Abstract

The purpose of this qualitative study was to understand how feedback loops function within the Ministry of Education (MoE) Provincial Education Directorate (PED) in Herat province of Afghanistan, how the MoE/PED collects, analyzes, and uses feedback for improving its policies and programs, and responds to the issues and barriers identified at the school levels. To narrow down the research, it investigated the feedback loops around teacher professional development (TPD). We used semi-structured interviews and document analysis to collect data. The participants were 34 individuals selected purposefully from six schools, one CBE, and Herat educational offices. We used thematic analysis methods for analyzing the data. The findings indicate that the MoE/PED did not collect regular or quality feedback about TPD activities, usually offered as teacher training workshops, from this study participants. Besides, we did not find any evidence that the MoE/PED has used the rarely collected feedback for improving TPD programs, so the feedback loops were not closed. The mechanisms for collecting, analyzing, and using feedback are not well defined and established at the MoE/PED. The existing structures for communicating information between schools and the higher authorities in the MoE/PED are manual and paper-based, and the process is very time-consuming.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Any organization needs to collect, analyze, and use feedback from its clients or beneficiaries to learn continuously and ensure its relevance and effectiveness. This study argues that the Provincial Education Department (PED) in Herat, Afghanistan, does not collect regular or quality feedback about teachers’ professional development activities from teachers and school administrators. They have no voice on the types, frequency, length, and contents of teacher training programs. The study also found that the PED does not have the authority to decide on most TPD activities and merely sends the rare collect feedback data to the central Ministry of Education (MoE). The existing structures for communicating information between schools and the higher authorities in the MoE/PED are manual and paper-based, and the process is very time-consuming. This research highlights the lack of evidence-based decision-making in the Afghan education system and the need to establish clear and effective feedback loop mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Several assessments show that the quality of education in early grades in Afghanistan is poor (USAID, Citation2016 &, Citation2017; Afghan Children Read, Citation2017; Molina et al., Citation2018), and 3.7 million children aged 7–17 are out of school, of which 60% are female (UNICEF, Citation2018). Many Afghan school teachers are not adequately educated and trained, and only 52% of teachers meet minimum qualification requirements, 14th-grade degree (Ministry of Education, Citation2018).

The MoE and its partners have implemented several in-service (INSET) programs since 2001, often through the World Bank-funded EQUIP program. INSET programs were on pedagogical skills, content knowledge, and administrative skills (Ministry of Education, Citation2006, Citation2013a, 2013b, Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2016).Footnote1 However, there is no data available on the number of teachers who attended each program. Ministry of Education (Citation2018) indicates that teachers complained that there was no plan for training teachers; the participants were not selected based on a needs assessment. Some teachers attended training workshops several times, while others did not have an opportunity to participate in a teacher training program; the training workshops were held during school hours, and the trainers were not competent and could not train them properly.

All the teacher professional development (TPD) policies and programs are decided at the central MoE in Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital. The sub-national departments, including those in Herat Province, are only responsible for implementing the TPD policies and programs designed in Kabul. They have no allocated budget for designing and implementing their own TPD programs. However, if Provincial Education Directorates (PEDs), District Education Departments (DEDs), or provincial Teacher Training Colleges (TTCs) have particular needs concerning TPD programs, they are expected to request through sending official letters to the MoE.

Additionally, the TPD programs in Herat are mostly offered in three formats: (1) in-service teacher education programs offered at the TTC in Herat City for teachers who do not have the minimum required qualification (grade 14th). The program is for two years, and the graduates will receive grade 14th degree. (2) academic supervision at schools: Academic Supervision Members (ASMs) at the DED levels in Herat Province are responsible for visiting schools and providing feedback and guidance to teachers at least three times per academic year. (3) short-term training programs: In addition to the INSET programs that were implemented in all provinces, including Herat, some national and international NGOs (e.g., BRAC, British Council) have offered short-term TPD programs. The content of these offered TPD programs included 21st century core skills for teachers (British Council Connecting Classrooms Project), peacebuilding (Social and Development Hope for Peace Organization), teaching methods (BRAC), and COVID-19 control and prevention (UNICEF). However, there is no data available on how many teachers have attended each training program.

Afghan Children Read (ACR), a project funded by USAID from 2016 to 2021, initiated this research to explore how feedback loops function within the MoE PED around teacher professional development in Herat Province. The purpose of the ACR was to develop the capacity of the MoE to provide an evidence-based reading program for students in grades 1 to 3. The project aimed to improve the MoE management capacity by strengthening feedback loop mechanisms at different levels to enable the MoE to continuously improve its policies and practices by collecting and using feedback from schools and classrooms (Afghan Children Read, Citation2017).

There is a vast literature around feedback loops, organizational learning, evidence-based decision-making, participatory monitoring and evaluation, complex adaptive systems that has informed this research (e.g., Argyris, Citation2004; Argyris & Schön, Citation1978; Patton, Citation2011; Senge, Citation1990; Whittle, Citation2015). The literature emphasizes the importance of soliciting feedback, analyzing, and using them to improve the organization’s effectiveness. The terminology used to describe feedback loops varied, and few documents and articles explicitly referred to feedback loops or feedback mechanisms.

1.1. The concept of feedback loop

Feedback is perceptual information, such as thoughts, feelings, and perceptions from the beneficiaries about the program, service, or product they have received (Feedback Labs, Citation2017; Jacobs, Citation2010). Thus, the beneficiaries’ views about program effectiveness are feedback data, but the number of teachers who attended the program is not feedback. However, Whittle and Campbell (Citation2019) used a broader definition that encompasses any information about what we do or how we do it. They categorized feedback data into subjective and objective. Subjective feedback data are beneficiaries’ perceptions, while objective feedback data are other data about the result of a program, service, or product collected objectively, such as by observation. We used the narrower definition of feedback in this study.

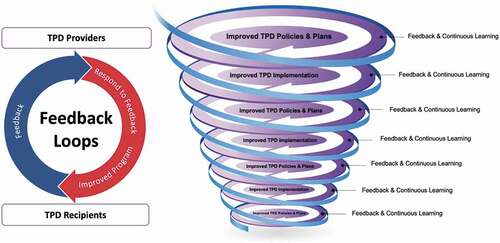

The feedback loop is the cycle of soliciting feedback and acting based on the feedback to improve what we do (Goetz, Citation2011). They are also called learning loops (USAID, Citation2013) as they facilitate continuous learning. When the collected feedback leads to actions, the feedback loop is closed (Bonino et al., Citation2014). According to Feedback Labs (Citation2017), feedback loops require a two-way stream of communication between someone(s) who designs or delivers a program or service and the beneficiaries of the program or service (para. 1). Feedback loops are two-way processes that require inputs from both sides: program/service receivers, i.e., beneficiaries, on one side and the program/service providers on the other side. The beneficiaries provide feedback, and the program/service providers will adapt their decisions and practices and report back to the beneficiaries.

Various models describe the steps in the feedback loop process. For example, Whittle (Citation2015) proposed four steps that include: (1) collecting data, (2) analyzing the data, (3) presenting and discussing the feedback with the stakeholders, (4) adapting and making changes based on the feedback (see ).

Figure 1. Closed feedback loops .Whittle (Citation2015)

The first step is data collection. Bonino et al. (Citation2014) found that organizations gather feedback through so many methods, including personal interviews, focus groups, face-to-face meetings, complaint boxes, telephone hotlines, phone messages, emails, and websites, to name a few. Feedback Labs (Citation2017) suggests that the collection process should be simple; feedback should be collected at the right times using appropriate tools or technologies and be limited to what is needed. It is also important to make sure that the process is inclusive, and the data are collected from all groups of beneficiaries, including marginalized groups and women.

