Abstract

Any language policy has crucial social implications that impact its successful implementation. The introduction of the bilingual language policy at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) has spurred polemical debate and discussions especially regarding the value of African languages for teaching and learning. This article offers a socio-constructivist analysis of the issues that emerge in the implementation of the UKZN language policy. The study on which it is based employed a mixed methodology drawing on secondary as well as primary data collected by means of semi-structured interviews and questionnaires administered to staff and students at two UKZN campuses. Simple random sampling was applied to enroll 16 students while purposive sampling was used to select nine academic staff for the study. The findings reveal that although the bilingual language policy has inherent social value, uncertainty persists with regard to its short and long-term economic significance. This calls for deeper reflection on the social implications of the language preferences of the institution’s staff and students who are directly affected by the policy.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Any language policy has crucial social implications that impact its successful implementation. The introduction of the bilingual language policy at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) has spurred polemical debate and discussions especially regarding the value of African languages for teaching and learning. This article offers a socio-constructivist analysis of the issues that emerge in the implementation of the UKZN language policy. The study used secondary as well as primary data collected by means of semi-structured interviews and questionnaires administered to staff and students at two UKZN campuses. The findings reveal that although the bilingual language policy has inherent social value, uncertainty persists with regard to its short and long-term economic significance. This calls for deeper reflection on the social implications of the language preferences of the institution’s staff and students who are directly affected by the policy

1. Introduction

Social inequalities are deeply embedded in all spheres of life in South Africa and the higher education system is no exception. Class, race, gender, institutional and spatial inequalities that were entrenched during the apartheid era profoundly shaped and continue to affect the country’s higher education system (Lombard, Citation2017; Badat, 1999). In line with its political principles, apartheid language policies promoted exclusivism and prejudice (N.M. Kamwangamalu, Citation1997). Attempts to transform this system, including policy formulation and implementation, are framed by the overall social goals of transcending the apartheid social structure with its deep social inequalities and institutionalizing a new social order (Cele, Citation2001; Department of Higher Education and Training, Citation2015; Nudelman, Citation2015). Several scholars have contributed to the discourse on transforming the higher education system, specifically language policies, by advocating for the inclusion of African languages as a medium of instruction (N.M. Kamwangamalu, Citation1997; Mashiya, 2010; Swaffer, Citation2014; Diab, Matthews and Gokool, 2016; Mkhize and Hlongwa, 2014; Webb, 2002; Wade, 2005).Footnote1

The language of learning and teaching (LoLT) is considered an important tool in reducing barriers to learning in the academic environment and for increasing access to learning. In South Africa, the right to receive education in the language of one’s choice is an important aspect of efforts to overcome the apartheid legacy that used the LoLT to perpetuate oppression and inequality. South Africa is a multilingual country with 11 official languages, including English and Afrikaans, and nine indigenous languages: isiNdebele; Northern Sotho; Sesotho; siSwati; Xitsonga; Setswana; Tshivenda; isiXhosa and isiZulu. These indigenous languages are the mother tongue of the majority of South Africans.Footnote2 However, during apartheid, English and Afrikaans were privileged as the two official languages which functioned on an equal basis at the national level (Lombard, Citation2017).

Following the demise of apartheid, South African indigenous languages were officially elevated to an equal status with English and Afrikaans in government institutions. These African languages are now being promoted in teaching and learning in higher education institutions. The Language Policy for Higher Education (2002) stipulates that universities should promote African languages that are dominant in the provinces where they are situated. For example, about 80% of KwaZulu-Natal’s population speaks isiZulu, while the same percentage speaks isiXhosa in the Eastern and Western Cape. Sepedi is the most-spoken language in Limpopo, and siSwati is spoken by 27.7% of the population in Mpumalanga Province (Language Policy for Higher Education, 2018). About 23%, or nearly 11.6 million South Africans speak isiZulu (Department of statistics South Africa, Citation2018).

Situated in KwaZulu-Natal province where isiZulu is the most widely spoken language, UKZN also has a high number of isiZulu speakers among its student cohort. The university’s reconsideration of its language policy in line with recent education initiatives led to the implementation of a bilingual policy in 2006 that was revised in 2014 (Ndebele & Zulu, Citation2017) It incorporates isiZulu as a medium of communication for both academic and communication purposes and states that, “The policy for the University makes clear the need to achieve for isiZulu the institutional and academic status of English” (University of KwaZulu-Natal, Citation2014:1). It is believed that isiZulu can be successfully used for official purposes, as it is spoken by the majority of UKZN students. The primary focus of the UKZN language policy is to ensure that students achieve academic success.

Against this backdrop, this article uses UKZN as a case study to analyze students and staff’s perceptions of the social value of the implementation of the language policy. It draws on primary data sourced from questionnaires, and interviews with 25 participants on two of the university’s campuses (Howard College and Pietermaritzburg). Nine staff members were purposively selected while 16 students were randomly selected from both campuses across different disciplines. The article begins with a review of the literature on the social construction of language (policy) in South Africa. This is followed by a brief outline of the methodology and a discussion on the findings. The final section interrogates the social value of the UKZN language policy based on the findings, while the conclusion offers recommendations on the implementation of the second phase of the language policy.

2. Literature review

The advent of democracy in South Africa in 1994 resulted in increased linguistic and cultural diversity among the student population in higher education. Mindful of past discriminatory policies towards speakers of languages other than English and Afrikaans, the government has developed language policy frameworks with an emphasis on multilingualism and equity of access and success for all students in higher education (Department of Higher Education and Training, Citation2015). These include the N.M. Kamwangamalu (Citation1997) as amended, the Language Policy for Higher Education (2002) and, more recently, the White Paper for Post-School Education and Training (2013). The post-apartheid language policy provided for the legitimisation of African languages in higher education. However, evidence shows that the use of English as a common LoLT continues to create a differential educational experience and treatment for students who are speakers of indigenous African languages, thus compromising their access to higher education (Department of Higher Education and Training, Citation2015). While other factors are linked to students’ access and performance in education (e.g., their schooling background and socio-economic status), studies have illustrated that the utilisation of a student’s language in learning can facilitate cognition and consequently lead to success in their studies (Cummins, 1981, 2000; Dalvit, 2010; Dlodlo, 1999; Kapp & Bangeni, Citation2011).

