Abstract

The quality of e-content had been identified as one of the major constructs impacting the quality of e-learning and students’ satisfaction. During the time of Covid 19 pandemic, a surge in the development of e-contents had been noted. Moreover, the new scenario also pushed the debate on the quality of e-learning that directly or indirectly included the issue of the quality of e-content. The present study aimed to assess the quality of e-contents prepared during the pandemic period for higher education students in India against the standards laid down by different studies and models of e-content development. A manifest analysis approach as a part of the quantitative content analysis method was employed. The sample size consisted of 60 e-contents from the undergraduate and postgraduate programmes of education discipline. Half (50%) of the e-contents selected from e-content repository and remaining 50% were collected from faculty of HEIs directly. A three-stage selection criterion was formulated to select the e-contents from both sources. In agreement with the three categories of quality assessment (standard, substandard and not-suitable), only 23.3% of e-contents were found of standard quality. Two factors could be attributed mainly to this poor quality of e-contents, one was the lack of training to developers of e-content and the second was the lack of quality control mechanisms for developing e-contents at the institutes of higher education in India.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In India, governments and regulatory bodies have been suggesting teachers and institutions of higher learning to follow a blended mode of instruction. But suggestive tone could not motivate many teachers to develop e-contents and go online. During the COVID-19 imposed lockdown period, teachers had to go online to instruct their students and support them by providing e-content. In many cases, online education was provided by sharing e-contents only without any synchronous support. E-learning which got higher promotion during the pandemic time is still making a pace as a complementary or parallel system of education. Now the general public is also able to visualise the concept of a virtual university. Sharing any kind of e-content can’t insure learning among the students. Therefore, this research paper is indenting to make aware all the stakeholders about the quality parameters of e-content. Such knowledge is expected to help the learners and their guardians to choose a better e-learning system or evaluate the existing one.

1. Introduction

Online learning, or e-learning, had been taken as a panacea during the time of the pandemic (Dhawan, Citation2020), but one of the major challenges was the development of quality e-content. E-content is one of the major factors that determine the quality of e-learning and student satisfaction(AlMulhem, Citation2020). E-content became more vital during the lockdown period of COVID-19, when e-learning was the only option for students (Maatuk et al.,). During the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, the whole world witnessed unprecedented lockdown situations. Educational institutions also witnessed extended closure for the safety of parents, teachers, and learners (Almaiah et al., Citation2020; Maatuk et al., Citation2021; Putri et al., Citation2020; Raza et al., Citation2021). Online education moved from an undervalued option to the only mode of education (Pham & Ho, Citation2020). In India too, this was a challenging time for educational institutions, as most of the institutions were not ready to handle the situation (Lakshmi, Citation2021; Muthuprasad et al., Citation2021). The government of India and concerned educational institutions had begun an initiative to encourage the development of digital content and the use of communication technology. During the COVID-19-induced lockdown, there was a digital push for education.

Prior to the pandemic, the Indian education system did not take serious measures to conduct technology-driven education (Vanlalruati & Tripathi, Citation2019). A few isolated projects like the National Mission on Education through Information and Communication Technology (NMEICT), the Study Webs of Active-Learning for Young Aspiring Minds (SWAYAM), and others were launched and pushed by the Indian government before the COVID-19 pandemic. But there has been a dearth of measures targeted at developing a statewide infrastructure capable of addressing the future demands of the rising education sector. There was also a challenge to mainstreaming a project like SWAYAM (Deivam, Citation2016; Dutta, Citation2016). Before COVID-19, such initiatives did not enjoy significant support in the academic world of India’s traditional universities. Mobile technology and educational telecasting had been reserved for institutions of open and distance education. On the other hand, among the positive aspects of the pre-pandemic developments in the country, the most crucial was the exponential growth in the use of the internet, smartphones, and other related technologies for education, which resulted in a radical growth of online learning to cope with the educational crisis induced by the COVID-19 pandemic (Mathivanan et al., Citation2021). The attitude of stakeholders towards the online mode of education, its capacities, and quality had changed positively. However, there were some challenges for those institutions that had been imparting education only in the traditional face-to-face mode. In the Indian context, developing e-content has been expensive in comparison to classroom materials as far as time consumption and technological resources are concerned (Dutta, Citation2016). However, when considering the time spent by instructors, travel expenses, and attendance at classroom sessions, the delivery cost is significantly less than that of in-person instruction (Soni, Citation2015). E-learning material can be considered a good option as it reaches the masses, especially those who have difficulty attending conventional classrooms due to geographical constraints, personal commitments, and restricted mobility. E-learning or online learning offers learners adequate instructions with a variety of freedoms and multiple options, like self-paced, personalized study, without compromising the quality. Therefore, quality e-content is a reliable tool to minimize the access gap caused by various geographical and economic factors (Chauhan, Citation2017). Nevertheless, for preparing e-content, one must have knowledge and expertise about the basic principles and approaches to e-learning (Eslaminejad et al., Citation2010; Omwenga et al., Citation2004).

