Abstract

Entrepreneurial intention plays a central role in stimulating the growth of entrepreneurs. The purpose of this investigation is to explore the relationship between several forecasted variables that can drive to students’ entrepreneurial intention, consisting of entrepreneurial education, entrepreneurial attitude, family education, and environment. We applied a quantitative approach with a cross-sectional survey model to capture the digestion of how entrepreneurship education, family education, environment, and entrepreneurial attitude can explain the entrepreneurial intention of vocational students. This research used a convenience sample of vocational students in Malang of Indonesia and was analyzed undergoing Structural Equation Modelling Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS). This work confirms that students’ environment can explain the intention and students’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship. However, this study failed in explaining the role of entrepreneurship education and family education informing intention instead of stimulation students’ entrepreneurial attitude. This study’s surprising finding can be an initial opportunity to elaborate an appropriate model of entrepreneurship education for vocational schools.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Entrepreneurship plays a crucial role in promoting new job opportunities, and the vocational graduates are expected to gain the number of entrepreneurs in Indonesia. However, the educational model, environment, and family involvement have been crucial variables in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and attitudes. The findings are surprising since the entrepreneurial education failed in promoting students’ entrepreneurial intention. This study helps the government and schools evaluate the entrepreneurship education model that elaborates students in more practical activities instead of theoretical in the classroom.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a growing public concern worldwide, and it has gained scholars’ attention from around the world (Keyhani & Kim, Citation2020; Ratten & Jones, Citation2020). The underlying rationale is that entrepreneurship can drive the development of economic and social welfare (Hechavarria et al., Citation2019; Sergi et al., Citation2019). Some scholars claim that education can shape entrepreneurship (Handayati et al., Citation2020; Pisoni, Citation2019; Saptono et al., Citation2020). Additionally, CitationKaryaningsih et al. () agreed that entrepreneurial education takes a pivotal part in enhancing entrepreneurial passion, spirit, and behavior among the youth population. Accordingly, Cui et al. (Citation2019) noted that entrepreneurship education could outline the mindset, attitudes, and behavior of students to be entrepreneurs as an opportunity for career options.

In addition to entrepreneurship education, the family also takes a primary role in provoking personal entrepreneurial intentions. Lingappa et al. (Citation2020) agree that family and its socialization influence entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions. Indeed, Hisrich et al. (Citation2008) noted that four factors influence entrepreneurial characteristics, namely education, personal value, age (explained about the childhood family environment), and work history. It can be interpreted that the family environment during childhood with the role of parents can affect the formation of an entrepreneurial spirit and the intention of being entrepreneurship in the future. Rasyid (Citation2015) added that parents’ experience is an encouragement in the form of an opinion on something based on their knowledge and experience, which is useful for providing input so that it ultimately affects the decisions to be taken.

As a developed country, Indonesia also campaigns to enlarge the number of entrepreneurs due to its insufficient supply. Based on Global Entrepreneurship Index (GEI) data, Indonesia is still ranked 94th out of a total of 137 countries observed, far below Singapore (27), Brunei Darussalam (53), and Malaysia (58) (Saptono et al., Citation2020). Dealing with this matter, the Indonesian government has made various breakthroughs. One of them is by revitalizing entrepreneurship education in vocational high schools (Wardana et al., Citation2020). Unfortunately, the revitalization of entrepreneurship education at vocational high schools has not shown positive results. Vocational high school graduates still dominate the proof, the number of unemployed. Based on data from Statistics Indonesia (BPS), vocational high schools still contributed the highest to unemployment among other education levels, amounting to 8.49 percent (BPS, Citation2020).

Data on the increase in the number of unemployed from vocational school graduates, allegedly due to ineffective entrepreneurship education (Wahzudik, Citation2018). However, when entrepreneurship education is provided effectively, instilling creativity and innovation will significantly influence vocational students’ intention to become entrepreneurs. Several antecedents work demonstrated that entrepreneurship education has the prospective to promote a person’s intention to become entrepreneurs (Marini & Hamidah, Citation2014).

Recently investigators have examined factors that strengthen vocational students’ intention and recommendation that entrepreneurship education plays an essential role (Kim & Park, Citation2019; Li & Wu, Citation2019). Additionally, some studies focused on self-efficacy and intention (Shahab et al., Citation2019; Santos & Liguori, Citation2019). In the context of family, Ratten et al. (Citation2017) were concerned with parenting style, ethnic origin, and emotional intelligence. However, few scholars have been able to draw on any systematic research into the role of family education and environment that affecting attitude and intention of being entrepreneurs.

The contribution of this research is twofold. First, the contribution of literature by elaborating the role of family and environmental education, which is missing in the antecedent studies as the predictor of attitude and intention. Second, this work complements previous studies regarding the role of entrepreneurial attitudes that effectively mediate the effect of family education on entrepreneurial intentions (Kusumojanto et al., Citation2020; Purwana & Suhud, Citation2017; Ratten et al., Citation2017). This study helps government have better performance through an effective entrepreneurship education that can stimulate the growth of entrepreneurs in Indonesia.

