Abstract

Although WhatsApp has become so ubiquitous and widespread across the globe, it poses a risk of abuse and cyberbullying to vulnerable groups of people like intellectually disabled learners. This study explores intellectually disabled learners’ experiences of using WhatsApp during an intervention programme in a special needs unit at a school in Cape Town. The study was conducted using a qualitative case study within an interpretive paradigm. Nineteen participants who include intellectually disabled learners, parents/guardians and staff members were purposively selected to participate in the study. Data was collected using observations and interviews. It was found that all learners who participated in the programme were empowered to use the social media effectively and to become responsible digital citizens. The study concluded that a structured intervention programme provides a milestone of achievement in terms of preparing intellectually disabled learners to become digitally competent and to be able to use social media independently.

1. Introduction and background

Although the advent of technology presents multiple advantages in this contemporary digital era, one notable and unintended consequence is the way it is abused by some people, particularly learners in schools. Intellectually disabled (ID) learners who use WhatsApp are faced with a myriad of problems which come as a result of misuse experienced while using this application. In some instances ID learners are taken advantage of when they use WhatsApp. They are vulnerable to various online abuses as they often do not understand that they are being ill-treated while making use of the social media platform. Holmes and O’Loughin (Citation2012) contend that adolescents are potentially at risk online, especially with the prevalence of bullying and mistreatment of the ID. They are vulnerable to risks such as cyberbullying which is prevalent among school-going children (Beer et al., Citation2017) and it prevails via social media which sometimes becomes difficult to control. Due to their condition of intellectual impairment, these learners are more susceptible to becoming victims of online communication abuse (Vaillancourt et al., Citation2017).

There is a dearth of scholarship of ID learners’ experiences of using social media, especially WhatsApp, which is ubiquitous. The researcher was motivated to conduct this research because in the Special Needs Unit (SNU) where she taught, she noted her ID learners made ill-informed decisions when using WhatsApp. This resulted in many of her learners becoming victims of online abuse due to their lack of education and understanding of online social conduct. ID learners’ lack of knowledge about WhatsApp make them more vulnerable to various online social ills. Hence, this study seeks to investigate ID learners’ experiences of participating in an eight-week WhatsApp awareness intervention programme (IP) which empowered them to use this social media platform responsibly. The study is guided by two critical questions:

What were ID learners’ experiences of using WhatsApp during an IP in a SNU at a school in Cape Town?

How did the IP empower these ID learners in this SNU at a school in Cape Town?

2. Literature review

In 2016, the Department of Basic Education (DoBE) in South Africa developed a policy and learning programme for ID learners. However, despite this learning programme identifying that “there will also be a need to develop … skills of social interaction with adults and peers”, there was no inclusion of digital communication or online social skills (DoBE [Department of Basic Education], Citation2016, p. 9). Unfortunately, this leaves a void where ID learners are given online access, but are not supported holistically, especially in the area of social development within an education environment. The situation of ID learners facing exclusion or vulnerability to cyberbullying has increased during the COVID-19 global pandemic (Courtenay & Perera, Citation2020). There is a need for ID learners to be supported in using digital communication like WhatsApp otherwise they will face challenges which include sexting and cyberbullying. Chadwick et al. (Citation2016) argue that demonstrating responsible social behaviours online, managing difficult situations such as sexting or ensuring protection from cyber strangers, are but a few of the challenges that face moderately ID learners who use online communication such as WhatsApp.

Due to the learners’ ID diagnosis they may experience limitations in accessing WhatsApp due to poor motor skills or literacy and language barriers (Alberto et al., Citation2007). Some may have access to social media, but because of their neurodiversity, they may not be able to fully understand how to use it in ways that are acceptable. Smith et al. (Citation2019) argue that some ID learners have a problem with comprehension, decoding and expressing themselves clearly on text message using a platform like WhatsApp. This necessitates some intervention programmes to assist ID learners on how to use social media effectively and carefully. Alberto et al. (Citation2007) and Smith et al. (Citation2019) argue that there is a need to teach ID learners basic skills of using different applications (such as WhatsApp) to improve their independence in digital communicative interactions.

3. Theoretical framework

Garrison et al.’s (Citation2000) Community of Inquiry (CoI) was used as a theoretical framework in this study. The theory originates from a constructivist’s view of learning and it consists of three interconnected components: Teacher presence, cognitive presence and social presence.

Teacher presence involves an instructor being actively involved in the facilitation of students’ learning. He/she will be responsible for designing, organising, facilitating and direct instruction (Anderson et al., Citation2001) in order to ensure that learning is going in the right direction. Students will be given tasks to complete and the presence of a teacher ensures learning takes place and achieves the stated outcomes.

