Abstract

The spread of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has caused disruptions in the academic calendars of educational institutions. Globally, countries temporarily closed their schools as a measure to curb the spread of the virus. Students resorted to online lectures to continue their education. This article examined the challenges faced by college of education students during their online studies. Using a proportionate stratified random sampling procedure, students from the Seventh-day Adventist College of Education, Agona-Ashanti, were sampled for the study. A questionnaire was used as the instrument for data collection. Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS (version 25). The results show that slow internet speed, high cost of data, poor mobile network coverage and insufficient data were the major internet connectivity challenges students faced during the online studies. The Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests showed that gender and programme of study significantly influenced students’ participation in the online lectures (p˂.05) but the location (rural, urban and peri-urban) of the communities of students and level of education did not significantly impact students’ participation in the online lectures (p˃.05). A majority of the students perceived that COVID-19 negatively affected their studies. The government and telecommunication companies should work together to improve communication and internet services in the country to facilitate online studies.

Public Interest Statement

The spread of the novel coronavirus disease caused educational disruptions. This study examines the challenges faced by students of the Seventh-day Adventist College of Education in Ghana during the online studies caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The study is based on data gathered using stratified random sampling. The study was inspired by the need to contribute to the literature on COVID-19 by paying attention to the challenges students faced during the online studies, and comparing the experiences of students in different geographical divides (rural, urban and peri-urban areas) with regard to their satisfaction with the online studies. It was found that the major challenges students faced were slow internet speed, a high cost of data and poor mobile network coverage. A study of the issues can help the government and telecommunications companies collaborate to improve communication and internet services in the country, allowing for online studies.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has created the largest disruption of education systems in human history (Pokhrel & Chhetri, Citation2021), affecting higher education institutions both locally and globally (Godber & Atkins, Citation2021). In order to reduce the spread of the COVID-19, most countries around the world temporarily closed educational institutions while schools provided remote schooling through online lectures (Asio et al., Citation2021; Di Pietro et al., Citation2020; Saha et al., Citation2022). While shifting learning paradigms to online platforms has become the “new normal” for schools (Treve, Citation2021), several factors affect the quality of online learning and students’ knowledge and skills. These include access to technical infrastructure and the quality of the telecommunication network (Duraku & Hoxha, Citation2021). Online schooling exposes many insufficiencies and inequities in the education system. Among these challenges are the lack of access to broadband and computers required for online teaching and learning (Schleicher, Citation2020). The pandemic also compromised the ability of parents to finance school-related expenditures such as school kits and learning materials due to the associated economic implications (Duraku & Hoxha, Citation2021; Tuffour et al., Citation2021).

Treve (Citation2021) found that the key challenges to online studies during the spread of the Coronavirus disease included inadequate technical resources such as computers and quality mobile networks. Asio et al. (Citation2021) examined the electronic devices used by students for online classes and found that students mainly used smartphones during the schools’ closure. In addition to the electronic devices, Duraku and Hoxha (Citation2021) examined the modes of online lesson delivery, including the learning platforms used by teachers to teach students during the schools’ closure as well as the challenges students faced in using information and communication technology (ICT). Ranadewa et al. (Citation2021) upon review of 40 articles on the impact of COVID-19 on education reported that accessibility issues had an impact on learners’ satisfaction and commitment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to limited access to the internet, Owusu-Fordjour et al. (Citation2020) observed that students had difficulties with the e-learning platforms used by institutions for online lessons. These challenges negatively impacted online teaching and learning in Ghana. Aboagye et al. (Citation2021) examined the specific challenges tertiary education students faced during e-learning.

Earlier studies indicate that female students record higher class attendance than their male counterparts, with the differences being statistically significant (Kelly, Citation2012; Nja et al., Citation2019; Woodfield et al., Citation2006). Devadoss and Foltz (Citation1996) examined the factors that influence class attendance and performance. They observed that motivation, prior grade point average (GPA), self-financing by students, hours worked on jobs, quality of teaching, and the nature of class lectures, rather than course characteristics, influenced class attendance. Since different programmes of study entail different courses, it implies that the nature of the programme read by students may not have an influence on class attendance. Crosling et al. (Citation2009) observed that students do not progress in their education with the same level of interest and attendance. As they move up the educational ladder, their interests and involvement in academic activities change and some students may not continue with their studies. It therefore suggests that the level of education of students may have an impact on their involvement in academic activities. Reilly and Al-Samarrai (Citation2000) observed a significant difference in school attendance between rural and urban learners. Anazia (Citation2021) indicates that there is a disparity between rural and urban education, with many learners in rural areas not engaging in education or leaving school before developing literacy skills.

