Abstract

Teaching research methods to tertiary students is fraught with challenges including the absence of an established pedagogy in teaching research, the complexity of research concepts and activities, and mixed levels of student engagement. This study provides a five-year review of an undergraduate health research subject to examine teaching strategies used to remediate the overall subject quality, and to develop a conceptual model to guide approaches to teaching undergraduate students from the lessons learnt. A mixed-methods approach was used to retrospectively analyse a range of student and staff indices including feedback from an undergraduate applied health research subject. The review examined data from 2016–2021 to identify effective strategies used across this period. Student performance and feedback were examined using simple descriptive statistics and content analysis of qualitative data. Four effective teaching strategies were identified: promoting reflection to reduce anxiety and identify learning needs; embedding opportunities for feedback and support; creating purpose-designed tools to address problem learning areas; and designing student-focused culture building activities directly addressing learning needs. The impact across the subject was seen in improved student performance and feedback. Three key goals form the backbone of the approach: to build a respectful culture; to ensure purposeful assessment design; and to focus on feedback. Building a respectful culture, ensuring purposeful assessment design and focussing on feedback were supported through the effective use of reflection and teamwork. This model can be used to inform evaluation processes and to design research and other skill-based subjects. Evaluation of this subject was a developmental and gradual process that changed the environment of the subject over time. Effective strategies included the use of authentic assessments that incorporated reflection, the alignment of workshops to assessment requirements and the inclusion of an ongoing cycle of formal and informal feedback. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model provided a useful way to reflect on the subject’s development over time. These lessons may offer useful guidance to others.

Public interest statement

Teaching research to university students is challenging for a number of reasons, that include the complexity of research concepts and activities and varying interest among students. A review of a health research subject looked for lessons learnt from student and teaching experiences over five years. Four effective teaching strategies were identified: promoting reflection to reduce anxiety and identify learning needs; embedding opportunities for feedback and support; creating purpose-designed tools to address problem learning areas; and designing student-focused activities to address learning needs. From the study a model was developed that can be used to inform future subject evaluations and to help design research and other skill-based subjects. The model involves building a respectful culture, ensuring purposeful assessment design and focussing on feedback supported through the effective use of reflection and teamwork.

1. Introduction

This paper reports on a five-year retrospective experience of teaching an applied research subject to undergraduate health science students. From our review of the strategies that were implemented during that time to overcome challenges, we propose a model for guiding teaching academics facing similar issues.

Our purposeful ecological approach was developed in response to poor student feedback on the subject, which indicated an overcrowded curriculum, that lacked direction, and contained considerable variation across workshop groups leading to surface learning at best. Students showed low interest in the subject material and perceived the value of the subject poorly. Workshop attendance was generally low and failure rates exceeded 20 percent. These issues were significant as many students were entering the final year of their course with poor understanding of the importance of research in health care, and how to apply these principles across their studies.

Problems with teaching research methods to undergraduates are well-recognised (Earley, Citation2014; Gunn, Citation2017; Rubenking & Dodd, Citation2018) with a review of 89 studies undertaken by Earley (Citation2014) identifying three main challenges to teaching undergraduate research methods:

Lack of evidence on how to teach research methods effectively

Complexity of research methods themselves, which involve many concepts and activities interrelating in different ways, depending on the specific research question

Inclusion of students in the same classroom who will eventually produce research with those who will use research in their work.

Earley (Citation2014) also found that personal student characteristics were commonly alluded to that further exacerbated these challenges. Students were seen as unsure about the relevance of research in their course and lives, anxious about subject difficulty, and uninterested and unmotivated to learn about research. The review also identified major gaps in the literature; there was little discussion about what students actually learnt from research methods courses or how to assess them (Earley, Citation2014).

The absence of an established pedagogy in teaching research methods (Nind & Lewthwaite, Citation2020) often means that instructors teaching such a subject will deliver courses that reflect their personal experience with research, either in how they learnt about conducting research or where their particular interests and skills lay.