During the pandemic, the government of India and state governments were keen on providing education in an online format in order to eliminate the negative effects of the COVID-19 lead crisis, especially after realising its potential since the first wave of COVID-19 (Almaiah et al., Citation2020). As reported by the ministry of education, the Government of India, Ministry of Education (MoE), had allocated ₹818 crores for the advancement of online learning and ₹267 crores for the promotion of online teacher training to mitigate the crisis in school education due to the COVID-19 pandemic (MacEwan, Citation2020). In response to COVID-19 situation, the Government of India also strengthened the existing infrastructure for online learning, such as SWAYAM (a MOOC platform), DIKSHA (an open-source national platform for learners and teachers), and SWAYAM PRABHA (D2H TV channels; UNICEF & UNESCO, Citation2021).

In the year 2019–20, the Government of Uttar Pradesh, which is the largest state in India as far as population is concerned, introduced “Digital Library” (a repository of online contents) for the students of higher education (Almaiah et al., Citation2020). The government instructed the nodal centers to create quality e-contents and train the teachers of higher education institutions (HEIs) in creating e-content for their students in order to implement the Digital Library initiative effectively. Due to the COVID-19 situation, the training programmes could not be implemented properly by most of the nodal centres. Therefore, the participation of teachers in creating quality e-content was limited. A small number of teachers from universities and colleges who possessed some experience or expertise in digital technology could develop a few chunks of e-content. Most of the contents were either in the form of PowerPoint Presentations (PPT) or texts in Portable Document Format (PDF). A plethora of workshops in video editing, collaborative technologies, and developing electronic material were offered at the time. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) were also made available to equip higher education teachers with the trending technology and inspire them to create their own e-content. The process triggered the considerable production of e-content at the local level to cater to online teaching needs. Most of the e-contents created during pandemic situations were not up to the mark, and those e-contents cannot be considered quality products (Dhankar, Citation2021). This had been the situation because of a lack of knowledge of the methodological nuances of e-content development among the teachers and the resulting lack of expertise to develop e-content that could be of some comparable quality in terms of its impact on students’ learning.

2. Literature review

The surge in the development of e-content has been noted during COVID-19 pandemic time. In their systematic review of research works done in the field of e-learning, Kaur et al. (Citation2020) discovered that 28.5% of the works were related to the impact of e-learning and 38% of the works were related to the development of e-content. . A major issue in assessing the quality of e-learning during the pandemic was its mediocre content (Bharad & Makhija, Citation2020). However, generally, in e-learning, course content moved far ahead of its printed counterpart and almost abolished the difference in the concepts of content, environment, and teaching (The Swedish National Agency for Higher Education, Citation2008). Apart from other factors, the quality of e-content can be evaluated on the basis of students’ satisfaction levels. A survey by Pham et al. (Citation2019) on 1232 college students also revealed that e-learning service quality was a second-order construct consisting of e-learning system quality, e-learning instructor, course material quality, e-learning administration, and support service quality. They also reported that e-learning service quality and student satisfaction were positively correlated and directly affected the learners’ loyalty. The Swedish National Agency for Higher Education (Citation2008) found that the main issues concerning quality were related to the selection, sequencing, and quality of course material used and produced on courseware. It was also found that, among the dimensions of e-content quality, the physical design of course, the cognitive design of the course, ease of use, and flexibility had higher e-content quality indices than their cut-off scores (Elango et al., Citation2008; Khojasteh et al., Citation2022). Therefore, these dimensions can be considered key quality parameters along with goals and objectives, course content, content organization, learning strategies, language, resources, evaluation, the look and the feel of course, accessibility, and general information, which were identified by Roy et al. (Citation2020). A study following the structural equation modelling approach was conducted with 784 undergraduate and postgraduate students of Indian and Kingdom of Saudi Arabia universities and it was found that there was a positive and significant relationship between the quality of e-learning and a set of variables (Elumalai et al., Citation2020). The set of variables comprised course content, course design, social support, technical support, administrative support, instructors characteristics, and learners characteristics. A survey with 435 graduate and postgraduate students of Indian universities reported that e-learning content and e-learning quality were significantly correlated with each other, as were e-learning quality and student satisfaction. The survey also reported on the significant role of e-learning quality as a mediator between e-learning content and students’ satisfaction. (Kumar et al., Citation2021). In the technical aspect of e-content design, it was found that the graphics and other pictorial materials used while developing e-content should be designed to depict the course outline, which makes the chapters exciting and informative (Elango et al., Citation2008). As far as the effectiveness of e-content is concerned, it was also found to be more effective than the traditional chalk-and-talk method of teaching in experimental research, though conducted on 60 school students (Mishra et al., Citation2017), and enhances knowledge level and creative thinking (Duraisamy & Surendiran, Citation2011; Mishra et al., Citation2017). it has been clear from reviews that the quality of the content is one of the major factors in assessing the quality of e-learning. While the quality of e-content is dependent on the physical structure of the course, its sequencing, organization, language, and look. Therefore, it can be concluded that while developing any e-content, some key parameters must be seriously considered (Eslaminejad et al., Citation2010).

