Abstract

The purpose of this study was twofold. Firstly, it explored Iranian EFL (English as a foreign language) teachers’ receptive and productive metalinguistic knowledge as a function of educational contexts including language institutes and high schools. Secondly, the study delved into EFL teachers’ perceptions of metalinguistic knowledge development in the contexts in question. A total of 200 Iranian EFL teachers participated in a metalinguistic knowledge test entailing 2 modules of production and reception. Besides, a series of semi-structured interviews were conducted with 40 EFL teachers to explore their perceptions concerning metalinguistic knowledge development. The results revealed that the high school teachers surpassed the language institute teachers regarding their productive and receptive metalinguistic knowledge. The results also indicated that the EFL teachers in both high schools and language institutes were better in receptive than productive metalinguistic knowledge. Further, the results of semi-structured interviews substantiated those of the MLK test and revealed considerable points about the metalinguistic knowledge development in the educational contexts under study. The study findings offered clear implications for stakeholders, EFL teachers, and teacher educators.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Some language teachers are calling a noun a “naming word” or “something you can touch” or calling a verb a “doing word”! This may generate misconceptions in the students’ learning. Because foreign language teachers are considered professionals, learners would expect to be able to elicit information from them about the foreign language they are studying. It is anticipated that a learner may ask for a rule, a term, or perhaps request an exemplar of the term in a text. This requires language teachers to possess metalinguistic knowledge (MLK) and be aware of that. Different variables contribute to teachers’ MLK development. The present study tried to fill the gap in the literature by exploring language teachers’ MLK and their perceptions about MLK development in two language learning contexts in Iran i.e. high schools and language institutes. The results lead to an advanced understanding of this topic in these specific settings and will contribute to the global body of research examining teachers’ MLK.

1. Introduction

The impact of subject matter knowledge on teachers’ professional development has become an essential educational issue in recent L2 research. To Shulman (Citation1999), possessing subject matter knowledge lies at the heart of successful teaching. Moreover, professional teachers need to acquire an in-depth knowledge of the subject matter to deal with complex and uncertain situations. Following Shulman’s widespread conception of the knowledge base, teachers should know around three broad and interrelated areas, which are—“subject matter content knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, and curricular knowledge” (Shulman, Citation1986, p. 9). In the same line, in language pedagogy, the rise of attention towards conscious learning processes and the need for equal attention to form and meaning seems to accentuate the role of the teachers’ metalinguistic knowledge (MLK hereafter) in language classrooms. In the context of the language classroom, teachers’ MLK plays a significant role in their ability to improve the learners’ understanding of the language (McNamara, Citation1991) and in shaping their professional capacity to plan for and respond to the learners’ language needs (D. Myhill et al., Citation2013). Inspired by Shulman’s (Citation1987) conceptualization, D. Myhill et al. (Citation2013, p. 78) developed a framework that distinguished between two facets of MLK in terms of “teachers’ metalinguistic content knowledge (the academic domain of knowledge about language, which includes explicit grammatical knowledge) and metalinguistic pedagogical content knowledge (their knowledge of how to teach and develop students’ metalinguistic understanding)”. Andrews (2005) argues that professionalism for foreign language teachers demands the possession of both of these dimensions.

The literature in this regard is rich with the studies that acknowledge the importance of teachers’ MLK in classroom learning and the need for a link to improved learner outcomes (D. A. Myhill et al., Citation2012; Andrews, Citation2001; M. Ellis, Citation2016; Sanchez, Citation2014; Simard et al., Citation2007). However, the need to develop perspective and practicing English teachers’ MLK is unquestionable as a large body of research has so far found gaps in teachers’ MLK in ESL and EFL contexts (Alderson & Hudson, Citation2013; Andrews, Citation1999a, Citation1999b; Andrews & McNeill, Citation2005; Sangster et al., Citation2013; Shuib, Citation2009; Tsang, Citation2011; Wach, Citation2014).

In the same vein, teachers’ professional life is inseparable from the learning context in which learners learn the language in every English language teaching program. Research has underscored the challenges encountered by EFL teachers on the path towards MLK development in different educational contexts. The present study was inspired by the gaps in the literature focusing on Iranian EFL teachers’ MLK in two dominant educational contexts, including language institutes and junior/senior high schools. Following different approaches, dutifully and in command of the power of specific policies, these contexts have profound roles in teachers’ professional behaviors in Iran (Mohammadian & Norton, 2012; Sheibani, Citation2012). In the official curriculum of public education in Iran, English is a compulsory course for high school students. Iranian children start their formal literacy education at the age of seven and start learning English at the age of twelve—from the first year of the Secondary Program in high schools- which continues for six years (Zarrabi & Brown, Citation2017). Even though the dominant language teaching approach in schools in Iran from 2010 (See Anani Sarab, Citation2010) has been Communicative Language Teaching (CLT hereafter), after graduating from high school, hardly some of the learners can communicate fluently and make practical use of language in real contexts (Razmjoo, Citation2007; Razmjoo & Barabadi, Citation2015; Safari & Rashidi, Citation2015). According to Safari and Rashidi (Citation2015), the ELT program in Iran has failed to promote learners’ long-life communicative abilities and prepare them for language use in authentic situations. They illuminated the reasons for this failure as textbooks, the status of English in the educational system, multilevel classes, and preservice and in-service classes. Likewise, reviewing the literature, this failure was also attributed to the “misalignment between national curriculums that advocate communicative approaches and the content of high-stakes examinations, which typically emphasize grammar, vocabulary, and reading questions” (Underwood, Citation2017). Under these circumstances, many teachers report structural, transmission-based approaches to be the most efficient and effective means of preparation (Dahmardeh, Citation2009; Nishimuro & Borg, Citation2013; Rahman & Karim, Citation2015; Saito, Citation2016, Citation2017; Underwood, Citation2012). Structural, transmission-based approaches are characterized by a focus on the development of reading ability through teacher-led instruction. Grammar is taught deductively (through clear explanation), and the translation of written texts from the target language to the first language is universal (Underwood, Citation2017). Within the same context, the direct observation of the high school community in Iran emerges a severe problem for EFL students who are structurally proficient but unqualified to communicate appropriately (Safari & Rashidi, Citation2015; Zarrabi & Brown, Citation2017).

On the other hand, currently, English language institutes are playing an increasingly important role in Iranian society (Mohammadian & Norton, Citation2017), and as argued by Borjian (Citation2010), “it is hard to imagine the accomplishment of the private sector without considering the enormous interest shown by Iranian youth in attending these institutions” (p. 60). Language institutes are private institutions that provide English instruction to many people, including students in different educational settings and age ranges. Mohammadian and Norton (Citation2017) assert that school students who wish to develop their English communicative skills look for support beyond public schooling and therefore choose to study at language institutes. According to Ghorbani (Citation2011), English language institutes “owe their existence to the very weakness of spoken English instruction in the formal education system” (p. 512). Noteworthy to mention is that the language institutes in Iran follow a robust CLT version, and the literature in the Iranian ELT context strongly supports their excellent reputation for rendering a community of learners with better communicative proficiency than schools (Dahmardeh, Citation2009; Khoshsima & Hashemi Toroujeni, Citation2017; Riazi & Razmjoo, Citation2006; Sadeghi & Richards, Citation2015; Safari & Rashidi, Citation2015). In this regard, based on their findings, Scholfield and Gitsaki (Citation1996) claimed that the success of the private language institutes might not be the result of fundamentally better teaching and learning procedures. Instead, they attributed the success to the reasons such as a stricter environment with more significant discipline, a smaller number of students attended the private institutes’ classrooms and a higher number of teaching sessions.

