Abstract

Delivery of English language programmes to children at younger ages is a remarkable phenomenon around the world. This research adopts a language-in-education framework to examine how kindergartens in China provide English teaching, and to identify what issues have arisen, in the context of the government ban on preschool English. Qualitative data were collected through observations and interviews with school stakeholders in three kindergartens. Two models of preschool English language provision were found. In one model, visiting foreign teachers deliver one or two lessons per week; in the other, the home-room teachers deliver an English lesson every day. In both models, English is an independent strand which is available to all enrolled children and full of play-based activities and games. The data also reveal issues of concern, in the current policy context, regarding the quality of English teaching and potential social inequalities in terms of access to English learning. The study recommends that the government reconsiders the rationale of the ban and its effects on preschool English provision, and that future research takes a more holistic perspective in studying the quality of early English language education and the implementation of language-in-education planning, particularly in the ‘low-exposure” context.

Summary: This research is part of the author’s PhD study exploring how preschool English language education planning is played out at the local education authority level and the kindergarten level in China, in light of top-down reforms to remove English and other primary-level subjects from kindergartens. The major finding of the PhD study is that the interplay between local education authorities and kindergartens, and between government intervention and market mechanisms, has produced a situation where private kindergartens are still offering English classes while public kindergartens have stopped doing so. The present study compares and analyses English language provision and emerging issues in three private kindergartens. The findings point to the need for more attention to policy-making regarding early English language education and the “low-exposure” learning context.

1. Introduction

The last few decades have witnessed the spread of English as a lingua franca on a global scale. The latest report shows that by April 2022, there were around 1.5 billion people in the world who spoke English natively or non-natively (Statista Research Department, Citation2022). Zein (Citation2021) examined foreign language policies in 84 countries and found that all of them have officially lowered the starting age for learning foreign languages (primarily English) from secondary to primary level. Some countries, such as Cyprus and Poland, have introduced English even earlier as part of preschool education (European Commission, Citation2017). Growth in English language education for young children has become a remarkable phenomenon around the world (Butler, Citation2015; Zein, Citation2021).

Consistent with the global trend, in 2001 China lowered the starting level for learning English from the first year of secondary school (age 12) to the third year of primary school (age eight; Ministry of Education, Citation2001). This initiative led to a boom in English programmes for both primary and preschool-level students (Chen et al., Citation2022; G. Hu & McKay, Citation2012). Some local governments, for example, in Beijing, have responded to the phenomenon by explicitly encouraging English language teaching in kindergartens (Yu & Ruan, Citation2012), but the national government did not communicate authoritatively on the issue until the MOE issued two policies in 2011 and 2018 to curb “schoolification”, namely the provision of primary-oriented education in kindergartens. These policies prohibited the teaching of all primary-level subjects, including English, Pinyin and Mathematics, in kindergartens of all types (Ministry of Education, Citation2011, Citation2018). In practice, this study and others (e,g., Chen et al., Citation2022; Liang et al., Citation2020) have found that some kindergartens persist in providing English language education, in response to the continuing local demand for lessons. However, there is a lack of detailed empirical data on the nature of kindergartens’ English language provision in the current regulatory context. This study aims to fill this gap by collecting and analysing qualitative data from three private kindergartens in Hefei, China, and answering two main questions: 1) how do these kindergartens provide English language education? 2) what issues have they encountered?

2. Literature review

2.1. Early English language education

Broadly, early English language education (EELE) refers to children learning English as a second language in either an English speaking or non-English speaking context at preschool or primary (elementary) school level (Zein, Citation2021). In this paper, the discussion on EELE mainly focuses on English provision as a foreign language in the preschool context.

In the field of second language education, it is commonly argued that an early start takes advantage of children’s biological developmental patterns of language learning (Butler, Citation2015; Zein, Citation2021). In the mid-twentieth century, Penfield and Roberts (Citation1959) examined different speech recovery outcomes among children and adults who had neurological injury or disease, and concluded that “for the purpose of learning languages, the human brain becomes progressively stiff and rigid after the age of nine” (p. 236). This work marked the advent of the “critical period hypothesis” (CPH). The core idea of the CPH is that if children do not get adequate language exposure during the early years, they will not achieve native-like language proficiency. The CPH was subsequently developed by Lenneberg (Citation1967) and bolstered by the work of many other researchers (Abrahamsson, Citation2012; Dollmann et al., Citation2020; Johnson & Newport, Citation1989; Patkowski, Citation1980). However, many controversial debates emerged on the subject concerning issues such as the age span of the critical period and the specific linguistic competencies that are affected (Granena & Long, Citation2013; Long, Citation1990; Ruben, Citation1997). More fundamental challenges to the CPH have arisen in the realm of classroom-based foreign language instruction. There is a body of literature showing that there is no direct correlation between an earlier start and more successful or rapid second language development (Baumert et al., Citation2020; Pfenninger & Singleton, Citation2017). Therefore, whether there is a critical period for foreign language learning is doubtful. However, what has taken shape out of the wider debate on the contested CPH is a popular belief in the efficacy of early language acquisition—as captured in the maxim “the earlier the better” (Butler, Citation2015; Chen et al., Citation2022; Tinsley & Comfort, Citation2012; Zein, Citation2021). This belief is also linked to the pragmatic value ascribed to the early learning of second languages, especially English. At the state level, promoting a young start in foreign languages is seen as an effective strategy in pursuit of national economic growth and global competitiveness (Butler, Citation2015; Zein, Citation2021). At the personal level, it is widely assumed that an early start gives children a boost in education, careers and life generally (Butler, Citation2015; Chen et al., Citation2022). Driven by these top-down and bottom-up forces, many types of EELE programmes have been initiated around the world.

