Abstract

Secondary schools of Georgia continue to be dominated by teacher-oriented models, which are insufficient to raise citizens who are active, informed and responsible. The process of multifaceted development of each student requires the use student-oriented pedagogy that focuses on developing the competencies for their active participation. The data collected from target group (374 teachers) by questionnaires were processed by statistical software package R. More than 120 variables were used in the study. The correlation matrix with polychoric correlation coefficients was used to select the variables participating in the analysis. The research revealed a positive correlation between the systematic, purposeful and confident application of the practice of collaborative teaching approach and strategies by Georgian school teachers and the development of civic competencies in students. Particularly, collaborative teaching reinforces in students: (a) affiliation to school, their integration and perception of themselves as members of the school community; (b) acceptance of different groups and cultures, respect for and observance of different views; (c) reduction of racism, chauvinism, and religious intolerance and development of a tolerant attitude; and (d) autonomy and self-organization, formation of a positive attitude towards the learning process. The collaborative learning process promotes both the democratic culture of the school and the social and civic competency of the students.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Georgia’s secondary schools are still mostly focused on teacher-oriented strategies, which fall short of creating knowledgeable, involved, and accountable citizens. The multifaceted development of students demands for the teacher to learn new information, employ interactive, modern teaching methods, and student-centered pedagogy that promotes the growth of critical thinking and active participation in processes.

The findings of the current study showed how collaborative teaching-learning approaches can be applied deliberately, systematically, and decisively to foster the development of citizenship competence and a democratic school culture. By incorporating collaborative teaching/learning strategies into the curriculum and integrating civic education’s theoretical component with practical applications, the development of the students’ citizenship competencies and school’s democratic culture is encouragedFootnote1. The study’s conclusions are presented as suggestions for action at the individual, institutional, and national levels.

In post-Soviet Georgia, a democratic society is forming, and education is given top emphasis in raising future democratic-minded generations. Change is challenging and painful in education, which for decades has been focused on producing young people who are inert, merely following directions, not thinking and active.

The National Curriculum, one of Georgia’s fundamental general education documents, has undergone three generations. The article looks at the efforts that have been made in each edition to promote democratic citizenship. Although the most recent, third edition of this document (2018–2024) offers all the prerequisites for educating an active citizen, there are still a number of significant issues that need to be resolved.

First and foremost, this is due to the teachers’ inability to implement the National Curriculum’s conditions in a school setting. At the same time, a significant number of educators do not view student civic competency development as a cross-curricular competence and an essential component of their work. The school culture is still a concern because it frequently repeats the experience of centralized, directive management from the past and hampers the development of democratic communication among the members of school community.

Based on the foregoing, the study was aimed to find out whether teachers employ cooperative teaching/learning strategies as a means of fostering a democratic school culture and a student-centered approach, and how this influences students’ civic competences and the development of a democratic school climate.

According to a three-year study by the authors, using student-centered cooperative teaching/learning strategies and developing civic competence as a cross-curricular competence as envisioned by the Georgian National curriculum supports both—the growth of democratic school culture and students’ civic competences.

1. Theoretical foundations of education for democratic citizenship

1.1. The essence of civic education

The goal of education for democratic citizenship is to familiarize students with the dynamic, interdependent, and diverse environment in which they live. It aids in the development of responsible, engaged youth. As a result, it is an ongoing action that serves as the foundation for democratic citizenship starting at a young age and continues throughout one’s entire life through formal or informal education.

Education for democratic citizenship remains a major topic in educational policy today, according to a survey of contemporary scientific literature. Theorists and education policymakers interpret and assess its objectives, principles, and approaches differently, but they all agree that democratic citizenship is characterized by knowledge, abilities, and experience behaving democratically (Abdi & Richardson, Citation2008; Apple & Beane, Citation2007; Seyla, Citation2002; Osler & Starkey, Citation2010).

Knowledge of the issues of democracy and the mechanisms of its functioning is not enough for teaching civic competencies to students and their further strengthening. It is also necessary to have a complex and multi-perspective educational system based on specific goals and relevant methodology, which causes the democratic transformation of society through citizen involvement (Banks, Citation2002); (Giroux, Citation2004). In the context of general education, education for democratic citizenship aims at bringing about a creative perception and thorough study of the environment where each student is recognized and valued as the most important member of the school community. Through the practice of democratic citizenship, students are involved in public life and activities from the outset that are based on and, at the same time, create new democratic experiences for students (Young, Citation2006)

School, which directly rears young people, forms and equips them with the 21st century skills, is the primary basic institution where the goals of democratic education are achieved. It has an obligation to teach children to live, act, think and, in general, function in the society according to democratic principles and rules of conduct (Dewey, Citation2008). Schools can and must play an important role in stimulating the growth of civic activism. Schools should implement all the above-mentioned by helping students develop and apply in practice the knowledge, beliefs and behavioral norms necessary to participate in the civic life. Schools can also provide opportunities for civic engagement; they can connect young people and other members of the community (Vegas & Winthrop, Citation2020).

Civic Education takes care of the development of good citizens. In a democracy, good citizens actively participate in public life through engaging in the civic and political activities. They can find a balance between the welfare of the community and their own interests, they actively contribute to the formation of a democratic society (UNESCO, Citation2014) It is also important to develop a dialogue between students of different cultures, faiths and religions, which necessarily requires an emphasis on civic education issues, as such education can make a significant contribution to the formation of a sustainable and tolerant society (Council of Europe, Citation2020).

According to modern studies, it is necessary for democratic citizenship that students, as active members of a democratic society, realize their public role and function (Apple & Beane, Citation2007; Dewey, Citation2008). It is formally originated from school that is not a neutral space. Democratic citizenship is not achieved at school by itself, so school community should make every effort to develop democratic opportunities in students through systematic teaching and practice (Bîrzea, Citation2005); (Anyon, Citation2008); (Freire & Macedo, Citation1987); (Maher & Tetreault, Citation2001); (McLaren & Jaramillo, Citation2006).

The goals of education for democratic citizenship may be considered in the context of students’ cognitive and ethical development, which includes: (a) lessons whose content and teaching methodology are related to the competencies of democratic citizenship; (b) individual situations of the learning process that facilitate the revelation/development of students’ civic thinking and/or action; (c) the daily life of school, where any school activities are implemented by school as a social institution (Albulescu & Albulescu, Citation2015).

Democratic competencies, as an important component of Citizenship Education, are reflected in both the formal curriculum through explicit teaching and in the covert curriculum—in rules of conduct, school mission and classroom interactions (Subba, Citation2014).

Studies conducted in Georgia—(Chargeishvili, Citation2019; Gorgadze, Citation2018); (Civic Education Lecturers Association—CELA, Citation2017; Malazonia et al., Citation2021)—confirm the importance of civic education on issues such as attitude towards the different, respect for justice and law, human rights, reducing the threat of radicalization, civic activism, etc.

The goals mentioned in the Constitution of Georgia (Government of Georgia, Citation1995) and in the National Goals of General Education (Government of Georgia, Citation2004) can be achieved only with the unity of citizens with active and thought out responsibilities, which is based on civic education.

1.2. Civic education in the national curriculum

For Georgia, as a state in transition to a democratic system of government, it is important to study and take into consideration the experience and achievements of the leading democracies of the West in the introduction of civic education.

When analyzing foreign curriculaFootnote2 there were identified three main strategies for developing curricula for education for democratic citizenship: (1) teaching as a separate course, (2) including certain topics in separate subject curricula, and (3) cross-curricular approach to teaching all subjects.

