Abstract

This original research is directed towards the information literacy of international master’s students, focusing on the evaluation of their information-seeking behaviour during competitive and business intelligence processes, together with the subsequent verification methods they use once the desired information is found. During this research, 207 students received a test with questions related to business information literacy, with either one or more options or free-text answers. The results showed a significant lack of information literacy in the use of information sources, including knowledge about their existence and consequent search habits, but they did at least also show a fundamental awareness of verification methods. The students also demonstrated awareness of the significance of data visualisation needs when reporting the contexts found in business intelligence process data.

1. Introduction

Information literacy is arguably one of the most critical values in present-day society. To begin with, we need to understand that information literacy is not a single entity in the general human literacy model, but rather a complex of knowledge, abilities, habits, and experience coming from the fields of librarianship, information science, computer literacy, information technology, and learning (Ralph, Citation1999; C. S. Bruce, Citation1997). Information-seeking behaviour, and our perception of it, have been studied in the context of science, research, and academic activities since the 1950s, predominantly in western countries, creating a sustainable and competitive knowledge society at a time of turbulence and serious geopolitical conflict. The significance of, and emphasis on relevant information gathering, building information infrastructure for time-effective and value-added information or document delivery, and investing in educational activities were key factors that brought with them extraordinary competitive advantage. For example, the importance of individual access to information and the ability to handle a large amount of data and information was emphasised by the strengthening effect on networking technologies arising from the ARPA agency. It was followed by the idea of effective on-line information communication proposed by Licklider (Licklider, Citation1960, Citation1965; Licklider & Clark, Citation1962). Their aim was directed towards designing a man-computer partnership for military, science, business, and educational purposes, where the human was responsible for cognitive processes, from defining goals to supporting the decision-making process, and the computer was a service for storing, retrieval, calculation and automation, with the two together supporting creative, intellectual work. This idea also played a crucial role in speeding up the process of obtaining and accessing the required information. Digitalisation, the massively growing number of online-accessible databases and the subsequent information explosion inevitably meant negative societal trends such as information overload, lack of information professionals, and the growing accessibility of the information gap. It is evident that without a proper literacy defence, waves of disinformation and misinformation could lead to harmful and adverse human behaviour, but on the other hand a lack of information literacy slows down innovation and momentum, which affects our economy and, ultimately, the life of every individual. Thus, an information-literate society means lower risks of slowing economy and innovations, out-of-date education, and insecurity.

The individual perception of information literacy relates to the following core phases: need—collect—use. Several studies have demonstrated the concepts of information needs and how to tie them theoretically to human behaviour and situations where information is needed. Wilson (Citation2006) suggests excluding the term information need from the professional dictionary and substituting it with information seeking towards the satisfaction of needs. If we put such behaviour in the context of physiological, affective and cognitive needs, it does not necessarily come with immediate trigger-seeking because of possible mental, or real-world obstacles. Minder (Citation1962) identified three information needs for scientists: firstly, to be able to keep momentum with actual research activities and developments within their fields; secondly to find a specific piece of information; lastly, to be able to conduct a search resulting in maximum recall value using a specific search strategy for this scenario. Furthermore, we need to apply the possible negative human factors of information-seeking behaviour such as fatigue, lack of search preparations, ignorance of professional search methods, and lack of experience, including tacit knowledge that affects the input needs recognition of a specific user. In addition, we can also distinguish the characteristics of information needs. Ellis (Citation1989) described how the initial phase of scientific research consists of the need for key papers that reveal relevant references, including influencers in the desired field.

When it comes to information collection, the information-literate person should first determine the information sources, their quality metrics and content coverage, and understand the search possibilities, query syntax rules, and results of data interpretation. Connaway et al. (Citation2011) suggested that at the end of the search process there are two kinds of possible situations: the information need is solved, and the information-seeking process can be stopped, or the information need has not been met and the information-seeking process continues. Significant work was done by Bates in the 1970s (Bates, Citation1977a, Citation1977b, Citation1979a, Citation1979b) regarding the quality of the search process and filtering the result data. Bates discussed the search problems, search effectivity, and design search tactics supporting the collection process in following groups: 1) monitoring tactics leading to the searcher’s effectivity and productivity; 2) file structure tactics leading to optimal work with an information source or file consisting of potentially relevant information; 3) search formulation tactics leading to effective queries in terms of precision and recall; 4) term tactics as a set of optimal steps to identify key terms for queries. Bates (Citation1989) further analysed how the quality of this process is restricted by lack of time and designed the cherry-picking search method as a reaction to the increasing number of online sources and critics of traditional retrieval models (Robertson, Citation1977; Salton, Citation1968). Her model represents the sequences in search behaviour resulting in two scenarios: 1) search queries are evolving and not static; 2) instead of a single best-retrieved set, users continue to use berry-picking patterns. Moreover, her proposed model reflects user behaviour with respect to use of different search techniques and goes beyond bibliographic databases.