In the foreign-language learning context, a major question for EELE is how to create a conducive learning environment (Andúgar & Cortina-Pérez, Citation2018; Mourão, Citation2018; Schwartz, Citation2022). The European Commission (Citation2011) has stated that “working in pre-primary school settings through the target language can help children reach similar or at least comparable competencies in the first language/mother tongue and in the target language” (p. 14). One well-known approach to the question of learning environment is the English immersion programme, which seeks to optimise children’s target language exposure and to foster their bilingualism and biliteracy. In terms of language exposure time, immersion can be total or partial. In total immersion programmes, children are immersed in the English language for at least 90% of total curriculum time, while partial immersion involves English as the learning medium at least 50% of the time (Johnstone, Citation2018). In both cases, teachers must master not just English language skills but knowledge of other curriculum subjects too, because English is the medium of instruction across the children’s daily classes and routines, and not simply the object of instruction (Johnstone, Citation2018). A second approach is content- and language-integrated learning (CLIL) which has similarities with the immersion framework, but some CLIL formats provide much less language exposure time than typical immersion programmes (Mair, Citation2022; Mård-Miettinen et al., Citation2018). For example, in a CLIL programme delivered in two kindergartens in Italy, English teachers implemented CLIL for only half an hour per day (Mair, Citation2018).

Unlike immersion and CLIL programmes where English is the medium of instruction in other subjects, the “low-exposure” model involves delivery of English in standalone lessons with a very restricted amount of input (about one hour per week; Mourão, Citation2018). The limited instruction time has prompted some authors to raise concerns that children do not get sufficient and appropriate input (Lambelet & Berthele, Citation2015), but others argue that if teachers deliver the lessons effectively with songs, stories, poems and other activities, it would still benefit children by increasing their linguistic and cultural awareness (Johnstone, Citation2018). Across the different EELE approaches, there is considerable variation in teaching time and delivery formats. Immersion programmes, CLIL and the low-exposure model generally correspond with “substantial”, “significant” and “modest” instruction time, respectively (Johnstone, Citation2018). In terms of how English is positioned in the curriculum, EELE can be subdivided into schemes where English is an independent lesson and schemes where it is an instructional language in other aspect(s) of the curriculum. The variety of formats in EELE programmes indicates that the starting age is not the only prominent issue in implementation; how to structure the English provision is also a major consideration.

2.2. Language-in-education planning

Language-in-education planning (LEP) is part of language planning and concerns language learning and language users in education settings (Kaplan & Baldauf, Citation1997; Qi, Citation2021). It encompasses strategic efforts by governments at the macro level to steer language use and study in society, as well as the actions taken by organisations and individuals at the micro level, which tend to be informal and unplanned (Payne, Citation2017; Qi, Citation2021). Kaplan and Baldauf (Citation1997, Citation2005) proposed that the implementation of LEP has the following key aspects:

Access policy which deals with the starting age of language learners;

Curriculum policy which primarily concerns the objectives of language instruction, its educational content and the amount of teaching time;

Personnel policy which pertains to language teacher workforce including where teachers come from and how they are recruited, trained and developed;

Materials and methodology policy which addresses the materials and teaching methods used to accomplish certain teaching and learning goals;

Resourcing policy which deals with the funding for language programmes;

Community policy which relates to community attitudes towards language teaching and their impact on language provision and practice; and

Evaluation policy which refers to the assessments employed to evaluate students’ language development.

The LEP framework represents a holistic perspective on language education provision. Adopting the LEP framework, Butler (Citation2015) examined primary English language education in Asian countries, and Zein and Coady (Citation2021) explored historical and contemporary policy and practice for early-years foreign language education around the world. The literature indicates that behind the growth in EELE there are tensions between macro policy and micro practice, as well as challenging issues such as a shortage of qualified, well-trained English teachers, inadequate teaching resources, and the absence of well-designed curricula (Butler, Citation2015; Zein & Coady, Citation2021). These issues focus attention on how EELE programmes operate in kindergartens rather than on the text of national policy. An effective language programme relies not only on the work of English teachers, but also on the collaboration of a range of individuals and multiple strategies to build a conducive environment for teaching and learning.

In all, an LEP lens on EELE provides a useful theoretical and conceptual orientation for exploring and comparing different EELE programmes. It also highlights the importance of empirical data on what actually happens in these programmes in the micro-level context. Much of the research on EELE as a foreign language focuses on the primary level, while the preschool domain is still rather under-researched (Lugossy, Citation2018; Portiková, Citation2015; Prošić-Santovac & Savić, Citation2022), especially in China under the ban. Two recent studies in China (Liang et al., Citation2020; Zheng & Mei, Citation2021) have examined the change of government policy on preschool English language education and the tensions arising between macro policies and micro practices, but these studies did not provide empirical data on how kindergartens structured their English provision or on what issues they encountered in the context of the ban. The present study does draw on empirical evidence in Chinese kindergartens and grapples with the tension between this regulatory context where preschool English is banned, and the global trend to teach English as a foreign language to children at a very young age. It is hoped that the findings will bring insights for models of EELE as well as for understanding the complexities of preschool education in China.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research design

A qualitative multiple-case study was employed to gain in-depth and holistic understanding of English education provision in three Chinese kindergartens and the participants’ attitudes towards the researched phenomenon (Bryman, Citation2012; Cohen et al., Citation2018). In this research, one kindergarten represents one case. This multiple case study design was chosen because it allows researchers to investigate what is happening in particular situations and settings and to explore similarities and differences across cases, thus potentially yielding rich and robust evidence of the studied phenomenon (Bryman, Citation2012; Yin, Citation2018). The overall design of the research and the procedures for data collection were discussed with and approved by participants.

3.2. Research context and site

Preschool education in China mainly refers to full-time programmes in kindergartens serving children from three to six years of age (Liang et al., Citation2020). It is not a compulsory stage of education but its gross enrolment rate has recently reached 85.2% in 2020 (Ministry of Education, Citation2021). There are two main types of kindergartens: public kindergartens which are administered and financed by state bodies, and private kindergartens which are run and funded by non-state organs and non-state-owned enterprises (Liang et al., Citation2020). By 2020, there were 291,700 kindergartens in China, of which 168,000 (57.6%) were private (Ministry of Education, Citation2021).

