Abstract

Building teachers’ professional capital as a mix of human, social and decisional capital is a prominent strategy to transform the teaching profession and ensure quality education. However, a scant of evidence is available about the determinants of professional capital development in Ethiopia. This study examined the link between engagement in diverse professional learning activities, job satisfaction, and teacher professional capital development using data from 302 primary school teachers of Banja Woreda, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. SEM analysis suggested that teacher engagement in individual professional learning activities and job satisfaction directly influences professional capital development, and teacher engagement in collaborative professional learning activities indirectly influences professional capital development through job satisfaction. Mediation analysis revealed that teacher job satisfaction partially mediates the effect of engagement in individual professional learning activities and fully mediates the effect of engagement in collaborative professional learning activities on teachers’ professional capital development.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Boosting teacher professional capital in every school is an indispensable strategy to transform the whole education system. As the result of SEM analysis revealed, teachers’ level of engagement in various individual and collaborative professional learning activities and their job satisfaction have either direct or indirect positive influences in boosting their professional capital development—their pedagogy and subject matter knowledge. Teachers’ job satisfaction also signifies a positive direct effect on their professional capital development and mediates the effects of teachers’ engagement in professional learning activities on their professional capital development. Hence, uplifting teachers’ job satisfaction by addressing their regularly affirmed human and professional needs as well as upsurging teachers’ individual and collaborative engagement in their professional learning should be the milestone for those actors who are involving at all levels of the education sector.

1. Introduction

Teachers bear a significant amount of responsibility for developing a well-equipped workforce by offering quality education to fulfill the changing demands of the knowledge economy. As a result, building teachers’ professional capital is becoming increasingly acknowledged as a critical method for ensuring quality education (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012, Citation2013; Reichenberg & Andreassen, Citation2018; Uba & Chinonyerem, Citation2017). Professional capital was first coined by Hargreaves and Fullan (Citation2012) in the context of the teaching profession. It is characterized as an integrative function of human, social, and decisional capital (Fullan, Citation2016; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012, Citation2013).

Human capital as one dimension of professional capital refers to teachers’ knowledge, skills, abilities, and experiences (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012; Reichenberg & Andreassen, Citation2018; Uba & Chinonyerem, Citation2017). As the second dimension of professional capital, social capital refers to a group of instructors’ professional assets, abilities, and certifications (Watts, Citation2018). Building individual and collective knowledge and skills to improve practice and student learning is what social capital is all about (Fullan et al., Citation2015). Positive interpersonal and professional relationships among teachers can help to build social capital (Fullan, Citation2016; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012).

The decisional capital of teachers is the third dimension of their professional capital. This dimension refers to a teacher’s ability to make professional discretionary judgments, as well as individual and group decision-making abilities (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). Resources of knowledge, intelligence, and energy required to put human and social capital to productive use are referred to as decisional capital (Fullan, Citation2016). In general, decisional capital refers to teachers’ ability to make the greatest choices and make advantageous decisions in professional activities (Fullan, Citation2016; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012).

Promoting teachers’ engagement in continuous professional learning and development activities is a vital strategy to boost teachers’ professional capital (Fullan & Hargreaves, Citation2016; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012; Nolan & Molla, Citation2017). Accordingly, many countries around the world, including Ethiopia, have developed teacher professional learning and development programs in keeping with this approach, regardless of their economic status (International Labour Organization (ILO), Citation2012, Ministry of Education (MoE), Citation2004; OECD, Citation2014; United Nations, Citation2016). Therefore, teachers should make a concerted effort to participate in individual and collaborative professional learning and development activities designed to help them develop their professional capital. Teachers who are actively involved in professional learning activities can build significant professional capital.

Despite efforts made to develop teachers’ professional capital through pre-service and in-service training, previous studies have revealed a scarcity or lack of short-term training opportunities (Belilew, Citation2015; Tadesse, Citation2018, Citation2020; Wudu et al., Citation2009), teachers’ lack of knowledge and expertise (Adula & Kassahun, Citation2010; Birru, Citation2017; Daniel et al., Citation2013; Derebssa, Citation2006; Tadesse, Citation2018), lack of collaboration among teachers (Tadesse, Citation2015, Citation2018), as well as insufficient support, monitoring, evaluation, and feedback mechanisms for teachers’ professional growth (Ashebir, Citation2014; Birru, Citation2017; Goitom, Citation2015; Tadele, Citation2013) as major obstacles to teachers’ professional development in Ethiopia. A recent national survey conducted by the Ministry of Education (MoE) showed that the most serious challenges in the teaching profession in Ethiopia are recruiting low achievers and less committed candidates, poor quality of the teaching force, low teachers’ motivation, and high teachers’ turnover (MoE, Citation2018). This empirical evidence suggests that teacher development and the teaching profession in Ethiopia face a slew of challenges, implying a need for significant investment in developing teachers’ professional capital.

Moreover, teachers in a sample of Ethiopian schools expressed a desire to leave teaching anytime a better opportunity arose (Fekede & Tynjälä, Citation2015; MoE, Citation2015; Tadesse et al., Citation2021; Yalew et al., Citation2010). They have also shifted their focus from providing quality instruction to ways by which they can get out of the profession and earn a better income in their quest to meet their and their family’s basic needs (Fekede & Tynjälä, Citation2015; Tadesse et al., Citation2021). This evidence indicates the teachers’ dissatisfaction with their job and intention to leave the teaching profession, which jeopardizes investment in teacher professional capital. In connection to this, research has shown a link between teachers’ satisfaction with their job and work environment and their intention to stay in the profession, as well as their performance and professionalism (Jain & Verma, Citation2014; OECD, Citation2016; Pilarta, Citation2015; Toropova et al., Citation2020; Werang & Agung, Citation2017). As investment in professional capital in the teaching profession (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012) is an emerging issue in developing countries, including Ethiopia, little is known about the mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationships between teachers’ engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities and teachers’ professional capital development.

