Abstract

The purpose of this case study was to understand what kinds of emotions university teachers experience in teaching, how these emotions influence the way the teachers experience their pedagogical competency and being and developing as a teacher, and how they reflect on their teaching and teaching-related emotions. Data were collected via semi-structured interviews with nine university teachers participating in an educational development project. Our results show that the teachers experienced positive, negative, and mixed teaching-related emotions and that these emotions influenced their experience of themselves as teachers and of their pedagogical competency. All teachers reflected on their teaching experiences, and most also shared and reflected on their teaching-related emotions with others. Social reflection can be a powerful tool in developing as a teacher, as it enables a personal evaluation and interpretation of teaching-related emotions and experiences. Higher education institutions should offer supportive environments for academic personnel, encouraging social reflection and providing opportunities for sharing teaching-related emotions. We found that an educational development project, in addition to more traditional staff training programs, can be a fruitful context for teachers’ pedagogical development, since it can provide opportunities for joint discussions on the application and development of pedagogical perspectives.

1. Introduction

Research focused on teacher development has often been directed toward so-called “rational factors” such as teacher knowledge, skills, and competencies (Chen, Citation2016; Duţă, G. Pânişoară, and I. O. Pânişoară Citation2014; Pekkarinen & Hirsto, Citation2017; Su et al., Citation2012). However, over the last decade, the importance of emotions in developing as a university teacher and in relation to teachers’ interest in developing their teaching practice and pedagogical competency has attracted increasing interest among researchers (e.g., Isopahkala-Bouret, Citation2008; Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020; Quinlan, Citation2016; Stupnisky et al., Citation2016; Thies & Kordts-Freudinger, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). Research conducted on emotional experiences in teaching at the secondary education level has revealed that these experiences influence teacher development (Jakhelln, Citation2011). However, in the higher education (HE) context, research on emotions in teaching and, in particular, the influence of emotions on being and developing as a teacher is still scarce (e.g., Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014). In addition to emotions, it has been recognized that social relations and significant networks with peers and colleagues influence how teachers create and maintain their understanding of teaching and learning (Pyörälä et al., Citation2015, Citation2021; Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2009) as well as how they contribute to the development of university teachers’ pedagogical competency (Pekkarinen & Hirsto, Citation2017; Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020).

In this case study, we aim to understand what kinds of emotions university teachers experience in teaching and how these emotions influence the way the teachers experience their pedagogical competency and their being and developing as a teacher. We use the concept of pedagogical competency in this study to refer to “university teachers’ conceptions, reflections, evaluations, and experienced confidence as teachers” (cf., Pekkarinen & Hirsto, Citation2017, 739; Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020, 15). As can be seen from the definition, experience and interpretation are at the core of pedagogical competency. Emotions, in turn, play a central role in the emergence and interpretation of an experience, and thus emotions can also influence how one’s own pedagogical competency is experienced. This definition of pedagogical competency is based on the interpretative research tradition that also considers the social aspect. The interpretative tradition approaches competency as a social construction that results from the interaction between the individual and the environment in certain contexts, thereby suggesting that skills and competencies are based on, and formed in relation to, a person’s perceptions and understanding of their work (Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020; cf., also Sandberg, Citation2000). Furthermore, pedagogical competency is one aspect of university teachers’ expertise, which is recognized as an experiential phenomenon (Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020).

As social relations and significant networks have been found to be important in being and developing as a teacher, we are also interested in exploring how university teachers reflect on their teaching and teaching-related emotions. Research in the HE teaching context has mainly approached emotions from psychological perspectives in which emotions are seen as private and internal to individuals, and need to be self-regulated (e.g., Postareff & Lindblom-Ylänne, Citation2011; Quinlan, Citation2016). Some researchers argue that individual emotions can also be group-based, meaning that emotions arise in situations which are perceived by the individual to be relevant to a group based on their membership in that group (Kessler & Hollbach, Citation2005; Smith & Mackie, Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2007). In addition to individual emotions, it is argued that there are collective and shared emotions, i.e., emotions that emerge from emotional dynamics among individuals who have gathered as a group and are responding to the same situation (Salmela, Citation2012). Although the social aspect is central in this study, emotions are not approached as collective, shared, or group-based emotions, but rather as individually experienced emotions and feelings related to teaching and developing as a teacher. However, we do consider that individual emotions can be discussed and shared with others. In this study, we pose the following research questions:

RQ1. What kinds of emotions do university teachers experience in teaching?

RQ2. How do the teaching-related emotions influence the way the teachers experience their pedagogical competency and their being and developing as a teacher?

RQ3. How do university teachers reflect on their teaching and teaching-related emotions?

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Emotions in university teaching

The affective dimension and emotions in university teaching and learning have garnered increased interest during recent years. Studies in the higher education context have focused on, for example, emotions in university teaching (Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014; Löfström & Nevgi, Citation2014; Trigwell, Citation2012), teachers’ and university academics’ emotions (Frenzel, Citation2014; Frenzel et al., Citation2016; Thies & Kordts-Freudinger, Citation2019b), emotion regulations strategies (Kordts-Freudinger, Citation2017), the role of emotions in experiencing confidence in university teaching and as a teacher and in developing as a teacher (e.g., Day & Leitch, Citation2001; Postareff & Lindblom-Ylänne, Citation2011), new higher education faculty members’ emotions (Stupnisky et al., Citation2016), academic staffs’ positive emotions through work domains (Thies & Kordts-Freudinger, Citation2019a), and emotions related to assessment practices among teachers (Myyry et al., Citation2019) and students (Peterson et al., Citation2015).

Many of the studies regarding emotions in the higher education context follow either the Appraisal Theory (e.g., Frenzel, Citation2014; Frenzel et al., Citation2016; Moors et al., Citation2013) or the Control-Value Theory of achievement emotions (CVT; e.g., Kordts-Freudinger, Citation2017; Löfström & Nevgi, Citation2014; Myyry et al., Citation2019; Peterson et al., Citation2015; Stupnisky et al., Citation2016; Thies & Kordts-Freudinger, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). In Appraisal Theory, emotions are interpreted as individuals’ subjective cognitive judgements or appraisals of various situations and events and are not seen caused by the situations and events per se (Moors et al., Citation2013). The CVT, on the other hand, combines principles from expectancy-value, attributional, and control approaches to achievement emotions, and defines achievement emotions as emotions related to achievement activities or their outcomes (Pekrun, Citation2006; Pekrun et al., Citation2007, Citation2017). Achievement can be defined as the quality of activities or their outcomes, as evaluated in relation to some standard of succeeding. For example, in educational settings, achievement activities can refer to tests and assignments, and achievement outcomes to achieved grades and scores (Myyry et al., Citation2019; Pekrun et al., Citation2007).

