Abstract

This study was aimed at understanding students’ academic self-concept, academic help-seeking behaviors, and beliefs in counseling service effectiveness. Based on a correlational research design, a closed-ended questionnaire was administrated to 182 college students. Independent-sample t-test revealed that male students’ average score was significantly higher than female students’ average score in academic self-concept, help-seeking behavior, and belief in counseling effectiveness. Analysis of relationship confirmed that academic help-seeking behavior, belief in counseling service effectiveness, and academic self-concept significantly correlated each other. This study also revealed that the variance of academic self-concept and belief in counseling service effectiveness contributed to 36% of the variance in academic help-seeking behavior. Therefore, enhancement projects on academic self-concept and female students’ belief in the effectiveness of counseling services should be taken as an agenda by teachers, college administrators, academic advisors, and counselors.

Education is the cornerstone in boosting the psycho-social and economic dimensions of nations. Ethiopia has been investing much in accessing and providing quality education for the citizens than ever before (Ministry of Education [MOE], 2018; Bloom et al., Citation2006). Access to education through opening many colleges has been one of the major investments in the country. College education is fundamental for students, higher institutions, policymakers, parents, and other stakeholders at large(Fittrer, Citation2016). However, it is a myth to assume that all tertiary educational institutions are peaceful places for students. The transition from the protected environment at home and school to the independent life and tertiary educational institutions has been stressful due to physical, mental, and emotional adjustments (Greenidge, Citation2007) because most of them live away from home and join the learning system, which is entirely different from high school (Greenidge, Citation2007; Njoka, Citation2014). One way to cope with such stressing situations is developing positive academic self-concept because a high academic self-concept is regarded as important for good mental health, improving academic achievement that lead to college success (Guay et al., Citation2003).

Academic self-concept implies understanding the potential, motivational interest, analytical insight, and comprehension of academic disciplines of our previous knowledge, engaging in ongoing learning and for the future (Gilbert, Citation2007; Schunk, Citation2012). Academic self-concept is overall-comprehending in self-confidence, self-esteem, self-assertive, and self-competency in the given unique subject matter (McGrew, Citation2018; Schunk, Citation2012).

Another way to get relieved from stressing environment is getting adequate help from guidance and counseling services. Counseling services help students experience psychological well-being and mental wholeness that lead to academic excellence (Corey, Citation2005). Students could potentially get adequate support as per their help seeking behavior. Academic help-seeking behavior is an interest and motivation of someone else that is originated or sourced from internal intention. It is not more emanated from external pressure since intrinsically motivated individuals are knowledge searchers or mastery learners based on their goal sets (Schunk, Citation2012).

The academic help-seeking behavior of students can be influenced by their prior knowledge, self-regulation, epistemological belief, and goal orientation effect (Koc, Citation2016). Fittrer (Citation2016) also argued that it is a need for help from others without investing the necessary effort. A help-seeking model, designed for students, emphasizes the importance of deciding whom to ask for help. In this case, scholars wrote about who or what has to target to help learners’ perceived benefits and expenses of seeking help from that source person that impact their likelihood of soliciting help (Makara & Karabenick, Citation2013).

Theoretically, counseling service is originated from various psychological-based theories (Kabir, Citation2018). Reese et al. (Citation2002) figure out that effectiveness in counseling is the satisfaction of clients in overall situations such as the resolution of psycho-social troubles, academic distress, emotional and related personal problems. On the other hand, counseling service effectiveness is determined by clients’ characteristics such that motivations, interest, trust, or belief in getting satisfied with given services (Musika & Bukaliya, Citation2015a). It is essential to college students not only for their tentative academic performance or success (in the college period) but also it helps to stay on a long time in the education system (Onyango & Aloka, Citation2018).

However, counselors are generally poor at detecting a lack of client progress (Moloney, Citation2016). The result led to developing negative belief towards the counseling services. The counseling service effectiveness is meaningful if it focuses on helping students to adapt themselves to their schools (Kanga, Citation2017). Previous studies indicated that students have positive beliefs in counseling service effectiveness if they develop academic help-seeking behaviors and have a positive academic self-concept (Ng, Citation2014; Schunk & Ertmer, Citation2000).