Most of the studies conducted in the field focused more on the major construct of e-learning. The construct of e-content has been dealt with as one of the contributing factors to the quality of e-learning. The studies focusing on e-content were conducted in different directions, such as the development of e-content, challenges in the development of e-content, and the impact of e-content (Kaur et al., Citation2020). The quality of e-content has been considered as contributing to the satisfaction of e-learning-students. Accordingly, the quality of e-content was assessed in terms of stakeholders’ perceptions (Kumar et al., Citation2021). Some other studies tried to find out the parameters of quality e-content (Al-Alwani, Citation2014), but not the quality of e-content. As a result, the need for a study focusing primarily on the quality of e-content had emerged. A methodological gap was also identified by the authors, so this study was planned to follow a content analysis approach aligned with the qualitative research paradigm.

3. Research objectives of the study

The research aimed to achieve the following objectives: -

To prepare a checklist of standards for developing an e-content.

To assess the quality of e-contents prepared during the pandemic period for higher education students in India with the checklist prepared.

To compare the quality of e-content materials prepared primarily by faculty members of Higher Education Institutions (HEI) for their teaching and e-content materials managed by the government-controlled digital content repository (digital library).

4. Significance of the study

The study may act as an eye opener for the government and regulatory authorities, making them realise the need of teacher training for e-content development and formulate a relevant policy for that. The study can help to guide the policy of institutional regulatory mechanisms for e-content quality management. Moreover, the study intends to make the stakeholders aware of the quality parameters of e-content, which will help them in their decision making. Further, this study is contributing to the vast literature in the area of e-learning. It is one of the few that dealt directly with a single factor of quality e-learning, i.e., quality e-content.

5. Limitation of study

Though the study aims to depict a picture of the quality of e-contents being prepared by higher education faculty members, the study still has its own limitations, like the sample (e-contents) were prepared by teachers who were in service in the state of Uttar Pradesh (a northern state of India) only. The e-contents were selected from only a one discipline, i.e., “education”.

6. Methodology

6.1. Method

A manifest analysis strategy was utilized as part of the quantitative content analysis method because it focuses on facts that are readily viewable to both researchers and coders who aid with their studies without the requirement to detect purpose or find deeper meaning. It requires minimal training. Here, frequency counts are employed to comprehend a phenomenon, which displays a superficial analysis and assumes that the data contain objective truths that require minimal interpretation. The frequency of a target (i.e., category, code, or set of words) within the text is used to determine its prevalence. Quantitative content analysis always represents a positivist manifest content analysis, in which the nature of truth is held to be objective, observable, and quantifiable (Kleinheksel et al., Citation2020).

6.2. Sample

There are no established criteria for the sample size while performing the content analysis (Bengtsson, Citation2016). In the present study, the sample size consisted of 60 e-contents from the education discipline. Out of these 60 e-contents, 30 were collected from faculty members at different HEIs, which were prepared for their teaching purposes. The remaining 30 e-contents were collected from the government-controlled digital content repository (digital library) of Uttar Pradesh, India. E-contents of digital library were in public forum and can be used for educational purpose; however no meddling was done in any e-content in any manner. Faculty members of HEIs were assured while taking their consent that the e-content would be solely used for research purposes and that no e-content or its parts would be altered or used for some other purpose. Identity of the faculty members who contributed their e-contents was kept confidential from each other. The rationale behind selecting two types of e-contents was that the e-contents developed by HEI faculty members did not undergo any quality checking, while e-contents from the digital repository were declared to undergo three-stage quality checking.Footnote1 The e-contents in the sample can be categorized further into three categories (Table ).

Table 1. Distribution of E-contents in Sample (N = 60)

As per Table , the study included e-contents from only three types of programmes, all of which fall under the broader area of the discipline of education. The education discipline’s e-contents were chosen solely because the researchers are from the same field and have a comparatively deeper understanding of the issue. To select e-contents from the digital repository, a selection criteria was developed, and e-contents were selected accordingly from the digital repository (refer to Table ). The repository had a total of 1339 e-contents related to the three programmes. The selection criteria were as follows: (a) only first-year courses will be considered; (b) only unique topics will be covered; and (c) every e-content must have been created by a unique creator.

Table 2. Selection criterion of E-contents and stage wise sample procedure from digital library

Although the sample does not necessarily represent the e-content population in higher education in India, being the part of the total population, it can still make the picture clearer. Nonetheless, the teachers from the education discipline are supposed to go through the theory and practice of curriculum design so the quality of e-contents from education may help to infer the quality of e-contents across the different disciplines. In the case of e-contents obtained from faculty members of HEIs, 13 e-contents from the Bachelor of Arts (B. A.) in Education programme, 8 from the Bachelor of Education (B. Ed.) programme and 9 from the Master of Education (M. Ed.) programme were collected after selecting the e-contents from the repository. E-contents obtained from faculty members of HEIs were collected purposively following the selection criteria as mentioned in Table . Overall, 34 e-contents were selected from undergraduate courses (21 from faculty members at HEIs and 13 from the digital library) and 26 from postgraduate c course.

