?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Revising teacher education frameworks and incorporating contemporary identified teacher attributes into the frameworks helps to ensure formidable initial teacher training. This paper validated teacher engagement efficacy for further consideration. Research findings that link preservice teachers’ teaching self-efficacy to their instructional effectiveness were found to be contradictory, whilst others had validity issues with the measurement of instructional effectiveness variable. Thus, there is inadequate support for the inclusion of teaching self-efficacy in teacher education frameworks. Therefore, using objective measurement of instructional effectiveness, the current study utilised ex-post facto research design to predict preservice management teachers’ instructional effectiveness based on their teaching self-efficacy. Secondary data were gathered on preservice teachers’ teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness; the dataset covered 119 cases. Empirical models were formulated to determine the nexus between preservice teachers’ teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness. Both descriptive (frequency and percentage) and inferential statistics (independent samples t-test, simple and multiple linear regressions) were used to analyse the data. Preservice management teachers’ level of instructional effectiveness was very good, which was not influenced by their gender and their age. Significantly, their student engagement efficacy positively influenced their instructional effectiveness. Therefore, teacher educators might risk preservice teachers’ instructional effectiveness should they (teacher educators) fail to develop their (preservice teachers) teaching engagement efficacy, with focus on behavioural, emotional and cognitive engagement.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The qualities or attributes that a teacher needs to execute an effective instructional session transcend pedagogical content knowledge, which is the knowledge to use specific teaching pedagogies to capture subject content and present it to learners’ understanding. Other supporting teacher attributes are needed to firmly drive pedagogical content knowledge. One of these teacher attributes as indicated in this paper is engagement self-efficacy (a belief that one can engage his or her learners to attain their learning and target needs). This paper suggests that a teacher’s belief to engage learners is an important teacher attribute for effective instruction. This line of thinking is due to the finding that preservice teachers’ engagement efficacy is directly related to their instructional effectiveness. Therefore, one’s desire to be an effective teacher must be consolidated with the belief that one can engage learners to learn.

1. Introduction

Teacher training institutions have adopted various strategies in enhancing the teaching capacity of preservice teachers (PTs) for Senior High Schools (SHSs). One of the strategies is microteaching, which falls under the teaching practicum component of the teacher education programme. Other components are subject content, pedagogy, education and professional studies (Lewin & Stuart, Citation2003). Apart from the teaching practicum, the other components present the complex theoretical knowledge PTs need about teaching in order to teach. This makes the microteaching strategy a critical aspect of the teacher education programme. Microteaching reduces the complexity of the tasks involved in teaching for student-teachers to understand and learn the “how” of teaching (Reddy, Citation2019). Through microteaching, student-teachers are made to teach lessons developed for short periods, usually for 5 to 20 minutes. Microteaching focuses on core skills such as lesson planning, introduction, presentation and explanation, stimulus variation, use of teaching aids, board writing, reinforcement, probing, classroom management, and closure skills (Reddy, Citation2019). These skills are catalogued as the most important skills student-teachers must develop to enter the teaching profession.

The microteaching strategy is structured into three phases—knowledge acquisition, skill acquisition and skills transfer (Koross, Citation2016). The skill acquisition phase allows PTs to plan micro-lessons to practice the skills in a small group setting. At the University of Cape Coast, student-teachers are placed in small groups to practice on the university campus (known as on-campus teaching practice [OCTP]). During the OCTP, student-teachers teach and reteach for their supervisors to shape their teaching skills. By the time the OCTP is over, the student-teachers are ready to teach in various SHS in the country, as they have acquired both the knowledge and the skills necessary to make them confident in teaching. Wongwiwatthananukit et al. (Citation2002) and DeCleene Huber et al. (Citation2015) noted that knowledge enforces self-confidence, and Asare (Citation2020) argued that self-confidence ensures success. This confidence is referred to as self-efficacy in the self-efficacy theory, and it is defined as “beliefs in one’s capabilities to organise and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (Bandura, Citation1997, p. 3). The self-efficacy theory models an input (beliefs in one’s capabilities), process (to organise and execute) and output (to produce a given attainment) relationship, and therefore supports effect analyses (Hair et al., Citation2019).

Self-efficacy is applied as a predictive power in determining human behaviour. For example, a teacher can ensure successful lessons (effective teaching), even amid classroom challenges (Graham et al., Citation2001). It has been noted that self-efficacy is a resilient predictor of both present behaviour and the effect of treatments on behaviour change (Henson. K, Citation2001). Extant studies (e.g., Knoblauch & Hoy, Citation2008; Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, Citation2001) found that individuals with a high sense of self-efficacy set high goals and exhibit a high commitment towards the achievement of such goals. When self-efficacy is applied to teaching, it is referred to as teaching self-efficacy and defined as “the belief a teacher has in his/her ability to organise and execute the courses of action required to accomplish a specific teaching task in a particular context” (Tschannen-Moran et al., Citation1998, p. 233). Teachers demonstrate teaching self-efficacy in three main dimensions: instructional strategies, classroom management and students’ engagement (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, Citation2001). These are classroom factors that influence students’ learning (Campbell et al., Citation2005).

During the skills transfer phase, it is expected that the training offered to PTs is appropriately utilised in their classrooms since they are prepared to confidently teach (Cahill, Citation2016; Senler & Sungur, Citation2010; Zuya et al., Citation2016). Evidence from educational literature (e.g., Bandura, Citation1986, Citation1997; Klassen & Tze, Citation2014) shows that teaching practice builds the teaching self-efficacy of PTs. Two decades ago, Albion (Citation1999) indicated that the strong influence of a person’s confidence to execute a task or behaviour had made teaching self-efficacy a subject of research for educational researchers. This is why researchers are interested in determining if PTs’ self-efficacy developed during the OCTP for the off-campus teaching practice (school experience) can predict their instructional effectiveness.