As part of broader national efforts to transform South African higher education, UKZN introduced a new language policy in 2006 which included isiZulu as a medium of instruction in addition to English, which remained the main medium of instruction (N.M. Kamwangamalu, Citation1997). According to the policy:

The university will continue to use English as its primary academic language but will activate the development and use of isiZulu as an additional medium of instruction together with the resources (academic and social) that make the use of the language a real possibility for intervention by all constituencies in the University. (UKZN, University of KwaZulu-Natal Institutional Intelligence, 2017: 1).

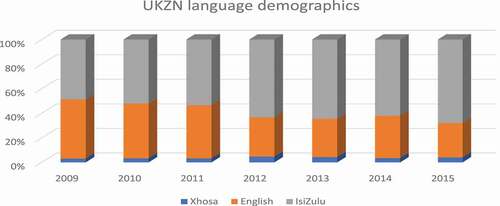

The aim of the policy is to give students who are isiZulu speakers the opportunity to acquire academic training in their mother tongue. Thus, the policy sought to achieve linguistic and cultural harmony amongst students and staff (University of KwaZulu-Natal, Citation2014). As shows, the proportion of isiZulu speakers at UKZN increased from about 43% in 2009 to 75% in 2015. The university offers an access programme for undergraduate first-year students from disadvantaged school backgrounds who are mainly isiZulu speaking. Furthermore, it is situated in a predominately isiZulu speaking province (University of KwaZulu-Natal, Citation2016). As a historically white South African university, UKZN was a site of anti-apartheid resistance. It refused to discriminate against students based on race and opened its doors to all. It is therefore not surprising that its language demographics have changed over the years as reflected in its language policies that seek to redress the inequalities and injustices of the past (University of KwaZulu-Natal, Citation2014).

(Source: UKZN, 2017)

Several studies have been conducted on staff and students’ language perceptions. For example, Teeger. (Citation2015) examined teachers and students’ views on language, race and socialization in the post-apartheid South African educational system. Naidoo et al. (Citation2017) investigated whether UKZN’s compulsory language module promoted social cohesion. The author’s concluded that the coercive strategy of requiring students whose mother tongue is not isiZulu to learn the language was only partially successful. Naidoo et al. (Citation2017:2) argue that, “UKZN was somewhat shortsighted in that the attempt to promote social cohesion was in a compartment; there was no obvious connection between the compulsory language module and attempts to integrate the interaction between mother tongue and non-mother tongue speakers of isiZulu at the institution”. S. Wright’s (Citation2016) study on why European language speakers speak the way they do, covered language learning imposed by political and economic agendas as well as language choices entered willingly for reasons of social mobility, economic advantage and group identity. Fan (Citation2011) investigated the links between socio-economic status and achievement and argued that students from different social backgrounds have access to different types of schools (public vs. private) and to varying degrees of extracurricular exposure to the target language (e.g., private tuition, learning resources, and study abroad). He noted that this not only affects final language learning outcomes but also influences motivation to learn, self-regulation and students’ self-related beliefs.

2.1. Social construction of language and language policies

Sociologists believe that the social construction of a population has a powerful influence on public officials and shapes the agenda and design of policy (Cele, Citation2001; Subtirelu, Citation2013; Tsui, Citation2017). Social constructions are embedded in policy as messages that are absorbed by citizens, and affect their orientation and participation patterns (Tsui, Citation2017). During the apartheid era, proficiency in English and Afrikaans was an emblem of educational and social status. Those who were proficient in English were socially recognised and economically positioned on far higher levels than those with limited or no proficiency (Cele, Citation2001). Naidoo et al. (Citation2017) and N. M. Kamwangamalu (Citation2016) observe that English enjoys a high status among speakers of indigenous South African languages because of the perceived economic power and progress associated with the language. It must however be noted that this phenomenon is not peculiar to South Africa, but a global trend witnessed in both Africa and other non-English speaking countries.

This situation persists in South African communities even though African languages are now officially recognised (Poggensee, Citation2016). Among other factors, this social construction of the hegemony of the English language prompted UKZN to revise its language policy.Footnote3 The University’s bilingual policy is designed to benefit isiZulu speakers as the socially constructed group targeted by the policy. Since language policies are socially constructed at the policy formulation stage, they include specific target populations while excluding others. The UKZN language policy is seen as beneficial to isiZulu speakers who form most of the student population, and as such, is believed to have the power to engender social cohesion. However, ironically, it is evident that such a policy can result in exclusivism, albeit unintentionally. The ideological, historical and social challenges that confront the UKZN language policy suggest that the prestige IsiZulu enjoys over other indigenous languages is likely to attract resentment, particularly when the language is imposed on students who simply want to pass the isiZulu module and are not interested in its social cohesion value. For this reason, Naidoo et al.’s (Citation2017:2) assertion that “mother tongue speakers of English may find it impractical to be compelled to study isiZulu”, is apt.

While social cohesion is a strong motivation in learning a language, economic factors also play a critical role. Kormos and Kiddle (Citation2013) examined the role of socio-economic factors in Chile as a motivation for learning English as a foreign language. The study focused on how foreign language competence opened new opportunities and assisted in breaking social barriers for students from disadvantaged communities. It highlights the importance of social context in influencing foreign language learning outcomes. The authors attribute social context to the learners’ social-economic backgrounds regarding their parents’ educational and income levels that may support learning a foreign language or otherwise. For instance, learners from a disadvantaged background are said to be less motivated to learn a foreign language for the purpose of travelling to foreign countries because their families’ socio-economic situation might make this highly unrealistic. They are more likely to be inspired to learn a foreign language for its use in social spaces (Kormos & Kiddle, Citation2013).

