Abstract

In the search for solutions to national skill formation challenges, the central and northern Europeans models of good practices in dual vocational education and training (VET) permeated the imaginary of the southern countries. Particularly, the German dual VET system has been predominant in the discourse of policy-makers. This research analyses the role played by the European Union (EU) in the promotion of this model as the reference for the reforming Member States during the policy transfer stage of cross-national attraction. This paper develops a reflexive Thematic Analysis among the fundamental documentation related to VET resulting from the EU Governance Triangle. Its aim is to interpret the EU proposal for the reform of VET, with a focus on the characteristics which shape the way in which the training is developed. This Thematic Analysis reveals that the EU promotes a VET training model based in work-based learning as a pillar, preferably articulated in the form of apprenticeships. This, along with the general principles for the regulation of apprenticeships promoted by the EU, proves the agency role exercised by the EU in the dissemination of dual VET as a model of good practice.

1. Introduction

The signing of the Copenhagen Declaration in 2002 on enhanced European cooperation in vocational education and training (VET) inaugurated a reform cycle which, to a greater or lesser degree, reached all the Member States (MS) of the European Union (EU). However, this cycle impacted in a greater degree among the southern MS .This region was hit hardest by the third and fourth industrial revolutions, as well as the Great Recession of 2008, which changed the landscape of the national productive sectors. From these changes, there was a decline in the employability of low-skilled individuals. This situation led to what is known as a skill mismatch, i.e. a disconnection between the demands of the market and the training that had been received by vocational graduates. Spain has been one of the worst affected, suffering the accentuation of structural problems, with unemployment rates up to 26.02% in 2012 (35% in Andalusia) and youth unemployment rates of 59.8% (66% in Andalusia). The European Union placed the focus of criticism on the VET systems characteristic of this region, as evidenced by the following statement: “others (VET systems), typically in southern Europe, lag behind in terms of participation, quality, outcomes and attractiveness” (European Commission, Citation2012, pp. 5–6).

In response, the different national actors looked abroad for solutions to their national challenges related with VET and skill formation. This started a policy transfer process where the European level played a major role. According to Zaunstöck et al. (Citation2021), in the case of Spain, this influence was particularly significant:

The Copenhagen Declaration, the process leading to it and its aftermath were ultimately relevant for Spanish stakeholders in terms of discussing the intentions and directions of Spanish VET. Spain has not only adopted the wording behind the Copenhagen Declaration but also aligned itself in the same direction: the foundation of its current VET system can be clearly correlated with the Copenhagen principles and pillars. (Zaunstöck et al., Citation2021, p. 15)

In Spain, during this search for solutions to national VET challenges, the central and northern European models of good practices in dual VET permeated the imaginary of policy actors. Particularly, the German dual VET system has been predominant in the discourse of policy-makers, lobbies and experts (Martín-Artiles et al., Citation2019). The aim of this research is to analyse the role played by the EU in the promotion of this model as the reference for the southern reforming MS during the policy transfer stage of cross-national attraction (Phillips & Ochs, Citation2003).

Two of the main distinguishing features of dual VET are its governance model and its training model. In order to analyse the role played by the EU as an agent of dual VET policy transfer (Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2014) at the stage of cross-national attraction (Phillips & Ochs, Citation2003), a previous paper (Martínez-Izquierdo & Torres, Citation2022) addressed the issue of VET governance. This article completes the analysis by focusing on the EU proposals and recommendations related to the VET training model. In this case, the term “training model” encompasses the VET system characteristics which shape the way in which the training is developed.

In accordance, this research is driven by the following questions: What articulation of the VET training model is promoted by the EU? What examples of good practices in respect to the VET training model are sponsored by the EU?

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Work based learning, apprenticeships and dual VET

Work-based learning (WBL) is a broad term with the only requirement being that it takes place during work. The constraints of time or place associated with WBL are very ambiguous. As stated by Grollmann (Citation2018), “work-based learning is too non-specific because it may be associated with a very wide range of constellations (job rotation or mentoring at work) that are unconnected with vocational education and training” (p. 78). However, there are some structures which clearly link both fields (VET and WBL) as show in Figure .

Figure 1. Work-based learning and vocational education as set theory.

At the intersection of VET and WBL, concepts such as apprenticeships, dual VET, alternating training, cooperative education and traineeships can be found. This article focuses on three of them: apprenticeships, dual VET and traineeships (the latter to a lesser and only to avoid any confusion with apprenticeships).

Cedefop (Citation2014) and the Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion (Citation2013) address the definition of the term apprenticeships. Apprenticeships are thus defined as formal training that combine two equally important settings (the educational institution and the workplace), the completion of which leads to an official certified vocational qualification. As stated by the Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion (Citation2013):

They provide systematic, long-term training (usually up to four years) by combining practical work-related training at the workplace (either company- or school-based) with theoretical education in an educational institution or training centre. Based on a predefined training plan, their pedagogical content seeks to help learners acquire over time the full set of knowledge, skills and competences required for a specific occupation. (p. 4)

Apprenticeships are characterised by the fact that the apprentice is given the status of an employee, with a legally binding contract that explicitly covers all aspects of training. The remuneration of apprentices is in line with collective agreements and in certain sectors, the cost is partially compensated by public subsidies. The participation and involvement of a wide range of social actors (chambers, labour union, industry representatives, etc.) in both training and governance of the system is guaranteed.

At this point, it is worth devoting this paragraph to the definition of the concept of traineeships in order to check the differences between traineeships and apprenticeships. Traineeships can be linked to educational programmes or to vocational rehabilitation programmes. The former have the objective of complementing studies by accrediting some practical experience that facilitates the transition to the world of work, sometimes becoming an optional choice. Their duration varies from very short to medium-length periods. In this case, the document that accredits the relationship between the student and the company consists of a school-employer agreement. Its regulation of training aspects is very vague, ignoring aspects such as remuneration, which is mostly non-existent, working conditions or contents.

Apprenticeships and dual VET are closely related and, often, overlapping terms. Dual VET is the term used to define vocational training systems based on the apprenticeship model in certain European countries. In fact, dual VET is often indiscriminately replaced by dual apprenticeships. In view of the traditional ambiguity of the definitions of apprenticeships, the term dual VET or dual apprenticeships was coined. This differentiates the structures known as apprenticeships in other regions, such as the USA, Canada or Australia which have their own characteristics (100% company-based, absence of labour representatives at the decision level of the governance model, age of the apprentices), from the European apprenticeship models associated with the German-speaking world. These European systems of collective skill formation (Busemeyer & Trampusch, Citation2012), classified under the term “dual VET”, are characterised by a training model based on apprenticeships governed by cooperative governance. Starting from a common basis which forms the backbone of dual VET, the detailed characteristics of the systems vary from one country to another in the configuration of certain elements, as for example, training regulations, contracts, frequency of alternation of training in different contexts (Rauner & Smith, Citation2010), curriculum and qualifications (Fuller & Unwin, Citation2011; Pilz & Fürstenau, Citation2019), the orientation and integration of the governance system (Rauner & Wittig, Citation2010), expansion across different productive sectors, support for disadvantaged groups (Bosch & Charest, Citation2008) or auditing and monitoring of its proper functioning (Alemán-Falcón & Calcines-Piñero, Citation2022). However, the existence of differences on specific points does not detract from the existence of a shared basis.