However, established relationships between preservice teachers’ teaching self-efficacy (PTTS) and instructional effectiveness are contradictory and seem to invalidate the self-efficacy theory (e.g., Bray-Clark & Bates, Citation2003; Gibbs, Citation2003; Klassen & Tze, Citation2014; Sehgal et al., Citation2017). This is because evidence from some of these studies either did not focus on the statistical relationship between teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness or measured instructional effectiveness from an objective point. Since some previous studies assessed PTs from their point of view, the PTs might have overestimated their instructional effectiveness through their subjective reportage to create an impression that they were effective.

According to Bandura (Citation1977), an individual judgment of their capability to perform a task predicts their capability to execute such a task. This implies that if PTs believe in their capability to teach, then they will be able to execute the teaching tasks and achieve instructional effectiveness. This theoretical claim motivated Asare (Citation2020) to assess preservice management teachers’ (PMTs’) teaching self-efficacy about the off-campus teaching practice. The author indicated that PMTs were highly efficacious to teach, hence, he concluded that they would be effective during the school experience. Similar to other studies, the reported teaching self-efficacy of PMTs was not used to predict their instructional effectiveness. Consequently, no valid claim could be made that their teaching self-efficacy influenced their instructional effectiveness. It was, therefore, not unusual when the author recommended that further investigations should establish the nexus between PTTS and their instructional effectiveness. This PTTS factor is already regarded as one of the powerful constructs for curriculum implementation (Clark & Peterson, Citation1986; Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, Citation2001). Other powerful constructs are pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman, Citation1987), teaching passion (Vallerand et al., Citation2003) and grit (Duckworth, Citation2016). Therefore, studies that employ regression models to examine the relationship between PTTS and their instructional effectiveness are expected to have significant constants to signal the managerial implication of the other aforementioned powerful constructs (Hair et al., Citation2010). Hence, re-examining the nexus is important to affirm the actual relationship and to appropriately direct the development of teacher education frameworks and the pedagogical training given to PTs on various initial teacher education programmes. Therefore, using the same cohort (PMTs used in Asare, Citation2020) in an ex-post facto research, this study predicts PMTs’ instructional effectiveness through their teaching self-efficacy about the off-campus teaching practicum.

2. Research questions

Implicit in the literature gaps are the following research questions:

What is preservice management teachers’ level of instructional effectiveness?

What is the nexus between preservice management teachers’ teaching self-efficacy (instructional strategies, classroom management and student engagement) and instructional effectiveness?

3. Literature review

3.1. Conceptualising preservice teachers’ instructional effectiveness

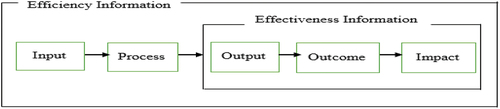

Effectiveness and efficiency, as managerial terms, are common measures of organisational performance (Mouzas, Citation2006; Robbins, Citation2000). Whilst effectiveness is concerned with achieving results, efficiency is related to the use of least resources to achieve results. Again, effectiveness is concerned with management as an outcome factor, and efficiency is the relationship between the input and process factors (Low, Citation2000). This is illustrated in Figure .

Figure 1. Chain of effects

The concept of effectiveness has since been adopted in various fields of study such as teaching. In teaching, effectiveness is conceptualised in several ways. For instance, Korpershoek et al. (Citation2016) stated: “effective teaching is the degree to which teachers are successful in accomplishing their educational objectives” (p. 7). Coe et al. (Citation2014) view effective teaching as something, which leads to improved student achievement using outcomes that matter to their future success. This view of teacher effectiveness limits it to product or output conception. The output conception is defined as “all those educational outcomes which are desired by teachers and which form the basis of either a teacher’s planning of the learning activities and or of objectives or criteria which can be used to consider and monitor effectiveness” (Kyriacou, Citation1995, p. 11). This measure of effectiveness to a large extent is erroneous and leaves much to be desired about the actual efforts of the teacher. For instance, students’ academic achievement also depends on their attitude towards learning (Nja et al., Citation2022; Segarra & Julià, Citation2022). Since in business concerns the efforts of workers are directed towards materials and machines, the output measurement is much desired than in the school setting. Hence, the output dimension of teacher effectiveness can lead to wrong decisions about teacher effectiveness.

Campbell et al. (Citation2005) defined teacher effectiveness as “the impact that classroom factors such as teaching methods, teacher expectations, classroom organisations and use of classroom resources, have on students’ performance” (p. 3). This definition pays particular attention to the process of teaching and identifies the efforts of the teacher towards students’ learning. The input factor, commonly referred to as teacher quality, is what is explained by Goe et al. (Citation2008) as what teachers bring to teaching. This is generally measured by teacher background, beliefs (in this study PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy), expectations, experiences, pedagogical content knowledge, certification and educational attainment. The activities of the teacher (process) must be examined to reasonably judge teaching effectiveness. The current study, therefore, examined the instructional effectiveness of PMTs based on their instructional activities and determined the influence of their teaching self-efficacy on their instructional effectiveness.

