Abstract

The interest in the education of gifted students in Egypt began since 1962, when the first school for the gifted was established. In 2005, a clear decline was observed in the number of students enrolled in the high school science section due to some practical and economic reasons. Consequently, the Egyptian Ministry of Education launched STEM schools for gifted students in math and science in 2011, to support gifted students and provide them with varied opportunities to develop their skills and abilities. Moreover, the Ministry of Higher Education established many specialized centers for gifted students. This study aimed to explore the real situation of gifted education in Egypt, from the learning-resource perspective. The researchers contacted and collated reports from many institutions in Egypt, including the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Higher Education, and the Centers for Gifted students. Moreover, some tools were developed to collect data about the real situation of gifted students in Egypt. Our analysis showed a tangible progress in gifted education; examining the exogenous and endogenous learning resources revealed the strengths and weaknesses of gifted education in Egypt. We recommend the need for more efforts to provide this exceptional student category with proper opportunities.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Egypt has a rich history in investing in Egyptian students’ gifts and talents through a variety of advanced programs and services. The current article discusses the past, the present, and the future of gifted education in Egypt, with the main goal to analyze the status of gifted education in Egypt based on Learning-Resource Perspective. To achieve such a goal, data and reports from the Ministry of Education as well as the Ministry of Higher Education were collected and discussed. Moreover, the authors collected original data to shed light on the status of gifted education in Egypt from five Endogenous Learning Resources (i.e., Organismic, Actional, Telic, Attentional, and Episodic) and five Exogenous Learning Resources (i.e., Economic, Infrastructural, Cultural, Social, and Didactic). The main results indicated that the Egyptian government supports K-12 gifted education programs and such support is also provided by the private sector. Finally, the current article offers some suggestions for the future of gifted education in Egypt.

The systematic study of giftedness and talent in the past 100 years has achieved significant outcomes. One of the most important results is that giftedness is no longer considered a unidimensional construct synonymous with high intelligence or a high intelligence quotient (IQ; Sternberg et al., Citation2011). The development of giftedness requires a mixing of cognitive and non-cognitive factors. The modern interactive models of giftedness present the concept of giftedness as a complex construct that consists of various cognitive, affective, and environmental factors (e.g., Gagné, Citation2005; Heller et al., Citation2005; J. Renzulli, Citation2005; Ziegler & Stoeger, Citation2007). The researchers in the field of giftedness view these factors as interrelated and interactive, as the way individuals cognitively perform their work is influenced by and affects their emotional aspects (Abdulla Alabbasi et al., Citation2021; Ayoub & Aljughaiman, Citation2016; Ayoub et al., Citation2022; Ayoub & Ibrahim, Citation2013; Ziegler & Heller, Citation2000). This interaction stimulates the progress of performance, as ability alone is insufficient to achieve great results.

Research in the field of gifted education suggests that giftedness does not only exist within the individual but that it is necessary to consider the context, conditions, and stimulating educational opportunities that foster the advanced development of gifted performance (AlSaleh et al., Citation2021; Ayoub et al., Citation2021; Barab & Plucker, Citation2002; Coleman & Cross, Citation2005; Gagné, Citation2004, Citation2005; JS Renzulli, Citation2012; Tan et al., Citation2012). Therefore, theorists of gifted education are now considering smart contexts (Barab & Plucker, Citation2002), cultures of expertise (Stoeger & Gruber, Citation2014), and exogenous and endogenous learning resources (Ziegler et al., Citation2017), which can significantly contribute to talent development. This article discusses five endogenous and five exogenous learning resources in the context of Egypt.

1. Literature review and background

In a series of papers, Ziegler and colleagues (Ziegler & Baker, Citation2013; Ziegler et al., Citation2017) have discussed and outlined five exogenous learning resources (i.e., economic, infrastructural, cultural, social, and instructional) and five endogenous learning resources (i.e., organismic, actional, telic, attentional, and episodic) necessary for understanding talent development. We briefly describe each of the endogenous and exogenous learning resources before moving to the next section on gifted education in Egypt.

1.1. The five endogenous learning recourses

The first endogenous learning resource, organismic learning capital, consists of a person’s physiological and constitutional resources. Physical fitness is a necessary condition for high-level cognitive engagement (e.g., Bellisle, Citation2004; Gottfredson, Citation2004) and correlates with memory performance (Chaddock et al., Citation2011), IQ (Aberg et al., Citation2009), and academic achievement (Chaddock et al., Citation2011). The second endogenous learning resource, actional learning capital, refers to a person’s action repertoire, that is, the set of actions they can perform. Some studies have shown that a person’s current action repertoire is an excellent predictor of future performance (Ziegler, Citation2008). Consequently, talent development is frequently targeted toward groups of people who have already exhibited significant performance (e.g., Gershon et al., Citation1996; Roecker et al., Citation1998). Telic learning capital refers to the expected long- and short-term goals that a person sets for their future. Goals are states in the world that we want to achieve through activities and practices. Telic learning capital, or the availability of functional goals for the learning process, is a valuable resource in at least two ways throughout the pursuit of excellence. It is primarily useful in creating appropriate conditions for learning framework circumstances (e.g., scheduling rest periods so that the next learning step is taken in a state of optimal fitness, setting up a functional workspace). Second, it can set up functional learning goals that result in increased competency (Cleary & Zimmerman, Citation2001; Kitsantas & Zimmerman, Citation2002; Stoeger, Citation2002). Attentional learning capital denotes quantitative and qualitative attentional resources that a person can apply to learning. The quantity and quality of attentional learning capital are important in talent development. Numerous studies have shown that the quantity of attentional capital (e.g., the time students concentrate on their learning or homework) influences achievement levels (e.g., Klein, Citation2001; Paschal et al., Citation1984) and that students who manage to avoid distractions attain better achievements (Lupatsch & Hadjar, Citation2011; Mosle et al., Citation2006). Finally, episodic learning capital consists of patterns of action based on learners’ goals and the circumstances in which they act. Episodic learning capital differs from actional learning capital as it links accessible actions to developmental and learning goals and contextual features. Research has shown the importance of episodic learning capital in the development of excellent performance (Ericsson et al., Citation2006).

1.2. The five exogenous learning recourses

The second type of learning resource, namely, exogenous learning resources, represents the environmental component of the Actiotope Model of Giftedness (Ziegler et al., Citation2017). First, economic educational capital refers to every sort of wealth, ownership, money, or valuables that gifted learners can invest in. Previous studies have shown a relationship between students’ socioeconomic status (SES) and their academic performance (Ehmke & Jude, Citation2010). In addition, some studies have shown that top players/achievers with respect to performance in sports and music often come from families with high SES (Beamish, Citation1990; Manturzewska, Citation1990; Roring, Citation2008). The second resource, infrastructural educational capital, refers to materially implemented opportunities for actions that enable learning and education. Infrastructure educational capital affects the chances of excellence in two ways. First, it can create interest. A sports field in a neighborhood increases the probability of a child coming to play football; a nearby swimming pool increases the chance that a child will learn to swim. Second, it provides special opportunities for learning. The number of books owned by a family influences reading motivation and student achievement (Anger et al., Citation2007; Baumert et al., Citation2006; McElvany et al., Citation2009; Suchań & Bergmuller, Citation2010). Investing in infrastructure can boost academic achievement and economic growth (e.g., Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Koln, Citation2015).