2.2. Educational policy transfer

As stated by Maurer and Gonon (Citation2014) nowadays “it would be surprising if governments and their experts … tried to resolve the challenges of technical and vocational education by developing context-specific solutions from scratch … and therefore (they) look for models and best practices that have worked elsewhere” (p. 16). This search for solutions beyond the limits of the system itself. leads to a policy transfer process, which involves reforms or the articulation of new policies based on models which are already a successful reality in other locations.

Li and Pilz (Citation2021) conclude from their literature review of the discourses about VET policy transfer that “VET transfer research is also an important topic within comparative education science—in particular international educational transfer and its possible forms” (p. 6). This research belongs to what Evans (Citation2009) describes as a policy transfer analysis:

Policy transfer analysis is a theory of policy development that seeks to make sense of a process or set of processes in which knowledge about institutions, policies or delivery systems at one sector or level of governance is used in the development of institutions, policies or delivery systems at another sector or level of governance (pp 244–245).

Steiner-Khamsi (Citation2014) defined two fundamental perspectives within comparative education science: applied normative researchers and analytical researchers. On the one hand, the applied normative researchers advocate comparison as a means of identifying and transferring successful practices from one education system to another. On the other hand, analytical comparative researchers focus their work on the analysis of when, why and how policy borrowing occurs. Their interest lies on assessing the impact of such borrowing and lending on local policies and power constellations. Analytical comparative researchers advance on the understanding of the balance of diffusion power, the factors that strengthen the dissemination of a model as a good practice and their effects in the power position of the different political and educational actors (Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2014). This research follows an analytical perspective and advances the understanding of the transfer process of VET policies among European countries, avoiding making judgements on the appropriateness of the borrowing or lending of any VET policy.

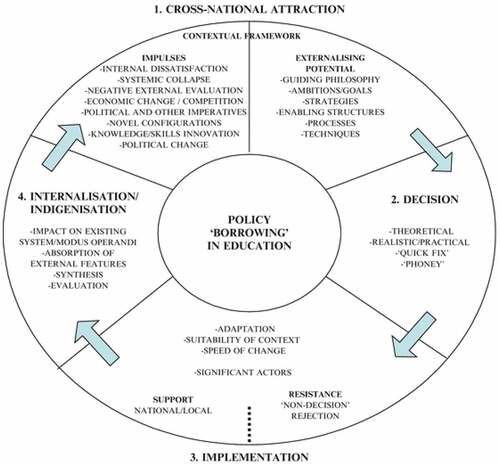

Phillips and Ochs (Citation2003) proposed an analytical framework (Figure ) for researching “the conscious adoption in one context of the policy observed in another” (p. 774). It consists of a circular model comprising the cross-national attraction (1), the decision (2), the implementation (3) and the internalization (4) stages.

Figure 2. Policy Borrowing in Education: Composite Processes.

This article pursues a deeper understanding of the cross-national attraction stage at the dual Vet policy transfer in Europe. Along this stage, the internal impulses and the externalising potential play a fundamental role. The internal impulses are those factors that motivate or drive transfer and create the conditions that make it possible to look for examples or models of success elsewhere (Phillips, Citation2004). They could be a political change, the systematic collapse of the present system, negative external evaluations, the creation of new international alliances, etc (Phillips, Citation2005). Likewise, the externalising potential is constituted by those elements of the foreign system that, theoretically, could be borrowed by the importing country (Ochs & Phillips, Citation2002). These elements, named foci of attraction, are six in total: the guiding philosophy (equal educational opportunities, for example), ambitions or goals (education for all, gender equality), strategies (financing, further training), enabling structures (new school types, general organisational reform), processes (assessment procedures, reporting, certification) and “techniques” (teaching methodologies) (Ochs & Phillips, Citation2002).

In order to develop an accurate analysis of policy transfer processes,, Steiner-Khamsi (Citation2014) underscores the importance of agency in any process of diffusion, reception, lending or borrowing. This approach to agency involves the analysis of the role played by multiple actors, beyond the central state (Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000; Rappleye, Citation2006). Accordingly, transnational organisations, including the EU and its respective agencies, which play a fundamental role in the dissemination of ideas, programmes and institutions (Jakobi, Citation2012), must be put under scrutiny. Their actions, which have a bearing in policy transfer processes, not only include policies and funding, but also diffusion of information and models of good practice in conferences and reports (Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000).

With regard to these dissemination activities at the European level, Europeanisation theories have become a core concept in analysing the way the EU develops its agency role in policy transfer among MS. The term europeanisation is used to describe the impact of the EU on the political life, legislative policies and governance of MS (Ante, Citation2016 Bulmer, Citation2008). In the educational and VET policy area, according to the principle of subsidiarity, the EU plays a supportive role and fosters cooperation between MS. However, this cooperation strengthens the Community’s political impact in the educational area where hierarchical intervention is not possible. To this end, two lines of action have been defined: the dissemination of best practices and the promotion of joint reflection (Novoa, Citation2002). The EU plays its role as an agent of the policy making process by using minimum or non-binding directives or regulations and providing possible solutions to certain problems. These permeate the national debates and, in some cases, they enable a change in the problem perception of the national actors. In such a way, the EU actively favours learning processes and legitimate alternatives (Zaunstöck et al., Citation2021) which modify local actors’ role in the education reform. This entails an EU agency role in any process of policy transfer which takes place between MS.

In the case of VET, in order to exercise influence in national reforms, since the beginning of the Copenhagen process, the EU makes use of what Cort (Citation2009) named as the EU Governance Triangle, among other soft power mechanisms (Dimitrova et al., Citation2016). This triangle is composed of three mechanisms: the Community method, the programme method and the Open Method of Coordination (OMC). The latter is defined as “a clear indicator of a two-level process … which redirects education policy formulation back to the national ministries” (Walkenhorst, Citation2008, p. 581). A previous article (Martínez-Izquierdo & Torres, Citation2022) addressed the issue of the EU proposals related to VET governance. On this occasion, to delve deeper into the role of the EU, this article reviews the fundamental documents related to VET reform resulting from this EU Governance Triangle with a focus on the proposals and recommendations related with the characteristics which should shape the way in which the training is developed. In such a way, this analysis sheds light to the role exercised by the EU as an agent of the dual VET policy transfer among MS.

3. Methods

The reflexive Thematic Analysis (TA) proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2021) was used to address the questions which guide this research (What kind of VET training model is promoted by the European Union? What examples of good practices in respect to the VET training model are sponsored by the European Union?). Along this research, the process has relied on the use of NVIVO’s qualitative data analysis computer software.

Braun and Clarke (Citation2021) define reflexive TA as “a method for developing, analysing and interpreting patterns across a qualitative dataset, which involves systematic processes of data coding to develop themes” (p. 4). The adjective reflexive implies that this TA is suffused with a Big Q approach which “involves both the use of qualitative tools and techniques and qualitative values, norms and assumptions” (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021, p. 287). In addition, it entails emphasising the author´s subjectivity, as well as his awareness and reflective capacity about it. Consequently, a reflexive TA involves an active agency of the researcher in all the processes which are encompassed by the development of themes.

