Abstract

This paper documents the endline findings and lessons learned from the “Advancing Learning Outcomes and Transformational Change (ALOT Change) program whose goal was to secure the future of adolescent girls and boys aged 12–19 in two urban informal settlements in urban Nairobi. The purpose of the paper was to explore what were the key endline findings and lessons learned from the ALOT Change program, which was a community-based intervention targeting girls and boys in urban informal settlements of Nairobi. Data were from the endline evaluation of the program conducted in July-August 2018, and program implementation documents between 2013 and 2018. The impact of the program was on life skills, learning outcomes, and leadership skills. One of the key lessons learned was that there is value in the implementation of integrated approaches, which systematically bring together multifaceted components of interventions. This reduces inefficiencies and enhances the impact.

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of education and educational interventions

Education is seen as key to developing an economically successful society (Deng & Gopinathan, Citation2016). More recently, there has been increased recognition of the need for education systems to prepare children and young people for life in an increasingly complex and technical world (Priestley et al., Citation2017)—and build in them the so-called 21st Century competencies. Therefore, the definition of academic success has shifted from mastery of specified content knowledge to the promotion of core competencies such as confidence, self-directed learning, active contribution, and the ability to show concern (The Ontario Public Service, Citation2016). Interpersonal and intrapersonal competencies which have gained as much importance as cognitive competencies are therefore critical for all students as they impact several areas of life including educational attainment, relationships, health, and wellbeing.

Educational interventions that focus on specific aspects of functioning such as life skills effectively reduce problem behaviors and enhance positive aspects of behavior (Botvin et al., Citation2003). For instance, psychosocial interventions focusing on life skills education which strengthen coping strategies and enhance critical thinking skills promote the positive social and mental health of adolescents (Prajapati et al., Citation2017; Yadav & Iqbal, Citation2009). Such interventions equip students with the necessary skills to navigate the complexities of their life situations and empower them to become fully functioning contributors to their societies. The demonstrated impact of these interventions suggests that programming that seeks to improve outcomes for adolescents and youth should cut across the school, home, and community. Adolescents and youth living in disadvantaged settings are likely to be at higher risk for negative outcomes and therefore more likely to benefit from interventions that provide opportunities for dialogue and supportive environments.

In the Urban informal settlements of Nairobi, the bulk of the evidence from the education research at the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) pointed to a bleak situation in terms of education outcomes for girls in urban informal settlements. For instance, the APHRC longitudinal study conducted in 2009–2010 showed that children who resided in poor households within urban informal settlements were less likely to transition into secondary school after eight years in primary school. A comparison of the data by household wealth showed that about 52 percent of children in the bottom wealth quartile transited to secondary school as compared to about 61 percent in the top wealth quintiles. Overall, the transition rate for pupils residing in the urban informal settlements of Nairobi was 59 percent, compared to 88 percent transition rate for pupils in non-slum areas. In addition, research evidence also shows that 47 percent of school-going children, including girls, in urban informal settlements in Kenya (with 63 percent in Nairobi) attended non-state primary schools (Ngware et al., Citation2013). Such schools are ill-equipped in terms of resources for school and the teachers in the schools are not well-trained to teach. Moreover, girls in urban informal settlements are more likely to be subjected to negative social behavior such as incest, sexual and physical abuse, rape, early pregnancies, and early marriage. Evidence suggests that one in eight girls is married by the age of 15 in sub-Saharan Africa. This is happening against the backdrop of education being shown to be an effective tool for averting child marriage and early birth (UNESCO, Citation2013). It is against this backdrop that APHRC in consultation with the stakeholders sought to improve the transition of girls to school in the initial Phase I of the program, included the boys in Phase II of the program and followed a cohort into secondary school in Phase III of the program. The objective of this paper was to establish the lessons learned from the implementation of the ALOT Change program while highlighting the endline findings of Phase II of the program. Therefore, the study seeks to answer one main question: What are the key endline findings and lessons learned from the ALOT Change community-based intervention targeting girls and boys in urban Nairobi?

2. Literature review

2.1. The importance of focusing on adolescents

Adolescence is one of the most rapidly changing phases of human development. This period is characterized by the development of knowledge and skills, as well as the acquisition of attributes and abilities important for enjoying the adolescent years and the entire lifespan (Blum et al., Citation2014, Citation2019). As much as this stage is characterized by positive development, it is also a period of vulnerability to high-risk behavior and experimentation, well understood as being normative rather than pathological (Abuya et al., Citation2017; Beloe & Derakshan, Citation2020; Blum et al., Citation2012; Kabiru et al., Citation2012).

A most recent census indicates that the majority of the Kenyan population comprises the youth who represent the future of the country; 43 percent of the population is aged below 15 years. In Nairobi, 2.5 million slum dwellers, about 60 percent of the city’s population, live in 200 informal settlements which occupy only 6 percent of the available land. These figures show the severity of congestion in urban informal settlements (APHRC, Citation2014a). Furthermore, there is a high concentration of youth and children in the city, making it hard to provide shelter, education, and employment opportunities (APHRC, Citation2014). These challenges—limited access to education and employment opportunities, inadequate shelter provision, and unstable social contexts are exacerbated by poverty, pushing young people to engage in problem behaviors (Abuya et al., Citation2015b). In recent times, the visions and aspirations of young adolescents seem to be beyond their reach, resulting in frustration and anger (Barakat (Barakat & Urdal, Citation2009). Adolescents need to be fully supported in this phase of life for them to attain their life’s potential. For this reason, the study focuses on this vulnerable group of boys and girls aged 12–19 years to highlight the findings for the endline and document the lessons learned during implementation.

