Abstract

Educational entrepreneurship refers to the competence of educational entrepreneurs in making changes and taking initiatives in vision-driven innovation and value creation. Research of educational entrepreneurship needs further investigation, especially in the context of complementary education. This paper explores the educational entrepreneurship of three principals working in the context of community language schools (CLSs) in Australia. Using a set of educational entrepreneurship traits as an analytical tool, this study conducts a detailed qualitative analysis of the interviews and reflective journals of three CLS principals to reveal their educational entrepreneurial traits displayed in the process of establishing and running the CLSs. Findings indicate that these principals display multiple educational entrepreneurial traits in combination when dealing with challenges encountered in their individual context. The empirical data enriches the understanding of the distinctive features of educational entrepreneurship, especially the influence of prior experience. The findings reveal some key traits and practices of educational entrepreneurship amongst CLS principals in the Australian context. This study provides context-specific empirical evidence to better understand the nature and features of educational entrepreneurship. The findings highlight the need for more research and explicit training of entrepreneurial skills for school leaders in non-mainstream schools.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Most research on educational entrepreneurship focused on mainstream schools. However, school leaders’ practice in complementary education, such as community languages school (CLSs) in Australia, is entrepreneurship oriented and could enrich entrepreneurship education. This paper explored three CLS principals’ entrepreneurial traits and competency. The findings revealed some patterns in terms of the combination of traits and highlighted that participants’ prior experience played an important role in their decision making and entrepreneurial practice. This study provides empirical evidence for experiential-based entrepreneurship education.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship was researched extensively across different disciplines during the 1980s and subsequently introduced into the field of education (Keyhani & Kim, Citation2020). In education, entrepreneurship usually refers to the competence of making changes and taking initiatives, in vision-driven innovation and value creation (Borasi & Finnigan, Citation2010; Campbell, Citation2019; Haara & Jenssen, Citation2016). However, research of educational entrepreneurship needs further investigation, especially the use of context-specific empirical studies to unpack the nature and key features of such attributes (Keyhani & Kim, Citation2020; Yemini, Citation2018). In order to fill this research gap, this study aims to explore and identify the key traits of educational entrepreneurship of three principals working in community languages schools (CLSs) in both metropolitan central and remote regions in New South Wales, Australia. As a type of complementary school, CLSs are facing many constraints, especially limited funding, and operational support (Mau et al., Citation2009; Thorpe, Citation2011). Principals of CLSs usually establish their schools based on their visions and are more proactive and innovative in seeking different funding sources and attracting students (Thorpe, Citation2011). Therefore, their practice could be viewed as entrepreneurial (Eyal & Inbar, Citation2003; Smith & Peterson, Citation2006) or entrepreneurship oriented. The insights gained from case studies of CSL principals are expected to enrich the understanding of the nature and distinctive features of a type of educational entrepreneurship.

2. The CLS in Australia

Community languages schools (CLSs) in Australia are known as heritage language schools in the US and complementary schools in the UK. CLSs offer a range of ethnic languages with the support of local community groups to supplement additional languages offered when the multiple needs of culturally and linguistically diverse students cannot be fully met in the mainstream school system (Baldauf, Citation2005; Liddicoat et al., Citation2007). For instance, in Australia, there are more than 1,400 community language schools, teaching about 70 different languages to more than 110,000 students (Australian Federation of Ethnic Schools Associations, Citation2022). They are significant educational language providers in Australia and worldwide (Nordstrom, Citation2022).

Given the nature of being non-profit and mainly funded by the immigrant community, CLSs face a range of challenges, such as lack of funding and increasing administrative demands (Thorpe et al., Citation2018); the needs of recruiting and enhancing the quality of teachers, who are usually volunteers from the community; engaging with parents and communities; competing with other school-related recreational activities (Baldauf, Citation2005; Cardona et al., Citation2008). Within such a constrained situation, CLS principals tend to be very proactive and innovative in seeking varied funding sources and in attracting students (Thorpe et al., Citation2018).

There has been emerging research on CLSs in the last 20 years (Nordstrom, Citation2022), mostly focusing on students’ language learning experiences, or the influence of school experience on students’ sense of identity (e.g., Nordstrom, Citation2022; Otcu, Citation2013; Otcu-Grillman, Citation2016), or school leaders’ views about students, teachers, and community, rather than on the leaders themselves (Arthur & Souza, Citation2020; Thorpe et al., Citation2018). Research on leadership in CLSs is limited but in dire need compared with the ample research on education leadership in mainstream schools (Day et al., Citation2009; Thorpe et al., Citation2018).

Some studies on Brazilian and Chinese language complementary school leadership in the UK revealed many school leaders had come from other professional backgrounds and entered the leadership positions on a voluntary basis, often due to a crisis or need at the school (Thorpe, Citation2011; Thorpe et al., Citation2018). As expected, these school leaders viewed their roles as problem solvers, who needed to find a way to connect with external organisations. Often, they did not feel fully prepared for their positions (Arthur & Souza, Citation2020; Thorpe et al., Citation2018). However, the existing literature does not elucidate the role of prior professional experience in CLS leadership in Australia. In addition, literature to date tends to focus on external factors, often of a negative nature impeding CLS leadership development. Little research has looked at individual leaders as the players and the qualities they possess.

