Abstract

This research aimed to explore the possibility of using Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach for the development of students’ Second Language (L2) skills and content in the subject of Chemistry. To achieve this purpose, action research method was used to implement CLIL approach at grade 7 consisting of 30 students. The research was divided into two major cycles, each cycle containing actions to improve the situation and providing a base for the next cycle. The researchers planned and implemented lessons using the CLIL approach. Interviews, observations, and document analysis were used to generate data. The research revealed that although CLIL has the potential to enhance the content knowledge and language competency of students, certain factors such as the academic background of students, the capacity of teachers and the system-related expectations from teachers influence the implementation of the approach in this region. The paper explores the possibility and challenges of a language teaching approach (CLIL) which has received increasing attention in other contexts but has remained unattended and unexplored in the context of Pakistan.

1. Introduction

As depicted analogically by Dallinger et al. (Citation2016, p. 23), Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is “killing two birds with one stone”. The focus of the approach is on enhancing content knowledge by using English as a medium of classroom instruction (Coyle, Citation2007). In this way “two birds”, namely, content and language are clutched in one go. CLIL has been around and researched in Europe for decades where the approach has been found to be having positive impact on students’ language proficiency as well as their motivation towards language acquisition (see, for example, González, Citation2011; Lorenzo et al., Citation2010). In Asia, the contemporary trends of globalization and competitive market have led to an increasing interest in English and consequently in CLIL owing to its potential to enhance language (Kim & Lee, Citation2020). Studies conducted in this part of the world on CLIL show a positive impact of the approach upon student achievement especially in relation to language acquisition; however, they also highlight teacher orientation and hierarchical system as the most dominant influencing factors in the implementation of the approach (Godfrey, Citation2016; Kim & Lee, Citation2020; Tsuchiya & Murillo, Citation2019; Yamano, Citation2019).

Although efforts are underway in many parts of the world including some Asian countries to implement CLIL approach owing to its novelty and possibility of learning content as well as language in integrated way, the approach has received remarkably little or no attention in some developing countries of Asia such as Pakistan. Both experience and studies (Sarwat et al., Citation2021) suggest that most of the educators are unaware of this approach to teaching and learning. Consequently, implementing CLIL approach at classroom level in Pakistan has not been observed or reported so far. What we know, however, is that the subject teachers barely focus on the language skills of students (Mamuna & Sumaira, Citation2018). The expectation from students to rote learn and memorize contents to reproduce them in the examination (Pell et al., Citation2010) could also be a factor influencing the focus on the language skills. Evidence also suggest that students lack any exposure to learn English language in an authentic and meaningful settings (Manan, Citation2019; Nawab, Citation2012). Their low language competency not only hinders their communication skills but also results in poor comprehension of subject matter ultimately leading to low academic achievements.

With the assumption that CLIL approach has the potential to address this issue, an action research was conducted in a middle school in rural Sindh to explore the possibilities and challenges of using CLIL to enhance content and language competency of students. The authors were more interested in understanding the factors influencing the implementation of CLIL approach in the context of Pakistan owing to their theoretical exposure to the approach as well as its relevance to their current roles. Researching the concept in this context provides us with many insights which we expect to use in our own class to provide students with enhanced content and language development opportunities. The insights this study brings forth can also be beneficial for Pakistan and other contexts having similar education systems. It is expected that on the basis of the findings of this research, teachers, teacher educators, and educational reformers can revisit their practices. Educational reformers and policymakers may consider the importance and possibility of CLIL approach and revisit the pre-service and in-service teacher education programs to enhance the capacity of teachers in relation to using the approach at classroom level. The assessment practices may value and reward language skills to encourage the use of CLIL approach. If the approach is implemented successfully, students would be the ultimate beneficiaries.