2.2. Review of the implementation of the interventions in other contexts

In the context of India, (Banerjee et al., Citation2007) found that when women were engaged to support young women in an urban community to provide after-school support to improve low-performing students’ learning. As a result of this support, test scores of girls in schools that were part of the program improved by 0.14 standard deviations in year 1 and 0.28 in year 2. The Berhane Hewan Project, in rural Ethiopia, targeted both unmarried and married adolescents aged 10–19 years. The girls had community mentors and were provided with economic incentives to remain in school, and information on reproductive health. This program resulted in the decrease of ever-married adolescents by 8%; none of the 10 to 14-year-olds had gotten married, and they remained in school (Erulkar & Muthengi, Citation2009). Thus, community interventions can prolong schooling for adolescent girls. In the context of North America, multi-component programs had instituted four distinct structures and programs that included; an array of enrichment opportunities, opportunities for skill building, intentional relationship building, an experienced leader supported by experienced staff, and an administrative, fiscal, and professional-development support of the sponsoring organization (Birmingham et al., Citation2005). In Kenya, Duflo et al. (Citation2011) through an evaluation of a program that hired extra teachers with the same qualifications as regular teachers, but on a one-year contract at a quarter of the regular salary, and found that those teachers on the contract were more likely to be teaching than the regular teachers. In Bangladesh, stipends provided to girls increased their enrolment at the secondary level by between 43% to five-fold, thereby reducing the gender gap in access; in some areas, and as such girls outnumbered boys in secondary school (Mahmud, Citation2003). Moreover, research evidence also established that community-based after-school programs that sought to improve the personal and social skills of children and adolescents showed that, in comparison to those that did not receive the intervention, the participants manifested compelling increases in academic achievement, reduced problem behaviors, positive social behaviors, bonding with peers in school, and improved self-perceptions (Dulark et al., Citation2010). The research evidence that is documented here shows that the afterschool programs have been effective in improving academic outcomes, the likelihood of girls deferring adverse sexual and reproductive outcomes, and offer opportunities for skill building. Moreover, in some of the programs that worked with teachers on contract, the learning of adolescents improved compared to the outputs from regular teachers. While stipend programs as is the case of Bangladesh improved the transition rates for girls. In these programs, the lessons learned were not explicit, especially on what was learned from the various implementation, albeit the fact that the findings speak to very rigorous evaluations. As part of the ALOT Change Program, we embarked on documenting the lessons learned throughout the program evaluation. To contextualize the lessons learned this paper also documents the endline findings of Phase II of the ALOT Change Program.

2.3. The context of the study

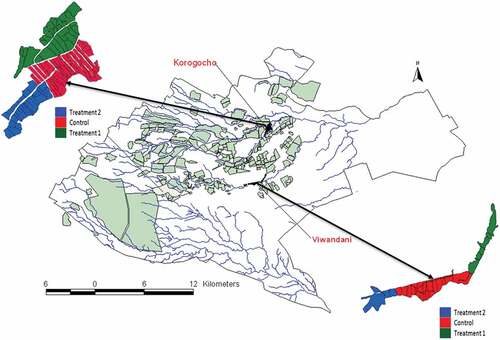

The Advancing learning outcomes and transformational change (ALOT Change) was implemented and subsequently evaluated in the two urban informal settlements of Korogocho and Viwandani on the outskirts of Nairobi, Kenya. The two settlements had different socio-characteristics with respect to their inhabitants which provided a good basis for ascertaining the impact of the program. For instance, the population in Viwandani has higher levels of education and employment, higher mobility of residents who move in and out of the slum area, and household members who live separately while in Korogocho the population is relatively more stable with more families residing together in one household (APHRC, Citation2002, Citation2014).

2.4. The ALOT Change intervention

The ALOT-Change project was a six-year program whose goal was to increase efforts towards securing the future of children in urban informal settlements by improving learning outcomes, transition to secondary school, leadership skills, and social behavior among girls and boys aged 12–19 years who live in urban informal settlements. The objectives of the evaluation conducted by the APHRC included: 1) establish whether there is a differential effect of the proposed intervention on learning outcomes and transition to secondary school between boys and girls in Korogocho and Viwandani; 2) examine whether mentoring in life skills impacts differently among girls and boys in terms of positive behavior, aspirations, interest in schooling and self-confidence; 3) establish the impact of leadership skills training on various outcomes (learning outcomes, role modeling, taking up leadership) among boys and girls in the study communities; and 4) establishing whether the parental sensitization component of the intervention increases parents’ and community leaders’ support towards children’s education in Korogocho and Viwandani. To achieve the outcomes, the study implemented an afterschool support and life skills mentorship program, providing subsidies, exposing parents to guidance and counseling, and exposing girls and boys to opportunities to enhance their leadership skills.

2.5. Why the leadership component was added in Phase II

In Phase II of this study (2016–2018) the leadership component was added as part of the interventions. This was motivated by the fact that children born in slums were more likely to face complex life challenges which required greater resilience to cope with the adversity that household poverty and poor physical and social environments present to them. Although the pilot phase (Phase I) built effective communication between parents and girls, to build an academically supportive relationship, this was not sufficient to strengthen the young people’s ability to function effectively in their environments. If young people can positively cope with the hardships of life in the slum settings, they can be empowered to become transformative leaders who are champions of change. Consequently, they can lead positive changes in their communities (Kabiru et al., Citation2013).

2.6. The inclusion of boys in phase II

Boys were also included in Phase II of the intervention (2016–2018). The inclusion of boys was motivated by the harsh conditions of life in the slum which affected the primary school completion and transition to secondary school, for girls and boys from poor and disadvantaged households in a relatively similar manner. As such, many boys among the urban poor were also missing out on the opportunities that secondary education offers. This plight of boys was continually highlighted during community conversations in Korogocho and Viwandani, at the Partnership to Strengthen Innovation and Practice in Secondary Education (PSIPSE) regional meeting held in Nairobi in March 2014, and in the subsequent global meetings that followed. Moreover, data from the Ministry of Education (MoE) in 2012 showed that the secondary school transition rate for girls was 69.1 percent, which was five percentage points higher than that of boys (MoE, Citation2012).