The UKZN language policy anticipates that isiZulu will help to promote social cohesion among students and the university community. However, language users are sometimes stigmatized due to others’ perceptions and the social position of the language when compared to other languages (Murray, Citation2002). Furthermore, language users consider the group to which the undervalued language belongs. According to Swaffer (Citation2014), the undervalued language group represents an out-group in relation to the dominant group in society. For this reason, the nine indigenous South African languages are held in less regard than English and to a lesser extent, Afrikaans. In support of this notion, Ramsay-Brijball (Citation2003) noted that isiZulu students on UKZN’s Westville campus refused to speak isiZulu in a bid to escape the stigma of being considered “old fashioned”. This is corroborated by Naidoo et al. (Citation2017) who found that only 7% of their respondents chose the compulsory IsiZulu language module of their own free will. This is not surprising given that the use of language can be associated with the “identity adjustment made to increase group status and favourability” (Edwards, 1985:152). Arguing that language speakers seek to express a mixed identity and therefore choose to use two or more languages concurrently, Zungu (Citation1998) contends that isiZulu is often promoted as a marker of ethnic identity when the speaker is interacting with other ethnic groups in the Southern African context. isiZulu-speaking students use these languages for different purposes. Therefore, isiZulu and English carry varying social constructions amongst UKZN students. While English remains a language of social prestige and modernity, isiZulu is perceived as one used to prove and own one’s ethnicity. In this context, the home language, or mother tongue, is utilized to create an explicit sense of self-identity, communal belonging, and cultural orientation (Gernsbacher, Citation2017). It is used for private communication, colloquial discourse and for localized, everyday exchanges.

According to Swaffer (Citation2014), social groups that are often stigmatized in South Africa are those that have historically been treated inhumanely, particularly African people. These groups are not usually regarded as the in-group or the dominant group in society although statistically, they are in the majority. A social group’s dominance is determined by its economic influence (Swaffer, Citation2014). While all nine indigenous South African languages constitutionally have equal status with English and can be used as LoLT and also for official communication, the reality is that “the hegemonic nature of English, imposed through apartheid and colonialism in South Africa, has resulted in the unquestionable prestige of English, which has the effect of distorting educational possibilities and weakening the value which African languages possess” (Naidoo et al., Citation2017:6). Most speakers use African languages for social purposes, usually at home. According to Tajfel (1981), a given social context involving relations between salient social groups provides categories through which individuals learn to recognize linguistic or other behavioural cues, allocate others and themselves to category membership and learn the valuation applied by the in-group and salient out-group to this membership. One of the most compelling explanations may also possibly lie in the richly amorphous nature of the term, “home language”.

As Murray (Citation2002:438) points out, “Parents trust that the home language is acquired quite accurately at a domestic level; it is … the task of the school to teach the language of wider verbal exchange”. However, there seems to be little need to expand the scope of the home language beyond social capabilities. Instead, English is regarded as necessary for higher level communication, advanced learning and training, and economic transactions. Acceptance of English as a lingua Franca is not only a South African but a global phenomenon. Studies have shown that languages have become endangered because of the spread of English and as it continues to spread throughout the world, there is a greater chance that other languages will become extinct (Crystal, Citation2003; Mauranen, Citation2018; Mufwene, Citation2015; Nettle & Romaine, Citation2000). Scholars such as Mazrui (2004) have argued that, as a global language, English serves to perpetuate imperialism and domination, resulting in the marginalization of African people and the erosion of their languages and cultures. As Poggensee (Citation2016: 19) puts it, “English as a result of globalization has negatively impacted other minority languages and cultures, including ones in Africa”. However, Mufwene (Citation2015:16) believes that the appellation of “killer language” given to English fails to appreciate its value as a communicative tool that enables access to education, employment, and other services.

3. Methodology

The study was conducted on UKZN’s Howard College (Durban) and Pietermaritzburg campuses which were purposively selected due to the researchers’ access to and reasonable familiarity with the terrain. A mixed-method approach was employed. The primary data were collected through semi-structured interviews and questionnaires, while secondary data were sourced from relevant policy documents, and government reports and frameworks which were primarily used to offer historical background in the literature review. The official documents consulted included the National Language Policy Framework, 2003; Education White Paper 3, 1997; Language-in-Education Policy, 1997; Language Policy for Higher Education, 2002; The Development of “Indigenous African Languages” as Mediums of Instruction in Higher Education, 2003–2004; the Policy Framework for the Realisation of Social Inclusion in the Post-School Education and Training System, 2016; Green Paper for Post-Secondary School Education and Training, 2012; and the Report on the use of African Languages as Mediums of Instruction in Higher Education, 2016. The UKZN language policy and language plan was also scrutinized. The documents were accessed from the South African Department of Education repository and the UKZN repository.

Through various sampling methods, a total of 25 respondents participated in the study. Simple random sampling was used to enrol 16 students while nine academic staff were enrolled through purposive sampling. This included four staff selected from the School of Social Sciences (two each from Pietermaritzburg and Howard College), two each from the School of Education and the School of Arts (both in Pietermaritzburg as there is no School of Education in the Howard college), and one member of the UKZN Language and Planning Committee (from the Howard college). The inclusion of staff for the interviews and questionnaire was based on their considerable knowledge of the UKZN language policy, and more importantly, their willingness to participate in the study. The staff were first invited to participate via email and afterwards face to face appointments were scheduled. Similarly, the 16 students included in the study were selected from the registered enrolment list for the 2017 isiZulu compulsory module “Introduction to isiZulu” on both campuses.

