Abstract

This study aims to explore the influence of science teachers’ beliefs on an educational assessment reform adopted in Estonia. Two existing questionnaires were adapted to develop a model to examine teachers’ beliefs about teaching and assessment and administered to a sample of Estonian science teachers (N = 319). The outcomes were examined through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modelling (SEM). This produced two dominant beliefs in relation to teaching named “teacher-centred” and “student-centred”, plus indicating four purposes for assessment, namely: “teaching improvement”, “irrelevance”, “examination”, and “school and teacher accountability”. Findings indicate most Estonian science teachers express beliefs aligned with student-centred approaches and predict positively teaching improvement purposes for assessment as perceived by teachers, both of which seem to support the implementation of a student-centred reform in the country. However, at the same time, the relatively high rating of teacher-centred beliefs and high valuation of assessment for examination purposes seem to counteract the intended reform.

1. Introduction

Policy reforms in education strongly promote a constructivist approach to teaching and assessment (Fives et al., Citation2015; Windschitl, Citation2002). In line with such global education trends, external assessment is being promoted so as to improve teaching and learning, referring to this as “assessment for learning” rather than “assessment of learning” (Assessment Reform Group, Citation1999; OECD, Citation2013). In Estonia, the education reform and corresponding curriculum changes are intended to facilitate more student-centred (formative) approaches (Estonian Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2014). Aligned with these changes, an external, electronic assessment tool in science, named e-testing, was developed (Pedaste, Citation2018).

The science e-test is based on the assumption that science teachers can appreciated its formative nature. An essential novel component is automatic descriptive feedback on the students’ results that the teachers can use in the future to improve their teaching and enhance student learning. Though administered externally, the focus of the e-assessment is not to produce grades, or top lists or make teachers and students highly accountable for their work, which can be expected to be accompanied by increased anxiety as found in undertaking external assessment (Pellegrino, Citation2014). Rather it is to provide teachers and students with feedback on the students’ level of learning related to science competences and, at the same time, indicating the subsequent teaching and learning level to target. This second feature is intended to support students to pose their own learning goals. Based on the e-test feedback, teachers are expected to refocus their instruction according to identified students’ learning needs.

The Estonian science e-assessment undertaking takes place at the beginning of the semester (in autumn), and thus differs from the traditional paper-and-pencil summative assessment (e.g., exam), which usually takes place at the end of a semester. Furthermore, E-assessment allows inclusion of different media-rich stimuli material (whether graphical, sound, video, or animation), simulations, etc., as opposed to paper-and-pencil tests (Boyle & Hutchison, Citation2009; Ridgway et al., Citation2004). As a form of external assessment, e-testing is expected to produce a more valid and reliable evaluations of competences acquired by students compared with internal (teacher-based) assessment (Vitello & Williamson, Citation2017).

In line with the adoption of the reform, the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research has proposed to abolish the earlier centralized, final examinations system for basic schools (9 th grade) and replace this with national e-tests (Vahtla, Citation2019). However, this plan has led to strong opposition by teachers (including science teachers) and to a joint petition supporting the continuation of the earlier basic school examinations (Wright, Citation2019). This reaction from teachers is seen as somewhat surprising, because since 2011, the Estonian curriculum has focused on a more student-centred approach towards teaching. However, on the other hand, Estonian teachers have much experience in, and perhaps affinity with, preparing their students for external examinations, starting from the mid-1990s (Lees, Citation2016) and the average age of Estonian teachers is higher than elsewhere in Europe (OECD, Citation2019). According to Bandura (Citation1986) and Pajares (Citation1992) , longitudinal practices can leave a strong imprint on teacher beliefs, e.g., that final external examinations are believed to be an essential part of learning and teaching.

Belief is a psychological construct through which one interprets reality (Pajares, Citation1992; Rokeach, Citation1968), which may simultaneously consist of logical, cognitive, emotional, and affective components (Fives & Buehl, Citation2012). Research has shown that teacher beliefs play a significant role in the interpretation and implementation of pedagogical reforms (ibid) and may hinder the adoption of new approaches to teaching and assessment (Brown & Gao, Citation2015; Chen & Brown, Citation2016). Some authors (Duffee & Aikenhead, Citation1992; Tobin & McRobbie, Citation1996) have even suggested that a reform can only be successful if the existing teacher beliefs are taken into account. Considerations of the national context and needs are also important, according to Brown et al. (Citation2019), teacher beliefs arise from specific historical, cultural, social and policy context within which the teachers operate.

While teachers’ beliefs have been extensively studied, there is a scarcity of fully developed survey instruments that have a particular focus on assessment. One notable exception is the “Teacher Conception of Assessment” (TCoA) instrument, which has been implemented and validated internationally (Brown et al., Citation2019). As beliefs about assessment are shown to be closely related to beliefs about teaching (Chen & Brown, Citation2016), these authors have implemented this instrument, in conjunction with a further instrument “Approaches to Teaching Inventory” (ATI). Although these instruments have shown different factor structures, depending on the educational and cultural context and the different samples utilised (Brown et al., Citation2019; Prosser & Trigwell, Citation2006), their prior use indicates they have a potential suitability for the current study, when adapted to the Estonian context in order to explore the combined influence of science teachers’ beliefs about teaching and about assessment on an educational assessment reform adopted in Estonia.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. The nature of teacher beliefs

The nature of teacher beliefs has been explored for more than half a century (Fives & Buehl, Citation2012). Such beliefs have been described as subjective claims that the individual accepts, or wants to be true (e.g., Pajares, Citation1992; Richardson, Citation1996), as well as an individual’s conceptions of that expected to be, need to be, or are preferable (e.g., Nespor (Citation1987); Basturkmen (Citation2004). In addition, Pajares (Citation1992) has argued that many other terms such as attitudes, values, axioms, opinions, ideology, perceptions, preconceptions, dispositions, and implicit theories are actually beliefs in disguise. In fact, he concludes,

“knowledge and beliefs are inextricably intertwined, but the potent affective, evaluative, and episodic nature of beliefs makes them a filter through which new phenomena are interpreted” (Pajares, Citation1992, p. 325).

Furthermore, many authors (e.g., Barnes et al., Citation2015; Brown, Citation2004, Citation2006; Kember, Citation1997; Thompson, Citation1992) have used the term “conception” in the same manner as, or simultaneously with, beliefs. This is adopted by the current study, i.e. “beliefs” are equated with “conceptions”.

