ABSTRACT

This paper revisited the issue of transfer in an unexplored context: the transition from instruction-based writing to the bachelor’s theses by English-major students in one university in China. To explore the extent to which the writing instruction prepared the students for thesis writing practice, we created two corpora of student writing: 591 assignments produced by 40 students in 3 writing-related courses offered in the curriculum and 40 bachelor’s theses produced between 2014–2018. Based on the taxonomy of elemental genres in the Systemic Functional Linguistics, we compared the genre distribution in the two corpora via log-likelihood tests. Results revealed that two patterns of continuity and two patterns of discontinuity existed in the students’ literacy journey. Also, framed within the theory of adaptive transfer, a focus-group interview was conducted with four thesis writers in an attempt to trace their transfer of rhetorical knowledge between the two rhetorical contexts. Findings demonstrated that the students consciously reused and reshaped a pool of rhetorical knowledge acquired from the writing courses to navigate the complex task of thesis writing. This paper then concludes with implications for L2 writing research, curriculum, and pedagogy.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This article explores the issue of transfer in the literacy journey of Chinese undergraduate ELF learners. Adopting a mixed method of corpus analysis and focus group interview, the study diagnosed the match and mismatch between the preparatory EAP writing instruction and the culminating bachelor’s theses by Chinese ELF learners and reported interesting findings of how the student writers adaptively transferred their genre knowledge across the two rhetorical contexts. The findings of this study provide deep insights into whether the EAP writing instruction being offered is sufficient and how the students transfer what they learn in EAP writing courses to other academic contexts. The results could yield important implications for curriculum and pedagogy in L2 EAP writing contexts that aim to teach for transfer.

1. Introduction

The concept of transfer, commonly defined as the application of prior knowledge from one situation to another (e.g., Foertsch, Citation1995; Perkins & Salomon, Citation1994), has a long and deep history in education and educational psychology (Detterman, Citation1993). For more than two decades, it has filtered through many of the discussions related to first language (L1) compositional studies, second language (L2) writing, and genre-based teaching and learning (e.g., Fishman & Reiff, Citation2008, Citation2011; James, Citation2014; Wardle, Citation2007, Citation2009). This concept carries particular implications for English-for-Academic-Purposes (EAP) as these courses aim to develop students’ writing abilities in various academic contexts (Hill et al., Citation2020). A capable academic writer, therefore, should be one who is able to flexibly leverage and transfer their repertoire of rhetorical knowledge in response to the varied situations. In L2 EAP writing, in particular, the goal of our pedagogical efforts is not to enable students to succeed in a single course alone, but rather to generate a solid knowledge base that they can constantly refer back to in future rhetorical situations.

1.1. Existing research on transfer in academic writing

Transfer research in diverse EAP writing contexts, most notably in the First-Year-Composition (FYC) programs in the educational context of the United States, stresses that genre is a powerful and often underappreciated cue for acts of transfer and that the development of genre awareness play an integral role in facilitating students’ long-term writing growth (Fishman & Reiff, Citation2008, Citation2011; Nowacek, Citation2011; Wardle, Citation2007, Citation2009). These studies were primarily conducted in English-L1 contexts. Given that L2 writers learning English as an additional language engage in EAP writing in quite different environments and thus wrestle with different obstacles, a great deal of scholarship was devoted to understanding how transfer occurs among L2 academic writers—and in their genre learning in particular.

Studies on L2 students’ transfer in EAP writing can be divided into two main strands, differing in their contexts and methodological approaches. One strand of research treated transfer as the application of a set of learning outcomes. For instance, both James (Citation2009, Citation2010) and Zarei and Rahimi (Citation2014) discovered that a wide variety of learning outcomes from their EAP writing courses did transfer to writing tasks in other academic courses, but either in constrained ways or with varying frequencies depending on the task types and disciplines. In a similar vein, Hill et al. (Citation2020) investigated the transfer of learning outcomes in an EAP course taken by undergraduate engineering students at a Singapore University. They found that strong transfer occurred in most of the learning outcomes within the EAP course, but the transfer of half of the learning outcomes was not sustained over the year to the students’ engineering course assignments. These studies provided insightful answers to the questions of what specific learning outcomes were transferred and to what extent they were transferred, but one obvious limitation of these studies is that the complex act of transfer was simplistically narrowed to the repetition of a set of discrete learning outcomes without considering the dynamics and fluidity of contexts. If we were to agree that a range of contextual factors may influence transfer (Hill et al., Citation2020), and that no two writing contexts in the world are exactly the same, it would be amiss not to account for how such learning outcomes are, or can be, adapted, transformed, and repurposed, when they are leveraged in the new context.

Another line of research plumbed students’ developing genre awareness when navigating the challenges in EAP writing courses and those inherent in new writing situations (Cheng, Citation2007, Citation2008; DasBender, Citation2016; Shrestha, Citation2017). Cheng (Citation2007, Citation2008), for example, studied genre learning in an EAP writing course in a large American university. As teacher and researcher, he traced a focal student—Fengchen (a pseudonym), a Chinese-L1 graduate student in electrical engineering, and found that the student demonstrated a growing genre awareness with an ability to transfer, or recontextualise, such an awareness and related generic features into his own writing. DasBender (Citation2016) reported two cases of L2 students—Shiyu and Ming (pseudonyms, both are native Chinese speakers), within the context of college-level writing courses. Drawing on data from one brief literacy history narrative and responses to three focused reflective writing prompts, this study explored the difficulties the two students encountered in the courses and their attempts to overcome them, which, as DasBender (Citation2016) contended, offered an intimate glimpse into their processes of transfer and growth as a writer.

To recapitulate, many of the studies on L2 writing transfer have sought to understand transfer as something that either occurs or not, or merely as the application of an inert set of writing skills between similar tasks. What remains less discussed is the question of how the genre learning in prior EAP writing courses readily prepare L2 students for new and potentially unfamiliar writing contexts. More significantly, the recontextualisation of the learnt genres, that is, how these genres are and can be adapted into the new rhetorical context, needs to be further qualified. The present study, therefore, attempts to undertake this path of inquiry by looking at the literacy journey of English-major undergraduate students in China through the theoretical lenses of genre in Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) and adaptive transfer (see below in sections 2.1 & 2.2, respectively).

1.2. The context: “Literacy journey” of Chinese English-major students

Compared to the larger population of non-English majors in the Chinese tertiary education, the English-major students experience a unique “literacy journey” which is marked by a transition between two critical rhetorical phases. We borrowed the metaphor of “literacy journey” from Wingate (Citation2012) as it describes “a process with a known starting point and destination, but an unknown route” (p. 1). The starting point of this journey is several EAP writing courses that the students take in the first two or three years in university. In keeping with the English Teaching Syllabus for Tertiary English Majors (a national syllabus governing the English-major education at the undergraduate level) (Teaching Advisory Committee for Tertiary English Majors, Citation2000), students receive classroom-based instruction on general academic writing skills in these courses and are regularly assigned to write “short essays” in some basic, broad types of genres with an average length of 300–400 words.

