Abstract

Not only children but also adults now spend much more time in front of the screen (computers, laptops, tablets, phones, TVs, Play Station, other game consoles, etc.) for various reasons: work, study, a lot of free time, communication, entertainment, information retrieval. The aim of this paper is to examine how the time spent in front of the screen at school influence the developing of computer addiction in primary schoolchildren. The development of Internet addiction has negative educational (deterioration of academic performance), medical (reduced mental health, decreased general stress-resistance, risk of depression), and social consequences (reduced quality and quantity of social contacts). The respondents were 120 parents and 120 secondary school students of one of the schools in Moscow. The participants were asked to answer 9 multiple-choice questions. To assess the level of Internet addiction of schoolchildren, the Internet Addiction Test created by K. Young and modified by V.A. Loskutova (Burova) was used. As a result, 69% of the parents surveyed noted that their children spend more than four hours a day on online learning. Proposed approach consists of two stages, which are a gradual reduction of the time children spend on the Internet and the replacement of problematic behavior with other alternatives. The research results provide the knowledge to prevent cyber addiction in schoolchildren and the incentive for further research.

Short summary

Summing up the results of the study, an effective approach for the prevention and solution of the problem of Internet addiction among students during the period of online learning based on cognitive-behavioral therapy was proposed. The approach involves two phases, which are a gradual reduction of the time children spend on the Internet and the replacement of problematic behavior with other alternatives. Future research could consider in detail the factors that contribute to the formation of computer addiction in schoolchildren during online learning, interview students of different ages, and expand the sample.

1. Introduction

It turned out that the threat of the ability of digital technologies and the Internet to take over the daily life of children became a solution to the crisis and did not allow educational institutions to cancel the school year, people to lose their jobs, and students to get bored due to the lack of social contact during the weeks of isolation (Basay et al., Citation2020).

The positive youth development was negatively associated with their Internet addictive behavior (Shek & Yu, Citation2016; Siste et al., Citation2020). The lack of emotional culture is a potential risk factor associated with Internet addiction. But social support (family, parents, relatives, friends, peers) provides valuable aid in developing children’s ability to analyze information and stay safe on the Internet (Mo et al., Citation2018).

Problematic Internet use is another popular concept in the field of cyber addiction research. Today, digital devices and the Internet are part of our life that cannot be replaced. On the Internet, people work, travel, shop, meet with family and friends, watch movies, look for information, listen to music, live a virtual life, relax, and so on. The Internet has also become a very important part of students’ lives (Chou et al., Citation2005). For the student cohort, the Internet has become a good assistant in completing assignments, communicating, and finding information. It is accessible and easy to use and allows finding and processing large amounts of data (Chou, Citation2001).

The growing trends in online education require specific training of teachers. They should promote student academic excellence and prevent student Internet and cyber addiction. The fact is that the Internet is not addictive, but specific applications (games, for example) can attract a child weirdly (Ellis et al., Citation2015).

There are various definitions of online education that have changed over the years and with the development of digital devices. In the scientific literature, online education is referred to as “distance education”, “eLearning”, “online learning”, “blended learning”, “computer learning”, “web learning”, “virtual learning”, “tele-education”, “cyber learning”, “learning over the Internet”, “distributed learning”, etc. (Sun & Chen, Citation2016; Sun et al., Citation2020).

Prolonged exposure to the Internet can increase the risk of problematic use of the Internet (e.g., uncontrolled smartphone use, social media addiction, and gambling addiction; Bowditch et al., Citation2018). The main motive for the study was the goal of optimizing the online learning process to create a favorable learning environment for students and to prevent the formation of computer addiction in them.

The primary intent of this study was to determine parents’ opinions on how the amount of time spent at the computer or smartphone for the purposes of online learning affects the likelihood of Internet addiction development in elementary school students. In line with this, it sought to assess the effectiveness of applying time limits on computer and smartphone use for building healthy relationships with the Internet and technology.

The research objectives were as follows:

- conduct a survey of parents and assess the level of Internet addiction among schoolchildren.

- propose an effective approach to the prevention and solution of the problem of Internet addiction of students during the period of online learning.

2. Theoretical foundations

Today schoolchildren have a legal opportunity to spend more time online, but it is useful to find out whether this situation makes them happy, sad, or bored; whether they have a huge appetite for the Internet and digital devices or are overwhelmed and prefer other activities (Francisco et al., Citation2020).

Chinese researchers estimated the prevalence of smartphone addiction at 26.99%, 17.42% for social media addiction, 14.22% for Internet addiction, and 6.04% for gaming addiction (S. Q. Meng et al., Citation2022). Men had a greater risk of developing Internet addiction than women. This study confirmed the increasing trend of digital addiction caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. A U.S. study found that excessive use of screen media impairs sleep quality, increases the risk of obesity, and does not contribute to academic performance (J. Liu et al., Citation2021). There is also evidence that non-suicidal self-harming behavior may be associated with prolonged Internet use (K. Liang et al., Citation2022). Findings from a study in Switzerland confirm both positive and negative associations between mental health, emotional well-being, and media use in adolescents with internalizing disorders during isolation (Werling et al., Citation2022).