Cognitive presence requires students to use their critical thinking skills to solve problems and construct meaning and understanding through deep and sustained reflection (Garrison, Citation2015). Students will conceptualise problems, explore, hypothesise and provide a resolution (Garrison, Citation2007). This challenges students to use their higher order thinking skills to solve educational problems posed to them by the teacher.

Social presence, as the name suggests, involves student collaboration, open communication, group cohesion and affective expression (Garrison, Citation2007). Social presence enables students to interact among themselves and with the teacher extensively as they share ideas and new insights. Although the CoI is more suited to online learning, it is relevant to this study as it involves the interdependence of the three components of the theory (social, teacher and cognitive).

4. Methods

Using an interpretive paradigm, this qualitative case study focused on vulnerable ID learners’ in-depth understandings and experiences of using WhatsApp during an eight-week IP (Denscombe, Citation2010). A case study design was chosen for this research as it focused on a specific group of participants within a particular context—the ID learners in a SNU (Yin, Citation2014).

The site at which this research was conducted was School X (pseudonym) which was an urban, independent, mainstream school in Cape Town. The school is located in the Western Cape in South Africa, catering for learners from pre-primary to Grade 12. Within the school there is a SNU which hosts 18 learners with ID between the ages of 10 and 20 years. The unit has two classes. In each class there is a class teacher as well as a teacher assistant. The division of the learners into two classes is dependent on their age and intellectual ability in subjects such as Mathematics and English. The parents of these learners in the SNU were actively involved in their children’s learning, often visiting classrooms before and after school, rendering their services where required. I selected this site since it provided a safe space for my ID learners where they were familiar with the staff, peers and parents.

Nineteen participants were purposively selected: eight ID learners, eight parents/guardians of the ID learners and three staff members that taught Social Skills and Information Communication and Technology (ICT) to the ID learners. According to Cohen et al. (Citation2011), in qualitative research purposive sampling permits the researcher to select participants who could provide in-depth information about the phenomenon being investigated. Etikan et al. (Citation2016) suggest that purposive sampling is criteria-based and participants share similar qualities, characteristics and experiences regarding the phenomenon. Hence, Table describes the participants, including learners and the parents/guardians:

Table 1. Details of the participants in this study

Three members of staff who worked in the SNU were invited to be part of this research as they taught the ID learners Social Skills and ICT lessons and were objective non-participant observers. All eight learners attended School X and were in the SNU. Seven learners (Ls 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) were clinically diagnosed by independent psychologists as ID with moderate intellectual functioning. L2 was the only student who was in the unit without a clinical diagnosis at the time of the research project. Previously he had been in a mainstream school but was unable to cope with the academic level. Many of the learners had been introduced to using WhatsApp by their neurotypical siblings, parents or peers within the mainstream school. As the learners’ WhatsApp use increased, so the need to discuss issues such as privacy and sexuality in WhatsApp also increased. Hence, these skills were taught during the Social Skills lesson. All the parents/guardians were included in this research project as they understood the limitations of the learners and could speak on behalf of them.

In order to obtain in-depth information about the learners’ experiences during the IP, four data collection methods were used: i) pre-IP interviews with the eight parents/guardians and three staff members, ii) weekly questionnaires using Google forms for the eight parents/guardians during the IP, iii) participant observations conducted by the Head of Department (HoD) (S1) during each session of the IP and iv) one-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with three staff members (S1, 2 and 3) prior to the IP to elicit appropriate detail about how their online and WhatsApp skills were taught and any concerns or observations they had made about the ID learners’ use of WhatsApp. Semi-structured interviews allowed for probing questions to be asked as they emerged during the interviews in order to elicit explicit information (Jamshed, Citation2014). A limitation of using these data collection tools was that they were time consuming. Since the eight learners (L’s 1–8) experienced challenges with face-to-face communication they were not interviewed.

Participant observations conducted by the researcher and three staff members were used to observe learners in their natural setting during the IP (Yin, Citation2014) and this enabled the researcher to experience a first-hand account of the ID learners’ experiences. The learners were familiar with S1 being in the class and this caused no disruption to them. She sat at the back of the classroom, being a non-participant observer who would make notes on an observation schedule during each lesson. This freed the researcher up to observe learners’ behaviour, their shared verbal experiences, group interactions and tasks and finally the products of their work during the IP. The learners’ tasks were documented, reviewed and analysed.