The CVT (Pekrun, Citation2006; see also, Pekrun et al., Citation2007, Citation2017) is a three-dimensional model differentiating emotions according to object focus (whether the focus is on activity or on outcome), valence (positive vs. negative, pleasant vs. unpleasant) and to the degree of activation implied (activating vs. deactivating). The basic assumption in CVT is that appraisals of control and value are central to the arousal of the achievement emotions, meaning that the appraised controllability and the valuation of the activity as positive or negative influence the kinds of emotions experienced. According to Pekrun and colleagues (Pekrun et al., Citation2007; see also Citation2017), positive emotions, such as enjoyment, joy, hope, pride, and gratitude, are considered activating, apart from those experienced after achieving one’s goals—such as relaxation, contentment, and relief—which are considered deactivating. Negative emotions, such as anger, frustration, anxiety, and shame, are considered activating, that is, they are likely to increase the effort to improve, whereas emotions such as boredom, sadness, disappointment, and hopelessness are considered deactivating—i.e., they are likely to decrease the effort to improve. Furthermore, if the controllability of the activity is high and it is positively valued, enjoyment will follow, whereas, when the controllability is high, but the activity is negatively valued, negative emotions such as anger are experienced. In contrast, if the activity is valued, but the controllability is low, negative emotions such as frustration can emerge.

In this study, we use the CVT as a starting point to explore emotions in teaching. As teaching is a goal-oriented activity, the teachers may experience varying emotions depending on how they perceive their success in teaching. The CVT offers versatile views on emotions, and it has also been applied successfully in studies in the higher education context (e.g., Kordts-Freudinger, Citation2017; Löfström & Nevgi, Citation2014; Myyry et al., Citation2019). In his commentary article, Pekrun (Citation2019) reviewed several studies applying the CVT in exploring emotions in teaching in the higher education context. Based on the findings, he suggests that the CVT may be a useful and well-applicable tool in explaining both students’ and academics’ emotions. However, Pekrun (Citation2019) also points out that the CVT has often been used based on self-report measures in correlational between-person designs and should be complemented, for example, with experimental research that better considers the broader institutional and socio-cultural context of emotions. In this study, we explore the emotions in teaching and also consider the social aspect.

2.2. Reflection and social reflection in developing as a teacher

In general, reflection is conceptualized as a cognitive human function associated with meta-cognition. Reflection thus refers to an individual’s knowledge of their own mental functions and their ability to observe and evaluate their own thoughts and actions (e.g., Mälkki, Citation2011). Reflection has been recognized as a prerequisite for developing as an expert and as a teacher by many researchers (e.g., Brookfield, Citation1995; Hatton & Smith, Citation1995; McAlpine et al., Citation1999; Schön, Citation1983; Tynjälä et al., Citation2016). However, reflection is not a self-evident tool that automatically creates changes in teachers’ actions and promotes teacher development (Hatton & Smith, Citation1995; Mälkki & Lindblom-Ylänne, Citation2012). To turn reflection into action, it is necessary to understand the concept and practice of reflection (Pekkarinen & Hirsto, Citation2017). Furthermore, there is evidence of individual differences and preferences in using various reflective tools (Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020; Russell, Citation2005). Recent research has shown that the awareness of reflection on one’s actions as a teacher increases in accordance with the pedagogical studies completed during a long-term pedagogical development program (Nevgi & Löfström, Citation2015; Pekkarinen & Hirsto, Citation2017).

Reflection is not, however, only a cognitive activity, but it is more so an activity that is strongly related to social relationships. Mezirow (Citation2000) has argued that reflective discourse with others helps the individual to share experiences, evaluate and interpret these experiences, and use the experiences of others to evaluate their own. This sharing with others enhances reflection to become a powerful tool for teacher development (e.g., Brookfield, Citation1995; Mälkki, Citation2011; Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020; Pyörälä et al., Citation2015, Citation2021; Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2009; Uitto et al., Citation2015). Social relationships among university teachers, especially with peers and colleagues, are central to how teachers construe, experience, and develop their pedagogical competency (e.g., Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014). This is based on the interpretation of academic identity and experience as contextual and socially created (Boyd & Harris, Citation2010; Garavan & McGuire, Citation2001; Isopahkala-Bouret, Citation2008; Olsson & Roxå, Citation2013; Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020; Sandberg, Citation2000; Uitto et al., Citation2015; Weller, Citation2016). Informed pedagogical discussions support university teachers to acquire theoretical and personalized knowledge about teaching and learning, to share their knowledge and skills, and to learn from others (Boyd & Harris, Citation2010; Olsson and Roxå Citation2013). Social relations and peer support can emerge in significant networks of teachers that can be found, for example, within the teacher’s department and institution, or via participating in pedagogical training programs (Pyörälä et al., Citation2015, Citation2021; Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2009). In addition, peer support can be obtained within educational development projects, in which the teachers can also form multidisciplinary peer groups (Hirsto & Löytönen, Citation2011; Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020). In this study, we use the concept of social reflection to refer to teachers’ joint reflection with significant others. Social reflection can be, for example, a discussion of teaching experiences with colleagues or other meaningful discussion partners.

There is also an emotional aspect to reflection. According to Boud et al. (Citation1985), emotions can be considered as elements of the reflective process in which individuals reconsider, think about, and evaluate their experience. Tynjälä and colleagues (Tynjälä et al., Citation2016) also combine social and emotional aspects by suggesting that the ability to recognize and deal with emotions is an important aspect of social competence, i.e., the skills needed for social interaction with others, such as the ability to listen to others or to look at a situation from others’ perspectives.

3. Methods

3.1. The context of this study

The context of the study is a one-year-long, research-based educational development project on flipped learning in a multidisciplinary Finnish university. The aim of the project was to support university teachers to utilize the flipped classroom approach in their teaching and to develop the university’s teaching toward a student-centered approach. The flipped classroom approach reverses the traditional way of teaching as a teacher-led activity and encourages teachers to prepare digital and online learning materials for students to study before class, leaving more time for interacting with the students and for processing the knowledge with them (Bishop & Verleger, Citation2013; Critz & Knight, Citation2013; Goodwin & Miller, Citation2013; Lee et al., Citation2017; Milman, Citation2014). In previous research, the development of pedagogical skills and the competency of a university teacher has often been often studied in the context of university pedagogical training courses (e.g., Clavert & Nevgi, Citation2011; Ödalen et al., Citation2018; Pekkarinen & Hirsto, Citation2017; Postareff et al., Citation2007). However, it is also possible to develop pedagogical skills and competency via participating in different kinds of educational development projects (e.g., Hirsto & Löytönen, Citation2011; Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020).

