Abstract

Assessment is a crucial and essential component of successful instruction and learning. As a result, teachers must examine their actions in the classroom through a process of reflective practices (self-observation and self-evaluation) and think about why they do it and if it works. This essay examines the reflective practices of Ghanaian teacher educators regarding the evaluation of social studies and history curricula. It made use of the sequential explanatory mixed method as a methodology drawn from questionnaires, interviews and document reviews. The findings disclosed that teacher educators in Ghana’s colleges of education have low efficacy and poor reflective practices when it comes to affective domain assessment. The study suggests that the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the National Council for Tertiary Education (NCTE) should ramp up the instruction of the methods for evaluating the affective domain in coordination with Ghanaian universities. For Social Studies teacher educators, consistent professional development programs on the methods for assessing the affective domain should be organised. The universities in Ghana should train Social Studies History teacher educators in the field in the area of measurement and evaluation with particular emphasis on the construction of appropriate test items for determining expected outcomes.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Over the past two decades, there has been an increase in global interest in teacher expertise and curriculum materials, two essential components of the educational system. The fact that the majority of methods to curriculum, instruction, and assessment are based on ideas and models that have not kept up with contemporary understanding of how individuals learn is arguably beyond debate. They were created using implicit and extremely constrained ideas of learning. When it comes to subject matter knowledge domains, those concepts frequently lack coherence, are out of date, and are poorly defined. From personal experience, observation, and context validation or analysis, it is clear that curriculum material differs depending on the institution (university) that the instructor attended, which results in a situation where the Social Studies curricula in the institutions are out of sync. The social studies subject taught in universities and colleges of education are not aligned. Therefore, curriculum orientation to the examining institution or university affects students’ performance and how teacher educators assess their students. The paucity of research on this issue constitutes the basic problem why the researcher deemed it necessary to analyse teachers’ knowledge of curriculum materials and an assessment of Social Studies tuition in the Colleges of Education in Ghana.

1. Introduction

The Education 2030 Framework for Action and SDG4 are both supported by this assessment framework. Additionally, it is consistent with Ghana’s Education Strategic Plan 2018–2030, which places a high priority on enhancing learning outcomes across the board. The national pre-tertiary education curriculum currently in use represents a paradigm transition from an objective-based curriculum to a standards-based curriculum, which is in line with trends in global curriculum reform. It offers high-quality instruction that helps students gain the knowledge, comprehension, and skills they need to succeed in tertiary education and the job. The curriculum content standards are met when students are able to: communicate effectively in spoken and written language; apply their knowledge and understanding to novel and challenging situations; think creatively and from various angles; value the history and traditions of their family, community, and country; take responsibility; and actively participate in local and global society. An essential element of the new paradigm is assessment improvements inside the curriculum’s learning philosophy. This indicates that an assessment framework is now required in order to coordinate and guide the requirements of the standards-based curriculum through the processes necessary to assure their fulfillment. To facilitate the implementation of the Curriculum Framework, the National Pre-tertiary Learning Assessment Framework was created(National Council for Curriculum and Assessment NaCCA, Citation2020).

Diagnostic, formative, and summative evaluations and assessments are the three basic types used in education. Prior to introducing learners to a new learning area, diagnostic evaluation is helpful in determining their present knowledge and skills and in assisting in the clarification of any misconceptions. While instruction is taking place, formative assessment gives feedback and information during the process. It evaluates how well teachers are doing at presenting the material in a way that promotes learning as well as how well learners are progressing. Summative assessment is an evaluation conducted typically, but not always, at the conclusion of the academic year based on the learner’s cumulative development and accomplishments throughout the course of the year in a particular subject, as well as any end-of-year exams or examinations. Engaging students in reflection on their learning requirements is part of assessment as learning. Teaching and learning practices are improved using the information that students give the teacher(NaCCA, 2019). Here, learners are assisted in fulfilling their roles and taking responsibility for their own learning to increase performance. Learners receive assistance in establishing their own objectives and tracking their development (NaCCA, 2019). Assessment/evaluation places a greater emphasis on students in order to enhance learning and academic performance of students (Crawford, Citation2002), help teachers understand students’ levels of understanding and ability (Bekoe et al., Citation2013), and identify students’ learning issues for remediationKellaghan & Greaney, Citation2001.

There are different assessment methods for assessing students learning. These include class tests, mid-term examinations, class exercises, project work, and oral questions. In educational settings, certain varied tools and methods are employed by educators to measure, evaluate and assess students learning outcomes and progress. These measures are referred to as assessments. The concept of assessment, as used in this paper, refers to the methods or processes used in collecting data on the student learning outcome in teaching and learning. Assessment is now viewed from a modern perspective as a crucial and essential component of successful learning (James & Pedder, Citation2006). Assessment is described by the Ministry of Education’s National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NaCCA) as a systematic process of acquiring and analysing data on students in order to use that data to influence decisions that will improve erudition and learning Ministry of Education, Citation2020a. It encompasses all techniques employed to gauge the level of an individual’s accomplishments (Gronlund, Citation2006). It may consist of formal techniques like extensive state or national assessments as well as less formal classroom activities like tests, group projects, and teaching questioning. It is the act of deciding or creating an opinion after carefully considering something or someone. In other words, it is a method for assessing student achievement in relation to fundamental abilities as well as educational objectives. The main forms of evaluation/assessment are discussed in the ensuing paragraphs.

The diagnostic, formative, and summative evaluations or assessments are the three main types of evaluation recognized by the Ministry of Education in Ghana (2020a, Ministry of Education, Citation2020b). A diagnostic assessment is helpful in determining students’ current knowledge and skills, while a formative assessment offers feedback and information during a teaching and learning process. A summative assessment, on the other hand, is based on the student’s cumulative progress and accomplishments over the course of the school year in a particular subject, as well as any end-of-year tests or examinations Ministry of Education, Citation2020a. Rahman (Citation2016) also noted that school assessment is divided into two constructs: formative and summative assessments. Formative evaluations are typically conducted throughout the erudition and learning process, whereas summative evaluations are showed at the conclusion of a course or after the completion of a particular unit. According to Rahman (Citation2016) and Wiliam and Thompson (Citation2008), the school’s assessment program is one type of formative evaluation. What is valued, what kids are learning, what is assessed, and how it is assessed are all defined by the nature of school evaluation.

School assessment focuses more on learners for varied reasons, as some scholars observe (Bekoe et al., Citation2013; Crawford, Citation2002; Kellaghan & Greaney, Citation2001). They observed that assessment focuses more on students in order to enhance learning and the academic performance of students (Crawford, Citation2002), assist the teacher in knowing the level of appreciating of the students and their capacity level (Bekoe et al., Citation2013), diagnose learning problems of students for remediation Kellaghan & Greaney, Citation2001.