Gender is also an influential factor in the likelihood and willingness of college students to engage in adaptive help-seeking behaviors as a self-regulated learning strategy. There are differences in treatment based on gender and the internalization of gender-based stereotypes (Matthews et al., Citation2014) throughout the lifespan in western culture. Fear of embarrassment about asking for help develops in girls earlier than boys (Newman, Citation2000). Female students usually seek more support from their immediate person than male students do during their period of adolescence (Makara & Karabenick, Citation2013). On the contrary, girls feel more warmth and assertion of capability from teachers than boys do (Newman, Citation2000). Compared to boys, girls tend to ask for more help as tasks get increasingly more difficult (Thompson et al., Citation2012). Benenson and Koulnazarian (Citation2008) reported that girls demand assistance more promptly than boys across age and socio-economic levels.

Another factor that determines girls’ help-seeking behavior is academic self-concept. Research results revealed that girls outshine boys on intellectual and behavioral self-regulation but not across standardized measures of academic achievement (Matthews et al., Citation2014). However, much more research on the relationship between gender and help-seeking exists for older children, adolescents, and adults. When children grow older, gender socialization plays a more role in how males and females think, feel, and act. For example, older girls begin to ask for the most help and consequently outperform older boys, younger boys, and younger girls (Thompson et al., Citation2012).

Previous research on help-seeking behavior has also helped to establish the importance of gender when considering possible sex differences in help-seeking behavior. Johnson (1988), as cited in Marrs et al. (Citation2012), examined the role of sex and gender attributes on help-seeking attitudes or attitudes towards counseling among college undergraduates. The result indicated that both gender and sex roles were important for understanding help-seeking attitudes. Researchers have also found that gender is a significant factor for self-identification development. Gender-typical behavior is found in individuals having their sense of self through the lens of gender (Baron et al., (Citation2014).). When examining gender differences in academic self-concept, country-level factors are present and influential (Goldman & Penner, Citation2016). A study conducted in 49 countries found that gender-egalitarian countries have minimal gender differences in self-concept, specifically academic self-concept (Goldman & Penner, Citation2016). Thus, this implied that country-level cultural perspectives influence self-concept, career choice, and gender.

Some studies found no statistically significant relationship between gender and academic self-concept. Females, in technical fields, had to go against negative cultural stereotypes through collaborative learning to succeed in male-oriented careers (Stout & Tamer, Citation2016). Females are shy to approach people around them like their elders in their respective homes. Some people argue that women are not capable of performing in academic posts. This stereotype of “expected failure” implies that society does not trust women’s capacity to achieve. Affirmative actions also feed ideas that women could believe they do not rely upon themselves (Anouka et al., Citation2015). Traditional gender roles influence the belief of what men and women are capable of doing/not doing at an early age (Haile et al., Citation2020).

The core problem of Ethiopian education is its poorness in its quality (World Bank, Citation2008) because the education system didn’t address gender equality and cultural influences. This led to gender stereotyping to be severe in Ethiopia. Previous research revealed that Ethiopian earlier school education could not enable girls and boys to develop minimum learning competence. The poor foundation of earlier schooling also led them to be less competent in high school and college education (World Bank, Citation2008). Hence, college students in Ethiopia today become unable to develop a positive academic self-concept (MoE and USAID, Citation2008), and they often go for cheating instead of being self-reliant. The Ethiopian education system still did not tailor strategies into practice to help girls come to schools (Bastian et al., Citation2013; Pankhurst et al., Citation2018; RISE, Citation2018). And it did not address the culture-based gender influence that goes of boys’ favoritism for education. In general, Ethiopia is one of the countries where gender equality is a vision but not yet a reality.

Previous researchers have been conducting studies on the relationships between academic help-seeking behavior, academic self-concept, and belief in counseling service effectiveness. Investigating the relationship between beliefs in counseling service effectiveness and help-seeking behavior (Al-darmaki, Citation2011; Laxson, Citation2014; Moloney, Citation2016) and counseling service effectiveness with academic self-concept (Barongo & Nyamwange, Citation2013; Olando et al., Citation2014) were some of the recent studies. Regardless of such studies done in western countries, the results may not address the nature of the issues in Ethiopia in which cultural influences could have attributions to the variables under the study.