It appears that there is a need to better understand the specific context of leadership practice in complementary schools, and more empirical evidence is required to provide deeper insights into leadership practices in distinctive and challenging circumstances (Thorpe et al., Citation2018, Citation2020). Research on leadership in non-profit organisations revealed that the ability for non-profit/voluntary sector to raise funds has become part of social entrepreneurial activities, which is a new skill set in educational entrepreneurship (Melnikova, Citation2020). It appears there is a need to explore the contributory role of entrepreneurship to education (Borasi & Finnigan, Citation2010). The research questions this paper aims to explore are:

What kind of entrepreneurial traits did the CLS principals display?

How did the CLS school principals’ prior experiences display in their entrepreneurial traits or practices?

3. Conceptual framework—educational entrepreneurship

The concept of “entrepreneur” has been regarded as “a driving force of change and innovation, introducing opportunities to achieve efficient and effective performance in both public and private sectors” (Yemini, Citation2018, p. 398). In the field of education, entrepreneurship faces a resistance from educators towards its economics orientation which has traditionally not been regarded as the core responsibility of the teacher and schools (Haara & Jenssen, Citation2016; Yemini, Citation2018). However, even public-school enterprises are increasingly expected to display business characteristics, particularly in a time when government funding is shrinking with an increasingly external expectation for the education sector to seek alternative funding sources (Hentschke, Citation2009). This calls for more entrepreneurial practice and innovative approaches at the professional and leadership levels (Yemini, Citation2018).

3.1. Definition and characteristics of educational entrepreneurship

Regarding education entrepreneurship, there has not been a consensus in definition. Smith and Peterson’s (Citation2006) early work viewed educational entrepreneur as “visionary thinkers who create new for-profit or non-profit organizations from scratch that redefine our sense of what is possible” (p. 21). Borasi and Finnigan’s (Citation2010) definition focused on educational entrepreneurs’ competency to enact ideas and create value. Some researchers emphasised the educational entrepreneurs’ innovative ideas and ability to enact changes in public education (Leffler, Citation2009; Teske & Williamson, Citation2006). Apart from business skills, entrepreneurial capacity also includes a range of soft skills such as the ability to collaborate, improvise, initiate, and the like (Campbell, Citation2019). The common themes were making changes, taking initiatives, vision-driven, innovation and value creation. Some systematic reviews summarised the key characteristics/traits of educational entrepreneurship, as listed in (Ho et al., Citation2021; Smith & Peterson, Citation2006), namely innovative, opportunity oriented, resourceful, able to create value and foster change.

Table 1. A summary of some key traits of educational entrepreneurship

As shown in , there are some overlaps among the findings about educational entrepreneurial traits revealed by these studies. Using these findings as a point of departure, this paper synthesises the nine identified education entrepreneurship traits as an analytical checklist (see, ).

Table 2. A checklist of education entrepreneurship traits

The reviewed studies highlighted a need for further research in two related strands. First, existing studies on educational entrepreneurship focused mostly on mainstream schools (as shown in ). So far, there is only one research project focused on the entrepreneurial traits of leaders in complementary educational environments in Lithuania (Melnikova, Citation2020). The CLSs in Australia could be categorised as one type of social entrepreneurial organisation as its role is to maintain the ethnic language and culture for the community and to supplement the languages curriculum in mainstream schools (Melnikova, Citation2020; Smith & Peterson, Citation2006). Many CLS principals’ initiatives and practices in establishing the school could enrich entrepreneurship education models especially the traits and competency they have demonstrated and the interaction with the specific context (Thomassen et al., Citation2019).

Second, although a few studies recognized the role of prior experience in school leaders (Ho et al., Citation2021; Oplatka, Citation2014; Schimmel, Citation2016), there was no elucidation about how these prior experiences may impact the individual’s entrepreneurial practice. At the same time, some emerging approaches to entrepreneurship education have shifted from a skill-based to an experiential-based model focusing on the dynamic interaction between the individual’s past experience, and present and future actions (P. B. Robinson & Gough, Citation2020; P. Robinson & Josien, Citation2014). This is an area that calls for further exploration, considering that most CLS leaders stepped in with various professional and cultural backgrounds. The present paper adopted this dynamic paradigm in exploring the entrepreneurial traits demonstrated by CLS principals, as well as considering the role of their prior experience and learning gained from different professional fields. This will provide empirical evidence for experiential-based entrepreneurship education.

It is not the intention of this paper to add another layer to the definition of educational entrepreneurship, but to explore the features and practices of the educational entrepreneurship of CLS principals in the Australian context. Hopefully the empirical evidence will enrich our understanding of this concept as the field is largely informed by findings gathered in studies conducted in other contexts.