The feedback data should be analyzed properly, so you can see your program or service from stakeholders’ eyes, especially beneficiaries, and identify areas of improvement. The next step is to present and discuss your understanding of the collected feedback with the beneficiaries and other stakeholders and decide how to collectively improve the program or service. As the final step, you need to make the necessary adaptation and implement the discussed ideas (Feedback Labs, Citation2017). It is important to report back to the feedback providers to inform them how their feedback was used, which can “lead to stronger buy-in, and in turn, higher quality data, more robust analysis, and improved adaptation” (USAID, Citation2018, p. 7). If they do not hear how their feedback was used, they may be less likely to provide feedback next time.

Feedback Labs (Citation2017) added “design” as the first step to the feedback loops cycle. They stated that feedback loops must be designed properly in close consultation with the stakeholders, especially the program or service beneficiaries. Since we explore the existing feedback loops, we did not consider this step in our study. However, we believe that the beneficiaries’ views on their needs and expectations should be collected before designing the program, and their perceived needs should be considered.

Digital technology, such as cellphone, tablets, computers, the internet, etc., has a huge potential to strengthen feedback loop mechanisms and is used especially in collecting and sharing feedback data (Whittle & Campbell, Citation2019). Digital technology enables feedback loops to collect, share, and analyze feedback data quickly to adapt the program. It helps identify and address issues in the field in real-time or close to real-time. For example, USAID’s mission to use digital technology in Zimbabwe reduced field reporting time from one month to one day (Whittle & Campbell, Citation2019, p. 8). In addition to increasing the speed, digital technology helps feedback loops reach more people at a reasonable cost. Still, the process should not exclude those who do not have access to technology. The use of digital technology can help collect feedback data from more beneficiaries, easily communicate the data with relevant parties, analyze and use the data for improving the program or service and report it back to the beneficiaries. It will also significantly reduce the cost of feedback loops.

In business, the amount of customers’ purchase is straightforward feedback (Feedback Labs, Citation2017). Customers can easily express their opinions by using their purchasing power; if the business managers collect and analyze data about its sale and adapt its performance accordingly, some feedback loops are working. However, collecting feedback in the non-business world (e.g., educational settings, non-profit organizations) is more complicated. There is no automatic or straightforward mechanism in non-business sectors for people who use a service or benefit from a program to express their opinions about it (Feedback Labs, Citation2017).

Bonino et al. (Citation2014) differentiate between formal and informal feedback loops. Informal feedback loops are embedded in how people act or work on a day-to-day basis. Formal feedback loops are when specific mechanisms, structures, or procedures are dedicated to this function (p. 9). Informal feedback loops are enough if the expected feedback data are collected and channeled through other existing processes, such as normal two-way communications or monitoring processes. If not, establishing formal feedback loop mechanisms is recommended. This research explored both formal and informal types of feedback loops.

1.2. Importance of feedback loops

Feedback loops help ensure the beneficiaries’ voices are truly listened to and used for improving the program. Not all matters are decided by the policymakers, funders, or experts for them. It will shift power dynamics from elites (donors, policymakers, and experts) to the people they serve and help make the powerholders more accountable to the beneficiaries (Sthanumurthy, Citation2017).

Feedback Labs (Citation2017) states that it is an ethical imperative to treat beneficiaries and other marginalized stakeholders as equal partners and listen to them and consider their voices in the design, evaluation, and improvement of programs. It argues that integrating their feedback will also improve program outcomes, especially in politics, education, and health. Feedback Labs (Citation2017) claims that listening to beneficiaries’ feedback is both the right and smart thing to do.

Many international development organizations, including USAID, have made commitments to improve their assistance’s quality and effectiveness by listening to their aid recipients (Bonino et al., Citation2014). USAID (Citation2018) program cycle operational policy guided USAID development missions to “seek out and respond to, the priorities and perspectives of local stakeholders, including partner country governments, beneficiaries, civil society (including faith-based organizations), the private sector, multilateral organizations, regional institutions, and academia” (p. 13). The policy document emphasized the inclusion of poor and marginalized populations, including women and girls, in this process.

1.3. Feedback loops and organizational learning

Feedback loops are at the core of organizational learning, defined as the learning process within an organization that supports its goals (Popova-Nowak & Cseh, Citation2015). Organizational learning occurs when individuals within the organization encounter a problematic issue and attempt to study the problem on behalf of the organization (Argyris & Schon, Citation1996). Feedback loops help organizations learn new processes and methods about their practices (Whitmore, Citation2013). Feedback loops help organizations to learn through a participatory approach, considering the beneficiaries’ views and perspectives.

A culture of learning and evidence-based decision-making in an organization helps feedback loops function effectively, so the staff is encouraged to learn and use what they have learned to improve the organization’s decisions and practices (Derrick-Mills, Citation2015). Feedback loops support the adaptive management approach promoted by USAID, which is defined as “an intentional approach to making decisions and adjustments in response to new information and changes in context” (USAID, Citation2020, p. 140). Adaptive management that involves evidence-based decision-making and flexible operations will lead to more effective and substantial programs.

1.4. Feedback loops and monitoring and evaluation

Jacobs (Citation2010) claimed that the feedback loop mechanism is a type of participatory monitoring and evaluation (M&E), in which the focus is on the beneficiaries’ or customers’ feedback as the main M&E data. However, unlike M&E, an important advantage of feedback loops, especially digital ones, is “the ability to identify and respond to issues in real-time, rather than wait[ing] for monthly, quarterly or even end-point monitoring reports” (INTRAC, Citation2016, p. 6). Feedback loops can complement M&E because they work as a mechanism for communicating and reporting information obtained from M&E (Heirman et al., Citationn.d.).

1.5. Feedback loops and complexity theory

Feedback loops are particularly crucial in situations with a high level of complexity and uncertainty, where “processes and outcomes are unpredictable, uncontrollable, and unknowable in advance” (Patton, Citation2010, p. 8). Feedback loops enable decision-makers to navigate complex and uncertain situations and find solutions that are “best fit” rather than “best practice” (Ramalingam et al., Citation2017).

Complexity theory asserts that complex systems both in natural and social domains “have to learn, adapt and change” to survive (Morrison, Citation2008, p. 19). Complex systems, including living organisms, must be adaptive to survive. Complex adaptive systems are self-governed by system-generated feedback loops (Halverson, Citation2010; Pocklington & Wallace, Citation2002). They adapt their actions continuously based on the feedback they receive from their environment. In the same vein, complexity theory suggests that a social complex system must collect ongoing feedback from its environment and adapts its actions accordingly. Morrison (Citation2008) argued that because schools operate in complex, unpredictable, and changing environments, they should continuously learn, adapt, and change.

In a complex system, there are circles of actions that affect one another. These natural cycles of causal influence are also referred to as feedback loops in the literature. According to Sterman (Citation2000), all complex system dynamics occur because of two types of feedback loop interactions, namely positive and negative loops. Positive feedback loops reinforce activities happening in the system. These are processes that produce their growth, and the loop is self-reinforcing. For example, if a company lowers its products’ price to increase its sale, its competitors might do the same, forcing the company to lower the price even more.