This paper has been proposed in the following way. This paper first gives a brief overview of the study’s novelty, followed by explaining the hypothesis development. The third section concerns the methodology used for this study. The fourth contains the findings of the work, focusing on the variables studied. The last section consists of a conclusion, including the limitation and suggestions for further scholars.

2. Literature review

2.1. Entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention

Recent developments in education have heightened the need for entrepreneurship since its crucial role in forming attitudes, behavior, mindset, and intention of being entrepreneurs (Alshebami et al., Citation2020; Olugbola, Citation2017). Similarly, Jena (Citation2020); Bazkiaei et al. (Citation2020) remarked that entrepreneurship education prepares students to initiate new businesses by integrating experiences, skills, and knowledge. Meanwhile, Din et al. (Citation2016) believed that entrepreneurship education is more effective in business schools instead of in the government schools. The fundamental reason is that innovative and attainable business ideas tend to establish from technical, scientific, and creative studies.

Entrepreneurial intention briefly brings up a thought that directs individual actions to undertake or create new, creative, and unique businesses through exploiting business opportunities and taking risks (Linan et al., Citation2011). An action or starting a business that begins with the intention will have better readiness and progress in the business being carried out than someone without the intention to start a business. Kolvereid and Isaksen (Citation2006); Zhao et al. (Citation2005) reveal that entrepreneurial intention is measured by indicators: involvement in entrepreneurship programs on campus, starting self-employment after graduation, working with partners.

The association between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intentions is theoretically performed by Ajzen’s Planned Behavioral theory (1991); Shapero and Sokol (Citation1982). The determining component of educational activities will lead the intention to perform entrepreneurial behavior (Ahmed et al., Citation2017; Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2015). The findings of Saptono et al. (Citation2020) strengthen the correlation between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intentions, which refers to the entrepreneurial human capital theory (EHC). This theory points out that human capital is an essence that acts a pivotal role in promoting individual entrepreneurial intentions (Jogaratnam, Citation2017). Furthermore, Brush et al. (Citation2017) noted a robust correlation between entrepreneurial education and human capital achievement. Some scholars, Souitaris et al. (Citation2007); Gurbuz and Aykol (Citation2008) revealed that entrepreneurship education is measured by indicators of entrepreneurial knowledge, values, motives, social interaction, and entrepreneurial abilities.

H1: Entrepreneurial education has a positive impact toward entrepreneurial intention

2.2. Entrepreneurial education and attitude

Rosmiati et al. (Citation2015) argued that attitude is mental readiness in several right action forms on something and how people respond to condition and regulate in their life. Kurczewska (Citation2011) suggested that entrepreneurial attitude is a tendency which involves three main domains including cognitive, affective and conative of individuals that drives to discover, initiate, apply a unique way combining technology and products by increasing efficiency by providing exemplary service to obtain a more significant profit.

The attitude of entrepreneurial students is influenced by entrepreneurship education. Keat et al. (Citation2011) remarked that the main objective of entrepreneurship education aims at changing the views, behavior, and interests of students in order to understand entrepreneurship, have an entrepreneurial mindset and later become successful entrepreneurs in building new businesses as well as promote new job opportunities. S. Wu and Wu (Citation2008) noted that entrepreneurship education significantly affects a person’s attitude to entrepreneurship. Yang (Citation2013) viewed that individuals who show a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship tend to perform as entrepreneurs and agree that entrepreneurship is not just a method of survival but a way to achieve self-actualization.

H2: Entrepreneurial education has a positive impact toward entrepreneurial attitude

H9: Entrepreneurial attitude mediates the connectivity between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention

2.3. Family education and environment

According to Gronhoj and Thogersen (Citation2017) mentioned that the family environment, especially parents, will provide a cultural pattern, home atmosphere, life view, and patterns that will determine children’ attitudes and behavior. Having parents who are independent or entrepreneurial-based, the independence and flexibility of the parents will stick with their children since childhood (Randerson et al., Citation2015). Parents who have their own business will brace and reinforce independence, accomplishment, and obligatory for their children (Olugbola, Citation2017). Then an attitude of independence will grow and encourage an individual to have their own business. Additionally, culture and entrepreneurial attitudes are influenced by family and its socialization (Igwe et al., Citation2018; Osorio et al., Citation2017).

Parents’ support can promote their children entrepreneurial behavior (Rachmawan et al., Citation2015). Similarly, Staniewski (Citation2016), students who have parents who are entrepreneurs and who receive entrepreneurial knowledge at a young age will form attitudes and perceptions about self-efficacy of entrepreneurial readiness. The role of parents in fostering the entrepreneurial spirit of children, including with conducive communication in the family environment, training in responsibility for domestic work, training in leading or managing events that occur in the home environment, and encouraging children to be active in activities in their social environment (Houshmand et al., Citation2017).