Like other areas of knowledge that have a large scope in terms of potential content, such as biology and mathematics, subjects that teach research methods face the potential dangers of an overcrowded curriculum and the surface learning that follows (Slavin & D’Eon, Citation2021), adding to problems with understanding research concepts that are common among students (Murtonen, Citation2015). Educators must work out how much to include at the same time as finding an appropriate balance between active and didactic pedagogies that meet the different needs of students (Gunn, Citation2017).

Earley’s (Citation2014) was timely as we had recently taken responsibility for an applied health research subject. The findings of Earley’s review informed the subject re-design and encouraged ongoing reflection of our approach to addressing the challenges that were identified.

1.1. Our approach

Mindful of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory for developing individuals (Fortune et al., Citation2021) a purposeful ecological approach was used to transform the subject with the intention of creating a supportive learning environment. The three main strategies in the approach were to: build a respectful culture; ensure purposeful assessment design; and focus on feedback. The approach was reinforced by encouraging reflective practices and developing an effective approach to teamwork.

Our goals were to address the problems of engagement, perceptions of value and to improve research knowledge through application, akin to John Dewey’s skills-based pedagogy (Kolb & Kolb, Citation2005; Tarrant & Thiele, Citation2016). We focussed on authentic assessments and built workshop activities around these, to show students the value of the skills being taught. These tasks are common to the application of research in practice. Over time we purposefully addressed areas of weakness in student performance and engagement. The core teaching team comprised four public health teaching and research academics who, with other staff teaching the subject, meet weekly over the teaching period. Workshop facilitators necessarily have a research background. This is important as the subject uses an apprentice-style approach. The regular meetings ensure that there is opportunity to share the subject’s philosophy and constructive experiences and ideas (Macpherson, Citation2015). Weekly workshop activities are designed to help students complete three assessment tasks. Two individual assessments are followed by a group assessment. Students are placed in teams in the first workshop to provide peer support and opportunity to work on activities together throughout the semester.

Three authentic assessment tasks (Swaffield, Citation2011) were developed with associated workshop activities. These include: an introductory systematic review; a mixed methods data report; and a group poster based on a guest lecture series. In addition, workshop activities are designed to be student-centred and specifically address areas where students struggle with concepts. The activities aimed to encourage participation by directly relating to the assessment tasks. See, Table for an example of a workshop activity related to an assessment.

Table 1. Workshop activity example: Synthesising exercise

After five years, it was time to consider the lessons that had been learnt from the subject transformation and the process of continuous reflection.

2. Aim and objectives

The aim of this paper is to share our experiences in developing an effective approach to teaching applied health research to undergraduate students.

The objectives in achieving this aim are:

To identify lessons learnt from strategies used to overcome challenges in teaching applied health research at undergraduate level to identify knowledge gained, increase engagement, and improve student perception of value

To develop a conceptual model to guide approaches to teaching undergraduate students.

3. Materials and methods

We used a retrospective mixed method approach to analyse subject indices and feedback across five years.

3.1. Setting and participants

Applied Health Research is an undergraduate research methods subject taught at a large university in Australia. The subject has approximately 200 enrolments per year across different study modes (online and blended). The student cohort is diverse in terms of background and discipline area, although the majority are public health students. The subject runs both as semester long subject (12 weeks) and as a summer intensive (6 weeks).

3.2. Procedure

A five-year retrospective review of the subject responses to annual student and facilitator feedback was undertaken to identify lessons learnt. This involved:

Tabulation and description of all strategies implemented in the subject between 2016 to 2020

Comparison of the mean scores for all items in the student feedback survey (SFS) on the subject and teaching staff from 2017 to 2021

Thematic analysis of all qualitative student feedback on the subject from 2017 to 2021

Thematic analysis of randomly selected student responses to the Week 1 Hopes and Fears reflective exercise

Examination of student performance over time in terms of grade distribution

Content analysis of student reflections in subsequent Third Year placement subject to look at the frequency that Applied Health Research was mentioned as providing useful skills and/or knowledge for the placement.