3.2. Empirical literature

Several studies have been conducted to assess the level of PTTS. Literature shows that PTs are either highly (e.g., Asare, Citation2020; Balci et al., Citation2019; Coffie & Doe, Citation2019; Farhadiba & Wulyani, Citation2020; Kaku & Arthur, Citation2021; Kwarteng & Sappor, Citation2021; Patterson & Farmer, Citation2018; Yidana & Asare, Citation2021) or moderately (e.g., Dumancic, Citation2020) efficacious to teach. Yidana and Asare (Citation2021) further added that PTs (who majored in Management, Accounting, Economics, and Social Studies) exhibited high behavioural, emotional and cognitive engagement efficacies. In all these aforementioned studies, a focus was not placed on the influence of PTTS on their instructional effectiveness. Yet, conclusions were made that the PTs who were assessed would achieve instructional effectiveness.

The few available literature (Barnes, Citation2000; Bray-Clark & Bates, Citation2003; Gibbs, Citation2003; Klassen & Tze, Citation2014; Sehgal et al., Citation2017) provided scanty and contradictory empirical evidence on the relationship between PTTS and instructional effectiveness. For instance, at the University of South Carolina, Barnes (Citation2000) examined the relationship between self-efficacy and teaching effectiveness among 18 preservice music teachers with the use of a self-evaluation teaching effectiveness scale. The study revealed that individual and group means both for PTs and experienced educators’ ratings of teaching effectiveness increased while PTs’ levels of self-efficacy declined. The cross-tabulation analysis showed that the increase in teaching effectiveness was unrelated with their high levels of teaching self-efficacy. This evidence seems to suggest that teaching self-efficacy is not an important psychological factor that must be emphasised in teacher education institutions and discussions on quality education.

In New Zealand, Gibbs (Citation2003), through a review of the literature, concluded that teachers’ personal sense of control and their self-efficacy impact how they think, feel and teach. Hence, recommended that teacher education should focus less on knowledge and skills and more on developing teachers’ teaching self-efficacy and thought control over their actions for teaching effectiveness. Similarly, in USA, Bray-Clark and Bates (Citation2003), through a review of the literature, argued that the framework of teacher professional development should include teacher self-efficacy as part of the training designs to improve teacher competence and student outcomes.

Klassen and Tze (Citation2014) analysed 43 studies that represented 9,216 participants to identify the overall effect size between the two variables. The meta-analysis revealed a significant but small effect size between overall psychological characteristics (personality and self-efficacy) and teaching effectiveness. The strongest effect was self-efficacy on evaluated teaching performance. The authors noted that existing studies mainly focused on self-reported measures. In India, Sehgal et al. (Citation2017) explored the relationship between self-efficacy (collaboration and principal leadership) and teacher effectiveness (teachers’ role in regulating students’ learning, facilitating teacher-student interactions, and delivery of course information). Whereas 575 teachers responded to teacher self-efficacy, 6,020 students responded to teacher effectiveness. Findings from the study showed a positive relationship between teacher self-efficacy and two dimensions of teacher effectiveness (excluding delivery of course information).

Aside from the contradictory findings, the review of the literature identified other gaps in the extant studies in terms of the measurement of instructional effectiveness, the focus on self-efficacy in predicting instructional effectiveness, and claims by researchers about the relationship between teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness. It was realised that some of the studies (e.g., Barnes, Citation2000; Klassen & Tze, Citation2014; Sehgal et al., Citation2017) measured teachers’ instructional effectiveness either through the teachers’ own self-report or the perception of their students. There was a tendency for the teachers to claim that they are effective when they are not effective. Also, the students cannot be assumed to have the capabilities to judge the expertise of their teachers. These measurement issues limit the validity of extant findings. Therefore, the current study was important in that it measured PTs’ instructional effectiveness through experts’ judgements. These experts sat in the classrooms of the PMTs and observed and scored their teaching.

Most of the studies (Bray-Clark & Bates, Citation2003; Gibbs, Citation2003; Klassen & Tze, Citation2014; Sehgal et al., Citation2017) focused on PTs’ general teaching self-efficacy and did not pay attention to the specific efficacy factors and their relationship with teachers’ instructional effectiveness. This was important to communicate the contributory power of each efficacy dimension for a focused teacher training programme. The current study addressed this issue with a focus on regression analyses. Again, some of the studies assumed without statistical evidence that PTTS can predict their instructional effectiveness (Asare, Citation2020; Bray-Clark & Bates, Citation2003; Gibbs, Citation2003). Even though there is the possibility for this to be true, it is only appropriate for empirical evidence to be provided. This was also addressed in the current study. Based on the gaps identified, the current study was carried out through the ex-post facto design.

4. Research methods and participants

4.1. Research design

The study employed the ex-post facto design to study the influence of PTTS on their instructional effectiveness. The term ex-post facto signifies “from what has happened” or “from after the event” (Cohen et al., Citation2018; Silva, Citation2012). The design was appropriate for the current study in that the study examined two variables: teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness of PMTs, which had already occurred.

4.2. Population, sources of data and selection of cases

The population for this study comprised all PMTs (N = 119) who had completed their teaching practice for the 2019–2020 academic year. This cohort became the focus of the current study because the first author had already gathered a complete dataset on their teaching self-efficacy and their instructional effectiveness data was obtained from the Centre for Teacher Professional Development, University of Cape Coast.

All 119 PMTs were involved in the study through the census method. The use of the census method was based on three key reasons. First, the study sought to achieve high accuracy in predicting their instructional effectiveness devoid of sampling errors; this is a key issue noted by Kothari (Citation2004). Next, in a predictive study such as this, Field (Citation2018) recommended that the sample should be large, that is, greater than 30 cases for the use of parametric statistics. The larger the sample, the higher the predictive accuracy (Field, Citation2018). Finally, 119 valid secondary data were obtained on both variables; hence, there was no justifiable reason to exclude any case. The data was gathered under the approval of the Institutional Review Board, University of Cape Coast, with reference number UCCIRB/CES/2020/06 on 29 May 2020.