In other words, investing in teachers’ professional capital might lead to a transformation in a country’s current education system in general and the teaching profession in particular by encouraging teachers’ active participation in professional learning and growth and by intensifying their job satisfaction. Teachers satisfied with their job might actively participate in professional learning activities that will help them develop their professional capital. Recognizing the critical role of teachers’ professional capital in ensuring high-quality education (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012, Citation2013; Reichenberg & Andreassen, Citation2018; Uba & Chinonyerem, Citation2017), this study examined the effects of the teachers’ level of engagement in professional learning activities and job satisfaction on their professional capital development. Besides, the study aimed at examining the mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between teachers’ engagement in professional learning activities and their perceived professional capital development. Besides, the study aimed at examining the mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between teachers’ engagement in professional learning activities and their perceived professional capital development, the case of Banja Woreda primary schools, Ethiopia. Accordingly, the following hypotheses were raised.

There is a positive relationship between teachers’ level of engagement in collaborative professional learning activities and their professional capital development.

There is a positive relationship between teachers’ level of engagement in individual professional learning activities and their professional capital development.

Teacher job satisfaction has mediating effect on the relationship between teachers’ engagement in individual professional learning activities and their professional capital development.

Teacher job satisfaction has mediating effect on the relationship between teachers’ engagement in collaborative professional learning activities and their professional capital development.

2. Literature review

2.1. Conceptualizing teachers’ professional capital

Building professional capital in the teaching profession is a relatively new notion. Originally, professional capital in the teaching profession was coined by Hargreaves and Fullan (Citation2012) in their book entitled “Professional capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School”. According to Hargreaves and Fullan (Citation2012), professional capital is the systematic development and integration of three types of capital, including human, social and decisional capital, in the teaching profession. They claim that this new notion has the potential to change how people think about teaching, as well as the quality of education and how to achieve it. The concept of professional capital in teaching emphasizes how enhancing teachers’ professional capital can aid in the creation of a dynamic new profession that benefits every school in every country (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). Professional capital, by definition, implies bearing and constructing a truly excellent system that pushes the limits of what teachers can achieve for each student (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). As Hargreaves and Fullan (Citation2012) pointed out, viewing teaching as the formation and circulation of professional capital, as well as the investment and reinvestment of professional capital, might help us rethink how we view teaching and how to transform it. They also conceive that professional capital may help to clear up misconceptions about teaching and point the way to a more productive future for all educators.

The concept of professional capital in the teaching profession is a synthesis of three sub-concepts, including human capital, social capital, and decisional capital (Fullan, Citation2016; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012, Citation2013), that all three must be addressed clearly and in combination to develop teachers’ professional capital across and beyond the school (Fullan, Citation2016). Human capital is one dimension of professional capital in teaching (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). Although economists originally noted the concept of human capital in the 1960s, Hargreaves and Fullan (Citation2012) were the first to remark human capital as one dimension of teacher professional capital. Human capital in the teaching profession denotes teachers’ subject matter and pedagogical knowledge, their understanding of the students and their learning styles as well as their emotional and social capabilities to support students from diverse backgrounds (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). According to Fullan (Citation2016), human capital entails the human resource or personnel dimension of the quality of teachers in the school, i.e., their basic teaching competencies. In any organizational context, including the school, human capital development is often referred to as a strategy that helps employees to advance their personal and organizational skills, knowledge, and ability (Healthfield, Citation2011).

Social capital is another dimension of professional capital in teaching (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012).

Teacher social capital can be built in the quantity and quality of trustful interactions and social relationships individuals’ interpersonal relationships (Häuberer, Citation2011; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012; Herzog, Citation2016; Leana, Citation2011; Sell, Citation2015) within the schools. The social capital theory assumes that the “social capital resources are embedded within, available through, and derived from social networks of interconnected people, groups, organizations, or nations” (Miles, Citation2012, p. 254). Supporting this idea, Fullan (Citation2016) briefed that social capital is articulated in the interactions and relationships among the staff of any school that support a common cause. Hence, interpersonal trust and individual expertise work hand in hand toward better development of social capital.

Decisional capital is the third dimension of professional capital in the teaching profession (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). Although human capital and social capital are core domains of teacher professional capital, they are not sufficient to develop professional capital in the absence of decisional capital (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). As a result, decisional capital is appeared to be one major dimension of teachers’ professional capital that refers to the teachers’ ability to make discretionary judgments (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). Conceptually, decisional capital refers to “resources of knowledge, intelligence, and energy that are required to put human and social capital to effective use” (Fullan, Citation2016, p. 47). It fundamentally denotes the teachers’ capability to make the best choice, wise and informed decisions during instruction as well as in more complex and often unfamiliar situations (Fullan, Citation2016; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012; Reichenberg & Andreassen, Citation2018; Sell, Citation2015), and therefore, it should be assumed both at the individual level that implies teacher’s expertise and at group levels that exhibit the collective judgment of two or more teachers (Fullan, Citation2016). As Fullan noted, to develop teachers’ decisional capital the school leaders should have great decisional capital of their own. Hence, decisional capital could not be built through individual teachers’ sole efforts, but rather through a collective effort of teachers and school leaders who work together for school success (Fullan, Citation2016). This domain of professional capital allows teachers to make wise decisions in situations where there is no prescribed rule. To summarize, this study conceptualized professional capital as made up of human, social and decisional capital based on Harris and Jones (Citation2017) original theoretical model that was recently validated in Sintayehu’s (Citation2021) study. Thus, professional capital was proposed as a second-order latent construct that contained three first-order latent factors or indicators, i.e., human, social, and decisional capital.

2.2. Teachers’ engagement in professional learning and professional capital development

If teachers are expected to prepare pupils to be lifelong learners, they must continue to study and grow throughout their careers (OECD, Citation2014). As OECD (Citation2014) pinpointed, teachers must be able to employ not only the most up-to-date tools and technologies with their students, but also the most up-to-date research on learning, pedagogies, and practices. Doing so demands building teachers’ professional capital (human, social and decisional capital). Therefore, access to high-quality professional development is necessary (OECD, Citation2014) for teacher professional capital development. Moreover, literature has shown the importance of instituting a professional learning community within the school as a keystone to build professional capital (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012; Harris & Jones, Citation2017). Ensuring quality professional learning communities through collaboration within, between, and across schools at both the local and central levels has been a powerful strategy for building teachers’ professional capacity and enhancing their professional capital (Harris & Jones, Citation2017).