Integration of literature and lessons learnt to develop conceptual model

3.3. Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained by the Human Research Ethics Committee at La Trobe University (HEC21250) to access and report student feedback data.

4. Results

4.1. Lessons from strategies, feedback and performance

Table shows the timeline for the strategies implemented in the subject between 2016 and 2020. These strategies fall into four main areas: promotion of reflection; feedback and support; purpose-designed tools; and culture building activities.

Table 2. Strategies taken in response to student and facilitator feedback 2016–2020

4.2. Promotion of reflection

Strategies to encourage students to reflect on their work, their learning needs and their progress were fundamental to the subject re-design. Reflection strategies included exercises for students and embedding reflection components into workshop activities and assignments, including in-class exercises and structured evaluations. These strategies also aimed to acknowledge feelings of uncertainty and potential anxiety among students. For example, in the first workshop students identified their hopes and fears for the subject.

The results of these activities were collated and reported back to all students in subsequent sessions, including the final session to encourage further reflection on their achievements.

Reflection activities were important sources of feedback to the teaching staff, who were encouraged to think and discuss student issues, progress and needs in the weekly meetings.

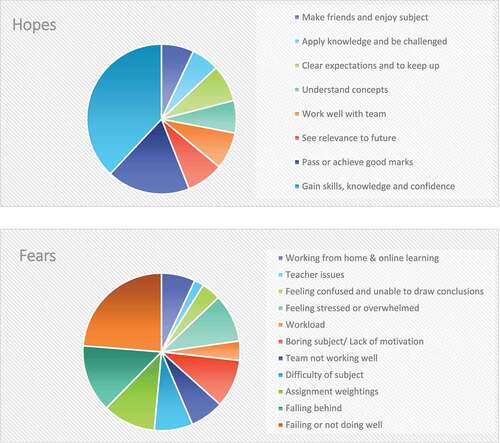

Figure shows an example of the types of issues students raised in the Hopes and Fears activity. Students’ goals (their hopes) and concerns (or fears) for the subject have remained consistent over the past five years and a reminder that students want to do well, are worried about failure and the subject difficulty, and also have social needs.

4.3. Feedback and support

Feedback and support strategies have developed across the subject’s history and included the introduction of assignment tracking points, weekly progress guides, and assignment templates and examples.

These strategies have created ongoing feedback to both students and workshop facilitators throughout the subject allowing timely responses to perceived challenges, such as gaps in students’ knowledge and understanding. The strategies have also encouraged students to articulate their needs and given them clear ownership of their learning. Examples of these strategies include the introduction of voluntary “tracking points” where students can submit key aspects of an assignment for early feedback and the allocation of marks to reflective practice activities following assignment submission.

The tracking point was great!! Definitely keep doing that! It helped me to understand what I need to improve on and I was actually able to improve before I was graded! That is so great so many subjects don’t do this and should!!! (2020)

4.4. Purpose designed tools

Purpose designed tools included strategies to help students overcome sticking points and clarify the need for these skills and knowledge in research. These included the development of a Quality Appraisal Tool, a revised PICO exercise, a paraphrasing exercise and the inclusion of an assumed knowledge section and short videos explaining the assignments.

Critical to considerations of student needs were purposeful attempts to address barriers to completing the assignments by adjusting resources and activities to meet students’ needs based on their feedback and performance. For example, initially students struggled to develop a research question using the PICO mnemonic (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome), delaying progress to other more critical tasks in the assignment, so a workshop exercise was devised comprised of suitable PICO-based questions. Similarly, the addition of the assumed knowledge section allowed students to easily review content from previous subjects by facilitating access to it.

Progressing through the assignment each week with tools to help us achieve parts of the assignment were very helpful (2020)

I really liked that all the workshop activities were relevant to what the assignment required and really made the processing of doing the assignment easier. Every aspect of the assignments was made clear and assistance was provided whenever needed. I enjoyed that the lectures were also linked with an assignment so it didn’t feel burdensome (2017)

4.5. Culture building activities

Culture building activities were largely student-focused strategies. These included changing the weekly lectures to Question and Answer (Q&A) sessions focussing on student questions, adding a section to the subject online site introducing the workshop facilitators, and discussions in the weekly staff meetings.

