Abstract

This theory-based article explored the role of educational and learning capitals in the education of gifted learners in Lebanon. The article introduced the educational system in Lebanon, the impact of the Syrian crisis, refugee challenges to gifted education in Lebanon, the conception of giftedness, expenditures on schools, and higher education institutions. The paper provided a comprehensive categorization of learning resources including ten educational and learning capitals in relation to gifted education in Lebanon. Evidence-based literature was constructed on each of the educational and learning capitals. Several conclusions and implications were introduced in relation to gifted education expenditures, gifted conceptions and identification, gifted teacher preparation, and gifted learning resources management.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The education of the gifted in Lebanon encounters several challenges. First, there is no governmental mandate or official educational policies to serve gifted learners in public and private education sectors. Second, there is a lack of understanding of the concept of giftedness in schools and higher education institutions. Third, there is a lack of diagnostic and assessment tools in Arabic for the identification of gifted children. Fourth, several populations of gifted children are neglected and marginalized, such as twice-exceptional children, and gifted refugees. Fifth, there is a lack of pre-service and in-service academic and professional programs on gifted education in Lebanese higher education institutions. Sixth, there is a lack of services, resources, and facilities for gifted children. Seventh, there is a lack of governmental and non-governmental funds for projects and special programs for gifted learners. Initiatives for serving gifted learners are mostly implemented in the private education sector.

1. Lebanon profile

Lebanon is one of the smallest countries in the Arabic world (10,452 square kilometers), approximately the size of the state of Connecticut in the United States. The current population of Lebanon is 6,825,445, based on United Nations Worldometer (Citation2021). Lebanon has the highest per capita refugee population in the world, hosting an estimated 1.5 million Syrians (UNHCR, Citation2021), and 174,000 Palestinians (ICMPD, Citation2019). The official language used in Lebanon is Arabic, with additional use of French, English, and Armenian (”INEE,” Citation2020). Lebanon’s literacy rates (95.07%) are higher than the average rates in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region (Abdul-Hamid et al., Citation2017).

To understand the status and significance of gifted education in Lebanon, it is particularly crucial to introduce and understand the Lebanese educational system, provisions and school enrolment, the impact of the Syrian refugee and Palestinian crises, and the status of the higher educational institutions in the country.

2. Structure of the educational system in Lebanon

The structure of the educational system in Lebanon consists of a two-year cycle of preschool education, nine years of compulsory basic education, and three years of secondary academic or vocational education after which the students sit for a General Certificate of Secondary Education Exam—Baccalauréat (or Terminale). Formal education at schools is structured in three phases: (a) pre-school education (ages 03–05), (b) basic education (ages 6–14), divided into cycle 1 (Grades 1 to 3) cycle 2 (Grades 4 to 6), and cycle 3 (Grades 7 to 9), and (c) secondary education (ages 15–18; Grades 10–12), sometimes known as cycle 4. Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) is considered a formal education (as a parallel option after cycle 3; Vlaardingerbroek et al., Citation2017). The system requires an examination filter at the end of cycle 3 (i.e. After Grade 9) and a terminating examination at the end of cycle 4. These examinations commonly remain referred to as the Brevet and Baccalauréat (or Terminale) respectively. The main three languages, English and/or French with Arabic are taught from early years in Lebanese schools. English or French are the mandatory media of instruction and assessment for mathematics and three science subjects (Biology, Chemistry, and Physics) for all schools (43% French, 33% English, and 23% English & French; CERD, Citation2020; Vlaardingerbroek et al., Citation2011).

3. Educational provision and school enrollment in Lebanon

The number of students for the 2019–2020 school year in all education sectors in Lebanon reached 1,069,826 including 3,614 students from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) schools. The majority of students are Lebanese (85.2%), followed by Syrians (8.8%), Palestinians (4.6%), and other nationalities (1.4%). According to the “Statistical Bulletin for the academic year 2019–2020” issued by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE) and the Center for Educational Research and Development (CERD), there are 2,861 schools in Lebanon distributed as follows: Public schools (43%), Private schools (57%), among which free schools (12%), with charges (42%), and UNRWA schools (2%). The number of schoolteachers and administrators is 101,137 (19,860 males, 81,277 females; CERD, Citation2020).

Table shows that slightly less than two-thirds of students attend private subsidized or non-subsidized schools, approximately one-third attend public schools, whereas only 3.3% attend UNRWA schools that cater to Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. Most students (52.2%) are enrolled in schools in Lebanon that are registered in private fee-paying schools. It is worth noting that school enrollment rates for females and males are very similar in Lebanon at all school types, with a slight increase in female enrollment at public and UNRWA schools (CERD, Citation2020). The school enrollment rate at the elementary level, for both males and females, is very high. The CERD report in 2020 reveals results touching 98% and 95% respectively for age groups (5–9) and (10–14), which declined to approximately 70% for the age group (15–19) (CERD, Citation2020).

Table 1. Students’ and teachers’ distribution across schools in Lebanon for the academic year 2019–20

In Lebanon, there is no mandate to serve gifted learners in public and private education sectors (Al-Hroub & El Khoury, Citation2018a). However, initiatives for serving gifted learners are mostly implemented in the private education sector. For example, progress was made in some private Lebanese schools to develop activities and special programs for gifted learners (e.g., LWIS-City International, Rahmeh, Ghadi center; WCGTC, Citation2019, Citation2020), yet these programs are not theory-based (Al-Hroub & El Khoury, Citation2018a; Sarouphim, Citation2009). In addition, no scientific data are available on the effectiveness and impact of these special programs (Alameddine, Citation2016).

4. Education for refugee children in Lebanon

The education of refugees (and non-refugees) in Lebanon is plagued by the lack of financial and human resources, a large number of refugees, the emphasis on regular teaching practices (Al-Hroub, Citation2013), and the absence of a national educational vision for serving gifted and talented students (Al-Hroub & El Khoury, Citation2018a). The educational system lacks the identification protocols to identify gifted students (Al-Hroub & El Khoury, Citation2018a) and lacks qualified teachers for gifted students in schools. In addition, there are no special schools or well-grounded programs for gifted refugee students. Accordingly, no official records, studies, or statistics indicate the ratio of gifted (refugee or local) students in regular classrooms or schools (CERD, Citation2020). We discuss below the greatest barriers to the education of gifted Syria and Palestine refugees.

4.1. The Impact of the Syrian Refugee Crisis

Official reports estimated the number of Syrian refugees in Lebanon at 1.5 million, representing a large percentage of the total population (UNHCR, Citation2021). In addition, recent reports indicated that Lebanon hosts 660,000 school-age Syrian refugee children, yet 30% have never attended school, and almost 60% were not enrolled in school in recent years (Human Rights Watch, Citation2021). The majority of refugees are settled in the most vulnerable areas in Lebanon with the lowest rates of educational attainment due to the limited socioeconomic means of most families and the lack of educational resources in public schools in these areas (Habib, Citation2019).

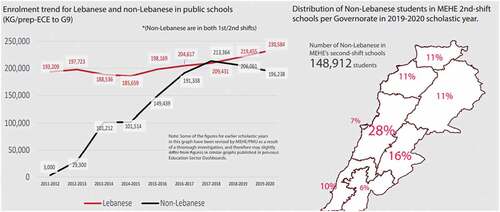

CERD (Citation2020) reported variations in the school enrollment of Syrian children across regions of the country. In some areas of the Bekaa, refugee children make up 40% of the student body. Figure shows the distribution of Syrian students across the public schools in Lebanon within each governorate. Schools in Mount Lebanon have the largest intake of Syrian refugee children (28%) followed by schools in the Bekaa (14%) and Baalbeck Al Hermel (12%; CERD, Citation2020). It is also important to note the sharp drop in the number of Syrian students enrolled in the intermediate school, whereby in some cases it decreases by almost half, such as in Mount Lebanon. Additionally, enrollment in grades 7–9 seems to be the lowest across all governorates.