Townsend et al. (Citation2013) opined that rural areas are excluded from fast broadband developments partly due to technological and economic barriers in reaching more remote locations and a low level of willingness to adopt the technology where it is available. Blank et al. (Citation2017) indicate that the major geography-related divide with respect to internet access within a country is the urban–rural divide. Rural areas have lower broadband access and lower rates of internet use compared to their urban counterparts. According to Hiemstra and Poley (Citation2006), rural areas lag behind urban and peri-urban areas because of a lack of broadband opportunities. According to Belay (Citation2020), however, there are students pursuing undergraduate courses who come from rural areas that do not have internet access and electricity. Dome and Armah-Atto (Citation2020) observed that in rural Ghana, less than one-third of phone owners enjoy internet access via their phones, compared to 56% in cities. Students who resided in these areas for the online lectures during the schools’ closure thus faced peculiar challenges with internet connectivity. Other studies, however, indicate that though internet use by urban students is greater than their rural counterparts, both rural and urban students face the same problems with internet connectivity, with slight variations (Loan, Citation2011; Pawłowska et al., Citation2015).

Mohamad et al. (Citation2020) observed no significant difference in satisfaction with online distance learning among male and female students during the schools’ closure. Zhonggen and Ming (Citation2016) discovered no statistically significant gender differences in satisfaction with the clicker-aided flipped English as a Foreign Language class. In analyzing whether students were satisfied with their individual learning process, Hyun et al. (Citation2017) found that satisfaction was not statistically significantly related to gender or level of education.

This paper contributes to the literature on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on education in several ways. First, we contribute to the empirical literature which examines the challenges faced by students during online teaching and learning in the period of the schools’ closure. The study investigates the electronic devices and the learning platforms used by students for their online studies, the internet connectivity challenges they faced, the frequency of students in the online classes and students’ perception of the impact of the pandemic on their studies. Such a study is necessary to inform public policy on measures to strengthen the modes of online lectures in the event of future pandemics.

Second, the study was conducted to prove the relationship between sex, programme of study, students’ level of education and location of students (rural/urban/peri-urban), and students’ participation in the online lectures. It also analysed the relationship between the location of students and the frequency of internet connection disruptions. Besides, it explored students’ levels of satisfaction with the explanations, participation, understanding of topics discussed, and the quality of assignments in relation to their gender, location and level of education. In Ghana, the relationships among these variables have not been examined in details.

The study addressed the following research questions: What were the differences in students’ participation in online lectures based on gender? Did students’ programmes of study influence their participation in the online lectures? What was the influence of education level on students’ participation in the online lectures? How did the location of students influence their participation in the online lectures? Is there a relationship between the location of students and the frequency of internet connection disruptions experienced during online studies? Were there differences in students’ levels of satisfaction with the explanations of topics discussed in relation to their gender? Were there differences in students’ levels of satisfaction with their participation in the online lectures in relation to their gender? Did gender influence students’ levels of satisfaction with their understanding of the topics discussed during the online lectures? Did gender influence students’ levels of satisfaction with the quality of assignments given by tutors during the online lectures?

Other questions addressed were: Were there differences in students’ levels of satisfaction with the explanations of topics discussed in relation to their location? Were there differences in the students’ levels of satisfaction with their participation in the online lectures in relation to their location? Did location influence students’ levels of satisfaction with their understanding of the topics discussed during the online lectures? Did location influence students’ levels of satisfaction with the quality of assignments given by tutors? How did the level of education influence students’ levels of satisfaction with the explanations of topics discussed? Were there differences in students’ levels of satisfaction with their participation in the online lectures in relation to their level of education? Were there differences in students’ levels of satisfaction with the understanding of topics discussed in relation to their level of education? How did the level of education influence students’ levels of satisfaction with the quality of assignments given by tutors during the online lectures?

To answer our research questions, we analysed the types of electronic devices used by students for the online studies, the number of times students participated in the online lectures per week, the social media learning platforms used by students for the online lectures, and the strength of internet connectivity in the communities of students. We also examined the levels of students’ satisfaction with the explanation given by tutors, their participation in the online studies, their understanding of topics discussed and the quality of assignments given by tutors. This is to form the basis for recommendations for the formulation of national and governmental policies to provide ICT support to students for online studies during similar pandemic.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Setting

We collected data from levels 100 and 200 students in the Seventh-day Adventist College of Education located in the Sekyere South District Assembly in the Ashanti Region, Ghana. This study was part of a larger study that examined the impact of the COVID-19 on the academic performance of students in the Seventh-day Adventist College of Education. Since it was easier for the researchers to get access to the academic records of students at the college before and during the pandemic, the study focused on that college. The level 300 students were exempted from the study because they were the last batch of students who pursued courses under the Diploma in Basic Education programme. They completed college before the outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease. The colleges of education in Ghana follow an academic calendar of two semesters in a year. The first semester begins in October and ends in February, while the second semester starts in March and ends in June. In the first semester of the 2019/2020 academic year, levels 100 and 200 students had their usual face-to-face lectures and took their end-of-semester examinations before the coronavirus disease became more severe in the country.

On 28 March 2020, however, the Presidency of Ghana announced a lockdown on the Greater Accra Metropolitan and Greater Kumasi Metropolitan Assemblies. This formed part of the national measures to curtail the spread of the coronavirus disease. Students across the country stayed home due to the temporary closure of educational institutions. On April 20, 2020, the lockdown was lifted (Kenu et al., Citation2020). Level 200 students reported to school on August 31, 2020, took their end-of-second semester examination between September 16 and 29, 2020, and went on vacation. The level 100 students in turn reported to school on October 4, 2020 and took their end-of-second semester examination between October 19 and October 30, 2020. However, between April and the periods of examinations, students had their tuition online as they stayed at home.

