Abstract

While research exists on literacy focused on children in formal school, there is little evidence of how adult literacy is depicted in social practice from the perspective of what adults do in daily life. This study investigates the effectiveness of literacy teaching design integrating local culture discourse and practice to enhance the reading skills of adults in Indonesia. One hundred participants from underdeveloped areas aged 25–50 contributed to the learning process for twelve lesson units. We elicited data by using two instruments, namely multiple-choice questions and interviews. The statistical analysis showed that instructional design profoundly affected the improvement of reading skills. The thematic analysis showed how participants evaluated the literacy teaching design as enriching knowledge, sharing understanding among participants and motivating them to improve their life skills. This study will be useful to teachers who are seeking cognitive and practical instructions to promote reading skills in the classroom.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Literacy is a fundamental factor to support people in life because it includes all basic abilities such as reading, talking, and speaking. In the context of social practice, literacy depends on social context, which varies for each individual. This means that literacy leads to social practices whereby literate people can interact effectively both in informal institutions and outside them. This situation is interesting because it places literacy not only in its own nature but also in social practice. Research on literacy that places it in the context of people’s lives in rural areas, with local cultural content, will greatly help the community to develop life skills because the content used is related to people’s daily lives. The findings of this study can provide suggestions for learning designs and programmes to improve literacy skills, as well as improve life skills, especially for people living in rural areas.

1. Introduction

Literacy is important not only for children in formal school but also for adults in society (Gumilar, Citation2020; Theodotou, Citation2017). While research exists on literacy focused on children in formal school (e.g., Theodotou, Citation2017), there is little evidence of how adult literacy is depicted in social practice from the perspective of what adults do in daily life. The social practice perspective views literacy as one aspect of social activity that is practised by human agents with the capacity to form their own goals, but which also acts in a particular social context to determine how literacy is used and that gives it certain values and meanings (Kawatoko, Citation1995; Kell, Citation2008). This perspective challenges scholars to look outside the literacy class and see how literacy features in people’s daily lives. This view of social practice encourages a new awareness of how basic literacy skills are applied by society.

Approaching literacy as a social practice, it is essential to find meaningful ways to help literacy practitioners to support adult literacy skills, including reading skills. Adapting local culture and life skills to literacy skills, such as reading beliefs, can facilitate the improvement of adult literacy. Empirical evidence shows that culture determines people’s level of literacy, including their reading skill (Bedard et al., Citation2011; Trueba, 1900). This means that local culture can be used to support people in enhancing their literacy.

In the Indonesian context, there are still adults with low literacy skills, especially in underdeveloped areas. The Indonesian government itself is trying to reduce the number of people categorised as having low literacy by implementing various programmes. One of these is a literacy assistance programme focused on underdeveloped areas and implemented through a community service programme run by each university in Indonesia. The programme aims to encourage the improvement of literacy skills, particularly reading skills. Researchers know that literacy can be improved through the use of culture that develops where people live. Therefore, this study advances the evidence related to the integration of local culture into literacy teaching for teaching reading skills to disadvantaged groups in Indonesia. Through the community service programme facilitated by one public university in Indonesia, we performed literacy teaching integrating local culture in the form of discourse and practice to enhance reading skills.

2. Literature review

2.1. Literacy as social practice

The ability of people to communicate verbally and non-verbally, as well as to read and write, determines the ways people live in a community (Theodotou, Citation2017). Literacy is thus a fundamental factor in supporting people because it covers all these abilities. Literacy becomes a social practice through which the literate person can interact effectively in formal institutions and beyond (Sørvik & Mork, Citation2015).

