Abstract

This research was carried out to investigate whether audio-visual feedback affects students’ writing components and overall writing performance in flipped or traditional instruction. To reach the aim, the researchers used two experimental groups of medical students at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences; experimental group 1: audio-visual feedback was provided plus flipped instruction; experimental group 2: audio-visual feedback was provided plus traditional writing instruction. The researchers used 50 students’ writing scores and examined the effect of audio-visual feedback on students’ writing component(s): (content, organization, vocabulary, language use, and sentence mechanics) and their overall writing performance in both classes. For the pre-test data at the beginning of the semester, students were asked to write a paragraph, and after 3 months, for the post-test, students’ midterm exam data were collected and analyzed. The researchers applied nonparametric tests to answer the research questions including the Mann–Whitney and Wilcoxon Signed Rank Tests since the distribution of the scores was not found normal. According to the results, post-test mean scores of all-writing components and all-writing performance in the flipped and traditional-instructed groups were greater than those in the pre-test. It shows that audio-visual feedback improved the writing skills of the participants in both groups. Furthermore, all writing components and writing performance of students in the flipped-instructed group outnumbered their counterparts in the traditional group. It revealed that using audio-visual feedback in the flipped instruction has a more positive effect on improving students’ writing components and writing performance compared with the traditional writing instruction.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Language teaching and learning are changing constantly. Nowadays, regarding the development of technology, students have completely different expectations. Today, we cannot find a language class that does not incorporate several forms of technology. Besides, it is hard to overcome some difficulties regarding teaching and learning via traditional approaches. Therefore, instructors, today must try to create new teaching approaches that address the needs of this generation. In the case of writing performance, different pros and cons have been offered by various experts for providing audio-visual feedback through different technological equipment in improving students’ writing performance, which revealed positive effects. Hence, the researchers in this study attempted to identify the effect of audio-visual feedback on promoting students’ writing performance and to understand whether this method would be more useful in flipped or in traditional instruction because each mode provides its merits and demerits.

1. Introduction

Among the four skills in learning English, writing in English is considered the hardest and most complicated one for particularly EFL students simply because it is not in their native language and they have a limited chance to write in English. Furthermore, writing is generating, arranging, and translating of ideas into a readable text. Therefore, it seems common that many learners particularly those of foreign language learners have some degrees of difficulties in writing. (Rattanadilok Na Phuket & Othman, Citation2015; Watcharapunyawong & Usaha, Citation2013). Furthermore, promoting writing instruction is a multifaceted task as writing is deemed as one of the important skills, which is needed by ESP learners in the academic domain (Shahini, Citation1988, as cited in Nourinezhad et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, proficient academic and scientific writing skills are vital for higher education students who need to write coherent and effectively structured texts and publish them in international journals throughout their studies (Barroga & Mitoma, Citation2019; Shahsavar & Asil, Citation2019). Despite all the efforts to enhance students’ writing performance, in terms of writing instruction and feedback provision, nothing has been changed since the traditional style curriculum for writing is still implemented in many higher education settings (McCarthey & Ro, Citation2011).

A newer trend in writing instruction, however, both in terms of writing instruction and feedback provision, has shown promising results (Noordin & Khojasteh, Citation2021). Technology-based instruction and technology-based feedback have given teachers more opportunities to devise innovative strategies and techniques to help those who do struggle with writing.

Furthermore, students of the twenty-first century often know significantly more about computers and digital systems compared to their teachers, and they prefer to receive materials digitally where it is more accessible, and many avenues for writing (and other communication skills) have flourished in the digital milieu (Kashefian-Naeeini & Sheikhnezami-Naeini, Citation2020). The tools of a flipped model in teaching materials are becoming more ubiquitous each year, both in and out of the classroom. Nearly all college students carry a smartphone and many must be prepared for the interaction between technology, schools, and achievement.

Although much enthusiasm has been generated in the studies conducted about the flipped classroom, there has been scant academic work to assess when this method is most effective (Ferrer & García-Barrera, Citation2014). Even though some researchers believe that it is no longer needed to compare traditional classrooms to multimedia learning supplemented classrooms to prove that multimedia contents are effective for students (see, for example, Ellman & Schwartz, Citation2016), we thought since we are dealing with EFL students taking a compulsory writing course, it is essential to compare our experimental group (here a combination of flipped instruction and audio-visual feedback) to the traditional one (here traditional writing instruction plus audio-visual feedback) to report more solid and reliable findings. Furthermore, while several studies (e.g., Brick & Holmes, Citation2014; Henderson & Phillips, Citation2014) have concentrated on the role of computerized feedback technologies, few studies have investigated methods to enhance writing instruction through technologies that facilitate teacher-generated e-feedback.

To fill this gap, this study aimed at investigating the effect of audio-visual feedback on writing components and writing performance of medical university students in the flipped and traditional instruction and to know if giving a combination of audio-visual feedback and flipped instruction is more practical in promoting students’ writing performance compared to giving audio-visual feedback in traditional writing instruction classrooms.

2. Review of literature

2.1. Effective teacher’s feedback

According to Mousavi and Kashefian-Naeeini (Citation2011), “writing is one of the most important tools in expressing new ideas and concepts” (p. 594). However, one of the most important factors teachers face in writing classes is how to provide feedback to students’ writing assignments. Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007) recommend that providing useful and effective feedback is a vital aspect of a successful evaluation strategy. Based on the research conducted by Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007), which reviewed 196 studies on feedback, it was revealed that effective feedback can almost double the average student progress over a school year. Wiliam (Citation2010) reports that studies on feedback depict the accelerated phases of student learning by at least 50%, meaning student learning is promoted by an additional 6 months or more over a year. In their earlier research, Black and Wiliam (Citation2009) stated that many of the studies determine that improved feedback helps lower-achieving students compared to higher achieving students, and while reducing the gap between higher- and lower-achieving students, feedback enhances the overall standard of attainment among them. According to Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007), eagerness to involve in such feedback depends on the transaction costs, and that feedback is most influential if learners’ confidence in their production is high.