The destination of the journey is a 3000- to 5000-word long thesis composed in the final year of study. The main function of a bachelor’s thesis is to familiarise the students with disciplinary knowledge and to engage with empirical research addressing a meaningful topic in relevant sub-fields, namely, translation studies, cultural studies, literary studies, and applied linguistics. As an essential form of assessment, a bachelor’s thesis is produced under the guidance of a thesis advisor and then evaluated by a committee of three or four thesis examiners.

The bachelor’s thesis is not only disproportionately longer, but intellectually more demanding and structurally more complex, than the “short essays” in the preparatory writing courses. Thus, the move across the two distinct but ultimately related rhetorical contexts marks a critical leap for these uninitiated writers. To date, however, little is known about whether and how much the EAP writing courses afford the students a smooth transition toward the destination. The unknown route of the journey remains, more specifically, the way the genre learning in the prior writing courses links up with the generic demands in the bachelor’s theses and the way the student writers transfer their rhetorical knowledge about the learnt genres into their bachelor’s theses.

1.3. Research questions

The present study posits the following two research questions:

To what extent does the genre learning by Chinese English-major students in the prior EAP writing courses connect with, or disconnect from, the generic demands in their bachelor’s theses?

How do the students adaptively transfer, if at all, the rhetorical knowledge learnt from the instructional settings to suit the new context of bachelor’s thesis writing?

Before diving into the methodological waters, we shall first lay out the two theoretical frameworks in Section 2, i.e., the genre theory in SFL tradition and the theory of adaptive transfer, that jointly underpin the subsequent analysis and discussions.

2. Theoretical frameworks

2.1. Genre in systemic functional linguistics

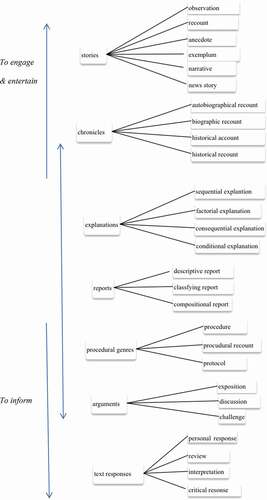

In the Chinese mainland, where a large population of writing instructors are increasingly called upon to provide students with genre-oriented writing support (Li et al., Citation2020), the SFL approach, with its basis in Michael Halliday’s theory of language as a semiotic system with contrasting options for making meaning (Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation2014), has always been the most influential and the most widely applied (Huang, Citation2002). As a concept located in the context of culture, genre is defined as “the system of staged goal-oriented social processes through which social subjects in a given culture live their lives” (Martin, Citation1997, p. 13). Through large-scale textual analysis in infant, primary and secondary education in Australia, theorists in this school distinguish varieties of elemental genres grouped into seven “genre families”: namely, stories, chronicles, reports, explanations, procedures, arguments, and text responses (e.g., Martin & Rose, Citation2008; Rose, Citation2017).

As SFL genre research expands into tertiary education and workplaces (e.g., Coffin & Donohue, Citation2014; Dreyfus et al., Citation2015; Jordens & Little, Citation2004; Jordens et al., Citation2001; Nesi & Gardner, Citation2012; Szenes, Citation2017), it is argued that writers advancing on academic/professional ladders need to move from controlling elemental genres to writing longer and more sophisticated texts (Szenes, Citation2017). Such longer texts are termed as macrogenres, referring to structurally large-scale texts that combine more than one elemental genre to accomplish complex goals (Martin, Citation2002).

The short essays that Chinese English-major students learn to write in the preparatory writing courses basically involve particular elemental genres. The bachelor’s thesis, by contrast, typically constitutes a macrogenre, encompassing a complex macrostructure with separate sections under specific headings where varieties of elemental genres are jointly constructed, each having distinct social purposes, rationales, language, and contents in the disciplinary areas (Nesi & Gardner, Citation2012; Zhang & Pramoolsook, Citation2019). Therefore, the transition from the elemental genres in the writing classrooms to the macrogenre of bachelor’s theses poses a big hurdle in the students’ overall development as academic and disciplinary writers.

2.2. Constructs of transfer and the theory of adaptive transfer

The notion of transfer has triggered a deeply conflicted literature, resulting in varied conceptualisations. Perkins and Salomon (Citation1994) distinguish near transfer which occurs between similar contexts, and far transfer occurring between contexts that, on appearance, seem remote and alien to one another. Furthermore, they recognise two distinct mechanisms to explain how transfer occurs—low-road transfer versus high-road transfer (Perkins & Salomon, Citation1988; see also James, Citation2014). Transfer occurring on the low road involves “the automatic triggering of well-practiced routines” (Perkins & Salomon, Citation1988, p. 25) when stimulus conditions in the transfer context are sufficiently similar to those in a prior context of learning, a reflexive process figuring in near transfer. Transfer on the high road, in contrast, depends on “mindful abstraction from the context of learning or application and a deliberate search for connections” (Perkins & Salomon, Citation1994, p. 6459), a relatively reflective act that often leads to far transfer.

Examining transfer scholarship in L2 writing, DePalma and Ringer (Citation2011) criticised the previous discussions of transfer as too narrowly conceptualised, constraining the concept itself to the application of a writing skill, intact and in its original form, from one context to another, thus reflecting a “static theory of L2 writing” (Matsuda, Citation1997). In response, they proposed the construct of adaptive transfer, defining it as “the conscious or intuitive process of applying or reshaping learned writing knowledge to negotiate new and potentially unfamiliar writing situations” (p. 135). In promoting adaptive transfer as a “dynamic, idiosyncratic, cross-contextual, rhetorical, multilingual, and transformative” conceptual framework, DePalma and Ringer (Citation2011) emphasised how such a conception epitomises a “dynamic model of writing” (Matsuda, Citation1997) that values the agency of L2 writers.

Methodologically, DePalma and Ringer (Citation2011) suggested designing multi-layered methodologies that combine text/genre analysis, interviews, and observations, and recommended focus group interview as a particularly useful research method to explore adaptive transfer. In this study, we operationalise the concept of adaptive transfer as the utilisation of rhetorical knowledge of genres in new ways, from new perspectives, and with different contents. To pursue our two research questions, we shall first compile two corpora of student writing in the two rhetorical phases from one university in China, analysing and comparing their coverage and distribution of elemental genres, and then, via a focus group interview, plumb the student-writer perceptions and reported behaviours in adaptively transferring the learnt genres.