4.3. Instrumentation

Asare (Citation2020) adapted the Teacher Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES), originally developed by Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (Citation2001) to a five-point Likert-type questionnaire to gather data on PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy. It was structured into two parts: the demographic characteristics of PTs, and their teaching self-efficacy. The demographic details, relevant to this current study, were sex and age. The PTTS details covered instructional strategies, classroom management and student engagement efficacies. The TSES was used by other scholars (e.g., Berg & Smith, Citation2018; Brown et al., Citation2015; Pendergast et al., Citation2011) to gather teaching efficacy data from PTs due to its unified factor structure (Duffin et al., Citation2012). Its high item homogeneity makes “better theoretical sense” (Shachar et al., Citation2013, p. 286). Hence, its adaptation to suit the context of the current study.

4.3.1. Validity and reliability

The content validity of the adapted TSES was examined by Asare (Citation2020) before the instrument was used to gather the teaching self-efficacy data. Also, the author examined the construct validity for the aforementioned variable through confirmatory factor analysis. All the items, measuring the specific subscales of the variable loaded above the minimum threshold of .5 as suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2019).

Finally, Asare (Citation2020) examined reliability through the use of Cronbach’s alpha and obtained a minimum alpha value of .88, which suggested that the instrument was good. However, the nature of the multidimensionality of the TSES limits the functionality of Cronbach’s alpha. Hayes and Coutts (Citation2020) indicated that the use of Cronbach’s alpha for multidimensional scales may generate wrong estimates of the instrument’s reliability. Therefore, to confirm the already generated reliability estimates, the McDonald omega proposed by Hayes and Coutts (Citation2020) was computed. Table provides the omega estimates alongside the Cronbach’s alpha, as generated by Asare (Citation2020).

Table 1. Comparing Reliability Estimates of McDonald’s Omega with Cronbach’s Alpha

As can be seen from Table , both Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega yielded similar results. Therefore, the self-efficacy data gathered from Asare (Citation2020) was good and was used to predict the instructional effectiveness of the PMTs.

4.4. Empirical models

Simple linear and multiple linear models were developed to examine the influence of PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy about the off-campus teaching practice on their off-campus instructional effectiveness. The PMTs’ instructional effectiveness (criterion variable) was measured by the average scores the University practicum supervisors awarded to them as they (supervisors) observed their (PMTs) teaching during the school experience. These were the same scores submitted to the Centre for Teacher Professional Development, University of Cape Coast, to determine their teaching success or failure. Supervisors’ observations and the scores they awarded on PMTs’ teaching focused on predetermined guidelines stipulated by the university. These guidelines constitute lesson plan preparation, teaching methodology and delivery, classroom organisation and management, and professional commitment. These areas have been noted to influence the development of teaching self-efficacy in teacher education institutions (Velthuis et al., Citation2013). The models were formulated as follows:

IE = f (SEFF)

IE = f (ISE)

IE = f (CME)

IE = f (SEE)

IE = f (SEE, Sex, Age)

Where,

IE = Instructional Effectiveness

SEFF = Self-efficacy

ISE = Instructional Strategies Efficacy

CME = Classroom Management Efficacy

SEE = Student Engagement Efficacy

Sex = Sex

Age = Age

= Constant

,

,

= Unstandardised Regression Coefficients

5. Data analysis

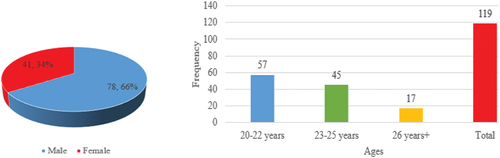

Frequency and percentage were used to analyse the respondents’ demographics (sex and age). The results generated were reported through the use of a pie chart (for sex) and a bar graph (for age). The examination of the instructional effectiveness of the PTs followed the grading standard laid down by the University of Cape Coast. The grading standard was used to judge their level of instructional effectiveness. The standard is as follows: 80–100 (excellent); 75–79 (very good); 70–74 (good); 65–69 (very satisfactory); 60–64 (satisfactory); 55–59 (very fair); 50–54 (fair); and 0–49 (unsatisfactory). Hence, frequency distribution was used to determine the proportions of PMTs that fell in each of the performance categories. Independent samples t-test and one-way ANOVA examined the sensitivity of PMTs’ instructional effectiveness to their sex and age respectively. Finally, linear regressions examined the influence of PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy on their instructional effectiveness.

6. Results

6.1. Overview

In all, 119 valid secondary data on PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy and their instructional effectiveness were obtained. The subsequent sections present results on their demography, level of instructional effectiveness and the influence of their teaching self-efficacy on their instructional effectiveness.

6.2. Demography of respondents

The study focused on two important demographic variables of the PMTs: sex and age. The sex variable helped to appreciate the instructional effectiveness of both the male and female PTs. These are student-teachers who have received the same teacher education training from the University of Cape Coast. They were, therefore, expected to demonstrate the same or similar level of instructional effectiveness. Figure presents the results of the PMTs’ characteristics.

Figure 2. Results of preservice management teachers’ sex and age

The male PMTs were almost twice (n = 78, 66%) the number of their female counterparts, an observation that is common in educational institutions in Ghana. In the African context, especially Ghana, one might erroneously think that male teachers are likely to be confident to teach; therefore, if self-efficacy influences instructional effectiveness, then their instructional effectiveness is likely to be higher than their female counterparts. Therefore, differences in instructional effectiveness based on sex were investigated.

The PMTs were distributed among three age groups as shown in Figure . The majority of them (n = 57, 47.9%) were distributed in the age group of 20–22 years. The age group of 26 years+ had the least membership (n = 17, 14.3%). The differences in their ages might influence their level of instructional effectiveness. Also,this observation was investigated.