Some preliminary studies believed that parents’ background affects students’ entrepreneurial intention. For example, Van Auken et al. (Citation2006); Farrukh et al. (Citation2017) found that family entrepreneurial family supports and backgrounds positively affect their students’ entrepreneurial intention in Pakistan. Despite this, the study of Marques et al. (Citation2012) demonstrated that the entrepreneurial engagement of family members harmed student intentions in Portuguese. We have a strong argument that parents’ resilience when doing entrepreneurship is an inspiration as well as a real example so that students are interested in becoming entrepreneurs.

The environment in this study covers the school and family environment. Kirkley (Citation2017) stated that school or education is a very strategic place to cultivate entrepreneurial talents. Several reasons formal schools can foster entrepreneurial talents, namely: First, schools are educational institutions that are highly trusted by the community for a better future. Second, the network already exists in all corners of the country. Third, through school, it can also reach and influence the families of students (Jabeen et al., Citation2017; Z. W. Wu & Zhu, Citation2017).

Family is the closest social environment of an entrepreneur, which acts a great role in forming character, including the entrepreneurial character of a child. Jufri et al. (Citation2018) remarked that the family environment has a huge role in preparing children to become entrepreneurs in the future. It is the family that is initially responsible for the education of the children so that the family can be said to be the foundation for the pattern of behavior and personal development of the child. The family environment can be a conducive environment to train and hone entrepreneurial characters, which can provide provisions for children to start directing their interests later on. In this family environment, a child gets entrepreneurial inspiration and support from the family, and there are activities in the family that mean learning entrepreneurship (Jayawarna et al., Citation2014).

H3: Family education has a positive impact toward entrepreneurial attitude

H4: Family education has a positive impact toward entrepreneurial intention

H5: Environment has a positive impact toward entrepreneurial attitude

H6: Environment has a positive impact toward entrepreneurial intention

H7: Environment has a positive impact toward entrepreneurial education

H8: Entrepreneurial attitude has a positive impact on entrepreneurial intention

H10: Entrepreneurial attitude mediates the connectivity between family education and entrepreneurial intention

H11: Entrepreneurial attitude mediates the connectivity between environment and entrepreneurial intention

3. Materials and method

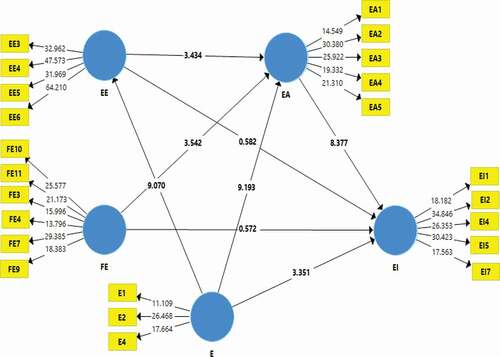

This study involved a cross-sectional survey method to gain a comprehensive information of how entrepreneurial education, family education, environment, and entrepreneurial attitude correlates with students’ entrepreneurial intention (see ). The dependent variable adopted in this work is entrepreneurial intention (EI), whilst entrepreneurial education (EE), family education (FE), environment (E), and entrepreneurial attitude (EA) predicated as the independent variable.

3.1. Sample and data collection

The research elaborated a convenience sample of approximately 200 vocational school students of the second and third-year study in Malang of Indonesia. The survey project was performed during June and October 2020, adopting online questionnaires. After eliminating about 6.5 percent of incomplete data, approximately 187 respondents can be engaged for the next data analysis. The participants of this study were voluntary, and it was declared for their anonymity. Ethical approval was released by the Institutional Research Committee of Universitas Negeri Malang for this study’s facet.

The demographic participants in this work were presented in . Overall, this research’s participants were vocational students with the distance age of 15 to 17 years old and it was dominated by female students with a percentage of approximately 59 percent. Referring to the table, it was known that online business program is more favorite than marketing subject with the percentage of 53.47 percent and 46.53 percent, respectively. Finally, the majority of parents’ job was an entrepreneur with percentage of 51.87, while small percentages was soldiers and civil servants.

Table 1. The demographic profile of respondents

3.2. Instrument development and data analysis

All the construct’s measurement was performed from preliminary works and literature with slight adjustments in the Indonesia context, and the items were translated from English into Bahasa Indonesia to provide a greater understanding. The questionnaire incorporated thirty-two questions framing the participant’s profile and variables, which were performed. We measured the respondent reaction of entrepreneurial education (EE) using six items from Hasan et al. (Citation2017); Denanyoh et al. (Citation2015), while to perform entrepreneurial intention (EI), we elaborated seven instruments adopted from Linan and Chen (Citation2009). Furthermore, family education (FE) was performed by 11 items adapted from Hisrich et al. (Citation2008) and Ratten et al. (Citation2017), while to calculate environment (E), we involved four instruments adopted from Zahra et al. (Citation2004). Lastly, to understand the students’ entrepreneurial attitude (EA), we adopted five components from Linan et al. (Citation2011). The detailed instrument was provided in Appendix. Furthermore, we determined for each construct using a five-point Likert Scale from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Lastly, we employed Structural Equation Modelling Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS) using SmartPls (version 3.0) to calculate the relationship among variables. The SEM-PLS in this study followed Hair et al. (Citation2017), which includes: evaluation of the measurement model (outer model); (2) evaluation of the structural model (inner model), (3) goodness of fit estimation (GoF), and (4) hypothesis testing.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. The outer and inner assessment model