The shift from the traditional one-hour weekly lecture to a weekly Q&A session was the culmination of shift to an increasing focus on what the students wanted to know and where their particular interests lay. The Q&A sessions covered questions students raised in the preceding week (or had raised in previous years about assignments). All sessions were recorded, and with the use of Microsoft Stream, transcripts were readily available (Mercurio, Citation2018; Mercurio & Merrill, Citation2021). The subject analytics showed that they were used regularly by students.

The Q&A sessions were helpful in that they provided a brief but clear overview of the assessments and expected work for the subject and allowed the students to ask questions (2020)

The workshop facilitator profile section ensured that the students had access to information about their teachers and how they could support them. From the outset, weekly staff meetings were held to discuss both practical issues and educational philosophy. Aside from promoting reflection, the meetings also encouraged a focus on student learning needs and acknowledgement of their intersectional identities.

On reflection, several strategies that we instigated were clearly linked in terms of our stated goals for the subject; increased engagement will occur when perceptions of value improve. We now see that the way to improve both engagement and perceptions of value is to build a respectful culture. Importantly, while assignment topics changed regularly, the teaching goals and assignments for the subject did not change over the years.

4.6. Impact of the strategies employed

The impact of the different strategies implemented across the subject can be seen in students’ knowledge and in the formal feedback that they gave.

The quality of student work improved consistently across all workshop groups as indicated by grades awarded, particularly the reduction in the proportion of fail grades. The distribution of grades shifted favourably upwards over the years, for example, A and B grades in 2017 were 10.4% and 30.1% respectively. In 2020, these increased to 17.1% and 43.7%.

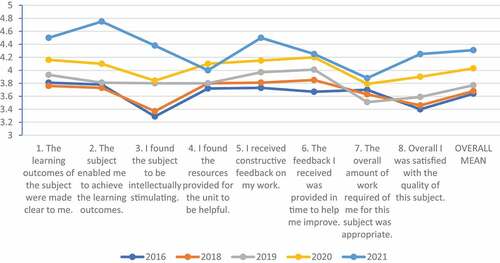

The consistency of assessment grading over this period was confirmed by an external reviewer provided through the Innovative Research Universities (IRU) Academic Calibration Program in 2019 (IRU, n.d.-a; IRU, Citationn.d.-b). Student Feedback on Subject (SFS) scores improved markedly over the period, from an overall score of 3.64 (out of 5) in 2016 (response rate = 45.8%) to 4.07 in 2020 (41.8%) and 4.31 in Term12021(32.0%; see, Figure ).

The workshop facilitators, all experienced in mixed methods research, engage positively with students. Student Feedback on Teaching (SFT) scores for the three primary workshop facilitators has consistently exceeded 4.5 (out of 5) since 2017. The importance of the teaching team was highlighted when there was a sudden loss of an experienced facilitator at short notice in 2018, as shown by the SFS drop that year.

Analysis of student qualitative feedback over the period 2017 to 2020 reinforces the approach that was taken. There was significant support for several aspects of our approach, including: the alignment of workshops with assessments; positive feedback on workshop facilitators; the value of ongoing feedback; and recognition of knowledge gained in terms of research and research skills. Students also valued the support resources and the tracking points. There is also recognition of the knowledge gained. For example, in the following student feedback:

I found this subject challenging and rewarding. Grappling with the first two assignments gave me a deeper understanding of health research (2018)

Developing skills in writing research reports. The subject taught me that I am actually capable of creating detailed, high quality work; which I often doubt of myself. This is the main reason that I quite enjoyed this subject. (2017)

Importantly, the impact of the subject appears to be sustained over time. Analysis of 125 student reflections in a subsequent subject found more than half (56%) acknowledged skills and knowledge that they gained from the applied health research subject to be helpful to their placement experience. Three connecting key themes associated with Applied Health Research were evident in these reflections: skills gained, preparation for placement; and building confidence.

