Abstract

The aim of this paper is to present and explain the long and bitter contestation between two poles over the orientation, the aims and the content of education as well as the form of the Greek language to be used in the school textbooks. During the last seventy years (1750–1821) of the Ottoman rule of Greece the poles were cultural but were transformed into mostly social and political after independence (1829). The paper argues that the main reasons of this contestation were their completely opposite views about the historically right cultural future of the reborn nation and the daily widening after independence cultural schism between a highly educated elite and the vast majority of poor and uneducated people as a result of unequal and change-resisting educational provisions. The paper elaborates on the composition, the propositional content, the discursive strategies and the linguistic devices of the two poles.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

For almost two centuries(1779-1977) Modern Greek Education was plagued by a deep cultural schism between the supporters of Ancient Greek culture and language and the supporters of Modern Greek culture and language. The leaders of the Orthodox Church of Greece, the Greek diaspora and the rich land owners supported the imposition of Ancient Greek as the language to be taught in both primary and secondary education while the modern novelists, poets and intellectuals supported the modern Greek culture and language. This absurd contestation led to an equally absurd dilemma about the preferable for modern Greece cultural future and, therefore, about the type of education (theoretical and practical) and the content of the curricula that should be introduced. These dilemmas have been discussed several times in the last fifty years. This paper aspires to offer a new explanation by using a new theoretical framework.

1. Introduction

I have been engaged with the study of modern Greek history of education for fifty years now and I am well aware of the intractable problem of the long series of abortive educational reforms in Greece from the end of 19th to almost the end of 20th century. Greek historians of education became conscious of this problem after the well-known Greek historian of education Alexis Dimaras published a 2-volume history of Modern Greek education under the title The Reform that did not materialise. His book brought to light some very interesting public papers (bills, laws, circulars, statements, decrees) dating from 1821 to 1967 which outlined very ambitious plans about qualitative reforms in Greek education that led to very little change. Some bills were never voted into laws, some laws were put aside from the very first day after their enactment, others were abandoned with the excuse that circumstances were not yet ripe, and others were overturned by counter reforms introduced by the next government(s) (A.Dimaras,1, ιζ-κα).

A number of Greek educational historians, comparative scientists and sociologists, among them professors S. Bouzakis, A. Kazamias, A. Frankoudaki, N Mouzelis and the author of this paper tried to interpret this problem. The proposed interpretations varied. Bouzakis suggested that the main reasons were, first, the discontinuity of political leadership not only in its government shakeups (between 1920 and 1928, for example, there were 34 government changes within an 8-year period (Bouzakis, Citation1999), but also in its spells of dictatorship, and, second, the foreign political and economic dependency of the country. Frankoudaki suggested that the demise was the result of the strong modern cultural input of the so called Generation of the Thirties (Frankoudaki, Citation1992) Kazamias (Citation1995, 40-72) proposed four inter-connected factors: the nature and role of the Greek state, the nature of the Greek socio-economic formation, the relative school autonomy, and the ambiguities and contradictions of reforms. Mouzelis (Citation1978) saw it as the result of Greek formalism, which, according to him, is a political and cultural aspect of Greek underdevelopment. My proposal was based on Hans Weiler’s theory of compensatory legitimation, which he used to explain the French pattern of reform and non-reform. In my article in Comparative Education(71-84) in 1998 I suggested that the great number of the Greek governments’ attempts to reform education were inteoduced in an effort to compensate for the state’s’ great legitimation deficit. Their efforts, nevertheless, failed because there were neither enough preparation nor the necessary financial support for the reforms (Persianis, Citation1998).

After reading the postmodern theories about nationhood and cultural identity (B. Anderson, Citation1983; Kristeva & Moi, Citation1986; S. Hall, Citation1996a, Citation1996b; H. Bhabha, Citation1990; E. Hobsbawm, Citation1992; Fairclough & Wodak, Citation1997; Ozkirimli, U. (Citation2000); B. Benwell & E. Stokoe (Citation2006); and others) I came to believe that they provide a theoretical basis which could explain the phenomenon of abortive educational reforms in Greece more adequately than the theoretical frameworks applied so far. So, I decided to look into the problem by applying the postmodern theoretical framework.

The most important theoretical postmodern conclusions I had in mind are the following ten:

“Treating nationhood and cultural identity[.] as essential, unified, eternal and fixed is problematic”[…]. They are ’products of language and discourse’ (E. Klerides, Citation2009,1234).

“Different members of the nation promote different, often conflicting, constructions of nationhood”(Ozkirimli & Theories of Nationalism, Citation2000,228).

“National identification and what it is believed to imply can change and shift in time, even in the course of quite short period”(Hobsbawm, Citation1992,11).

“Changes in the shape and form of an identity are always associated with its determinate conditions of existence, including material and symbolic resources”(Hall, Citation1996a,2).

‘A mode of representation which has been used to produce and circulate the image of the nation is narration΄(Bhabha, Citation1990,1).

“The practice of narration involves the ‘doing’ of identity” (Benwell&Stokoe,Citation2006,138).

There can be three levels in analyzing the ways the “discursive identities ”are formed: the level of propositional contents, the level of strategies, and the level of language realisation’ (cited by Klerides, Citation2009, 1238).

“The educational constructs of cultural and national identity are linked to, and influenced by, the articulation of the nationhood in the other social fields (the political, media, academic)” (as cited in Klerides, Citation2009,1235).

“The role of national education is not so much to protect, preserve and pass on the nation’s cultural inheritance. Instead, (it) […] is to participate in the construction and transmission of the heritage to the masses” (as cited in Klerides, Citation2009,1235) and

“Discourse is not produced without context and cannot be understood without taking the context into consideration” (Fairclough & Wodak, Citation1997, 276).

From the above list of the relevant postmodern findings the author extracted the following points which he used as theoretical framework of his paper:

The importance of cultural identity for explaining the educational problems of a country very rich in culture but very poor in material resources like Greece.

The changeability of cultural identity. This finding contradicts the very strong belief of Modern Greeks that identity is biological, fixed and permanent.

The importance of discourse in the construction and reconstruction of cultural identity.

The importance of the role of institutions both educational (schools, universities) and other (political, media) in the construction, reconstruction and dissemination of cultural identity and in he formulation of educational policies.

The importance of the role of historical circumstances and symbolic and material resources.