Importantly, there are enormous benefits of evaluations in schools. School evaluations are formative evaluations that help students go from one level to another. Diagnostic measures might be developed to gauge teachers’ and students’ progress occasionally. These diagnostic tests can allow teachers to fix any errors and strengthen students’ deficiencies immediately. The findings of assessments, whether official or informal, are used in the educational scheme by administrators and instructors to guide decisions about student learning and learner promotion (Fook & Sidhu, Citation2010). Additionally, a teacher can spot a student’s faults and build on their strengths and potential (Barley, Citation2013). Teachers can assist students in making more progress in their learning and achieving great results in the central level evaluation by engaging in efficient follow-up activities.

How instructors view school assessment is a sign of how they implement assessment in the classroom (Rahman, Citation2016). Rahman (Citation2016) quoted Black and Wiliam (Citation1998a) in saying that valuation is a crucial component of the education, erudition, and learning process. The results of assessments inform teachers of the thoughts and processes of their students. The level of progress a teacher has made in the teaching and learning processes is determined via assessment. She went on to say that most teachers believe assessments solely serve to gauge students’ learning outcomes and fail to recognise that they also gauge a teacher’s effectiveness. This suggests that evaluation feedback assists the instructor in making an informed choice regarding his or her teaching and learning processes.

In Ghana’s curriculum, Social Studies and History are core and elective disciplines, respectively, and are taught at the basic and secondary levels. At the tertiary level (Colleges of Education and Universities), the disciplines are offered based on students’ choices. A degree (graduate and postgraduate) in any of the universities in Ghana qualifies the holder to practice as a professional or non-professional tutor educator.

It is vital to note that the development of History education has gone through a transformation from the pre-colonial, colonial and postcolonial eras. History was once a core discipline in schools in Ghana until the 1987 educational reforms relegated it to an elective status (Boadu et al., 2020). Since 2007, History has been integrated into subjects such as Social Studies, Citizenship Education, Religious and Moral Education (RME). In 2017. History has been fully integrated into the primary education curriculum (Ministry of Education, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Although it is an elective subject in senior high schools, History is fully integrated into the Social Studies Syllabus of Junior and Senior High schools (Ministry of Education, Citation2020a, Ministry of Education, Citation2020b). At the tertiary level, History appears as an elective subject. It is also integrated into Social Studies which is a core subject. For instance, elements of History and social studies feature in the curriculum of Colleges of Education and universities in Ghana (Adu-Gyamfi & Anderson, Citation2021).

The content of History in secondary schools and Colleges of Education in Ghana focuses on the social-cultural, political and economic History of Ghana, though the secondary school syllabus extends the focus to the History of the civilisations of Africa. As Boadu et al (2020: 180) put it, “the current secondary history curriculum, which has been in operation since September 2010, covers a set of chronologically sequenced themes that reflect multiple perspectives on Ghana and Africa from prehistoric times to 1991.” History teachers are expected to teach students to acquire skills in content-based analysis, interpretation of historical evidence, conducting research, source identification and interpretation, among others (MOE, 2010). Predominantly, the mode of teaching students in History and Social Studies in secondary schools in Ghana as prescribed by the MOE (2010) includes “projects, role play, class discussion, experiments, investigative study and field study” (Boadu et al., 2020: 180).

Additionally, research has shown that Ghanaian teachers prefer to engage in traditional ways of assessing pupils’ learning outcomes which include class exercise, homework and test rather than alternate valuations notably observation, project work and oral presentation (Nabie, Citation2013). Teachers in Ghana basically resort to the technique of employing facts and eliciting questions that require pupils to deduce logical deduction from procedures and not that which requires them to investigate the situation under consideration (Hattori & Saba, Citation2008). On this score, one wonders if teachers actually implement their ideas for evaluation to ensure better teaching and learning, particularly from a Ghanaian perspective.

Reflective practice is an integral part of erudition and therefore emphasis is laid on the training and development of teachers and also teacher professional development (Sellars, 2012). Teachers are trained to reflect on the lessons taught and evaluate them to see the shortcomings and flops, as well as think about ways to improve the lesson if allowed to teach the same lesson again. This is a means teachers employ to assess their lessons thereby helping teachers to improve learning outcomes in the educational ecosystems. Additionally, reflective practice in education is also a means to assess policy and practice with the intent of putting in measures for improvement.

This reading aims to examine service tutors reflective practices regarding the evaluation of Ghanaian social studies and history curricula. Specifically, the discourse assesses teachers’ knowledge of social studies and history curriculum assessment; and their reflective practices. It is significant for Ghana’s MOE, NTCE, NaCCA and other stakeholders for Initial Teacher Education (ITE). The study’s results revealed that a greater number of course coordinators (tutors) in Ghana’s colleges of education included in the study as respondents have low efficacy and poor reflective practices regarding affective domain assessment. Several contextual recommendations are outlined to improve teachers’ efficacy and the History and Social Studies curriculum assessment in colleges of education in Ghana.

2. Concise context of colleges of education in Ghana

Until the 1980s, the Colleges of Education in Ghana operated as Teacher Training Colleges, offering a 3-year and a 4-year Certificate “A” programs Anamuah–Mensah, Citation2006. Later, the Colleges of Education were re-organised into diploma-awarding institutions with affiliations with education-oriented universities in Ghana (Ministry of Education, Ghana, Citation2004). By 2008, all 38 colleges in Ghana were re-organised into Colleges of Education. The Colleges of Education Act, Act 847 of 2012, was accepted to give legal backing to their new rank. With the reorganisation, the Colleges of Education acquired a degree-awarding status. The reorganisation of the focus of the Colleges of Education necessitated the reorganisation of the contents of the various disciplines offered in colleges in Ghana. Consequently, History and Social Studies were re-organised to reflect the contents of those disciplines in universities in Ghana.

Currently, the Colleges of Education in Ghana run three programmes. These are early childhood education, primary education, and junior high school education. Social Studies is a core discipline that features in all these three programmes. As a core subject, it has elements of Geography, History, Music and Dance, Religious and Moral Education, African Studies, and Liberal Studies. In some cases, these subjects are elective courses depending on affiliation to a particular university in Ghana. For instance, some colleges of education study History and Geography as elective subjects if they are affiliated with the University of Ghana. The reading of Social Studies and History in the curricula of colleges of education is crucial to the development of History and Social Studies education at the foundation (basic) level of the educational system in Ghana. This is because the History and Social Studies curricula for the Colleges of Education reflect the contents of the two subjects in early childhood, primary and junior high school education programmes. The study of these subjects is also crucial on the premise that the colleges of education train instructors to teach these disciplines at the basic school level. Thus, History and Social Studies are re-organised to reflect the contents of those disciplines in Ghana’s early childhood education, primary education and junior high school education.