Although feedback can be very effective, especially in writing classes, Lee (Citation2008) believes that in teacher-written feedback, there is a gap between what teachers give and what students like to understand. This gap between the students’ intention and those of the teacher can endanger the effectiveness of the written feedback; therefore, it often makes students feel confused about how to adjust the feedback in their revising task (Lee, Citation2008). However, several alternatives to traditional feedback techniques, for both summative and formative assessment, have been explored. The study of Hepplestone et al. (Citation2011) shows the growing use of technology to improve the evaluation process in higher education. They indicate that the use of electronic or online tools is affecting the nature of feedback and students’ perception.

2.2. Audio-visual feedback

Audio-visual feedback is technology-enhanced feedback that is usually compared with written-only feedback. In audio-visual feedback, an instructor makes a screencast video using images, pictures, animation, illustrations, drawings, and narration rather than simply words to provide feedback to the learners (Cavaleri et al., Citation2019).

By talking to students and reading their papers aloud, instructors can engage learners in an interpersonal level that is not present in the written comments (Borup et al., Citation2015). Audio-visual feedback presents students an opportunity to hear the emotional response and reaction that is more obviously transferred through spoken words than written (Thompson & Lee, Citation2012). In another study conducted by Thompson and Lee (Citation2012), screencast software was applied as a tool to talk to learners about their work-in-progress. To record 5 min of audio-visual commentary about a student’s work, they employed Jing screen-recording software. The software allowed them to save the comments as a flash video that could be emailed or uploaded to an electronic dropbox. According to their study, most learners believed that they understood video feedbacks in a more meaningful way than written comments. Through audio-visual feedback, learners could hear what was confusing about a sentence (rather than just a written phrase indicating the error type); therefore, they were more eager to attempt the revision.

In another related study, Tajalizadeh Khob and Rabi (Citation2014) provided Iranian EFL learners with audio-visual comments as an alternative to teacher-created written feedback and focused on its meaningfulness to create an incentive medium for the learners and boost their motivation. Their results revealed that audio-visual meaning-focused comments are not only efficient in enhancing learners’ motivation to write but also can change the negative opinion of the learners. This factor is very important especially for EFL students who are reportedly very reluctant towards their English classes at the university level (Khojasteh et al., Citation2016).

In another research conducted by McCarthy (Citation2015), when exploring the video model, the major benefit was the clearness of the feedback provided. The video feedback was also considered as the most suitable kind of feedback for the project work in class. Learners realized that they were working in a predominantly visual medium and appreciated this mode of feedback as well; in this regard, file size and download time were considered as the only disadvantages of the video feedback (McCarthy, Citation2015).

Attali (Citation2015) also supports multiple try feedback. Multiple try feedback is formative feedback that allows the students multiple tries to answer questions through a delivery method used through the technological progress of today’s programs. Therefore, the student can review their work and find any misconceptions they have, and correct them while still learning the proper concepts through technologically provided lessons and feedback. One major aspect of Attali’s (Citation2015) study shows how students can recall and perform the same concepts several days after a given evaluation.

In more recent research, Kerr et al. (Citation2016) explored whether or not audio-visual feedback has an impact on learners’ performance. Compared to traditional written feedback, the authors identified that learners consider audio-visual feedback as a superior feedback mode. Although it may not match with all types of assignments, or be suitable for all types of learners, the instructors indicated a potential path for its application. However, an examination of attainment revealed that despite students overwhelming support for the audio-visual feedback mode and believing it would have a positive impact on their next task result, it did not have any important impact on students’ attainment (Kerr et al., Citation2016).

Similarly, in a study conducted by Ali (Citation2016), there was an apparent difference in writing performance between learners who received screencast feedback and those who received traditional written feedback. The former groups tend to outperform the latter in higher-level concerns of writing. Other researchers also found promoted guidance for learners with the screencast and students’ better involvement in the revision procedure (see Daniel, Citation2013; Elola & Oskoz, Citation2016; Halwani, Citation2017; West & Turner, Citation2016).

2.3. Writing in the flipped classes versus traditional classes

As Bartlett (Citation1994) stated, traditional writing instruction is revealed by some as a teacher-controlled approach that focuses on preprinted materials namely, textbooks and worksheets. Traditional instruction, as claimed by Tidwell and Steele (Citation1995), is a series of teacher-determined skills that is usually taught without a writing context. In traditional instruction, learning is conducted in a synchronous environment; that is to say, the students must be in the same place and at the same time to learn the materials (Chickering & Gamson, Citation1987). In teacher-centered instructional delivery methods, teachers deliver the information to the students while the students are only the recipients of the information provided, making them passive participants in the learning process (Jony, Citation2016). Perhaps this is the reason why it is often reported that students usually get bored easily and do not want to write due to the perceived hardship of foreign language writing although writing instructors do their best to help learners develop their writing competence, (Ekmekçi, Citation2018). As Kafipour et al. (Citation2018) put it, Iranian EFL learners have lots of problems with writing in English as one of the four language skills, and this may be due to the traditional teaching methods used in the writing classrooms.

What appears to be at the heart of this mode of instruction is the fact that nowadays the students have completely different expectations when compared to the past. Hence, it is too difficult to draw their interest in learning activities via the traditional teaching procedures (DeVoss et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, it is hard to overcome some difficulties regarding teaching and learning by traditional approaches. In this regard, the instructors today must try to create more teaching approaches that address the needs of this generation; therefore, several alternatives to traditional instructions and traditional approaches would be critical. The most promising method of turning traditional writing pen-and-paper-based classes into more innovative and engaging places is to implement new technologies that revolutionized the education system (Mayer, Citation2009).

The term flipped classroom refers to an inversion of where learning activities take place (Wilson, Citation2013). Although the focus of this method is on “moving tasks in time and space” (Abeysekera & Dawson, Citation2015, p. 2), making this change is intended to re-explain other aspects of the learning process, such as how content is provided by instructors. The theory proposes that socio-cultural conditions and environments can support and nurture these requirements (i.e., autonomy support), or they can disregard them (i.e., external control). Motivation to learn is promoted when the environment provides opportunities for students to (a) feel experienced in their ability, (b) feel a sense of connection to peers and teachers during the period of learning, and (c) be autonomous in self-regulating and decision-making.