Third, cultural educational capital includes students’ and parents’ values, attitudes, and beliefs regarding learning and education. Several studies have found that the more positive parents’ and peers’ values, attitudes, and beliefs about learning and education, the higher the students’ academic achievement (Fuligni, Citation1997; Ryan, Citation2000). Fourth, social educational capital includes all people and social institutions that can directly or indirectly contribute to the success of gifted learners. Several studies have found that those who excel in a specific domain such as sports, music, and management were mentors during their formative years (Stoeger et al., Citation2009). Finally, instructional educational capital refers to caregivers’ quality. More specifically, studies have shown that student achievement is influenced by the quality and qualifications of their teachers. In recent decades, average and best performance have increased in most areas. Bloom (Citation1984) emphasized the importance of one-on-one instruction, comparing a range of instructional methods and showing that one-on-one instruction provided by a pedagogically trained tutor or mentor is the most effective form of instructional capital. Studies show that instructional educational capital, especially in early childhood, plays an important role in student learning outcome (Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Koln, Citation2015).

1.3. The history of gifted education in Egypt (1962–2022)

In the nineteenth century “Mohammed Ali” sent gifted students to Europe to study new sciences in various fields. He offered a great number of scholarships to high achieving students to develop their abilities and skills, so that they could transfer what they had learnt to Egypt. The Ministry of Education (MOE) built certain special courses in 1932, as well as a teacher-training institute, which later became a model school for gifted students. In 1962, the MOE established the “Model School for the Gifted” in Ain Shams, which is regarded as Egypt’s unique center for gifted education. The Egyptian government has recently authorized some civil society organizations to open similar centers (A. Aljughaiman et al., Citation2009).

The interest in educating gifted students in Egypt returned to the beginning of the nineteenth century when outstanding students were identified from Al-Azhar Al-Sharif and sent on scholarships to Europe (Ahmed, Citation1998). Five experimental elementary school classes were established in 1932, which aimed to consider individual differences between students. This was the beginning of a new trend in education based on the project method. Students chose specific projects and implemented them under the supervision of their teachers (Mahmoud, Citation1999). Talented summer clubs were also established, which included outstanding students in the cultural, social, and athletic activities, as well as talented students in drawing and photography (Tawfik & Sabry, Citation1980). In 1955, interest in the education of highly gifted people increased when the male experimental school for talent was founded (Ministry of Education (MoE), Citation1990). In 1958, positive trends appeared toward developing giftedness in leadership among school students, which was obvious through establishing the “house of leadership.” The idea of the house of leadership is that some schools open their doors after the end of the school day to receive a selected number of outstanding secondary school students in order to prepare and train them for leadership and guidance (Mahmoud, Citation1999). In 1959, the MOE established specialized institutes for art, drama, and singing, and opening classes were initiated for gifted students in music and ballet (Alshakhs, Citation1990).

At the beginning of the 1960s, interest in tutoring gifted and talented students increased and special classes for gifted students were established in some secondary schools in the governorate of Cairo Governorate. Thereafter, these classes began to spread to other governorates, and the number of special classes increased until they reached 37 classes in the secondary stage. In addition, middle schools kept pace with the development of secondary schools by establishing special classes for outstanding students. Thus, there were 18 classes of 1,063 students in the first and second years of the middle schools, which increased to 44 classes in 1965 (Abu Allam & Al-Omar, Citation1986). In 1979, the MOE presented a new vision for discovering and nurturing gifted students at different stages based on the documentation of the development and modernization of education in Egypt. The 1990 education document stated that the Minister of Education, upon approval by the Supreme Education Council of Education, had the right to establish schools for gifted students to ensure the development of their talents in a special way (Ministry of Education (MoE), Citation1990). In 1988, a Ministerial Decree was issued regarding the establishment of classes for outstanding students in every secondary school to provide equal opportunities, consider individual differences among students, and encourage those with outstanding intellectual abilities to achieve their goals (Ministry of Education (MoE), Citation1990). In 1992, experimental schools for athletically-gifted students were established to prepare sports champions who represented their country at international forums.

In 1992, a conference was held on the development of primary education. The recommendations emphasized the need to take care of young gifted students by providing them with educational and professional programs that matched their learning needs. The MOE also hosted the National Conference for the Gifted in 2000, which addressed four main axes that were integrated to define a distinct strategy for caring for gifted students in Egypt, in a serious attempt to identify, discover, and nurture gifted students in the twenty-first century (A. Aljughaiman et al., Citation2009).

In 2011, the Egyptian MOE issued a decision to establish STEM schools which aimed at nurturing the gifted and talented students taking care of their abilities, by teaching advanced curricula in the fields of science, mathematics and technology, and developing the use of information technology methods to support the educational process and pave the way for students’ creativity and innovation (Al-Etrabiy, Citation2019).

1.3.1. Identification of gifted students in Egypt

According to the standards of the Egyptian MOE and the General Administration for Gifted and Intelligent Learning, gifted students are those who achieve a high level of intellectual and creative ability surpassing their peers in one or more areas valued by society, such as intellectual excellence, creative thinking, achievement, and special skills (Ministry of Education (MoE), Citation2000).

The Department of Education has adopted several standards for identifying giftedness, including the major scales for intelligence, ability, tendencies and trends, mental health, and standards for measuring excellence in sports and social activities. These can be used in the selection of students, whether in centers, schools, or classes (Al-Bilawi, Citation2002).

There are several methods to identify gifted students in pre-college education. One of these methods is the student’s follow-up portfolio, which includes health and family data about the student and shows how the student stands out from their peers. Another method is intelligence tests, such as the Wechsler Test for Children, the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test, and some Egyptian intelligence tests. Special tests are another method of identifying giftedness, measuring students’ abilities and special preparations in various areas, such as math, language, science, art, music, sports, and others. Moreover, achievement tests; teachers’ note lists; scientific, artistic, literary, and sports competitions; and notes of social and psychological statisticians are other methods for identifying gifted students (Al-Bilawi, Citation2002).

1.3.2. Gifted education programs in Egypt

There are two main gifted programs in Egypt: grouping and enrichment (Ayoub, Citation2018). Grouping programs include grouping gifted students in private schools (high schools for outstanding students, STEM schools, schools for the athletically-gifted, schools for the technically gifted), special classes, and outstanding care centers. The enrichment program relies on strengthening the curriculum, which provides additional courses for gifted students and regular curricula that meet their abilities and interests (Al-Etrabiy, Citation2019).

Accounting for the two types of learning resources which represents a unified whole is necessary to understand the gifted education system. The pattern of these two components can be analyzed differently according to every context and country. The current study aims to analyze the status of gifted education in Egypt based on this model, which includes 10 sub-components: five factors related to learning capital (actional learning capital, organismic learning capital, telic learning capital, episodical learning capital, and attentional learning capital) and five factors related to educational capital (economic educational capital, cultural educational capital, social educational capital, infrastructural educational capital, and didactic educational capital).

