Abstract

The present study aimed to culturally adapt the Stirling Children’s Well-being Scale (SCWBS) for use in Indonesia with college student and to assess their psychometric properties in this population. This study investigated the dimensions, particularly the nature and number, of the Indonesian version of the SCWBS. Three hundred seventy-five Indonesian college students were recruited through WhatsApp. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were performed on two subsamples, which were randomly divided using IBM SPSS, and the reliability of the SCWBS was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. An exploratory factor analysis extracted two dimensions, which explained 58.24% of the total variance. A confirmatory factor analysis was performed on the two-factor measurement model of the scale, along with one second-order factor. These were found to have good model fit. The final 10-item SCWBS had high reliability and acceptable construct validity. Therefore, the scale was found to have adequate psychometric properties and to be applicable in research and practice. For further refinement, the Indonesian version of the SCWBS should be tested in a wider age range and in various subgroups, for example, to analyze socioeconomic status. Furthermore, it is necessary to assess other construct validity, such as criterion validity.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

A culturally appropriate and validated Indonesian version of the Stirling Children’s Well-being Scale (SCWBS) is needed for accurate use of the scale in research and practice. Three hundred seventy-five Indonesian college students were recruited through WhatsApp. The scale’s psychometric properties were assessed using exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and analysis of internal consistency. The confirmatory factor analysis confirmed two factors, namely, “positive emotional state” and “positive outlook”. Therefore, the scale was found to have adequate psychometric properties and to be applicable in research and practice. This the SCWBS Indonesian Version can serve as a tool for identifying issues that contribute towards late adolescent wellbeing for Indonesian context.

1. Introduction

The concept of subjective well-being is often viewed as synonymous with happiness (Snyder & Lopez, Citation2007) and is heavily influenced by the hedonistic philosophy put forth by several theorists in the past. This principle is based on the view that whatever causes pleasure is good (Ryan & Deci, Citation2001). Diener et al. (Citation2002) defined subjective well-being as a combination of positive and negative effects. The concept also involves an individual’s subjective evaluation of his or her condition at a particular moment. According to Diener et al. (Citation1999) the components of subjective well-being are positivity, reduced negative effects, and high life satisfaction.

Some philosophers and psychologists have argued that subjective well-being is only focused on satisfying desires, and as a result, what it means to be human seems to be diminished. Therefore, the concept of psychological well-being, which is based on eudaimonic philosophy (Ryan & Deci, Citation2001), has emerged. The concept of psychological well-being emphasizes that individual happiness or welfare is not solely based on the enjoyment principle but combined with various other factors (Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995). According to Ryff and Keyes (Citation1995), there are six dimensions of psychological well-being: autonomy, life purpose, environmental control, personal growth, self-acceptance, and positive relationships with others. The authors further suggest that psychological well-being involves self-actualization to achieve happiness. Although the hedonistic approach initially dominated in well-being studies, the contribution of eudaimonic philosophy has improved the understanding of the concept as a whole (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008).

Hedonistic concepts are often associated with motivation to fulfill one’s desires. Although the eudaimonic approach does not mean eliminating life satisfaction, its primary focus is on the fulfillment of one’s potential as a human being (Bosković & Jengić, Citation2008). Ideas and research balancing these two concepts began to emerge in the last period (Henderson & Knight, Citation2012). For instance, Tennant et al. (Citation2007) suggested that the two types of well-being combined to form a mental equivalent, and some studies have attempted to build several formulas. These formulas were based on the idea of a balance between the two approaches (Tomer, Citation2011), and both were compared with self-control (Joshanloo, Citation2016), resilience, personality, and liquid intelligence (Di Fabio & Palazzeschi, Citation2015).

Another study conducted by Liddle and Carter (Citation2015) combined these two welfare approaches. The measuring instrument components were developed to consist of positive emotional states as a hedonistic representation and a positive outlook to exemplify the eudaimonic aspect. Examples of positive emotional states were feelings of cheerfulness, relaxation, and interest in new things. A positive outlook was characterized by belief in one’s abilities and good things in the future, and a good relationship with the social environment. Therefore, the measuring instrument appeared to be contained in one construct.

