Abstract

Informal learning space (ILS) has increasingly become important for higher education. Yet, most studies were conducted on a piecemeal basis, without considering the planning of the campus. This study adopts a systematic and data-driven approach in understanding the types of ILS, preferences and behaviors using a case study in Hong Kong, by first classifying ILS into user-defined types followed by usage behavior for each ILS types. A mixed-method approach was used by conducting qualitative interviews, focus groups, on-site fieldwork observations and large-scale quantitative survey (N = 999) with students. Five types of ILS with unique characteristics were identified. This applied research seeks to suggest development directions and design input for ILS types, with implications for master planning in ILS development, extending to any universities using the same procedure.

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, there has been a shift in pedagogy for higher education. Radloff (Citation1998) found that only 20 percent of students’ time is spent in classroom learning. This indicates more preparation and group work outside classrooms. Since students’ learning is no longer confined to formal learning spaces, there is a need to plann and build informal learning space (ILS) to meet students’ needs.

ILS is defined as “non-discipline specific spaces frequented by staff and students for self-directed learning activities within and outside library spaces” (Harrop & Turpin, Citation2013, p. 59). In addition to providing physical space for self-study and group discussions, ILS also supports socializing and discussion for students, which constitutes a venue for social construction in knowledge development. It is believed that the longer students stay on campus, the more students can learn from any form of informal learning (Matthews et al., Citation2011). Consequently, ILS has become increasingly important in the university atmosphere and overall students’ experience.

Despite this, there have been limited efforts in understanding ILS. Some ILS may be managed by specific departments, while others are managed by the university; both parties do not necessarily have jurisdiction over each another. As ILSs are being developed on a piecemeal basis, research studies are conducted on specific ILS instead of on a university-wide basis, with learnings unable to provide a planning perspective.

A recent study outlined the importance of having an institution estate strategy for universities to understand the perspective of users, to shift the role, allowing user perspective in leading the development efforts (Waldock et al., Citation2017). As such, a holistic understanding of students’ demand preferences and usage would be beneficial to overall planning.

Similar to course timetabling, there needs to be prudent planning to anticipate student needs, traffic flow, and usage needs. A systematic and comprehensive review of ILS usage within the university is a starting point, with pertinent measurement information, including incidence, frequency, and duration of usage. User satisfaction helps gauge whether current ILS offerings meet user expectations. Dissatisfaction can result in sacrificing certain activities due to less desirable venues, or even leaving the university environment, resulting in reduced informal learning opportunities.

This research paper focuses on three main objectives: (1) to apply a mixed method approach in classifying a range of ILSs into ILS types using a qualitative approach and concept mapping; (2) to examine students’ current usage patterns and feedback of different ILS types within a specific university using a case study approach, and (3) to provide input to capacity planning. A case study was conducted in a university in Hong Kong. Results of this applied research will provide fact-based recommendations and bridge the knowledge gap in ILS planning and development.

2. Literature review

2.1. ILS knowledge gap in higher education

The awareness and needs of ILS have been propagated by a shift in pedagogies, from conventional lectures to active learning, which typically requires students to meet and spend more time outside classroom (Morieson et al., Citation2018). ILS, as a result, has become an inseparable component for higher education. The current focus aims at achieving deep learning, whereby students actively participate inside and outside the classroom, to apply knowledge and solve problems. This signifies ILS’s increasing importance and the need to build more ILS for student use in an effective manner (Beckers et al., Citation2016).

Most ILS research studied students’ behaviors, preferences or engagement (Waldock et al., Citation2017) based on one or a few ILS sites. While Ibrahim et al. (Citation2018) explored ILS in a broader scope, i.e., four different types of ILS, including “Breakout space” (a fully enclosed room), “Library”, “Cafeteria”, and “Outdoor learning space”, they did not examine the overall needs of students. The research suggested private, or group learning was more common in study rooms and interactive learning engagements were found in outdoor ILS.

Previous research has mostly been conducted on a piecemeal basis, rather than evaluating the ILS from a university-level perspective. This can result in sprawling, fragmented and isolated environment at universities, leading to the lack of concerted planning (Coulson et al., Citation2015).

Given the above limitations, there is a knowledge gap to be filled. The current study draws upon the concept of capacity planning. Capacity planning is the process of determining production capacity needed by an organization to meet changing demands for its products (Cochran & Uribe, Citation2005). For example, in an organization that anticipates growing demand for its goods and services, it will plan to improve effective capacity to meet the demand, by providing sufficient equipment to produce the right kind of products.