This study is part of the author’s wider PhD investigations involving fieldwork conducted in Hefei, a Mandarin-speaking city located in mid-eastern China. The doctoral study was approved by the University of Sheffield’s Research Ethics Committee (reference number 022473). The fieldwork took place from October 2018 to May 2019 and involved five kindergartens (two public and three private) and two local education officials. Purposive and convenience sampling was used to identify and approach the settings. In the selection process, preference was given to kindergartens that provided or used to provide English classes. A major finding in the wider PhD thesis was that the interplay between government and the market, and between the local education authority and kindergartens, has led to a situation where some private kindergartens still deliver English classes, notwithstanding the official ban, while public kindergartens do not. For present purposes, this paper reports and discusses only the data collected from the three participating private kindergartens. These are profiled briefly below.

Kindergarten C has been running for about 20 years and currently has six classes with 20 to 30 students per class. Kindergarten D, which was established not long before the fieldwork took place in 2017, has fewer than 100 students distributed over five classes. Kindergarten E is a chain kindergarten within a renowned cooperative organisation for early childhood bilingual education and has existed for about 10 years. Class sizes and student numbers are similar to Kindergarten C. All three kindergartens have lower-level classes for children aged three to four, middle-level classes for children aged four to five, and upper-level classes for children aged five to six. All three settings are located in urban areas of Hefei.

3.3. Participants and methods

The first data collection method employed in this research was in-situ observation. This method allows researchers to see directly what is going on in the researched environment, to notice details that may not be accessible by other methods, and to obtain additional information that participants may be unwilling to speak about or may not be aware of (Cohen et al., Citation2018; Morgan et al., Citation2017). The observations in this study included observations of the school setting as a whole and class observations. In the whole-school observations, the researcher looked for the use of English words or phrases in the kindergarten’s indoor and outdoor environment, inspected teaching plans mounted on the walls outside each classroom, and attended staff meetings (where permitted) as a non-participant observer. For the classroom observations, one upper-level class of 15 to 25 children (age five to six years) was selected in each kindergarten. All children were Chinese-born and speak Mandarin as their native language. In the selected classes, the observations focused on English use within and outside of designated English lessons, the methods and materials used for teaching English, and the language used as the medium of instruction. The author was a non-participant observer of the classes in order to reduce any impact her presence might have on the class dynamics. She sat at the very back of the room and did not contribute verbally or otherwise in any of the English language activities (Cohen et al., Citation2018; Matthews & Ross, Citation2010). With participants’ consent, photographs were taken during the observations but all faces in the resulting pictures were digitally pixellated.

Along with the observations, one-to-one interviews were conducted with kindergarten headteachers, English teachers and parents. The headteachers of Kindergartens D and E were female and Kindergarten C’s was male. Each had over 10 years’ teaching experience and their age range was 35 to 45 years. The English teachers and parents who participated in the interviews were linked to the observed classes. In total, 17 adult participants from three kindergartens took part in interviews. The breakdown for each kindergarten is shown in Table . The Kindergarten E English teacher was female and Chinese but the three other teachers were male and from other countries. In terms of age, the two Kindergarten D English teachers were in their twenties and the other two teachers were in their thirties. Ten parents participated in interviews. They had a range of occupations, all were in the 30 to 40 age bracket, and only one of them was male.

Table 1. Numbers and roles of interviewed participants

All the interviews probed the participants’ perceptions, attitudes and expectations of preschool English language education. In the case of headteachers and English teachers, the interviews also included questions on how they delivered English classes and the reasons behind their decisions. All the interviews were planned and conducted in a semi-structured format which provided a robust framework for the entire interview, ensuring that essential topics were covered, but which was also flexible enough to accommodate unexpected emerging lines of enquiry (Bryman, Citation2012; Wellington, Citation2015). Interview durations ranged from half an hour to one hour. The interviews with Chinese participants were conducted in Mandarin; interviews with foreign participants were in English or Mandarin according to each person’s preference. The author took special care to demonstrate openness and respect in all her interactions with the participants. To protect participants’ privacy and reduce the potential for harm, all identifying personal information was removed or anonymised in research records (Bryman, Citation2012; Cohen et al., Citation2018).

The interview recordings were transcribed verbatim in their original language. In the case of the Mandarin transcripts, only the quotes selected for the published outputs were translated into English. Any salient non-verbal signs, such as long pauses and laughs, were also marked in the transcripts to provide contextual information (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Cohen et al., Citation2018). In total, over 200 pages of interview transcripts and observation fieldnotes were uploaded to Nvivo for thematic analysis. Codes and themes were iteratively reviewed and revised in order to yield a logical, non-repetitive and interesting story as told by the data (Braun & Clark, Citation2006; Braun et al., Citation2019). The following section presents the main findings.

4. Findings

Applying Kaplan and Baldauf’s (Citation1997, Citation2005) LEP framework, this findings section focuses on the following areas: English language access, curriculum, English teaching personnel, and teaching methodology and materials. None of the participant kindergartens has systems in place for evaluating children’s language attainment or teachers’ effectiveness. Stakeholder attitudes towards English language education are addressed in each of the subsections.

4.1. Access and curriculum policy

In all three kindergartens, English was offered as a course to all children across different classes and grade levels, with the main rationale being to inspire children’s interest in English rather than to achieve high English proficiency. Children as young as three could begin to learn English in lower-level classes. However, the total amount of English instruction time varied among different kindergartens.

In each setting, children usually arrived at kindergarten at 8:00 a.m. and left for home at about 4:30 p.m. In Kindergarten C, all classes had an English lesson delivered by a foreign teacher once per week on Thursday afternoons. In Kindergarten D, two English lessons per class per week were delivered by a foreign teacher on Tuesday and Thursday mornings. On the designated English teaching days in both kindergartens, English teachers usually delivered lessons to higher-level classes first, then to middle- and lower-level classes. Lesson duration was about 25 to 30 minutes in the higher-level and middle-level classes and 20 to 25 minutes in the lower classes. With a maximum of one hour of weekly instruction, the English teaching model in Kindergartens C and D can be characterised as a “low-exposure” model as described by Mourão (Citation2018).