The IP was conducted over a period of eight weeks in the SNU classroom. Two sessions of 45 minutes took place twice a week during school hours replacing the “social skills and sexuality” lessons. Various online, social and digital skills in the use of WhatsApp were taught by the researcher. The lessons were practical and included repetition, visual aids, verbal discussions, collaborative group tasks, paired discussions and sharing of experiences.

After transcribing all the data, the researcher sent the transcripts back to the original interviewees for them to check if their responses were captured accurately. Atlas.ti was used to complete inductive data analysis. The researcher summarised the many words into a few categories which were based on theories and experiences of the IP and literature review. The researcher began to recognise patterns and similarities which were colour-coded, and finally data was organised using coding and labelling (Creswell, Citation2012).

Triangulation was acquired through the collection of data from the ID learners, their parents and the staff members. Trustworthiness was ensured since the researcher had transcribed the transcriptions and these were sent back to the eight parents and three staff members to check for accuracy. The interview and observation schedules were trialed before the main data was collected. The researcher asked the principal and HoD (S1) if they would like any changes to be made, but they felt that none were required. The interview and observation schedules were checked and approved by the principal and Head of the SNU. Ethical clearance was obtained from the university where the researcher was registered (EFEC 8–5/2018) as well as from the Independent School Governing Body. Consent forms were signed by the principal, teachers and parents participating in the study. All participants were assured of anonymity, confidentiality and understood that they could withdraw from the research at any time. To enable all ID learners’ comprehension, an adapted, simple assent form (Appendix 1) was created to aid in their understanding.

5. Results

Results presented in this section are grouped according to three major themes which emerged from the inductive analysis of this study. These include: i) enabling easy and accessible communication with ID learners, ii) empowering ID learners to use WhatsApp with increased independence and iii) the development of online skills, with sub-themes: a) the development of WhatsApp skills, b) online etiquette and c) responsible digital citizens. The first theme answers the first research question about ID learners’ experiences of using WhatsApp. The second and third themes answer the second research question about how the IP empowered ID students.

6. Theme 1: Enabling easy and accessible communication with ID learners

ID learners were using WhatsApp as a communication tool to easily and affordably communicate with a vast range of people. One of the positive aspects of ID learners using WhatsApp is that it provided a means of communication which is easy to use and accessible to many individuals despite their limited ability to type or speak. S1 supported this view explaining:

It [WhatsApp] has the emojis and the voice recording as well, which are really great for some of our learners who cannot type a message, but they can now voice record. You can also listen to other people’s messages if they have done a voice recording, so it has benefitted quite a few learners, especially those with intellectual difficulties. [S1]

Similarly, P7 echoes the same sentiments about WhatsApp being an easy and accessible communication tool for her ID child:

My child, although he is verbal, experiences challenges in face-to-face communication, however, WhatsApp has provided him with an opportunity to access communication. It has given L7 a voice. He is actually quite difficult to have a conversation with and it [WhatsApp] has given him a voice. [P7]

The social media platform has enabled ID learners to connect with their family, friends and other people. During the IP the eight learners compiled a list of people they were currently communicating with on WhatsApp. Learners were encouraged to scroll through their WhatsApp contacts and identify who they were chatting with in addition to family members. Each learner compiled a list of names, sorting them into categories, identifying who they communicate with on WhatsApp, as can be seen in Table .

Table 2. A list of people whom Ls 1–8 identified they communicated with using WhatsApp

The relationship terms stated at the top of Table formed part of the selected terminology taught to the ID learners during the IP. Many of the terms such as a friend, good friend, best friend, acquaintance and colleague are terms that have been previously taught as part of the Social Skills lessons in the SNU and the students were familiar with these classifications. The majority of the ID learners were actively communicating with some form of a friend, whether it is a best friend, a good friend or just a friend. Two learners, Ls 1 and 8, identified that they were chatting with online friends who they had not met before, while two other learners, L4 and L6, spoke to strangers on WhatsApp. Parents concurred that WhatsApp enabled their children to frequently communicate with their friends. Three parents (Ps 2, 5 and 6) narrated that:

With L2 being such a sort of shy, almost introverted type child, WhatsApp has almost given him a platform to voice his opinion and be more social with his friends. It has given him a sense of belonging, a connection with peers his own age, and I think he is really enjoying that. [P2]

The positive thing [L5] for him is keeping in contact with his friends and the joy that this brings him, especially since he has moved schools. I think that WhatsApp has probably also helped him to stay in contact with those friends from his previous school. WhatsApp just keeps him [L5] in contact with his friends. I think it is just an easy, modern way to communicate now. So it really is their form of communication and it is just a very convenient easy way. [P5]