To ensure that the Colleges of Education train quality teacher educators to teach at basic, junior high, and senior high levels in the educational structure in Ghana, Basic research and action research must be a crucial part of teacher preparation, according to a mandate for the colleges of education. A tutor educator is an instructor at a tutor education school who mentors aspiring instructors in three areas, namely subject matter knowledge, teaching methodology, and evaluation, according to Lunenberg et al. (Citation2014). These three components are interconnected within the Ghanaian educational system; however, their relationships and mutual influences are frequently far less obvious than they ought to be. It is important to note that the individual links between the three components are frequently inconsistent, which results in a lack of overall coherence in the educational system.

In sum, the purpose of training pre-service instructors with fundamental knowledge and understanding of valuation as part of the unit at the colleges of education in Ghana is to assist students in advancing their learning, which is a fundamental process in education that is necessary to enhance learning outcomes, and achievement (Brink, Citation2017; Hayward, Citation2015: Mumm et al., Citation2016). It supports student learning, enhances education, and is essential to the teaching-learning process. It was recommended that assessment in schools includes evaluation of learning. As a result, a crucial component of efficient teaching and learning procedures is the use of evaluation to advance students’ learning. According to the NaCCA’s further assertions, an assessment may be formative, summative, diagnostic, or evaluative Ministry of Education, Citation2020a, Ministry of Education, Citation2020b).

3. Literature review

School valuation procedures symbolise the task instructors perform to evaluate and enhance teaching and learning in their classrooms. There have been conflicting results from certain research (Kitta, Citation2014; Zhang & Burry-Stock, Citation2003) on teachers’ evaluation techniques in schools conducted in various regions of the world. For instance, they posited that due to the nature of school assessment demarcated by teaching levels, teacher valuation practices tend to vary largely. For instance, basic school teachers resort mostly to performance assessment, while secondary school teachers bank on paper-pencil tests with an emphasis on quality assessment. Teachers utilise a range of assessment methods to ensure that students’ learning is improved rather than merely depending on assignments, schoolwork, and tests to ascertain students’ understanding, as well as on observation, self-evaluation, and unusual quiz types like those used in Canada (Suurtamm et al., Citation2010).

Assessment of the curriculum includes formative and summative evaluations of students by teachers as well as evaluations from the students themselves. Through the Assess for Learning Model (ALM), Chappuis et al. (Citation2009) explored the five essential elements of high-quality training. “Clear purpose” is the first part. The educator must understand exactly what they are evaluating and why. The assessor must also be aware of who the evaluation will be used to inform. Assessments can help the teacher determine whether the students have a grasp of the content or they can help the student identify their areas of strength or need. “Clear learning target” is the second element. To ensure that every student is aware of what is required for assessment, the instructor must organise learning objectives in writing. Learning targets can be evaluated in a variety of ways, including knowledge, reasoning, performance, and product targets. Utilising a “sound assessment design” is the third component. This indicates that the teacher selects the most appropriate assessment type for a certain learning objective. The fourth element of learning assessment is “effective communication of results.” This means that the teacher must provide students with descriptive feedback to let them know how they are doing with respect to achieving learning objectives. Assessments should receive as much feedback as feasible. Students should be able to communicate their strengths and areas for improvement using the language of the rubrics. “Student involvement in the assessment process” is the final component of assessment for learning. This implies that students should oversee and be accountable for their education. In order for students to self-evaluate and set goals, teachers should design learning objectives that allow for this. Teachers must develop a schedule that allows students to keep track of their progress toward learning objectives. The success of teaching and students depends on using the assessing for learning paradigm. It enables the students to take an active role in their education. Additionally, it guarantees that the teacher may differentiate instruction for each student’s unique learning needs. However, this concept is challenging to implement in physical education classes with a big student population.

Teachers are crucial in identifying pupils’ growth, aptitudes, progress, and achievement. Teachers select the learning objectives to be evaluated, create the evaluation tools, examine the results, communicate their findings, and follow up. It is envisaged that school evaluation will promote individual potential and assure integration of the intellectual, spiritual, emotional, and physical aspects of learning in line with the National Education Philosophy (NEP); (Hassan et al., Citation2013). Teachers are given significant responsibility to create high-quality tests that are in line with learning objectives through the concept of school assessment since they are best suited to evaluate their pupils and have a deeper awareness of the context of the discipline area. (Salmiah, Citation2013).

Educational theorists are convinced that assessment serves three primary purposes namely assessment of learning; valuation for learning; and valuation as learning (Suhaimi et al., Citation2013). While assessment for learning is meant to help teachers decide the best course of action to improve students’ learning, assessment of learning is meant to inform parents or the general public about students’ abilities in relation to the curriculum (Azizi, Citation2010). On the other hand, assessment or evaluation as learning relates to encouraging students to consider the goals of their education. Teaching and learning practices are improved using the information that students give the teacher Ministry of Education, Citation2020a, Ministry of Education, Citation2020b). In order to perform better, learners are helped to assume their roles and take charge of their own learning. Students are helped to create their own objectives and track their developmentMinistry of Education, Citation2020a, Ministry of Education, Citation2020b). Students should keep track of and evaluate their own learning through assessments of learning. To accomplish these goals, teachers can make use of written assessments, projects, portfolios, and other forms of assessment. In conclusion, it can be concluded that evaluation typically emphasises individual learning, learning environment, participating institutions, and learning system.

Clark (Citation2012) and Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007) asserted that assessment is a key technique in teacher education that has been shown to have the pedagogical potential for improving student performance. According to Kitta (Citation2014), there is a strong and positive correlation among learning and valuation during the learning process. Teachers with potential must make sure that school assessment facilitates instruction and learning. This makes understanding what teachers think about assessment and what they do throughout it important.

Unquestionably, most teachers employ curriculum evaluation strategies based on theories and models that have not evolved along with our understanding of how individuals learn today. These methods of curricular assessment were created using implicit and extremely constrained concepts of learning. Those ideas frequently lack a clear separation from areas of subject matter expertise, are fragmented, and are out of date. Some research has been carried out on the assessment practices of teachers globally (Allen et al., Citation2013; Liu et al., Citation2016; Tierney, Citation2013) and in Ghana (Hattori & Saba, Citation2008; Nabie et al., Citation2013). Allen et al. (Citation2013) reported in their study that, education professionals now have the information and abilities to more fully comprehend how school assessment methods affect students’ learning and academic development. This is thanks to perception and assessment techniques. Teachers assess students through tests and other conventional ways, as well as by asking them questions that call for the use of low-order thinking skills, according to some academics (Hattori & Saba, Citation2008; Nabie et al., Citation2013). This paper examines the knowledge and techniques of social studies teacher educators based on this concept. Assessment of curriculum materials. It sought to unearth the data and practices of instructor educators in Social Studies curriculum assessment. This highlights the reflective activities of teacher educators in Ghanaian colleges of education when assessing the social studies curriculum. The goal of reflective practice is to obtain new understandings of oneself and one’s practice by learning from and through experienceFinlay, Citation2008. It necessitates that teachers examine what they do in the classroom, consider why they do it and assess whether it is effective.