The corpus of this analysis was compiled from an exploration of the European Union repositories (EUR-Lex repository, the Publication Office of the European Union and the Document Library of the European Education Area). Along this exploratory process, the main objective was the preliminary review of the EU texts concerning the enhancement of the VET systems and the Copenhagen process. The criteria for the search were limited to legal acts documents in English published between November 2002 and June 2022 (from the signing of the Copenhagen Declaration until the beginning of this research) containing “vocational education” OR “apprenticeship*” in their title or text. Consecutively, texts which do not deal with the enhancement of VET were excluded. The final documentation corpus (Appendix) of this study is integrated by 35 texts consisting mainly of communications, recommendations and statements from the main European institutions (Council of the European Union, the European Commission and the European Parliament or the European Minister of Vocational Education and Training, etc.).

As described in Braun and Clarke (Citation2021), this reflexive TA was developed in six stages. The first stage, dataset familiarisation, was configured by a preliminary approach to the reference corpus compiled from the European Union repositories. During this stage, the preliminary focuses of interest were detected and the body of documentation was imported to NVivo. Secondly, using a mixed approach (deductive and inductive), the coding process was articulated. Consecutively, a preliminary generation of themes were developed. During this phase, patterns of meaning were sought in order to detect those which could configure an answer to the research questions. Subsequently, the themes were reviewed to give a title and define each of them according to the global analysis. Finally, this paper was elaborated bearing in mind the research questions.

4. Results

This TA generated three themes under the macro-theme of enhancing the relevance of WBL in MS’s VET systems. This enables the following outline of the results:

Promoting WBL as a pillar of VET systems

Fostering dual apprenticeships as best practices for WBL

Promoting general common principles for the regulation of the proposed dual apprenticeships

4.1. Promoting WBL as a pillar of VET systems

The European documentation connects the promotion of WBL to the achievement of a high quality VET system:

[] … as well as promoting world-class vocational education and training (VET) … including through the promotion of work-based learning. (European Parliament, Citation2013, p. 3)

The shaping of the promotion of WBL as a substantial part of VET systems began in 2006, with the invitation to the Helsinki Communiqué signatory countries to bring their VET systems closer to the world of work. All this goes hand in hand with improving the status and attractiveness of VET as an educational pathway.

Young people in VET should acquire skills and competences relevant to labour market requirements, for employability and for lifelong learning. This calls for policies … to better facilitate school-to-work transition, e.g., by combining education and training with work through apprenticeships and work-based learning. (European Ministers for Vocational Education and Traininget al., Citation2006, p. 3)

However, it is from 2010 onwards that the theme of the promotion of WBL increases its weight and frequency within the European texts, coinciding in time with the after Great Recession political concern for the recovery of youth employment, social cohesion and Europe global competitiveness in the race for development and global leadership. This is manifested, in some of the different justifications that motivate such documentation, such as the high rates of youth unemployment, the struggle for social cohesion, precariousness and global competitiveness in the economic and educational area:

Whereas the economic crisis has caused a massive rise in unemployment rates in the EU Member States; whereas young people have been disproportionately affected by this trend; whereas the rate of youth unemployment is rising more sharply in relation to the average unemployment rate; whereas more than 5,5 million young people in the EU under 25 were unemployed in December 2009, equivalent to 21,4 % of all young people. (European Parliament, Citation2010, p. 3)

The major challenge is to ensure the acquisition of key competences by everyone, while developing the excellence and attractiveness at all levels of education and training that will allow Europe to retain a strong global role. (Council of the European Union, Citation2009, p. 2)

Whereas education and training are key factors for successful participation in the labour market, given a situation where more than 5,5 million young Europeans are without work … and many young people are forced to accept precarious jobs, with low salaries and reduced social insurance cover, which affects their health and safety in the workplace. (European Parliament, Citation2011, p. 3)

In a similar vein, there are explicit calls for the reform of MS’s VET systems in pursuit of duality in order to cope with this unfavourable circumstances:

Calls on the Member States, given the reorientation towards a sustainable economy and sustainable growth, to strengthen the institution of vocational education and training since it has the potential to become a means of addressing the social consequences of corporate restructuring for workers, by increasing their employability. (European Parliament, Citation2011, p. 7)

Urges the Member States to implement strong measures to fight youth unemployment and early exclusion from the labour market, in particular through preventive action against early dropout from school or from training or apprenticeship schemes (e.g., by implanting a dual educational system or other equally efficient types of framework). (European Parliament, Citation2014, p. 4)

VET must play a dual role: as a tool to help meet Europe’s immediate and future skills needs; and, in parallel, to reduce the social impact of and facilitate recovery from the crisis. These twin challenges call for urgent reforms. The case for better skills development in Europe is even more urgent in the light of the global race for talent and rapid development of Education and Training (E&T) systems in emerging economies such as China, Brazil or India (European Commission, Citation2010, p. 1)

The EU points as an example of good practice to certain national VET systems where WBL has traditionally been a pillar. These excerpts also show a contrast between this model of success and that of Southern European countries:

Some European countries already have world-class VET systems (Germany, Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands), with built-in mechanisms to adapt to current and future skills needs so training is more demand-driven. They report fewer problems with skills mismatches and show better employment rates for young people, and in these countries VET education is characterised by dual systems which have a high proportion of work-based learning. May others, typically in Southern Europe, lag behind in terms of participation, quality, outcomes and attractiveness. (European Commission, Citation2012, pp. 5–6)

To improve VET quality and performance and that are subsequently explained … MS needs to increase the importance and use of the workplace training dimension. This report has shown that those VET systems with a strong work based training component in a real enterprise setting provide students with a number of skills and competences in addition to pure vocational ones. (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Citation2012, p. 127)

Consequently, from the beginning of the second decade of the century, the EU advocate increasing the relevance of WBL in the VET systems of the different MS:

Work-based learning, such as dual approaches, should be a central pillar of vocational education and training systems across Europe, with the aim of reducing youth unemployment, facilitating the transition from learning to employment and responding to the skill needs of the labour market. (European Commission, Citation2012, p. 7)

Member States should strengthen work-based learning in their vocational education and training systems. (Council of the European Union, Citation2018, p. 4)

Another pattern of meaning emerging from the TA of the European texts is the need to extend this work-based training to a larger number of students, as well as to a wider number of VET stages and programmes:

The labour market relevance of VET, and the employability of VET graduates, should be enhanced through various measures … Work-based learning carried out in partnership with businesses and non-profit organisations should become a feature of all initial VET courses. (European Ministers for Vocational Education and Training et al., Citation2010, p. 10)

Work towards achieving by 2025 the following EU-level objectives which are part of relevant European monitoring frameworks, including in the area of education and training and social and employment policies … 60 % of recent graduates from VET benefit from exposure to work-based learning during their vocational education and training (24). (Council of the European Union, Citation2020, p. 5)

Finally, the last pattern of meaning within this theme is the expansion of WBL across different sectors of the economy. The European institutions propose the creation of certain incentives to help create WBL opportunities in those sectors where this kind of training is still in the minority, and in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs):

In order to create work-based learning opportunities in different sectors of the economy, incentive measures could be provided for employers in line with national context. (Council of the European Union,Citation2020, p. 6)