In one study, Zheng et al. (Citation2018) explored the use of an integrated pedagogical tool for knowledge learning that combines offline and flipped classroom activities. The results showed superior learning outcomes, professional knowledge, and enhanced capabilities of the students. Likewise, AlJaser (Citation2017) measured the effectiveness of flipped classrooms in the academic achievement and self-efficacy of students. The results revealed that applying flipped classrooms made learning more productive and teaching as well as lecturing more interesting. It also encouraged learners to be more responsible over the process of learning.

2.4. Theoretical framework of the study

In this study, Mayer’s (Citation2009) cognitive theory of multimedia learning has been used as a framework to evaluate the pedagogical effectiveness of videos used for both instruction delivery and feedback provision in writing classes. This theory is proposed based on the ways with which a human mind works and suggests that multimedia instructional messages can lead to more meaningful and efficient learning. Integral to the overall theory of multimedia learning, Paivio’s dual coding theory suggests that simultaneous use of both visual and auditory channels can increase the capacity of working memory in learners and, in turn, they can learn more deeply in comparison to learning from words or pictures alone (Mayer, Citation2005).

If using verbal and pictorial representations would result in better learning outcomes, we expected the finding of our research to hold for a better writing performance in a flipped instruction where instructions are delivered in a digital format outside the classroom and more time is allocated in the classroom for communicative group practices. In terms of writing instruction at institutions of higher education, it is reported that the writing syllabus is often too packed to enable writing instructors to appropriately apply the mediation all students need (Grabe & Kaplan, Citation2014). Although flipped instruction does not necessarily involve technology, instructor-made videos viewed by the students at home would give writing instructors ample opportunities to transform their writing classes into a more interactive and dynamic place for students to learn due to interaction with students (Berrett, Citation2012). Under the premise of Mayer’s (Citation2009) cognitive theory of multimedia learning, single modality presentations (here, for example, listening to a writing lecture/lesson or reading a writing reference book) would not comparatively affect that dual sensory mode instruction would have (Coffman, Citation2011). Despite the positively reported implications of the flipped classroom instructional strategy, there is still a deep shortage of literature regarding the advantages of this mode of instruction for EFL learners in writing classes.

The principle of multimedia learning does not just concern instruction but also feedback. Multimedia feedback, here in this research, audio-visual feedback, is a type of teacher-generated

e-feedback that replaces conventional feedback (using text-based systems) on submitted work in the classroom settings. However, with today’s computer technologies and software capabilities, students can obtain a considerable amount of aural feedback out of the classroom and can survive the previous misinterpretations of their instructors’ intention over the comments or question marks in assignments (Perkoski, Citation2017). Moreover, a combination of the visual aspect of this kind of feedback and instructor’s conversational tone, verbal explanations, and personalized feel of audio-visual feedback allows for a higher degree of interaction between teacher and student and with the feedback itself, particularly for students with a lower level of English language proficiency (Cavaleri et al., Citation2019). In the audiovisual feedback, the instructor cares more about the student’s views and ideas than only a restricted emphasis on the form and grammar frameworks in writing (Tajalizadeh Khob & Rabi, Citation2014). Nevertheless, with teacher-provided feedback, there is always a question about whether this type of feedback helps the students or simply distracts, annoys, or overloads them (Perkoski, Citation2017).

Considering the above-mentioned information provided in the literature review, the study is guided by the following research questions:

1. Does audio-visual feedback affect students’ writing components and writing performance in the flipped instruction?

2. Does audio-visual feedback affect students’ writing components and writing performance in traditional instruction?

3. Is there any significant difference between the writing components and writing performance of students in the flipped and traditional instruction after receiving audio-visual feedback?

3. Methodology

3.1. Design of the study

A quasi-experimental design has been selected for the current study since purposive sampling has been used instead of a random selection. The researchers applied non-parametric statistics including the Mann–Whitney and Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test to answer the research questions since the scores were not normally distributed. They used two experimental groups of medical students at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (SUMS); experimental group 1: audio-visual feedback plus flipped instruction; experimental group 2: audio-visual feedback plus traditional writing instruction. To reach the aim, the researchers used 50 students’ writing scores and examined the effect of audio-visual feedback on students’ writing component(s): content, organization, vocabulary, language use, and sentence mechanics and their overall writing performance in both classes. For the pre-test data at the beginning of the semester, students were asked to write a paragraph, and after 3 months (12 weeks), for the post-test, students’ midterm exam data were collected and analyzed.

3.2. Participants

The population of this study was all the medical students studying at SUMS in the 2019–2020 fall semester; they had taken a 3-unit compulsory writing course. The researchers used purposive sampling and among 8 writing courses offered that semester, they used two writing classes that were instructed by the same writing instructor to be able to control the effect that various teaching instructions might have had on students’ writing performance. Another reason that the researchers decided to use purposive sampling was that only this writing instructor had the main instrument (a digital tablet) used in this study and also because only this writing instructor was giving audio-visual feedback throughout the semester to her two classes. Therefore, to conduct this study, it was a rational decision to use purposive sampling (Saunders et al., Citation2012) to collect the data from the classes that this particular writing instructor had during that semester. Each group consisted of 25 students (a total of 50 students) who were randomly scattered between two writing classes and their ages ranged from 20 to 24.

To make sure that these students were homogenous in their writing ability, their very first writing assignments were collected, marked, and analyzed. Asymp. Sig. for all the writing components and writing performance was greater than .05; therefore, we concluded that there was no significant difference between pre-tests of both traditional and flipped groups in terms of different writing components and writing performance; therefore, the two writing groups were homogenous.

3.3. Instrumentation

3.3.1. Medical students’ writing assignments

To collect the pre-test data, at the beginning of the semester, students were asked to write a paragraph with the following topic: “Childhood obesity is becoming a serious problem in many countries. Explain the main causes and effects of this problem and suggest some possible solutions”. Since the students were medical students and had passed the nutrition course in their previous year, the researchers thought this topic would be suitable since medical students had enough background information about the topic. After 3 months (12 weeks), for the post-test, students’ midterm exam data were collected and analyzed. The following topic was given to all medical students in both groups under the investigation: “Health promotion needs to be built into all the policies and if utilized efficiently, it will lead to positive health outcomes. How can we improve the health of our society?”.