On the other hand, negative feedback loops are self-correcting, and they counteract the change. They tend to push the system towards balance and equilibrium, resist change and keep the status quo. For example, reducing nicotine in a cigarette causes smokers to consume more to get the dose they need. These self-perpetuating, natural, informal feedback loops can create virtuous or vicious cycles, either make a change to take off or make it obsolete and create a strong resistance (Kleinfeld, Citation2015). Therefore, it is important to monitor such loops to understand how a system reacts to a change.

Patton’s (Citation2011) developmental evaluation model acknowledges complexity and uncertainty in social programs and emphasizes rapid feedback loops to support continuous learning and ongoing adaption to changing environments. He asserts that “continuous development occurs in response to dynamic conditions and attention to rapid feedback about what’s working and what’s not working” (p. 36). In developmental evaluation, the evaluators work collaboratively with the program designers and implementers to design and test innovations and new approaches as a long-term process of ongoing adaptation and development.

1.6. Feedback loops and TPD

Teacher professional development programs need to collect, analyze, and use teachers’ feedback to improve the programs and respond to their needs. Feedback loops can provide data for policymakers, funders, and training designers and implementers to improve TPD programs’ design and implementation (Buczynski & Hansen, Citation2010).

According to Tooley and Connally (Citation2016), there is a critical need for changing education systems into learning systems for students and teachers, and educational authorities. They posited that creating a TPD learning system rather than focusing on specific TPD activities, which are not sustainable, causes consistency and continuity in the TPD programs.

To discover the characteristics of effective TPD programs, Darling-Hammond et al. (Citation2017) reviewed 35 studies that yielded a positive relationship between TPD programs, teaching practices, and student achievement. Some of the characteristics are to conduct needs assessment regularly, increase opportunities for peer coaching and observations across classrooms, identify and develop expert teachers as mentors and coaches to support learning in their area(s) of expertise for other educators, and promote the use of student data to inform instruction. These recommendations are consistent with the feedback loops approach because they emphasize adapting programs based on the collected feedback.

1.7. Research on feedback in Afghanistan

There is little published research on feedback loops mechanism in Afghanistan. Afghan Children Read (Citation2017) explored the chain of communications among the education program stakeholders in Herat and Kabul. Their results yielded that the existing education communication channel is mostly linear—“from CBE [community-based education] to school, from school to DED [district education directorates], from DED to PED [provincial education directorates], and from PED to central MoE, and vice versa” (p. 5). Their results also demonstrated that face-to-face meetings, official letters, phone calls, and communication through school management system (SMS) members were the primary methods of communicating feedback between schools or CBE classes and DEDs, and between DEDs and PEDs at the province and the central MoE levels. The study concluded that sending official letters between the stakeholders was the main channel, which was time-consuming and inefficient. However, the study was focused on communication flow and did not adequately explore the cycle of collecting, analyzing, and using feedback.

Of those few published studies, Ruppert and Sagmeister (Citation2016) investigated people’s attitudes and perceptions towards receiving aid from foreign agencies in Afghanistan. The study showed that the process of feedback collection was not inclusive of community populations and was mostly collected from the influential community members; the feedback loops were not closed because they did not hear back from agencies on how they used their feedback; the community members did not feel comfortable to share and discuss sensitive matters, and the process was not continuous, and the participants were asked for feedback only at certain stages of projects.

1.8. The present study

The purpose of this qualitative study was to understand how feedback mechanisms function within the PED in Herat Province, how the PED collects, analyzes, and uses feedback for improving its policies and programs, and responds to the issues and barriers identified at the school and classroom levels. This study focused on feedback loops between teachers (as the beneficiary) and TPD providers (see ). We also explored the roles the local educational structures (PED & DED levels) play in the feedback loops.

The main research question and sub-questions were:

How do the feedback loops within the education system around teacher professional development function?

Does the PED collect, analyze, and use feedback on TPD policies and programs from teachers and school administrators? If yes, how?

What are the existing structures for communicating feedback around TPD? How effective are they perceived? What are the challenges of the existing feedback mechanism?

The research findings can help the MoE and its development partners to improve the relevant policies and mechanisms. Strengthening feedback loop mechanisms will facilitate evidence-based decision-making and continuous learning and adaptation at the MoE, which will result in improved educational processes and outcomes.

2. Research methods

Considering the nature of the research questions and our study’s purpose, we used a qualitative methodology to explore how feedback mechanisms regarding TPD function within the PED. This approach allowed us to obtain an in-depth understanding of the feedback loops and their challenges.

2.1. Setting and participants

This study was done in Herat Province of Afghanistan, a province with a 42.2 percent adult literacy rate in Herat (UNFPA Afghanistan, Citation2017). According to 2018 MoE Education Management Information System, there are 1179 schools in Herat Province. We used purposeful sampling to select the participants and used the maximum variation sampling technique to maximize variation in the sample size, ensuring to collect robust data from different kinds of participants. The study was conducted in three urban and three rural schools, one CBE as well as Herat DED, PED, and TTC. Both urban and rural schools included three different school types (i.e., female, male, and mixed) to maximize variation. We interviewed two teachers, the principal, and one member of the school management shura from each school. The participants in this study were 34 individuals, including nine women.

We selected the participants purposefully too. The principals had to have at least two years of experience as the sample school principal. The teachers had to be permanent teachers, expect in CBEs, and have at least two years of teaching experience. The SMS members must have at least two years of experience as an SMS member. We also selected a few individuals from the PED, DED, and TTC who were somehow involved in the feedback mechanisms around TPD. The field researchers made necessary efforts to interview both genders if they were available and willing to participate in this study because their experiences were assumed to be different.

2.2. Data collection methods and procedures

We used semi-structured interviews to explore the stakeholders’ attitudes and experiences toward the feedback loops mechanism regarding teacher professional development. We narrowed the scope of the research to the past two years to obtain clear and specific data.

The participants at school levels were selected voluntarily. However, most of the participants at PED and DED levels were pre-determined since they had key positions in the Education Department that could help us collect relevant and rich data about our research topic. Each interview session lasted between 25 to 60 minutes. We conducted one in-person interview with each participant, and in some cases, we had a few short telephonic interviews with some of our participants to collect additional data.

We also collected and analyzed relevant documents to collect detailed information on the feedback exchanged about TPD programs within and beyond schools. The documents include teachers’ meeting minutes, principals’ diagnosis books, SMS’s meeting minutes, and bylaws from MoE regarding the educational stakeholders’ responsibilities. Three meeting minutes were collected from each meeting minutes book to review the content and assess TPD programs’ information. This allowed us to verify the interviews’ findings, checking the existing document to track the reported issue’s change or development.

2.3. Data analysis

After collecting the in-depth interview data, we transcribed the interviews verbatim in Dari. Afterward, we imported the transcripts into MAXQDA for the data analysis. We read each transcript several times and coded the data using a thematic analysis approach. We refined our codes and generated categories and themes based on our research questions.

To ensure the research’s trustworthiness, we used triangulation and consensus techniques. Data were collected through two different methods (i.e., individual interviews and document reviews) from different participants’ sources to triangulate both methods and sources. Besides, a few researchers were involved in the data analysis and interpretations. Instead of competing over each other’s data interpretations, the researchers served as peer debriefers for the study, attempted to contemplate each other’s interpretations, discuss their rationale for such interpretations, and reach a consensus about more reasonable, convincing, and informative interpretations.

3. Results

The findings demonstrated the following two major categories (1) feedback processes on TPD policies and programs, (2) feedback communication structures concerning TPD programs.