2.2. Teacher beliefs about the approaches to teaching

Teacher beliefs have been studied in order to understand how they affect teaching (Fives & Buehl, Citation2012; Fives et al., Citation2015; Pajares, Citation1992). Many authors argue that teacher beliefs about teaching are closely related with their preferred approaches to teaching and are good predictors of teaching action—i.e. how, what and why teachers teach students (Alt, Citation2018; Bonnes & Hochholdinger, Citation2020; Kember, Citation1997). Based on different studies, two broad and conceptually opposite teaching approaches have been identified: namely, teacher-centred and student-centred (Cuban, Citation2007; Fives et al., Citation2015; Kember, Citation1997; Trigwell, Citation2012).

A teacher-centred approach, also known as a traditional approach, is mainly associated with behaviourist learning theories (Alt, Citation2018; Chan & Elliot, Citation2004; Fives et al., Citation2015), according to which the teacher controls the, what, when and under which conditions the learning takes place, seeing teaching as based primarily on the transfer of knowledge, skills and values. Other studies have linked this teaching approach with “drilling for an exam”, where the teacher and textbooks are seen as the main authoritative sources of knowledge (Watkins & Biggs, Citation2001).

A student-centred teaching approach is mainly associated with constructivist theories of learning (Alt, Citation2018; Chan & Elliot, Citation2004; Windschitl, Citation2002), according to which students’ ideas are seen as central to the learning and students are encouraged to construct and develop their own knowledge (Trigwell, Citation2012). Through the teacher facilitating understanding and encouraging conceptual change (Kember, Citation1997), learning is often based on student discussion and hands-on investigation (Tal et al., Citation2014).

Teachers who believe in the merits of teacher-centred approaches, are defined in the current article as having teacher-centred beliefs, while those believing in the value of student-centred approaches, have student-centred beliefs. Nevertheless, while conceptually opposite, teachers can simultaneously hold beliefs reflecting both, teacher- and student-centred approaches (Chen & Brown, Citation2016). However, several studies have found that teacher-centred beliefs tend to dominate among teachers (Duru, Citation2015; Gill & Hoffma, Citation2009; Ling, Citation2003), especially among teachers having extensive teaching experience (Uibu et al., Citation2011).

Previous research has indicated that most Estonian science teachers tend to reflect constructivist beliefs (Henno et al., Citation2017; OECD, Citation2015), but at the same time, to promote passive learning strategies in the classroom (OECD, Citation2015). The teachers’ tendency to express constructivist beliefs may be linked to the fact that since 1996, teacher education in Estonia (both pre- and in-service) has legitimised the value of a modern approach to learning (Sarv, Citation2014). As teacher beliefs may not necessarily be enacted in the classroom (Hancock & Gallard, Citation2004; Lederman, Citation1999), many teachers may keep using practices rooted in earlier education paradigms (e.g., behaviourist, Soviet, traditional).

2.2.1. Approaches to teaching inventory

An improved version of Approaches to Teaching Inventory (ATI; Prosser & Trigwell, Citation2006) was shown to have good psychometric properties and exhibit a two-factor structure. This ATI instrument reflected a teacher-centred approach to promote the transfer of knowledge and a student-centred approach aiming to encourage students to develop new knowledge (conceptual change/student focus; Stes et al., Citation2010; Trigwell, Citation2012).

The ATI instrument has been widely used in different countries and mostly implemented in different disciplines within higher education (e.g., Goh et al., Citation2014; Prosser & Trigwell, Citation2006; Stes et al., Citation2010; Tezci, Citation2017). Nevertheless, despite its wide use and positive validity evidence, some studies (see, Meyer & Eley, Citation2006) have seriously questioned the psychometric properties of ATI. As a solution, Prosser and Trigwell (Citation2006) suggested the need to adapt the formulation of items to the context in which the questionnaire was to be used.

2.3. Teacher beliefs about the purposes of assessment

Teacher beliefs about the purposes of assessment impact on how assessment is implemented in classroom settings (Brown, Citation2008). According to a literature review covering the last decade, by Barnes et al. (Citation2015), different approaches to assessment, based on teacher beliefs, have been published. The framework, developed by Brown (Citation2004, Citation2006, Citation2008), puts forward four types of teacher beliefs about the nature and purposes of assessment:

to improve teaching and learning (improvement). The assessment provides useful and accurate information to teachers and students. Teachers can undertake necessary changes to improve the quality of their teaching instruction. Students are informed of their performance and thus become aware of their own learning needs. The key issues for this purpose of assessment are: “who has learned what?” and “who needs to be taught what next?” (Brown et al., Citation2011).

to hold schools and teachers accountable for their own effectiveness and achievement related to societal goals and expectations (school and teacher accountability). Such assessment is usually executed using student performance on external, high-stakes examinations, or tests. Examination results are utilised to demonstrate, publicly, whether teachers and school are performing well. Through assessment, it is possible for schools and teachers to be rewarded (e.g., paid bonuses), or punished (e.g., dismissed) for exceeding, or failing to meet, the required standards. (Brown, Citation2008; Chen & Brown, Citation2016)

to hold a student responsible for his or her own learning (student accountability). This form of assessment shows the extent to which a student meets the criteria. The student’s performance is usually assessed by exams, or tests and is awarded via grades and certificates (Chen & Brown, Citation2016). Teachers generally believe that students need to receive grades, because grading motivates them to learn (Rosin et al., Citation2021).

there is no purpose, as the assessment is felt fundamentally irrelevant for teachers and students (irrelevance). The feedback from assessment is felt to be inaccurate and/or inappropriate and is therefore ignored. The assessment has a negative effect on teacher’s autonomy and professionalism and distracts from the real purpose of teaching (student’s learning). As assessment is believed to be an inaccurate process, teachers have a legitimate reason to ignore outcomes. (Brown, Citation2008)