Harris and Jones (Citation2017) highlighted a strong and positive link between the quality of professional learning communities within the school and teachers’ professional capital development. As human capital is all about the quality of teachers’ initial training and continuing professional development as well as their professional skills, qualifications, and knowledge (Harris & Jones, Citation2017), teachers’ level of engagement in both individual and collaborative professional learning activities would have a great influence on their professional capital development. As social capital denotes the impact that teachers as learning professionals have on each other through collaboration and professional learning communities (Harris & Jones, Citation2017), their level of engagement in collaborative professional learning activities, such as team teaching, collaborative action research, and visiting other schools, would have a potential influence on professional capital development. As decisional capital refers to the development of teachers’ professional judgment and careers (Harris & Jones, Citation2017), their engagement in self-reflective practices and professional decision making and practice of utilizing constructive comments and feedback from other teachers and students would have the potential to build their professional capital.

As it is about an individual’s talent, it is impossible to increase human capital, which is one dimension of professional capital, just by focusing on it in isolation (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). Therefore, purposeful use of teamwork is the most powerful strategy that provides teachers with opportunities to learn from each other within and across schools as well as to build “cultures and networks of communication, learning, trust, and collaboration around the team” (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012, p. 89). This idea highlights the association between teachers’ engagement in collaborative professional learning and their professional capital development. The notion of teachers’ professional capital development, particularly human capital development, comprises the competency improvement opportunities for employees, such as employee training, career development, coaching, monitoring, and performance management and development (Healthfield, Citation2011). Similarly, teachers’ professional capital development in general and human capital development, in particular, necessitates the provision of professional learning, training, and development opportunities for teachers (Uba & Chinonyerem, Citation2017).

As mentoring has the potential to build teachers’ decisional capital (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012) and provides them with a way to build relationships with other teachers and to collaborate to improve their teaching practice (OECD, Citation2014), teachers’ engagement in such professional development activity will help them enhance professional capital. Therefore, teachers should participate in mentorship activities as mentors and mentees despite their teaching experience (OECD, Citation2014) to develop their professional capital, especially decisional capital. In connection to this, school leaders and cluster supervisors must “ensure availability of and participation in professional development for all teachers” (OECD, Citation2014, p. 21). According to OECD (Citation2014), promoting teachers’ engagement in collaborative professional development activities provides teachers not only with new professional skills and knowledge but also helps build a strong professional relationship between teachers. Such opportunity is very important to enhance teachers’ professional capital as a whole and boost social capital specifically. From this perspective, teachers’ engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities would have a great influence on their professional capital development.

To maintain a more comprehensive professional capital development system, particularly the human capital system, the schools need to recruit quality teachers, support teachers’ professional development, and establish incentive mechanisms to model high performer teachers (Myung, Martinez, & Nordstrum, Citation2013). Given the educational and economic rationales, “developing and supporting teacher human capital is arguably one of the most important functions of a school district” (Myung et al., Citation2013, p. 30). Based on this notion, fostering teachers’ engagement in professional learning activities by instituting a supportive professional learning climate is the keystone for investment in teacher professional capital, especially in building human capital.

As professional capital in general and social capital, in particular, is built in the quantity and quality of interactions and social relationships among the school community, it increases teachers knowledge by providing them with access to other teachers’ human capital and expanding their networks of influence and opportunity (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). Sell (Citation2015) associates social capital in the teaching profession with the teachers’ collective capacity to work together and share responsibility for the outcomes of their decisions and behaviors. Teachers’ collaborative network (social capital) to develop their knowledge and skills (human capital) in the long-term cultivates professionalization of teaching and teacher professionalism as a whole—building professional capital (Ikoma, Citation2016). Teachers can build their social capital in schools by exchanging valuable information or advice with other teachers about how to teach more effectively (Leana, Citation2011). A strong teachers’ social capital lets them “continually learn from their conversations with one another and become even better at what they do” (Leana, Citation2011, p. 33). According to Leana (Citation2011), a strong social capital could be built in a school context where the relationships among teachers are characterized by high trust and frequent interaction.

Teachers’ engagement in reflective professional practice and learning is essential to build decisional capital (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). Accordingly, decisional capital contains the quality of reflective practices, the use of research to inform practice, and shared and agreed frameworks that guide the decision-making process in the school (Sell, Citation2015). Individual and collective professional development that enables and validates teachers’ professional judgment and influence, according to Belilew (Citation2015) is effective in increasing teachers’ decisional capital. They also demonstrated that teachers, who engage in professional learning communities, collaborative inquiry, and networking outside of their classrooms, as well as schools and local education systems, may develop their social capital. Hargreaves and Fullan (Citation2012) contended that teachers can advance their decisional capital by considering their colleagues’ insights and experiences in making judgments over many occasions. In this regard, teachers should receive constructive comments and feedback that will help them improve (OECD, Citation2014) their professional capital, especially decisional capital. Teachers believe that such feedback influences their use of student evaluations as well as their classroom management practices (OECD, Citation2014).

As a learning organization, the schools should have well-led groups working and learning together to create specific improvements in instructional practice that promote student learning (Fullan, Citation2016). Nolan and Molla (Citation2017) noted that effective professional learning programs, such as mentorship, are critical to enhancing the professional capital of teachers. In a similar vein, Thoonen et al. (Citation2011) found that by participating in professional learning and development activities, teachers can improve their professional development as well as the development of their school, and thus make a significant contribution to improving teaching practices. Teachers’ engagement in professional learning activities such as keeping up to date, experimenting, and reflecting is very important (Thoonen et al., Citation2011) to boost teachers’ professional capital. Furthermore, teachers who participated in collaborative professional learning activities at least five times a year reported much higher confidence in their professional abilities (OECD, Citation2014, Citation2020), i.e., professional capital.

Based on the evidence mentioned above, the researchers hypothesized that the teachers’ level of engagement in collaborative professional learning activities would affect their professional capital development. Likewise, the researchers hypothesized that the teachers’ level of engagement in individual professional learning activities would affect their professional capital development.

2.3. Teachers’ job satisfaction and professional capital development

Teachers’ decision to stay in or quit the profession may be influenced by their level of job satisfaction.

Previous research has found a link between teachers’ job satisfaction and their decision to stay in the profession as well as their performance and professionalism (Jain & Verma, Citation2014; OECD, Citation2020; Pilarta, Citation2015; Toropova et al., Citation2020; Werang & Agung, Citation2017). A recent study by Sintayehu (Citation2021) showed a positive effect of teachers’ job satisfaction on their professional capital development. Another study also found a substantial link between teachers’ contentment with their profession and work environment and teachers’ professionalism (OECD, Citation2016). According to these findings, as teachers’ job satisfaction improved, so did their desire to stay in the teaching profession and their professionalism, which in turn enhanced overall professional capital, particularly human capital. Moreover, research has shown a positive relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and teachers’ confidence in their professional ability (OECD, Citation2014, Citation2020).