The use of the resulting information points out the user’s ability to understand the relation of precision and recall and the designed search strategy, and, in addition, possibly to conduct subsequent searches for data validation and verification. This final stage pinpoints the user’s satisfaction. It serves as a new starting point when novel information needs evolve with the perspective of using the original queries and result sets for filtering, applying different search tactics, or applying a completely different search strategy. The problem of distinguishing whether the result set consists of helpful information or not, so that the users’ information needs are solved, depends on the perception of the context of these needs, both from the internal and external perspectives (H. Bruce, Citation2005). Bruce also proposed that if the user found any information useful and relevant to his information need, he should be able to build a personal information collection. Then he is prepared for later use when new or same information need will occur.

Academic perception of information literacy is described by Elmborg (Citation2006) as the ability to read, interpret and produce information, and he pointed out that it should be a skill for all university students, concluding that librarians who are formally in charge of information literacy education at university should not rely on its definition, but rather on critically important practice. Johnston and Webber (Citation2003) laid stress on the leadership of universities regarding their policies when it comes to information literacy and identified its core elements, particularly appropriate information-seeking behaviour, relevant information collection, and the ethical use of such information. But such adoption has not been a trivial process. As mentioned in (Behrens, Citation1994), due to information literacy, librarians have made systematic efforts to change this situation since the late 1990s and have tried to implement information literacy goals and standards as a response to that negative trend. Educational reforms that aim to change the structure of standards often rely on persons without proper information science or librarianship background, as can be seen, e.g., in the Czech Republic, where the Ministry of Education determines the structure of legal documents for education. Even in 2021, there is no formal acceptance of information and digital literacy in legal documents because of political disagreements. Moreover, even a couple of years ago the website of the ministry confused the terms “computer literacy” and “information literacy”. If the data and information-driven twenty-first century means there are higher requirements on student creativity, employees’ performance, and fast and optimal decision-making processes leading to results, the foundations of information literacy ought to come out initially from education laws. As Shapiro and Hughes (Citation1996) proposed, the new curricular multidimensional framework respecting the integration of knowledge and information affecting the whole society, in fact, their approach to self-development, self-education; and to be able to rebuild educational models and contribute to democratising access to information and improving information-seeking behaviour across the globe.