The argument for the inclusion of boys was further reinforced by the need to appreciate their immense power and authority as key decision-makers within the African social context (Isiugo-Abanihe, Citation2003). Phase II of the project (2016–2018) focused on both boys and girls who were vulnerable. The inclusion of boys provided them with an opportunity to participate in the sessions, aspire for post-secondary education, and thereby reduce their vulnerability to involvement in crime and other delinquent practices. In this way, both girls and boys were provided with the opportunity to complete primary school and make a transition to secondary school and were empowered as young leaders to lead positive changes in their respective communities.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Design

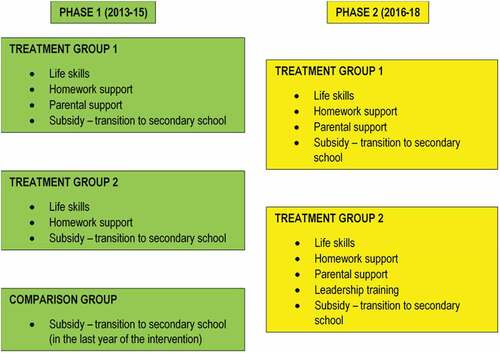

The design of the program both in the pilot phase (Phase I) and was quasi-experimental, and focused on two urban informal settlements of Korogocho and Viwandani (see, ). In Phase I, there were two treatment groups and one comparison group in each of the two urban informal settlements. The geographical locations of the three target areas were purposively selected within each of the two slums in such a way as to minimize contamination. In so doing, the two treatment groups and one comparison group were randomly assigned to the enumeration areas in each of the two slums (see, Figure ). Treatment group 1 was exposed to the following components: (a) mentoring in life skills; (b) afterschool homework support in literacy and numeracy; and, (c) parental counseling. Treatment group 2 was exposed to components (a) and (b; Abuya et al., Citation2014). In addition, the two treatment groups, together with the comparison group received a secondary school transition subsidy in the last year of the intervention. The first phase only targeted adolescent girls in primary school grades 6–8.

In the expanded phase (Phase II) from 2016 to 2018, the evaluation still adopted a quasi-experimental blocked design in the two urban informal settlements. Given the successes of the initial phase, Phase II was scaled up to include both adolescent boys and girls and a leadership component. The urban informal settlement of Viwandani was randomly selected to have the leadership component which included facilitated sessions to impart knowledge on the various leadership concepts, exposure visits, and motivational talks (Abuya et al., Citation2017, Citation2015b).

4. The interventions

4.1. The intervention components and model

To maximize the impact of the intervention, the study adopted a multipronged approach with five components: After-school homework support in literacy and numeracy; mentoring in leadership skills; mentoring in life skills; guidance and counseling of parents; and, primary to secondary school transition subsidy (Figure ). The treatment one (T1) group in Korogocho received the full package of the intervention as had been implemented in the pilot phase (afterschool support in literacy and numeracy, guidance and counseling of parents, mentorship in life skills, and the transition subsidy). The treatment 2 (T2) group in Viwandani received the T1 package, in addition to the leadership component.

Figure 3. Citation2016The Allocation of intervention in the two Urban Informal Settlements in Nairobi

4.2. The intervention’s theory of change

Theory-driven evaluation is a set of methods that focus on how and why programs work and thereby be able to evaluate these programs (Breuer et al., Citation2016; Funnell & Rogers, Citation2011). Programs are a group of activities organized in a specific way or sets of interventions that are supported by certain resources that have been designed to achieve a particular result (Control & Prevention, Citation2011). Initially, the theories are made explicit and are then used to illuminate how the particular program theory leads to the intended outcomes (Breuer et al., Citation2016). Our theory of change for the program was that if behavioral, psychosocial, academic, parental engagement, leadership, and economic barriers to education are addressed, it would translate into improvements in socio-emotional outcomes, numeracy and literacy skills, parental involvement, leadership skills, and transition to secondary school. In creating this change, this program proposed a multifaceted but targeted intervention that included mentoring in life skills, after-school homework support, guidance and counseling of parents, mentoring in leadership skills, and provision of financial support for schooling. These interventions were premised to be implemented on both girls and boys to establish the impact on both gender.

4.2.1. After-school support with homework in literacy and numeracy

This component of the intervention sought to support girls and boys with their homework in literacy and numeracy to improve their learning outcomes. This support was provided through community-based positive role models, who had completed secondary education and scored a mean grade of C+ or above. The motivation for the afterschool support with homework within the community setup was that parents were rarely at home and even when they were available, there was no space in the crowded houses for their children to do their homework. The program provided a safe alternative meeting place after school hours. These sessions were held twice a week, one for numeracy and the other for literacy for three weeks a month. Each session lasted for at least one hour.

4.2.2. Mentorship in life skills

This component involved mentoring adolescents on life skills to assist them to overcome the challenges of growing up and transitioning to becoming responsible adults. These skills also give pupils the requisite coping strategies to counter the emerging demands and challenges of their daily lives. The skills imparted include values, self-awareness, and self-esteem, avoiding negative peer influence, relationships, HIV/AIDS, effective communication, effective decision-making, career goals, and sexual and reproductive health. In each year of the intervention, 12 life skills mentorship sessions are held at an average rate of one session per month.

4.2.3. Mentorship in leadership skills

This component of the program which focussed on leadership skills incorporated talks and role modeling by accomplished leaders, as well as exposure visits to various institutions to enable pupils to interact with the leaders in their usual environments of work. Leadership sessions were held as follows: six facilitated sessions conducted by project mentors; talks by accomplished leaders held once every quarter preferably during school holidays, and exposure visits held once a year. The leadership component was expected to empower young people to provide transformative leadership in their respective communities.

4.2.4. Primary-to-secondary transition subsidy

Under this component, adolescent girls and boys who scored 250 marks and above out of a possible 500 marks on the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) examination were awarded financial support of about USD 113 to subsidize the cost of joining the first grade of secondary school. Public secondary schools use KCPE examination scores as the selection criterion and those pupils who score highly in the examination are admitted to top, highly competitive public secondary schools in Kenya. Such schools are usually costly and parents from the slums cannot afford them. Cushioning parents by offsetting some of these overhead costs was, therefore, important to realize the goal of enabling pupils to make the transition to secondary school.

4.2.5. Guidance and counseling of parents

This component targets parents of boys and girls enrolled in the project to encourage them to get involved in their children’s lives and education. Parents are sensitized to understanding their role as parents; understanding their children; effective communication with their children; sexual and reproductive health; positive aspirations; providing psychosocial support to their children; and, parenting in the digital era. (See, Figure ).