Figure 1. Enrolment Trends for Lebanese and Non-Lebanese in Public Schools (2011–2020) (Interagency Coordination, Citation2020, p. 1)

Figure also illustrates the enrollment trends for Lebanese and non-Lebanese in public schools over the past ten years. For the 2020–21 school year, 273,500 Lebanese children enrolled in public primary schools, up from 230,584 last year and 219,445 in 2018–19, the last full school year before the Lebanese revolution, economic crisis, and COVID-19 pandemic, according to MEHE. Meanwhile, the total number of Syrian children enrolled in public primary schools this year is about 190,600, down from 196,238 in 2019–2020 and 206,061 in 2018–2019. These figures include the Syrian students enrolled in specially designated “second shift” afternoon classes for non-Lebanese students, as well as a smaller number of Syrian children who attend regular morning classes with the Lebanese students. Syrian children seeking to attend regular classes must wait until after Lebanese children are enrolled for unfilled places (Human Rights Watch, Citation2021). Therefore, the majority of Syrian students attend second-shift classes at public schools. While the number of Syrian children enrolled in second shift classes has slightly declined—148,912 in 2019–20, compared with 153,286 in 2018–19—the number of those enrolled in the “morning shift” alongside Lebanese students has notably decreased from 52,775 in 2018–19 to 40,600 in 2019–20 (”INEE,” Citation2020).

Approximately 40,000 Syrian students in Lebanon have attended non-formal education programs (e.g., basic numeracy, and literacy classes using the national curriculum) run by humanitarian and NGO groups, but in prior years the Lebanese Education Ministry restricted children from transitioning to formal education unless it had certified their non-formal program (Human Rights Watch, Citation2021).

To conclude, since the beginning of the Syrian crisis in 2011, the influx of Syrian refugees into Lebanon has created an education crisis, placing a heavy demand on the public education sector (Culbertson & Constant, Citation2015). In Lebanon, a country where the public education system has historically been fragile and under-funded (Nahas, Citation2011), the integration of refugee children into public schools has struggled to develop at the same speed. In addition, Syrian children faced several barriers standing in the way of public school enrollment, such as the lack of financial support and resources, lack of spaces in public schools, barriers to school registration, and difficulties transitioning to the Lebanese curriculum and language (e.g., the Lebanese system includes English and French as languages of instruction for mathematics and sciences subjects; International Labor Organization (ILO), Citation2011; Shuayb et al., Citation2021). These factors resulted in a lost generation of potentially gifted (or less gifted) Syrian refugee children and youth and the loss of an opportunity to recognize and nurturing for their high abilities.

4.2. Palestinian Refugee Students in Lebanon

Education is highly valued among Palestinian families across the State of Palestine, and countries of refuge (UNICEF, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). The literacy rate is among the highest in the world (UNESCO), and Palestinian women are among the most educated in the Middle East (Cardwell, Citation2018).

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) in Lebanon, in contrast to UNRWA’s other field offices in Palestine and the Arab region, provides not only basic education to Palestinian refugee students, but also secondary education and, to a lesser extent, support access to university education through specific donor funding. In the 2019–2020 academic year, 36,201 students (52.6% of whom are females) were enrolled in 65 schools, including nine secondary schools. Despite high enrollment rates at the elementary level (97%), there are still many challenges for Palestine refugees in completing education in Lebanon, for example, (a) 16% of the Palestine refugee population of intermediate (12–14 years old), and 39% of secondary students (above 15 years) were not enrolled in school (Chaaban et al., Citation2016); (b) 10% of the population aged over 15 years have never attended school at all; and (c) only 58% of 6–18-year-old Palestinian refugee children from Syria fled to Lebanon were enrolled in UNRWA schools in 2014 (Beydoun et al., Citation2021).

Unlike other areas in the Arab region and Palestine, the education of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon encounters exceptional challenges due to several legal reasons. The Lebanese government, for example, has given the Palestinian refugees the legal status of foreigners, which resulted that them being denied major civil rights including access to employment and access to public social services. Since 1948, for example, the Lebanese labor law has prohibited Palestinian refugees from practicing 72 trades and professions. In 2010, Lebanon’s parliament amended its labor law, however, the reform did not remove restrictions that prohibit Palestinians from practicing at least 25 professions requiring syndicate membership, including law, medicine, and engineering (Al-Hroub, Citation2014, Citation2015; Human Rights Watch, Citation2011). The impact of the Lebanese labor law was adverse on the education and employment of Palestinian refugees. This left the majority of registered refugee students dependent on the UNRWA and other NGOs educational services and scholarships (Al-Hroub, Citation2014). In 2021, and due to the economic depression that caused a brain drain in the country, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon were granted limited access to the job market, and to work in skilled professions requiring syndicate membership from which they had previously been barred (Mahfouz & Sewell, Citation2021).

In regards to serving and nurturing gifted refugees in Lebanon, few initiatives have been done by international organizations (El Khoury & Al-Hroub, Citation2018a). Yet, some successful initiatives were implemented by local NGOs. For example, the Action for Hope Association runs a music school that has identified and nurtured the musical talents of refugee children and youth in Lebanon. In 2016 and 2017, the association graduated 24 Palestine and Syria refugees as singers or musicians (El Deeb, Citation2017). From 2016 to 2020, music school students and graduates in Lebanon and Jordan gave around 100 live and online concerts that were attended by over 20,000 people (Action for Hope, Citation2022).

5. Higher education system in Lebanon

Lebanon is known for its large number of private higher education institutions. Lebanon’s private universities, the oldest in the Arab region, date back to the 19th century when the American University of Beirut (AUB) was founded in 1866 and the University of Saint Joseph (USJ) was founded in 1875. Lebanon’s higher education system’s freedom and independence are protected by the constitution. The system operates under the supervision of the Directorate-General for Higher Education, which is responsible for licensing and validating the degrees and disciplines offered by the institutions. According to the statistics report from the CERD (Citation2020), there have been 49 universities operating in Lebanon in the academic year 2019–2020. Among these universities, there is one public university, the Lebanese University (LU), which was founded in 1951. Most universities were legalized in the 1990s when the education system in the country rapidly expanded following 15 years of civil war over the period 1975 to 1990. The number of public and private university students for the 2019–2020 school year in Lebanon reached 222,064 with 142,739 (64.3%) of all students attending private universities and 79,325 (35.7%) enrolled in the Lebanese University (CERD, Citation2020).

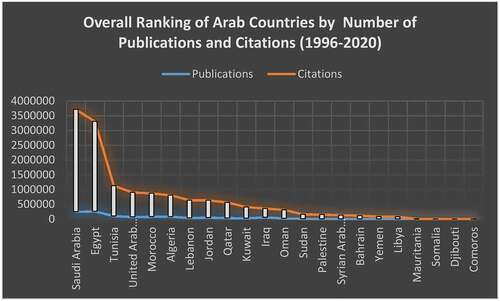

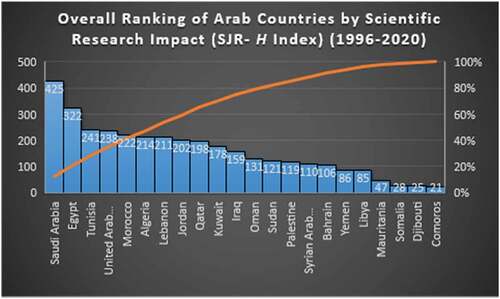

The Lebanese society highly values education and scientific research as evident in a large number of universities (CERD, Citation2018), and the high number of research publications (SRJ, Citation2021). For example, according to the SCImago journal and country rank (SRJ, Citation2021), the research SCOPUS index shows that Lebanese higher education institutions had 41,437 publications with 599,190 citations between 1996 and 2020. Lebanon is ranked 7th among 22 Arab countries in the number of publications and cited publications (See, Figure ). Lebanon is also ranked 4th among 22 Arab countries and 69th among 240 countries in the scientific research impact classification (H Index = 231). It produces a high number of qualified people in almost all professions (See, Figure ). According to the WCGTC (Citation2020), Lebanon has witnessed growth in research conducted in the field of giftedness in the past 10 years, especially by university scholars and graduate students.