The Seventh-day Adventist College of Education organizes two programmes for students: primary education and junior high school education. The level 100 primary education students read courses with a total credit hour of between 18 and 19, while the junior high school education students read courses with a total credit hour of 18. At level 200, the primary education students read courses with 20–21 credit hours, while the junior high school education students read courses with a total credit of 21–22. The credit hours influenced the number of times students participated in the online lectures. The situation of students at the two levels presents an opportunity to examine the challenges students faced in the course of online schooling.

2.2. Study design

The study adopted a cross-sectional study design. Using this design, data is collected at one time from a cross-section of the population (Honlah et al., Citation2019; Kumar, Citation2011). It is most suitable for examining the prevalence of a problem by taking a cross-section of the targeted population. The design provides a general “picture” of a problem as it stands at the time of a study (Kumar, Citation2011).

2.3. Sample selection

The study adopted a proportionate stratified random sampling procedure in the selection of the respondents. In this sampling procedure, the number of elements selected in the sample from each stratum is in relation to their proportion in the total population. Besides, the elements are selected using a random sampling procedure (Kumar, Citation2011). In the first stage, lists containing the names of all students in levels 100 and 200 during the 2019/2020 academic year were obtained from the college administration. The number of students on the two lists was 406. Dillman (Citation2000) was used to calculate sample size:

n = [(N) (p) (1 − p)]/[(N − 1) (B/C) 2 + (p) (1 − p)]

Where n is the sample size required for the desired level of precision, N is the students’ population, p is the percentage of the population with the desired characteristics, preferably 50% or.5, B is the accepted sampling error, or precision (.5 or 5%), and C is the Z statistic associated with the confidence level, which is 1.96, that corresponds to a 95% confidence level (Dillman, Citation2000; Oribhabor & Anyanwu, Citation2019; Taherdoost, Citation2017). Thus,

N = 406, p = 0.5, B = 0.05 (5%), C = 1.96

n = [(406) (0.5) (1–0.5)]/[(406–1) (0.05/1.96)2 + (0.5) (1–0.5)]

n = 198

Therefore a sample of 198 was used for this study (Table ).

Table 1. Level of students and the respective numbers in their gender groupings

In the second stage, levels 100 and 200 were considered two strata. In order to ensure proportional representation in the selection of samples from the two levels, the proportionate sampling procedure was adopted. It is expressed as SL = TS x NS/P, where SL is the sample size per level, TS is the total sample size, NS is the number of students per level and P is the population of students at the two levels. The proportionate sampling method was also used to select the sample of students from each gender group. It is expressed as SS = TS x NS/TL, where SS is the sample size per sex to be selected, TS is the total number of students in a sex group in a level, NS is the number of students proportionally selected in a level and TL is the total number of students at a particular level. The aim was to ensure fair representation of gender groups for the comparison of findings.

Following the calculations of the sample size and the proportional samples selected from each level and gender group, the fishbowl draw was used to select 198 students from the two lists. In the first stage, the fishbowl draw (Kumar, Citation2011) was conducted for level 100 students. In the process, we made sure 59 males and 43 females had been selected. In the second stage, the process was used to select 96 students from the list of 196 students in level 200. At this stage, we made sure 65 males and 31 females were selected. The selected students were contacted on campus for questionnaire administration.

2.4. Survey instruments

The study used questionnaires for data collection. The questionnaire inquired about demographic information of students, including gender, level of education, programme of study and location of community. It also inquired into the strength of internet connections in their communities and their level of satisfaction with online teaching and learning activities. All the participants that were sampled completed the survey. The study, thus, achieved a 100% response rate.

2.5. Definition and measurement of variables

Demographic variables included in the analysis were gender coded as (male = 1, female = 2) and location (rural = 1, urban = 2, peri-urban = 3). We dichotomized the level of education of students (level 100 = 1, level 200 = 2). The strength of internet connectivity was determined by the following item: “In general, how would you rate the strength of internet connectivity in your community?” This was assessed via a 3-point scale ranging from 1 = weak, 2 = average to 3 = strong. The frequency of internet connection disruptions in the communities of students was determined by the following item: “How frequent were internet connection disruptions in your community?” The responses to the item were given on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 = never, 2 = very rarely, 3 = rarely, 4 = occasionally, 5 = frequently, and 6 = very frequently, which were later recoded into lower (never, very rarely, rarely and occasionally) = 1 and higher internet connection disruptions (frequently and very frequently) = 2. We collapsed the responses because of the relatively low records of never, very rarely, and rarely in the sample. The satisfaction of students in the online lectures was determined by the question: “How satisfied were you with the level of explanation given by tutors, your participation in the online lectures, your understanding of topics discussed and the quality of assignments given by tutors?” The responses to the four items were given on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = moderately dissatisfied, 2 = slightly dissatisfied, 3 = slightly satisfied, 4 = moderately satisfied, to 5 = highly satisfied. These were later recoded into dissatisfied = (moderately dissatisfied and slightly dissatisfied) = 1 and satisfied (slightly satisfied, moderately satisfied, and highly satisfied) = 2.