2. Method

The current study aimed to provide a comprehensive view of the existing situation of gifted education from the learning-capital perspective. With this objective, the researchers contacted the General Administration of the Egyptian MOE and the administration of STEM schools to obtain relevant reports and statistics. The researchers collected reports about the trained teachers’ and parents’ attitude toward gifted students. They were also interested in collating further data about the time and attention that gifted students devote to learning and developing their talent, whether this varies by talent area (e.g., more for athletic talent and less for math talent), the role talent plays in their motivational systems, and whether they value learning. The researchers asked gifted students to rank the activities to establish the amount of time and attention they spend on learning and their talent development.

Moreover, the researchers used the Scale on Attitudes Toward Learning to assess students’ attitudes toward learning; the researchers used the scale developed by Kara (Citation2009). The scale consists of 10 items. Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1). The scale was administered to a sample of 156 students to measure the validity of the scale of attitudes toward learning using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). From the CFA results, the fit indices of the scale were observed to be good (χ2/df = 1.47, RMSEA = 0.068, GFI = 0.96, AGFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.94). The reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α) of the scale was 0.87. This scale was administrated to 168 gifted students whose ages ranged from 16 to 18 years (M = 15.51 years, SD = 2.07) for the recognition of telic educational capital.

Additionally, an open-ended question “Name the activities on which gifted students spend a lot of time and attention to learn and develop their talent” was asked to the same sample of gifted students to measure attentional learning capital. The researchers counted the students’ responses and their frequencies, then scored them based on frequencies from the highest to the lowest, noting that at least three responses were necessary for the answer to be retained.

3. Analyzing the reality of nurturing gifted students according to the learning-resource perspective

3.1. I: exogenous educational resources

3.1.1. Economic educational capital

Economic educational capital relates to the financial and logistic support that should be offered to gifted students. Egypt’s future is heavily reliant on the abilities and resilience of its youth. Economic educational capital includes money or any other sources that can be manipulated in the learning process of gifted students. Ziegler et al. (Citation2014) believe that while economic educational capital does not play a direct role in learning and educational processes, it can be used to purchase learning materials (e.g., books, educational apps), pay for educational experiences (e.g., seminars or community), or invest in certain forms of social capital (e.g., trainers). Egypt’s topmost aim is to make education and training relevant to the country’s economic prospects. Gifted students, who will be the innovators and leaders of the next generation, represent Egypt’s hope for advancement in keeping up with civilization and progress. As a result, the Egyptian government is becoming more interested in and supportive of gifted education.

The MOE of Egypt offers gifted pupils the opportunity to participate in competitions. Egypt has been a TIMSS participant since 1999. Primary schools are funded to participate in a competition organized by the MOE and Nile Educational Television. The MOE classified STEM Education as a special education program in Egypt’s strategy plan for pre-university education (2014–2030). The MOE’s goal is to offer STEM students with a high-quality education that is suited for their many intelligences, to reinforce their potential skills, and to equip them with the tools they will need to steer the ship of education through the future world of knowledge (Ministry of Education (MoE), Citation2014).

Additionally, budgets are offered to gifted students from Talent Management and Smart Learning of the Ministry of Education in each governorate. Moreover, schools offer budget and other facilities for organizing some school summer activities for gifted students. On the other hand, parents support their children and purchase advanced laptops, musical instruments, and other equipment to develop the unique skills of their children.

The American University in Cairo (AUC), which is considered one of the most prominent universities in the Middle East, has offered numerous full scholarships for gifted students who have excelled academically. Moreover, Zwail University offered many scholarships to high achievers and gifted students to prepare them for the workforce (Ministry of Higher Education (MoE), Citation2019). However, more budget is needed to offer support and the required care for these exceptional students.

The private sector is a real driving force for young people. The field of gifted care is witnessing great support from the private sector, associations, and charitable institutions through many initiatives. For example, the Crédit Agricole Egypt’s Development Foundation 2019, in collaboration with the MOE and Ministry of Social Solidarity, launched a special program (EBHAR MISR) in 2019 to encourage and motivate gifted students aged 13 to 19 in the fields of science, technology, and art. The gifted students were encouraged to participate in a 2-week intensive course at a summer camp. The most gifted were traveling to a 1-week camp in a special school for gifted students in Florida, USA (Crédit Agricole Egypt, Citation2019).

Another example among the most prominent initiatives was the signing of a cooperation protocol between the MOE and Ministry of Culture and the Misr El Kheir Foundation, a national charity that discovers academically and technically gifted students in schools and supports their activities (Abd El Aziz, Citation2015). This protocol included the Misr El Kheir Foundation bearing the financial cost and implementing the program in terms of preparing manuals, bags, and training batteries for the project, and providing materials, tests, and scales that are necessary to implement the project. Additionally, it provided the necessary technical support for the project within community education schools.

In addition, the MOE signed a cooperation protocol with the Hayah Karima Foundation to take care of gifted children in poor environments and the neediest villages. The project aimed to develop a plan to discover and nurture gifted students in Egypt by creating a database of students in the neediest villages who need support at different stages, from an above-average level to outstanding students. In addition, a trained and qualified team was formed to take care of the classes of gifted students in cooperation with the Academy of Scientific Research and the Ministry of Higher Education, represented by the universities and the National Academy of Rehabilitation and Education (United Nations Development Programme, Citation2021).

However, the budget provided to develop the achievement progress of gifted students remains insufficient. Egypt is a big country with a large population; thus, a bigger budget is necessary to help and support gifted students and provide them with more services.

3.1.2. Cultural educational capital

Cultural educational capital includes value systems and ways of thinking that can facilitate or hinder the attainment of educational goals. The interest in caring for talented students is a title on nation’s progress and development, by which the extent of its awareness, advancement, and progress is measured. Parents who possess certain gifted skills or have a positive attitude toward particular gifted skills or aptitudes will transfer the same to their children. Positive attitudes among family or friends regarding learning resulted in better achievement among pupils (Ryan, Citation2000).

Notably, there is an increasing interest and positive attitude from the Egyptian governorate to support gifted students. Additionally, they are receiving great attention from different social groups such as teachers, parents, and researchers.

Reis and Renzulli (Citation2003) emphasize the role of teachers in the design of learning situations (e.g., real problem-oriented, inductive thinking skills) that promote creative-productive giftedness.

The most important element of any gifted education program, and the most significant influence on the learning and development of gifted students, is a teacher who is considered an important part of the environment to develop gifted students’ potential (Abdulla & Cramond, Citation2017). Dinham and Scott (Citation2000) indicated that “In education, the most crucial leaders for change are the teachers who have the final say in whether a great idea is actually put into practice in a way that works for students” (p. 8). Negative attitudes toward giftedness can affect the perceptions of gifted students and their education, and therefore influence teachers’ behavior toward these students (Lassig, Citation2009). Teachers’ attitudes not only affect their teaching practices and approaches, but can also have an indirect influence on the attitudes and behaviors of the students’ peers and the stimulating classroom climate that ensures the optimal development of talented students (Al-Makhalid, Citation2012; Cross et al., Citation2018; Lassig, Citation2009).