3.3.2. Writing grading rubric

The Analytic Rubric (Jacobs et al., Citation1981) was used to score the participants’ writing samples. The scale assessed the medical students’ writing ability using 5 traits, including content, organization, language use, vocabulary, and mechanics. The content assesses the knowledgeable, substantive, thorough development of the thesis. The organization tests the fluency of expression, clarity in the statement of ideas, support, organization of ideas, and sequencing and development of ideas. The vocabulary examines the sophisticated range, effective word choice, word form mastery, and appropriate register. The language use concerns the use of effective complex construction, agreement, tense, number, and word order. The mechanics deals with the attention on the use of spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and paragraphing. The scores allocated to each trait were as follows: Content = 25, Organization = 25, Language use = 25, Vocabulary = 15, and Mechanics = 10. The total mark was 100 points. The writing rubric can be seen in Appendix A.

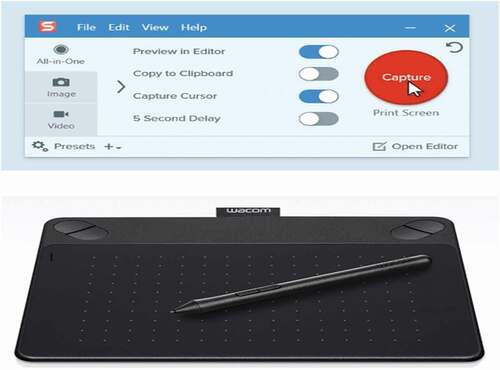

3.3.3. Screen capture and video recording software: Snagit

To capture the video displays and audio outputs, the writing instructor in both groups used Snagit which was a screenshot program used throughout the study. Snagit creates images and videos to give feedback, create clear documentation, and show others exactly what you see, so it was the best available program for the writing instructor to provide feedback to her students. It can be seen in Appendix B.

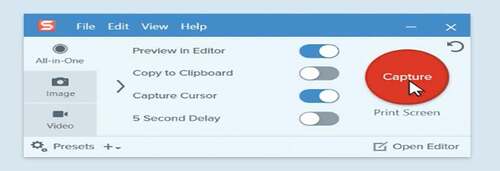

3.3.4. A writing tablet to give feedback

To explain concepts visually, the writing instructor of both groups used Intuos Art Creative Pen and Touch tablet throughout the study. While Snagit was capturing the entire session, the instructor used a writing tablet to provide feedback to the medical students. Having different brushes, highlighters, and colored pens or pencils, the writing instructor could give color-coded feedback to medical students to make this process more effective. A sample of the given electronic feedback can be seen in .

3.3.5. Writing video contents used in the flipped instruction

Since 30% of the writing instructions in all majors in medical universities in Iran could be flipped, out of 17 weeks of writing instruction comprising of 34 one-and-a-half-session writing lessons, 6 sessions were flipped using a pre-recorded grammar lessons recorded professionally in the Virtual University of Medical Sciences. These lessons were uploaded in the Learning Management System known as LMS and could be accessed only to the students instructed by flipped method group. To make sure that the videos cannot be reached to the students instructed by the traditional method, all videos were un-downloadable, so the students had to access their LMS any time they wanted to watch the videos. It is worth mentioning that the LMS website requires the student’s ID number and the password made by the student himself/herself.

3.4. Data collection procedure

3.4.1. Experimental group1: flipped classroom plus audio-visual feedback

Students in the experimental flipped classroom group received flipped instructions for only 30% of their course content and were trained on the first two sessions on accessing, interpreting, and using the received flipped instructions (teacher-made videos) and digital feedback. Then the writing instructor uploaded all the video contents to the learning management system (LMS) to be accessed by the students in this group. During this academic writing course, the instructor assigned the students different writing tasks, and students were required to write their assignments at home as part of their class activity and handed in their typed assignments (no hand-written assignments were allowed) to their writing instructor via email or WhatsApp. Then the writing instructor provided audio-visual feedback to every one of the students separately and sent back the recorded audio-visual feedback to the students via WhatsApp.

3.4.2. Experimental group2: traditional writing instruction plus audio-visual feedback

Students in this group received traditional instruction; however, they were still receiving audio-visual feedback for their assignments. The traditional instruction consisted of teaching all the contents covered by the flipped group, such as the structure of the paragraph, process paragraph, compare and contrast paragraph, etc.; however, the grammatical lessons including sentence types, parallel structure, subject-verb agreement, adjective clauses, noun clauses, and adverbial clauses were taught to students in the classroom, and they were asked to do the assignments at home. In the following sessions, the writing instructor provided the answers to the students in the classroom and ensured that they do not have any problems accordingly.

3.5. Data analysis

To answer the research questions, the researchers analyzed the collected data by SPSS Software version 16. First, the normality of the scores was tested. The scores were not normally distributed; therefore, the researchers applied nonparametric statistics including Man-Whitney and Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare differences between two independent groups (flipped and traditional instructions). Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test was used to compare differences within two dependent and paired groups (pre-and post-test of flipped vs. pre-and post-test of traditional instruction).

3.6. Reliability test

Since the researchers were dealing with the human rater, it was suggested by Nueuendorf (Citation2002) to ask at least another rater to rate the written assignments of medical students in two phases of the data gathering. Reliability has been described as the extent to which a measuring procedure produces the same outcome on the repeated trials (Carmines & Zeller, Citation1979). So among all the university lecturers teaching English to medical students at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, the researchers asked two of them to mark the papers for content, organization, word choice, sentence structure, grammar, and mechanics as was mentioned in the rubric. To make sure that the raters were in the same line as one another, the researchers had a two-hour session practice with the raters to clarify all the elements of the writing rubric. Then 50 assignments of the pre-test and 50 assignments of the post-test were given to raters, and they were asked to return the papers within 1 month. To prevent subjectivity in marking the assignments, neither the researchers nor the writing instructor of the two groups marked the papers. Finally, the inter-rater reliability was calculated for both the pre-test and post-test using a t-test, according to and .