Figure 2. Overall Ranking of Arab Countries by Number of Publications and Citations (1996–2020)Note: Metrics based on Scopus® data as of April 2021

Figure 3. Overall Ranking of Arab Countries by Scientific Research Impact (1996–2020)Note: Metrics based on Scopus® data as of April 2021

In regards to academic activities, several private universities (e.g., American University of Beirut, Lebanese American University) introduced academic programs (e.g., diplomas) to prepare teachers, practitioners, and researchers to serve gifted and talented learners in Lebanon (Al-Hroub & El Khoury, Citation2018a). In addition, AUB, Balamand, and the University of Sciences and Arts in Lebanon–(USAL) have offered Lebanese schools and the education community several professional training programs, forums, and conferences (WCGTC, Citation2019, Citation2020)

6. Implications of educational and learning capitals on gifted education

Al-Hroub (Citation2016) identified seven main challenges to gifted and talented education in Lebanon: (a) MEHE has no formal educational policy for gifted education in Lebanon, (b) there is a lack of understanding of the concept of giftedness in Lebanese schools and higher education institutions, (c) there is a lack of valid and reliable diagnostic tools in Arabic for the identification of gifted children, (d) several groups of gifted children are neglected and marginalized, such as twice-exceptional children, (e) there is a lack of pre-service and in-service academic and professional programs on gifted education in Lebanese universities, (f) there are lack of services and facilities for gifted children; and (g) most Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) are interested in sponsoring special education projects with little, if any, on gifted learners (Al-Hroub & El Khoury, Citation2018a; Al-Hroub et al., Citation2020). To scientifically understand and analyze the challenges, and complexity of the development and learning of gifted learners in Lebanon, we explore below the ten educational and learning capitals in relation to the Systems Theory and Actiotope Model of Giftedness. The educational capitals consist of economic, infrastructural, cultural, social, and didactic capitals, whereas, the learning capitals are comprised of organismic, actional, telic, attentional, and episodical capitals (Ziegler & Baker, Citation2013; Ziegler et al., Citation2017, Citation2019).

7. Educational capitals

7.1. Economic educational capital

Ziegler and Baker (Citation2013) referred to economic educational capital as “every kind of wealth, possession, money, or valuables that can be invested in the initiation and maintenance of educational and learning processes” (p. 27), such as expenditures that are invested in gifted education. Lebanon’s education public sector is marginally subsidized by government budgets. Total government expenditure on the public education sector is roughly US$1.2 billion annually (approximately 2.45% of GDP and 6.4% of total public expenditure; Abdul-Hamid et al., Citation2017). In contrast, private spending on education is high and households bear a higher financial burden for education than the government. More than two-thirds of the enrolled student population attend private schools. With a market size of about US$1.3 billion in tuition fees alone, the private sector consumes a large portion of household expenditures (Abdul-Hamid et al., Citation2017).

The Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE) in Lebanon does not offer any financial or human support to gifted education in public schools. The budget allocated for services is only dependent on the private school’s system and philosophy of education (Sarouphim, Citation2010). Yet, it is rarely seen in Lebanon to have private schools that offer specialized programs for gifted education for students eligible, this includes private and public schools and universities (El-Khoury & Al-Hroub, 2018). Private schools are known for offering summer programs and camps to students. Most of these programs focus on nurturing students’ talents, and their social, and leadership abilities (e.g., https://www.edarabia.com/best-summer-camps-lebanon/). Some summer programs focus on supporting human rights through literacy, such as Kitabi (which means in Arabic “my book”كتابي) summer program (Wafa & Shrestha, Citation2020).

Several organizations support access to university education for young scholars who excel academically but would otherwise be unable to afford university tuition fees. Such organizations (e.g., MasterCard Foundation Scholarship Program, USAID Program, UNRWA Scholarship Program, and Unite Lebanon Youth Project) have supported thousands of Lebanese, refugees, and displaced people living in Lebanon (e.g., Palestine and Syria refugees), and African students to complete their education at Lebanese Universities (American University of Beirut (AUB), Citation2022; LAU, Citation2022; ULYP, Citation2020).

7.2. Infrastructural educational capital

Ziegler and Baker (Citation2013) stated that infrastructural educational capital “relates to materially implemented possibilities for action that permit learning and education to take place” (p. 28), such as special schools, special centers, online learning resources, libraries, and universities. Lebanon lacks the public infrastructure that gifted students can use in public schools. As stated in the economic educational capital, the private sector consumes a large portion of household expenditures on infrastructure for education, including materials, books, and resources. Yet, there is a lack of resources, supporting centers, and university programs for gifted education, apart from some private universities, such as AUB and LAU, which provided books and resources to teach courses on identifying and nurturing gifted learners.

In addition, QITABI 2 summer program provides book support to hundreds of children in Lebanon. The program reaches more than 338,000 students from 1,307 schools in Lebanon, including students registered in a 320-afternoon shift that serves Syrian students (Wafa & Shrestha, Citation2020). We are not sure about the percentage of gifted readers within this population; however, such initiatives are crucial for economically disadvantaged students with high potential who are enrolled in public schools.

To conclude, a lot should be done at the public schooling and higher education levels to promote gifted education, prepare qualified teachers, and raise awareness among parents and the education community. Lebanon could benefit from the diaspora to support the provision of aid for a sustainable education for gifted learners. Lebanon is known to be far trumped by its diaspora, which is thought to top 16 million (including multiple generations). Hence, its magnitude, strengths, impact on the country’s economy, and the education of the gifted are substantial (Nasrallah, Citation2020).

7.3. Cultural educational capital

Ziegler and Baker (Citation2013) explained that cultural-educational capital “includes value system, thinking patterns, models and the like, which can facilitate—or hinder—the attainment of learning and educational goals” (p. 27). In this regard, we discussed “What beliefs do Lebanese people have about gifted learners? What is the primary conception of giftedness according to Lebanese teachers? What talents are valued?

Lebanon is one of the cultural hot spots of the Middle East, where music, literature, theatre, and dance all play a vital role in the Lebanese and Arab life (Agenda Culture, Citation2016). In education, highly gifted individuals are highly valued by the society in Lebanon as evident by a large number of educational higher institutions (CERD, Citation2020). Lebanon became “the classroom of the Middle East” for several decades (Vlaardingerbroek et al., Citation2017) as it hosts one of the oldest universities in the Middle East (e.g., AUB, USJ). However, the education of the gifted is overlooked at schools due to conceptual and practical reasons. Some reasons are related to the difficulty in defining the construct of giftedness (Al-Hroub & El Khoury, Citation2018a; Sarouphim, Citation2010). This implies that the identifications of gifted individuals are dependent on cultural views and perceptions of giftedness (Al-Hroub, Citation1999,Citation2012, Citation2013; Antoun et al., Citation2020). Recent studies explored the cultural conception of giftedness in Lebanon. Al-Hroub and El Khoury (Citation2018b) explored the conceptions of 140 Lebanese primary teachers in Greater Beirut through surveys, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions. The findings were analyzed, and synthesized to construct a cultural de facto research-based conception of giftedness in Lebanon, as follows:

Giftedness is a combination of three elements: high intellectual ability, high academic performance, and social intelligence. High intellectual ability includes exceptional ability to think logically, thus the gifted student’s scores on the report cards should be the highest in the class. High academic performance means that gifted students excel in one or more subject areas. Giftedness also encompasses social intelligence, which means that the student should be a natural leader, be capable of taking charge of small groups, and be able to deal creatively and shrewdly with real-life situations, particularly those that are specifically valued in Lebanese culture (pp. 102–103).

This consolidated Lebanese definition has much in common with some aspects of Renzulli’s three-ring model, and Sternberg’s WISC model. In regards to the characteristics of gifted students in Lebanon, El-Khoury and Al-Hroub’s study (2018) reported that Lebanese society encourages the child to be “better than others” or to be “the best in the class”. Al-Hroub and El-Khoury (2018) explained that the Lebanese society advocates certain behaviors, such as “shatara” شطارة in Arabic, or “out-smarting”, which means having the skill to manipulate a person or a thing (such as bargaining for a better price or cutting inline) to obtain the desired results, usually while putting little effort into the endeavor. This is a combined indicator of socio-cultural intelligence and creativity. Likewise, Antoun et al. (Citation2020) explored the perceptions of 281 primary school teachers across three governorates of Lebanon concerning gifted/highly able students. The findings indicated that the eight top-rated characteristics emphasized by Lebanese teachers were associated with intellectual ability, high academic achievement, and creativity (e.g., “able to learn with amazing speed,” “intellectually curious,”, “possessing an exceptional reasoning ability”, “divergent thinker”, “inquirer”, “possess an exceptional memory”, “creative”, “a critical thinker”). Other characteristics mentioned by the Lebanese teachers combined social intelligence and leadership abilities.