Concrete actions could, for example, … support SMEs in providing apprenticeship places (including incentives), etc. (European Ministers for Vocational Education and Training et al., Citation2015, p. 8)

4.2. Fostering apprenticeships as best practices for integrating WBL at VET systems

The second major theme produced by this TA is the promotion of apprenticeships as the ideal way of integrating WBL into VET systems. The evolution of this theme runs parallel to the evolution of the presence of WBL in the European texts. Thus, in 2006, both realities were already linked by the European institutions:

This calls for policies to reduce drop-out rates from vocational education and training and to better facilitate school-to-work transition, e.g., by combining education and training with work through apprenticeships and work-based learning. (Council of the European Union & Representatives of the Governments of the Member States, Citation2006, p. 2)

Likewise, since 2010, the presence of the articulation of apprenticeship as a best practice for integrating WBL has experienced the same exponential growth described in the previous section for the promotion of WBL. The EU advocates the development of this type of training modality in the reform of national VET systems:

Participating countries should support the development of apprenticeship-type training and raise awareness of this. (European Ministers for Vocational Education and Training et al., Citation2010, p. 10)

Undertake VET system reforms, in cooperation with social partners and other relevant stakeholders, by introducing an apprenticeship … in order to increase the number, quality and attractiveness of apprenticeships. (European Commission et al., Citation2013, p. 3)

In the same vein, apprenticeships are placed in a superior position compared to other types of WBL:

Calls for training by means of apprenticeships to be assigned priority over any other type of training, e.g., traineeships. (European Parliament, Citation2011, p. 6)

One of the most referenced points in favour of apprenticeships is their effectiveness in the integration of young people into the labour market. This association between apprenticeships and labour integration is reinforced by the European institutions with the inclusion of this training modality within the European recommendations for the strengthening of employment after the crisis produced by Covid-19:

The Council of the European Union expresses its strong commitment to combating youth unemployment and inactivity … whilst noting that high quality apprenticeships are effective instruments to improve sustainable transitions from school to work. (European Commission et al., Citation2013, p. 3)

Member States should introduce or strengthen support schemes for apprenticeships … These schemes should include a strong training component and be subject to monitoring and evaluation, offering a path to stable labour market integration. (European Commission, Citation2021, p. 6)

The EU’s very favourable assessment of apprenticeships is based on the good experiences of certain MS, in particular Germany, Austria and Denmark. According to EU texts, these countries share a long tradition of apprenticeships as an effective transition platform between education and employment:

Calls for more and better apprenticeships; refers to the positive experiences with the dual system within vocational educational and training (VET) in countries such as Germany, Austria and Denmark where the system is seen as an important part of young people’s transition from education to employment. (European Parliament, Citation2010, p. 6)

4.3. Promoting general common principles for the regulation of the proposed dual apprenticeships

Recommendations on the specific characteristics that should shape the structure and functioning of the proposed apprenticeships model permeate the European texts. This theme stands out as one of the concerns of the European institutions in respect to the training model. In this way, the EU not only fosters apprenticeships as best practices for integrating WBL at VET systems, as it has been remarked along the first two themes, but also promotes general common principles for their regulation and structure.

Along the first pattern of meaning, the EU calls for the creation of a regulatory framework, adapted to each context and precious regulations, where the roles of all the actors involved should be exhaustively defined:

Work based learning and notably apprenticeships and other dual models help facilitate transition from learning to work. These require a clear regulatory framework, defined roles for the different players. (European Commission, Citation2012, p. 6)

Creating a clear regulatory framework taking into account existing regulations, industrial relations and education practices. (European Ministers for Vocational Education and Training et al., Citation2015, p. 8)

More specifically, the EU promotes the establishment of a common set of guidelines for the regulation of apprenticeships among the different MS. For the European institutions, the conditions and quality of apprenticeships must be ensured through the creation of a quality framework at the level of each MS which should be based on the European Quality Assurance Reference Framework for VET (EQAVET) and more specifically, on the European Framework for Quality and Effective Apprenticeships (EFQEA):

Participating countries should - by the end of 2015 - establish at national level a common quality assurance framework for VET providers, which also applies to associated workplace learning and which is compatible with the EQAVET. (European Ministers for Vocational Education and Training et al., Citation2010, p. 9)

Continue to implement the EQAVET with a view to developing a quality assurance culture within and between Member States, including at the level of VET providers, in particular by making efforts to establish at national level by the end of 2015 – in accordance with the Bruges Communiqué – a common quality assurance framework for VET providers, covering VET school-based learning and work based learning, as appropriate to the national context. (Council of the European Union, Citation2014, p. 2)

This quality framework for dual apprenticeships, according to the European texts, must protect the apprentice, by guaranteeing his training and by avoiding employer abuses, including the misuse of the apprentice’s will to turn him into a cheap or free labour force:

Calls for young people to be protected from those employers – in the public and private sector – who, through work experience, apprenticeship … are able to cover their essential and basic needs at little or no cost, exploiting the willingness of young people to learn without any future prospect of becoming fully established as part of their workforce. (European Parliament, Citation2010, p. 7)

Calls on the Member States to ensure a quality framework that does not allow … apprenticeships to be used as cheap or free labour; points out that an understanding of core health and safety standards and rights in the workplace is also important in developing quality employment and preventing exploitation. (European Parliament, Citation2017, p. 12)

According to the European documentation, the conditions of these apprenticeships must also comply with the social protection regulations of each MS and the occupational safety standards of each sector, ensuring that the apprentice has working conditions equivalent to those of other workers:

Calls, to this end, on the Member States to establish national legal quality frameworks on internships and apprenticeships, ensuring in particular employment protection and adequate social security coverage. (European Parliament, Citation2017, p. 12)

Apprentices should be entitled to social protection, including necessary insurance in line with national legislation … The host workplace should comply with relevant rules and regulations on working conditions, in particular health and safety legislation. (Council of the European Union, Citation2018b, p. 4)

Furthermore, EU considers it essential to sign a written contract before the apprenticeship starts. This contract should include the rights and obligations of each of the parties, as well as the remunerations in accordance with the corresponding sectoral collective agreements. Such a contract should protect both the apprentice and the employer in case of default by either party, including release clauses.

Before the start of the apprenticeship a written agreement should be concluded to define the rights and obligations of the apprentice, the employer, and where appropriate the vocational education and training institution, related to learning and working conditions … Apprentices should be paid or otherwise compensated, in line with national or sectoral requirements or collective agreements where they exist, and taking into account arrangements on cost-sharing between employers and public authorities. (Council of the European Union, Citation2018b, p. 4)

Calls for apprenticeship contracts, while protecting the apprentice and providing for a certain flexibility and flexible measures for their application, to permit termination of the contract if the person concerned proves unsuited to his employment or is guilty of serious misconduct. (European Parliament, Citation2011, p. 10)

To guarantee this social coverage of the apprentice status without implying a decrease in the apprenticeships opportunities, especially at the most vulnerable productive sectors, the EU proposes the implementation of certain subsidies in the apprentices’ contributions:

Urges the Member States to provide young people in traineeship, work experience or apprenticeship schemes with full workplace and social security entitlements, subsidising where appropriate a part of their contributions. (European Parliament, Citation2010, p. 7)

With regard to the teaching-learning process, the EU texts deal with three fundamental aspects: contents, space and time distribution. They all configure different patterns of meaning inside the European texts.