3. This study

3.1. Research site

This study was carried out in the English Department in a public university in the Southwestern China. Students in this Department take three writing-related courses, i.e., English Writing I, English Writing II, and Academic Writing in the third, fourth and sixth semesters in their four-year undergraduate study. In the first two 14-week courses, students generally learn and practice writing skills across four broad types of writing, including narration, description, exposition, argumentation, and some practical genres like emails or résumés. As part of the course contents, the instructors regularly assign the students to independently compose “short essays” of an average length of 300–400 words realizing certain elemental genres. Then, in the 10-week Academic Writing course, the students are introduced to MLA writing conventions in preparation for the bachelor’s thesis writing. The lessons in this course are mostly delivered in the form of lectures, with fewer writing assignments after class. In the final year of study, through a number of conferences, drafts, and revisions with a thesis advisor, each student produces a bachelor’s thesis at a minimum length of 4000 words which constitutes a macrogenre.

3.2. Data collection

Adopting a mixed-methods approach, this study collected two types of data. First, to address RQ1, two corpora of student writing were compiled, namely, a corpus of instruction-based writing produced by students in the three writing-related courses and a corpus of bachelor’s theses produced by English-major students from the same university between 2014 and 2018. The two corpora were subject to genre analysis following the SFL approach in order to diagnose their match and mismatch in terms of genre distribution. Also, framed within the theory of adaptive transfer, we collected focus-group interview data from four focal thesis writers in an attempt to trace their transfer of rhetorical knowledge between the two rhetorical contexts. The data collection procedures will be detailed below.

3.2.1. Corpus of bachelor’s theses (BT Corpus)

To investigate the genre distribution in bachelor’s theses, we created a small corpus comprising 40 bachelor’s theses produced by undergraduates in this Department from 2014 to 2018. Eighty-five (out of a full mark of 100) was set as the cut-off point—a benchmark for quality theses in the Department, reflecting the preferable generic patterning of this macrogenre. We chose the “elite” theses only, because they better represent the ideal performance in this academic macrogenre, that is, what the university expects to teach and prepare the students for. Out of the 336 theses produced during this period, 63 (18.8%) met the criterion. We then selected 40 theses via quota sampling techniques, ensuring that the breakdown of theses in the four subfields was proportionate to that in the original pool and an almost equal number of theses were selected from each year. Finally, auxiliary texts such as the cover page, abstract, acknowledgement, bibliography, and appendices were discarded; that is, only the essential body texts were retained in the final corpus.

3.2.2. Corpus of instruction-based writing (IW Corpus)

To trace the students’ prior genre learning experiences in the three EAP writing courses, we followed 40 students from each course and created a corpus by collecting their full sets of instructor-set writing assignments. Constrained by the timeframe of this research, a cross-sectional approach, instead of a longitudinal one, was adopted. In keeping with the university’s academic calendar, the two sub-corpora for Academic Writing and English Writing II were compiled concurrently in Spring 2018 from students enrolled into the university in 2015 and 2016, and the sub-corpus for English Writing I was compiled in Autumn 2018 from students enrolled in 2017. On balance, the students involved in the three courses were enrolled in three consecutive academic years and thus at different levels of their study. The comparability of the student groups lies in the following aspects: first, by and large, they came from a similar background and demonstrated nearly equivalent initial English language proficiency; second, the three writing courses were taught by the same crew of instructors each academic year; third, the fundamental aspects of their teaching contents and methods remained relatively stable in the past few years. Collectively, the learning and writing experiences the three groups of students could represent the entire literacy journey of the English-major students in this university.

The selected text contributors were those acknowledged by course instructors as active and responsible participants in their classes. All of their writing assignments were positively assessed (i.e., reaching a minimum grading of 60%), ensuring that the final corpus was a truthful representation of genre engagement targeted in the three courses. Altogether, 280, 231, and 80 assignments were collected from English Writing I, English Writing II, and Academic Writing, respectively, amounting to a total of 591 assignments.

3.2.3. Focus-group interview to trace adaptive transfer

To trace the processes of adaptive transfer, focus group interview recommended by DePalma and Ringer (Citation2014) was adopted as our primary research method. At the time of the research, only students who defended their theses in 2018 were available for the interview. As students with an ability to transfer prior knowledge are general believed to have greater chances for success in meeting new rhetorical challenges (Beaufort, Citation2012), we assume that the relatively more successful, highly-motivated writers are better primed for engaging in and recognizing transfer. Therefore, we set the following three criteria in selecting interviewees: (a) their theses scored 85 or above and were selected into our BT corpus; (b) they were articulate and expressive enough to talk about their level of preparedness when undertaking the thesis writing task; and (c) they had both an awareness of and language for sharing retrospective perceptions about how they negotiate the rhetorical demands in the thesis writing by referring back to their prior learning. Ultimately, four competent thesis writers—Shirley, Joey, Alice, and Tina (all pseudonyms)—were invited to participate in the focus group.

The focus group interview, administered by the first author of this paper, was conducted in Chinese and audio-recorded with informed consent. The interview lasted about 45 mins, during which three open-end questions adapted from DePalma and Ringer (Citation2014) were asked and extensively discussed (the generic terms used in the original questions were replaced with specific ones that point directly to the two rhetorical contexts involved in the present study):

Think back on the different classes you took that included writing for significant genres. Describe your process of working through later more academically demanding task of thesis writing.

Think about the genres you learned to write in the earlier courses. In what ways have you had to reshape what you learnt about the genres to fit what you need to write in the thesis?

Think of moments when you were told (maybe by your thesis advisor or examiners) that you had made an error and done something wrong. In any of these moments, did you feel like what you had done was really a different way of writing that you felt was nonetheless valuable, effective, and/or original?

3.2.4. Data analysis

3.2.4.1. SFL-based genre analysis of the two corpora

Our analysis of the BT corpus encompasses two main steps: deconstruction and genre identification. First, the macrogenre of bachelor’s theses were deconstructed into smaller meaningful units based on explicit shift in themes and obvious boundary indicators, such as section/chapter headings and discourse markers. In total, the 40 theses were deconstructed into 776 shorter texts. Second, each of the shorter texts was assigned to a particular elemental genre in the SFL taxonomy (see Appendix), based on their primary purposes, schematic structures, and critical linguistic features.

To warrant the reliability of our genre analysis, a guest researcher with extensive experience in SFL genre research was invited to cooperate with the first author of this paper. The two coders independently analysed 30% of the corpus (12 bachelor’s theses comprising 235 shorter texts) and achieved 92.3% agreement. The residual disagreement was resolved by consulting either the original thesis writer, if available, or a third expert who was familiar with the analytical framework.

From the pilot analysis emerged one special text that did not seem to fit any of the initial coding categories. Examining its rhetorical features more closely, the two coders decided to label it as analytical explanation (see more discussion on this emerging elemental genre in Zhang & Pramoolsook, Citation2019). A new code was then added to the operating framework.