6.3. Preservice management teachers’ level of instructional effectiveness

Teaching effectiveness was assessed through PMTs’ off-campus teaching performance. Table presents the descriptive results.

Table 2. Preservice Management Teachers’ Level of Instructional Effectiveness

The general instructional effectiveness of the PMTs was very good (n = 77, 64.7%). The majority (n = 106, 89.1%) of them gave a very good to excellent execution of the teaching tasks. Even those (n = 13, 109%) who were not rated as very good to excellent, had good teaching performance (70–74). Therefore, the sensitivity of their overall instructional effectiveness to their age was examined through the one-way ANOVA. The results are presented in Table .

Table 3. Differences in Preservice Management Teachers’ Instructional Effectiveness based on Sex and Age

The independent samples t-test shows that there is no statistically significant difference in the male (M = 77.59, SD = 2.29) and female (M = 77.56, SD = 2.83) PMTs’ instructional effectiveness, t(117) = .060, p = .952 (two-tailed). By these results, instructional effectiveness is not sensitive to sex. The ANOVA test indicates no significant difference in instructional effectiveness based on age, F(2, 116) = .015, p = .985.

6.4. Influence of preservice management teachers’ teaching self-efficacy on their instructional effectiveness

The research question formulated for the study was to examine if PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy can predict their instructional effectiveness. Table presents the correlation results of the examination of the nature and degree of relationship among the variables and the assessment of the multicollinearity assumption for the regression.

Table 4. Correlation Matrix Results for Dependent and Independent Variables

Table shows a statistically strong positive relationship among the subscales of the self-efficacy variables. For example, the relationship between ISE, and CME was positive [r (119) = .827, p < .001]; ISE and SEE was positive [r (119) = .779, p < .001]; and CME and SEE was positive [r (119) = .791, p < .001]. All the teaching self-efficacy sub-constructs are significantly related to their main construct (self-efficacy). Apart from the SEE, which showed a significant positive relationship with instructional effectiveness [r (119) = .203, p < .001], there was no relationship between ISE and instructional effectiveness [r (119) = −.142, p > .05]; CME and instructional effectiveness [r (119) = −.137, p > .05]. The correlation results suggest that only SEE is likely to predict instructional effectiveness in the regression models.

Next was the assessment of multicollinearity. Multicollinearity is evident when the correlation between any two of the variables exceeds 70% (Anderson et al., Citation2011). It is clear that all the teaching self-efficacy sub-constructs strongly correlated among themselves. The least correlation can be seen between ISE and SEE (r = .779). Hence, separate models were used to assess the predictive power of the self-efficacy sub-constructs on instructional effectiveness. Table presents the regression results.

Table 5. Regression of Preservice Management Teachers’ Self-efficacy, Self-efficacy Factors and Demography on Instructional Effectiveness

The assessment of Model 1 shows that PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy on their instructional effectiveness is not significant, F = 3.607, p = .06. This means that PMTs’ general teaching self-efficacy is not a good predictor of their instructional effectiveness. The non-significant influence of the overall teaching self-efficacy construct on instructional effectiveness made the researchers focus their attention on the specific sub-constructs to determine if any of them could predict instructional effectiveness. This can be seen in Models 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Models 2 and 3 predict the instructional effectiveness of the PMTs’ through ISE and CME. Again, the statistics for Models 2 (F = 2.409, p = .123) and 3 (F = 2.232, p = .138) show that the models are not good for the purpose because the coefficients of the predictors are not statistically significant. Only the regression constants are statistically significant (p < .05). Models 1, 2, and 3 convey the managerial implication of the significant constants, highlighting the relevance of other powerful constructs (e.g., pedagogical content knowledge, motivation) that have been found to influence instructional effectiveness.

Model 4 focuses on the predictive power of PMTs’ SEE on their instructional effectiveness. This model shows uniqueness in results as compared with Models 1, 2 and 3. The F statistic (5.046) and the level of significance (p = .027) cannot deny the relationship which exists between SEE and instructional effectiveness. By these estimates, Model 4 is fit for purpose. This means that PMTs’ SEE predicts their instructional effectiveness. Based on the aforementioned estimates of Model 4, the nature and degree of influence could be studied in the Model. It can be seen that there is a positive influence of PMTs’ SEE on their instructional effectiveness. A one-percent increase in the level of PMTs’ SEE efficacy will result in a .040 increase in their level of instructional effectiveness. The R2 (.041) of the Model shows that PMTs’ SEE explains 4.1% of the variation in their instructional effectiveness. Even though the variation explained by the predictor variable is relatively small, this is a common phenomenon observed with regression models (Wooldridge, Citation2005).

The fitted Model 4 equation is as follows:

Model 5 examines if the demographic characteristics of the PMTs could enhance the statistical estimates in Model 4. Hence, the sex and gender of the PMTs were added to Model 4 to generate Model 5. The F statistic (1.690) and the p-value (.173) did not consider the demographic variables to be relevant in the model. As it can be seen, it is only the SEE variable that remains significant. Hence, Model 4 is the best model to predict PMTs’ instructional effectiveness.

7. Discussion

The study sought to predict PMTs’ off-campus instructional effectiveness through their teaching self-efficacy. This was to highlight the relevance of teaching self-efficacy to the achievement of classroom instructional objectives and subsequently its inclusion in the frameworks for teacher education and training. It must be emphasised that the secondary data existed before the outbreak of the covid pandemic in Ghana. Hence, the covid did not influence the data and the findings. The study found that the PMTs demonstrated high instructional effectiveness during their school experience. Further, findings from the regression analyses indicated that PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy as a whole did not influence their instructional effectiveness. However, the student engagement component of their teaching self-efficacy significantly influenced their instructional effectiveness. This means that an increase in PMTs’ student engagement efficacy will increase their instructional effectiveness. By implication, any teacher education programme that deemphasizes PT’s development of engagement efficacy is sterile.