… friends from the SNU, friends from her previous school and from Milner School [pseudonym] and from previous school situations. L6 created a group for the friends that were coming to her birthday – with chats prior to the party as well as posting pictures afterwards … L6 arranges things like play days and parties and she will send out invitations … sometimes they [friends] will WhatsApp call each other. [P6]

The spread of communication with a variety of people shows that the majority of learners were using WhatsApp to communicate with friends in various friendship circles. Excluding family, the second-highest communication after friends is taking place with acquaintances and mentors. It is noticeable that ID learners were speaking to other people who were less familiar with WhatsApp, such as their work colleagues from their work-skills training. This indicates that they were broadening their communication networks by using WhatsApp.

Some learners were using social media to communicate about education-related material and to get guidance from their teachers. This was supported by S2 who shared:

When they [the learners at school] are doing projects and they are unsure, they can get hold of the teacher, maybe they can ask one of their classmates you know, but it needs to be at that kind of level where they are confident and comfortable in using it.

7. Theme 2: Empowering ID learners to use WhatsApp with increased Independence

While accessing communication had been a positive experience, another notable benefit from the use of WhatsApp was the empowerment of ID learners to communicate with increased independence. S1 observed that all the learners were able to use WhatsApp with ease and send messages to other people autonomously. She stated: “they [all the learners in the class] all have WhatsApp and each other’s numbers. They are all in groups and communicate on these chats. So they definitely are using it on their own.” Parents concurred that the IP empowered their children to use WhatsApp autonomously. P5 said: “ … my son figured it out himself. He has never asked me for help and in fact, I probably would be asking him.”

Similarly, P1 echoes the same sentiment about her child’s autonomy on WhatsApp: “ … it is amazing how technologically clued up they [ID learners] are. In fact, she [L1] knows more about how to do stuff on WhatsApp than I actually do.” P7 reiterates the same point of her child’s increased independence on WhatsApp saying: ” … he changes the settings and things on the cellular network. The other day his usual cellular network was down and he said, “Oh mom I have moved to a different cellular network because my usual cellular network is down”.” Through the IP, children acquired more than just WhatsApp skills. They learnt a lot of things which included changing networks and navigating through a cell phone’s settings. P3 posited: “ … these little kiddies know everything about these things [WhatsApp skills]. P8 concurred by saying: “L8 just kind of knows how to do everything. Some of the stuff he [L8] actually shows me.”

During the IP, the researcher recorded that both Ls 3 and 8 had been able to change their privacy settings on WhatsApp independently. L8 mentioned that his mother had shown him how to change the settings before he edited his settings on his own phone. The researcher noted that a few of learners had blocked unknown numbers on their WhatsApp after the IP lesson on “Blocking strangers”. When the researcher enquired, some learners responded that they had done it on their own when they did not recognise the number. L7 said: “I have three blocked contacts” and L1 said: “I have blocked twelve.”

It appeared that the learners were digitally competent; they were able to use the features WhatsApp offered. Three of the parents (Ps 1, 5 and 8) stated that their children were capable of using the application and it was likely they were able to teach them, as parents, about the skills required, rather than the other way around. P1 said: “She [L1] just knows it, how to do it … in fact, she knows more, knows more how to do stuff than I actually do.”

Through the IP, learners were all empowered to use WhatApp with increased independence. They learnt some new skills which they ended up teaching their parents. PS said, “for him [L8] it’s been quite easy to do all these things and I think because he does it with his friends also. That is why it is so easy. Some of the stuff he actually teaches me.” Some learners learnt the skills from the IP and friends and family. This was supported by P5 who said,

I have not specifically taught my son any WhatsApp skills, but acknowledge that between his friends and brothers he had been able to acquire many of the skills … I think pretty much, he with, you know, friends or his brothers, figured it out himself – but he has never asked me. In fact, I probably would be asking him. [P5]

8. Theme 3: Development of WhatsApp skills, online etiquette and responsible digital citizens

As parents’, learners’ and staff’s communication increased during the eight-week IP, there was a positive development in other skills including the learners’ development of WhatsApp skills, an increase of appropriate “online etiquette” and an indication of improved “digital citizenship”.