3.1. Feedback processes on TPD Programs

3.1.1. No needs assessment prior to TPD Programs

All participants reported that they were not consulted, or data on their professional needs were not collected before the training design or implementation. “When planning training for teachers, teachers’ voices are not collected and are considered at all. Everything is decided from Kabul” (Teacher 3, Urban School B). Likewise, Teacher 9, Rural School C claimed that no one from DED or PED levels communicated with teachers regarding the training types they needed. He stated: “authorities do not do needs assessment. Many teachers need to participate in subject-based training, but very few training workshops are held based on their need.” Teacher 1, Urban School A said that once a training workshop is planned, the school receives an official letter to nominate teachers. She noted, “the training goals are sometimes not clear for us. After participating in the training, we realize that, for example, the program was on teaching methods or another concept.” Likewise, Teacher 6, Urban School C stated that in some cases, the delivered training programs were not based on the teachers’ needs, or the training contents were repeated for the teachers. He reported: “There was a mathematics training for us, but the participants already knew those topics. Trainings should address issues that are based on our needs.”

The findings also showed that the procedures for selecting schoolteachers for participating in TPD programs were not based on teachers’ needs, and it involved drawing lots and nepotism. For example, Teacher 2, Urban School A asserted, “when there is a need to select three or four teachers for a training, the principal draws lots to select and introduce teachers to participate in the training programs.” The participants expressed dissatisfaction with the drawing lots to choose teachers for TPD programs because it is neither based on teachers’ needs nor leads to equal access to TPD opportunities. We found that the training authorities did not check the participants’ backgrounds either.

A few of the teacher participants claimed that the official letters sent to schools usually do not clearly state the training goals and participation requirements. As a result, the right teachers are not introduced to training programs. In a nutshell, many teacher participants noted that teachers are occasionally introduced to training programs regardless of the relevance between the training goals and the teachers’ background, qualifications, and needs. The TPD program decisions are not made based on feedback collected from teachers.

3.1.2. No proper evaluation of teacher training programs

The participants stated no evaluation of the delivered TPD programs to assess the programs’ effectiveness and collect their feedback, except the evaluation forms at the end of the training programs. A few of the participants had participated in a teacher training program organized by BRAC, the INSET-6 training program held by the MoE in 2016, and training programs on Critical Thinking and Problem-solving held by the British Council in 2019. The participants of the programs had an opportunity to share their feedback by completing the course evaluation forms. They had opportunities to share their feedback, but they did not know how the evaluation data were analyzed or used for improving the training programs. We found that the distributed assessment forms were collected by the trainers and sent to Kabul to the TPD providers, and even the trainers were not informed whether the collected feedback was used or is going to be used for future TPD programs. However, the participants reported that the TPD trainers did not visit schools once the training was completed to evaluate the delivered programs’ effectiveness. For example, Teacher 7, Rural School A stated that “No one comes to supervise whether the training was effective for students and teachers or not. No one is supervising whether a teacher learned or not, or what is his/her problems?”

We also found that Herat TTC instructors mostly deliver the TPD programs in Herat, but ASMs, school principals, and headmasters, in the absence of principals, are the people who usually observe teacher’s classrooms. Since these people did not participate in those training programs and were not involved in the design and the delivery of the training programs, they cannot provide effective evaluation or follow-up.

3.2. Feedback communication structures concerning TPD Programs

3.2.1. Teacher meetings as a mechanism to share information within the school

The findings showed that one structure for sharing information among teachers and principals is teacher meetings. We found that these meetings are not held regularly. Several teachers and principals stated that they do not have any specific timetable for their teacher meetings. Both the interview data and the document analysis of teacher meeting minutes showed that teacher meetings’ frequency and duration vary among schools. According to many teacher and principal participants, the teacher meetings are held during the break time, usually about 10 minutes, and they are not on issues related to teacher professional growth. They are mostly on administrative matters (e.g., attendance of teachers, lesson plans, etc.). For example, Teacher 8, Rural School A pointed out, “during exam time, we hold meetings, and we discuss issues related to exams and textbooks.” Many other teacher participants claimed that academic issues are not discussed in their teacher meetings. For example, Teacher 11, Rural School C noted, “we don’t discuss teaching methodology issues in our teaching meetings. However, we discuss the progress of the subject we teach.”

Schools should keep a record of the teacher meeting discussions by writing the minutes on teacher meeting books. During the data collection, we asked each school to share their teacher meeting minutes with us. A few principals denied doing so. We took a copy of the meeting minutes that were shared with us. Here is one example:

Excerpt 1:

Three groups of [exam] questions should be prepared. They should be sealed in a pocket and should be submitted to the office.

Teachers are required to grade papers in the office. No one is allowed to take out the papers; otherwise, they should be accountable.

3. Parents are responsible for providing papers for their children’s exams.

4. Results sheets should be prepared and submitted to the office right after the exams.

Our analysis of the teacher meeting books demonstrated the following issues as the major issues discussed in teacher meetings: Informing teachers on the exam dates, checking and signing teachers’ lesson plans, checking attendance sheets of teachers for different classes, reminding teachers of the procedures for grading papers and preparing the result sheets, and teacher and student absenteeism. Overall, the results showed that teacher meetings do not nurture teacher growth because they are not held regularly, and they are mostly about administrative issues, not academic topics.

3.2.2. Teacher peer feedback as a rarely used mechanism

Some teacher participants claimed that they engage in talks with their peers about their instructions, especially when they have questions about their subjects. For example, Principal 3, Urban School C stated that the feedback exchanged among teachers, which happens rarely, is mostly limited to the content, not the pedagogy. Moreover, the teacher participants reported that sometimes they seek each other’s advice and suggestions when facing problems regarding the subjects they teach. For instance, Teacher 7, Rural School A asserted that she refers to her colleagues whenever she faces her teaching problems. She meets her colleagues during the break and raises her concerns regarding the subjects she teaches. Likewise, Principal 4, Rural School A noted that novice teachers in their school tend to ask headmasters or senior teachers questions.

The participants reported that schools do not have any designated venues for teacher-to-teacher experience sharing. Many teacher participants stated that since there is no policy or mechanism to mandate teachers to regularly hold informal feedback sessions, the meetings happen only when they face a problem and issue. The findings also showed that high workload and lack of resources are the major barriers to exchanging feedback among teachers. For example, Teacher 5, Urban School C argued that he must teach 32 hours per week, and he cannot make the time to work on his professional development skills in general and exchange feedback with his colleagues. He is required to spend 36 hours at school; he teaches 32 hours, and the remaining time, he must check students’ homework and work on his lesson plans.

3.2.3. Principal classroom observation as a mechanism for providing feedback to teachers

According to the MoE Elementary School Bylaw, principals should evaluate teachers’ performance by conducting classroom observations and checking teachers’ lesson plans every two months (MoE, n.d., Article 33) because principals are the ones who deal with teachers daily. These observations, according to the participants, are followed by an exchange of feedback with teachers. Principals who conduct classroom observations must write their observations in a book called diagnosis book and share the reports with the ASMs. This book is a collection of blank papers stitched or bound together. This means that principals do not follow a specific observation form or checklist for their classroom observations. As a result, the observation reports of principals in different schools are different.

Based on our collected diagnosis book reports, although most principals have conducted at least one teacher observation per month, not all teachers received the chance to be observed by the principal for months. Since there is no transparent system to track how often principals observe teachers and which teachers they observe, the principals do not observe all teachers as it is noted in the principals’ job descriptions—observing each teacher once per two months. This indicates that when principals are not required to follow a specific mechanism for collecting and analyzing feedback on teachers’ performance, they might not do the evaluations regularly when needed.