2. Material and methodology

The central theme of this paper is the long and bitter educational contestation between two originally cultural, and later transformed into mostly social and political, poles, the pro-Ancient and the Pro-Modern. To this effect, the paper provides a detailed account of their history, composition, propositional content, discursive strategies and linguistic realization, the major areas of contestation(language of instruction, the teaching of Ancient Greek and the role of the Orthodox Church in education) as well as the hybrid solution reached in 1977. To facilitate understanding, the presentation starts with two introductory to the basic theme chapters, the first providing a historical background and the second supplying the keys to understand the Modern Greek “psyche” by providing a detailed account of the development of the Modern Greek cultural identity.

Thus, the discussion takes place in the following five chapters:

3. the historical background,

4.the construction and reconstruction of Greek cultural identity,

5. the presentation of the two opposite poles contesting about the goals and content of education(their composition and the processes and means they have employed in the promotion of their distinct policy).

6.the main areas of contestation, that is

6.1the language of the Readers used in primary education and the content of the school textbooks,

6.2the excessive emphasis on the teaching of Ancient Greek in secondary and higher education,

6.3the role of the Greek Orthodox Church in the construction of Greek cultural identity and the formulation of educational policy.

7.the 1976/1977 hybrid educational reform and the present situation.

3. The historical background

There is a rich historical evidence that the construction of cultural and national identity in Modern Greece has mainly been affected by eight factors. The first five are a) the Orthodox Church, b) the Greek diaspora, c) the very strong western European cultural influences, d) the imposition of a centralized government from the very beginning and e) the serious concerns about national security. The sixth factor is the Ionian islands group of modern Greek poets known as Eptanisiaki Scholi, the seventh the so called generation of the thirties,and the eighth the strong influence of the communist ideology as from the beginning of 20th century.

The influence of the Orthodox Church can be distinguished into two periods, the one during the Ottoman rule (1453–1821) and the other during independence. During the Ottoman rule the Oecumenical Patriarchate which the Orthodox Church of Greece belonged to until 1833 in addition to its religious, moral, social, political and financial power, was the highest authority in education for all the Orthodox Christian communities of the Ottoman Empire, including the Greek one, with a monopoly in all educational affairs: It designated the curricula, the syllabi and the textbooks, it employed the teachers and it determined the values and principles which would govern all the educational institutions. This, of course, meant also the automatic spread of its epistemology(essentialism).

With the exception of a few distinguished high schools, the education offered by the Oecumenical Patriarchate was mostly limited to the teaching of reading (of the Bible) and writing and, therefore, ineffective in enlightening the masses of the enslaved people and encouraging them to get rid of their ignorance and superstitions as well as their oppressive yoke. The Church’s main contribution was the maintenance of a strong Orthodox faith, which became, as we shall see in the next chapter, the main constituent of the Greek cultural identity during the Ottoman rule.

These limitations in the Patriarchate’s educational role can explain the initiative undertaken by some Greek intellectuals of the diaspora. Influenced by the ideas of Enlightenment (K. Dimaras, Citation1998, pp. 10–22) and the ideals of the French Revolution, they were convinced that there was a need of a new spirit in occupied Greece which would open the minds of the people and help them feel the importance of freedom and responsible citizenship. This could not be generated by illiterate and uncultured parents or a disorganised and backward society but only through formal education. That is why formal education in Greece was charged with more responsibilities in comparison with those in other European countries and has become much more important.

The intellectual who wholeheartedly promoted this role and dedicated more than fifty years of his life to this pursuit was Adamantios Koraes, a humanist Greek doctor in Paris (1780–1833) well versed in, and editor of a great number of, Ancient Greek texts. He strongly believed that, prior to any revolution for the liberation of Greece, there was a need for the enlightening of the nation and the construction of a new cultural identity for the enslaved Greeks through the teaching of Ancient Greek texts, especially philosophy. He also believed in the need for the direct “transportation” of the “lights of Europe” to Greece as the best way for quick cultural and social progress and europeanisation (K. Dimaras Citation1964,193–202).

In this way, Koraes became the most zealous supporter of western cultural influences and at the same time the first and most well-known protagonist of a contestation which divided the Greek nation until late in the 20th century with regard to the content of the Greek cultural identity and the role of foreign cultural influences upon it. The dilemma was whether Greece should develop as a Balkan nation, just like all the other nations living around, or whether it was entitled, as the heir of Ancient Greek civilisation, to develop straightaway into a civilised European state by quickly borrowing the European culture, civilisation, education and modern laws of justice and administration.

The fourth factor is the imposition of a centralized form of administration in Greece. This is easy to explain. Centralisation was imposed on Greece four years after independence by the three self-appointed guarantor powers (Britain, France and Russia) through the appointment of a German prince, Otho, as king of Greece in 1833. Under normal conditions, the introduction of centralisation would have been, perhaps, objected to by the people, because Greece had had a very long and strong tradition of communal administration during the Ottoman rule. The very poor social and economic conditions of the country, however, together with “the still clientelistic orientation of most Greek politicians and parties”(Mouzelis,134) have contributed to the consolidation and maintenance of the state’s strong power and the absolute control of education.

The strongest, however, legitimation for the central state control of education have been the serious public concerns about national security. According to 1997 OECD report on Greek education

There is a long Greek tradition for education as the dominant agent of maintenance and preservation from one generation to the other of the values that have formulated the specific qualities of the Greek civilisation in its historical development through the ages. Greeks feel strongly that this need, namely to protect the Greek identity from erosion now that the country is gradually being united with Europe, should be strengthened (OECD, Citation1997, 4).

It is these concerns that have determined and maintained to a great extent the orientation, content and practices of Greek education and have persistently fueled the contestation and mutual distrust between the two poles. A characteristic example of this distrust has been the initiative of both poles to upgrade, when they had the power, some very critical for the maintenance of an unchanged cultural identity educational laws to the status of constitutional articles in order to make it extremely difficult for the opposite pole to change them whenever they came to power. One such case is the provision forbidding the foundation and functioning of private universities in the country(article 16 of the Greek Constitution).

The roots of insecurity go back to the establishment of the Modern Greek state. Because the liberated by the 1821 Revolution territory was very small (only Peloponnese and Sterea Ellada), the Greek Government felt that it was its duty not only to protect it from the previous occupants but also to find ways to expand it before the other Balkan nations, who had also fought for liberation from the Ottoman Empire and had irredentist aspirations, acted. One such action was the Greek National Assembly’s endorsement in 1844 of the “Great Idea”, that is, the ideal of mobilizing the Greeks all over the world to join forces for the liberation of all former parts of the Byzantine Empire (Markezinis, 1,108).