8.1. The development of WhatsApp skills

During the IP, it became evident that there were several functional skills in using WhatsApp which were lacking or had not been taught to the ID learners. The first skill needing to be taught was displayed by L8 which was understanding how to save contacts onto his phone. Although this is not strictly a WhatsApp skill, it has a direct link to viewing contacts on WhatsApp when the application is opened. In the observation schedule in Week 2, S1 identified this ineptitude outlining that: “L8 did not know how to save contacts. He only had a list of numbers and seemed to memorise who some numbers belonged to.” During the IP, L8 was shown how to save contacts to his phone and how this would transfer the information into WhatsApp, so when he looked at his chat list, he would be able to see the name of the person he would like to communicate with. The following lesson, S1 noted in her Week 3 observation schedule that L8 had now developed the skill of saving his contacts to his phone and mentioned that: “L8 was able to save numbers and add their contacts—change from previously.”

During the IP there were various skills which were taught and developed including those that focused on teaching learners about creating groups, taking a screenshot, creating a status and changing privacy settings. Parents provided feedback confirming that these skills had been developed. Parents confirmed that through the IP, their children learnt how to create WhatsApp groups. P2 confirms this saying: “ … he [L2] is excited about the fact that he knows how to start a WhatsApp group by himself which he couldn’t do before.” P8 confirms that her child learnt to create a WhatsApp group. She postulated:

He [L8] told me about creating group chat and that one is able to invite as many people as they want and also able to leave the group. He [L8] was able to use WhatsApp but I think he wasn’t quite sure about the things. He [L8] was telling me [today] about like creating a group chat etc. So, the class [IP] has benefited him.

Similarly, P6 was excited that her child learnt how to create a WhatsApp group. She said: “L6 created a group for our family, fabulous!” The following week P6 reported back that her daughter had continued to develop this skill of creating a group and had started a new group for her birthday. P6 commented that: “L6 is really operating! She created a group for the friends that were coming to her birthday—with before chats and posted pictures afterwards.”

Another WhatsApp skill which was developed through the IP is how to take a screenshot. By the end of Week 3, all learners except L8 had independently completed the homework task of taking a screenshot of their chat list. This skill was revisited in Week 7 where learners were required to screenshot examples of spam or a scam message that they had received. In this case, all learners except L2 who was not completing homework tasks had successfully taken at least one screenshot and shared this with the class group on WhatsApp. During the process of the IP, there was a marked improvement in this skill and it had been retained by all learners in the group. P4 confirmed her child’s acquisition of the screenshot taking skill by saying: “(L4) was very excited and demonstrated how to do a screenshot. (L4) showed our domestic lady as well … (I learnt something new).”

Children were taught how to create WhatsApp status and change privacy settings. P2 and P7 commented on their children’s abilities to create a WhatsApp status. P2 said: “ … he [L2] is excited to be able to do the following by himself … be able to change his status and able to update profile pic.” P7 said: “L7 … is sharing statuses more often.” P3 confirms her child’s acquisition of skills related to changing settings on WhatsApp. She posited:

She [L3] has helped me by showing me how to do certain things and how to change settings … She [L3] has also changed her own privacy settings on all her social media platforms and has become very interested in who is seeing what and what to put on to her social media … she [L3] is very proficient on WhatsApp now and knows all the settings.

Similarly, P4 reported on her child’s abilities to change privacy settings, which is a skill he did not have prior to the IP. P4 said: “ … he [L4] showed me how to set my privacy, last seen … [and] explained to me that the WhatsApp dept [administration] has access to all our information, even on pc [the computer], and can transfer numbers to anyone.” P8 reported on her child’s acquisition of privacy settings skills saying: “ … this week he [L8] showed me how they can protect themselves by using the WhatsApp settings.”

8.2. Online etiquette

Social skills form a large part of special needs education. Similarly, it is necessary that online social skills and using appropriate social etiquette when using social media be taught. During the IP, social etiquette was taught and rules around group chat etiquette were also explored. Over the eight weeks, various positive feedback regarding improved WhatsApp etiquette was given by parents. Although the parents provided much feedback in this area, only one comment has been selected from each parent to highlight this learning:

P1 She [L1] relayed to me about appropriate behaviour and inappropriate messages and behaviour of how to be on WhatsApp. L1 always says that she must be polite on WhatsApp.

P2 He [L2] used to WhatsApp people all the time before getting a response. He has now told me that he needs to wait for the person to respond before sending more messages.

P3 L3 says she rereads the message to make sure it is saying what she means and what she would like to say, that it is all true.

P4 Awareness and rude behaviour … explained to me.

P6 L6 is writing us very nicely worded messages since she is in your WhatsApp classes, always starting with a greeting.

P7 L7 doesn’t seem to spam/hound everyone on his contact list anymore. He is more selective about who he messages. He is also less demanding with requiring replies. He [L7] has a greater awareness of the WhatsApp etiquette.