The Stirling Children’s Well-being Scale (SCWBS) is a measuring instrument developed by Liddle and Carter (Citation2015) that has been used in research in various countries. A study by Godfrey et al. (Citation2015) with 84 British respondents aged 8 to 18 years, with social and mental health problems, used the scale as one aspect of the intervention goal. The SCWBS measurement tool was used in the pre-and post-tests of positive outlook on six items. Another study, by Widiasmara et al. (Citation2018), examined the impact of school empathy interventions on the emotional and psychological well-being of elementary school students in Indonesia. The age range of the respondents was 9 to 14 years, and the children were divided into control and experimental groups. Interestingly, the results of this training had a beneficial impact on the positive aspects of outlook rather than emotional state.

Skrzypiec et al. (Citation2018) also used this assessment tool in their research on 2,756 Chinese middle school students aged between 10 and 14 years (M = 12; SD = 1.53) to determine predictors of student welfare. They measured resilience, global self-concept, school satisfaction, and the students’ relationships with one another; the results showed that all the values were significant predictors of student well-being in China. The study by Skrzypiec et al. (Citation2018) used SCWBS, and the results showed that the chi-square model fit x2 (42) = 211.83, p = .000, CFI = .979, TLI = .972, RMSEA = .043, 90% CI = .037-.048, RMSE ≤ .05 (.978), SRMR = .024, with a value of H = .910. In addition, Manyeruke et al. (Citation2020) also used this tool in Zimbabwe in a study with children with ages ranging from 8 to 15 years, of which 57 were left behind and belonged to transnational families, while 41 were from conventional families. Manyeruke et al.’s (Citation2020) study showed a Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of 0.75, with a value of 0.79 and 0.70 for the positive emotions subscale and outlook, respectively. Based on this description, SCWBS can be used in the Indonesian context.

Another study by Bernay et al. (Citation2016) in New Zealand with elementary school students aged 9 to 12 years used the SCWBS at baseline and at 3-months follow-up to evaluate the level of children’s welfare after undergoing a series of training programs. In a study by Amundsen et al. (Citation2020) with respondents aged between 9 and 10 years, 108 students in England aimed to observe the effectiveness of mindfulness training, which had an impact on welfare. The research measured positive outlook, life satisfaction, and emotional regulation. The SCWBS was used to evaluate positive outlook, which generally measures the level of children’s well-being. Hinshaw et al. (Citation2015) also used this tool in their assessment of welfare of children in a single group. They investigated the impact of a community group singing project on the psychological well-being of children aged 7 to 11 years. The psychological well-being of the choir members did not improve after participation in the singing project.

Furthermore, this scale was used by Devcich et al. (Citation2017) to measure level of welfare in awareness training that had an impact on children’s well-being, and by Testoni et al. (Citation2020) in experimental research on death education training as a preventative measure. Another study, by Haque and Imran (Citation2016), on this tool was conducted in Bangladesh, and included 238 students aged between 10 and 16 years, where the selection of these persons from the three schools was different. The adaptation process consisted of several stages with cultural considerations and psychometric processes, while the results of the retest reliability coefficient and Cronbach’s alpha value were 0.791 and 0.746, respectively. Furthermore, the construct validity test used the Beck Self-Concept Inventory for Youth and Beck Anxiety Inventory for Youth tools. These are two subtests for the adaptation of the Bangla Beck Youth Inventories of Emotional and Social Impairment Scale, and values of 0.668 and −0.350 were produced, respectively. The item-total correlation yielded scores of 0.258 to 0.451, while the average values of this measuring instrument were M = 57.31, SD = 7.587. Therefore, the results of this adaptation are considered reliable and valid for the criteria of measuring instruments.