6.3. Participants (Evaluators)

Forty (40) subject experts from different Indian universities belonging to the discipline of education, who had experience in e-content development and delivery, were contacted over the telephone. Only twelve (12) of them gave their consent and agreed to become an evaluator in the study. Identity of the evaluators were kept confidential from each other. Including the three researchers (authors), a team of fifteen (15) evaluators was constituted to assess the quality of e-content materials. All three authors also have experience in the development and delivery of e-contents at their respective institutions as well as at national agencies like the National Institute of Open Schooling, the National Council for Teacher Education, etc. Every participant was given only 20 e-contents so that every e-content was evaluated by eight evaluators. Proper guidelines, selected e-contents, and an assessment checklist for assessing the quality of e-content were communicated with the experts beforehand through email.

6.4. Instrumentation

Based on the existing literature reviewed, it was revealed that the quality of e-content and student satisfaction were common factors that impacted the success of e-learning. There were two simple ways to assess the quality of e-contents. First was the empirical process of finding out the perception and opinion of stakeholders, and second was the analytical process based on the established models of e-content development. Such models do work as a standard for assessment. Since the paper followed the second approach to assess the quality of e-contents, analysis of different existing models of e-content development to prepare a checklist had become inevitable. A checklist for the assessment of e-content material was developed based on the Stratified Objective-driven Approach (Omwenga et al., Citation2010), the Learning Object-based Content Approach (Kumar & Srivatsa, Citation2012), Merrill’s Model (Malliga et al., Citation2017), Gilly Salman’s Five-stage Model, and the Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation and Evaluation Model (Patel et al., Citation2018). The checklist consisted of five basic dimensions of quality e-content (Table ). Further, the dimensions consisted of criteria, which totaled thirty-two (32) under the five dimensions (Table ). Preparation of Checklist fulfils the first objective of the study. Checklist confirmed the presence of criteria in the e-content material. The evaluators were given three options (standard, sub-standard, and not suitable) for the overall categorization of the e-content. The evaluators provided the overall category purely based on their perception of the e-content they were assessing. A provision for comment against each criterion was also made for evaluators to give further information on that criterion.

Table 3. Description of Dimensions and Criteria in the Checklist

To establish the validity of the checklist, it was presented to four external experts specializing in online teaching-learning to ensure content validity. Data from seven people (four external experts and three researchers themselves) was collected. All the criteria and dimensions were found to have more than 80% agreement among the experts, and finally, Fleiss’ Kappa statistics was used to establish reliability among the experts. Fleiss’ Kappa value was 0.8, which was found to be in substantial agreement.

6.5. The procedure of data collection

The faculty members of the education departments of HEIs from Uttar Pradesh, the most populous state, were contacted via email to solicit their contribution to the study by sharing their valuable teaching materials. In total, 80 faculty members were contacted, and 55 of them consented to offer their resources; however, by the time the research began, only 32 had sent their teaching resources in the form of e-content. Two e-contents were eliminated to simplify the calculation for the analysis. In the case of the digital repository, the process of selection of e-content has already been mentioned in section 4.2, i.e., the sample (refer to Table ).

6.6. Data analysis

Data collected on the quality dimensions of e-contents through the checklist were presented using frequency and percentage for each criterion. The comment part against each criterion, wherever that was necessary, was used to describe the e-content qualitatively. Inter-rater reliability of the data was also established using Fleiss’ Kappa statistics. Microsoft Excel 2007 was used to analyse the data.

7. Results

7.1 Overall quality of e-content

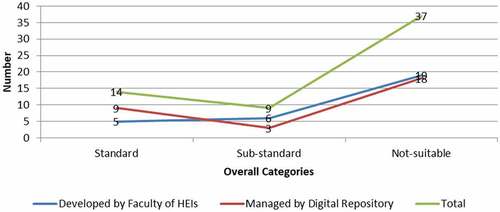

According to the purpose of the study, all evaluators were asked to categorize each e-content into three categories (standard, sub-standard, and not suitable) for the overall quality of the e-content. It was found that only 23.3% of e-contents were of standard quality, 15% were of sub-standard quality, and the majority of e-contents (61.6%) were found not suitable against the set criteria (Figure ). The coefficient of agreement using Fleiss Kappa among the raters was found to be 0.76 which indicates substantial agreement.

7.2. E-content structure

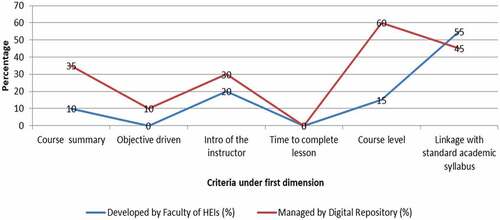

While working on different dimensions of quality e-content, the data collected through a checklist was presented dimension-wise in line with Table . Assessing the first dimension, i.e., e-content structure (Figure ), it was found that the number of e-contents developed by the faculty members of HEIs (henceforth e-content from HEIs) having a course summary was inadequate (10%) as compared to the e-contents collected from the digital repository (henceforth e-contents from the repository) (35%). None of the e-contents from HEIs were objective-driven, while 10% of e-contents from the repository were objective- driven. All the e-contents were very similar in providing the introduction of instructor or creator (20% from HEIs and 30% from the repository). None of the e-content was mentioning the expected time to complete the lesson/topic. E-contents from repository have provided the academic level of the course in the majority of cases (60%), while e-contents from HEIs had failed comparatively to do so (15%). As far as the linkage of e-content with the syllabus is a concern, e-contents from HEIs had shown more linkage (55%) than e-contents from the repository (45%).