As a social practice, literacy depends on social context, which varies for each individual. This situation is interesting because it places literacy not only in its own nature but also in social practice. Literacy practice can be found at home or in the community (Heath, Citation1983; Theodotou, Citation2017). In the context of social practice, there are two essential factors contributing to the development of literacy: practices and events. Literacy events refer to diverse activities connected to literacy (Barton, Citation2007). For instance, people reading the ingredients on fast food packaging is an example of a literacy event. Literacy practices lead to how people utilize literacy events through particular actions; this situation is heavily affected by social and cultural contexts (Papen, Citation2006; Theodotou, Citation2017). For example, a child learns to write when she/he reads the ingredients of fast food. These two types of literacy are useful to build knowledge because they are similar to what people do in their daily activities. This means that to improve adult literacy, two types of literacy should be integrated into the learning process.

In adult settings, literacy as a social practice can be used to develop skills. The reason for this is that adults frequently participate in local and situated social practices that involve texts (Barton & Hamilton, Citation1998; Sørvik & Mork, Citation2015). The development of adult literacy through social practice can be conducted in several ways. A previous study (Prins, Citation2017), conducted in rural Ireland, raised the topic of community literacy skills using digital storytelling in adult education. Literacy as a social practice was also explored in the context of health literacy in Suriname (Diemer et al., Citation2017). The results of this study were used as evaluation materials to improve health literacy. Another study that looked at literacy as a social practice in a rural area investigated mosque-based literacy campaigns from a sociocultural perspective in Morocco (Erguig, Citation2017). This evidence indicates that texts can be used in different social situations to improve the literacy of rural people. Doing so indirectly affects the progress of a country.

2.2. Culture as an approach to literacy teaching

There are many definitions of culture. One of these is related to concepts, beliefs and principles of action attributed successfully to a society (Goodenough, Citation1976; Trueba, Citation1990). Culture, therefore, is an identity attached to society as part of activities or experiences of daily life. In other words, because culture connects to what people do in life, it has a connection to sociocultural knowledge. Interestingly, literacy plays the role of a symbolic system dynamically altering the way people communicate (Trueba, Citation1990). Literacy is thus technically responsible for pushing people’s ability to read and write, which requires a sociocultural environment. This means that the acquisition of literacy is determined by culture.

Furthermore, in the context of literacy teaching, culture and texts correlate with each other (Li, Citation2011). Previous research revealed that teaching material and content that present culturally familiar materials have a strong effect on students’ reading motivation and achievement (August et al., Citation2006; Li, Citation2011). In addition, popular texts, which present superhero stories, news media, and digital media, can improve students’ attention towards literacy teaching. Some researchers who focus on literacy argue that academic literacy and critical consciousness can also be promoted by integrating popular cultural texts into school literacy (Dyson, Citation1997; Li, Citation2011; Moje, Citation2002; Morrell & Duncan-Andrade, Citation2002). For instance, Dyson (Citation1997) investigated how the use of popular culture in the unofficial and official literacy curriculum was implemented in the teaching of young students aged 7–9 years. The study revealed that the representation of the state of social play by students could reveal several learnt values, such as the ability to mediate and negotiate social relations. On this basis, Dyson argued that various cultural materials afford value for institutional engagement and feedback in literacy learning.

Previous studies have consistently shown that culture can be integrated into literacy teaching, particularly for reading skills. In this context, adults’ experiences of their daily activities can be transformed into a discourse for reading materials. This is a form of cultural translation from daily experience to literacy practice (Li, Citation2011). Moreover, teaching literacy should not be limited to attaining good instruction but should adopt a strategy that is relevant to the needs of adults (Au, Citation2007; Li, Citation2011). In other words, the texts developed as teaching materials should not be specific to a certain field but should be related to the background of the people who are learning reading. This study, therefore, uses the local culture of people and their daily activities as teaching materials for adult literacy classes in underdeveloped areas.