Additionally, we found that principals used already limited instructional time for providing feedback. Teacher 6, Urban School C stated that their principal uses the instruction time to collect feedback on teachers’ performance. He claimed, “our principal asks the teacher to leave the classroom so that he collects information on teachers’ performance regarding their teaching.” However, Teacher 10, Rural School B noted, “two to three times per year, our principal sits like a student in classes and observes teachers.” Similarly, Teacher 12, Rural School C contended, “The principals’ workload is high, and because there are many teachers, the principal observes only one class once per two weeks.” As a result, some teachers have few opportunities to receive classroom observations by their principal even though they should evaluate each teacher’s performance once per two months.

Similarly, the CBE teacher participant mentioned the lack of regular or systematic supervision and observations by their hub school principal. He argued that his class is expected to be managed and monitored by a hub school through a cluster approach; however, this rarely happens. The principal of their hub school even asks this CBE teacher to help his colleagues, although the principal himself should visit the CBE classes and provide them with feedback. According to this teacher, the location of the CBEs might have been the reason they are marginalized.

One ASM participant claimed that some principals prepare fake reports about classroom observations at their schools. Another ASM noted that when academic supervision members visit schools, they check the principals’ diagnosis book to see if they have conducted teacher observations. To check the accuracy and transparency of the principal’s data, the ASMs ask teachers to see whether their principal has visited their courses. In some cases, the ASMs notice a mismatch between the principal’s diagnosis book’s information and the teachers’ performances. We also noticed this lack of transparency during the data collection. When we asked a principal to share her diagnosis book with us, since her diagnosis book was blank, she asked one of the headmasters to write some fake observation reports in the diagnosis book to share the reports with us.

3.2.4. Monthly meetings to exchange information between principals and DED Officials

Another communication channel for raising issues related to teachers and schools is principals’ participation in monthly meetings at the DED level. In these meetings, the head of DED, the head of ASD, and sometimes ASMs are present, and principals share different issues about their teachers and schools. According to Principal 5, Rural School B, their monthly meeting with DED officials usually takes around two hours. He stated:

Since, there are 154 schools in our DED, more than 120 or 130 principals participate in each monthly meeting, not all the principals are given a chance to share the issues they face at their schools. But a few minutes at the end of each meeting are allocated for those principals who want to discuss urgent issues.

Additionally, Principal 6, Rural School C asserted that their monthly meetings with DED officials are usually the same because they often discuss administrative issues. Moreover, according to this principal, the meetings’ agenda is mostly the same unless there is a new official letter from higher authorities that should be discussed during the meeting. He added that the major problems reported to the DED officials during the month are also discussed in these meetings to inform all principals about them. If there is an issue that needs to be shared with principals, the head of DED or the head of ASD discuss them during this meeting.

3.2.5. Academic supervision as a mechanism to provide feedback to teachers

According to the MoE Elementary Schools Bylaw, Article 395, ASMs are also required to conduct teacher observations. ASMs should visit schools three times per year to conduct teacher observations, check teachers’ lesson plans and attendance sheets, evaluate their teaching quality, and provide teachers with feedback. During the first two visits, ASMs mostly supervise and guide teachers, while during the third visit, issues related to administration and teaching are observed and evaluated at the school level.

In addition to checking teachers’ lesson plans and reports, ASMs must conduct teacher observations by completing a 25-criterion observation form (see Appendix B) and giving them feedback. They also check the administrative issues and documents (i.e., diagnosis book, teacher meeting book, attendance sheets, exam reports) at the school level. ASMs are required to write a report for each of their school visits in the school diagnosis book. If teachers who are observed and evaluated by the ASMs receive a score less than 60, they will be required to participate in training workshops organized by the “Pay and Grading, Evaluation, Tashkeel, and Capacity Building” Department.

The findings indicate that some ASMs give feedback to teachers in schools, while some ASMs just criticize and do not share suggestions or solutions, and when they collect information from schools, teachers or principals do not hear back on their shared issues. For example, Principal 2, Urban School B claimed that if ASMs realize that teachers, especially those who get a score above 60 from ASMs during their class observations, need to improve their subject knowledge, they neither hold training workshops for those teachers nor report nor follow the issue; they just tell teachers that they need to work on their capacity building to improve. Likewise, Principal 5, Rural School B claimed that once their chemistry teachers needed to improve their subject knowledge. Although the principal reported the issue to ASMs, he never heard back or received a response to this reported issue. As a result, some teachers and principals have lost faith in the current feedback system. Besides, Principal 4, Rural School A noted that she does not request the higher education authorities to address these needs because she is not optimistic that the authorities would respond to their needs.

There is one academic supervision department (ASD) in Herat City and 15 ASDs in Herat Province—one ASD per district. According to the General ASD head, the ASMs at each district level share their supervision reports with their ASD head. Each ASD head compiles the reports and prepares a monthly report and a work plan for the next month. All the 16 ASD heads are required to compile the reports they collect from their ASMs throughout the month, complete a monthly report form, and send the report and their work plans through official letters to the General ASD head. The ASD heads are also required to participate in monthly meetings at the PED level with the General ASD head. In this meeting, which is held on every 20th of the month, each ASD head shares a summary of his/her monthly report, which contains their achievements, challenges, and plans. If there is an issue that needs to be shared with ASMs and principals, the General ASD head discusses the issue with the ASD head. The General ASD head compiles and shares the reports with the head of PED. He also sends a quarterly report to the MoE. However, according to ASMs, rarely will they receive a response to the issues they raise to their ASD heads. For example, one ASM stated, “The reports and issues follow their administrative procedures to higher levels, but we usually don’t hear back for months. The issues and reports are mostly on paper; no one addresses them. The result of our raised issues is not shared with us; the result is lost.”

As the above figure’s communication structure depicts, the information ASMs collect about teachers’ performance from schools is expected to be shared with Kabul’s higher authorities. Different communication channels, such as face-to-face meetings, official letters, and phone calls, are used in these communication channels. However, the processes of collecting feedback in most cases are linear—they do not form cycles. In other words, once the reports are compiled and sent to the educational authorities, they do not loop back to address the needs of teachers in the first place. The majority of the teachers, principals, and ASM participants stated that they have no idea how the collected feedback from schools is used in decision making. One teacher participant claimed, “Teachers who have power contact educational authorities to get benefits from trainings or other opportunities.” Similarly, one principal mentioned that because the quality of the exchanged feedback is not questioned, many educational stakeholders involved in the communication structure are not accountable for collecting, analyzing, and responding to feedback. Therefore, the current structure for information flow among different departments working with teachers is unclear and ineffective.

The participants believed that ASMs classroom observations happen rarely and irregularly. Some participants argued that ASMs in rural areas rarely conduct classroom observations. Teacher 6, Urban School C stated, “There is an ASM that visits our schools approximately once per month. He cannot observe all classes—he only observes a few classes, and he spends the remaining time checking our administrative documents.” Similarly, Principal 4, Rural School A claimed that those rare school visitations by ASMs in their rural school are spent checking administrative issues (e.g., attendance, lesson plan) with no or poor feedback on teacher’s instruction.

According to the participants, shortage of ASMs, insecurity, and lack of transportation facilities prevent ASMs from visiting schools in some districts. These factors negatively impact the frequency and quality of the exchanged feedback regarding TPD between schools and ASMs. As a result, when feedback is not collected from teachers, no results-driven response will be reported back to schools.