Teaching of democratic citizenship in Georgia is based on several key documents—the National Goals for General Education (Government of Georgia, Citation2004) and the National Curriculum (Ministry of Education and science of Georgia, Citation2018–2024). The textbook of any subject is based on these documents and the teacher is also guided by these documents while teaching. Therefore, it is important to analyze the curriculum as a key guidance document for teachers.

In Georgia, at the different stages of education reform, the range and opportunities for achieving the goals of civic education in the National Curriculum have been significantly expanded. At the first stage (Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia, Citation2011–2016), the responsibility for achieving the goals stated in the education policy documents in the field of civic education was mainly assigned to civic education as an independent subject. In the second edition of the National Curriculum, civic education appears to be a cross-curricular competence in general education, however, only in the results to be achieved by the subject standards of the social sciences: Social and Civic Competences mean the development of those necessary skills and values in respond to civic life, such as: constructive partnership, problem-solving, critical and creative thinking, decision-making, tolerance, respecting other’s rights, recognition of democratic principles, etc. (Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia, Citation2011–2016).

The development of civic competencies in the third edition of the National Curriculum (Ministry of Education and science of Georgia, Citation2018–2024) was reflected in the results to be achieved by all disciplines, which include the student’s perception of themselves as a full-fledged member of society, caring for the country, teaching forms of civic participation, willingness and ability to implement positive changes, development of the skills and values needed for the citizen, mastering the principles of the rule of law and democracy (Ministry of Education and science of Georgia, Citation2018–2024).

On the other hand, independent subjects in the field of citizenship were maintained: Society and Me—at the primary level (grades III–IV); Citizenship—at basic and secondary levels (grades VII–XI).

Citizenship is also taught in an integrated way with the subjects included in the block of social sciences—History of Georgia, Study of Local Lore and Geography, in the subject—Our Georgia (grades V–VI).

Citizenship is taught at the primary level in the following areas: personal development, initiative and entrepreneurship, socio-cultural development, citizenship and security.

As for the basic and secondary levels, teaching areas are: personal development and socialization, initiative and entrepreneurship, civic participation and security.

Overall, the new curriculum has provided more opportunities for a sharp emphasis on democratic citizenship issues. For example, strengthening human rights, European and global citizenship issues are the most visible content and practical aspects of the new curriculum, making it radically different from the old curricula.

Thus, the Georgian National Curriculum combines all three models of developing a curriculum for education for democratic citizenship—civic education is a separate subject, it is integrated into the block of social sciences and, at the same time, democratic citizenship has become a cross-curricular competence for all study subjects which corresponds to the country’s political priority—to carry out the democratic transformation of the post-soviet society.

Comparative analysis of local and international experiencesFootnote3 showed that there is no homogeneous model of civic education curriculum: (a) traditional curricula are mainly content-oriented and textbook-based; (b) a goal-oriented curriculum focuses on the learning process and skills, instead of focusing on values and socio-emotional learning; (c) the process-based curriculum focuses on interactive teaching methodology, such as a collaborative teaching; (d) The competency-based curriculum envisages approach to “a child as a whole”, whose learning outcomes include the knowledge, skills and attitudes and are based on values and motivation that are fully in line with the essence and goals of education for democratic citizenship.

1.3. Collaborative learning in civic education

The development of civic competencies in students is related to the teaching methodology used in the classroom (Grindheim, Citation2017); (Carretero et al., Citation2015); (Allen & Light, Citation2015). Approaches based on knowledge acquisition alone are not enough to nurture critically-minded, active citizens distinguished by the sense of responsibility. It is necessary to introduce such forms of education that will be focused on each student and will help them to develop into a full-fledged citizen of the 21st century.

Providing the student-centered teaching is a serious challenge for teachers as it requires constant updating of knowledge, mastering the new teaching methods, finding the new ways of working and establishing new forms of professional relationships with colleagues and students. Student-centered pedagogy focuses on the development of not only cognitive and metacognitive, but also social skills in students. Without developing this range of skills, it is impossible to raise full-fledged citizens of a democratic society.

Conducted studies have confirmed the effectiveness of collaborative teaching, both in terms of maximizing learning outcomes for all students (Gillies, Citation2003); (Johnson & Johnson, Citation2013); (Johnson et al., Citation2006); (Slavin, Citation1995); (Slavin, Citation1996) and developing social skills (Johnson et al., Citation1990); (Stevens & Slavin, Citation1995).

Collaborative teaching helps students avoid social problems (Johnson et al., Citation2000), reduce violence (Cowie & Berdondini, Citation2001), and manage conflict (Stevahn et al., Citation1997). Students develop high thinking skills (King et al., Citation1998), ask questions by which they help each other discover a different perspective (Palincsar & Herrenkohl, Citation2002).

Interaction in a democratic classroom involves students’ active participation in their own learning process, cooperation, respect, recognition of equality (Fearnley-Sander et al., Citation2004). In addition, in a democratic school culture, when we not only teach civic education and citizenship, but also offer a collaborative environment, the potential for developing civic competence increases (Fearnley-Sander et al., Citation2001). Dewey’s (Dewey, Citation2008) definition of the concept of democracy is like this—“This (democracy) is a way of life.” According to him, the development of personal characteristics occurs through interpersonal relationships, which, in turn, affects the behavior of the person. He considered the teacher as an agent of changes who could bring the society, built on democratic values, to perfection. Thus, the classroom can be viewed as a micromodel of our wider community (Schul, Citation2011). Collaborative teaching is essential to building a democratic classroom culture because it affects everyday life, relationships, teaching about democracy, and the development of democratic values in the classroom (Vinterek, Citation2010). The use of collaborative teaching methods is an important guarantee for developing democratic values in students and establishing the democratic culture in schools.

2. Research AIM and hypothesis

To better understand the relation between collaborative teaching, development of competencies for democratic citizenship and democratic school culture, the study attempts to study: (1) practical experience of using collaborative teaching strategies by teachers of Georgian secondary schools; (2) their views on students’ competencies for democratic citizenship and on the influence of collaborative teaching strategies on democratic school culture; (3) Correlations between these two data.

To achieve the research aim, we have formulated four main research questions:

To what extent do teachers consider civic education to be a cross-curricular competence?

What do teachers consider to be the goal of teaching civic education as a cross-curricular competence?

To what extent do teachers use collaborative teaching strategies?

What impact do the collaborative teaching strategies used by teachers have on the development of students’ civic competencies and democratic school culture?

Based on the research aim and the research questions, a research hypothesis has been formed:

If teachers view civic education as a cross-curricular competency, the employment of collaborative teaching methodologies encourages, on the one hand, the development of democratic citizenship competences in students and, on the other hand, it fosters a democratic school culture.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Research framework

On the basis of international—(Council of Europe, Citation2020; International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, Citation2016) and local—(Government of Georgia, Citation2004; Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia, Citation2011–2016),—experience, we have developed a Civic Education Framework for the research, which includes the content and methodology of the civic education.

The content of the teaching of democratic citizenship has been defined as:

Essence of civic education

Responsibilities and rights

School culture

Community membership

Respect for dissent

Expressing your own opinions

Discrimination (racism, chauvinism, oppression)

Solving school/community problems

Global problems and the protection of environment

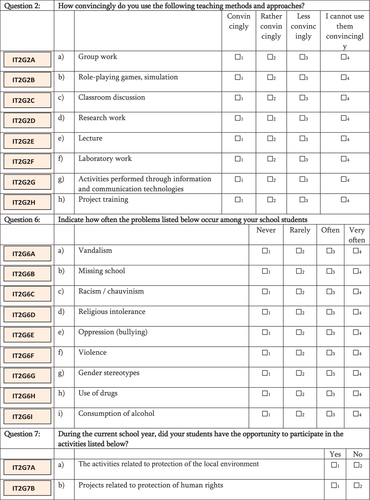

As for the methodology, we relied on the most common collaborative teaching strategies (group work, role-playing games, classroom discussion, research work, project-based teaching) and explored their impact on the development of students’ civic competencies.