4.3. Study sites and participants

Phases I and II of the ALOT-Change program were implemented in the two urban informal settlements of Korogocho and Viwandani in Nairobi, Kenya. Between 2013 and 2015 (Phase I), the program participants were adolescent girls, their parents, and community members and leaders, whereas between 2016 to 2018 (Phase II), boys were incorporated as program beneficiaries (Abuya et al., Citation2017). The studies were nested within the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS) run by APHRC. The NUHDSS tracks more than 60,000 people; 57% and 43% are from Viwandani and Korogocho urban informal settlements, respectively. As of May 2015, NUHDSS had tracked a population of about 63,000 individuals in about 25,000 households. An analysis of the NUHDSS population aged 15 years and above shows that 6% of the population has no education at all, while 35% has attained at least secondary education. Comparison by sex showed that males have higher chances of having attended school compared to females. Eight percent of females and 4% of males have no formal education, whereas 27% of females and 35% of males have at least secondary education. To get participants for Phase 2, a list of 824 pupils who were in grade 5 in 2015 (expected to be in grade 6 in 2016) was generated from the NUDSS database, followed by a field confirmation on the schooling and grade status. The eligible pupils were recruited into the study, exposed to the intervention, and followed prospectively for a period of three years. Once recruited, even if a student repeated a grade, they were still eligible. Their parents were also recruited to participate in parental counseling on the sensitization arm of the intervention. At baseline, the target population of pupils was 824, i.e. 424 in Korogocho and 400 in Viwandani. However, the follow-up population was reduced to 686 at the midline (335 in Viwandani and 351 in Korogocho) as several learners were not reached for data collection at baseline for various reasons (Abuya et al., Citation2016). The final endline sample consisted of 653 out of the 686 that participated in the midline phase.

4.4. Study tools

The study tools for Phase I and Phase II were largely the same, apart from the leadership questionnaire that was an addition in Phase II. With the inclusion of boys in Phase II, the qualitative design of the focus group discussions (FGDs) was slightly altered. The FGD groups were constituted as follows in recognition of possible gender differentials: fathers with girls in the program; fathers with boys in the program; mothers with girls in the program; and, mothers with boys in the program. A brief description of the ALOT Change survey and qualitative tools used is provided in the section that follows:

4.4.1. Individual schooling update questionnaire

This questionnaire solicited information on the pupils’ schooling history and attendance. The information included the type and location of the school, absenteeism from school, change of school, repetition, and extra tuition.

4.4.2. Individual behavior and life skills questionnaire

This questionnaire collected data on pupils’ educational goals and aspirations, self-confidence, behavior (substance abuse, sexual activity), source of information on sex, drugs, smoking, and alcohol, knowledge about HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In addition, the tool also looked at myths about puberty, sex, and HIV/AIDS.

4.4.3. Leadership questionnaire

This questionnaire focused on six major modules: the social self-efficacy section solicited information on pupils’ ability to relate to and communicate effectively with others; the self-assertive efficacy module collected information on the ability of pupils to speak up for their rights; the self-regulatory efficacy module focused on the ability to resist negative peer pressure; the youth-community connections were concerned with neighborhood support and activities; the social competencies module asked about pupils’ ability to show empathy for others, and the adult-youth connections outside the home and school module which asked questions about whether the pupils had other adults apart from their parents and teachers that they could rely on for any form of support.

4.4.4. Parental and guardian involvement questionnaire

This questionnaire captured data on parental involvement in the education of boys and girls in the community in terms of the provision of resources, checking their homework, and follow-up to know how, where and with whom they spend their time.

4.4.5. Literacy test

This tool was used to evaluate the literacy skills of pupils by testing them on listening, comprehension, reading, writing, and speaking. In addition, the spelling, punctuation, coherence, paragraphing, and handwriting skills of pupils were assessed through a composition exercise.

4.4.6. Numeracy test

This tool was used to assess three learning domains in numeracy: knowledge, comprehension, and application. It focused on the curricular outcome areas of numbers and operations, patterns and algebra, geometry, measurement, and basic statistics.

4.4.7. Parents’ focus group discussion protocol

This protocol was used to elicit discussions around the understanding by parents of their role and that of the community towards supporting the education of their children; the challenges that affect girls’ education in the two urban informal settlements; and the expectations by parents about the impact of the intervention among pupils in the community.

4.4.8. Pupils’ interview guide

This tool sought to investigate: pupils’ understanding of their role and that of the community towards their education; education challenges that pupils encounter in their communities; understanding and availability of role models in their communities; and pupils’ leadership aspirations and ways in which they would transform their communities.

4.4.9. Community leaders’ interview questions

This guide elicited information on community leaders’ understanding of their role and that of the community towards promoting the education of children; the challenges that affect education in the two urban informal settlements; and the state of security within the study communities.

4.5. Data collection

In Phase I, baseline fieldwork activities was conducted from 12 June 2013 to 15 July 2013. Field interviewers visited eligible households to collect data. Eligibility of a household was on the basis that the household had at least one girl who was in grade 6, 7, or 8 and aged between 12 and 19 years. Every eligible household was ascribed code one (1) while non-eligible households were ascribed code eight (8). In the qualitative survey, three different questionnaires were administered to all eligible girls at the household level. Qualitative data collection was guided by a moderator, and the discussion was captured on a voice recorder. In addition, one field interviewer acted as an assistant moderator and took notes during the interviews (Abuya et al., Citation2014). During Phase, I, the midline and endline data collection were conducted in 2014 and 2015 respectively (Abuya et al., Citation2015a, Citation2014)

Similar procedures were used in Phase II in 2016. Quantitative data collection was rolled out for three weeks, from April 14th to May 10th, 2016 for baseline data collection. Complete data were obtained from 329 subjects in Korogocho and 305 subjects in Viwandani, giving a total of 634 girls and boys reached out of the initially targeted 824. The reasons for not reaching all of the 824, who were initially targeted were the unavailability of interviewers, identified participants studying upcountry, and movement outside the demographic surveillance area (Abuya et al., Citation2017). Data collection for the qualitative study was completed between April 26th and May 1st, 2016 where 34 qualitative interviews were conducted: eight focus (FGDs) group discussions with parents, 12 in-depth interviews (IDIs) with pupils, 12 key informant interviews (KIIs) with village elders and two KIIs with chiefs. There was follow-up data collection that was done in 2017 for the midline and in 2018 for the endline evaluation respectively (Abuya et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). At the endline in 2019, a total of 133 participants were purposefully sampled for the qualitative interviews. A total of 30 qualitative interviews were done and were categorized as follows: eight FGDs with 69 parents, 10 KIIs with six mentors and four counselors, eight KIIs with eight community leaders, and four dialogues with 46 grade eight pupils.