3.1. Theoretical review

This paper is guided by the theories of Behaviourism (Pavlov, Citation1927; Skinner, Citation1957; Thorndike, Citation1911), Constructivism (Dewey, Citation1944; Piaget, Citation1967; Vygotsky, Citation1978), and Social Constructivism (Vygotsky, 1986). Behaviourism is suggestive of prescriptive assessment procedures. Behaviourists support structured, teacher-controlled or centred approaches to assessment procedures. To the behaviourist, evaluation is often examination-oriented and high stakes, without instructors direct participation. Constructivism is a philosophy of learning founded on the premise that, by reflecting on our experiences, learners construct their understanding of the world they live in. Constructivism is based on the premise that learners make their understanding of the world they live in. Hence, constructivists call for the elimination of standardised testing or assessment procedures. For social constructivists, for instance, assessment methods ought to target both the level of actual development and the level of potential development (Dewey, Citation1944; Piaget, Citation1967; Vygotsky, Citation1978). To these theorists, constructivism demands for removing grades and standardised testing. Instead, evaluation is integrated into the learning process to give students a bigger say in determining how well they’re doing. Curriculum evaluation includes Vygotsky’s (Citation1986) social constructivism theory. Assessment techniques must take the Zone of Proximal Development into account from the views of social constructivists (ZPD). Children’s actual development can be measured by what they can do on their own, and their prospective growth can be measured by what they can do with assistance. Even if two children are developmentally at the same level, with the right assistance from an adult, one may be able to solve many more problems than the other. Here, evaluation techniques must take into account both potential and actual development levels.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Research design

Research design, according to Burke and Christensen (Citation2008), is the overarching strategy for gathering data to address research questions. This descriptive study combined the quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Exploratory or inductive research has a high degree of uncertainty and focuses on wider hypotheses rather than specific beliefs (Saunders et al., Citation2012). The research question served as the direction for selecting the sequential explanatory mixed-method design for the investigation:

How knowledgeable are the teacher educators in Social Studies Curriculum material assessment?

When the investigation requires qualitative data to explain quantitative data, the mixed methods sequential explanatory design is ideally suited. The literature has extensively examined both the advantages and disadvantages of this mixed techniques design(Creswell, Citation2003, Citation2005). The philosophical approaches underpinning this study are the ideologies of both the interpretivist and the positivist paradigms.

4.2. Participants and sampling

The study’s intended participants were two hundred fourteen (214) Social Studies instructors from 46 Ghanaian colleges of education. This study has access to all 190 Social Studies teacher educators from Ghana’s original 38 public institutes of education. Each of the 38 initial public colleges of education that were chosen had more than 500 student teachers, therefore teacher educators from these colleges were included in the accessible population. Each of the 38 founding public colleges of education had an average of five teacher educators in the Social Science or Social Studies Department. On this population, a generalization research was carried out. On the other hand, none of the eight recently combined Colleges of Education’s teacher educators were among the demographic that was accessible. This was because they did not match the following criteria for inclusion at the time of data collection: Because of (a) the low student population in the eight recently integrated Colleges of Education and (b) the average number of Social Studies teacher educators in those Colleges of Education being (below 500).

38 Social Studies and History teacher educators from Ghana’s 38 first public colleges of education were selected as a sample for the study. The selection of 38 study participants represented 17.8% of the target population and 20% of the accessible population of Social Studies and History teacher educators, according to the premise that between 1% and 10% of a study population creates a sufficient sampling fraction (Dornyei, Citation2007). Stratified and straightforward random sampling techniques were employed to choose the respondents for the survey, as opposed to a subsample of 8 respondents who were specifically chosen for an interview. The maximum diversity sample, also known as the largest variance sampling technique, was specifically used to select the interviewers.

4.3. Instrumentation

The study saw the data collection in two phases over a stipulated time. The lead researcher gathered the quantitative data using the questionnaires for the first phase. The lead researcher conducted interviews and reviewed documents to gather qualitative data for the second phase. Hence, the qualitative method is subordinate to the quantitative approach in this design.

The 38 respondents’ answers to a questionnaire on a five-point Likert scale were utilised to compile the data. Because Likert-type questionnaires are useful in generating response frequencies suitable to statistical treatment and analysis, the researchers relied on them.

4.4. Data analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 26 was used to test the internal consistency of the questionnaire, and the results produced a Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient () of 0.77. While the interview data were analysed thematically, the survey data were presented using descriptive statistics (frequency count, percentage, and mean). Thematic narratives or actual extracts from the interviews were provided. The Social Studies lesson notes and the History and Social Studies Curriculum and Syllabus for Colleges of Education in Ghana were reviewed (See Figure ).

5. Findings

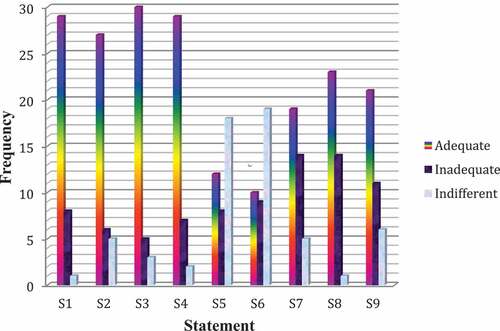

This part of the paper presents quantitative and qualitative data from the questionnaires and interviews addressing the research questions. Table presents the quantitative data from the questionnaire, whiles the second part details the qualitative findings from the interviews. Table present the quantitative data as frequency count and percentages.

Table 1. Displays the socio-demographic data of the participants for the study

Table 2. Knowledge of curriculum material for colleges of education in Ghana by social studies teacher educators

Key:S1—Knowledge and competence in the usage of History curriculum materials

S2—Knowledge and competence in the usage of Sociology curriculum materials

S3—Knowledge and competence in the usage of Civics and Citizenship curriculum materials

S4—Knowledge and competence in the usage of Anthropology curriculum materials

S5—Knowledge and competence in the usage of Geography curriculum materials

S6—Knowledge and competence in the usage of the Economics curriculum materials

S7—Knowledge and competence in the usage of Government curriculum materials.

S8—Knowledge and competence in the usage of integrated Social Studies curriculum materials

S9—I have knowledge and competence in the usage of Social Studies Curriculum or syllabus

With regard to item 1 which sought to find out the knowledge and competence in the usage of History curriculum materials, a total of 29 (76%) teacher educators had adequate knowledge and competence, eight (21%) indicated inadequate, while one (3%) was indifferent.

Concerning item 2 which sought to find out instructor coaches’ knowledge and competence in the usage of Sociology curriculum materials, the finding from the study reveals that 27 (71%) had adequate knowledge and competence, six (16%) mentioned inadequate, whereas five (13%) were irresolute with the statement.