3. Statistical analysis

We analysed the influence of gender, programme of study and level of education on students’ participation in the online lectures using the Mann-Whitney test. The influence of a student’s location on their participation in lectures was tested using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The influence of the location of students and the frequency of internet connection disruptions was tested using the Kruskal-Wallis test. A Mann-Whitney test was also performed to determine the influence of gender and level of education on students’ satisfaction in the online studies, while a Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to ascertain the influence of location on satisfaction. The Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests were conducted because the dependent variables, namely, frequency of participation in lectures, frequency of internet connection disruptions, and students’ satisfaction in the online studies, were measured at the ordinal level (Ofori & Dampson, Citation2011). The influence of gender, programme of study, and level of education on students’ participation in the online lectures was determined using the Mann-Whitney test because gender, programme of study, and level of education, as independent variables, have two categories each. On the other hand, the influence of students’ location on their participation in lectures was tested using the Kruskal-Wallis test because location as an independent variable has three attributes (Ofori & Dampson, Citation2011; Weaver et al., Citation2017). The tests were performed at a 95% confidence interval. We performed the analyses using IBM SPSS (version 25.0).

4. Ethical considerations

We obtained written permission from the college authorities for data on students to be used for the study. The study was also approved by the Committee on Human Research, Publications and Ethics at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, School of Medical Sciences, Kumasi, Ghana (Ref: CHRE/AP/297/21). Besides, study participants were fully briefed on the research after which their verbal consent was obtained before questionnaire administration.

5. Results

5.1. Sample characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the students are presented in Table . The majority of the students were males 124 (62.6%), lived in urban areas 124 (62.6%) and were level 100 students 102 (51.5%).

Table 2. Number of times student participated in online lectures in a week (N = 198)

5.2. Electronic devices used by students for online lectures

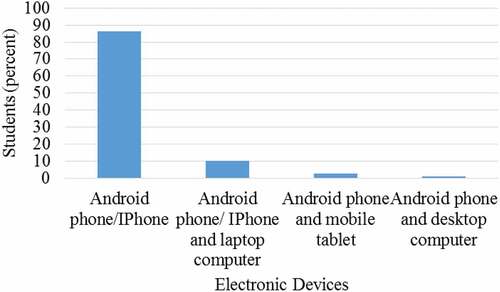

The majority of the students used Android phones or iPhones to participate in the online lectures (Figure ). The results show that the use of laptop computers and mobile tablets, in addition to Androids or iPhones, among students was low. Only two (1%) of the students used desktop computers in addition to their Android phones.

5.3 The impact of gender, programme of study and level of education on students’ participation in online lectures

The results show a low level of students’ attendance in the online lectures. The majority of students participated in the online lectures within the ranges of 1 to 4 and 5 to 8 times per week (Table ). Only 3 (1.5%) participated in the online lectures within the range of 17 to 21 times. The results show that the gender of students significantly influenced their attendance at online lectures, with female students participating more frequently per week (p˂.05). Besides, students’ programme of study significantly influenced their participation such that primary education students joined the lectures more frequently than the junior high school education students (p˂.05). However, level of education and location of communities did not significantly influence students’ participation in the online lectures (p˃.05). Thus, both level 100 and level 200 students participated in the online lectures at the same frequency. Besides, students from rural, urban and peri-urban areas participated in the online lectures at the same frequency.

5.3. Learning platforms used for online studies

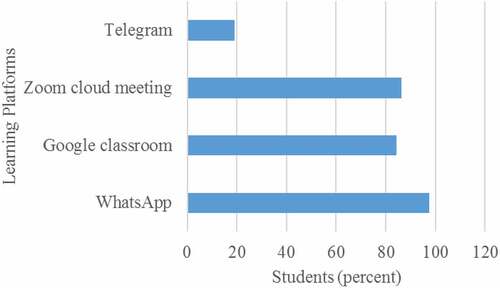

The majority of the students used WhatsApp, Zoom cloud meeting and Google Classroom for their online lectures (Figure ). Students mostly combined these learning platforms for the lectures. The results show that 38 (19.2%) of the students used Telegram in addition to the first three social media platforms. The use of only one or two platforms for online studies was relatively low.

5.4. Strength of internet connectivity in the communities of students

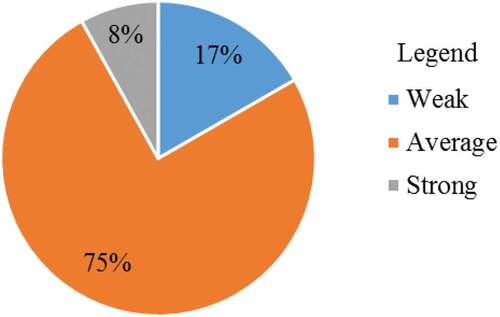

The majority of the students rated the strength of the internet connectivity in their locations as average (Figure ). Only 16 (8%) rated the strength of internet as strong. About one-sixth of the students considered the strength of the internet in their locations as weak.

