Abstract

In this study, which endeavored to identify school climate factors and their influence on adolescent students’ feelings of school belonging, it became evident that a new conceptualization thereof is needed. Quantitative data from 443 male and female 11th graders and 264 of their teachers and qualitative data from 16 students and eight of their teachers in Al Ain public school district were collected. The findings revealed that adolescents perceived parental involvement, classroom practices, teacher-student relationships, safety and school social practices, and peer relationships in novel and different ways to their teachers. Various factors including parental involvement, teacher-student relationships, and classroom practices were viewed as unimportant in promoting student belonging. The adolescents appeared to be more concerned with safety and school social life and peer relationships. The findings are significant for policymakers and practitioners in their quest to improve the educational experiences of adolescent students and facilitate their psychosocial development.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The purpose of this study was to identify school climate factors and their influence on adolescent students’ feelings of school belonging. Five school climate factors were identified: parental involvement, classroom practices, teacher-student relationships, safety and school social practices, and peer relationships. Students and teachers concurred that peer relationships and safety and school social practices predicted students’ sense of belonging more than parental involvement, classroom practices, and teacher-student relationships. The findings are important for policymakers and practitioners in their endeavors to enhance the educational experiences of adolescent students and facilitate their psychosocial development. A key conclusion of this research might be that adolescents need to feel belonging to school but this cannot happen unless the school climate is characterized by love, respect, care, equity, comfort, and acceptance.

1. Introduction

Each school has a unique set of characteristics which constitutes its climate. School climate is defined as “the patterns of people’s experiences of school life; it reflects the norms, goals, values, interpersonal relationships, teaching, learning and leadership practices, and organizational structures that comprise school life” (National School Climate Center, Citation2011, p. 2). A positive school climate is imperative for healthy learning experiences (Freiberg & Stein, Citation1999, p. 11), students’ social and moral development (Weissbourd et al., Citation2013), and students’ feeling of safety in interacting with peers and teachers (Allen & Bowles, Citation2012). In such a climate, where the psychosocial needs of students are developed, their sense of school belonging will increase (Cemalcilar, Citation2010).

Students’ sense of school belonging was defined by Qin and Wan (Citation2015, p. 830) as “students’ perceptions of being involved, recognized, and supported.” The feeling of belonging could enhance students’ relatedness to school (Fong Lam et al., Citation2015), their willingness to abide by its rules (Dehuff, Citation2013), and their motivation to be more conscientious academically (Goodenow, Citation1993b). Furthermore, they are likely to experience less violence (Aliyev & Tunc, Citation2015). On the contrary, students who do not feel accepted and cared for tend to be demotivated and lack the desire to attend school (Sánchez et al., Citation2005).

Although it is of the utmost importance for schools to employ all the means available to create a positive school climate, many merely focus on student performance. Wellman (Citation2006) demonstrated that if schools place more emphasis on achievement, they may not focus on their mission of developing the whole student and their enjoyment of school life. Students’ ability to relate to others (Johnson, Citation2009) and attendance at school (Sánchez et al., Citation2005) may be affected adversely in such a climate.

2. Problem and purpose

The education sector in the United Arab Emirates aims to develop a first-class education system in which schools are transformed into smart learning environments. The UAE 2021 National Agenda asserts that to compete internationally, it is imperative that the education system undergoes a complete transformation in management, curricula, and teaching methods so as to satisfy the content and skill requirements of international exams (UAE Cabinet, Citationn.d.). Accordingly, more demands have been placed on schools to improve student achievement with subsequent increases in teachers’ responsibilities. Farooqui (Citation2019) and Morgan and Ibrahim (Citation2019) revealed that teachers’ roles have expanded to include more paper and administrative work so as to achieve accountability demands. Consequently, appropriate student-centered teaching, student care, and the satisfaction of their emotional and social needs have been overlooked. In such a results-driven climate, students may feel pressurized and their time for socializing with peers, teachers, administrators, and coaches as well as for extracurricular activities has become limited (Farooqui, Citation2019).

Local studies as well as international reports on the UAE have supported the fact that existing school climates do not enhance students’ sense of belonging. Abu Dhabi students, the largest UAE student population, who completed the TIMSS questionnaire revealed that their sense of school belonging was rated at only 21%, which is low in comparison to the international average of 44% (IEA TIMSS and PIRLS, Citation2015). Furthermore, while 11% of students in Abu Dhabi were absent from school more than once a week, the international average for such was 8%. Frequent absenteeism may be linked to school-based problems and related to a low level of school belonging (Faour, Citation2012).

While evidence has shown that students’ sense of belonging is problematic, there has been a paucity of research on this topic. The only study conducted was by Ibrahim and El Zaatari (Citation2020) and who found that the teacher-student relationships’ dimesions of affect, power, and reciprocity were negative. The present study explored adolescent students and their teachers’ perceptions on the contextual school climate factors that may influence students’ sense of belonging to present a more comprehensive account of the topic.

3. Significance of the study

This study revealed evidence of the influence of school climate on students’ sense of belonging and identified the most significant factors in the UAE context. Consequently, the results may support administrators and policymakers in their quest to enhance school practices to satisfy the psychosocial and academic development of adolescent students. Furthermore, this study afforded an opportunity to explore adolescents’ perceptions of their school experiences as an under-researched group on the issue.