3. The context of the study

The literacy teaching design developed in this study is based on a geographical analysis of community needs. The design is constructed according to local culture, which is connected to the skills that people require to solve problems in daily life. Researchers highlight that reading is a basic skill that must be mastered by people in underdeveloped areas. The form of local culture here is the ability to behave in an adaptive and positive manner, which enables a person to respond to the needs and face the challenges of everyday life (Kell, Citation2008; Lee-Hammond & McConney, Citation2017; López, Citation2014). These skills allow a person to face life’s problems without feeling depressed, then proactively and creatively find solutions so that they are finally able to overcome them. Put simply, we integrated local culture in the form of daily experiences into literacy training to teach reading skills. The literacy teaching phases can be observed in .

Table 1. The literacy teaching design involving tutor’s and participants’ activities

In this literacy teaching design, we divided the phases into two parts. First, phases 1 to 4 focus on teaching reading skills with tutors presenting a discourse related to local culture that participants commonly experience in daily activity. For instance, the first unit of teaching literacy is to provide a discourse on how to make compost from animal manure. All the participants are taught to read and comprehend this information. The interaction between tutors and participants is intense, which helps the participants to understand the context of the information and knowledge provided. Second, phases 5 and 6 provide an activity to create a product based on procedures found in the teaching materials. For instance, all the participants actively and collaboratively make compost based on the skills provided in the discourse. In this part, interaction among participants occurred enthusiastically. Based on the literacy teaching design developed and the activities conducted by the participants, we investigated the effects of this intervention on reading skills. We develop two research questions:

Can a literacy teaching design integrating local culture/life skills activities enhance reading skills?

How did participants evaluate the literacy teaching design in terms of enhancing their life skills to support daily activities?

4. Method

This study used a pre-experimental embedded case study method (Cohen et al., Citation2017). The use of the literacy teaching design integrating local culture/life skills aims to improve people’s literacy skills, particularly their reading skills. We take advantage of the use of this literacy teaching design in the context of the social change that has occurred in rural society (Robinson-Pant, Citation2008; Sayilan & Yildiz, Citation2009). Participants came from the rural areas of the West Java Province, Indonesia. The selection process took place in several stages. First, we collaborated with the local government of one village to learn the degree of education and the economic features of the area. Based on this data, we verified that there was a significantly low level of education and that the economy was dominated by farmers and people without permanent jobs. There were 274 people categorised as having a low degree of education and low literacy skills, particularly in reading skills; some people had graduated from elementary school (63.6%) while some from junior-high school (36.4%). Second, along with the local government, we invited all these people to join the programme we had created. One hundred and forty-five people came to the one-hour session to hear our explanation of the programme. At the end of this session, they were offered the chance to fill out a letter of commitment. One hundred people committed to attending 12 lessons. They were aged from 25 to 50; 70% were male and 30% female. In accordance with the objectives of this study, data collection was carried out with all the participants.

The tutors contributing to this study were 10 undergraduate students. They were third-year students from different courses, such as science and language. They joined the programme because the university had a mandatory course for all third-year students to volunteer in the local community before they could be admitted to year four. The students were trained to comprehend the teaching materials over one month before acting as tutors.

4.1. Procedures

We enacted the literacy teaching design in the course for 12 lesson units. Each unit lasted three hours during which the participants interacted among themselves and with the tutors as part of the learning process. The lessons were held on Saturdays from 09.00 am to 12.00 pm. We divided each unit into two parts. First, the tutors taught the participants to comprehend the discourse related to local culture or life skills included in phases 1 to 4 of the literacy teaching design. During this time, both participants and tutors were engaged in creating collaborative learning using the teaching materials developed. Second, the instructional design provided real activities during which participants collaborated or made a product based on what they read; this involved phases 5 and 6 of the literacy teaching design. The tutors facilitated the process with several materials required for making the products. For each unit of the course, the participants made a different product; hence, after finishing the course they had carried out 12 different tasks (see Appendix A) that supported their daily activities as farmers and other kinds of workers.