In addition, item 3 sought to elicit teacher educators’ response to their knowledge and competence levels in the usage of Civics and Citizenship curriculum materials. Thirty (79%) teacher educators averred that they had adequate knowledge and competence, five (13%) mentioned inadequate, and three (8%) were indifferent.

In addition, 29 (76%) teacher educators had adequate knowledge and ability in the usage of Anthropology curriculum materials. However, seven (18%) had inadequate knowledge while two (5%) were indifferent.

A few (8) which represents 21% of the teacher educators stated that they had adequate knowledge and competence in the usage of Geography curriculum materials. However, 12 (32%) teacher educators mentioned inadequate knowledge and competence, whereas 18 (47%) were irresolute with the statement.

Item 6 sought to find out the knowledge and competence of teacher educators in the usage of Economics curriculum materials. Nine (24%) instructors educators had adequate knowledge and competence, 10 (26%) mentioned inadequate, and 19 (50%) were indifferent.

The purpose of Item 7 was to ascertain the knowledge and proficiency of teacher educators in the use of government curriculum materials. It develops from the fact that 19 (50%) teacher educators had enough knowledge and ability, 14 (37%) indicated inadequate, and five (13%) were indifferent.

Item 8 elicited teacher educators’ responses to their knowledge and competence levels in the usage of integrated Social Studies Curriculum materials. Twenty-three (61%) teacher educators averred that they had adequate knowledge and competence, 14 (37%) mentioned inadequate, while one (3%) was indifferent.

Item 9 also sought to determine teacher educators’ knowledge and competence in using the Social Studies Curriculum or syllabus. Twenty-one (55%) teacher educators answered in the affirmative that they had adequate knowledge, 11 (29%) mentioned inadequately, and six (16%) were indifferent. Teacher educators’ knowledge and competence in the usage of History, sociology, civics and citizenship, government, and integrated Social Studies Curriculum materials were found to be high or good, with a response rate of 50% or more.

Out of the 38 teachers who were interviewed, 12 were Social Studies teachers, and the other 26 were history teachers. Due to the fact that Social Studies is taught in all 38 of Ghana’s colleges of education, whereas History is only taught in a selected few, Social Studies teachers outnumber their History colleagues. Regarding pedagogy, all 38 of the teachers interviewed emphasised the value of structuring their classes in accordance with the goals outlined in their instructional manual, which was created for Colleges of Education by the various member universities. In essence, packaging lessons based on the objectives of each topic as spelt out in the instructional manuals enables History and Social Studies teachers to help students to assimilate their lessons effectively from both the practical and theoretical points of view. As a Social Studies tutor at Dambai College of Education argued:

I use suitable evaluative tools to assess a lesson’s instructional objectives or goals. These facilitate teaching and learning. I engage in reflective teaching to evaluate the teaching methods I use. This helps me to effectively deliver lessons to students to be able to assimilate them. In a few cases where students failed to assimilate the lessons based on their respective objectives effectively, I had to modify my future methods or approaches as well as modify the objectives of such lessons. Invariably, though the lessons were modified, they mirrored many of the key objectives spelt out in the instructional manual (Interview with a male Social Studies tutor, Dambai College of Education, 14 June 2021).

Teachers do not only pattern their teaching along the objectives, or at least the core objectives of the respective topics of their disciplines; they also use varied methods of teaching. Admittedly, using varied methods of teaching enables History and Social Studies tutors to provide a holistic, effective and all-embracing explanation of the nitty-gritty of the various facets of topics taught. A History Tutor at Saint Mary’s College in Somaya asserted:

… it is impossible to effectively teach History in a classroom-based approach that uses explanations, evidence identification, and question-and-answer teaching to teach History in the Colleges of Education. A tutor needs to use out-of-class mechanisms such as excursions and role play to provide vivid instruction on some technical topics.

(Interview with a male History tutor, Saint Mary’s College, 20 May 2021).

From another perspective, a female Social Studies tutor, who has taught the discipline in the Colleges of Education in Ghana for over a decade underscored the significance of using varied methods of instruction. She opined:

teaching is delicate, irrespective of the discipline. It is even more delicate in Social Studies considering that the discipline is a composite of various social science disciplines, notably History, Economics, Anthropology, Geography, Sociology and Government. Besides, given the nuanced and multi-faceted method of assessment utilised by the affiliate universities that are responsible for conducting end-of-semester exams for their respective colleges, it is imperative that a Social Science Teacher employed different teaching methods. Paramount among the methods of teaching utilised are the questions-and-answers approach, explanatory approach, class discussions, role play, use of facilitators from communities, and excursions, among others.

(Interview with a female Social Science tutor at Accra College of Education, 2 June 2021).

Given that varied teaching methods are utilised, Social Science and History tutors are inclined to use various assessment mechanisms for students. The means of assessment vary depending on the core objective that the tutor seeks to achieve. Generally, the assessment methods included objective tests, essays, short essays or answers, debates, practical demonstrations, and take-home lessons, among others. Underlining the various modes of assessment is the need to build students’ cognitive, affective and psychomotor skills. As one Social Studies tutor explained:

“I assess students in Social Studies in multiple ways. Social Studies assessment covers profile dimensions. I focus on cognitive, affective and psychomotor skills.”

(Interview with a male Social Studies tutor in E.P. College of Education, Bimbilla, 5 July 2021).

In another development, respondents have pointed out that the assessment should emphasise some key skills in almost all the social science disciplines, whether Social Studies, History, Economics or Geography, studied in the Colleges of Education in Ghana. For instance, a 40-year-old male Social Studies tutor noted:

“The assessment of the social sciences – History, Social Studies, Geography and Economics – generally covers the profile dimensions in the cognitive, psychomotor and affective domains.” (Interview with a Social Science tutor at Tamale College of Education, 18 July 2021).

Similarly, a male History tutor at Enchi College of Education also shares the view that the assessments in History seek to build on the cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains of students; hence, the choice of each assessment tool is determined by this objective. In his own words:

“History assessment is very comprehensive because it covers three domains: cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains. I use effective assessment tools and their application.” (Interview with a male History tutor at Enchi College of Education, 27 July 2021).