4. Methodology

In addition to the quantitative studies of entrepreneurship with large samples, there is a need to understand entrepreneurship by analysing the context of entrepreneurial behaviour via qualitative case studies (Dana & Dana, Citation2005). The current study followed a multiple case study design that was useful in interrogating the experiences and practices of ethnically diverse principals in displaying their educational entrepreneurship (notably their commonalities and differences; Yin, Citation2009). The study participants were three CLS principals with immigrant background, who had taken initiatives to establish their respective CLS. The study has obtained ethics approval from the university the researchers are affiliated with. The data was collected in 2019 by two instruments: reflective journals and individual interviews. The structured reflective journals were used to guide the participants to reflect on a significant moment or event during their experience of teaching at a CLS, their responses to, and reflections on, that experience, and the supports as needed. After that, there was an individual 50-minute semi-structured interview, which was conducted to capture identifiable traits of educational entrepreneurship. As a follow-up of the reflective journals, the interview covered a range of aspects related broadly to their experience of establishing and running the CLS. These aspects included their background, their motivation to establish the CLS, the process of establishing the school, the difficulties they encountered, strategies they used to cope with these challenges, the nature of the local community, their beliefs and practice of language teaching, financial and curricular resources, and plans for future school development. Their background and their CLSs were listed in .

Table 3. Participants information

Richard has had an engineering background and migrated to Australia 20 years ago. On weekdays, Richard has been a full-time professional staff in an Australian university. As for Liz, in addition to taking the role of school leader and teacher at her CLS, she has been running her own business during the weekdays. Mandy established a Chinese language school in a small town near the NSW/Victoria border. It takes eight hours driving to Sydney. Mandy had a bachelor’s degree in law and received a high school teacher qualification in China. After she immigrated to Australia, she took a customer service job in a local fund management company. After that she became a full-time mother for four children for eight years with only some casual Chinese language private tutoring experience. Recently she combined her school with another language school and shifted her attention from business to teaching.

During interviews, none of the participants saw themselves as being entrepreneurial. However, the analysis of their responses indicated they displayed observable entrepreneurial traits, which have been documented in research conducted in other contexts (Borasi & Finnigan, Citation2010; Ho et al., Citation2021; Melnikova, Citation2020; Schimmel, Citation2016; Xaba & Malindi, Citation2010).

NVivo was used to cluster and code the qualitative data in three rounds. The first round of analysis involved a deductive coding strategy to analyse the reflective journals and interview transcripts according to the educational entrepreneurship traits listed in . The number of each coded trait was recorded for each case. Examples of analysis are shown in :

Table 4. Coding examples

The second round of analysis focused on a cross-case analysis, when two themes emerged in relation to both the process of venturing and establishing the schools, and the process of running the school including the strategies they used to secure resources. The two themes arising from the analysis were enterprising and venturing, and resourceful and strategic. The frequency of each of the displayed traits being displayed was calculated and analysed in a spreadsheet based on the frequency of the analysis for each trait. In the third round, the most salient traits of each of the participants were further analysed in combination in a matrix for potential patterns of the combination of traits. The three rounds of analysis were carefully checked and discussed by both authors.

After three rounds of analysis, two colleagues outside of the research team were invited to check the coding independently, applying the coding scheme (Table ). The inter-coder agreement percentage was within the range of 91%–93% which was regarded as acceptable (O’Connor & Joffe, Citation2020).

5. Results

The results from the three cases studies were arranged in accord with the two emerged themes: enterprising and venturing, and resourceful and strategic. In addition to presenting the displayed entrepreneurial traits in combination, the data also highlighted how their prior experiences informed their current entrepreneurial practice.

6. Theme 1 enterprising and venturing

All three participants demonstrated their visions for establishing their CLSs and exercised their exploitation of perceived opportunities and responding to a need in the community. Each participant exhibited these traits in an integrated way.

6.1. Richard

Richard has been passionate in teaching the Malayalam language through social engagement with the local community. He exhibited multiple entrepreneurial traits, such as being visionary, proactive and innovative in combination, in responding to the challenges encountered during the process of establishing and running the school. Richard wanted to establish the school because of his recognition of lack of provision of this classical language in the community.

… Malayalam is one of the classical languages … I’d talked to a lot of community youngsters, and they all said that they didn’t get a chance to learn the language because there was no provision.

The initiative of communicating with youngsters in the community indicated his pre-emptive response to the perceived need via social connections. This underpinned his goal and motivation to establish a school. At the same time, Richard mentioned that other Malayalam CLSs established at the same time, failed. He analysed that the reason why his school was successful was because they surveyed prospective students and parents to establish their preferences for the class time at the CLS, that helped him build a rapport with the potential student/parent group:

We did a survey among the community about what’s a suitable time for them to attend the CLS. Most of them were happy with our timetable arrangement. Other Malayalam CLSs failed due to lack of rapport and proper communication with parents.

The needs analysis survey was a combination of active and creative strategies to secure the human resources (students’ enrolment) for his school. Through this communication with parents, he understood the parents’ perceptions of CLSs: “CLS is not their first option.” This understanding also helped him to create one strategy for engaging parents in running the school:

We invite our parents to join the management committee … Other Malayalam CLSs had failed because they didn’t involve the parents.

This practice demonstrated his ability to secure resources from the community, which has been a salient feature in the process of running his school. This was not a new practice for most community language schools, but he applied some creative strategies such as surveying parents’ preferences, which could be viewed as innovative for improving the practice in his context.

6.2. Liz

By the time of interview, Liz’s CLS had been established for two years with around 20 students. She demonstrated the traits of being visionary and exploiting opportunities to establish her school. Her motivation to start the school arose from her experience of attending a conference of overseas Chinese:

The chairman compared the overseas Chinese as homecoming after marriage. The host country is like your new home, so you need to contribute to them and integrate your culture with theirs.