Genre analysis of the IW corpus was manually done in a similar way. There were a few cases in which the students fulfilled one writing assignment with two or three elemental genres (either as a macrogenre or simply as discrete texts). In these cases, each text was tallied separately. In total, the IW corpus produced 613 instances of elemental genres. Emails, résumés, and resignation letters, serving important personal and practical purposes in life, were grouped into a genre family named practical genres. A few assignments, containing decontextualised pattern drills to reinforce taught vocabulary or sentence patterns, with neither a controlling theme in the content nor a recognizable structure at the discourse level, were labelled as exercises—a term borrowed from Nesi and Gardner (Citation2012). The rest of the corpus was analysed based on the same set of criteria as with the BT corpus.

The labelling work of IW corpus was manually done by the first author of this paper herself. To warrant reliability, the corpus was coded twice with an interval of two weeks to ensure that the first coding had no impact on the second. The two codings demonstrated a high intra-coder consistency (94.8%). Where the two codings were inconsistent, the texts were handed over to the second author to make a final decision.

3.2.4.2. Comparison between the two corpora

Results from genre analysis of the two corpora were subject to comparison to pinpoint the connects and disconnects between the two rhetorical phases (Research Q1). Because the two corpora differed in size, statistical analysis was conducted by means of log-likelihood tests, using Paul Rayson’s log-likelihood calculator (http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/llwizard.html)—a useful gadget to compare the frequencies of linguistic items in corpora of different sizes. In our study, the frequencies of each elemental genre in the two corpora were compared in order to determine whether the differences were statistically significant. The greater the log-likelihood (LL) value, the more significant is the difference between the two frequency scores: LL ≥ 3.84 is significant at p < 0.05; LL ≥ 6.63 is significant at p < 0.01; LL ≥ 10.83 is significant at p < 0.001; and LL ≥ 15.13 is significant at p < 0.0001. Effect Size for Log Likelihood (ELL) measure (Johnston et al., Citation2006), included within Rayson’s calculator, was also implemented.

3.2.4.3. Thematic analysis of focus-group interview

The interview data were analysed thematically through three major steps. In the first step, the interview was transcribed and translated into English. As a form of member-checking, the translated transcripts were referred back to the interviewees to confirm that there was no misinterpretation. Then, we read and re-read the transcripts carefully, noting on any unit or chunks of data with significant information. DePalma and Ringer (Citation2014) have recommended three questions that researchers might ask in analysing focus group transcripts in exploring adaptive transfer. With some minor adaptations to suit the current research scenario, these questions were used to guide our on-going thematic analysis.

In describing their processes of writing the theses, what kinds of linguistic resources, rhetorical/genre knowledge, and writing experience do focus group participants discuss?

In what way do the focus group participants discuss how the earlier writing courses were able or unable to facilitate them with the thesis-writing task?

How did the focus group participants reuse or reshape prior writing/genre knowledge to suit the more challenging writing contexts?

Finally, the recurrent themes emerging from this step of open coding were compared back-and-forth and, when necessary, linked to the information gleaned from the corpus data, until they were correlated to form a nuanced understanding of the way adaptive transfer happened (Research Q2). Ultimately, we used reuse and reshaping, the two concepts lying at the heart of adaptive transfer, as the higher-level codes—the former referring to the students’ recognition of utilizing or not utilizing whole genres, and the latter to the adaptation and recontextualisation of rhetorical knowledge, which subsumes, as the lower-level codes, the appropriation of a range of writing strategies and rhetorical resources, and the reinvention of a new generic stage.

Frequent debriefing sessions were held between the two authors of this paper. As a way of cross-checking, the interview data were first analysed by the first author, and the emerging codes and themes were verified by the second author who was responsible for this study in a more supervisory capacity.

4. Transition across the two rhetorical phases: Continuity and discontinuity

To answer Research Q1, we present the respective distribution of elemental genres in the two corpora and the results from loglikelihood tests in . As the table shows, on average, the number of elemental genres employed per thesis (19.4) exceeded that performed per student in the antecedent writing assignments (15.3), indicating that, on the whole, an individual student was not given sufficient labour in the writing classrooms in the face of an increased rhetorical load in the bachelor’s thesis. As text responses were probably addressed in other reading- or literature-oriented courses and practical genres and exercises were absent from bachelor’s theses for obvious reasons, these three genre families are excluded from the subsequent discussions (indicated by dash in ). Regarding the remaining 22 elemental genres that traversed the entire trajectory of undergraduate writing, two patterns of continuity (where no significant difference was found between the two corpora) and two patterns of discontinuity (where significant differences existed) emerged. These four patterns of (dis)continuity are summarised in and will be discussed in turn.

Table 1. Comparison of the distribution of elemental genres in the two corpora

Table 2. Four patterns of (dis)continuity in the transition from instruction to practice

4.1. Limited use

Six elemental genres, i.e., exemplum, historical account, sequential explanation, conditional explanation, protocol, and discussion, had limited use in both rhetorical contexts (indicated by the size of the ellipses in , hereinafter), with only a meagre number of instances and no significant difference between the two corpora (LL<3.84). In other words, while only marginal, if not completely zero, efforts were put into learning and writing these six elemental genres in the earlier writing courses, their contribution to the macrogenre of bachelor’s theses was not substantial as well.

4.2. Extensive use

To the contrary, expositions (LL = 2.48) appeared to be the only elemental genre that was consistently in massive use in both rhetorical episodes. Probably owing to the exam-driven nature of English education in China, expositions, as one of the most high-stakes genres in many standardised tests for English proficiency, were tremendously emphasised in the writing classrooms. Relatedly, it also occupied an enormous discursive space in bachelor’s theses (see also Zhang & Pramoolsook, Citation2019), meaning that the prior efforts put in teaching and learning this genre were, in quantitative terms, worthily repaid.

4.3. Excessive preparation

On the flip side, mismatches were observed where significant differences were found to draw the two corpora apart. Seven elemental genres, namely, anecdote (LL = 22.78), observation (LL = 49.08), recount (LL = 24.54), narrative (LL = 36.44), factorial explanation (LL = 10.10), procedure (LL = 7.38), and challenge (LL = 5.41), were observably more frequent in the instructor-set assignments than in bachelor’s theses (indicated by /+/ in ). This discrepancy suggests that these elemental genres received excessive pedagogical provisions in the classrooms that hardly made their way into the bachelor’s theses. It is not our intention, at any rate, to devalue these instructional efforts, since well beyond the bachelor’s theses, there might be plenty more possibilities for these elemental genres to be useful in the students’ continued literacy development.