Several students identified a range of skills that they had gained in the subject, Applied Health Research. One student wrote:

I have developed the skill of identification of appropriate keywords/terms, proposal and conduct a literature scoping review, interpreting the results, reporting statistical results, analysis data, and summarizing the information.

Several students identified skills associated with writing, including “academic language and following of writing a structured report” and writing for different audiences, as one student reported:

I thought back to [Applied Health Research] which required me to translate statistical information into accessible English. I took the same approach and translated my academic style into a simplified style to ensure it had the clarity and accessibility required.

Students associated the skills they had learnt in the subject with feeling prepared for their internships, including those that did not expect this:

4.6.1. Through studying [applied health research] I felt much more prepared and ready to begin researching methods

Due to one of the projects being based around a lot of research, I found myself using skills that I’d learnt … . Honestly, I thought that I would never have to do research again, as I really don’t find it enjoyable, however because I knew what I was doing, I was able to somewhat enjoy it and help out as best as I could.

Several students wrote about the confidence they had gained through what they had learnt in the subject:

Recalling what I have learnt … helped me develop my confidence as I had a clear idea of the expectations needed to complete the report, as well as having undertaken an introductory-level systematic review had boosted both my self-esteem and my motivation, having an understanding of what is required to produce a report that may eventually be published have definitely put my mind at ease allowing me to put the knowledge I learnt and I acquired into the report.

This previous knowledge assisted me greatly in completing my placement task and provided me with confidence to produce a high-quality standard literature scoping review.

5. Conceptual model

The findings of this review can be described as a conceptual model (see, Figure ). Strategies were built around three key goals which form the backbone of the approach: to build a respectful culture; to ensure purposeful assessment design; and to focus on feedback.

A respectful culture acknowledges the intersectional identity of students and academics, and importantly, that students are adult learners, responsible for their own learning. With this perspective, it makes sense to focus on what students want to know that facilitates their learning. The attitudes and capabilities of workshop facilitators is critical to this understanding.

Authentic assessments are an easy way to ensure purposeful assessment design. Giving students the opportunity to complete tasks like those they will face in the workplace quickly address questions of “why do I need to learn about research?’. An emphasis on translatable skills, which are plentiful in research projects, helps to make sense of activities for students who do not anticipate a research career. Authentic tasks with currency can enhance engagement. Authentic assessments also means that assessment can become central to learning, and workshops can be built around them.

A focus on feedback encourages responsive approaches to student needs. Integrating feedback—both formal and informal—into activities and assessments, facilitates ongoing dialogue between students and teachers.

These goals are supported by encouraging reflection, by both students and teachers, and using teamwork effectively to facilitate learning.

I would have to say that the way this subject is structured for students to learn is one of the best I have encountered. The workshops allowed for deeper learning (2018).

I liked the variety of different areas of applied research which was covered in this subject. I learnt so much despite already doing research, data and statistics subjects in the past! (in previous subjects or courses) (2020)

5.1. Discussion

This five-year retrospective review describes a model for teaching research methods to students when there is poor understanding of the value of research. The addresses existing gaps in the literature (Earley, Citation2014) in terms of how to report what students learn from research methods courses and how to assess them.

Key to our approach was building a respectful culture, ensuring purposeful assessment design and focussing on feedback. These strategies were supported through the effective use of reflection and teamwork. This was a developmental and gradual process that changed the environment of the subject over time. This impact can be viewed as the effect of the interactions of proximal processes (the strategies used) on student microsystems (student experiences in the subject) and the meso-system (teaching academics), which Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model considers critical to human development (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977). Similar approaches in the literature often need to be inferred as few studies have made these links to Bronfenbrenner or other pedagogical theories but rather focus on practical aspects of teaching. One example is the research teaching program for South African medical students described by Knight et al. (Citation2016). In this program, the teaching strategies involve students undertaking “real research” projects in small groups. The study reports positive student experiences relating to learning about research processes. Student perceptions of research experience and understanding is higher compared with those in lecture-based courses. Students also reported that the reflective practice incorporated into the program improved their understanding of personal strengths and weaknesses. Again, while the meso-system is not explicitly mentioned, the authors refer to the challenge of finding sufficient suitably qualified faculty supervisors and the pressures of preparing the programs assessment materials within the academic timeframes (Knight et al., Citation2016).