P8 L8 learned that he should greet on their group chat before texting. I asked him about the other etiquettes (mentioned in the question) and he is aware of them.

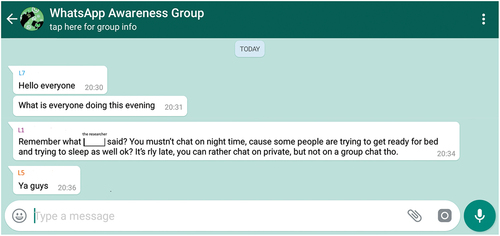

During the IP, learners began to remind one another about appropriate online etiquette. P7 identified that: “His [L7] peers continue to correct him when he isn’t adhering to the etiquette … in his messages.” Figure below is a screenshot of a chat that took place in the evening between three of the learners in the IP where they were discussing appropriate etiquette when chatting in a group.

Throughout the process of the IP, ID learners improved their skills on how to respond to strangers online. A parent [P3] confirms this by saying:

L3 has indicated that she now knows better how to deal with messages from someone she doesn’t know. She has mentioned that before she would say a few lines before blocking a stranger. Now she knows to block strangers immediately without even talking to them at all.

Similarly, P6ʹs child learnt the skill of being conscious of strangers and how to respond to them and responded:

I was impressed to see that after receiving a photo taken at the Craft day from an unknown number, L6 responded: “who is this”. The message returned: Miss June [pseudonym]. She is much more aware and follows advice she received in the class. For example, when her cousin’s boyfriend congratulated her on her birthday without telling her who wrote the message, she politely asked him to identify himself.

Some learners dealt with strangers by informing their parents, as was confirmed by P8 who shared:

… he [L8] knows now the importance of checking with me should a stranger try to befriend him on WhatsApp cause they might not be who they say they are.

8.3. Responsible digital citizens

One of the most significant findings was that the ID learners had been empowered to become responsible digital citizens who were aware of their actions and reactions on WhatsApp. This was confirmed by parents whose feedback suggested that there were various indications that digital competencies had been developed and that their ID learners were beginning to become more responsible digital citizens. Two parents (P2 and P5) confirmed this stating:

Creating awareness about WhatsApp and how to use it correctly. Many of the topics covered helped him gain a better understanding on the digital world. What he has access to. How to be safe online. It has created an awareness. He feels more in control and has a beter understanding of how to use WhatsApp appropriately. [P2]

I think it [IP] has created an awareness of the possibilities and pitfalls with using WhatsApp. He [L5] has really enjoyed the classes, it has created an awareness around both the positive and negative outcomes of using WhatsApp. I feel that he has really benefitted from the classes. I think a bit of a learning curve for L5 to understand digital privacy. I don’t think it has been an issue to date, but it is great that he is aware. I just think it has been the awareness of the various aspects of the use of WhatsApp that have been beneficial for him, the responsibility of social media and appropriate behavior. [P5]

All parents reported that the IP was beneficial to their children as it was an eye opener which created awareness on safe ways of using the social media platform (WhatsApp). Parents confirmed that through the IP, their children knew a lot of things that they did not know. P1 stated:

She [L1] became aware of issues that she never thought of. I think L1 was shocked at some of the implications which gave her food for thought. Knowing boundaries on social media is useful and beneficial to keep one out of harm’s way.

Similarly, P8 concurred that her child learnt new things which made her realise risks associated with the social media and how to become a responsible digital citizen. She said: “I think he realises now that there are potential risks in using WhatsApp. What kind of problems he could encounter, he is aware and knows what to do and not to do should anything inappropriate happen.” Learners learnt the dos and don’ts of WhatsApp which defined them as digital citizens. P7 confirmed this saying: “L7 has become more aware of the dos and don’ts although he still falters in the category of accepting ‘friend’ requests and sharing personal information.”