Gifted students are often sensitive to their own feelings and those of others, and highly concerned about interpersonal relationships, intrapersonal states, and moral issues (Neihart et al., Citation2002). In short, gifted students are self-aware, self-assured, socially skilled, and morally responsible. Many of these students are happy, well-liked by their peers, emotionally stable, and self-sufficient (Alhamdan et al., Citation2017; Neihart et al., Citation2002).

Third-grade students of secondary schools in STEM schools practice sports activities, and at the end of each semester, a practical exam is held for them in the school. Students also choose from a range of activities (artistic activity, innovative activity, theater and drama, journalism and media, community service and environmental development, libraries and skills research, information, and communication technology) and practice the activity in the two-semester system followed in the school. However, more public or private schools are needed that can cater to the high percent of gifted students in Egypt. Further, a more positive attitude from the surrounding environment is necessary to encourage gifted students to do their best (El Nagdi & Roehrig, Citation2020).

3.1.3. Social educational capital

Social educational capital mainly represents teachers, the school administration, university professors, and parents, who play a core role in the development of talented students (Subotnik et al., Citation2012). Putnam (Citation2000) states that social capital in school strongly shapes the future of children and youth. The teacher is the cornerstone in the educational system. However, there appears to be a lack of training for teachers to appropriately deal with gifted students. Arguably, all teachers who work with gifted students should have formal training. Such training should focus on testing and assessment, instructional strategies and models, social emotional needs and development, and working with families (Ford & Grantham, Citation2003). In Egypt, despite outstanding educational efforts in this field, the school administrations vary in the extent to which they offer the required care for gifted students. To achieve the objectives of the strategic plan for pre-university education in Egypt, which states: “Providing talented and outstanding learners with high-quality education in the areas of knowledge and advanced skills in proportion to their individual abilities and skills, and investing in their multiple intelligences, in addition to supporting and developing their talents, aptitudes and abilities. Enabling them to lead the nation’s ship in the world of knowledge” (Ministry of Education (MoE), Citation2014, p. 84).

After regular school hours, classrooms are also available to students to study and work in groups. Some experienced students, in cooperation with teachers, have established study groups to provide academic guidance and direction to younger students after regular school hours. Bass (Citation2014) asserted that boarding schools play a significant role in strengthening social relationships among students, which promotes students’ academic performance.

There was no specific training for teachers of gifted students, except that some faculty members established departments of special education sections at the undergraduate level, where students and teachers take some courses on intellectual superiority and the psychology of giftedness, as well as preparing teachers at the graduate level. Before the establishment of STEM schools in 2011, there were no special programs in Egypt to prepare gifted teachers. To increase the efficiency of teachers, the MOE has developed a plan to send teachers annually for training to universities in the United Kingdom, the United States of America, France, and Ireland. The main aim of this initiative is for teachers to acquire modern teaching strategies and know how to use advanced technology as an educational tool, especially in the fields of science, mathematics, English, and French (Elnashar & Elnashar, Citation2019).

After establishing STEM schools, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) supported the development of specialized trainers and administrators to teach and manage STEM schools throughout Egypt. In collaboration with many U.S. universities, the project is implementing a 4-year bachelor’s degree program in science and technology education at five Egyptian public universities, to ensure that future teachers are well prepared and acquire skills and experience that will improve the quality of teaching and learning in STEM schools. The project also offers a 1-year postgraduate diploma for teachers and school administrators, focusing on science and technology. USAID continues to support the MOE and Technical Training in the management and continuity of the STEM school system (Elfarargy, Citation2016). The project supported the in-service training process for teachers and administrators. It also strengthened the supporting administrative units for schools and supported the Ministry in implementing a plan to expand science and technology teaching.

That parents play a crucial role in supporting their gifted children is undeniable. In Egypt, parents need more information and training in order to properly nurture this national wealth. More specialized staff are needed to offer help for parents to gain further awareness on ways to support their gifted children and develop their abilities and skills. In addition, we do not have parents’ associations to provide parents an opportunity to discuss their experiences with their talented children or the different issues related to them.

3.1.4. Infrastructural educational capital

Infrastructure educational capital is regarded as a necessary component since it can provide specialized learning opportunities and arouse interest (Ziegler et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). Gifted students require special infrastructures such as special centers, schools, labs, libraries, playgrounds, and technological devices to facilitate learning and develop learning outcomes. Gifted and smart learning centers aim to adopt and nurture gifted students, hone their abilities and skills, and encourage them to innovate and create. In 2021, the number of centers for gifted and intelligent students learning in pre-college education reached 57, covering 20 governorates. All centers are equipped with internet, devices, books, and reference works on talent and creativity that are necessary for gifted students to develop their talents. They also exhibit excellent artwork of gifted students from all educational levels to show their creativity and innovation (OECD, Citation2015).

In addition, the school library, which is run by a group of volunteer students, is available to students for reading after regular school hours. STEM subject teachers and a group of volunteer students usually supervise after-school activities and maintain a record of the chemicals, physical instruments, and tools that students need to prepare for their projects.

In the field of higher education and within the framework of the National Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation (2015–2030), the Ministry of Higher Education in Egypt has established a fund for mentoring innovators by creating an environment conducive to innovation through the adoption and implementation of innovative mechanisms for projects in the fields of science, technology, and innovation (Ministry of Higher Education (MoE), Citation2019). Additionally, the Egyptian Supreme Council of Universities decided to establish centers for the care of talented and creative students in universities, including several units (artistic, literary, scientific, and technological talents).

Egypt has been making the best efforts to develop relevant infrastructure. The reform is in keeping with Egypt’s long-term vision for economic, environmental, and social growth, Vision 2030. EDU 2.0 is expected to be fully implemented by 2030, replacing the country’s conventional culture of memorizing for exams with one that emphasizes student-centered teaching and competency-based learning for life, as well as technological expertise. In addition, six public institutions began the first phase of a three-part digitization strategy in 2019, with the goal of making all curricula and interactive courses available online in the future. During the first phase, these universities abandoned textbooks in favor of e-books. Within 2 years, the strategy will be fully implemented throughout all public colleges, with the goal of saving students and families’ money on course materials. However, there have been fears that the initial cost of technology will be very high and that the government will not be able to provide all of the equipment.

3.1.5. Didactic educational capital

Didactic educational capital includes all procedural and declarative knowledge relevant to improving educational and learning processes. Indeed, the quality of the educational process can be developed if sufficient didactic instructional capital is available. In the domain of scholastic achievement, teacher training quality and the availability of special curricula have an impact on students’ performance.

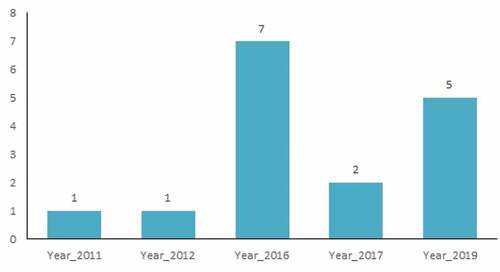

Under the National Project of Egypt (Together We Can), the MOE has classified STEM as a special education program. The first STEM school in Egypt was established in October 2011. STEM schools were established in Egypt with funding from USAID. shows the growth of STEM schools in Egypt between 2011 and 2019. Students are accepted into STEM schools based solely on their placement test scores (Ministry of Education (MoE), Citation2012). The main aim of the MOE is to deliver high-quality education represented in special curricula developed for gifted STEM students, which is appropriate for their multiple intelligences. The kind of learning provided to STEM students should reinforce their potential skills and equip them with the required tools for developing education through the world of knowledge (Ministry of Education (MoE), Citation2014).