4. Theoretical framework

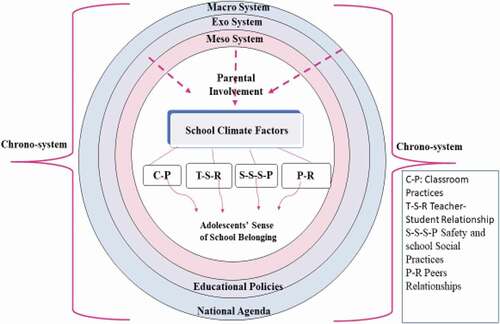

Allen and Bowles (Citation2012, p. 110) asserted, “Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model provides the most comprehensive theoretical construct to date with which to investigate belonging in an organizational setting such as a school.” Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979, p. 3) regarded the ecological environment “as a set of nested structures, each inside the next, like a set of Russian dolls.” These systems include the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem.

Bronfenbrenner (Citation1993) noted that unless the entire four-part ecological system is considered, human development cannot be understood. Accordingly, adolescents’ development of a sense of school belonging can be explained by examining two types of interaction: distal and proximal. Distal interactions are best elucidated in light of interactions between the three systems, namely, the macro, exo, and meso as well as the school microsystem. The UAE National Agenda and social norms, which constitute part of the macrosystem, have an impact on the education system and policy development within the exosystem. When policymakers enact a particular educational policy in the exossystem, parents’ relationship with the school within the mesosystem and everyday practices within the school microsystem are affected. In turn, these practices have an effect on teachers and students (Hayes et al., Citation2017).

Proximal interactions in the school microsystem not only encompass all school and classroom activities but also relationships among students, teachers, and other school members. Furthermore, proximal interactions at home between parents and adolescent students may influence adolescents’ development of school belonging. Bronfenbrenner added a fifth ecological system to the theory: time or the chronosystem, (Krishnan, Citation2010). This system indicates the role time may play in changing school ecology. In this study, chronosystem relates to changes in educational policies that occur over time such as additional curriculum and exam requirements, which may have an effect on adolescent students’ sense of school belonging. Keeping this framework in mind, the study was set to investigate the topic.

5. Literature review

In this study, five factors were assumed to constitute the school climate: classroom practices, teacher-student relationships, safety and school social practices, peer relationships, and parental involvement. With the exception of parental involvement, the factors are embedded within the school’s microsystem. The Ecological System Theory classifies parental involvement as part of home microsystem and at the same time it belongs to the mesosystem of home and school (Faour, Citation2012; Smith, Citation2015). The ecological system as well as school climate factors are depicted in .

Parental involvement could play a role in enhancing a sense of school belonging when they provide their children with academic and social support both at home and school. When parents are involved in their adolescents’ education, care about their performances, and discuss their future plans, their children are likely to become more motivated to work harder, cope with academic challenges, have positive beliefs about their abilities to succeed (Wang & Sheikh‐Khalil, Citation2014), and have a positive attitude toward their schools in general (Uslu & Gizir, Citation2017).

Classroom practices constitute another school climate factor that could play a vital role in enhancing adolescents’ sense of school belonging. Teachers are pivotal in implementing classroom practices such as encouraging students to work cooperatively (Goodenow, Citation1993b; Miller & Desberg, Citation2009), relating tasks to students’ interests (Faour, Citation2012; Miller & Desberg, Citation2009; Wallace et al., Citation2012), encouraging critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and creativity as well as controlling misbehavior and bullying (Miller & Desberg, Citation2009). However, overemphasis on exams and performance could affect classroom practices and the teacher-student relationship negatively. Subsequently, teachers’ attention may not be focused on building healthy relationship with students (Ritt, Citation2016).

The teacher-student relationship is of paramount importance. Chhuon and Wallace (Citation2014) stated that this relationship should be highly affective, supportive, and attentive to students’ needs. When teachers exhibit a caring attitude, students’ social and emotional security develops and consequently, their sense of belonging is enhanced (Goodenow, Citation1993a).

The fourth school climate factor that could affect students’ sense of belonging comprises safety and school social practices (Allen & Bowles, Citation2012; Haugen et al., Citation2019). If students feel insecure at school, they may not only experience negative feelings (Cemalcilar, Citation2010) but also be unable to learn. Safety encompasses not only the absence of danger but also psychological safety, respect, and protection (National Association of School Psychologist, Citation2013). School social practices, including extracurricular activities and leadership roles, can afford students significant learning experiences which could lead to increased sense of belonging (Farrell, Citation2008), enhanced social skills (Eccles et al., Citation2003), and improved adaptability to challenges (Ashley, Citation2014).

Peer relationships are also crucial for adolescent development (Wallace et al., Citation2012) and may enhance their sense of belonging (Dehuff, Citation2013). Uslu and Gizir (Citation2017) found that peer relationships improve students’ psychological and emotional well-being, social control, coping strategies, and problem-solving skills. It is noteworthy that not all peer relationships have a positive impact on identity development because adolescents could become involved in antisocial behavior (Smith, Citation2015) and/or engage in aggression and bullying (Guerra et al., Citation2011). Smokowski et al. (Citation2014) revealed that students who were victims of physical and/or verbal bullying did not feel secure at school. In such a context, Kim (Citation2018) noted that these feelings definitely lead to a decrease in the sense of school belonging.

6. Methodology

6.1. Design

An explanatory sequential mixed methods design was employed in the study. This design is characterized by an initial quantitative phase of data collection and analysis that uses a survey. Subsequently, a qualitative phase of data collection and analysis was conducted by employing a phenomenological design to explain the results obtained from the quantitative phase (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2011).

6.2. Setting

The study was conducted at secondary public schools in Al Ain city, UAE. There were 14 secondary public schools in Al Ain: seven for male students and seven for female students as secondary schools are segregated. There were 2,802 grade 11 students and 798 teachers in the 14 schools.

6.3. Study sample

In the quantitative phase of the study, cluster sampling was employed to select the participants where the school was the cluster. Eight, four male and four female, of the 14 schools were randomly selected. The sample for this study comprised 443 students and 264 teachers, which was higher than the sample size determined with a confidence level of 95 %. Information related to the students and teachers’ samples is presented in .