Given that teacher job satisfaction is a key to retaining quality teachers (e.g., OECD, Citation2016, Citation2020; Pilarta, Citation2015), fulfilling teachers’ professional, psychological and human needs is very important to elevate their job satisfaction and consequently, to build up professional capital in the teaching profession as a whole. Based on the above evidence, the researchers hypothesized that job satisfaction would directly affect teachers’ professional capital development.

2.4. Teacher job satisfaction and engagement in professional learning activities

As evidence has shown, on one hand, teachers’ job satisfaction is influenced by their engagement in professional learning and development activities (Liu, Citation2018; OECD, Citation2014, Citation2020; Toropova et al., Citation2020). A comprehensive study by OECD (Citation2014) specifically showed that the teachers who engage in collaborative teaching and learning approach five times or more per year exhibit higher levels of job satisfaction. Thus, the level of engagement of teachers in collaborative professional learning activities was found to have a positive and substantial link with their job satisfaction (OECD, Citation2014). This study also revealed a positive correlation between teachers’ perception about the importance of appraisal and feedback systems to shift their teaching practice and their job satisfaction, which suggests a link between teachers’ decisional capital development and teachers’ job satisfaction.

Research has also revealed a positive association between teachers’ job satisfaction and their participation in professional development activities, such as formal and informal induction, team teaching, observation or coaching programs, mentorship activities, and participation in courses, workshops, conferences, and decision-making process (OECD, Citation2014, Citation2020). Specifically, teachers who engaged in “teaching jointly in the same class, observing and providing feedback on other teachers’ classes, engaging in joint activities across different classes and age groups and taking part in collaborative professional learning” (OECD, Citation2014, p. 198). Based on this evidence, the researchers argued that there is a positive relationship between teachers’ level of engagement in collaborative professional learning activities and their job satisfaction. Similarly, the researchers proposed positive relationship between teachers’ level of engagement in individual professional learning activities and their job satisfaction.

On the other hand, evidence has shown that the teachers’ job satisfaction has influenced the efforts of building professional capital in the teaching profession through retaining more qualified teachers and promoting teacher professionalism (OECD, Citation2016; Toropova et al., Citation2020; Werang & Agung, Citation2017). Recently, Sintayehu (Citation2021) found a significantly positive and direct effect of teachers’ job satisfaction on their professional capital development in primary schools. However, scant evidence is found regarding the mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationships between teachers’ engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities and teachers’ professional capital development. Based on this evidence, we proposed that teacher job satisfaction would mediate the effects of teachers’ engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities on their professional capital development. Based on this evidence, the researchers argued that teacher job satisfaction would mediate the effects of teachers’ engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities on their professional capital development.

3. Method

3.1. Research design

For this study, correlational quantitative research design was employed. For this, advanced approach of structural equation modeling was employed to provide strong evidence on the influences of teachers’ level of engagement in professional learning and job satisfaction in building teachers’ professional capital.

3.2. Participants and procedure

A sample of 302 teachers (male = 188, female = 114) from primary schools of Banja Woreda of Ethiopia participated in this study. The participation of teachers in the current study was voluntary and they were informed that the collected data will be anonymous and serve only for academic purpose. Regarding the participants’ demographic variables: 188 (62.3%) were male teachers and 114 (37.7%) were female teachers. Regarding their educational status, 240 (79.5%) teachers were Diploma holders, while 62 (20.5%) of them were First Degree holders. Moreover, the participants’ teaching experience ranged from 1 to 31 years.

3.3. Measures

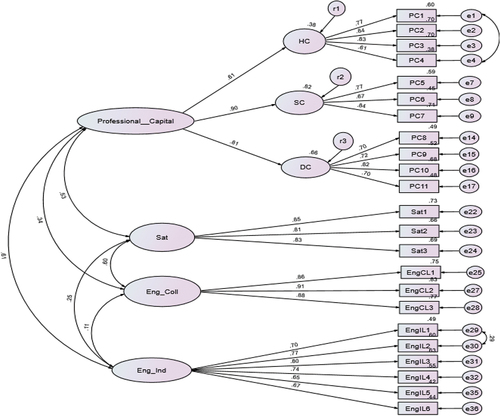

3.3.1. Teachers’ professional capital

Teacher professional capital is a second-order latent construct that contained three first-order latent factors (human, social and decisional capital; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). It was measured using the survey inventory originally developed by Hargreaves and Fullan (Citation2012) and recently validated by Sintayehu (Citation2021) using EFA and CFA approaches. We preferred this scale because the construct validity and reliability were established using rigorous statistical procedures. This measurement scale comprised three dimensions: (1) human capital (four items, α = 0.86, e.g., “Career opportunities in this school improved my professional growth and practices”); (2) social capital (three items, α = 0.80, e.g., “I have improved the way I teach as a result of collaborating with other teachers at my school”); and (3) decisional capital (four items, α = 0.82, e.g., “I regularly take time to reflect on what didn’t work in my teaching and figure out how to do things better next time”). The overall teacher professional capital development was measured using 11 items and the Cronbach’s alpha (α) was 0.87 (see, Table ). The scale was a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Table 2. Results from second-order CFA

3.3.2. Teacher engagement in professional learning

Teacher engagement in professional learning was measured using the scale developed by Sintayehu (Citation2021). As noted above, we preferred this measurement scale because its validity and reliability were established using rigorous statistical procedures, i.e., EFA and CFA. The scale contained two dimensions: (1) teacher engagement in individual professional learning activities (six items, α = 0.87, e.g., “I engage in reading professional literature”) and (2) teacher engagement in collaborative professional learning activities (three items, α = 0.92, e.g., “I engage in team teaching in the same class”). The scale was a 5-point Likert-type frequency scale that ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

3.3.3. Teacher job satisfaction

Teacher job satisfaction was measured using the scale originally developed by OECD (Citation2020) and later on validated by Sintayehu (Citation2021). We used this measurement scale because its validity and reliability were established using rigorous statistical procedures. The scale consisted of three items and the Cronbach’s alpha (α) was 0.87. For example, the items include: “I am satisfied with my job”. The scale was a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3.4. Data cleaning

The cases and variables were verified for unengaged replies, missed values, multivariate outliers, and influential scores. Three teachers’ data were neglected because of their unengaged responses with a standard deviation value of less than 0.25 (Collier, Citation2020), which showed similar responses given to each item within the scale. The missed data from five participants were imputed as the missed values accounted for less than 1% of the whole data collected from those participants (Hair et al., Citation2019). As Hair et al. (Citation2019) suggested, the data with less than 10% of missing values are acceptable and subject to any imputation method. Moreover, the Mahalanobis d-squared values showed that there were no observations farthest from the centroid.

