Abstract

This study aimed to analyze the commitment, preparedness, response, and challenges of risk communication for the prevention, ethics, and academic integrity of COVID-19 in Ethiopian higher education. Higher education is among those sectors seriously affected by the pandemic and associated factors. Since it appeared in the country, various ethical risk responses have been employed to minimize its impacts. Every commitment, response, preparedness, ethics, academic integrity, and risk communication are efforts to curve the impacts that transcend the globe. The study used an institutional-based cross-sectional study design. Data were collected from primary and secondary sources. These were extracted using web-based research from academic research, preparedness, protocols, standards, and risk communication working papers that were prepared for the Ethiopian context and university media sources. Therefore, a web-based search was used to gather information on the preparedness, commitments, performances, and challenges of Ethiopian higher education. Qualitative thematic analysis was used to explore the experiences of Ethiopian higher education. The findings show that higher education is one of the main task forces that support the national response scheme against the pandemic. The government makes an enormous effort to reduce and minimize its impacts. The findings show that higher education as a task force has contributed strongly to national efforts based on research, ethics, academic integrity, humanitarian assistance, online meetings, e-learning, and conferences. Although research focused on knowledge, attitude, and practice to date there has been no clinical research. Research conducted on COVID-19 by academicians (374 academic staff) of 26 universities focuses on KAPs. Besides, e-learning was poorly and unethically managed to support disrupted education. The postgraduate program was facilitated outside of campus through e-learning which eroded academic integrity. However, e-learning is the weakest and unethical way to support undergraduate and even partially postgraduate programs. The Internet infrastructure and the acculturation of student e-learning are problematic. Furthermore, external pressures such as ethnic conflicts, wars, and fragile political situations are causing the reopening to be delayed. In Ethiopian higher education, the overall effort to communicate risks, ethical education, and academic integrity is minimal. It lacks continuity. It lacks academic integrity. Thus, academic ethics is eroded. The challenges are the remaining homework of the universities. I suggest that risk communication, ethical and research-based solutions need to be re-evaluated and re-considered.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The analysis of the efforts of higher education as a task force to minimize the risks of COVID-19 is still critical to handling ethical follow-up in the academic arena. It has been a global issue that has seriously affected the globe. Many have died of the pandemic, and different variants have mutated to destroy the world. Ethiopia has made many efforts to tackle the challenges of the pandemic. The situation of the pandemic reduced the fear of death among the academic community. However, practical reports indicate that the public has been more vulnerable than ever. To avert this undermined situation, higher education can take the lion’s share of the risk and crisis communication. Academic integrity is unable to maintain the status quo. Ethiopian higher education was the best task force to support the national response to the pandemic’s expansion. This study tries to scrutinize those opportunities and challenges that have an impact on the academic integrity and response measures taken by the country.

1. Introduction

Following the communication of the outbreak of pneumonia caused by a novel coronavirus began in December 2019, in China’s Wuhan, the world started to develop different curbing strategies for preparedness, response, commitment, risk communication, prevention, and control mechanisms and tasks. The World Health Organization (WHO) announced, on 30 January 2020, that COVID-19 is a public health emergency of international concern. Since then, COVID-19 has affected 213 countries and territories around the world and two international conveyances. Until the end of June 2021, more than one million coronavirus cases and deaths were reported worldwide. A total of more than 157,072,411 people recovered and survived. Similarly, in Ethiopia, a small number of coronavirus cases, deaths, and recoveries are reported. However, the number of cases reported has declined to this date due to multiple factors. It has left a residue of unprecedented public health challenges worldwide. Recent research indicates that it poses a mental health and socio-economic burden on society. Since it appeared, the national task force has focused on three risk phases: preparedness, response and recovery. Recent research indicates that the pandemic has an impact on the global, social, economic, and political contexts (Chekole et al., Citation2020; Kassie et al., Citation2020; Mega et al., Citation2020). A study outcome shows that the “COVID-19 crisis revealed structural failures in governance and coordination on a global scale” (Hartley & Khuong, Citation2020). Moreover, it could be a global health and economic security threat (Mohammed et al., Citation2020). In general, COVID-19 has affected the public health, economy, and sociopolitical dynamics of every nation. Ethiopia is not exceptional. Likewise, following the WHO endorsement of the pandemic, the Ethiopian government officially, in its risk communication strategy, announced and closed educational institutions on 16 March 2020 to curb and minimize the possible impacts of COVID-19. Besides, Ethiopia declared a 5-month state of emergency to curtail transmission of the coronavirus on 14 April 2020 through banning and restricting movements and activities. Moreover, the Ethiopian government took vigilant measures at the points of entry. Above all, the government took systematic measures in response to the pandemic crisis. The first mobilization effort considered multi-sectoral coordination of existing community mobilization based on the general public and volunteer groups. The second mobilization effort relied on the business community and private sectors through the donation of property and financial aid. Currently, Ethiopia is providing the COVID-19 vaccine but with huge resistance by the people to taking the vaccination. In that phase of mobilization, some private sectors discharged their social responsibility by producing sanitizers, face masks, and alcohol. The last, but not limited to the mobilization of the professional community, were those involved in filling gaps in service. These communities come from academia, professional associations, and researchers. In COVID response and preparedness, the contribution of the higher education institutions (HEIs) community is very huge and supports the government.

All kinds of communication activities during the outbreak are essential for the management of the outbreak risks. Risk communication in this regard is proactive communication that is necessary for an effective response to a real or potential health threat. Risk communication is defined as communication that encourages the public to adopt protective behaviors, allows increased disease surveillance, reduces confusion, and allows better resource utilization (Kebede et al., Citation2020; WHO, Citation2008). More than 1.5 billion students and young people across the world have been affected by school and university closures due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

1.1. Objective

This study explores risk communication, unethical education, and academic integrity as a proactive response communication strategy used in Ethiopian HEIs as one of the task forces to curve the impact of COVID-19. Furthermore, the study outlines the main risk communications used by Ethiopian HEIs during the crisis. Additionally, the study identifies the opportunities and main challenges of academic integrity and ethical education as approached by Ethiopian HEIs to combat COVID-19.