Table 1. Students and teachers’ samples

Purposeful sampling was used to select the participants in the qualitative phase so as to provide thorough descriptions of the studied phenomena. The participants included eight grade 11 female students and four teachers from one school as well as eight grade 11 male students and four teachers from one school.

6.4. Instruments

Two questionnaires, one for teachers and one for students, were developed by the researchers after an extensive review of the literature were employed in the first phase of the study. Each instrument was divided into six sections: parental involvement, classroom practices, teacher-student relationships, peer relationships, safety and school social practices, and school belonging. While the students’ questionnaire comprised 29 items, the teachers’ questionnaire had 30 items, which were assessed on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A jury of scholars determined the content and construct validity of the questionnaires before the students and teachers completed a pilot test. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.829 and 0.851 for the students and teachers’ questionnaires, respectively.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in the qualitative phase of the study. The interview questions sought to understand and interpret the results obtained from the quantitative phase.

6.5. Data analysis

Multiple linear regression was performed to identify the most important school climate factors that may have an influence on adolescent students’ sense of school belonging. Thematic analysis was employed in the second phase of the study. NVivo Pro 11 was used to code the data. After coding, different themes were identified and then merged into categories. To ensure inter-rater reliability, the two researchers worked separately when classifying the data into themes and categories. Subsequently, they shared their decisions with one another and agreed on the final results.

7. Results of the study

7.1. Quantitative results

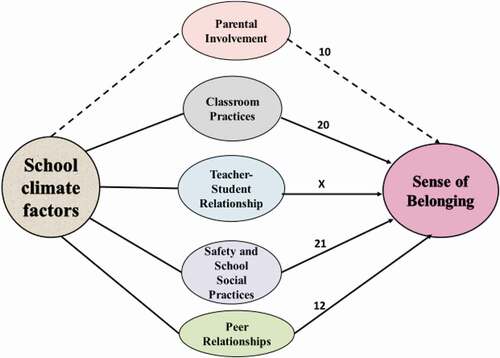

Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify the most important school climate factors that could influence adolescent students’ sense of school belonging from the perspective of the students. The results are displayed in .

Table 2. Multiple linear regression output summary: students

The model of the five school climate factors that could have an influence on adolescent students’ sense of belonging is displayed in . The factors include parental involvement, classroom practices, teacher-student relationships, safety and school social practices, and peer relationships. Regression analysis was performed to predict the influence of these factors on feelings of school belonging. As shown in , R = 0.50, which indicates a moderate positive correlation with an R2 of 0.25. This means that the five factors explained 25% of the variance in students’ sense of school belonging with a significant regression equation, F (5, 409) = 27.07, p < 0.00).

As shown in , the results revealed that teacher-student relationships did not significantly predict students’ sense of school belonging (Beta = 0.10, t = 1.81, p = .07). In contrast, the other four factors predicted students’ sense of belonging in the following order: safety and school social practices (Beta = 0.21, t = 3.76, p = 0.00), classroom practices (Beta = 0.20, t = 3.67, P = 0.00), peer relationships (Beta = 0.12, t = 2.60, p = 0.01), and parental involvement (Beta = 0.10, t = 2.28, p = 0.02). As shown in , a one-point increase in parental involvement, classroom practices, safety and school social practices, and peer relationships corresponded to 0.10, 0.27, 0.18, and 0.12 increases in students sense of belonging, respectively.

Table 3. Coefficients

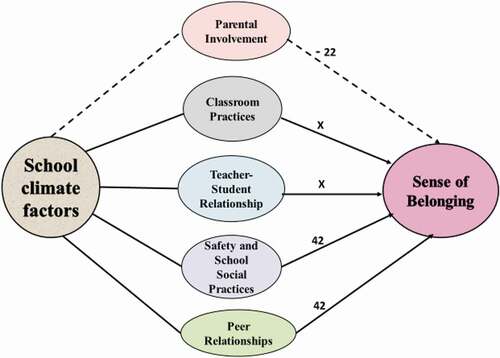

Multiple linear regression analysis was also performed to identify the teachers’ perspectives. The results are displayed in .

Table 4. Multiple linear regression output summary: teachers

As displayed in , R = 0.69, which indicates a moderately positive correlation with an R2 of 0.47. Thus, from the teachers’ perspective, the model linear regression explained 47% of the variance in the sense of school belonging with a significant regression equation, F(5, 200) = 35.330, p < 0.00.

As presented in , the teacher-student relationship (Beta = 0.01, t = 0.20, p = 0.84) and classroom practices (Beta = 0.05, t = 0.87, P = 0.38) did not predict the students’ sense of belonging significantly. However, peer relationships (Beta = 0.42, t = 7.43, p = 0.00) as well as safety and school social practices (Beta = 0.42, t = 6.19, p = 0.00) predicted belonging. On the contrary, parental involvement (Beta = −0.22, t = −4.07, p = 0.00) predicted a statistically significant negative relationship between the teachers’ perceptions of parental involvement and students’ sense of belonging. shows that a one-point increase in safety and school social practices and peer relationships corresponded to 0.42 and 0.40 increase in students’ sense of school belonging while a one-point increase in parental involvement corresponded to 0.22 decrease in belonging.

Table 5. Coefficients

The results revealed that both the students and teachers perceived the teacher-student relationship to be an insignificant predictor of the students’ sense of school belonging. While the students considered classroom practices to be a significant predictor of their sense of belonging, the teachers believed that classroom practices did not predict a sense of school belonging. Although the students and teachers concurred that school safety and social practices as well as peer relationships are significant predictors, the students did not give peer relationships a high prediction value. Although the students perceived parental involvement to be a weak predictor, the teachers perceived it as having the opposite impact on students’ sense of school belonging.