Finally, school teachers in Iran are employed by the Ministry of Education. They are mostly educated from teacher training centers or have a university degree in TEFL or linguistics. Teachers recruited by language institutes, on the other hand, may have different university majors (including English majors) or holding no university degree at all. Hence, even specialist English language teachers are also primarily products of the system, which has not adequately equipped them with proper MLK (Zarrabi & Brown, Citation2017). For example, Alderson et al. (1996) put forward the idea that teachers may use English effectively, but without MLK, they are less effective in teaching grammar. Similarly, Wang (Citation2010) argues that teachers’ linguistic competence must be addressed first before students can be adequately taught.

Accordingly, the limited MLK of teachers in private institutes and high schools in Iran (Hayati et al., Citation2017) demands intense attention in the SLA research world, mainly as few studies have focused on the challenges EFL teachers have in different educational contexts concerning MLK development. Therefore, considering the ideas mentioned above and literature, the following questions were addressed in the present study:

Q1. Are there any differences between high schools and language institutes EFL teachers in terms of their productive and receptive metalinguistic knowledge?

Q2. What perceptions do high schools and language institutes EFL teachers hold about their MLK level and development?

Based on question 1, it was hypothesized that the school and institute EFL teachers have differences concerning their productive and receptive MLK because the schools’ language teaching curriculum in Iran is primarily inclined towards form-oriented instruction compared with language institutes that obey different policies (Razmjoo & Barabadi, Citation2015; Safari & Rashidi, Citation2015). Even though the struggle between communicative approaches and traditional approaches in Iranian contexts leads the teachers to swing toward the two sides of this pendulum, it seems that high school English teachers are more inclined towards the traditional side (Riazi & Razmjoo, Citation2006) and have more exposure to the metalanguage and grammatical rules.

It is anticipated that the study results will contribute to the enrichment of the EFL teachers’ development programs and teacher educational affairs in general and of the Iranian EFL community in particular. Also, explorations of the differences between schools and institutes can inform L2 pedagogy in practical and meaningful ways.

2. Review of literature

2.1. Metalinguistic knowledge: the components

D. Myhill et al. (Citation2013) argue that, depending on the study, there may be a tendency to use metalinguistic either as a synonym for grammatical knowledge or as an over-arching knowledge set of which grammatical knowledge is a subset. In her study, Myhill (Citation2011) defines MLK as “explicit bringing into the consciousness of an attention to language as an artifact, and the conscious monitoring and manipulation of language to create desired meanings grounded in socially-shared understandings” (p. 250). Moreover, she considers the grammatical content knowledge just one part of this MLK as teachers’ explicit knowledge of grammar in terms of morphology and syntax.

In other studies, MLK is also defined as declarative knowledge, which can be brought into conscious awareness and articulated using the metalanguage of grammatical terminology (Myhill & Jones, Citation2015; Roehr, Citation2007). According to S. Andrews (Citation2007), declarative and procedural awareness are defined as two dimensions of Teacher Language Awareness. Declarative metalinguistic awareness refers to the MLK that a teacher possesses and can formulate. In contrast, procedural metalinguistic awareness refers to knowledge in action which means how knowledge is drawn upon and applied in the context of the language teaching and learning process and the ability of a teacher to make effective use of such knowledge. Andrews (2005) argues that professionalism for teachers of a foreign language demands the possession of both of these dimensions in addition to adequate language proficiency.

Ellis (Citation2004), Berry (Citation2009), and S. Andrews (Citation2007) indicated that declarative knowledge of L2 teachers has two main components: explicit knowledge of grammar rules and knowledge of grammar terms. Knowledge of terminology also includes knowledge of the concepts which the terms denote, and according to S. Andrews (Citation2007) and Ellis (Citation2004), can be both in receptive and productive modes.

A relevant review of the literature indicates that “a combination of measures such as identification of speech parts, identification, and correction of speech errors and verbalization of rules” is needed to examine the MLK (Alderson et al., 1997, as cited in Gutiérrez, Citation2013, p. 177). Although, these measurement results have been considered sufficient to determine the MLK competence (Alderson & Hudson, Citation2013; Tokunaga, Citation2014) in most of the studies; there are some studies in which the results have been presented in more detail by focusing on knowledge of rules or/ and knowledge of terms, i.e., the components of the language, separately (S. Andrews, Citation2007; Berry, Citation2009). Some of these studies have also included the analysis of receptive and productive knowledge, regarded as sub-divisions of knowledge of rules and knowledge of terms (Almarshedi, Citation2017). As their names suggest, receptive knowledge means the possession of explicit knowledge, while productive knowledge necessitates producing grammatical terms and rules. Productive knowledge can be produced formally or informally. For example, when language teachers use terminology explaining a grammar rule or stating a grammatical term, they employ formal productive knowledge. On the contrary, sometimes, these rules and terms can be explained without using terminology (i.e., informally).

MLK in this study as the declarative dimension of teacher language awareness (S. Andrews, Citation2007) and as the grammatical content knowledge; “teachers’ explicit knowledge of grammar in terms of morphology and syntax” (D. Myhill et al., Citation2013) is a concept which ranges from being able to understand patterns in different languages to know the metalanguage, i.e., the standard vocabulary to talk about language, to having sound knowledge of the structure of language, and finally to be able to verbalize it.

2.2. Empirical studies on MLK

The volume of research into the MLK of teachers has increased, especially concerning English language teaching (Almarshadi, 2016; Andrews, Citation1999a, Citation1999b; Andrews & McNeill, Citation2005; Berry, Citation2009; Haslam & Cajkler, 2005; Myhill & Jones, Citation2015; Sangster et al., Citation2013; Shuib, Citation2009; Tsang, Citation2011; Wach, Citation2014). The majority of them have concluded that there are deficiencies in teachers’ MLK. Some of them are discussed as follows:

Andrews (Citation1999a, Citation1999b) explored explicit knowledge of English grammar terms and grammar rules among teachers and student teachers in Hong Kong. These teachers all had fewer than five years of teaching experience. The overall results of Andrews’s studies showed that the L2 teachers’ MLK was not high, and they suffered from gaps and weaknesses in some components of MLK, especially the productive knowledge of rules. Another study carried out by Andrews and McNeill (Citation2005), which involved testing three L2 teachers in Hong Kong, had almost the same results. Despite being proficient in English, all three participants performed poorly in explaining the errors they had corrected and providing grammar terms. In addition, they demonstrated a comparatively better receptive knowledge of terms than the productive. Shuib (Citation2009) also conducted a study to evaluate the MLK of 71 Malaysian primary English teachers and reported similar findings to Andrews (Citation1999a, Citation1999b).

Unlike the other studies, Tsang’s (Citation2011) study in Hong Kong redesigned Andrews’ (Andrews, Citation1999a) test, concluded that the participants’ mean scores in the production task were higher than their mean scores in the recognition task.

Indeed, several researchers (e.g., Alderson & Horak, 2010; Purvis et al., Citation2016) have sought to measure the MLK of student teachers after taking a grammar course designed to improve their MLK. For example, Alderson and Horak (2010) reported on two tests to test the MLK of undergraduate English Language and Linguistics students, who were potential teachers. The results showed that instruction resulted in improved recognition of parts of speech and grammatical functions. Similarly, Purvis et al. (Citation2016) examined the effects of teacher preparation coursework in building preservice teachers’ MLK. Changes in participants’ phonological awareness, morphological awareness, and orthographic knowledge were tracked across the teaching period. The cohort demonstrated significant gains across all measures.

Almarshedi (Citation2017) conducted a study on the MLK of female experienced and student language teachers in an English Language department in Saudi Arabia. He intended to explore the level and nature of their MLK and its components in sentence and text levels. He also investigated the participants’ self-perceptions via interviews, questionnaires, and role-playing. The study showed that experienced teachers surpassed student teachers’ MLK and its components. Moreover, the teachers in both groups lacked an understanding of phrases and clauses and were deficient in producing the corresponding terms. It also revealed that a good level of MLK at sentence level did not guarantee an ability to apply it to more complex grammar items in a text.