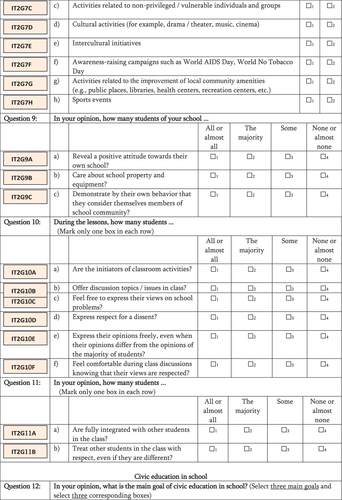

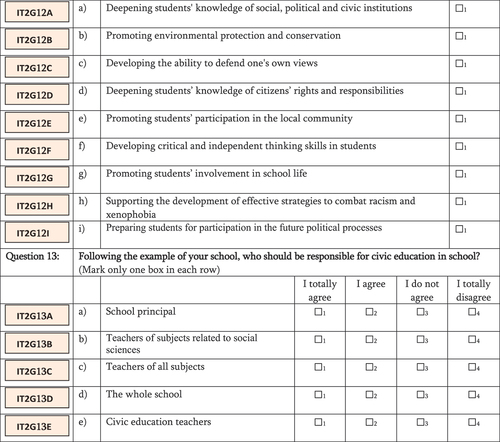

To study the professional experience of teachers in teaching democratic citizenship based on the Citizenship Competences Framework (Council of Europe, Citation2020) we used a questionnaire developed by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement—IEA (International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, Citation2016) for this purpose (see an App. N1). We piloted the questionnaire with teachers from non-target schools in the target regions to assess its validity. The wording of the questions was improved in the final version of the questionnaire, which was created based on the results of the piloting (during the piloting, the respondents requested more clearly defined questions), in order to make it easier for the respondents to understand. The similarity of the results of the pilot and the final versions also confirmed a relatively high degree of reliability of the questionnaire.

3.2. Research object

Urban (Tbilisi, Kutaisi, Zugdidi, Rustavi, Akhaltsikhe) centers and rural (Imereti, Kvemo Kartli, Samtskhe-Javakheti, Samegrelo) regions were purposefully selected as the target regions. The selected towns and villages are located in different parts of Georgia, which are distinguished from each other by ethno-culturalFootnote4 composition of the population. The target groups cover the ethno-cultural diversity of Georgia and the peculiarities of the regional development, which increases the possibility of generalizing the research results obtained at the national level.

34 schools were identified through random sampling from the target regions. Teachers of different subjects had to be represented in the research in order to cover a diverse range of subjects. A total of 374 teachers were interviewed within the study.Footnote5

3.3. Research methods and tools

We used a questionnaire to determine teachers’ attitude towards teaching citizenship as well as the impact of collaborative strategies on students’ civic competencies. In developing them, we have relied on the civic education research framework that we have developed (see section Research Framework).

The purpose of the teachers’ survey was to find out their views on the following issues: 1) what teaching methods they use; 2) what attitude they have towards civic education and (3) what is a role they play in the civic education of students.

QuestionnaireFootnote6 consists of three main areas/rubrics: (a) under the rubric General Information we obtained the demographic data of the respondents. In the same rubric, it was determined which teaching methods the respondents use with more confidence and how systematically they use them;

(b) Under the rubric “School” we have obtained information about:

Collaborative culture established in the school;

Involvement of teachers and students in school decision-making (including formal and informal learning activities);

Affiliation of the members of school community to school.

(c) The rubric “Civic education in school” defines the attitude of teachers towards civic education:

How teachers understand the purpose of teaching it;

Who is responsible for civic education in school;

What sources they rely on and what methods they use for teaching citizenship;

Which issues/topics of civic education they feel confident with in their teaching.

The coding of the respondents’ responses included four main stages: 1. Writing a code to each response; 2. Making an online data system; 3. Creating a book of codes. 4. Checking the codes and clearing the data. Each respondent was included in a single category of variables. A separate code was developed for a specific response.

The data was entered into Microsoft Excel, and filtering, sorting, and data validation systems were used to facilitate database variation and encoding.

The data was processed by statistical software package R. More than 120 variables were used in the study. Most of them are ordinary variables. We used the correlation matrix with polychoric correlation coefficients to select the variables participating in the analysis. We selected variables with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.3. The associations between categorical variables were tested by Chi-Square Test of Independence. Like any statistical testing, we tested it against the chosen p-value: 0.05. When the p-value is significant, we reject the null hypothesis (there is no relationship between the variables) and claim that the findings support the alternative hypothesis (there is a relationship between variables).

Contingency tables (cross-tabulations) were used to analyze the data and display the results, with each row representing the level (group) for one variable and each column representing the level (group) for another variable. To highlight the differences between different sets of data, we also used combination charts.

By the correlation analysis, we determined the relation of collaborative learning to students’ civic competencies and the democratic culture of school. The relationship between the variables was also checked using Ordinal Regression.

3.4. Methodological limitations of the research

At this stage of the research, teachers’ responses were not diversified according to their geographical and cultural characteristics. This time, our main task was to study the main trends in the teaching of democratic citizenship, on the basis of which, in the long run, the data will be detailed and analyzed according to the target variables.

We also consider the limitation of the research to be that the research question has been studied and evaluated only from the teacher’s perspective. At this stage of the research, we did not study the positions of the school community on the same issues and did not contrast them with each other for more credibility of the research results. It could also be a prospect for a future research.

Students’ civic competencies were not measured within the research and these data were not contrasted with teachers’ relevant opinions, which would help us determine the objectivity of teachers’ self-assessment of their own practice.

4. Data analysis and main results

The study identified: (a) teachers’ attitudes towards the importance and purpose of civic education, and (b) what collaborative teaching methods teachers use and how the methods used by them relate to students’ civic competencies.

5. Statement 1. Responsibility for civic education in schools

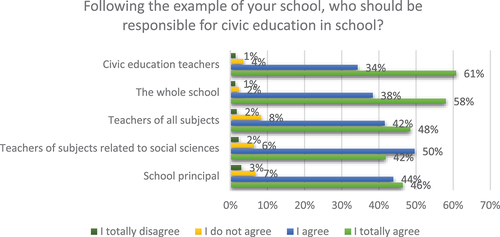

When asked who should be responsible for civic education, respondents’ answers according to priorities are as follows: 71.9% think of civic education teachers; 78.6% believe that the school as a whole is responsible; 70.1% indicate the joint responsibility of teachers of all subjects; 57.2% emphasize the responsibility of the school principal and 65.5% assign the responsibility to the teachers of subjects related to social sciences (App. N2).

Regarding the first provision, 100% of civic education teachers (who make up 15% of the total respondents) believe that teachers of all subjects are responsible for civic education. The positive response rate of teachers of other subjects to this question is 88%. This small difference can be explained by the fact that civic education teachers are more aware of the versatility of civic education and its importance as a cross-curricular competence (App. N3).