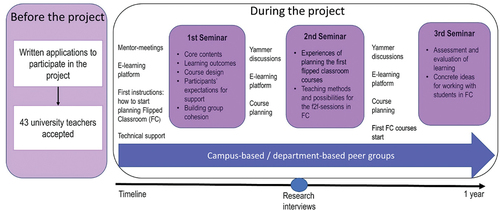

University teachers who were interested in developing their teaching through the flipped classroom approach were recruited, and a total of 43 university teachers were accepted to participate in the project. The educators and mentors of the project provided pedagogical support to the participants in designing and implementing the flipped classroom approach in their classes, technical support on utilizing e-learning tools, and peer support in the form of peer groups, mentor meetings, a shared e-learning platform, and the virtual discussion group in Yammer (see Figure ; cf., Hyypiä et al., Citation2019; Väisänen & Hirsto, Citation2020). The peer groups were either campus- or department-based, and most of the peer groups formed during the project were multidisciplinary, meaning that the participants of the groups came from different disciplinary backgrounds. The multidisciplinarity of the peer groups was encouraged, as it has been shown that multidisciplinarity can be of particular benefit from the perspective of more diverse debates, for example, (cf., Sandholtz, Citation2000). In addition, the teachers participated in three joint seminar meetings, and they studied the literature on the flipped classroom approach and teaching development during the project.

3.2. Participants in the study

The participants in the study were nine university teachers from the group of 43 teachers who participated in the educational development project and accepted the invitation to participate in the interviews. The interviewees represented different disciplinary backgrounds (e.g., health science and medicine, bio and environmental sciences, science, and other university units) and had teaching experience of 4–10 years (five out of nine) or 10–25 years (four out of nine) in teaching undergraduate students in a university context. Eight out of nine of the interviewed teachers had 25–60 ECTS, and one interviewed teacher had less than 25 ECTS credits of pedagogical studies completed. To protect the anonymity of the interviewed teachers, their gender and position in the university are not revealed, and in the interview quotes, they are referred to by codes (from T1 to T9).

3.3. Data collection and analysis

The data were collected through semi-structured interviews in the middle of the project (see, Figure ). Semi-structured interviews have been found to be well-suited to capture teachers’ reflections on their past emotional experiences (Chen, Citation2016). Two pilot interviews were conducted to test and finalize the question themes and guiding questions used in the research interviews (Galletta & Cross, Citation2013). The length of the interviews varied from 35 minutes to 95 minutes, and they were transcribed verbatim. The transcriptions consisted of a total of 58 pages (A4, Times New Roman 12 pt., 1.5 spacing). The teachers were asked open-ended guiding questions according to the themes chosen for the interview based on the research literature (Galletta & Cross, Citation2013). Guiding questions were related to the teacher’s experience as a university teacher, their reflection on teaching, the role of peers and colleagues in teaching, developing their teaching and as a teacher, the kinds of emotions the teacher has related to teaching and developing as a teacher, and how these emotions are dealt with in the teacher’s teaching community.

We analyzed the data by qualitative content analysis using Atlas.ti 8.0 software. The analysis was conducted by the first author, and the second author confirmed the analysis. The third author participated by commenting on the interpretations of the categories. We used open coding in the analysis, and the analysis unit was a conceptual theme that was identified in the data to vary from a few words to several sentences. The analysis began with several rounds of reading and coding of the data and continued by integrating a data-driven inductive approach with a concept-driven deductive approach, moving back and forth between both sources (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008; Gibbs, Citation2007). This approach closely relates to theory-guided qualitative content analysis that is based on both inductive and deductive procedures (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008; Creswell, Citation1994; Gibbs, Citation2007; Merriam, Citation2009; Miles et al., Citation2014). In practice, we compared, for example, the preliminarily identified categories of positive and negative emotions with those of the previous studies on emotions, e.g., those identified in the CVT by Pekrun (Citation2006; see also, Pekrun et al. Citation2007), but the analysis was not limited to them. After coding the data, we continued the analysis by grouping the data into different themes, categories, and sub-categories. We evaluated the reliability of separate individual categorizations of the first and second authors by conducting an intercoder reliability test, also referred to as the intercoder agreement (Cho, Citation2008; Gibbs, Citation2007; Miles et al., Citation2014; Neuendorf, Citation2002). The authors reached 91.5% intercoder agreement and continued discussing the coding and categories until a full shared understanding was reached.

4. Results

The results of this study are presented in the following sections and include quoted material depicting teachers’ emotions and their reflections on these emotions. The quotes have been translated from Finnish to English by the two first authors.

4.1. University teachers’ emotions experienced in teaching

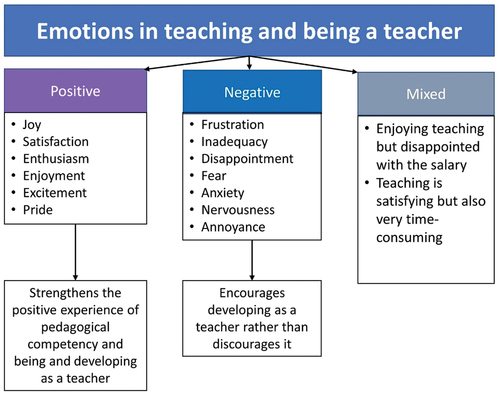

The first research question focused on what kinds of emotions university teachers experience in teaching. All nine university teachers participating in this study expressed that they had experienced various positive, negative, and mixed emotions in teaching (see, Table ). A total of 50 text segments expressing teaching-related emotions were identified, of which 28 expressed positive emotions; 20, negative emotions; and 2, mixed emotions.

Table 1. Positive, negative, and mixed emotions by the number of university teachers experiencing the emotion in teaching and the total number of mentions of the emotion

Positive emotions experienced in teaching described by the interviewees were joy, satisfaction, enthusiasm, enjoyment, excitement, and pride. All of the interviewed teachers reported experiencing one or more positive emotions. Of the positive emotions, joy, satisfaction, and enthusiasm were mentioned most often. In particular, these emotions as well as pride were experienced when teachers felt successful in their teaching and when they saw their students learning.

“Sometimes there is this great feeling of joy when I see that this works.” (T3)

“They are more like feelings of satisfaction, as I notice how students develop.” (T8)

“I always experience this kind of enthusiasm whenever I give a good lecture, facilitate a discussion, or pull through another [teaching] situation … ” (T2)

“I don’t know whether I can call it pride or what, but anyway it is feeling good about succeeding in this [teaching] … ” (T6)

Enjoyment was experienced when the teachers received positive feedback from their teaching.

“I have enjoyed reading [the reflective student essays at the end of the course, including feedback] very much and I felt successful in every respect. Yeah, flipping teaching works. I made it and it also brings added value to student learning.” (T3)

In addition, teachers described teaching as an enjoyable and positive part of their academic work, and that teaching provided them feelings of excitement and enthusiasm to carry on teaching activities.