Recently, Mutaf (Citation2019) conducted a study investigating the level of MLK of the preservice English teachers and the effects of teachers’ gender and grade on their MLK. He concluded that the majority of teachers had a moderate level of metalanguage. He found no significant effect of gender on teachers’ metalanguage while teachers’ university grade differences indicated a significant effect on teachers’ MLK. He also indicated that almost none of the participants was well aware of the MLK as a concept, and they estimated their MLK level insufficient that needs further development.

In literature, the studies conducted measuring teachers’ MLK as defined in this study in the Iranian English teaching context were scarce. Seifoori (Citation2015), for example, conducted a quasi-experimental study to compare the impact of teacher-oriented vs. learner-generated metalinguistic awareness activities on the writing accuracy of Iranian students who majored in TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language). She concluded that, if appropriately planned, formal metalinguistic instruction (in favor of teacher-oriented metalinguistic awareness) can assist learners to overcome the risk of fossilization of prematurely learned grammatical items and achieve higher grammatical accuracy levels proficiency.

Ahangari and Abdi (Citation2017) conducted a study to investigate whether there is a relationship between non-native Iranian in-service and preservice teachers performing the metalinguistic and linguistic knowledge tests. The findings revealed that the two groups of teachers did not differ significantly concerning their performance on the linguistic test. However, the in-service teachers outperformed their counterparts in the MLK test.

Reviewing the literature, the findings from recent research on MLK in Iranian contexts have shown a much higher focus on such knowledge in L2 learning and use (Nazarian & Izadpanah, Citation2017; Modirkhamene, Citation2008; Seifoori, Citation2015) and teachers’ MLK and the factors contributing in its development seems an area that has hitherto received only peripheral attention in research on MLK. Moreover, no study thus far has examined a comparison between school teachers and private language institute teachers in this regard. This study seeks to address this gap in the literature by comparing EFL teachers in terms of their productive and receptive aspects of MLK as a function of these two settings.

3. Method

3.1. Design

The present study employed a quantitative/qualitative design to take advantage of the benefits associated with both qualitative and quantitative methods and to offset the disadvantages of using a single method (Punch, Citation2009). The quantitative data collected through the MLK test for teachers were used to measure the participants’ MLK level in two modes (production/recognition) and provide the opportunity for the comparison of the two targeted groups. Concurrent with this data, semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore the participants’ perceptions of MLK and its development. The results from these two sets of data are then merged to provide an overall conclusion.

3.2. Participants

The quantitative data for this study were collected from Iranian EFL teachers working in language institutes and high schools in Iran (N = 200; 125 females, 75 males). Convenience sampling was used to select participant teachers in the study. The participants came from two provinces in Iran, and their ages ranged from 20 to 50 years. For the qualitative phase, 40 teachers from participants in the quantitative phase of the study were invited to participate in the interviews. The invitation for interviews was based on purposive sampling, which, according to Babbie and Benaquisto (Citation2008), is the selection of participants based on the researchers’ judgment of “which ones will be the most useful” (p. 527). In addition, to ensure the maximal variation sampling, EFL teachers with different academic and teaching experience backgrounds, different MLK test scores, and different ages were selected. presents the profiles of EFL teachers who participated in the quantitative and qualitative phases of the study.

Table 1. EFL Teachers’ Profile

3.3. Setting

The EFL teachers were selected from two educational contexts, including language institutes and high schools.

3.3.1. Language institutes

Language institutes are private institutions that provide English instruction to many people, including students in different educational settings and with different age ranges. Teachers recruited by Language institutes in Iran may have graduated in different university majors such as language studies, education, engineering, etc., or holding no university degrees. However, teachers must qualify to enable them to be English teachers: some teachers have a university degree in TEFL or linguistics, but the majority have entered the profession by completing teaching training centers provided by the target institutes.

3.3.2. High schools

High schools are educational centers affiliated with the Ministry of Education of Iran. Teachers recruited by the government usually hold a degree in language studies and may have passed different teacher training (in-service) courses.

3.4. Data-collection procedures

Data collection from the participants was conducted in two phases: The data for the quantitative phase was collected through an MLK test administered to both school and institute teachers in two different sessions in the first week of May 2019. For this aim, the participants were invited to meet in the meeting room provided by the General Administration for Education in each province. They took the test under the researchers’ supervision. The participants were told to take as much time as they needed to complete the task. On average, each test session took approximately 40 minutes (ranging from 30 to 40 minutes). The MLK test was administered to both school and the institute teachers in the same condition and the same site during the same week. The date and details for the next meeting for phase two of the study were arranged. Phase two of the research was conducted in the third week of May 2019, one week after the test administration sessions (phase 1). In this phase of the study, forty teachers (20 from each group of participants) were invited to participate in the interview. It was a purposive sampling as the interviewees were chosen based on their MLK levels and their different genders, years of teaching experience, and majors. The researchers met with each of them individually on-site, at mutually convenient times. Each of the meetings took up to 15 minutes. The interviews were mostly conducted in English. However, Persian was used to guide the discussion where needed. The researcher added some new questions during the interview as the participants’ individual experiences and attitudes pushed the discussion. Consequently, with the participants’ permission, all of the interviews were audio-recorded.

To ensure the rights and safety of research participants, consent was actively provided by every participant by asking them to sign consent forms for different methods of data collection involving personal contact like interview sessions (attending and permission for recording the interview sessions) or attending test sessions, etc. They were also given an information sheet about the whole study besides an oral explanation of the study’s objectives. The participants were assured that their data would be confidential

Moreover, while analyzing and reporting data, the participants’ confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed by allocating the codes of HST (high school teacher) 1–20 and INST (institute teacher) 1–20 for high school teachers and institute teachers, respectively. Additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information was included in this study.

Also, before conducting any action regarding the participants in the present research, consent letters were signed by the people in charge, both in schools (Bureau of Education) and the institutes (the head of the departments).

3.5. Instrumentation

3.5.1. Metalinguistic knowledge test

The instrument employed for the quantitative phase of the study was an MLK test (see Appendix A) adapted from Almarshedi (Citation2017). Reviewing the related literature, different tests were used to measure students’ and teachers’ MLK of the target language in different studies (Alderson et al., 1997; Andrews, Citation1999b; Andrews & McNeill, Citation2005; Elder et al., 2007; Tsang, Citation2011; Wach, Citation2014). However, Almarshadi’s test was matched with the objectives of the present study based on the following criteria examined: (a) The context of the present study and the target contents were very similar to Almarshadi’s (considering the features that were commonly covered in the high school and institute teaching syllabuses in Iran), (b) the receptive and productive mode were considered and tested, and (c) the MLK assessment in text-level was included in the test making it more comprehensive (the majority of the studies had used tasks in sentence level). Furthermore, the MLK test was reviewed by two experts in the field of applied linguistics to guarantee the validity of the instrument.

3.5.1.1. Test features

Besides the information provided by the Curriculum and Textbooks Development Office in Iran (2019), the researcher consulted several experienced English teachers to select the features to be tested. Eventually, the following test features with slight modification were proved to be suitable for the objectives of this study: For testing teachers MLK via knowledge of grammar terms; word classes (e.g., noun, adjective), grammatical roles (e.g., subject, object), types of sentences (e.g., complex sentence, minor sentence), clauses (e.g., noun clause, adjective clause), and phrases (e.g., noun phrase, adjective phrase), and for testing the MLK via knowledge of grammar rules, the formation and use of the tenses (e.g., simple present, present continuous and simple past), superlative adjectives, definite article, relative pronoun, adjective clause, modals, subject-verb agreement, expression of quantity (many), question tags, verbs followed by an infinitive.