The frequency of the modes of assessments is not certain since the tutors could not provide details to that effect. However, one thing was certain: tutors use different modes of assessment at different times, and in some cases, tutors have used different assessment tools on the same topic in successive years. Social Studies students would appear to perform better than their History counterparts even when the same assessment tools are applied. As a Social Studies tutor at Akropong College of Education pointed out:

My students sometimes perform well in Social Studies, scoring 100% in internal and external examinations. However, the same students complain they do not do well in History both in the internal and external examinations. I give exercises, quizzes and assignments to students for internal assessment. They pass very well. I enquired with my counterpart teaching History, who explained that the same modes of examination are used in internal assessment and that the differences in the performance of students in examinations in the two disciplines may stem from other factors rather than the mode of examination (Interview with a female Social Studies tutor in Akropong College of Education, 2 August 2021)

There is a preponderate preference for the use of essay-type questions over objective-type and other modes of assessment. Of the 38 respondents, 32 of them (representing 84.2%), prefer to use the essay-type mode of assessment. This preference is accidental; it is largely due to the fairly less cumbersomeness in setting essay questions. Of the 32 respondents that prefer using an essay-type mode of assessment, 24 (representing 75%) use the essay-type mode of assessment because it is relatively easy to set essay questions. As one tutor put it:

“I normally use essay-type questions because it is easy to set. It is quite difficult to set objective-type tests to cover all areas of learning.” (Interview with a male History Tutor in E.P. College of Education, Bimbilla, 5 July 2021)

From the above quotation, it is obvious that the desire of tutors to use the essay-type mode of assessment is not driven by a desire to sharpen students’ English language performance. Studies show that students’ English language performance in Ghana is poor due to a combination of factors (Akowuah et al., Citation2018; Mensah, Citation2014; Wornyo, Citation2016). Hence, the essay-type assessment model would have provided a platform for tutors not only practical insights into students’ English language deficiencies but also the opportunity to assist students in improving in English proficiency. Unfortunately, this was not the case. The personal interest of tutors drove the setting of essay questions. The practical needs of students did not drive it; neither was it dictated by the preference for assessment of the curriculum in Social Studies and History. Only a handful of the tutors (12, i.e., 25%) prefer the essay-type mode of assessment due to the practical need to improve the proficiency of students in the English Language.

It is also important to note that the mode of assessment employed by tutors to assess students in Social Studies and History in the Colleges of Education in Ghana is contingent on the structured nature of assessment procedures. Tutors complain that it is either by default or design. Colleges of Education in Ghana have structured their assessment procedure with about a 60–70% preference for essay-type mode of assessment. All the respondents see this as a determining factor in the choice of the mode of assessment. As a result, tutors are compelled to give more space to essay-type questions in their students’ assessments. As a Social Studies tutor at Akropong College of Education put it:

Sometimes, the structured nature of assessment procedures in Ghanaian Colleges of Education makes it difficult to vary assessment modes (Interview a female Social Studies tutor at Akropong College of Education, 2 August 2021).

Despite this difficulty, 36 out of the 38 respondents (representing 94.74%) always find ways to make space for other questions in assessing students. This is done for two reasons—to meet the needs of students and to prepare the students to write end-of-semester examinations set by the affiliate universities. As a Social Studies tutor at St. Mary’s College of Education in Somanya asserts:

I assess students based on their abilities and needs. In addition, I do so based on the examination templates of the affiliate universities. The affiliate universities have their respective templates of assessment. In St. Mary’s College of Education, for example, in terms of the level 100 and 200 cohorts, the college is affiliated with the University of Ghana; in terms of the level 300 cohorts, the college is affiliated with the University of Education, Winneba. The examination template of the University of Ghana, for example, is made up of three sections – objectives, fill-in, and essays. Hence, for every topic and its sub-sections, I have to develop questions to cover the three sections of the University of Ghana examination template (Interview with a male Social Studies tutor, St. Mary’s College of Education, 20 May 2021).

From the above response, it is obvious that though tutors use a mode of assessment based on students’ abilities and needs, the affiliate universities’ university template plays a critical role.

6. Discussion

The study has examined teacher educators’ knowledge and procedures regarding the evaluation of Ghanaian Social Studies and History curricula. The findings showed that the majority (68%) of teacher educators had enough knowledge of items that were included into the Social Studies Curriculum. However, the expertise and proficiency of teacher educators in the application of the Geography and Economics curriculum materials was very low or inadequate. This highlight the need for taking a holistic view into the content in Geography and Economics and device strategic measures and pedagogies that will demystify the subject matter for teachers to understand and teach.

Another significant finding revealed that tutor educators in Colleges of Education in Ghana possess good reflective practices in terms of knowledge and competence in Social Studies and History curriculum assessment. Teachers employed varied modes of assessment at separate times, and more broadly, tutors utilised diverse assessment tools on a similar topic in consecutive years. It was revealed that Social Studies students based on the assessment performed quite better than their History counterparts when scrutinised with the same assessment tools. This supports the behaviourist approach or theory (Pavlov, Citation1927; Skinner, Citation1957; Thorndike, Citation1911), which states that behaviourism is suggestive of prescriptive assessment procedures as it supports structured, teacher-controlled or centred approaches to assessment procedures. There is a need to look closely at this development and adopt contextual measures to evaluate the situation.

Teacher educators’ efficacy in reflective practices was high in assessing students in integrated Social Studies and History in the classroom, out of the classroom, and in multiple ways. It could be concluded from the result of the study that the assessment of students takes place both in the classroom and out of the classroom (James & Pedder; Harlen, Citation2007). Black and Wiliam (Citation2004) emphasised using assessment to support learning. However, it appears the majority (over 60%) of teacher educators cannot accurately assess all the domains of learning Social Studies and History, particularly the affective domain, in and out of the classroom. The neglect could be partly adduced to the non-availability of validated affective measurement instruments, instructional materials, and aids. This could compromise the quality of Social Studies assessment in Ghanaian Colleges of Education. This revelation is grounded on the Constructivism philosophy of learning (Dewey, Citation1944; Piaget, Citation1967; Vygotsky, Citation1978) which states that learners, by reflecting on their experiences, construct their understanding of the world they live in. This observation affirms the views of Shepard (Citation2000), who states that teachers’ perception of assessment goes a long way to explaining the quality of assessment in Colleges of Education.

Additionally, the findings revealed that most of the teacher educators neglected the teaching and assessment of the affective domain. It is evidenced that Social Studies teacher educators in Colleges of Education in Ghana do not assess the affective domain with any of the techniques; as a result, the affective domain is neglected.

Ultimately, even though most of the instructors educators had a sufficient repertoire of strategies for teaching Social Studies curriculum materials of Colleges of Education in Ghana, it was problematic for most teacher educators to teach Social Studies as an integrated subject via learner-centred methods such as cooperative learning, activity method, role play, field trips, and other learner-centred methods. This was evident in the responses given by the Social Studies teacher educators. This situation calls for the training of teacher educators in subject matter and pedagogical knowledge in integrated pathways. This highlights the social constructivist view, which contends that assessment techniques should focus on both levels of potential and actual growth (Dewey, Citation1944; Piaget, Citation1967; Vygotsky, Citation1978).