Once ethical approval was received, the lecturers for this module on both campuses were approached for access to student participants. With the permission of the lecturers, students were informed of the objective of the study during one of the classes while the researchers solicited their participation. Due to constraints of resources, Emails were sent to 20 students conveniently sampled from each list of registered students by selecting a student from every five count of students. In total, 16 responded and consented to participate in the study. This convenient sample of students was guided by resource constraints, and limitation of time to complete the study. Although the student sample size may not be representative of the entire student body, the authors considered that the selected sample population provided fair measure of students directly affected by the UKZN language policy since they were registered for the compulsory IsiZulu module. Another reason for focusing on this limited category of students was that they were primarily first-year, newly registered students who were unlikely to have been affected by the controversy generated by the language policy prior to their admission. Nonetheless, only 16 students volunteered to participate out of a class population of 62 students spread across both Pietermaritzburg and Howard College. This confirms Naidoo et al.’s (Citation2017:2) assertion that “Although the UKZN language policy encouraged the promotion of isiZulu for non-mother tongue speakers, there was no surge in the number of learners wanting to study the language”.

Twenty-five semi-structured interviews were conducted, using an interview schedule with ten standard questions. The interviews with staff participants lasted between about 30 minutes, while the interviews with students each took five about 20 minutes. Following the completion of all the interviews, the students and staff were asked to complete a questionnaire that included 27 close-ended questions and did not require additional information to be provided. The data from the questionnaire was entered into SPSS software and frequency tables were generated. Since this article uses data from an earlier study, the authors only relied on collected data that were relevant to the study’s objectives. The data from policy documents and the semi-structured interviews were analysed using content analysis, textual analysis and the constant comparative method of analysis. This involved coding, classifying and making meaning of the collected data to highlight the important messages, features or findings. Constant comparative analysis was used to compare information gathered from multiple sources. This involved taking one piece of data (interview, statement, and theme) and comparing it with other data that may be similar or different to develop conceptualizations of the possible relations between various pieces of data (Thorne, Citation2000). This approach was helpful in identifying the emerging themes that guided the discussion of the research findings. Historical documents (higher education policies and the UKZN language policy), the relevant literature and narratives were textually analysed to make inferences on the most likely interpretations that might be made from the text and correlated with the primary data. As the research made use of a variety of quoted texts, it was necessary to use textual analysis to gain valuable insight into the information gathered.

Ethical approval was granted by the UKZN Research Office (HSS/1981/016 M) while gatekeeper’s permission was received from the Registrar’s Office. Through an informed consent form, participants were informed of the study’s objectives and the importance of their contributions. Before each interview, participants were also informed of their right to withdraw at any time. The research did not include activities that compromised the physical or emotional well-being of participants and confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed.

4. Key findings and discussion

The students and staff that participated for the study were asked a range of questions that measured their language preference for isiZulu or English in relation to the following contexts: social, learning materials, consultations, seminars, tutorials, lectures, texting, written work, and meetings. presents the data collected through the questionnaire. It shows that the students’ language preference on campus slightly contradicts the expectations of the UKZN language policy. Their responses suggest that the use of only isiZulu as the LoLT is undesirable, with the highest preference level of 24% for isiZulu as the language for texting while the lowest preference of 2% is for its use in learning material, signifying students’ unwillingness to engage in learning through the aid of isiZulu. The results also show that while many of the students preferred to use English in aspects relating to teaching and learning, fewer were willing to use isiZulu on its own or together with English (see ). The responses suggest a very low preference for a bilingual language policy compared to English only as the LoLT. For instance, 78% and 80% of the students preferred English for lectures and written work, respectively, compared to 10% and 9% who were in support of isiZulu. This suggests that, although students see the policy as socially empowering, they are aware of the limitations its implementation might impose on their academic performance and job prospects after graduation. This is because English is still privileged over isiZulu in the current social-political and economic order.

Table 1. Language preference on campus (students) N = 16

Table 2. Language preference on campus (staff) N = 9

Although the students’ responses on aspects of the LoLT were low, of significance is the fact that the social value of isiZulu received more positive responses with regard to a bilingual approach to official meetings (34%) and socializing with peers (40%).

The responses from the staff corroborate students’ perceptions, with the majority preferring the use of only English as the LoLT. All of the responses for English only as a medium for teaching and learning were above 50% with the lowest being 55% (social communication) and the highest 83% for learning material. Sixty-nine per cent of the staff opted for English as the preferred medium for consultations, while only 15% and 16% opted for isiZulu and both languages, respectively, for the same purpose. Moreover, 80% of the staff chose English for student assessment, while 10% preferred either both languages or isiZulu. As with the responses from students, most of the staff favoured an English medium platform for all questions on teaching and learning, while a slightly lower percentage (30%) chose isiZulu only for social purposes including collegial communication or interaction with students. This corresponds with 12% of the respondents who chose isiZulu and 13% who preferred both languages for meetings.

These findings concur with those of Turner (2012) who concluded that isiZulu speakers tend to use English, although the reason was not revealed. As Swaffer (Citation2014) concede, a language that has yet to be accorded full academic status may be less preferred in academic institutions. This could explain why many students predominantly use English rather than isiZulu, as they may feel it is an appropriate language academically and socially. Students sometimes regard isiZulu as an inferior language in an academic environment even for social purposes because they view the university as a place to prove their intellectual capability and the best way to do so is with European languages (Turner, 2012). Therefore, UKZN would seem to have legitimized social exclusion or discrimination when it adopted a language policy that implicitly states that to actively participate in an isiZulu community, one must communicate in isiZulu.

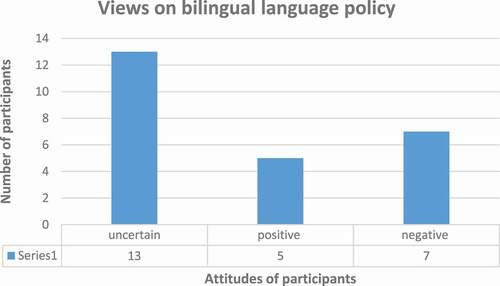

However, the most distinguished thread in the findings was the collective notion of uncertainty expressed by the majority of staff and students towards the introduction of bilingual language policies in higher education. below indicates that 13 of the staff and students were uncertain about the positive impacts that bilingual language policies have in education. These respondents did not indicate whether their view was positive or negative. In contrast, five of the respondents indicated that they held positive views while seven held negative views towards the idea of bilingual language policies.