Kindergarten E created a richer English learning environment than Kindergartens C and D. In the kindergarten’s public area, every sign, notice and decoration was English-Chinese bilingual. English lessons in Kindergarten E were delivered to each class every day by a home-room teacher. In the observed upper-level class, English teaching took place before lunch time and lasted about 20 to 30 minutes. It was reported that this lesson duration was typical but occasionally had to be shortened if the previous activity overran. It was apparent that having daily classes enabled Kindergarten E to plan and deliver the English curriculum with greater continuity and systematic progression than in the other two kindergartens, and this seemed to have benefits for pupils’ learning. In the “review time” at the beginning of each lesson, it was observed that pupils in Kindergarten E were better at recalling what they had learnt in the previous class, compared to pupils in Kindergartens C and D. In those two kindergartens—especially Kindergarten C which offered only one English class per week—teachers had to spend much longer reviewing the previous content.

However, Kindergarten E’s more intensive English programme of daily classes still fell short of the “significant time” threshold in Johnstone’s (Citation2018) model, being less than 15% of total indoor teaching time. More significantly, in all three kindergartens, English was delivered as a standalone lesson which was not linked to the rest of the curriculum in terms of teaching content, nor was English used as the medium of instruction in any other area. Teachers and children rarely used English outside of the English lessons. The daily routines in the three kindergartens were mainly filled by required elements of the national preschool curriculum and the individual kindergarten’s curriculum, while English language does not form a major part. Headteachers explained that it would be too risky in the current policy context to give English classes a core position, and that increasing the time allocation for English would add to the kindergartens’ financial and personnel burden.

Despite the disparities in instruction time and scheduling, no major differences were found between the three kindergartens in terms of English teaching content. At the beginning of each semester, kindergartens routinely supplied a broad teaching plan to English teachers, but in practice the teachers can modify the plan according to their teaching needs and preferences. Lesson content in the three observed classes featured short English-language songs, the words for body parts, items of food, types of animals, festivals and colours, and some basic short sentences such as “How is the weather today?” and “I have XX”. In line with R. Hu and Baumann’s (Citation2014) survey of English language education at different levels in China, the present study also found that the teaching focus at preschool level was on common words, phrases and short sentences, and on speaking and listening. There was little attention to rules of grammar, and no emphasis on reading and writing. The headteachers and English teachers were all concerned that a focus on these latter aspects would negatively affect children’s motivation and willingness to speak English.

4.2. Personnel policy

As mentioned above, Kindergartens C and D each hired one part-time foreign teacher to teach English across all their respective classes. English teacher C came from Australia and was doing a PhD in business. During the month of fieldwork in Kindergarten D, Teacher D1 left the school for sudden personal reasons and then was replaced by Teacher D2. Both teachers took part in this research. Among the three participant foreign teachers, only Teacher D1 was not a native English speaker but he was fluent in English. All the foreign teachers had more than one year’s experience of teaching English and two of them had TEFL (teaching English as a foreign language) qualifications.

Kindergarten E had previously employed a full-time native-English teacher but she went back to her home country one year before the fieldwork period. After she left, the kindergarten attempted to recruit another full-time foreign teacher, but such teachers cannot easily get working visas due to the ban on preschool English language education, so now English classes are delivered by full-time home-room Chinese teachers. Headteacher E reported that all these local teachers of English in Kindergarten E had majored in English in college. The teacher who joined in this research also has an English teaching certificate for secondary school. Table profiles the four participant English teachers.

Table 2. Profiles of English teachers

The range of profiles suggests there is an overall preference for foreign English teachers, especially native foreign English teachers. In the views of the participants, foreign teachers not only have the advantage of speaking English more fluently and authentically than local teachers, they are also better at creating an easy-going and relaxed atmosphere for children to speak in class (see also, Liu, Citation2018; Rao & Yuan, Citation2016). Additionally, the different appearance and cultural backgrounds of foreign teachers are seen as advantageous in sparking children’s curiosity about the English language and diverse cultures. The participants said:

Of course, I prefer foreign teachers. They can create a more natural English-speaking environment for children … I audited one English lesson before. Children were very engaged in class. That foreign teacher has a very close relationship with the children. They directly call the teacher’s name, rather than call them ‘teacher’. (Parent D3)

The previous foreign teacher interacted very well with the children. Children like her very much … In my class, although I also try my best to respect them, to create a friendly atmosphere, there is still a difference [with foreign teachers]. I can feel that. (English teacher E)

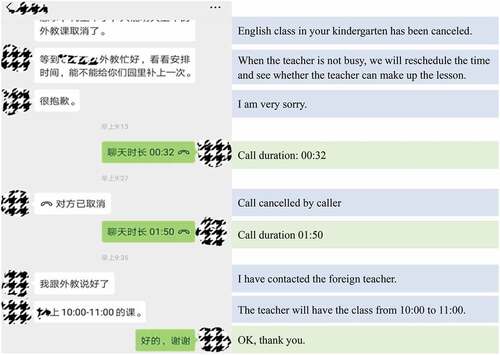

Even though foreign teachers are preferred, there are potential concerns about their professional backgrounds and job stability and the impact of these on the quality of provision. The huge market for foreign English teachers has to some extent resulted in a low qualifications threshold for foreigners to do this job. Table shows that none of the participant foreign teachers has a higher education background in English or early childhood education. Their English language competence may be superior to that of local teachers, but they do not necessarily have better understanding of children’s development, Chinese culture and the Chinese education system, and the fundamental principles of teaching (Liu, Citation2018; Rao & Yuan, Citation2016). All three of the participating foreign teachers were hired through a specialist education employment agency. Headteachers explained that this route ensures the continual provision of foreign personnel for English classes and avoids contracts and communication barriers between kindergartens and English teachers. If a kindergarten is not satisfied with their current English teacher or the teacher leaves the job suddenly, the agency can quickly send out another teacher. However, the use of agencies has also led to some discontinuities in taught content and degraded the relationship between teachers and kindergartens. In the event of issues or problems concerning the English teachers, the kindergarten would typically liaise with the agency rather than communicate with the teachers themselves (see, Figure ).

Figure 1. A Wechat screenshot between Headteacher D and the education agency, with English translation to the right.