This analogy raised her awareness about her responsibility as an immigrant in Australia, which was to integrate with Australian society. This was the broader vision for her. Later, when she visited her child’s school, an idea occurred to her that a CLS could be an option to achieve such integration.

When I entered my son’s school, I saw a diversity of cultures, Christianity, Hinduism, and Italians, but Chinese language and cultural studies is not part of the curriculum at that school. I think there was a gap.

Her awareness of the gaps in the public school’s curriculum motivated her to establish a CLS. This indicated her ability to see the opportunity in the target market and to take requisite action.

After setting the goal, she innovatively responded to various challenges in establishing the school, engaging in risk-taking along the way. During the process of application to establish the CLSs via the Department of Education (DoE) website, she encountered many obstacles due to her lack of knowledge of the Australian regulatory context. For example, at the point of registration, not knowing the difference between Fair Trading and business registration, she made an error in registering a commercial school and incurred a significant financial loss. The problem of online application and registration was eventually resolved with the help from a staff from the DoE. As a result of the challenges, she experienced during the application process, Liz took action to develop a user guide in Chinese including the procedures of applying for a CLS and shared this with other applicants. This idea was innovative in that it helped improve existing practices by capitalizing on her strong problem-solving skills.

6.3. Mandy

The prominent entrepreneurial trait that Mandy displayed during the process of establishing the CLS was driven by her vision, risk-taking, and actions in creating opportunities. She was sensitive to the need for Chinese learning in the small town where she lived.

Establishing the Chinese language school meets the current demands, because I do see the increasing need for Chinese language learning.

Her awareness of the need was formed from her observations and conversations with other parents in her children’s school. She noticed that even parents without Chinese language background expressed interest in their children learning the Chinese language. Although she had the option to go back to the fund management company she had worked for, she chose to take a risk:

To me, the previous customer service position was comfortable, but I feel I am passionate about teaching Chinese. With my previous background and experiences, I feel that I can be further challenged.

This was the sign of risk-taking and need for achievement. In addition, Mandy was strategic in exploiting an opportunity for setting up the CLS, as reflected in her repeated use of the expression “generate opportunity” in the interview: “I am trying to figure out a way out by myself. All my opportunities are self-generated.” Every step was built on her previous successful experience. First, her experiences of being trained as a high school teacher in China equipped her with some general pedagogical knowledge. In addition, Mandy had some language tutoring experience in a local Australian company for training overseas staff. After that, she extended the language teaching to her children’s primary school:

I am more selective about students … I offered some interest class for free in that primary school, for just five or six weeks, and they loved it and wanted to continue learning with me.

This was the first group of students she recruited for her Chinese language school. She also posted some advertisements on social media. She emphasised:

These experiences, one by one, have been guiding me in one direction, towards establishing the school.

Slightly different from the other two cases, the influence of Mandy’s prior experience was in a strategically planned and progressive way. Prior overseas training and different tutoring jobs all prepared her for establishing the school.

7. Theme 2 resourceful and strategic

7.1. Richard

When running the CLS, Richard adopted the strategies in securing resources by involving parents and using cultural activities to creation collaboration with the local community, which accumulated into his current entrepreneurial experiences and strategies.

The constraints on Richard’s CLS were in respect of personnel and administration. As teachers at CLSs usually were voluntary, this caused the problem of inadequate numbers of administrative staff and limited time for staff meetings. Richard’s strategy was to engage parents to do the administrative work at the CLS:

We explain about this rule on the Open Day, “If you are willing to spend two hours a week here …, then you send the kids … so everyone is involved.” We are strict with that rule. It works.

This was one strategy to use human resources from the local community rather than being constrained by limited resources. The making of the rule could be viewed as a way of legitimising their practice to select parents who are willing to contribute to the school. Richard confirmed the effective outcome of this rule:

We have that harmony and bonding. Many staff have been working here nine years … It’s like a family.

The staff’s commitment was essential for the enterprise, especially on a voluntary base. The engagement of parents helped establish a culture of participation and harmony. The strategy was much informed by his prior successes in building rapport with parents at the initial stage of establishing a school.

Another prominent feature of Richard being resourceful was to use culturally related activities to engage students and enhance the bonding:

Every year we have our annual cultural day for celebrating the Indian festivals to build a connection with our culture. We taught our students the significance and traditions of these festivals and helped them tell story in Malayalam.

They also invited parents to share traditional Indian food to enhance “the feeling of oneness.” This was a culturally responsive strategy they applied to enhance the connection with parents. In addition, they also made good use of local community resources, such as guest speakers to talk with students, which was regarded as a very engaging activity by students.

Richard’s school also participated in an SBS radio program for promoting their language: “Our kids were happy when they visited SBS studio. They were proud of what they were doing.” This strategy helped the school extend and create a strong impact on a wider audience. The acknowledgement of parents’ contributions in the radio program was a motivating strategy in addition to confirming the rule-setting. Although Richard did not regard himself as an entrepreneur, he displayed some entrepreneurial traits, which were largely derived from, or built upon, his accumulated experiences of establishing and running the CLS.