The general reason behind this uncertainty was based on the view that currently, many high schools in South Africa do not use bilingual language policies; therefore, using a dual medium at university level seems problematic. For instance, Respondent 1 (student) indicated that:

My concern with such a policy is that which additional language will be considered as the additional language to be used alongside English, because we are so used to English since it is used everywhere.

Another isiZulu-speaking student (Respondent 4: student) remarked that:

I am Zulu, I love my language but all my life I have approached education using English, I think I would battle now to approach education using my language.

The concerns raised by these respondents reaffirm Lafon’s (2011) suggestion that introducing a compulsory bilingual language policy at university level is rather late in the learner’s career. As such, there needs to be synergy in language policies at the basic education level (primary and high schools) and the university level. This would help to avoid the seeming confusion when a learner needs to adjust to English only throughout their first 12 years of primary and high school education and then transition to bilingualism at university.

.Whilst scholars such as Ridge (2000) believe that mother tongue education is most appropriate in South Africa’s multilingual environment, Respondent 13 (staff) expressed a different opinion:

In theory, the higher learning language policy is excellent because there are students coming from rural backgrounds who do not have a clue about English use. When they reach varsity, they have to be forced into a dominant use of English. This poses a challenge as it decreases the students’ academic performance, as they are unable to understand what is required of them. There is a challenge with language policy because universities must have tutors and lecturers who can speak those languages. Most universities in South Africa … many lecturers especially here (UKZN) are foreign and are not equipped to teach UKZN African students.

This statement underscores the uncertainties surrounding bilingual language policies in higher education in South Africa. Respondent 5 (staff) echoed this line of thought:

My concern regarding bilingual language policies in higher education is that we really do not know what it entails. It is, on the one hand, good to know that the South African government has made a provision in the Constitution for the promotion of neglected African languages in the academic space. It is good that the government sees the need for African people to be given the option of learning in an African language; however, I share many feelings of worry. We do not have a model of how a bilingual higher education looks like and how it functions or should function. Since this is a new model that I personally have not seen being implemented elsewhere, I fear how it will turn out at the higher education level especially. Higher education is too diverse racially and linguistically; unlike lower primary and secondary, higher education institutions accept more international students than lower primary would. I foresee a problem in instituting an African language in a linguistically diverse environment like the South African higher education institution.

The concept of bilingual language policies for education purposes is therefore contested due to the uncertainties surrounding it, with only two respondents perceiving the policy as positive. Respondent 7 stated that, “Bilingual language policies are good because I will get to express myself with a language that I am most comfortable with and I am not compelled to use only English”, while Respondent 9 said that “bilingual policies will create a more inclusive education system that is able to be relevant to those that struggle with English”.

These statements underscore the objective of the policy:

At our University, students whose home language is isiZulu form an important and growing language group, reflecting the fact that isiZulu speakers are by far the largest single language group in KwaZulu-Natal. The University therefore has a duty to provide a linguistic and cultural ethos favourable to all students. (UKZN, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Citation2014:2). … There is a need to develop and promote proficiency in the official languages, particularly English and isiZulu … . Proficiency in isiZulu will contribute to nation building and will assist the student in effective communication with most of the population of KwaZulu-Natal. This policy seeks to make explicit the benefits of being fully bilingual in South Africa (UKZN University of KwaZulu-Natal, Citation2014:2).

N.M. Kamwangamalu (Citation1997) suggested that isiZulu speakers themselves should adopt a more positive attitude towards the language.

The positive impression of the policy was shared by Respondent 4 (student):

When it comes to choosing a language in which you pursue your career it also depends on the setting and the message you are trying to get across using that language. For instance, there are colleagues of mine who did their PhDs in China and they had to take a module in Mandarin language, which is the main language in China, and their PhDs were written in Mandarin and not English.

The responses show that some regard bilingual language policies in education as an opportunity, while others see them as a threat and trap. Tupas (Citation2015) highlights that conflicted perceptions exist of bilingual language policies because of inherent beliefs regarding their value. Tupas (Citation2015) investigated multilingual societies in Southeast Asia. Although these countries are multilingual, the study identified the trend of “multilingual hierarchies”, where languages do not have equal value and status (Tupas, Citation2015). For instance, Singapore is multilingual but with a linguistically tiered environment, where English is the most preferred and spoken language. Thus, in a multilingual setting, not all languages will be preferred and utilized equally

5. Interrogating the social impact of the UKZN bilingual policy

The social purpose of the UKZN language policy is geared toward ensuring that the English language does not constitute a barrier to success in higher education. According to the territorial view of language rights, people anticipate gaining access to public services (including higher education) through a predominantly spoken/used language (Crystal, Citation2003). As isiZulu speakers are in the majority in the KwaZulu-Natal province, the language has the potential to bring about social cohesion among students and staff (Chen, Citation2012). This view was expressed by one of the student (respondent 11) who suggested that the bi-language policy approach made them pleased with the isiZulu language:

[This policy makes me to be proud of my language, for Zulu is not a language that you should look down upon. What is important about this policy is that here in KwaZulu-Natal majority of African people in this province speak Zulu. Therefore, the policy is fitting as it allows the majority Zulu speakers a right to use their language].

As the findings in this study demonstrate, despite the potential of the UKZN language policy, it is very important to first address the fears accompanying its introduction and implementation. An institution such as UKZN with a mix of multilingual local and international demographics will likely encounter challenges in trying to assign a specific language belonging to a certain ethnic group. For instance, one student (Respondent 2) made an example of such challenge that they observed as well in Zimbabwe:

I have noticed that the people on campus enjoy speaking their languages for social purposes. My UKZN policy perspectives stem from a political point of view and personal point of view. There are things better explained in isiZulu. Political level it is marginalizing people especially international for instance, in Zimbabwe there were lecturers who spoke in Shona it dismissed students to come to class because they did not understand Shona. On other hand people do struggle with English however can do well in other subjects, people should not be excluded based on language.