5.5. Internet connectivity challenges faced by students

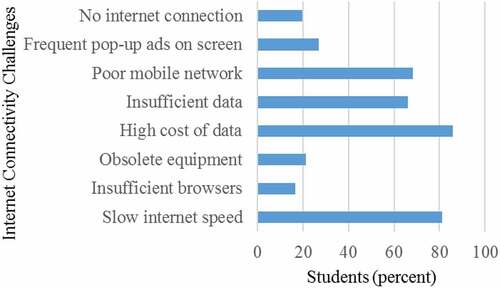

The main internet connection challenges experienced by the majority of the students were the high cost of data, slow internet speed, poor mobile network, and insufficient data (Figure ). The results show that 53 (26.8%) of the students had frequent pop-up ads on the screens of their electronic devices, while 42 (21.2%) and 33 (16.7%) reported having obsolete mobile equipment and insufficient browsers, respectively. Besides, 39 (19.7%) reported instances where they had no internet connection.

5.6. Location of communities and frequency of internet disruptions

A larger proportion of students from rural communities experienced a higher frequency of internet connection disruptions than their urban and peri-urban counterparts (Table ). The results, however, show that the differences were not statistically significant (p˃0.05). Thus, the frequencies of internet connection disruptions experienced by students from rural, urban and peri-urban communities were similar.

Table 3. Location of communities and frequency of internet connection disruptions

5.7. Satisfaction levels of students

Table indicates that gender, location of community, and level of education did not statistically significantly influence students’ satisfaction with the level of explanation given by tutors during the online lectures (p˃0.05). The results show no statistically significant differences in the satisfaction of students with the levels of participation in the online lectures, their understanding of the topics, and the quality of assignments in relation to their gender (p˃0.05). The location of students did not significantly influence their satisfaction with the levels of participation in the online lectures (p˃0.05) as well as their understanding of the topics and the quality of assignments given by tutors during the online lectures (p˃0.05). Besides, the results show no statistically significant differences in the satisfaction of students with the levels of participation in the online lectures, their understanding of the topics, and the quality of assignments in relation to their levels of education (p˃0.05).

Table 4. Satisfaction levels of students in relation to gender, location of community and level of education

5.8. The impact of COVID-19 on studies

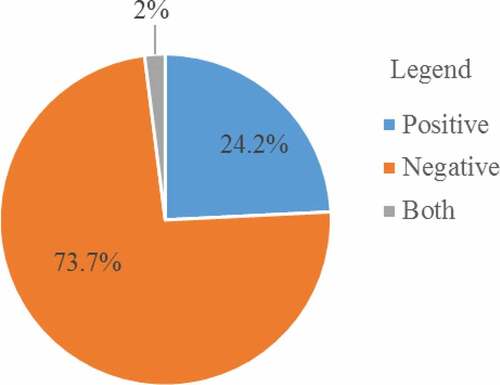

The majority of the students perceived that COVID-19 had a negative impact on their studies (Figure ). This stemmed from the poor mobile networks and slow internet speed that hindered effective online studies. On the other hand, 48 (24.2%) of the students reported that the impact of COVID-19 on their studies was positive. This was because online studies gave students the opportunity to acquire skills in the use of the internet and online learning platforms. However, a smaller proportion of the students considered the effect of the pandemic to be both positive and negative.

6. Discussions

The COVID-19 pandemic caused disruptions in the academic calendars of educational institutions (Godber & Atkins, Citation2021; Pokhrel & Chhetri, Citation2021). In order to control the pandemic, countries temporarily closed their schools and resorted to online schooling (Di Pietro et al., Citation2020). Many countries conducted online studies for students (Treve, Citation2021), but the practice was fraught with difficulties (Duraku & Hoxha, Citation2021). The main objective of this survey was to examine the electronic devices Seventh-day Adventist College of Education students used for their online studies and the specific challenges they faced during the studies. It also analysed the relationship between the locations of students and the frequency of internet connectivity challenges they experienced. The study analysed the effects of gender, location and level of education on students’ satisfaction with the level of explanation given by tutors, individual students’ participation, the level of understanding of topics discussed and the quality of assignments given by tutors.

The findings show that majority of the students used Android and iPhones to connect to the internet for their online lectures. However, mobile tablets and desktop computers, in addition to Android phones, had limited applications. The findings are consistent with Duraku and Hoxha (Citation2021), who observed that the electronic devices used by learners for online studies in the period of the schools’ closure were phones, iPads, computers, or laptops. Asio et al. (Citation2021) also observed that an appreciable number of college computer students used smartphones (94%) for their online studies during the schools’ closure. However, only a few students used laptops (23%), tablets (1%) and personal computers (4%). This situation was not significantly different from students at the other colleges where they studied. According to the current study, college students frequently use Android and iPhone devices, and they rely on them for academic activities when the occasion arises.

The results of the survey show that the gender of students significantly influenced their attendance at the online lectures. Female students participated more frequently in the online lessons per week compared to their male counterparts. Nja et al. (Citation2019) discovered that the mean score of the female students’ class attendance was 83.76, which was greater than that of the males (67.2). The results of the current survey also confirm the results of other earlier studies that found female students have higher class attendance than males (Kelly, Citation2012; Woodfield et al., Citation2006). However, the survey contradicts the findings of Devadoss and Foltz (Citation1996) that the course characteristics of students do not influence their class attendance. This study suggests that students will participate in lectures at different rates based on the nature of their programmes.