7. Conclusions

The study concludes that tutor educators in Colleges of Education in Ghana have low efficacy and poor reflective practices regarding assessment of the affective domain. Teacher educators’ reflective practices and efficacy were low in assessing the affective domain with techniques such as sociometric scales, anecdotal records, portfolio assessments, journals, and checklists. Also, teacher educators’ knowledge and competence in classroom assessment of students were low in integrated Social Studies as against a high level of knowledge and competence in classroom assessment of specific Social Studies subject areas. As a result, it is advised that the National Council on Tertiary Education and the Ministry of Education, in coordination with Ghanaian institutions, scale up the teaching of the procedures for assessing the affective domain. For Social Studies teacher educators, consistent professional development programs on the methods for assessing the affective domain should be organised. The universities in Ghana should train Social Studies teacher educators in the field of measurement and evaluation with particular emphasis on constructing appropriate test items for determining expected affective outcomes. This would help to improve teacher educators’ knowledge of educational measurement and evaluation and provide them the skills they need to evaluate the affective teaching objectives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bernice Oteng

Bernice Oteng is the Head of the Social Science Department, at Accra College of Education, Ghana. She holds PhD in Education (Curriculum and Instructional Studies) from the University of South Africa, Pretoria. Her research interests are Social Studies Education, Social Studies Methodology, Teacher Education, Curriculum and Assessment and Sociology of Education.

Ronald Osei Mensah

Ronald Osei Mensah is an Assistant Lecturer with the Social Development Section, at Takoradi Technical University, Takoradi, Ghana. He holds M.Phil. in Sociology from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. He has cross-cutting research experience in the area of Sociology of Education, Sociology of Law and Criminal Justice, Social Justice, Media Studies and African History.

Pearl Adiza Babah

Pearl Adiza Babah is a Senior Tutor at Accra College of Education, Accra, Ghana, with the Department of Social Science. She has M.Phil. in Social Studies Education from the University of Education, Winneba. Her research interests are in Social Studies Methodology, Sociology of Education and Teacher Supervision.

Enock Swanzy-Impraim

Enock Swanzy-Impraim, is presently a Doctoral Candidate at the School of Education, Edith Cowan University, Perth-Australia. He holds M.Phil. in African Art and Culture from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. Enock does research in Vocational Education, Creativity, Pedagogies, Teacher Education and Comparative Education.

References

- Adu-Gyamfi, S., & Anderson, E. (2021). History education in Ghana: A pragmatic tradition of change and continuity. Historical Encounters, 8(2), 18–22. https://doi.org/10.52289/hej8.201

- Akowuah, J. A., Patnaik, S., & Kyei, E. (2018). Evidence-based learning of student’s performance in English language in adu gyamfi senior high school in the Sekyere South District of Ghana. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1–10. Retrieved on October 15, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1503577

- Allen, J. M., Howells, K., & Radford, R. (2013). A partnership in teaching excellence: Ways in which one school-university partnership has fostered teacher development. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 41(1), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2012.753988

- Anamuah–Mensah, J. (2006). Teacher education and practice in Ghana. In K. T. Raheem & K. Pekka (Eds.), Educational issues for sustainable development in Africa (pp. 28–40). Institute for Educational Research.

- Azizi, A. (2010). Pentaksiranpendidikan. Dewan Bahasa danPustaka.

- Barley, S. Y. M. (2013). Perspectives of school-based assessment in the NSS curriculum through the eyes of the administrative and teaching stakeholders in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Teachers’ Centre Journal, 12, 1–28.

- Bekoe, S. O., Eshun, I., & Bordoh, A. (2013). Formative assessment techniques teacher educators use to assess teacher trainees’ learning in social studies in colleges of education in Ghana. Journal of Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(4), 20–30.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998a). Assessment and classroom learning assessment in education. Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2004). The formative purpose: Assessment must first promote learning. Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, 103(2), 20–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7984.2004.tb00047.x

- Brink, M. K. (2017). Teachers’ perceived understanding of formative assessment and how this understanding impacts their own classroom instruction [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

- Burke, R. J., & Christensen, L. B. (2008). Education research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches (3rd) ed. Sage Publications.

- Chappuis, S., Chappuis, J., & Stiggins, R. (2009). Supporting teacher learning teams. Educational Leadership, 66(5), 56–60.

- Clark, I. (2012). Formative assessment and motivation: Theories and themes. Prime Research on Education (PRE), 1(2), 27–36.

- Crawford, J. (2002). Accountability versus science in the bilingual education debate. Language Policy Research Unit (LPRU) and the Education Policy Studies Laboratory (EPSL) at the Arizona State University. http://www.asu.edu/educ/epsl/LPRU/

- Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design (2nd) ed. Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. New Jersey: Pearson Education.

- Dewey, J. (1944). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. NY: The Free Press.

- Dornyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford University.

- Finlay, L. (2008). Reflecting on reflective practice. Practice-based professional learning paper 52, The Open University. June 5, 2021 from www.open.ac.uk/pbpl

- Fook, C. Y., & Sidhu, G. K. (2010). Authentic assessment and pedagogical strategies in higher education. Journal of Social Sciences, 6(2), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.3844/jssp.2010.153.161

- Gronlund, N. E. (2006). Assessment of student achievement (8th) ed. Boston.

- Harlen, W. (2007). Primary review research survey 3/4. In The quality of learning: Assessment alternatives for primary education (pp. 1–42). University of Cambridge Faculty of Education.

- Hassan, A., Pheng, K. F., & Yew, S. K. (2013). Philosophical perspectives on emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and job satisfaction among secondary school teachers. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3(19), 1–6.

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

- Hattori, K., & Saba, A. N. (2008). Comparison of classroom assessment practices: A case of selected Ghanaian and Japanese mathematics lessons. Journal of International Educational Cooperation, 3, 95–105.

- Hayward, L. (2015). Assessment is learning: The preposition vanishes. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(1), 27–43.

- James, M., & Pedder, D. (2006). Beyond method: Assessment and learning practices and values. The Curriculum Journal, 17(2), 109–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585170600792712

- Kellaghan, T., & Greaney, V. (2001). Using assessment to improve the quality of education. UNESCO: International institute for educational planning.

- Kitta, S. (2014). Science teachers’ perceptions of classroom assessment in Tanzania: An exploratory study. International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education, 1(12), 51–55.

- Liu, J., Johnson, R., & Fan, X. (2016). A comparative study of Chinese and United States pre-service teachers’ perceptions about ethical issues in classroom assessment. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 48, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.01.002

- Lunenberg, M., Dengerink, J., & Korthagen, F. (2014). The professional teacher educator: Roles, behaviour, and professional development of teacher educators. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Mensah, J. (2014). Errors in the written essays of senior high school students: A case.

- Ministry of Education. (2020a). National pre-tertiary learning assessment framework (NPLAF).

- Ministry of Education. (2020b). School-based assessment guidelines.

- Ministry of Education, Ghana. 2004. White paper on the report of the education reform review committee.Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports.

- Mumm, K., Karm, M., & Remmik, M. (2016). Assessment for learning: Why assessment does not always support student teachers’ learning. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 40(6), 780–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2015.1062847

- Nabie, M. N., Akayuure, P., & Sofo, S. (2013). Ghanaian prospective mathematics teachers’ perceived self-efficacy towards web pedagogical content knowledge. International Journal of Liberal Arts and Social Science, 1(3), 1–9.