Measuring teacher beliefs about the purposes of assessment

Based on the above theoretical framework, Brown et al. developed a questionnaire (e.g., Brown, Citation2004, Citation2006; Brown et al., Citation2019). It is the most well-known assessment-belief survey instrument, which has been translated and administered in various countries (Brown et al., Citation2019; Darmody et al., Citation2020). The initial version labelled “Teachers’ Conception of Assessment” (TCoA, Brown, Citation2004) has been validated twice, based on data from New Zealand and Queensland, Australia (Brown, Citation2006, TCoA-III). However, data gathered by this instrument have indicated differing factor structures in different countries, which have been explained by cross-cultural aspects (Brown et al., Citation2019). Based on the educational jurisdiction of a country, Brown et al. (Citation2019), was able to organise two groups: countries having relatively low-stakes assessment practices (i.e., New Zealand, Australia (Queensland), Cyprus, and Spain (Catalonia) and others having high-stake assessment practices (i.e., China, Hong Kong, Egypt, India, and Ecuador). In the “low-stake countries”, few if any, mandatory national student assessments occur and assessment decisions are made mainly at the level of the local jurisdiction, or school (Brown, Citation2008; Brown & Remesal, Citation2012). In “high-stake countries”, public examinations play an important role in both teachers’ and students’ lives, determining the position of a student between different levels of education and giving acceptance into high-quality institutions (Barnes et al., Citation2015).

Results from assessment belief surveys in “low-stake countries” showed, in general, that teachers believed student assessment was relevant for improving teaching and learning, while the improvement purpose was weakly correlated with student accountability purposes (assessment making students responsible for their learning; Brown, Citation2008; Brown et al., Citation2019). In contrast, teacher beliefs in Hong Kong and China (both high-stake countries) showed a strong positive association between improvement and accountability (Brown et al., Citation2011; Chen & Brown, Citation2016), where the teachers believed that the accountable function of assessment (i.e. testing) supported the improvement of teaching and learning.

Many of the above studies have shown that, globally, educational policy holds generally two purposes for assessment: improvement on the one hand, and accountability of schools, teachers and students, on the other (Brown et al., Citation2019). This suggests that teachers are expected to support the achievement of the two purposes simultaneously. However, such duality has been shown to lead to situations where teachers feel stressed by the strong tension between using assessment for improvement of teaching and learning, and assessment used to keep students, teachers and schools accountable for their effectiveness (Barnes et al., Citation2015; Bonner, Citation2016).

2.4. The Estonian context

In order to understand and contextualize Estonian science teachers’ beliefs about teaching and assessment, it is appropriate to reflect on Estonian educational policies and reforms. Since 2011, the Estonian educational policy has been more strongly focusing on student-centred teaching and assessment (Estonian Goverment,, Citation2011).In this light, a new education document developed in 2014 is “The Estonian Lifelong Learning Strategy 2020” (Estonian Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2014). One aim of this strategy is to create a formative external assessment system that would support the learning of key competences, as well as the individual and social development of the student, as determined by the curriculum.

The Estonian national curriculum (Estonian Goverment, Citation2011; Estonian Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2018) also gives teachers relative freedom as to how and what to teach or assess in practice. According to the RAKE study (Aksen et al., Citation2018), the use of formative assessment (including a wide variety of approaches), has been developing in Estonian schools to date. However, according to the same study, formative assessment is perceived by the teachers as mostly the giving of oral or written feedback to students during the learning process. Also, lower secondary teachers often provide students with descriptive feedback alongside summative grades, which, in the respective literature (Black & Wiliam, Citation1998; Crooks, Citation1988; Kluger & DeNisi, Citation1996; Wiliam, Citation2007), has been called “formative use of summative assessments”. Yet, according to the RAKE study, students’ self- and peer-assessment plays a rather a small role at all Estonian school levels. Furthermore, in the upper secondary school, where summative testing is strongly dominating, the use of formative assessment strategies is rather marginal in student assessment (Aksen et al., Citation2018).

The national graduation examinations, so far, have been limited by their scope and place emphasis on the assessment of content knowledge, rather than a wider range subject-related competences (Erss et al., Citation2014), this being seen as one of the drawbacks of an external assessment strategy (Vitello & Williamson, Citation2017). The publication of school examination results has made teachers even more accountable and put them under additional pressure, as parents tend to take the results into account when considering school choice for their children (Erss, Citation2016). Such pressure may force teachers to emphasize drilling of specific skills and memorisation of facts even more than they would do normally (Rosin et al., Citation2021; Vaino et al., Citation2013). Therefore, Erss et al. (Citation2014) have characterised the Estonian curriculum policy as “decentralised centralist” (a decentralised curriculum policy with centralised control).

Most Estonian teachers are very experienced (average age 49 years, OECD, Citation2019), which indicates that most are used to a centralised testing system, based on examination, with roots dating back to Soviet times, with its highly centralised and standardised curriculum policy (Kesküla et al., Citation2012). Therefore, it can be speculated that teacher-centred beliefs and practices, seeded by the Soviet school system (Ruus et al., Citation2008), are ingrained in these teachers before educational decentralization in Estonia gaining independence and hence the beliefs teachers have acquired during the Soviet period may continue to impact their choice of teaching practices (Uibu et al., Citation2011). Thus, it is not surprising that, for these teachers, the existence of centrally administered examinations, with its rather narrow content knowledge focus, is perceived as a norm, while the reform promotes a wider educational competence with a less-centralised assessment system, seen as somewhat the opposite (Vahtla, Citation2019; Wright, Citation2019). Notwithstanding the high proportion of teachers obtaining their qualifications and having practiced during the Soviet time, teachers of the next generations have been employed in schools, trained with somewhat different backgrounds and beliefs.

3. AIM and research questions

The aim of this study is to model Estonian science teachers’ existing beliefs about approaches to teaching and the purposes of assessment and to determine connections between these beliefs in order to explore the influence of science teacher beliefs on the opposition to educational assessment reform adoption in Estonia. Based on the aim, the following research question are posed:

What is the factors structure of Estonian science teachers’ beliefs about approaches to teaching and the purposes of assessment?

What beliefs do Estonian science teachers hold and how are they interrelated, concerning approaches to teaching and the purposes of assessment?

4. Methodology

4.1. Instruments

This study integrates ATI version by Chen and Brown (Citation2016) for studying teacher beliefs about approaches to teaching containing items related to examination preparation and TCoA, integrated with C-TCoA from Chen and Brown (Citation2016) and TCoA-III from Brown (Citation2008), for studying teacher beliefs about the purposes of assessment, into a single instrument.