In the Indonesian context, some studies have developed the measuring instruments related to children’s well-being. Abidin et al. (Citation2020) developed a measurement of well-being in children aged 12 to 15 years with 38 items. The instrument tried to combine the eudaimonic and hedonic perspectives with 10 dimensions of the measuring tool. The number of dimensions in the measuring instrument was relatively large, indicating the complexity in the abstraction of theoretical concepts. In another study, Aryono (Citation2018) developed measuring instrument in Indonesia related to children’s well-being with 48 items. It also used a different theoretical approach to SCWBS and was considered to have many items. Maulana et al. (Citation2019) developed the Indonesian Wellbeing Scale based on a theoretical construct that was built from an Indonesian perspective. In this study, four dimensions of the measuring tool were developed, namely basic needs, social relations, acceptance, and spirituality. This indicated that there was a eudaimonic approach used in this measuring tool. However, from the content analysis, it was concluded that this scale was more appropriate for adults rather than adolescences. Based on the comparison of instruments developed in Indonesia, it appears that there is an effort to adapt instruments. However, there is a difference related with the age of the respondents for the measuring instrument used. In addition, compared to the three measuring tools, the SCWBS has advantages because it combines hedonistic and eudaimonic perspectives with a more concise number of factors and items.

Based on research in various countries, the SCWBS was determined to have good reliability. Although only one study, conducted by Haque and Imran (Citation2016), focused on SCWBS adaptation; however, it did not test the theoretical construct. In addition, the results of a previous study by Widiasmara et al. (Citation2018) in Indonesia also used the SCWBS. There were several weaknesses in this research: (1) The back-translation method was not used in the process of translating measuring instruments from English to Indonesian; (2) The number of participants involved in the study was limited (<100 people) and in middle childhood children; (3) The analytical method still uses Cronbach’s alpha item reliability (Alpha Cronbach = 0.760) which indicates a moderate level of reliability and does not use the factor analysis method. It is assumed that moderate level of reliability due to limited numbers of participants and homogenous characteristics. Based on this background, this study seeks to offer a more comprehensive method to overcome these three limitations. Therefore, this investigation intends to adapt the SCWBS scale measurement tool (Liddle & Carter, Citation2015) in the analysis of late adolescence in Indonesia. This is the novelty of the research, and it attempts to balance the hedonistic and eudaimonic perspectives.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 375 college students were recruited through the WhatsApp social media application (WhatApp Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA). The online Google Form platform (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA) was employed to obtain written consent from the participants, and to carry out the data collection process. The respondents received a small cash amount as compensation. The participants consisted of 302 females (80.5%) and 73 males (19.5%). Participant age ranged from 18 to 22 (M = 19.64, SD = 1.077 for women and M = 19.92, SD = 1.010 for men). They were from public universities (55.2%) and private universities (44.8%). In term of pocket money, 52.5% get an pocket money of less than 34.62 USD per month, 28,3% get an pocket money between 34.62 and 69.25 USD per month, and 19.2% more than 69.25 USD. The participants used a pseudonym to fill out the forms. The purpose and benefits of the research, voluntary nature of participation, availability of filling assistance if needed, follow-up if the respondent wanted to know the results of the research, ability to withdraw at any time, information on the form of research compensation, were explained and the participant was asked to fill out the consent form. This research was approved by the Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher Education (Number: 002/DirDPPM/70/DPPM/Pen. Dasar—KEMENRISTEKDIKTI/VI/2020).

2.2. Measurement

The SCWBS was adapted before being administered to the participants as part of a larger survey, and the quality was ensured by following the steps recommended by Beaton et al. (Citation2000). The following steps were followed by Beaton et al.: (1) initial translation, (2) synthesis of the translation, (3) back translation, (4) expert committee, and (5) test of the prefinal version. The process of cross-cultural adaptation tries to produce equivalency between the source and target based on content. The assumption that is sometimes made is that this process will ensure retention of psychometric properties such as validity and reliability at an item and/or scale level (Beaton et al., Citation2000).

First, the SCWBS was independently translated into Indonesian by two people who understood both the Indonesian and English languages. The results of the translations were then compared and analyzed until an agreement was reached; in the second step, the outcomes that had been agreed upon were translated back to English by two interpreters that understood the concept of well-being. In the next stage, the two translators were invited to discuss the results of the back-translation and final interpretations. These were then given to 40 subjects to be worked on and deliberated to arrive at the final adaptation. Similar to the original version of the SCWBS, the Indonesian version consists of 15 items, where 3 (specifically numbers 2, 7, and 13) were expressions of social desirability. Participants were given the following instructions: “The following statement describes your daily condition. Choose the answer that best reflects your current condition.” The responses from the total items were processed using a 5-point Likert scale with a slightly different choice of answers from the original. They were 1 = never, 2 = rare, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = very often.