The predictive model’s assessment is separated into two: the outer assessment model and the inner assessment model. This study performed four indicators for the outer assessment model, namely convergent validity, discriminant validity, composite reliability, and construct reliability (see ). The statistical result of convergent validity demonstrated that all variables, including entrepreneurial education (EE), entrepreneurial attitude (EA), entrepreneurial intention (EI), family education (FE), and environment (E), have loading factors that were ranging between 0.724 to 0.912. It suggests that the variables achieve convergent validity (> 0.70) (Hair et al., Citation2017). At the same time, it can be seen from that the AVE score for all variables is more significant than 0.5, illustrating that the variables fulfill the discriminant validity criteria.

Table 2. The Calculation of Measurement (Outer) Model

also describes the reliability test results in this PLS test using two methods, namely Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR). According to Hair et al. (Citation2017), the composite reliability and Cronbach alpha values were examined, accompanied by the mean of variance extracted (AVE) to check the assessment model’s reliability. All Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability coefficients must higher than 0.7. The results demonstrated that the reliability of the composites varied from 0.819 to 0.945 respectively (> 0.70) to meet the composite reliability criteria (Hair et al., Citation2017). Similarly, Cronbach Alpha (α) of EE, EA, EI, FE, and E was 0.923, 0.865, 0.887, 0.866, and 0.770, respectively (> 0.70), suggesting that it achieved the composite reliability indicator (see ). In addition, the convergent validity in , shows the loading value of EE, EA, EI, FE, and E is higher than 0.70, implicating that the variables achieved the convergent validity (Hair et al., Citation2017).

Table 3. Discriminant Validity

illustrates the outcome of cross-loading for these three variables: entrepreneurial education, entrepreneurial mindset, and entrepreneurial intention is greater than 0.70, which illustrated that the variables to meet the convergent validity determination (Hair et al., Citation2017).

This study empowered heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) stages from Henseler et al. (Citation2015) to perform the discriminant validity. The statistical result for each variable (see ) indicated that the heterotrait-monotrait ratio is smaller than 0.90, which means that the variables have met the discriminant validity.

Table 4. Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio

4.2. The collinearity and R-squared test

The collinearity test has performed to recognize the availability of collinearity in the structure of model. The calculation collinearity test showed that the score of VIF is varying between 1.316–4.062 < 5.00, meaning that the collinearity is not exist, and the construct of the variable is determined as valid. Meantime, the R-squared test aims to perform the robustness of correction from predictions with the standard of 0.67 (robust), 0.33 (moderate), and 0.19 (weak) (Hair et al., Citation2017). The calculation of the R-square test indicated that EA has a value of 0.715, which means that 71.5 percent variable EA can be dramatically performed by the variable of E, EE, and FE. Additionally, the R-square value of EE is moderately presented by E with a score of 0.333. Lastly, the variable of EI is substantially indicated by EE, E, FE and EA with a percentage of 67.0 percent.

4.3. The size effect test (f2)

The size effect test (f2) intends to know the extent to which the impact of the latent predictor variable (exogenous latent variable) on the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2017). In this study, the size effect test (f2) is determined into several criteria: small (0.02), medium (0.15), and large effect (0.35). The previous calculation indicated that the f2 score of E against EE were 0.499, implying that it presents a huge effect size. In addition, the f2 values of EE, E, and FE toward EA were 0.766, that demonstrated a large effect size. Finally, the f2 values of EE, E, FE, and EA toward EI were 0.35, which indicated a large effect size.

4.4. Cross-validated redundancy (Q2)

We applied Cross-validated redundancy (Q2) to assess predictive relevance. The value of Q2 > 0, implies that the model has predictive relevance, which is accurate to a specific construct, while the value of Q2 < 0 implicates that the model lacks predictive relevance (Hair et al., Citation2017). According to the preliminary examination, it can be seen that the Q2 score of each variable is higher than 0, thus indicating that the model has satisfied the predictive relevance test.

4.5. The coefficient path analysis

The path analysis aims at examining the constructed model of the research. The bootstrapping stage has presented to calculate the score of t-statistic and t-value. and provide information about the score of the path coefficient (p-value) from the connectivity among variables studied. From the hypothesis proposed, ten correlations have p-value, which ranging from 0.000 to 0.014. Meanwhile the rest of hypothesis have p-value of 0.561 and 0.567.

Table 5. The summary of testing results

5. Discussion

This current research highlighted the entrepreneurial intention among students in Indonesia by involving several predicted variables including entrepreneurial education, family education, environment, and attitude. Based on the statistical calculation, this study approved nine hypotheses and denied two hypotheses proposed.