In regards to gifted physical appearance, research done by El Khoury and Al-Hroub (Citation2018b) also revealed that while the Lebanese society highly values physical fitness, attractiveness, and immaculate dressing, several teachers link them to wittiness and cleverness. El Khoury and Al-Hroub (Citation2018b) reported differences in Lebanese teachers’ opinions of what a gifted student is expected to “look like”. Some teachers referred to gifted students as those who appear to be “neat”, “tidy”, “clear”, “organized”, ‘healthy, and “perfect dressers”. In contrast, some teachers referred to gifted students as those who are “disorganized”, “not stylish”, and “dress messily” and have the “tendency of wearing mismatching clothes”.

Limited research explored the Lebanese parents’ views about gifted learners. In a qualitative study done by Saade (Citation2017), for example, the findings revealed that high academic achievement, high abilities in math or science, speed processing, and remarkable memory were the top three characteristics noticed by Lebanese parents (Saade, Citation2017). The findings of such research suggest that Lebanese teachers have developed a broader conception of giftedness (e.g., Al-Hroub & El Khoury, Citation2018b; Antoun et al., Citation2020) as compared to Lebanese parents (Saade, Citation2017).

Over the past decade, thousands of local and refugee students have received university from several donors and organizations (e.g., MasterCard Foundation Scholarship Program, USAID Program, UNRWA Scholarship Program, and Unite Lebanon Youth Project). Scholarships were awarded for study in a wide-ranging field across the sciences, social sciences, liberal arts, engineering, and medicine (American University of Beirut (AUB), Citation2022; LAU, Citation2022; ULYP, Citation2020). Refugees have particularly benefited from these scholarships to pursue their education due to a large number of graduate refugee students, and due to current economic depression that caused a brain drain in the country, a new ministerial decree has granted Palestinian refugees limited access to the job market, and to work in skilled professions (Mahfouz & Sewell, Citation2021).

7.4. Social educational capital

Ziegler and Baker (Citation2013) referred to social educational capital as “all persons and social institutions that can directly or indirectly contribute to the success of learning and educational processes” (p. 28), such as teachers, parents, supporting spouses, mentors or advocacy organizations. In the Lebanese context, the educational system in public schools does not promote legislative advocacy bodies like parents’ associations that could contribute to decisions related to gifted education. Despite these advocacy challenges and the lack of formal policies, Al-Hroub (Citation2016) identified three main future opportunities for promoting gifted education in Lebanon. First, is the growing number of research studies on issues related to identifying and serving gifted learners. Second is the increasing collaboration with international/regional organizations concerned with gifted education (e.g., the World Council for Gifted and Talented Children [WCGTC], the International Center for Excellence and Innovation [ICIE], the Arab Council for the Gifted and Talented [ACGT]). Several scholars from Lebanon serve as delegates or members of the executive committees of those organizations. Finally, some private universities have already started to introduce new diploma programs or courses that focus on the education and nurturing of the gifted. Currently, more than four private universities offer either diploma programs (e.g., AUB, LAU) or courses at undergraduate and graduate levels on gifted education (e.g., Notre Dame University–Louaize, University of Sciences and Arts in Lebanon–USAL; Al-Hroub & El Khoury, Citation2018a). In addition, several universities organized conferences, symposiums, or in-service training programs on gifted education (e.g., AUB, USAL, Balamand, and Lebanese University). Finally, in the past decade, several initiatives were launched to promote gifted learners, such as establishing local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for promoting the education of gifted children (i.e., The Lebanese Organization for Giftedness, Innovation, and Creativity, and the Ghadi center). (WCGTC, Citation2020). Still, there is a lack of staff, mentors, and qualified teachers to deal with the academic and socio-emotional challenges of gifted learners in Lebanese schools.

The social exclusion and unjustified living conditions of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon have been well-documented over the past decades (Kherfi et al., Citation2018). However, education among Palestinian refugees is highly valued despite the economical and legal challenges in Lebanon. In the past decade, for example, around 50% of Palestinian high school students in Lebanon entered private universities, while the remaining number varies between UNRWA Siblin Vocational Training Center or other private institutes or public universities. The Palestinian student in Lebanon is obliged to remain distinguished to obtain certain discounts or grants from the university or even to apply to some donors to obtain financial aid. Therefore, most Palestinian students in Lebanon have high university rates between very good and excellent (Shehabi, Citation2021).

7.5. Didactic educational capital

Ziegler and Baker (Citation2013) defined didactic educational capital as “the assembled know-how involved in the design and improvement of educational and learning processes” (p. 29), such as special curricula, teacher training programs, professional expertise of teachers, educational placement (e.g., mainstream versus special schools, regular class versus special classes).

Schools in Lebanon, whether public or private, must follow a national curriculum mandated by MEHE. Catering for learners with special educational needs was also made mandatory in this curriculum (National Center for Educational Research and Development (NCERD), Citation1995), but no special curricula are developed by MEHE for students with special needs or special gifts. In effect, there is almost no reference to the education of gifted students. The only MEHE reference for gifted students is the mention of a grade-based acceleration model, where highly gifted students can skip one grade level in cycle one (grades 1–3) and another in cycle two (grades 4–6; Chaar, Citation2016).

There is a rise in research about gifted education in Lebanon in the last 10 years (El Khoury & Al-Hroub, Citation2018a) and the Arab World (Al-Hroub, Citation2010, Citation2011). However, little has been done on exploring the impact of inclusive education on gifted students in Lebanon, although education policies have shifted in the past two decades towards inclusive education. The Lebanese Public Law 2000/220 was issued aiming to promote the implementation of inclusive education by schools, however, only a few private schools responded (Human Rights Watch, Citation2018). Recently, Jouni (Citation2020) explored the impact of inclusive education on the performance of three groups of students (gifted, regular, with learning disabilities -LDs) in Lebanon. The results showed that gifted students are best served by inclusion from students’ perspectives compared to regular and students with LD. Another study by Antoun (Citation2022) reported findings from a mixed-method study investigating the perceptions of 280 Lebanese teachers about educational approaches used to teach gifted primary school students in Lebanon. Findings indicated reservations among teachers about offering special services for those considered to be gifted within the regular classroom, particularly with ability grouping and acceleration options. Teachers explained that gifted students in regular classrooms might positively impact the academic performance of non-gifted students; they inspire and motivate them to work harder and perform better. Yet, the school environment in Lebanon encourages competition among students in many aspects. Thus, competition between gifted learners may undermine non-gifted students and lead to negative consequences (Antoun).

At the higher education level, and over the past decade, two private universities in Lebanon (American University of Beirut [AUB], and Lebanese American University [LAU]) offered a diploma program that focuses on special education with two tracks: learning disabilities, and giftedness. However, the track of giftedness at AUB has been on hold for a significant period. This makes it difficult to prepare students, who are interested in this field, on how to deal with gifted individuals. Consequently, this feeds back to the educational system that is neglecting gifted individuals in Lebanon.

From that, we conclude that there is no sufficient literacy about gifted education in Lebanon, neither at the school nor higher education level. In addition, most of these programs are relatively new, so it will take some time for preparing Lebanese teachers to identify gifted students and consequently offer the appropriate services and provisions.

8. Learning capitals

8.1. Organismic learning capital

Ziegler and Baker (Citation2013) referred to organismic learning capital as that “consists of the physiological and constitutional resources of a person” (p. 29), such as healthy bodies, and physical attractiveness and fitness for gifted individuals.

“A sound mind in a sound body” is a famous quotation by the pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Thales, demonstrating the close connection between physical fitness, mental strength, and the ability to socialize and communicate with others. It also suggests people are only healthy when they are occupied both intellectually and physically. However, this motto was extracted from its context as the original statement, written by the poet Jovenal, says, “A man should pray for a healthy mind in a healthy body”. Meta-analytic studies showed positive effects of physical exercise training on cognition, brain functioning, and academic performance in children, and young and older adults (Hillman et al., Citation2008). El Khoury and Al-Hroub (Citation2018b) reported that many teachers referred to physical ability and fitness as an area of giftedness, however, the emphasis at schools remained on academic, intellectual, and then social and creative abilities in their cultural understanding of giftedness.