7.3. Nature of the e-content

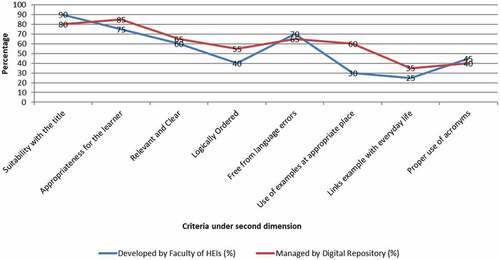

The nature of the e-contents (Figure ) reveals that all of the e-contents were almost identical in terms of content suitability with the title. It was 90% in the case of e-contents from the repository and 80% in the case of e-contents from HEIs. Here “suitability” with the title denotes the matching of the content with the title given to that particular topic by the creator. The suitability of the title had been assessed in terms of alignment of the title with the content given in the same e-content (file), irrespective of the title given in the standard academic syllabus (a criterion under dimension 1). The appropriateness of content for the learner was 85% for e-contents from the repository and 75% for e-contents from HEIs. The relevancy and clarity of e-contents ranged from 65% in e-contents from the repository to 60% in e-contents from HEIs. Only 40% of e-contents from HEIs had logically arranged content, while only 55% of e-contents from the repository had logically arranged content. A higher percentage of e-contents from both sources were free from language and grammatical errors. Even though language errors of 30% to 35% should be considered a serious flaw in a serious e-content development effort. Only 30% of e-contents from HEIs had examples at appropriate places, whereas e-contents from the repository were comparatively much better (60%). The majority of the e-contents from both sources failed to link the example with everyday life. Only 25% from HEIs and 35% from the repository could meet this criterion. Total e-contents of 40% from the repository and 45% from HEIs demonstrate proper acronym usage.

7.4. Presentation of e-content

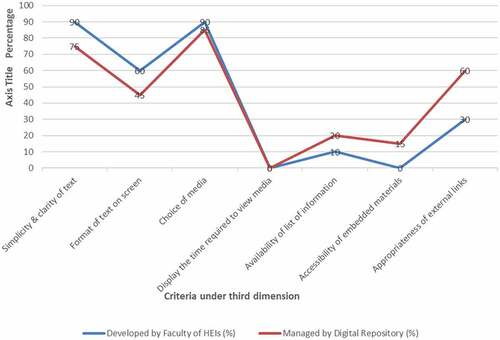

As far as the presentation of e-content is concerned (Figure ), it was found that almost all e-contents from both sources (90% from HEIs and 75% from the repository) used simple and clear text. The format of the text on screen had been found 60% appropriate in the case of e-contents from HEIs, and only 45% of e-contents from the repository were appropriate on this criterion. On the criterion of choice of media, 90% of the e-contents from HEIs and 85% of the e-contents from the repository had appropriate media for displaying designed content. None of the e-content from the either source had mentioned the time required to view the media. A list of information was also not available in most of the e-contents. Only 10% of e-contents from HEIs and 20% from the repository could meet this criterion. None of the e-content developed by the faculty of HEIs included provisions for the accessibility of embedded materials, whereas only 15% of the e-contents from the repository did. Only 30% of e-contents from HEIs had appropriate external links, whereas 60% of e-contents were found appropriate on this point. Though the texts were clear and the media selection was somehow appropriate, the e-contents from both sources lagged far behind in other factors.

7.5. Presentation of e-content

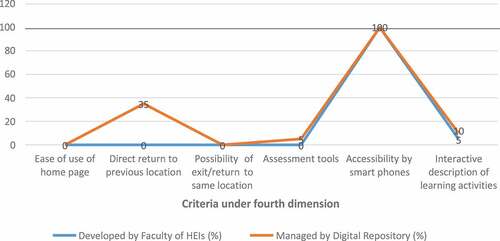

The e-content interface quality (Figure ) shows that no single e-content from both sources had ease of use of the homepage and the ability to exit or return to the exact location. However, smartphones could access all e-content (100%).All the e-contents (100%) from HEIs and 65% from the repository were without a provision for direct return to their previous location. Only 5% of the e-content in the repository came with an assessment tool, whereas none from HEIs had this provision. As far as the interactive description of learning activities is concerned, 5% of e-contents from HEIs and 10% of e-contents from the repository had that facility.

7.6. TechnicaliInformation

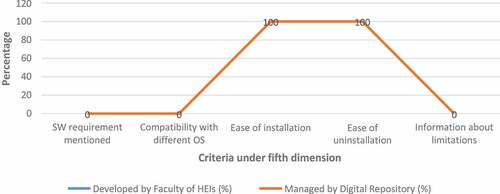

When it came to the provision of technical information, the e-contents from the two sources were identical (Figure ). None of the e-contents mentioned software requirements, and compatibility with operating system. Also, in the case of e-content from both sources, there was no information about any limitations regarding e-content. On the criterion of ease of installation, all e-contents (100%) were found to be suitable. Similarly, on the point of ease of uninstallation, all e-contents (100%) from both sources were found to be appropriate.