The first hypothesis is that entrepreneurship education affects students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Surprisingly, this study found that entrepreneurial education cannot explains the students’ intention of being entrepreneurs. The finding of this work is on the contrary with some previous scholars in the context of European and Asian countries (Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2015; Kim & Park, Citation2019; Li & Wu, Citation2019; Lin, Citation2011) and in Indonesia (Kusumojanto et al., Citation2020; Saptono et al., Citation2020; Wardana et al., Citation2020). This rather contradictory result may be due to the respondents of this study perceiving that entrepreneurship education has not been effective in encouraging their entrepreneurial intentions. This is reasonable because entrepreneurship education is still carried out with material or knowledge-oriented instead of increasing entrepreneurial practices and projects. Additionally, the classroom learning activities solely focus on students’ basic knowledge of entrepreneurship, so they have not been able to build character and strengthen entrepreneurial intentions.

However, our findings become an entry point that the adoption of entrepreneurship education programs in vocational schools has not been effective and equitable. Each vocational school differs in the implementation of entrepreneurship education. In the Indonesian context, this study also means that entrepreneurship education has not sufficiently affected student entrepreneurial intention.

Despite the fact that entrepreneurial education failed in explaining entrepreneurial intention, it has successfully stimulated students’ entrepreneurial attitudes. Keat et al. (Citation2011) mentioned that entrepreneurship education’s primary goal is to enhance the views, behaviors, attitudes, and intentions of students to understand entrepreneurship, have an entrepreneurial mindset, and later become successful entrepreneurs building businesses. Similarly, Wu and Wu (Citation2008) also argued that entrepreneurship education significantly influences a person’s attitude to be an entrepreneur. This finding strengthens the previous scholars regarding the connection between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial attitude (Bae et al., Citation2014; Ozaralli & Rivenburgh: Citation2016; Wibowo et al., Citation2018).

In addition to entrepreneurship education, this work’s finding corroborates previous studies related to family education and environment, impacting entrepreneurial attitude and entrepreneurial intention (Hisrich et al., Citation2008; Basu & Virick, 2010). Referring to TPB Ajzen’s (Citation2002), the environment, especially parental support, strengthens students’ intention to become entrepreneurs. Additionally, Kristiansen and Indarti (Citation2004) emphasized that the determinants of students becoming entrepreneurs include education, personal values, environment, age and work history. Similarly, Gronhoj and Thogersen (Citation2017) found that students from entrepreneur family tends to receive knowledge and it will form attitudes and attitudes. Having parents who are independent or entrepreneurial-based, parents’ independence and flexibility will support and encourage children’s independence from childhood (Randerson et al., Citation2015).

Normally, parents who being of entrepreneurs will encourage independence, achievement and responsibility for their children (Igwe et al., Citation2018; Osorio et al., Citation2017). Then an attitude of independence will promote individual to have own business. The role of parents in fostering the entrepreneurial spirit of children, including with conducive communication in the family environment, training in responsibility for domestic work, training in leading or managing events that occur in the home environment and encouraging children to be active in social environment activities (Farrukh et al., Citation2017; Van Auken et al., Citation2006). We have a strong argument that parents’ resilience when doing entrepreneurship is an inspiration and a real example, so that students are interested in becoming entrepreneurs.

Lastly, our study demonstrated that entrepreneurial attitude can mediate entrepreneurship education, family education, and environment on students’ entrepreneurial intention. These findings confirm the preliminary works of Peng, Lu and Kang (Citation2013); Fayolle and Gailly (Citation2015); Ozaralli and Rivenburgh (Citation2016); Wardana et al. (Citation2020), that entrepreneurial attitudes effectively mediate the influence of several determinant variables including entrepreneurial education, family education and environment on entrepreneurial intention variables. These results show that to strengthen the entrepreneurial intention of vocational school students, the entrepreneurial attitude must be strengthened first. Our results also reinforce Bandura’s (2001) Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), which remarked the connectivity between cognitive variables, environmental factors, attitudes, and individual behavior. This research also contributes to the framework of Winkler and Case (Citation2014); Cui et al. (Citation2019) by emphasizing the entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurial attitude variables. Thus, referring to the SCT theory, entrepreneurship education affects students’ entrepreneurial attitudes and entrepreneurial intentions. Furthermore, family education and environment also affect entrepreneurial intention through the students’ entrepreneurial attitude.

6. Conclusion and recommendation

This study investigated the driving factors of students’ entrepreneurial intention in Indonesia. This study concluded that that intention and students’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship can be performed by students’ environment. However, this study failed in explaining the role of entrepreneurship education and family education in forming intention instead of stimulation students’ entrepreneurial attitude. This surprise findings can be an initial opportunity to elaborate an appropriate model of entrepreneurship education in Indonesia to more practical rather than theoretical in the classroom. As a study by Kirkley (Citation2017); Rachmawan et al. (Citation2015), this research has implications to entrepreneurship education model in schools should synergizes with the family education and students’ environment. This is due to these two variables are crucial for enhancing students’ entrepreneurial intentions. The family environment is basic in supporting students’ growth in entrepreneurship, while entrepreneurship education in schools provides knowledge, theory, and learning experiences. Effective synergy will ultimately improve students’ entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions. Moreover, parents’ involvement in entrepreneurial activities is crucial so that parents of students also support entrepreneurship education programs in schools.