All twelve items were included in ATI, adapted from the modified ATI instrument by Chen and Brown (Citation2016). The TCoA scale comprised 20 items from C-TCoA (Chen & Brown, Citation2016) plus 8 items adapted from TCoA-III (Brown, Citation2008; 5 items from “Student Accountability”, 2 items from “Irrelevance” and one item from “Teaching Improvement”). In sum, the final TCoA scale consisted of 28 items. Both parts of the questionnaire (ATI and TCoA) use a balanced six-point agreement rating scale, with three positive options (slightly agree, moderately agree, mostly agree) and three corresponding negative options.

4.2. Validation of instruments

As the factors and items of both, ATI and TCoA have been proven to be relatively context-dependent, plus the fact that they were translated into Estonian, determination of the construct, face and content validity of both instruments was undertaken.

To determine face validity, the instrument was piloted with 40 voluntary science teachers who participated in an in-service course, aiming to improve the comprehensibility and unambiguity of the items. Based on teacher feedback, the wording was changed in 7 items to better relate to an Estonian format. The procedure to determine construct validity is described in more detail under the “analysis strategy”.

The consistency of the instruments between the developed theoretical constructs and national curriculum, was evaluated by four science education experts from the University of Tartu. The experts found general consistency, but made minor suggested modifications were taken into account by the authors.

4.3. Sample

The sample included 319 science teachers who taught chemistry, physics, geography, biology and science (science as a single subject up to the 7th grade) at both, lower and upper secondary school level. Background information of the participating teachers can be found in .

Table 1. Background information of the participant teachers (N = 319)

4.4. Data collection

The questionnaire was administered online in February/April 2020 using the Google Drive environment. The contacts for all general schools in Estonia were obtained from the governmental website (Eesti.ee), after which each science teacher was contacted by email. A total of 1000 electronic questionnaires were sent out in February and March 2020. In total, 319 completed questionnaires were returned by April 2020.

4.5. Ethical issues

Answering the questionnaire was voluntary. In case of additional queries, the respondents had the possibility to contact the first author by email. Data was collected anonymously with the first author being responsible for maintaining data security.

4.6. Analysis strategy

The data analyses were conducted using MPlus programme 8.1 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2012). First, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and parallel analysis were used together to carry out the validation of the constructs and to develop a model for both scales, respectively. Criteria used to determine the number of possible EFA factors were: (1) eigenvalues > 1.00, (2) at least three items which were conceptually coherent, (3) items with regression loadings of ≥ .40 (Hair et al., Citation1998), and (4) all cross-loadings <.30 (Costello & Osborne, Citation2005).

Secondly, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to establish the fit of the new, trimmed model. According to the Monte Carlo analysis (Hu et al., Citation1999), the following indices were used to determine the goodness of the statistical models: standardized root means square residual (SRMR< .08), the Tucker- Lewis index (TLI > .95), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA<.06). This study also took into account that a Comparative fit index (CFI) value of 0.90 indicates that the model fit was acceptable (Hu et al., Citation1999).

Cronbach alpha values were calculated for each of the 4 factors found. Based on the criteria suggested by Ursachi et al. (Citation2015), two factors were acceptable (α between 0,6–0,7), and the other two, good (α between 0,7 and 0,8) levels of reliability (see, . As CFA its own reliability assessment indicators (Brown, Citation2008), traditional reliability assessment (e.g., Cronbach alpha estimation) could be considered as less important in ensuring reliability.

Table 2. Mean, standard deviation, reliability coefficient, and intercorrelations between ES-ATI, and ES-TCoA factors

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to determine the relationship between the ATI and TCoA factors. Predictor paths were tested from each ATI factor to the TCoA factors and statistically non-significant paths were removed. Details of the steps taken to revise the models were omitted for brevity.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to compare differences between groups, measured by the arithmetic mean of the factors presented. Because of the unequal sample sizes, it was only possible to carry out a comparative analysis between groups of teachers with different teaching experience (but not e.g., educational degrees or gender).

5. Results

5.1. Factor structure of teachers’ beliefs towards approaches to teaching and purposes of assessment

The EFA and parallel analysis identified two factors, related to approaches to teaching as expected (“teacher-centred” and “student-centred”). Four items with low factor loadings, or not conceptually coherent with each other were excluded from further analysis. The goodness of fit of the model, conducted with 8 items, was confirmed by the CFA analysis (SRMR = .051; CFI = .96; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .047).

The EFA and parallel analysis identified four factors indicating the purposes of assessment (“teaching improvement”, “irrelevance”, “examination”, and “schools and teacher accountability”). The 16 items with low factor loadings and not conceptually coherent were excluded from the analysis. The goodness of fit model, conducted with 13 items, was confirmed by the CFA analysis (SRMR = .053; CFI = .96; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .043). From now on, these two factors are labelled as ES-ATI and ES-TCoA, respectively. Items and their loading on a particular factor were as shown in

Table 3. ES-ATI and ES-TCoA factors, items, and their factor loadings

The highest mean score (M = 5.3) within the beliefs about approaches to teaching, was given by teachers to the “student-centred” teaching approach (see,

The highest rating (M = 4.30) within the beliefs about the purposes of assessment was given by the teachers for “Teaching Improvement”. However, the mean score of the factor “Examination” was also high (M = 3.83). Inter-correlations between the two factors in the scale Approaches to teaching and the four factors in the Purposes of assessment were weak, indicating relative independence of one factor from another (see inter-correlation between the factors in

Based on ANOVA, no statistically significant difference was found amongst teaching and assessment beliefs, between teachers having different teaching experiences (more than 20 years, 11–20 years, under 11 years).

5.2. What beliefs do Estonian science teachers hold concerning approaches to teaching and the purposes of assessment and how are these beliefs mutually interrelated?