To achieve such a difficult mission there was a need for a strong national narrative which would keep nurturing a series of idealist Greek young generations prepared to sacrifice their lives for the safety and integrity of their motherland. The people who had the political and cultural power at the time thought that the most effective way to achieve this was through an education which would make the Greek people believe that they belong to a superior and unique nation. Thus, they charged their schools and especially the teachers of Ancient Greek and Ancient History(philologists) with the protection, preservation and passing on the nation’s cultural identity. This is how the Greeks came to believe that their cultural was also their national identity and it was “essential, unified, eternal and fixed”, even biological, and that they are a superior race.Footnote1 This belief is very aptly described by Greek historian George Dertilis:

A great legacy, for some biological and for others cultural, was considered sufficient to acclaim the Greek nation as the chosen one []. Such ideas were natural in the time they were firstly expressed. They could have been honestly expressed by historians who had not heard of or misunderstood Darwinism and strongly held romantic views about history and nations […]. Such ideas, however, are, at least, strange in 20th century and considered scientifically unacceptable today. Yet, they have been maintained and they continue to interpret our history by talking about the greatness of the Race. Thus, the unwise worship of Ancient Greek and Βyzantine times have nursed our paranoid syndromes, the megalomania, combined with a persecution mania: a chosen nation, but brotherless (Dertilis,11).

The sixth factor is the progressive group of poets who formed the Eptanisiaki Scholi. They lived in the Ionian islands which were lucky to be under European (alternately French, Italian and British) and avoid the Ottoman rule. Their culture was greatly affected by the Italian. This explains both their modern themes and form of their poetry and their strong support for the popular language. The leader of the group was the national Greek poet (he wrote the Greek national anthem) Dionysios Solomos (Solomos, Citation1824).

The seventh factor is the dynamic group of intellectuals, poets and novelists who are known as the Generation of the Thirties (read more in chapter 5).

The last factor is the wide dissemination of the communist ideology in Greece, especially at the end of World War II, when a separate communist government was established at the Greek mountains and a bitter and long (5 years) civil war broke out between pro-western and communist factions. During that time nearly all Balkan states were loyal to the Soviet Union and they were considered by the Greek state as its worst enemies, because they provided asylum to the Greek communist revolutionaries and had territorial claims over Greece. As a result, the division between the two warring sides became very deep to the extent that it is still alive and active and continues to poison the everyday political and cultural life in the country. Despite the final win of the pro-western political parties, the political and cultural schism continued, underground for many years until the fall of the Military Junta (1967–1974) and the full restoration of civil liberties. The contestation today is mainly over social and foreign policy. A very pertinent statement on this matter was that of Prime Minister Constantinos Karamanlis who strongly declared from the podium of the Greek parliament in 1976 that’ politically, defensively, economically, culturally Greece belongs to the West(Karamanlis & (Prime Minister of Greece), Citation1976).

4. The construction and reconstruction of Greek cultural identity

The romantic conception of cultural and national identity described above by Dertilis has misled Greek historians and comparativists and has obstructed them from realising that there is ample evidence that there has been a constant structuring and restructuring of it. This chapter is meant to provide the relevant evidence for this argument.

As we can see in , in the period 1500 to 1750 the Greek cultural identity constituents were the Orthodox religion and, to a lesser extent, the Greek language. The latter was not respected enough during that time because it had borrowed a great number of Turkish words throughout the long period of Ottoman rule. In the second half of the 18th and the first quarter of the 19th century, however, greekness prevailed over religion as a constituent of the Creek cultural identity, because of the strong influence from the addition of three new very important constituents, namely the feelings of superiority, uniqueness and longevity of the Greek “race”. This was the result of the Greek people learning, through the wide development of classical studies in Europe, about their ancestors’ enormous cultural achievements. In the second half of the 19th century, as a reaction to the German historian Fallmerayer’s theory about a complete extinction of Ancient Greeks following the Slav influx in South Greece(Falmerayer, Citation1830)another constituent, that of the unbreakable continuity of the nation’s life, was added. The addition was helped by the publication in 1878 of the History of The Greek Nation by Constantinos Paparrhegopoulos, Professor of The School of Philosophy of Athens University, who was the first to write about a three -period (Ancient Greece, Byzantine, Modern Greece) conception of Greek history (Paparrhegopoulos, Citation1860–1876).

Table 1. Construction and reconstruction of cultural identity in Greece. Addition of new constituents

In we can see that in 20th century there were three more changes. The first was the upgrading of Orthodox religion to the status of greekness. This conception was articulated in the early 19th century discourse about the Greek cultural identity. The discourse started to refer to Grecochristian instead of Greek ideals which indicates an upgrading of religion.This upgrading seems to have been the result of three developments. The first was the growing religious piety as early as the second half of 19th century (K. Dimaras, Citation1998, 400–404). The second was the public awareness of the very important role played by the Greek Orthodox Church both in protecting its flock from islamisation and in the liberation revolution, as this was documented by extensive historical studies carried out during the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the war. The third was the need the Greek state felt at this time to secure the Greek Orthodox Church’s help as an ally in its fight to curb the dissemination of the communist ideology in Greece by calling the devout people to stay away from the atheist communist ideology. The upgrading of religion as a constituent of cultural identity was reflected in the upgrading of religion as a curriculum subject and the enhancement of the role of the Orthodox Church in education (Read more in chapter 6.3).

Table 2. Construction and reconstruction of Greek cultural identity

The other two added constituents were those of resistance/heroism and of pride for the modern Greek achievements.The first of the two was adopted after the Greek resistance against the Italian and German invasion in 1940 and the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s public praise(9th snd 22nd Nov.1940) of the Greek heroism.Footnote2 The second developed after the enlargement of the Greek national territory as a result of the 1910s Balkan wars and the great general progress of Modern Greece during the 20th century.

There is, however, another very interesting restructuring, that of the drop of Grecochristian ideals in the late 20th century.The change seems to have been the result of disgust and antipathy against the military junta which came to power in 1967 after a military coup. Graecochristian ideals were tarnished fatally after the Junta identified themselves with them.Very few people dare refer to them after the Junta’s fall.

5. The two contesting poles

Those who are familiar with the history of the long and gradual development of the Italian language from Vulgar Latin(13th to 19th century) can understand better the problem of the development of Modern Greek from Ancient Greek. They will wonder, however, why this development has been so difficult, divisive and traumatic in the case of Modern Greece. There are, perhaps, many explanations. The main reason, however, seems to be the consequences of the very different conditions under which the two people lived during the four centuries (15th to 19th) this development took place. In Italy people lived free from foreign oppression and were lucky to experience for three centuries (13th to 16th) the glorious times of Renaissance and then the Enlightenment, while the Greeks lived in the misery of poverty and in ignorance under the Ottoman rule. The result of this difference was dramatic. The Greeks of the 19th century when their small state was established (1829) lacked the experience of modern way of thinking and had very few material resources to live on, so they attributed enormous emphasis on their symbolic resources, the Ancient Greek language, the Ancient Greek history and the Ancient Greek texts which were glorified by the classicist movement all over Europe. It is no wonder, therefore, that those in power at that time believed strongly that the revival of the ancient Greek state was not only prestigious and honourary but also possible.