This study has several limitations because it did not include all factors affecting students’ entrepreneurial intention. Also, this study solely conducted in vocational schools in Malang of Indonesia. This study also does not use a mixed method approach, so that the dominant variables that affect the entrepreneurial intention of vocational students cannot be portrayed in detail. Future research needs to use a mixed method so that in more detail the dominant variable can be found, which can be a strategy to boost students’ entrepreneurial intentions effectively. Besides, future research needs to enhance the number of respondents by involving more vocational schools so that research results can be generalized.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Djoko Dwi Kusumojanto

Djoko Dwi Kusumojanto is an Associate professor specializing on Business educational, entrepreneurship education, and entrepreneurship at Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. Agus Wibowo is an Assistant professor of entrepreneurship at Faculty of Economics Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia. Januar Kustiandi is a Lecturer in the Economic Education Program, Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. Bagus Shandy Narmaditya is a Lecturer in the Economic Education Program, Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia.

References

- Ahmed, T., Chandran, V. G. R., & Klobas, J. (2017). Specialized entrepreneurship education: Does it really matter? fresh evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-01-2016-0005

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived Behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned Behavior 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

- Alshebami, A., Al-Jubari, I., Alyoussef, I., & Raza, M. (2020). Entrepreneurship education as a predicator of community college of abqaiq students’ entrepreneurship intention. Management Science Letters, 10(15), 3605–3612. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2020.6.033

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217-254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12095

- Basu, A., & Virick, M. (2008). Assessing entrepreneurship intentions amongst students: A comparative study. Paper presented at the national collegiate inventors and innovators alliance conference, Dallas, TX.

- Bazkiaei, H. A., Heng, L. H., Khan, N. U., Saufi, R. B. A., & Kasim, R. S. R. (2020). Do entrepreneurship education and big-five personality traits predict entrepreneurship intention among universities students?. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1801217. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1801217

- BPS. (2020). Keadaan Ketenagakerjaan Indonesia Februari 2020. Badan Pusat Statistik.

- Brush, C., Ali, A., Kelley, D., & Greene, P. (2017). The influence of human capital factors and context on women’s entrepreneurship: which matters more?. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8, 105–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2017.08.001

- Cui, J., Sun, J., & Bell, R. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurship mindset of college students in China: the mediating role of inspiration and the role of educational attributes. The International Journal of Management Education, 100296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.04.001

- Denanyoh, R., Adjei, K., & Nyemekye, G. E. (2015). Factors that impact on entrepreneurship intention of tertiary students in Ghana. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 5(3), 19–29. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Adjei-Kwabena/publication/328345593_Factors_That_Impact_on_Entrepreneurial_Intention_of_Tertiary_Students_in_Ghana/links/5bc76bafa6fdcc03c78a71e8/Factors-That-Impact-on-Entrepreneurial-Intention-of-Tertiary-Students-in-Ghana.pdf

- Din, B. H., Anuar, A. R., & Usman, M. (2016). The effectiveness of the entrepreneurship education program in upgrading entrepreneurship skills among public university students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 224, 117–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.413

- Farrukh, M., Khan, A. A., Shahid Khan, M., Ravan Ramzani, S., & Soladoye, B. S. A. (2017). Entrepreneurship intentions: the role of family factors, personality traits and self-efficacy. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 13(4), 303–317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/WJEMSD-03-2017-0018

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship attitudes and intention: hysteresis and persistence. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12065

- Gronhoj, A., & Thogersen, J. (2017). Why young people do things for the environment: the role of parenting for adolescents’ motivation to engage in pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 54, 11–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.09.005

- Gurbuz, G., & Aykol, S. (2008). Entrepreneurial intentions of young educated public in Turkey. Journal of Global Strategic Management, 4(2), 47–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.20460/JGSM.2008218486

- Hair, J. F. H., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed ed.). Sage.

- Handayati, P., Wulandari, D., Soetjipto, B. E., Wibowo, A., & Narmaditya, B. S. (2020). Does entrepreneurship education promote vocational students’ entrepreneurial mindset?. Heliyon, 6(11), e05426. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05426

- Hasan, S. M., Khan, E. A., & Nabi, M. N. U. (2017). Entrepreneurial education at university level and entrepreneurship development. Education+ Training, 59(7/8), 888–906. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-01-2016-0020

- Hechavarria, D., Bullough, A., Brush, C., & Edelman, L. (2019). High‐growth women’s entrepreneurship: fueling social and economic development. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12503

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 431, 115–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hisrich, R. D., Peters, M. P., & Shepherd, D. A. (2008). The Entrepreneurial Perspective. McGraw Hill.