Figure shows a scenario where the agency contacted Headteacher D to reschedule English teaching time. The agency’s messages are on the left of the screenshot while Headteacher D’s are on the right. Within the triadic relationship, kindergartens do not provide any in-service training for these foreign English teachers because they regard training as the responsibility of the agency which is in a contractual relationship with the workers. However, the teachers reported that the agencies did not provide any training services, nor did they require particular qualifications for employment. Xu (Citation2021) reports that in 2017 about 400,000 foreigners were working in China doing language teaching jobs, but only about one third of them had a working visa for that purpose. It appears that very few language teachers come to China specifically for teaching, as illustrated by English teacher C’s comments:

This is not a skilled job, actually, you know, we don’t have a good candidate. People come here to enjoy China, travel around China, and some of them get working visas and work in some kindergartens … After one year, they go back and do their work. (English teacher C)

As noted earlier, in Kindergarten D the first English teacher left his position during the fieldwork. All three participating foreign teachers said that they could quit the job at any time. These foreign teachers were not subject to kindergarten staff management systems and obligations, and they did not join in any school activities or attend kindergarten other than for the English classes. This finding supports the assertion by Murphy et al. (Citation2016) that the reliance on external language teachers contributes to the view that English provision in kindergartens is an extra-curricular activity rather than an integral part of children’s daily routines.

Compared with Kindergartens C and D, English teachers in Kindergarten E seemed more involved in school life and had more stable positions. English teacher E has worked in the kindergarten for over eight years. As a member of full-time staff, she was also teaching Chinese classes and participating in all kinds of school activities. However, more involvement means greater workload, and English teacher E reflected that she had little time to properly prepare English classes. Headteacher E was well aware of this situation but did not take any effective measures. In fact, none of the three kindergartens had a member of staff with the requisite level of English skills and experience to provide the professional guidance, training and evaluation needed by the English teachers. The head office of Kindergarten E’s chain of schools used to provide regular training for English teachers, but Teacher E reported that this training scheme had ceased before the fieldwork period because the manager responsible for training resigned. Now, English teachers who wish to improve their teaching skills must rely on their own initiative and on exchanging ideas and experiences with other teachers in the same kindergarten.

4.3. Materials and methodology policy

Of the three kindergartens, Kindergarten C provided the least resources for English teachers and children, consistent with the finding that it allocated the least time to English classes. Previously it used the popular Hongen EnglishFootnote1 scheme textbook, but in light of English teacher C’s rich experience, the headteacher decided to give him more autonomy in what and how to teach, so the teacher prepared all materials himself and brought them from class to class. At the time of the study, Kindergarten D was still using Hongen English, but teachers were also free to use their own materials. All of English teacher D1ʹs lessons were based on electronic Hongen English resources while English teacher D2 brought his own English materials. In Kindergarten E, more teaching resources were provided to teachers. In each classroom, there were plenty of physical English resources, such as books, pictures, cards and objects, for teachers to use in class and for children to read and play with in their free time. The English teachers also had the options of downloading online resources from the school website or preparing some materials themselves.

Using the different types of materials, teachers employed a variety of playful activities, such as games, dancing and singing, to maintain children’s attention and encourage their involvement in the class. Play-based teaching and learning is the core principle of the preschool education curriculum in China (Ministry of Education, Citation2011, Citation2018) and the interviewed participants expressed their support for this approach. Headteacher E said: “our English course cannot be strictly regarded as academic study. We deliver classes through many activities … All classes involve a lot of games.” Other teachers also expressed the same opinion, for example:

In my class, you see maybe videos, maybe songs, and maybe a game, so children feel relaxed, so they feel happy. Because if kids like you, they will learn; if they don’t like you, they won’t learn … So you have to get them to feel comfortable and make them like you. (English teacher D2)

In the views of the participants, the use of games and playful activities to deliver teaching is the main feature which distinguishes contemporary preschool education from traditional approaches that emphasised rote learning and academic attainment. However, it is worth noting that these play-based activities in the study were usually teacher-led rather than child-led. Typically, English teachers would stand or sit in front of the children to direct them in tasks and activities. Without the teacher’s permission, children were not allowed to speak out loud, stand up or do other things. Although there is an argument that structured, teacher-led activities may diminish children’s motivation for engaging in English classes (Lugossy, Citation2018), the English teachers in this study explained that this approach was necessary to ensure that progress was made, given the limited time allocated to English lessons and the wider timetable constraints (see also, Mourão, Citation2014).

English was typically used as the medium of instruction in English lessons, but local English teacher E and foreign teacher D1 (who was very fluent in Mandarin Chinese) sometimes also used Mandarin to help students better understand their instructions. The following episode took place in English teacher D1ʹs class:

Now let’s see colours. XX, what is this colour?

(Student 1 clicked the picture on the TV screen)

Great, give me five!

(After they clapped hands, the second student took a turn)

Where is pink?

(Student D2 shook his head)

Pink. Is this pink?

(Student D2 kept silent)

Pink, 粉色。哪一个是粉色?Where is pink?

(Student D2 picked the correct picture)

… .

Now let’s say these words together. 我们再读一下

This episode shows that the teacher would switch language to Mandarin when students had difficulty in understanding his English words. English teachers D1 and E believed that code-switching is a scaffolding strategy which can improve children’s understanding of English—views which are aligned with recent research (e.g., Daniel et al., Citation2019; Wang, Citation2019). By contrast, the other two foreign teachers spoke only English in their classes, due to their poor command of Mandarin and the desire to create an immersion-like environment. The exceptions were a few command instructions, for example, “please sit down” (请坐下) and “class is over” (下课). The English-only policy may provide children with more English exposure in a short space of time, but whether preschool children’s English levels enable them to follow instructions in English is controversial. In this study, it was observed in class that when teachers spoke English sentences without translation, students appeared confused or distracted. In one class where Christmas-related words were being taught by English teacher C, one student asked another, “do you understand what teacher said?”, to which the reply was “no”. The English teachers were aware of these challenges and they suggested having the classroom assistance of a Chinese teacher who understands English. However, kindergarten headteachers were concerned that such provision would increase extra cost, and instead they would consider providing more teaching resources and updating the teaching technology to support teachers to improve children’s engagement and learning in the class.

5. Discussion

The above analysis provides a picture of preschool English language education in three private kindergartens in Hefei, China. Table summarises the main characteristics of English language provision in these kindergartens.