4.6. Analytical procedures

The analytical procedures detailed here are specific to those used during the endline evaluation in 2018. Quantitative data analysis: A mix of approaches were used to establish the endline impact of the intervention in 2018. First, descriptive data analysis that included means, frequencies, and percentages was conducted. Chi-square tests and t-tests were used to establish if there were any significant differences in the outcomes of interest across the two study sites. Given that several indicators were measured using various items, we tested for internal reliability and the items were reduced to a single score using Cronbach’s alpha. We used the difference-in-differences (DID) estimator to establish the crude impact of the intervention. Finally, we conducted an intention-to-treat analysis, fitted a regression model, and controlled for observed baseline imbalances. Some of the covariates that were controlled for included baseline scores, type of school, household wealth index, and pupil gender. For detailed descriptions of the approaches used in each of the chapters, to establish impact see, (Abuya et al., Citation2019).

Qualitative data analysis: All the qualitative data were audio recorded during the interviews and thereafter transcribed verbatim into MS Word. A coding schema was generated taking into account the emerging issues from the data (Boyatzis, Citation1998; Crabtree & Miller, Citation1999). NVivo software was used to facilitate the organization of the data. Coding was done both deductively and inductively. Deductive codes were based on the research questions guiding the study and previous studies, while inductive codes were informed by emergent themes from the data. A coding report was generated based on a summary of the data categorized into various themes areas according to the research aims and objectivesFootnote1 (Abuya et al., Citation2019).

4.7. Ethical considerations

The study documents were reviewed internally by the APHRC scientific review committee. We obtained ethics approval from Amref Health Africa’s Ethics and Scientific Review Committee (ESRC). In addition, at all the stages of the research, we received clearance from the National Council for Science and Technology in Kenya (NACOSTI). Informed consent was sought and obtained from all the participants in the study (Abuya et al., Citation2017, Citation2015b, Citation2019, Citation2014).

All participants in the study were assigned a unique computer-generated identifier. Data that was collected over the course of six years was stored in an SQL database on the APHRC server that only the database manager could access. To ensure confidentiality, individual names and locations of residence were anonymized when releasing data to analysts. For the qualitative data, pseudonyms were used for participants in the in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. No names appeared on notes or reports in the case of qualitative narratives. Moreover, information that was provided by adolescent girls and boys was not disclosed to their parents or guardians. Access to data was strictly limited to the project team. Transcribed qualitative narratives were password-protected while audio-recorded information was erased after transcription. Results were aggregated and summarized and did not include names of individual participants or households from which they originated. Additionally, field interviewers and supervisors were trained on ethical issues to ensure that guidance on ethical conduct

4.8. Key findings and lessons learned

We present the findings of the program at the endline from the data which was collected in 2018 during Phase II.

The impact on life skills. There were gains in pupils’ future educational aspirations and goals in both sites at the endline, in 2018 compared to the baseline in 2016. Overall the intervention had a positive impact on the education goals and aspirations of pupils with a DID of 0.104. This impact was larger and statistically significant among girls (DID of 0.145). Moreover, there was an observed significant impact (DID of 0.306) of the intervention on self-confidence among pupils in Viwandani. This impact persisted even after stratifying by gender showing that the intervention impacted equally among boys (DID of 0.316) and girls (DID of 0.301). In terms of parental monitoring, there was improved parental monitoring in Viwandani at the endline (average of 2.59 out of a possible 3) as compared to baseline (average of 2.57 out of a possible 3) with the impact being significant among girls (DID of 0.106). Regarding delinquent behavior, there was no overall effect because of the ceiling effect but, the intervention has a greater impact in reducing delinquent behavior among boys (DID of −0.098) in Viwandani than in Korogocho. Additionally, parents still topped the list of those whom the pupils felt comfortable discussing puberty and sexuality issues with, although there was a slight drop from baseline (46%) compared to endline (43%). A higher proportion of girls (59%) compared to boys (25%) were comfortable discussing sexuality and puberty issues with their parents. These differences were similar to what was observed at baseline. The findings are supported by the qualitative narratives where pupils felt that the communication skills enabled them to be more open to and engage better with their parents. As a result, pupils were able to confide in their parents about issues affecting them.

To reinforce lower proportions of adolescents involved in delinquent behavior, pupils in the program noted that as a result of being taught life skills they became resilient to peer pressure. They were able to do this because of being able to evaluate the consequences of various actions, and they seldom followed their peers blindly. A female pupil from Viwandani said:

“ … If there is someone who was pressuring you to do bad things. We were taught by our mentor … you should stand on your own and let your yes be yes and your no be no. Some wanted me not to attend school on Saturday … to walk around and buy clothes … But I said no and I stuck to my no.” (Dialogue, Female pupils, Viwandani, 06082018)

Impact on learning outcomes. For numeracy, the results indicate that the difference in the mean changes in the performance of the two treatment groups was positive (43.0) and was statistically significant at the 5% level. This implies that the impact of the second treatment (T2) (including a leadership component) on pupil numeracy scores was significantly higher than the impact of the first treatment. The results further show that the double difference between T1 and the comparison group was 33.6 and that between T2 and the comparison group was 76.6 which were both positive and significant at 5% level. This means that both intervention packages helped accelerate pupils’ numeracy achievement and more so the second intervention package which included a leadership component. Moreover, results further show that the gains in literacy achievement among pupils receiving the T1 package (in Korogocho) was (72.7) and for those receiving the T2 package (in Viwandani) was (89.4) and were significantly (at a 5% significance level). These gains were higher when compared to the corresponding gain recorded during the pilot study. This is interpreted to mean that both intervention packages were useful in accelerating pupil literacy achievement beyond what was accomplished by the pilot study, consistent with the numeracy results. In other words, compared to phase 1, there were better scores in numeracy and literacy across the two sites. In addition, the intervention had more impact on boys than girls, especially for numeracy. On the other hand, for numeracy, the intervention packages were seen to have more impact among pupils who were within the expected age for grade (12–13 years) or those who were younger for the grade (<12 years) than among pupils who were older for the grade (>13 years).

In terms of numeracy and literacy achievement, interviews with male pupils revealed a marked academic improvement in Mathematics (numeracy) and English (literacy). For instance, in English, composition writing and an improved reading culture were the main areas of improvement. In numeracy, a better grasp of mathematical concepts, enhanced ability to interpret problem statements, and improved skills in algebra were the marked areas of improvement. A male pupil explains:

“Numeracy has helped me so much. I use to make mistakes that would cost me. You would find me doing my own thing. I would start well but fail in the last steps because I omit some steps.” (Dialogue, Male pupils, Korogocho, 10082018).