This was initially the main goal of the first pole. When this was proved impossible, it thought that it should, at least, fight for the preservation of the high culture. As we can see in , it consisted mainly of local Greek intelligentsia (Logioi), most of them professors in the country’s schools of higher education and distinguished members of the Greek Orthodox clergy, who had studied in EuropeFootnote3 and were flattered by the European philellenism and the general admiration for the cultural achievements of Ancient Greeks. Very important was also the role of the Greek diaspora, especially those from the old capital of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople.Footnote4 Their involvement played a very important role in the development of both the new born state and its education. After independence the first pole was strengthened by the State support, the establishment of the university of Athens and the School of Philosophy, which together with the Syndicate of philologists became the spearhead of the first pole.

Table 3. Contestation about cultural identity between two poles the content and strategies of the first pole

To promote its cause the first pole applied three means: a special propositional content, selected discursive strategies and effective linguistic devices.

As was to be expected, the content they chose consisted of the teaching of Ancient Greek language and texts, philosophy, Latin, Ancient Greek History and, to a lesser degree, Orthodox Religion. There were three justifications for this choice: it was believed that this content strengthened the cultural identity of both the younger and the older Greek generations, it was the high culture taught in the prestigious European schools and it was the only category of knowledge in which there were enough local trained teachers

Its discursive strategies were complex and sophisticated. They:

a) promoted a very strong narrative that this kind of knowledge was the most effective for teaching the four ideals Greece needed at that time, that is, the ideal of the Great Idea enlightening the nation, the ideal of the superiority of the Greek nation, the ideal of Great Idea, and the ideal of excellence (Persianis, Citation2016, 321). The philologists undertook the “doing” of the “proper” identity.

b) abandoned the emphasis on primary education and abolished the practical schools (agricultural, trade and normal) established by the realist first Governor of Greece Ioannis Kapodistrias.(He was assassinated in 1831(Markezinis, 51–54, 81).

c) legitimised their preferred knowledge with a strong legalisation (a series of decrees, laws, regulations, rules and circulars),

d) established the University of Athens seven years only after independence (1837). This initiative enhanced even more the hegemony of this knowledge by bestowing it with the dignity of academic status,

e) prioritised secondary education at the expense of primary, thus showing a preference for the middle class at a time when the country was still devastated by the seven year liberation war and the vast majority of the people were illiterate.Footnote5

f) established classical gymnasia, a copy of the German gymnasia, all over Greece, thus not only neglecting vocational educationFootnote6 but also strengthening the already wide youth prejudice against manual work. At the same time they offered advantages to the gymnasia graduates(higher salaries, scholarships) (Persianis, Citation2002, 125–153).

g) insisted on the extensive teaching of Ancient Greek language and texts not only in secondary but also in all the schools of higher education (Law,Medicine,Theology and Philosophy) (A. Dimaras, 1, 79).Footnote7

h) rejected the teaching of Ancient Greek texts from modern Greek translation because, they argued, this would downgrade and dilute their intellectual and aesthetic value, and objected to the use of the spoken language in the texts, even in those for the primary schools.

The last strategy was a major part of the means the exponents of the first pole used for the linguistic realisaton of their strategies. They were from the beginning very aware of the great importance of the language to this effect. Even before the independence of the country, some learned Greeks had constructed an artificial language which was a simpler version of Ancient Greek. They called it “katharevousa”, that is a “cleansed” form of language. They could not accept the popular language (demotiki) as the right language for the realization of their goals, because they thought it was very poor and mixed with many Turkish words. So, they chose katharevousa promoting it to the status of official language of the country and the language of the University. Only this form of language, in tandem with a rhetorical and pompous expository style, was considered worthy of expressing and interpreting a bright civilisation like that of Ancient Greek and rich and refined enough to enthuse the people to sacrifice their lives for their country.

The second pole (see ) consisted, in the beginning, mainly of those who were afraid of the foreign influence on the Greek identity, especially on its constituent of religious orthodoxy. These were mostly the lower clergy who could not forget the wretched role played by the Catholic Church and the Third Crusade (1204 A.D.) mobsters in the fall of Constantinople, the seat of the Orthodox Church. They were, however, unable to articulate an alternative narrative and they limited themselves to criticism.Footnote8 There were also the zealous Christians, who resisted the pro-Ancient Greek movements, because they identified the word “Greek” with paganism (K. Dimaras, Citation1998, p. 5). That is why they objected angrily to the wide practice of that time to give ancient Greek names instead of Christian to new born children((K.Dimaras, Citation1998, 58–60}.The second pole became articulate about 70 years after the first pole (in the 1820s) and acquired critical mass and self awareness after another 70 years (1890). As it was already said, Its first exponent was the Greek poet of the Greek national anthem D. Solomos who was a strong supporter of the popular language. He believed that language was as “important for the Greek people as freedom” (Solomos: 478–495).

Table 4. Contestation about cultural identity between two poles.The content and strategies of the second pole

The second pole became active in the early 20th century, especially after the ascent to power of liberal governments (E.Venizelos) and the crushing defeat of the Greek army in Asia Minor in 1922, which led to the demise of the “Great Idea” and the national arrogance. The defeat made the members of the second pole feel vindicated. At this junction they were joined by democratic governments and modern intelligentsia, especially those who supported the popular language as the right form of language not only as a medium of instruction but also as the language of literature, the sciences and administration. Very essential were also the contributions of the founders of the Educational Group Demetris Glinos and Alexandros Delmouzos and of the new university established in Salonica in 1925. It was during this period that demotiki acquired social, ideological and political status.

The spearhead of the second pole, however, were a group of philosophers, intellectuals(G.Theotokas) and authors (novelists, among them N. Kazantzakis), poets (among them the Nobel Prize winner George Seferis) who are known as “the generation of the thirties”. This group’s greatest contribution was the discourse they started about the “identity of hellenism” which, in their view, should include elements not only from Ancient Greece but also from all the other layers of the Greek history (byzantine and modern) and culture. including the tradition and the popular culture and, of course, European civilisation. This development was a great help to the democratic governments’ struggle to introduce demotiki as medium of instruction through the publication of the first Readers in it (see chapter 6.1).