Team sports, such as football, basketball, and volleyball, are very popular in schools in Lebanon (Gall & Hobby, Citation2009). Although football is the most popular sport, Lebanon has shown regional and international success in basketball. It was estimated that the first-time basketball was ever played in Lebanon was in the mid-1920s at the American University of Beirut. Later, the Lebanon national basketball team qualified three consecutive times for the Fédération Internationale de Basketball (FIBA) World Championship in 2002, 2006, and 2010 (FIBA, Citation2019), and won the Arab Men’s Basketball Championship in 2022 (Moussa, Citation2022). Lebanese Sports clubs have also won the Arab Club Championship eight times, the FIBA Asia championship in 1999, 2000, and 2004, and the West Asian Basketball Association (WABA) Championship Cup in 2002, 2004, and 2005 (FIBA, Citation2019), and received the 1999 Best professional basket team in Asia (Addiyar, Citation1999).

Hiking, trekking, and mountain biking are also popular sports in the summer (Gall & Hobby, Citation2009). The Beirut International Marathon (BIM) has become an annual, international event since 2003. It is held every fall, drawing top runners from school-aged and university students to seniors from Lebanon, and the region. In addition, the Rally of Lebanon, the first rally being run in the Middle East, has been a popular sport in Lebanon since 1968 (Rally Of Lebanon, Citation2021).

Regarding diets and healthy eating at schools, research in Lebanon revealed that amongst a nationally representative sample, 34 · 8 % of children and adolescents aged 6–19 years were overweight and 13 · 2 % were obese. Such obesity was also found in Italy, Greece, and Cyprus due to the lack of adherence to the Mediterranean diet (Plant-based foods, such as whole grains, vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, seeds, herbs, and spices; Nasreddine et al., Citation2014). Several initiatives and studies were conducted to promote healthy eating and physical activity among school children in Lebanon by using the Social Cognitive Theory (e.g., Habib-Mourad et al., Citation2014), or adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MD) a model of a healthy diet and healthy lifestyle (Mitri et al., Citation2021).

In regards to psychological support, one of the critically neglected problems among refugees in Lebanon is mental illness. Yes, most mental health and psychosocial support services for Syrian and Palestinian refugees are provided by local and international NGOs to supplement the existing nutrition services (Kerbage et al., Citation2020). Some initiatives and studies in Lebanon examined the positive impact of school-based nutrition intervention programs on improving the nutrition quality, and physical activity among Syria (Harake et al., Citation2018), and Palestine refugees (Ghattas et al., Citation2020; Kishk et al., Citation2019).

8.2. Actional learning capital

Ziegler and Baker (Citation2013) defined actional learning capital as “the action repertoire of a person—the totality of actions they are capable of performing” (p. 30), such as abilities to swim, dance, and play a musical instrument, or perform mathematical operations. In this regard, we addressed issues, such as, “how successful is gifted education in Lebanon? How do Lebanon’s best students perform in international educational studies (PISA, TIMSS, etc.)? Have they received awards or prizes for their participation in international competitions?

Lebanon lacks a formal system of education for gifted students. The emphasis in the national school curriculum remains on mainstream education. Some private schools provide services for academically and non-academically gifted students (e.g., clubs for gifted in drama, Engineering, Art Effect, Designing Computer Games, and Robotics). However, these services and clubs are often limited in content and scope (Al-Hroub, Citation2018b; Sarouphim, Citation2009). In Feb 2022, the Lebanese parliament approved a proposed law to amend pre-university public education. The approved proposal aims to expand the teaching of informatics in the Lebanese curriculum to include robotics and artificial intelligence in all levels of middle and secondary education, with one period each week (Ibrahim, Citation2022).

At the national and regional levels, several Lebanese universities and societies (e.g., the Lebanese Society for Mathematical Sciences) hold annual competitions and awards for gifted students. The Department of Education/Science and Math Education Center at the American University of Beirut, for another example, organize annual project competitions for young and youth children at schools in Lebanon and the Arab region, known as the annual science, math, and technology fair. This competition served thousands of highly able students from Lebanon and the Arab region over the past four decades. In this annual fair, K-12 students prepare and present projects and compete for awards in a variety of categories. The fair encourages students to engage with topics in science, mathematics, and technology in an independent, active, and critical way. Each year, 25–30 schools from all over Lebanon and beyond participate in the fair (American University of Beirut (AUB), Citation2016). Also, Lebanese universities in collaboration with MEHE and other Lebanese governates organize the VEX Robotics Competition, which is one of the largest competitions in Lebanon (VEC, 2020). As for the writing contest, students at the American University of Beirut are encouraged to participate in the Founders Day Student Essay Contest. In this event, students are asked to share their pieces of high-quality writing papers, corresponding to a certain theme that is specified by the university. This event is considered an opportunity for university students to demonstrate their high abilities in writing (American University of Beirut (AUB), Citation2016).

At the international level, Lebanese universities and schools participate in several international Olympiads and competitions for gifted students. An increasing number of Lebanese students received medals and awards from numerous organizations, such as the International Astronomy and Astrophysics Competition (IAAC; Yassine, Citation2021), International Youth Math Challenge 2020 (LU, Citation2020), International Competition on Mental Calculation, and the Global Robotics Competition (Balingit & Hassan, Citation2017). Despite this, studies have shown that students in Lebanon score below the international averages in international assessments such as PISA (the Program for International Student Assessment), and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) in mathematics, sciences, and reading. In PISA results, 1% of students in Lebanon were top performers in reading (OECD average: 9%), 2% in mathematics (OECD average: 11%), and 1% in sciences (OECD average: 7%; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) & Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Citation2018).

Both PISA and TIMSS classify students based on their socioeconomic capital as advantaged, and disadvantaged learners (Kelly et al., Citation2020; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) & Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Citation2018). People or refugees living in Syrian or Palestinian refugee camps are also considered people with low socioeconomic capital. It is worth noting that advantaged students in Lebanon score significantly higher than disadvantaged students, yet they both score lower than the international averages. For example, the latest TIMSS 2019 and PISA Citation2018 learning results showed there is a remarkable gap in learning outcomes between students from different types of schools (private versus public) in all subjects. For example, the average difference between advantaged and disadvantaged students in reading is 103 points, compared to an average of 89 in OECD countries. According to principals’ reports, learning outcomes in Lebanese public schools are impacted by poor infrastructure, shortages in educational materials, and a lack of qualified teachers. Also, public schools are often reported as less prepared to teach using technology (Kelly et al., Citation2020; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) & Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Citation2018).

In contrast, Lebanon did not participate in the WorldSkills Competitions (formerly known as the International Vocation Training Organisation), which organizes the world championships of vocational skills since the 1940s. This demonstrates the deficiency of talent support in the vocational sector in Lebanon although several Lebanese members participated in some projects presented by other countries, such as the United Arab Emirates (WorldSkills, Citation2017).

Several success stories were reported about gifted refugee students in Lebanon. For example, Aya Yousef, a Palestinian refugee, was recognized by the 2021 Chegg Global Student Prize as one of the most influential students in the world (Patten, Citation2021). In addition, Iqbal-Al-Assaad, another Palestinian refugee, became possibly the youngest Arab medical doctor (and one of the world’s youngest medical doctors). She attended the Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar (WCMC-Q) at the age of 14 years old (Yahia, Citation2013). Similar stories were reported about Syrian refugees. For example, a group of Syrian refugee women in Lebanon founded a local NGO called “Basmeh and Zeitooneh”. Their organization won the Caritas Internationalis and Voices of Faith international prize for supporting Shatila camp Syrian and Palestinian refugees to learn embroidery, computers, and the English language (ReliefWeb, Citation2015).

8.3. Telic learning capital

Ziegler and Baker (Citation2013) explained that the “telic learning capital comprises the totality of a person’s anticipated goal states that offer possibilities for satisfying their needs” (p. 30), such as the passion for a specific domain, functional goal setting, and learning goal orientation.

The Lebanese society is metalinguistic and multicultural and highly values education. However, most of the highly qualified people migrate to Gulf countries, Europe and North America due to the lack of job opportunities and the ongoing economic and political problems. Vlaardingerbroek et al. (Citation2017) explained,

Sometimes referred to as “the classroom of the Middle East”, Lebanon has no shortage of educational institutions or opportunities and produces high numbers of well-qualified people. But there is a very poor match between graduate output and the needs of the economy, exacerbating educated unemployment and creating much underemployment. These factors, coupled with mediocre domestic salaries, contribute strongly to the on-going Lebanese diaspora that sees much high-level Lebanese human capital emigrating (pp. 255–256).