Impact of leadership training. At the endline just like at the midline more pupils endorsed items on the Social Competences sub-scale (1.58) at the lower end of the rating scale (not easily at all), while for the Self-Regulatory Efficacy sub-scale (2.84), more pupils endorsed items at the higher end of the rating scale (very easily). This suggests that pupils were more able to identify ways in which they could resist peer pressure than being able to be sensitive to other people’s feelings. In terms of the magnitude of change in scores among pupils, the greatest overall change in scores was seen on the Self-Assertive Efficacy sub-scale (speaking up for one’s rights); while the smallest change was on the Social Competences (ability to empathize) sub-scale, meaning that at endline pupils had improved in their ability to speak out for their rights. When we compared the two sites of Korogocho and Viwandani, the results revealed that endline pupils (both girls and boys) in Viwandani (where the leadership training intervention was delivered) had higher scores on the Social Competences (ability to empathize) and Adult-Youth Connections sub-scales (ability to have supportive relationships with adults), as well as on the overall leadership scale, compared to Korogocho. Overall, the leadership training seems to have had the strongest effect on the Self-Regulatory Efficacy sub-scale (DID 0.092), which was positive and significant at 5 percent level, when we compared baseline and endline results across sites. This change was greater for Viwandani. This may mean that pupils in Viwandani were more resilient to peer pressure (Abuya et al., Citation2019).

From the qualitative interviews, two key benefits came out. First, the leadership lessons spurred pupils to take up leadership positions in school and encouraged them to uphold ethics in their various positions. Moreover, pupils took deliberate steps to model good behavior to peers and siblings due to the recognition of the influential nature of a person in leadership. A female pupil said:

“I am fair. Because we were taught how to be good and be role models for them not to follow the bad behaviors that we have but to do the right thing … like in most schools, in secondary schools, there are pupils who lead others to strike.” (Dialogue, Female pupils, Viwandani, 06082018)

4.9. Lessons learned from the six years of implementation

Value of integrated approaches. Integrated approaches reduce inefficiencies and resource wastage associated with program fragmentation. Moreover, the program has to be systematic and structured when being implemented, with a sequenced step-by-step dosage. By this we mean the different components of the intervention had to be implemented with a specified number of activities throughout the implementation period. In addition, monitoring, evaluation, and learning were embedded to track both the uptake and the process of implementation. This may point to the notion that multi-sectoral and integrated approaches for adolescent girls’ programming are promising strategies for achieving high-level impact.

Inclusion of boys. Although the program had initially targeted girls, we learned from both local and global discourse that to enhance gender equity, it is best to target both boys and girls for a comprehensive girls’ education approach. Involving boys in the programs works to forestall the disadvantage that will accrue to boys thereby enabling both genders to have better education outcomes.

Use of mixed method approach in evaluations. In this program, the evaluation used mixed research methods, both quantitative and qualitative, to allow for a comprehensive picture of the effects, especially for soft skills and competencies. It is through the qualitative study that we learned how beneficiaries were using their newly acquired skills, especially in life skills and leadership. For instance, due to improved self-confidence, students can participate better in class because they are not shy to answer questions and ask for clarifications. Also, some key effects attributed to leadership activities such as taking up leadership positions were captured qualitatively, and we were able to see the changes in the score of attributes, like self-assertive efficacy. Using both quantitative and qualitative skills enabled us to look at the effects and to explain “the how” of the phenomena (Jimenez et al., Citation2018).

Structured mode of delivery. The mode of delivery of the intervention, which was structured and systematic was internalized and hailed by project beneficiaries as a key factor contributing to the success of the project as well as observed significant effects. For instance, pupils found mentors more approachable in sharing academic and personal issues affecting them compared to sharing these with their teachers. The fact that project recipients could speak to the success of the program signified that they were involved in the program and believed that their experience with programs is beneficial to the overall program evaluation. This lesson reinforces the fact that beneficiary perspectives should be sought at the onset, during, and at the end of the program (Twersky et al., Citation2013).

Enhanced communication within and across the program. One of the most important lessons of this program was the enhanced communication between parents and their children. In addition, the emergence of community champions who advocated for the program within respective households and communities suggested to us that the intervention was on the right track and had taken root. These champions included girls who were alumni of the program, parents, and community leaders, particularly the chief of Korogocho. Moreover, communication was nurtured in a free-flowing and open way among partners, stakeholders, and intervention leaders to stop problems from becoming insurmountable. Challenges were identified early in the program and dealt with before they became hindrances to program implementation.

Sustainability of the program through partnership with the community. Support for, and sustainability of the program increased over the years, as the community became more appreciative of the value of education. The program was entrenched into the community, the community fully owned it. Sustainability was enabled because of the engagement with well-known community-based organizations (CBOs), resulting in the project being fully entrenched within the two urban informal settlements. We achieved this level of ownership within the community because of the continued training and capacity building for all stakeholders who were involved in implementation. The CBOs enabled through their work and connection within the community to internalize study objectives and delineate roles and responsibilities among various stakeholders to ensure project success. For instance, annual refresher courses have been critical to maintaining project integrity among the mentors and counselors—considered the project’s “street-level bureaucrats”. Capacity building extended to training the CBOs on monitoring and evaluation techniques which were vital to assessing the progress and achievements of the project.

4.10. Discussion and conclusions

This paper aimed to establish the key endline findings and lessons learned from this community-based intervention targeting girls and boys in urban Nairobi. The findings showed positive impacts on aspirations, albeit only for girls, self-confidence, for those adolescents in Viwandani, and enhance parental monitoring beyond what was observed at baseline, observed mainly on girls. We observe, that some of these findings among girls showed the need for girls to be motivated to continue to aspire for higher education and the need for parents’ continued support and monitoring for this to be achieved. Therefore, this study advanced the notion that with support girls can be able to exhibit both academic and social outcomes and bridge the gap between them and boys. These gains are not only shown from a quantitative standpoint but also qualitative narratives as well. One of the other significant findings was about the magnitude of change in leadership scores among pupils. It should be noted that the greatest change in leadership scores was witnessed on the Self-Assertive Efficacy sub-scale (speaking up for one’s rights); while the smallest change in magnitude was witnessed on the Social Competences (ability to empathize) sub-scale. This infers that at the endline both girls and boys had improved in speaking up for their rights. This is a prerequisite for autonomy and decision-making, necessary for their agency and eventually advancing gender equity.