4.2. Instruments

We developed two instruments related to the literacy teaching design. The first one measured the reading skills in comprehending discourses. Several steps were involved in developing this instrument. First, we chose six themes (discourses) related to the lesson units learnt by the participants. Second, we developed each theme or discourse as an essay consisting of 300–500 words. Third, we formulated five questions for each theme. Fourth, we divided the six themes into two parts, with each part consisting of three discourses. The first three discourses, or fifteen questions, focused on the competence in reading information literally while the others on the competence in reading information critically. The questions were multiple-choice ones, which required participants to have read the discourse earlier. Fifth, the instrument was tested on 30 second-year university students from the department of Indonesian language to measure its validity and reliability. Because the instrument included multiple choices, we used the Pearson product-moment correlation to count its validity and the split-half method to measure its reliability. The reason for using the Pearson correlation is that it is a simple way to assess the degree of the linear correlation among questions (Puth et al., Citation2014). Based on the analysis, the average Pearson correlation coefficient for all the questions was 0.72. Furthermore, the use of the split-half method for the reliability of the instrument aimed to investigate the consistency of the instrument, as we decided not to take test-retest. We found the degree of reliability of the instrument to be 0.67. This instrument was used in the pre-test and post-test to measure and map participants’ level of reading skills; it used the Indonesian language as the mother tongue of the participants.

The second instrument consisted of interview questions. These were used to elicit participants’ perceptions of the effect of the literacy teaching design on supporting their life skills. Five semi-structured interview questions (see Appendix B) were put to 10 participants. Each interview lasted almost half an hour and was conducted after participants finished the course. The interview was carried out in the mother tongue of the participant so that they could respond easily.

4.3. Data sources and analysis

One hundred participants completed a reading skills test. They used the same instrument, which consisted of 30 multiple choices, for pre-test and post-test. Every right answer was scored one (1) while a wrong answer was scored zero (0), so the maximum possible score was 30 (similar to 100 on a scale of 0 to 100). We divided participants’ scores into 4 types to code their level of reading skills, as shown in . All the responses were coded and entered into SPSS. Participants’ scores pre- and post-test were compared using paired t-test. To consider the effectiveness of the literacy teaching design, we also measured effect size (d).

Table 2. Reading skill levels

In addition, the interview data were analysed using thematic analysis (Creswell, Citation2012). At the beginning, the data were coded to allow initial codes to emerge. The data were then grouped to generate categories and sub-categories (see ). Finally, the underlying categories were sorted into three themes related to the enactment of the literacy teaching design. The three themes are enriching knowledge, sharing understanding among participants, and motivating to improve life skills.

Table 3. An example of coding

4.4. Ethical statement

All participants were obliged to provide their informed consent before joining the program. The research protocol was internally approved by the Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia.

5. Result and findings

5.1. Level of reading skills and its enhancement

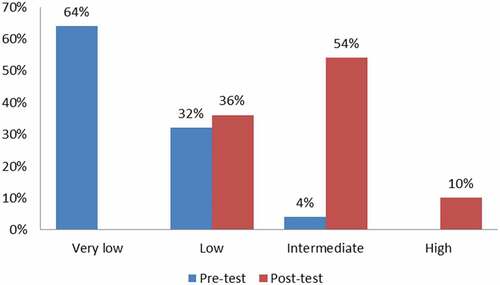

Based on the pre- and post-test scores, we mapped participants’ reading skills before and after the enactment of the literacy teaching design integrating local culture discourse and activities. shows the level of reading skills for the 100 participants. The category “very low” is dominant; 64% of all participants were in this category before the intervention began. In contrast, after the intervention, no one was in this category. In the low category, there were similar results before and after the intervention, 32% and 36%, respectively. Only 4% of participants were in the intermediate category before the instructional design was implemented, while the figure rose to 54% afterwards. Only one-tenth of participants had high reading skills after the intervention. Overall, then, there was an improvement in the reading skills of those who were engaged in the instructional design integrating discourses and practices of local culture.