6. Statement 2. Education—the ultimate goal for democratic citizenship

To the question—What do teachers consider to be three ultimate goals of civic education?—the answers of the respondents were distributed as follows:

Developing critical and independent thinking skills in students—59.9%

Deepening students’ knowledge about citizens’ rights and responsibilities—59.4%

Deepening students’ knowledge of social, political and civic institutions—49.2%

Developing the ability to defend one’s own views—43.6%

Promoting protection and preservation of the environment—37.7%

Promoting student involvement in school life—34.0%

Promoting student participation in the local community—22.2%

Supporting the development of effective strategies to combat racism and xenophobia—14.4%

Preparing students for participation in the future political processes—10.7%

The responses of civic education teachers to a number of points of the provision somewhat differ from the results obtained by surveying teachers of other subjects. In particular, civic education teachers among the goals of teaching for democratic citizenship focus more on the following: Promoting student participation in the local community—34.3% (overall benchmark—22.2%), Preparing students for participation in the future political processes—18.7% (overall benchmark—10.7%) and Promoting student involvement in school life—46.4% (overall benchmark—34.0%). It can be explained by the fact that they better understand the content of civic education, better analyze the impact of civic education on current processes in the society and the importance of future citizens in them.

7. Statement 3. Teaching-learning strategies and their effectiveness. Education for democratic citizenship

To the question—How convincingly do you use collaborative teaching methods?—the majority of respondents answer that they most convincingly use group work (24% completely convincingly and 63% quite convincingly) and classroom discussion (31% completely convincingly and 52% quite convincingly). In the case of role-play, research work, project-based learning, and activities conducted through information and communication technologies, respondents’ replies are non-homogeneous—about half (50–54%) of the respondents think that they use these methods completely and quite convincingly, while the other half thinks that they are less confident when using these methods and experience serious difficulties.

From the obtained data we can conclude that a solid part of the surveyed teachers is sure that they convincingly use the teaching methods the purposeful and effective use of which is a precondition for the development of civic competencies in students.

The overview of the application of collaborative teaching methods and their impact follows below.

7.1. Group work

The practice of using group work by subjects/subject groups was distributed as follows—this method is most often used by social science teachers (83%); the use of group work by the teachers of Georgian language and literature, mathematics, foreign languages and natural sciences is also relatively high (consent rate varies from 56% to 64%). The lowest rates were observed with teachers of aesthetic education (45%) and sports (32%).

The relation between variables showed the following trend:

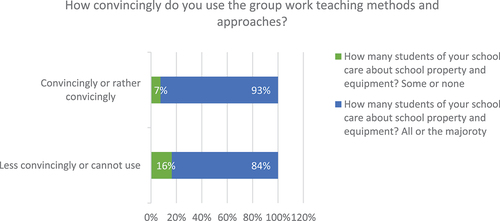

1. Group Work vs. Students’ Affiliation to School. 91% of teachers who use group work frequently and confidently indicate that vandalism on the part of students never or rarely occurs. Such a correlation can be explained by the fact that group work develops both personal and shared responsibilities in students, they develop the sense of belonging to the group. This in itself increases their affiliation to school, which is revealed by the care and maintenance of school property (App. N4).

2. Group Work vs. Membership of the School Community. While carrying out a group work, by their behavior students demonstrate that they consider themselves members of the school community—this is the opinion of 93% of teachers who often and confidently use group work with their students. This connection is logical because the correctly directed group work make students feel themselves like full-fledged members of the group, which is the basis for a sense of school community membership (App. N5).

3. Group Work vs. Respect for a Dissent. 85% of teachers, who are confident in using group work, say that the majority of their students show respect for dissent (App. N6).

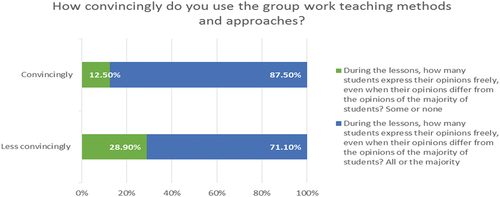

4. Group Work vs. Freely Expressing One’s Opinions. 87.5% of teachers, who use group work systematically and confidently, say that the majority of their students are free to express their opinions. One of the most important civic competencies is the ability of students to freely express their own views (freedom of self-expression) and to listen and respect the opinions of others (including different ones). This is facilitated by the integration of collaborative teaching strategies into the learning process, including group work. The teacher, who is confident in their own competence and bases the learning process on the principle of cooperation, encourages students to freely express their positions and feel respect for a dissent (App. N7).

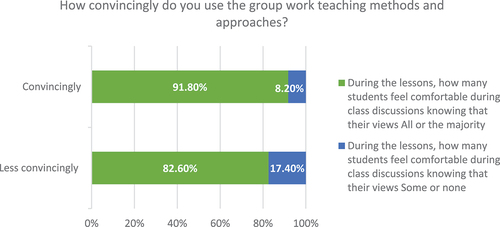

5. Group Work vs. Feeling of Comfort. 91.8% of teachers, who use group work systematically and confidently, say that the majority of their students feel comfortable and safe in the classroom environment in general and including when discussing pressing issues. Collaborative learning team members contribute to each other’s success because they:

Provide assistance and receive support;

Exchange information and “material resources”;

React to each other’s academic achievements and backwardness;

Teach each other to lead a discussion and defend their own position;

Support each other to achieve a success;

Affect each other;

Have a sharply pronounced motivation (the pursuit of knowledge is intensified through collective work);

Create an atmosphere of mutual trust;

Successfully cope with stress and irritability.

The above circumstances give students a sense of safety and comfort (App. N8).

7.2. Role-play

The practice of using role-play by subjects/subject groups was distributed as follows—most often this method is used by the teachers of social sciences (67%), Georgian language and literature (67%), aesthetic education (66%) and foreign languages (62 %). The lowest rates were observed with teachers of mathematics and sciences (36–36%) (App. N9).

The relation between variables showed the following trend:

1. Role-plays vs. racism/chauvinism Nearly 100% of the teachers, who use role-playing games systematically and confidently, say that racism/chauvinism has never or almost never been manifested among their students.

2. Role-plays vs. Religious Intolerance. 96% of the teachers, who use role-playing games systematically and confidently, say that religious intolerance has never or almost never been revealed among their students.

3. Role-plays vs. Oppression (Bullying). 98% of the teachers, who use role-playing games systematically and confidently, say that oppression (bullying) has never or almost never been revealed among their students.

Role-play evokes a sense of empathy in students, because while working with this method, students have to look at events through the eyes of others, take into account their subjective reality, which helps students reassess values, develop a tolerant attitude towards a different position. This in itself reduces the manifestation of racism and chauvinism, religious intolerance or bullying.

7.3. Classroom discussion

The practice of using classroom discussion by subjects/subject groups reaches a very high percentage in almost all subjects—social sciences (91.8%), Georgian language and literature (90.9%), foreign languages (89.6%), aesthetic education (85.7%), natural sciences (82.6) %). The teachers of mathematics use relatively little discussion (76.1%) (App. N10).

The relation between variables showed the following trend:

1. Classroom Discussions vs. Manifestation of Racism/Chauvinism. Nearly 100% of the teachers, who use classroom discussion systematically and confidently, say that racism/chauvinism has never or almost never been manifested among their students (The same rate was observed when using group work).