“ … when I have the feeling that I like this and I really enjoy teaching, it helps me to carry on in my work.” (T1)

“[Teaching] causes me to feel excitement but also enthusiasm, and I really rarely feel that feeling of, oh no, I have to go and teach. I think that being able to teach is kind of the extra spice in my job.” (T5)

The negative emotions experienced in teaching described by the interviewees were frustration, inadequacy, disappointment, fear, anxiety, nervousness, and annoyance. All of the interviewed teachers reported experiencing one or more of the negative emotions. Of the negative emotions, inadequacy, anxiety, and frustration were mentioned most often.

Inadequacy, anxiety, and frustration were especially experienced by the teachers in situations where they felt they could not prepare to teach as well in advance as they would have liked—for example, when they did not have enough time or had to wait for someone else’s contribution first.

“I think that the most prevalent feeling is inadequacy. And I think that is caused by the fact that I know that I could do things better, but I don’t have the time … it sometimes also causes anxiety when things are left to be done in the last minute. I don’t like at all. I like to prepare all in advance … And, of course, sometimes there is frustration when I know that I need to do something, but someone else needs to do something before I can do my thing, and the whole thing waits.” (T6)

Frustration and disappointment were experienced as being triggered by student behavior—for example, when a teacher felt that students did not try their best in their studies. Students’ behavior could also trigger annoyance in teachers—for example, when the students complained or asked too many questions that the teachers considered irrelevant.

“ … I am frustrated [when students don’t do their best in their studies], but I have tried to coach myself that it is not my job to take care of the student’s life.” (T8)

“Sometimes I feel disappointed when everything does not go the way I wanted, especially when I feel that I have put a lot of effort in teaching and the student does not put in the same effort.” (T5)

“ … I am so annoyed by all the small things and questions the students ask from me, like ‘do I have to participate in teaching’ or ‘can I be absent from this class’, I think these are also kind of childish conversations in university teaching.” (T2)

Fear and nervousness were also experienced when teachers were unsure about their competency—for example, when starting to teach as a novice teacher, when trying something new for the first time, or when starting to teach a new group of students.

“ … I was afraid of trying out flipped learning … and that I can’t get the same contact to my students that I get when teaching in the classroom that they like so much.” (T4)

“I feel always so nervous when I go in front of a new student group; I feel that I have butterflies in my stomach.” (T3)

Two of the interviewed teachers expressed that they had experienced both positive and negative emotions—i.e., mixed emotions—in teaching. For example, they reflected on how they enjoyed teaching, but were disappointed with the monetary compensation they received; or, they found teaching to be satisfying, but, at the same time, time-consuming, which meant that they had to work overtime.

“I like being with students very much, and I really enjoy teaching. The only thing here is that the monetary compensation is really low … ” (T1)

“[I have] very mixed emotions [related to teaching]. On the other hand, teaching is very satisfying, especially when I notice that the students have learned. But then again, teaching is very time-consuming, and I work overtime a lot.” (T8)

4.2. The influence of teaching-related emotions on university teachers’ experienced pedagogical competency and being and developing as a teacher

The second research question focused on how the teaching-related emotions influence the way the teachers experience their pedagogical competency and their being and developing as a teacher. Analyses of teachers’ teaching-related emotions revealed that both positive and negative emotions influence how they experience themselves as teachers and their pedagogical competency, and how they develop as teachers (see, Figure ). Reflecting on teaching made the teachers more aware of their teaching-related emotions and how these emotions changed when they gained more teaching experience and developed as teachers and in their pedagogical competency.

Figure 2. University teachers’ teaching-related emotions and how these emotions influence the way the teachers experience their pedagogical competency and their being and developing as a teacher.

“All emotions are … like self-knowledge, the way you experience yourself and the kinds of emotions you have influence how you teach.” (T1)

“ … this has been a kind of development process, that is, recognizing my own emotions, and being able to express them. … I wish that I would remember to look back and realize how long a journey I have had as a teacher, how I have developed and that the emotions are totally different now, e.g., experiencing joy when succeeding in teaching versus what they were at the beginning, e.g., inadequacy. This has developed my professional identity significantly.” (T3)

Positive teaching-related emotions were found to strengthen the positive experience of one’s pedagogical competency and of being and developing as a teacher.

“Succeeding in teaching, of course, strengthens myself as being a teacher. I feel that things went really well, and it feels good.” (T6)

“Of course, the positive experiences and emotions strengthen it [pedagogical competency] and creates a good feeling.” (T7)

Negative emotions, on the other hand, were not experienced as discouraging. Teachers reflected that the negative emotions they experienced while teaching reminded them of how they could improve themselves as teachers as well as their teaching. Thus, the negative emotions were experienced as encouraging the teachers to develop further as teachers and to improve their teaching.

“When I feel inadequate or something falls through, I realize that I need more information, and I need to develop my teaching.” (T5)

“Well, failing in teaching kind of reminds me of the humanity in also being a teacher, I do not lose my professional self-confidence because of it. Maybe it just points out certain development points that I need to consider more in the future. And of course, in my other teaching as well. I see it as an opportunity to pay more attention to those things in the future and as an opportunity to also learn as a teacher.” (T6)

4.3. Social reflection of teaching and teaching-related emotions

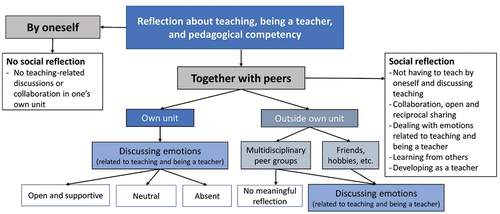

The third research question focused on how and with whom the university teachers reflect on their teaching and teaching-related emotions. All of the interviewed teachers reported that they reflected on their teaching and being a teacher by themselves. Most teachers also reflected with their peers and colleagues of their own unit or with peers and friends outside their own unit (see, Figure ).

The teachers mentioned many reasons for wanting to socially reflect, such as learning from others and developing as a teacher, not having to teach and plan teaching alone, sharing teaching experiences and materials openly and reciprocally, and dealing with emotions related to teaching and being a teacher.

“[I reflect on my teaching] both by myself and with my colleagues. Quite often, when I have an idea on how to develop my teaching, even if it would be a bad one, I go to a colleague and reflect on how it would work, how it could be tested in teaching … It is so fruitful to be able to ponder and take on new ideas to be tried out in teaching … In addition, there are flops every now and then. It is very important to have peer support to reflect on and understand that it was not such a big failure.” (T4)

“Peers have quite a significant role, especially among [my teaching community] teachers, we have had a really good collaboration going on for several years, exchanging ideas and materials. If someone has a good idea, they will send it to the others, and the others can try out the idea.” (T7)

There were also opposite experiences about social reflection and collegial collaboration in teaching. The reason why social reflection with peers and colleagues in teaching was not pursued was that there was no habitual practice of discussing or collaborating with peers regarding teaching, as teaching was considered to be a private and independent activity.