3.2.6. Poor feedback on teachers’ performances

We found conflicting viewpoints among the participants about the effectiveness of the principals’ and ASMs’ classroom visits and teachers’ observations. Only a few teacher participants noted that the teacher observations helped them to improve their instructions. For example, Teacher 12, Rural School C stated that principals and ASMs provide teachers with feedback during one-on-one meetings after class observations. He argued that when there are classroom visits, teachers work on the quality of their teaching. Another participant stated, “ASMs highlight our weaknesses in teaching and ask us to improve them. They give us feedback on how to improve our weaknesses. For example, one ASM gave me some examples and asked me to use group work in my classes.”

On the other hand, most teacher participants argued that the exchanged feedback between ASMs, principals, and teachers is often poor and ineffective. For example, some teachers stated that when principals conduct observations, they mostly focus on completing their diagnosis books—writing a report on what activities the teacher used—they rarely focus on the teachers’ growth. Moreover, some teachers argued that the classroom observations by principals and ASMs do not often contribute to increasing dialogues between the administration/educational authorities and the teachers. The observation and supervision reports written in the diagnosis books by ASMs and principals depict this issue. The following excerpts are classroom observation notes taken from two principals’ diagnosis books:

Excerpt 1:

The teacher was on time. He had a lesson plan. The lesson was taught based on the lesson plan. The teacher used a student-centered teaching method. Students were encouraged to participate throughout the lesson. Homework was assigned. The teacher’s time management was good.

Excerpt 2:

The primary steps were accomplished. The previous lesson was reviewed. The title of the lesson was written on the board, but no technique was used to motivate students. Using the instructional materials, students were asked to repeat the lesson. Group work was used. The students were interested in the lesson. Homework was assigned to students. In the end, some necessary instructions and guidance were provided to the teacher.

Since the principals do not use a specific observation form, the exact amount of time spent watching different lesson stages is not described in the reports. For example, the above two observation reports’ length varies as the principals are not required to complete an observation form. Moreover, some of the observation notes are broad or vague. For example, the words good or great are not clear in these two sentences: “the teachers’ time management was good,” “the teacher did a great job explaining the lesson.” These observation feedback reports might not be considered constructive because they do not depict what activities went well and what changes should be seen in the future. Also, a hard copy of these reports is not shared with the teachers, and they do not contribute to increasing dialogues between the observer and the teacher. Teacher 1, Urban School A stated that their principals did not hold pre-or post-conference to discuss the plan or feedback.

When ASMs visit schools, they write a report regarding their school visitation. The following excerpts demonstrate the ASMs’ written feedback regarding their school visitations:

Excerpt 1:

I checked and evaluated administrative books. The teachers were assigned to teach subjects based on their discipline/major. They were all in their classes with proper clothing, and they had their books and lesson plans. Although the teachers do not have access to equipment and resources, they did a pretty good job when I visited their classes. The school laboratory is active, and it is used when they need it. This school suffers from a lack of desks for students and chairs and desks for teachers. They also need five classrooms and three teachers for specific subjects.

Excerpt 2:

Today we visited this school and checked its administrative and pedagogic activities. We appreciate their hard work and effort. May God grant them more energy and power so that they serve their country.

The above feedback written after school visitations by ASMs indicates that they rarely exchange detailed and constructive feedback. They are required to write their guidance and suggestions on how to address the challenges and weaknesses they observed at schools in the school diagnosis book (Ministry of Education, 2017), but we found that most of the collected school visitation reports written by ASMs follow similar diction and format—starting with an introduction, highlighting some routine school activities, and thanking the principal and the teachers. Their feedback/reports are not based on a specific form or guideline. Although ASMs are required to write the date of their next school visitation in the school diagnosis book (https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/brief_cqi_in_head_start_finaldraftcleanv2_508.pdf on Using Teacher Observation Form, 2017), we found that none of the ASMs did so, and the reports are not linked to the previous school visitations. That is, a new report does not track the challenges highlighted in the previous visits.

When ASMs visit schools, they collect information regarding teacher performances from principals as well. They specifically check the principals’ diagnosis books to see whether principals collect information about teachers’ practices regularly or not. However, we found that ASMs do not give feedback on the method and the quality of the exchanged information between teachers and principals—as long as the diagnosis books indicate that observations are done, principals are not questioned. Some participants stated that ASMs’ view of supervision is still limited to criticizing teachers. Teacher 2, Urban School A argued that ASMs need to learn how to build rapport with teachers; otherwise, teachers perceive ASMs as inspectors. Similarly, some teachers claimed that ASMs do not have the qualifications that an ASM needs. For example, Teacher 3, Urban School B indicated that many ASMs are not professional in supervising teachers. She asserted:

ASMs generally don’t usually give feedback in a friendly way. I would be happy if an ASM says my weaknesses and guides me on teaching better in the future. The ASM goes to our office and tells the principal, or sometimes in front of other teachers that the teacher I observed had these problems. This feedback won’t help teachers to improve. It is not shared in a friendly way, and it is not confidential.

The rural teacher participants claimed that some rural schoolteachers do not receive a chance to communicate with ASMs regarding their needs. According to one PED participant, insecurity and lack of transportation facilities prevent ASMs from visiting schools in many districts. He also noted, “in some districts, there are schools which are about 70 km away from the center of the district. The roads are insecure and difficult to travel”. He concluded that besides insecurity and lack of transportation facilities, there is a strong need to increase ASM staff in Herat.

We found that the absence of a specific filing system on teacher supervision and TPD quality assurance. The evaluation forms completed by the ASMs are not shared with the teachers and the principals. They share their reports with their DED academic supervision heads. They share their reports with their DED academic supervision heads. The ASMs write the reports of their school visitation on the diagnosis books kept in schools; however, the reports are very general (see the two example excerpts mentioned above). The reports are not written based on a specific format, mentioning the report’s length, criteria, and components.

4. Discussion and conclusion

This qualitative research aimed to investigate how feedback loops regarding TPD programs within the MoE/PED are perceived to function by teachers, principals, ASMs, DED, and PED authorities. This section interprets and discusses the findings considering the existing scholarly literature and share the overall conclusions, their implications, and the study limitations and future directions.

4.1. Feedback processes on TPD Programs

The findings indicate that feedback loops do not function properly within and beyond schools regarding TPD programs, because proper and regular feedback is not collected from the stakeholders, especially teachers, and the rarely collected feedback is not properly analyzed or used for improving the TPD programs. The teacher participants were not consulted about their needs and expectations before teacher training programs were designed and delivered, and there was no systematic follow-up or evaluation of the delivered training workshops by the TPD providers to collect the trained teachers’ feedback. The findings also indicate that the current processes does not inform teachers and principals whether the rarely collected feedback was used in decision makings or not and how. Reporting back to the beneficiaries and letting them know their voices were valued and considered will create trust and help make the stakeholders more committed to the feedback system and more willing to share their feedback in the future.

Although the literature on feedback loops stress the importance of engaging beneficiaries in multiple stages of the feedback loops (e.g., Bonino et al., Citation2014; Feedback Labs, Citation2017; Whittle, Citation2015), the findings indicate that educational authorities did not conduct needs assessments prior to designing and implementing TPD programs and the primary beneficiaries of TPD programs were not consulted before designing the programs. The central MoE makes many decisions about Herat TPD programs. The educational stakeholders in schools have no voice on the types, frequency, length, and contents of the training; thus, the programs are not perceived based on their needs. For example, the participants stated that although many teachers needed to participate in subject-based training, the training modules designed and delivered were mostly on teaching methodology.