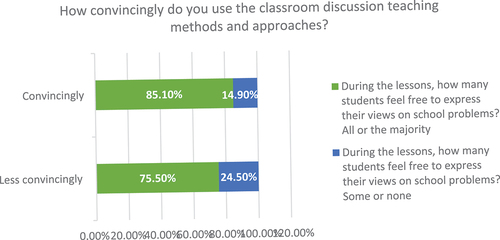

2. Classroom Discussion vs. Expressing One’s Opinions Freely regarding School Problems. 85% of the teachers, who use classroom discussion systematically and confidently, say that the majority of their students express their opinions freely regarding school problems (App. N11).

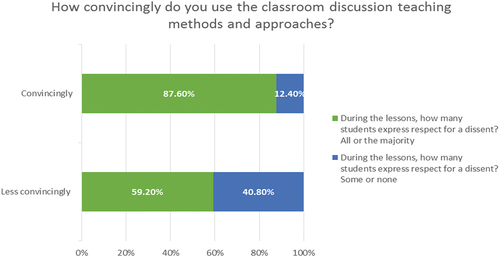

3. Classroom Discussions vs. Respect for a Dissent. 87.6% of the teachers, who use classroom discussion systematically and confidently, say that the majority of their students express their respect for a dissent (App. N12).

The same correlations were observed for the use of the discussion method convincingly as for group work. This can be explained by the fact that both methods of collaborative teaching aim at developing cross-curricular competencies in students, such as expressing and argumenting their own position, at the same time, listening to the opinions of others, respecting and taking them into account. It is a basic skill of a good citizen and it is achieved through proper teaching.

7.4. Research-based teaching

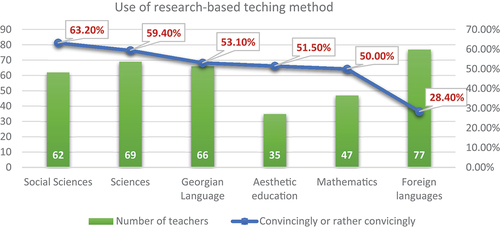

Research-based teaching by subjects/subject groups is most often used by the teachers of social sciences (63.2%) and natural sciences (59.4%). Statistically average indicators were observed with the teachers of Georgian language and literature (53.1%), aesthetic education (51.1%) and mathematics (50.0%). The teachers of foreign languages (28.6%) rarely use the research work (App. N13).

The relation between variables showed the following trend:

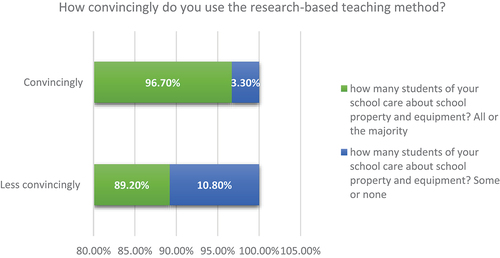

1. Research-Based Teaching vs. Taking Care of School Property and Equipment. 96.7% of the teachers, who use research-based teaching systematically and confidently, claim that the majority of their students care about school property and equipment (App. N14).

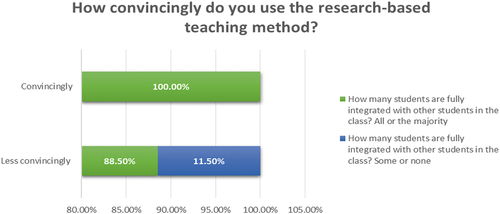

2. Research-based Teaching vs. Student Integration. Nearly 100% of the teachers, who consistently and confidently use research-based teaching, claim that the majority of their students are fully integrated with other students in the class (App. N15).

3. Research-Based Teaching vs. Student Discipline. Nearly 95% of the teachers, who consistently and confidently use research-based teaching, say that their students never or almost never miss school (App. N16).

Thus, the systematic use of research work by the teacher has a positive impact on students’ care for school property and equipment, promoting their integration and discipline. There can be several reasons for this positive interaction: students use school inventory to conduct the research. Inventory is associated with the joy of discovery, the acquisition of new knowledge and, consequently, it becomes necessary to take care of it for future work. On the other hand, research work, by its very nature, requires the cooperation of different people and their transformation into a harmonious and coordinated whole, which is impossible without a strict internal order.

7.5. Project-based teaching

According to the answers of the teachers of the subjects/subject groups, the frequency of using project-based teaching was distributed as follows: Social sciences 87%, Georgian language and literature—68%, Mathematics—68%, Aesthetic education—60%, Foreign languages—54%, Natural sciences—54% (App. N17).

The relation between variables showed the following trend:

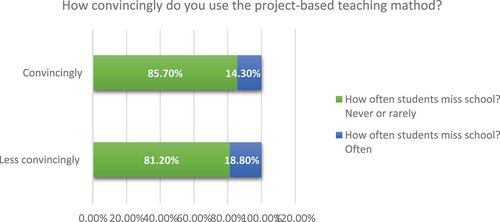

1. Project-Based Teaching vs. Student discipline. The teachers who are confident and systematic in project-based teaching, in almost 85.7% of cases, claim that their students never or almost never miss school for no reason (App. N18).

2. Project-Based Teaching vs. Activities Related to Protection of the Local Environment. In almost 100% of cases teachers, who are confident and systematic in project-based teaching, claim that during the current school year their students had the opportunity to participate in the activities related to protection of the local environment.

3. Project-based Teaching vs. Care about School Equipment. The teachers, who are confident and systematic in project-based teaching, in almost 95.3% of cases, claim that the majority of their students care about school equipment.

The correlations revealed during the project-based teaching indicate the important competencies of the citizen, such as discipline, environmental awareness, and caring for school. Project-based teaching develops three most important metacognitive skills in students—planning, monitoring and evaluation. Also, in project-based teaching, students take responsibility for their own learning process and develop into self-regulatory learners, get accustomed to meeting deadlines when doing their assignments. All of this, in turn, develops students’ discipline. Special care for school in project-based teaching should be explained by the fact that this method of teaching goes beyond the classroom, students have to work on extracurricular projects in addition to curricular ones and they use school resources, which increases students’ caring attitude towards school property.

The data presented and their analysis clearly reveal the positive impact of collaborative teaching methods on student behavior (caring, discipline, respect, participation) and attitudes (affiliation to school, openness, acceptance, recognition and appreciation of difference).

7.6. Key findings and discussion

1. The confident, systematic and purposeful use of collaborative teaching methods by the teacher has a positive impact on the development of civic competencies in students:

a) 82.6% of the total number of teachers deny the existence of racial and religious intolerance in students. This rate is significantly higher for teachers who use role-playing games (100%) and classroom discussions (96%) frequently and confidently;

b) 67% of the surveyed teachers believe that all or almost all students show a positive attitude towards their school and 72% believe that all or almost all students demonstrate by their own behavior that they consider themselves members of the school community. According to the teachers who systematically and confidently use group work and project-based teaching, the similar position is shown by almost the entire composition of students (91% and 93%, respectively);

c) 98% of the teachers, who confidently and systematically use role-playing games, believe that bullying does not occur among students. This figure is 86% of the total number of teachers surveyed;

d) When teachers use classroom discussions, research projects and group work purposefully, confidently and systematically, 98% of such teachers indicate that their students feel comfortable and safe in the classroom/school environment. This figure is 83% of the total number of teachers surveyed. A lower rate (76%) was observed in the group of those teachers who rarely use the listed methods;

e) In the range of 49% to 58% is the total number of teachers who believe that the majority of students freely express their views on school problems; Express respect for a dissent; In general, freely express their own opinions, even when their opinions differ from the position of most students, and they feel comfortable during classroom discussions because they know that their views are respected. For comparison—high percentages were observed in those teachers who systematically and confidently use group work and classroom discussions: respect for a dissent by students—85%, free expression of opinions by students—87.5%;

f) To the question—How many students are fully integrated with other students in the class?—the answer of 72% of teachers is—“all or almost all students”. And to the question—How many students treat other students with respect, even if they are different?—the answer of 76% of teachers is—“all or almost all students”. These percentages are relatively high for teachers who systematically and confidently use research-based teaching: 91.3% for the first question and 95.6% for the second.