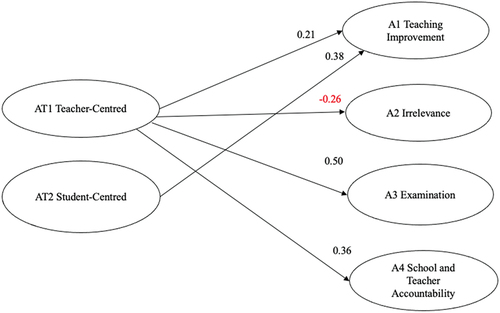

In order to demonstrate the interrelated nature between teaching beliefs and assessment beliefs, SEM analysis was implemented. The factors reflecting teacher beliefs about the approaches to teaching were taken as independent variables and factors reflecting assessment beliefs, as dependent. In accordance with Brown (Citation2008) who found that teacher beliefs about teaching approaches impacted on the way the purposes of assessment were perceived. A structural model was developed (see,

The “teacher-centred” factor predicted positively, three factors (i.e. positive paths to “teaching improvement”, “examination”, “school and teacher accountability”), and negatively, one factor (“irrelevance”). The “student-centred” factor predicted positively, only the “teaching improvement” factor. SEM showed that as there are reasonably substantial and meaningful relations between expected teaching approaches and purposes of assessment, these relations explain, at best, a moderate amount of variance.

6. Discussion

In this study, models were constructed to examine science teachers’ beliefs about approaches to teaching and purposes of assessment and how they are related to each other. First, the goodness of each model was reviewed and discussed. Second, the results with respect to the student-centred reform implementation, were interpreted.

6.1. Factor structure of teacher beliefs about teaching and assessment

In the current study, two domain factors in Estonian science teachers’ beliefs about approaches to teaching were identified: “teacher-centred” and “student-centred” (ES-ATI). This result confirms the theoretical construct established in some earlier studies (Cuban, Citation2007; Fives et al., Citation2015; Kember, Citation1997; Trigwell, Citation2012). The internal reliability values (based on both Cronbach Alpha and CFA) of the two factors in ES-ATI were acceptable and similar to the structure developed by Prosser and Trigwell (Citation2006) who also showed a two-factor solution. While the “teacher-centred” factor is reflecting beliefs that emphasize the transfer of knowledge from teacher to student, then the “student-centred” factor is reflecting beliefs that teachers should help students to construct their own knowledge. The factor structure in the current study is slightly different from the version developed by Chen and Brown (Citation2016) who identified three factors, two of them reflecting different aspects of teacher-centred beliefs.

Within Estonian science teachers’ beliefs about purposes of the assessment, four factors were identified: “teaching improvement”, “irrelevance”, “examination” and, “schools and teacher accountability” (ES-TCoA). The four-factor model confirms the theoretical framework developed by Brown (Citation2004, Citation2008). Also, the reliability values (based on both Cronbach Alpha and CFA) of the four factors in ES-TCoA were acceptable and remained in a similar range as in the study conducted by Brown (Citation2006), and by Chen and Brown (Citation2016). The “teaching improvement” factor reflects teachers’ beliefs that assessment should support teaching. Items in the “irrelevance” factor express the beliefs according to which assessment is perceived as unfair and inaccurate towards students. The “examination” factor reflects teacher beliefs, that school-based assessment teaches students the techniques to achieve good results in external exams. The “school and teacher accountability” factor represents teacher beliefs that assessment is a good indicator of school quality and to monitor teachers’ work. The current ES-CToA factor structure differs somewhat from the structure developed in other empirical studies, containing less factorial dimensions (e.g., Brown et al., Citation2011; Chen & Brown, Citation2016). Though, it confirms the conclusions from Prosser and Trigwell (Citation2006) and Brown et al. (Citation2019), that both scales are quite context-dependent, i.e. the data and the sample play an important role in shaping the factor structure.

ATI has mainly been tested and validated in the context of higher education (Tezci, Citation2017). Based on the identified CFA indicators, the ATI instrument (Prosser & Trigwell, Citation2006) can be adapted at the secondary education level, aligning with Chen and Brown (Citation2016) while maintaining the initial conceptual meaning and consistency. However, it needs to be treated with caution if used in another cultural contexts, as indicated by Trigwell et al. (Citation2005). Although the TCoA, has mainly been tested and validated in the context of primary and secondary school level involving all subject teachers at the same time (Brown et al., Citation2019), this study shows that it is possible to adapt this instrument even for teachers teaching one subject area. Thus, the ES-ATI and ES-TCoA instruments have been adapted meaningfully so that its data can interpret Estonian science teachers’ beliefs about teaching and assessment.

6.2. Estonian science teachers’ beliefs about teaching and assessment and how they are related to each other

The results of the current study showed that Estonian science teachers had relatively high acceptance of developing student-centred beliefs, which could be explained by the impact of the educational reforms in Estonia, together with respective changes in teacher in- and pre-service education towards promoting constructivist approaches to teaching, learning and assessment since re-independence (established thirty years ago). Although the mean score for student-centred beliefs was higher than for teacher-centred beliefs, it was noticeable that both values were above average. It could be assumed that the relatively high support for traditional ways of teaching were still influenced by the centralized practice of the prior Soviet school system (Kesküla et al., Citation2012), or by the long-term external assessment tradition with its school ranking system and the associated parental pressure in Estonia, which kept teachers highly accountable for their teaching (Erss et al., Citation2014) and which became part of science teacher beliefs (Bandura, Citation1986; Pajares, Citation1992). This explanation is also complemented by the structural model (SEM) developed in this study, showing a significant positive path from teacher-centred teaching beliefs to exam-oriented beliefs, as well as to school and teacher accountability assessment beliefs.

There was also a low, but positive correlation between “teacher-centred” and “student-centred” beliefs, showing that many teachers held simultaneously beliefs that were theoretically opposite. This tendency was also established in a recent qualitative study among Estonian science teachers (Rosin et al., Citation2021) and confirmed findings of studies conducted in other countries (Alt, Citation2018; Chan & Elliot, Citation2004). The contradictory beliefs of Estonian science teachers were not surprising, as earlier studies (Henno et al., Citation2017; OECD, Citation2015, Citation2019) showed the tendency of Estonian teachers to express simultaneously constructivist beliefs, yet teacher-centred practices. This tendency was explained by Alt (Citation2018), who suggested that the educational reforms promoting constructivist approaches, supported by teacher professional development programmes, could trigger a different belief and understanding of teaching. There was also a possibility that relatively high acceptance of student-centred beliefs was partially a result of a tendency to provide socially desirable responses (Paulhus, Citation2002) in accordance with the existing social norms, shaped, in turn, by international and national educational policies (e.g., Assessment Reform Group Citation1999; Ministry of Education, 2011; OECD, Citation2013), but which were not fully internalized by the teachers.