Ps 2, 3, 4 and 6 also commented on the IP and how it was instrumental in creating awareness among ID learners in order to become responsible digital citizens:

[The IP classes are] creating awareness about WhatsApp and how to use it correctly. He [L2] is very aware of it now and shows me when he thinks he is getting spam so that he can delete it. [P2]

She [L3] is much more aware of who her contacts are and how she talks to friends. I think L3 thinks about whether it is true, important and necessary. She [L3] is not on her phone with so many people anymore. She seems to have selected a few friends that she [L3] has made important. She [L3] is very aware of how she uses her WhatsApp and is much more concerned about her privacy and information that she [L3] sends. [P3]

He [L4] … discusses the WhatsApp rules. No sexting/nude pics, be kind, no swearing, not being rude, being respectful to others (P4). I was told quite explicitly by L4 about all the different types of contacts. [P4]

She [L6] felt that she would rather discuss a problem [for example, if she received a message that made her uncomfortable] with my sister Hayley [pseudonym]. L6 is much more aware about the dangers lurking out there since the start of the classes. [P6]

9. Discussion

WhatsApp has often been used in education, however little has been found in recent literature about the benefits of social media, specifically WhatsApp and special needs education, particularly with ID learners. A further tension is that the use of WhatsApp in secondary schools has mainly been used for organisational issues, to allow for easy communication access between students and teachers and to create communities.

There was a need to teach these ID learners WhatsApp online etiquette for them to develop social and cognitive skills of appropriate uses of WhatsApp and for them to be independent users. The DoBE [Department of Basic Education] (Citation2010) document states that digital literacy has a valuable place in the curriculum for ID learners as it forms a modern part of learning where ID learners can develop skills that will assist them throughout life. This document also introduces the term “netiquette” within digital platforms and suggests that learners should be informed about the rules surrounding this. This was the case in this study where ID learners were taught appropriate “netiquette” on WhatsApp and were able to improve this skill and achieve success in communicating more appropriately with others.

The CoI helped to understand the complexities of this study. The aspect of learners contacting a teacher using WhatsApp while doing an assignment falls within the teacher presence of the CoI (Garrison et al., Citation2000). In this context of teacher presence, the researcher did not only design the IP but I facilitated it and provided explicit instruction to all the learners, thereby being a crucial part of the learning process and contributing to the learners’ understanding of using WhatsApp as a communication tool. Teacher presence is indispensable in the learning of ID learners. Browder et al. (Citation2008) argue that a teacher is need to facilitate participation in the learning process and assessments of students with cognitive disabilities or ID. Similarly, Browder et al. (Citation2012) contend that teacher play a fundamental role in supporting students with moderate ID to succeed in different subjects including Mathematics. ID learners who participated in this study acquired skills on how to use WhatsApp effectively and responsibly as they were supported through teacher presence. This concurs with results of a study conducted by Smith et al. (Citation2019) who postulate that ID improved the quality and independence of digital communicative skills through experience they had of using digital messaging applications and support they had from instructors.

The social presence was perhaps the most important aspect of this research project, as despite the learners’ ID condition, where they struggled to verbally communicate, using WhatsApp increased their ability to have open communication with friends, family and even strangers and they managed to work well and supportively within groups and with each other. Peer interaction among ID learners is critical as it helps them learn new knowledge and develop digital skills (Carter et al., Citation2008). Similarly, Browder et al. (Citation2008) concur that interaction of ID learners is essential as it increases performance and academic achievement. In this study, interaction of ID learners through WhatsApp helped them gain knowledge and skills which enabled them to become digital citizens. Carter et al. (Citation2005) argue that interaction among ID learners have to be promoted as it provides a milestone of achievement in terms of their skill acquisition. CoI’s social presence enabled ID learners to learn to communicate more appropriately with others.

The cognitive presence was also noticeable in this research project as the learners used their thinking skills to develop and apply their abilities to explore, acquire and apply new functions on WhatsApp to become autonomous users. Ngubane-Mokiwa and Khoza (Citation2021) contend that cognitive presence is evident in special need students’ learning as they will be using their critical thinking skills to solve problems. ID learners in this study learnt digital skills from the IP which enabled them to know how to exercise caution when using the social media and to assist some family members with setting up the platform. The importance of digital literacy skills being included in ID education programmes is that these learners have been included into a digital society where they can function and increase their independence. Through participating in the IP, they delved deeper into various netiquette and digital competency skills to become safe digital citizens; they learnt issues such as safety and online privacy, developed a digital identity, created a lasting online footprint, learnt appropriate communication skills and even came up with practical solutions.

10. Conclusion

The study set out to determine ID learners’ experiences of using WhatsApp during an IP in a SNE at a school in Cape Town, and how this experience empowered these eight ID learners. Since there is little empirical research in this particular area of introducing ID learners to using WhatsApp, the results of this investigation show conclusions may be drawn from this unique study. A significant finding of this research project was, as the evidence suggests, that the ID learners in this programme benefitted from technical WhatsApp skills being explicitly taught during the IP. Despite their limited ability to type or speak, these eight ID learners, who were vulnerable and often victims to cyberbullying and abuse, learnt to communicate with friends, family and even some online strangers using WhatsApp, an easy and affordable tool. During the IP, they became more digitally competent to use this platform to independently change their privacy settings on WhatsApp, to block unknown numbers, to save contacts onto their phones, to create groups, take screenshots and create a status. An important learning lesson emerging from this study was that not only did the ID learners learn the importance of online netiquette, but they also learnt to support each other to be more aware of the risks. All the parents commented that the IP empowered their learners to become responsible digital citizens while using this social media platform.