- NaCCA. (2020). National pre-tertiary learning assessment framework.

- Pavlov, I. (1927). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Dover.

- Piaget, J. (1967). The mental development of the child. Six Psychological Studies, 3, 70–73.

- Rahman, M. S. (2016). The advantages and disadvantages of using qualitative and quantitative approaches and methods in language testing and assessment research: A literature review. Journal of Education and Learning, 6(1), 102–112. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v6n1p102

- Salmiah, J. (2013). Acceptance towards school based assessment among agricultural integrated living skills teachers: Challenges in implementing a holistic assessment. Journal of Technical Education and Training (JTET), 5(1), 1–8.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2012). Research Methods for Business Students (6th ed.). PearsonLtd., Harlow.

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29(7), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X029007004

- Skinner, B. (1957). Verbal behaviour. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Suhaimi, A., Abdullah, A., Hamzah, M., Adnan, S., & Noh, M. (2013). High school English teachers’ and students’ perceptions, attitudes and actual practices of continuous assessment. Academic Journals, 8(16), 1489–1498.

- Suurtamm, C., Koch, M., & Arden, A. (2010). Teachers’ assessment practices in mathematics: Classrooms in the context of reform. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy, and Practice, 17(4), 399–417.

- Thorndike, E. (1911). Animal intelligence: Experimental studies. Macmillan.

- Tierney, R. D. (2013). Fairness as a multifaceted quality in classroom assessment. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 43, 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.12.003

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in the society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wiliam, D., & Thompson, M. (2008). Integrating assessment with learning: What will it take to make it work? In C. A. Dwyer (Ed.), The future of assessment: Shaping teaching and learning (pp (pp. 53–82). Erlbaum.

- Wornyo, A. A. (2016). Attending to the grammatical errors of students using constructive teaching and learning activities. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(7), 23–32. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1095256.pdf

- Zhang, Z., & Burry-Stock, J. A. (2003). Classroom assessment practices and teachers’self-perceived assessment skills. Applied Measurement in Education, 16(4), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324818AME1604_4

APPENDIX A

QUESTIONNAIRE FOR SOCIAL STUDIES TEACHER EDUCATORS OF COLLEGES OF EDUCATION IN GHANA

SECTION A: SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC DATA

Sex/Gender: Male [] Female [] Institution []

Age range (in yrs): 18—24 [] 25–34 [] 35–44 [] 45–54 [] 55–60 []

Highest level of education:

B.Ed/B.A./BSc in Social Studies [] M.Ed/M.A./MSc in Social Studies []

B.Ed/B.A./BSc in Social Science [] M.Ed/M.A./MSc in Social Science []

B.Ed/B.A./BSc in Political Science [] M.Ed/M.A./MSc in Political Science []

B.Ed/B.A./BSc. in Sociology [] M.Ed/M.A./MSc in Sociology []

B.Ed/B.A./BSc. in Economics [] M.Ed/M.A./MSc. in Economics []

B.Ed/B.A./BSc. History [] M.Ed/M.A./MSc. History[]

B.Ed/B.A./BSc. Sociology [] M.Ed/M.A./MSc. Sociology[]

B.Ed/B.A./BSc. Geography [] M.Ed/M.A./MSc. in Geography[]

PhD. in Social Studies [] M.Phil Social Studies []

PhD. in Social Economics [] PhD. in History []

PhD. in Geography [] PhD. in Sociology []

Other [], specify (PGDE, PGCE): … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …

(4) Have you studied Social Studies/Social sciences as a major course in the university? Yes [] No []

(5) What Social science subject (s) are you trained to teach? Tick (∏)all subjects you could

History[] Geography [] Civics [] Economics [] Sociology []

Anthropology [] other [], specify: … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …

(6) Number of years of teaching Social Studies: 1-3yrs [] 4-6yrs [] 7-10yrs [] 11-15yrs [] 16-20

SECTION B: TEACHERS’ KNOWLEDGE OF SOCIAL STUDIES

CURRICULUM MATERIAL

Instruction: Please, provide responses to the items that follow by ticking (∏) or writing the response that best suits your opinion. Use the Likert-scale below to answer questions 7 - 11:

Key: 5 = Strongly Agree; 4= Agree; 3 = Indifferent; 2= Disagree; 1= Strongly Disagree

Instruction: Use the following scale to answer questions 12 - 19:

Key: 5 = Very adequate/good; 4= Competent; 3 = Adequate; 2 = Not adequate; 1 = Undecided

How do you perceive your knowledge level in each knowledge base required for the teaching of Social Studies subjects?

SECTION C: TEACHERS’ PEDAGOGY OF TEACHING SOCIAL STUDIES

CURRICULUM MATERIAL

Instruction: Use the following scale to answer questions 36 - 48:

Key: 5 = Very high extent; 4 = High extent; 3 = Moderate extent; 2 = little extent;

1 = No extent

APPENDIX B:

SEMI-STRUCTURED INTERVIEW GUIDE FOR SOCIAL STUDIES TEACHER EDUCATORS IN COLLEGES OF EDUCATION, GHANA

1. How would evaluate or assess your knowledge of the Social Studies Curriculum of Colleges of Education in Ghana?

2. How would you evaluate your own level of knowledge of Social Studies Curriculum?

3. How would you evaluate your own level of knowledge in Social Studies?

4. Do you have sufficient knowledge of Social Studies as an integrated subject or individual subject areas?

5. What do you consider as your strength(s) and weakness (es) in the knowledge of teaching Social Studies?

6. As a Social Studies teacher educator, what is your level of mastery and competencies in the teaching of Social Studies in college of education?

7. How do you assess your pedagogy of teaching Social Studies?

8. As a Social Studies teacher educator, what do you think are the key things that make a good classroom teacher?

9. How would you evaluate teaching methods which you use during Social Studies lessons?

10. What do you consider as your strength(s) and weakness (es) in the pedagogy of teaching Social Studies?

11. What do you consider as your strength(s) and weakness (es) in the assessment of Social Studies?

12. How can you evaluate your pedagogical knowledge of engaging students in exploring real world issues and solving authentic Social Studies problems using technology, media, and other resources?

13. How would you evaluate your pedagogical knowledge of addressing the diverse needs of all learners by using learner centred strategies?

14. How would you evaluate your pedagogical content knowledge and the ability to understand and integrate teaching approaches that arouse students’ creativity?

15. How would you evaluate your pedagogical content knowledge and ability to apply teaching approaches which give more authority to students in solving Social Studies problem?

16. How would you evaluate your knowledge, competency and mastery of curriculum assessment in Social Studies?

17. How would you evaluate the quality of Social Studies instruction in your college?

18. How would you assess the quality of Social Studies instruction (teaching and learning) in your college?