According to Vuong et al. (Citation2022:2), “the serendipity-mindsponge-3D knowledge management theory” and Nguyen (Citation2021), “Mind sponge culture”, information-processing process needs an innovative approach to solicit our problems and instilling to get the right person, requiring help and trusted information sources. Thus, understanding prioritized factors which help students to get the right track for college success is vital. We shall target factors to exploit the students’ perceived assistances to reduce worries based on the existing mindset, information, and insights. Eventually perceiving a specific target as more important factor than others will determine the target that we choose. Hence, the following variables are considered as target variables that presumed to have impacts on students’ academic performances based on previous academic research results and works of literatures.

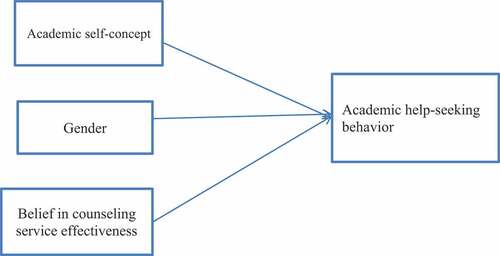

The assumption behind the conceptual framework as shown in is that the target variables would predict the criterion variable. Students’ knowledge of their weakness, strength, and gaps would be attributing factor to get help from counselors, teachers (“within-disciplines”), and more important other (“out-of-discipline”) stakeholders (Vuong et al., Citation2022). The other important factor is gender attributes to determine help seeking behavior from out-disciplines and within-disciplines.

According to the above framework, this study described the comparative status of college students’ belief in counseling service effectiveness, academic self-concept, and help-seeking behavior within gender. This study also scrutinized the relationship between study variables and identified which variable contributed more in predicting students’ academic help-seeking behavior. Depending on the conceptual framework above, questions were outlined:

Are there significant differences between male and female students in academic self-concept, help-seeking behavior, and beliefs in counseling service effectiveness?

Is there a significant relationship between academic self-concept, academic help-seeking behavior, and beliefs in counseling service effectiveness?

To what extent do students’ academic self-concept and beliefs in counseling service effectiveness influence their academic help-seeking behavior?

1. The objective of the study

The main objective of this study was to assess the relative predictive estimates of academic self-concept and belief in counseling service effectiveness to help-seeking behavior of college students. The study also aimed at comparing female and male students in academic self-concept, belief in counseling effectiveness, and help-seeking behavior.

2. Hypothesis

Null hypotheses were tested in the study:

H0i: Belief in counseling service effectiveness and academic self-concept will not predict variability of help-seeking behavior of college students.

H0ii: There will not be gender difference in academic self-concept, belief in counseling service effectiveness, and help-seeking behavior of college students.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

The study was conducted based on Pearson correlation design and followed a mainly quantitative approach. This study was conducted on education college students. All students (820) in Sekota College of Education (CTE) were sampling frames. I selected students by using stratified and systematic sampling techniques. Accordingly, batches (first, second, and third year), departments, and sections were considered as strata. The registrar’s office of the college had a complete list of students, so I identified individual respondents using a systematic sampling technique.

Yamane (Citation1967:886) provides a simplified formula to calculate sample size and the proportion from each stratum: n = N/ 1 + N (e‘)2, where a 95% confidence level that implies p = .05 is assumed for this equation; n is the sample size; N is the population size; and e‘ is the level of precision. With this formula: n = 820 ÷ 1 + 820 (0.05) 2; n = 269. Then, to get the sample size from each department, batch, and section, the proportional index was calculated by dividing the sample size by the total population (Proportional index = Total sample size/Total population = 269/820 = .33). The sample size was estimated by multiplying the population of each stratum by 0.33.

3.2. Instrument

A closed-ended self-completed questionnaire was the main data collecting instrument. The questionnaire sought data related to the academic self-concept, help-seeking behavior, and belief in counseling service effectiveness. Students’ academic self-concept questionnaire was developed by Bei et al. (Citation2007). The Academic Self-Concept Questionnaire (ASCQ) was adapted by restating (2), adopting (13), and inserting (1) words or ideas or items. The questionnaire was rated on a 5-point Likert scale as of 5 = Strongly Agree (SA); 4 = Agree (A); 3 = Undecided (UD); 2 = Disagree (DA); and 1 = Strongly Disagree (SDA).

Elhai et al. (Citation2008) designed help-seeking behavior items. Help-seeking behavior denoted the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale. In previous reliability estimates, the reliability of the academic help-seeking behavior scale was ranging from (r = .77) to (r = .84; Elhai et al., Citation2008). This scale assesses an individual’s attitudes toward seeking help from professionals. The researcher adopted eight items; restated eleven items; omitted six items, and inserted seven items of the questionnaire to be matched with the objective of the study. The questionnaire consisted of 26 questions in this study. The questionnaire has a 5-point Likert scale that ranges from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5).