The strategies the second pole applied were the following:

a)they supported the establishment of vocational and technical secondary schools in a move to defeat the parents’ deep prejudice against manual work and to solve the wide problem of youth unemployment. To this effect, they established in 1925 a new university, the university of Salonica, whose Constitution prescribed the need to put emphasis on the teaching of the technical and applied sciences (Persianis, Citation2002, 236–237).

b)they insisted on the teaching of demotiki. To upgrade it, they accepted the borrowing of words and phrases from katharevousa and Ancient Greek and codified it with the construction of a proper Grammar and Syntax for it in order to curb its fluidity.

c) they presented the Ancient Greek language and the Ancient Greek texts as dead and the education they offered as “pseudoclassicism, monolithic and unrealistic”, because it was not a preparation for life (Bouzakis,63).Footnote9

d) they insisted that the way Ancient Greek language and civilization were taught at schools was artificial, pedantic and foreign to the Greek mentality. Very influential in this context was the Nobel prize winner Odysseas Elytis’ criticism that the way of understanding the ancient Greek culture and civilization was wrong because it was a blind imitation of the foreign example. He wrote:

We must see Greece through a Greek eye, not through a European one. Until today we have been seeing Greece the way Europeans taught us to do it.

e) they pointed that the content, the structure and the organization of education was undemocratic in the same way the whole political and economic administration was. Odysseas Elytis argued:

One could say that from the first day of the establishment of the Greek state until today, the political administration has been planned and executed irrespective of the notions about life and, in general, the ideals the Greek nation have formed within their sound community organisation and the tradition of their great struggles for independence (Elytis, Citation1958).

The greatest advantages of the second pole were the liveliness and vividness of the language they used and, of course, their realistic pursuits. They were looking to the future in contrast to the first pole which was oriented to the past. That is why they finally won.

6. The areas of major conflict

As has already been said, the educational conflict focused mainly on three areas: the language of the Readers in primary education and the language and content of school textbooks, the excessive emphasis on Ancient Greek and the parallel downgrading of Modern Greek in secondary education, and the role of the Orthodox Church in the construction of cultural identity and the status of Religion in the curriculum.

6.1 The language of the readers in primary education and the language and content of school textbooks

For reasons already explained, language was a very controversial topic in Modern Greek education so much so that it provoked bloody public demonstrations. In 1901 the School of Philosophy students staged a demonstration against the publication of a translation of the Gospel into Modern Greek in a Greek newspaper (Evangelika) and in 1903 they staged another against the translation of the Aeschylus trilogy Oresteia demanding the interruption of the theatrical performance (Oresteiaka) (Bouzakis, 60).Footnote10 Eighteen years later a reactionary government ordered the burning of the Readers in demotiki which had been introduced two years earlier by a progressive government (Bouzakis,60; A. Dimaras,2,130–131,290).

The full control of school textbooks has been the policy of all Greek governments without exception. They have all insisted on a full control of not only the curricula and the syllabi but also their language realisation. The wording and phraseology were considered very critical and the educational authorities wanted them to be fully in line with the official narrative. It is obvious that knowledge for them was “teacherproof” and that there was extensive rote learning and formalism. In addition to the feeling of insecurity,the strict control was also the result of the Orthodox Church epistemological view about the existence of only one truth and therefore need for only one source. In order to achieve this homogeneity, the educational authorities established a public organisation which they charged with the publication of officially approved school textbooks. The result of this practice was that in 20th century, when conservative and progressive governments alternated, the textbooks were each time withdrawn and replaced. There was even a case in 1965 when the reactionary government ordered their shredding (Bouzakis,60, A. Dimaras, 2,130–131,161, 290).

6.2. The emphasis on the teaching of ancient Greek

The degree of emphasis on the teaching of Ancient Greek, especially in comparison with that on the teaching of Modern Greek, was also very controversial.

As we can see in , there is a tremendous difference in the emphasis on the teaching of Ancient and Modern Greek. The time devoted to the teaching of Ancient Greek ranged from 31 to 52 hours per week, that is from 27.1 to 40.3 per cent of the teaching time, while that devoted to the teaching of Modern Greek ranged from 2 to 6 periods per week, that is from 1.5 to 4.2 per cent. Another discrimination against the latter was that its teaching started almost a whole century later.

Table 5. Ancient Greek teaching hours per week

Table 6. Teaching of modern Greek in a six-year gymnasium

The accepted explanation of this paradox is the fallacy of that time Greek politicians that the teaching of Ancient Greek was the only way for the country to progress. This line of reasoning was based on the strong belief that the means through which the Europeans progressed so much was their initiative to devote much school time for the study of Ancient Greek language and texts. Modern Greeks, the politicians argued, had two additional reasons to do that, first, they were descendants of Ancient Greeks and, therefore, more entitled to do the same and, second, this content of education was compatible with the established policy of borrowing “the lights of Europe”. In view of the postmodern theories about cultural identity, however, it might be argued that the most important reason for this policy has been the Greeks’ emphasis on otherness and, more specifically, their obsession about being a chosen nation, very different from their neighbours, Turks and Balkans. A very strong evidence of this line of thinking is the following extract from a Greek philosopher’s statement:

If Modern Greeks had not had even this deficient knowledge of Ancient Greek, they would have turned into one more Balkan race. Greece exists as a reality and as an idea. A hundred years ago Greece was much bigger as a reality, even fifty years ago. At that time all Europeans knew Ancient Greek. Therefore, there has been a diminution of Greece. (Ioannis Theodorakopoulos, Citation1976).

The emphasis on otherness is, according to the following two Stuart Hall’s conclusions, very dominant in cultural identity construction scenarios:

There is no identity that is without the dialogic relationship to the Other. The Other is not outside but also inside the self, the identity (Hall, Citation1996a, 345).

It is only through the relation to the Other, the relation to what it is not, to precisely what it lacks, to what has been called its constitutive outside that the positive meaning of any term – and thus its ‘identity’ - can be constructed (Hall, Citation1996b, 4-5).

The differentiation from the other Balkan nations has been a very strong motivation for modern Greeks to work hard not only for the reconstruction of their backward and poor country but also for the fulfillment of the “Great Idea”. This need for differentiation was also most probably one of the reasons they hurried to establish in Athens the first university in the Balkan peninsula (K. Dimaras, Citation1989, 44).