- Houshmand, M., Seidel, M. D. L., & Ma, D. G. (2017). The impact of adolescent work in family business on child–parent relationships and psychological well-being. Family Business Review, 30(3), 242–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486517715838

- Igwe, P. A., Newbery, R., Amoncar, N., White, G. R., & Madichie, N. O. (2018). Keeping it in the family: Exploring igbo ethnic entrepreneurial behaviour in Nigeria. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(1), 34–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2017-0492

- Jabeen, F., Faisal, M. N., & Katsioloudes, M. I. (2017). Entrepreneurial mindset and the role of universities as strategic drivers of entrepreneurship: Evidence from the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(1), 136–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-07-2016-0117

- Jayawarna, D., Jones, O., & Macpherson, A. (2014). Entrepreneurship potential: the role of human and cultural capitals. International Small Business Journal, 32(8), 918–943. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242614525795

- Jena, R. K. (2020). Measuring the impact of business management student’s attitude towards entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship intention: A case study. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 106275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106275

- Jogaratnam, G. (2017). The effect of market orientation, entrepreneurial orientation and human capital on positional advantage: evidence from the restaurant industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 60(1), 104–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.10.002

- Jufri, M., Akib, H., Ridjal, S., Sahabuddin, R., & Said, F. (2018). Improving attitudes and entrepreneurial behaviour of students based on family environment factors at vocational high school in Makassar. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 21(2), 1–14. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/improving-attitudes-and-entrepreneurial-behaviour-of-students-based-on-family-environment-factors-at-vocational-high-school-in-mak-7174.html

- Karyaningsih, R. P. D., Wibowo, A., Saptono, A., & Narmaditya, B. S. (2020) Does entrepreneurial knowledge influence vocational students’ intention? lessons from Indonesia. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 8(4), 138–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2020.080408

- Keat, O. Y., Selvarajah, C., & Meyer, D. (2011). Inclination towards entrepreneurship among university students: an empirical study of Malaysian university students. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(4), 206–220. http://www.ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol._2_No._4;_March_2011/24.pdf

- Keyhani, N., & Kim, M. S. (2020). A systematic literature review of teacher entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 4(3), 376-396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127420917355

- Kim, M., & Park, M. J. (2019). Entrepreneurship education program motivations in shaping engineering students’ entrepreneurship intention. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 11(3), 328–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-08-2018-0082

- Kirkley, W. W. (2017). Cultivating entrepreneurship behaviour: Entrepreneurship education in secondary schools. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-04-2017-018

- Kolvereid, L., & Isaksen, E. (2006). New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6), 866–885. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.06.008

- Kristiansen, S., & Indarti, N. (2004). Entrepreneurial intention among Indonesian and Norwegian students. Journal of enterprising culture, 12(1), 55–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1142/S021849580400004X

- Kurczewska, A. (2011). Entrepreneurship as an Element of Academic Education-International Experiences and Lessons for Poland. International Journal of Management and Economics, 30, 217–233.

- Kusumojanto, D. D., Narmaditya, B. S., & Wibowo, A. (2020). Does entrepreneurial education drive students’ being entrepreneurs? evidence from Indonesia. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 8(2), 454. DOI:https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2020.8.2(27)

- Li, L., & Wu, D. (2019). Entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurship intention: Does team cooperation matter?. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0157-3

- Lin, Y.-S. (2011). Fostering creativity through education – A conceptual framework of creative pedagogy. Creative Education, 2(3), 149–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2011.23021

- Linan, F., & Chen, Y. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurship intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

- Linan, F., Urbano, D., & Guerrero, M. (2011). Regional variations in entrepreneurship cognitions: start-up intentions of university students in Spain. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 23 (3–4), 187–215. Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620903233929

- Lingappa, A. K., Shah, A., & Mathew, A. O. (2020). Academic, family, and peer influence on entrepreneurship intention of engineering students. Sage Open, 10(3–4), 2158244020933877. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020933877

- Marini, C. K., & Hamidah, S. (2014). The effects of self-efficacy, family environment, and school environment on the entrepreneurship interest of the culinary service department. Jurnal Pendidikan Vokasi, 4(2), 195-207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21831/jpv.v4i2.2545

- Marques, C. S., Ferreira, J. J., Gomes, D. N., & Gouveia Rodrigues, R. (2012). Entrepreneurship education: how psychological, demographic and behavioural factors predict the entrepreneurship intention. Education & Training, 54(8/9), 657–672. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911211274819

- Olugbola, S. A. (2017). Exploring entrepreneurship readiness of youth and startup success components: entrepreneurship training as a moderator. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 2(3), 155–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2016.12.004

- Osorio, A. E., Settles, A., & Shen, T. (2017). Does family support matter? the influence of support factors on entrepreneurship attitudes and intentions of college students. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 23(1), 24–43. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Arturo-Osorio/publication/319007893_Does_family_support_matter_The_influence_of_support_factors_on_entrepreneurial_attitudes_and_intentions_of_college_students/links/5a0222dd0f7e9b6887479da2/Does-family-support-matter-The-influence-of-support-factors-on-entrepreneurial-attitudes-and-intentions-of-college-students.pdf

- Ozaralli, N., & Rivenburgh, N. K. (2016). Entrepreneurial intention: antecedents to entrepreneurial behavior in the USA and Turkey. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 6(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-016-0047-x

- Peng, Z., Lu, G., & Kang, H. (2013). Entrepreneurial intentions and its influencing factors: A survey of the university students in Xi’an China. Creative education, 3(8), 95–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.38b021

- Pisoni, G. (2019). Strategies for pan-european implementation of blended learning for innovation and entrepreneurship (i&e) education. Education Sciences, 9(2), 124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020124

- Purwana, D., & Suhud, U. (2017). Entrepreneurship education and taking/receiving & giving (TRG) motivations on entrepreneurship intention : do vocational school students need an entrepreneurship motivator?. International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research, 15(22), 349–363.