This survey found that level of education and location of communities did not statistically significantly influence students’ attendance in the online lectures. It thus contradicts the observation of Crosling et al. (Citation2009) that students lose interest in academic activities as they move to higher levels of education. Besides, the findings of this survey contradict the observation of Al-Samarrai and Reilly (Citation2000) that significant differences in class attendance exist between rural and urban learners. However, while Al-Samarrai and Reilly (Citation2000) focused on traditional classroom attendance, the current study focused on online studies. Thus, the current survey shows that students’ participation in online studies is not influenced by where they live.

Our results show that students mostly combined three learning platforms—WhatsApp, Zoom cloud meeting and Google classroom—for their online studies. In addition, students used Telegram for their online studies. The study suggests that WhatsApp, Zoom cloud meeting and Google classroom were central to students’ participation in the online studies. Earlier studies discovered that teachers interacted with students using Zoom cloud meeting, Google meet, Skype, Google classroom, Viber, WhatsApp, Microsoft teams and Vov meeting (Duraku & Hoxha, Citation2021; Saha et al., Citation2022). While students in the current survey used Telegram in addition to other platforms, they did not use Skype, Viber, Google meet, Microsoft teams and Vov meeting. In the current survey, these learning platforms were not common with students. The study is however consistent with Mahyoob (Citation2020) who observed that students mostly used WhatsApp (72.2%) for their online studies. However, the uses of Zoom (33.5%), and Google and Microsoft platforms (24%) were limited.

The results of the current study show that the majority of the students rated the strength of internet connectivity in their communities as average. The major internet connectivity challenges students faced in connecting to the internet were the high cost of data, slow internet speed, poor mobile communication network and insufficient data. Mahyoob (Citation2020) observed that slow internet speed was the major problem that students faced during online classes. Ranadewa et al. (Citation2021) discovered that, among other factors, accessibility issues impacted significantly on learners’ satisfaction during the online studies. The findings also confirm the results of Aboagye et al. (Citation2021), who observed high cost of internet data, with a mean of 4.8 and poor internet access (4.49) among the challenges students faced during online studies. The high cost of data and poor internet access are, therefore, recognised by students as obstacles to internet access.

Our findings show that there were no statistically significant differences in the frequency of internet connection disruptions reported by students from rural, urban and peri-urban areas. This was in spite of the view expressed by earlier studies with respect to the disparity between rural and urban areas in internet connections (Blank et al., Citation2017; Hiemstra & Poley, Citation2006). The current study thus confirms the report of Loan (Citation2011) that both rural and urban students face similar challenges with internet connectivity. This study suggests that students experience similar levels of internet connection disruptions irrespective of their locations.

The findings of the survey indicate that gender, location of community, and level of education did not significantly impact students’ satisfaction with the level of explanation given by tutors during the online lectures. In addition, there were no statistically significant differences in the satisfaction of students with the levels of participation in the online lectures, their understanding of the topics and the quality of assignments in relation to their gender, location and levels of education. The findings are consistent with Mohamad et al. (Citation2020), who found no statistically significant differences in the satisfaction of male and female students during the online studies in the period of the schools’ closure. It also confirms Zhonggen and Ming (Citation2016), who found no statistically significant gender differences in satisfaction with the clicker-aided flipped English as a Foreign Language class. In spite of the widely held view that internet connectivity is stronger in urban areas (Belay, Citation2020; Pawłowska et al., Citation2015), compared to rural areas, residing in rural, urban or peri-urban areas did not influence students’ satisfaction during the online lectures. This survey also confirms the finding by Hyun et al. (Citation2017) that students’ satisfaction is not significantly related to their level of education.

The current study suggests that both male and female students had similar levels of satisfaction with the explanations given by tutors during the online studies. Besides, students in rural, urban, and peri-urban areas experienced similar levels of satisfaction with the explanations given by tutors. Moreover, both level 100 and level 200 students had similar levels of satisfaction with the explanations given by tutors. The current study also suggests that both male and female students had similar levels of satisfaction with their participation in the online studies. Besides, students in rural, urban, and peri-urban areas experienced similar levels of satisfaction with their participation in the online lectures. In addition, both level 100 and level 200 students had similar levels of satisfaction with participation.

The majority of the students in this survey perceived that the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on their studies. On the other hand, 48 (24.2%) of the students indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic had a positive impact on their studies. This confirms the findings of Al Rawashdeh et al. (Citation2021) that the use of computers for online studies raises the level of students’ culture and skills in spite of the disadvantages. The results of this survey suggest that the pandemic had both advantages and disadvantages for students. The face-to-face lectures provided more effective participation in classroom activities and understanding of the courses than the online mode of teaching. The various internet connectivity challenges students faced impeded effective online studies. However, the adoption of the online mode of teaching enhanced the skills of the students in the use of the internet and various ICT tools and built their capacity to do research.