Table 1. Raters’ reliability test scores in pre-test

Table 2. Raters’ reliability test scores in post-test

As can be seen in both tables, and , the significance levels for the raters’ mean scores were 0.678 and 0.725 in the pre-test and post-test, respectively, which were higher than the P-value of 0.05. Therefore, there was no significant difference between ratings which showed the reliability of the rating done by the raters.

3.7. Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations were taken into account and the necessary permission was taken from the officials of the department of English language. Then, full permission was granted from students and the writing instructor, and they were assured that the results would be used only for research purposes.

4. Results

4.1. The first research question

Does audio-visual feedback affect students’ writing components and writing performance in the flipped instruction?

As shown in , post-test mean scores of all the writing components in the flipped-instructed group outnumbered their counterparts in the pre-test. It shows that audio-visual feedback which was used as a treatment in this group improved the writing components of the participants. Moreover, the post-test mean scores varied between different writing components that show audio-visual feedback did not equally affect different writing components. To see if these differences were statistically significant, Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was conducted. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test showed that Sig. level for posttest-pretest differences is .000 which is lower than .05. It depicted a significant difference between mean scores of different writing components. Therefore, it can be concluded that audio-visual feedback significantly affected all the writing components in the flipped-instructed group while organization (m = 24.24, Z = 4.410) as one of the writing components was affected by audio-visual feedback more than other components; this followed, respectively, by content (m = 24.12, Z = 4.405), language use (m = 23.72, Z = 4.403), vocabulary (m = 14.60, Z = 4.388), and sentence mechanic (m = 8.60, Z = 4.432) as the least affected writing component.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for writing components in the flipped instruction

Post-test mean score (m = 95.28, SD = 3.84) of writing performance in the flipped-instructed group outnumbered its counterpart in the pre-test (m = 45.64, SD = 7.92). It shows that audio-visual feedback which was used as a treatment in the flipped-instructed group improved the writing performance of the participants. To ensure if this difference is statistically significant, Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was conducted. The results showed that Sig. level for the posttest-pretest differences is .000 which is lower than .05 P < .05, Z = 4.376). It depicts a significant difference between post-test/pre-test mean scores. Therefore, it can be concluded that audio-visual feedback significantly affected the writing performance of the flipped-instructed group.

4.2. The second research question

Does audio-visual feedback affect students’ writing components and writing performance in traditional instruction?

As shown in , post-test mean scores of all the writing components in the traditional-instructed group outnumbered the same group in the pre-test. It shows that audio-visual feedback which was used as a treatment in this group improved the writing components of the participants. Moreover, the post-test mean scores varied across different writing components that show audio-visual feedback did not equally affect different writing components. To see if these differences are statistically significant, Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was conducted. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test showed that Sig. level for the posttest-pretest differences for all components is lower than .05. It depicts a significant difference between mean scores of different writing components. Therefore, it can be concluded that audio-visual feedback significantly affected all the writing components in the traditional-instructed group while content (m = 15.22, z = 3.347, P = .001) and organization (m = 15.22, z = 3.425, P = .001) were affected by audio-visual feedback more than other components; they followed, respectively, by language use (m = 14.63, z = 2.293, P = .022), vocabulary (m = 10.31, z = 3.870, P = .000) and sentence mechanic (m = 7.09, SD = 3.351, P = .001) as the least frequently affected writing component.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics for writing components in the traditional instruction

Post-test mean score (m = 62.50, SD = 9.20) of writing performance in the traditional group outnumbered its counterpart in the pre-test (m = 48.31, SD = 6.57). It shows that audio-visual feedback, which was used as a treatment in the traditional group, improved the writing components of the participants. To ensure if this difference is statistically significant, Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was conducted. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test showed that Sig. level for the posttest-pretest differences is .000 which is lower than .05 (z = 3.702). It depicts a significant difference between post-test/pre-test mean scores. Therefore, it can be concluded that audio-visual feedback significantly affected students’ writing performance in the traditional group.

4.3. The third research question

Is there any significant difference between the writing components and writing performance of students in flipped and traditional instruction after receiving audio-visual feedback?

According to , Asymp. Sig. for all the writing components is greater than .05; therefore, it can be concluded that there is no significant difference between pre-tests of both traditional and flipped groups in terms of different writing components. Therefore, it was not required to control the effect of pre-tests or compute the difference between post-test and pretest mean scores. For this reason, the analysis could be done directly between the post-test scores.

Table 5. Mann–Whitney U-test for pre-test mean score of different writing components between flipped and traditional instruction

As depicted in , post-test mean scores of all-writing components in the flipped-instructed group are greater than their counterparts in the traditionally instructed group. It shows that audio-visual feedback was more effective in improving writing components when combined with the flipped instruction provided that this difference is confirmed to be statistically significant. To ensure the differences between the two groups are statistically significant, the Mann-Whitney U test was conducted.

Table 6. Comparison between post-test mean scores of different writing components in traditional and flipped instruction

The significance value of all-writing components was smaller than .05 which shows the difference between post-test mean scores of both groups are statistically significant including content (P = .000, Z = 6.003), organization (p = .000, Z = 5.980), vocabulary (P = .000, Z = 5.630), language use (P = .000, Z = 5.675), and sentence mechanic (P = .000, Z = 4.714). Therefore, our assumption stating that using audio-visual feedback in the flipped instruction would be more effective for improving students’ writing components in comparison with traditional instruction has been confirmed.

The post-test mean score of students’ writing performance for the flipped instruction was equal to 95.28, while the relevant mean score for the traditional instruction was found to be 62.50. It shows that audio-visual feedback has a more positive effect in improving the writing performance when it is combined with the flipped instruction.

5. Discussion

The result of the first research question revealed that post-test mean scores of all the writing components in the flipped-instructed group outnumbered their counterparts in the pre-test. Indeed, audio-visual feedback used as a treatment in this group improved the writing components of the participants. This result is consistent with the finding of Halwani (Citation2017) who reported that learners’ reading and writing improved when instructors used audio-visual aids to help the learners grasp the issue and become interactive in the classroom with no fear of having problems due to shyness. This is in line with the findings of Daniel (Citation2013) who talked about the benefits of applying audio-visual aids in teaching English among students. It provides interest and motivation for learning; it saves time and makes learning English easy while it assists in drawing students’ attention towards the lesson.