1.2. Study questions

In the current study, I focused my study on two questions: What are the major opportunities in Ethiopian higher education during the risk of pandemic communication and preparedness to curb the impacts of the pandemic? What are the challenges of Ethiopian higher education during the risk of communication and preparedness to curb the impacts of the pandemic? The study considered an integration of two study frameworks: Risk communication Theory and Strengths, Weakness, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis. Thus, a theory of integration combines a single theory with different concepts. The study dealt about how unethical and academic integrity were manifested in the institutions.

2. Theoretical and Analytical Framework

2.1. Risk Communication Theory

Risk communication is a tool for crisis communication. Effective risk communication at both the individual and public levels can play a key role in reducing the negative influence of risk factors. A multisectoral approach is used to make a multilevel intervention. After the pandemic crisis, studies revealed that there are structural failures in governance and coordination on a global scale. This failure is aggravated by misinformation and fake news. Choosing optimal strategies is required to mitigate the effects of risk factors and uncertainties (Hartley & Khuong, Citation2020; Simon & Conner, Citation2020). The study indicates that in the Ethiopian pandemic crisis, sources of information were considered a major factor during communication (Aweke et al., Citation2020). The challenges in risk communication are tremendous. Thus, they are used to improve ways of communicating risk information. Risk communication could be better positioned due to the emergence of new technologies. Reliable and credible information is a key factor in communicating risks effectively. Following the pandemic crisis, “physicians and epidemiologists have explored new ways to educate the public about COVID-19 and protect against misinformation” (Graham, Citation2021). Thus, risk communication is an ongoing communication process that addresses knowledge, attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors related to risks. It can be applied to information and communication; stimulating behavior change and taking protective measures; the issuing disaster warnings and emergency information; and exchange of information and a common approach to risk issues (Berry, Citation2004). Risk reduction is at the center of risk communication. If not handled properly, risk communication is complex and could have an impact on the audience. However, there are some cases where the community is stopped and derived of healthy activities of daily living due to disinformation and misinformation actions (Simon & Conner, Citation2020). Therefore, during COVID-19, disinformation and misinformation are threats to public health responses and risk management. Some community members mentioned the essence of disinformation and misinformation; they also witnessed how these things are facilitated through social media.

Thus, risk communication is finding a comprehensive way to present complex risk issues. In risk communication, social networks and mass media play an important role in exchange of reliable information on risks between communicators and their audiences (Hartley & Khuong, Citation2020). Here, most risk communications are two-way communications that build a consensus between the communicators. In a two-way process, trust and credibility are the fundamental components of risk communication (Walaski, Citation2011).

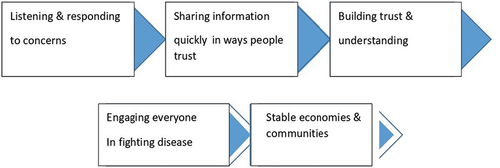

2.2. Continuum of Risk Communication

WHO defines risk communication as “a dynamic process of sharing and responding to information about a public health threat” (WHO, Citation2020). Besides, the essence of its definition, WHO developed a continuum of 5-steps of risk communication (Figure ) to curb a public health threat like COVID-19.

2.3. Ethics and Academic Integrity Nexus

A healthy conversation on academic integrity and ethics will go a long way toward ensuring that the public’s and professionals’ trust is well-placed. New ethical expectations will be imposed on you and your profession as times change and knowledge expands. Therefore, academics must adopt value priorities and activities that represent academic integrity as a result of the increased responsibilities.

2.4. SWOT Analysis

SWOT analysis is a scientific approach that provides us with a lens window to look at the different perspectives from which an organization could function as an open system. As an organization works in a dynamic environment, there could be factors that hinder or facilitate its performance. Internal situations of the organization could coexist with external situations. Both situations, from the inside and outside have the power to shape the culture and performance of the organization. Ultimately, any alteration from the inside and outside of an organization shapes it. Thus, SWOT analysis helps the researcher to understand the dynamics of the organization.

3. Methodology

The intended target of the current study is to analyze the integration of the COVID-19 risk communication, ethics and academic integrity of HEIs in Ethiopia. Qualitative study design and thematic analysis were employed. Furthermore, the SWOT analysis comprises a type of web-based study and an analytical tool employed to evaluate the risk communication and its response to curb COVID-19 impacts by the Ethiopian HEIs. The data was collected based on web-search and Google search. The evidence-based analysis has been conducted as a multi-institution cross-sectional study of HEIs in Ethiopia. An in-depth web-based search were employed. Accordingly, in the analysis, I attempted to evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to combat the pandemic. The SWOT and PEST analysis as a methodology aims to identify favorable and unfavorable factors that may affect the future outcomes of the HEIs in Ethiopia. Therefore, Ethiopian HEIs were the primary source of the qualitative data analysis. I engaged in deep-dig data mining based on the available literature to usually form the SWOT and PEST analysis. Thus, various documents were explored systematically through online search. In this search, published research done by Ethiopian HEIs, academics was collected. I categorized those articles into their types of research, authors’ affiliations, study areas, participants, instruments, findings, and suggestions for improvement. In addition, relevant documents are categorized into thematic areas. The analysis was conducted based on the thematic or categories of the COVID-19 responses. It involves specifying the objective of the task forces and identifying favorable and unfavorable factors for achieving the task force objective. The study period for the current research could be March 2020 to June 2021. In summary, I specifically presented the data gathered for SWOT analysis using tables. For the rest of the presentation, I used description, figures and tables.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Background of the Pandemic, COVID-19, in Ethiopia

The world is in turmoil due to the non-weapon impacts of COVID-19. COVID-19 severely heated the social, political, economic and environmental conditions of the globe. The researchers of COVID-19 compared the pandemic with the Second World War (Akalu et al., Citation2020). The recent emergence of COVID-19 is the world’s largest humanitarian calamity since World War II. Given the lack of an effective treatment or vaccine, improving public awareness, attitudes, and practice, particularly among high-risk groups, is critical to containing the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Ethiopian government took several preventive measures both at community and individual levels. At the community level, the imposed preventive measures are shouting down schools, suspending sporting events and public gatherings; suspending flights to several countries; and introducing a mandatory self-quarantine for 14 days on arrival from abroad. Besides, at the individual level, preventive measures are hand washing; avoiding handshaking and contact with others; social distancing; maintaining respiratory hygiene; wearing masks for health workers and infected groups, and isolation after infection or suspicion of infection.