The first concern is about ensuring that qualifications and curricular contents of WBL, and specially apprenticeships, are of quality and relevant to the labour market and to students. This means reducing the skill mismatch between what the labour market demands and what the systems offers, as well as keeping in mind future needs which will require transversal skills to deal with those changes:

Ensuring that the qualifications and competences gained and the learning process of apprenticeships are of high quality with defined standards for learning outcomes and quality assurance. Including a strong work-based high-quality learning and training component, which should complement the specific on-the-job skills with broader, transversal and transferable skills, ensuring that participants can adapt to change after finishing the apprenticeship. (Council of the European Union, Citation2013, p. 2)

Member States should ensure that the education and training provision meets the needs of the labour market. In particular, vocational education and training programmes should offer a balanced mix of vocational skills and competences and create work-based learning and apprenticeships opportunities. (European Commission, Citation2021, p. 7)

In respect to spaces, according to the EU texts, training should be provided in different contexts, combining school and in-company training, discarding any options of training based entirely on one of the two spaces:

Increasing opportunities for VET learners to combine learning experiences acquired in different settings. (European Commission, Citation2016, p. 7)

Combine learning in education or training institutions with substantial work-based learning in companies and other workplaces. (Council of the European Union, Citation2018, p. 3)

On the distribution of time, the European texts recommend that at least half of the apprenticeships schedule should take place in the workplace, reducing the time spent at schools and also their predominant role in the training:

A substantial part of the apprenticeship, meaning at least half of it, should be carried out in the workplace. (Council of the European Union, Citation2018b, p. 4)

5. Discussion

This TA of the European Union documentation enables us to shape the answer to the research questions which guide this article, while establishing a direct link with the academic literature.

In respect to the first question (What articulation of the VET training model is promoted by the European Union?), the promotion of a VET system based on WBL is the main milestone in the configuration of an answer. This is reflected in the following statement of the results: “promoting world-class VET … through the promotion of work-based learning” (European Parliament, Citation2013, p. 3). Furthermore, this TA underlines the reasons given by the European institutions to justify the promotion of WBL, which can be summarised as the fight against unemployment and social exclusion among young people and the adaptation to the restructuring of the labour market after the Great Recession of 2008. Claiming greater efficiency in the transition and labour integration of young people, the European documentation goes a step further and promotes the WBL in the form of apprenticeships. This training modality is even included in the European recommendations for strengthening employment after the Great Recession and after the crisis produced by Covid-19. In this case, the scientific literature, alongside with the European institutions, underlines the employment benefits of VET systems based on WBL and, especially, on apprenticeships. Greinert (Citation1998) states that the rate of unskilled employees in Germany was halved after the expansion of the dual system from 1969 onwards, which brought about the enactment of the Vocational Training Act. In the same vein, Deissinger and Gonon (Citation2021) reinforce this role by pointing out that “the dual system is a major pathway into skilled employment” (p. 3). Data on youth unemployment in 2021 reinforces the value of apprenticeships, given that in those countries where they are widespread, youth unemployment rates are low (Germany-6.1%, Austria-8.3%) or Denmark-10.8%). Indeed, rates from those MS where apprenticeships have been a reality for a long time contrast with the rate of countries where apprenticeships are at an embryonic stage or in total absence, such as Spain (30.6%), Italy (26.8%) or France (17.6%) (Eurostat, Citation2022). At this point, the answer to the second question (What examples of good practices in respect to the VET training model are sponsored by the European Union?) begins to take shape. In this case, the training models that appear as explicit references, due to the labour integration of their graduates and the low national youth unemployment rates, coincide with those dual VET models of Germany, Austria and Denmark. The references to them, at this point of the discussion, are still very superficial and general (“refers to the positive experiences with the dual system within VET in countries such as Germany, Austria and Denmark” (European Parliament, Citation2010, p. 6)) and do not include any specific recommendation on the details. This relationship between the EU proposals and the characteristics of the dual VET systems of certain member states will be further analysed later in this discussion.

Along the analysis of the European texts, other reasons for reform in pursuit of dual apprenticeships emerge, beyond the fight against unemployment. Firstly, another pattern of meaning within the European text is the broadening of the number of actors involved in the governance of the VET system. This opens up an area previously limited to the state for consideration by non-state actors, even going so far as to propose the convergence of the system of governance with that present in the corporatist governance model embodied in dual VET structures (Martínez-Izquierdo & Torres, Citation2022). Secondly, the EU flies the flag for the struggle for social cohesion through the empowerment of young people with different backgrounds through participation in social and economic life. Finally, the European texts pursue the introduction of WBL and dual apprenticeships by the MS with the aim of making Europe a world reference in VET and promote its global role.

This promotion of apprenticeships at the European texts is also reinforced by the articulation of the European Alliance for Apprenticeships in 2013 and its most recent version, the renewed European Alliance for Apprenticeships of 2020. This alliance “aims to strengthen the supply, quality, image and mobility of apprenticeships … by bringing together governments, social partners, businesses, chambers, regions, youth organisations, vocational education and training providers and think tanks” (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Citation2020, p. 1). Since its launch in 2013, it has been integrated by 36 countries (27 MS, 5 candidate countries, 4 European Free Trade Association countries) and 332 commitments have been made by different actors of learning. According to Graf and Marques (Citation2022), this alliance is playing an important role in the promotion of a collective skill formation among MS by resembling its main characteristics and thus, some MS are advancing on the reform of their VET system in order to adopt the features of a collectivist training model based on apprenticeships.

Furthermore, according to this TA, the European texts advocate bringing WBL, and in particular apprenticeships, to a larger number of students and productive sectors, calling for subsidies and incentives. An extensive level of expansion is characteristic of countries where apprenticeships have long been a success. In dual VET systems, as Deissinger and Gonon (Citation2021) point out, “dual apprenticeships exist in nearly all branches of the German economy including the professions and parts of the civil service” (p. 4). However, this expansion comes up against the cost of training for the company which prevents companies from joining the system (Asghar et al., Citation2016; Smits & Zwick, Citation2004). According to Pfeifer et al. (Citation2020) and their study based on nearly four thousand companies, the gross costs of training are on average 20,855 euros per year and an average of 6,478 euros per year per apprentice. These costs are a barrier for many companies and sectors, which is why the incentives and subsidies proposed by the European documentation are so important (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Citation2013) and and constitute a reality wherever dual VET works successfully, such as Switzerland (Leemann & Imdorf, Citation2015) or Denmark (Bosch & Charest, Citation2008).

The third major theme resulting from this TA provides a glimpse of the general principles for regulating the Dual VET system proposed by the EU. Firstly, the EU argues the need to establish a clear regulatory framework where the roles of the actors involved must be well defined. This is in line with the Key Success Factors for the implementation of dual VET of the Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion (Citation2013) and the scientific literature. In this respect, Rauner and Wittig (Citation2010) derive from their case study on the dual training systems in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland suggest that “the dual organisation of vocational education needs a consistent legal framework” (p. 249).