3.5.1.2. Structure of the test

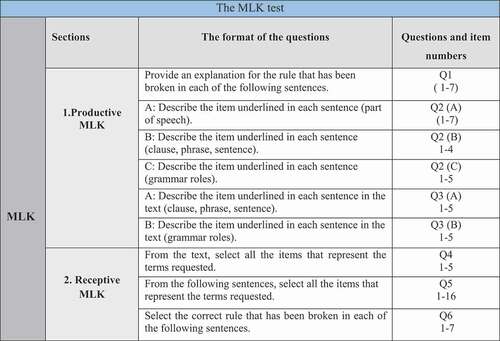

Sixty-one items were distributed to measure the MLK production and reception via the MLK components: Knowledge of grammar terms and knowledge of grammar rules. The structure of the test () consisted of two main sections: Productive MLK and receptive MLK. Questions 1, 2 (A, B, C), and 3 (A, and B) of the test were considered to measure the teachers’ productive mode of MLK, and Questions 4, 5, and 6 were considered to measure the receptive tasks (see the MLK test in appendix A).

Figure 1. The structure of the MLK test. Adapted from “Metalinguistic knowledge of female language teachers and student teachers in an English language department in Saudi Arabia: Level, nature and self-perceptions” by R. M. Almarshedi, Citation2017, p. 81. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Leicester, England.(Citation2017)

Examining the MLK test (Almarshedi, Citation2017) carefully, no significant modifications were required for the main structure of the test. However, slight changes also were made in instruction wording and format. The Arabic part of the instruction was changed into Persian, and the parallel Persian instructions were replaced. Moreover, the items remained almost unchanged except for question 6 (items 2 and 5): Item 2 was considered too simple by test examiners as piloted, and item 5 was recognized testing a repeated feature in the same section.

3.5.2. Interview

For the qualitative part of the study, the researchers performed semi-structured interviews with 40 EFL teachers from the target group in the study. Based on research objectives, five questions were designed to guide the interview sessions. During the sessions, the interviewees were also asked to comment on issues emerging from the research questions conducted in the study’s first phase. Accordingly, questions one to three were directed toward the target teachers’ perceptions about their MLK production and reception, linked to the MLK test in phase 1. Questions 4 and 5, however, asked their opinions about the teachers’ MLK development in their professional life. The links were made clear to the participants by the way the questions were framed.

3.6. Reliability of the instrument

The reliability of the test was assessed by using the KR-21 index, which indicated a relatively high level of reliability (.90). As shown in , the reliability indices of productive and receptive modules of the MLK test were also acceptable (.74) confirming the reliability of the MLK test. Also, the inter-rater reliability of the data was checked after a second-rater marked the test. The results by Cohen’s Kappa demonstrated an almost perfect agreement between the two raters (k = 0.94). Based on the assumptions, the higher the resulting value of the Kappa, the lower the expected chance agreement meeting part of the validity of the test results.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of KR-21 Reliability Indices

To ensure intra-coder reliability of the qualitative data, the researcher coded all the data twice. There was a two-week interval between the two rounds of coding. Any mismatches found between the two rounds of coding were double-checked. Where necessary, the themes were revised and were specified more clearly. The intra-coder reliability was computed using a subset of the data, k = .95. For inter-coder reliability, the data was coded by a fellow doctoral student, using the finalized five themes. The inter-coder reliability was good, k = .89. Differences in coding were reconciled through discussion.

3.7. Data analysis

The statistical data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24. Concerning the first research question, a multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) was run. For the qualitative data analysis, the recorded interviews (with the participants’ permission) were transcribed and coded using thematic analysis (Dörnyei,2007). After identifying the main patterns, recurrent words and phrases were coded and analyzed on a semantic level to form themes and sub-themes. Next, the emerging themes were subjected to frequency analysis and were finally tabulated.

Moreover, the statistical technique employed to probe the first research question (MANOVA) assumed normality of data, besides its specific assumptions. Thus, the normality assumption for the collected data was checked, and because the absolute values of the related ratios were lower than 1.96, it was concluded that the present study data met the normality assumption.

4. Results

4.1. The first research question

A multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) was used to probe the first research question to determine if there were differences between high schools and language institutes EFL teachers’ productive and receptive MLK. To this end, all the assumptions of MANOVA were investigated first. Based on Levene’s test, there were not any significant differences between the two groups’ variances on production (F (1, 198) = .148, p > .05) and reception (F (1, 198) = .729, p > .05) of MLK. Furthermore, the non-significant results of the Box test (M = 1.21, p > .001) indicated that the homogeneity of covariance matrices was met.

The main results of MANOVA (F (2, 197) = 32.12, p < .05, partial eta squared = .246 representing a large effect size) indicated that there were significant differences between the two groups’ MLK production and MLK reception. Likewise, the MANOVA tests of between-subjects effects performed on all variables separately which indicated that the workplace (high school/institute) differed significantly in relation to variables including MLK production (F (1, 198) = 58.87, p < .05, partial eta squared = .229 representing a large effect size) and MLK reception (F (1, 198) = 50.03, p < .05, partial eta squared = .202 representing a large effect size).

In sum, based on the MANOVA results and following the descriptive statistics illustrated in , it can be concluded that the high school EFL teachers had significantly higher means on MLK production (M = 16.84, SD = 4.403) than the institute teachers (M = 11.98, SD = 4.553) (F (1, 198) = 58.87, p < .05, partial eta squared = .229 representing a large effect size). Likewise, the high school group had a significantly higher mean on MLK reception (M = 19.05, SD = 4.321) than the institute group (M = 14.45, SD = 4.791) (F (1, 198) = 50.03, p < .05, partial eta squared = .202 representing a large effect size). Moreover, for the highest and lowest mean of all variables, high school reception (M = 19.02) recorded the highest mean score whereas the lowest mean was ascribed to institute production (M = 11.98).

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics for Production and Reception of MLK by Institutions

4.2. The second research question

Semi-structured interviews were primarily meant to explore EFL teachers’ perspectives of their MLK regarding the educational contexts in question to answer the second question and support the quantitative data. The data gleaned from the interviews were subjected to thematic analysis wherein the five critical themes emerging from the data are addressed in the following sections A to E. At first, shared themes between EFL teachers in both contexts will be presented ranging from A to C, and then, themes salient in school teachers’ results will be presented independently in parts D and E. To protect the participants’ confidentiality and anonymity, the codes HST (1–20) and INST (1–20) were allocated to high school teachers and institute teachers, respectively.

4.2.1. Shared themes emerged from school and institute teachers’ interview results

A) The teachers’ attitudes towards their MLK level

The interview results showed that most of the teachers in both groups were satisfied with their receptive and productive MLK. High school teachers, however, expressed more satisfaction with their MLK comparing the institute teachers; i.e., over 70% (15 out of 20) of school teachers had a pretty high satisfaction whereas only (10 out of 20) institute teachers could strongly confirm their MLK adequacy and the ability to use it.

Some of the institute teachers’ responses conveyed a kind of hesitation about their own MLK. They seemed to feel they lacked such knowledge. When they were asked, “How do you feel about your MLK? Do you think your knowledge is enough in this regard?” some of them gave short, negative answers like “no, I do not think so’ (e.g., INSTs 2, 3, & 7). The school teachers evaluated their knowledge more positively, but they also felt gaps in their MLK. There were also interviewees among high school teachers who characterized their knowledge as “low”, “limited”, or “weak.”