2. Literature review

A large number of studies describe the level of information literacy in the university environment, particularly of research students. We have chosen to narrow this literature review based upon the learning objects supporting information literacy, level of information literacy determination, and the obstacles which either students or faculties are facing. Çoklar et al. (Citation2017) identified information literacy level as a significant determinant of increasing abilities of evaluation, purposeful thinking, trial and error, select main ideas, control, and problem-solving factors and contrary effects such as decreasing disorientation. Brand-Gruwel et al. (Citation2005) worked with two different groups of users (senior PhD students and freshmen) defined as experts and novices with regard to their cognitive skills in information problem solving and designed a set of instructional steps showing how to effectively support information literacy on a higher educational level. Carlson et al. (Citation2011) discovered the need for accommodation both the data producer’s viewpoint as well as that of the data consumer and examined the data information literacy topics according to Association of College & Research Libraries standards, leading to a recommendation to build a specific information literacy program that reflects them. Smith Macklin (Citation2001) claims that students entering universities often do not have a chance to fully understand the importance of information literacy due to fact that faculties often misinterpret the term itself, and he introduces a new method of teaching information literacy skills. Song (Citation2004) researched how international business students use electronic library information systems and provided evidence of significant no-experience situations with a perspective of setting up a unique information literacy program. Pinto and Broady‐Preston (Citation2012) worked with a group of history students and analysed four categories of variables (search, evaluation, processing, and communication-dissemination of information) with results showing that variables related to information processing show high scores in belief in importance and skills self-assessment among students. By contrast, variables related to technological advances show the worst results. Janke et al. (Citation2012) introduced a learning project on a group of nursing research students with the aim of improving their use of evidence in their information literacy learning. Activities were based on collaboration in groups and confirmed the positive feedback from students with regard to cooperation. Contrary, Kurbanoglu (Citation2003) referred to the concept of self-efficacy proposed by Bandura (Citation1977) and put it in the context of information literacy. The students that participated in the research had the highest increase of self-efficacy level in the third year of university education. The results also demonstrated that the students needed more practice to exploit the relevant experience leading to this positive trend. Scott et al. (Citation2000) analysed the state of information literacy expectations of medical educators and the level of computing skills among entering students with a final statement that the basic information skills should be in the scope of undergraduate medical education. Witherspoon et al. (Citation2022) presented a survey of undergraduate science instructors and designed practical recommendations when teaching information literacy. Firstly, science librarians should focus not only on teaching search skills but also on identifying the ways in which undergraduate students, especially in their first two years, can access more easily absorbable intellectual material (e.g., reviews). Secondly, they should also support students by directing them to non-peer-reviewed material (e.g., popular science articles). Lastly, librarians should teach upper-year undergraduates to evaluate environmental and contextual research. The survey also suggested possible methods as to how science librarians should maximize the effect of their teaching. Pinto et al. (Citation2022) have shown undergraduate students’ perception of information literacy during COVID-19, and identified possible improvements in teaching technical platforms, teaching methods, teacher motivation, and teacher–librarian interactions. Mensah Borteye et al. (Citation2022) have studied how students use remote access to electronic resources and confirmed a significant trend in this direction. Sanches et al. (Citation2022) stressed that collaboration among academic librarians and teachers is highly needed and can lead to a strengthened relationship between critical thinking and the information literacy of university students. Jones and Mastrorilli (Citation2022) have conducted a mix-methods survey and confirmed that universities should implement standalone credit-bearing information literacy courses with the direct support of the academic library. Dann et al. (Citation2022) carried out a study with a significant sample of respondents. A total of 1,333 first-year students participated in their survey. The aim of the research was to monitor the level of information literacy as students transited from high school to the university environment. Their conclusion confirms the importance of teaching information literacy immediately after student enrolment, as this leads to an increasing rate of success and retention rates.

3. Problem statement

Our Competitive and Business Intelligence course, organised at Prague University of Economics and Business, is mandatory for international students of business, economics, and informatics. Both branches of this course rely on the gathering and collecting of relevant data and information about the external business environment, then transforming that data and information into meaningful conclusions supporting the strategic decision-making process in different types of business and public entities, from small and medium enterprises through large corporates to national or multinational institutions. The impact of their information-seeking behaviour is crucial when comes to real business situations, and so they are required to solve non-trivial key intelligence questions, and to demonstrate the intelligence cycle, which consists of planning (identifying the business information needs), collection (present their abilities to work with a wide range of data and information sources to gather relevant entities and to verify them), analysis (transform data and information entities into actionable visualisations) and dissemination (present their results and defend their conclusions).

Before each of the courses began, we needed to analyse and uncover any of the students’ possible gaps and blind spots and evaluate their level of information literacy. The underlying factors of this analysis are the problems in competitive and business intelligence processes, defined by correct, unbiased, and with-tacit-knowledge-supported information needs (Maungwa & Fourie, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Furthermore, decision-making information needs cannot be simply interpreted at the outset due to numerous external factors, and subsequently an individual intelligence process collecting information signals and transformed intelligence, and distributing this intelligence to management, cannot be executed quickly without some confrontation with reality. But this moment itself becomes the new turning point when other information is needed (Salles, Citation2006). Thus, information literacy plays a crucial role for competitive and business intelligence analysts who are responsible for understanding and, preferably, specifying information needs; or, in some cases, recommending the extension of the scope of the information needs. Secondly, they are able to determine the data and information sources—to support or be a key player of company information management. Thirdly, they can be a key source for members of top management because of the continuous character of this process.

It is evident that relevance plays a crucial role in the present turbulent data society, and management—which is under constant pressure—cannot allow any of the company subprocesses to be brought into unreasonable risk situations. These problems have changed the scope of the course to the context of emphasising information literacy needs, and they have attracted significant attention from both the private and public sectors. Our intention of working with the business information literacy of students initially appeared in 2018, when the first courses were organised for both winter and summer semesters. Students struggled with search and analysis problems in respect to surface web and deep web sources and were not able to identify optimal data or information search; moreover, if a relevant search was targeted, we discovered limited abilities to use advanced search methods. We prepared an entry survey to build upon the information literacy keystones, and we requested students to complete this before the course began. We used the first results for course structure optimisation, but when more responses were gathered, we were able to identify the actual state of information literacy.