“[I reflect on my teaching] quite a lot by myself. In my department, research and being a researcher is a fundamental thing for everyone. We have courses that we teach together, and we discuss how everybody is doing. But the courses that I am responsible for, they really are my responsibility, and my colleagues do not take part in those courses that much.” (T9)

The interviewed teachers reported that they found social reflection partners and peer support, for example, within their own unit or department. Analysis of teachers’ social reflection habits revealed, however, that the atmosphere for socially reflecting on teaching-related experiences and emotions in the teachers’ teaching communities varied. Three different organizational atmospheres toward social reflection on teaching-related emotions could be identified: (1) open and supportive, (2) neutral, and (3) absent. The open and supportive atmosphere was experienced as enabling a teacher to discuss their emotions related to teaching. Most of the university teachers reported that they could freely discuss their experiences and emotions related to teaching with their peers in their teaching community.

“We can very well air our feelings and emotions, and I have not experienced that no one would feel upset or bad afterwards. We have a very open culture.” (T2)

“Our coffee room is a place where we share both the experiences of succeeding in teaching and the not-so-successful experiences. It is quite a permissive environment to share these experiences as we celebrate the success, laugh about the failures, and wonder what went wrong together. I see our working community as very supportive, including on those occasions when you start to think that there are more failures than successes in teaching.” (T6)

The neutral atmosphere was not experienced as particularly encouraging for a teacher to discuss their emotions related to teaching, but not particularly discouraging either. In this realm, the teachers felt that they were able to have discussions with their colleagues and to express their emotions when so desired.

“ … I have not received negative feedback about showing emotions in teaching” (T4)

“ … everyone knows that they can talk to anyone and have a discussion without preplanning it.” (T8)

The third category, the absent atmosphere, was experienced as not discouraging discussion on emotions as such, but there was a lack of practice or tradition in discussing or sharing teaching-related emotions.

“ … these emotions related to teaching are not the main point … we don’t have an established practice concerning expressing emotions.” (T9)

In addition to discussing and reflecting teaching and teaching-related emotions within their own unit, the teachers mentioned that they have also found peer support outside their own unit—for example, from the multidisciplinary peer groups formed during the educational development project. The experienced meaning of the multidisciplinarity of peer group for the teachers in this study, however, varied, as multidisciplinarity could be identified either as a promoting or inhibiting factor regarding social reflection, peer support, collaboration, and learning from others. When considered as a promoting factor, the teachers experienced it as being meaningful to engage in social reflection with peers as well as to share and discuss their teaching-related emotions. When considered as an inhibiting factor, social reflection with peer group members with different disciplinary backgrounds was not experienced as meaningful, because the teachers experienced that they were unable to make full use of what they learned from other teachers in their teaching.

“In the flipped learning peer group, we had the possibility to go through our courses with people from different disciplinary fields and got good tips. … It has been fun, in our peer group, to try to explain one’s course to someone who knows less about the course theme than the students in the course, and that is why one has to make a good effort in spelling out what is important in the course and why … and then we started to notice that we could perhaps use the same methods in our own course … regardless of the subject, sometimes the methods can be the same.” (T4)

“With the [flipped learning] peer group, we had the challenge that we were from different disciplinary fields, and that’s why it was not always possible to apply and utilize the methods used in some other course in my own course. We did not meet with the peer group that often.” (T6)

Furthermore, the social relations, peer support, and meaningful social reflection partners could also be found in other significant social relationships—for example, via friends or hobbies.

“Since graduation, I have pondered and reflected on this with the same friend [about teaching] during our free time.” (T1)

5. Discussion

This study aimed at understanding what kinds of emotions university teachers experience in teaching, and how these emotions influence the way the teachers experience their pedagogical competency and their being and developing as a teacher. We found that university teachers experience both positive and negative emotions related to teaching. All of the interviewed university teachers reported having experienced both positive (joy, enthusiasm, enjoyment, excitement, satisfaction, and pride) and negative (frustration, anxiety, disappointment, fear, inadequacy, annoyance, and nervousness) emotions. Some of the positive and negative emotions were the same as identified in Pekrun’s CVT (Pekrun, Citation2006; Pekrun et al., Citation2007) as well as by several other researchers, namely joy and pride (e.g., Kordts-Freudinger, Citation2017; Myyry et al., Citation2019), enjoyment and anxiety (e.g., Kordts-Freudinger, Citation2017; Löfström & Nevgi, Citation2014; Peterson et al., Citation2015; Stupnisky et al., Citation2016; Thies & Kordts-Freudinger, Citation2019b), and frustration (e.g., Kordts-Freudinger, Citation2017; Peterson et al., Citation2015; Stupnisky et al., Citation2016). In addition to the emotions included in the CVT, there were emotions that have been identified also in other studies, namely enthusiasm (e.g., Postareff & Lindblom-Ylänne, Citation2011), annoyance (e.g., Peterson et al., Citation2015; Trigwell, Citation2012), and excitement and disappointment (e.g., Stupnisky et al., Citation2016).

The interviewed teachers reported that they also experience mixed emotions, which include both positive and negative emotions. In previous studies, mixed emotions have been reported less frequently than positive and negative emotions. In their study regarding emotions in university teaching, Löfström and Nevgi (Citation2014) analyzed academics’ drawings of themselves as university teachers and identified positive, negative, neutral, and mixed emotions related to teaching. They interpreted the drawings that included no visible emotions as illustrating neutral emotions in teaching. Mixed emotions were described to include both positive and negative emotions, similar to this study.