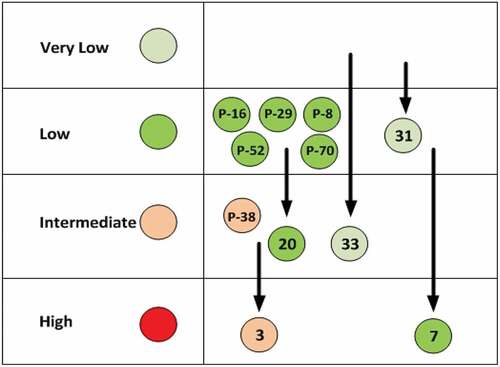

We also carried out a meta-analysis by observing each level of reading skills. shows the number of participants, the averages and the gain scores for each category. Interestingly, all the participants in the very low category moved to a higher category, such as low and intermediate. Similarly, participants who were in the low and intermediate categories also improved their reading skills to intermediate and high levels. Furthermore, the gain scores depict high enhancement.

Table 4. Average scores for each category of reading skills

Not all the participants in the intermediate and low categories moved to higher categories. A micro-analysis reveals that several participants who started in the low and intermediate categories remained in the same categories. For instance, participant 38 (P-38) is categorised as intermediate both in the pre-test and post-test scores. This means that the participant had the same level even though their score improved and that there was no alteration of reading competence. The same situation occurred to five participants in the low category (see ); they did not improve in terms of reading skills levels but they improved their scores. By considering the representation of each category position, we found that the shift from very low to intermediate was the same as that from low to intermediate. This indicates a change in reading skills capability because the intermediate and high categories provide reading skills to make sense of the texts.

In addition, to understand a change or enhancement in reading skill scores, we calculated the significance of the mean difference between pre-test and post-test scores. The normality test using Kolmogorov Smirnov shows that both pre-test (x ̅pre-test = 20.60; zpre-test = 1.079; p = 0.195; p > 0.05) and post-test (x ̅post-test = 50.03; zpost-test = 1.193; p = 0.116; p > 0.05) scores were normally distributed. We then used a paired student test (paired t-test) to examine whether the mean difference between pre-test and post-test scores was significantly different. The results of the statistical analysis using SPSS found that there is a significant difference between the averages of the pre-test and the post-test (std. Deviation = 12.57; t = −25.78; df = 99; p = 0.000; p < 0.001). Furthermore, the effect size was large (d = 1.2). This means that the implementation of the literacy teaching design enhanced participants’ reading skills to comprehend the provided discourse.

5.2. Participants’ perspectives on the use of the literacy teaching design

Regarding the interview data, we coded three themes related to participants’ evaluation of the literacy teaching design. The themes are: enriching knowledge, sharing understanding among participants, and motivating to improve life skills.

5.2.1. Enriching knowledge

Participants thought that literacy teaching integrating local culture discourse and practice could enrich their knowledge. They viewed the discourses and practices provided in the learning process as familiar because they were close to their daily activities; the discourses frequently opened new perspectives to improve their daily earning activities. For instance, the optimisation of the economic products created from cassava in lesson unit-4 was an important discourse for enriching their knowledge to yield unique local products that could be sold not only in the village but also in urban areas. As several participants stated:

Yes … The learning process truly shared worthwhile values to improve my reading skill but I think not much … I graduated from primary school and it is difficult to learn … The important thing for me was that I learnt new things, particularly when I had to do the practical activities or make products … For instance, making chips from cassava. I really liked this (P-70).

Yes … It helped me to improve my competence to read … I am 25 years old and I am still young … This competence will help me to open up opportunities and increase information related to my daily activities (P-89).

5.2.2. Sharing understanding among participants

Participants commented positively on the fact that they were trained to share their understanding among other participants. The context of practice in the literacy teaching design urges all participants to contribute directly to a small group; they have to create the products from what they read. The participants said that they had to share their understanding of the ways the products are made based on the correct procedures. This situation is not easy because sometimes the participants in a group have different background experiences and ages; the sharing of understanding frequently takes a long time. This is evident in the interview scripts:

My emotional feeling is too complex. I must understand another skill in the group in the context of the practical activities for making a product. Sometimes, the activity is boring because not all the participants have the same understanding, especially the old. I must share my understanding to embark on the practical activities (P-90).