7.2. Liz

In her reflective journal, Liz recorded that the challenges in running her school were in leasing classrooms, the delay of government subsidy and her own health issue. However, she showed strong risk-taking and committed effort in securing resources. She recalled one difficult situation:

The school deputy principal called me in the morning telling me that they won’t allow us to use the classroom in the afternoon. I spent one hour thinking of ways to resolve the problem … I called him back to negotiate, and they eventually allowed us to use the classroom that day. The next day, we renewed the rental contract.

In that urgent situation, Liz showed her problem-solving skill by communicating with the host school with persistent effort. Although she had been funding the weekly rent by herself till the time of the interview, her persistence was because she had a future vision for this school:

We want the school to continue. In the future, even if the kids have graduated, when new parents come into the school, we could handover this to them.

This reflected a sustainable view of the future development of the school, even though it lacked detailed planning. This vision may sustain her to accept the temporary financial loss.

Liz’s school encountered the issue of the shortage of qualified teachers. To cope with this issue, she devised strategies to seek opportunities and resources for teacher training. Although the school hired two teachers from other CLSs, they were not always available, and Liz had to share the teaching load. Therefore, she emphasized the importance of teacher training. She recollected the process wherein she sought a quota for the CLS teacher professional development course:

They only gave the quota for teachers, but not leaders of the school. I told them, “All the teachers are hired from outside, so if you teach me, I could teach them.” They eventually managed to give me a quota.

She showed a strong desire and capacity to secure the learning opportunity, the purpose being to ensure the quality of teaching. This was different from other education leadership in mainstream schools where teachers usually had a background in teaching. Liz immediately implemented the new learning in classroom practice:

I followed the methods that the training teacher taught us, conducting the lesson through game-based learning. The children really liked this approach.

Liz attributed the successful attempt to her prior experience of doing business: “Because I used to be a business-person, I have always been a more hands-on and proactive person.”

Meanwhile, she found that not all teachers made the change, and she described the observation of another Chinese language teacher’s teaching practice in her school:

Some Chinese teachers continued the old Chinese way of teaching, very teacher-centred [teaching]. I think the teacher must follow-through and adopt the new teaching method after receiving the training.

She regularly observed other teacher’s teaching to ensure that they used the new teaching approaches from the training, showing her intention to ensure the teaching quality at her school. Moreover, in the interview, Liz made comparison between the “Australian way” of teaching (game-based and student-centre teaching approaches) with the “Chinese way” (teacher-centred approach) and showed her preferences for the “Australian way”. On the one hand it indicated her lack of professional language to name the teaching methods. On the other hand, this reflected her desire to achieve integration with the host country. Liz’s prior experience in running her own business provided a solid base for her current practice at the CLS, and in the process she displayed a range of entrepreneurial traits such as problem-solving skills, risk-taking, dedicated application and persistence.

7.3. Mandy

In her reflective journal, Mandy expressed her anxiety to cater for different students’ learning needs and expressed a degree of urgency for professional development in leadership and teacher training.

During the process of running the school, Mandy displayed entrepreneurial traits like securing resources, being active and establishing collaboration. Mandy said that “I feel very lonely as there are not many people and resources for Chinese education here.” However, she demonstrated a strong ability in recruiting students and looking for teaching resources. In addition to attracting students from the free interest class and her advertisements on social media, another way of recruitment was “just word of mouth” via interacting with people, a skill she developed on the job as a customer service officer in the past. As a mother for four children, she built connections with some families who were doing home-schooling and wanted to learn the Chinese language. She also attracted students recommended by her friends. She started her school after recruiting 15 students and it grew to 22 students.

Responding to the lack of teaching resources, in addition to spending her own money purchasing Chinese language textbooks, she also sought support from external associations and organisations:

I contacted the Australian Chinese Language Schools Association and the Chinese embassy, and they both provided me with some materials. I looked for such chances bit by bit.

The last line in her response indicated her dedication in seeking and securing resources. She expressed strong motivation and an interest in undertaking training for language teaching and was willing to drive for eight hours from her provincial town to participate in the CLS teacher training courses in Sydney, aligning with the needs she expressed in her reflective journal. She also contacted other CLSs in Sydney and Melbourne to share experiences and information.

Based on her awareness of the constraints in her situation, after having established her school, Mandy decided to collaborate with a local independent primary school to offer her school as the provider of the Chinese language program in that school: “Since there was a chance to work with the school, I thought it would be good to learn some experiences about running the school from them, so I collaborated with them.” After that, the collaborating school took over the student recruitment and Mandy focused more on teaching. This decision showed her ability to collaborate with others to ease the pressure of recruitment and come up with a mutually beneficial outcome.

8. Discussion

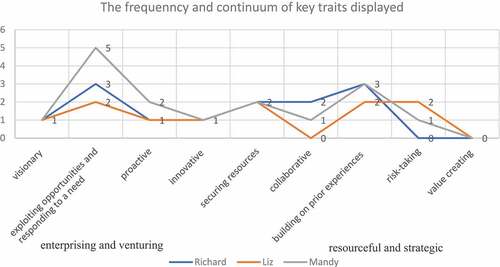

The thematic analysis highlighted two traits, enterprising and venturing, and resourceful and strategic with various traits in combination. This extended frequency and continuum model () is a summary of the findings of this study in terms of the entrepreneurial traits as shown by the principals; it also illustrates implicitly the process whereby these traits worked in combination to enable the successful establishing of the CLS; as well, the role and interrelation of their prior learning, professional experience, and their current practice in setting up a school. This may not be viewed simply as a linear cause-and- effect outcome, but a more dynamic and complex process with a lot of trial-and-error attempts.