STEM schools offer housing for students, as they come from various Egyptian governorates (Ministry of Education (MoE), Citation2012).

In Egypt, the MOE has prepared a plan to develop the teaching quality of teachers by sending them for training in the United Kingdom, the United States of America, France, and Ireland. Many training programs are offered to them to develop their teaching strategies, which has positive impacts on their students (Elnashar & Elnashar, Citation2019). More trained and qualified teachers who can cope with the potential of gifted students are required. In addition, faculties of Education in Egypt should have a certain section for those students to teach them right from the kindergarten stage. Additionally, the curricula should be tailored to suit the learning needs of gifted students and to help them develop their creativity and skills.

3.2. II: endogenous educational resources

3.2.1. Actional learning capital

Egypt is one of the top five countries with the most significant improvement in average performance in math and science in eighth grade within 4 years, between 2015 and 2019. Egyptian students’ performances improved in mathematics from 392 to 413, with an average increase of 21%. In science, student performance improved from 371 to 389, with an average increase of 18 points (Ramadan et al., Citation2019).

Egypt won many medals and awards in various international competitions. The MOE in Egypt also motivated talented and outstanding students in mathematics and science from public and STEM schools to participate in international competitions. These international competitions include: Intel ISEF, International Physics Olympiad, International Biology Olympiad, International Mathematics Olympiad, International Computer Science Olympiad in Informatics, Arab Chemistry Olympiad, Mediterranean Youth Mathematical Championship, Genius Olympiad, International Astronomy and Astrophysics Competition, First Lego League, Nasa Space Apps, Diamond Challenge, Z-Dare Entrepreneurship Challenge, International Youth Math Challenge, Global Math Challenge, and Mathematical Kangaroo (USAID, Citation2017).

3.2.2. Organismic learning capital

The physiological and constitutional resources of a human being are referred to as organismic learning capital. Correlations have been detected between fitness and IQ (Aberg et al., Citation2009). Schools should ensure that gifted students are in the best physical health with respect to their nutrition, general health, and sleep habits. In Egypt, STEM schools provide students with room and board throughout the day. The school day in STEM schools begins each morning with half an hour of physical exercises and running. In addition, breakfast is taken before the start of the school day and lunch at the end of the school day. After that, students have free time to watch T.V. or pursue their hobbies (Al-Qurashi, Citation2014). STEM schools take great interest in the general health and food habits of the students to improve the quality of their learning. Espinosa-Curiel et al. (Citation2020) stressed on the effect of student health on learning quality.

Students have the opportunity to play sports in their free time after school. However, there are no physical education teachers in schools to supervise these sports activities. Therefore, the students themselves organize sports competitions, where the winning teams are recognized in the morning and they receive prizes. These sports activities aim to help students refresh their minds and build strong social relationships with other classes, grades, and school peers, which improves their learning environments (Kim, Citation2001). Gifted students need a physical education teacher who can help each one of them. Additionally, they should be supported to follow a certain diet or eat healthy foods, as a good mind is maintained in a good body.

3.2.3. Telic learning capital

Telic capital refers to the availability of learning goals. Students that are alienated from school, for example, may have very few or no learning objectives (Ziegler & Baker, Citation2013). Telic learning capital relates to the role of the development of talents by promoting student motivation and their attitudes toward learning.

To determine students’ attitudes toward learning, the researchers used the Attitude Toward Learning Scale. A one-sample t-test was used for data analysis. shows the mean, standard deviation, and t -values. demonstrates that the mean values of the items on the scale of attitude toward learning were high and statistically significant (P < 0.001). These results indicate a high and positive level of gifted students’ attitudes toward learning.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and t-values for students’ responses on the attitude toward learning scale

3.2.4. Episodic learning capital

Episodic learning capital refers to the cognitive resources that assist an individual in determining the appropriate action for accomplishing desired goals in a particular situation (Ziegler et al., Citation2014). Therefore, it represents an important element in the development of gifted students. Developing a sufficient amount of episodic learning capital for performing excellent actions involves a considerable amount of time investment (Ziegler et al., Citation2014). In Egypt, gifted students who join the STEM school are more enthusiastic and enjoy the learning programs as they have a fair and good education that aligns with their abilities. Therefore, they are able to make the best achievements in light of their abilities, thereby enabling the best investment of time. The class atmosphere is a competitive one that encourages students who face problems in certain tasks to practice more and invest more effort to be at par with their classmates. This in turn creates a competitive spirit among students, which guarantees their development and improves their learning outcomes. However, gifted students need more focus on their individual differences. Teachers are always teaching them in the same manner without paying particular attention to their different goals. Gifted students are unique, even when it comes to determining and achieving their goals; thus, more attention to their individual differences is required.

3.2.5. Attentional learning capital

All of the quantitative and qualitative attentional resources that an individual can focus on during the execution of learning tasks are referred to as attentional learning capital. In terms of quality, attentional learning capital refers to the resources available to a person for learning, studying, or practicing in a focused and efficient manner. According to some experts, attentional learning capital is the most essential contributing component toward improving a skill or learning domain (Ziegler et al., Citation2014).

Students attended different programs and workshops, which proved to increase their interest and attention and in turn developed their learning outcomes. The teachers and trainers noted that attention problems remain an important issue that gifted students face as they can lose their attention during trainings of long duration. Thus, efforts must be made to enhance student interest, attention, and learning outcomes.

The researchers received 11 responses for the open-ended question “Name the activities on which gifted students spend a lot of time and attention to learn and develop their talent.” With regard to the frequency of the activities from the highest to the lowest, the top six areas were math (81%), science (76%), technology (64%), physical education (43%), free reading (29%), and music (29%).

4. Discussion and conclusions

The main target of any educational system is to acquire information and obtain different research results to improve learning outcomes. The information and research results thus derived are necessary for educational policy makers and the educational authority to improve learning quality, especially for gifted students. Given this background, the current study was mainly designed to obtain more information and data about the real situation of the education of gifted students in Egypt from a learning-resource perspective. It was rather challenging to provide a general overview of the services and opportunities developed for gifted students and identifying those that they still need. This type of research is integral for gifted education to direct the educational administrations to do their best based on this information, toward developing the outcomes of exceptional students.

The current study involved examining the learning resources that are internal and external to the individual, as both internal and external learning resources can be considered as key elements in educational reform efforts for gifted students. The results showed that the Egyptian government supports gifted students’ participation in national, regional, and international competitions. Moreover, Egyptian students showed the largest improvement in the average performance in math and science in eighth grade between 2015 and 2019. Additionally, they are taking into account the individual differences between gifted students. Students have unique goals that are in line with their talents; thus, each student needs different services and opportunities. This is why STEM schools provide gifted students with different programs and activities not just in regular education classes, but also throughout the day.