4.4. Inadequate preparation

As for the remaining eight elemental genres, namely, biographical recount (LL = 6.99), historical recount (LL = 18.12), consequential explanation (LL = 5.76,) analytical explanation (LL = 4.66), descriptive report (LL = 67.91), classifying report (LL = 100.14), compositional report (LL = 53.56), and procedural recount (LL = 25.62), the pedagogical support was found significantly insufficient (indicated by /–/ in ). The most striking case was reports, on which differences were found significant at p < 0.0001. This genre family, which occupied nearly half of discursive spaces in bachelor’s theses, was largely overlooked in the instructional phases; its two subtypes, i.e., classifying reports and compositional reports, in particular, were completely absent from the prior writing courses. A more astounding case was that of analytical explanations, the newly-found elemental genre from the BT corpus, which was not found in the IW corpus either. This observation has not only driven us to view analytical explanations as a case of “genre innovation” unique to the local thesis writing community (Tardy, Citation2016; Zhang & Pramoolsook, Citation2019), but also stimulated us to seek effective ways to introduce this inventive genre appropriately and fruitfully into the future writing curriculum.

So far, a conclusion can be drawn that seven elemental genres received seemingly fair treatment in the EAP writing courses that catered well to the complex rhetorical demands in bachelor’s theses, while another 15 elemental genres did not. The discontinuity between the two rhetorical worlds not only explains the sense of difficulty that the final-year students often feel when approaching bachelor’s theses, but also points to a viable route via which remedy work can be thoughtfully done to better support our students by reframing the writing-related curriculum and reallocating our pedagogical investment, if the most immediate end of EAP writing courses is, and continues to be, to assist the students with the transition into the culminating task of thesis writing.

Our Research Q2 concerns how the rhetorical knowledge learnt in writing classes leaked into bachelor’s thesis writing. The succeeding section will address this question based on findings from the focus group interview.

5. Adaptive transfer as reuse and reshaping of rhetorical knowledge

5.1. Reuse of whole genres

Following Reiff and Bawarshi (Citation2011), reuse of rhetorical knowledge was understood as the writers’ behaviours to consciously draw on (or dismiss) whole genres, regardless of the varied writing tasks. In the interview, when asked what genres they were thinking of during the process of thesis writing, the four thesis writers soon named a few recognizable genres they had learnt in the prior writing courses.

Because many of us did translation studies, we seldom used the narrative or the argumentative. (Shirley)

When writing the thesis, we relied mainly on the expository writing, supplemented by arguments. Bachelor’s theses are not all about arguments. (Joey)

The way I wrote this part was quite similar to what we did in argumentative writing, that is, introducing the topic and then going on to analyse. (Alice)

I think my Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 are descriptive, mainly integrating insights from previous scholars. Chapter 3 is relatively more important and involves more arguments. (Tina)

Reiff and Bawarshi (Citation2011) defined students exhibiting and reporting such a ready use of whole genres as “boundary guarders” who tended to engage in low-road transfer (Perkins & Salomon, Citation1988). In our case, it is the writers’ ability to perceive (dis)similarities between the prior learning and the new and unfamiliar writing task that triggered such a successful transfer.

Because they are similar in nature. I put forth a translation method in a similar way I put forth an opinion in argumentative essays. (Tina)

5.2. Reshaping of rhetorical knowledge

Beyond the low road, we traced in the interviewees’ discourse a shift from applying whole genres to reshaping certain aspects of the learnt genres to fit the thesis writing. Reiff and Bawarshi (Citation2011) defined students observed to exhibit these behaviours as “boundary crossers”, engaging in high-road transfer (Perkins & Salomon, Citation1988), which is an important indication of adaptive transfer.

5.2.1. Breaking down into strategies

There were four strategies that our informants reported to have drawn from earlier writing courses and repurposed to more challenging task of bachelor’s thesis writing.

5.2.1.1. Providing sufficient examples

All four informants commented on the extensive use of this strategy in their theses which they acquired from their previous learning of argumentative writing.

There was an ABAB-form of replicated words that could be used as adjectives. You have to provide sufficient examples to support your ideas.’ (Alice)

Similarly, Shirley and Tina acknowledged that they transferred this strategy because they saw the two writing situations were “similar in nature” and “in some way related”. Alice, seeing the searching for appropriate examples as her trouble spot, further recounted in the interview the tremendous efforts she made to transfer this strategy.

I even consulted my friends in the Chinese Department, but still could not find enough examples. Actually, I spent a lot of time searching for the suitable ones in writing my Chapter 3. (Alice)

5.2.1.2 Following a chronological order

Commenting on one section in her Chapter 2 which traced the development of “Skopos Theory” (a theory of translation that informed her entire thesis), Tina mentioned empathetically her adherence to the chronological order which was imported from her earlier learning of narrative writing. She articulated the content, purpose, and way of unfolding in this text (which could be associated with historical recount in SFL terms) and demonstrated a heightened awareness of how this strategy could be appropriately recontextualised, as shown in the following excerpt:

When you presented Skopos Theory in this section, what kind of genre do you think you were using?

I reviewed the four stages of its development. It was first put forward by the mentor and then further developed by his apprentices.

So, you traced back its history? When you were writing this section, do you think you were referring back to what you had learnt in the writing courses?

Yes. I followed the chronological order.

When, or where, did you learn this kind of writing strategy?

In the narrative writing.

5.2.1.3. Classifying items based on similarities and differences

Reflecting on her experiences in writing Chapter 2 in her thesis (about rhetorical devices used in English advertisements), Shirley expressed her initial anxiety over the large number of rhetorical devices she needed to handle and the difficulties in “giving a detailed description of all of them in a well-organised way”. Her final solution was to “classify them first, based on their similarities and differences, and then introduce each in terms of its definition, rhetorical effects, and typical examples”. This remark on the use of classification soon found an echo from Tina. Yet, to our surprise, neither of them recalled having received any systematic training on this type of writing (classifying report in SFL terms) and thus suffered from a disorientation in the beginning, and both informants then attributed their uptake of this strategy to “reading relevant scholarly works in the field”. Referring back to the IW corpus data, we found that despite the lack of explicit instruction on classifying reports in prior writing courses, the students were exposed to an analogous genre (i.e., descriptive reports) in the same genre family. A possible explanation could be that “reading relevant scholarly works in the field”, serving as a catalyst for transfer, facilitated the students to adopt the classifying strategy to reshape what they had previously learnt in the thesis writing.

5.2.1.4. Arguing from opposing sides

When elaborating on the strategy of “providing sufficient examples”, Tina also reemphasised the need of doing this from opposing standpoints.