2. Conceptual framework

Initially introduced in Europe in late 1990s, Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is a dual approach to teaching where the content of any subject is learned using second language and the second language is learned during the process of learning the content of a subject (Coyle, Citation2007). In other words, during the process of teaching and learning, the focus is on both content as well as language. In this way, the learning of language and content takes place simultaneously. Coyle (Citation2007) has forwarded a theoretical model for effective CLIL implementation through a “4Cs model” which is considered to be a holistic approach, where Content, Communication, Cognition, and Culture are integrated. Content denotes progression in knowledge, skills, and understanding; Communication is the development of appropriate communication skills; Cognition is the engagement in higher-order cognitive processing; and Culture is the acquisition of deepening intercultural awareness. As Coyle (Citation2007) explains:

The framework goes beyond considering subject matter and language as two separate elements but rather positions content in the ‘knowledge for learning’ domain (integrating content and cognition) and language, a culture-bound phenomenon, as a medium for learning (integrating communication and intercultural understanding). (pp. 549-550)

Accordingly, the framework suggests that subject matter is about not only content but also the process of constructing knowledge which involves thinking. The content and cognition, on the other hand, are mediated by language. How language is used depends on the context, culture, and nature of interactions. In this sense, the 4Cs are interdependent although the culture component pervades the overall process. The cultural aspect is about students’ learning behaviors, styles, and other contextual realities such as expectations from students in the examination. It is important for a teacher to identify and capitalize on the learning behaviors and styles of students while planning lessons. Otherwise, as concluded, by Godfrey (Citation2016) on the basis of his prolonged experience of using CLIL and researching the concept in an Asian context, the lack of awareness about culture hinder the other Cs of CLIL.

Although some academics question this approach owing to the challenges it has brought for teachers, this approach to teaching has gained a growing attention from academics and practitioners owing to its possibility of impacting student achievements in a positive way. Literature shows a close association between language development and CLIL approach (Xanthou, Citation2011). Using this approach, teacher and learners interact in a meaningful situation and try to make sense of the activities happening in the classroom (Xanthou, Citation2011). Owing to such potential, CLIL has also been implemented in Asian context. Studies in Asia especially from Japan report a positive impact of CLIL approach on student achievement (Godfrey, Citation2016; Yamano, Citation2019). Using various cognitive skills, learning authentic content, enhanced use of English for communication and understanding of various cultures were the positive outcome of CLIL approach reported from Japan (Yamano, 2013).

Although studies in Asia report some success stories with regard to the implementation of CLIL (Godfrey, Citation2016; Yamano, 2013), there also exist some knowledge on the challenges in relation to the implementation of CLIL approach. Bozdoğan and Karlıdağ (Citation2013), for example, identified differing proficiency level of students, overcrowded classroom, lack of language teaching aids, focus on grammar and unmotivated teachers as factors hindering the CLIL approach in Turkey. Coupled with reduced motivation of teachers, teacher agency including his/her beliefs and orientation about language teaching has also been identified as a major challenge. As found by Kim and Lee (Citation2020), in Korea, an Asian context, teachers’ beliefs regarding the prevalent hierarchical approach where decisions mostly come from the top made them resist the approach. They lacked autonomy to plan their lessons using CLIL approach which requires a considerable shift with regard to the focus of teaching. To enhance teacher agency, in developed context, such as Spain, teachers are offered with well-developed CLIL programmes unlike Asian context where teachers either lack such exposure or in some cases, such as in Japan (Tsuchiya & Murillo, Citation2019), Hong Kong (Corrigan, Citation2013) and UAE (Riddlebarger, Citation2013) teachers are provided with limited opportunities to develop their skills in relation to CLIL approach.

Although the importance of English language has consistently been highlighted for the learners in Pakistan, the current classroom teaching and learning practices are quite unlikely to develop English language skills (Haidar & Fang, Citation2019; Nawab, Citation2012). Since CLIL is found having the capacity to enhance both language and content (Coyle, Citation2007), it seems an ideal approach for this region. However, the approach has been originated and implemented in developed contexts. We lack any empirical evidence to show how it unfolds in Pakistan. Given this background, just exploring how CLIL unfolds in Pakistan might have led to the simple conclusion that the approach is not in practice in this context. The researchers were interested in understanding the possibilities and challenges of using CLIL approach in this region through using an action research which allows interventions and actions to improve the situation. The question that guided this research was: What are the possibilities and challenges of implementing CLIL approach in a private sector school in Northern Sindh, Pakistan. The outcomes reported in this paper bring forth significant insights in relation to the use of CLIL approach in a relatively backward context of Pakistan which has implications for similar contexts beyond Pakistan.