We found that Herat TTC trainers mostly delivered the TPD programs implemented in Herat, but they did not observe teacher classrooms to understand their needs and receive feedback. ASMs, principals, and headmasters are those how are supposed to observe teacher classrooms. The latter group did not participate in the teacher training programs and were not aware of the TPD details, which hinders their ability to support teachers and evaluate their effectiveness. This seems to be a systemic flaw in the feedback mechanism around TPD.

The analyses also indicate that teacher supervision at schools is poor because some ASMs and principals do not have the qualifications and skills to provide feedback and listen to teachers’ feedback. ASMs and principals have a significant role in the feedback mechanisms because they evaluate teachers’ performances at schools and supervise them about their practices. It is important to improve these stakeholders’ capacity to develop their knowledge of collecting, analyzing, and responding to feedback because they are the “agents of change at all levels of the system” (Kuji‐Shikatani et al., Citation2016, p. 264). The findings showed that ASMs and principals did not have sufficient knowledge and skills to gather and communicate feedback on teachers’ performances; thus, they could not collect the right information.

The findings also indicate that the collected feedback is not inclusive because some TPD beneficiaries’ voices are not collected. Not all stakeholders receive the same opportunity to voice their concerns and communicate feedback. For example, Teacher 10, Rural School B claimed that ASMs rarely conduct teacher observations to collect feedback on what these teachers need. As a result, those who have been marginalized stay marginalized—their feedback is not collected and used in decision making. In other words, when data on what TPD beneficiaries need are not collected, TPD providers are not likely able to create sustainable solutions for the individuals they serve (Feedback 101, Citationn.d.). The MoE should empower all stakeholders involved in the feedback loops to feel comfortable and safe to share their concerns regarding different issues. Those stakeholders who have been disempowered and marginalized (e.g., CBE teachers, rural schoolteachers) might need more support to voice their concerns without fear. To keep the feedback confidential, different feedback systems should be created to collect reliable feedback from schools. Developing a rewarding and punishment system for feedback communication and creating a complaint and response mechanism through which stakeholders voice their complaints and receive a response to their complaints could address this gap.

4.2. Feedback communication structures concerning TPD Programs

The findings indicate that communicating issues from schools to the central MoE is very lengthy. If schools send their requests or issues by official letters, it will take a long time to receive a response. Academic supervision members also do not visit schools regularly and often, so when teachers share their feedback or concerns with them, they do not hear a response at all or after a very long time. Since education systems are considered complex systems, it is significant to communicate feedback quickly; their meaningfulness and urgency would change over time because feedback data has a short shelf life (Q. M. Patton, Citation2016).

Moreover, the analyses yielded that the current feedback collection on teacher performances is manual and paper-based. Digital technologies, such as the internet, are not used at all. This study, based on the literature such as Whittle and Campbell (Citation2019) and Feedback Labs (Citation2017), recommends that the MoE use the capacity of ICT to increase the reach, speed, and efficiency of the process. Presently, teachers in remote and insecure areas receive no or little chances to exchange feedback regarding their profession. The use of digital feedback systems can facilitate communication and analysis of more regular feedback from different stakeholders, including teachers in rural areas. For example, the MoE can create a free text messaging system through which teachers get the chance to voice their concerns by sending text messages. Rural areas have access to mobile phone services. This provides the opportunity to collect feedback from far and insecure areas. An online feedback collection database could also improve the feedback’s effectiveness as more participants might feel comfortable sharing their ideas, especially when the feedback is collected anonymously.

The mechanisms for collecting, analyzing, and using feedback are not properly defined and established at the MoE/PED. As in the findings section indicates, principals and academic supervision members have the key roles in the communication between teachers and higher authorities at the PED and the central MoE. Although the system is designed for two-way communication and exchange of feedback between schools, the PED, and the central MoE and vice versa, the collected information is often the supervisors’ or principals’ assessment of teachers’ needs rather than teachers’ feedback or issues. The system communicates the principals’ and supervisors’ assessments to the higher authorities and communicates back the higher authorities’ decisions and directives.

The MoE should develop clear guidelines for different stages of the feedback loops and offer continuous capacity-building programs for the stakeholders on how to initiate, communicate, analyze, and respond to feedback. For example, principals need to be trained to elicit feedback from students, teachers, and headmasters regarding TPD programs during their classroom observations and teacher meetings. They also need to be trained to document and analyze the collected feedback, share feedback with the higher authorities, and share the lessons learned from the collected feedback with beneficiaries.

The findings demonstrated that the rarely exchanged feedback between TPD providers and TPD beneficiaries had not led to any major improvements in the MoE TPD policies or programs. We did not find any evidence of organizational learning that happened using teachers’ feedback within the MoE regarding TPD programs. Feedback loops function well when a culture of learning and evidence-based decision-making exists in an organization. That will create demands for feedback data. It is important to foster a culture of learning and evidence-based decision-making in the MoE.

The findings imply that the culture of accountability towards improving students’ learning is weak. There is not a system to assess students’ learning beyond teacher-led examinations. Principals and academic supervision members do not assess student learning. Teachers do not seem to be accountable for improving students’ learning outcomes. They are held accountable for administrative issues, such as attendance and lesson plans. It means that as long as they come to school, deliver lessons, administer exams, they are fine, even if students are not learning.

The findings also indicate that teachers are not held accountable for their learning. According to one ASM, “only a small percentage of schoolteachers think about their continuous progress and growth as teachers.” Likewise, Teacher 5, Urban School C stated that schoolteachers are not held accountable for their improvement as long as they get a score above 60 during the observations conducted by the ASMs. As a result, according to Teacher 1, Urban School A, this has negatively affected many teachers’ intentions for participating in TPD programs. If the schools, the DED, and the PED authorities were kept consistently accountable for improving students’ learning outcomes and addressing the issues raised by ASMs and principals, they would find the feedback mechanisms meaningful and exchange and use feedback data more regularly.

Adaptive management requires flexible systems to adapt the policies and activities based on continuous feedback (O’Donnell, Citation2016; USAID, Citation2020). This seems very difficult to achieve in a highly central and bureaucratic educational system in Afghanistan. As data showed, the focus of teacher meetings, academic supervision, the principal meetings with DED was on administrative issues and the implementation of the MoE bylaws and regulations. However, it is necessary for the MoE to become a more flexible, decentralized, and adaptive system to adjust its policies and programs and increase its effectiveness and sustainability. The literature emphasizes that either decision should be made based on the collected feedback and needs assessment or the authority and power given to stakeholders to initiate and implement programs based on their needs. For example, Morrison (Citation2008) proposes that educational authorities need to devise TPD policies that emphasize the significance of “local and institutional decision-making” (p. 21) if they plan to have quality and sustainable educational programs.

4.3. Limitations and future directions

The present study had some limitations. Our study did not explore all possible steps of the feedback loops within the MoE/PED. More research is needed to better explore and demonstrate the effectiveness of each step of the feedback loops (i.e., collect, analyze, present and discuss, and adapt) in detail. Observing and tracking each step in the feedback loops could substantiate our results with the stakeholders’ real-time treatment of such complex situations. This could be an agenda for further research.

Besides, since we did not collect data through observations, we did not have robust data on the stakeholders’ attitudes and behaviors toward feedback loops and organizational learning. Further studies with more focus on the culture of learning and improvement within the MoE are therefore recommended.