Our research revealed that the teaching-related emotions influence the way the teachers experience their pedagogical competency, themselves as a teacher, and their developing as a university teacher. This is in line with previous research findings suggesting that there is an emotional dimension to the experience of expertise as an academic and a teacher, meaning that the way in which teachers experience themselves as teachers also influences how they are as teachers (Day & Leitch, Citation2001; Isopahkala-Bouret, Citation2008; Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020; Postareff & Lindblom-Ylänne, Citation2011; Weller, Citation2016). Our results show that the teachers experienced positive emotions to strengthen the positive experience about their pedagogical competency and professional identity and encourage them to develop their teaching and as a teacher. On the other hand, in this study, negative emotions were not experienced as discouraging, but instead, they also were reported to encourage a teacher to develop themselves and their teaching further. This is in accordance with the CVT (Pekrun et al., Citation2007), which argues that, when one experiences being capable of dealing with some issue and the control is high, positive emotions such as enjoyment may emerge. These positive activating emotions are assumed to increase and strengthen motivation. When there is controllability, but the activity is negatively valued, negative emotions such as anger can be experienced. Furthermore, if the activity is highly valued but not controllable, emotions such as frustration can be experienced. Negative activating emotions are assumed to be more ambivalent in their effects on motivation and cognitive processing. A teacher may be able to use the motivational energy implied by teaching-related anxiety to increase their efforts towards it, and their performance can be enhanced instead of being impaired. (Pekrun et al., Citation2007.) Thus, negative emotions do not always lead to low motivation and discouragement, but rather the motivation caused by the negative emotion can be harnessed for actions in developing as a teacher, as the findings of our study reveal. The participants of this study were also participating in an ongoing educational development project, which provided continuous support and also concrete tools for teachers to develop their teaching and courses, and this may have affected the clear result that the negative emotions were experienced as activating. Examining such a perspective would require a more-detailed investigation, with possible quasi-experimental research design, in the future.

In addition to emotions, we found that peers and social networks appear to play an important role in how the university teachers experience themselves as teachers and how they deal with teaching-related emotions (see, also Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014). All of the interviewed university teachers reflected on their teaching by themselves, and most of them also reflected with their colleagues and peers. Discussions and reflections with peers and colleagues aimed at sharing ideas openly and reciprocally, learning from each other and sharing teaching-related emotions. Social reflection with others seemed to help teachers to assess and interpret these emotions and experiences, and to draw on others’ emotions and experiences in their developing as a teacher (see also, Mezirow, Citation2000). With regard to socially sharing experiences and emotions in this study, we do not mean collective or group-based emotions (Kessler & Hollbach, Citation2005; Salmela, Citation2012; Smith & Mackie, Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2007), but rather sharing individually experienced emotions in social reflection with significant others as to how to be and develop as a teacher. Previous studies have also found social reflection and peer support to be powerful tools in developing as a teacher (e.g., Boyd & Harris, Citation2010; Mezirow, Citation2000; Olsson and Roxå Citation2013; Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020; Pyörälä et al., Citation2015, Citation2021; Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2009; Uitto et al., Citation2015).

Many of the interviewed teachers experienced that they were able to socially reflect and discuss their teaching-related emotions in their teaching communities, and that in general, their teaching communities were positive and open about sharing teaching-related experiences and emotions. Some of the teachers experienced their teaching communities to be quite neutral in discussing and sharing one’s teaching-related experiences and emotions, as it was neither forbidden nor encouraged. There were also contrasting views on social reflection and social sharing of emotions, as some teachers experienced that discussions or social reflection on emotions with their peers or colleagues were absent in their teaching communities. We found that, in addition to the teacher’s immediate teaching community, meaningful social networks and reflection partners could also be found outside such communities—for example, via participation in an educational development project as well as among friends and in hobby-related activities. Similar results have been reported by Pyörälä and colleagues (Pyörälä et al., Citation2015). In their study, significant networks were found among (1) colleagues and other teachers, (2) peers in pedagogical courses and pedagogical experts, (3) students, and (4) family members and friends. Furthermore, Roxå and Mårtensson (Citation2009) reported in their study that conversational partners were found (1) within the teacher’s own discipline, (2) within their department, (3) within their institution, or (4) elsewhere.

Most of the peer groups in our study were multidisciplinary, as the participants in the groups came from different disciplinary backgrounds. In our earlier study (Pekkarinen & Hirsto, Citation2017) that was carried out in the university pedagogical training context, there also were multidisciplinary peer groups of teachers. The participants in that study were able to share their experiences and emotions with each other, learn from each other, formulate new ideas for their teaching by learning from others’ experiences, and receive support in constructing their teacher identity and teachership from peers and colleagues in the same situation, regardless of their different disciplinary backgrounds. What is different in our study, however, is that the experienced meaning of the multidisciplinary peer group for the teachers varied, as multidisciplinarity could be identified either as a promoting or inhibiting factor regarding peer support, social reflection, collaboration, and learning from others.

Limitations of this study. First, we acknowledge that the number of interviewed teachers was only nine. However, for qualitative research, there is no common rule concerning how many people should be interviewed, as the proper number of interviewees always depends on the research design and the purpose of research (Baker et al., Citation2012). In addition, the quantity of the results is not decisive, as even a single experience can be relevant, not only the ones that are experienced by many (Hänninen, Citation2016). Second, the participants of the study represent pedagogically aware university teachers, as they have completed varying amounts of pedagogical studies. Thus, the results of our study may not be generalizable to all university teachers. However, this study can offer valuable insights for higher education institutions in building their teaching development actions.

Conclusions and practical implications. Our results show that university teachers experience positive, negative, and mixed emotions related to teaching, and that these emotions influence the way they experience both themselves as teachers as well as their pedagogical competency. In addition, social reflection, along with the sharing of teaching-related experiences and emotions, can be a powerful tool in developing as a university teacher. It is important to recognize this when planning development activities for university teachers. Higher education institutions should create such environments, where social reflection and discussion are encouraged, and where opportunities to share emotions related to teaching and being a teacher are offered. Being able to reflect on emotions, whether positive or negative, can lead to development as a teacher. Previous studies (e.g., Clavert & Nevgi, Citation2011; Nevgi & Löfström, Citation2015; Ödalen et al., Citation2018; Pekkarinen & Hirsto, Citation2017; Postareff et al., Citation2007) have shown that pedagogical courses and training programs can, in fact, be these environments. However, not all university teachers want to participate in pedagogical courses and are able to benefit from them (Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020). Our study shows that an educational development project, which considers the formation and support of peer groups of teachers offering possibilities for multidisciplinary collaboration, can also form a fertile context for developing as a university teacher, as it enables collaborative discussions in applying and developing pedagogical perspectives into the varying practices of different faculties (see also, Hirsto & Löytönen, Citation2011; Pekkarinen et al., Citation2020; Sandholtz, Citation2000). Pedagogical courses and educational development projects may appeal to different types of teachers, and, therefore, versatile contexts and methods should be used in facilitating the development of university teachers. In future research, it would be interesting to examine more closely the key factors in multidisciplinary peer groups regarding the support offered and received for teacher learning and professional development, as well as how these peer groups function in the long run after the development project is over.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the personnel and participants in the Flipped Learning Educational Development Project at The University of Eastern Finland, especially Erkko Sointu and Markku Saarelainen for their valuable support for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Virve Pekkarinen

Pekkarinen Virve (M.A. in adult education, MBA in leadership and human resources management, B.Sc. in social sciences) is a PhD student at the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Eastern Finland. Currently, she works at Laurea University of Applied Sciences as a Development manager of adaptive digital learning solutions. In addition, she has worked for over ten years as a University Pedagogical Expert and Teacher Trainer in HE context. She has published articles on university teachers’ pedagogical competency, social reflection, and emotions, as well as innovative and adaptive digital teaching and learning solutions.