Some of the high school teachers measuring their MLK against the actual requirements of their teaching context (which claimed was not very challenging) reported that their knowledge was adequate for their present teaching context as teachers at the middle or secondary stages. One of the school teachers, for example, asserted that:

I’m satisfied with my MLK to a great extent. I feel my knowledge is enough to teach at this level. I’ve spent many years teaching, and I don’t remember that I have had any troubles in this regard. (HST12)

More analysis revealed that both groups of teachers reported the MLK production more struggling area than the MLK recognition. There were only three interviewees out of 40 who remained neutral in their evaluation in this regard. The teachers, also, claimed that they had more problems in doing productive MLK tasks reflecting on the MLK test in this study. The following quote typifies one of the institute teachers’ perceptions in this regard:

I can recognize terms and rules easily, but when it’s time for producing them, I can’t remember the right words. Maybe, I don’t know some of them. (INST5)

This was somehow in common with the test results in this study as the participants performed better in reception rather than production.

B) The beneficial effects of teachers’ MLK on the students

A typical quote from teachers was that “as an English teacher, I need to know grammar rules and terms.” Both groups of teachers explained how MLK could help them in different ways via some activities. They believed it is necessary for giving examples and explanations in teaching grammar lessons or teaching skills by making salient the key grammatical features within the input. Other benefits commonly mentioned by both school teachers and institute teachers were the need for MLK in correcting students, giving feedback, and making a deeper understanding of grammatical points by students in the classroom. The following excerpt is by an institute EFL teacher who firmly believed that teachers should pose MLK to teach and talk about grammatical issues even while teaching other skills.

Yeah, of course, that’s important to me. In my writing classes, grammar terms and rules are used a lot. I ask the students to analyze the sentences and the texts explaining grammatical rules and discover not only the grammaticality of the sentences but also the feasibility of the correct meaning-form connection. I correct them and give feedback on their tasks in the same way, too. (INST 10)

However, most of the teachers believed that MLK wouldn’t be beneficial when the students’ level was low. They said that they sometimes use Persian to explain rules because the students cannot understand them. One of the school teachers (HST10), for example, felt that in order to avoid confusion, she should use a few terms and explain the rules in Persian first and then in English. She said: “But if you complicate the rule, the students will also be confused and hate the subject. I sometimes make it concise and skip some parts.” Alternatively, one of the institute teachers (INST 3), teaching at the elementary level, stated that: “I teach children. It is enough to use basic terms. The level of my students requires simple rules without much use of terminology. I rarely teach grammar explicitly”.

The analysis conveys that even though the teachers found MLK beneficial for themselves and the students, they preferred to use it based on their students’ level and needs.

C) MLK and the language teachers’ professional community

a) The effects of MLK on teachers’ confidence

Another common theme in the interviewees’ responses was the effect of MLK on their confidence. One of the issues they referred to was that the lack of knowledge has some adverse effects on their confidence. Most of them believed that as teachers, they need to be equipped with subject knowledge to be able to join the ELT community. An institute EFL teacher (INST4), for instance, stated that he is not courageous enough to use different grammatical terms. He directly put out the issue and said: “I think that lack of knowledge harms my self-confidence.” Many teachers stated that they had the same feeling of fear, tension, and confusion about their MLK. Their low level of MLK, knowing only basic rules and just a few terminologies restricted to their daily teaching, was the main reason for their lack of confidence in this regard. The following two interview excerpts typify their perceptions in this regard:

I have a fear to talk about grammar in front of other colleagues in professional groups like the ones in social media such as Telegram, Instagram, and so on, or while attending conferences and workshops. … I’m not sure if I’m using the right terms or explaining the correct rules, so I prefer to be silent rather than giving my opinion about the issue. (HST4)

I don’t have enough knowledge of grammar and rules. It is embarrassing if I can’t answer my students’ questions. When I think about that, I get nervous. Because of that, I’m not interested in involving in grammar lessons. (INST 2)

On the other hand, some teachers approved the issue by having knowledge and satisfaction with their MLK, insisting on the positive effect it has on their confidence. When they were asked about the effect of MLK in their workplace or with their colleagues; different answers illustrated the same theme with a positive impact of MLK on teachers’ self-confidence:

As an English teacher, I need to know the rules and terms. How can I teach the students while I have problems with these subjects? In my opinion, knowing the grammar and being able to explain it, not only is a help in teaching but also gives the teacher the needed confidence in front of class and students. Students ask questions, and you should be ready for that. (INST11)

b) MLK required for self-study and more development

Another issue that most teachers had a common viewpoint about was that they need MLK for self-development. They claim that it’s a cyclic matter as they need to study grammar books to have more MLK and, in turn, to study language, they need higher MLK. One of the institute EFL teachers in upper-intermediate level who was the head of teachers in a technical institute supported the idea and said:

Teachers should be knowledgeable in this regard to be able to defend their position as professional teachers in their workplace. They need the knowledge of rules and terms as an important basic knowledge of subject matter and use it in their professional talks to other teachers or grasp the analysis presented by other committee members. (INST14)

Another English teacher holding a Ph.D. in TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) in a well-known digital school, where a more communicative (task-based) approach is encouraged than other ordinary state schools, stated that:

For teachers, some learning takes place in the classroom, and some may still take place outside the classroom as a dynamic dialogic mediation, via in-service courses or even self-study from different sources. Depending on the extent to which the teacher knows, he or she can benefit from the training or use the opportunity to become involved in any teacher developmental program. I think MLK is necessary for L2 teachers when they encounter grammatical points directly from sources such as the textbook. You know, definitely, they also need to use or understand it when, for example, they take part in a discussion in any professional meetings. So, in my opinion, it’s part of the knowledge for being a professional member of the ELT community. (HST15)

4.2.2. Themes found in school teachers’ interviews

D) The UEE and MLK development

One of the common themes that emerged from the school teachers’ thoughts and beliefs was the impact of the UEE on their professional life. They believe that the highly competitive high-stakes public examination of the UEE requires the demonstration of grammar knowledge. Probably in the Iranian school context, the trauma of UEE affects all other subject knowledge taught in schools, English is not an exception. Even though they did not perform successfully in the MLK test in this study, during interview sessions, most teachers expressed their feeling that they are obliged to focus on forms and consequently MLK in their teaching because of the expectation of the Ministry of Education and its policies. One of the school teachers teaching English to secondary students in grades 11 and 12, is influenced by these contextual factors. She referred to her classrooms and stated:

It is not a case of choice. We trapped. Everywhere you look are the walls of UEE. The students should be prepared for the exam. They {policy makers, material developers: The researcher asked for clarification} say that the books are based on the CLT approach, but in reality, we have not enough time or motivation to fulfill the aims because we, both the teachers and the students, have the concern for UEE. (HST10)

The force of UEE mentioned by almost all school teachers can probably be one of the primary sources of the importance of MLK in Iranian High schools and the better performance of school teachers in the MLK test in this study.

E) The deficient policies and plans in schools and MLK development

Another critical issue elicited from school teachers’ interviews was their complaints about time restrictions, a set almost unchangeable curriculum, poor implementation of CLT, prescribed textbooks, and public examinations. Within such a context, most teachers are likely to feel that they have little alternative but to engage with form. They also complained about the partially deficient implementation of CLT. English Language curriculum in Iran may have been conceptualized following communicative principles, but the realization in many secondary schools, including participants in this study, has been a fragile form of CLT. The partial implementation of CLT has faced teachers with the difficulty of making a balance between form and meaning-based instruction, and this may be a possible tendency towards better MLK development. Some of school teachers’ accounts in this regard are as follows:

There is not enough time to do communicative activities, and if there was time … you know I teach in grade 11, we should teach vocabulary and grammar. We work on reading, the vocabularies, and the grammatical points for students’ UEE preparation. (HST10)

We are baffled. The books and the approach have changed. However, nothing is matched with them. There is not enough time to do CLT activities in the classrooms. Moreover, the final oral exams are not standard. There is not a suitable technology for language teaching at schools. Some of the students are ambitious and strongly motivated; I will be anxious when I do not know to work on their speaking/listening or focus on the other students who expect rapid progress in their knowledge for UEE. (HST12)

5. Discussion

The overall results showed a deficient level of MLK for both high school and language institute EFL teachers. However, concerning the first research question, and based on the analysis, it is well documented to justify the total priority of school EFL teachers on the institute EFL teachers regarding their productive and receptive MLK. Most of the previous studies (e.g., Andrews, Citation1999a; Andrews & McNeill, Citation2005; Shuib, Citation2009; Tsang, Citation2011; Wach, Citation2014) observed limitations in EFL teachers’ MLK in different contexts. In this study, the same pattern emerged regardless of whether the English teachers are teaching at schools or institutes, i.e., Iranian school and institute English teachers typically have considerable gaps in their MLK.