The literacy rate among Palestinians, in general, is known as among the highest in the world (UNESCO). However, the legal challenges in Lebanon forced hundreds of thousands of them to migrate to Europe, North America, and Gulf Arab countries. Similar to Lebanese, most Palestinian refugees in Lebanon rely heavily on their diaspora to support the education of their children (ICMPD, Citation2019). Despite the economic and legal challenges, the Palestinian labor force, in general, shares similar characteristics with the Lebanese in terms of activity rate, sector, employment status, occupation, and industry (International Labor Organization (ILO), Citation2011).

8.4. Attentional learning capital

According to Ziegler and Baker (Citation2013), attentional learning capital “denotes the quantitative and qualitative attentional resources that a person can apply to learning” (p. 31), such as time available for learning, and volitional strategies to focus attention on learning. There is no sufficient information or research findings on the attentional learning capital in Lebanon (e.g., time and attention spent by the gifted to develop their potential, time spent on each talent … etc.). However, Lebanese students, mostly in private schools, suffer from finding leisure time due to the overemphasis on the academic curricula, and the increase of the homework load given to students, especially at the secondary school level. This leaves many students with high potential unable to hone their skills and talents.

8.5. Episodical learning capital

Ziegler and Baker (Citation2013) stated that episodical learning capital is concerned with “the simultaneous goal- and situation-relevant action patterns that are accessible to a person” (p. 31). In this regard, we explored the learning experiences and styles, characteristics, and attributes of gifted learners as viewed by school teachers and parents in Lebanon.

Lebanon is the place for international and Arab famous people: fashion designers (e.g., Elie Saab), writers and poets (e.g., Amin Malouf, Khalil Gibran, Ameen Rihani), singers (e.g., Fairuz, Sabah), musicians (e.g., Ziad Rahbani, Elias Rabani, Rahbani brothers), film directors (e.g., Nadine Labaki) and many others. Lebanese diaspora has produced several international celebrities that Lebanese like to claim as their own, such as Shakira (Colombian singer, songwriter, and dancer has Lebanese paternal grandparents), Salma Hayek (the Mexican-American actress, producer, and former model who has Lebanese paternal grandparents), the chairman and Carlos Ghosn (former CEO of Nissan and Renault), Ralph Nader (American politician, activist, and lawyer who previously ran for president of the United States. He was raised by Lebanese immigrant parents; Mousa, Citation2016). In addition to a number of Nobel and international awards that Lebanese also like to claim as their own, such as Ardem Patapoutian (An American scientist of Armenian-Lebanese roots, and the recipient of the 2021 Nobel Prize for Medicine), Peter Brian Medawar (a British-Lebanese, and the recipient of Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology in 1960), and Michael Atiyah (British-Lebanese mathematician and recipient of Fields Medal and Abel Prize; EL-Tohamy, Citation2021; Ghaleb, Citation2020; Shawki, Citation2016).

In regards to school practices, each country has its practices for the education of gifted and non-gifted learners. Thus, what might be an attribute of giftedness in Lebanon is not necessarily the same attribute that is relevant in another country. El Khoury and Al-Hroub’s (Citation2018b) showed that most Lebanese teachers portray gifted students as those who are “thirst for knowledge”, “complete their assignments faster than same-age peers”, “learn easily and quickly”, “knowledgeable”, “perfectionists”, “energetic”, “find it difficult to remain in-seat”, “followers”, “have poorer social skills”, and “shy”. Some Lebanese teachers referred to them as “not stylish, looks weird”, “witted (which refers to being funny and clever)”, “sharp”, and “have twinkle or sparkle in their eyes (which refers to high intellectual ability)”. However, Lebanese teachers reported some contradictory attributes, such as being “disorganized” versus “organized”, and “calm and well-mannered” versus “messy and self-conceited”, which makes it difficult for schools to identify them based on such disputed attributes. In addition, several teachers identified gifted students as those who were “good at bargaining” and “knew all about Lebanese politics, religion, and history”. Perhaps this is particularly relevant to the Lebanese culture that tends to view shatara شطارة (“out-smarting others”) as a “very intelligent move”. One of the major findings is how gender plays a role in recognizing giftedness. Two-thirds of the teachers believe that gifted boys outnumber gifted girls in Lebanese schools. Moreover, Lebanese society and Lebanese school practices perceive boys to be far more likely to be gifted than girls.

Another major misconception in the minds of some Lebanese teachers was what we call the “doctor and engineer” syndrome, which is a socially constructed idea influenced by the Lebanese culture. Many teachers regarded high-status positions, such as that of “doctor”, or logical-mathematical majors such as engineering, to be indicators of giftedness, particularly in males. According to most teachers, boys are more likely to show their giftedness through activities that tap mathematical/logical ability, whereas girls are more likely to show their giftedness through activities that tap verbal abilities.

9. Conclusion and implications

We believe that Lebanon should use the gifts, talents, and highly qualified people that it has, to be able to create more services and opportunities for those people. The Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE) must take the lead to promote gifted learners. Based on the findings and discussion, of the educational and learning capitals, several implications can be drawn concerning the main challenges to gifted education in Lebanon. The first challenge is the absence of a formal educational policy for gifted education hinders the plans, and initiatives, made by schools, teachers, and educators to promote gifted education. A second challenge is the absence of a cultural conception of giftedness in Lebanon. A third challenge is the lack of diagnostic tools that are adapted to the Lebanese context for identifying gifted learners in Lebanon. A fourth challenge is the lack of teacher preparation at the university level for identifying and serving children with high abilities. A fifth is the lack of financial resources and expenditures on teaching gifted students, particularly in the public sector as a consequence of the absence of MEHE from taking a leading role in this regard. A sixth challenge is the absence of international funds for sponsoring projects on serving disadvantaged and marginalized gifted children.

Despite these challenges, Lebanese society is dynamic, multilinguistic, and highly values education. It produces a large number of qualified people in almost all skilled professions in Lebanon (El Khoury & Al-Hroub, Citation2018a). Several implications and recommendations can be drawn for promoting gifted education in the Lebanese society and education community.

First, the Lebanese education authorities, and policy-makers are invited to (a) develop policies for identifying and nurturing gifted learners at schools, (b) adopt nontraditional broad operational Lebanese definitions of giftedness based on empirical findings (e.g., Al-Hroub & El-Khoury), (c) develop effective identification protocol that considers the academic, social and creative domains in students; and (d) engage school staff, and teachers in identifying and nurturing gifted students. Second, the Lebanese government needs to improve equity at schools, especially by providing access and quality education at private schools for economically disadvantaged Lebanese and non-Lebanese gifted students (e.g., forcibly displaced and refugee populations).

Third, Lebanese higher education institutions are invited to pay more attention to serving gifted education at the higher education level by introducing academic and professional teacher training programs to prepare teachers, practitioners, and mentors to deal with issues related to gifted children and gifted education.

Fourth, Lebanon decision-makers are recommended to increase the education budget for the public sector and improve budget execution to ensure that allocated resources are effective, catering to the needs of public schools and their gifted learners. They are also recommended to increase budget allocation to curriculum, learning, and equipment related to identifying and teaching gifted students at Lebanese schools. Fifth, the Lebanese education authorities, in collaboration with international donors, need to address public schools’ resource shortages and allocate human resources including teachers in response to public school level needs and corresponding to standards and goals for gifted education. Sixth, the Lebanese government needs to improve accountability measures for grants provided by the public schools sector and parent committees. This entails introducing a fund accountability system for gifted education, in which schools will access information on funds credited to them and record expenditures.

Seventh, effective nurturing of giftedness in Lebanese and refugee children and adolescents requires a cooperative partnership between home and school. To accomplish this partnership, the Lebanese education ministry, UNRWA, UNHCR, and Lebanese universities need to raise awareness among parents about giftedness, children’s needs, and some basic principles of advocacy. Eight, academic and non-academic competitions play an important part in learning for highly Lebanese and refugee gifted students. Lebanese education authorities, UNRWA, and NGOs are invited to establish local competitions (e.g., robotics, chess, art, mathematics, science and technology, poetry, singing, music, play.etc) for Lebanese, and refugee students to inspire, enlighten, and create enthusiasm and help students to maximize their potentials.