The significant influence of PMTs’ student engagement efficacy on their instructional effectiveness is a novel finding when compared with previous studies (Barnes, Citation2000; Bray-Clark & Bates, Citation2003; Gibbs, Citation2003; Klassen & Tze, Citation2014; Sehgal et al., Citation2017) that examined the relationship between teachers’ teaching self-efficacy and their teaching effectiveness. The novelty of the current finding hinges on three important pillars: adopted research approach, measurement of predictor and criterion (PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness) variables and level of statistical focus.

Based on the research approach, the study employed the quantitative approach to establish the relationship between teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness, which found student engagement efficacy as a significant predictor and not the whole teaching self-efficacy construct. A study of this nature requires a quantitative approach to provide the intrinsic relationship between teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness. Therefore, the current finding disconfirms the previous findings that were obtained by Gibbs (Citation2003) and Bray-Clark and Bates (Citation2003). These identified studies (Bray-Clark & Bates, Citation2003; Gibbs, Citation2003) employed qualitative approaches to drive their findings that teaching self-efficacy is relevant for teaching. Therefore, their recommendation that teaching self-efficacy should be incorporated into teacher education frameworks for the education and training of preservice teachers is not well grounded. The current study did not find a significant relationship between PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy (as a whole construct) and instructional effectiveness through the quantitative approach. Also, the suggestion made by Gibbs (Citation2003) that teacher educators should focus less on knowledge and skills when developing PTs cannot be upheld. This is because the review of literature identified pedagogical content knowledge, teaching passion and grit as other powerful constructs for instructional effectiveness. The literature indicated that, as guided by Hair et al. (Citation2010), significant regression constants would be obtained due to these powerful constructs. In all the five models that were developed, the regression constants were indeed significant. Teacher knowledge and by extension skills cannot be given less focus because self-efficacy belief is influenced by content and pedagogy taught at teacher education institutions (Velthuis et al., Citation2013). In support, content knowledge has been found to influence confidence (self-efficacy; DeCleene Huber et al., Citation2015; Wongwiwatthananukit et al., Citation2002). In the current study, the significant regression constants portray the managerial implication of teacher knowledge and skills (Hair et al., Citation2010). It is argued that the validity of a research methodology will determine the validity of the findings. The current study described and reported the quantitative methods employed to obtain the findings. The findings are, therefore, based on the methods employed, and the methods provide evidence for the findings.

Although, Barnes (Citation2000) found that there is no relationship between teachers’ teaching self-efficacy and teaching effectiveness, which the current study generally affirms, the measurement of the teaching effectiveness variable appears to lack validity. Generally, previous studies (e.g., Barnes, Citation2000; Klassen & Tze, Citation2014) measured teaching effectiveness and analysed its data based on a self-report or evaluation. In the case of Barnes (Citation2000), empirical data that were collected were based on self-reportage. Also, Klassen and Tze’s (Citation2014) study was a meta-analysis, in which teachers assessed their instructional effectiveness. Klassen and Tze (Citation2014) remarked, at the time of their study, that previous studies on the relationship between teachers’ teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness were based on self-reported measures. It appears that there is lack of objectivity in the measurement of instructional effectiveness in previous studies. This might not help in discovering the true instructional effectiveness of teachers or PTs. Hence, the validity of the nexus between teachers’ or PTs’ teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness cannot strongly influence the development of teacher education frameworks for the training of preservice teachers. In an attempt to strengthen the validity in the measurement of instructional effectiveness, Sehgal et al. (Citation2017) used students to assess their teachers and found a positive relationship between teacher self-efficacy and teacher effectiveness. Obviously, the non-significant relationship between PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness in the current study fails to confirm the findings obtained by Sehgal et al. (Citation2017). Students are not experts to assess the instructional effectiveness of their teachers. They might lack a clear understanding of the components of instructional effectiveness. Hence, their use in Sehgal et al.’s (Citation2017) study seems inadequate in supporting the findings. As a departure, the current study assessed PMTs using experts in teacher education and found no relationship between their teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness. Aside from the differences in respondent type for the assessment of instructional effectiveness, the measurement of teacher effectiveness in the current study was quite different from that of Sehgal et al. (Citation2017). Sehgal et al. focused on teachers’ roles in regulating students’ learning, facilitating teacher-student interactions, and delivery of course information. The current study covered areas such as lesson plan preparation, teaching methodology and delivery, classroom organisation and management, and professional commitment, hence, the possible differences in the findings. It appears that the current study covered more areas of the work of teachers in measuring PTs’ instructional effectiveness.

Finally, the level of the statistical focus in this study sets it apart from the previous aforementioned studies. The current study did not only analyse the overall PMTs’ teaching self-efficacy on their instructional effectiveness but also examined the influence of their specific teaching self-efficacies (instructional strategies, classroom management and student engagement) on their instructional effectiveness. This assisted the study to discover that PMT’s student engagement efficacy is the most significant contributor to their instructional effectiveness. A more valid ground is, therefore, provided to include teaching self-efficacy, specifically, student engagement efficacy into the frameworks for teacher education and training.