2.3. Analysis

Construct validity was tested in two stages: the first involved exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and the second involved confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) aided by AMOS version 26 (IBM Corp.). The EFA is very helpful in determining the factor structure of an instrument and is followed by a CFA, which supports the determined factor structure and provides further evidence of construct validity (Fabrigar & Wegener, Citation2012). Therefore, the sample was divided randomly into two subsamples for use in the two-factor analysis, where the EFA employed principal component analysis and varimax rotation. Decisions regarding the number of factors to be retained were determined using the Kaiser-Guttman criterion (eigenvalues > 1), and information from the previous literature on the factors was considered. According to Costello and Osborne (Citation2005), EFA can be said to be fit if a clean factor structure has been obtained, which is declared when the item factor loading value is above 0.3, there are few or no items that are cross-loading, and at least three items are present in each factor. Costello and Osborne (Citation2005) considered a score to be high when it was 0.5, and we used this suggestion as a guide in the EFA.

Thus, a CFA was performed on the second subsample based on the findings from the EFA and previous literature using IBM SPSS AMOS version 26. It was then used to validate the relationship between factors, as well as between each item and factor (Bowen & Guo, Citation2011). Suitability is usually indicated by an insignificant χ2 and by assessing the appropriate range of goodness. The goodness-of-fit index (GFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and comparative fit index (CFI) were used, where a value <0.90 indicated a mismatch, between 0.90 and 0.95, denoted a reasonable fit, while between 0.95 and 1 signified a good fit (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2012). Furthermore, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was highly recommended and was determined, considering the need to consider the number of items estimated in the model. A good fit is indicated by an RMSEA value of ≤.05, while a score between .05 and .08 was regarded as reasonable (Byrne, Citation2016). The internal consistency, or reliability, of the scale was checked using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α) and was considered adequate when α ≥ 0.70 (Devellis, Citation2017).

3. Results

3.1. Number and nature of the factors using exploratory factor analysis

The inter-item correlation matrix showed the absence of multicollinearity because all the correlation coefficients between the items were below 0.8, while the determinant of the matrix was found to be 0.012, which was greater than 0.00001. Additionally, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.895, indicating that the data were capable of being factored in. The minimum level set for this statistic is 0.60 (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2012). Bartlett’s test of roundness χ2 (45) = 809.543, p < 0.001 signified the existence of a pattern of relationships between items. The initial solution yielded a two-factor result by employing the Kaiser-Guttman criterion (Eigenvalues > 1), which is consistent with the literature.

There are several items that are cross loading and there are some items that have a low loading factor. Referring to the opinion of Costello and Osborne (Citation2005) which stated that for a clean factor structure, it is possible to exclude problematic items such as those with low factor load values or that exhibited cross-loading, then only items with a loading factor above 0.5 are included. Therefore, SCWBS, which initially comprised 12 items, became 10 items, and explained 59.817% of the total variance. Finally, the PAF solution of the last two factors explained 59.817% of the total variance, indicating that the exploratory factor analysis results were adequate. This is in line with Hair (Netemeyer et al., Citation2003) who suggested that for the social sciences, EFA outcomes are considered adequate if the total variance explained value is at least 50%. The complete exploratory factor analysis results are presented in Table .