7. Conclusions

We found that students mostly used Android and iPhones for the online lectures. Female students participated in the online lectures more frequently than male students. Primary education students also joined the online lectures more frequently than the junior high school education students. Students mostly combined WhatsApp, Zoom cloud meeting and Google classroom for their academic work during the school closure. Students faced major internet connectivity challenges such as high data costs, slow internet speed, and a poor mobile network. The location of students did not significantly influence the frequency of internet connection disruptions. Besides, gender, location and level of education did not significantly influence students’ satisfaction in the online studies. Measures should be taken by the college authorities to encourage male students to participate frequently in teaching and learning activities during similar future events. This could be achieved through guidance and counselling. Measures should be put in place by college authorities to provide data at an affordable cost to students during similar pandemics in the future. College authorities should invest in educating students on the use of WhatsApp, Zoom cloud meeting and Google classroom to advance the use of these learning platforms among students since they mostly rely on them for online studies. The government and telecommunication companies should work together to improve communication and internet services in the country to facilitate online studies. The government, through the Ministry of Education, should increase college students’ access to Android and iPhones to enable students to connect to the internet for online studies in the event of any future occurrences that will obstruct the academic calendar.

8. Limitations

This study was conducted in only one college of education in Ghana, where the authors easily got access to students’ academic records for the larger research that assessed the impact of the COVID-19 on students. For the purpose of generalising about colleges of education in Ghana, a larger study that includes more colleges is recommended.

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the efforts of Andra Marfo, our research assistant, throughout the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Peter Ofori Atakorah

Peter Ofori Atakorah holds a Bachelor of Education in Arts (University of Cape Coast), a Master of Educational Administration (University of Cape Coast), and a Doctor of Philosophy in Education (Texila American University, Guyana, South America). His research areas are educational leadership and the effects of invasive species on education. He is particularly interested in the challenges students faced during the online studies instigated by the COVID-19 pandemic. How COVID-19 affects the academic performance of colleges of education and the economic impact of the pandemic on students are also studied. This study forms part of a larger research project that examines the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the academic performance of students at the Seventh-day Adventist College of Education, Agona-Ashanti, Ghana.

Emmanuel Honlah

References

- Aboagye, E., Yawson, J. A., & Appiah, K. N. (2021). COVID-19 and e-learning: The challenges of students in a tertiary institution. Social Education Research, 2(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.37256/ser.212021422

- Al Rawashdeh, A. Z., Mohammed, E. Y., Al Arab, Alara, M., Al-Rawashdeh, B., Al-Rawashdeh, B., & Al-Rawashdeh, B. (2021). Advantages and disadvantages of using e-learning in university education: Analyzing students’ perspectives. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 19(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.34190/ejel.19.3.2168

- Al-Samarrai, S., & Reilly, B. (2000). Urban and rural differences in primary school attendance: An empirical study for Tanzania. Journal of African Economies, 9(4), 430–474. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/9.4.430

- Anazia, I. U. (2021). Closing the school attendance gap in rural communities in Nigeria: School leadership and multi-actor approach in community engagement. International Modern Perspectives on Academia and Community Today. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.36949/impact.v1i1.37

- Asio, J. M. R., Gadia, E. D., Abarintos, E. C., Paguio, D. P., & Balce, M. (2021). Internet connection and learning device availability of college students: Basis for institutionalizing flexible learning in the new normal. Studies in Humanities and Education, 2(1), 56–69. https://doi.org/10.48185/she.v2i1.224

- Belay, D. G. (2020). COVID-19, distance learning and educational inequality in Rural Ethiopia. Pedagogical Research, 5(4), em0082. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/9133

- Blank, G., Graham, M., & Calvino, C. (2017). Local Geographies of Digital Inequality. Social Science Computer Review, 36(1), 82–102. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0894439317693332

- Crosling, G., Heagney, M., & Thomas, L. (2009). Improving student retention in higher education. Australian Universities’ Review, 51(2), 9–18. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ864028

- Devadoss, S., & Foltz, J. (1996). Evaluation of Factors Influencing Student Class Attendance and Performance. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 78(3), 499–507. https://doi.org/10.2307/1243268

- Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method. Wiley.

- Di Pietro, G., Biagi, F., Costa, P., Karpiński, Z., & Mazza, J. (2020, December 30). The likely impact of COVID-19 on education: Reflections based on the existing literature and international datasets. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC121071

- Dome, M. Z., & Armah-Atto, D. (2020). Ghana’s e-learning program during pandemic presents access challenges for many students. Afrobarometer Dispatch, 374. https://afrobarometer.org.›.publications.›.ad374-ghana

- Duraku, Z. H., & Hoxha, L. (2021, December 30). The impact of COVID-19 on education and on the wellbeing of teachers, parents, and students: Challenges related to remote (online) learning and opportunities for advancing the quality of education.https://www.researchgate.net.›.publication.›.341297812

- Godber, K. A., & Atkins, D. R. (2021). Impacts on teaching and learning: A collaborative autoethnography by two higher education lecturers. Frontiers in Education, 6, 1–14. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/feduc.2021.647524