The Egyptian government also offers financial and material support to gifted students, as evidenced by the numerous initiatives that encourage the participation of gifted students in advanced programs within and outside Egypt. Importantly, this support for gifted and talented students comes from both the private and public sectors. These findings are in line with some studies that support gifted students (Aljughaiman & Ayoub, Citation2012, Citation2013; Ayoub, Citation2018; A. M. Aljughaiman et al., Citation2017). However, the budget provided to develop the achievement progress of gifted students is insufficient, and a larger budget is required. One of the limitations of the current study is the absence of data regarding parents’ actual investment in their children’s education. This is an important area of future research.

In terms of infrastructure, it can be said that there is great care and support from the Egyptian government, as evidenced by the number of centers that offer special programs for gifted learners. These centers are fully equipped with all the materials necessary for gifted students to fulfill their potential and promote their giftedness. In addition, the Egyptian government has established STEM schools that provide advanced education in STEM fields. STEM schools provide room and board for all students and strive to provide an optimal environment that promotes their mental and physical health. The results of our study revealed that more public or private schools are needed given the large student population in Egypt. Additionally, more equipped centers are required to provide gifted students with different services at any time.

Considering the crucial role of parents, they still need more information and awareness programs to support their gifted children and show a positive attitude toward their learning. A positive attitude from the surrounding environment can help to encourage gifted students and improve their learning outcomes. Gifted and talented students need well-trained teachers to provide them the opportunity to develop their skills. Additionally, the curricula should be tailored to gifted students, to help them develop their creativity and skills.

Finally, in terms of attention learning capital, the main question this article sought to answer was how much time and attention is devoted to learning and talent development. The results showed that gifted learners spend different amounts of time depending on the area of giftedness. However, gifted students can lose their attention during trainings of long duration. Thus, measures should be taken to enhance their interest; they should have a certain goal that raises their attention and learning outcomes.

This study has two limitations. First, some of the current findings are not based on new data. This is true for the following learning resources: (a) economic educational capital, (b) social educational capital, and (c) organismic learning capital. Future research could expand the current study by collecting data on these three learning resources. Second, the sample size collected for this study is considered small compared to the number of gifted students in Egypt. Therefore, the results of the current study should be replicated with a larger sample.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alaa Eldin A. Ayoub

Alaa Eldin A. Ayoub is a full professor of Measurement, Evaluation and Statistics at Aswan University in Egypt, and Arabian Gulf University in Bahrain. He had more than 50 research papers in various international periodicals and translated books. Prof. Alaa Ayoub had received multiple scientific awards such as Khalifa Award of Education, Hamdan Award, and Rashid Bin Humaid Cultural & Sciences Award (UAE).

Ahmed M. Abdulla Alabbasi

Ahmed M. Abdulla Alabbasi is the Head of the Department of Gifted Education at the Arabian Gulf University. Dr. Ahmed earned his PhD in Gifted and Creative Education from the University of Georgia. He also earned professional certificates in leadership and innovation from Harvard University. His research interests include creativity, giftedness, divergent thinking, problem finding, and emotional intelligence.

Ahmed Morsy

Ahmed Abdelsabour Morsy worked as specialist of Special Education (Giftedness and Talented) in Ministry of Education, United Arab Emirates between 2008 – 2015, and he is currently working as Giftedness Identification Officer in Hamdan Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Foundation for Distinguished Academic Performance.

References

- Abd El Aziz, N. (2015). Egyptian STEAM international partnerships for sustainable development. International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education, 5(4), 2656–18.

- Abdulla, A. M., & Cramond, B. (2017). After six decades of systematic study of creativity: What do teachers need to know about what it is and how it is measured? Roeper Review, 39(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2016.1247398

- Abdulla Alabbasi, A. M., Ayoub, A., & Ziegler, A. (2021). Are gifted students more emotionally intelligent than their non- gifted peers? A meta-analysis. High Ability Studies, 32(2), 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2020.1770704

- Aberg, M. A., Pedersen, N. L., Torén, K., Svartengren, M., Bakstrand, B., Johnsson, T., Kuhn, H. G., Åberg, N. D., Nilsson, M., & Kuhn, H. G. (2009). Cardiovascular fitness is associated with cognition in young adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(49), 20906–20911. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0905307106

- Abu Allam, R., & Al-Omar, B. (1986). Preparing a program for the care of mentally gifted children. Educational Journal, 11(3), 1–28.

- Ahmed, S. (1998). The evolution of educational thought. Alam Alkutub.

- Al-Bilawi, H. (2002). Efforts of the ministry of education in the field of caring for and encouraging the gifted and talented. The fifth scientific conference, education of the gifted and talented, the introduction to the era of excellence and creativity, (14–15 December), Faculty of Education, Assiut University, Egypt.

- Al-Etrabiy, H. (2019). A proposal to develop STEM schools in light of global trends: A field study on STEM schools in Egypt. Journal of University Performance Development, 8(1), 3–78.

- Al-Makhalid, K. A. (2012). Primary teachers’ attitudes and knowledge regarding gifted pupils and their education in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia(doctoral dissertation). University of Manchester, School of Education.

- Al-Qurashi, A. (2014). Schools for excellence in science and technology (STEAM). Helwan University. Website of the Faculty of Education

- Alhamdan, N. S., Aljasim, F. A., & Abdulla, A. M. (2017). Assessing the emotional intelligence of gifted and talented adolescent students in the kingdom of Bahrain. Roeper Review, 39(2), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2017.1289462

- Aljughaiman, A., Ayoub, A., Maajeeny, O., Abuoaf, T., Abunaser, F., & Banajah, S. (2009). Evaluating gifted enrichment program in schools in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia: Ministry of Education.

- Aljughaiman, A., & Ayoub, A. (2012). The effect of an enrichment program on developing analytical, creative, and practical abilities of elementary gifted students. J. Educ. Gift, 35(2), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353212440616

- Aljughaiman, A., & Ayoub, A. (2013). Evaluating the effects of the oasis enrichment model on gifted education: A meta-analysis study. Talent Dev. Excell, 5(1), 99–113.

- Aljughaiman, A. M., Ayoub, A., Wechsler, S., & Sarouphim-McGill, K. M. (2017). Giftedness in Arabic environments: concepts, implicit theories, and the contributed factors in the enrichment programs. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1364900

- AlSaleh, A., Abdulla Alabbasi, A. M., Ayoub, A., & Hafsyan, A. S. M. (2021). The effects of birth order and family size on academic achievement, divergent thinking, and problem finding among gifted students. Journal for the Education of Gifted Young Scientists, 9(1), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.17478/jegys.864399

- Alshakhs, A. (1990). Gifted students in pre-university schools in the Arab Gulf Countries: Methods of their identification and ways of nurturing them. Arab Bureau of Education for the Gulf Countries.