Table 1. Exploratory factor analysis result and descriptive statistics of the final 10-item SCWBS

3.2. Construct validity using confirmatory factor analysis

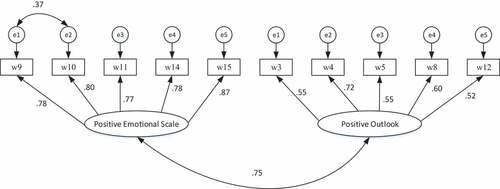

Statistics for the two-factor measurement model of the SCWBS with one second-order factor were found to have good levels of model fit: χ2 (33) = 67,5577, p < .001, GFI = .939, TLI = .945, CFI = .960, and RMSEA = .075. Correlation between item error terms was added to the model, given that they offered the reduction in RMSEA values. One modification was made to the model before the final model. Regarding the goodness-of-fit criteria, the outcomes showed that the chi-square value was significant. However, this did not mean that the SCWBS had a poor level of model fit because, according to Kenny (Citation2020), chi-squares can be influenced by the number of correlations in the model, and a greater number will yield worse results when testing suitability.

An RMSEA value of 0.075 indicated a moderate fit between the hypothetical model and empirical data (Byrne, Citation2016), and the GFI, TLI, and CFI values obtained were greater than 0.900; therefore, the model was found to be adequate. All the 10 items of the SCWBS had factor loading values above 0.5, which were high. Leech et al. (Citation2015) suggested that a factor load value of 0.4 or above is considered high, and Costello and Osborne (Citation2005) suggested that a score was considered high when it was 0.5 or above. Consequently, the analysis results showed that the two factors were significantly interrelated, and an estimated correlation value between dimensions, which was significant but less than 0.85, indicated that the SCWB had good discriminant validity. The results of the CFA are shown in figure .

3.3. Reliability

Cronbach’s α, composite reliability and AVE were used to evaluate internal consistency of the scale. Composite reliability proposed by Raykov and Shrout (Citation2002). In contrast to Cronbach’s α which considers the factor loading on each item to have the same value, the reliability composite takes into account the factor loads on each item. In addition, composite reliability also takes into account measurement error (Blanton & Jaccard, Citation2018). More detailed information is included in Table .

Table 2. Cronbach α, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) for the final 10-item SCWBS

4. Discussion

This study was designed to investigate the dimensions, particularly the nature and number, of the Indonesian version of the SCWBS. Hence, 12 items of the scale were applied to adolescents aged 18 to 21. The SCWBS was developed by Liddle and Carter (Liddle & Carter, Citation2015) in an effort to combine two welfare approaches, the hedonistic and eudaimonic approach, in children ranging from 8 to 15 years. The first approach is represented by the positive emotional state subscale, whereas eudaimonic is represented by a positive outlook. Generally, the results of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis showed that in Indonesia, young adults aged 18–21 do not have significant effects on the factor structure of SCWBS factors. The results of exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis on the Indonesian version of the SCWBS show that there is no change in the factor structure. The factor structure in this version is still the same as the theory proposed by Liddle and Carter (Citation2015).

The EFA results produced two SCWBS factors; two items were excluded due to cross-loading. This was performed in accordance with the suggestions of Costello and Osborne (Citation2005). The authors stated that for a clean factor structure, it is possible to exclude problematic items such as those with low factor load values or that exhibited cross-loading. Therefore, SCWBS, which initially comprised 12 items, became 10, and explained 59.817% of the total variance, indicating that the exploratory factor analysis results were adequate. This is in line with Hair (Netemeyer et al., Citation2003) who suggested that for the social sciences, EFA outcomes are considered adequate if the total variance explained value is at least 50%. Meanwhile, based on these results, item 12, “I’ve been getting on well with people,” which was originally from the positive emotional state became a part of the outlook. This was possible by observing the differences in the individualistic origins of SCWBS that were adapted to collectivist cultures.

Consistent with the present EFA results, the best fitting CFA measurement model was the two-factor measurement model of the SCWBS. Correlation between item error term “I’ve been feeling calm” with item error term “I’ve been in a good mood“ was added to the final model. The similarity of meaning between the two items has encouraged correlated residues. The two items are still in one factor “positive emotional state”, so the two items are “thematically similar”. The researchers suggested several possible sources of correlated residues, one of which was similarity in the meaning of items (Cole et al., Citation2007; Saris & Aalberts, Citation2003).