The beliefs in counseling service effectiveness scale sought data related to beliefs towards counseling service effectiveness. Musika & Bukaliya, (Citation2015b) developed this scale. The researcher adopted this scale by restating thirteen items, omitting seven items, adopting seven items, and inserting five items of the questionnaire to be matched with the objective of the study. Items are rated based on a 5-point Likert scale that ranges from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5).

3.3. Procedures

A pilot study confirmed the reliability and validity of the questionnaires by translating them into the local language to minimize ambiguities on the part of the respondents. The questionnaire was given to 62 selected respondents. During the pilot test, the data collector informed the respondents to put question marks in front of each item that was not clear. Confusing questions were rephrased and modified to fit the purpose of the study. The questionnaire was given to three psychology educators to put their comments regarding items deserving with the title for validity check. The total drafted items for the main study were 66. On average, computation of split half-reliability coefficient resulted (r = .82) for final data collection. The data collection was made before the Covid-19 case official communication in Ethiopia. Following informed consent and delivery of brief orientation, the data collector gathered the question papers within the given day to enhance the response rate.

4. Data analysis

The data was structured and sorted in SPSS version 22 for analysis. There are two quantified predictor variables and one criterion variable, so the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient and multiple linear regression models were employed for analysis of the relationship. A Scatter plot was used to assess the goodness-of-fit of regression at a glance before actual analysis was conducted. The correlation coefficient and regression model estimated the degree of relationship and interactive contribution of independent variables. Adjusted R2 and F-test were used to interpret the result of the multiple linear regression models. Independent t-test, mean score, and standard deviations showed status and gender differences in academic self-concept, help-seeking behavior, and belief in counseling effectiveness among college students.

5. Compliance with ethical standards

Before administrating the questionnaire, informed consent was conducted with respondents. The data collector confirmed the confidentiality of responses. To ensure the safe running of the study, deans and other concerned bodies approved the research processes; then, researcher mobilized the data collection process safely.

6. Results

The first objective was to see differences in the status of male and female students in study variables. In response to this purpose of the study, mean scores, standard deviation, and independent-sample t-test were techniques employed for data analysis.

Table indicates that male students’ score (N = 91, M = 3.81, SD = 0.38) in help-seeking behavior scale was found significantly higher than female students (N = 91, M = 3.51, SD = 0.51), where df = 180, t = 4.48 at p < 0.01. An independent-samples t-test compared the mean scores in academic self-concept scale between male and female students. The result showed that male students scored significantly higher in academic self-concept (N = 91, M = 4.83, SD = 0.29) than female students (N = 91, M = 4.47, SD = 0.43) where t = 4.69, df = 180, p < .01.

Table 1. Gender difference in study variables

Furthermore, in Table , an independent-samples t-test was again employed to compare the mean scores of belief in counseling service effectiveness scale between male and female respondents. The results showed that male students’ average score was significantly higher in belief in counseling service effectiveness (N = 91, M = 4.44, SD = 0.30) than female students’ average score (N = 91, M = 3.98, SD = 0.50); t = 7.47, df = 180, at p < 0.01.

The second objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between study variables. Given the current data, the correlation between academic self-concept, belief in the counseling service effectiveness, and academic help-seeking behavior was statistically significant. The following indicates the correlational analysis result.

Table 2. Relationship between study variables

Table shows that academic self-concept, academic help-seeking behavior, and belief in the counseling service effectiveness positively and significantly correlated with one another. However, the magnitude of the relationship is different in each pair. Academic help-seeking behavior is significantly correlated with belief in the counseling service effectiveness at the degree of correlation coefficient (rxy = .59), p < 0.01. The belief in the counseling service effectiveness is significantly correlated with academic self-concept at the degree of correlation coefficient (rxy = .61), p < 0.01. It showed that students with higher academic self-concept have positive beliefs in counseling service effectiveness. Academic self-concept is significantly correlated with academic help-seeking behavior at the degree of correlation coefficient (rxy = .46), p < 0.01.

The third objective of this study was to investigate the magnitude of the contribution of predictive variables to the criterion variable. The following indicates the analysis result of the multiple linear regression coefficients.