3.5. Instrument validation

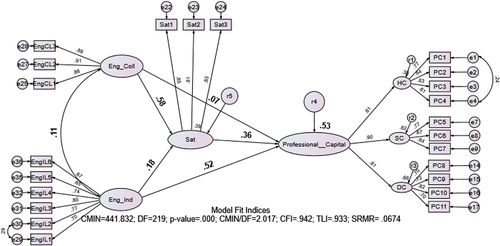

To establish the validity of constructs within each scale, we conducted first-order CFA in AMOS 23 followed by the second-order CFA. The measurement, as well as structural equation model goodness-of-fit, was evaluated using the following indices and their suggested acceptability criteria: relative chi-square test (χ2 /df ≤ 5), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI ≥ .90), Comparative Fit Index (CFI ≥ .90), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA ≤ .08, 90% CI), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR ≤ .08) as suggested in multiple sources (e.g., Collier, Citation2020; Hair et al., Citation2019; Ho, Citation2006; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). Both first-order CFA and second-order CFA analyses goodness of fit indices yielded a good model fit results, with χ2 = 385.709, df = 213, p < .001, χ2 /df = 1.811, RMSEA = 0.052, TLI = 0.946, CFI = 0.955 and SRMR = 0.048., and χ2 = 441.832, df = 219, p < .001, χ2/df = 2.017, RMSEA = 0.058, TLI = 0.933, CFI = 0.942 and SRMR = 0.067, respectively (see, Table ). As teacher professional capital is a second-order latent construct that consisted of the three first-order latent constructs (human, social and decisional capital), we used second-order CFA to test the follow-up SEM model.

Table 1. Model fit indices of first-order and second-order confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

As Table presents, all standardized factor loadings (βs) were above 0.6. For example, the standardized factor loading for the indicators of professional capital, which was proposed as a second-order construct, ranged from 0.61 to 0.90, p < .001. Likewise, the standardized factor loading for the indicators of teacher engagement in collaborative professional learning activities ranged from 0.86 to 0.91, p < .001.

Figure depicts the second-order CFA model with standard estimates.

3.5.1. Construct Validity and Reliability Assessment

As noted above, we performed both first-order and second-order CFA to test composite reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of constructs of each scale. In this regard, CFA is a very essential statistical approach to test construct reliability and validity that provides compelling evidence of the composite reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of theoretical constructs used in educational research (Brown, Citation2015).

3.5.1.1. Composite reliability

In addition to internal consistency reliability measured by Cronbach’s alpha analysis, composite reliability is another popular technique to assess construct reliability, which is also known as Raykov’s Rho (r) or factor rho coefficient (Collier, Citation2020; Kline, Citation2016). Like that of Cronbach’s alpha level for internal consistency reliability, the composite reliability has the same range and cutoff criteria for the acceptable level of reliability, i.e., >.70 (Collier, Citation2020). Given this criterion, as indicated in Table , the composite reliability values ranged from 0.81 for the social capital construct to 0.92 for the construct of engagement in collaborative professional learning activities, which showed higher composite reliability of the constructs.

Table 3. Inter-correlations, composite reliability, and average variance extracted generated from the second-order CFA

3.5.1.2. Convergent validity

Convergent validity determines the construct validity by specifying the degree to which all indicators of a given construct are measuring the same construct they are intended to measure (Collier, Citation2020). The criteria for convergent validity is that the average variance extracted (AVE) must be greater than .50 (Collier, Citation2020; Hair et al., Citation2019). As shown in Table , AVE values for all constructs ranged from 0.52 for the indicators of teacher engagement in individual professional learning activities to 0.79 for the indicators of teacher engagement in collaborative professional learning activities, which suggested adequate convergent validity across constructs.

3.5.1.3. Discriminant validity

This type of validity tests whether or not a construct is distinct and different from other studied constructs, and it can be assessed using the shared variance method (Collier, Citation2020) to determine the absence of multicollinearity issues. In the shared variance method, as Collier (Citation2020) points out, the discriminant validity of each construct can be determined by computing the shared variances between constructs and comparing them to the AVE values for each construct. Similarly, the discriminant validity can be established if inter-correlations among a set of constructs are not too high (commonly, < .85) (Brown, Citation2015; Collier, Citation2020; Kline, Citation2016). In this study, all coefficients for inter-correlations between constructs were below 0.85, which ranged from 0.11 for the relationship between Engagement in Individual Professional Learning Activities and Engagement in Collaborative Professional Learning Activities to 0.61 for the relationship between Engagement in Individual Professional Learning Activities and Professional Capital (see, Figure ). This evidence showed that all constructs in the current study discriminate from one another. Similarly, the shared variance between Engagement in Individual Professional Learning Activities and Engagement in Collaborative Professional Learning Activities was (0.11)2 = 0.012, which was far lower than the AVE for Engagement in Individual Professional Learning Activities (0.52) or AVE for Engagement in Collaborative Professional Learning Activities (0.79). This evidence showed that these constructs discriminate from one another. Moreover, the shared variance between Engagement in Individual Professional Learning Activities and Professional Capital (0.61)2 = 0.372, which is far lower than the AVE for Engagement in Individual Professional Learning Activities (0.52) or AVE for Professional Capital (0.62). This evidence showed that these constructs discriminate from one another. To sum, all constructs considered in the present study showed adequate discriminant validity.