The second specification on the general principles for apprenticeships concerns the need to provide training in two different contexts. This has been one of the fundamental characteristics of the leading dual VET systems. Deissinger and Gonon (Citation2021) point out the existence, in the German dual VET system, of two learning sites: “the training company (Ausbildungsbetrieb) and the part-time vocational school (Berufsschule)” (p. 4). The amount of time that the apprentice should spend in each of these two contexts is related with another thematic issue shaped by this TA. The European institutions recommend that at least half of the training time should be provided at the workplace. In the German dual model 75% of training is provided in the company and 25% in school (Pilz & Fürstenau, Citation2019). Theory tells us that the simultaneity of training depends on the version of duality on which the vocational training system is based. According to Rauner and Smith (Citation2010), there are two versions. On the one hand, the one-phase or integrated where apprentices alternate between the different locations in short intervals (days or weeks), as in the case of Germany. On the other hand, alternating or two-phase duality where the training programme is divided into two successive long periods, as in Denmark or Norway. The EU recommendations on time allocation leave the decision on this issue to the national authorities, and avoid showing a preference for one model or another.. However, closely related to this division of learning time, it is worth noting that the traditional duality of theoretical training at school and practical training in the company has been superseded and nowadays it is only an oversimplification of reality. Pilz and Fürstenau (Citation2019) argue that today “the teaching at both learning locations is multidimensional. For example, vocational schools have training workshops for craft occupations and make wide use of simulations to deliver a substantial practical element” (p. 312). This reality connects with another of the patterns of meaning shaped by this TA: ensuring that qualifications and curricular content are of quality and relevant to the labour market.

Furthermore, the EU calls for ensuring that the qualifications, competences and learning processes of apprentices are of high quality, with defined standards for learning outcomes of labour market relevance. Fuller and Unwin (Citation2011) classify the contents of apprenticeships according to whether they are expansive or restrictive. Expansive apprenticeships enable career-oriented occupational competence as a member of a professional community. Restrictive apprenticeships, on the other hand, train in competences specific to the training company. This TA concludes that the EU promotes expansive apprenticeships (“which should complement specific on-the-job skills with broader, transversal and transferable skills, ensuring that participants can adapt to change after completing the apprenticeship”).

Finally, another of the issues raised by this TA is that of guaranteeing the proper functioning of apprenticeships through the creation of a national quality framework. This, according to the European institutions, must protect the apprentice, guaranteeing his training and preventing abuses by the employer and vice versa. It should cover aspects such as the conditions of social security affiliation, the contractual relationship, wages, obligations of the parties and inspection. This contractual relationship is a key feature of dual VET (Choy & Gun-Britt, Citation2018; Deissinger & Gonon, Citation2021; Grollmann, Citation2018) and embodies on paper the fundamental aspects of the quality frameworks (wages, obligations, etc.). For example, the training contract in Germany includes aspects such as the object of training, the start and end dates of the training, its daily duration, the length of the probationary period, holidays, the amount of remuneration, off-site training measures, the conditions under which the contract can be terminated or the rights and duties of both parties (Alemán-Falcón & Calcines-Piñero, Citation2022). In dual VET systems, compliance with these contractual obligations based on training and labour regulations is audited by the relevant authority, such as the chambers in German.

Under the perspective of policy transfer, the role of the EU as an agent of transfer (Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2014) of the dual VET policy remains evident. The theoretical discussion of these results related with the training model along with previous studies based on the governance model (Martínez-Izquierdo & Torres, Citation2022), attests the agency exercised by the EU in the dissemination of dual VET as a model of good practice. This role is crucial for fostering the EU national influence in a non-hierarchical area, the educational, which is governed by a principle of subsidiarity and which operates under a transgovernmental European policy regime (Walkenhorst, Citation2008).

In this case, the themes configured by this TA prove that the EU has been fostering WBL and dual apprenticeships as a model of good practices since the beginning of the 21th century, especially since the Great Recession. This role is fundamental in the process of policy transfer due to the fact that during the cross-national attraction (Phillips & Ochs, Citation2003), the transnational movement of ideas rely upon internal impulses and the potential for externalisation. The reinforcing of internal impulses and the fostering of the potential of externalisation active and favours policy learning processes and legitimate alternatives (Zaunstöck et al., Citation2021). The role played by the EU at the cross-national attraction phase (Phillips & Ochs, Citation2003) increases the internal impulses for reforming MS’s VET systems. By spreading the benefits for young employment presented in dual VET as well as pointing out the shortcomings of national systems in the south of Europe, the UE texts permeated the national debates and enabled a change in the problems perception of the national actors. From a theoretical perspective, this themes embodied in the EU texts worked as a negative external evaluation which suggest the need of changes in the skills formation for adapting them to new demands, growing the internal disaffection of national policy actors.

In parallel, the EU texts has been fostering the potential for dual VET to be externalise by overlapping the training model promoted by the European texts and those training conditions which are characteristics of the MS whose dual VET systems are a successful reality. In this case, the EU promoted the increase of work-based learning as a guiding philosophy. At the same time, the EU texts set as an objective the improvement of the transitions to employment, overlapping the recommended strategies and enabling structures which those which are found in dual VET systems of northern and central Europe.

As with VET governance proposals (Martínez-Izquierdo & Torres, Citation2022), EU recommendations remain imprecise for overlapping with the specific characteristics of the training model of a singular Member State. Certainly, some model of best practice are referenced in a specific way inside the EU documentation, which “calls for more and better apprenticeships; refers to the positive experiences with the dual system of VET within countries such as Germany, Austria and Denmark” (European Parliament, Citation2010, p. 6). However, these MS are also implicitly referenced within the promotion of general common principles for the regulation of the proposed apprenticeships system, whose main points overlap with the actual configurations of these models from a general perspective. As discussed before, the importance of two training contexts, contracts, social security coverage, remunerations and a time distribution with at least half of the time at the workplace is present in the German, the Danish and the Austrian systems. However, this general principles differ in the final configuration of the details of each MS dual VET systems, which makes the EU recommendations general enough for avoiding their alignment with the model of a unique Member State. Indeed, this converges with the European Union’s strategy for these early phases, which recognises the importance of not identifying a single model as an example of good practice at the beginning of the reform period:

Recommendation no 1. Recognise the diversity of starting conditions in VET systems and support exchanges between countries that enable them to pick-up good practice from a diversity of systems. Several EU initiatives emphasise the need for stronger work-based learning and apprenticeships more generally (European Alliance for Apprenticeships, Youth Guarantee initiatives). These initiatives need to recognise that countries have to go through transition phases before reaching the state of having a fully-fledged apprenticeship system. It is also important that these initiatives enable countries to learn from a variety of systems, not just those that represent fully-fledged apprenticeships. Other models have strong features that can be highly relevant for those countries that still have strongly school-based VET models. (Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union & European Parliament, Citation2014, p. 120)

As the same time, the European institutions were aware of the impossibility of a direct transfer of models, as remarked by the European Parliament (Citation2016), which “recognises the value of dual education systems” (p. 7), but pointed out that ”a system used in one Member State cannot be blindly copied by another Member State” and ”calls for exchanges of best practice models involving the social partners” (p. 7). The mention of social actors is important, because by recognising the role of social partners in the actual exchange of policies, their role in policy transfer iwas also strengthened. It will be the struggles for influence and power of other political actors, as foundations, lobbies and agencies from the borrowing and the lending context, which will prevail over one model or another during national reforms.