There was, however, at some time, a practical expediency for the great emphasis on the teaching of Ancient Greek. When the gymnasia, the elitist schools of Greece which led to the universities and upward social mobility, started to produce a surplus of graduates and there was a problem of unemployment, Ancient Greek and especially its Grammar and Syntax provided the necessary for selection structured and hard knowledge in the public examinations since mathematics and science teaching was very limited in both time and space. This use was also an argument against the teaching of Ancient Greek texts from modern Greek translations (Persianis, Citation2002, 61–70, 203).

6.3 The role of the Greek Orthodox Church in the construction of Greek cultural identity and in formulating the educational policy

The de facto proclamation of independence of the Orthodox Church of Greece from the Oecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in 1833 did not affect its moral and cultural power, despite the fact that the Patriarchate refused to accept it until 1850.The schism was avoided because the Church leaders managed to convince the majority of independent Orthodox Churches and influential people of the country that it was unthinkable for the Church of Greece to remain dependent on an institution which had its venue in the capital of the Ottoman state and, therefore, vulnerable to its whims and interventions (Markezinis,1,119,197).

The Orthodox Church retained to a great degree its power in education, because Orthodox religion was recognised as the formal religion of the country and the Ministry of Education became also Ministry of the Orthodox religion. The state continued to employ priests as teachers, as in the time of Turkish rule and supported the practice with the establishment of 13 church schools which later became normal schools for priest-teachers. The state also provided its strong support to the enhancement of the subject of Religion in the curriculum. From 1836 to 1871 the state sent several circulars to the schools commanding them to pay special attention to its teaching.Footnote11 This state support to the Church misled some bishops to believe that they could continue to have the role of school overseer as they did during the Ottoman rule. The most well-known such case was “Atheika” (the Atheism Case) in which a bishop accused the progressive headmaster of the Volos Girl High School A. Delmouzos of neglecting the teaching of Religion. The case ended up in court (1914) (Bouzakis,63, A, Dimaras, 2,127). The episode was a strong blow to the Church’s respect among teachers.

In the 21st century there were two serious cases of conflict between Church and State. The first was in 2000 between the Archbishop of Athens Christodoulos and K. Semitis Government over the statement of individuals’ religious affiliation in their identity cards. The Archbishop objected to the government’s decision to abolish this practice, on the ground that religion was an essential constituent of the Greek identity contributing to national cohesion and, therefore, important to be underlined through its statement in the cards. The Government, however, was uncompromising, insisting that such a statement was a violation of the individual right to have one’s personal data protected (Misiakoulis, Citation2008).

The second conflict was in in Nov, 2016 between the Minister of Education N.Filis and the Archbishop Ieronymos over the reduction of the teaching periods for Religious education in the public schools and the change of its syllabus. The Archbishop lobbied the Prime minister and secured the recall of the Minister’s plan, while the Minister was sacked.

Thus, it could be said that, by and large, the Greek governments, even the leftist, showed respect to the Church of Greece petitions, probably because the majority of the Greek people are still very religious.Footnote12 This, perhaps, explains why the subject of Religion, despite suffering drastic trimming in teaching periods in 20th century, has retained much of its high status. Throughout the 19th century it was taught 6 to 7 periods per week in both the Hellenic Schools and the Gymnasia (6.1–6,8%), which was more than the time allocated to the teaching of Modern Greek throughout the 19th century. From 1884 to 1897 the teaching periods increased to 8. In 1929, however, the E. Venizelos liberal Government slashed the periods to 2 in order to find space for the new subjects, especially sciences and mathematics which were neglected throughout the 19th and the first quarter of the 20th century (A.Dimaras,2,175).To compensate for this reduction, both the E. Venizelos’ government and all those which followed retained the practice introduced in 1897 to list Religion first in the school subject programme (Persianis, Citation2002,72, 175).

7. The 1976/1977 hybrid educational reform and the present situation regarding cultural identity

The contestation lost its intensity and fanaticism after the fall of the military Junta and the restoration of democracy in 1974. The psychological impact from this development was so strong that it allowed the production of what Fairclough and Wodak (Citation1997, p. 276) could call “context of possibilities” for the promotion of a compromising discourse.

The change started with Constantinos Karamanlis drastic constitutional changes including the abolition of kingship. New laws were enacted and new institutions were established which provided new liberties (Persianis, Citation1978). The people felt that a new day of more liberal administration was dawning upon Greece and they wanted to make a new start. In this new period education continued to be a first priority for both poles because of the need for Greece to make as quickly as possible big strides towards scientific and technological progress to catch up with the other European countries. This was the spirit that led the liberal G.Rallis government to introduce in 1976/1977 a hybrid educational reform which enacted a compromise solution in the basic problems that divided the people for more than two centuries.

The hybrid solution was essentially the result of the first pole yielding to the new realities. In actual fact, the 1976/77 Reform Act was in many ways a restoration of the reform introduced by the centrist G. Papandreou government in 1964 and overturned by the rightist governments that followed (Bouzakis, 116–120). The Reform Act was warmly welcome. The great majority of citizens felt that it was pointless to continue the old contestation over education There were already a great number of substantial social, cultural and political changes which led to a broad compromise. There were also less and less people who studied Ancient Greek and less and less people who understood katharevousa, The media, the scientists and the lawyers used demotiki, the bills were drafted in demotiki, the literature was written almost exclusively in demotiki, the administration was conducted in demotiki. Thus, the educational solution was, in some way, imposed by the language developments. As Bouzakis comments, in 1976/7 the country moved from educational reforms to educational change (Bouzakis,110–168).

The two poles,however, now mostly political, right-wing, liberal and pro-west the first,and leftist,introvert and anti-west the second, and the contestation over the right content of education and the proper ways of maintaining a strong Greek cultural and national identity are still there. National insecurity is also still persisting, despite the geopolitical developments that took place in the last sixty years(Greece became a member of NATO in 1952 and of EU in 1981). The insecurity reveals itself very often and in many ways, especially in the form of protesting against their country’s dependence on the West(USA and EU).

The most recent example of national insecurity is the latest episode in the 25 year old dispute of Greece with Its neighbour FYROM (Former Yugoslavian Republic of Macedonia) over the use of the name of Macedonia. Many Greeks believe that this is not only a usurpation of the Greek name Macedonia but it also betrays the FYROM’s irredentist aspirations included in its Constitution. On 17 June 2018 the governments of the two countries, yielding to NATO pressures, signed an agreement about changing the name of FYROM to Northern Macedonia and abolishing the irredentist articles of FYROM’s Constitution. Nevertheless, the agreement provoked angry reactions among the Greek people, especially the inhabitants of Greek Macedonia. It looks that a considerable part of the Greek population have still great expectations from the symbolic resources of the nation despite the fact that its material resources have tremendously grown over the last forty years.