7.2. Qualitative results

The researchers collected qualitative data to acquire a deeper understanding of the results and facilitate the interpretation thereof. The following findings and explanations of the five factors were gleaned from the analysis of the qualitative data.

7.3. Factor 1: Parental involvement

The quantitative results revealed that the students perceived parental involvement to be a weak predictor of their sense of school belonging. They believed that their parents’ involvement was limited and sporadic as it did not go beyond material support such as buying stationery, study materials, and hiring a private tutor. While some of the students perceived that their parents listened, helped them solve problems, and involved them in sports and leisure, others, particularly the females, considered the support to be problematic. Mouza related, “I feel my mother doesn’t understand me … so I prefer to stay in my room and play with my phone.” She was also annoyed with her parents’ conservative views that prohibited her from visiting friends and participating in social activities.

The teachers’ views of parental involvement were not very positive. Mr. Housam noted, “Only 10% to 12% of the parents show up in workshops and activities.” Moreover, the students did not appear to welcome the idea of having a guardian or parent arriving at the school to discuss their behavioral and/or academic issues. Ms. Maha shared, “Students are tearing and ripping the notifications sent home.” It is possible that these opinions could explain why the teachers thought that parental involvement has a negative relationship with students’ sense of school belonging.

7.4. Factor 2: Classroom practices

The quantitative results showed that the students considered classroom practices to be a significant predictor of their sense of school belonging. However, their opinions about classroom practices were mostly negative and it was difficult to justify the discrepancies between their quantitative and qualitative results. First, some students complained about “traditional teaching and lecturing” (Ahmed, Afra, Iman, Salma, and Shamsa), “inability to comprehend some teachers” (Salma, Khalifeh, Afra, Hajer, Noura, and Moza), “dull or noisy classes” (Mohammed, Sultan, Shamsa, Salma, and Iman), and “inability of teachers to control students” (Salma and Badriyah). Others, especially male students, perceived teachers were “trying their best to make all students understand” (Naser), and “use break time to finish the required material for the exam” (Sultan). However, both male and female students agreed that some teachers were usually “inconsiderate” because their primary aims appeared to be “to finish the assigned curriculum” and “prepare students for the exams” (Badriya) because the school’s ranking was their main priority.

Second, most students experienced “too many exams” as a source of “suffering and stress” (Khalifah) and a reason for “hating school” (Afra and Mouza). Furthermore, having “too much homework … puts [students] under pressure and annoys some” (Khalifeh and Noura). Third, the students admitted that teachers punished them and while some male students related that teachers were patient with them, others had been subject to various forms of punishment such as “stand[ing] at the back of the class for the whole period,” and “detention” (Mouza, Ahmed, Iman, Noura, and Badriyah).

Many of the opinions the teachers expressed in the interviews supported the quantitative results that showed that classroom practices were not a predictor of students’ sense of belonging. The teachers appeared to be cognizant of what happened in the classrooms and to what it could lead. Although some teachers defended themselves and explained that they used “a variety of learning activities to avoid boredom and enhance learning,” others admitted that “students were not happy with lecturing and traditional teaching,” “excessive seriousness” (Mr. Housam), and becoming “bored and fatigued from being bombarded with information” (Ms. Mariam).

The interview data revealed that the teachers referred to “homework, quizzes, and frequent examinations” as contributing to student stress. Teachers also felt that the many responsibilities and frequent changes in the system as overwhelming. The students were aware that “the continuous changes in the curriculum make teachers and [them] feel very stressed and unstable” (Khalifa and Afra). In such a stressful atmosphere, in which teachers punished students “[even if] used as the last resort” as noted by some, it was not unexpected for teachers to dismiss classroom practices as a predictor of students’ sense of belonging.

7.5. Factor 3: Teacher-student relationships

Our quantitative results revealed that the students perceived the teacher-student relationship as an insignificant predictor of students’ sense of school belonging. Their negative perceptions may have been due to three reasons. First, the students, especially the females, believed the teachers were disrespectful and sometimes “downgrading” when they spoke with them. Salma related that some of the teachers conveyed a message that some students should be demoted. Second, some of the students, especially the females, did not perceive their teachers as caring, supportive, or motivating. While the male students were positive about their teachers’ psychological and academic support and they liked the way teachers motivated them, the females had a different perspective. Iman shared, “They do not care about what we are suffering from, like stress. They want us to obey their orders without any negotiation.”

Our data revealed various reasons underlying the teachers’ perception of the insignificance of their relationship with students as a predictor of students’ sense of school belonging. First, as noted by Ms. Maha, the students did not like them when they were “strict with grading.” Second, some of the teachers complained about students’ improper behavior, which caused them to shout and scream. Ms. Lina defended shouting and screaming at students because they were always trying to get out of class, disrupt class activities, waste time, and/or generally misbehave. Third, some of the teachers, especially those who were expatriates, feared they might lose their employment if they experienced problems with students, particularly national citizens. One may deduce that it was not surprising that the teachers perceived their relationship with students did not predict their sense of belonging.

7.6. Factor 4: Safety and school social practices

The students agreed that school safety and social practices was a significant factor in predicting their sense of school belonging. One reason may have been related to their perceptions that their schools had excellent safety measures. However, some students associated their safety at school to bullying and aggressive behavior. Their schools were not able to control problems between the students on the school premises and hence, “this create an unsafe feeling” (Ibrahim).

A second reason for the students’ positive perception about schools and hence, their belonging was related to various extracurricular activities. Many of the male and female students shared that they had many extracurricular activities and were encouraged to participate in competitions. Ahmed explained, “I feel like I am representing my school and I am trying to do all of my best to win.” However, some of the female students had negative views about extracurricular activities because of time the activities were held and family objections to their participation.