5.2. Building a respectful culture

The weekly discussions meetings helped to promote mutual understanding of the educational philosophy of the subject which acknowledged the importance of personal agency and recognised students as adult learners. The inclusion of staff profiles raised awareness of the research experience in the teaching team to the students and demonstrated the team approach in the subject. On reflection, these strategies fostered a “cognitive apprenticeship model” where the role of the academic teaching staff is to guide students and model through demonstration, which follows those processes through which learning occurs (Denner & Burner, Citation2000). A recent systematic review to assess the effectiveness of strategies teaching evidence-based practice to health students (Ramis et al., Citation2019) identified 28 studies, three of which acknowledged the impact of role modelling in helping students understand the complexities of applying evidence to practice. Of these three studies, Kim et al. (Citation2009) compared standard teaching approaches to a program requiring nursing students to apply principles and processes taught at an introductory seminar to professional practice problems. Students worked successfully in groups to identify such problems and synthesize potential solutions from the available evidence. While the authors did not explicitly describe this approach as building respectful culture, the program can be viewed this way, as students were recognized as adult learners; students were engaged and guided in research tasks relevant to their professional goals. Ensuring purposeful assessment design

Authentic assessments can be an effective way to demonstrate that students are able to complete the types of tasks, particularly with the use of real-world relatable topics for which the subject intends to prepare them (Kolb & Kolb, Citation2005). A successful element of this subject was aligning the workshops to the assessments which ensured that students were shown how to achieve the intended learning outcomes. This aspect of the subject was highly valued by students, as it helped them learn about research, supported their time management, and allowed timely clarification of complex aspects of the assessment tasks. Student feedback shows that it was critical in building confidence and a sense of preparation in the subsequent placement subject. As one student said:

I would have to say that the way this subject is structured for students to learn is one of the best I have encountered. The workshops allowed for deeper learning.

Working within the same teams each week built social connections and enabled students to explore different perspectives and think more broadly when undertaking their individual assessments (Macpherson, Citation2015).

5.3. Focusing on feedback

The ongoing cycle of feedback in the subject facilitated dialogue between students and academics and acknowledged the specific needs of each student cohort. Students and staff could see that their issues were addressed, which encouraged engagement and self-regulation. The development focus of the continuous feedback throughout the subject has been shown to deliver long-term benefits to students (Palmer-Brown et al., Citation2016).

Reflection on feedback and performance also helped to build purpose-designed tools that led to better focus on the purpose of the assignments by reducing issues that impeded progress but were unrelated to the subject’s goals, for example, developing the critical appraisal tool, which aimed to reinforce understanding of the purpose of critical appraisal, and which has been adopted for use in other subjects.

We have been able to apply the lessons learnt from our evaluation of this subject, including the conceptual model, to the design of new subjects and to improve existing skill-based subjects that do not have the same research focus.

5.4. Conclusion

Lessons from our experience may offer useful guidance to others experiencing similar issues, something not available to us when our journey with this subject started. We suggest that our conceptual model, which involves building a respectful culture, ensuring purposeful assessment design and focussing on feedback, can be used to inform evaluation processes and the design of research and other skill-based subjects.

Acknowledgements

Student feedback has been so important and comments like “I learned so much about research and myself as well (2021)” have inspired us and the approach we have taken. We’d like to acknowledge all students and academic staff who have worked with us on this subject over the years, and Dr Susan Chong who provided access to student reflections in her third-year subject.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dell Horey

Dell Horey is an associate professor in public health and Course Design and Curriculum Advisor for the Faculty of Science Agriculture Business and Law in the University of New England, Australia. She also has an adjunct role in the Department of Public Health, La Trobe University. Her research activity in public health is concerned with influencing the care of vulnerable people, particularly parents of stillborn babies. Her educational research focuses on quality and leadership in learning and teaching environments.