The relationship between media dependence rates in elementary school-aged children, their health, self-esteem, and fathers’ parenting practices was examined (Eo & Lee, Citation2022). Levels of media dependence were 68.8%, 24.9%, and 6.3% for regular users, high-risk users, and potential high-risk users, respectively. In the reference group, children had a high body mass index, media use time increased by 1 hour per day, self-esteem decreased, fathers’ authoritative parenting practices were low, and permissive parenting practices were high.

In Germany, associations between addictive use of digital devices, duration of use, deferred discounting, self-control, and academic performance were examined in children aged 10 to 13 years (Schulz van Endert, Citation2021). Addictive use of digital devices was positively related to time discounting, but self-control disrupted the relationship between these two variables. These results suggest that children’s problematic digital device behavior is comparable to other maladaptive behaviors (e.g., substance abuse, pathological gambling) in terms of impulsive choices, and point to the key role of self-control in reducing the potential risk of digital addiction.

Some researchers are looking for a connection between the style of parent communication with children and the use of the Internet, attitudes towards the Internet, and Internet experience. Some studies show that there is a real link between the two: the highest levels of Internet use by children are observed when parents have a permissive parenting style; the lowest rates are observed when parents have an authoritarian Internet parenting style (Valcke et al., Citation2010).

There is a provision that also examines the influence of parents on the excessive use of the Internet by children. Parents who control their children and their time on the Internet are restricted parents. This explains their significant success in reducing children’s interest in the Internet. But in the future, this parenting approach may lead to risky behavior on the Internet (Sasson & Mesch, Citation2014).

It is because of the controlling parents that the child feels lonely regardless of gender and age and seeks additional comfort and understanding on the Internet. A direct correlation has been found between authoritarian parents, loneliness and cyber addiction (Appel et al., Citation2012). Increased stress levels and high emotional sensitivity are factors that raise adolescents’ propensity to go online (Kaess et al., Citation2017).

Severe Internet addiction among primary schoolchildren is less common but mild Internet addiction is often observed. The level of Internet addiction depends on gender, grade, family relationships, and school atmosphere. All these determinants of Internet addiction should be taken into account when developing preventive and corrective measures (Xin et al., Citation2018). A link has been found between gender, depression and cyber addiction. Depression can be both a cause and consequence of digital addiction, as well as social distance and isolation (L. Liang et al., Citation2016).

Problematic Internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic may be associated with anxiety and depression among children and adolescents (Dong et al., Citation2020). Moreover, fear and anxiety about the disease may last after the recovery from COVID-19. Therefore, it is not clear whether psychological distress at the stage of recovery from COVID-19 differs among schoolchildren with different levels of problematic Internet use (Golberstein et al., Citation2020).

Although problematic Internet use can lead to health problems (Shaw & Black, Citation2008), researchers have proposed a compensatory Internet use model and argued that Internet use is problem-free at one end and problematic at the other (Kardefelt-Winther, Citation2014). However, due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, schoolchildren are likely to use the Internet more often, and for a minority, this will result in problematic Internet use (Chen et al., Citation2021). Researchers have multiply pointed out that stress conditions can be exacerbated by problems with Internet usage control (Chang et al., Citation2020).

For quite a large number of people, self-isolation and the introduction of quarantine measures have caused severe emotional instability due to weakened social ties and reduced social interaction (De Figueiredo et al., Citation2021). There is a growing belief that this state of affairs will increase the level of Internet addiction of the younger generation, and it will be more difficult for them to get offline (X. Liu et al., Citation2020).

Many studies on the matter are characterized by a consensus of opinion that Internet addiction leads to depression. It is not entirely clear what comes out of what, but studies confirm that people with major depressive disorder have Facebook (Lissak, Citation2018) and mobile phone (Park et al., Citation2019) addiction.

3. Methods and materials

The parents were interviewed and an approach to the prevention of cyber addiction in children, which involved limiting the time children spend using digital devices after online learning, was investigated. Controlling the time spent on the Internet by setting an alarm clock or timer reminding the user to stop their online activities is considered one of the ways to prevent and solve the problem of Internet addiction.

3.1. Sample and data

A total of 120 parents of secondary school students of one of the schools in Moscow were interviewed. The parents of the children were surveyed as recently they have had the best opportunity to observe the behavior of their children. The questionnaire was delivered via social media groups that parents used to communicate during the pandemic.

Also, the study involved seventh-graders of the same school. Thus, 120 students were selected, of which 60 were randomly selected as the experimental group and 60 students were included in the control group. The average age of the participants is 12 years. More detailed sample characteristics are presented in Table .

Table 1. Characteristics of research sample

After the end of online learning, the experimental group was limited in the time of using the Internet and gadgets (2 hours a day) while this limitation was absent in the control group. As an alternative to the use of electronic devices, the students were offered light physical exercises, walks in the fresh air, live communication with friends, and other leisure activities not related to the use of the Internet and available during the period of distance learning. The study was approved by an ethics committee, and formal consent was obtained from parents and students participating in the study. After the study was completed, participants were familiarized with the survey results.