3. Methodology

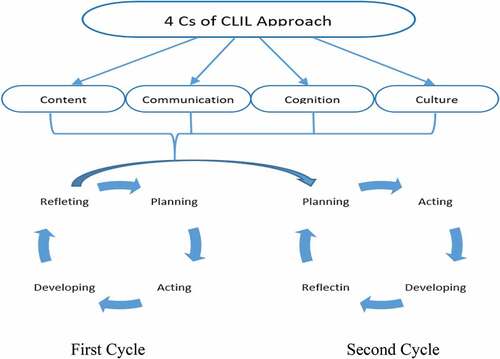

Since the purpose of this research was to understand the possibilities and challenges of implementing CLIL with the ultimate aim of improving the situation, action research approach was used which allows the researcher to adopt different methods, techniques, and strategies according to the needs of situation (Burns, Citation2009). The research used Mertler (Citation2018) model of action research as it allows and guides transformational innovation by employing four main stages, namely, planning, acting, developing and reflecting. The 4Cs theoretical model of CLIL guided the actions in each cycle as the plans incorporated content, communication, cognition, and culture. Accordingly, each lesson in each cycle incorporated the 4Cs by focusing on the lesson content, considering cognitive aspects to engage the students, outlining the actions to involve students in communication and being mindful of how the content and activities might be connected to the students’ world. Figure represents the overall framework of the research. The intervention steps including the cycles and actions are explained later. First, the research setting and participants are detailed to guide the readers towards the intervention procedures.

4. Research setting and participants

This research was conducted in one of the higher secondary schools of Sukkur, Sindh. The main reason to select the particular school was that it was managed by the university where the researchers are currently working. The university and the school encourage research in order to improve the educational practices. Consequently, it was easier for the researchers to intervene in the particular school for research purpose. Other schools in the region might not have allowed the researchers to conduct action research as it requires intervention and takes sufficient time. The participants of the research were Chemistry teacher and 7th grade students. Chemistry was preferred owing to the background of the first author in this subject. The research was focused on grade 7 with the assumption that compared with lower stage, students at this level would be having considerable language skills to implement the CLIL approach smoothly. At higher level, students are prepared focusing the external exam questions and therefore, it might not have been appropriate to implement CLIL at higher level. There were total 30 students in the class, of which 14 were girls and 16 were boys. Their ages ranged from 11 to 12 years old. The mother tongue of the majority of the students was Sindhi, the language spoken in Sindh province of Pakistan. Since it was a private school, the medium of instructions was English, a common feature of private sector schools in the region. Although all the students of the class participated in the study, to be more specific and manageable, data were collected from slow learners and quick learners or those who were less responsive and more responsive in the class.

Before, during and after the research, all the key principles on which research ethics are evaluated at university where the authors currently locate were strictly followed. These principles include informed and voluntary consent, privacy, confidentiality and anonymity, and reciprocity to ensure that the study does not harm anyone. Most importantly, the researchers tried their best not to disturb the classes and routines or be a cause of inconvenience to the students and teachers.

The intervention lasted a whole month where each of the two cycles was completed in two weeks, each cycle containing three lessons. The cycles and actions are presented in detail in the following section starting with reconnaissance.

5. Situational analysis

Before implementing CLIL in the Chemistry classroom, the researchers did a situational analysis to be familiar with the present situation and background of the students and teachers. Taking informed consent, the first author observed a couple of lessons of Chemistry teacher at grade 7. The observation aimed at identifying her approaches to teaching with a focus on content and language integration. The researcher also interviewed the teacher to understand her assumptions, beliefs and perceptions on the approaches she was using. In addition, some of the students were also talked to regarding their experience of teaching and learning processes in the Chemistry subject.

The observations were recorded using a checklist while the interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed. The data were then organized and coded to understand the existing situation in relation to the classroom teaching and learning practices. Data emerging from classroom observation revealed that the overall focus of the Chemistry teacher was on content of the subject. The teacher very occasionally uses English. She was found using two languages namely Urdu and Sindhi. Initially, she was trying to explain the content to the students in Urdu. When students were not able to follow her, she was switching to Sindhi. While justifying her approach, the teacher said that her overall focus is on developing content knowledge of the students. In order to make them understand the content, they were sometimes using the mother tongue of the students. The teacher further revealed that students were too poor at English; therefore, it was hard for them to comprehend the content when taught in English. When the teacher was asked about the possibility of CLIL to enhance students’ language proficiency, she showed her lack of awareness regarding this approach.