The school EFL teachers’ priority in MLK (productive and receptive modes) in this study can be explained by reviewing the two settings investigated in the study. These two standard settings in Iran (school and language institute) exist in very different economic, cultural, political, social, and environmental situations (Khoshsima & Hashemi Toroujeni, Citation2017; Mohammadian & Norton, Citation2017; Sadeghi & Richards, Citation2015; Safari & Rashidi, Citation2015; Sheibani, Citation2012; Zarrabi & Brown, Citation2017). Students in language institutes in Iran are much motivated, and they are registered for the specific aim of learning language whereas school students are studying language besides other subjects like Math or Physics that most of the time is considered more important than language subject. So, language institute teachers face many motivated learners registered for the aim of the language learning itself (Khoshsima & Hashemi Toroujeni, Citation2017). Moreover, in Iranian society participating in language classes out of school can be done as fun. The language learners, especially the youth and female learners, dare to be outside and experience a new world. They feel more confident in learning a language (Mohammadian & Norton, Citation2017). Whereas language institutes are mostly located in cities, there are lots of less-equipped schools in villages where the social, cultural, and economic situations decide about what and how teachers should develop in their professional life to be accepted and survive. For example, the provincial government approved language teaching approach in schools in recent years have been a full version of CLT (see Anani Sarab, Citation2010), but language teachers at schools are mostly dissatisfied with the lack of technology and equipment necessary for accomplishing even a weak version of CLT (Dahmardeh, Citation2009; Maftoom, 2002; Razmjoo & Barabadi, Citation2015; Safari & Rashidi, Citation2015; Zarrabi & Brown, Citation2017). Language institutes, on the other hand, are more or less equipped for CLT-based teaching. In a similar vein, in his list of impediments in the way of implementation of CLT in the Iranian EFL context, Maftoon (Citation2002) mentions the school culture which puts emphasis on repetition, memorization, and accumulation of knowledge and the negative washback of the university entrance exam which has perpetuated the focus on grammar, vocabulary and to some extent reading in the high school English curriculum (Anani Sarab et al., Citation2016).

As thus, based on the differences, different environmental workplace expectations and learning opportunities are waiting for the teachers in these two settings. The results that came from this study clearly showed the same traits of these settings as the school language teachers showed better MLK because they are more involved with a more explicit form-focused instruction. That is, this situation, possibly, has been turned out to be a blessing in disguise in favor of the school teachers developing more knowledge about language than institute EFL teachers.

More support in this regard comes from the interview results, which suggest Iranian school teachers’ priority at MLK can pertain to the backwash effect of the UEE on both teachers and students (Ghorbani et al., Citation2008). The school students should be provided with more explicit rules and instructions to be ready to pass the UEE, which is held in Iran after twelve years of schooling once a year (Farhady & Hedayati, Citation2009). Dahmardeh (Citation2009) notes that because the majority of language tests in Iran do not assess communicative language content, “teaching communicative skills remains a neglected component in many foreign language classrooms” (p. 9), and school teachers focus their pedagogy on the explicit teaching of grammar rather than English communication skills (Baleghzade & Farshchi, Citation2009). On the other hand, EFL teachers in institutes may believe in less need for MLK and using that in the classrooms.

Finally, teachers as a learning community (Collinson & Cook, Citation2013; Harris & van Tassell, Citation2005) develop specific knowledge in the workplace based on the specific educational goals, leading the learners toward achieving those specific goals. Looking from another perspective, this shows how different language learning settings are significant, influencing, determinant factors in developing and shaping EFL teachers’ knowledge.

To address the differences between participants’ performance in productive and receptive tasks of MLK, the results revealed that both groups’ receptive knowledge of MLK was better than their productive MLK. The productive tasks asked the test-takers to provide explanations of grammar rules or terms. The criteria for the adequate formulation of an appropriate rule normally involve the use of metalinguistic terminology, and term production entails producing the grammar term for the underlined item in each of the sentences. On the other hand, the receptive task requires choosing from multiple options offering explanations of the target rules or selecting the item that exemplified the grammar term requested. The variation in teachers’ productive and receptive MLK can be interpreted in terms of cognitive load, as argued by Andrews and McNeill (Citation2005), and Tsang (Citation2011). The task of explaining rules places higher cognitive demands on subjects, requiring them to explicate the rule that has been broken and employ appropriate metalinguistic terminology to explain why (Andrews, Citation1999a; Andrews & McNeill, Citation2005; Tsang, Citation2011), whereas the receptive task required the participants to merely select those rules that best explained each error from among the four options provided for each sentence. In the same line, based on the interview results, both groups of teachers supported the findings that MLK production is a more struggling area than MLK recognition. Also, some teachers believed that producing MLK is closely related to their proficiency level, and knowing terminology did not help them a lot in this regard. Discussions on the relationship between MLK and L2 proficiency have been done in several studies, but the results are still inconclusive (Gutiérrez, Citation2013; Hu, Citation2011). For example, Elder et al. (Citation1999) found weak or no correlations between MLK and L2 proficiency. On the other hand, Renou (Citation2001) found a strong correlation between MLK and L2 proficiency measured as knowledge of grammar, structures, and vocabulary.

A noteworthy finding after qualitative data analysis was that the overall estimation of both groups of teachers of their MLK was an overestimation, considering the test results in the quantitative part of this study. Nearly half of them were completely satisfied with their MLK, even though most of them did not deny that there are gaps and a need for more development in their MLK. This finding aligns well with Sangster et al. (Citation2013) research which found that student teachers’ levels of linguistic knowledge were generally low, contrasting with their own more positive perceptions about their competence. In the same line, comparing school and institute EFL teachers, school teachers showed more satisfaction with their productive and receptive MLK as many of them believed that it suffices to their classes and the level of the students they taught. The interview results (confessed) support the idea that they had such a positive view of their MLK because they believed that it suits their immediate context of teaching. This is in line with Baleghizade and Farshchi’s (2009) study, which attempted to explore Iranian teachers’ beliefs about the role of grammar and grammar instruction in language teaching in both state high schools and private language institutes. The findings of the study revealed that the teachers’ beliefs in both settings converge more than diverge. However, they reported that the teachers in the two settings were different in some domains, in any case. For example, high school teachers believed in the power of explicit teaching and the role of instruction much more strongly than their colleagues in private language settings. They argued that these beliefs, to a large extent, could be traced back to school teachers’ long experience of teaching textbooks that heavily draw on deductive approaches to teaching grammar.

Accordingly, as Smylie (Citation1995) believed, a broad range of possible learning outcomes for teachers in the workplace can be found, ranging from habitual reaction to reflective practice and inquiry. External and internal pressures can force teachers and schools to change their routines. Routines may restrict the school’s responses to change, but they can also help the school to survive changes in environmental demands and expectations (Hoeve et al., Citation2006 as cited in Imants & van Veen, Citation2010). Routines in teaching tasks have the potential to be impediments and opportunities for workplace learning. For example, school teachers have stopped their improvements in MLK because they believed it suits their immediate teaching context, and they “need no preparation for that before the task” can be considered an impediment for more workplace learning regarding their MLK. In a similar vein, the most salient theme found in school teachers’ responses was their viewpoints about the UEE and its effect on their teaching and, consequently, professional development. It was evident from the responses that school teachers’ knowledge development was directed towards the needs of their students for the UEE preparation. The identification of professional development in workplace contexts depends on the perspective from which learning is analyzed. On the whole, perspectives on workplace learning differ concerning goals, outcomes, rationales, and managerial views (Ellstrom, Citation2001).