To prove that it (a translation method) works effectively, I have provided a lot of examples, from both the positive and negative side. I think it is a process similar to argumentation. (Tina)

The idea of “arguing from opposing sides” could be associated with the elemental genre discussion in SFL. Surprisingly, we found in the two corpora that discussion was merely sporadically practiced in the prior writing courses and was equally sporadic in the macrogenre of bachelor’s theses. Therefore, the thesis writers’ reported success in transferring this writing strategy sounded particularly inspiring, as it pointed to the possibility for generic knowledge to transfer even when there were few, if any, explicit stimuli.

5.2.2. Resituating rhetorical resources

Besides the writing strategies, the boundary crossers also reported to have resituated four types of rhetorical resources that cut across the word, sentence/clause, and discourse levels, indicative of the boundary-crossers’ awareness of how the two writing situations differed in their core rhetorical values.

5.2.2.1. Points of view: From first-person to third-person

I used to write in the first-person perspective in essays. Teachers always told us that it would make our essays more authentic and credible. However, the bachelor’s thesis required objectivity, so the first-person should be avoided. I changed into the third-person perspective to make my thesis sound more objective. It’s different from the essays. (Alice)

Alice’s change of point of view derived from her perceived disassociation between the two writing contexts—a simplistic dichotomy for essay writing to be genuine, subjective, and full of self-expression, and thesis writing, as traditionally conceived, to be scientific, objective and void of human touch. As the excerpt revealed, the dichotomy was further boiled down to the use of first- or third-person perspectives in her own writing.

5.2.2.2. Basis of argumentation: From general knowledge to specialised knowledge

My analysis of these translation methods involved both expository and argumentative writing, but everything must be closely connected with the overarching principle introduced in the preceding chapter. This is one aspect in which thesis writing is different from the earlier essay writing. (Alice)

In the writing courses, students were frequently guided to write argumentative essays on topics related to critical or controversial issues in real life and were encouraged to base their arguments on general knowledge about the world or their personal experiences. In writing a bachelor’ thesis, by contrast, they were engaged in transmitting or creating knowledge in a disciplinary field and expected to establish arguments using evidences from discipline-appropriate sources. This gap between the two writing scenarios, as recognised by Alice, prompted her to change, or reshape, her way of arguing.

A similar story was shared by Tina, who recalled that in the first draft of her thesis she failed to connect her analysis of the topic to the theories in the relevant field. She was alerted to this problem by her thesis advisor and in the revised version redressed it by “elaborating on my analysis by linking them to the theories”, in a way that she felt “resembled argumentation”.

5.2.2.3 Lexical choice: From diversity to accuracy

During the interview, Alice related her obstacles in finding appropriate words at certain places in the thesis, which was caused by her “lexical shortage”. When asked how she resolved this problem, she explained that she first “looked up in an on-line dictionary which listed several words with close meanings”, and then she examined closely their “different shades of meaning” and “chose the one that fit the most”. As such, Alice articulated the differences in diction she perceived between essay writing and bachelor’s thesis.

When writing the essays, we did not pay much attention to the delicate shades of meaning among synonyms. Instead, we were encouraged to use them interchangeably to show lexical richness. However, in bachelor’s theses, the words used must be accurate, so we need to be more mindful towards wording. (Alice)

It can be inferred that, in Alice’s eyes, essays written in the courses tended to value lexical richness, whereas bachelor’s theses required a contracted range of lexical items with an advanced mastery of their exact meanings.

5.2.2.4. Syntactic/clausal structure: From complexity to simplicity

In essay-writing, we were often encouraged to use complex clauses, but in the bachelor’s thesis, we were told to better use simple sentences to make ourselves easily understood. Bachelor’s theses require conciseness. If we used too many complex clauses inappropriately, it would cause ambiguity, making the thesis less precise. (Alice)

Just as third-person perspective was associated with “objectivity”, simple sentence structure was, according to Alice, associated with “conciseness” of information and “unambiguity” of meaning——two crucial requirements for bachelor’s theses. Although the truth of such reductionist association remained to be verified, they prompted the thesis writer to mindfully flex their rhetorical muscles at both the discourse and sentence level.

5.2.3. Reinventing rhetorical patterns: An emerging “Exemplification” stage

In the BT corpus, we identified a new optional stage, termed as “Exemplification”, in a variety of elemental genres, such as descriptive reports, classifying reports, expositions and factorial explanations. This stage was consistently recurrent across the BT corpus, but was never found in the IW corpus. presents an examplar of this generic stage in Shirley’s thesis (slightly abbreviated due to the space limit), which unfolds through a recurrent three-phase struture: [orientation ^ example ^ elucidation].

Table 3. Exemplification stage in bachelor’s theses

This new generic pattern emerged as a widely-discussed theme in the focus group, suggestive of another significant aspect of adaptive transfer. Our initial speculation is that it could be a by-product of the transferred strategy of “providing sufficient examples”. As the interview discussion went more in-depth, the students exhibited a critical awareness towards this stage, commenting on its functioning at the interface of two genre families. Tine and Alice, for example, recalled their use of Exemplification, particularly in sections devoted to the analyses of translation methods. Both of them considered their global purpose in these sections as ‘to show, to describe these translation methods to the readers (reminiscent of reporting genres), whereas attributed a persuasive role to this additional stage that helped them “link the analysis of these translation methods with some overarching theories” and thus “convince the readers that they were truly sound and effective”—in a way that “resembled the argumentative writing”.

The invention of this rhetorical stage manifests the transformative and cross-contextual attributes of adaptive transfer. That it adds a persuasive effect to elemental genres which are supposed to be informative and descriptive opens up a sophisticated issue in the field of genre research—that of “genre mixing” or “genre blending” (e.g., Martin & Rose, Citation2008; Reynolds, Citation2000). However, theoretical discussions around this issue have been too complicated thus beyond the scope of this paper. On this point, it might be more useful to cite the interviewee’s own coined phrase “genre grafting” (it was a figurative use the equivalent Chinese word “jia jie”, meaning that one part of a plant or tree is cut and added onto another, so that they are joined together to produce a new variety) to capture the writer’s idiosyncratic manipulation of generic resources and the related boundary-crossing behaviour—instantiating one genre with marked characteristics drawn from another.

Just like grafting, the Exemplification functioned to draw the two types of writing together. (Alice).

6. Discussion

The present study first examined the coherence between the two rhetorical phases of the English-major students’ literacy journey. Analysing the two corpora based on SFL genre theory and then comparing the results through log-likelihood tests, it is found that seven elemental genres received fairly appropriate instructional support that matched well with their rhetorical contribution to bachelor’s theses, whereas another 15 elemental genres received either excessive or insufficient attention. More importantly, this paper offered a detailed account of how four English-major students in a Chinese university adaptively brought the known genres from the earlier instruction to bear on the new situation of bachelor’s thesis writing. Rather than viewing transfer as something that either occurs or does not—a traditional binary view critiqued by DasBender (Citation2016) as reductionist and ultimately unproductive, this study unpacked what actually happened when transfer was successfully attempted, offering a humble addition to the burgeoning conversations around L2 writing transfer.