While talking to the students it was found that although good at content, they were unable to express their understanding in English. When they were asked how and when they develop their English language skills, they referred to English subject showing their perceptions that language can be developed only in the relevant subject. The analysis of their notebooks also suggested that whenever they were given any feedback, it was on their conceptual understanding. The language errors had been ignored by the teacher in the subject of Chemistry.

As happens in an action research, data collection and analysis was an ongoing process starting from the situational analysis. At each stage and cycle, the researchers used observations, interviews and document analysis to generate data. The observations were recorded using a checklist. The interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed. Field notes were taken noting down any significant data emerging from observation and document analysis. The field notes were then developed into reflections. The data were then organized and coded systematically. As a result of analyzing the emerging data at the situational analysis stage, two main conclusions were drawn which guided the first cycle. Firstly, the focus of the Chemistry teacher was mainly on content, perhaps because of the lack of awareness regarding the CLIL approach. Secondly, students’ language competency requires improvement as they were unable to demonstrate their understanding of the content. Thus, there was potential for the CLIL approach to improve the situation if implemented in this setting.

6. First cycle

Building on the lessons learnt during the reconnaissance and considering the 4Cs, the researchers planned and implemented several activities and strategies to introduce the CLIL approach. The very first step in this regard was orienting the teacher on the importance and possibility of CLIL. This initiative was taken to allow the teacher to support the research process in an informed way. Next, some classroom norms involving the students and the teacher were set. One of the major norms for students to be observed was using English as a classroom language, a first step towards CLIL. Once the scene was set, the first author planned and taught lessons using the CLIL approach guided by the 4Cs framework. Accordingly, each lesson focused on a particular content of Chemistry. Communication was facilitated by providing students with the opportunities to express themselves. The cognition aspect was considered focusing on low-order thinking skills initially and then gradually moving on to the high-order thinking skills. The cultural aspect was incorporated by allowing students to work in groups and pair in order to provide them with the opportunity of interacting with and thus, understanding one another.

The first lesson in this regard was the concepts of acids, base, and salt. These contents were selected in consultation with the teacher. The objectives for the lessons and activities were designed in such a way where first the researcher introduced and demonstrated the concepts using English and then engaged students in activities considering the 4Cs. In the first lesson, for example, the first researcher taught the concept of acid, focusing its low-level cognition such as defining acid and listing some examples. Group and pair works were introduced to expose students to the 4Cs, namely, content, communication, cognition, and culture. Following this procedure, the researcher taught five lessons, two lessons a week and each lesson lasting 50 minutes. During these lessons, both content and language-related aspects were presented using different resources such as pictures and models for longer retention. In order to make the learning more meaningful and authentic, different daily life examples were given to students to enable them understand the content as well as be familiar with various language structures. Students were advised and expected to use English while asking questions, responding to the questions and interacting with their peers during pair and group work.

Based on the collection and analysis of the data, the following insights were gained during the first cycle. Firstly, the students were very hesitant especially at the beginning to use English. Whenever they were provided with an opportunity to express themselves in English, they were struggling with language and feeling shy. As the researcher observed, when they were given a task which involved speaking, there used to prevail silence in the class as they were reluctant to speak. Sharing his view in relation to this situation, a student stated during an interview that “I don’t know what to say and where to start in English”. However, as the researcher consistently encouraged them for their efforts, they gradually developed confidence and started to try using English, although their language competency was fairly low. It was quite challenging for them to express their ideas in English. Often it happened that they knew the concept but could not communicate their understanding. The major issue they faced was finding appropriate vocabulary. When the researcher allowed them to explain the concept in their native tongue, majority of them were doing that comfortably. This made the researcher realize that shifting to English abruptly is not a wise strategy. Moreover, the need of further strategies and activities was felt to enhance their vocabulary.

In addition, it was also apprehended that, as both the researcher and students focused on the language, the content was getting reduced attention. At the end of one session which focused mainly on communication considering their low level in this area, it was found during the assessment stage that majority of the students were unable to explain the content covered on that day. Consequently, there was a risk that the students may not develop understanding of the science concepts if the researchers carry on focusing on the language and communication. Lastly, as there was two days gap between each lesson, students were observed reverting to their previous habits and routines owing to the gap. It made the researchers realize that the lessons should be carried out continuously without any gap in the middle.