The effect of audio-visual feedback on five basic components of writing, namely, content, organization, vocabulary, language use, and sentence mechanics is remarkable in this study. The most affected component in this approach was organization followed by content, language use, vocabulary, and sentence mechanics, respectively. It can be concluded that the instructor’s comments on the organization component were richer and more efficient. Moreover, it can be inferred that the impact of sentence mechanics relating to the rules of the written language, such as capitalization, punctuation, and spelling as less explanatory issues did not attract students’ attention greatly. The numerous editing practices performed by the students in the flipped instruction classrooms might have also enhanced students’ self-monitoring skills, that is why content and organization were greatly affected in this type of instruction. In this regard, Cresswell (Citation2000) asserted that self-assessment practice could engage learners in an evaluation process and encourage responsibility, which can eventually lead to fewer content and organization errors in their final product.

This result also echoes the findings of the previous studies, which investigated the effectiveness of audio-visual feedback. For example, according to Sugar et al. (Citation2010), screencasts or audio-visual feedbacks permit instructors to model behaviors and activities and allow students to review the contents multiple times at their convenience to be able to improve their writing performance.

As for the second research question: Does audio-visual feedback affect students’ writing components and writing performance in traditional instruction? the results indicated that post-test mean scores of all the writing components in the traditionally instructed group outnumbered their counterparts in the pre-test. It shows that audio-visual feedback which was used as a treatment in this group improved the writing components of the participants.

Regardless of modes of instruction, these results are congruent with other scholars like Donovan and Loch (Citation2013), who found that using technology in real-time to create feedback helps students adjust their misconceptions especially in the area of writing within larger classrooms. This allows the tutors to provide more intense elaboration on different components for those learners who require additional scaffolding and support. Attali (Citation2015) also supports multiple-try feedback. This mode of feedback is formative, which allows the students multiple tries to answer questions through a delivery method used via technological developments of today’s programs. As a result, the learners can review their work and find any misinterpretations they have while still learning the proper concepts via technologically delivered lessons and feedback. One main aspect of Attali’s (Citation2015) study reveals how learners can remember and perform the same concepts several days after a given evaluation.

Moreover, the post-test mean scores varied between different writing components, which shows that audio-visual feedback did not equally affect different writing components. Audio-visual feedback significantly affected all the writing components in the traditionally instructed group while content and organization were mostly affected followed by language use, vocabulary. Sentence mechanic was identified as the least frequently affected writing component. This might be attributed to the fact that the features like content and organization were the focus of the teacher-made videos. Moreover, it can be inferred that the impact of sentence mechanics such as capitalization, punctuation, and spelling as less explanatory issues have not attracted students’ attention greatly. Like students in Davis and McGrail (Citation2009), students in the current research might have made revisions at the higher-order concerns rather than surface or lower-order revisions. The results also depicted that the post-test mean score of writing performance in the traditional group outnumbered the scores in the pre-test. It shows that audio-visual feedback, which was used as a treatment in the traditional group, improved the writing components of the participants.

Regardless of the mode of instruction, another study, which supports this result is that of Hyde (Citation2013), who demonstrated that another benefit of the audio-visual mode of feedback was that it could be available on any device that had an Internet connection. This meant that students did not have to make a journey into the university or school to obtain their feedback. The results of Hyde’s (Citation2013) research were hopeful. After the first adjustment period, scripts were much quicker to mark, and comments were more detailed and personalized. Their opinions about this mode of feedback to improve learners’ performance were found to be positive. Drawbacks were related to the difficulties in accessing the feedback file; therefore, she recommended a more powerful version of the applied software (Jing), which does allow editing and has a longer recording time per draft that would remove the problems she faced in delivering feedback. Interestingly, her proposed software for audio-visual feedback, Snagit, was applied in this study.

The third research question asked: Is there any significant difference between the writing components and the writing performance of students in flipped and traditional instruction after receiving audio-visual feedback? Based on the results, post-test mean scores of all the writing components in the flipped-instructed group were greater than their counterparts in the traditionally instructed group. It shows that audio-visual feedback was more effective in improving students’ writing components when combined with the flipped instruction. One obvious reason for such a finding is that within the traditional classroom, students did not have any access to their writing instructor’s explanations and instructions directly at home. Concerning the context of the revision process and the possibility of watching the teacher-made videos as well as teacher-made feedbacks, in this study, the experimental group who received audio-visual feedback and flipped instruction outperformed the group whose members were the receivers of audio-visual feedback but were traditionally instructed. Although there are no similar studies to compare our results with, Thai et al. (Citation2017) report that one of the best advantages of applying technology is to free up teachers’ time to allow them to provide more individualized feedback to students in innovative ways such as working through students’ problems individually, moving the cursor over the contents on the screen, and highlighting the key elements, all combined with the audio commentary. This, in return, can make a bridge between what is usually disconnected, that is feedback and revision.

6. Conclusion

The audio-visual feedback in this study was efficient in improving students’ writing skills. Indeed, the effect of hearing the teacher’s comments and seeing the written task simultaneously seems to have a great positive impact on understanding and developing students’ writing skills.

Furthermore, in this mode of feedback, the instructor had more chances for delivering clear and comprehensive feedback through mentioning examples and sharing useful links for further guidance and could praise the positive points of the writing as well. These qualities lead to a better comprehension of the weaknesses and strengths of each writing and finally, they could motivate students in learning and correcting the errors in their further assignments. According to Lunt and Curran (Citation2010), when audio-visual feedback is provided, students know exactly which part of the issue is being discussed. This makes the feedback far more in-depth and individualized compared to the paper-based feedback system. We also came to the conclusion that audio-visual feedback affected content and organization more than the other components in both flipped and traditionally instructed classrooms, and sentence mechanics were affected the least irrespective of the mode of instruction perhaps because of its explanatory nature.