Finally, in addition to the superiority of the school EFL teachers in productive and receptive MLK over the institute EFL teachers, this study revealed a shortfall in both groups’ MLK and their awareness of the limitations of their knowledge. Certainly, it is important for teachers to be aware of the extent of their own MLK, so they can identify their weaker areas and actively pursue continuous self-improvement (Andrews & McNeill, Citation2005; Borg, Citation2001). Although the differences between school and institute teachers in their productive and receptive MLK can be attributed to different factors, the findings from the current study accentuate the role that teachers’ immediate workplace can play in their MLK development.

6. Conclusion and implications

The present study offered EFL teachers’ MLK insights in productive and receptive modes in two different educational contexts, including language institutes and high schools.

Based on the study findings, EFL teachers in both contexts, i.e., schools and institutes, are suggested to be more mindful of their MLK, especially the productive facet. However, as institute EFL teachers are suffering more severe MLK gaps, they are recommended to adopt a stronger orientation towards MLK development, balancing attention to explicit and implicit knowledge. Referring to Doughty and Williams (Citation1998) theoretical assertions, there is a need for attention to form in second language classrooms for both settings under investigation in this study. In language institutes in Iran, where the robust version of CLT is the standard approach, focusing on some linguistic features is necessary to help the learners go beyond their current interlanguage competence toward the one that is more target-like and aid to foster the natural processes. On the other hand, in Iranian government schools where the dominant approach is the weak version of CLT, and different educational policies have pushed the language teaching/learning towards more form-focused instruction, again, the need for more attention to form can foster the natural SLA processes and seems necessary for more effective and efficient language learning/teaching experiences. Hence, all of the communicative tasks engaged in language development would pose considerable challenges to the teacher’s metalinguistic awareness.

The findings gleaned from the interview data showed a gap between the school EFL teachers’ estimation of their productive and receptive MLK and their actual performance in the MLK test, which means a lack of awareness of their MLK limitation. Thus, the finding highlights the need to raise more awareness in school EFL teachers regarding their MLK production and reception. It is evident that changes always follow awareness about the need to change as Borg (Citation2001) believed that “work aimed at developing teachers’ KAL [language knowledge] should incorporate opportunities for them to develop and sustain a realistic awareness of that knowledge and an understanding of how that awareness affects their work” (p. 28).

Accordingly, the findings from this study provide an argument for actions by schools, language institutes, and policymakers at the national level to begin to implement preservice and in-service provision to raise EFL teachers’ awareness about MLK and to help teachers develop their MLK further with a focus on their weakness area, i.e., MLK production. Moreover, the remarkable difference between school and institute EFL teachers’ MLK underscores how the teachers’ MLK development can be related to their immediate workplace. This knowledge can pave the way for educators to devise possible ways of meeting the factors integrated into MLK development in these two different contexts. Finally, these actions should, in turn, have a positive impact on classroom practices. The gradually enhanced performance can lead to self-regulation and, thereby, higher self-confidence and learning motivation culminating in professional self-development, as White and Ranta (Citation2002) described as a process that aims to create and develop links between subject-matter knowledge and classroom activity.

It is worth mentioning that, in the present study, the authors do not argue that strong MLK necessarily leads to effective teaching of language. Andrews (Citation2001) and Borg (Citation1999) claim that teachers need appropriate pedagogical skills to use their knowledge to enhance learning in addition to MLK. Thus, language teaching entails integrating pedagogy and subject content knowledge (Borg, 2003; Bartels, Citation2005). While not denying the importance of the broader aspects of teacher language awareness, including the procedural dimension, the present discussion had a narrower focus, concentrating on teachers’ MLK, i.e., the declarative dimension of teachers’ language awareness. To provide more exact data, it is suggested to conduct a classroom observation to explore in-depth where the areas of weakness in teachers’ MLK lay. Research into students’ views of their teachers’ MLK in teaching and learning in the classroom will be helpful, too.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Azam Pourmohammadi

Azam Pourmohammadi is a Ph.D. candidate of TEFL at Shiraz Azad University, Iran. Her main areas of interest are language teaching and learning, teacher education, and psycholinguistics. She has more than 25 years of experience in teaching English to Iranian students.

Firooz Sadighi

Firooz Sadighi is a professor of applied linguistics. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Illinois. He has published numerous articles nationally and internationally, and a number of books independently and collaboratively with colleagues and students. His research areas include first/second language acquisition, second language education, and syntax studies.

Mohammad Javad Riasati

Mohammad Javad Riasati holds a Ph.D. degree in TESL and is currently a faculty member of Shiraz Azad University, Iran. His area of interest is language education. He has published extensively in national and international journals.

References

- Ahangari, S., & Abdi, M. (2017). The metalinguistic and linguistic knowledge tests and their relationship between non-native in-service and preservice teachers. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 6(6), 246–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.6n.6p.246

- Alderson, J. C., & Hudson, R. (2013). The metalinguistic knowledge of undergraduate students of English language or linguistics. Language Awareness, 22(4), 320–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2012.722644

- Almarshedi, R. M. 2017. Metalinguistic knowledge of female language teachers and student teachers in an English language department in Saudi Arabia: Level, nature and self-perceptions [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Leicester.

- Anani Sarab, M. R. (2010). Secondary education curriculum framework for teaching foreign languages: Opportunities and challenges. Iranian Journal of Curriculum Innovation, 35(3), 172–199.

- Anani Sarab, M. R., Monfared, A., & Safarzadeh, M. M. (2016). Secondary EFL school teachers’ perceptions of CLT principles and practices: An exploratory survey. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 4(3), 109–130. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1127350

- Andrews, S., & McNeill, A. (2005). Knowledge about language and the ‘good language teacher.’. In N. Bartels (Ed.), Applied linguistics and language teacher education (pp. 159–178). Springer.

- Andrews, S. (2007). Teacher Language Awareness. Cambridge University Press.

- Andrews, S. J. (1999a). Why do L2 teachers need to “Know About Language”? Teacher metalinguistic awareness and input for learning. Language and Education, 13(3), 161–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09500789908666766

- Andrews, S. J. (1999b). The metalinguistic awareness of Hong Kong secondary school teachers of English. [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The University of Southampton.

- Andrews, S. J. (2001). The language awareness of the L2 teacher: Its impact upon pedagogical practice. Language Awareness, 10(2–3), 75–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410108667027

- Babbie, E. R., & Benaquisto, L. (2008). Fundamentals of social research. First Canadian edition. Nelson Thomson Learning.

- Baleghzade, S., & Farshchi, S. (2009). An exploration of teachers’ beliefs about the role of grammar in Iranian high schools and private language institutes. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 1(212), 17–38. https://elt.tabrizu.ac.ir/article_639.html

- Bartels, N. (2005). Applied Linguistics and Language Teacher Education. Springer.

- Berry, R. (2009). EFL majors’ knowledge of metalinguistic terminology: A comparative study. Language Awareness, 18(2), 113–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410802513751

- Borg, S. (1999). Studying teacher cognition in second language grammar teaching. System, 27(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(98)00047-5

- Borg, S. (2001). Self-perception and practice in teaching grammar. ELT Journal, 55(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.1.21

- Borjian, M. (2010). Policy privatization and empowerment of subnational forces: The case of private English language institutes in Iran. Viewpoints Special Edition: Middle East Institute (MEI) Series on Higher Education and the Middle East, 1, 58–61.