3.2. Measures of variables

The study relied on a structured questionnaire which is copyright (Appendix 1). The participants were asked to answer 9 multiple-choice questions. This approach made it possible to identify the role of parents in the formation of cyber addiction in children, as well as whether they exercise control over the time that schoolchildren spend using electronic devices. No irrelevant responses were identified.

To assess the level of Internet addiction of schoolchildren, an Internet addiction test was used (Appendix 2). The questionnaire is based on the Young Internet Addiction Test translated and modified by V.A. Loskutova (Burova). The participant must evaluate each question on a 5—point Likert scale. The points are summed up to determine the final value.

3.3. Data analysis procedure

Research data were analyzed by means of Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 25.0. For better evaluation quality, the ordinal variables were taken as percentages. Apart from this, the mean and standard deviation were assessed to obtain the most relevant results. The main comparisons were made after the t-test and Pearson’s correlation coefficient calculation—they were applied to analyze and evaluate different variables.

The reliability of the Internet addiction test was checked using Cronbach’s alpha. According to Mallery and George (Citation2000), the Cronbach’s alpha values are interpreted as follows: > 0.9 is excellent; > 0.8 is good; 0.7 is acceptable; 0.6 is doubtful; and> 0.5 is bad. The Cronbach’s alpha value for the Internet addiction test was calculated as 0.88 indicating acceptable internal consistency (Cortina, Citation1993). To consider the effectiveness of the proposed approach aimed at preventing cyber addiction, the ANCOVA analysis was used to eliminate the difference between the survey of the two groups.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to calculate the normality of the data obtained in the study. The result of this test was 0.97 (p = 0.23), which indicates the normal distribution of the data. In addition, the Levene’s test was performed to determine the uniformity of variance (F = 3.11, p > 0.05) showing that the assumption is reasonable and that there were no significant differences in the variance between the two groups. Also, the assumption of the homogeneity of the regression slopes was confirmed while indicating the possibility of performing one-way ANCOVA (F = 0.26, p > 0.05).

4. Results

4.1. Results of the parent survey

Online education requires more time in front of a digital device screen, and this is one of the most widely discussed parenting concerns. Thus, 69% of respondents noted that their children spend more than four hours a day studying online, doing homework, looking for extra information, creating presentations, and so on; 31% expressed the opinion that it is 3–4 hours a day. There were other options in the questionnaire, including fewer hours, but these were not selected. This worries parents very much as after school, children spend time in front of computers again. It turns out that they spend the whole day in the virtual environment, especially when it is forbidden to go out.

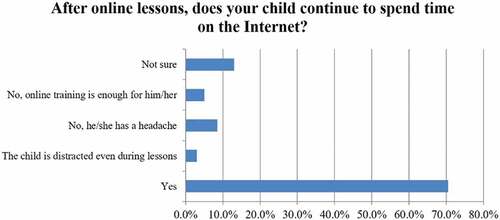

It is assumed that after such a long stay on the educational platform that involves sitting in front of a digital device, a person wants to stand up, walk, rest, or something else. But the majority of parents (70.5%—Figure ) share the point of view that children spend more and more time on the Internet. This is due to the fact that they are not saturated with the use of electronic devices. Schoolchildren are bored with studying, so they rush to switch from the educational window to a game or other entertainment software (communication, listening to music, watching movies). It follows that they have no limit on their use of the Internet: they want to spend more time on the Internet and after the obligatory online classes, there are online hobby classes; 3% of parents noted that their children are distracted even during lessons and open other windows for pleasure. Only 5% of respondents reported that online learning is sufficient for their children and they do not need to spend more time on a tablet or smartphone. Some students get too tired or have a headache (8.5%). And there are 13% of parents who do not have their own opinion on the issue. This information is not a reason to confirm cyber addiction in all children, but a serious issue to discuss the strong influence of the Internet and digital devices on young people. The idea is that a lack of control can result in the overuse of the Internet and digital devices.

The results of another question confirm the conclusion that there is no relationship between a big amount of time spent in front of the computer and the desire not to use digital technologies and the Internet. On the contrary, almost 60% of respondents believe that the formula “the more time you spend in front of the screen, the less the desire to use digital technologies and the Internet” is not true.

As for cyber addiction among elementary school students, learning in the virtual environment gives them an excellent opportunity to spend more and more time on the Internet doing what they love. It is very easy for the student to switch from the learning window to the site for fun. Parents are confident that being in front of the computer, their children can use it for other purposes, not only for learning. The survey showed that students use electronic devices for entertainment purposes during online lessons. Thus, the results were as follows: 46.8% (only during some classes that do not require much student attention); 23.8% (constantly; in some cases, the student listens to the teacher, but at the same time plays computer games); 24.8% of respondents noted that this is impossible as they have parental control over the situation, and 4.6% do not know because they are usually at work.