4. Methodology

According to the reviewed studies, we decided to set up an entry survey for new students on our course, consisting of seventeen questions: three questions for study field, territoriality, and gender identification; nine one-possible-answer questions focused on data and information collection processes, information tools and analytical processes including market perspective; four questions about their information-seeking behaviour habits; and one question regarding data visualisation advantage. The blocks of questions were created so that they would represent critically important entry knowledge for the course and what we expected as a knowledge norm in terms of information literacy to be achieved during bachelor studies. The first block described the present data and information environment. Students should be able to distinguish the surface web and deep web environment and confirm knowledge not only about particular sources but also to identify the differences between those two web layers. On the one hand, even if they were not able to identify the concrete source as a correct answer, they could logically estimate it from other options. The following block of questions targeted the abilities to work efficiently with search syntaxes in specific data and information sources using correct wild cards, proximity operators, and using classification schemes, which we considered crucial and critically important not only in the competitive and business intelligence processes, but also during thesis preparations and writing. Moreover, classification systems have a similar position in the scope of intelligence studies. Their use could also verify the advanced level of students’ business information literacy. The third block consists of a question focused on surface web hacking, specifically to Google Dorking, that is a foundation part of open-source intelligence methods. It is widely used not only for security purposes but also for business environment scanning. The fourth block challenged students with particular deep web sources for possible search tasks directed towards business analysis (business reputation, financials, relevant contact information, etc.) and state-of-the-art searchers with regard to technology. The fifth block represents a question regarding knowledge of Porter’s model and should confirm the ability to identify individual business cases from collected data and information, or to identify the sources for the specific force analysis. Furthermore, students answered their daily information-seeking behaviour habits that also provided us a particular insight into their critical thinking. Finally, in the sixth block, free-text answers regarding the verification process and data story-telling advantage closed the survey. Table summarises the topic blocks.

Table 1. The topic blocks of survey

Our aim was not to stress students or put them under pressure. We did not limit their cooperation, nor the use of other sources to find the right answer. Last but not least, they were not linked to other regular surveys they face in various subjects.

5. Findings

Our findings demonstrate several trends among university students regarding their information literacy level with respect to particular information-seeking behaviour characteristics. We have decided to represent this in three individual blocks with particular visualisations or figures. The reason for this decision follows from the key competitive and business intelligence process line of our course: find—understand—use. We have also built a visualisation application of our results so that readers are able to identify their own analysis.

5.1. Information-seeking behaviour of the students

Students had to identify at the beginning of the survey which information source comes from the surface web environment. It is the kind of web environment which, although it does not provide a comfort information zone for data and information collection, should not be avoided as a source in the context of intelligence tasks, and should be able to operate with the fact that the content is indexed by traditional search engines. The results represent the fact that 55 % of respondents are able to recognise a source considered to be a surface web source. Furthermore, the deep web environment represents a crucial web layer for a vast number of competitive intelligence tasks with an aspect of relevancy of data and information sources. Moreover, a majority of sources are operated by official institutions, non-profit organisations, and traditional commercial bodies with an appropriate reputation, and they provide critically important knowledge for intelligence officers and analysts. The deep web environment is created by content that is not indexed by the aforementioned engines. Only 12 % of respondents picked the correct answer. Our further questions covered advanced search methods, particularly proximity operators, wild cards and specific search field codes. As far as proximity operators are concerned, students had to identify in which situation proximity operators are mostly used. 28 % of students selected the correct option, specifically that they would use the operators when they need to narrow the result set. Furthermore, an incorrectly used wildcard was selected by 46 % of participants. Thirteen percent of students misused advanced search field codes. Subsequently, we wanted to know from our respondents whether they were aware of classification systems. This issue raised some concerns about awareness of this topic, but in our course we are also intensively engaged in patent and trademark searching, and classification systems and schemes, are essential tools—not only the relationship of recall and precision, but also because of situations within business processes that must be supported by verified data. We did try to make the set of answers easier for students by giving them the option to choose Google Trends as a correct response, which is obviously not a classification scheme, and 31 % of students knew the correct answer.