Fernanda Nava Buenfil

Fernanda Nava Buenfil is a lecturer in the Department of Public Health at La Trobe University, Australia. Her public health research focuses on body image in high-needs groups, particularly culturally and linguistical diverse populations. Her educational research aims to improve student outcomes and learning experiences through effective engagement strategies and self-reflection.

Joanne Marcucci

Joanne Marcucciis a lecturer in the Department of Public Health. Scott Ruddock lectures in the Department of Psychology.

References

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 515–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

- Dennen, V. P., & Burner, K. J. (2008). The cognitive apprenticeship model in educational practice. In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. van Merrienboer, & M. P. Driscoll (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology: A project of the association for educational communications and technology (3rd ed., pp. 425–439). Routledge.

- Earley, M. A. (2014). A synthesis of the literature on research methods education. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(3), 242–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.860105

- Fortune, T., Nicolacopoulos, T., & Horey, D. (2022). Conceptualising and educating for global citizenship: the experiences of academics in an Australian university. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(4), 1089–1103. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1882960

- Gunn, A. (2017). Critical debates in teaching research methods in the social sciences. Teaching Public Administration, 35(3), 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739417708837

- Innovative Research Universities (IRU) (n.d-a) Academic Calibration program. IRU. https://www.iru.edu.au/iru-work/calibration/

- Innovative Research Universities (IRU) (n.d.-b) Calibrator Guide: Information for reviewers in the academic Calibration process. IRU. http://www.iru.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/IRU-ACP-Calibrators-guide-v2.1.pdf

- Kim, S. C., Brown, C. E., Fields, W., & Stichler, J. F. (2009). Evidence‐based practice‐focused interactive teaching strategy: A controlled study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(6), 1218–1227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.04975.x

- Knight, S. E., Van Wyk, J. M., & Mahomed, S. (2016). Teaching research: A programme to develop research capacity in undergraduate medical students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Medical Education, 6(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0567-7

- Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(2), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.17268566

- Macpherson, A. (2015). Cooperative learning group activities for college courses. Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

- Mercurio, R. (2018). Stream. In beginning office 365 collaboration apps (pp. 235-255). Apress.

- Mercurio, R., & Merrill, B. (2021). Welcome to Microsoft 365. In Beginning microsoft 365 collaboration apps: working in the Microsoft Cloud (2nd edition) (pp. 3-27). Apress.

- Murtonen, M. (2015). University students’ understanding of the concepts empirical, theoretical, qualitative and quantitative research. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(7), 684–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1072152

- Nind, M., & Lewthwaite, S. (2020). A conceptual-empirical typology of social science research methods pedagogy. Research Papers in Education, 35(4), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1601756

- Palmer-Brown, D., Cai, F. F., & Patel, P. (2016). Classifying and evaluating assessment feedback practices. Proceedings of ICERI 2016 conference, 6495–6506, https://repository.londonmet.ac.uk/3896/1/ICERI-2016.pdf

- Ramis, M. A., Chang, A., Conway, A., Lim, D., Munday, J., & Nissen, L. (2019). Theory-based strategies for teaching evidence based practice to undergraduate health students: A systematic review. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1698-4

- Rubenking, B., & Dodd, M. (2018). Project-versus lecture-based courses: Assessing the role of course structure on perceived utility, anxiety, academic performance, and satisfaction in the undergraduate research methods course. Communication Teacher, 32(2), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404622.2017.1372588

- Slavin, S., & D’Eon, M. F. (2021). Overcrowded curriculum is an impediment to change (Part A). Canadian Medical Education Journal, 12(4), 1. https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.73532

- Swaffield, S. (2011). Getting to the heart of authentic assessment for learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18(4), 433–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2011.582838

- Tarrant, S. P., & Thiele, L. P. (2016). Practice makes pedagogy–John Dewey and skills-based sustainability education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 17(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-09-2014-0127