- Hiemstra, R., & Poley, J. (2006). Rural internet use via broadband connections: Real challenges for lifelong learning. PAACE Journal of Lifelong Learning, 15, 85–101. https://www.iup.edu.›.programs.›.hiemstra-poley2006

- Honlah, E., Segbefia, A. Y., Appiah, D. O., Mensah, M., & Yildiz, F. (2019). The effects of water hyacinth invasion on smallholder farming along River Tano and Tano Lagoon, Ghana. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 5(1), 1567042. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1567042

- Hyun, J., Ediger, R., & Lee, D. (2017). Students’ satisfaction on their learning process in active learning and traditional classrooms. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 29(1), 108–118. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1135821

- Kelly, G. (2012). Lecture attendance rates at university and related factors. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 36(1), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2011.596196

- Kenu, E., Frimpong, J. A., & Koram, K. A. (2020). Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal, 54(2), 72–73. https://doi.org/10.4314/gmj.v54i2.1

- Kumar, R. (2011). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners ((3rd) ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Loan, F. A. (2011). Internet use by rural and urban college students: A comparative study. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 31(6), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.14429/djlit.31.6.1317

- Mahyoob, M. (2020). Challenges of e-Learning during the COVID-19 PandemicExperienced by EFL learners. Arab World English Journal, 11(4), 351–362. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol11no4.23

- Mohamad, S. A., Hashim, H., Azer, I., Hamzah, H. C., & Khalid, R. A. H. (2020). Gender differences in students’ satisfaction and intention to the continuation of online distance learning. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(9), 641–650. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i9/7855

- Nja, C., Cornelius-Ukpepi, B., & Ihejiamaizu, C. C. (2019). The influence of age and gender on class attendance plus the academic achievement of undergraduate chemistry education students at university of calabar. Educational Research and Review, 14(18), 661–667. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2019.3805

- Ofori, R., & Dampson, D. G. (2011). Research methods and statistics using SPSS. Payless Publication Limited.

- Oribhabor, C. B., & Anyanwu, C. A. (2019). Research sampling and sample size determination: A practical application. Federal University Dustin-Ma Journal of Educational Research, 2(1), 47–56. https://www.researchgate.net.›.publication.›.links

- Owusu-Fordjour, C., Koomson, C. K., & Hanson, D. (2020). The impact of covid-19 on learning - the perspective of the Ghanaian student. European Journal of Education Studies, 7(3), 88–101. https://oapub.org/edu/index.php/ejes/article/view/3000/5638

- Pawłowska, B., Zygo, M., Potembska, E., Kapka-Skrzypczak, L., Dreher, P., & Kędzierski, Z. (2015). Prevalence of internet addiction and risk of developing addiction as exemplified by a group of polish adolescents from urban and rural areas. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine: AAEM, 22(1), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.5604/12321966.1141382

- Pokhrel, S., & Chhetri, R. (2021). A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Education for the Future, 8(1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631120983481

- Ranadewa, D. U. N., Gregory, T. Y., Boralugoda, D. N., Silva, J. A. H. T., & Jayasuriya, N. A. (2021). Learners’ satisfaction and commitment towards online learning during COVID-19: A concept paper. Vision. 0(0), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/09722629211056705

- Reilly, B., & Al-Samarrai, S. (2000). Urban and Rural differences in primary school attendance: An empirical study for Tanzania. Journal of African Economies, 9(4), 430–474. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/9.4.430

- Saha, S. M., Pranty, S. A., Rana, M. J., Islam, M. J., & Hossain, M. E. (2022). Teaching during a pandemic: Do university teachers prefer online teaching? Heliyon, 8(e08663), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08663

- Schleicher, A. (2020). the impact of covid-19 on education: Insights from education at a glance. https://www.oecd.org.›.education.›.the-impact-of.on.5th,May,2021

- Taherdoost, H. (2017). Determining sample size; how to calculate survey sample size. International Journal of Economics and Management Systems, 2, 237–239. https://www.researchgate.net.›.publication.›.322887480

- Townsend, L., Sathiaseelan, A., Fairhurst, G., & Wallace, C. (2013). Enhanced broadband access as a solution to the social and economic problems of the rural digital divide. Local Economy, 28(6), 580–595. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094213496974

- Treve, M. (2021). What COVID-19 has introduced into education: Challenges facing Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). Higher Education Pedagogies, 6(1), 212–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2021.1951616

- Tuffour, A. D., Cobbinah, S. E., Benjamin, B., & Otibua, F. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education sector in Ghana: Learner challenges and mitigations. Research Journal in Comparative Education, 2(1), 20–31. https://royalliteglobal.com/rjce/article/view/625

- Weaver, K., Morales, V., Dunn, S. L., Godde, K., & Weaver, P. (2017). An introduction to statistical analysis in research: With applications in the biological and life sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Woodfield, R., Jessop, D., & McMillan, L. (2006). Gender differences in undergraduate attendance rates. Studies in Higher Education, 31(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500340127

- Zhonggen, Y., & Ming, L. (2016, April 16-17). Gender differences in satisfaction and academic achievements in the clicker-aided flipped EFL class [ Paper presentation]. International conference on education and development (ICED), Nanjing, Jiangsu, China