7. Second cycle

On the basis of the lessons learnt during the first cycle, the researcher planned for and implemented activities and strategies in the second cycle. The first and major strategy was switching to Urdu while explaining complex terms and concepts. When the researcher realized that students were unable to understand a concept when presented in only English, she explained it in Urdu. Informed by the research findings reported from Sri Lanka (Karabassova, Citation2018), relatively a similar context to Pakistan, students were also allowed to switch to other language when it was not possible to express themselves in English. A new terminology was coined, namely, “UrduishEnglish” suggesting that they can use Sindhi or Urdu as a replacement of only those words for which they do not have English equivalent. This strategy was used to allow them express themselves without fully reverting to Sindhi or Urdu.

As one of the major challenge students faced in expressing their ideas was their limited vocabulary, more time was spent on their vocabulary development using a variety of ways such as showing pictures, using flash cards and developing word walls. Even some vocabularies were taught in advance to enable them to read the text in an easier way. In addition, to overcome their shyness, coupled with continued encouragement, more pair and group work were planned to enable them practice language with their peers in a more relaxed environment. Lastly, based on the experience of the previous cycle and informed by the research that shows better outcomes for students with more CLIL sessions per week (Vithanapathirana & Nettikumara, Citation2020), the researcher taught lessons on daily basis to make students speedily adjust to the new approach.

As the second cycle continued the researcher regularly collected and analyzed data. At this stage, data collected and analyzed over the whole period of the research was organized and read again and again looking for the most significant insights to be presented and discussed further. For this purpose, the whole data were organized and coded. Then, patterns were drawn putting the relevant codes together. The patterns were developed or elevated into major themes that were also guided by the research purpose and questions. Consequently, there emerged the following two major themes.

Possibilities and potentials of CLIL

Challenges of implementing CLIL

8. Possibilities and potentials of the CLIL approach

This research demonstrated the possibility and several potential benefits of CLIL approach. Firstly, it was found that CLIL has the potential to enhance language competency of students. The observations by the researchers as well as the comments of both teacher and students suggested some improvement in both content and language of the learners. Although, the students were struggling at the beginning, as observed at the concluding stage of the research, they showed an encouraging progress. During an interview, a student said that “you see now we are trying to communicate in English. Learning is also fun as we are engaged in interesting activities”. Compared with the beginning stage, they were more confident and trying to express themselves. Although they were still facing difficulty to fully understand the content when presented in English, compared with the beginning stage, English language was more familiar to them. When the researcher was giving instructions in English at the beginning stage, students were usually found to be confused. At the end of the research, although, students were still facing difficulty in expressing themselves, majority of students were comfortable with instructions and easily following what they were instructed to perform. It suggests that sustained practice of CLIL approach has the potential to enhance the language competency of students.

Secondly, it was also observed that being involved in this research, the teacher developed a basic understanding of the approach and reflected on her role as a teacher. She stated that “previously I was ignoring the language errors of students. Now I feel that the language related components should also be a focus of a teacher”. She made this comment on the basis of her observation of students who, when given opportunity, were showing encouraging progress in the language. She further revealed that previously she did not know about this approach. Developing language skill was the responsibility of English teacher as per her understanding. Thus, the data suggest that if teachers are given an orientation and opportunity to implement CLIL, they observe its potential benefits and develop appreciation for the approach. Once they develop such attitude, they are more likely to implement the approach.

Thirdly, CLIL was well received by the students as they showed a considerable appreciation for this approach. “We had been asking our teachers to provide us with language practice opportunities. Now when we get this opportunity, we are so happy” a student shared her views. Students’ response to the intervention suggested that they are interested in enhancing their language competencies. However, they are barely provided with language development activities. Some students were of the opinion that previously, the teacher was giving them lecture most of the time. “It is quite boring just to listen to the teachers”, a student shared his observation. Now the students were happy as they were engaged in a variety of activities such as group work. As a result, learning was fun for them. This finding also suggests that implementing CLIL approach also leads to a shift from teacher-centered to student-centered pedagogies.

Fourthly, this research also found that CLIL approach contributes to developing good relationship among students as they frequently interact while working in groups and pairs. As observed during the reconnaissance, the teaching practices were mostly teacher-centered providing limited opportunities to students for interaction. Considering the culture component of 4Cs, CLIL approach introduced interactive teaching strategies such as pair work, group work, presentations, and other hands-on activities where students got plentiful occasions to interact with one another. Although, students were reluctant to work in group or pair at the beginning, they were found quite interactive and active while working in groups as the action research was coming to an end. Thus, considering the cultural aspect of 4Cs, CLIL approach has the potential to allow students understand and appreciate diversity by working together in various activities.