g) According to mediated data, 67% of teachers indicate student participation in project activities. Their responses show that 46% of students participated in environmental activities, while 48% of students participated in human rights projects during the last school year. Students’ activity in cultural projects, in awareness-raising campaigns (World AIDS Day, World No Tobacco Day), as well as in sports events, is quite high at 63%, 62% and 71%, respectively. The student activity rate was low in the events related to vulnerable individuals/groups (40.4%) and activities related to the improvement of local community amenities (42.6%). These percentages are much more visible in the case of teachers who systematically and confidently implement project-based teaching. In particular, 84% of teachers in this category indicate that students periodically participate in community projects (especially in schools in the regions), while the participation of students in environmental activities is confirmed by almost 100% of respondents in this category.

h) Teachers who are confident in using the methods of group work (91%), research work (96.7%), project-based teaching (95.3%) indicate that their students take care of school property and equipment, do not manifest vandalism. For comparison, 79.7% of the total number of teachers state that vandalism never occurs in their school.

International studies also confirm that pedagogical approaches used by the teacher at the lesson and the forms of organizing learning activities are more important for civic education than the content of the individual discipline. Declarative knowledge-oriented lessons make the learning process monotonous and boring, fail to ensure students’ activity and never encourage their initiatives (UNESCO, Citation2014). ProceduralFootnote7 and conditionalFootnote8 knowledge and systematic participation of students in discussions, learning, research and social projects, as well as school culture democracy and student participation in school/classroom decision-making are especially important for the successful implementation of civic education (Gainous & Martens, Citation2011).

2. The systematicity, self-confidence and effectiveness of the use of collaborative teaching approaches are to some extent related to teachers’ ageFootnote9 and experience:

a) The highest rate of use of classroom discussions is observed in teachers aged 21–40 years. 90.5% of them indicate that they do not find it difficult to create a discussion environment and often use discussion among students on pressing issues. This figure is relatively low in older age groups: discussion is used by 81.4% of teachers aged 41 to 55 years, and by 80.0% of respondents aged 56 to 75 years (App. N19).

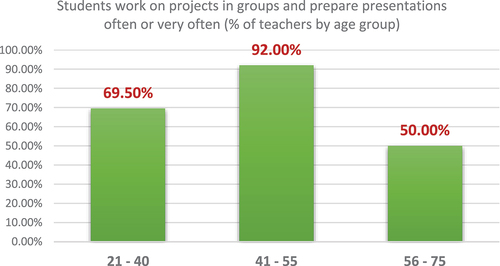

b) 69.5% of teachers aged 21–40 years state that their students often or very often work on the project in groups and prepare presentations. This rate is particularly high for teachers aged 41–55 years (92%) and decreases for teachers over 55 years (50%) (App. N20).

From the obtained data it can be said that the use of active, constructivist-oriented methods of collaborative teaching is directly related to the teacher’s age and pedagogical experience. Young teachers have more openness and more access/knowledge about novelties. This makes it easier for them to boldly apply new approaches. In addition, the effective use of discussion, research, project and other components, a certain precondition of which is the belief in one’s own abilities (self-confidence), is also related to practical experience.

3. The Georgian National Curriculum (Ministry of Education and science of Georgia, Citation2018–2024) views citizenship as the goal to be achieved by all subjects and the cross-curricular competence of the general education process. Most of the teachers involved in the study openly share this approach of the National Curriculum, however, when asked who is responsible for civic education at school, the almost uniformly high benchmark of the consent for different addressees (principal, civic education teacher, social sciences teacher) indicates that most of the teachers do not see the space and opportunity needed to teach democratic citizenship within their subjects.

Studies show that even in Western education system, most schools do not prioritize civic education goals over their own educational practices (Ajegbo et al., Citation2007). The willingness of existing teachers to link the teaching process of the subject with the development of civic competencies in students is quite low (Peterson et al., Citation2014). Lack of knowledge of the goals of civic education and the methodology of its implementation is also observed in would-be teachers—students of the teacher training program (Peterson & Knowles, Citation2009).

4. The use of collaborative teaching strategies supports the growth of a democratic school culture, which has as one of its requirements the involvement of students in decision-making processes, the practice of considering/respecting their viewpoints, and the encouragement of their initiatives. According to research, teachers who confidently and methodically include class debates, group projects, and subject content adaptation to real-world situations have relatively high expectations that students with established civic competences can improve the climate of the school as a whole. However, it has been demonstrated time and time again that civic competencies in students may be developed successfully if they are seen by teachers as cross-curricular competencies and any subject is taught in a democratic classroom setting through collaborative strategies.

International studies also affirm that an inclusive curriculum that encompasses democratic knowledge, skills, and experiences that are taught, modeled, and repeatedly reinforced through educational and social activities has a particular impact on school culture (Abdi & Richardson, Citation2008). It is critical to establish participatory democracy so that students can learn how to run their schools’ democracies and deal with issues of school culture (Thornberg & Elvstrand, Citation2012).

8. Conclusions and recommendations

The systematic and targeted use of collaborative approaches in formal and non-formal education remains a challenge in Georgia’s general education schools despite the fact that creating a collaborative teaching environment is one of the National Curriculum’s keystones, serving as a foundation for students’ development of competencies needed for democratic citizenship (Gogitidze, Citation2020).

The process of developing active, informed and responsible student’s requires the teacher to acquire modern forms of interactive (i.e. collaborative) teaching methods, and student-centered pedagogy that focuses on developing the skills of critical thinking and active participation in processes.

The present study showed, that:

1. The majority of civic education teachers and teachers of other disciplines think that students’ civic education is a cross-curricular competency. A review of their real-world experiences, however, showed that most of them prioritize the transfer of only particular academic knowledge rather than making an attempt to help students develop their civic competency.

2. The majority of respondents think that the objective of civic education as a cross-curricular competency is to develop in students such fundamental knowledge and skill of a good citizen as expressing and justifying their own position, while also listening to, respecting, and taking into account other people’s opinions. However, studies have indicated that employing collaborative, student-centered teaching practices to accomplish these aims is still relatively new, which poses a barrier.

3. The systematic, confident and purposeful use of collaborative teaching-learning strategies leads to the development of civic competencies:

Group work—(a) has a positive effect on students’ affiliation with the school (students are more careful about classroom/school property and equipment, less vandalism occurs); (b) helps the student to recognize himself/herself as a member of the school community; (c) develops a sense of respect for a dissent and encourages the student to express his or her position freely; (d) Develops a sense of safety, appreciation and recognition for the student.

Role-play—(a) reduces racism, chauvinism and religious intolerance and thus promotes a tolerant attitude; (b) reduces oppression (bullying) and helps the student to see and evaluate people and events from a different perspective.

Classroom discussion—(a) promotes the acceptance of different groups and cultures; (b) enhances the respect for a dissent and makes it possible to take them into consideration; (c) Creates an encouraging environment for students to freely express their views on school/classroom problems.

Research work—(a) promotes student integration; (b) enhances the student’s affiliation with the school; (c) leads to student autonomy and self-organization.

Project-based teaching—(a) stimulates the student’s positive attitude towards the learning process and school environment; (b) increases the student’s social competencies, knowledge and interest in the surrounded world.