Table 3. EELE in three kindergartens’ upper-level classes

Table shows that two EELE models were in operation: (i) English classes delivered by visiting foreign teachers one to two times per week; and (ii) English classes delivered by the full-time home-room teacher every day. The second model provides more instruction time and a richer English environment. In both types, the lessons are delivered through teacher-led and play-based methods, and the teaching content is not closely related to the kindergartens’ main curriculum and routines. Children and teachers barely speak English outside English classes. In the kindergartens in this study, no staff other than the English teachers have proficient English language skills, with the corollary that children may be exposed only to one adult voice in English (Johnstone, Citation2018). Based on the study’s findings, it is suggested that the domains of the LEP framework should also include the overall English learning environment and the medium of instruction in the class. An ecological perspective on language learning shows that children’s language acquisition is mediated not only by teaching strategies but also by the children’s physical and social environment (Schwartz, Citation2022; Van Lier, Citation2004). In Kindergarten E’s more immersion-like environment, it was observed that children in their free time occasionally read English books provided by school. They also looked at bilingual signs and sometimes even tried to read out English words. The visual presence of English in their everyday school surroundings increases children’s informal exposure to the language. The teachers’ choice of instructional language is also an important factor. The three kindergartens in this research did not have explicit policies on instructional language, but this is evidently an issue that the teachers must consider given that their reflections (and the fieldwork observations) exposed some communication barriers when teachers only used English in class. Therefore, the findings point to the need for a more flexible strategy regarding medium of instruction in the ELEE context.

Viewing LEP as a multi-level process, the research also provides insights into the interplay between different policy levels. In line with the work of Portiková (Citation2015), this study suggests that without government support and guidance, it is difficult for kindergartens to develop their English language education provision systematically and professionally. First, unsurprisingly, the government ban on preschool English constrains this potential development. Kindergartens can no longer recruit full-time foreign teachers with legal work visas. Teaching time for English has reduced. Before the ban, Kindergarten D had English classes every day and Kindergarten E had a full-time foreign teacher and optional “English interest” lessons in addition to the class teaching. While the ban has not completely stopped these kindergartens providing English education, the way they deliver English classes has changed. English is delivered somewhat covertly, as implied by headteachers in their reflections about cancelling English classes and hiding English materials during school inspection periods.

Moreover, in the absence of government direction on English, kindergartens do not have clear guidance or protocols on how to select English teachers and the best pedagogies for preschool English. The lack of teaching resources, textbooks and in-service training is a common issue across participant kindergartens. None of the settings has a systematic scheme for English, or for recruitment, training and evaluation of English teachers’ performance and professional development. The foreign teachers participating in this study all held student visas, not work visas, and were hired through education employment agencies. They had no direct contractual obligations to the schools and could leave their posts at any time. The findings raise concerns about the qualifications and management of foreign English teachers. Meanwhile, for home-room teachers, the heavy workload involved in teaching English and Chinese as well as fulfilling all their other school duties limited the time and energy available for developing English classes. As a result, neither the kindergarten leaders nor the English teachers have been adequately focused on improving the quality of English teaching, notwithstanding their strong support for EELE in principle. The challenges of these social, school-level and personal factors beg the question of whether these kindergartens choose to offer English classes primarily as a marketing strategy to attract parents eager for their children to start English at a young age (Liang et al., Citation2020).

Cost of access to preschool English education is also an important concern as it potentially leads to greater educational inequalities. To illustrate: Kindergarten E charges the highest tuition fees (10,000 yuan per semester) of the three kindergartens; compared to the other two settings, it has superior provision in terms of teaching time allotted to English, teaching materials, an English-rich environment, and stability of teaching staff. By contrast, Kindergarten C charges the lowest fees (3000 yuan per semester) and offers the least environmental exposure to English. With only a small number of kindergartens under scrutiny here, one cannot draw firm conclusions but there may be a link between quality of English provision and the cost to parents. The English teacher in Kindergarten C was also teaching in another kindergarten with higher fees, and made the following comments during his interview:

At the other school I go to, I also teach English once a week, but I think the students are much better. They can speak anything, a lot of English. I witnessed that after my class, Chinese teachers also teach them some English … And you know, parents also contribute. (English teacher C)

The above extract clearly indicates that English teacher C thought that children in the kindergarten with higher tuition fees achieved higher English attainment. On the issue of parental contribution to children’s language learning, a study by Liu et al. (Citation2020) found that a child’s socio-economic status has larger correlations with school grades in English language and Chinese than with grades in other subjects. The authors speculate that wealthier families can put more money into building rich environments for their children to improve their English and Chinese and to acquire effective learning habits and routines for language-learning. The present study does not aim to evaluate children’s language attainment, but there is some evidence suggesting that children from socio-economically more comfortable families may benefit from more and better English instruction (Butler & Le, Citation2018; Chen et al., Citation2022). This aligns with the assertion by Tinsley and Comfort (Citation2012) that “if there is no national policy for support, ad hoc non-statutory arrangements by the more advantaged social groups will exacerbate social inequality” (p. 78).

6. Conclusions and implications

The present study has analysed and compared EELE in three kindergartens in Hefei, China. A major theme across the participant kindergartens is that their principal aim in EELE is to promote children’s interest in learning English rather than to strive for high attainment in the language. Other commonalities include early-stage access to English for all enrolled children, the preference for foreign English teachers, and a focus on play-based and teacher-led activities. In terms of instruction time and teachers, there was some divergence. Two broad models of EELE became apparent: English instruction by visiting foreign teachers for less than an hour per week; and English instruction by the full-time home-room teacher every day. In neither model does English have a substantial role in the preschool curriculum, and no other content is delivered through the medium of English. Overall, English provision can be characterised as a standalone course, independent of the core curriculum, with instruction time ranging from a half-hour to two hours per week.