Many researchers share the idea that improving the computer skills of students is a good prevention of their cyber addiction (Ellis et al., Citation2015). Only 23.3% of parents surveyed positively assess the fact that online learning helps children perceive digital devices as learning tools while 27.5% are negative about this. In their opinion, nothing has changed. The majority of respondents (49.2%) do not have their own opinion; they simply cannot express it, which can be regarded as a sign that they hardly watch the behavior of their children on the Internet.

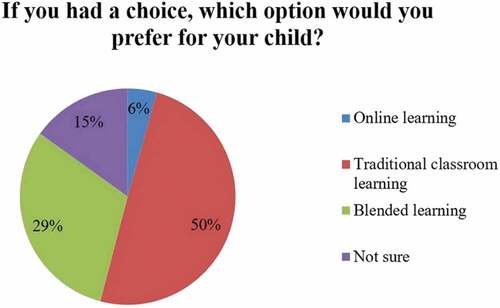

Parents admit that their children get tired of studying, but not of playing computer games. Most of them (55%) have a categorical opinion that e-learning does not occur to the detriment of computer games. Only 35.8% share the opinion that due to online learning, the child does not have enough free time to play after school. Despite the lower percentage, this indicates that the use of information technology for educational purposes is a right step towards neutralizing cyber addiction. According to 25.4% of parents, their children turn away from the screen as soon as the lesson is over, 7.6% go outside to play. But the majority of respondents (49.6%) say that children stay in front of the screen; 17.4% continue to play computer games. This means that the screen attracts like a magnet, and it is difficult for a child to escape. Undoubtedly, this behavior is typical for a cyber-dependent person. It must be monitored at primary school age not to become addicted to the Internet later. When it comes to comparing online and traditional forms of teaching and learning, it is obvious that only a small proportion of parents prefer online learning (6%). Most parents would choose the traditional form of schooling (50%—Figure ); 29% of parents prefer blended learning.

Figure 2. Parents’ preferences regarding the form of teaching and learning in the future (sample—parents, study period—May 2021).

Most parents understand that the future of education is impossible without digital technologies and the Internet (86.7%). Parents are also concerned that children spend so much time in front of the screen and most believe there must be a balance between e-learning and traditional school teaching.

4.2. The level of internet addiction of students

The ANCOVA test results described in Table characterize the level of Internet addiction across the student groups analyzed. As it can be seen from the above, the mean values of this indicator amount to 40.71 for the experimental group and 65.9 for the control group. The possible error, in turn, constitutes 3.45 for the experimental group and 3.59 for the control group. As far as F = 10.84 (with p < 0.05), this difference is considered reliable.

Table 2. Results of the analysis (ANCOVA) of the level of internet addiction of students

As the score of the experimental group was much lower compared to that of the control group, students whose screen time was restricted had a significantly lower risk of developing Internet addiction than those who had no time limits. Moreover, the effect size (η 2) of the proposed approach was 0.62, which means a small to medium effect (Cohen, Citation2013).

4.3. Recommendations for preventing internet addiction among students

Based on the results of the study, we can propose an effective approach to the prevention and solution of the problem of Internet addiction of students during the period of online learning. The approach includes two phases: gradual reduction and restriction of the time children spend on the Internet and replacement of problem behavior (Internet addiction) with other alternative behavior types. This approach is based on the principles of cognitive behavioral psychotherapy, which is the most effective for the prevention and treatment of various addiction types today (Lan et al., Citation2018; Stevens et al., Citation2019).

It is likely that the restriction phase will be difficult for the students at first and require certain assistance. The most important thing to note is that it is parental support that the students need. Parents should be fully aware of the whole essence and seriousness of the problem. They are encouraged to educate children about cyber addiction and monitor the time children spend online. Parents can offer their children all sorts of activities to spend time with benefit instead of surfing the Internet.

Support of the school and teachers is also important. Probably, the school administration should reduce students’ load so that they spend 2–2.5 hours a day at the computer. This approach can ensure significant success in the prevention and solution of the problem of Internet addiction of students during the period of online learning.

5. Discussion

This study adds to the global literature on effective methods for preventing and treating Internet addiction among young children. Despite the dynamic development of modern technology, the vital question of the necessity and effectiveness of computer technology restrictions to prevent Internet addiction in schoolchildren has not yet been sufficiently investigated. We would like to highlight the following studies considering Internet addiction among schoolchildren.

Turkish researchers examined the state of Internet addiction in children and the stress factors causing it during the 2019 coronavirus pandemic (Aközlü et al., Citation2021). The research data were collected with the help of a questionnaire (via Google Forms) between July 15 and 15 December 2020. Among the children participating in the study, 90.3% were asymptomatic and 9.7% had certain symptoms of Internet addiction. Continuous tracking of Covid-related news and pandemic warnings was defined as a factor stimulating children’s desire to hide from negative information and provoking the development of Internet addiction.

This study showed that Internet addiction in children may increase even more unless the pandemic stops. Available research works on the topic confirm this statement by indicating that since distance learning started, children have begun to spend, on average, 3.40 hours online, which is much more than before the pandemic. In general, such inferences overlap with those obtained within the current investigation.