8.1. Display of traits in combination

Differing from other studies focused on individual educational entrepreneurial traits (Eyal & Inbar, Citation2003; Omer Attali & Yemini, Citation2017), this study revealed some patterns in terms of the combination of traits, more reflective of individual context and choices. As for enterprising and venturing, the common combination included visionary, exploiting opportunities, and responding to a need, risk-taking, and proactivity.

Although none of the participants used the word “vision”, they were driven by their initial goal for setting up their CLS, to maintain and promote their community language and culture. Similar to the findings in the Borasi and Finnigan (Citation2010) study, the three participants were persistent in pursuing their goals regardless of any obstacles and were successful in convincing others about the wisdom of their vision. However, they did not have a clear articulation about future development of their schools, except Liz who had some ideas about engaging parents in school management. This indicates the need for future study to re-examine the notion of vision for educational entrepreneurship (Omer Attali & Yemini, Citation2017).

The ability to exploit opportunity and respond to a need was another salient trait displayed by the three principals, all being rated as core features of educational entrepreneurship (Ho et al., Citation2021). This differs from other researcher’s findings insofar as participants took the school leadership role to cope with a crisis at their schools (Thorpe et al., Citation2018), and some ethnic entrepreneurs took self-employed business due to a lack of competitiveness (Verver et al., Citation2019). The three participants in this research took initiatives to establish their schools based on a strong community demand and their passion, which played an important role in motivating them to be active and take risks to establish the school regardless of the constraints in their situation (Keyhani & Kim, Citation2020). This was reflected in Mandy’s strategic way of seeking and exploiting opportunities, whereas Richard and Liz seemed to seize opportunities by “gut instincts”, which might have been the result of a holistic evaluation of the situation (Borasi & Finnigan, Citation2010, p. 18). This indicates a need for developing a systematic way of evaluating opportunities and risks (Ho et al., Citation2021; P. Robinson & Josien, Citation2014).

Another pattern of traits in combination were the securing of resources, dedication, risk-taking, collaboration and innovation. These traits worked together to deal with the various challenges these CLSs encountered in this study, including lack of adequate teaching resources, difficulties in recruiting students, struggles to secure school venues, thus confirming the challenges revealed by other studies (Arthur & Souza, Citation2020; Thorpe et al., Citation2018). The principals presented themselves as being innovative in their specific school contexts. Richard’s innovation included the survey for parents’ timetable preferences, the rule for parents to commit to undertaking administrative work and incorporating cultural activity as strategies for maximising the use of human resources. Mandy used a combination of strategies for recruiting students and seeking teaching resources by building connections with external organisation and parents. Their strategies were similar to those adopted by other school leaders and teachers who did not have access to an ongoing budget but looked for resources from networking, fund raising, volunteers from the community and cultural resources (Verver et al., Citation2019; Borasi & Finnigan, Citation2010; Ho et al., Citation2020; Thorpe et al., Citation2018). Although these combinations of traits and actions were only small initiatives to address some context-specific issues (Borasi & Finnigan, Citation2010), they were also innovative ways of combining resources on a small scale (Eyal & Inbar, Citation2003; Ho et al., Citation2020).

The findings highlighted two areas that call for future research and CLS teaching training. One is the collaboration with other schools and the local community to deal with the lack of resources that Richard and Mandy suffered in their practice. As revealed in other studies, collaboration is an effective strategy to help enrich the availability and use of pedagogical resources (Arthur & Souza, Citation2020; Eyal & Inbar, Citation2003), and should be included in the literature on educational entrepreneurship (Ho et al., Citation2021). Another type of resource that Liz and Mandy both sought was training opportunities, which is in accordance with the finding that leaders without teaching qualifications viewed pedagogical development as of vital importance for leadership development (Thorpe et al., Citation2018).

9. Impact of prior experience

Regarding the second research question, one context-specific trait to note is the impact of the participants’ prior experiences on their current entrepreneurial activities related to the set-up of the CLS, as they often fall back to what they had experienced in a past activity (Oplatka , Citation2014). Richard used the survey approach a couple of times due to the initial success. Liz’s risk-taking, commitment, persistence, and supervision of other teachers were influenced by her prior experience of running her own business and hands-on style. For Mandy, it was a gradual process to build every step based on the previous success, such as moving from adult language training to children, moving from private tutoring to establishing a school. Although some research recognized the role of prior experience in entrepreneurial traits (Ho et al., Citation2021; Oplatka , Citation2014; Schimmel, Citation2016), this study offered additional empirical data arguing that the principals’ prior experience together with other entrepreneurial attributes influenced their decision making and actions in a new cultural context. This is much in line with the findings from a recent study of CLS teachers that their prior experiences need to be recognized and capitalised upon as resources for current practice via reflection, selection and incorporation (Yang & Shen, Citation2021). Future research with a larger sample of participants is needed to validate this trait.