The reliability of Cronbach’s alpha was also acceptable and similar to the value from the earlier SCWBS version, and in the other studies. A study by Manyeruke et al. (Citation2020) in Zimbabwe showed a Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of 0.75, with a value of 0.79 and 0.70 for the positive emotions subscale and outlook, respectively. Furthermore, research by Bernay et al. (Bernay et al., Citation2016) in New Zealand revealed a reliability value of 0.89. Another study by Amundsen et al. (Amundsen et al., Citation2020) showed the internal consistency of the positive outlook subscale at pre-testing, posttesting, and follow-up, with Cronbach’s α = .81, .82, and, .80, respectively, while the positive emotional state subscales at pretesting, posttesting, and follow-up gave results of .82, .86, and .86, respectively.

A study by Devcich et al. (Devcich et al., Citation2017) conducted in New Zealand showed the internal consistency of the SCWBS as a whole at baseline to be α = 0.87, and for the respective positive emotional state and outlook subscales to be α = 0.80. After the program, the Cronbach’s alpha of the baseline score, positive emotional state, and outlook were α = 0.90, 0.85, and 0.84, respectively, while the intraclass correlation coefficient and test–retest reliability were 0.86. The research by Testoni et al. (Citation2020) in an experimental setting on death education training showed the reliability of the SCWBS scale on the pre- and post-test at α = 0.89. Furthermore, the adaptation study conducted by Haque and Imran (Haque & Imran, Citation2016) showed the results of a test–retest reliability coefficient of 0.791 and a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.746.

The results of the factor structure of the exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were shown to correspond. Regarding the goodness-of-fit criteria, the outcomes showed that the chi-square value was significant. However, this did not mean that the SCWBS had a poor level of model fit because, according to Kenny (Citation2020), chi-squares can be influenced by the number of correlations in the model, and a greater number will yield worse results when testing suitability. An RMSEA value of 0.075 indicated a moderate fit between the hypothetical model and empirical data (Byrne, Citation2016), and the GFI, TLI, and CFI values obtained were greater than 0.900; therefore, the model was found to be adequate. All the 10 items of the SCWBS had factor loading values above 0.5, which were high. Leech et al. (Citation2015) suggested that a factor load value of 0.4 or above is considered high, and Costello and Osborne (Costello & Osborne, Citation2005) suggested that a score was considered high when it was 0.5 or above.

The correlation between factors supported Liddle and Carter’s (Citation2015) view that welfare is a construction that consists of combining hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives. These findings were also in line with the results of a study by Joshanloo (Citation2016) that evaluated the psychometric properties of a measuring instrument developed by Keyes (Citation2002). The instrument was the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form and was developed based on a concept of the SCWBS, where well-being comprised combining hedonic and eudaimonic approaches.

Consequently, the analysis results showed that the two factors were significantly interrelated, and an estimated correlation value between dimensions, which was significant but less than 0.85, indicated that the SCWB had good discriminant validity. Thus, in general it can be concluded that the research objective to adapt the Stirling Child Welfare Scale (SCWBS) for college students in Indonesia was achieved with satisfactory evidence of validity. The Stirling Child Welfare Scale (SCWBS) which was originally made for school-age children can be applied to college students. It will be of benefit to research and practice in Indonesia. The Indonesian version of the SCWBS for adolescents can be used by researchers to examine well-being because it has evidence of good construct validity. Practically, the Indonesian version of the SCWBS can also be used by universities for early detection of students who have low well-being so that they can be treated immediately.

4.1. Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the age range of the study respondents, which was limited to 18 to 21 years, made the Indonesian version of the SCWBS inapplicable to younger children. Therefore, further studies that examine the structure of the SCWBS factor in a wider age range, from 8 to 21 years, are warranted. Second, the respondents were not socially and economically diverse, as most of them were students from middle and upper socioeconomic levels. Thus, additional investigations are required for participants with more diverse subgroups, in terms of, for example, socioeconomic status.

Another limitation is the composition of the participants. Eighty percent of the participants were female, which may have affected the results of the validation of the SCWBS. Therefore, it is necessary to replicate this research by considering the composition of the male and female participants. Finally, the study did not test the predictive and concurrent validity of the criteria, and this creates a need for further research to analyze both parameters. Furthermore, it is necessary to perform psychometric testing using exploratory structural equation modeling for comparison with the CFA.