Consequently, after six years the ALOT-Change program provides useful lessons that should be taken into consideration when working with adolescents. The provision of safe spaces, the availability of proper role models and mentors from within the community, and opportunities for individual participation and community engagement are all facilitative factors that promote the success of adolescent programs. Individual participation and community engagement are particularly important because programs that focus only on the transfer of information are less effective than those that incorporate the development of skills. Moreover, engaging men and boys both as recipients of the program and as champions of change can help to create awareness of the need to challenge existing gender norms and attitudes. Overall, the success of a program is hinged on its ability to provide supportive relationships and promote an enabling environment that can help adolescents participate in making the decisions that shape their future.

This program was particularly important in the Urban Informal settlements in Kenya, where research evidence shows that young people, especially adolescents in the slums perform lower and are less likely to complete school and transition to secondary school compared to their counterparts in non-slums (Admassu, Citation2010). Adolescents in urban informal settlements are also likely to engage in sexual activities at an early age (Dodoo et al., Citation2007; Kabiru et al., Citation2010; Zulu et al., Citation2002), majorly attributed to the high incidence of poverty which forces young women to engage in transactional sex in exchange for basic needs (Stoebenau et al., Citation2016). The results from the evaluation studies in 2015, and 2018 clearly illustrate the positive effect of mentorship in life skills and leadership training on adolescent outcomes and demonstrate the potential of formal structured opportunities outside the classroom. In conclusion, the findings help to inform decision-makers at the national and sub-national levels, particularly concerning questions around the scale-up and sustainability of a similar program.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to all the co-authors who contributed to the different sections of the report. The authors thank the Anonymous donor whose investment in the project has contributed to the much-needed evidence on the delivery of life skills; modeling of after-school support programs; parental involvement; and improving learning outcomes. We would also like to acknowledge our implementing partners, Miss Koch Kenya and U-Tena youth organization for their diligence in delivering the Advancing Learning Outcomes for Transformational Change (A LOT-Change) project since 2013. We are also grateful to the adolescent boys and girls, their parents and guardians, mentors, counselors, and community leaders who have continued to take part in the A LOT-Change intervention activities as well as taking their time to participate in the study. In addition, we would like to thank the Ministry of Education (MoE), the Nairobi County Education office, and schools in the study areas for their continued support since the inception of the project back in 2013. We would also like to thank the APHRC internal review committee and AMREF Ethics and Scientific Review Committee (ESRC) for their guidance and support in ensuring that the project was both scientifically and ethically sound.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Benta A. Abuya

Benta A. Abuya is a Research Scientist at the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) in Nairobi, Kenya. She received her dual title Ph.D. in Education Theory and Policy and Comparative and International Education, with a Doctoral Minor in Demography from Pennsylvania State University. Her research interests include comparative education, education policy issues of access, equity, and quality; the linkages between education and health outcomes for adolescents; and gender issues in education.

Nelson Muhia

Nelson Muhia is a Research Officer at the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC). Nelson holds a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Economics and Sociology from Egerton University (2009). He joined APHRC as a field staff in 2010 and also worked as a team leader before the current appointment. Nelson wants to contribute to policy relevant research that impacts on the livelihoods and health of the people in Kenya, and indeed in Africa. Nelson also enjoys writing on other aspects of life such as the economy and education.

Patricia Kitsao Wekulo

Patricia Kitsao Wekulo is a Research Scientist at the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) in Nairobi, Kenya. She holds a PhD in Psychology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, and Master’s (M.Ed. – Home Economics) and Bachelor’s Degrees (B.Ed. – Home Economics) from Kenyatta University, Kenya. As a child development researcher, Patricia is interested in the investigation of the relationship between antecedent context characteristics and child developmental outcomes. This mainly concerns the influence of factors such as the child’s immediate environment on cognition, motor development, language and psychosocial behavior.

Notes

1. The analysis described is that which was used to establish the impact of the intervention after 6 years of programming. The baseline and midterm analytical procedure can be found in the subsequent baseline and midterm reports between 2013–2018.

References

- Abuya, B. A., Kitsao-Wekulo, P., & Chege, M. (2017). Advancing Learning Outcomes and Leadership Skills among Children in Nairobi’s Informal Settlements through Community Participation. http://aphrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ALOT-Change-summary-findings_FINAL.pdf

- Abuya, B. A., Ngware, M. W., Hungi, N., Kitsao-Wekulo, P., Mutisya, M., Gichuhi, N., Ngagi, J. & Mambe, S. (2016). Advancing learning outcomes and leadership skills through community participation. Nairobi: APHRC.

- Abuya, B. A., Ngware, M., Hungi, N., Mutisya, M., Mahuro, G., Nyariro, M., Mambe, S. (2015a). Community participation and after-school support to improve learning outcomes and transition to secondary school among disadvantaged girls: A case of informal urban settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. APHRC. https://aphrc.org/publications/improving-learning-outcomes-and-transition-to-secondary-school-through-after-school-support-and-community-participation/

- Abuya, B. A., Ngware, M. W., Hungi, N., Mutisya, M., Mahuro, G., Nyariro, M., Mambe, S. (2015b). Community participation and after-school support to improve learning outcomes and transition to secondary school among disadvantaged girls: A case of informal urban settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. APHRC. https://aphrc.org/publications/improving-learning-outcomes-and-transition-to-secondary-school-through-after-school-support-and-community-participation/

- Abuya, B. A., Ngware, M., Hungi, N., Mutisya, M., Muhia, N., Kitsao-Wekulo, P., Gathoni, G. (2019). Advancing learning outcomes and leadership skills among children living in informal settlements of nairobi through community participation. APHRC.

- Abuya, B. A., Ngware, M., Hungi, N., Mutisya, M., Nyariro, M., Mahuro, G., & Oketch, M. (2014). Community participation and after-school support to improve learning outcomes and transition to secondary school among disadvantaged girls. APHRC.

- Admassu, K. (2010). Primary school completion and grade repetition among disadvantaged groups: Challenge to achieving UPE by 2015. African Population and Health Research Center. https://aphrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/ERP-III-policy-brief-5.pdf

- APHRC. (2002). Population and health dynamics in Nairobi’s informal settlements. APHRC.

- APHRC. (2014). Population and Health Dynamics in Nairobi’s Informal Settlements: Report of the nairobi cross-sectional slums survey (NCSS) 2012: African population and health research center nairobi.