Table 3. Model summary: effect of predictor variables on the criterion variable

When we square R = .60, we obtained (R2 = .36). R2 represents the correlation between all the explanatory variables and the criterion variable. The result implies all the variances (both shared and unique) of the predictive variables to the criterion variable from 100%. In our particular sample, variance of academic self-concept and belief in counseling service effectiveness contributed to 36% of the variance in academic help-seeking behavior.

shows that the explanatory variables significantly predict the criterion variable. In other words, we can understand that the variances of academic self-concept and belief in the counseling service effectiveness can interactively and significantly affect academic help-seeking behavior. The overall regression coefficient was statistically significant, F (2, 179) = 51.28, R2 = .36. In Table , we can also see the degree of importance of the explanatory variables by looking at the standardized weights (beta) and the level of significance. From the given explanatory variables, belief in the counseling service effectiveness (β = −.499, t = 6.64), p < 0.05, and academic self-concept (β = .152, t = 2.022), at p < 0.05, are independently significant predictors of academic help-seeking behavior.

Table 4. Model summary: status of predictor variables on the criterion variable as tested by F

7. Discussion

7.1. Status of males and female students in study variables

In response to the first objective of this study, the result revealed that male students’ average score in academic help-seeking behavior was significantly higher than female students’ average score. When students face academic difficulties like classroom learning, project work, assignments, and books, female students leave their roles to male students who seek more help from their peers, teachers, or anyone they believe solutions can be available. This may be because of cultural influence on girls that make them shy to seek help in psychological difficulties. In Ethiopia, most parents treat boys and girls differently. According to most Ethiopian parents, boys are supposed to man that claim to lead the house. They motivate boys to ask, talk, and brief what they want while girls are supposed to stay home and take the caring role instead of expressing their desire and aspiration. All these practices have the potential to make girls shy of expressing their social and academic difficulties and seeking help from teachers and counselors (UNICEF, Citation2006). However, the result of this study was different from previous research results on help-seeking behavior. Atkinson et al. (Citation1995) did not find gender differences in willingness to seek academic help from people around them. In addition, Masuda et al. (Citation2005) reported that Japanese males and females did not differ significantly in their academic help-seeking behavior.

The study also revealed that male students have higher levels of academic self-concept than female students as per the measuring scale. In Ethiopia, it has been believed that being male was being blessed while being female was not blessed. This sociocultural dichotomy brought gender-biased treatment of boys and girls that prone to adversities and challenges on girls (UNICEF, Citation2017/Citation2018/18). This may lead to a lower academic self-concept of female students. Evidence that supports girls’ lower academic self-concept can also be extracted from the Ethiopian government’s intention. To minimize the psychological and academic difficulties of females, the Ethiopian government had proposed Article 35 in the country’s constitution (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Citation1995) that mandates affirmative action as a remedy for developmental maltreatment of girls at home and community level (UNICEF, Citation2017/Citation2018/18). This research result is also similar to other research results. Stout and Tamer (Citation2016) and Albert and Dahling (Citation2016) revealed that boys had a more positive academic self-concept than their counterparts. They think confidently, realistically, and effectively. According to Olando et al. (Citation2014), males develop a higher level of competence than females in their developmental stages so males’ academic self-concept is usually found higher than their counterparts. However, a study conducted by Nabi et al. (Citation2017) on the total sample of 180 indicated that the coefficients for the academic self-concept variables were not statistically significant in gender variables.

7.2. Belief in counseling service effectiveness, academic self-concept, and academic help-seeking behavior

This study also revealed that all variables correlate with one another. Academic help-seeking behavior is significantly correlated with belief in counseling service effectiveness. The beliefs in the counseling service effectiveness is significantly correlated with academic self-concept. Similarly, academic self-concept is significantly correlated with academic help-seeking behavior. The findings of this study in academic self-concept and help-seeking behavior indicated that the higher the self-concept is associated with higher value in help-seeking behavior or vice versa. This result is contrary to the theoretical explanation that feelings of inadequacy by individuals’ natural tendency to engage in social comparison are often associated with feelings of inferiority, low self-esteem, and embarrassment. Research in Kenya has also documented that self-concept is related to academic achievement (Ondeche, 2005, and Otelo, 2005; as cited in Olando et al., Citation2014).