4. Results

4.1. SEM analysis

In this study, we performed a second-order SEM analysis to test the hypothesized relationships among the study variables. As a result, SEM model test goodness of fit yielded a good model fit results, with χ2 = 441.832, df = 219, p < .001, χ2 /df = 2.017, RMSEA = 0.058, TLI = 0.933, CFI = 0.942, and SRMR = 0.067. Figure depicts the statistically significant path coefficients (p < .001), except the path coefficient from teacher engagement in collaborative professional learning to professional capital (p = .311). This SEM model explained 53.3% variation in the teachers’ professional capital development in primary schools.

Figure 2. Second-order structural equation model for teachers’ engagement in professional learning, job satisfaction and professional capital development with standardized estimates.

Teacher engagement in individual professional learning activities showed a significantly stronger and positive effect on teachers’ professional capital development (β = .52, p < .001) compare to the effect of teacher job satisfaction (β = .36, p < .001). These results indicated that the teachers who perceived a higher level of engagement in individual professional learning activities and job satisfaction respectively exhibited better professional capital development. However, teacher engagement in collaborative professional learning activities showed statistically nonsignificant (β = .07, p = .311) direct effect on teachers’ professional capital development.

The results also showed that teacher engagement in individual professional learning activities (β = .18, p = .001) and teacher engagement in individual professional learning activities (β = .58, p < .001) were significantly related to teacher job satisfaction. Table presents the SEM analysis results.

Table 4. SEM results predicting teachers’ professional capital development

Figure presents pictorial description of the structural relationships between teachers’ engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities, job satisfaction, and professional capital development with standardized estimates.

4.2. Bootstrap analysis

In the current study, we performed a bootstrap analysis to test the significance level of the mediating effect of teacher job satisfaction on the relationship between teacher engagement in professional learning activities (individual and collaborative) and teachers’ professional capital development, which indicated statistically significant indirect effects on teacher professional development (see, Table ).

Table 5. Standardized indirect effects of teacher engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning on professional capital

Teacher job satisfaction fully mediated the relationship between teacher engagement in collaborative professional learning activities and teacher professional capital development (β = .21, p = .002). This result showed that teachers’ level of engagement in collaborative professional learning exhibited a completely indirect influence on teachers’ professional capital development through teacher job satisfaction. However, teacher job satisfaction partially mediated the relationship between teacher engagement in individual professional learning activities and teacher professional capital development (β = .07, p = .006), which showed that the teachers’ level of engagement in individual professional learning exhibited statistically significant direct effect and an indirect effect via job satisfaction on the teachers’ professional capital development.

5. Discussion

The main purpose of the current study was to examine the effects of teachers’ level of engagement in collaborative and individual professional learning activities and job satisfaction on professional capital development. Besides, the study examined the mediating effect of teacher job satisfaction on the relationships between teachers’ level of engagement both in collaborative and individual professional learning activities and their professional capital development.

The present study affirmed that teacher level of engagement in individual professional learning activities is positively related to teachers’ perceived professional capital development. In this study, engagement in individual professional learning activities was measured by using the indicators of self-learning professional activities, such as teachers’ level of participation in reading professional literature, studying textbooks and lesson material thoroughly and regularly, making their own teaching materials, using students’ reactions to improve their classroom teaching, talking to their students, and providing constructive feedback for students’ future development (Ministry of Education (MoE), Citation2004, MoE, Citation2009). The study has shown significant both direct and indirect (via job satisfaction) effects of teachers’ level of engagement in individual professional learning activities on developing their professional capital. Besides, the findings showed that the teachers’ level of engagement in individual professional learning activities indirectly affects professional capital development through job satisfaction. These findings corroborated the previous study’s findings that showed significant and positive direct effects and indirect effects (via self-efficacy belief) of engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities on their perceived professional capital development (Sintayehu, Citation2021). This study findings also substantiate the previous findings that indicated a positive link between professional learning and development community and professional capital development (Campbell et al., Citation2016; Harris & Jones, Citation2017; Watts, Citation2018), and a positive and strong relationship between teachers’ participation in diverse professional learning activities, especially collaborative professional learning activities, and teachers’ professional development (Campbell et al., Citation2016; Ikoma, Citation2016; OECD, Citation2014, Citation2020; Thoonen et al., Citation2011). In this study, engagement in collaborative professional learning was measured using group-based professional learning activities, such as teachers’ level of participation in team teaching, conducting collaborative action research, and visiting other schools to observe better professional practices and adapt to their school context (MoE, Citation2009).

This study also showed that teachers’ level of engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities is positively associated with job satisfaction. Interestingly, our study highlighted that job satisfaction partially mediates the effect of engagement in individual professional learning activities and fully mediates the effect of engagement in individual professional learning activities on teachers’ professional capital development. These findings strengthen the previous findings that indicated positive and strong relationships between teachers’ engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities and job satisfaction (Liu, Citation2018; OECD, Citation2014, Citation2020; Sintayehu, Citation2021; Toropova et al., Citation2020). Our findings extend prior knowledge by demonstrating the positive and significant mediating effects of job satisfaction on the relationships between teachers’ engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities and their professional capital development.

Furthermore, the current study confirmed that teacher job satisfaction is positively and directly related to professional capital development. This finding solidified the previous evidence that showed a strong link between job satisfaction and their retention in the profession, professionalism, and professional capital development (Jain & Verma, Citation2014; OECD, Citation2020; Pilarta, Citation2015; Sintayehu, Citation2021; Toropova et al., Citation2020; Werang & Agung, Citation2017). Specifically, this study finding is consistent with Sintayehu’s (Citation2021) finding that showed a positive and a strong association between teachers’ job satisfaction and their professional capital development. The finding also stretched the previous evidence that highlighted a positive relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and their confidence in their professional knowledge and skills (OECD, Citation2014, Citation2020).

6. Conclusion

By applying an advanced approach of structural equation modeling, this study provides strong evidence on the influences of teachers’ level of engagement in professional learning and job satisfaction in building teachers’ professional capital. This study findings describe that the teachers’ better engagement in various individual professional learning activities, including reading professional literature, studying textbooks and lesson material thoroughly and regularly, making their teaching materials, and using student feedback to improve their classroom teaching, exhibits both direct and indirect positive influences on their perceived professional capital development. The findings also indicate that teachers’ level of engagement in collaborative professional learning activities, including team teaching, collaborative action research, and visiting other schools, shows a completely indirect influence on their perceived professional capital development through job satisfaction. These findings extend previous understanding about the relationship between teacher participation in professional learning and professional capital development by enlightening the mediating effect of job satisfaction.