In practising the knowledge that we discussed, my friends and I in my group must have the same understanding of the procedure … For instance, when we made compost, we had to make sure that the procedure was correct (P-9).

5.2.3. Motivating to improve life skills

There is a positive nuance provided by literacy teaching design when implemented with people in underdeveloped areas. This is because both cognitive and practical activities motivate people to improve the skills required to support their lives. The use of the teaching materials opened participants’ minds to modify the product that they have known in daily life. For instance, in unit-4, the participants learnt to read using a discourse on how to make chips from cassava. This activity is known in their village but they can vary the product by widening the types of chips based on their level of spiciness. This information was obtained by reading the teaching materials and practising them during the learning process.

Yes … The information from the reading materials enhanced my knowledge to develop a certain product. I never knew that cassava chips could be varied based on the level of spiciness. I think many local products in this village can be made unique. The key is the capacity to read information to obtain new knowledge; I believe this will improve the life skills of all the groups in the village (P-2).

In addition, the participants argued that literacy teaching integrating local culture discourse and practice helps groups in undeveloped areas to be more creative. The reason for this is that the information provided in the reading materials combines a new approach to develop the local products commonly manufactured in the village. In other words, the activities contribute to the identity development of the society; they indirectly build motivation to have a goal and learn the values that people want to acquire (Guthrie et al., Citation1996; Pintrich & Schrauben, Citation1992).

6. Discussion

We focused on two research questions. First, whether the enactment of a literacy teaching design integrating local culture discourse and practice is effective in enhancing reading skills. Second, how participants perceived this design in terms of its usefulness in enhancing their life skills to underpin daily life.

The findings show that the literacy teaching design alters reading competence. The evidence to support this finding is the existence of six phases in the literacy teaching design encompassing two types of literacy. The six phases can be divided into two types of literacy: literacy practice and literacy events. Phases 1 to 4 function as a literacy event in which the participants directly learn to comprehend texts related to daily activities and experiences (Barton, Citation2007). The characteristics of the textual discourse, which are familiar to participants, strengthen the cognitive activities and help them understand the meaning of what they read. This affects participants’ motivation to read and achieve (Goldenberg et al., Citation2006). Phases 5 and 6 are related to literacy practices, in that people used what they had read to create a product and this was influenced by their daily sociocultural interactions (Heath, Citation1983; Papen, Citation2006). In this practical activity, all the participants were engaged in sharing personal experiences and were intensely connected to other participants in the small groups. This activity had a direct positive effect on reading skills because people had to share their understanding of how a product should be manufactured. We thus argue that integrating local culture in literacy teaching helps to share sociocultural values that strengthen the literacy practice itself (Li, Citation2011; Teale & Sulzby, Citation1986). These elements explain why the literacy teaching design in question is effective in improving reading skills in underdeveloped areas.

More importantly, the micro-analysis shows that there was a shift from reading information literally to doing so critically. The two reasons for this are related to the characteristics of the reading materials provided and the cognitive activities in the literacy teaching. First, the reading materials provided not only local cultural discourse but also the problems related to interpreting the information critically. This plays a key role in supporting the effort to make sense of the texts in a discourse. This activity occurred regularly during the 12 lessons. Second, phase 3 in the literacy teaching design specifically dealt with the creation of meaning. There was a collaborative effort between tutor and participants to create meaning in the context of cultural experiences; this directly affects participants’ competence in interpreting information critically. We argue that these reasons explain why there was a significant shift from reading texts literally to interpreting them critically.