- Anger, C., Plunnecke, A., & Troger, M. (2007). Renditen der bildung—investitionen in den frühkindlichen bereich [yields of education—investing in early childhood]. Chancen der Energiewende, 26, 40–47. https://www.diw.de/de/diw_01.c.457838.de/publikationen/wochenberichte/2013_26_8/investitionen_in_bildung__fruehkindlicher_bereich_hat_grosses_potential.html

- Ayoub, A., & Ibrahim, U. (2013). Teachers’ assumptions underlying identification of gifted and talented students in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Learning Management Systems, 1(1), 28–90. https://doi.org/10.12785/ijlms/010105

- Ayoub, A., & Aljughaiman, A. (2016). A predictive structural model for gifted students’ performance: A study based on intelligence and its implicit theories. Learning and Individual Differences, 51, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.018

- Ayoub, A. (2018). The effect of enrichment programs on improving mental flexibility and inventive work behavior for gifted students: A value-added study. Int. J. Interdiscip. Soc. Sci. Stud, 4, 11–24.

- Ayoub, A., Abdulla Alabbasi, A., & Plucker, J. (2021). Closing poverty-based excellence gaps: Supports for low-income gifted students as correlates of academic achievement. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 44(3), 286–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/01623532211023598

- Ayoub, A., Aljughaiman, A., Abdulla Alabbasi, A. M., & Abo Hamza, E. (2022). Do intelligence and its implicit theories vary based on gender and grade level? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 712330. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.712330

- Barab, S. A., & Plucker, J. A. (2002). Smart people or smart contexts? Cognition, ability, and talent development in an age of situated approaches to knowing and learning. Educational Psychologist, 37(3), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3703_3

- Bass, L. R. (2014). Boarding schools and capital benefits: Implications for urban school reform. The Journal of Educational Research, 107(107), 16–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2012.753855

- Baumert, J., Stanat, R., & Watermann, R. (Eds.). (2006). Disparitäten im bildungswesen: differenzielle bildungsprozesse und probleme der verteilungsgerechtigkeit [disparities in education: Differential educational processes and problems of distributive justice]. VS Verlag fur Sozialwissenschaften.

- Beamish, R. (1990). The persistence of inequality: An analysis of participation patterns among Canada’s high-performance athletes. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 25(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269029002500204

- Bellisle, F. (2004). Effects of diet on behavior and cognition in children. British Journal of Nutrition, 92(S2), 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN20041171

- Bloom, B. S. (1984). The 2 sigma problem: The search for methods of group instruction as effective as one-to-one tutoring. Educational Researcher, 13(6), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X013006004

- Chaddock, L., Hillman, C. H., Buck, S. M., & Cohen, N. J. (2011). Aerobic fitness and executive control of relational memory in preadolescent children. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 43(2), 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e9af48

- Cleary, T. J., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2001). Self-regulation differences during athletic practice by experts, non-experts, and novices. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 13(2), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/104132001753149883

- Coleman, L. J., & Cross, T. L. (2005). Being gifted in school: An introduction to development. In guidance, and teaching. Prufrock Press.

- Crédit Agricole Egypt (2019). Ebhar misr program for talented children.sustainability & innovation for creating an impact. https://www.ca-egypt.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CAE_Sustainability_Report_CSR.pdf

- Cross, T. L., Cross, J. R., & O’Reilly, C. (2018). Attitudes about gifted education among Irish educators. High Ability Studies, 291, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2018.1518775

- Dinham, S., & Scott, C. (2000). Moving into the third, outer domain of teacher satisfaction. Journal of Educational Administration, 38(4), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230010373633

- Ehmke, T., & Jude, N. (2010). Soziale Herkunft und Kompetenzerwerb. In E. Klieme, C. Artelt, J. Hartig, N. Jude, O. Köller, M. Prenzel, W. Schneider, & P. Stanat (Eds.), PISA 2009. Bilanz nach einem Jahrzehnt (pp. S. 231–254). Waxmann.

- El Nagdi, M., & Roehrig, G. (2020). Identity evolution of STEM teachers in Egyptian STEM schools in a time of transition: A case study. International Journal of STEM Education, 7(41), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00235-2

- Elfarargy, H. A. (2016). Investigating project-based learning (PBL) in a STEM school in Egypt: A case study [Master’s Thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain.

- Elnashar, E., & Elnashar, Z. (2019). Egyptian school of STEM and the needs for the labor market of teacher of excellence throw higher education. Scientific Journal Herald of Khmelnytskyi National University, 271(2), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.31891/2307-5732-2019-271-2-221-227

- Ericsson, K. A., Charness, N., Feltovich, P. J., & Hoffman, R. R. (Eds.). (2006). The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Espinosa-Curiel, I. E., Pozas-Bogarin, E. E., Martínez-Miranda, J., & Pérez-Espinosa, H. (2020). Relationship between children's enjoyment, user experience satisfaction, and learning in a serious video game for nutrition education: Empirical pilot study. JMIR Serious Games, 8(3), e21813. https://doi.org/10.2196/21813

- Ford, D., & Grantham, T. (2003). Providing access for culturally diverse gifted students from deficit to dynamic thinking. Theory Into Practice, 42(3), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4203_8

- Fuligni, A. J. (1997). The academic achievement of adolescents from immigrant families: The role of family background, attitudes, and behavior. Child Development, 68(2), 351–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01944.x

- Gagné, F. (2004). Transforming gifts into talents: The DMGT as a developmental theory. High Ability Studies, 15(2), 119–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359813042000314682

- Gagné, F. (2005). From gifts to talents: The DMGT as a developmental model. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (pp. 246–279). Cambridge University Press.

- Gershon, B.-S., Kiderman, I., & Beller, M. (1996). Comparing the utility of two procedures for admitting students to liberal arts: An application of decision-theoretic models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 56(1), 90–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164496056001006

- Gottfredson, L. S. (2004). Life, death and intelligence. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 4(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1891/194589504787382839

- Heller, K. A., Perleth, C., & Lim, T. K. (2005). The munich model of giftedness designed to identify and promote gifted students. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 172–197). Cambridge University Press.

- Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Koln. (2015). Bildungsmonitor 2015. ein blick auf bachelor und master [educational monitor 2015. a look at bachelor and master]. http://www.insm-bildungsmonitor.de/pdf/Forschungsbericht_BM_Langfassung.pdf

- Kara, A. (2009). The effect of a ‘learning theories’ unit on students’ attitudes towards learning. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 34(3), 100–113. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2009v34n3.5

- Kim, B. (2001). Social constructivism. In M Orey (Ed.) Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Jacobs Foundation. Retrieved http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/

- Kitsantas, A., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Comparing self-regulatory processes among novice non-expert, and expert volleyball players: A microanalytic study. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14(2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200252907761

- Klein, J. (2001). Attention, scholastic achievement and timing of lessons. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 45(3), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830120074224

- Lassig, C. J. (2009). Teachers’ attitudes towards the gifted: The importance of professional development and school culture. Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 18(2), 32–42. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/32480/

- Lupatsch, J., & Hadjar, A. (2011). Determinanten des geschlechterunterschieds im schulerfolg: ergebnisse einer quantitativen studie aus bern [determinants of gender differences in educational attainment: results of a quantitative study from Bern. In A. Hadja (Ed.), Geschlechtsspezifische Bildungsungleichheiten (pp. 177–202). VS Verlag fur Sozialwissenschaften.

- Mahmoud, Y. (1999). Teaching talented students in Egypt in light of contemporary global trends. Journal of Egyptian Ministry of Education, 6(14), 121–148.