We summed up the core data about information-seeking behaviour trends in Table .

Table 2. Information-seeking behaviour survey core results

We also asked the students about their daily habits in the context of searching data and information. Unsurprisingly, 100 % mentioned Google as one of the sources; further answers included Bing, DuckDuckGo, Yandex, but with only a few answers (around ten). They also identified an average number of keywords used during one ordinary search task. 52 % of students use three keywords.

5.2. Verification process

We have asked students about their verification methods and also how they distinguish possible disinformation. Naturally, these questions are mainly focused on the surface web environment as a heavily information-polluted layer. This question was based on free text, where students could also write related ideas. Multiple source check (M), Check the credibility of the source (C), Googling (G), Do not know (N).

5.3. Visualisation and decision-making process

Students also admitted that visualisations strongly affect the decision-making process. In the qualitative free-text answers, they see possible situations regarding using data story-telling and similar visualisation approaches, namely significantly speeded-up responsible decisions based on reliable data validation, as opposed to the risk of wrongly interpreted data and lack of validation that lead to incompetent and harmful decisions. More interestingly, individual answers mentioned the aspect of seeing-the-context. We have created six classes of answers (see, ): Better decision-making process and understanding the problem (B); Worse decision-making process if data is misinterpreted (W); Influence perception of the problem (I); Better memorising process (M); Do not know (or in a minor way)

6. Discussion

This study provides insights on the information literacy level of international students that participated in the Competitive and Business Intelligence course—an intensive educational program when it comes to identifying, collecting, analysing, and disseminating external data and information entities. The results proved a significant gap in students regarding their knowledge of the current information environment together with advanced search methods, limited information-seeking behaviour habits, at least a basic level of the verification process, and the ability to identify the advantage of visualisation methods.

The results also reflect the current state of information overload at the senior management level of many companies as discussed, for example, in Černý et al. (Citation2022), possibly leading to a high-risk human decision-making process as the most crucial part of competitive and business intelligence processes. The reason for our attitude—to implement data and information literacy curricula in the course—is now even more critically important, so that our university can produce highly motivated and information-literate managers instead of overloaded white-collar workers. Moreover, the structure of the information sources for both intelligence studies varies with high frequency, and it needs to be regularly analyzed on searching functionalities, indexes, data, and information synthesis and reporting.

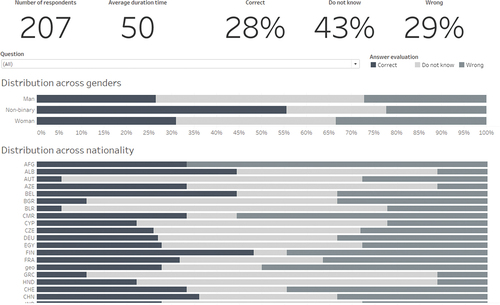

To gain a detailed insight into the issues of information literacy, we designed an interactive dashboard, shown in Figure (beyond the presentation of results in Table ) to provide an overview of information literacy regarding the use of information sources, including knowledge about their existence and consequent search habits, etc. In order to achieve interactivity, we chose the Tableau platform, which is one of the industry leaders according to Richardson et al. (Citation2021). Specifically, Tableau Desktop and Tableau Public were used to create the dashboard and publish it.

Table 3. Verification process results

The design is based on the principles defined by Few (Citation2012) and Knaflic (Citation2015); the above conclusions broaden the view of the results (see, Table , Table , Table ). At the top, we provide a basic overview of the distribution of answers (correct answer; do not know the answer; wrong answer), the total number of respondents, and the distribution across genders and individual states (taking into account the response distribution). A simple text and stacked bar graphs in a horizontal form were used for visualisation, where 100 % of the answers and their distribution are always captured. Within the dashboard, it is possible to analyse all answers, focus on specific questions or perform other analyses as described above.

Table 4. Visualisation & verification results

The proposed analytical solution will serve to grow business information literacy by being able to help identify places to improve and help those responsible for better targeting educational activities. They can perform analyses independently within Self-Service Business Intelligence. This brings us to a state of data-informed decision (Potančok, Citation2019).