We found that the use of a literacy teaching design integrating local culture discourse and practice contributes to enriching knowledge, sharing understanding among participants and motivating them to improve their life skills. This instructional design helps participants to develop new ways of improving local products. In addition, when conducting practical activities to create a product, there was also sharing of understanding between old and young participants. This means that the learning process shares worthwhile values. Lastly, there was a positive tone towards the instructional design because it underpinned the identity development of the society; it indirectly built motivation to have a goal and learn the values that people want to acquire (Guthrie et al., Citation1996; Pintrich & Schrauben, Citation1992). This evidence shows how integrating local cultural discourse and practice can address the problem of adult literacy in remote or underdeveloped areas.

7. Conclusion and implication

In conclusion, this study has presented evidence on how literacy teaching integrating local culture discourse and practices helps adults to improve their reading competence. The researchers highlight the importance of combining cognitive and practical activities to underpin the improvement of reading skills. In addition, the study also investigated how adults evaluated the use of cognitive and practical activities depicted in the six phases of literacy teaching in terms of enriching knowledge, sharing understanding among participants and motivating them to improve their life skills. Furthermore, the study has made an essential contribution to explaining how the development of an instructional design that integrates local culture can be a tool for enhancing the literal and critical comprehension of information.

This study has also some pedagogical implications. The integration of local culture as a form of social practice can be developed to support the reading skills of adults. Through pre-experimental research, we have documented that there is a profound effect when daily activities are integrated into literacy teaching in underdeveloped societies. We believe that this literacy teaching design can be brought to a formal classroom where the students can be engaged in mastering reading skills. This study, therefore, is useful for teachers who are seeking cognitive and practical instructions that promote reading skills in the classroom.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daris Hadianto

Daris Hadianto is a lecturer at the Department of Mapping Survey and Geographic Information, Faculty of Social and Education, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia. The author studied at the Department of Indonesian Language Education in Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia with a focus on literacy. In addition as the Indonesian Language of Education lecturer, the author is active in the field of Indonesian for foreign speakers as a lecturer and researcher. Several research projects and published articles have focused on literacy, reading, and Indonesian as a second language. The author has research interests in the fields of academic literacy, critical literacy, reading comprehension, Indonesian language education, and Indonesian as a second language.

References

- Au, K. H. (2007). Culturally responsive instruction: application to multiethnic classrooms. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 2(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15544800701343562

- August, D., Goldenberg, C., & Rueda, R., et al. (2006). Native American children and youth: culture, language, and literacy. Journal of American Indian Education, 45(3), 24–37.

- Barton, D., & Hamilton, M. (1998). Local literacies: Reading and writing in one community. Routledge.

- Barton, D. (2007). Literacy: An Introduction to the Ecology of Written Language. Blackwell.

- Bedard, C., Horn, L. V., & Garcia, V. M., et al. (2011, July). The impact of culture on literacy. The Educational Forum (Vol. 75, pp. 244–258). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2011.577522

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K., et al. (2017). Research methods in education (7th ed, pp. 30–31). Routledge Falmer.

- Creswell, J. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed). Pearson.

- Diemer, F. S., Haan, Y. C., Nannan Panday, R. V., van Montfrans, G. A., Oehlers, G. P., & Brewster, L. M., et al. (2017). Health literacy in suriname. Social Work in Health Care, 56(4), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2016.1277823

- Dyson, A. H. (1997). Writing superheroes: Contemporary childhood, popular culture, and classroom literacy. Teachers College Press.

- Erguig, R. (2017). The mosques-based literacy campaign in Morocco: A socio-cultural perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 49(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2017.1283755

- Goldenberg, C., Rueda, R. S., & August, D., et al. (2006). Synthesis: sociocultural contexts and literacy development. In D. August & T. Shanahan (Eds.), Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on language-minority children and youth. 249–268. Erlbaum.