9.1. Areas that need further training

Although all three principals have the vision and passion to promote and maintain their target language and culture, none of them explicitly talked in detail about value creation. This confirms the findings from other research that the term value, especially social value, should be highlighted in the current discourse on educational entrepreneurship (Ho et al., Citation2021; Melnikova, Citation2020; Omer Attali & Yemini, Citation2017). Although it is argued that education entrepreneurs should “add more value to their organisations and to the clients they serve” (Borasi & Finnigan, Citation2010, p. 2), the training for CLS leaders may need to raise their awareness about the importance of this aspect and explore this area in their practice.

10. Implications, conclusions and limitations

Based on the findings, this paper draws some implications for training for both educational entrepreneurship and CLS leadership programs. Although the three participants exhibited entrepreneurial traits, these traits were displayed without their conscious awareness. All of them responded to the challenging situations as they arose and acted intuitively to overcome the difficulty or seek a way out. This highlights a need to incorporate the explicit teaching of entrepreneurial concepts and skills to teachers or education leaders so that they can respond to a challenge in an entrepreneurial way. It could be started from awareness-raising via introducing the broader concept of entrepreneurship to education (Borasi & Finnigan, Citation2010). Teachers and leaders could then explicitly state their beliefs and compare theirs with the new content provided by the training course via reflection and modification (Borasi & Finnigan, Citation2010; Ho et al., Citation2020).

In addition to explicit teaching, a problem-based or inquiry-based approach to curriculum design and classroom instruction for entrepreneurial attitude and skills will afford opportunities for more engaged and interactive learning, and be more appropriate for the context, in which school leaders and teachers operate. Teachers and leaders could first identify and analyse the challenges in their contexts and then explore the entrepreneurial skills and traits informed by the research as a possible resolution for them (P. Robinson & Josien, Citation2014).

This study highlighted that participants’ prior experience also played an important role in their decision making and entrepreneurial practice. The interplay of prior experience and new knowledge was a helpful process in which participants engaged in comparison, reflection, evaluation and strategic planning to make an informed decision. It appears that an educator’s prior professional experience could be a useful resource to be capitalized on, especially in a multilingual or multicultural context. This poses an important implication for curriculum design to focus more on experiential learning and real-life project-based learning, which is gaining strong momentum in entrepreneurial education (Hägg & Gabrielsson, Citation2019). Yet a much larger data set is needed to warrant a broader generalisation of this implication.

In addition, this study yielded more context-specific evidence to supplement research of major characteristics of the entrepreneurial practice in complementary schools (Eyal & Inbar, Citation2003; Melnikova, Citation2020). There is a call for more research on how education leaders deal with the challenges at cross-cultural levels (Arthur & Souza, Citation2020). It would be worthwhile to further explore the educational entrepreneurial practice from a culturally responsive perspective in different contexts and develop a context or culturally sensitive entrepreneurial pedagogy (Thomassen et al., Citation2019).

One limitation of the study was that the findings from the small sample and self-reported data does not warrant the generalisability to a wider context, but the in-depth study of three CLS leaders has allowed an informative capture of some typical entrepreneurial traits these participants demonstrated in the context of CLSs, and how these traits and skills worked together when they dealt with the numerous challenges encountered. One future research area will be to conduct more empirical case studies in different contexts with multiple data sources to develop a data base of educational entrepreneurial skills and practice and develop a broad framework to inform design and teaching of entrepreneurial skills.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arthur, L., & Souza, A. (2020). All for one and one for all? Leadership approaches in complementary schools. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220971285

- Australian Federation of Ethnic Schools Associations. 2022 Community Languages Australia . . https://www.communitylanguagesaustralia.org.au/

- Baldauf, R. B. (2005). Coordinating government and community support for community language teaching in Australia: Overview with special attention to New South Wales. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 8(2–3), 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050508668602

- Borasi, R., & Finnigan, K. (2010). Entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviors that can help prepare successful change-agents in education. The New Educator, 6(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1547688X.2010.10399586

- Campbell, M. (2019). From youth engagement to creative industries incubators: Models of working with youth in community arts settings. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 41(3), 164–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2019.1685854

- Cardona, B., Noble, G., & Biase, B. D. (2008). Community languages matter! Challenges and opportunities facing the community languages program in New South Wales. University of Western Sydney.

- Dana, L. P., & Dana, T. E. (2005). Expanding the scope of methodologies used in entrepreneurship research. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 2(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2005.006071

- Day, C., Sammons, P., Hopkins, D., Harris, A., Ken Leithwood, K., Gu, Q., Brown, E., Ahtaridou, E., & Kington, A. (2009). The impact of school leadership on pupil outcomes. Department for Children, Schools and Families.

- Eyal, O., & Inbar, D. E. (2003). Developing a public school entrepreneurship inventory: Theoretical conceptualisation and empirical examination. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 9(6), 221–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550310501356

- Haara, F. O., & Jenssen, E. S. (2016). Pedagogical entrepreneurship in teacher education–what and why? Tímarit Um Uppeldi Og menntun/Icelandic Journal of Education, 25(2), 183–196 https://ojs.hi.is/tuuom/article/view/2434.