7. Conclusion

Competitive and Business Intelligence subjects stand for the critically important ability to work with a large portfolio of data and information sources with respect to identifying business information needs, determining core sources followed by their proper use, analysing the context and disseminating results. Our findings open the discussion about the future business environment and getting (global, national) competitive advantage without proper business information literacy. It is evident that those states supporting information literacy in their educational systems are likely to achieve a stronger economy. A business (e.g., an SME) will have a shorter reaction time for their innovation process and product change cycles, and easier identification of competitive manoeuvres. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, we have built our survey on a present information environment, critically important and underlying methods of collecting data and information, and demonstration of the ability to verify and analyse them. The findings also represent a limited view on a specific information needs solution for students. Secondly, inadequate information literacy among students reflects the problem of the structure of educational systems and an inefficient approach for updating the national curriculum concerning not only information literacy but also digital literacy, critical thinking, and forcing the use of “common sense” when analysing problems. This in turn is followed by the fact that teachers from kindergartens, elementary schools and high schools where literacy topics should be discussed are also facing a lack of relevant educators. There is a strong recommendation to implement information literacy into national education legal directives rather than initiatives that cannot cover target communities; children from pre-school age to high school students. This step could be a significant measure that affects the future competitive advantage of countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bates, M. J. (1977a). Factors affecting subject catalog search success. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 28(3), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/ASI.4630280304

- Bates, M. J. (1977b). System meets user: Problems in matching subject search terms. Information Processing and Management, 13(6), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4573(77)90056-5

- Bates, M. J. (1979a). Idea tactics. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 30(5), 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/ASI.4630300507

- Bates, M. J. (1979b). Information search tactics. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 30(4), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/ASI.4630300406

- Bates, M. J. (1989). The design of browsing and berrypicking techniques for the online search interface. Online Review, 13(5), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1108/EB024320

- Behrens, S. J. (1994). A conceptual analysis and historical overview of information literacy. College & Research Libraries, 55(4), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl_55_04_309

- Borteye, E. M., Lamptey, R. B., Humphrey-Ackumey, S. A. Y., & Owusu-Ansah, A. A. (2022). Awareness and use of remote access to electronic resources by postgraduate students in a university. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 16(3–4), 216–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2022.2137270

- Brand-Gruwel, S., Wopereis, I., & Vermetten, Y. (2005). Information problem solving by experts and novices: Analysis of a complex cognitive skill. Computers in Human Behavior, 21(3 SPEC. IS), 487–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2004.10.005

- Bruce, C. S. (1997). the seven faces of information literacy. Auslib Press.

- Bruce, H. (2005). Personal anticipated information need.”. Information Research, 10(3), Professor T.D. Wilson. http://informationr.net/ir/10-3/paper232.html

- Carlson, J., Fosmire, M., Miller, C. C., & Nelson, M. S. (2011). Determining data information literacy needs: A study of students and research faculty. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 11(2), 629–657. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2011.0022

- Černý, J., Potančok, M., & Castro Hernandez, E. (2022). Toward a typology of weak-signal early alert systems: Functional early warning systems in the post-COVID age. Online Information Review, 46(5), 904–919. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-11-2020-0513

- Çoklar, A. N., Yaman, N. D., & Yurdakul, I. K. (2017). Information literacy and digital nativity as determinants of online information search strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.050

- Connaway, L. S., Dickey, T. J., & Radford, M. L. (2011). If it is too inconvenient I’m not going after it:’ Convenience as a critical factor in information-seeking behaviors. Library & Information Science Research, 33(3), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LISR.2010.12.002

- Dann, B. J., Drabble, A., & Martin, J. (2022). Reading between the lines: An examination of first-year university students’ perceptions of and confidence with information literacy. Journal of Information Literacy, 16(1), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.11645/16.1.3106

- Ellis, D. (1989). A behavioural approach to information retrieval system design. Journal of Documentation, 45(3), 171–212. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026843

- Elmborg, J. (2006). Critical information literacy: Implications for instructional practice. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 32(2), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ACALIB.2005.12.004

- Few, S. (2012). Show me the numbers: Designing tables and graphs to enlighten. Analytics Press.

- Janke, R., Pesut, B., & Erbacker, L. (2012). Promoting information literacy through collaborative service learning in an undergraduate research course. Nurse Education Today, 32(8), 920–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2011.09.016

- Johnston, B., & Webber, S. (2003). Information literacy in higher education: A review and case study. Studies in Higher Education, 28(3), 335–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070309295

- Jones, W. L., & Mastrorilli, T. (2022). Assessing the impact of an information literacy course on students’ academic achievement: A mixed-methods study. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 17(2), 61–87. https://doi.org/10.18438/EBLIP30090

- Knaflic, C. N. (2015). Storytelling with data: A data visualization guide for business professionals. John Wiley & Sons.