However, to date (June, 2021), several studies have indicated that the relevance and feasibility of both individual and community level measures heavily depend on how the public perceives the risks and impacts of being infected with the virus (Khosravi, Citation2020). The indicators of the above-mentioned efforts have been kept to a low opportunity window to prevent the pandemic. Scholars emphasize individual and community safety. The major task could be to identify and address factors in the pandemic crisis and in future public health challenges (Amant, Citation2021; Graham, Citation2021).There are also many challenges, such as misinformation, disinformation, rumors and the availability of sources of information (Aweke et al., Citation2020; Hartley & Khuong, Citation2020; Simon & Conner, Citation2020). Since March 2020, only 4,292 deaths have been reported, out of a population of 109 million by COVID-19. This is a rewarding accomplishment, even if it necessitates more stemming and efforts. However, recently, different factors are the challenges remaining to tackle the pandemic crisis. Studies conducted in the course of the pandemic crisis indicate several factors. The following factors were mentioned: a lack of adequate training, a lack of adequate policy, a lack of commitment to information control, a lack of resources, a negative attitude toward COVID-19, poor knowledge and prevention practice, isolation of infected persons, a lack of attention to preparedness and response, combating efforts, a high level of anxiety and information exposure (Birihane et al., Citation2020; Geleta et al., Citation2020; Jemal et al., Citation2020; Kebede et al., Citation2020; Mechessa et al., Citation2020; Tamiru et al., Citation2020; Taye et al., Citation2020; Teshome et al., Citation2020). They are major barriers to reducing the impact of the COVID-19 crisis.

4.2. Risk Communication Strategy Development: Ethiopian Perspective

The Ethiopian government has responded swiftly and boldly to the COVID-19 crisis.

The government initially communicated the outbreak well by providing public health COVID-19 prevention strategies to aware the different organizations, the public and the Ethiopian HEIs. Besides, the Ethiopian government went through a terrain of major tasks of risk communication: (1) strictly followed house to house screenings, diagnostic tests, encouraging production and economic activities to continue during the crisis; (2)the Ethiopian authorities have implemented a strict regime of rigorous contact tracing, isolation, compulsory quarantine, and treatment.

In addition, the task forces organized dormitories for the public universities to increase the capacity of quarantine centers. Above all, the Ethiopian government has relied heavily on community mobilization and public awareness campaigns. Therefore, the government ensured a coherent and patterned public health prevention response by maximizing coordination among public universities at different levels. The Ethiopian government’s COVID-19 strategies must reflect and depend on the local context, the evolving nature of the pandemic, the binding constraints of resource, and the weak international collaboration.

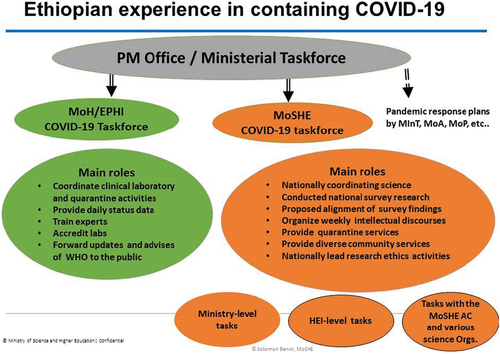

Combating an outbreak requires a well-established system to communicate the risk. Risk communication is a proactive communication tool that helps to make rapid public health responses. One of the most important developments of the risk communication system is the organization of hierarchical responsible bodies from different and different organizations. According to the WHO guideline (WHO, Citation2020) it is possible to avoid miscommunication, confusion and increase protective behaviors “by alerting a population and partners to the risk of infectious disease, surveillance of potential cases increases, protective behaviors are adopted, confusion is limited and communication resources are more likely to be focused”. In the aftermath of the closure of educational systems, the government arranged task forces to mobilize the stakeholders to combat the impacts of COVID-19. One of the task forces in the Ethiopian HEIs sector is the COVID-19 task force of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (MoSHE). MoSHE is responsible for communicating with as well as leading and mobilizing science, higher education and technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in Ethiopia. The task force also organized HEIs-as HEI-levels tasks. Under the umbrella of MoSHE, 45 universities are accommodating nearly one million students. MoSHE communicated with the universities and universities cleared all students to go to their families before the state of emergency. This was the first response and preparedness to fight the HEIs pandemic crisis. The pitfalls of universities for returning students are twofold: Students left the universities without any training on COVID-19 responses to how to minimize its impacts; Students left the university without taking any mission to their community. These are excellent opportunities as part of the COVID-19 campaign to reduce the impacts of potential risks. The following figure (Figure ) shows how universities act as the main sector to participate in the national COVID-19 task forces. Their roles during the pandemic are also briefly described in the areas of research and community services.

Figure 2. Risk communication hierarchical position of HEI during COVID-19 in the task force (MoSHE, Citation2020)

In the case of research, university personnel participated in the study of KAPs, COVID-19 respective measures, and associated factors. Data were collected from health professionals, students, rural communities, city dwellers, civil servants, and vulnerable parts of the population .(Jemal,Citation2020; Birihane et al.,Citation2020; Chekole et al.,Citation2020; Kassie et al.,Citation2020; Mega et al.,Citation2020; Taye et al.,Citation2020; Mechessa et al.,Citation2020; Geleta et al.,Citation2020; Kebede et al., Citation2020; Teshome et al., Citation2020; Tamiru et al.,Citation2020) However, community services have been largely dependent on humanitarian assistance and training. Furthermore, the university community produced different accessible materials such as hand sanitizers and face masks for the local community and for front-line health professionals.

4.3. MoSHE’s risk communication during the COVID-19

HEIs developed different risk communication strategies during the COVID-19 crisis. One of the strategies is to establish a task force in HEIs where the university’s top management establishes and heads a hierarchical task force at the university levels. The other important communication of risks in HEIs during COVID-19 is to develop a webinar for discussions, meetings, and seminars. For example, MoSHE, used one of the leading communication tools, communicated through a webinar developed to promote scientific research in Africa facing COVID-19 to share Ethiopian experiences (Figure ).