- Hägg, G., & Gabrielsson, J. (2019). A systematic literature review of the evolution of pedagogy in entrepreneurial education research. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(5), 829–861. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-04-2018-0272

- Hentschke, G. C. (2009). Entrepreneurial leadership. In B. Davies (Ed.), The essentials of school leadership (pp. 147–165). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Ho, C. S. M., Lu, J., & Bryant, D. A. (2020). The impact of teacher entrepreneurial behaviour: A timely investigation of an emerging phenomenon. Journal of Educational Administration, 58(6), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-08-2019-0140

- Ho, C. S. M., Lu, J., & Bryant, D. A. (2021). Understanding teacher entrepreneurial behavior in schools: Conceptualization and empirical investigation. Journal of Educational Change, 22(4), 535–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09406-y

- Keyhani, N., & Kim, M. S. (2020). A systematic literature review of teacher entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 4(3), 376–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127420917355

- Leffler, E. (2009). The many faces of entrepreneurship: A discursive battle for the school arena. European Educational Research Journal, 8(1), 104–116. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2009.8.1.104

- Liddicoat, A., Scarino, A., Curnow, T., Kohler, M., Scrimgeour, A., & Morgan, A. M. (2007). An investigation of the state and nature of languages in Australian schools. DEEWR.

- Mau A, Francis B and Archer L. (2009). Mapping politics and pedagogy: understanding the population and practices of Chinese complementary schools in England. Ethnography and Education, 4(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457820802703473

- Melnikova, J. (2020). Leading complementary schools as non-profit social entrepreneurship: Cases from Lithuania. Management in Education, 34(4), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020620945331

- Nordstrom, J. (2022). Students’ reasons for community language schooling: Links to a heritage or capital for the future? International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(2), 389–400 https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1688248.

- O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. 1609406919899220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

- Omer Attali, M., & Yemini, M. (2017). Initiating consensus: Stakeholders define entrepreneurship in education. Educational Review, 69(2), 140–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2016.1153457

- Oplatka, I. . (2014). Understanding teacher entrepreneurship in the globalized society: Some lessons from self-starter Israeli school teachers in road safety education. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 8(1), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-06-2013-0016

- Otcu, B. (2013). Turkishness in New York: Languages, ideologies and identities in a community-based school. In O. García, Z. Zakharia, & B. Otcu (Eds.), Bilingual community education and multilingualism: Beyond heritage languages in a global city (pp. 113–127). Multilingual Matters.

- Otcu-Grillman, B. (2016). “Speak Turkish!” or not? Language choices, identities and relationship building within New York’s Turkish community. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2016(237), 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2015-0040

- Robinson, P., & Josien, L. (2014). Entrepreneurial education: Using” The Challenge” in theory and practice. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 17(2), 172–185 https://www.proquest.com/docview/1647670064?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true.

- Robinson, P. B., & Gough, V. (2020). The right stuff: Defining and influencing the entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 23(2), 1–16 https://www.proquest.com/docview/2424960750?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true.

- Schimmel, I. (2016). Entrepreneurial educators: A narrative study examining entrepreneurial educators in launching innovative practices for K-12 schools. Contemporary Issues in Education Research (CIER), 9(2), 53–58. https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v9i2.9615

- Smith, K., & Peterson, J. L. (2006). What is educational entrepreneurship? In F. Hess (Ed.), Educational entrepreneurship: Realities, challenges, possibilities (pp. 21–44). Harvard Education Press.

- Teske, P., & Williamson, A. (2006). Entrepreneurs at work. In F. Hess (Ed.), Educational entrepreneurship: Realities, challenges, possibilities (pp. 45–62). Harvard Education Press.

- Thomassen, M. L., Middleton, K. W., Ramsgaard, M. B., Neergaard, H., & Warren, L. (2019). Conceptualizing context in entrepreneurship education: A literature review. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 26(5), 863–886. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-04-2018-0258

- Thorpe, A. (2011 September). Leading and managing Chinese complementary schools in England: Leaders’ perceptions of school leadership British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, London (Digital or Visual Products, British Education Index)http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/204556.pdf .

- Thorpe, A., Arthur, L., & Souza, A. (2018). Leadership succession as an aspect of organisational sustainability in complementary schools in England. Leading and Managing, 24(2), 61–73 https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.217023921060842.

- Thorpe, A., Arthur, L., & Souza, A. (2020). Leadership in non-mainstream education: The case of complementary and supplementary schools. Management in Education, 34(4), 129–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020620945334

- Verver, M., Passenier, D., & Roessingh, C. (2019). Contextualising ethnic minority entrepreneurship beyond the west: Insights from Belize and Cambodia. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(5), 955–973. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-03-2019-0190

- Xaba, M., & Malindi, M. (2010). Entrepreneurial orientation and practice: Three case examples of historically disadvantaged primary schools. South African Journal of Education, 30(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v30n1a316

- Yang H and Shen H. (2021). Community languages school teachers’ pedagogical habitus in transition: an Australian perspective. International Multilingual Research Journal, 15(4), 346–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2021.1911191

- Yemini, M. (2018). Conceptualizing the role of nonprofit intermediaries in pursuing entrepreneurship within schools in Israel. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(6), 980–996. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217720458

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (Vol. 5). Sage.