Interestingly, this study sheds light on the mediating role of teacher job satisfaction on the influences of teacher engagement in individual professional learning activities and teacher engagement in collaborative professional learning in building teachers’ professional capital. As job satisfaction shows a significant positive direct effect on teachers’ professional capital development and mediates the effects of teachers’ engagement in professional learning activities on their professional capital development, it is very important to lift teachers’ job satisfaction by addressing their regularly proclaimed human and professional needs. As far as teacher professional capital is an indispensable strategy to transform the whole education system, every nation including Ethiopia needs to foster teachers’ engagement in collaborative and individualized professional learning endeavors by blending teacher professional development activities with life-long professional growth and hiking up job satisfaction.

7. Limitations and implications

7.1. Limitations

Despite the current study’s promising contributions to the overall conceptualization and understanding of professional capital development in teacher education and development programs, it is critical to acknowledge its shortcomings. First, as our study is entirely correlational, it limits causal inferences. Therefore, it is important to conduct longitudinal research using experimental research designs to solidify cause and effect relationships between teachers’ engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities, job satisfaction, and professional capital development. Second, the scope of our study is delimited to one district governmental primary schools that might restrict the generalizability of the findings to other districts and school contexts. Therefore, a more comprehensive study should be conducted by involving teachers from diverse contexts and private primary schools.

7.2. Implications

Investing in teacher professional capital becomes the key to transforming the teaching profession in particular and the overall education system in general and therefore education policymakers, education officials, school principals, and teachers must give serious attention to building teachers’ professional capital (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2013). This study indicated a potential influence of job satisfaction on the teachers’ professional capital development. Therefore, policymakers can intensify teachers’ job satisfaction by addressing their social, psychological, and economic needs (Taylor et al., Citation2015) and increasing their professional identity (Smith, Citation2017). To do so, policymakers can heighten the teachers’ professional status by inducing the teaching profession to become a profession of choice that attracts highly qualified graduates and by making it a highly paid profession than other professions, such as medicine and law. Besides, policymakers can intensify teachers’ job satisfaction and boost their professional capital by introducing need-driven self-directed professional learning program that fosters teachers’ career-long collaborative and reflective professional learning (Smith, Citation2017).

In the same vein, education officials and school principals can escalate job satisfaction and develop teachers’ professional capital by creating conducive school environment for teacher work and professional learning (OECD, Citation2020; Toropova et al., Citation2020). For example, the school principals can build up teachers’ professional capital by encouraging and supporting teacher engagement in diverse professional learning activities, including team teaching, collaborative action research, reading professional literature, studying textbooks and lesson material thoroughly and regularly, making their teaching materials, and using student feedback to improve their classroom teaching. Establishing supportive teacher professional learning climate within school is more imperative step to foster teacher engagement in individual and collaborative professional learning activities, and then, to elevate teachers’ professional capital in every school. Teachers who have reported, “higher participation rates in professional development activities” also report “higher levels of both monetary and non-monetary support for this development” (OECD, Citation2014, p. 3).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tadesse Melesse

Tadesse Melesse received his MA Degree & PhD in Curriculum & Instruction from Addis Ababa University and Bahir Dar University, respectively. He had been a primary school, secondary school and college teacher for more than a decade. He also worked as a research and community service director and a quality assurance coordinator at Woldia University; a community service coordinator and dean of College of Education and Behavioural Sciences, Bahir Dar University. He is now an Associate Professor in Curriculum and Instruction.

Sintayehu Belay

Sintayehu Belay received PhD in Education (Curriculum & Instruction) from Bahir Dar University. He published several articles related to teacher education and learning. He has been involved in teaching different teacher education courses. His major areas of research include teacher professionalism, professional capital development and life-long learning. He is now an Assistant Professor at Dire Dawa University.

References

- Adula, B., & Kassahun, M. (2010). Qualitative exploration on the application of student- centered learning in mathematics and natural sciences: The case of selected general secondary schools in Jimma, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Education & Sciences, 6(1), 41–19.

- Ashebir, M. (2014). Practices and challenges of school based continuous professional development in secondary schools of Kemashi Zone [ Master’s Thesis]. Institute of Education and Professional Development Studies, Jimma University.

- Belilew, M. (2015). Practices and challenges of implementing cooperative learning: Ethiopian high school EFL teachers’ perspectives. International Journal of Current Research, 7(12), 24584–24593.

- Birru, D. (2017). Practices and challenges of teachers’ continuous professional development program in secondary schools of East Shoa Zone, Oromia Regional State [ master’s thesis]. Haramaya University.

- Brown, T. A., (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press

- Campbell, C., Lieberman, A., & Anna Yashkina, A. (2016). Developing professional capital in policy and practice. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 1(3), 219–236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-03-2016-0004

- Collier, J. E. (2020). Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS: Basic to advanced. In techniques. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Daniel, D., Desalegn, C., & Girma, L. (2013). School-based continuous teacher professional development in Addis Ababa: An investigation of practices, opportunities and challenges. Journal of International Cooperation in Education, 15(3), 77–94.

- Derebssa, D. (2006). Tension between traditional and modern teaching-learning approaches in Ethiopian primary schools. Journal of International Cooperation in Education, 9(1), 123–140.

- Fekede, T., & Tynjälä, P. (2015). Professional learning of teachers in Ethiopia: Challenges and implications for reform. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(5), 1–26.

- Fullan, M. (2016). Amplify change with professional capital. JSD, 37(1), 44–56.

- Fullan, M., & Hargreaves, A. (2016). Bringing the profession back in: Call to action. Learning Forward.

- Fullan, M., Rincon-Gallardo, S., & Hargreaves, A. (2015). Professional capital as accountability. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23(15), 1–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v23.1998

- Goitom, G. (2015). Policy and practice of teachers’ continuous professional development program: The case of Arada Sub-city Government primary schools [ Master’s Thesis]. School of Graduate Studies, Addis Ababa University.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning, EMEA.

- Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. Teachers College Press.

- Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2013). The power of professional capital. Journal of Staff Development, 34(3), 36–39.

- Harris, A., & Jones, M. S. (2017). Professional learning communities: A strategy for school and system improvement? Wales Journal of Education, 19(1), 16–38. https://doi.org/10.16922/wje.19.1.2

- Häuberer, J. (2011). Social capital theory: Towards a methodological foundation. Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Springer Fachmedien.