The study had the following limitations: Firstly, the researcher found that digital skills developed through smart phones alone would be limited and that students would get greater access to digital literacy skills if using a laptop or computer. The second limitation is that the study was conducted with only eight adolescent learners in one SNU at one school. Further studies may include continuing this study in this town and in other provinces of South Africa with learners of all ages and inclusive of a variety of abilities. A vital reflection emanating from this research is the training of teachers in special needs classes to include explicit teaching of a variety of social media platforms, focusing on the risks and the benefits.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alberto, P., Fredrick, L., Hughes, M., McIntosh, L., & Cihak, D. (2007). Components of visual literacy: Teaching logos. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22(4), 234–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576070220040501

- Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2). http://www.aln.org/publications/jaln/v5n2/v5n2_anderson.asp

- Beer, P., Hallett, F., Hawkins, C., & Hewitson, D. (2017). Cyberbullying levels of impact in a special school setting. The International Journal of Emotional Education, 9(1), 121–124. https://www.um.edu.mt/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/313215/v1i9rr.pdf

- Browder, D. M., Flowers, C., & Wakeman, S. Y. (2008). Facilitating participation in assessments and the general curriculum: Level of symbolic communication classification for students with significant cognitive disabilities. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 15(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940802164176

- Browder, D. M., Jimenez, B. A., & Trela, K. (2012). Grade-aligned math instruction for secondary students with moderate intellectual disability. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 47(3), 373–388.

- Carter, E. W., Hughes, C., Guth, C. B., & Copeland, S. R. (2005). Factors influencing social interaction among high school students with intellectual disabilities and their general education peers. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 110(5), 366–377. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110366:FISIAH2.0.CO2

- Carter, E. W., Sisco, L. G., Brown, L., Brickham, D., & Al-Khabbaz, Z. A. (2008). Peer interactions and academic engagement of youth with developmental disabilities in inclusive middle and high school classrooms. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 113(6), 479–494. https://doi.org/10.1352/2008.113:479-494

- Chadwick, D., Quinn, S., & Fullwood, C. (2016). Perceptions of the risks and benefits of Internet access and use by people with intellectual disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12170

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research Methods in Education (7th) ed.). Routledge.

- Courtenay, K., & Perera, B. (2020). COVID-19 and people with intellectual disability: Impacts of a pandemic. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 37(3), 231–236. Epub. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.45

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th) ed.). Pearson.

- Denscombe, M. (2010). The good research guide for small scale research projects (4th ed.). Open University Press.

- DoBE [Department of Basic Education]. (2010). Guidelines on e-Safety in schools: educating towards responsible and ethical use of ICT in schools. DBE. https://wcedonline.westerncape.gov.za/circulars/minutes18/CMminutes/del4_18.pdf

- DoBE [Department of Basic Education]. (2016). Draft policy for the provision of quality education and support for children with severe to profound intellectual disability. Department of Basic Education, Pretoria. http://www.educaiton.gov.za

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61–72. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/104064/

- Garrison, D. R. (2015). Thinking collaboratively: Learning in a community of inquiry. Routledge.

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. Internet and Higher Education, 2(2–3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

- Holmes, K. M., & O’Loughlin, N. (2012). The experiences of people with learning disabilities on social networking sites. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12001

- Jamshed, S. (2014). Qualitative research methods-interviewing and observation. Journal of Basic and Clinical Pharmacy, 5(4), 87–88. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-0105.141942

- Ngubane-Mokiwa, S. A., & Khoza, S. B. (2021). Using Community of Inquiry (CoI) to facilitate the design of a holistic e-learning experience for students with visual impairments. Education Sciences, 11(4), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040152

- Smith, C. C., Cihak, D. F., McMahon, D. D., & Coleman, M. B. (2019). Examining digital messaging applications for postsecondary students with intellectual disability. Journal of Special Education Technology, 34(3), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162643418822107

- Vaillancourt, T., Faris, R., & Mishna, F. (2017). Cyberbullying in children and youth: implications for health and clinical practice. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry/La Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 62(6), 368–373.

- Yin, R. (2014). Case study research: design and methods. Sage Publications.