9. Challenges of implementing CLIL approach

Although CLIL has several potential benefits compared with the traditional practices as revealed in this research, implementing the approach in this region seems quite challenging. The major challenge in this regard was found to be the low competency of students in English. Students’ reaction and response to the intervention showed that they were facing difficulty in understanding the contents when presented in English. Even if they understood the content, they were unable to express their learning using English. As a student responded to a question of the researcher during the first cycle, “we did not get anything. What we can tell others if we do not know ourselves. It is hard for us to communicate in English even if we know something”. Similarly, the observations also suggested that when they were expected to communicate with their colleagues in English, they were struggling with the language.

The students revealed that they were hardly given practice of speaking in English. “We use Sindhi in our class. We want to learn and use English but our teachers do not give us such practice”, a student stated. This representative quote supports the observation during the reconnaissance that students are provided with limited opportunities of practicing English language in their classroom. Most of the time, they use Sindhi and consequently lacked competency in English. The teacher was of the opinion that in their tests and examinations, their content knowledge is checked. “We ignore language errors in their test”, the teacher revealed. Since assessment practices drive the teaching practices, the science teacher did not give any importance and, consequently, time to practice language.

In this situation, when the researchers tried to improve their language skills by using English as a classroom language, there was a risk of ignoring or giving reduced space to the content. While reflecting on one lesson in the first cycle, the researcher found that although language-related objective of the lesson was achieved to a greater extent, students demonstrated little understanding of the taught content as assessed at the end of the lesson. This made the researcher shift her focus as the second cycle unfolded.

Another challenge which may keep on hindering the implementation of CLIL is the capacity of the teacher in English. As observed during the reconnaissance stage, the teacher was struggling while trying to explain the concept to the students in English. CLIL demands that a teacher using this approach should have a sound language competency so that he/she can use the second language to teach content and help students in developing their language skills. It was unsurprising to note from the teacher that she lacked any awareness with regard to CLIL approach. In response to a question posed by the researcher whether she had got any orientation on CLIL, the teacher revealed that “although I have attended several workshops, I do not remember we had ever been provided with ideas on this approach”. The quote supports the common experience that so far no orientation has been conducted for teachers on CLIL in Pakistan. A teacher cannot be expected to implement CLIL approach without any orientation and training.

10. Discussion

Certain significant conclusions can be drawn on the basis of the results presented above Firstly and importantly, the level of students proves to be a highly dominant factor influencing the process of implementing CLIL approach in this region similar to the experience of students reported from other Asian context such as Indonesia (Merino & Lasagabaster, Citation2018). When students lack basic language competency, it is very challenging to use CLIL approach as found in this research. Since the students face difficulty in understanding and using English, it adversely affects their learning of the content (Panezai et al., Citation2017). Consequently, if the focus is on language, there is a risk of compromising content which both the teacher and students cannot afford owing to the system expectations. A teacher teaching subjects other than English is accountable for the content of the respective subject, not the language. A science teacher can be asked about the achievement of students in science subject only. The science teachers is not expected to provide language-related support to students or to value and reward language competency of students in the assessment. Teachers could have shifted to CLIL approach provided they were independent to modify their teaching and assessment practices. However, similar to other Asian context such as Korea (Kim & Lee), a hierarchical system prevails where teachers lack autonomy to modify their practices. Changes need to be introduced at system level to implement CLIL and to revisit the assessment practices. In addition, teachers teaching any subject should be made responsible for integrating language skills in their teaching.

However, a critical aspect requiring attention is that if students’ level is low with regard to language competency, it is owing to the reduced exposure to language development activities. If language is a barrier, it is because language has received less attention in the classroom. Students demonstrate higher motivation for as well as ability to learning English, however, other factors especially teachers and learning situations negatively affect students’ attitude (Aziz et al., Citation2017; Getie & Popescu, Citation2020). As emerged in this research, when the students were provided with the opportunity, they showed promising progress. When the researchers consistently provided them with language practice activities and encouraged them for their efforts as suggested by Godrey (Citation2016), they not only understood the instructions gradually but also tried to express themselves in English. It suggests that, if implemented, the approach can be helpful for those students who, otherwise, have been denied of language enhancement opportunities.