8. Conclusions

The study found that the PMTs’ (who were earlier found to be highly efficacious) instructional effectiveness was very good, an indication that they possessed the quality to professionally teach and transmit content knowledge to their prospective students. Again, teacher confidence to engage students was found as a significant factor for instructional effectiveness. This stems from the fact that PMTs’ student engagement efficacy was the only predictor of their instructional effectiveness. Their instructional strategies and classroom management efficacies could not predict their instructional effectiveness. Therefore, PTTS to engage their students seems to supplant other efficacies needed to execute the numerous classroom practices. This appears to send a strong signal to various teacher educators to focus on building PTs’ engagement efficacy. The predominant limitation was the researchers’ inability to control certain factors, which might have influenced the capability of the PTs to teach between the time the self-efficacy data was collected and the time they undertook the off-campus teaching practice.

9. Recommendations

Given the findings of the current study, it is recommended that teacher educators should continuously build the engagement efficacy of PTs. This can be done by using class policies to ensure that PTs do not participate in dysfunctional activities during lectures as well as absent themselves from lectures. Also, teacher educators should demonstrate interest and passion for teaching to ignite PTs’ interest in participating in lectures. Student-centred pedagogies should be practically taught for PTs to appreciate their applications. PTs should be challenged to go beyond teaching standards. Finally, future studies can gather a relatively large dataset across teacher education programmes to re-examine the nexus.

Data Availability

The data which drive the conclusions of the study are embedded in the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the Centre for Teacher Professional Development, University of Cape Coast, for making available PMTs’ teaching performance data for the execution of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Prince Yeboah Asare

Prince Yeboah Asare is a Management Educator at the University of Cape Coast, Ghana, who holds PhD in Management Education, MPhil in Curriculum and Teaching and a Bachelor’s Degree in Management Education. He started teaching at the aforementioned university as a graduate research assistant in 2016. Currently, he is a lecturer with research interests in Management Teacher Education, Curriculum and Teaching, Research Methods and Statistics. This current paper is one of his series, which explored preservice teachers’ teaching self-efficacy and their instructional effectiveness. His previous related published papers explored preservice teachers’ emotional, behavioural and cognitive engagement efficacy, and how preservice teachers’ teaching self-efficacy influences their teaching anxiety.

References

- Albion, P. R. (1999). Self-efficacy beliefs as an indicator of teachers’ preparedness for teaching with technology. In J. Price et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of society for information technology and teacher education international conference (pp. 1602–17). Chesapeake, VA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

- Anderson, D. R., Sweeney, D. J., & Williams, T. A. (2011). Statistics for business and economics. South-Western, Cengage Learning.

- Asare, P. Y. (2020). Preservice management teachers’ self-efficacy and anxiety about teaching practicum. Unpublished doctoral thesis submitted to the Department of Business and Social Sciences Education, University of Cape.

- Balci, O., Sanal, F., & Uguten, D. S. (2019). An investigation of pre-service English language teaching teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. International Journal of Modern Education Studies, 3(1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.51383/ijonmes.2019.35

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

- Barnes, G. V. (2000). Self-efficacy and teaching effectiveness. Journal of String Research, 1, 627–643. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Barnes%2C+G.+V.+%282000%29.+Self-efficacy+and+teaching+effectiveness.+Journal+of+String+Research%2C+1%2C+627%E2%80%93643.&btnG=

- Berg, D. A., & Smith, L. F. (2018). The effect of school-based experience on preservice teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. Issues in Educational Research, 28(3), 530–544. http://www.iier.org.au/iier28/berg.pdf

- Bray-Clark, N., & Bates, R. (2003). Self-efficacy beliefs and teacher effectiveness: Implications for professional development. Professional Educator, 26(1), 13–22. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ842387.pdf

- Brown, A. L., Lee, J., & Collins, D. (2015). Does student teaching matter? Investigating pre-service teachers’ sense of efficacy and preparedness. Teaching Education, 26(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2014.957666

- Cahill, A. S. (2016). Understanding the self-efficacy beliefs of preservice learning and behavioral specialists during their practicum, field-based, and student teaching semesters. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/608

- Campbell, R. J., Kyriakides, L., Muijs, R. D., & Robinson, W. (2005). Differential teacher Effectiveness: Towards a model for research and teacher appraisal. Oxford Review of Education, 29(3), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980307440

- Clark, C. M., & Peterson, P. L. (1986). Teachers’ thought processes. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Third Handbook of Research on Teaching (pp. 255–296). Macmillan.

- Coe, R., Aloisi, C., Higgins, S., & Major, L. E. (2014). What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research. https://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/What-Makes-Great-Teaching-REPORT.pdf

- Coffie, I. S., & Doe, N. G. (2019). Preservice teachers’ self-efficacy in the teaching of science at basic schools in Ghana. Journal of Education and Practice, 10(22), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.7176/JEP

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th) ed.). Routledge.

- DeCleene Huber, K. E., Nichols, A., Bowman, K., Hershberger, J., Marquis, J., Murphy, T., Pierce, C., & Sanders, C. (2015). The correlation between confidence and knowledge of evidence-based practice among occupational therapy students. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 3(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1142

- Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance (Vol. 234). Scribner.

- Duffin, L. C., French, B. F., & Patrick, H. (2012). The teachers’ sense of efficacy scale: Confirming the factor structure with beginning pre-service teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(6), 827–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.03.004

- Dumancic, D. (Ed.). (2020). Preservice teacher self-efficacy beliefs. Proceedings from University of Zadar. University of Zadar.

- Farhadiba, D., & Wulyani, A. N. (2020). KnE Social Sciences,41 40–49. https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v4i4.6464

- Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using SPSS. Sage Publications.

- Frey, K., & Widmer, T. (2009). The role of efficiency analysis in legislative reforms in Switzerland. Potsdam, Germany, 5th ECPR General Conference, September 12, 2009. http://www.zora.uzh.ch.