In this study, the acts of transfer manifested themselves on two distinct yet related lanes. When connection or disconnection was forged between the two contexts, students immediately formed a decision to reuse (or not to use at all) certain whole genres priorly acquired. Such a decision and its related performance indicated transfer on the low road (Perkins & Salomon, Citation1988), possibly because the students had a profound understanding of the known genres that had become automatic.

Beyond that, the known genres were not always neatly transferred but rather reshaped to suit the new and fluid situations, indicating transfer on the high road (Perkins & Salomon, Citation1988). Particularly recognizable to this second lane of transfer were a set of writing strategies, rhetorical resources, as well as an emerging generic pattern that the students repurposed, reconstructed, and reinvented into the bachelor’s theses. These reported behaviours reflected the thesis writers’ ability to view genre as an elastic rhetorical space rather than “a blueprint for replication” (Bhatia, Citation2004, p. 208). Our study, therefore, not only supported Cheng (Citation2007) and Nowacek (Citation2011) who argued for viewing transfer as recontextualisation, but clearly illustrated what recontextualisation, as “a complex rhetorical act” (Nowacek, Citation2011, p. 20), could possibly look like. There were a few cases where our informants recalled having received inadequate instruction on certain genres but still managed to recontextualise them via some useful strategies. A possible reason could be that our informants were all competent and highly motivated writers who were apt to engage in transfer. This particularly promising sign of adaptive transfer, however, does not render our prelogical efforts unnecessary. On the contrary, we do believe that more balanced and more explicit input on these genres would be helpful to make transfer easier and more attainable in the output.

As with DasBender (Citation2016), our study focused on a small group of competent L2 writers who are native Chinese speakers. However, different from DasBender’s (Citation2016) focal student, Shiyu, who showed positive signs of near transfer (on the low road) but made no mention of adaptive transfer in the reflective writing, the students in our study exhibited more conscious and reflective behaviours of far transfer (on the high road) that indicated adaptive transfer. This discrepancy perhaps is to do with our different methodological choices. While DasBender (Citation2016) surmised that the reflective writing prompts she used in her study did not prime the participants for recognizing adaptive transfer, the focus interview questions used in our study could have more directly invoked the students’ attention to this phenomenon.

7. Conclusion: Implications and limitations

7.1. Pedagogical implications

Our findings could yield important pedagogical implications for “teaching for transfer” in the field of L2 EAP writing.

First, our diagnosis of the connects and disconnects in the literacy journey of the English-major students can be useful for curriculum developers. With a refined curriculum that accommodates the target genres in bachelor’s theses, EAP writing instructors will be better equipped to pave a smooth and even seamless way for students moving from the instructional settings to the culminating thesis writing. What we mean to suggest here is a more balanced allocation of pedagogical investment in the L2 EAP writing classrooms. We do not, however, call for a rigid alignment between the two contexts, because, although teaching toward the bachelor’s thesis is certainly one of the goals of writing courses, well beyond that, our aim should be to build flexible writers that are capable of responding to a wide range of rhetorical contexts. In general, there can be benefits to students learning a wide (perhaps, in this case, a wider) range of genres and then learning to make choices about how to utilise those genres in meaningful and appropriate ways, adapting their genre knowledge to ever-evolving contexts (Johns, Citation2008, p. 238).

Second, the insights drawn from a small number of proficient and highly aware writers who successfully performed adaptive transfer would be helpful for thesis advisors and thesis writers struggling for success in similar EFL writing contexts. One viable way to facilitate future thesis writers, especially the less-achieving ones, could be to adopt enabling practices as suggested in Elon Statement on Writing Transfer (Citation2015), such as providing rhetorically-based concepts for students to analyse the expectations of varied writing situations, engaging them in activities that foster the development of metacognitive awareness, and explicitly modelling transfer-focused thinking—–ultimately, equipping the students with tools and strategies for successful boundary crossing.

7.2. Limitations and suggestions for future research

Despite its effort to offer a deeper understanding of adaptive transfer in L2 EAP writing, our study is not without its limitations. First, due to the limited time span, our data were collected cross-sectionally, instead of longitudinally, from the two rhetorical contexts under focus. Future studies may take the longitudinal approach, if possible, to follow the same group of students throughout the entire undergraduate study and draw a more accurate sketch of their literacy journey. Second, the thesis writers participating in our focus group interview were all “successful writers”. It is uncertain, therefore, if adaptive transfer would occur in similar ways with less successful and less competent writers. Future studies may compare different stories of students at different proficiency levels, so as to arrive at a more robust understanding of transfer as “a complex rhetorical act” (Nowacek, Citation2011). Finally, this study was situated in one single institution in China and only addressed academic writing in the discipline of English. Since learning, writing, and transfer are all situated activities that need to be interpreted context-specifically, future endeavours that pursue new or replication studies in varied social, cultural, and disciplinary contexts (e.g., the non-English-major students in China who learn EAP writing in their specialised fields) and compare their results to those generated here would be tremendously valuable. With such expanded efforts, we may allow new perspectives to become visible and a thorough understanding to be formed about transfer in L2 academic writing contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Issra Pramoolsook

Yimin Zhang holds a PhD in English language studies and is now a lecturer at School of Foreign Languages, Chongqing Jiaotong University, China. Her research interests include genre analysis, academic discourse, L2 writing, and Systemic Functional Linguistics.

Issra Pramoolsook holds a PhD in Applied Linguistics and English Language Teaching and is an Assistant Professor at School of Foreign Languages, Institute of Social Technology, Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand. His research interests include disciplinary and professional discourses analysis, genre analysis, L2 writing, and genre-based approach to teaching writing.

The study reported in this paper is part of a larger project in which the authors have synergised systemic functional linguistics, ethnography as methodology, and the theory of adaptive transfer in an effort to look deeply into the academic literacy development by Chinese English-major students.

References

- Beaufort, A. (2012). College writing and beyond: Five years later. Composition Forum, 26. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ985817.pdf

- Bhatia, V. K. (2004). Worlds of written discourse:A genre-based view. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Cheng, A. (2007). Transferring generic features and recontextualizing genre awareness: Understanding writing performance in the ESP genre-based literacy framework. English for Specific Purposes, 26(3), 287–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2006.12.002

- Cheng, A. (2008). Individualized engagement with genre in academic literacy tasks. English for Specific Purposes, 27(4), 387–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2008.05.001

- Coffin, C., & Donohue, J. (2014). A language as social semiotic based approach to teaching and learning in higher education. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- DasBender, G. (2016). Liminal space as a generative site of struggle: Writing transfer and L2 students.”. In C. M. Anson & J. L. Moore (Eds.), Critical transitions: Writing and the question of transfer (pp. 273–298). The WAC Clearinghouse.