Understanding how the emergence of addiction to the Internet and digital games is connected with social status, position in school society, relationships with other children, and success in school was the subject of a survey of high school students in Jiayi (Tsai et al., Citation2020). It found that 93.2% of high school students play digital games 2–3 times a week. The indicators of schoolchildren’s addiction to digital games, peer relationships and attitudes towards learning are above average. Internet gaming addiction has a low degree of negative correlation with both peer relationships and attitudes towards learning while peer relationships are moderately positively associated with attitudes towards learning. This study is devoted to the educational problems of gaming addiction, which are most often faced by primary school teachers.

In addition, a relationship between the level of activity, Internet addiction and depressive symptoms in university students during the outbreak of coronavirus disease was found (Öztürk et al., Citation2021). IPAQ analysis showed that 28.2% of students were active. The average student depression score was 8.8 ± 6.6, and the average Internet addiction score was 25.1 ± 7.2. A moderately significant positive correlation was found between the average Internet addiction scores and depressive symptoms. No differences were found between the average indicators of depressive symptoms and Internet addiction in active and inactive students. On the contrary, a relationship was found between Internet addiction and depressive symptoms. The researchers concluded that improving the physical and psychological health of university students during the pandemic is important for public health. Therefore, various multi-sectoral approaches such as online physical activity programs are recommended. In addition, students should be taught to balance their time spent at the computer or on the Internet.

Today, there is a significant problem of Internet addiction among children (Shcherbakova, Citation2020). One of the provoking reasons is online learning, which involves the long-term use of digital devices. In the Russian Federation, 56% of children are online most of the day; this indicator is four times higher than those in the European countries (Blank et al., Citation2020).

Many researchers from different countries have developed special recommendations to help adolescents who tend to use the Internet uncontrollably, especially during social isolation because of quarantine (S. Meng et al., Citation2020). In such a situation, they are advised to organize their daily activities wisely, work and rest regularly, eat healthily, exercise, limit recreational Internet use, as well as avoid the excessive use of electronic devices (Vondráčková & Gabrhelík, Citation2016). They can also actively explore emotional regulation strategies such as relaxation training, mindfulness meditation, and cognitive therapy. Setting short-term goals and focusing on school tasks are also helpful. If adolescents find it difficult to cope with problematic or compulsive Internet use, they need to ask parents and professionals for help (Ko et al., Citation2012).

While online teaching inevitably increases adolescent Internet use, teachers should strive to prevent Internet addiction among adolescents by providing them with offline homework assignments and teaching to reduce recreational Internet use (Coccia, Citation2018). Schools should introduce mental health training for adolescents who find it difficult to manage their online learning (Coccia, Citation2019). In addition to knowledge transfer, teachers can also improve adolescents’ coping with stress and psychological problems, including those associated with deteriorated communication between classmates and friends (Coccia, Citation2021; Throuvala et al., Citation2019).

Parents can reduce access to the Internet and prevent Internet addiction in teenagers by limiting their recreational use of the Internet. It is possible to reasonably set an upper Internet use limit excluding the time needed for online learning and to use the automatic disconnection of Internet access when this limit is reached (Karaer & Akdemir, Citation2019). Parents can also create blacklists of sites, use keyword filtering and software restrictions to protect children from harmful information. Meanwhile, parents should set an example for their children. Therefore, they should spend less time on the phone or on the Internet and more time with their children, as well as to track mood changes in children. Good family relationships, friendly atmosphere, and easy communication can prevent the development of Internet addiction (Király et al., Citation2020).

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is used to treat many mental health conditions, including Internet addiction. CBT for the Internet addiction treatment follows the Davis Cognitive Behavioral Model of Internet Addiction, and is usually performed by a professional psychotherapist (Davis, Citation2001; Stevens et al., Citation2019). CBT is effective in treating Internet addiction, and its combination with other therapies such as online support groups and family therapy can increase the effect. During the pandemic, parents can apply CBT techniques to treat their children at home under the remote guidance of a psychotherapist (Wölfling et al., Citation2019).

6. Conclusions

Online education enables students to spend more time in front of the screen of electronic devices (69% of respondents noted that their children spend more than four hours a day studying online). Some children turn away from the screen of digital devices and the Internet, but others find it very difficult to go beyond the virtual space. Parental and teacher control is very important regarding student behavior, time spent on the Internet, and overuse of information and communication technologies (ICT). But not every parent has an opportunity to monitor the time their child spends at the computer as people are often at work. The improvement of digital skills of children and the use of ICTs in education can prevent the development of cyber addiction. Finally, parents clearly state that ICTs and the Internet are an integral part of their child’s educational process (86.7%). It is important that this technological reality is in balance with the natural human lifestyle that is characterized by communication, meeting, interaction and social life.

The results of the test assessing the level of Internet addiction showed that the experimental group has a rather average Internet usage indicator (40.71 points) while the students in the control group are likely to use the Internet more intensively (65.90 points), which may result in serious problems in the future. Summing up the results of the study, an effective approach for the prevention and solution of the problem of Internet addiction among students during the period of online learning based on cognitive-behavioral therapy was proposed. The approach involves two phases, which are a gradual reduction of the time children spend on the Internet and the replacement of problematic behavior with other alternatives.