IFinally, it should be recalled that these texts are part of a strategy aimed at reforming the inefficient systems of certain MS. It would have beeen hardly justifiable on the part of the EU to establish recommendations that did not include all the successful models that are committed to duality, remarking its preference for any MS and excluding others that have been just as successful and effective in their respective contexts.

6. Conclusion

This article sought to explain the role played by the EU in the promotion of dual VET as the reference for the southern Europe reforming MS during the stage of cross-national attraction (Phillips & Ochs, Citation2003). In this sense, it has analysed the fundamental texts resulting from the EU Governance Triangle (Cort, Citation2009) in order to interpret the VET training model promoted by the EU since the beginning of the Copenhagen Process in 2002.

This reflexive Thematic Analysis has concluded that the EU has been promoting a VET training model based in work-based learning as a pillar, preferably articulated in the form of apprenticeships. The three big themes configured by this TA (promoting WBL as a pillar of VET systems, fostering dual apprenticeships as best practices for WBL and promoting general common principles for the regulation of the proposed dual apprenticeships) and the different pattern of meaning comprised therein, show the strong overlap between the dual VET model of certain central and northern Europe MS (Austria, Germany, Denmark) and that promoted by the EU. In addition, beyond these implicit references, there are other more explicit statements that demonstrate the overlap between the EU good practice model and the models of these regions (calls for more and better apprenticeships; references to the positive experiences with the dual system within vocational educational and training in countries such as Germany, Austria and Denmark).

This TA of the documentation resulting from the EU Governance Triangle (Cort, Citation2009) proves the agency role exercised by the EU in the dissemination of dual VET as a model of good practice during the cross-national attraction phase (Phillips & Ochs, Citation2003). This agency led reforming national actors to look at dual VET systems (Martín-Artiles et al., Citation2020) for solutions to their national challenges related with VET. The EU reinforcement of internal impulses and the fostering of the potential of externalisation actived and favoursed policy learning processes and legitimated alternatives (Zaunstöck et al., Citation2021). As previously discussed, the role played by the EU at the cross-national attraction phase (Phillips & Ochs, Citation2003) has increased the internal impulses for reforming MS’s VET systems and the externalization potential. The internal impulses for reforming, in this case negative external evaluation, changes in the needed skills and internal disaffectation, have been fostered by the spread of the benefits presented in dual VET for young employment, social cohesion and global competition with non-EU countries entering a race for development and global leadership. At the same time, they have been reinforced by pointing out the shortcomings of school-based systems, changing the problems perception of the national actors which contributes to a modification of the distribution of forces at the level of each MS. In parallel, the EU texts have fostered the externalization potential of dual VET policies by overlapping its recommendations for VET training model and governance (Martínez-Izquierdo & Torres, Citation2022) and those which are characteristics of dual VET systems of central and northern Europe. At this respect, it can be concluded that the EU has promoted the increase of work-based learning as a guiding philosophy, set the improvement of the transitions to employment as a priority objective and overlapped the recommended strategies and enabling structures which those which are found in dual VET models of central and northen Europe.

At this non-hierarchical vocational education policy area which is ruled by the principle of subsidiarity, the EU’s political influence on national reforms persists in the form of two lines of action: the dissemination of best practices and the promotion of joint reflection (Novoa, Citation2002). As this research has shown, the EU has played its role as an agent of the VET policy making process by using minimum directives and recommendations which promoted dual VET and by disseminating possible solutions to certain problems in the form of best practice examples.

This TA’s intention was not only to analyse the VET training model promoted by the EU and how it coincides or not with the one presented in some MS, but to identify the model of best practice sponsored by the European institutions. Beyond the few explicit references to the dual VET models of certain central and northern MS (Austria, Germany, Denmark), the recommendations of the EU have been still too general for overlapping the specific characteristics of the training model of any of them. Dual VET models along Europe share basis principles but differ in their detail. For that reason, after this analysis, it cannot be concluded that the EU has appropriated any singular MS dual training model as a model of best practice. The analysed EU proposals overlaps with the general principles of all the dual VET systems, without prioritising any of them over the others. This, according to the EU (Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union & European Parliament, Citation2014; European Parliament, Citation2016) was in line with a general strategy of avoiding specific examples at the beginning of the reform cycle, as well as avoiding referencing the detailed features of best practice models so that the reform process did not die in its early stages due to excessive pressure to reform. Furthermore, any given priority would have been seen as a gesture of EU arbitrariness, as the different European dual VET models work successfully in their respective contexts.

Even in the educational and vocational education policy area, where hierarchical intervention by the EU is not possible according to the principle of subsidiarity, the implications for policy transfer of the themes framed along this TA are significant. Future research should analyse their actual level of influence on each of the national actors involved in VET reform and regulation. At the European level, they have influenced inter-MS cooperation in VET initiated with the signing of the Copenhagen Declaration in 2002 on enhanced European cooperation in vocational education and training (VET) by establishing dual VET as the reference. At the national level, they would have permeated the imaginary of political actors, providing them with arguments for questioning school-based systems and looking towards duality. In parallel, at this national level, they may have functioned as a point of reference and legitimacy for reforming governments, not only for the policy borrowing but also for the framing of the problem. The European texts set out a path for a reform based on foreign systems accredited and supported by a significant and legitimate political actor, such as the EU, and at the same time, serve as a starting point. The content of the analysed texts allowed MS to access to legitimate recommendations on the broad outlines of their policy objectives regarding the reform of VET systems and to lay the foundations for the construction of an efficient dual training model adapted to their national context. Lastly, at the local level, while such legal texts do not usually reach the general public or local political and educational actors directly, their echoes in national political discourse and the media could have helped to set up a soft landing for such policies.

Finally, future research should also go further into the European level to elucidate whether the sponsorship of a specific MS dual VET training model as a model of best practice is evident in other EU’s soft power mechanism, as conferences, subsidies, contests, agencies (Dimitrova et al., Citation2016; Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000) or in the European Alliance of Apprenticeships activities. In parallel, future research is needed in the analysis of the role played by others policy actors in the promotion of dual VET models among reforming MS, which is an aspect specificated along the European texts as previously discussed. Specifically, in the Spanish context, future research must focus on the role played by different policy actors in disseminating the German model as an example of good practice and a model for reform, as evidenced by previous research (Marhuenda-Fluixá et al., Citation2019; Martín-Artiles et al., Citation2019).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Luis Martínez-Izquierdo

Martínez-Izquierdo, Luis is a PhD student, as a holder of a research fellowship of the Spanish programme for University Teacher Training (FPU) of the Ministry of Universities, in the Department of Pedagogy at the University of Granada, Spain. He is a member of the teaching staff of the University of Granada’s Early Childhood Education Degree in the subject Comparative Educational Policies of the European Union. His research interests focus on vocational education and training, comparative education, policy transfer and education policy.