The most significant challenge in shifting to CLIL approach, therefore, would be the capacity of teachers. It is because implementing CLIL involves subject teachers using English to teach their subject (Sanjurjo et al., Citation2018). However, teachers in this context lack awareness about the approach, possibility and importance of CLIL similarly to the teachers in other Asian context such as Kazakhstan (Manafe, Citation2018). What enables and motivates teachers to implement CLIL, as conveyed from Sri Lanka, is providing them an awareness of the theoretical principles of the approach (Karabassova, Citation2018). If the teachers are to be prepared for CLIL approach, their in-service training should include this component. In addition, the existing teachers should also be oriented on CLIL approach and provided with the opportunities of improving their language capacity. In this sense, the approaches to developing teachers for CLIL will be quite different with the fact that they need to “include both language competency and content areas, plus the unique strategies and understandings that educators must explore as they plan for the CLIL classroom” (Pérez Cañado, Citation2018, p. 200). Similar needs to develop teachers with regard to the implementation of CLIL has been highlighted from other Asian countries such as Japan (Tsuchiya & Murillo, Citation2019), Hong Kong (Corrigan, Citation2013) and UAE (Riddlebarger, Citation2013).

11. Conclusion

Although CLIL can rightly be considered as a dire need of the day owing to its potential to improve both content and language, without introducing change in the system and preparing teachers purposefully, it is very unlikely to successfully implement the approach. This conclusion has implications for policymakers, education reformers and teacher education institutes in Pakistan. CLIL can be implemented only if the teachers possess adequate language skills. Therefore, at policy level, competency in English should be a requirement for teacher recruitment. In addition, both pre-service and in-service teacher education providers should include CLIL in their programs to enhance the capacity of teachers and to enable them implement CLIL approach at classroom level. The assessment practices should also be revisited to value and reward language skills in any subject. Without introducing these changes, it is very unlikely to use CLIL approach in this region.

This research was conducted in a private sector school where teaching practices and student achievements, as reported earlier (UNESCO, Citation2014), are much better compared to the public sector schools. Therefore, the findings of the current research may not be generalized to public sector schools. Since public sector is the largest education provider in Pakistan, it is recommend to implement the same research in public sector schools to understand the factors influencing the implementation of CLIL approach. Greater number of students will be benefited if the teaching and learning practices are improved in public sector schools.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aziz, F., Quraishi, U., & Huang, Y. X. H. (2017). An insight into secondary school students’ beliefs regarding learning English language. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1278835

- Bozdoğan, D., & Karlıdağ, B. (2013). A case of CLIL practice in the Turkish context: Lending an ear to students. Asian EFL Journal, 15(4), 89–110. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12491/4836

- Burns, A. (2009). Action research in second language teacher education. The Cambridge Guide to Second Language Teacher Education, 289–297. https://www.academia.edu/36024949/Action_Research_in_Second_Language_Teacher_Education

- Corrigan, P. C. (2013). An in-service programme in Hong Kong for integrating language and content at the post-secondary level. The Asian EFL Journal Special Edition, 431. http://asian-efl-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/Vol-15-Issue-4-December-2013-Special-Edition-45155200a.pdf#page=432

- Coyle, D. (2007). Content and language integrated learning: Towards a connected research agenda for CLIL pedagogies. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.2167/beb459.0

- Dallinger, S., Jonkmann, K., Hollm, J., & Fiege, C. (2016). The effect of content and language integrated learning on students’ English and history competences–Killing two birds with one stone? Learning and Instruction, 41, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.09.003

- Getie, A. S., & Popescu, M. (2020). Factors affecting the attitudes of students towards learning English as a foreign language. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1738184

- Godfrey, C. L. (2016). Cultural awareness: CLIL in a Japanese medical university context. In K. Papaja & A. Swiatek (Eds.), Modernizing educational practice: perspectives in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) (pp. 76–97). Scholars Publishers.

- González, A. V. (2011). Implementing CLIL in the primary classroom: Results and future challenges. In C. E. Urmeneta, N. Evnitskaya, E. Moore, & A. Patino (Eds.), AICLECLIL-EMILE educacio plurilingue: experiencias, research & politiques (pp. 151–158). Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona.