Pedagogically, this study could pave the way for writing instructors and students; they can apply innovative procedures in teaching and in delivering feedbacks that are both time and cost-saving. However, the provision of audio-visual feedback needs to be considered in teacher-training courses; so that, teachers, especially writing instructors should receive training on how to provide the best possible feedback using the latest technologies.

7. Limitations and recommendations

Although our writing class size in this research was small, which might be considered as one of the limitations of this study, some scholars believe that it can have a significant influence on classroom outcomes. As stated by Schmidt et al. (Citation2015), class size and lectures can have an important role in the impact of flipped classroom outcomes; that is to say, the smaller class size could lead to more effective activities and better performance. However, we suggest that future studies increase the sample size to see if they will obtain the same results.

Furthermore, since this study was quantitative in nature, future researchers are suggested to expand this study by employing both quantitative and qualitative instruments to collect data to add more depth to the findings.

Finally, students’ preferences in receiving the type of feedback should be considered for further analysis because their preference for one form of feedback over another may show some other patterns in their writing and revision processes that may be worth considering in future studies. Since the study’s focus was on medical students, it is also recommended to take into account other disciplines and majors in higher education to see if they will obtain the same results.

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations have been taken into consideration, and permission was taken from students and lecturers to assure that the results will be used only for research purposes and will remain completely confidential. The necessary permission was taken from the officials of the department of English language, and this research was conducted with the full consent of all the participants who were involved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ehsan Hadipourfard

Sepideh Nourinezhad is a Ph.D. candidate at Azad University of Shiraz, Iran. Her research interests include learning styles, translation, and feedback.

Ehsan Hadipourfard is an assistant professor of TEFL in the English Department of Shiraz Azad University. He has presented a multitude of papers at international conferences and has published several papers. His main research interests are language learning assessment, online learning, and teaching English as a foreign language.

Mohammad Bavali is an assistant professor of TEFL in the English Department of Shiraz Azad University. He has presented a multitude of papers at international conferences and has published several papers. His main research interests are language learning strategies, learner autonomy, and online learning.

References

- Abeysekera, L., & Dawson, P. (2015). Motivation and cognitive load in the flipped classroom: Definition, rationale and a call for research. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.934336

- Ali, A. D. (2016). Effectiveness of using screencast feedback on EFL students’ writing and perception. English Language Teaching, 9(8), 106–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v9n8p106

- AlJaser, A. (2017). Effectiveness of using flipped classroom strategy in academic achievement and self-efficacy among education students of Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University. Canadian Center of Science and Education, 10(14), 67–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n4p67

- Attali, Y. (2015). Effects of multiple-try feedback and question type during mathematics problem solving on performance in similar problems. Computers & Education, 86(2015), 260–267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.08.011

- Barroga, E., & Mitoma, H. (2019). Improving scientific writing skills and publishing capacity by developing university-based editing system and writing programs. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 34(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e9

- Bartlett, A. (1994). The implications of whole language for classroom management. Action in Teacher Education, 16(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.1994.10463189

- Berrett, D. (2012). How ‘Flipping’ the classroom can improve the traditional; lecture. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 12(19), 1–3. https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-flipping-the-classroom-can-improve-the-traditional-lecture/

- Black, P. J., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

- Borup, J., West, R. E., & Thomas, R. (2015). The impact of text versus video communication on instructor feedback in blended courses. Educational Technology Research and Development, 63(2), 161–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-015-9367-8

- Brick, B., & Holmes, J. (2014). Using screen capture for student feedback. Paper presented at the eleventh international conference cognition and exploratory learning in digital agePorto, PT. http://www.iadis.org

- Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Sage.

- Cavaleri, M., Satomi, K., Bruno, D., & Clare, P. (2019). How recorded audio-visual feedback can improve academic language support. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 16(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.53761/1.16.4.6

- Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles of good practice in undergraduate education: Faculty inventory. American Association for Higher Education.

- Coffman, M. L. (2011). The impacts of web-enhanced versus traditional writing instruction. Union University, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1–136. https://search.proquest.com/openview/fe3f80f0c4a9e087ecf60caab48e36a8/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Cresswell, A. (2000). Self-monitoring in student writing: Developing learner responsibility. ELT Journal, 54(3), 235–244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/54.3.235

- Daniel, J. (2013). Audio-visual aids in teaching of English. International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology, 2(8), 3811–3814.

- Davis, A., & McGrail, E. (2009). “Proof-Revising” with podcasting: Keeping readers in mind as students listen to and rethink their writing. The Reading Teacher, 62(6), 522–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.62.6.6

- DeVoss, D. N., Eidman-Aadahl, E., & Hicks, T. (2010). Because digital writing matters: Improving student writing in online and multimedia environments. John Wiley & Sons.

- Donovan, D., & Loch, B. (2013). Closing the feedback loop: Engaging students in large first-year mathematics test revision sessions using pen-enabled screens. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 44(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2012.678898

- Ekmekçi, E. (2018). Exploring Turkish EFL students’ writing anxiety. Matrix Int Online J, 18(1), 158–175.

- Ellman, M. S., & Schwartz, M. L. (2016). Article commentary: Online learning tools as supplements for basic and clinical science education. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 3, 109–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4137/JMecd.S18933

- Elola, I., & Oskoz, A. (2016). Supporting second language writing using multimodal feedback. Foreign Language Annals, 49(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12183

- Ferrer, G., & García-Barrera, A. (2014). Evaluation of the effectiveness of flipped classroom videos. In 8th international technology, education and development conference (pp. 2608–2613). Valencia, Spain.

- Grabe, W., & Kaplan, R. B. (2014). Theory and practice of writing: An applied linguistic perspective. Routledge.