The study showed that students with higher academic concept scores have positive beliefs in counseling service effectiveness, and they tend to manifest help-seeking behavior. This result implies that the variance of one variable is directly related to the variation of value in another variable. In specific terms, when increment of value of academic self-concept is directly related to increment of either help-seeking behavior, there would also increment of beliefs in the counseling service effectiveness or vice versa. When students have good knowledge of their cognitive abilities and motivational skills, they know at what junction of difficulties they need help to fill their weaknesses (Paris & Newman, Citation1990). More specifically, the academic help-seeking behavior process begins with metacognition that happens when students identify academic difficulties and become aware that they need help. They then become motivated to seek support and initiate a behavioral response to seek support from someone else (Ryan & Pintrich, Citation1997). This can further be explained by “the 3D process’s aspect of ‘within-discipline notion of Vuong et al. (Citation2022:2)’”. When students’ academic self-concept is high, they tend to seek expert support including counselors and teachers around them. Expertized insights that students get from teachers and counselors (within-disciplines) help them to have a greater understanding about their academic and social problems. Students’ problems can be solved if it is led by “discipline”, “innovative”, and expert knowledge of getting solutions for academic and social problems. Students’ belief in counseling service effectiveness can, therefore, be influenced by the degree of expertise and trustful support they seek. This research result is also similar to the notion of educational discipline. For example, educational psychology research has identified many aspects of successful retention of students inside the educational system when students’ help-seeking behavior is higher on building their cognitive and motivational skills (Drake, Citation2011; Wiseman & Messitt, Citation2010) to improve academic success. As to these researchers, students' help-seeking behavior is associated with their academic self-concept.

8. Limitation of the study

If the data collection was done during the Covid-19 pandemic, this study would have addressed the issue of academic help-seeking behavior of college students and associated variables in the study. It would have a more relevant influence on professional audiences. However, the Covid-19 pandemic and civil war concurrently became prevalent in the study area (Sekota, Ethiopia). Hence, the conclusion and implications forwarded hereunder are based on consideration of the limitation of the study.

9. Conclusion and recommendations

From this study, it can be concluded that academic self-concept and belief in the counseling service effectiveness predicted college students’ academic help-seeking behavior. The finding of this study also indicated that female students have a lower academic self-concept than males. The result implied that providing more help and effective advising to female students shall be an area of emphasis. Based on his research on the impact of science and technology, Vuong (Citation2018) recommended that an effort to support college students to learn science is helping one’s country to open up the gate to sustainable development. This would happen true in Ethiopia when college staffs and leaders (out-disciplines) collaboratively pay attention to college students’ positive mental health. Positive mental health can be achieved through improving positive academic self-concept, belief in counseling service effectiveness and help-seeking behavior. Generally, para counselors and counselors (within-disciplines) shall design expertise strategies to enhance college students’ academic self-concept, belief in counseling service effectiveness that in sum contribute to improved help-seeking behavior and better academic performance in colleges. College officials and NGOs shall finance the efforts that promote students’ mental health and better performance in learning science.

Declaration

I am submitting my manuscript for publication in your journal for I really appreciate reputability of your journal. I am looking forward to getting my paper published in your journal. The manuscript is entitled “Belief in Counselling Effectiveness, Academic Self-concept as Correlates of Academic Help seeking behavior among College Students.” I declare that the manuscript has not been published elsewhere and that it has not been submitted simultaneously for publication as well. I really appreciate your swift feedback for improvement if any.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to thank Bahir Dar University and Department of Psychology, which munificently supported this research work and allowed me to take a study leave during which I was able to make considerable progress with the writing. I am also thankful to my colleagues who support me in editing the questionnaire and collecting data.

Disclosure statement

The author declares that the article review was done in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albert, M., & Dahling, J. (2016). Learning goal orientation and locus of control interaction to predict academic self-concept and academic performance in college students. Journal of Personality Psychology, 97, 245–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.074

- Al-darmaki, F. R. (2011). Needs and attitudes toward seeking professional help and preferred sources of help among Emirati college students. Journal for International Counselor Education, 3, 39–57.

- Anouka, E., Franz, W., Fetenu, B., Lenesil, A., & Mahlet, M. (2015). Female faculty and leadership: Affirmative action and gender equality in 13 universities in Ethiopia. Education Journal, 1(1), 1–16.