The emerging issues concerning quality of provision and potential social inequalities have drawn attention to the gap between the intended goals of policy and its actual effects. The national strategy of prohibiting English language teaching in kindergartens—and curbing schoolification more broadly—was intended to reduce the academic pressure on children and put them on an equal playing field when they enter primary school (Ministry of Education, Citation2011, Citation2018). However, with strong local demand for preschool English provision, the ban has not been complied with in practice and it has exacerbated problems relating to quality of provision and inequality of access. Although none of the participant kindergartens charges extra fees for English classes, this study found that children get more English input in kindergartens with higher tuition fees. Moreover, parents and teachers reflected that many children from middle-class families also tend to learn English in out-of-school English training centres. Therefore, whether the policy behind the ban ultimately fulfils its goal to give children a more equal start in primary school is in doubt. Further scrutiny is warranted.

At the same time, educators and parents must maintain a sensible, reasonable attitude towards EELE. They should be mindful that there is no robust evidence to conclude that English instruction at a younger age confers long-term advantages for children (Butler, Citation2015; G. Hu & McKay, Citation2012). Indeed, if the learning conditions are not appropriate, introducing English to very young children may be problematic (Chen et al., Citation2022; Lugossy, Citation2018). Offering English classes does not necessarily equate to providing qualified English teaching. The qualifications, management and training of English teachers, the provision of English teaching materials, and the development of the preschool English curriculum and pedagogies are issues of concern in this study. The findings point to the need for more research attention to the quality of preschool English provision and low-exposure models of EELE, and to the question of how best to develop the school-based English curriculum without systematic guidance from government. In addition to the provision factors, there are process factors which influence the actual implementation of language programmes. These factors concern how policies transfer across different levels, and how decisions on policies are made in the broader social context. Therefore, an ecological perspective is recommended for researchers seeking a holistic approach to examining the complexities of LEP and language provision.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xuan Li

Xuan Li is an Assistant Researcher in the Institute of Higher Education at Anhui University, China, and holds a PhD from the University of Sheffield, England. Her research interests include language-in-education planning and the internationalisation of education.

Notes

1. Hongen English is one of the top brands in early childhood English education in China.

References

- Abrahamsson, N. (2012). Age of onset and nativelike L2 ultimate attainment of morphosyntactic and phonetic intuition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 34(2), 187–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263112000022

- Andúgar, A., & Cortina-Pérez, B. (2018). EFL teachers’ reflections on their teaching practice in Spanish preschools: A focus on motivation. In M. Schwartz (Ed.), Preschool bilingual education: Agency in interactions between children, teachers, and parents (pp. 219–244). Springer.

- Baumert, J., Fleckenstein, J., Leucht, M., Köller, O., & Möller, J. (2020). The long-term proficiency of early, middle, and late starters learning English as a foreign language at school: A narrative review and empirical study. Language Learning, 70(4), 1091–1135. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12414

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social science (pp. 843–860). Springer.

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th) ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Butler, Y. G. (2015). English language education among young learners in East Asia: A review of current research (2004-2014). Language Teaching, 48(3), 303–342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0261444815000105

- Butler, Y. G., & Le, V. N. (2018). A longitudinal investigation of parental social-economic status (SES) and young students’ learning of English as a foreign language. System, 73, 4–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.07.005

- Chen, S., Zhao, J., de Ruiter, L., Zhou, J., & Huang, J. (2022). A burden or a boost: The impact of early childhood English learning experience on lower elementary English and Chinese achievement. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(4), 1212–1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1749230

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th) ed.). Routledge.

- Daniel, S. M., Jiménez, R. T., Pray, L., & Pacheco, M. B. (2019). Scaffolding to make translanguaging a classroom norm. TESOL Journal, 10(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.361

- Dollmann, J., Kogan, I., & Weißmann, M. (2020). Speaking accent-free in L2 beyond the critical period: The compensatory role of individual abilities and opportunity structures. Applied Linguistics, 41(5), 787–809. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz029

- European Commission. (2011). Language learning at pre-primary school level: making it efficient and sustainable. https://education.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/document-library-docs/early-language-learning-handbook_en.pdf

- European Commission. (2017). Key data on teaching languages at school in Europe – 2017 edition. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Granena, G., & Long, M. H. (2013). Age of onset, length of residence, language aptitude, and ultimate L2 attainment in three linguistic domains. Second Language Research, 29(3), 311–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658312461497

- Hu, R., & Baumann, J. F. (2014). English reading instruction in China: Chinese teachers’ perspectives and comments. The Reading Matrix, 14(1), 26–60. www.readingmatrix.com/articles/april_2014/hu.pdf

- Hu, G., & McKay, S. L. (2012). English language education in East Asia: Some recent developments. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 33(4), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2012.661434

- Johnson, J. S., & Newport, E. L. (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning:The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognitive Psychology, 21(1), 60–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(89)90003-0

- Johnstone, R. (2018). Languages policy and English for young learners in early education. In S. Garton & F. Copland (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of teaching English to young learners (pp. 13–29). Routledge.

- Kaplan, R. B., & Baldauf, R. B., Jr. (1997). Language planning from practice to theory. Multilingual Matters.

- Kaplan, R. B., & Baldauf, R. B., Jr. (2005). Language-in-education policy and planning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 1013–1034). Erlbaum.

- Lambelet, A., & Berthele, R. (2015). Age and foreign language learning in school. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lenneberg, E. H. (1967). Biological foundations of language. John Wiley & Sons.

- Liang, L., Li, H., & Chik, A. (2020). Two countries, one policy: A comparative synthesis of early childhood English language education in China and Australia. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105386

- Liu, X. (2018). A question of culture: Native English speaking teachers teaching young children in China [ Doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina]. Proquest.

- Liu, J., Peng, P., & Luo, L. (2020). The relation between family socioeconomic status and academic achievement in China: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 49–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09494-0

- Long, M. (1990). Maturational constraints on language development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 12(3), 251–285. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100009165

- Lugossy, R. (2018). Whose challenge is it? Learners and teachers of English in Hungarian preschool contexts. In M. Schwartz (Ed.), Preschool bilingual education: Agency in interactions between children, teachers, and parents (pp. 99–131). Springer.

- Mair, O. (2018). Four seasons of CLIL at two Italian pre-schools. In F. Costa, C. Cucchi, O. Mair, & A. Murphy (Eds.), English for young learners from pre-school to lower secondary: A CLIL teacher training project in Italian schools (pp. 21–54). Universitas Studiorum.