- Goodenough, W. H. (1976). Multiculturalism as the normal human experience. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 71, 4–7. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.1976.7.4.05x1652n

- Gumilar, S. (2020, December 16). Review of global developments in literacy research for science education: Edited by Kok-Sing Tang and Kristina Danielson. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 41(1). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/10.1080

- Guthrie, J. T., McGough, K., Bennett, L., & Rice, M. E., et al. (1996). Concept-oriented reading instruction: An integrated curriculum to develop motivations and strategies for reading. In L. Baker, P. Afflerbach, & D. Reinking (Eds.), Developing engaged readers in school and home communities (pp. 165–190). Erlbaum.

- Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with Words, Language, Life and Work in Communities and Classrooms. University of Cambridge.

- Kawatoko, Y. (1995). Social rules in practice:“Legal” literacy practice in Nepalese agricultural village communities. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 2(4), 258–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039509524705

- Kell, C. (2008). “Making things happen”: literacy and agency in housing struggles in South Africa. Journal of Development Studies, 44(6), 892–912. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380802058263

- Lee-Hammond, L., & McConney, A. (2017). The impact of village-based kindergarten on early literacy, numeracy, and school attendance in Solomon Islands. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(4), 541–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2016.1155256

- Li, G. (2011). The Role of Culture in Literacy, Learning, and Teaching. In Kamil et al. Handbook of Reading Research, Volume IV (pp. 541–564). Routledge.

- López, M. (2014). Bilingual Research Journal?: The Journal of the National Association for Bilingual Education Immigrant Students and Literacy, 31(1–2), 37–41. Reading, Writing, and Remembering, Gerald Campano. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235880802640847

- Moje, E. B. (2002). But where are the youth? integrating youth culture into literacy theory. Educational Theory, 52(1), 97–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2002.00097.x

- Morrell, E., & Duncan-Andrade, J. (2002). Toward a critical classroom discourse: promoting academic literacy through engaging hip-hop culture with urban youth. English Journal, 91(6), 88–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/821822

- Papen, U. (2006). Literacy and globalization: Reading and writing in times of social and cultural change. Routledge.

- Pintrich, P. R., & Schrauben, B. (1992). Students’ motivational beliefs and their cognitive engagement in classroom academic tasks. In D. H. Schunk & J. L. Meece (Eds.), Student perceptions in the classroom (pp. 149–183). Erlbaum.

- Prins, E. (2017). Digital storytelling in adult education and family literacy: A case study from rural Ireland. Learning, Media and Technology, 42(3), 308–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2016.1154075

- Puth, M. T., Neuhäuser, M., & Ruxton, G. D., et al. (2014). Effective use of pearson’s product–moment correlation coefficient. Animal Behaviour, 93(1–7), 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.05.003

- Robinson-Pant, A. (2008). “Why literacy matters”: exploring a policy perspective on literacies, identities and social change. Journal of Development Studies, 44(6), 779–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380802057711

- Sayilan, F., & Yildiz, A. (2009). The historical and political context of adult literacy in Turkey. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 28(6), 735–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370903293203

- Sørvik, G. O., & Mork, S. M. (2015). Scientific literacy as social practice: implications for reading and writing in science classrooms. Nordic Studies in Science Education, 11(3), 268–281. https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.987

- Teale, W. H., & Sulzby, E. (Eds.). (1986). Emergent literacy: Writing and reading. Ablex.

- Theodotou, E. (2017). Literacy as a social practice in the early years and the effects of the arts: A case study. International Journal of Early Years Education, 25(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2017.1291332

- Trueba, H. T. (1990). The role of culture in literacy acquisition: an interdisciplinary approach to qualitative research. Internation Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 3(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839900030101

Appendix A:

List of Reading Material Themes for Each Lesson Unit

Appendix B:

List of interview questions

Do you think the literacy teaching design implemented in the learning process is useful to change your reading skills? Why

Do you think the literacy teaching design implemented in the learning process is useful to train the life skills required in daily activities? Why

Do you think the literacy teaching design implemented in the learning process is useful to improve your daily earning activities? Why

How are the difficulties faced during conducting the learning process emphasizing local culture discourse and practice?

How are your emotional feelings during conducting the learning process to improve your reading skills?