Day Care]. Pro-gradu tutkielma. Helsingin yliopisto.

- Putnam, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. University Press.

- Putnam, R. (1994). Bowling alone. Democracy in America at the end of the twentieth century. Paper presentation at the nobel symposium democracy’s victory and crisis, Uppsala Sweden.

- Putnam, R. (1995). Tuning in tuning out; the strange disappearance of social capital in America. Political Science and Politics, 28(04), 664–683. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096500058856

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone. The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster.

- Reedy, C. K., & McGrath, W. H. (2010). Can you hear me now? staff–parent communication in child care centres. Early Child Development and Care, 180(3), 347–357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430801908418

- Rissanen, I., Kuusisto, E., & Kuusisto, A. (2016). Developing teachers’ intercultural sensitivity: case study on a pilot course in finnish teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59(2016), 446–456. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.07.018

- Rouse, E., & O’Brien, D. (2017). Mutuality and reciprocity in parent–teacher relationships: understanding the nature of partnerships in early childhood education and care provision. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 42(2), 45–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23965/AJEC.42.2.06

- Rowe, F., & Stewart, D. (2009). Promoting connectedness through whole school approaches: A qualitative study. Health Education, 109(5), 396–413. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09654280910984816

- Sergiovanni, T. J. (1999). Building Community in Schools. Jossey-Bass.

- Shaeffer, S. (1999). Community Partnership in Early Childhood Care and Development. In C. H. Keng, F. Haron, M. Dhamotharan, & A. Bala (Eds.), Excellence in Early Childhood Education (pp. 201–229). Pelanduk.

- Shier, H. (2001). Pathways to participation: openings, opportunities and obligations. A new model for enhancing children’s participation in decision-making, in line with article 12.1 of the United Nations convention on the rights of the child. Children & Society, 15(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/chi.617

- Smyth, C. (2017). Maximising advantage in the preschool years: parents’ resources and strategies. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 42(3), 65–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23965/AJEC.42.3.08

- Souto-Manning, M., & Swick, K. J. (2006). Teachers’ beliefs about parent and family involvement: rethinking our family involvement paradigm. Early Childhood Education Journal, 34(2), 187–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-006-0063-5

- Sylva, K., Scott, S., Totsika, V., Ereky-Stevens, K., & Crook, C. (2008). Training parents to help their children read: A randomized control trial. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(3), 435–455. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/000709907X255718

- Tayler, C., McArdle, F., Richer, S., Brennan, C., & Weier, K. (2006). Learning partnership with parents of young children: studying the impact of a major festival of early childhood in Australia. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 14(2), 7–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930285209881

- Van Laere, K., Van Houtte, M., & Vandenbroeck, M. (2018). Would it really matter? the democratic and caring deficit in ‘parental involvement’. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26(2), 187–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1441999

- Venninen, T., & Purola, K. (2013). Educators’ View on Parents’ participation on three different identified levels. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research, 2(1), 48–62.

- Yngvesson, T., & Garvis, S. (2019). Preschool and home partnerships in Sweden, what do the children say?. Early Child Development and Care, 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1673385

- Zhang, Q. (2015). Defining ‘Meaningfulness’: enabling preschoolers to get the most out of parental involvement. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 40(4), 112–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911504000414