4. Collaborative teaching is still less used in Georgian educational practice. However, international experience demonstrates the effectiveness of various forms of collaborative teaching (school projects, research-based teaching, role-play, etc.) in developing competencies required for democratic citizenship (Allan & Charles, Citation2013).

5. Using collaborative teaching strategies consistently and incorporating them into the learning process, as well as putting the theoretical portion of civic education into practice, helps students recognize themselves as members of the school community, cultivate respect for dissent, boost self-esteem, encourage a sense of safety and recognition, cultivate a tolerant attitude, develop diverse viewpoints, etc. All of this is a basic requirement the development of the democratic culture at the school.

6. Student-centered teaching methods, student participation in classroom and school decision-making, encouragement of student initiative, and the overall development of a collaborative culture are used to create the democratic school culture. The lack of school autonomy and internal democracy, the lack of cooperation between members of the school community (student-student, teacher-teacher, teacher-student, teacher-school administration, teacher-parent, student-parent), and the educational process’s primary emphasis on knowledge accumulation all hinder the development of these processes in Georgian schools.

Based on the research findings, recommendations can be formulated on several levels:

At the individual level—existing teachers need to take care about making collaborative strategies an integral part of their professional activities. It will enable their students to be actively involved in the learning process and it will foster the development of students’ civic competencies.

At the school level—(a) School should develop an explicit and implicit curriculum ensuring the development of civic competencies in students; (b) School should promote the development of the collaboration culture among teachers, make it part of the school culture and offer a variety of opportunities in this area; (c) School should enhance the interaction of formal and informal components of civic education (recognition, completion, coordination, etc.).

At the state level—(a) Supportive measures of key importance from the State for learning citizenship are not sufficient and consistent. This is particularly true for the value component of educational programs, which in most cases is only formal and declarative. It is necessary to promote the actual implementation of the National Curriculum based on civic competencies; (b) State should develop diverse learning resources to promote civic competencies; (c) Provision of diverse opportunities for teacher-centered professional development focused on their needs for secondary schools.

The study’s findings, which provide a fundamental understanding of the influence of formal education on students’ acquisition of citizenship competencies and civic participation, serve as the foundation for future interdisciplinary research.

The findings of this study and recommendations, which can be applied and modified by researchers and practitioners in the field, are significant because they represent an original approach based on international experience toward enhancing integration and civic involvement. On the other hand, research findings and trends can be incorporated into the school’s organizational culture, which is a prerequisite for the growth of a democratic school culture.

At the same time, the implementation of democratic citizenship platforms across Europe benefits from Georgia’s experience and the findings of our research (Council of Europe, Citation2020). Another viewpoint is that Georgia actively participated in the creation and implementation of those European documents along with the other Council of Europe members. In this regard, taking into account the study’s findings paves the way for fresh local and worldwide research (ies).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

David Malazonia

The research was held at Ilia State University within the framework of project Democratic Citizenship in Schools of Georgia: Challenges and Avenues for Development (#FR-18-1887) funded by Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation. The project is implemented by professors of School of Education at Ilia State University: David Malazonia (Research Director) and researchers Sofiko Lobzhanidze, Shorena Maglakelidze, Nino Chiabrishvili, Natia Natsvlishvili and Zakaria Giunashvili. The Project is aimed to examine school students’ competencies for democratic citizenship, develop different pedagogical approaches encouraging and supporting development of these competencies.

Researchers have valuable experience in intercultural and civic/citizenship education and instructional strategies. They actively participate in different projects on national and international levels, i.e. Intercultural Education: Problems and Development perspectives in Georgia; Development of International Model for Curriculum Reform Supporting Multicultural and Citizenship Education, etc.

The current study will lay a strong platform for future research on students’ civic literacy in higher education institutions.

Notes

1. In 2020–2021, as a part of a desk research, we studied the National Curricula for General Education of 16 countries with different indices of democracy development (Malazonia et al., Citation2022).

2. We used a desk research to compare national and foreign curricula in terms of democratic citizenship (Malazonia et al., Citation2022).

3. Rural regions—Samegrelo, Javakheti, Imereti and cities—Zugdidi, Kutaisi, Akhalkalaki and Marneuli are distinguished by the concentration of monoethnic population. Tbilisi, Rustavi, Akhaltsikhe and Kvemo Kartli region are multicultural urban centers.

4. The number of teachers was distributed according to the subject principle like this—foreign languages—21%, natural science—18%, Georgian language and literature—18%; Social Sciences—17%, Mathematics—13%, Aesthetic Education—9%, Sports—5%.

5. The questionnaire consists of 18 main questions, which are broken down into sub-questions. Teachers filled out a printed version of it, which took 80 minutes to complete on average.

6. Can apply what is learned in a specific situation.

7. Can transfer knowledge in different contexts.

8. Respondents aged 21 to 40 accounted for 25.7% of the total number of respondents, the share of teachers aged 41 to 55 was 44.9%, and the number of respondents aged 56 to 75 was 29.4%.

9. Group work

10. Expresses respect for a dissent

11. Group work

12. The student freely expresses their opinions, even when their opinions differ from the opinions of the majority of students.

13. Group work

14. The student feels comfortable in the classroom because they know that their views are respected.

15. Classroom discussion

16. The student freely expresses their views regarding school problems

17. Classroom discussion

18. The student expresses respect for a dissent

19. Research work

20. Takes care of school property and equipment

21. Research work

22. The student is fully integrated with the other students in the class

23. Research work

24. Frequency of missing school

25. Project-based teaching

26. Missing school for no reason

References

- Abdi, A. A., & Richardson, G. (2008, January 01). Decolonizing democratic education: An introduction. A. A. Abdi & G. Richardson, (Eds.) Decolonizing democratic education: Trans-disciplinary dialogues (Vol. 26, pp. 1–38). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789087906009_002

- Ajegbo, K., Kiwan, D., & Sharma, S. (2007). Diversity and Citizenship: Curriculum Review. Annesley: DfES Publication. http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/pdfs/2007-ajegbo-report-citizenship.pdf

- Albulescu, M., & Albulescu, I. (2015). Overtones in contemporary educational theory and practice: Education for democratic citizenship. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 209, 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.263

- Allan, A., & Charles, C. (2013). Preparing for life in the global village: Producing global citizen subjects in UK schools. Research Papers in Education, 30(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2013.851730

- Allen, D., & Light, J. (2015). From voice to influence: Understanding citizenship in a digital age. University of Chicago Press.

- Anyon, J. (2008). Theory and educational research: Toward critical social explanation. Routledge.

- Apple, M. W., & Beane, J. A. (2007). Democratic schools: Lessons in powerful education (2nd) ed.). Heinemann.

- Banks, J. A. (2002). Race, knowledge construction, and education in the USA: Lessons from history. Race Ethnicity and Education, 5(1), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320120117171

- Bîrzea, C. (2005). EDC policies in Europe - a synthesis. In A. Garabagiu (Ed.), All-European study on education for democratic citizenship policies (pp. 13–69). Council of Europe Publishing.

- Carretero, M., Haste, H., & Bermudez, A. (2015). Civic Education. In L. Corno & E. Anderman (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (3rd Edition ed) ed., pp. 295–308). Routledge.

- Chargeishvili, S. (2019). Study of students’ democratic culture on the example of one school in Tbilisi. Master Thesis. Ilia State University.

- Civic Education Lecturers Association - CELA. (2017). Civic education and the experience of democracy in Post-Soviet Countries. Tbilisi.