Finally, Lebanon could benefit from engaging the diaspora community and its multi-linguistic highly skilled educators. Lebanese diaspora can contribute financially, educationally, and professionally to serving gifted and skilled learners at educational institutions, and promoting sustainable gifted education in Lebanon.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anies Al-Hroub

Anies Al-Hroub is an Associate Professor of Educational Psychology and Special Education. Al-Hroub has earned his Ph.D. and MPhil in Special Education (Twice-Exceptionality/Gifted with Learning Disabilities) from the University of Cambridge and his M.A. (Special Education) and B.A. (Psychology) from the University of Jordan. He was a Visiting Scholar at the University of Connecticut (2018–19), the University of Cambridge in 2010, and the School of Advanced Social Studies (SASS) in Slovenia. His publications appeared in leading international gifted and special education journals in addition to three published books entitled, “Theories and programs of education for the gifted and talented” (Shorouk, 1999), “ADHD in Lebanese schools: Diagnosis, assessment and treatment” (with H. Berri) [Springer, 2016], and “Giftedness in Lebanese Schools Integrating theory, research, and practice” (with S. El Khoury) [Springer, 2018]. Al-Hroub’s research interests focus on marginalized, vulnerable, and underrepresented populations and gifted populations, such as exceptional, twice-exceptional, and refugee learners.

References

- Abdul-Hamid, H., Sayed, H., Krayem, D., & Ghaleb, J. (2017). Lebanon: Education public expenditure review. World Bank Group. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/30065/127517-REVISED-Public-Expenditure-Review-Lebanon-2017-publish.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Action for Hope. (2022). Music schools. https://www.act4hope.org/2018/03/05/music-schools-2/

- Addiyar. (1999, May). Addiyar archives. https://addiyar.com/article/707446-صفحة-16-3051999

- Agenda Culture. (2016). Culture in Lebanon by 2020: State of play. http://backend.institutdesfinances.gov.lb/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Culture-in-Lebanon-BY-2020-State-of-Play-2016.pdf

- Al-Hroub, A. (1999). Theories and programmes of education for the gifted and talented. Dar Al-Shorouk.

- Al-Hroub, A. (2010). Programming for mathematically gifted children with learning difficulties in Jordan. Roeper Review, 32(4), 259–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2010.508157

- Al-Hroub, A. (2011). Developing assessment profiles for mathematically gifted children with learning difficulties in England. Journal of Education for the Gifted, 34(1), 7–44 doi:10.1177/016235321003400102.

- Al-Hroub, A. (2012). Theoretical issues surrounding the concept of gifted with learning difficulties. International Journal for Research in Education, 31, 30–60. http://www.cedu.uaeu.ac.ae/journal/issue31/ch2_31ar.pdf

- Al-Hroub, A. (2013). A multidimensional model for the identification of dual-exceptional learners. Gifted and Talented International, 28, 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2013.11678403

- Al-Hroub, A. (2014). Perspectives of school dropouts’ dilemma in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon: an ethnographic study. International Journal of Educational Development, 35, 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2013.04.004

- Al-Hroub, A. (2015). Tracking dropout students in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. Educational Research Quarterly, 38 3 , 52–79.

- Al-Hroub, A. (2016). Challenges to gifted and talented education in Lebanon. In Seminar on the status of gifted education in Lebanon: challenges and future opportunities. American University of Beirut.

- Al-Hroub, A., & El Khoury, S. (2018a). Introduction to giftedness in Lebanon. In S. E. Khoury & A. Al-Hroub (Eds.), Gifted education in Lebanese schools: Integrating theory, research, and practice (pp. 1–7). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78592-9_1

- Al-Hroub, A., & El Khoury, S. (2018b). Giftedness in Lebanon: Emerging issues and future considerations. In S. E. Khoury & A. Al-Hroub (Eds.), Gifted education in Lebanese schools: Integrating theory, research, and practice (pp. 95–110). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78592-9_6

- Al-Hroub, A., Saab, C., & Vlaardingerbroek, B. (2020). Addressing the educational needs of street children in Lebanon: A hotchpotch of policy and practice. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(3), 3184–3196. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa091

- Alameddine, M. (2016), The LWIS-city international school-DT model for the education of the gifted and talented. INTED 2016 conference proceedings, Valencia, Spain.

- American University of Beirut (AUB). (2016). Factbook 2015–16. Office of Institutional Research and Assessment (OIRA). American University of Beirut.

- American University of Beirut (AUB) (2022). Scholarships for undergraduate students. https://www.aub.edu.lb/faid/Pages/Scholarships%20Undergraduate.aspx

- Antoun, M., Kronborg, L., & Plunkett, M. (2020). Investigating Lebanese primary school teachers’ perceptions of gifted and highly able students. Gifted and Talented International, 35(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2020.1783398

- Antoun, M., Plunkett, M., & Kronborg, L. (2022). Gifted education in lebanon: Time to rethink teaching the gifted. Roeper Review, 44(2), 94–110. 10.1080/02783193.2022.204350

- Balingit, M., & Hassan, S. (2017, July). At a global robotics competition, teens put aside grown-up conflicts to form unlikely alliances. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/education/wp/2017/07/18/at-a-global-robotics-competition-teens-put-aside-grown-up-conflicts-to-form-unlikely-alliances/

- Berri, H., & Al-Hroub, A. (2016). ADHD in Lebanese schools: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28700-3

- Beydoun, Z., Abdulrahim, S., & Sakr, G. (2021). Integration of Palestinian refugee children from Syria in UNRWA schools in Lebanon. Journal of International Migration & Integration, 22(4), 1207–1219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00793-y

- Cardwell, L. (2018). The state of girls’ education in Palestine. https://borgenproject.org/the-state-of-girls-education-in-palestine/

- CERD. (2018). Statistical bulletin for the academic year 2017-2018. Center for Educational Research and Development, Lebanon.

- CERD. (2020). Statistical bulletin for the academic year 2019–2020. Center for Educational Research and Development.

- Chaaban, J., Salti, N., Ghattas, H., Irani, A., Ismail, T., & Batlouni, L. (2016). Survey on the socioeconomic status of Palestine refugees in Lebanon 2015. UNRWA. https://www.unrwa.org/sites/default/files/content/resources/survey_on_the_economic_status_of_palestine_refugees_in_lebanon_2015.pdf

- Chaar, R. (2016). Educators’ unawareness of the needs of the gifted students and its effect on their learning and productivity in schools of Beirut. M.A. thesis: International Lebanese University.

- Culbertson, S., & Constant, L. (2015). Education of Syrian refugee children: Managing the crisis in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan.. Rand Corporation.

- El Deeb, S. (2017). Syrian children in Lebanon find music school away from home. https://apnews.com/article/1a05ddacf2db4548a0267634714ba6a0

- El Khoury, S., & Al-Hroub, A. (2018a). Gifted education in Lebanese schools: Integrating theory, research, and practice. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78592-9

- El Khoury, S., & Al-Hroub, A. (2018b). Defining and identifying giftedness in Lebanon: Findings from the field. In S. E. Khoury & A. Al-Hroub, Eds. Gifted education in Lebanese schools: Integrating theory, research, and practice. 2018(pp. 73–94). Springer International Publishing:. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78592-9_5.

- EL-Tohamy, A. (2021). Nobel Laureate Ardem Patapoutian’s path to the prize started in beirut. https://www.al-fanarmedia.org/2021/10/ardem-patapoutian/

- FIBA. (2019). FIBA archive. https://archive.fiba.com/pages/eng/fa/p/search.html

- Gall, T., & Hobby, J. (2009). Worldmark encyclopedia of cultures and daily life. Gale.

- Ghaleb (2020). 20+ most successful members of the Lebanese diaspora. Diaspora. https://www.the961.com/successful-members-of-lebanese-diaspora/

- Ghattas, H., Choufani, J., Jamaluddine, Z., Masterson, A. R., & Sahyoun, N. R. (2020). Linking women-led community kitchens to school food programmes: Lessons learned from the healthy Kitchens, healthy children intervention in Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. Public Health Nutrition, 23(5), 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019003161

- Habib, R. (2019). Survey on child labour in agriculture in the Bekaa valley of Lebanon: The case of Syrian refugees. American University of Beirut Press.