The current study did not confirm the findings by Uibu et al. (Citation2011), in which that teacher with longer teaching experience tended to express more teacher-centred beliefs than those with less experience. Furthermore, the current finding could still be a result of the same “social desirability effect” (Paulhus, Citation2002), as previously described i.e., it could be speculated that experienced teachers were just more aware of the social expectations (norms) than those less experienced. The latter aspect might also draw attention to the need to study teacher beliefs about teaching and assessment with multiple methods instead of one, as was suggested by Rokeach (Citation1968): “[beliefs] must be inferred as best one can, with whatever psychological devices available, from all the things the believer says as well as do” (p. 2).

It is also appropriate to note that the Estonian “decentralised centralist” curriculum policy (Erss et al., Citation2014), in itself, might reproduce such conflicting beliefs by teachers. Hence, it would appear that how teachers understood and value the opposing beliefs about teaching was sensitive to policy priorities.

According to the findings from applying SEM, there are two positive paths leading to the “teaching improvement” purpose of assessment: from “student-centred” teaching beliefs, and “teacher-centred” teaching beliefs. A single positive path between “student-centred” beliefs and “teaching improvement” beliefs is to be expected as, according to Brown (Citation2008), it reflects a more formative nature of assessment focused on guiding students and helping to modify teaching. The existence of other positive paths between those based on “teacher-centred” teaching beliefs and improvement purpose of assessment may be viewed as surprising. It may also show the classical meaning of teacher-centred beliefs about assessment, i.e assessment helps students gain good scores in examinations, cannot be considered unambiguously. Also, the positive correlation between “teacher-centred” and “student-centred” beliefs may also lead to the perception that some teachers in this sample, while generally using teacher-centred teaching approaches, also acquire certain assessment beliefs related to formative assessment. Such teachers can be referred to as a transition group, who are acquiring certain elements of a modern approach to teaching in terms of assessment and are, therefore, also more willing to implement educational reforms. Thus, teacher-centred teachers can be roughly divided into two groups in terms of assessment -

teachers who mainly collect learning evidence, typically through summative assessment (i.e., grades or scores, checking off student performance against criteria, placing students into groups based on performance, and reporting grades to parents, future employers, and educators.), and

teachers who use assessment as a tool to support learning and teaching (i.e., clear learning intentions, feedback, questioning, peer assessment, and self-assessment) before summative assessment and does so through a teacher-centred teaching approach in partly.

The belief in a “teacher-centred teaching approach with formative assessment” phenomenon can be a result of Estonian curriculum policy, according to which teachers, even with traditional teaching beliefs, are required to accept certain educational guidelines, i.e. use of elements of formative assessment in the classroom. A similar impact of a curriculum policy phenomenon is described also by Alt (Citation2018). Thus, this may lead to the conclusion that a more sophisticated model needs to be developed to better describe such transitional beliefs, or to the use of qualitative research methods to find more in-depth connections.

In this study, the four types of beliefs about the purposes of assessment had very low inter-correlations according to the strength of their interrelationship. Brown et al. (Citation2019) classified this as a high-stakes and low-stake assessment of a country. For example, in this study, the correlation between “examination” and “teaching improvement” was very low (r = .17). A similar factor dimension in high-stake examination countries like China (Brown et al., Citation2011; Chen & Brown, Citation2016), where accountability function of assessment where always seen as an essential part of teaching and learning, the correlation was found to be strong (r = .80 / = .57) and emphasizing the testing of education as a force for improved learning. By contrast in “low-stake countries”, such as New Zealand, where the above purposes of assessment were weakly correlated (Brown, Citation2008), there was an understanding that improvement of assessment was supportive of diagnostic pedagogical practices. Thus, in this study, where the accountability function of assessment had a slightly stronger link to exam-oriented assessment (r = .26), it could be claimed, the overall assessment culture could be positioned among the “low-stake” countries.

7. Conclusions and recommendations

In this study, a two-factor structure was found to identify teacher beliefs about teaching and a four-factor structure on Estonian science teacher assessment beliefs. The two models generated showed that Estonian science teachers held several beliefs about approaches to teaching and the purposes of assessment. By combining these two models this enabled these beliefs to be more visible, leading to several interpretations. The study demonstrated that Estonian science teachers tended to reflect student-centred beliefs towards teaching and assessment, which seemed to support the implementation of a constructivist assessment reform within the country. At the same time, the relatively high rating of teacher-centred and examination beliefs somewhat counteracted the reform ideas. Thus, such a paradigm shift was seen as taking time to be fully implemented, it being speculated that teachers might currently perceive any externally administered form of assessment as a way to make them more accountable, and not as a tool of formative assessment that could help them to plan their teaching and respond better to students’ individual learning needs. Therefore, a smoother transition, in the main through giving teachers time to become accustomed to an alternative external assessment system with a formative function, could be taken as inevitable when implementing the reform. Though constructivist approach, together with formative assessment, has played an important role in Estonian teacher education for years, at both—master’s level and with an in-service provision, more attention needed to be paid to the practical aspects of formative assessment (e.g., how to use the feedback that teachers gain from student assessment, including science e-test feedback), enabling thereby constructivist beliefs to become more and more a part of every-day teaching and student assessment. This study re-confirmed the theoretical underpinnings related to teacher beliefs about teaching and assessment, including their interrelated nature, but it also added contextual features to the existing model. It was suggested that the adapted instrument could be used in similar settings as a single, or pre-post instrument, to measure the impact of an intervention to support reform ideas, both short-term and longitudinal.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Horizon 2020 Twinning project 252470 ‘SciCar’. The authors are very thankful to the teachers who devoted their time and participated in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aksen, M., Jürimäe, M., Nõmmela, K., Saarsen, K., Sillak, S., Eskor, J., Vool, E., & Urmann, H. (2018). Eesti üldhariduskoolides kasutatavad hindamissüsteemid. [Assessment systems used by Estonian general education schools.] Tartu Ülikool. https://www.hm.ee/sites/default/files/uuringud/hindamine_lopparuanne_15.okt_loplik.pdf

- Alt, D. (2018). Science Teachers’ conceptions of teaching, attitudes toward testing, and use of contemporary educational activities and assessment tasks. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 29(7), 600–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2018.1485398

- Assessment Reform Group, 1999 Assessment for learning: Beyond the black box , Assessment Reform Group (Assessment Reform Group)

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall.