- Kurbanoglu, S. S. (2003). Self-Efficacy: A concept closely linked to information literacy and lifelong learning. Journal of Documentation, 59(6), 635–646. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410310506295

- Licklider, J. C. R. (1960). Man-Computer symbiosis. IRE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics, HFE-1(1),4–11. HFE-1. https://doi.org/10.1109/THFE2.1960.4503259

- Licklider, J. C. R. (1965). Libraries of Future. MIT Press.

- Licklider, J. C. R., & Clark, W. E. 1962. “Online man-computer communication.” Spring Joint Computer Conference, May 1-3, 1962, San Francisco, California, Association for Computing Machinery, 21, 113–128.

- Maungwa, T., & Fourie, L. (2018a). Exploring and understanding the causes of competitive intelligence failures: An information behaviour lens. Information Research, 23(4). http://www.informationr.net/ir/23-4/isic2018/isic1813.html

- Maungwa, T., & Fourie, L. (2018b). Competitive intelligence failures: An information behaviour lens to key intelligence and information needs. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 70(4), 367–389. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-01-2018-0018

- Minder, T. L. (1962). Scientists’ approaches to information. The Library Quarterly, 32(2), 178–179. https://doi.org/10.1086/619007

- Pinto, M., & Broady‐Preston, J. (2012). Information literacy perceptions and behaviour among history students. Aslib Proceedings: New Information Perspectives, 64(3), 304–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012531211244644

- Pinto, M., Caballero Mariscal, D., & Segura, A. (2022). Experiences of information literacy and mobile technologies amongst undergraduates in times of COVID. A qualitative approach. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 74(2), 181–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-10-2020-0333/FULL/XML

- Potančok, M. (2019). Role of data and intuition in decision making processes. Journal of Systems Integration, 10(3), 31–34. https://doi.org/10.20470/jsi.v10i3.377

- Ralph, D. (1999). “Information literacy and foundations for lifelong learning.”. Concept, Challenge, Conundrum: From Library Skills to Information Literacy, 6–14. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED443439.pdf

- Richardson, J., Schlegel, K., Sallam, R., Kronz, A., & Sun, J. 2021. Magic quadrant for analytics and business intelligence platforms. Gartner, February 15. Accessed 18 November 2021. https://www.simplydynamics.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Gartner-Magic-Quadrant-for-Analytics-and-Business-Intelligence-Platforms-Report-2021.pdf

- Robertson, S. E. (1977). Theories and models in information retrieval. Journal of Documentation, 33(2), 126–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026639

- Salles, M. (2006). Decision making in SMEs and information requirements for competitive intelligence. Production Planning & Control, 17(3), 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537280500285367

- Salton, G. (1968). Automatic information organization and retrieval. McGraw-Hill.

- Sanches, T., Lopes, C., & Antunes, M. L. 2022. “Critical thinking in information literacy pedagogical strategies: New dynamics for higher education throughout librarians’ vision”. Eighth International Conference on Higher Education Advances, 2022. https://doi.org/10.4995/HEAd22.2022.14476

- Scott, C. S., Schaad, D. C., Mandel, L. S., Brock, D. M., & Kim, S. (2000). Information and informatics literacy: Skills, timing, and estimates of competence. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 12(2), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328015TLM1202_5

- Shapiro, J. J., & Hughes, S. K. (1996). Information literacy as a liberal art. Enlightenment proposals for a new curriculum. Educom Review, 31(2), 1–6. https://teaching.charlotte.edu/sites/teaching.charlotte.edu/files/media/article-books/InformationLiteracy.pdf

- Smith Macklin, A. (2001). Integrating information literacy using problem-based learning. Reference Services Review, 29(4), 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000006493

- song, Y. S. (2004). International business students: A study on their use of electronic library services. Reference Services Review, 32(4), 367–373. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320410569716

- Wilson, T. D. (2006). On User Studies and Information Needs. Journal of Documentation, 62(6), 658–670. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410610714895

- Witherspoon, R., Taber, P., & Goudreau, A. (2022). Science students’ information literacy needs: A survey of science faculty on what and when each skill is needed. College and Research Libraries, 83(2), 296–313. https://doi.org/10.5860/CRL.83.2.296