Figure 3. Risk communication of MoSHE task force during COVID-19 (MoSHE, Citation2020)

The objective of the webinar was to share national scientific research activities on COVID-19 preparedness and responses during the crisis. It could be one of the examples of developing a webinar to connect HEI officials and academic wings. Similarly, the Ministry held different virtual online meetings with the top management of university decision-making on the current and prospects of the research, community service and teaching-learning processes of the HEIs.

4.4. Media during Risk Communication

The digital era increased the ease of accessibility to disseminate information and communicate with many people instantaneously. The use of these new technologies could become crucial in communicating risk effectively during a pandemic. On Friday 13 March 2020, Ethiopia confirmed and communicated its first case of COVID-19 in the capital, Addis Ababa. The government agreed to share information on COVID-19 activities reported daily by the Ministry of Health through social media and the Ethiopian COVID-19 monitoring platform at www.covid19.et. However, the different mainstream media such as television, radio and newspapers were crucial in stemming the outbreak. They also entertained different types of communication using verbal and nonverbal communication such as public health hand washing strategies. Additionally, universities and MoSHE risk communication strategies rely on Facebook, webinars, emails, social networks, telegrams, and virtual online communications.

Scholars suggest: “One potential way to ensure appropriate risk communication is by using social media channels, and ensuring an ongoing, consistent media presence” (Aweke et al., Citation2020). This argument asserts that the requirement for broader public messaging is efficient in ensuring effective risk communication during outbreaks. Risk communication strategies are useful to communicate uncertainty in HEIs. However, this could be difficult to address for people in developing countries like Ethiopia, where the Internet penetration rate is below 15%. In addition, the assumption seems like an illusion to rural people, where 80% of the population of Ethiopia lives. These factors make risk communication unfeasible in Ethiopia. This opportunity in HEIs could be mandatory to take preventive measures for those who are connected online. However, the online connection blackouts information exchange for several days because the Internet was cut off during the massive killings of the Amhara people and violence in the Oromia region after the assassination of an Oromo singer. For two weeks, the dark side of HEIs’ online learning and risk communication during the COVID-19 crisis was revealed.

4.5. Higher Education Challenges and Responses: Global HEIs Perspectives

The international literature on COVID-19 and HEIs is growing. I found a global literature on “COVID-19 and higher education”. However, a previous survey report (Marinoni et al., Citation2020) on the challenges and responses of HEIs to COVID-19 brought some findings in the middle, May 2020, of the study period of current research (Mar 2020-Jun 2021). It was conducted by the International Association of Universities. It has monitored the impacts of COVID-19 on HEIs around the world. The global survey report focused on the assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on research, teaching and learning, community engagement, enrolment of students and partnership. Therefore, the findings of the report indicated that almost all the HEIs’ teaching and learning were affected face-to-face and turned into distance teaching and learning. Also, the report indicated that mobility is everywhere negative. Furthermore, 80% of the research of HEIs was affected by COVID-19. Further, COVID-19 weakened the partnership. Most of the literature predicted that its impact would remain until the disruption of the spread of the pandemic around the world. It is a multidimensional crisis that affects all of us. Similarly, HEIs from developing countries such as Ethiopian universities are victims of the global experiences mentioned above during the pandemic crisis. The impacts of Ethiopian HEIs on COVID-19 are the most challenged in university contexts of research, teaching and learning, community engagement, student enrollment and partnership. Face-to-face teaching learning is halted and there is no more distance teaching learning for undergraduate classes. Postgraduate classes have totally turned into online learning. However, it was challenged due to Internet disconnect across the country for two weeks amid the 2020 academic year. Recently, university isolation centers were ready to welcome students in the reopening phases amid the pandemic crisis in June 2021.

The most challenging factor after reopening is a response to the post-war law enforcement operation by the Federal government of Ethiopia against the Tigray People Liberation Front (TPLF) armed group in the Tigray region. This might cause a problem of uncertainty during the pandemic crisis on campus activities. However, the reopening has not addressed all batches of university students. The last batch of graduating students was urged to finish their education within two months, which might be expected to compromise the quality of HEIs. As a result, the university is filled with doubts about the impact of COVID-19 on the learning and teaching processes on campus.

4.6. High Level Risk Communication: Ethiopian Perspective

Ethiopia had the highest level of decision-making and the highest level of risk communication. On 14 April 2020, Ethiopia declared a state of emergency to curb transmission of the Corona virus. The government declared a state of emergency for five months to limit the spread of the Coronavirus (COVID-19). The state of emergency was declared under Proclamation 3/2020, also known as the “State of Emergency Proclamation Enacted to Counter and Control the Spread of COVID-19 and mitigate its impact”. Furthermore, the Federal House of Representatives endorsed a seven-member State of Emergency inquiry board to scrutinize its implementation following the Constitution. For five months of the state of emergency, there were different activities banned, restricted, and closed. At all times, all public gatherings were prohibited. There were bans that applied to all religious, governmental, non-governmental, commercial, political, and social gatherings. Public gatherings were restricted to a group of four people where individuals are expected to ensure that they are two meters apart at all times. Different activities: handshaking greetings, land border movement, passenger loads for all national and local journeys, reducing work forces, students and teachers meetings, and measures on social distancing, sporting activities, and children’s playgrounds were closed. Penalties: Any person failing to comply with these obligations will face up to three years of imprisonment.