- Council of Europe. (2020, December). Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (RFCDC). https://rm.coe.int/prems-007021-rfcdc-competences-for-democratic-culture-and-the-importan/1680a217cc

- Cowie, H., & Berdondini, L. (2001). Children’s reactions to cooperative group work: A strategy for enhancing peer relationships among bullies, victims and bystanders. Learning and Instruction, 11(6), 517–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(01)00006-8

- Dewey, J. (2008). Democracy and Education 1916. Schools: Studies in Education, 5(1/2), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1086/591813

- Fearnley-Sander, M., Moss, J., & Harbon, L. (2001). The civic school: Australian-Indonesian professional collaboration to model and audit the development of democratic primary classrooms and teacher language using the Index for Inclusion. AARE 2001: Crossing borders: New frontiers in educational research: Australian Association for Research in Education conference proceedings (pp. 1-16). Australian Association for Research in Education. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277995997_The_Civic_School_Australian-Indonesian_professional_collaboration_to_model_and_audit_the_development_of_democratic_primary_classrooms_and_teacher_language_using_the_index_for_inclusion

- Fearnley-Sander, M., Moss, J., & Harbon, L. (2004). Reading for meaning: problematizing inclusion in Indonesian civic education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 8(2), 203–219. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ939360

- Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the word & the world. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Gainous, J., & Martens, A. M. (2011). The effectiveness of civic education: Are “Good” teachers actually good for “All” students? American Politics Research, 40(2), 232–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1532673X11419492

- Gillies, R. M. (2003). The behaviors, interactions, and perceptions of junior high school students during small-group learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.137

- Giroux, H. A. (2004). Critical pedagogy and the postmodern/modern divide: Towards a pedagogy of democratization. Teacher Education Quarterly, 31(1), 31–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23478412

- Gogitidze, T. (2020). Development of collaborative skills in students. Tbilisi, Georgia, Georgia. https://openscience.ge/bitstream/1/2233/4/Teona%20GogitiDZe%20Samagistro.pdf

- Gorgadze, N. (2018). Active Citizenship and Civic Engagement. Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University. https://www.academia.edu/4235006/%E1%83%90%E1%83%A5%E1%83%A2%E1%83%98%E1%83%A3%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98_%E1%83%9B%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A5%E1%83%90%E1%83%9A%E1%83%90%E1%83%A5%E1%83%94%E1%83%9D%E1%83%91%E1%83%90_%E1%83%93%E1%83%90_%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%9B%E1%83%9D%E1

- Government of Georgia. (1995). Constitution of Georgia. Retrieved from Legislative Herald of Georgia: https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/30346?publication=36

- Government of Georgia. (2004). National goals of general education. https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/11098?publication=0

- Grindheim, L. T. (2017). Children as playing citizens. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(4), 624–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1331076

- International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement. (2016). International civic and citizenship education study. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR37147

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2013). The impact of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning environments on achievement. In J. Hattie & E. Anderman (Eds.), International handbook of student achievement (pp. 372–374). Routledge.

- Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Holubec, E. J. (1990). Cooperation in the Classroom. Interaction Book Co.

- Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (2006). Active learning: Cooperation in the college classroom. Interaction Book Co.

- Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Stanne, M. B. (2000). Cooperative learning methods: A meta-analysis. University of Minnesota.

- King, A., Staffieri, A., & Adelgais, A. (1998). Mutual Peer Tutoring: Effects of Structuring Tutorial Interaction to Scaffold Peer Learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 134–152. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ571177

- Maher, F. A., & Tetreault, M. K. (2001). The feminist classroom: Dynamics of gender, race, and privilege. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Malazonia, D., Lobjanidze, S., Lobjanidze, S., Chiabrishvili, N., Giunashvili, Z., & Li, S. (2021). Intercultural competencies of students vs. their civic activities (Case of Georgia). Cogent Education, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1918852

- Malazonia, D., Maglakelidze, S., Lobzhanidze, S., Chiabrishvili, N., & Natsvlishvili, N. (2022). Democratic Citizenship in Schools of Georgia: Challenges and Avenues for Development. Ilia State University Press. https://library.iliauni.edu.ge/ebooks/demokratiuli-moqalaqeoba-saqarthvelos-skolebshi/

- McLaren, P., & Jaramillo, N. E. (2006). Critical pedagogy, latino/a education, and the politics of class struggle. Sage Journals, 6(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708605282815

- Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia. (2011-2016). National Curriculum. https://www.mes.gov.ge/content.php?id=3929

- Ministry of Education and science of Georgia. (2018-2024). National Curriculum. https://www.mes.gov.ge/content.php?id=3929

- Osler, A., & Starkey, H. (2010). Teachers and Human Rights Education. Staffordshire: Trentham Books Ltd.

- Palincsar, A. S., & Herrenkohl, L. R. (2002). Designing collaborative learning contexts. Theory into Practice, 41(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4101_5

- Peterson, A., Durrant, I., & Brendan, B. (2014). Student teachers’ perceptions of their role as civic educators: Evidence from a large higher education institution in England. British Educational Research Journal, 41(2), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3141

- Peterson, A., & Knowles, C. (2009). Active citizenship: A preliminary study into student teacher understandings. Educational Research, 51(1), 39–59. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Active-citizenship%3A-a-preliminary-study-into-Peterson-Knowles/5b6aad68eba7543ea7fc12aee8c8297176f0524c

- Schul, J. E. (2011). Revisiting an old friend: The practice and promise of cooperative learning for the twenty-first century. The Social Studies, 102(2), 88–93. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ915977

- Seyla, B. (2002). The claims of culture: Equality and diversity in the global Era. Princeton University Press.

- Slavin, R. E. (1995). Cooperative learning: Theory, research, and practice. Allyn & Bacon.

- Slavin, R. E. (1996). Research on cooperative learning and achievement: What We Know, What We Need to Know. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 21(1), 43–69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1996.0004

- Stevahn, L., Johnson, D., Johnson, R., Green, K., & Laginski, A. (1997). Effects on high school students of conflict resolution training integrated into English literature. The Journal of Social Psychology, 137(3), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224549709595442

- Stevens, R. J., & Slavin, R. E. (1995). The cooperative elementary school: Effects on students’ achievement, attitudes and social relations. American Educational Research Journal, 32(2), 321–351. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032002321

- Subba, D. (2014). Democratic values and democratic approach in teaching: A perspective 2.12A. American Journal of Educational Research, 2(12A), 37–40. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-2-12A-6

- Thornberg, R., & Elvstrand, H. (2012). Children’s experiences of democracy, participation, and trust in school. International Journal of Educational Research, (53)(44–54). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2011.12.010

- UNESCO. (2014). Global citizenship education: Preparing learners for the challenges of the 21st century. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227729

- Vegas, E., & Winthrop, R. (2020). Global education: How to transform school systems? Reimagining the global economy: Building back better in a post-COVID-19 World. Eric. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED610536

- Vinterek, M. (2010). How to Live Democracy in the Classroom. Education Inquiry, 1(4), 367–380. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1207263

- Young, I. M. (2006). Education in the Context of Structural Injustice: A symposium response. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 38(1), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2006.00177.x

Appendix N

1

Basic provisions of the teacher questionnaire

Appendix N

2

Appendix N

3

Appendix N

4

Appendix N

5

Appendix N

6

Appendix N

7

Appendix N

8

Appendix N

9

Appendix N

10

Appendix N

11

Appendix N

12

Appendix N

13

Appendix N

14

Appendix N

15

Appendix N

16

Appendix N

17

Appendix N

18

Appendix N

19

Appendix N

20