The teachers had positive views about the physical safety of the schools because “securities are found everywhere” (Ms. Maha) and “satfey at school was paramount” (Mr. Housam). Furthermore, their opinions about extracurricular activities were also positive. Schools had sports activities, open days, and many clubs. They usually competed against other schools, which allowed the students to become more engaged. Ms. Maha related, “We encourage students to participate in different activities … Any kind of activity that happened out of the classroom makes students feel happy.”

7.7. Factor 5: Peer relationships

The quantitative data demonstrated that the students and teachers regarded peer relationships as a significant predictor of sense of belonging even though the students did not give it high prediction value. Friends at school was a major factor underlying the sense of belonging both the male and female students experienced. Mansour stated, “I feel like it is my second home because of my friends.” Iman added, “Friends deal with me intimately … if I have any problem, I can share it with them.”

While friendship at school can enhance students’ sense of belonging, problems with peers may have a negative effect thereof. The problems the participants encountered were provoked by bullying and aggressive behavior because of misunderstandings, jealousy, uttering “harsh words” (Mohammed), and “sarcasm and lying” (Ibrahim). Mouza related, “Some [female] students hit each other, or try to pull another student’s hair aggressively.” However, in general, the students were positive about the impact of peer relationships on their sense of belonging.

Similarly, the teachers explained that one reason behind students’ sense of belonging was having friends at school. Ms. Rana related, “Our [female] students prefer to spend time socializing with their friends as their parents are conservative and [might] not allow them to see their friends outside school.” The teachers did not deny the existence of bullying and aggressive behavior in schools and confirmed that while friendship enhances feelings of belonging, bullying and aggressive behavior may reduce students’ attachment to school.

8. Discussion

The regression analysis of the students’ data revealed that the five school climate factors predicted their feelings of school belonging moderately with R = 0.50. Variance in their sense of school belonging was accounted for in our model by 25%. The teachers’ data indicated that there was a high moderate correlation (R = 0.69) with 47% variance in the students’ sense of belonging due to the five school climate factors. This is expected as the ecological model cannot address all factors in one study (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1989). In addition, Goodenow (Citation1993b, p. 87) viewed belonging “as arising from the person within a particular school environment.” Therefore, the individuality of human experience and complexity of school climate made it difficult to account for all other possible influencing factors.

Our data demonstrated that of the five school climate factors, perceptions of safety and school social practices were the strongest predictors of students’ sense of belonging. While safety at school is an essential aspect for the psychosocial and academic development of students, a safe environment enhances their school experience and builds a sense of belonging (Cemalcilar, Citation2010; Haugen et al., Citation2019). The qualitative data further revealed that safety does not only involve the physical setup or presence of safety measures. Rather, it should also encompass the psychological and emotional protection of students. While the participants believed that the school’s premises were mostly guarded, with the presence of security personnel and monitoring of student behavior by cameras, most of the female students and a few of the male students believed that they were suffering from the school’s inability to solve peer clashes and protect them from aggressive behavior. Feeling psychologically insecure not only contributes to students’ feeling a lack of belonging to the school, but may also have devastating effects on their personality development. This may also have an effect on students’ performances (Weissbourd et al., Citation2013) because adolescent students prefer a safe, comfortable environment in which to learn and develop (Huang et al., Citation2013). While our participants had positive views about school safety, we are of the opinion that in relation to the students’ psychosocial safety, more could have been done. However, a focus on test-preparation, grades, and ranking has limited the time allocated to this goal. At a macro-level, the UAE places high value on students’ happiness, well-being, and positivity (Warner & Burton, Citation2017). However, at the school micro-level, this may not translate into actions as the participants conveyed. Therefore, it is recommended that schools and teachers should find ways to provide more support to students’ development in this area.

In accordance with Bouchard and Berg (Citation2017), Farrell (Citation2008), and Eccles et al. (Citation2003), the quantitative data showed that involvement in extracurricular activities may lead to an increase in students’ connectedness to school. Furthermore, extracurricular activities may enhance students’ social development and help them to develop their identities, especially when they are afforded an opportunity to practice leadership in an activity (Bouchard & Berg, Citation2017). However, the qualitative data also indicated that there was not sufficient time for extracurricular activities and at times, families did not approve of their children’s participation; most notably, their female children. Despite its importance in increasing students’ sense of belonging, there may be limited focus on activities because of the competitive nature of the achievement-oriented system.

Although the quantitative data further found that classroom practices were the second strongest predictor of adolescent students’ sense of belonging, the qualitative data revealed a different view. The students were skeptical of classroom practices and criticized their teachers. They perceived their teachers used traditional and boring teaching styles, they were not tolerant and did not care about them, and some utilized punishment to manage the classes. The findings indicated that the teachers may not have handled the teaching and learning process properly. This may have been due to the pressure of many curricular and administrative demands as well as preparing students for local and international exams. Warner and Burton (Citation2017) noted that teachers may adopt traditional teaching methods so as to cover the various examination objectives because using differentiated learning activities requires much more time. In such contexts, they may employ routine teaching strategies and thus, students are likely to describe them as boring. Moreover, when teachers are overloaded and immersed in high-stakes education, little time is left for them to learn about students’ weaknesses or issues and provide proper support (Ritt, Citation2016; Wellman, Citation2006). Russell et al. (Citation2005) found similar results in schools in the UAE, thus indicating the problems have been prevalent for more than a decade. Ibrahim and Al Taneiji (Citation2019; p. 112) related that a teacher in their study acknowledged, “I do what I can do.” Some revert to punishment to obtain results immediately. Punishment can lead to students hating school and resisting the system (Miller & Desberg, Citation2009).