- Gibbs, C. (2003). Explaining effective teaching: Self-efficacy and thought control of action.The Journal of Educational Enquiry, 4(2), 1–14. https://ojs.unisa.edu.au/index.php/EDEQ/article/view/520

- Goe, L., Bell, C., & Little, O. (2008). Approaches to evaluating teacher effectiveness: A research synthesis. National Comprehensive Centre for Teacher Quality.

- Graham, S., Harris, K. R., Fink, B., & MacArthur, C. A. (2001). Teacher efficacy in writing: A construct validation with primary grade teachers. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5(2), 177–202. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532799Xssr0502_3

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th) ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th) ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Hayes, A. F., & Coutts, J. J. (2020). Use omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But …. Communication Methods and Measures, 14(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

- Henson. K, R. (2001). Teacher self-efficacy: Substantive implications and measurement. Dilemmas, keynote address given at the annual meeting of the Educational Research Exchange. A & M University.

- Kaku, D. W., & Arthur, F. (2021). Pre-service economics teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs in teaching economics. International Journal of Innovative Research and Development, 10(3), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.24940/ijird/2021/v10/i3/158459-390043-1-SM

- Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001

- Knoblauch, D., & Hoy, A. W. (2008). Maybe I can teach those kids. The influence of contextual factors on student teachers’ efficacy beliefs. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.05.005

- Koross, R. (2016). The student teachers’ experiences during teaching practice and its impact on their perception of the teaching profession. IRA International Journal of Education and Multidisciplinary Studies, 5(2), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.21013/jems.v5.n2.p3

- Korpershoek, H., Harms, T., de Boer, H., van Kuijk, M., & Doolaard, S. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of classroom management strategies and classroom management programs on students’ academic, behavioral, emotional, and motivational outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 86(3), 643–680. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626799

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Age International (P) Ltd., Publishers.

- Kwarteng, J. T., & Sappor, P. (2021). Hindawi Education Research International, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9140161

- Kyriacou, C. (1995). Effective teaching in schools. Stanley Thornes (Publishers) Ltd.

- Lewin, K. M., & Stuart, J. M. (2003). Insights into the policy and practice of teacher education in low-income countries: The multi-site teacher education research project. British Educational Research Journal, 29(5), 691–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192032000133703

- Low, J. (2000). The value creation index. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(3), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930010377919

- Mouzas, S. (2006). Efficiency versus effectiveness in business networks. Journal of Business Research, 59(10–11), 1124–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.09.018

- Nja, C. O., Orim, R. E., Neji, H. A., Ukwetang, J. O., Uwe, U. E., & Ideba, M. A. (2022). Students’ attitude and academic achievement in a flipped classroom. Heliyon, 8(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08792

- Patterson, T. T., & Farmer, A. (2018). Classroom management self-efficacy of pre-service teachers. World Journal of Educational Research, 5(2), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.22158/wjer.v5n2p134

- Pendergast, D., Garvis, S., & Keogh, J. (2011). Pre-service student-teacher self-efficacy beliefs: An insight into the making of teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(12), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2011v36n12.6

- Reddy, K. R. (2019). Teaching how to teach: Microteaching (a way to build up teaching skills). Journal of Gandaki Medical College-Nepal, 12(1), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.3126/jgmcn.v12i1.22621

- Robbins, S. P. (2000). Managing today. Prentice Hall.

- Segarra, J., & Julià, C. (2022). Mathematics teaching efficacy belief and attitude of pre-service teachers and academic achievement. European Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 10(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.30935/scimath/11381

- Sehgal, P., Nambudiri, R., & Mishra, S. K. (2017). Teacher effectiveness through self-efficacy, collaboration and principal leadership. International Journal of Educational Management, 505–517. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-05-2016-0090

- Senler, B., & Sungur, S. (2010). Pre-service science teachers’ teaching self-efficacy: A case from Turkey. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 771–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.232

- Shachar, I., Aderka, I. M., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2013). The factor structure of the Liebowitz social anxiety scale for children and adolescents: Development of a brief version. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 45(3), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0398-2

- Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

- Silva, C. N. (2012). Encyclopaedia of research design: Ex post facto study. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing and elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

- Tschannen-Moran, M., Woolfolk Hoy, A., & Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Research, 68(2), 202–248. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543068002202

- Vallerand, R. J., Blanchard, C., Mageau, G. A., Koestner, R., Ratelle, C., Léonard, M., Gagne, M., & Marsolais, J. (2003). Les passions de l’ame: On obsessive and harmonious passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(4), 756–767. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.756

- Velthuis, C., Fisser, P., & Pieters, J. (2013). Teacher training and pre-service primary teachers’ self-efficacy for science teaching. The Association for Science Teacher Education, 25(4), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-013-9363-y

- Wongwiwatthananukit, S., Newton, G. D., & Popovich, N. G. (2002). Development and validation of an instrument to assess the self-confidence of students enrolled in the advanced pharmacy practice experience situations. Am J Pharm Educ, 66(1), 5–19. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242083579

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2005). Simple solutions to the initial conditions problem in dynamic, non-linear panel data models with unobserved heterogeneity. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 20(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.770

- Yidana, M. B., & Asare, P. Y. (2021). Preservice teachers’ behavioural, emotional and cognitive engagement efficacy. International Journal of Education and Research, 9(3), 233–248. https://www.ijern.com/journal/2021/March-2021/18.pdf

- Zuya, H. E., Kwalat, S. K., & Attah, B. G. (2016). Pre-service teachers’ mathematics self-efficacy and mathematics teaching self-efficacy. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(14), 93–98. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1102977.pdf