8. Conclusions

My conclusions from this piece of research are the following:

1. Postmodern theoretical accounts about nationhood and cultural identity can contribute to the opening of a new window in the study of the history of education of Modern Greece and in the process of national self-knowledge. We have now a more analytical tool to help us understand a) the role of cultural identity in the development of education, b) the kind and the role of discourse that may be developed about these topics and c) the discursive strategies and means that may be employed in various circumstances.

In the case of Modern Greece the problem of the role of cultural identity has been very complicated because of three reasons: first, the awareness about the very rich culture of Ancient Greece and the world respect and adoration that it sparked at the time of the Renaissance, second, that this awareness coincided with the establishment of the state of Modern Greece and the possibility that emerged of making a new start in the cultural identity of the country and, third, the fact that the country at that time was very backward as a result of an occupation that had lasted for nearly four centuries. The thought of reviving an ancient civilization after almost two thousand years was surely a fallacy but it happened at a time of a romantic conception of the world and admiration for ancient civilisations, tradition and culture.

2. Very enlightening to this respect are the constituents of the Greek cultural identity presented in chapter four. Almost all of them refer to the history of the country. None of them is relevant to its future, to the qualities and abilities needed for the building of a country and for the people making their living, coexisting with their neighbours and creating a Modern Greek civilisation. The reason for this is probably historical. As the historian K. Dimaras explains, the Greek people adopted the Enlightenment “unprepared”, that is, without experiencing the training of the European Rennaissance, and at a time it was governed by an Asian conqueror (K. Dimaras, Citation1998, 2).This reason, perhaps, seems also to explain “the educational and political formalism” of Modern Greeks which professor N. Mouzelis regards as a sign of underdevelopment (N. Mouzelis, 5).

3.It is very interesting that the problem of identity is today becoming topical in Greece through the publication of books like those of G. Dertilis and recently of the book of the Sorbonne Professor G. Prevelakis under the title Who we are: Geopolitics of Greek identity. In his book Prevelakis underlines the urgent need for Greek policy makers to have in mind that Greece is today “light years away from the time of Paparrhegopoulos and Venizelos” and that they must stop ”to be captive of old designs” (Prevelakis, 17). He also argues that the case of Modern Greece is the opposite to that of USA, as it is presented by Samuel Huntington in his book Who are We? In his words,“Samuel Huntington was concerned about America’s excessive opening to the others. In the case of Greece the decline is the result of excessive closing” (Prevelakis, Citation2016, 26).

4.National insecurity can also explain the very limited dialectic allowed in Greece between ‘the things inside’ and ‘the things outside’ of the schools. The phenomenon of ‘the insertion of history(society) into a text and of this text into history’, which Kristeva (Moi, Citation1986, 39) describes, that is, of the mutual influence between outside reality and what is taught in the schools, is limited in Greece because of the strict control of the content of education, the fanaticism, the frequent accusations of treason and acts of political violence.

5.Finally, this situation can also explain why in this time of globalisation and materialism national identity remains strong in Greece and almost untouched by some postmodern ideas about the end of nationalism. The results of the 2018 Pew Research Center in 34 countries (see note 1) are very indicative.

Declaration of interest conflict

I do not have any conflict interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

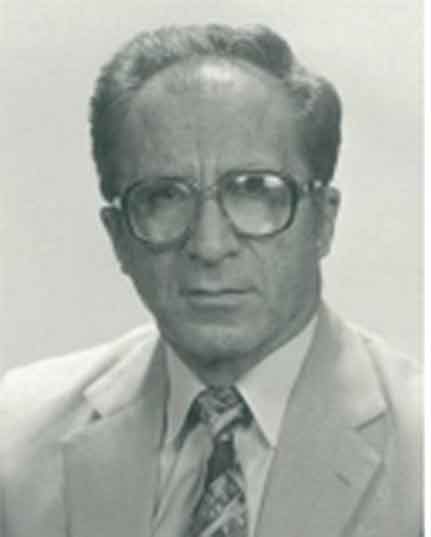

Panayiotis Persianis

The author’s research interests have been some historical and comparative aspects of the Cyprus and Modern Greek educational systems. In 1978 he published a book titled Church and State in Cyprus Education in which he analysed the main aspects of the conflict between the British Colonial Administration of Cyprus and the leaders of the Orthodox Church over the control of teachers and curricula of the education of the Greek community of Cyprus. A special aspect of this problem was also discussed in an article published in 1996 in Comparative Education (32,1 45-68). Regarding the Greek educational system, the problems caused by the cultural schism and the repeated demise of the educational reforms were discussed in a book titled The Educational Knowledge in Greek Secondary Education (1833-1929) (2001) and in an article published in Comparative Education (34, 1,71-84) respectively. The present report is an effort for a deeper understanding.

Notes

1. A 2018 Pew Research Center Report based on demographic studies in 34 countries of Western, Central and Eastern Europe among 56,000 adults from 2015 to 2017 found that 89% of Greeks believed that their civilisation is the most important. Next in the list were the Armenians(84%), the Germans(45%)and the French(36%)(Pew Research Center, Citation2018).

2. The British Prime Minister Winston Churchill praised publicly the Greek heroism on 7th and 22nd Nov.1940 (Despotopoulos & [History of the Greek Nation], Citation1978,15,455).

3. Two of the first four Deans of the University of Athens, those of the School of Philosophy and the School of Theology, were clergymen (K. Dimaras, Citation1989,,46).

4. The diaspora’s contribution was very important both in enlightening the enslaved Greeks about their old glory and in financially supporting secondary education. It has been estimated that its financial contribution during the years 1830–1880 was much greater than that of the Greek state(Tsoukalas,488).

5. Statistics of 1901 show that only 8,3% of the children aged 6–10 attended a school and of 1907 that 50.2% of men and 82% of women were illiterate (Bouzakis, 61).

6. The result was that in the school year 1912–1913 Greece had proportionally the highest numbers of secondary and higher school students in Europe (Bouzakis, 61).

7. According to article 20 of the University of Athens constitution, all the students were required,among others, to write an essay on a topic of their specialization in Ancient Greek. in their final examination (A Dimaras,1, 79, 115 − 118).

8. One of them described the early foundation of the University of Athens in 1837, at a time that the country had very few primary and secondary schools, as”charlatanisme’(A.Demaras,1,87–90).

9. D.Glinos published a book in 1925 under the title Un Unburied Dead (Bouzakis, 57).

10. In this demonstration 8 people were killed and 80 injured (Bouzakis, 60).

11. An 1871 circular ordered the headmasters to refuse to promote students to the next grade if they lagged behind in the subject of Religion (Persianis, Citation2002).