Unlike qualitative data, the quantitative data revealed that students considered classroom practices to be a good predictor of their sense of belonging. This might be partially explained by students’ positive peer relationships inside and outside the classrooms. In accordance with Dehuff (Citation2013), we found that peer relationships are a significant predictor of sense of school belonging; third in our model after school safety and classroom practices. The qualitative data also showed that many of the students enjoyed going to school because of the presence of their friends. Similarly, the teachers believed that socializing with friends was a major reason students attended school. This was especially true for female students who may not have been allowed to go out with friends because of family traditions.

Having good friends at school helps adolescent students overcome problems (Newman et al., Citation2007), enhances their self-esteem (Schwartz et al., Citation2011, p. 27), and offsets negative feelings toward various school experiences (Booth & Gerard, Citation2014). However, the qualitative data revealed that sometimes peers engage in bullying and aggressive behavior, which may explain that peer relationships were a weak predictor of the students’ sense of belonging. When students fight, their feelings of security are affected adversely (Smokowski et al., Citation2014) and their sense of school belonging may be reduced (Kim, Citation2018). Schools and teachers are responsible for controlling any aggressive behavior at school and thus, they should be sensitive to signs of possible abuse to help students feel protected and secure.

In contrast to Uslu and Gizir (Citation2017) who found that parental involvement was an important factor for increasing student motivation and building a sense of school belonging, our model revealed that parental involvement was the weakest predictor of students’ sense of belonging. The qualitative data helped to explain this weak effect. According to the students, the relationship between their parents and them was limited to material and non-academic support, specifically, buying them things and hiring private tutors. Furthermore, it is normal for Emirati families to have a number of children, which as Davis-Kean (Citation2005) noted, may limit their time to interact and care for all their children. Additionally, Baker and Hourani (Citation2014) referred to parents’ narrow perception of the importance of their involvement with the school as many parents believe that the school and teachers are responsible for their children’s progress and satisfying their needs. Our data also revealed that female students were more critical of their relationship with their parents than their male counterparts. Emirati families are more protective of girls and thus, possibly impose more behavioral rules on them. Some female students preferred to stay in their rooms and distanced themselves from interacting with their parents. Cox et al. (Citation2011) noted that this was a normal occurrence as adolescents usually spend less time with their parents in their quest for independence. Cox et al. (Citation2011) further explained that the negative consequences of parent-adolescent relationships may affect adolescents’ ability to function and behave properly in school. Therefore, schools and teachers should learn more about students’ lives so as to assist them as they face daily academic and social challenges.

The quantitative and qualitative data revealed that the teachers and students perceived teacher-student relationships to be problematic and thus, they did not perceive it to be an indicator of a sense of school belonging even though the male students considered it a predictor. This is understandable in light of teachers’ changing roles. Farooqui (Citation2019) noted the teacher’s role revolves mostly around paperwork, accountability, and compliance and to a lesser extent, adherence to the principles of their profession. Moreover, Stone-Johnson (Citation2016) found that teaching for the test may cause a level of anxiety in teachers that thwarts their sensitivity to students’ rights and needs. Wellman (Citation2006) argued that this may lead them to ignore students’ characters because more importance is attached to grades than their sense of adventure and development. In the UAE, many teachers find it difficult to find the time to perform their non-academic responsibilities that are related to their students (Ibrahim & Al Taneiji , Citation2019; Farooqui, Citation2019). Instead of having teachers who provided support and care for students’ psychological safety (Miller & Desberg, Citation2009; Qin & Wan, Citation2015), who worked to gain the respect and trust of their students (Farrelly, Citation2013), who offset the negative effect of misbehaving peers (Demanet & Van Houtte, Citation2012), and who satisfied adolescents’ need to have a non-parental role model (Uslu & Gizir, Citation2017), the students in this study perceived their teachers non-caring and inconsiderate. We believe the teachers are driven to behave in such a manner because of limited time and the many requirements to which they must abide.

9. Conclusions

Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) Ecological System Model posits that issues at the micro-level cannot be remedied in the absence of governing policies and directions at the macro-level, particularly in centrally-governed educational systems. Central policies and directives should support this goal to enable schools and teachers to assist adolescent students. The results revealed that although students and teachers did not always agree on what promotes adolescent students’ sense of school belonging, they agreed on certain factors. Peer relationships and safety and school social practices predicted students’ sense of belonging. Therefore, it is important for schools and teachers to work on enhancing these factors in order to enjoy an increased sense of school belonging. We are of the view that belonging cannot be enhanced without positive and healthy student-teachers relationships and conducive classroom practices. The participants were critical of these factors and therefore, attention should be given to them. The findings also found a statistically significant negative predictive relationship between the teachers’ perceptions of parental involvement and students’ sense of belonging. It appears that high school adolescent students may require less parental involvement in their schools as they strive to be independent from their parents (Cox et al., Citation2011). It is recommended that further in-depth research be conducted to explore novel ways for parents to become involved that could increase adolescent students’ sense of school belonging.

10. Limitations and research recommendations

This study was limited to public schools in Al Ain city, UAE. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to all schools in the UAE. Furthermore, the sample of students was limited to grade 11 in secondary schools. Consequently, the results may not be representative of other students’ views in the public and private school systems in the country.

It is recommended that further studies be conducted to enhance understanding about the topic. In particular, it is imperative to conduct further studies on adolescent students-parents relationships, which explore cultural issues and differential treatment of male and female adolescents. The female students in the study related a relatively strong negative account of their school experiences and relationships with their parents. So, we suggest that female secondary schools and family experiences be explored in greater depth. It is also recommended that high- and low-stakes educational systems and how they may influence students’ sense of belonging, happiness, well-being, and psychosocial development be compared.