- Atkinson, D. R., Lowe, S., & Matthews, L. (1995). Asian-American acculturation, gender, and willingness to seek counseling. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 23(3), 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.1995.tb00268.x

- Barongo, S., & Nyamwange, C. (2013). Contribution of self-concept in guidance and counseling among students. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(13), 7–13.

- Baron, A. S., Schmader, T., Cvencek, D., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2014). The gendered self-concept: How implicit gender stereotypes and attitudes shape self-definition. In P. J. Leman & H. R. Tenenbaum (Eds.), Current issues in developmental psychology. Journal of Gender and development (pp. 109–113).

- Bastian, J., Steer, L., Berry, C., & Lichtman, L. (2013). Accelerating progress to 2015: Ethiopia. The Good Planet Foundation. Unpublished.

- Bei, J., Tan, Y., & Yates, S. M. (2007). A Rasch analysis of the Academic Self-Concept Questionnaire(ASQ). International Education Journal, 8(2), 470–484.

- Benenson, J. F., & Koulnazaian, M. (2008). Sex differences in help-seeking appear in childhoon. British Jorunal of Developmental Psychology, 26, 163–169.

- Bloom, D. E., Canning, K., & Chan, D. (2006). Higher education and economic growth in Africa. International Journal of African Higher Education, 1(1), 24–57.

- Corey, C. (2005). Theory and practice of counseling & psychotherapy (7th ed.). Thomson Learning.

- Drake, J. K. (2011). The role of academic advising in student retention and persistence. About Campus, 16(3), 8–12.

- Elhai, J. D., Schweinle, W., & Anderson, S. M. (2008). Reliability and validity of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale-short form. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.020

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. (1995). Constitution of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa.

- Fittrer, P. (2016). Academic help-seeking constructs and group differences: an examination of first-year university students. Unpublished Dissertation. University of Nevada.

- Gilbert, P.(2007). Psychotherapy and counnseling for depression. 3rd ed. Great Britain: Cromwell Press. PLTD.

- Goldman, D. A., & Penner, M. A. (2016). Exploring international gender differences in Mathematics self-concept. International Journal of Adolescent and Youth, 21(4), 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2013.847850

- Greenidge, W. (2007). Attitudes towards seeking professional counseling: the role of outcome expectations and emotional openness in English-speaking. Unpublished Thesis, 1–71.

- Guay, F., Marsh, H., & Boivin, M. (2003). Academic self-concept and academic achievement: Developmental perspectives on their causal ordering. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.124

- Haile, V., Szendrő, K., & Szente, V. (2020). Recent issues in sociological research. Economics & Sociology, 13(2), 136–150. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2020/13-2/10

- Kabir, M. S. (2018). Essentials of counseling: Counseling approaches. Abosar Prokashana Sangstha. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325844296_counseling_approaches

- Kanga, B. M. (2017). Effectiveness of guidance and counseling services in enhancing students’ adjustment to the school academic environment in public boarding secondary schools in Kenya. International Journal of Innovation and Education Research, 5(7), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.31686/ijier.vol5.iss7.763

- Koc, S. (2016). An investigation of graduate students’ help-seeking experiences, preferences, and attitudes in online learning. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 5(3), 27–38.

- Laxson, K. D. (2014). Who asks for help? Help-seeking attitudes among liberal art students. Social Sciences Capstone Projects.

- Makara, K. A., & Karabenick, S. A. (2013). Characterizing sources of academic help in the age of expanding educational technology: A new conceptual framework. In S. A. Karabenick & M. Puustinen (Eds.), Advances in help-seeking research and applications: The role of emerging technologies. Information Age Publishing.

- Marrs, H., Sigler, E. A., & Brammer, D. R. (2012). Gender, masculinity, femininity, and help-seeking in college. Masculines & Social Change. https://doi.org/10.17583/msc.2012.392

- Masuda, A., Suzumura, K., Beauchamp, K. L., Howells, G. N., & Clay, C. (2005). The United States and Japanese college students’ attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. International Journal of Psychology, 40(5), 303–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590444000339

- Matthews, S. J., Marulis, M. L., & Williford, P. A. (2014). Gender processes in school functioning and the mediating role of cognitive self-regulation. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35(3), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.02.003

- McGrew, K. (2018). Beyond IQ : A Model of Academic Competence & Motivation (MACM) Kevin. 3–5.