8. Discussion

At the time of drafting this paper in June 2021, all the educational institutions in India had been closed for more than a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic and state-imposed regulations. As a result, the education sector witnessed a sudden increase in the number of e-contents. Those were to be provided free of cost to the students or prospective students. This growth in the number of e-contents was exponential with the time duration of waves of COVID-19. The vast majority of the e-content produced during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly by teachers in face-to-face mode institutions, was pressure-driven and produced unrestrained, unsupervised e-content. Such explosive production (Wadia et al., Citation2020, May 17) of e-contents should be subjected to channelization and optimization. The creation of so many e-contents by teachers had increased the problem of explosive e-content production on many folds. It has also been demonstrated that, in some Indian universities, there is no regulatory system to monitor the quality of e-content (Jena, Citation2020)

The application of the adjective “quality” to content in the direction of the government was itself a parameter, but in the study, quality parameters were selected based on the previous studies done in the field of e-content quality (Elumalai et al., Citation2020; Roy et al., Citation2020). The study revealed that most of the e-contents were either not suitable or substandard as far as quality is concerned (also in Bharad & Makhija, Citation2020). Most of the e-contents did not fulfil the minimum requirements in terms of the key parameters to be considered e-content (Roy et al., Citation2020). Whereas a true e-content could be more effective than the face to face teaching (Mishra et al., Citation2017;). Teachers simply followed the administrative directions to upload the e-content for the students without knowing its concept and technicalities of developing an appropriate e-content. All those were rather pieces of information that were presented before students without any clear instructions to achieve the objectives. Video e-contents looked like simple lectures without any specified aim. The video lectures were prepared for the teachers’ personal YouTube channels, so no such introductions regarding the target audience were specified. More than half of the e-contents (35) were in Microsoft PowerPoint, not providing comprehensive content according to the file formats. Whereas e-contents are, in principle, expected to be more informative and exciting (Elango et al., Citation2008), other e-contents were like class notes with insufficient content-related information. Teachers should be equipped and trained through comprehensive training programs covering the theoretical underpinning of e-content development, models, pedagogy, and quality concerns of e-learning with the software which can be used to create an e-content (Khojasteh et al., Citation2022).

As mentioned earlier, several online training workshops were conducted during the institutional lockdown—most of such programs focused on introductions to software and hosting platforms. At the same time, teachers need to know more about the selection, sequencing, and designing of e-content. Besides, it needs to make content developers aware of sustaining interaction with students, which is the essence of teaching. The limitations with the teachers in developing e-content might have been the significant factor. Due to limitations with the teachers, the University Grants Commission (UGC) i.e., the statutory body set up by the Department of Higher Education, Ministry of Education, Government of India in accordance to the UGC Act 1956 which is charged with coordination, determination and maintenance of standards of higher education could not implement many policies at the anticipated level, such as the credit transfer system and MOOCs (Massive Open Online Course) on twenty percentage credits of the programmes in higher education which were to be implemented before the COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless of the fact, UGC has recently increased its target of twenty percent to forty percent of the program to be acquired by e- learning platforms (UGC, Citation2021).

9. Conclusion

The study was intended to assess the quality of e-contents developed during the COVID-19 pandemic to address the educational crisis. It was observed that most of such e-contents did not fit on five dimensions which were divided into 32 criteria of development of e-content. The dimensions and criteria may be used for the assessment of e-contents of other disciplines as well. The same can be tested in other subjects as well to know the quality of e-contents in other disciplines. This will contribute to make scenario clearer in Indian higher education system. Here in the study, it can be inferred from the findings that that the majority of e-contents were of poor quality as assessed against established models of instructional designs. Two factors could be attributed mainly to this poor quality of e-contents. One was the lack of training to developers of e-contents and the lack of quality control mechanisms for developing e-contents in India. Additionally, the pressure on the teachers to develop e-contents during pandemic within a brief period and make it available to students can also be a significant factor. It indicates an urgent need for training teachers of higher education institutions in India on developing e-content(similar to Kebritchi et al., Citation2017), establishment of a quality control mechanism for evaluating e-content before making it available to learners, and making teachers develop e-content with pleasure and not under pressure. Teachers should be competent to develop e-content because it affects eLearning quality (Elumalai et al., Citation2020; Kumar et al., Citation2021; Pham et al., Citation2019). Nonetheless, India’s National Educational Policy 2020 also envisions the virtual universities, quality e-content available in regional languages. Besides, provision of interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary education will also demand more and more online courses in future(Government of Inida, Citation2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Surjoday Bhattacharya

Surjoday Bhattacharya has completed his doctoral degree from Banaras Hindu University, India. He has a keen interest in the field of education technology, e-learning and educational statistics. He has been a part of several small projects on e-learning, digital citizenship and MOOCs. Currently, he is working on a project on the development of MOOC on statistics for undergraduate social science students. Dr Krishna Kant Tripathi has expertise in language education, teacher education, content development and e-learning. Dr Akhilesh Kumar works in the field of teachers’ training in general and special education as well. He worked on the effective use of computers for intellectually disabled students. The present project was undertaken amid the ongoing debate on quality e-content which grew greater during the COVID-19 lockdown. The work is expected to be helpful to the developer, user and producers of e-content.