- Healthfield, B. (2011). Human capital: A theoretical & empirical Analysis with special reference to education analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Herzog, T. (2016).Bowling together: On selected aspects of professional capital in 21st century education. Interdyscyplinarne Konteksty Pedagogiki Specjalnej, 15, 113–127.

- Ho, R. (2006). Handbook of univariate and multivariate data analysis and interpretation with SPSS. United States of America: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Ikoma, S. (2016). Individual excellence versus collaborative culture: A cross-national analysis of professional capital in the U.S., Finland, Japan, and Singapore [ Ph.D. dissertation]. College of Education, The Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved November 2/2019 from https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/files/final_submissions/11689

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2012). Handbook of good human resource practices in the teaching profession. ILO Publications. International Labour Office.

- Jain, S., & Verma, S. (2014). Teacher’s job satisfaction and job performance. Global Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 2(2), 2–15.

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Leana, C. R. (2011). The missing link in school reform. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 30–35. Retrieved March 13/2020 from: https://ssir.org/images/articles/Missing_Link_Cover.pdf

- Liu, X. (2018). Effect of professional development, self-efficacy on teachers’ job satisfaction in Swedish lower secondary school [ Master thesis]. Department of Education and Special Education, Ghent University. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31377.45925

- Miles, J. A. (2012). Management and organization theory. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (2004) . Continuous professional development for school teachers: A guide line. The federal democratic republic of Ethiopia. Ministry of Education, Addis Ababa.

- MoE, (2009). Continuous professional development for primary and secondary school teachers, leaders and supervisors in Ethiopia: The framework. Ministry of Education, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

- MoE. (2015). Education sector development programme V (ESDP V): Programme action plan. The federal democratic republic of Ethiopia. Ministry of Education, Addis Ababa.

- MoE. (2018). Ethiopian education development roadmap (2018-30). Education Strategy Center (ESC), Ministry of Education, Addis Ababa.

- Myung, J., Martinez, K., & Nordstrum, L. (2013). A human capital framework for a stronger teacher workforce.Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Stanford, California. Retrieved November 10/2019 from https://www.carnegiefoundation.org/wp- content/uploads/2013/08/Human_Capital_whitepaper2.pdf

- Nolan, A., & Molla, T. (2017). Teacher confidence and professional capital. Teaching and Teacher Education, 62, 10–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.11.004

- OECD. (2014). TALIS 2013 Results: An international perspective on teaching and learning. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264196261-en

- OECD. (2016). Supporting teacher professionalism: Insights from TALIS. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264248601-en

- OECD. (2020). TALIS 2018 results (volume ii): Teachers and school leaders as valued professionals. https://doi.org/10.1787/19cf08df-en

- Pilarta, M. A. (2015). Job Satisfaction and teachers performance in Abra state institute of sciences and technology. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 15(4), 81–85.

- Reichenberg, M., & Andreassen, R. (2018). Comparing Swedish and Norwegian teachers’ professional development: How human capital and social capital factor into teachers’ reading habits. Reading Psychology, 39(5), 442–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2018.1464530

- Sell, K. (2015). Receptive accountability and professional capital: An examination of teachers’ perceptions in an international school. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 2(1). Retrieved from: http://www.ijicc.net

- Sintayehu, B. (2021). Analysis contributions of school climate and teachers’ professional identity to professional capital development in Awi zone primary schools [ Ph.D. dissertation]. Department of Teacher Education and Curriculum Studies, Bahir Dar University.

- Smith, K. (2017). Teachers as self-directed learners: Active positioning through professional learning. Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

- Tadele, Z. (2013). Teacher induction and the continuing professional development of teachers in Ethiopia: Case studies of three first-year primary school teachers[ Doctoral Dissertation]. University of South Africa

- Tadesse, M. (2015). Differentiated instruction: Perceptions, practices and challenges of primary school teachers. Science, Technology and Arts Research Journal, 4(3), 253–264. http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/star.v4i3.37

- Tadesse, M. (2018). Perceptions of primary school teachers on differentiated instruction. Bahir Dar Journal of Education, 19(1), 152–173.

- Tadesse, M. (2020). Differentiated instruction: Analysis of primary school teachers’ experiences in Amhara region, Ethiopia. Bahir Dar Journal of Education, 20(1), 91–113.

- Tadesse, M., Belete, K., Tilaye, K., Abreham, Z., & Desalegn, T. (2021). A study on re-thinking teachers, school leaders and educational professionals training in Ethiopia” (draft). MoE & EDT. Addis Ababa.

- Taylor, J., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., & Peterson, E. R. (2015). Motivated learning: The relationship between student needs and attitudes. In C. M. Rubie-Davies, J. M. Stephens, & P. Watson (Eds), The Routledge international handbook of social psychology of the classroom (pp. 42–50). New York, NY: Routledge: Routledge

- Thoonen, E., Sleegers, P., Oort, F., Peetsma, T., & Geijsel, F. (2011). How to improve teaching practices: The role of teacher motivation, organizational factors, and leadership practices. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47(3), 496–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X11400185

- Toropova, A., Myrberg, E., & Johansson, S. (2020). Teacher job satisfaction: The importance of school working conditions and teacher characteristics. Educational Review, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2019.1705247

- Uba, N. J., & Chinonyerem, O. J. (2017). Human capital development a strategy for sustainable development in the Nigerian education system. African Research Review, 11(2), 178–189. http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v11i2.13

- United Nations. (2016). Guide on measuring human capital. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/consultationDocs/HumanCapitalGuide.web.pdf

- Watts, D. S. (2018). The relationship between professional development and professional capital: A case study of international schools in Asia. University of Kentucky. Theses and Dissertations–Education Science. 44. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/edsc_etds/44

- Werang, B. R., & Agung, A. A. (2017). Teachers’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and performance in Indonesia: A study from Merauke District, Papua. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 6(8), 700–711.

- Wudu, M., Tefera, T., & Woldu, A. (2009). The practice of learner-centered method in upper primary schools of Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Journal of Education and Sciences, 4(2), 27–43.

- Yalew, E., Dawit, M., & Alemayehu, B. (2010). Investigation of causes of low academic performance of students in grade 8 regional examination in Amhara Region. Amhara National Regional State Education Bureau.