Since the language policy is primarily aimed at promoting isiZulu language and culture, it implies that non-isiZulu speakers are expected to interact socially with isiZulu speakers within the university (UKZN, 2006). Studies show that it is easier to learn a language when it is used in both social and academic contexts. However, our findings show that the bilingual language policy has the tendency to bring about tension because it appears that students do not prefer isiZulu for academic purposes.Footnote4 Such sentiments were echoed by two students during the interview by Respondent 14 and 4:

IsiZulu in my view, lacks academic value as it stands because acquiring a qualification in isiZulu confines me to KZN only and I personally have not seen the academic purpose for doing my qualification in isiZulu. [Respondent 14]

The UKZN language policy is good on paper but I have doubts about its practicality. I personally have not seen much isiZulu speaking academic staff in my department, which would mean the university, would have to employ those who can speak the language. In addition, we need to consider that learning a language really takes time so while we wait for our lecturers to learn isiZulu, we would still be required to communicate in English which we cannot escape. Therefore, it is better to be equipped in English because we already know our mother tongues. [Respondent 4]

Such sentiments were captured earlier on in where 70 % of the students preferred academic learning to take place in English only.

South Africa has a long history of the dominance of English in certain academic institutions and government structures, which has necessitated the need to mainstream isiZulu (in this context of the study) and other African languages in the academic domains. For instance, linguistic expert (respondent 13) expounded on the need for African languages to penetrate domains of education:

It is very important to use mother tongue at higher education level because every language carrier’s knowledge especially to the user of that language. Students who struggle to access knowledge based on their lack of comprehension of the English language should not be deprived to access language in their own languages. Demographics at UKZN compel that isiZulu be adopted to be used aside the English language importantly because transformation is a national imperative the use of isiZulu fosters that transformation. The UKZN language policy therefore is an important in terms of including students to equally participate in the higher education and allows African languages to be seen as imperative in the higher education system.

In this statement shared above it is evident that the UKZN language policy is not only important for the socialization process but has an important academic responsibility to enhance access knowledge for the users of the language. According to Alexander (Citation2013) academic institutions have their own cultures and norms since most students belonging to these institutions have diverse languages, the social setting of the universities dictates which languages are prioritized for socialization and academic learning.

According to Dolby (Citation2001), race and identity were historically used to structure the world, including the university. Although race and identity are currently being used to create an inclusive social environment in South African higher education institutions, Asmal and James (2003) note that there is still a wide gap between policy mandates and social reality. As Pillay and Ke Yu (Citation2015) point out, the UKZN language policy binds students to take a course in isiZulu, but this does not mean that they are forced to speak isiZulu during their social interaction. Only an interest in the language will drive them to use it. This supports Swaffer’s (Citation2014) argument that a language whose presence is felt and seen everywhere usually succeeds in dominating. Therefore, as noted by UKZN staff members, the challenge is that isiZulu is not as visible because English still dominates. According to Respondent 5 (staff):

I find it a bit obscure to expect both students and staff members to interact on an academic level using isiZulu whilst currently there is no literature in our own disciplines and fields of study that is printed in isiZulu. So, a student is expected to read a history or psychology textbook that is written in English and interact with the lecturer in isiZulu. I think that is where the problem begins about this policy. For, if the claim is that students are not fluent in English, then the language in which the literature is written must be the same as the language spoken.

Rudwick and Parmegiani (Citation2013) study on first-year UKZN students’ attitudes towards English and isiZulu found that students were more concerned about the economic benefits isiZulu offers in terms of their career. Despite widespread support among Zulu-speaking students for the new UKZN language policy in theory, the findings show that many reported a reluctance to study in their mother tongue due to the effect this might have on their job prospects. They thus confront the dilemma of choosing between the social value and the economic implications of the language policy.

It is therefore perhaps incomprehensible to envisage isiZulu as an established language like English, which is widely used and spoken. IsiZulu lacks an economic function in South Africa, which already categorizes it as a language only suitable for social purposes. However, the economic value and social prestige associated with English do not imply that other African languages should be ignored and also do not mean that these languages are unimportant. As Grin (Citation2006) avers, all languages have some economic value although some are more valuable than others. It is for this reason that the language which carries more economic value is likely to be the most preferred. When individuals with long-term career aspirations make linguistic choices, they choose the language which in their assessment has more significant influence in the formal economy. Since the informal economy is separate from the formal economy, policy regulations do not have much influence on the former’s activities (Chen, Citation2012; Miller, Citation1995). In other words, as the responses from the students suggest, individuals make linguistic choices that give them access to the formal economy.

Although African languages are currently mainstreamed in the academic discourse, they are nevertheless excluded from the operational activities of the valuable economy (L. Wright, Citation2002). In this regard, one can say that the UKZN language policy currently concentrates on the need to achieve the social transformation necessary for linguistic equality of African languages alongside English but fails to consider the political and economic realities of African languages for communication in governance, trade, commerce, and industry. In the workplace, individuals have little power to determine the language of business and communication because the language of the market determines the language used in internal (work) communication (Breton & Mieszkowski, Citation1977).

Although it is possible that UKZN language policy is responsive to the interests and commitment of the people of South Africa in promoting their languages, we argue that this priority must be balanced with students’ access to skills and knowledge in English. Excellent English language skills will ultimately benefit students because it is the language that is used in business, government, and education within and outside South Africa. Language connects with both social and economic power; it is crucial that the languages used to educate students in academic institutions match the language skills required in the job market (Trudell, Citation2007). As Vaillancourt (Citation2002) argues, the interaction between the entrepreneur’s language preference and constraints such as employees’ lack of proficiency in that language makes one language or a combination of languages the profit-maximizing solution for a firm.