- Mair, O. (2022). Content and language integrated learning in European preschools. In M. Schwartz (Ed.), Handbook of early language education (pp. 475–508). Springer.

- Mård-Miettinen, K., Palviainen, Å., & Palojärvi, A. (2018). Dynamics in interaction in bilingual team teaching: Examples from a Finnish preschool classroom. In M. Schwartz (Ed.), Preschool bilingual education: Agency in interactions between children, teachers, and parents (pp. 163–189). Springer.

- Matthews, B., & Ross, L. (2010). Research methods: A practical guide for the social sciences. Pearson.

- Ministry of Education. (2001). Jiaoyubu guanyu jiji tuijin xiaoxue kaishe yingyu kecheng de zhidao yijian [Guidelines for vigorously promoting the teaching of English in primary schools]. http://www.moe.gov.cn/s78/A26/jces_left/moe_714/tnull_665.html

- Ministry of Education. (2011). Jiaoyubu guanyu guifan youeryuan baoyu jiaoyu gongzuo Fangzhi he jiuzheng “xiaoxuehua” xianxiang de tongzhi [MOE notice on regulating kindergarten education and care: Avoiding and rectifying schoolification]. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s3327/201112/t20111228_129266.html

- Ministry of Education. (2018). Jiaoyubu bangongting guanyu kaizhan youeryuan “xiaoxuehua” zhuanxiang zhili gongzuo de tongzhi [MOE notice on removing schoolification from kindergartens]. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s3327/201807/t20180713_342997.html

- Ministry of Education. (2021). 2020 nian quanguo jiaoyu shiye fazhan tongji gongbao [Report on national education development in 2020]. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/sjzl_fztjgb/202108/t20210827_555004.html

- Morgan, S. J., Pullon, S. R., Macdonald, L. M., McKinlay, E. M., & Gray, B. V. (2017). Case study observational research: A framework for conducting case study research where observation data are the focus. Qualitative Health Research, 27(7), 1060–1068. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316649160

- Mourão, S. (2014). Taking play seriously in the pre-primary English classroom. ELT Journal, 68(3), 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccu018

- Mourão, S. (2018). Play and peer interaction in a low-exposure foreign language-learning programme. In M. Schwartz (Ed.), Preschool bilingual education: Agency in interactions between children, teachers, and parents (pp. 313–342). Springer.

- Murphy, V. A., Evangelou, M., Goff, J., & Tracz, R. (2016). European perspectives on early childhood and care in English for speakers of other languages. In V. A. Murphy & M. Evangelou (Eds.), Early childhood education in English for speakers of other languages (pp. 57–74). British Council.

- Patkowski, M. S. (1980). The sensitive period for the acquisition of syntax in a second language. Language Learning, 30(2), 449–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1980.tb00328.x

- Payne, M. (2017). The inclusion of Slovak Roma pupils in secondary school: Contexts of language policy and planning. Current Issues in Language Planning, 18(2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2016.1220281

- Penfield, W., & Roberts, L. (1959). Speech and brain mechanisms. Princeton University Press.

- Pfenninger, S. E., & Singleton, D. (2017). Beyond age effects in instructional L2 learning: Revisiting the age factor. Multilingual Matters.

- Portiková, Z. (2015). Pre-primary second language education in Slovakia and the role of teacher training programmes. In S. Mourão & M. Lourenço (Eds.), Early years second language education: International perspectives on theory and practice (pp. 177–188). Routledge.

- Prošić-Santovac, D., & Savić, V. (2022). English as a Foreign Language in Early Language Education. In M. Schwartz (Ed.), Handbook of Early Language Education (pp. 449–474). Springer.

- Qi, G. Y. (2021). Early Mandarin Chinese learning and language-in-education policy and planning in Oceania. In S. Zein & M. R. Coady (Eds.), Early language learning policy in the 21st Century: An international perspective (pp. 85–107). Springer.

- Rao, Z., & Yuan, H. (2016). Employing native-English-speaking teachers in China: Benefits, problems and solutions. English Today, 32(4), 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078415000590

- Ruben, R. J. (1997). A time frame of critical/sensitive periods of language development. Acta Oto-laryngologica, 117(2), 202–205. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016489709117769

- Schwartz, M. (2022). Early language education as a distinctive research area. In M. Schwartz (Ed.), Handbook of early language education (pp. 1–26). Springer.

- Statista Research Department, (2022, August 5). The most spoken languages worldwide in 2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/266808/the-most-spoken-languages-worldwide/

- Tinsley, T., & Comfort, T. (2012). Lessons from abroad: International review of primary languages. CfBT Education Trust. https://www.educationdevelopmenttrust.com/EducationDevelopmentTrust/files/cc/ccead869-2418-4cad-b04a-d4ae98097448.pdf

- van Lier, L. (2004). The ecology and semiotics of language learning: A sociocultural perspective. Kluwer Academy.

- Wang, D. (2019). Multilingualism and translanguaging in Chinese language classrooms. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wellington, J. (2015). Educational research: Contemporary issues and practical approaches (2nd) ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Xu, X. (2021, August 27). Foreign-based teachers grapple with China’s latest education policy. Pandaily. https://pandaily.com/foreign-based-teachers-grapple-with-chinas-latest-education-policy/

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th) ed.). SAGE.

- Yu, Z., & Ruan, J. (2012). Early childhood English education in China. In J. Ruan & C. B. Leung (Eds.), Perspectives on teaching and learning English literacy in China (pp. 51–66). Springer.

- Zein, S. (2021). Introduction to early language learning policy in the twenty-first century. In S. Zein & M. R. Coady (Eds.), Early language learning policy in the 21st Century: An international perspective (pp. 1–40). Springer.

- Zein, S., & Coady, M. R. (2021). Early language learning policy in the 21st century: An international perspective. Springer.

- Zheng, Y., & Mei, Z. (2021). Two worlds in one city: A sociopolitical perspective on Chinese urban families’ language planning. Current Issues in Language Planning, 22(4), 383–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2020.1751491