- Manturzewska, M. (1990). A biographical study of the life-span development of professional musicians. Psychology of Music, 18(2), 112–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735690182002

- McElvany, N., Becker, M., & Ludtke, L. (2009). Die bedeutung familiarer merkmale fur lesekompetenz, wortschatz, lesemotivation und leseverhalten [the importance of family characteristics on reading skills, vocabulary, reading motivation and behavior]. Zeitschrift Für Entwicklungspsychologie Und Pädagogische Psychologie, 41(3), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1026/0049-8637.41.3.121

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (1990). Preparing a generation of scholars and nurturing outstanding students. Journal of Egyptian Ministry of Education, 4, 1–36.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (2000). Ministerial resolution no. 98 of 1999 regarding the competition of mental ability tests and the ability to creative thinking for students applying for the examination in the outstanding classes in the secondary school. Egypt.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (2012). Ministerial decree 382/2012. Egypt.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). (2014). Egypt pre-university education strategic plan: 2014-2030. Ministry of Education Egypt.

- Ministry of Higher Education (MoE) (2019). National strategy for science, technology and innovation 2030. Egypt. http://portal.mohesr.gov.eg/en-us/Documents/sr_strategy.pdf

- Mosle, T., Kleimann, M., Rehbein, F., & Pfeiffer, C. (2006). Mediennutzung, Schulerfolg, jugendgewalt und die krise der jungen [media usage, school success, youth violence and the crisis of boys]. Zeitschrift für Jugendkriminalrecht und Jugendhilfe, 3, 295–309.

- Neihart, M., Reis, S. M., Robinson, N. M., & Moon, S. M. (Eds.). (2002). The social and emotional development of gifted children: What do we know? Prufrock Press Inc.

- OECD (2015). Schools for skills: A new learning agenda for Egypt. https://www.oecd.org/countries/egypt/Schools-for-skills-a-new-learning-agenda-for-Egypt.pdf

- Paschal, R. A., Weinstein, T., & Walberg, H. J. (1984). The effects of homework on learning: A quantitative synthesis. The Journal of Educational Research, 78(2), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1984.10885581

- Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of american community. Simon and Schuster.

- Ramadan, R., Hasseb, H., & Ahmed, K. (2019). Egypt: TIMSS 2019 Encyclopedia. TIMSS & PIRLS international study centre, Lynch school of education. Boston College. https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2019/encyclopedia/egypt.html

- Reis, S. M., & Renzulli, J. S. (2003). Research related to the schoolwide enrichment triad model. Gifted Education International, 18(1), 15–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142940301800104

- Renzulli, J. (2005). Applying gifted education pedagogy to total talent development for all students. Theory into Practice, 44(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4402_2

- Renzulli, J. S. (2012). Re-examining the role of gifted education and talent development for the 21st century: A four-part theoretical approach. Gifted Child Quarterly, 56(3), 150–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986212444901

- Roecker, K., Schotte, O., Niess, A. M., Horstmann, T., & Dickhuth, -H.-H. (1998). Predicting competition performance in long-distance running by means of a treadmill test. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 30(10), 1552–1557. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199810000-00014

- Roring, R. W. (2008). Reviewing expert chess performance: A production-based theory of chess skill (Doctoral dissertation, Florida State University).

- Ryan, A. M. (2000). Peer groups as a context for the socialization of adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and achievement in school. Educational Psychologist, 35(2), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3502_4

- Sternberg, R. J., Jarvin, L., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2011). Explorations in giftedness. Cambridge University Press.

- Stoeger, H. (2002). Soziale Performanzziele im schulischen Leistungskontext [Socialperformancegoals in scholasticcontexts]. Logos.

- Stoeger, H., Ziegler, A., & Schimke, D. (2009). Mentoring: Theoretische Hintergründe, empirische Befunde und praktische Anwendungen [Mentoring: Theoretical background, empirical results, and practical implementation]. Pabst.

- Stoeger, H., & Gruber, H. (2014). Cultures of expertise: The social definition of individual excellence. Talent Development & Excellence, 6(1), 1–10.

- Subotnik, R. F., Olszewshi-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. C. (2012). Rethinking giftedness and gifted education: A proposed direction forward based on psychological science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(1), 3–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100611418056

- Suchań, B., & Bergmuller, S. (2010). Leistungsunterschiede zwischen Schulen [Performance differences between schools. In B. Suchań, C. Wallner-Paschon, & C. Schreiner (Eds.), TIMSS 2007. Mathematik und Naturwissenschaft in der Grundschule (pp. 214–231). Leykam.

- Tan, M., Mourgues, C., Aljughaiman, A., Ayoub, A., Mandelman, S. D., & Zbainos, D. (2012). What the shadow knows: assessing aspects of practical intelligence with aurora’s toy shadows. In H. Stoeger, A. Aljughaiman, B. Harder (Eds.), Talent development and excellence. (pp. 211–240). LIT.

- Tawfik, A., & Sabry, H. (1980). The ministry of education in Egypt and its most prominent achievements (1937-1979). The National Center for Educational Research and Development.

- United Nations Development Programme (2021). Development, a right for all: Egypt’s pathways and prospects: Egypt human development report. Ministry of Planning and Economic Development.

- USAID (2017). Egypt STEM school project. ESSP Final Report, USAID/Egypt Cooperative Agreement No. AID 263-A-12-00005.

- Ziegler, A., & Heller, K. A. (2000). Conceptions of giftedness from a meta-theoretical perspective. In K. A. Heller, F. J. Monks, R. J. Sternberg, & R. F. Subotnik (Eds.), International handbook of giftedness and talent (2nd ed., pp. 3–21). Elsevier.

- Ziegler, A., & Stoeger, H. (2007). The Germanic view of giftedness. In S. N. Phillipson & M. McCann (Eds.), What does it mean to be gifted? Socio-cultural perspectives (pp. 65–98). Erlbaum.

- Ziegler, A. (2008). Hochbegabung [Giftedness]. UTB.

- Ziegler, A., & Baker, J. (2013). Talent development as adaption: The role of educational and learning capital. In S. Phillipson, H. Stoeger, & A. Ziegler (Eds.), Exceptionality in East-Asia: Explorations in the actiotope model of giftedness (pp. 18–39). Routledge.

- Ziegler, A., Stoeger, H., Balestrini, D., Phillipson, S. N., & Phillipson, S. (2014). Systemic gifted education. In J. R. Cross, C. O'Reilly, T. L. Cross (Eds.), The handbook of secondary gifted education (pp. 15–55). Prufrock.

- Ziegler, A., Chandler, K. L., Vialle, W., & Stoeger, H. (2017). Exogenous and endogenous learning resources in the actiotope model of giftedness and its significance for gifted education. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 40(4), 310–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353217734376

- Ziegler, A., Balestrini, D. P., & Stoeger, H. (2018). An international view on gifted education: Incorporating the macro-systemic perspective. In S. Pfeiffer (Ed.), Handbook of giftedness in children (pp. 15–28). Springer.

- Ziegler, A., Debatin, T., & Stoeger, H. (2019). Learning resources and talent development from a systemic point of view. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1445(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14018