Trends show that, irrespective of the size of the economy vis-à-vis a country’s population, linguistic choices are made based on their utility (De Klerk & Bosch, Citation1993). In South Africa, most of the population’s outlook is restricted by their perception of modernity that is exemplified by the country’s financial system and concretized by photos portrayed in the media (Miller, Citation1995). Linguistic selections are primarily based on the individual’s professional aspirations as well as more significant issues like bilingualism. Economic factors influence language choices and preferences, because languages are used in business, production and education. Since English serves both social and economic interests in South Africa, it is important to empower black learners with this linguistic capital to enable them to take advantage of the higher education system and the world of work in a way that does not disqualify or devalue access to African languages. The emphasis should be on isiZulu-speaking learners being skilled in both English and isiZulu rather than isiZulu only as this may limit their access to opportunities in the labour market. As Bloom and Grenier (Citation1996) note, there is a relationship between language and employment because different professions require specific language skills.

The main issue that arises in the responses from the UKZN staff and students is the dilemma between the social tranformative value and economic realities of implementing the UKZN language policy. Although the policy satisfies the social transformation objectives of South African higher education, it neglects the economic aspects that will make its implementation successful. This calls for institutional structures to be put in place and for external support to address the economic factors that inhibit the professional and career development of graduate students who study in isiZulu. isiZulu could become more influential if its use in the economy is deliberately brought to the same standard as English.

6. Conclusion

This article examined the issues relating to the social context of the language policy’s implementation at UKZN. We examined language and its social use to determine its complex relationship with culture, which renders language the marker of people’s identity. The analysis showed that language policies can include and exclude people belonging to different social groups. The UKZN language policy favours isiZulu-speaking students over other ethnic groups, as it does not integrate other ethnicities. This is having an impact on UKZN stakeholders’ social relations. We drew on social constructivism to argue that language has an economic aspect which is measurable by the extent of its influence on the formal economy. Therefore, languages are not treated equally as they carry different economic value. This underscores the dissimilar treatment isiZulu (and other African languages) receive compared to European languages. As language planning is a multi-dimensional affair, the influence of economic factors must be complemented by social dimensions.

Recommendations arising from this study could assist the university as it embarks on the implementation of the second phase of its bilingual language policy (2019–2029). In order to address the main challenge of persuading UKZN students to use a dual medium of learning in a predominantly English-speaking environment, the university should focus on changing the current pessimistic attitudes of staff and students towards the use of isiZulu before the technical aspects of the policy are implemented. Such measures may include embarking on campaigns to educate and motivate students on the social need for isiZulu. The goal of language planning should be to motivate people to want to use a language, and thus advance multilingualism. It is also vital for all stakeholders to offer incentives for isiZulu proficiency in all spheres, from the provincial parliament to the provincial public service. These would have to at least match if not exceed the current gains accruing from proficiency in English. Employers in business enterprises, the public authorities, and nongovernmental agencies need to stress the significance of African language fluency in an increasingly interactive world, both within the country and abroad.

Students should also be encouraged to pursue careers in isiZulu journalism, translation, research, the performing arts, leisure and script writing for radio, and television. The media’s capacity to demonstrate the social value of isiZulu literacy cannot be overemphasized. The public needs to understand the advantages of literacy in isiZulu nationally and internationally. African language speakers who excel in foreign countries should be given widespread media coverage and competitions should be held to produce books, articles, poems, and essays in isiZulu. It is also important to monitor and evaluate the institution’s progress in implementing the bilingual language policy. This will help to determine milestones reached and to set processes in motion for improved implementation. We also recommend that similar studies be conducted using different universities as case studies to track the status quo regarding language practices amongst higher education institutions in South Africa.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zama Mabel Mthombeni

Ms Zama Mthombeni is a researcher in the Inclusive Economic and Development unit at the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). She is pursuing her PhD in Development Studies through the University of KwaZulu Natal Her research focus is primarily in the social sciences [public policy and social development]. We conduct research that contributes to social transformation, human development and an inclusive economic growth path through an educated, skilled and informed citizenry. Currently I am involved on a project “transformation of higher education in South Africa” is a project run by Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) in response to a request by Ministerial Oversight Committee on Transformation in the South African Public Universities (TOC) to investigate progress with higher education (HE) transformation in keeping with its mandate.

Notes

1. These works point to the effects of apartheid and Bantu Education in South Africa. Whilst Mkhize and Hlongwa (2014) and Diab, Matthews and Gokool (2016) focused on the positive effects on the inclusion of African languages in higher education institutions in South Africa, Wade (2005) focused more on the challenges of the inclusion of African languages. Webb (2002) discussed the social history of South Africa and its impact on language setting and prevailing language policies.

2. This is sometimes referred to as the home language, meaning the language that the student knows best and is comfortable reading, writing and speaking. For this reason, the home language taught to pupils at school is often (but not always) the same as the language they speak at home.

3. The dominance of Afrikaans has declined since the demise of apartheid and its use in education has been significantly reduced as a result of the 2015/2016 #Fees Must Fall Campaign.

4. It should, however, be noted that Mathews (2012) reported that the UKZN language policy had a positive social impact especially for medical students who require competency in isiZulu.

References

- Alexander, N. (2013). Thoughts on the South Africa. Johannesburg: Jacana Media. Balfour,F.2004. ‘Chinese reform picks up speed’, Business Week March 8, 46.

- Bloom, D. E., & Grenier, G. (1996). ‘Language employment and earnings in the United States:Spanish-English differentials from 1970 to 1990ʹ, International Journal of the Sociology of Language 121, 43–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.1996.121.45

- Breton, A., & Mieszkowski, P. (1977). The economics of bilingualism.” In W. Oates (Eds.) the political economy of fiscal federalism, 261–273. Lexington.

- Cele, N. (2001). ‘Oppressing the oppressed through languages liberation: Repositioning english for meaningful education’, Perspectives in Education, 19 (1), 181–193.

- Chen, M., . K. (2012). ‘The effect of language on economic behaviour: evidence from savings rates, health behaviours and retirement assets’, cowles foundation discussion paper no. 1820, cowles foundation for research in economics yale university. constitution of the republic of South Africa, 1996. Accessed online https://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/constitution/SAConstitution-web-eng.pdf

- Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language. Cambridge University Press.