Ethical approval statement

I confirm the manuscript was approved by the Social Studies Ethics Committee at the United Arab Emirates University under approval number ERS-2018_5715.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Wafaa El Zaatari

Dr. Wafaa El Zaatari has a PhD from the UAE University in 2020 in Educational Leadership and Policy Sttudies and has a master’s degree in educational leadership. Her research interests include school belonging among adolescence, students’ safety at school, educational change, ethical practices at school. Email: [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8771-0387

Ali Ibrahim

Dr Ali Ibrahim is a Full Professor at the United Arab Emirates University, teaching and supervising students in the master and doctorate programmes at the College of Education. He holds a PhD in administrative and policy studies in education from the University of Pittsburgh, USA. His research interests include educational accountability, education policy studies, school leadership, higher education, education reform in the Middle East, and teacher professionalism in the Arab Gulf states. Email: [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1070-6256

References

- Aliyev, R., & Tunc, E. (2015). The investigation of primary school students’ perception of quality of school life and sense of belonging by different variables. Revista De Cercetare Si Interventie Sociala, 48, 164–19. http://www.rcis.ro/images/documente/rcis48_13.pdf

- Allen, K. A., & Bowles, T. (2012). Belonging as a guiding principle in the education of adolescents. Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 12, 108–119. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1002251.pdf

- Ashley, C. R. (2014). The relationship between after-school programs, sense of belonging, and positive relationships among middle school students [Doctoral dissertation]. Capella University. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis database. (UMI No.3631227)

- Ibrahim, A. & El Zaatari, W. (2020). The teacher–student relationship and adolescents’ sense of school belonging. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 25(1), 382-395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1660998

- Morgan, C. & Ibrahim, A. (2019). Configuring the low performing test user: PISA, TIMSS and the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Education Policy. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1635273

- Ibrahim, A., & Al Taneiji, S. (2019). Teacher satisfaction in Abu Dhabi schools: What the numbers did not say. Issues in Educational Research, 29(1), 106-122. http://iier.org.au/iier29/ibrahim.pdf

- Baker, F. S., & Hourani, R. B. (2014). The nature of parental involvement in the city of Abu Dhabi in a context of change: Nurturing mutually responsive practice. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 7(4), 186–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/EBS-05-2014-0023

- Booth, M. Z., & Gerard, J. M. (2014). Adolescents’ stage-environment fit in middle and high school: The relationship between students’ perceptions of their schools and themselves. Youth & Society, 46(6), 735–755. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X12451276

- Bouchard, K. L., & Berg, D. H. (2017). Students’ school belonging: Juxtaposing the perspectives of teachers and students in the late elementary school years (grades 4-8). The School Community Journal, 27(1), 107–136. https://www.adi.org/journal/2017ss/BouchardBergSpring2017.pdf

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1989). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta (Eds.), Annals of Child Development: Six theories of child development, revised formulations and Current issues (Vol. 6, pp. 187–249). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1993). Ecological models of human development. In M. Gauvain & M. Cole (Eds.), Readings on the development of children (2nd ed., pp. 37–43). Freeman.

- Cemalcilar, Z. (2010). Schools as socialization contexts: Understanding the impact of school climate factors on students sense of school belonging. Applied Psychology an International Review, 59(2), 243–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2009.00389.x

- Chhuon, V., & Wallace, T. L. (2014). Creating connectedness through being known: Fulfilling the need to belong in U.S. high schools. Youth & Society, 46(3), 379–401. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X11436188

- Cox, M. J., Wang, F., & Gustafsson, H. C. (2011). Family organization and adolescent development. In B. B. Brown & M. J. Prinstein (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 75–83). Academic Press, Elsevier Inc.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publication.

- Davis-Kean, P. E. (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 294–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.294

- Dehuff, P. A. (2013). Students’ wellbeing and sense of belonging: A qualitative study of relationships and interactions in a small school district [Doctoral dissertation]. Washington State University. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3587070)

- Demanet, J., & Van Houtte, M. (2012). School belonging and school misconduct: The differing role of teacher and peer attachment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(4), 499–514. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9674-2

- Eccles, J. S., Barber, B. L., Stone, M., & Hunt, J. (2003). Extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Journal of Social Issues, 59(4), 865–889. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0022-4537.2003.00095.x

- Faour, M. (2012). The Arab world’s education report card: School climate and citizenship skills. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Farooqui, M. (2019). UAE teachers ‘drowning’ in paperwork? ‘Unproductive’ clerical work rob UAE teachers of valuable teaching time. Gulf News. Al Nisr Publishing. https://gulfnews.com/uae/government/uae-teachers-drowning-in-paperwork-1.62926200

- Farrell, M. A. (2008). The relationship between extracurricular activities and sense of school belonging among Hispanic students [Doctoral dissertation]. Eastern Illinois University. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3317811)

- Farrelly, Y. (2013). The relationship and effect of sense of belonging, school climate, and self-esteem on student populations [Doctoral dissertation]. Hofstra University. Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses data base. (UMI No. 3592074)

- Fong Lam, U., Chen, W., Zhang, J., & Liang, T. (2015). It feels good to learn where I belong: School belonging, academic emotions, and academic achievement in adolescents. School Psychology International, 36(4), 393–409. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315589649

- Freiberg, H. J., & Stein, T. A. (1999). Measuring, improving and sustaining healthy learning environment. In H. J. Freiberg (Ed.), School climate: Measuring, improving and sustaining healthy learning environment (pp. 11–29). Falmer Press, Taylor and Francis Inc.