Moreover, this study’s findings depended heavily on interviews and documents as data sources in this study. Further research can include observation of stakeholders’ behaviors involved in the feedback processes. That will help us triangulate our findings and acquire a more in-depth understanding of the phenomenon.

Additionally, considering the different feedback process steps, our study’s missing voice was TPD designers and authorities in the central MoE. Since our research focus was narrowed to Herat Province, we did not collect data from TPD designers and central MoE authorities in Kabul. With these stakeholders’ inclusion, further research better sketches out the feedback loops within MoE and helps us understand how the feedback data are collected, communicated, analyzed, and used in decision-making.

Authors note

This study is made possible through participation under a United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funded contract with Creative Associates International. The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of USAID, United States Government or Creative. The authors do not have any conflict of interest to disclose. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Mohammad Javad Ahmadi at [email protected].

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohammad Javad Ahmadi

Mohammad Javad Ahmadi received his Ph.D. in Educational Policy and Leadership in 2017 from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. His research interests include early literacy, curriculum reform, and teacher professional development. He has worked as a consultant with several international organizations such as World Bank, Creative Associates, UNESCO, and FHI-360. He led this study as part of the Afghan Children Read Project research initiative.

Mamdouh Fadil

Mamdouh Fadil is a Postdoctoral Associate of the School of Global Studies at the University of Sussex. His current work focuses on education reform and youth. He led education reform programs in the Middle East and Asia. In 2014, he obtained Ph.D. in Social Anthropology from the University of Sussex, UK.

Mir Abdullah Miri

Mir Abdullah Miri is a faculty member at Herat University, Afghanistan. He holds a master’s degree in TESOL from Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA. He is currently doing his Ph.D. in TEFL at Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran. His research interests include educational leadership, teacher identity, and teacher education.

Notes

1. INSET I was on general pedagogy; INSET II on teaching specific subjects from Grade 1–9; INSET III on teaching literacy and numeracy in Grade 1–3; INSET IV on teaching language and math Grade 1–6; INSET V on advanced pedagogy; and INSET VI on self-assessment and reflective teaching.

References

- Afghan Children Read. (2017). Feedback loop mechanism assessment draft report.

- Argyris, C. (2004). Reasons and rationalizations: The limits to organizational knowledge. Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Massachusetts. Addison-Wesley.

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. A. (1996). Organizational learning II. Addison-Wesley.

- Bonino, F., With Jean, I., & Knox Clarke, P. (2014). Closing the loop: Practitioner guidance of effective feedback mechanism in humanitarian contexts. ALNAP-CDA Guidance. ALNAP/ODI https://usaidlearninglab.org/sites/default/files/resource/files/closing-the-loop-alnap-cda-guidance.pdf

- Buczynski, S., & Hansen, C. B. (2010). Impact of professional development on teacher practice: Uncovering connections. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 599–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.006

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Effective_Teacher_Professional_Development_REPORT.pdf

- Derrick-Mills, T. (2015). Understanding data use for continuous quality improvement in head start. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/51211/2000216-understanding-data-use-for-continuous-quality-improvement-in-head-start.pdf https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/brief_cqi_in_head_start_finaldraftcleanv2_508.pdf

- Feedback 101. (n.d.). What do people want? Are we helping them get it? If not, what can we do differently? Rederived from https://feedbacklabs.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Feedback-101.pdf

- Feedback Labs. (2017). What is feedback? Retrieved September 28, 2020, from https://www.feedbacklabs.org/about-us/what-is-feedback/

- Goetz, T. (2011). Harnessing the power of feedback loops. Wired Magazine, https://www.wired.com/2011/06/ff_feedbackloop/

- Halverson, R. (2010). School formative feedback systems. Peabody Journal of Education, 85(2), 130–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01619561003685270

- Heirman, J., Ling, A., & Pinto, Y. (n.d.). The use of feedback in M&E. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. http://www.czech-in.org/EES/Full_Papers/37570.pdf

- INTRAC. (2016). Using beneficiary feedback to improve development programmes: Findings from a multicounty pilot. http://feedbackmechanisms.org/public/files/BFM-key-findings-summary.pdf

- Jacobs, A. (2010). Creating the missing feedback loop. IDS Bulletin, 41(6), 56–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00182.x

- Kleinfeld, R. (2015). Improving development aid design and evaluation: Plan for sailboats, not trains. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/files/devt_design_implementation.pdf

- Kuji‐Shikatani, K., Gallagher, J. M., Franz, R., & Börner, M. (2016). Leadership’s role in building the education sector’s capacity to use evaluative thinking: The example of the Ontario Ministry of Education. In M. Q. Patton, K. McKegg, & N. Wehipeihana (Eds.), Developmental evaluation exemplars: Principles in Practice (pp. 252–270). The Gulford Press.

- Ministry of Education. (2006). INSET 1 training materials: Student readings. Kabul Ministry of Education. https://moe.gov.af/sites/default/files/2020-05/%D9%85%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AF%20%D8%A7%D9%93%D9%85%D9%88%D8%B2%D8%B4%DB%8C%20%D8%A8%D8%B1%D8%A7%DB%8C%20%D9%85%D8%B7%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%87%20%D9%85%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86%20%D9%88%20%D8%B3%D8%B1%D9%85%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86.pdf

- Ministry of Education (2013a). INSET III training material. Kabul Ministry of Education. https://moe.gov.af/sites/default/files/2020-03/Final%20Math%20Grade%2010%20-12%20final%20Dari%20colar%204-7-13%20final.pdf

- Ministry of Education (2014a). INSET IV training material. Kabul Ministry of Education. https://moe.gov.af/sites/default/files/2020-03/INSET%204%20%28grade%201-6%29%20%2025%20Oct%202014.pdf

- Ministry of Education (2014b). INSET V training material. Kabul Ministry of Education. https://moe.gov.af/sites/default/files/2020-03/Advanced%20Pedagogy%20Dari%2003-03-2014.pdf

- Ministry of Education (2016). INSET VI training material. Kabul Ministry of Education. https://moe.gov.af/sites/default/files/2020-03/INSET-6%20Resource%20Book%20Dari.pdf

- Ministry of Education. (2018). Education joint sector review. https://moe.gov.af/sites/default/files/2020-01/Education%20Joint%20Sector%20Review%202018.pdf

- Molina, E., Trako, I., Matin, A. H., Masood, E., & Viollaz, M. (2018). Afghanistan’s learning crisis: How bad is instructional time really? World Bank Blogs: https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/afghanistan-s-learning-crisis-how-bad-it-really

- Morrison, K. (2008). Educational philosophy and the challenge of complexity theory. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00394.x

- O’Donnell, M. (2016). Adaptive management: What it means for CSOs. Bond. https://www.bond.org.uk/resources/adaptive-management-what-it-means-for-csos

- Patton, M. Q. (2010). Developmental evaluation: Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. Guilford Press.

- Patton, M. Q. (2011). Developmental evaluation: Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. Guilford Press.

- Patton, Q. M. (2016). State of the art and practice of developmental evaluation: Answers to common and recurring questions. In M. Q. Patton, K. McKegg, & N. Wehipeihana (Eds.), Developmental evaluation exemplars: Principles in Practice (pp. 1–24). The Gulford Press.

- Pocklington, K., & Wallace, M. (2002). Managing complex educational change: Large scale reorganisation of schools. Routledge Falmer.

- Popova-Nowak, I. V., & Cseh, M. (2015). The meaning of organizational learning: A meta-paradigm perspective. Human Resource Development Review, 14(3), 299–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484315596856