4.7. Research Based Risk Communication: HEIs Perspective

The researcher used key major terms to find research conducted in the Ethiopian context since the outbreak of the pandemic, COVID-19. The terms used to search were “knowledge”, “attitude”, “practice”, “COVID-19”, “Ethiopia”, “pandemic”, “prevention”, and “control”. Besides, other technical terms are used to explore the articles. Based on these search terms, the researchers found fifty-one articles published from Mar 2020 to Jun 2021. This research was published until the beginning of January 2021 by the HEIs academic staff. One of the limitations of the current study is that it used Internet web-based search. In fact, the study was based on data available until the beginning of Jul 2020. This study came to its current format by extending to the beginning of Jun 2021. After July 2020, many papers will be published in different journals. Besides, several activities are accomplished by the university community. In addition to the above search terms, I tailored journals indexed on Scopus, PubMed and Web of Science for the current study. Almost the majority of the papers focused on the Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices (KAP) study approach. Therefore, the articles focus on preventive and control methods of public health risk communication. To this end, the research was not considered clinically based research. Almost all the articles used a cross-sectional study design. The critical analysis of web and institutional-based cross-sectional studies has come up with some results. Accordingly, (March 2020 to Jun 2021) 374 academic staff participated in the COVID-19 research from twenty-one Ethiopian HEIs. Fifty-one articles were published during this time period. Seventy-nine researchers published articles in reputable and peer reviewed journals. The outcome of most research indicates that they are nearly similar. Almost all articles focus on preventive and control methods of public health risk communication. The 51 articles’ thematic findings and respected suggestions are summarized as follows (Table ).

Table 1. COVID-19 minimum research articles and their respective findings (March 2020 to June 2021)

4.8. Higher Education Institutions in Ethiopia

Universities across the country are setting up institution-wide task forces to mitigate the impact of the pandemic. Therefore, the environment of HEIs’ has changed tremendously. COVID-19 in Ethiopia forced 45 public institutions to fundamentally alter their operations and delivery modalities. However, it poses several challenges to the teaching-learning system. The disruption was critical to the lives of students and the academic staff. Students did not leave HEIs with a long-term plan. This manpower was left idle without any mission and commitment to improving the situation of COVID-19 among the community. The reopening could also not be challenge-free. After a partial announcement to graduating classes, a war of law enforcement operation by the federal government of Ethiopia against the TPLF armed group in the Tigray region began. The security situation disrupted the partial reopening and it was postponed for several months. In the middle of December 2020, other partial renouncements are in place. The graduating students are scheduled to finish their program in two months with an intensive delivery system. Afterward, the rest of the university students from all batches join the HEIs in Ethiopia. There is no doubt that HEIs in Ethiopia will recover. However, it requires great commitment from students, academic leaders and staff. Therefore, this study makes an assessment using design-reality gap analysis.

4.9. SWOT Analysis of COVID-19 Preparedness, Response and Recovery Strategies in Ethiopian HEIs

SWOT analysis refers to the evaluation of various strengths (S), weaknesses (W), opportunities (O), threats (T), and other factors that influence a fight against COVID-19. It comprehensively, systematically, and accurately describes the scenario of COVID-19 in Ethiopian HEIs. The results could help the COVID-19 task forces formulate the corresponding strategies, plans, and countermeasures. This method could be used to identify favorable and unfavorable factors, solve current problems in a targeted manner, recognize challenges and obstacles faced, and formulate strategic plans to guide scientific decisions (Eaton, Citation2020). Consequently, the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats manifested in Ethiopian HEIs are summarized in the preceding section (Table ).

Table 2. SWOT analysis of Ethiopian higher education risk communication strategies

4.10. PEST analysis

Ethiopian HEIs are not Islands. Universities have been considered a mini Ethiopia where different ethnic groups live. Thus, students attend universities from different parts of the country. They are susceptible to external pressures: Analyses of politics, economics, social issues, and technology (PEST; Table ).

Table 3. PEST analysis that enhance and limit the universities response to the pandemic crisis

4.11. Contemporary Impacts of the Pandemic on Academic Integrity

It was difficult to maintain the academic integrity and ethics of higher education. It happened after the reopening of higher education in Ethiopia. These manifested in the urge to finish and compensate to teach students at the desired level of academic hours. The chapters were reduced to below the standard. The assessment was also reduced to below the standard. Thus, the quality of higher education is being undeniably minimized. The exams for graduate students were free and they were taken and submitted from their remote homes. Some of the students were unable to submit their work on time due to unavailable and poor Internet network problems. The result indicates that academic misconduct was the major challenge in Ethiopian higher education that eroded academic integrity. Research conducted at the University of Calgary also confirmed that this kind of challenge was faced during the pandemic response (Eaton, Citation2020). Thus, a change in the educational paradigm was observed in Ethiopian higher education. The unethical performance of the students that was manifested in cheating, sabotage, fabrication, and plagiarism followed. I witnessed postgraduate students in my department who were dismissed at the final thesis defense due to plagiarism. Another noteworthy element is the closure of institutions, which has resulted in unexpected distance and online learning. Distant learning, on the other hand, is limited in developing countries by a lack of network infrastructure, computers, and Internet access.

4.12. Effects of the Pandemic on Ethical Education

Several instructors were admitted to the COVID-19 recovery room a year after the outbreak was reported. Negligence in following the standard of COVID-19 responses was observed and reported on campuses. Students refused to wear face masks or follow the pandemic precautions outlined by MoSHE in accordance with the Ethiopian Public Institute norms and protocols for preventing COVID-19.

4.13. Conclusion

The Ethiopian government had a rapid response to COVID-19. The government has initially established a national task force to mobilize and prevent the pandemic in the third phase of its mobilization efforts. Public health risk communication is argued to be effective in minimizing the impact of COVID-19 during the pandemic. Ethiopian schools were closed in March, which was the first important decision to safeguard schoolchildren. The first important decision is to protect schoolchildren. Following the COVID-19 case report, the HEIs banned face-to-face communication on their campuses. It was followed by the shutting down of on-campus education. As a result, the students were forced to go home. In addition, following the shutdown, the government put the highest level of risk on communication by declaring a state of emergency, which could also be applied to universities. The state of emergency banned all gatherings and restricted different activities. Lockdown is the threshold of a state of emergency. To this end, higher education institutions have shown their respect for citizens by providing research and innovation work, awareness-raising, hygiene, mouth and nose masks, and identification and sample tests. The postgraduate program outside of the campus decided and supported by e-mail and telegram has continued. However, the undergraduate program was halted during the pandemic. Still, some other universities could not function properly due to precipitated ethnic conflicts on different campuses. The second reopening announcement is in place for the graduating classes of the last batch to complete in two months. They both graduated.