- De Klerk, V., & Bosch, B. (1993). ‘English in South Africa: The eastern cape perspective ’English World-Wide. 14(2),209–229. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/eww.14.2.03dek

- Department of Higher Education and Training. (2015). Report on the use of African languages as mediums of instruction in higher education. Accessed online on www.dhet.gov.za

- Department of statistics South Africa. (2018). Mid-year population estimates. Accessed online http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=11341

- Dolby, N. E. (2001). Constructing race: Youth, identity, and popular culture in South Africa. Suny Press

- Fan, W. (2011). Social influences, school motivation and gender differences: An application of the expectancy-value theory. Educational Psychology Review 31, 157–175. 2 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2010.536525

- Gernsbacher, M. A., (2017). Editorial perspective: The use of person‐first language in scholarlywriting may accentuate stigma. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(7), 859–861. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12706

- Grin, F. (2006). Economic considerations in language policy. In T. Ricento (Eds.). An introduction in language policy (p. 20). Blackwell.

- Kamwangamalu, N. M. (1997). ‘Multilingualism and education policy in post-apartheid South Africa’, Language Problems and Language Planning, 21(3),234–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.21.3.03kam

- Kamwangamalu, N. M. (2016). Language Policy and Economics. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kapp, R., & Bangeni, B., 2011. A longitudinal study of students’ negotiation of language,literacy and identity, SALALS, 29, (2),197–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2989/16073/614.2011.633366

- Kedreogo, G. (1997). Linguistic diversity and language policy: The challenges of multilingualism Burkina Faso. Intergovernmental Conference on Language Politics in Africa, Harare.

- Kormos, J., & Kiddle, T. (2013). The role of socio-economic factors in motivation to learn english as a foreign language: The case of chile. System 41, 399–412. 2 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.03.006

- Lombard, E. (2017). ‘Students’ attitudes and preferences toward language of learning and teaching at the university of South Africa’. Language Matters 48 (3),25–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10228195.2017.1398271

- Mauranen, A., (2018). Second language acquisition, world englishes, and english as a lingua franca (ELF). World Englishes, 37(1),106–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12306

- Miller, D. (1995). ‘Anthropology, modernity and consumption’, In Worlds Apart: Modernity through the prism of the local (pp. 180-200). Routledge.

- Mufwene, S. S. (2015), Colonization, indigenization, and the differential evolution of english: Some ecological perspectives. World Englishes, 34(1): 6–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12129

- Murray, S. (2002). Language issues in South African education:on overview. In R. Mesthrie(Eds.), Language in South Africa Cambridge University Press,434–448

- Naidoo, S., Gokool, R., & Ndebele, H. (2017). The case of isiZulu for non-mother tongue speakers at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa – Is the compulsory language module promoting social cohesion? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38, 1–13.121 . https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2017.1393079

- Ndebele, H., & Zulu, N. S. 2017. ‘The management of isiZulu as a language of teaching and learning at the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s college of humanities’. Language and Education. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2017.1326503. Accessed on 4 June 2017. 31 6 509–525

- Nettle, D., & Romaine, S. (2000). Vanishing voices: The extinction of the world’s languages . Oxford University Press

- Nudelman, ca. (2015). Language in South Africa’s higher education transformation: A study of language policies at four universities. Master’s thesis.

- Pillay, V. and Ke, Y. (2015). Multilingualism at South African universities a quiet storm. South African linguistics and applied language studies, 33(4), 439–452

- Poggensee, A. (2016). Perspectives from Senegal and the United States. Honors Theses. Western Michigan University.

- Ramsay-Brijball, M. (2003). A sociolinguistic investigation of code-switching patterns among Zulu L1 speakers at the university of durban –westville. Doctoral dissertation

- Rudwick, S., & Parmegiani, A. (2013). Divided loyalties: Zulu vis-à-vis english at theUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, Language Matters, 44 (3), 89–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10228195.2013.840012

- Subtirelu, N. (2013). ‘What (do) learners want (?): A re-examination of the issue of learner preferences regarding the use of ‘native’ speaker norms in english language teaching’, Language Awareness, 22(3),229–270 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2012.713967

- Swaffer, K. (2014). ‘Dementia, stigma, language, and dementia-friendly’, Dementia, 13(6),709–716. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214548143

- Teeger, C. A. (2015). Both side of the story: History education in post-apartheid South Africa. American Sociological Review, 80 (6), 1175–1200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122415613078

- Thorne, S. (2000). Data analysis in qualitative research. Evidence based nursing, 3(3), 68–70

- Trudell, B. (2007). ‘Local community perspectives and language in Sub-Saharan African communities’, International Journal of Educational Development, 27, 552–563. 5 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2007.02.002

- Tsui, A. B., (2017). Language policy and the social construction of identity: The case of HongKong. In Language policy, culture, and identity in Asian contexts, 131–152. Routledge

- Tupas, R. (2015). ‘Inequalities of multilingualism: Challenges to mother tongue-based multilingual education’, Language and Education, 29(2),112–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2014.977295

- University of KwaZulu-Natal. (2014). Language policy of the university of kwazulu-natal.language board.

- University of KwaZulu-Natal. (2016). College of Humanities Brochure. University of Kwa-Zulu-Natal.

- University of KwaZulu-Natal Institutional Intelligence. (2017). Institutional IntelligenceReports, durban: University of kwazulu-natal. www.ukzn.ac.za accessed on 25 March 2017.

- Vaillancourt, F. (2002). The economics of language and language planning. In D. M. Lamberton (ed.), The economics of language. Edward Elgar.

- Wright, L. (2002). Why english dominates the central economy: An economic perspective on elite closure and South African language policy. Language Problems and Language Planning 26(2), 117–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.26.2.04wri

- Wright, S. (2016). Language policy and language planning: From nationalism to globalization. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zungu, P. J. (1998). The status of Zulu in KwaZulu-Natal. In G. Extra & J. Maartens (Eds..) Multilingualism in the multicultural context: case studies on SA and western Europe (p. 12). Tilburg University Press.