- Banerjee, A. V., Cole, S., Duflo, E., & Linfen, L. (2007). Remedying education: Evidence from two randomized experiments in India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1235–17. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.1235

- Barakat, B., & Urdal, H. (2009). Breaking the waves? Does education mediate the relationship between youth bulges and political violence? The World Bank.

- Beloe, P., & Derakshan, N. (2020). Adaptive working memory training can reduce anxiety and depression vulnerability in adolescents. Developmental Science, 23(4), e12831. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12831

- Birmingham, J., Pechman, E. M., Russell, C. A. & Mielke, M. (2005). Shared Features of High-Performing After-School Programs: A Follow-Up to the TASC Evaluation. Arlington: AIR.

- Blum, R. W., Astone, N. M., Decker, M. R., & Mouli, V. C. (2014). A conceptual framework for early adolescence: A platform for research. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 26(3), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2013-0327

- Blum, R. W., Bastos, F. I., Kabiru, C. W., & Le, L. C. (2012). Adolescent health in the 21st century. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1567–1568. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60407-3

- Blum, R. W., Boyden, J., Erulkar, A., Kabiru, C., & Wilopo, S. (2019). Achieving gender equality requires placing adolescents at the center. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(6), 691–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.02.002

- Botvin, G., Griffin, K., Paul, E., & Macaulay, A. (2003). Preventing tobacco and alcohol use among elementary school students through life skills training. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 12(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1300/j029v12n04_01

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. sage.

- Breuer, E., Lee, L., De Silva, M., & Lund, C. (2016). Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 11(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0422-6

- Control, C. F. D., & Prevention. (2011). Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: A self-study guide. US Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Office of the Director, Office of Strategy and Innovation.

- Crabtree, B. F., & Miller, W. L. (1999). Doing qualitative research. sage publications.

- Deng, Z., & Gopinathan, S. (2016). PISA and high-performing education systems: Explaining Singapore’s education success. Comparative Education, 52(4), 449–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2016.1219535

- Dodoo, F. N. A., Zulu, E. M., & Ezeh, A. C. (2007). Urban-rural differences in the socioeconomic deprivation–Sexual behavior link in Kenya. Social Science & Medicine, 64(5), 1019–1031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.007

- Duflo, E., Dupas, P., & Kremer, M. (2011). Peer effects, teacher incentives, and the impact of tracking: Evidence from a randomized evaluation in Kenya. American Economic Review, 101(5), 1739–1774. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.5.1739

- Dulark, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3–4), 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9300-6

- Erulkar, A. S., & Muthengi, E. (2009). Evaluation of Berhane Hewan: A program to delay child marriage in rural Ethiopia. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35(1), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1363/3500609

- Funnell, S. C., & Rogers, P. J. (2011). Purposeful program theory: Effective use of theories of change and logic models (Vol. 31). John Wiley & Sons.

- Isiugo-Abanihe, U. C. (2003). Male role and responsibility in fertility and reproductive health in Nigeria (CEPAED).

- Jimenez, E., Waddington, H., Goel, N., Prost, A., Pullin, A., White, H., Lahiri, S., & Narain, A. (2018). Mixing and matching: Using qualitative methods to improve quantitative impact evaluations (IEs) and systematic reviews (SRs) of development outcomes. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 10(4), 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2018.1534875

- Kabiru, C. W., Beguy, D., Ndugwa, R. P., Zulu, E. M., & Jessor, R. (2012). “Making It”: understanding adolescent resilience in two informal settlements (Slums) in Nairobi, Kenya. Child & Youth Services, 33(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2012.665321

- Kabiru, C. W., Beguy, D., Undie, C. C., Zulu, E. M., & Ezeh, A. C. (2010). Transition into first sex among adolescents in slum and non-slum communities in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Youth Studies, 13(4), 453–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261003801754

- Kabiru, C. W., Mojola, S. A., Beguy, D., & Okigbo, C. (2013). Growing up at the “margins”: Concerns, aspirations, and expectations of young people living in Nairobi’s slums. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00797.x

- Mahmud, S. (2003). Female secondary school stipend program in Bangladesh: A critical assessment. Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies.

- MoE. (2012). Task force on the re-alignment of the education sector to the Constitution of Kenya, 2010. Republic of Kenya.

- Ngware, W. M., Abuya, B. A., Admasu, K., Mutisya, M., Musyoka, P., & Oketch, M.(2013). Quality and access to education in urban informal settlements in Kenya. Nairobi (APHRC). Republic of Kenya

- The Ontario Public Service. (2016). 21st century competencies: Foundation document for discussion. Phase 1: Towards Defining 21st Century Competencies for Ontario. Retrieved from Ontario.

- Prajapati, R., Sharma, B., & Sharma, D. (2017). Significance of life skills education. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 10(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v10i1.9875

- Priestley, M., Wilson, A., Priestley, A., & Serpa, R. (2017). Mapping the impact of educational interventions. Final Report. Education Achievement Service.

- Stoebenau, K., Heise, L., Wamoyi, J., & Bobrova, N. (2016). Revisiting the understanding of “transactional sex” in sub-Saharan Africa: A review and synthesis of the literature. Social Science & Medicine, 168, 186–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.023

- Twersky, F., Buchanan, P., & Threlfall, V. (2013). Listening to those who matter most, the beneficiaries. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 11(2), 40–45. https://www.ncfp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Listening-to-Those-Who-Matter-Most-SSIR-2013.pdf

- UNESCO. (2013). Education Transfroms Lives. http://www.unesco.se/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Education-transforms-lives.pdf

- Yadav, P., & Iqbal, N. (2009). Impact of life skill training on self-esteem, adjustment, and Empathy among Adolescents. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 35(SI), 61–70. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Naved-Iqbal/publication/312119543_Impact_of_Life_Skill_Training_on_Self-esteem_Adjustment_and_Empathy_among_Adolescents_Pooja_Yadav_and_Naved_Iqbal/links/586fdad808ae8fce491ded8f/Impact-of-Life-Skill-Training-on-Self-esteem-Adjustment-and-Empathy-among-Adolescents-Pooja-Yadav-and-Naved-Iqbal.pdf

- Zulu, E. M., Dodoo, F. N. A., & Chika-Ezeh, A. (2002). Sexual risk-taking in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya, 1993-98. Population Studies, 56(3), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720215933