- Haidar, S., & Fang, F. (2019). English language in education and globalization: A comparative analysis of the role of English in Pakistan and China. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 39(2), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2019.1569892

- Karabassova, L. (2018). Teachers’ conceptualization of content and language integrated learning (CLIL): Evidence from a trilingual context. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1550048

- Kim, H. K., & Lee, S. (2020). Multiple roles of language teachers in supporting CLIL. English Teaching & Learning, 44(2), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-020-00050-6

- Lorenzo, F., Casal, S., & Moore, P. (2010). The effects of content and language integrated learning in European education: key findings from the andalusian bilingual sections evaluation project. Applied Linguistics, 31(3), 418–442. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amp041

- Mamuna, G., & Sumaira, Q. (2018). Differentiation in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) at secondary level education in Pakistan: Perceptions, practices and challenges. International Journal of Management and Applied Science, 4(12), 21–27. http://iraj.doionline.org/dx/IJMAS-IRAJ-doiONLINE-14537

- Manafe, N. R. (2018). Making progress in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) lessons: An Indonesian Tertiary Context, Paper presented at the SHS web of conferences. Bali, Indonesia.

- Manan, S. A. (2019). Myth of English teaching and learning: A study of practices in the low-cost schools in Pakistan. Asian Englishes, 21(2), 172–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2018.1503041

- Merino, J. A., & Lasagabaster, D. (2018). The effect of content and language integrated learning programmes’ intensity on English proficiency: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 28(1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12177

- Mertler, C. A. (2018). Action research communities: Professional learning, empowerment, and improvement through collaborative action research. Routledge.

- Nawab, A. (2012). Is it the way to teach language the way we teach language? English language teaching in rural Pakistan. Academic Research International, 2(2), 696. https://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_ied_pdcc/9/

- Panezai, S. G., Channa, L. A., & Law, H. F. E. (2017). Pakistani government primary school teachers and the English textbooks of Grades 1–5: A mixed methods teachers’ led evaluation. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1269712

- Pell, A. W., Iqbal, H. M., & Sohail, S. (2010). Introducing science experiments to rote-learning classes in Pakistani middle schools. Evaluation & Research in Education, 23(3), 191–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500790.2010.489151

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2018). Innovations and challenges in CLIL teacher training. Theory Into Practice, 57(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2018.1492238

- Riddlebarger, J. (2013). Doing CLIL in Abu Dhabi. Asian EFL Journal, 15(4), 413–421. https://www.asian-efl-journal.com/volume-15-issue-4/doing-clil-in-abu-dhabi/index.htm

- Sanjurjo, J. F., Blanco, J. M. A., & Fernández-Costales, A. (2018). Assessing the influence of socio-economic status on students’ performance in content and language integrated learning. System, 73, 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.09.001

- Sarwat, S., Peter, M. N., Ullah, N., Bhuttah, T. M., & Peter, N. D. (2021). Implementation of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in Rahim Yar Khan: subject teachers’ vantage. Multicultural Education, 7(6), 182–188. http://ijdri.com/me/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/18.pdf

- Tsuchiya, K., & Murillo, M. D. P. (2019). Conclusion: CLIL—reflection and transmission. In K. Tsuchiya & M. D. P. Murillo. (Eds.), Content and language integrated learning in Spanish and Japanese Contexts (pp. 403–407). Palgrave Macmillan.

- UNESCO. (2014). Teaching and learning: Achieving quality for all (9231042556). http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002256/225660e.pdf

- Vithanapathirana, M., & Nettikumara, L. (2020). Improving secondary science instruction through Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in Sri Lanka. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching, 7(1), 141–148. http://192.248.16.117:8080/research/handle/70130/4719

- Xanthou, M. (2011). The impact of CLIL on L2 vocabulary development and content knowledge. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 10(4), 116–126. https://edlinked.soe.waikato.ac.nz/journal/files/etpc/files/2011v10n4art7.pdf

- Yamano, Y. (2019). Utilizing the CLIL approach in a japanese primary school: a comparative study of CLIL and regular EFL lessons. In K. Tsuchiya & M. D. P. Murillo (Eds.), Content and language integrated learning in Spanish and Japanese Contexts (pp. 91–124). Palgrave Macmillan.