- MoE and USAID. (2008). Review of the Ethiopian education training policy and its Implementation. USAID-AED/EQUIP II Pro. Addis Ababa.

- Moloney, L. (2016). Defining and delivering effective counseling and psychotherapy. Family Information Exchange, CFCA PAPER NO, 38.

- Musika, F., & Bukaliya, R. (2015a). The effectiveness of counseling on students ‘learning motivation in open and distance education. International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies, 2(7), 85–99.

- Musika, F., & Bukaliya, R. (2015b). The effectiveness of counseling on students learning motivation in open and distance education. International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies, 2(7), 85–99.

- Nabi, R., Karimi, D., Muthuri, R. N. D. K, & Arasa, J. N. (2017). Gender differences in self-concept among a sample of students of the United States International University in Africa.

- Newman, R. S. (2000). Social influences on the development of children’s adaptive help-seeking: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Developmental Review, 20(3), 350–404. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.1999.0502

- Ng, M. (2014). Self-efficacy beliefs and academic help-seeking behavior of Chinese students. Journal of Educational Sciences and Psychology, 5(1), 17–31.

- Nguyen, M. H. (2021). Mind sponge culture: The culture of progress. In Centre for interdisciplinary social research. Phenikaa University.

- Njoka, J. N. (2014). Guidance and counseling: Theories and approaches to effective students’ support in technical education in Kenya. 7(2074), 1–10.

- Olando, K., Odera, P., & Odera, P. (2014). Effectiveness of guidance and counseling services on adolescent self-concept. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 4(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v4i4.6498

- Onyango, P. A., & Aloka, P. J. (2018). Effectiveness of guidance and counseling in the management of student behavior in public secondary schools in Kenya. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 8(1), 6–11.

- Pankhurst, A., Woldehanna, T., Araya, M., Tafere, Y., Rossiter, J., Tiumelissan, A., & Berhanu, K. (2018). Young lives Ethiopia: Lessons from longitudinal research with children of the millennium. In Country Report. Young Lives.

- Paris, S. G., & Newman, R. S. (1990). Developmental aspects of self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology, 25(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2501_7

- Reese, R. J., Conoley, C. W., & Brossart, D. F. (2002). Effectiveness of telephone counseling : A Field-based investigation. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 49(2), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0167.49.2.233

- RISE.(2018). RISE in Ethiopia. https://www.riseprogramme.org/countries/ethiopia/rise-ethiopia

- Ryan, A. M., & Pintrich, P. R. (1997). “Should I ask for help?” The role of motivation and attitudes in adolescents’ help seeking in Math class. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(2), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.2.329

- Schunk, D. H. (2012). Learning theories : An educational perspective (6th ed.).

- Schunk, D., & Ertmer, P. (2000). Self-regulation and academic learning: Self-efficacy enhancing interventions. In M. Boekaerts, P. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 631–649). Academic Press.

- Stout, G., & Tamer, B. (2016). The grade cohort workshop: Evaluating an intervention to retain women, graduate students. Journal of Frontier Psychology, 7, 1–16.

- Thompson, B. R., Cothran, T., & McCall, D. (2012). Gender and age effects interact in preschoolers’ help-seeking: Evidence for differential responses to changes in task difficulty. Journal of Child Language, 39(5), 1107–1120. https://doi.org/10.1017/S030500091100047X

- UNICEF. (2006). The impact of harmful traditional practices on the girl child in Ethiopia. Ethiopian press: Addis Ababa

- UNICEF. (20172018). Strengthening resilience of education in Ethiopia: Multi-year resilience program.

- Vuong, Q. H. (2018). The (ir)rational consideration of the cost of science in transition economies. Nature Human Behavior, 2(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0281-4

- Vuong, Q. H., Le, T. T., La, V. P., Nguyen, H. T., Ho, M. T., Khuc, Q. V., & Nguyenet, M. H. (2022). Covid-19 Vaccines production and societal immunization under the serendipity-mindsponge-3D knowledge management theory and conceptual framework. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01034-6

- Wiseman, C., & Messitt, H. (2010). Identifying components of a successful faculty-advisor program. NACADA Journal, 30(2), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.12930/0271-9517-30.2.35

- World Bank. (2008). Project appraisal document in support of the general education quality improvement program: Report 45149. Addis Ababa.

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics: An introductory analysis. (2nded.). New York: Harper and Row.