- Halwani, N. (2017). Visual aids and multimedia in second language acquisition. English Language Teaching, 10(6), 1916–4750. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n6p53

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

- Henderson, M., & Phillips, M. (2014). Technology enhanced feedback on assessment. Paper presented at the 26th australian computers in educational conference, Adelaide, South Australia. http://acec2014.acce.edu.au/session/technology-enhanced-feedback-assessment

- Hepplestone, S., Holden, G., Irwin, B., Parkin, H., & Thorpe, L. (2011). Using technology to encourage student engagement with feedback: A Literature Review. Research in Learning Technology, 19(2), 117–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v19i2.10347

- Hyde, E. (2013). Talking results: Trialing audio-visual feedback method for resubmissions. Innovative Practice in Higher Education, 1(3). http://journals.staffs.ac.uk/index.php/ipihe/article/view/37

- Jacobs, H. L., Zinkgraf, S. A., Wormuth, D. R., Hartfiel, V. F., & Hughey, J. B. (1981). Testing ESL composition: A practical approach. Newbury House. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3588173

- Jony, S. (2016). Student centered instruction for interactive and effective teaching learning: Perceptions of teachers in Bangladesh. International Journal of Advanced Research in Education & Technology, 3(3), 172–178. http://ijaret.com/wpcontent/themes/felicity/issues/vol3issue3/mdsolaiman.pdf

- Kafipour, R., Mahmoudi, E., Khojasteh, L., & Khajavi, Y. (2018). The effect of task-based language teaching on analytic writing in EFL classrooms. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1496627

- Kashefian-Naeeini, S., & Sheikhnezami-Naeini, Z. (2020). Communication skills among school masters of different gender in Shiraz, Iran. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(2), 1607–1611. http://sersc.org/journals/index.php/IJAST/article/view/3405/2350

- Kerr, J., Dudau, A., Deeley, S., Kominis, G., & Song, Y. (2016). Audio-Visual Feedback: Student attainment and student and staff perceptions. University of Glasgow. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/119844/7/119844.pdf

- Khojasteh, L., Shokrpour, N., & Afrasiabi, M. (2016). The relationship between writing self-efficacy and writing performance of Iranian EFL students. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 5(4), 29–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.5n.4p.29

- Lee, I. (2008). Ten mismatches between teachers‘ beliefs and written feedback practice. ELT Journal, 63(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn010

- Lunt, T., & Curran, J. (2010). ‘Are you listening please?’ The advantages of electronic audio feedback compared to written feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(7), 759–769. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930902977772

- Mayer, R. E. (2005). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 31–48). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511816819.004

- Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511811678

- McCarthey, S. J., & Ro, E. (2011). Approaches to writing instruction. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 6(4), 273–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2011.604902

- McCarthy, J. (2015). Evaluating written, audio, and video feedback in higher education summative assessment tasks. Issues in Educational Research, 25(2), 153–169. http://www.iier.org.au/iier25/mccarthy.html

- Mousavi, H. S., & Kashefian-Naeeini, S. (2011). Academic writing problems of Iranian post-graduate students at national university of Malaysia (UKM). European Journal of Social Sciences, 23(4), 581–591. http://www.eurojournals.com/EJSS_23_4_08.pdfs

- Noordin, N., & Khojasteh, L. (2021). The effects of electronic feedback on medical university students’ writing performance. International Journal of Higher Education, 10(4), 124–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v10n4p124

- Nourinezhad, S., Kashefian-Naeeini, S., & Tarnopolsky, O. (2020). Iranian EFL university learners and lecturers’ attitude towards translation as a tool in reading comprehension considering background variables of age, major and years of experience. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1746104

- Nueuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Sage.

- Perkoski, R. (2017). The impact of multimedia feedback on student perceptions: video screencast with audio compared to text-based email. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh. ( Unpublished). http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/31759/

- Phuket, R. N., & Othman, N. B. (2015). Understanding EFL students’ errors in writing. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(32), 99–106.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2012). Research methods for business students (6th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Schmidt, H. G., Wagener, S. L., Smeets, G. A. C. M., Keemink, L. M., & Van Der Molen, H. T. (2015). On the use and misuse of lectures in higher education. Health Professions Education, 1(1), 12–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpe.2015.11.010

- Shahini, G. H. (1988). A needs assessment for EFL courses at Shiraz University ( Unpublished master’s thesis). Shiraz University.

- Shahsavar, Z., & Asil, M. (2019). Diagnosing English learners’ writing skills: A cognitive diagnostic modeling study. Cogent Education, 6(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1608007

- Sugar, W., Brown, A., & Luterbach, K. (2010). Examining the anatomy of a screencast: Uncovering common elements and instructional strategies. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 11(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v11i3.851

- Tajalizadeh Khob, M., & Rabi, A. (2014). Meaning-focused audiovisual feedback and EFL writing motivation. Journal of Language and Translation, 4(2), 61–70.

- Thai, N., De Wever, B., & Valke, M. (2017). The impact of a flipped classroom design on learning performance in higher education: Looking for the best “blend” of lectures and guiding questions with feedback. Computers & Education, 107, 113–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.01.003

- Thompson, R., & Lee, M. J. (2012). Talking with students through screencasting: Experimentations with video feedback to improve student learning. The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, 1(1), 17–26.

- Tidwell, D. L., & Steele, J. L. (1995, December I teach what I know: An examination of teachers’ beliefs about whole language. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the national reading conference, San Antonio, TX. ( ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 374 391) https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/660688

- Watcharapunyawong, S., & Usaha, S. (2013). Thai EFL students’ writing errors in different text types: The interference of the first language. English Language Teaching, 6(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n1p67

- West, J., & Turner, W. (2016). Enhancing the assessment experience: Improving student perceptions, engagement and understanding using online video feedback. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 53(4), 400–410. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2014.1003954

- Wiliam, D. (2010). The role of formative assessment in effective learning environments. The nature of learning: Using research to inspire practice. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264086487-en

- Wilson, S. G. (2013). The flipped class: A method to address the challenges of an undergraduate statistics course. Teaching of Psychology, 40(3), 193–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628313487461

- Zheng, M., Chu, C., Wu, Y., & Gou, W. (2018). The mapping of on-line learning to flipped classroom: Small private online course. Sustainability, 10(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030748

Appendix A.

The Analytic Rubric (Jacobs et al., Citation1981)

Appendix B.

Snagit: Screen Capture & Video Recording Software (2019, January 21). Retrieved from https://www.techsmith.com/screen-capture.html

Intus Art Creative Pen & Touch Tablet (2019, January 21). Retrieved from https://www.wacom.com/en/products/pen-tablets/intuos-art