- Barnes, N., Fives, H., & Dacey, C. M. (2015). Teachers’ beliefs about assessment. In H. Fives & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International handbook of research on teacher beliefs (pp. 284–300). Routledge.

- Basturkmen, H. (2004). Teachers’ stated beliefs about incidental focus on form and their classroom practices. Applied Linguistics, 25(2), 243–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/25.2.243

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139–148 https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050108.

- Bonner, S. M. (2016). Teachers’ perceptions about assessment: Competing narratives. In G. T. L. Brown & L. Harris (Eds.), Handbook of human and social conditions in assessment (pp. 21–39). Routledge.

- Bonnes, C., & Hochholdinger, S. (2020). Approaches to Teaching in Professional Training: A Qualitative Study. Vocations and Learning, 13(3), 459–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-020-09244-2

- Boyle, A., & Hutchison, D. (2009). Sophisticated tasks in e‐assessment: What are they and what are their benefits? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(3), 305–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930801956034

- Brown, G. T. L. (2004). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment: Implications for policy and professional development. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 11(3), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594042000304609

- Brown, G. T. L. (2006). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment: Validation of an abridged instrument. Psychological Reports, 99(5), 166–170. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.99.1.166-170

- Brown, G. T. L. (2008). Conceptions of assessment: Understanding what assessment means to teachers and students. Nova Science.

- Brown, G. T. L., Hui, S. K. F., Yu, W. M., & Kennedy, K. J. (2011). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment in Chinese contexts: A tripartite model of accountability, improvement, and irrelevance. International Journal of Educational Research, 50(5–6), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2011.10.003

- Brown, G. T. L., & Remesal, A. (2012). Prospective teachers’ conceptions of assessment: A cross-cultural comparison. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.5209/revSJOP.2012.v15.n1.37286

- Brown, G. T. L., & Gao, L. (2015). Chinese teachers’ conceptions of assessment for and of learning: Six competing and complementary purposes. Cogent Education, 2(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2014.993836

- Brown, G. T. L., Gebril, A., & Michaelides, M. P. (2019). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment: A global phenomenon or a global localism. Front. Educ, 4(16), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00016

- Chan, K. W., & Elliot, R. G. (2004). Relational analysis of personal epistemology and conceptions about teaching and learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(8), 817–831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2004.09.002

- Chen, J., & Brown, G. T. L. (2016). Tension between knowledge transmission and student-focused teaching approaches to assessment purposes: Helping students improve through transmission. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 22(3), 250–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1058592

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, & Evaluation, 10, 1–9 https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868.

- Crooks, T. J. (1988). The impact of classroom evaluation practices on students. Review of Educational Research, 58(4), 438–481. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543058004438

- Cuban, L. (2007). Hugging the middle: Teaching in an era of testing and accountability, 1980–2005. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 15(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v15n1.2007

- Darmody, M., Lysaght, Z., & O’Leary, M. (2020). Irish post-primary teachers’ conceptions of assessment at a time of curriculum and assessment reform. Assessment in Education-Principles Policy & Practice, 27(5), 501–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2020.1761290

- Duffee, L., & Aikenhead, G. (1992). Curriculum change, student evaluation, and teacher practical knowledge. Science Education, 76(5), 493–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730760504

- Duru, S. (2015). A metaphor analysis of elementary student teachers’ conceptions of teachers in student- and teacher-centered contexts. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 15(60), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2015.60.16

- Erss, M., Mikser, R., Löfström, E., Ugaste, A., Rõuk, V., & Jaani, J. (2014). Teachers’ views of curriculum policy: The case of Estonia. British Journal of Educational Studies, 62(4), 393–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2014.941786

- Erss, M. (2016). Comparing teacher autonomy in three European countries: Estonia, Finland, and Germany. European Journal of Curriculum Studies, 2(2), 309–323. http://pages.ie.uminho.pt/ejcs/index.php/ejcs/article/view/94

- Estonian Government., National Curriculum for basic schools. Regulation of the Government of the Republic of Estonia, Tallinn 2011 Accessed22 June 2021 https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/524092014014/consolide

- Estonian Ministry of Education and Research. 2014. The Estonian lifelong learning strategy 2020. https://www.hm.ee/en/estonian-lifelong-learning-strategy-2020

- Estonian Ministry of Education and Research. (2018). Basic schools and upper secondary schools act. https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/501022018002/consolide

- Fives, H., & Buehl, M. (2012). Spring cleaning for the ‘messy’ construct of teachers’ beliefs: What are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us? In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, & T. Urdan (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook, Vol. 2. Individual differences and cultural and contextual factors (pp. 471–499). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13274-019

- Fives, H., Lacatena, N., & Gerard, L. (2015). Teachers’ beliefs about teaching (and learning). In H. Fives & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International Handbook of Research on Teachers’ Beliefs (pp. 149–265). Routledge.

- Gill, M. G., & Hoffma, B. (2009). Shared planning time: A novel context for studying teachers’ discourse and beliefs about learning and instruction. Teachers College Record, 111(5), 1242–1273. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810911100506

- Goh, P. S. C., Wong, K. T., & Hamzah, M. S. G. (2014). The approaches to teaching inventory: A preliminary validation of the Malaysian translation. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v39n1.6

- Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1998). Multivariate data analysis with readings. In Englewood Chiffs (4th ed. ed.). NJ: Prentice- Hall International 72–79 .