- DePalma, M.-J., & Ringer, J. M. (2014). Adaptive transfer, writing across the curriculum, and second language writing: Implications for research and teaching. In T. M. Zawacki & M. Cox (Eds.), WAC and second language writers: Research towards linguistically and culturally inclusive programs and practices (pp. 43–67). The WAC Clearinghouse.

- DePalma, M.-J., & Ringer, J. M. (2011). Toward a theory of adaptive transfer: Expanding disciplinary discussions of “transfer” in second-language writing and composition studies. Journal of Second Language Writing, 20(2), 134–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2011.02.003

- Detterman, D. K. (1993). The case for the prosecution: Transfer as an epiphenomenon. In D. K. Detterman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Transfer on trial: Intelligence, cognition, and instruction (pp. 1–24). Ablex Publishing Corporation.

- Dreyfus, S. J., Humphrey, S., Mahboob, A., & Martin, J. R. (2015). Genre pedagogy in higher education: The SLATE project. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Elon Statement on Writing Transfer. (2015). https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/elon-statement-on-writing-transfer/

- Fishman, J., & Reiff, M. J. (2008). Taking the High Road: Teaching for Transfer in an FYC Program. Composition Forum, 18. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1081005.pdf

- Fishman, J., & Reiff, M. J. (2011). Taking it on the road: Transferring knowledge about rhetoric and writing across curricula and campuses. Composition Studies, 39(2), 121–144.

- Foertsch, J. (1995). Where cognitive psychology applies: How theories about memory and transfer can influence composition pedagogy. Written Communication, 12(3), 360–383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088395012003006

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. (2014). An introduction to Functional Grammar (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Hill, C., Khoo, S., & Hsieh, Y.-C. (2020). An investigation into the learning transfer of English for Specific Academic Purposes (ESAP) writing skills of students in Singapore. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 48, 100908. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100908

- Huang, G. (2002). Hallidayan linguistics in China. World Englishes,211, 281–290. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-971X.00248

- James, M. A. (2009). “Far” transfer of learning outcomes from an ESL writing course: Can the gap be bridged? Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(2), 69–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2009.01.001

- James, M. A. (2010). An investigation of learning transfer in English-for-general-academic-purposes writing instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing, 19(4), 183–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2010.09.003

- James, M. A. (2014). Learning transfer in English-for-academic-purposes contexts: A systematic review of research. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 14, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2013.10.007

- Johns, A. (2008). Genre awareness for the novice academic student: An ongoing quest. Language Teaching, 41(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444807004892

- Johnston, J., Berry, K., & Mielke, P. (2006). Measures of effect size for chi-squared and likelihood-ratio goodness-of-fit tests. Perceptual & Motor Skills, 103(2), 412–414. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2466/2Fpms.103.2.412-414

- Jordens, C. F., & Little, M. (2004). ‘In this scenario, I do this, for these reasons’: Narrative, genre and ethical reasoning in the clinic. Social Science & Medicine, 58(9), 1635–1645. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00370-8

- Jordens, C. F., Little, M., Paul, K., & Sayers, E. J. (2001). Life disruption and generic complexity: A social linguistic analysis of narratives of cancer illness. Social Science & Medicine, 53(9), 1227–1236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00422-6

- Li, Y., Ma, X., Zhao, J., & Hu, J. (2020). Graduate-level research writing instruction: Two Chinese EAP teachers’ localized ESP genre-based pedagogy. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 43, 100813. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2019.100813

- Martin, J. R. (1997). Analyzing genre: Functional parameters. In F. Christie & J. R. Martin (Eds.), Genre and institutions: Social processes in the workplace and school (pp. 3–39). Continuum.

- Martin, J. R. (2002). From little things big things grow: Ecogenesis in school geography. In R. Coe, L. Lingard, & T. Teslenko (Eds.), The rhetoric and ideology of genre: Strategies for stability and change (pp. 243–271). Hampton Press.

- Martin, J. R., & Rose, D. (2008). Genre Relations: Mapping Culture. Equinox.

- Matsuda, P. K. (1997). Contrastive rhetoric in context: A dynamic model of L2 writing. In T. Silva & P. K. Matsuda (Eds.), Landmark essays on second language writing (pp. 241–255). Erlbaum.

- Nesi, H., & Gardner, S. (2012). Genres across the disciplines: Student writing in higher education. Cambridge University Press.

- Nowacek, R. S. (2011). Agents of integration: Understanding transfer as a rhetorical act. Southern Illinois University Press.

- Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (1994). Transfer of learning. In T. Husen & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), The international encyclopaedia of education (Vol. 11, pp. 6452–6457). Pergamon.

- Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (1988). Teaching for transfer. Educational Leadership, 46(1), 22–32.

- Reiff, M. J., & Bawarshi, A. (2011). Tracing discursive resources: How students use prior genre knowledge to negotiate new writing contexts in first-year composition. Written Communication, 28(3), 312–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088311410183

- Reynolds, M. (2000). The blending of narrative and argument in the generic texture of newspaper editorials. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 10(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2000.tb00138.x

- Rose, D. (2017). Languages of Schooling: Embedding literacy learning with genre-based pedagogy. European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 5(2), 1–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2017-0008

- Shrestha, P. N. (2017). Investigating the learning transfer of genre features and conceptual knowledge from an academic literacy course to business studies: Exploring the potential of dynamic assessment. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 25, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2016.10.002

- Szenes, E. (2017). The linguistic construction of business reasoning: Towards a language-based model of decision-making in undergraduate business. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Sydney.

- Tardy, C. M. (2016). Beyond convention: Genre innovation in academic writing. University of Michigan Press.

- Teaching Advisory Committee for Tertiary English Majors. (2000). English Teaching Syllabus for English Majors. [Chinese.]

- Wardle, E. (2007). Understanding ‘transfer’ from FYC: Preliminary results of a longitudinal study. Writing Program Administration, 31(2), 65–85.

- Wardle, E. (2009). ‘Mutt Genres’ and the goal of FYC: Can we help students write the genres of the university? College Composition and Communication, 60(4), 765–789.

- Wingate, U. (2012). Using Academic Literacies and genre-based models for academic writing instruction: A ‘literacy’ journey. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 11(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2011.11.006

- Zarei, G. R., & Rahimi, A. (2014). Learning transfer in English for General Academic Purposes writing. SAGE Open, 4(1), 2158244013518925. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013518925

- Zhang, Y., & Pramoolsook, I. (2019). Generic complexity in bachelor’s theses by Chinese English majors: An SFL perspective. GEMA Online ® Journal of Language Studies, 19(4), 304–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17576/gema-2019-1904-16