12. The 2018 research conducted by Pew Research Center (see note 1) found that 92% of the Greek citizens stated they believe there is a God and 76% that being Christians makes them real Greeks

References

- Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso.

- Benwell, B., & Stokoe, E. (2006). Discourse and Identity. Edinburgh University Press.

- Bhabha, H. K. (1990). ”Narrating the nation”. In H. K. Bhabha (Ed.), Nation and Narration. Routledge.

- Bouzakis, S., [Modern Greek Education,1821-1998]. (1999). Neoelliniki Ekpaidefsi, 1821–1998.

- Dertilis, G. V. (1999). Paideia ke Istoria [Paideia and History]. Kastaniotis.

- Despotopoulos, H. (1978). I istoriki semasia tou ellinoitalikou ke ellinogermanikou polemou. In Istoria tou Elinikou Ethnous [History of the Greek Nation].Vol. 15 455.

- Dimaras, A., [The reform that did not materialise]. (1973/1974). I Metarrithmisi pou den egine.

- Dimaras, K., Apo tis protes rizes os tin epohi mas [History of Modern Greek Literature. From the first roots to the present]. (1964). Istoria tis Neoellinikis Logotechnias. Ikaros.

- Dimaras, K. (1989). Ideologimata stin afetiria tou Ellinikou Panepistimiou‘’,sto S.Masdrachas (Ed), Panepistimio: Ideologia ke Paideia. Istoriki Diastasi ke Prooptikes, 43–54 [ideological statements at the beginning of the Greek university. University: Ideology and Paideia. Historical Dimension and Prospects] S. Asdrahas, (Ed.), Istoriki diastasi ke Prooptikes. New Generation General Secretariat.

- Dimaras, K. (1998). Neoellinikos Diafotismos [Modern Greek Enlightenment]. Hermes.

- Elytis, O. 1958. Elefthera, 15 June 1958.

- Fairclough, N., & Wodak, R. (1997). ‘’Critical discourse analysis”. In T. Van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse as Social Interaction. A multidisciplinary Introduction. Sage.

- Fallmerayer, J. P., History of the Morea Peninsula during the Middle Ages. (1830). Geschichte der Halbinsel Morea wahrend des Mittedlalters. Stuttgart.

- Frankoudaki, A. (1992). Educarional Reform and Liberal Intellectuals. Kedros.

- Hall, S. (1996a). ‘’Ethnicity: Identity and difference”. In G. Eley & G. Suny (Eds.), Becoming national: A reader. Oxford University Press.

- Hall, S. (1996b). Introduction: ‘’Who needs identity? In S. Hall & P. D. Gay (Eds.), Questions of cultural identity. Sage.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. (1992). Nations and nationalism since 1780: Programme,myths,reality.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.‘

- Karamanlis, K. (Prime Minister of Greece) (1976). Statement in the house of representatives. Minutes of the Greek Parliament, 12 June 1976.

- Kazamias, A. (1995). ‘’I Katara tou Sisyphou. I vasanistiki poreia tis ellinikis ekpaideftikis metarrythmisis”[‘’The Sisyphos Curse: The tormenting course of the Greek educational reform”. In A. Kazamias & M. Kassotakis, [Greek Reform: Prospects for Reconstruction and Modernizatio] (Eds.), Elliniki Metarrythmisi:Prooptikes Anasynkrotisjs ke eksighronismou.

- Klerides, E. (2009). ’National cultural identities, discourse analysis and comparative education. In International handbook of comparative education. London: Springer Science and Busineess Media.

- Kristeva, J. (1986). Word, dialogue and novel. In Moi, Ed.. The Kristeva Reader. Basil Blackwell.

- Markezinis, S., [Political History of Modern Greece]. (1966). Politiki Istoria tis Neoteras Ellados. Papyros.

- Misiakoulis, K. (2008). Viographikon- Ergographikon Simioma Makariotatou Archiepiskopou Athinon ke Pasis Ellados Christodoulou[Biographic-Ergographic note of his Beatitude the Archbishop of Athens and Greece Christodoulos. Church of Greece Official Bulletin.

- Mouzelis, N. (1978). Modern Greece: Facets of¨Underdevelopment. Macmillan.

- OECD. 2017.Education policy in Greece: A preliminary assessment. http://www.oecd.org/education/Education-Policy-in-Greece-Preliminary-Assessment-2017.pdf

- OECD. 2018. Education for a Bright Future in Greece. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/education-for-a-bright-future-in-greece_9789264298750-en#page4

- OECD.1997. Review of national policies for education: Greece. OECD. http://www2.statathens.aueb.gr/~jpan/oereview.html

- Ozkirimli, U., Theories of Nationalism. (2000). A critical introduction. Palgrave.

- Paparrhegopoulos, C. (1860–1876). Istoria tou Ellinikou Ethnous apo ton archeotaton chronon mechri ton neoteron [History of the Greek Nation from the very ancient times to the modern] (Vol. 5).

- Persianis, P. (1978). “Values underlying the 1976-1977 Educational Reform in Greece. Comparative Education Review, 22(1), 51–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/445958

- Persianis, P. (1998, March). “Compensatory legitimation in Greek Educational Policy: An explanation for the abortive educational reforms in Greece in comparison with those in France”. Comparative Education, 34(1), 71–84. 1998. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03050069828351

- Persianis, P. (2002). I Ekpaedeftiki Gnosi sti Defterovathmia Ekpaidefsi tis Elladas (1833-1929) [The Educational Knowledge in Greek Secondary Education (1833-1929)]. Atrapos.

- Persianis, P. (2016). I prosfora ton philologon kai tis philologias stin Kypro tous telefteous dyo eones [The contribution of philologists and philology in Greece and Cyprus during the last two centuries. In Stasinos (Vol. 15, pp. 315–336). Nicosia:Stasinos.

- Pew Research Center,2018. Survey reports, demographic studies and data-driven analysis.Internet&Tech.December,2.10,2018. https://www.pewreseach.org/category/publications

- Prevelakis, G. (2016). Poioi EimasteGeopolitiki tis Ellinikis Taftotitas[Who we are. Geopolitics of the Greek identity].Economa Publishing.

- Solomos, D. (1824). Dialogos, [Dialogue]. In N. Tomadakis (Ed) (1954), Dionysios Solomos Basic LibraryVol. 15 Aetos.156–171.

- Theodorakopoulos, I. 1976.‘’Interview to Kathimerini, Kathimerini, 13 Feb.1976.