Laura Hirsto

Professor, Laura Hirsto (PhD) works at the School of Applied Educational Science and Teacher Education at the Philosophical Faculty of University of Eastern Finland. Hirsto is leading various research and development projects related to academic and educational development, student learning and teacher learning in various contexts. Her interests are in students’ and teacher students’ learning and motivational processes, pedagogical learning analytics and in variations of effective teaching and learning environments.

Anne Nevgi

Dr. Anne Nevgi, Associate Professor (retired), is an active senior researcher in the Faculty of Education at the University of Helsinki. She leads a research project on emotions in assessment practices and is involved in a research project on campus learning environments. She has published several articles and books on teaching and learning in higher education, teacher identity development in higher education, emotions in assessment practices and on self-regulation in learning.

References

- Baker, S. E., Edwards, R., & Doidge, M. 2012. “How many qualitative interviews is enough? Expert voices and early career reflections on sampling and cases in qualitative research.” Review paper. National Centre for Research Methods, Southampton, UK. Accessed October 2, 2021. https://research.brighton.ac.uk/en/publications/how-many-qualitative-interviews-is-enough-expert-voices-and-early

- Bishop, J. L., & Verleger, M. A. 2013. “The flipped classroom: A survey of the research.” Paper presented at 2013 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Atlanta, Georgia. Accessed October 2, 2021. https://peer.asee.org/22585

- Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Promoting reflection in learning: A model. In D. Boud, R. Keogh, & D. Walker (Eds.), Reflection: Turning experience into learning (pp. 18–18). Kogan Page.

- Boyd, P., & Harris, K. (2010). Becoming a university lecturer in teacher education: Expert school teachers reconstructing their pedagogy and identity. Professional Development in Education, 36(1–2), 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415250903454767

- Brookfield, S. (1995). Becoming A critically reflective teacher. Jossey-Bass.

- Chen, J. (2016). Understanding teacher emotions: The development of a teacher emotion inventory. Teaching and Teacher Education, 55, 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.001

- Cho, Y. (2008). Intercoder Reliability. In P. J. Lavrakas (Ed.), Encyclopedia of survey research methods (pp. 345–346). Sage.

- Clavert, M., & Nevgi, A. (2011). Yliopistopedagogisen koulutuksen merkitys yliopisto-opettajana kehittymisen kokemuksessa [The meaning of the university pedagogical training in experiencing the development as a teacher]. Yliopistopedagogiikka, 18(2), 6–16. Accessed October 2, 2021 https://lehti.yliopistopedagogiikka.fi/2012/11/13/yliopistopedagogisen-koulutuksen-merkitys-yliopisto-opettajana-kehittymisen-kokemuksessa/

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. L. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed) ed.). Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. (1994). Research design: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Sage.

- Critz, C., & Knight, D. (2013). Using the flipped classroom in graduate nursing education. Nurse Educator, 38(5), 210–213. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0b013e3182a0e56a

- Day, C., & Leitch, R. (2001). Teachers’ and teacher educations’ lives: The Role of emotion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(4), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01

- Duţă, N., Pânişoară, G., & Pânişoară, I. O. (2014). The profile of the teaching profession – Empirical reflections on the development of the competences of university teachers. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 140, 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.440

- Frenzel, A. C. (2014). Teacher Emotions. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 494–519). Routledge.

- Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Daniels, L. M., Durksen, T. L., Becker-Kurz, B., & Klassen, R. M. (2016). Measuring teachers’ enjoyment, anger, and anxiety: The Teacher Emotions Scales (TES). Contemporary Educational Psychology, 46, 148–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.05.003

- Galletta, A., & Cross, W. E. (2013). Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: From research design to analysis and publication. New York University Press.

- Garavan, T. N., & McGuire, D. (2001). Competencies and workplace learning: Some reflections on the rhetoric and the reality. Journal of Workplace Learning, 13(4), 144–164. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620110391097

- Gibbs, G. R. (2007). Analyzing qualitative data. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208574

- Goodwin, B., & Miller, K. (2013). Evidence on flipped classrooms is still coming in. Educational Leadership, 70(6), 78–80. Accessed October 2, 2021 https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/evidence-on-flipped-classrooms-is-still-coming-in

- Hagenauer, G., & Volet, S. (2014). ‘I Don’t Think I Could, You Know, Just Teach without any emotion’: Exploring the nature and origin of university teachers’ emotions. Research Papers in Education, 29(2), 240–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2012.754929

- Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(94

- Hirsto, L., & Löytönen, T. (2011). Kehittämisen kolmas tila? Yliopisto-opetus kehittämisen kohteena [The third mode of development? University education as a subject of development]. Aikuiskasvatus, 31(4), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.33336/aik.93953

- Hyypiä, M., Sointu, E., Hirsto, L., & Valtonen, T. (2019). “Key components of learning environments in creating a positive flipped classroom course experience.”. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 18(13), 61–86. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.18.13.4

- Hänninen, V. (2016). Kuinka paljon on tarpeeksi? Aineiston määrä laadullisessa tutkimuksessa [How Much is Enough? The Amount of Data in Qualitative Research]. Aikuiskasvatus, 36(2), 109–113. https://doi.org/10.33336/aik.88484

- Isopahkala-Bouret, U. (2008). Asiantuntijuus kokemuksena [Expertise as an Experience]. Aikuiskasvatus, 28(2), 84–93. Accessed September 9, 2021 http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:ELE-1432128

- Jakhelln, R. (2011). Early career teachers’ emotional experiences and development – A Norwegian case study. Professional Development in Education, 37(2), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2010.517399

- Kessler, T., & Hollbach, S. (2005). Group-based emotions as determinants of ingroup identification. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(6), 677–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.01.001

- Kordts-Freudinger, R. (2017). Feel, think, teach – Emotional underpinnings of approaches to teaching in higher education. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(1), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n1p217

- Lee, J., Lim, C., & Kim, H. (2017). Development of an instructional design model for flipped learning in higher education. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65(2), 427–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9502-1

- Löfström, E., & Nevgi, A. (2014). Giving shape and form to emotion: Using drawings to identify emotions in university teaching. International Journal for Academic Development, 19(2), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.819553

- McAlpine, L., Weston, C., Beauchamp, C., Wiseman, C., & Beauchamp, J. (1999). Building a metacognitive model of reflection. Higher Education, 37(2), 105–131. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:

- Merriam, B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (2nd ed) ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning to think like an adult. Core concepts of transformation theory. In J. Mezirow (Ed.), Learning as transformation. Critical perspectives on a theory in progress (edited by) ed., pp. 3–33). Jossey-Bass.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed) ed.). Sage.