4.2. Future directions

Further studies that examine the structure of the SCWBS factor in a wider age range, from 8 to 21 years, are warranted. The investigations are required for participants with more diverse subgroups, in terms of, for example, socioeconomic status. Therefore, it is necessary to replicate this research by considering the composition of the male and female participants. Finally, the study did not test the predictive and concurrent validity of the criteria, and this creates a need for further research to analyze both parameters. Furthermore, it is necessary to perform psychometric testing using exploratory structural equation modeling for comparison with the CFA.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study found a two-factor structure of the SCWBS on a college student in Indonesia. The SCWBS measurement with two factors and 10 items was found to be internally reliable. The SCWBS can be considered as a useful tool to explore the emotional and psychological well-being of college students in Indonesia.

Main research activities

This study is part of our research project on the effect of parental marital quality on late adolescent wellbeing. Our first-year study is a meta-analysis study which has found that the quality of parental marriages has a significant effect size on the wellbeing of late adolescents. In addition, in our other meta-analysis, we found that attachment has a significant effect size on the wellbeing of late adolescents. This research was funded by this research was funded by Ministry of Research and Technology and Higher Education of the Republic Indonesia.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ministry of Research and Technology and Higher Education of the Republic Indonesia for providing research grant as the basis for this manuscript. The authors also thank Taylor & Francis Editing Services for language editing of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19518007.v1 and https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19518031.v1.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hepi Wahyuningsih

Hepi Wahyuningsih: Hepi Wahyuningsih is currently lecturer and researcher in Department of Psychology and Master of Professional Psychology at Faculty of Psychology and Socio-Cultural Studies, Universitas Islam Indonesia. She graduated from of Doctoral Program of Psychology, Universitas Gadjah Mada with dissertation focusing on marital quality. She teaches developmental psychology, child abnormal psychology, family psychology, statistics, and research methodology. Her current research interest includes marital quality and relevant issues, religiosity/spirituality, family psychology, educational psychology, and measurement.

References

- Abidin, F. A., Koesma, R. E., Joefiani, P., & Siregar, J. R. (2020). Pengembangan alat ukur kesejahteraan psikologis remaja usia 12-15 tahun [Development of psychological wellbeing measurement for teenagers 12-15 years-old]. Journal of Psychological Science and Profession, 4(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.24198/jpsp.v4i1.24840

- Amundsen, R., Riby, L. M., Hamilton, C., Hope, M., & McGann, D. (2020). Mindfulness in primary school children as a route to enhanced life satisfaction, positive outlook and effective emotion regulation. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00428-y

- Aryono, M. M. (2018). Penyusunan skala well-being anak (CWBS) [Development of childres wellbeing scale]. Widya Warta: Jurnal Ilmiah Universitas Katolik Widya Mandala Madiun, 1, 64–76. http://repository.wima.ac.id/id/eprint/21012/13/1-Penyusunan_skala_.pdf

- Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

- Bernay, R., Graham, E., Devcich, D. A., Rix, G., & Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2016). Pause, breathe, smile: A mixed-methods study of student well-being following participation in an eight-week, locally developed mindfulness program in three New Zealand schools. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 9(2), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2016.1154474

- Blanton, H., & Jaccard, J. (2018). From principles to measurement: Theory-based tips on writing better questions. In H. Blanton, J. M. LaCroix, & G. D. Webster (Eds.), Measurement in social psychology (pp. 1–28). Routledge.

- Bosković, G., & Jengić, V. S. (2008). Mental health as eudaimonic well-being? Psychiatria Danubina, 20(4), 452–455. https://www.psychiatria-danubina.com/UserDocsImages/pdf/dnb_vol20_no4/dnb_vol20_no4_452.pdf

- Bowen, N. K., & Guo, S. (2011). Structural equation modeling. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195367621.001.0001

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concept, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Cole, D. A., Ciesla, J. A., & Steiger, J. H. (2007). The insidious effects of failing to include design-driven correlated residuals in latent-variable covariance structure analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(4), 381. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.4.381

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for getting the most from your Analysis. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 10(7), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868

- Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2008). Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1

- Devcich, D. A., Rix, G., Bernay, R., & Graham, E. (2017). Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based program on school children’s self-reported well-being: A pilot study comparing effects with an emotional literacy program. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 33(4), 309–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2017.1316333

- Devellis, F. F. (2017). Scale development: Theory and applications (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Di Fabio, A., & Palazzeschi, L. (2015). Hedonic and eudaimonic well-being: The role of resilience beyond fluid intelligence and personality traits. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1367. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01367

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2002). Sujective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 463–473). Oxford University Press.