The limitations of this study should be noted. First of all, future research may consider the possibility of conducting a long-term experiment. For example, researchers can conduct a year-long experiment and test the sustainability of the experiment’s results. The stability and sustainability of the research results are the questions that one needs to consider further. Secondly, it is worth considering an increase of the sample size of the experiment to attract more participants and further improve the accuracy of the research results. Parents were selected based on convenience, so retrospective bias and group discussions may have skewed parents’ responses.

It is also important to provide suggestions for educational, medical, and social policies to prevent and reduce ICT addiction problems in young children. Schools should introduce mental health training for adolescents who find it difficult to manage their online learning. Parents can reduce access to the Internet and prevent Internet addiction in teenagers by limiting their recreational use of the Internet. During the pandemic, parents can apply CBT techniques to treat their children at home under the remote guidance of a psychotherapist.

In general, to prevent the development of Internet addiction, it is recommended to organize one’s daily activities wisely, work and rest regularly, eat right, exercise, limit recreational use of the Internet, and avoid excessive use of electronic devices. Future research could consider in detail the factors that contribute to the formation of computer addiction in schoolchildren during online learning, interview students of different ages, and expand the sample.

Acknowledgements

Rosalia Minnullina has been supported by the Kazan Federal University Strategic Academic Leadership Program.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be available on request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Suad Abdalkareem Alwaely

Suad Abdalkareem Alwaely is a Professor of the Master’s Department in Arabic Language Curricula and Islamic Education at Al Ain University, Abu Dhabi, UAE; and Department of Curriculum and Instruction at Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan. Among research interests are educational technology, modern teaching strategies, scientific thinking skills, and research in the field of artificial intelligence.

Rosalia Minnullina

Rosalia Minnullina has a Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences degree. She is an Assistant Professor of the Department of Preschool and Primary Education Theory at Yelabuga Institute Kazan (Volga Region) Federal University, Yelabuga, Russian Federation. Among research interests are education and digital technologies.

Elena Fedorova

Elena Fedorova has a Doctor of Biological Sciences degree. She is a Professor of the Department of Adaptology and Sports Training at Moscow City University, Moscow, Russian Federation. Among research interests are enzyme systems of living orgasisms, athlete’s adaptation to intensive physical and psychoemotional activity.

Yuliya Lazareva

Yuliya Lazareva has a Candidate of Medical Sciences degree. She is an Assistant professor of the Department of Biology and General Genetics at I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russian Federation. Among research interests are computer addiction and modern technologies in education.

References

- Aközlü, Z., Kolukısa, T., Şahin, Ö. Ö., & Topan, A. (2021). Internet addiction and stressors causing Internet addiction in primary school children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A descriptive and cross-sectional study from Turkey. Addicta-the Turkish Journal on Addictions, 8(1), 65–19. https://doi.org/10.5152/ADDICTA.2021.21032

- Appel, M., Holtz, P., Stiglbauer, B., & Batinic, B. (2012). Parents as a resource: Communication quality affects the relationship between adolescents’ Internet use and loneliness. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1641–1648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.08.003

- Basay, K. B., Basay, O., Akdogan, C., Karaisli, S., Satilmis, M., Gozen, B., & Sekerci, B. N. (2020). Screen use habits among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders: A cross-sectional study from Turkey. Psihologija, 53(3), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI190802009K

- Blank, G., Dutton, W. H., & Lefkowitz, J. (2020). Oxis 2019: Digital divides in Britain are narrowing but deepening. Oxford Internet Surveys. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3522083

- Bowditch, L., Chapman, J., & Naweed, A. (2018). Do coping strategies moderate the relationship between escapism and negative gaming outcomes in World of Warcraft (MMORPG) players? Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.030

- Chang, Y.-H., Chang, K.-C., Hou, W.-L., Lin, C.-Y., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Internet gaming as a coping method among schizophrenic patients facing psychological distress. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(4), 1022–1031. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00081

- Chen, C. Y., Chen, I. H., Pakpour, A. H., Lin, C. Y., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during the COVID-19 school hiatus. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(10), 654–663. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0497

- Chou, C. (2001). Internet heavy use and addiction among Taiwanese college students: An online interview study. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 4(5), 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1089/109493101753235160

- Chou, C., Condron, L., & Belland, J. C. (2005). A review of the research on internet addiction. Educational Psychology Review, 17(4), 363–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-005-8138-1

- Coccia, M. (2018). An introduction to the theories of institutional change. Journal of Economics Library, 5(4), 337–344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1453/jel.v5i4.1788

- Coccia, M. (2019). Intrinsic and extrinsic incentives to support motivation and performance of public organizations. Journal of Economics Bibliography, 6(1), 20–29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1453/jeb.v6i1.1795

- Coccia, M. (2021). Effects of human progress driven by technological change on physical and mental health. Studi Di Sociologia, 2, 113–132. https://doi.org/10.26350/000309_000116

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic Press.

- Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

- Davis, R. A. (2001). A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 17(2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00041-8

- de Figueiredo, C. S., Sandre, P. C., Portugal, L. C. L., Mázala-de-Oliveira, T., da Silva Chagas, L., Raony, Í., Ferreira, E. S., Giestal-de-Araujo, E., Dos Santose, A. A., & Bomfim, P. O. S. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 106, 110171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171

- Dong, H., Yang, F., Lu, X., & Hao, W. (2020). Internet addiction and related psychological factors among children and adolescents in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 751. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00751

- Ellis, W., McAleer, B., & Szakas, J. (2015). Internet addiction risk in the academic environment. Information Systems Education Journal, 13(5), 100–105. http://isedj.org/2015-13/

- Eo, Y. S., & Lee, Y. H. (2022). Associations between children’s health-related characteristics, self-esteem, and fathers’ parenting practices and media addiction among younger school-aged Korean children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 7773. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137773

- Francisco, R., Pedro, M., Delvecchio, E., Espada, J. P., Morales, A., Mazzeschi, C., & Orgilés, M. (2020). Psychological symptoms and behavioral changes in children and adolescents during the early phase of COVID-19 quarantine in three European countries. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 1329. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.570164

- Golberstein, E., Wen, H., & Miller, B. F. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 819–820. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456

- Kaess, M., Parzer, P., Mehl, L., Weil, L., Strittmatter, E., Resch, F., & Koenig, J. (2017). Stress vulnerability in male youth with Internet gaming disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 77, 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.01.008

- Karaer, Y., & Akdemir, D. (2019). Parenting styles, perceived social support and emotion regulation in adolescents with Internet addiction. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 92, 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.03.003

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of Internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

- Király, O., Potenza, M. N., Stein, D. J., King, D. L., Hodgins, D. C., Saunders, J. B., Griffiths, M. D., Gjoneska, B., Billieux, J., Brand, M., Abbott, M. W., Chamberlain, S. R., Corazza, O., Burkauskas, J., Sales, C. M. D., Montag, C., Lochner, C., Grünblatt, E., Wegmann, E., … Demetrovics, Z. (2020). Preventing problematic Internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus guidance. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 100, 152180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152180

- Ko, C. H., Yen, J. Y., Yen, C. F., Chen, C. S., & Chen, C. C. (2012). The association between internet addiction and psychiatric disorder: A review of the literature. European Psychiatry, 27(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.04.011

- Lan, Y., Ding, J. E., Li, W., Li, J., Zhang, Y., Liu, M., & Fu, H. (2018). A pilot study of a group mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for smartphone addiction among university students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 1171–1176. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.103

- Liang, K., Zhao, L., Lei, Y., Zou, K., Ji, S., Wang, R., & Huang, X. (2022). Nonsuicidal self-injury behaviour in a city of China and its association with family environment, media use and psychopathology. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 115, 152311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152311

- Liang, L., Zhou, D., Yuan, C., Shao, A., & Bian, Y. (2016). Gender differences in the relationship between internet addiction and depression: A cross-lagged study in Chinese adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 463–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.043

- Lissak, G. (2018). Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study. Environmental Research, 164, 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.01.015

- Liu, X., Liu, J., & Zhong, X. (2020) Psychological state of college students during COVID-19 epidemic. SSRN Electronic Journal. SSRN 3552814. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3552814.

- Liu, J., Riesch, S., Tien, J., Lipman, T., Pinto-Martin, J., & O’Sullivan, A. (2021). Screen media overuse and associated physical, cognitive, and emotional/behavioral outcomes in children and adolescents: An integrative review. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 36(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.06.003

- Mallery, P., & George, D. (2000). SPSS for Windows step by step. Allyn & Bacon.

- Meng, S. Q., Cheng, J. L., Li, Y. Y., Yang, X. Q., Zheng, J. W., Chang, X. W., Shi, Y., Chen, Y., Lu, L., Sun, Y., Bao, Y. P., & Shi, J. (2022). Global prevalence of digital addiction in general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 92, 102128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102128

- Meng, S., Dong, P., Sun, Y., Li, Y., Chang, X., Sun, G., Zheng, X., Sun, Y., Sun, Y., Yuan, K., Sun, H., Wang, Y., Zhao, M., Tao, R., Domingo, C., Bao, Y., Kosten, T. R., Lu, L., & Shi, J. (2020). Guidelines for prevention and treatment of Internet addiction in adolescents during home quarantine for the COVID-19 pandemic. Heart and Mind, 4(4), 95. https://doi.org/10.4103/hm.hm_36_20

- Mo, P. K., Chan, V. W., Chan, S. W., & Lau, J. T. (2018). The role of social support on emotion dysregulation and Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: A structural equation model. Addictive Behaviors, 82, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.027

- Öztürk, N., Öter, E. G., & Abacıgil, F. (2021). The relationship between the activity level, internet addiction, and depressive symptoms of university students during the coronavirus disease-2019 outbreak cross-sectional study. Meandros Medical and Dental Journal, 22(3), 324–332. https://doi.org/10.4274/meandros.galenos.2021.70457