Notes

1. As per the government order, College department, University department and Nodal University will ensure the quality of the e-contents to be uploaded: https://heecontent.upsdc.gov.in/ViewNotice.aspx?NoticeID=4B1QmJBAsAaLln5kYbI%2bJA%3d%3d

References

- Al-Alwani, A. (2014). Evaluation criterion for quality assessment of E-learning content. E-Learning and Digital Media, 11(6), 532–15. https://doi.org/10.2304/ELEA.2014.11.6.532

- Almaiah, M. A., Al-Khasawneh, A., & Althunibat, A. (2020). Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Education and Information Technologies, 25(6), 5261–5280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10219-y

- AlMulhem, A. (2020). Investigating the effects of quality factors and organizational factors on university students’ satisfaction of e-learning system quality. Cogent Education, 7, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1787004

- Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

- Bharad, B. H., & Makhija, H. L. (2020). A review on efficacy of e-learning during pandemic crisis. Gap Interdisciplinarities - A Global Journal of Interdisciplinary, Studies, 3(4), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.47968/gapin.34001

- Chauhan, J. (2017). An overview of MOOC in India. International Journal of Computer Trends and Technology, 49(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.14445/22312803/IJCTT-V49P117

- Deivam, M. (2016). Information and communication technology initiatives in India. International Journal of Advanced Scientific Research, 1(2), 24–26. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303017315_Information_and_communication_technology_initiatives_in_India

- Dhankar, R. (2021). E-learning in India, a case of bad education. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/e-learning-in-india-a-case-of-bad- education/article32672071.ece

- Dhawan, S. (2020). Online Learning: A Panacea in the Time of COVID-19 Crisis. Journal of Education Technology systems, 49(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239520934018

- Duraisamy, K., & Surendiran, R. (2011). Impacts of e-content. International Journal of Computer Trends and Technology-March to April Issue, 2231–2803. https://doi.org/10.14445/22312803/IJCTT-V70I3P101

- Dutta, I. (2016). Open Educational Resources (OER): Opportunities and challenges for Indian higher education. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 17, 2. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.34669

- Elango, R., Gudep, V. K., & Selvam, M. (2008). Quality of e-learning: An analysis based on e- learner’s perception of e-learning. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 6(1), 31–44. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1098757.pdf

- Elumalai, K. V., Sankar, J. P., Kalaichelvi, R., John, J. A., Menon, N., Salem, M., & Alqahtani, M. (2020). Facors affecting the quality of e-learning during the COVID 19 pandemic from the perspective of higher education students. Journal of Information Technology Education:Research, 19, 731–753. https://doi.org/10.28945/4628

- Eslaminejad, T., Masood, M., & Ngah, N. A. (2010). Assessment of instructors’ readiness for implementing e-learning in continuing medical education in Iran. Medical Teacher, 32(10), e407–e412. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.496006

- Government of Inida. (2020). National Education Policy 2020. https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf

- Jena, P. K. (2020). Online learning during lockdown period for covid-19 in India. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research (IJMER), (9). https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/qu38b/download

- Kaur, I., Jyoti, M., & Raskirat, M. (2020). Perspective of e-content: A systematic review. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(6), 2698–2715. http://sersc.org/journals/index.php/IJAST/article/view/12187

- Kebritchi, M., Lipschuetz, A., & Santiague, L. (2017). Issues and Challenges for Teaching Successful Online Courses in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239516661713, 46(1), 4–29.

- Khojasteh, L., Karimian, Z., Farahmandi, A. Y., Nasiri, E., & Salehi, N. (2022). E-content development of English language courses during COVID-19. a Comprehensive Analysis of Students’ Satisfaction. Journal of Computers in Education, (2022, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40692-022-00224-0

- Kleinheksel, A. J., Rockich-Winston, N., Tawfik, H., & Wyatt, T. R. (2020). Demystifying content analysis. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(1), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.5688/AJPE7113

- Kumar, P., Saxena, C., & Baber, H. (2021). Learner-content interaction in e-learning- the moderating role of perceived harm of COVID-19 in assessing the satisfaction of learners. Smart Learning Environments, 8(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-021-00149-8

- Kumar, J. S., & Srivatsa, S. K. (2012). Component-Based Approach for Technically Feasible and Economically Viable E-Content Design and Development, 5, 264–265. https://www.ijsce.org/wp-content/uploads/papers/v2i5/E1058102512.pdf

- Lakshmi, Y. V. (2021). eLearning Readiness of Higher Education Faculty Members. Indian Journal of Educational Technology, 3(2), 121–138. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?Abstract_id=3970655

- Maatuk, A. M., Elberkawi, E. K., Aljawarneh, S., Rashaideh, H., & Alharbi, H. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and E-learning: Challenges and opportunities from the perspective of students and instructors. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-021-09274-2