- Habib-Mourad, C., Ghandour, L. A., Moore, H. J., Nabhani-Zeidan, M., Adetayo, K., Hwalla, N., & Summerbell, C. (2014). Promoting healthy eating and physical activity among school children: Findings from Health-E-PALS, the first pilot intervention from Lebanon. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-940

- Harake, E., Diab, M., Kharroubi, S., Hamadeh, S. K., & Jomaa, L. (2018). Impact of a pilot school-based nutrition intervention on dietary knowledge, attitudes, behavior and nutritional status of Syrian refugee children in the Bekaa, Lebanon. Lebanon. Nutrients, 10(7), 913. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10070913

- Hillman, C. H., Erickson, K. I., & Kramer, A. F. (2008). Be smart, exercise your heart: Exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 9(1), 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2298

- Human Rights Watch. (2011). World report 2011: Lebanon. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2011/country-chapters/lebanon

- Human Rights Watch. (2018). Lebanon: Schools discriminate against children with disabilities -

- Human Rights Watch (2021). Lebanon: Syrian refugee children blocked from school: Education ministry should remove barriers; extend registration deadline. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/12/03/lebanon-syrian-refugee-children-blocked-school

- Ibrahim, F. (2022). Full results of the February 21, 2022 session. Legal Agenda: Parliamentary Observatory.

- ICMPD. (2019). Migration of Palestinian refugees from Lebanon: Current trends and implications.

- Interagency Coordination. (2020). Lebanon–end-of-year 2020 dashboard. https://data2.unhcr.org/fr/documents/details/86017

- Inter-Agency network for education in emergencies (INEE) (2020). Education in emergencies data snapshot: Lebanon. https://inee.org/system/files/resources/Lebanon%20Crisis%20Snapshot.pdf

- International Labor Organization (ILO). (2011). Labour force survey among Palestinian refugees living in camps and gatherings in Lebanon. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/lfsurvey_en.pdf

- Jouni, N. (2020). The Impact of inclusion on the socio-emotional and academic functioning of the students with and without special educational needs. American University of Beirut.

- Kelly, D. L., Centurino, V. A., Martin, M. O., & Mullis, I. V. (Eds.) (2020). TIMSS 2019 Encyclopedia: Education Policy and Curriculum in Mathematics and Science. Retrieved from TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center website: https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2019/encyclopedia/

- Kerbage, H., Marranconi, F., Chamoun, Y., Brunet, A., Richa, S., & Zaman, S. (2020). Mental health services for Syrian refugees in Lebanon: Perceptions and experiences of professionals and refugees. Qualitative Health Research, 30(6), 849–864. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319895241

- Kherfi, S., Bausch, J., Irani, A., & Al Mokdad, R. (2018). Labour market challenges of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon: A qualitative assessment of employment service centres. International Labor Office.

- Kishk, N. A., Shahin, Y., Mitri, J., Turki, Y., Zeidan, W., & Seita, A. (2019). Model to improve cardiometabolic risk factors in Palestine refugees with diabetes mellitus attending UNRWA health centers. BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care, 7(1), e000624. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2018-000624

- LAU. (2022). USAID higher education scholarship program. https://hes.lau.edu.lb/

- LU. (2020 December). Charbel hayek from the faculty of engineering wins the Lebanon prize in the international youth math challenge 2020. Retrieved. from. http://luwebxx.ul.edu.lb/en/charbel-hayek-faculty-engineering-wins-lebanon-prize-international-youth-math-challenge-2020

- Mahfouz, A., & Sewell, A. (2021, December). Labor minister decrees Palestinians can work in professions requiring syndicate membership. L’Orient Today. https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1284128/labor-minister-decrees-palestinians-can-work-in-professions-requiring-syndicate-membership.html

- Mitri, R. N., Boulos, C., & Ziade, F. (2021). Mediterranean diet adherence amongst adolescents in North Lebanon: The role of skipping meals, meals with the family, physical activity and physical well-being. British Journal of Nutrition, 21, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114521002269

- Mousa, M. (2016). 11 international celebrities with ‘Lebanese’ origins. https://stepfeed.com/11-international-celebrities-with-lebanese-origins-0144

- Moussa, L. S. (2022, February). Lebanese national basketball teams wins Arab Cup for first time in history. Beirut Today. https://beirut-today.com/2022/02/17/lebanese-national-basketball-teams-wins-arab-cup-for-first-time-in-history/

- Nahas, C. (2011). Financing and political economy of higher education: The case of Lebanon. Prospects, 41(1), 69–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-011-9183-9

- Nasrallah, M. (2020, October). The role of the diaspora in healing Lebanon: Hope in the face of relentless calamity. Executive Magazine. https://www.executive-magazine.com/opinion/the-role-of-the-diaspora-in-healing-lebanon

- Nasreddine, L., Naja, F., Akl, C. et al. (2014). Dietary, lifestyle and socio-economic correlates of overweight, obesity and central adiposity in Lebanese children and adolescents. Nutrients, 6(3), 1038–1062. http://doi:10.3390/nu6031038

- National Center for Educational Research and Development (NCERD). (1995). Lebanese national curriculum. Beirut.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) & Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). (2018). PISA 2009 technical report.

- Patten, M. (2021, October). Palestinian refugee named world’s most influential student – middle east monitor. SaveLeb. https://saveleb.org/palestinian-refugee-named-worlds-most-influential-student-middle-east-monitor/

- Rally of Lebanon. (2021). Rally of Lebanon: Middle East rally championship. https://www.rallylebanon.com/

- ReliefWeb. (2015). Syrian refugee women in Lebanon win international prize. https://www.basmeh-zeitooneh.org/

- Saade, F. (2017). A case study of the identification, policies, and practices for gifted students in a Lebanese private school. M.A. Thesis: American University of Beirut.

- Sarouphim, K. M. (2009). The use of a performance assessment for identifying gifted Lebanese students: Is DISCOVER effective? Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 33(2), 275–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235320903300206

- Sarouphim, K. M. (2010). A Model for the education of gifted learners in Lebanon. International Journal of Special Education, 25(1), 71–79.

- Shawki, S. (2016). Meet 9 people from the middle east who won a nobel prize. https://stepfeed.com/meet-9-people-from-the-middle-east-who-won-a-nobel-prize-1048

- Shehabi, M. (2021). Palestinian students in Lebanon: Success and mastery despite suffering. https://www.qudspress.com/index.php?page=show&id=67003

- Shuayb, M., Chatila, S., Maadad, N., Zafer, A., Crul, M., & AboulHoson, A. (2021). Towards an inclusive education: A comparative longitudinal study. Center for Lebanese Studies: American Lebanese University.

- SRJ. (2021). Scimago journal & country rank. https://www.scimagojr.com/countryrank.php?order=h&ord=desc

- ULYP. (2020). ULYP 2019–2020 annual report https://issuu.com/ulyp/docs/ulyp_annual_report_2019-2020

- UNHCR. (2021 September 2021). Lebanon: Fact sheet. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Lebanon%20factsheet%20September%202021.pdf

- UNICEF. (2018a). State of Palestine: Humanitarian situation report. https://www.unicef.org/documents/state-palestine-humanitarian-situation-report-june-2018

- UNICEF. (2018b). Education and adolescents: Working to ensure that all Palestinian children and adolescents grow up in a safe environment and have access to quality basic education. https://www.unicef.org/sop/what-we-do/education-and-adolescents

- VEX robotics competition Lebanon 2020 (VRC). Tournament. https://www.robotevents.com/robot-competitions/vex-robotics-competition/RE-VRC-19-9629.html#general-info

- Vlaardingerbroek, B., Al-Hroub, A., & Saab, C. (2017). The Lebanese educational system: Heavy on career orientation, light on career guidance. In R. Sultana (Ed.), Career education and guidance in the mediterranean region: Challenging transitions in South Europe and the MENA region (pp. 255–265). Sense Publishers.

- Vlaardingerbroek, B., Shehab, S. S., & Alameh, S. K. (2011). Open cheating and invigilator compliance

- Wafa, K. W., & Shrestha, R. (2020). QITABI 2 summer program tackles wide-ranging needs of Lebanon’s schoolchildren. World Learning. https://www.worldlearning.org/country/lb/

- WCGTC. (2019). Newsletter of the world council for gifted and talented children, 38 (1), 1–16.

- WCGTC. (2020). Newsletter of the world council for gifted and talented children, 39 (1), 1–28.

- Worldometer. (2021). Countries in the world by population 2021. https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/population-by-country/

- WorldSkills. (2017). WorldSkills Abu Dhabi 2017: Final report. https://api.worldskills.org/resources/download/8893/9752/10670?l=en