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

- Fabrigar, L. R., & Wegener, D. T. (2012). Exploratory factor analysis : Understanding statistic. Oxford University Press.

- Godfrey, C., Devine-Wright, H., & Taylor, J. (2015). The positive impact of structured surfing courses on the wellbeing of vulnerable young people. Community Practitioner, 88(1), 26–29. https://www.communitypractitioner.co.uk/resources/2017/07/positive-impact-structured-surfing-courses-wellbeing-vulnerable-young-people-?&redirectcounter=1

- Haque, M., & Imran, M. (2016). Adaptation of Stirling Children’s Well Being Scale (SCWBS) in Bangladesh Context. Dhaka University Journal of Biological Sciences, 25(2), 161–167. https://doi.org/10.3329/dujbs.v25i2.46338

- Henderson, L.W., & Knight, T. (2012). Integrating the hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives to more comprehensively understand wellbeing and pathways to wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 196–221. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v2i3.3

- Hinshaw, T., Clift, S., Hulbert, S., & Camic, P. M. (2015). Group singing and young people’s psychological well-being. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 17(1), 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2014.999454

- Joshanloo, M. (2016). Revisiting the empirical distinction between hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of well-Being using exploratory structural equation modeling. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(5), 2023–2036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9683-z

- Kenny, D. A. (2020). Measuring model Fit. David A. Kenny’s Homepage. http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm

- Keyes, C. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

- Leech, N. L., Barret, K. C., & Morgan, G. A. (2015). IBM SPSS for intermediate statistics (5th ed.). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Liddle, I., & Carter, G. F. A. (2015). Emotional and psychological well-being in children: The development and validation of the Stirling Children’s Well-being Scale. Educational Psychology in Practice, 31(2), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2015.1008409

- Manyeruke, G., Çerkez, Y., Kiraz, A., & Çakıcı, E. (2020). Attachment, psychological wellbeing and educational development among child members of transnational families. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry, 21(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.5455/apd.106486

- Maulana, H., Khawaja, N., & Obst, P. (2019). Development and validation of the Indonesian Well‐being Scale. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 22(3), 268–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12366

- Netemeyer, R. G., Bearden, W. O., & Sharma, S. (2003). Scaling procedures. Issues and applications. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985772

- Raykov, T., & Shrout, P. E. (2002). Reliability of scales with general structure: Point and interval estimation using a structural equation modeling approach. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_3

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

- Saris, W. E., & Aalberts, C. (2003). Different explanations for correlated disturbance terms in MTMM studies. Structural Equation Modeling, 10(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1002_2

- Skrzypiec, G., Askell-Williams, H., Zhao, X., Du, W., Cao, F., & Xing, L. (2018). Predictors of Mainland Chinese students’ well‐being. Psychology in the Schools, 55(5), 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22122

- Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (2007). Positive psychology: The scientific and practical explorations of human strengths. In Positive psychology: The scientific and practical explorations of human strengths (pp. 3–22). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2012). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63

- Testoni, I., Tronca, E., Biancalani, G., Ronconi, L., & Calapai, G. (2020). Beyond the wall: Death education at middle school as suicide prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072398

- Tomer, J. F. (2011). Enduring happiness: Integrating the hedonic and eudaimonic approaches. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 40(5), 530–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2011.04.003

- Widiasmara, N., Novitasari, R., Trimulyaningsih, N., & Stueck, M. (2018). School of empathy for enhancing children’s well-being. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 8(8), 230–234. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijssh.2018.V8.966