- MacEwan, G. (2020 September 14). Education ministry allots rs. 818 crore for promotion of online learning, rs. 267 cr for online teacher training. Jagran Josh. https://www.jagranjosh.com/current-affairs/government-allocates-over-rs-818-crores- to topromoteonlinelearningtomitigateeffectofcovid1919pandemic1600332412116003324121

- Malliga, P., Venkatesh, N., & Sambanthan, T. G. (2017). Problem centric instructional approach for computer science & engineering e-content development. International Journal of Computer and Communication Technology, 2, 7–11. https://doi.org/10.47893/ijcct.2017.1391

- Mathivanan, S. K., Jayagopal, P., Ahmed, S., Manivannan, S. S., Kumar, P. J., Raja, K. T., and Prasad, R. G. (2021). Adoption of e-learning during lockdown in India. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/2Fs13198-021-01072-4

- Mishra, U., Patel, S. H., Doshi, K. (2017). E-content: An effective tool for teaching and learning in a contemporary education system.International Journal of Advance Research and Innovative Ideas in Education, 2 (1). https://ijariie.com/AdminUploadPdf/E__CONTENT__AN_EFFECTIVE_TOOL_FOR_TEACHING_AND_LEARNING_IN_A_CONTEMPORARY_EDUCATION_SYSTEM_C_1289.pdf

- Muthuprasad, T., Aiswarya, S., Aditya, K. S., & Jha, G. K. (2021). Students’ perception and preference for online education in India during COVID −19 pandemic. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 3(1), 100101. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSAHO.2020.100101

- News, L. I. S. (2020 October 28). UP government starts Uttar Pradesh higher education digital library. Library and Information Science Portal. https://www.lisportal.com/en/lis-result/5768-up-government-starts-uttar-pradesh-higher- education-digital–library

- Omwenga, E., Waema, T., Eisendrath, G. P., & Libotton, A. (2010). A structured e-content development framework using a stratified objectives-driven methodology. African Journal of Science and Technology, 6(1), 45–50. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajst.v6i1.55168

- Omwenga, E., Waema, T., & Wagacha, P. (2004). A model for introducing and implementing e-learning for delivery of educational content within the African context. African Journal of Sciences and Technology, 5(1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajst.v5i1.15317

- Patel, S. R., Margolies, P. J., Covell, N. H., Lipscomb, C., & Dixon, L. B. (2018). Using instructional design, analyze, design, develop, implement, and evaluate, to develop e-learning modules to disseminate supported employment for community behavioral health treatment programs in New York State. Frontiers in Public Health, 6(May). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00113

- Pham, -H.-H., & Ho, T. T. H. (2020). Toward a ‘new normal’ with e-learning in Vietnamese higher education during the post COVID-19 pandemic. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(7), 1327–1331. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1823945

- Pham, L., Limbu, Y. B., Bui, T. K., Nguyen, H. T., & Pham, H. T. (2019). Does e-learning service quality influence e-learning student satisfaction and loyalty? evidence from Vietnam. International Journal of Education Technology in Higher Education, 16(7). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0136-3

- Putri, R. S., Purwanto, A., Pramono, R., Asbari, M., Wijayanti, L. M., & Hyun, C. C. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on online home learning: An explorative study of primary schools in Indonesia. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29, 4809–4818.

- Raza, S. A., Qazi, W., Khan, K. A., & Salam, J. (2021). Social isolation and acceptance of the learning management system (LMS) in the time of COVID-19 Pandemic: An Expansion of the UTAUT Model. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 59(2), 183–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633120960421

- Roy, S., Bhattacharya, S., & Das, P. (2020). Identification of e-learning quality parameters in Indian context to make it more effective and acceptable. Proceedings on Engineering Sciences, 2(3), 2. https://doi.org/10.24874/PES0202.011

- Soni, A. G. (2015). eLearning Insights: “Do you really need elearning?”. eLearning Industry Retrieved July 22, 2021, https://elearningindustry.com/elearning-insights-really- need needelearning

- Swedish National Agency for Higher Education (2008). E-learning quality Aspects and criteria for evaluation of e-learning in higher education ( Report 2008: 11R). https://www.divaportal.org/smash/get/diva2:283764/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- UGC. (2021). Public notice (DO No. 1-9/2020(CPP-II). University Grants Commission, Ministery of Education, Government of India. https://www.ugc.ac.in/pdfnews/7782448_Public-Notice.pdf

- UNICEF & UNESCO. (2021). India case study: Situation Analysis on the Effects of and Responses to COVID-19 on the Education Sector in Asia. https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/16511/file/India Case Study.pdf

- Vanlalruati, V., & Tripathi, K. K. (2019). A study on perception and uses of e-learning technologies among the students of Mizoram University. Mizoram Education Journal, 5(2), 67–78. http://www.mizedujournal.com/images/resources/v5/v5n2.pdf

- Wadia, L. C., Murthy, S. V., Shamsu, S., & Fernandes, A. (2020, May 17). COVID-19 and the explosion of online learning: is India ready for this digital transformation? Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/covid-19-and-the-explosion-of-online-learning-is-india-ready-for-this-digital-transformation-66269/