Mónica Torres Sánchez

Torres Sánchez, Mónica is Associate Professor of International and Comparative Education at the University of Malaga. She holds a Ph.D. in Educational Sciences at University of Granada (Spain). She was Visiting Scholar at the University of Wisconsin-Madisson sponsored by the José Castillejo Research Program of the Spanish Ministry of Education and Culture. She was the coordinator of the Master Degree of the University of Granada in Research and Innovation in Curriculum and Teacher Education from 2016 to 2020. Her research interests focus on comparative education and educational reforms and educational policies. She is a member of the Comparative Education Society in Europe (CESE) and the Spanish Society of Education Compartive (SEEC).

References

- Alemán-Falcón, J., & Calcines-Piñero, M. A. (2022). La internacionalización del Sistema Dual de Formación Profesional Alemán: Factores para su implementación en otros países. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 30, (57–25). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.30.6029

- Ante, C. (2016). Introduction. In Ante, C. (Ed.), Europeanisation of vocational education and training (pp. 1–33). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41570-3

- Asghar, W., Shah, I. H., & Akhtar, N. (2016). Cost-benefit paradigm of apprenticeship training: Reviewing some existing literature. International Journal of Training Research, 14(1), 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/14480220.2016.1152029

- Bosch, G., & Charest, J. (2008). Vocational training and the labour market in liberal and coordinated economies. Industrial Relations Journal, 39(5), 428–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2338.2008.00497.x

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications, Limited. https://books.google.es/books?id=25lpzgEACAAJ

- Bulmer, S. (2008). Theorizing Europeanization. P. Graziano & M. P. Vink (Eds.), Europeanization: New Research Agendas (pp. 46–58). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230584525_4

- Busemeyer, M., & Trampusch, C. (2012). The political economy of collective skill formation systems. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199599431.001.0001

- Cedefop. (2014). Developing apprenticeships. Briefing note. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/57970

- Choy, S., & Gun-Britt, W. (Eds.). (2018). Integration of vocational education and training experiences purposes, practices and principles (Vol. 29). Springer.

- Cort, P. (2009). The open method of co-ordination in vocational education and training – A triangle of EU governance. In E. R. Desjardins & K. Rubenson (Eds.), Research of vs research for education policy: In an era of transnational policy-making (pp. 163–177). VDM Verlag Dr. Müller.

- Council of the European Union.(2009). Council conclusions of 12 May 2009 on a strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training (‘ET 2020’) (Publication Office of the European Union). https://n9.cl/h3lae

- Council of the European Union. (2013). European Alliance for Apprenticeship Council Declaration (Publication Office of the European Union). http://register.consilium.europa.eu/doc/srv?l=EN&f=ST%2014986%202013%20INIT

- Council of the European Union.(2014). Council conclusions of 20 May 2014 on quality assurance supporting education and training (Publication Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52014XG0614%2807%29&qid=1623666202897

- Council of the European Union.(2018a). Council Decision (EU) 2018/1215 of 16 July 2018 on guidelines for the employment policies of the Member States (Publication Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32018D1215&qid=1622800164326

- Council of the European Union.(2018b). Council Recommendation of 15 March 2018 on a European Framework for Quality and Effective Apprenticeships. (Publication Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018H0502%2801%29

- Council of the European Union.(2020). Council Recommendation of 24 November 2020 on vocational education and training (VET) for sustainable competitiveness, social fairness and resilience 2020/C 417/01 (Publication Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32020H1202%2801%29&qid=1623169870769

- Council of the European Union,& Representatives of the Governments of the Member States.(2006). Conclusions of the Council and the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States, meeting within the Council, on the future priorities for enhanced European cooperation on Vocational Education and Training (VET) (Publications Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A42006X1208%2802%29&qid=1623232372335

- Deissinger, T., & Gonon, P. (2021). The development and cultural foundations of dual apprenticeships – A comparison of Germany and Switzerland. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 73, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2020.1863451

- Dimitrova, A., Boroda, M., Chulitskaya, T., Berbeca, V., & Parvan, T. (2016). Soft, normative or transformative power: What do the EU’s communications with eastern partners reveal about its influence? https://doi.org/10.17169/refubium-25132

- Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion . (2013). Apprenticeship and traineeship schemes in EU27: Key success factors. A guidebook for policy planners and practitioners (Publications Office of the European Union).

- Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion,(2012). Apprenticeship supply in the Member States of the European Union (Publication Office of the European Union). https://op.europa.eu/s/pcRx

- Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. (2020). The renewed European Alliance for apprenticeships: Key objectives. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2767/416056

- Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Unionand European Parliament.(2014). Dual education: A bridge over troubled waters? (Publications Office of the European Union). https://op.europa.eu/s/pdi6

- Dolowitz, D. P., & Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contemporary policy-making. Governance, 13(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00121

- European Commission. (2010). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A new impetus for European cooperation in Vocational Education and Training to support the Europe 2020 strategy (Publication Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52010DC0296

- European Commission.(2012). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, The Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Rethinking Education:Investing in skills for better socio-economic outcomes (Publication Office of the European Union). https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/content/rethinking-education-investing-skills-better-socio-economic-outcomes

- European Commission.(2016). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A new skills Agenda for Europe. Working together to strengthen human capital, employability and competitiveness (Publication Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52016DC0381

- European Commission.(2021). Commission Recommendation (EU) 2021/402 of 4 March 2021 on an effective active support to employment following the COVID-19 crisis (EASE) (Publication Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32021H0402&qid=1622800164326

- European Commission.(2021). Commission Recommendation (EU) 2021/402 of 4 March 2021 on an effective active support to employment following the COVID-19 crisis (EASE). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32021H0402&qid=1622800164326

- European Commission, European Social Partners, & Lithuanian Presidency of the Council of the EU.(2013). Declaration of the European Social Partners, the European Commission and the Lithuanian Presidency of the Council of the European Union. European Alliance for Apprenticeships (Publication Office of the European Union). https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/31665/joint-declaration_apprentiships.pdf

- European Ministers for Vocational Education and Training, European Commission, & European Social Partners. (2006). The Helsinki Communiqué on Enhanced European Cooperation in Vocational Education and Training (Publication Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011IP0263&from=ES

- European Ministers for Vocational Education and Training, European Commission, & European Social Partners.(2010). The Bruges Communiqué on enhanced European Cooperation in Vocational Education and Training for the period 2011-2020 (Publications Office of the European Union). https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/bruges_en.pdf

- European Ministers for Vocational Education and Training, European Social Partners, & European Commission.(2015). Riga Conclusions on a new set of medium-term deliverables in the field of vet for the period 2015-2020, as a result of the review of short-term deliverables defined in the 2010 Bruges Communiqué (Publication Office of the European Union). https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/default/files/document-library-docs/riga-conclusions.pdf

- European Parliament.(2010). European Parliament resolution of 6 July 2010 on promoting youth access to the labour market, strengthening trainee, internship and apprenticeship status (2009/2221(INI)) (Publication Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011IP0263&from=ES

- European Parliament.(2011). European Parliament resolution of 8 June 2011 on European cooperation in vocational education and training to support the Europe 2020 strategy (2010/2234(INI)) (Publication Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011IP0263&from=ES

- European Parliament.(2013). European Parliament resolution of 22 October 2013 on Rethinking Education (2013/2041(INI)) (Publications Office of the European Union) https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52013IP0433&qid=1623169870769

- European Parliament.(2014). European Parliament resolution of 17 July 2014 on Youth Employment (2014/2713(RSP)) (Publication Office of the European Union). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52014IP0010&qid=1623169870769