- Rachmawan, A., Lizar, A. A., & Mangundjaya, W. L. (2015). The role of parent’s influence and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intention. The Journal of Developing Areas, 49(3), 417–430. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/jda.2015.0157

- Randerson, K., Bettinelli, C., Fayolle, A., & Anderson, A. (2015). Family entrepreneurship as a field of research: exploring its contours and contents. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 6(3), 143–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2015.08.002

- Rasyid, A. (2015). Effects of ownership structure, capital structure, profitability and company’s growth towards firm value. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 4 (4), 25–31. https://www.ijbmi.org/papers/Vol(4)4/E044025031.pdf

- Ratten, V., & Jones, P. (2020). Entrepreneurship and management education: exploring trends and gaps. The International Journal of Management Education, 9(1), 100431. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100431

- Ratten, V., Ramadani, V., Dana, L. P., Hoy, F., & Ferreira, J. (2017). Family entrepreneurship and internationalization strategies. Review of International Business and Strategy, 27(2), 150–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/RIBS-01-2017-0007

- Rosmiati, R., Junias, D. T. S., & Munawar, M. (2015). Sikap, motivasi, dan minat berwirausaha mahasiswa. Jurnal Manajemen Dan Kewirausahaan (Journal of Management and Entrepreneurship), 17(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.9744/jmk.17.1.21-30

- Santos, S. C., & Liguori, E. W. (2019). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions: Outcome expectations as mediator and subjective norms as moderator. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(3), 400–415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-07-2019-0436

- Saptono, A., Wibowo, A., Narmaditya, B. S., Karyaningsih, R. P. D., & Yanto, H. (2020). Does entrepreneurial education matter for Indonesian students’ entrepreneurial preparation: the mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset and knowledge. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1836728. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1836728

- Sergi, B. S., Popkova, E. G., Bogoviz, A. V., & Ragulina, J. V. (2019). Entrepreneurship and economic growth: The experience of developed and developing countries. In Entrepreneurship and Development in the 21st Century (pp. 3-32). Emerald publishing limited.

- Shahab, Y., Chengang, Y., Arbizu, A. D., & Haider, M. J. (2019). Entrepreneurship self-efficacy and intention: Do entrepreneurship creativity and education matter?. International Journal of Entrepreneurship Behavior & Research, 25(2), 259-280. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2017-0522

- Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimension of entrepreneurship. In C. A. Kent, D. L. Sexton, & K. H. Vesper (Eds..), Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship (pp. 72-90). Prentice-Hall. Englewood Cliffs.

- Souitaris, V., Zerbinati, S., & Al-Laham, A. (2007). Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? the effect of learning, inspiration and resources. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(4), 566–591. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.05.002

- Staniewski, M. W. (2016). The contribution of business experience and knowledge to successful entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5147–5152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.095

- Van Auken, H., Fry, F. L., & Stephens, P. (2006). The influence of role models on entrepreneurship intentions. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 11(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946706000349

- Wahzudik, N. (2018). Kendala dan rekomendasi perbaikan pengembangan kurikulum di sekolah menengah kejuruan. Indonesian Journal of Curriculum and Educational Technology Studies, 6(2), 87-97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15294/ijcets.v6i2.26712

- Wardana, L. W., Narmaditya, B. S., Wibowo, A., Mahendra, A. M., Wibowo, N. A., Harwida, G., & Rohman, A. N. (2020). The impact of entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial mindset: The mediating role of attitude and self-efficacy. Heliyon, 6(9), e04922. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04922

- Wibowo, A., & Saptono, A., Suparno. (2018). Does teachers’creativity impact on vocational students’entrepreneurship intention?. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 21(3), 1–12.

- Winkler, C., & Case, J. R. (2014). Chicken or egg: entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions revisited. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, 26(1), 37–62. https://www.academia.edu/download/63261675/JBE_2014_Special_Issue_Digital_Edition20200510-49640-1u086c1.pdf#page=46

- Wu, S., & Wu, L. (2008). The impact of higher education on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in China. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15(4), 752–774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000810917843

- Wu, Z. W., & Zhu, L. R. (2017). Cultivating innovative and entrepreneurship talent in the higher vocational automotive major with the “on-board educational factory” model. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(7), 2993–3000. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.00746a

- Yang, J. (2013). The theory of planned behavior and prediction of entrepreneurial intention among Chinese undergraduates. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 41(3), 367–376. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2013.41.3.367

- Zahra, S. A., Hayton, J. C., & Salvato, C. (2004). Entrepreneurship in family vs. non-family firms: A resource-based analysis of the effect of Organizational culture. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 363–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2004.00051.x

- Zhao, H., Hills, G. E., & Seibert, S. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurship intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1265