- Collinson, V., & Cook, T. F. (2013). Organizational learning: Leading innovations. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management, 1(1), 69–98. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1111696

- Curriculum and Textbooks Development Office. (2019). English for schools (prospect/vision): Teacher’s guide. http://eng-dept.talif.sch.i

- Dahmardeh, M. 2009. English language teaching in Iran and communicative language teaching [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Warwick.

- Doughty, C., & Williams, J. (1998). Focus on Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

- Elder, C., Warren, J., Hajek, J., Manwaring, D., & Davies, A. (1999). Metalinguistic knowledge: How important is it in studying a language at university? Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 22(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/aral.22.1.04eld

- Ellis, M. (2016). Metalanguage as a component of the communicative classroom. Accents Asia, 8(2), 143–153.

- Ellis, R. (2004). The definition and measurement of L2 explicit knowledge. Language Learning, 54(2), 227–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00255.x

- Ellstrom, P. E. (2001). Integrating learning and work: Problems and prospects. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 12(4), pp. 421–435. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1006

- Farhady, H., & Hedayati, H. (2009). Language assessment policy in Iran. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 29, 132–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190509090114

- Ghorbani, M. R. (2011). Quantification and graphic representation of EFL textbook evaluation results. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 1(5), 511–520. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.1.5.511-520

- Ghorbani, M. R., Samad, A. A., & Gani, M. S. (2008). The washback impact of the Iranian university entrance examination on pre-university English teachers. Journal of Asia TEFL, 5(3), 1–29. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mohammad-Ghorbani/publication/318339948

- Gutiérrez, X. (2013). Metalinguistic knowledge, metalingual knowledge, and proficiency in L2 Spanish. Language Awareness, 22(2), 176–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2012.713966

- Harris, M. M., & van Tassell, F. (2005). The professional development school as a learning organization. European Journal of Teacher Education, 28(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760500093255

- Hayati, A., Vahdat, S., & Khoram, A. (2017). Teacher language awareness revisited: An exploratory study of the level and nature of language awareness of prospective Iranian English teachers. Teaching English Language, 11(1), 69–94. https://doi.org/10.22132/TEL.2017.53531

- Hoeve, A., Jorna, R., & Nieuwenhuis, A. (2006). ‘Het leren van routines: Van stagnatie naar innovatie’ (Learning from routines: From stagnation to innovation). Pedagogische studiën, 83(5), pp. 397–409.

- Hu, G. (2011). Metalinguistic knowledge, metalanguage, and their relationship in L2 learners. System, 39(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.01.011

- Imants, J., & van Veen, K. (2010). Teacher learning as workplace learning. In P. Peterson, E. Baker, & B. McGaw (Eds), International encyclopedia of education (pp. 569-574). Oxford: Elsevier. Ihttps://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.00657-6

- Khoshsima, H., & Hashemi Toroujeni, M. (2017). A comparative study of the government and private sectors’ effectiveness in ELT program: A case of Iranian intermediate EFL learners’ Oral proficiency examination. Studies in English Language Teaching, 5(1), 86–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22158/selt.v5n1p86

- Maftoon, P. (2002). Universal relevance of communicative language teaching some reservation. The International Journal of Humanities, 9(2), 49–54. https://eijh.modares.ac.ir/article-27-7706-en.html

- McNamara, D. (1991). Subject knowledge and its application: Problems and possibilities for teacher educators. Journal of Education for Teaching, 17(2), 113–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0260747910170201

- Modirkhamene, S. (2008). Metalinguistic awareness and bilingual vs. monolingual EFL learners: Evidence from a diagonal bilingual context. The Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 66–102. http://jal.iaut.ac.ir/article_524179.html

- Mohammadian, H.. F., & Norton, B. (2017). The role of English language institutes in Iran. TESOL Quarterly, 51(2), 428–438. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.338

- Mutaf, B. 2019. An Investigation of metalinguistic knowledge of preservice teachers of English in a Turkish context [ Unpublished master’s thesis]. Egitim Bilimleri Entitusu.

- Myhill, D. (2011). The ordeal of deliberate choice: Metalinguistic development in secondary writers. In V. W. Berninger (Ed.), Past, present, and future contributions of cognitive writing research to cognitive psychology (pp. 247–274). Psychology Press.

- Myhill, D., & Jones, S. (2015). Conceptualizing metalinguistic understanding in writing/Conceptualize de la competencia metalingüística en la escritura. Culturay Educación, 27(4), 839–867. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2015.1089387

- Myhill, D., Jones, S., & Watson, A. (2013). Grammar matters: How teachers’ grammatical knowledge impacts on the teaching of writing. Teaching and Teacher Education, 36(8), 77–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.07.005

- Myhill, D. A., Jones, S. M., Lines, H., & Watson, A. (2012). Re-thinking grammar: The impact of embedded grammar teaching on students’ writing and students’ metalinguistic understanding. Research Papers in Education, 27(2), 139–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2011.637640

- Nazarian, S., & Izadpanah, S. (2017). The study of the metalinguistic knowledge of English by students in an intensive and a traditional course. International Journal of English Linguistics, 7(1), 215–216. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v7n1p215

- Nishimuro, M., & Borg, S. (2013). Teacher cognition and grammar teaching in a Japanese high school. JALT Journal, 35(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTJJ35.1-2

- Punch, M. (2009). Introduction to Research Methods in Education. Sage.

- Purvis, C. J., McNeill, B. C., & Everatt, J. (2016). Enhancing the metalinguistic abilities of preservice teachers via coursework targeting language structure knowledge. Annals of Dyslexia, 66(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-015-0108-9

- Rahman, M. S., & Karim, S. M. S. (2015). Problems of CLT in Bangladesh: Ways to improve. International Journal of Education Learning and Development, 3(3), 75–87.

- Razmjoo, S. A. (2007). High schools or private institutes textbooks? Which fulfill communicative language teaching principles in the Iranian context. Asian EFL Journal, 9(4), 126–140. http://www.asian-efl-journal.com

- Razmjoo, S. A., & Barabadi, E. (2015). An activity theory analysis of ELT reform in Iranian public schools. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 18(1), 127–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18869/acadpub.ijal.18.1.127

- Renou, J. (2001). An examination of the relationship between metalinguistic awareness and second-language proficiency of adult learners of French. Language Awareness, 10(4), 248–267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410108667038

- Riazi, A. M., & Razmjoo, A. S. (2006). Do high schools or private institutes practice Communication Language Teaching? A case study of Shiraz teachers in high schools and institutes. The Reading Matrix, 6(3), 340–363. https://doi=10.1.1.608.8202

- Roehr, K. (2007). Metalinguistic knowledge and language ability in university-level L2 learners. Applied Linguistics, 29(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm037

- Sadeghi, K., & Richards, J. C. (2015). The idea of English in Iran: An example from Urmia. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Developmen, 37(4), 419-434. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2015.1080714

- Safari, P., & Rashidi, N. (2015). A critical look at the EFL education and the challenges faced by Iranian teachers in the educational system. International Journal of Progressive Education, 11(2), 14–28. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279202133_A_Critical_Look_at_the_EFL_Education_and_the_Challenges_Faced_by_Iranian_Teachers_in_the_Educational_System

- Saito, Y. (2016). High school teachers’ cognition toward the new course of study. Proceedings of the 17th Annual of the TUJ Applied Linguistics Colloquium, 17, 70–77. Temple University Japan Campus. TUJ Graduate Education Office: Japan.

- Saito, Y. (2017). 「英語の授業は英語で」に関する高校教師の認知調査と授業実践 [High school teachers’ cognition of the policy of “English classes in English,” and their classroom practice]. The Language Teacher, 41(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTTLT41.1-1