- Hancock, E. S., & Gallard, A. J. (2004). Preservice science teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning: The influence of K-12 field experiences. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 15(4), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JSTE.0000048331.17407.f5

- Henno, I., Kollo, L., & Mikser, R. (2017). Eesti loodusainete õpetajate uskumused, õpetamispraktika ja enesetõhusus TALIS 2008 ja 2013 uuringu alusel [Estonian science teachers’ pedagogical beliefs, teaching practices and self-efficacy based on the results of the TALIS 2008 and 2013 reports.]. Estonian Journal of Education, 5(1), 268–296. https://doi.org/10.12697/eha.2017.5.1.09

- Hu, L., Peter, M., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives, Structural Equation Modeling. A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Kember, D. (1997). A reconceptualization of the research into university academics’ conceptions of teaching. Learning and Instruction, 7(3), 255–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(96)00028-X

- Kesküla, E., Loogma, K., Kolka, P., & Sau-Ek, K. (2012). Curriculum change in teachers’ experience: The social innovation perspective. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 20(3), 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2012.712051

- Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback intervention on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254

- Lederman, N. G. (1999). Teachers’ understanding of the nature of science and classroom practice: Factors that facilitate or impede the relationship. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 36(8), 916–929. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199910)36:8<916::AID-TEA2>3.0.CO;2-A

- Lees, M. (2016). Estonian education system 1996-2016 . Reform and their impact. Estonian Ministry of Education and Research . Accessed 20 January 2020 http://4liberty.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Estonian-Education-System_1990-2016.pdf

- Ling, L. Y. (2003). What makes a good kindergarten teacher? A pilot interview study in Hong Kong. Early Child Development and Care, 173(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443022000022396

- Meyer, J. H. F., & Eley, M. G. (2006). The approaches to teaching inventory: A critique of its development and applicability. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(3), 633–649. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X49908

- Nespor, J. (1987). The role of beliefs in the practice of teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19(4), 317–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027870190403

- OECD. (2013). Synergies for better learning: An international perspective on evaluation and assessment. OECD Publishing, Paris. Accessed 20 January 2020 http://www.oecd.org/education/school/synergies-for-better-learning.htm

- OECD. (2015). Teaching beliefs and practice. In Teaching in focus, No. 13 (pp. 1–4). https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrtkpwtklnx-en

- OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 Results (Vol. ume I). https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en

- Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307

- Paulhus, D. L. (2002). Socially desirable responding: The evolution of a construct. In H. I. Braun, D. N. Jackson, & D. E. Wiley (Eds.), The role of constructs in psychological and educational measurement (pp. 49–69). Erlbaum.

- Pedaste, M. (2018). Loodusvaldkonna õpitulemuste e-hindamise kontseptsiooni täiendatud versioon. [An updated version of the concept of e-assessment of learning outcomes in science. Innove. https://www.innove.ee/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Loodusvaldkonna_e_hindamise_kontseptsioon_august_2018.pdf

- Pellegrino, J. W. (2014). Assessment as a positive influence on 21st century teaching and learning: A systems approach to progress. Psicologıa Educativa, 20(2), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2014.11.002

- Prosser, M., & Trigwell, K. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis of the approaches to teaching inventory. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(2), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X43571

- Richardson, V. (1996). The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. In J. Sikula (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 102–119). Macmillan.

- Ridgway, J., McCusker, S., & Pead, D. (2004). Literature review of e-assessment. Bristol.

- Rokeach, M. (1968). Beliefs, attitudes, and values: A theory of organization and change. Jossey-Bass.

- Rosin, T., Vaino, K., Soobard, R., & Rannikmäe, M. (2021). Estonian science teacher beliefs about competence-based, science E-testing. Science Education International, 32(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.33828/sei.v32.i1.4

- Ruus, V.-R., Henno, I., Eisenschmidt, E., Loogma, K., Noorväli, H., Reiska, P., & Rekkor, S. (2008). Reforms, developments and trends in Estonian education during recent decades. In J. Mikk, M. Veisson, & P. Luik (Eds.), Reforms and innovations in Estonian education (pp. 11–26). Peter Lang Publishers House.

- Sarv, E.-S. (2014). A Status paper on school teacher training in Estonia. Journal of International Forum of Educational Research, 1(2), 106–158 http://ejournal.ifore.in.

- Stes, A., De Maeyer, S., & Van Petegem, P. (2010). Approaches to teaching in higher education: Validation of a Dutch version of the approaches to teaching inventory. Learning Environments Research, 13(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-009-9066-7

- Tal, T., Alon, N. L., & Morag, O. (2014). Exemplary practices in field trips to natural environments. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 51(4), 430–461. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21137

- Tezci, E. (2017). Adaptation of ATI-R scale to Turkish samples: Validity and reliability analyses. International Education Studies, 10(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v10n1p67

- Thompson, A. G. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and conceptions: A synthesis of the research. In D. A. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 127–146). MacMillan.

- Tobin, K., & McRobbie, C. J. (1996). Cultural myths as constraints to the enacted science curriculum. Science Education, 80(2), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-237X(199604)80:2<223::AID-SCE6>3.0.CO;2-I

- Trigwell, K., Prosser, M., & Ginns, P. (2005). Phenomenographic pedagogy and a revised approaches to teaching inventory. Higher Education Research and Development, 24(4), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360500284730

- Trigwell, K. (2012). Relation between teacher emotion in teaching and their approaches to teaching in higher education. Instructional Science, 40(3), 607–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-011-9192-3

- Uibu, K., Kikas, E., & Tropp, K. (2011). Instructional approaches: Differences between kindergarten and primary school teachers. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 41(9), 91–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2010.481121

- Ursachi, G., Horodnic, I. A., & Zait, A. (2015). How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Economics and Finance, 20, 679–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00123-9

- Vahtla, A. (2019). “Education minister: Abolishment of basic school exams not yet decided.” ERR, October 23. https://news.err.ee/994918/education-minister-abolishment-of-basic-school-exams-not-yet-decided

- Vaino, K., Holbrook, J., & Rannikmäe, M. (2013). A case study examining change in teacher beliefs through collaborative action research. International Journal of Science Education, 35(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2012.736034

- Vitello, S., & Williamson, J. (2017). Internal versus external assessment in vocational qualifications: A commentary on the government’s reforms in England. London Review, 15(3), 536–548.

- Watkins, D. A., & Biggs, J. B. (ed.). (2001). Teaching the Chinese learner: Psychological and pedagogical perspectives. Comparative Education Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong/Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Wiliam, D. (2007). Content then process: Teacher learning communities in the service of formative assessment. In D. B. Reeves (Ed.), Ahead of the curve: The power of assessment to transform teaching and learning (pp. 183–204). In Solution Tree.

- Windschitl, M. (2002). Framing constructivism in practice as the negation of dilemmas: An analysis of the conceptual, pedagogical, cultural, and political challenges facing teachers. Review of Educational Research, 72(2), 131–175. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543072002131

- Wright, H. 2019. “Changes to basic school exams to be discussed in public hearing.” ERR, October 15. https://news.err.ee/992041/changes-to-basic-school-exams-to-be-discussed-in-public-hearing