The result shows that Ethiopian HEIs paved the way for staff to investigate COVID-19. During the shutdown, 374 academic staff participated in COVID-19 research. Thus, 51 pieces of research have been published in international journals. These articles contain a majority of the research conducted on the knowledge, attitude and perception (KAP) of COVID-19. Almost all of them used a cross-sectional study design. The weakness of the previous research was that they did not make any clinical-based attempts. However, their findings highlighted and suggested the use of risk communication strategies to curb the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ethiopia. More importantly, HEIs engaged in training the community, humanitarian aid and production of sanitizers, masks, and providing campuses for quarantine centers, and offered other costs of effective equipment, research, and innovations during the pandemic. The adaptation of digital risk communication during meetings, postgraduate student learning, and graduation is the new organizational culture that has been used for several months. However, due to the Internet connection and fragile political conflicts, there were many disruptions. The major weaknesses are weak clinical research outputs, being unable to continue undergraduate education, and the partial reopening in December 2020, and a small number of research outputs relative to the huge number of academic staff and the availability of their resources. Delay of partial reopening due to, beginning early November 2020, and war of law enforcement operation by the Federal government of Ethiopia against the TPLF armed group in the Tigray region. Therefore, the participation and efforts of Ethiopian HEIs in the national task force for COVID-19 prevention have been huge. Although huge efforts are underway, risk communication is currently at the minimal stage of the efforts to reduce the impact of COVID-19. In principle, the government sent ethical standards and directives regarding how to conduct classes at the beginning of COVID-19 reopening. On campus, preparedness for COVID-19 is not as serious. Above all, ethics and academic integrity were eroded. I suggest that the universities task force work on the implementation of the directives through a strict monitoring and evaluation system.

4.14. Limitation of the current study

Research may be conducted but it is invisible online. The current study did not consider all online publications. According to the refined criteria, Ethiopian HEIs only consider journals indexed with Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus. Therefore, the inclusion-exclusion criteria can offend scholars who have published in journals that could not be included in this criterion. The other limitation is that all universities may have had different contributions during the pandemic. This kind of exploratory study is important to get the details of a problem by considering the grassroots level study. This kind of study requires an institutional study.

4.15. Implication of the study

The study has implications for developing and improving e-learning systems, to further prevent mechanisms of risk communication. It also improves the academic integrity of higher education. The study improves existing research practices in the higher education system. It can, moreover, be an input for higher education to handle crisis situations in the learning-teaching process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mr Mekonnen Hailemariam Zikargae

Mekonnen Hailemariam Zikargae received his BA Degree in Ethiopian Languages and Literature(Culture and Communication) and MEd Degree in Multicultural and Multilingual Education from Addis Ababa University. He has been started working at Bahir Dar University in the Department of Journalism and Communications since 2004. He was a Ph.D. research fellow, NORPART 2016/10,471:’ Enhancing Norway- Ethiopia Relations in Journalism and Communication Education and Research’ NLA University College. He was joined the Department Of Journalism and Media Studies NLA Kristiansand, Gimlekollen, Norway MA in Global Journalism course: Global Media Ethics, NLA University College, Kristiansand, Norway (Feb 22- 21 May 2018). He is now an Assistant Professor in Journalism, Media and Communication. Besides, he is a Ph.D. Candidate in Media and Communication at Bahir Dar University.

References

- Abate, H., & Mekonnen, C. K. (2020). Knowledge, attitude, and precautionary measures towards COVID-19 among medical visitors at the University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital northwest Ethiopia. Infection and Drug Resistance, 13, 4355–17. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S282792

- Abebe, A., Mekuria, A., & Balchut, A. (2020). Awareness of health professionals on COVID-19 and factors affecting it before and during index case in north Shoa zone. Infection and drug resistance. 2020. Vol. 13 (Dove Press),2979–2988. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S268033.

- Adhena, G., & Hidru, H. D. (2020). Knowledge, attitude, and practice of high-risk age groups to coronavirus disease-19 prevention and control in Korem district, Tigray, Ethiopia: Cross-sectional study. Infection and Drug Resistance, 13, 3801–3809. DOI. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S275168

- Akalu, Y., Ayelign, B., & Molla, M. D. (2020). Knowledge, attitude and practice towards covid-19 among chronic disease patients at Addis Zemen hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Infection and Drug Resistance, Volume 13, 1949–1960. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S258736

- Alemu, Y. (2020). Predictors associated with COVID-19 deaths in Ethiopia. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 2769–2772. DOI. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S279695

- Amant, K. (2021). creating scripts for crisis communication: covid-19 and beyond. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 35(1), 126–133. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2021.15

- Andarge E., Fikadu, T., Temesgen, R., Shegaze, M., Feleke, T., Haile, F., Endashaw, G., Boti, N., Bekele, A., Glagn, M. . (2020). Intention and practice on personal preventive measures against the COVID-19 pandemic among adults with chronic conditions in southern Ethiopia: A survey using the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 13, 1863–1877. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S284707

- Andualem, H., Kiros, M., Getu, S., & Hailemichael, W. (2020). Immunoglobulin G2 antibody as a potential target for COVID-19 vaccine. ImmunoTargets and Therapy, 9, 143–149. DOI. https://doi.org/10.2147/ITT.S274746

- Asefa A., Qanche, Q., Hailemariam, S., Dhuguma, T., Nigussie, T. . (2020). Risk perception towards COVID-19 and its associated factors among waiters in selected towns of southwest Ethiopia. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 2601–2610. https://doi.org/10.2147/rmhp.s276257

- Asemahegn, M. (2020). Factors determining the knowledge and prevention practice of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 in Amhara region, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional survey. Tropical Medicine and Health, 48(72), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-020-00254-3

- Asemelash D., Fasil, A., Tegegne, Y., Akalu, T.Y., Ferede, H.A. and, Aynalem, G.L. (2020). Knowledge, attitudes and practices toward prevention and early detection of COVID-19 and associated factors among religious clerics and traditional healers in Gondar town, northwest Ethiopia: A community-based study. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. DOI, 13, 2239–2250. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S277846