- Milman, N. B. (2014). The flipped classroom strategy: What Is It and How Can It Best Be Used? Distance Learning, 11(4), 9–11. Accessed October 2, 2021 https://www.proquest.com/openview/ce8a9fa41e4c2f901d58310b4c63eb57/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=29704

- Moors, A., Ellsworth, P. C., Scherer, K. R., & Frijda, N. (2013). Appraisal theories of emotion: State of the art and future development. Emotion Review, 5(2), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073912468165

- Myyry, L., Karaharju-Suvanto, T., Vesalainen, M., Virtala, A.-M., Raekallio, M., Salminen, O., Vuorensola, K., & Nevgi, A. (2019). Experienced academics’ emotions related to assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1601158

- Mälkki, K. 2011. “Theorizing the nature of reflection. Doctoral dissertation.” University of Helsinki, Institute of Behavioural Sciences, Helsinki. Accessed September 9, 2021. http://urn.fi/URN

- Mälkki, K., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2012). From reflection to action? Barriers and bridges between higher education teachers’ thoughts and actions. Studies in Higher Education, 37(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.492500

- Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. SAGE.

- Nevgi, A., & Löfström, E. (2015). The development of academics’ teacher identity: Enhancing reflection and task perception through a university teacher development programme. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 46, 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.01.003

- Olsson, T., & Roxå, T. (2013). Assessing and rewarding excellent academic teachers for the benefit of an organization. European Journal of Higher Education, 3(1), 40–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2013.778041

- Pekkarinen, V., & Hirsto, L. (2017). University lecturers’ experiences of and reflections on the development of their pedagogical competency. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(6), 735–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1188148

- Pekkarinen, V., Hirsto, L., & Nevgi, A. (2020). The ideal and the experienced: University teachers’ perceptions of a good university teacher and their experienced pedagogical competency. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 32(1), 13–30. Accessed September 30, 2021 http://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/pdf/IJTLHE3634.pdf

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

- Pekrun, R. (2019). Inquiry on emotions in higher education: Progress and open problems. Studies in Higher Education, 44(10), 1806–1811. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1665335

- Pekrun, R., Frenzel, A. C., Götz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2007). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: An integrative approach to emotions in education. In P. Schutz & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion in Education (pp. 13–36). Academic Press.

- Pekrun, R., Lichtenfeld, S., March, R., Murayama, K., & Goetz, T. (2017). Achievement emotions and academic performance: Longitudinal models of reciprocal effects. Child Development, 88(5), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12704

- Peterson, E. R., Brown, G. T., & Jun, M. C. (2015). Achievement emotions in higher education: A diary study exploring emotions across an assessment event. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 42, 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.05.002

- Postareff, L., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2011). Emotions and confidence within teaching in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 36(7), 799–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.483279

- Postareff, L., Lindblom-Ylänne, S., & Nevgi, A. (2007). The effect of pedagogical training on teaching in higher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(5), 557–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.013

- Pyörälä, E., Hirsto, L., Toom, A., Myyry, L., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2015). Significant networks and meaningful conversations observed in the first-round applicants for the teachers’ academy at a research-intensive university. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(2), 150–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1029484

- Pyörälä, E., Korsberg, H., Peltonen, L. M., & Pang, N. S. K. (2021). How teaching academies promote interdisciplinary communities of practice: The Helsinki case. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1978624

- Quinlan, K. M. (2016). How emotion matters in four key relationships in teaching and learning in higher education. College Teaching, 6(3), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2015.1088818

- Roxå, T., & Mårtensson, K. (2009). Significant conversations and significant networks – Exploring the backstage of the teaching Arena. Studies in Higher Education, 34(5), 547–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802597200

- Russell, T. (2005). Can reflective practice be taught? Reflective Practice, 6(2), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690903424790

- Salmela, M. (2012). Shared Emotions. Philosophical Explorations, 15(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13869795.2012.647355

- Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. The Academy of Management Journal, 43(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556383

- Sandholtz, J. H. (2000). Interdisciplinary team teaching as a form of professional development. Teacher Education Quarterly, 27(3), 39–54. Accessed October 2, 2021 https://www.teqjournal.org/backvols/2000/27_3/2000v27n304.PDF

- Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Smith, E. R., & Mackie, D. M. (2016). Group-level Emotions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11, 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.005

- Smith, E. R., Seger, C. R., & Mackie, D. M. (2007). Can emotions be truly group level? Evidence regarding four conceptual Criteria. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(3), 431–446. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.3.431

- Stupnisky, R. H., Pekrun, R., & Lichtenfeld, S. (2016). New faculty members’ emotions: A mixed-method study. Studies in Higher Education, 41(7), 1167–1188. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.968546

- Su, F., Wood, M., & Taylor, C. (2012). What makes a good university lecturer? Students’ perceptions of teaching excellence. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 4(2), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/17581181211273110

- Thies, K., & Kordts-Freudinger, R. (2019a). German higher education academic staff’s positive emotions through work domains. International Journal of Educational Research, 98, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.08.004

- Thies, K., & Kordts-Freudinger, R. (2019b). University academics’ state emotions and appraisal antecedents: An intraindividual analysis. Studies in Higher Education, 44(10), 1723–1733. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1665311

- Trigwell, K. (2012). Relations between teachers’ emotions in teaching and their approaches to teaching in higher education. Instructional Science, 40(3), 607–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-011-9192-3

- Tynjälä, P., Virtanen, A., Klemola, U., Kostiainen, E., & Rausku-Puttonen, H. (2016). Developing social competence and other generic skills in teacher education: Applying the model of integrative pedagogy. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(3), 368–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2016.1171314

- Uitto, M., Kaunisto, S., Syrjälä, L., & Estola, E. (2015). Silenced truths: Relational and emotional dimensions of a beginning teacher’s identity as part of the micropolitical context of school. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(2), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2014.904414

- Väisänen, S., & Hirsto, L. L. (2020). How can flipped classroom approach support the development of university students’ working life skills? – University teachers’ viewpoint. Education Sciences, 10(12), 366–380. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120366

- Weller, S. (2016). Academic practice: Developing as a professional in higher education. Sage.

- Ödalen, J., Brommesson, D., Erlingsson, G. Ó., Schaffer, J. K., & Fogelgren, M. (2018). Teaching university teachers to become better teachers: The effects of pedagogical training courses at six Swedish universities. Higher Education Research and Development, 38(2), 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1512955