- Park, S. Y., Yang, S., Shin, C. S., Jang, H., & Park, S. Y. (2019). Long-term symptoms of mobile phone use on mobile phone addiction and depression among Korean adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193584

- Sasson, H., & Mesch, G. (2014). Parental mediation, peer norms and risky online behavior among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.025

- Schulz van Endert, T. (2021). Addictive use of digital devices in young children: Associations with delay discounting, self-control and academic performance. PloS One, 16(6), e0253058. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253058

- Shaw, M., & Black, D. W. (2008). Internet addiction: Definition, assessment, epidemiology and clinical management. CNS Drugs, 22(5), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200822050-00001

- Shcherbakova, D. (2020). Distance learning during the crisis: Opportunities and disadvantages of online technologies. SSRN 3584481 https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3584481

- Shek, D. T., & Yu, L. (2016). Adolescent internet addiction in Hong Kong: Prevalence, change, and correlates. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 29(S1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2015.10.005

- Siste, K., Hanafi, E., Lee Thung Sen, H. C., Adrian, L. P. S., Limawan, A. P., Murtani, B. J., & Suwartono, C. (2020). The impact of physical distancing and associated factors towards Internet addiction among adults in Indonesia during COVID-19 pandemic: A nationwide web-based study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 580977. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.580977

- Stevens, M. W., King, D. L., Dorstyn, D., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2019). Cognitive–behavioral therapy for internet gaming disorder: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 26(2), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2341

- Sun, A., & Chen, X. (2016). Online education and its effective practice: A research review. Journal of Information Technology Education, 15, 157–190. https://doi.org/10.28945/3502

- Sun, Y., Li, Y., Bao, Y., Meng, S., Sun, Y., Schumann, G., Kosten, T., Strang, J., Lu, L., & Shi, J. (2020). Brief report: Increased addictive internet and substance use behavior during the COVID‐19 pandemic in China. The American Journal on Addictions, 29(4), 268–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.13066

- Throuvala, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., Rennoldson, M., & Kuss, D. J. (2019). School-based prevention for adolescent internet addiction: Prevention is the key. A systematic literature review. Current Neuropharmacology, 17(6), 507–525. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X16666180813153806

- Tsai, S. M., Wang, Y. Y., & Weng, C. M. (2020). A study on digital games Internet addiction, peer relationships and learning attitude of senior grade of children in elementary school of Chiayi county. Journal of Education and Learning, 9(3), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v9n3p13

- Valcke, M., Bonte, S., De Wever, B., & Rots, I. (2010). Internet parenting styles and the impact on Internet use of primary school children. Computers & Education, 55(2), 454–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.02.009

- Vondráčková, P., & Gabrhelík, R. (2016). Prevention of Internet addiction: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(4), 568–579. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.085

- Werling, A. M., Walitza, S., Gerstenberg, M., Grünblatt, E., & Drechsler, R. (2022). Media use and emotional distress under COVID-19 lockdown in a clinical sample referred for internalizing disorders: A Swiss adolescents’ perspective. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 147, 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.01.004

- Wölfling, K., Müller, K. W., Dreier, M., Ruckes, C., Deuster, O., Batra, A., Mann, K., Musalek, M., Schuster, A., Lemenager, T., Hanke, S., & Beutel, M. E. (2019). Efficacy of short-term treatment of Internet and computer game addiction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(10), 1018–1025. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1676

- Xin, M., Xing, J., Pengfei, W., Houru, L., Mengcheng, W., & Hong, Z. (2018). Online activities, prevalence of internet addiction and risk factors related to family and school among adolescents in China. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 7, 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2017.10.003

Appendix 1.

Questionnaire

How many hours a day does your child spend at the computer or other device for educational purposes?

more than 4 hours a day;

3–4 hours a day;

less than 3 hours;

1 hour a day.

After online lessons, does your child continue to spend time on the Internet?

yes;

the child is distracted even during lessons and opens other windows for pleasure;

no, he/she has a headache;

no, online training is enough for him/her;

not sure.

Do you agree with the statement “the more time you spend in front of the screen, the less the desire to use digital technologies and the Internet”?

yes;

no;

not sure.

Does the child use electronic devices for entertainment purposes in the course of online classes?

yes, all the time;

only during some classes;

no, I control this situation;

not sure as I work and I am not at home.

Has online learning helped the student develop computer skills and perceive digital devices as a tool for learning and working?

yes;

no;

not sure.

Is online learning an obstacle for a child to play computer games for a long time?

not at all;

due to online learning, the child does not have enough free time to play after school;

not sure.

After online lessons, your child

turns away from the screen;

goes outside to play;

stays in front of the screen;

continues to play computer games.

If you had a choice, which option would you prefer for your child:

online learning;

traditional classroom learning;

blended learning;

not sure.

Do you agree that the education of children in the future is impossible without the use of digital technologies and the Internet?

yes, sure;

there must be a balance between e-learning and traditional classroom teaching;

I am concerned that children spend so much time in front of the screen of their gadgets;

not sure.

Appendix 2.

Internet addiction assessment test

Read the following questions carefully and use the scale on the right to indicate the answers.