- Asnakew, Z., Asrese, K., & Andualem, M. (2020). Community risk perception and compliance with preventive measures for COVID-19 pandemic in Ethiopia. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 2887–2897. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S279907

- Aweke, Z., Jemal, B., Mola, S., & Hussen, R. (2020). Knowledge of COVID-19 and its prevention among residents of the Gedeo zone, south Ethiopia. Sources of information as a factor. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 361, 1-6 1955–1960. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2020.1835854

- Aylie, N. S., Mekonen, M. A., & Mekuria, R. M. (2020). The psychological impacts of covid-19 pandemic among university students in bench-sheko zone, south-west Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 813–821. DOI. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S275593

- Bahrey, D. T., Tukue, G. G., & Teklemariam, G. D. (2020). Knowledge, attitude, practice and psychological response toward COVID-19 among nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak in northern Ethiopia, 2020. New Microbes and New Infections, 38(C), -, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100787

- Berry, D. C. (2004). Risk, communication and health psychology. In S. Payne & S. Horn (Eds.), Health Psychology (pp. 1–167). Open University Press.

- Birihane, B. M., Bayih, W. A., Alemu, A. Y., & Belay, D. M. (2020). Perceived barriers and preventive measures of COVID-19 among healthcare providers in debretabor, north central Ethiopia, 2020. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 2699–2706. DOI. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S287772

- Chekole, Y. A., Minaye, S. Y., Abate, S. M., & Mekuria, B. (2020). Perceived stress and its associated factors during COVID-19 among healthcare providers in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Advances in Public Health, 2020, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5036861

- Demsie D.G., Gebre , A.K., Yimer, E.M., Alema, N.M., Araya , E.M., Bantie, A.T., Alllene, M.D., Gebremedhin, H., Yehualaw, A., Tafere, C., Tadese, H.T., Amare, B., Weldekidan, A.E. and, Gebrie, D. (2020). Glycopeptides as potential interventions for COVID-19. Biologics: Targets and Therapy. DOI, 14, 107–114. https://doi.org/10.2147/BTT.S262705

- Deriba B.S., Geleta, T.A., Beyane, R.S., Mohammed, A., Tesema, M. and, Jemal, K. (2020). Patient satisfaction and associated factors during COVID-19 pandemic in north Shoa health care facilities. Patient Preference and Adherencea. DOI, 14, 1923–1934. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S276254

- Eaton, S. E. (2020). Academic integrity during COVID-19: Reflections from the university of calgary. Journal of Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration and Management, 18(1), 80–85. https://prism.ucalgary.ca/handle/1880/112293

- Gabore, S. (2020). Western and Chinese media representation of Africa in COVID-19 news coverage. Asian Journal of Communication, 30(5), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2020.1801781

- Gebrie, D., Getnet, D., & Manyazewal, T. (2020). Efficacy of remdesivir in patients with COVID-19: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ Open, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2062892

- Geleta T.A., Deriba, B.S., Beyane, R.S., Mohammed, A., Birhanu, T. and, Jemal, K. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic preparedness and response of chronic disease patients in public health facilities. International Journal of General Medicine, 13, 1011–1023. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S279705

- Girma, S., Alenko, A., & Agenagnew, L. (2020). Knowledge and precautionary behavioral practice toward covid-19 among health professionals working in public university hospitals in Ethiopia: A web-based survey. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 1327–1334. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S267261

- Graham, S. (2021). Misinformation Inoculation and Literacy Support Tweetorials on COVID-19. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 35(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651920958505

- Haftom M., Petrucka, P., Gemechu, K., Mamo, H., Tsegaye, T., Amare, E., Kahsay, H. and, Gebremariam, A. (2020). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards covid-19 pandemic among quarantined adults in tigrai region, Ethiopia. Infection and Drug Resistance, 13, 3727–3737. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S275744

- Hajure, M., Tariku, M., Mohammedhussein, M., & Dule, A. (2020). Depression, anxiety and associated factors among chronic medical patients amid COVID-19 pandemic in mettu karl referral hospital. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2020.,Vol. 16,2511–2518. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S281995.

- Hartley, K., & Khuong, V. M. (2020). Fighting fake news in the COVID-19 era: Policy insights from an equilibrium model. Policy Sciences, 53(4), 735–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-020-09405-z

- Jemal B., Aweke, Z., Mola, S., Hailu, S., Abiy, S., Dendir, G., Tilahun, A., Tesfaye, B., Asichale, A., Neme, D., Regasa, T., Mulugeta, H., Moges, K., Bedru, M., Ahmed, S.and, Teshome, D. Mohamedrabi Bedr, (2020). Knowledge, attitude and practice of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 and its prevention in Ethiopia: A multicenter study. Researchsquare:vol 9 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121211034389

- Kassa, A. M., Bogale, G. G., & Mekonen, A. M. (2020). Level of perceived attitude and practice and associated factors towards the prevention of the covid-19 epidemic among residents of Dessie and kombolcha town administrations: a population-based survey. Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine, 11, 129–139. DOI. https://doi.org/10.2147/RRTM.S283043

- Kassaw, C. (2020). The magnitude of psychological problem and associated factor in response to COVID-19 pandemic among communities living in addis ababa, Ethiopia, march 2020: A cross-sectional study design. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 631–640. DOI. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S256551

- Kassie, B. A., Adane, A., Kassahun, E. A., Ayele, A. S., & Belew, A. K. (2020). Poor COVID-19. Preventive Practice among Health Care Workers in Northwest Ethiopia, 2020. Advances in Public Health, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7526037

- Kebede Y., Birhanu, Z., Fufa, D., Yitayih, Y., Abafita, J., Belay, A., Jote, A.and, Ambelu, A., et al. (2020). Myths, beliefs, and perceptions about COVID-19 in Ethiopia: A need to address information gaps and enable combating efforts. PLOS ONE:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243024

- Kebede, Y., Yitayih, Y., Birhanu, Z., Mekonen, S., & Ambelu, A. (2020). Knowledge, perceptions and preventive practices towards COVID-19 early in the outbreak among Jimma University Medical Center visitors, Southwest Ethiopia. PLOS ONE, 15(5), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233744