- Goodenow, C. (1993a). Classroom belonging among early adolescent students relationships to motivation and achievement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 13(1), 21–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431693013001002

- Goodenow, C. (1993b). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1<79::AID-PITS2310300113>3.0.CO;2-X

- Guerra, N. G., Williams, K. R., & Sadek, S. (2011). Understanding bullying and victimization during childhood and adolescence: A mixed methods study. Child Development, 82(1), 295–310. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2010.06.003

- Haugen, J. H., Wachter, C., & Wester, K. (2019). The need to belong: An exploration of belonging among urban middle school students. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 5(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2018.1556988

- Hayes, N., O’ Toole, L., & Halpenny, A. N. (2017). Introducing Bronfenbrenner: A guide for practitioner and students in early years education. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Huang, H. M., Xiao, L., & Huang, D. H. (2013). Students’ ratings of school climate and school belonging for understanding their effects and relationship of junior high schools in Taiwan. Global Journal of Human Social Science Linguistics & Education, 13 (3), 24–31. http://ir.dyu.edu.tw/handle/987654321/30715

- IEA TIMSS and PIRLS (2015). Students’ sense of school belonging. http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2015/international-results/wp-content/uploads/filebase/mathematics/6.-school-climate/6_11_math-students-sense-of-school-belonging-grade-8.pdf

- Johnson, L. S. (2009). School contexts and student belonging: A mixed methods study of in innovative high school. The School Community Journal, 19(1), 99–118.

- Kim, S. (2018). Peer victimization in the school context: A study of school climate and social identity processes [Doctoral dissertation]. Queen's University, Canada. https://qspace.library.queensu.ca/handle/1974/24830

- Krishnan, V. (2010, May). Early child development: A conceptual model. Presented at the Early Childhood Council Annual Conference 2010, “Valuing Care”, Christchurch Convention Center, Christchurch, New Zealand.

- Miller, J., & Desberg, P. (2009). Understanding and engaging adolescents. Corwin, a Sage company.

- National Association of School Psychologist (2013). Rethinking school safety: Communities and schools working together. https://www.nasponline.org/Documents/Research%20and%20Policy/Advocacy%20Resources/Rethinking_School_Safety_Key_Message.pdf

- National School Climate Center (2011). National school climate standards: Benchmarks to promote effective teaching, learning and comprehensive school improvement. https://www.schoolclimate.org/themes/schoolclimate/assets/pdf/policy/school-climate-standards.pdf

- Newman, B. M., Lohman, B. J., & Newman, P. R. (2007). Peer group membership and a sense of belonging: Their relationship to adolescent behavior problems. Adolescence, 42(166), 241–263. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.uaeu.ac.ae/docview/195945688?accountid=62373

- Qin, Y., & Wan, X. (2015, April). Review of school belonging. Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Science and Technology Education, China. Atlantis Press. 978-94-62520-60-8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2991/icsste-15.2015.213

- Ritt, M. (2016). The impact of high stakes testing on the learning environment [Master thesis]. St. Catherine University. https://sophia.stkate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1660&context=msw_papers

- Russell, A., Coughlin, C., El Walily, M., & Al Amri, M. (2005). Youth in the United Arab Emirates: Perceptions of problems and needs for a successful transition to adulthood. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 12(3), 189–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2005.9747952

- Sánchez, B., Colón, Y., & Esparza, P. (2005). The role of sense of school belonging and gender in the academic adjustment of Latino adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(6), 619–628. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-8950-4

- Schwartz, D., Mayeux, L., & Harper, J. (2011). Bully/victim problems during adolescence. In B. B. Brown & M. J. Prinstein (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 25–34). Academic Press, Elsevier Inc.

- Smith, M. L. (2015). School climate, early adolescent development, and identity: Associations with adjustment outcomes [Doctoral dissertation]. West Virginia University. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3718568)

- Smokowski, P. R., Evans, C. B. R., & Cotter, K. L. (2014). The differential impacts of episodic, chronic, and cumulative physical bullying and cyberbullying: The effects of victimization on the school experiences, social support, and mental health of rural adolescents. Violence and Victims, 29(6), 1029–1046. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-13-00076

- Stone-Johnson, C. (2016). Intensification and isolation: Alienated teaching and collaborative professional relationships in the accountability context. Journal of Educational Change, 17(1), 29–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-015-9255-3

- UAE Cabinet (n.d.). National Agenda. Accessed on 17 Dec 2018. https://uaecabinet.ae/en/national-agenda

- Uslu, F., & Gizir, S. (2017). School belonging of adolescents: The role of teacher- student relationships, peer relationships and family involvement. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 17(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2017.1.0104

- Wallace, T. L., Ye, F., & Chhuon, V. (2012). Subdimensions of adolescent belonging in high school. Applied Developmental Science, 16(3), 122–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2012.695256

- Wang, M., & Sheikh‐Khalil, S. (2014). Does parental involvement matter for student achievement and mental health in high school? Child Development, 85(2), 610–625. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12153

- Warner, R., & Burton, G. J. (2017). A fertile oasis: The current state of education in the UAE. Mohamed bin Rashid School of Government. https://www.mbrsg.ae/getattachment/658fdafb-673d-4864-9ce1-881aaccd08e2/A-Fertile-OASIS-The-current-state-of-Education-in

- Weissbourd, R., Bouffard, S. M., & Jones, S. M. (2013). School climate and moral and social development. In T. Dary & T. Pickeral (Eds.), School climate: Practices for implementation and sustainability. A school climate practice brief (pp. 1–5). National School Climate Centre.

- Wellman, N. D. (2006). Teacher voices of an ethic of care: A narrative study of high stakes testing impact on caring [Doctoral dissertation]. Stephen F. Austin State University. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3221723)