- Khosravi, M. (2020). Perceived risk of COVID-19 pandemic: The role of public worry and trust. Electronic Journal of General Medicine, 17(4), em203. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.551004

- Mamo Y., Asefa, A., Qanche, Q., Dhuguma, T., Wolde, A. and, Nigussie, T. (2020). Perception toward quarantine for COVID-19 among adult residents of selected Towns in Southwest Ethiopia. International Journal of General Medicine. DOI, 13, 991–1001. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S277273

- Marinoni, G., Land, H. V., & Jensen, T. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on higher education around the world: A global survey report. IAU. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010369

- Mechessa D.F., Ejeta, F., Abebe, L., Henok, A., Nigussie, T., Kebede, O. and, Mamo, Y. (2020). Community’s knowledge of COVID-19 and its associated factors in Mizan-Aman Town, southwest Ethiopia, 2020. International Journal of General Medicine. DOI, 13, 507–513. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S263665

- Mega T.A., Feyissa, T.M., Bosho, D.D., Goro, K.K. and, Negera, G.L. (2020). The outcome of hydroxychloroquine in patients treated for COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Respiratory Journal, 2020, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4312519

- Mohammed H., Olijira, L., Roba, T.K., Yimer, G., Fekadu, A. and, Maneyazewal, T. (2020). Containment of COVID-19 in Ethiopia and implications for tuberculosis care and research. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 9(131), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00753-9

- MoSHE. (2020). A webinar on promotion of scientific research in Africa. https://www.moshe.gov.et/viewNews/192

- Mulu G.B., Kebede, W.M., Worku, S.A., Mittiku, Y.M. and, Ayelign, B. (2020). Preparedness and responses of healthcare providers to combat the spread of COVID-19 among North Shewa Zone hospitals. 2020. Infection and Drug Resistance, Vol.13,3171–3178. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S265829.

- Obsu, L. L., & Balcha, S. F. (2020). Optimal control strategies for the transmission risk of COVID-19. Journal of Biological Dynamics, 14(1), 590–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513758.2020.1788182.

- Selam, M. (2020). Hand sanitizers marketed in the streets of addis ababa, Ethiopia, in the Era of COVID-19: A quality concern. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 9, 2483–2487. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S284007

- Selam M.N., Bayisa, R., Ababu, A., Abdella, M., Diriba, E., Wale, M. and, Baye, A.M. (2020). Increased production of alcohol-based hand rub solution in response to COVID-19 and fire hazard potential: Preparedness of public hospitals in addis ababa, Ethiopia. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. DOI, 13, 2507–2513. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S279957

- Shigute, Z., Derseh, A., Alemu, G., & Bedi, A. (2020). Containing the spread of COVID-19 in Ethiopia. Journal of Global Health, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010369

- Simon, E., & Conner, A. (2020, August 18). Fighting coronavirus misinformation and disinformation: Preventive product recommendations for social media platforms. Retrieved from Center for American Progress.https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/technology-policy/reports/2020/08/18/488714/

- Tamiru, et al. (2020). Community level of COVID-19 information exposure and influencing factors in northwest Ethiopia. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 2020, 2635–2644. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S280346

- Tariku, M., & Hajure, M. (2020). Available evidence and ongoing hypothesis on corona virus (COVID-19) and psychosis: Is corona virus and psychosis related? A narrative review. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 701–704. DOI. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S264235

- Taye G.M., Bose, L., Beressa, T.B., Tefera, G.M., Mosisa, B., Dinsa, H., Birhanu, A. and, Umeta, G. (2020). COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, and prevention practices among people with hypertension and diabetes mellitus attending public health facilities in ambo, Ethiopia. Infection and Drug Resistance, 13, 4203–4214. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S283999

- Tesfaye, Z. T., Yismaw, M. B., Negash, Z., & Ayele, A. G. (2020). COVID-19-related knowledge, attitude and practice among hospital and community pharmacists in addis ababa, Ethiopia. Integrated Pharmacy Research and Practice, 9, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.2147/IPRP.S261275

- Teshome, et al. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder and its associated factors among health care workers fighting COVID-19 in southern Ethiopia. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 907–917. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S282822

- Tiruneh, F. (2020). Clinical profile of covid-19 in children, review of existing literatures. Pediatric Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 11, 385–392. https://doi.org/10.2147/PHMT.S266063

- Tolu, L. B., Ezeh, A., & Feyissa, G. T. (2020). How prepared is Africa for the COVID-19 pandemic response? The case of Ethiopia. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, Volume 11, 771–776. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S258273. DOI.

- Tolu, L. B., Feyissa, G. T., Ezeh, A., & Gudu, W. (2020). Managing resident workforce and residency training during COVID-19 pandemic: scoping review of adaptive approaches. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 11, 527–535. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S262369

- Wake, A. (2020). Knowledge, attitude, practice, and associated factors regarding the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Infection and Drug Resistance, 13, 3817–3832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105286

- Walaski, P. (2011). Risk and crisis communications: methods and messages. WILEY.

- Wang, J., & Wang, Z. (2020). Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis of China’s prevention and control strategy for the COVID-19 epidemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2235. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072235

- WHO. (2008). world health organization outbreak communication planning guide. https://www.who.int/ihr/elibrary/WHOOutbreakCommsPlanngGuide

- WHO. (2020). Risk communication save lives and livelihoods. In Global solidarity.

- Wolka E., Zema, Z., Worku, M., Tafesse, K., Anjulo, A.A., Takiso, K.T., Chare, H. and, Kelbiso, L. (n.d.). Awareness towards corona virus disease (COVID-19) and its prevention methods in selected sites in Wolaita zone, southern Ethiopia: A quick, exploratory, operational assessment. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. DOI, 13, 2301–2308. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S266292

- Wondimu, W., & Girma, B. (2020). Challenges and Silver Linings of COVID-19 in Ethiopia –Short Review. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 13, 917–922. DOI. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S269359

- Zikargae, M. (2020). COVID-19 in Ethiopia: Assessment of how the Ethiopian government has executed administrative actions and managed risk communications and community engagement. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 2803–2810. DOI. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S278234