In the context of ILS, when capacity is below demand, students may choose sub-optimal venues, or leave the university and meet elsewhere. It is important for universities to understand the demands and needs of students in ILS for planning purposes. There is limited empirical understanding (Harrop & Turpin, Citation2013), and previous studies lack a standardized definition for ILS types for further examination, which is a limitation in ILS behavior measurement.

2.2. Integrating ILS in master planning

A master plan is defined as a vision document providing a planning timeframe, outlining the planning and development potential and improvements in future growth (Meshram, Citation2006), with long-term planning of what volume, how much space and what buildings are being added to or reduced from a university. This is done in conjunction with the forecast of student body, programs and faculties (Coulson et al., Citation2015). The main goal is to determine the appropriate amount of space for different purposes and maximize the use (Abramson & Burnap, Citation2006).

The consequences of having a master plan are to present the institutional goals explicitly, enhance student experiences, promote a welcoming campus for learning, and attract more potential students (Bady & Konczal, Citation2012). The planning process also helps the university to understand the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and constraints for future development (Halla, Citation2007).

Previous research has considered space planning or campus master planning in higher education in the UK (Temple, Citation2008). Yet, the common practice is largely limited to formal learning spaces only, and ILS planning is a gap to be filled. Until we have a university-wide assessment of ILS usage and preferences, we would not be able to plan for ILS development holistically.

2.3. The constraints of ILS development

Theory of Constraints (TOC) describes that any manageable system is limited in achieving more of its goals by a small number of constraints (Goldratt, Citation1988). TOC suggests a focusing process to identify and exploit the constraints in the system. The TOC further explains that existence of constraints should not be treated as threats, but opportunities for enhancement (Rahman, Citation1998). Hence, the TOC recommends that improvement should be made on the constraints and once the performance improves, the resources can be realized, improving the whole system (Goldratt, Citation1990).

Applying TOC to ILS, there are two constraints. Firstly, limited spaces and land resources comprise one constraint. Reviewing over 100 master plans from U.S. universities, Hajrasouliha (Citation2017) found a higher chance of infill development over campus expansion, reflecting the deficit in land area on campus, which becomes a major obstacle to overcome. Limited land resources also lead to limited number of ILS. Students, therefore, may have limited ILS options and may leave the campus altogether, particularly if the campus is located in urban areas (Cunningham & Walton, Citation2016). These may prevent universities from optimizing ILS usage and meeting students’ demand. TOC notes if the constraint is physical, the goal is to make the object of constraint as effective as possible (Rahman, Citation1998). This elucidates the importance for universities in understanding how students utilize the current spaces for better planning.

Secondly, current ILS may not fully live up to students’ expectation, as in many cases, the existing ILSs are built based on management’s perspective (Temple, Citation2008), and the design of ILS may not fit students’ needs (Cox, Citation2018). Therefore, students may not study and have group discussion due to the unsuitable or uncomfortable facilities (Matthews et al., Citation2009), and may dislike the current settings, such as noise or overcrowding (Cha & Kim, Citation2015). Since the current options may not be preferable, students may not use the ILS, with the possibility of returning home for self-study (Cox, Citation2018). Once students leave the campus, it minimizes their opportunities to socialize, work and collaborate with peers, which are important activities contributing to the overall university experience (Ibrahim & Fadzil, Citation2013). Hence, an understanding of ILS preference and usage, and building relevant capacity; will provide the stickiness for students to stay on campus for informal learning and enhance their overall experience.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research context

A university in Hong Kong was examined in this study. The university is located in one of the busiest business districts, and is one of the most popular tourist destination in Hong Kong. The geographical location of the sample university implies limited building sites for expansion due to scarce land resources. The sample university not only is dedicated to the provision of high-quality education, but also strives to enhance students’ experience. Our research team contacted departments within the university to gather information about ILS and conduct a preliminary field study before commencing the study. There are 39 ILS sites at the sample university, including the library. Empty classrooms or lecture theatres are not considered ILS in our study as these facilities are designed for formal learning. Facilities that do not involve in formal learning, such as study spaces within academic buildings, outdoor dining areas and library, are included in the list. The portfolio of 39 ILS sites and the unique location of the university makes a suitable case to study.

3.2. Research design

A mixed-method approach was used, with Phase 1 qualitative research followed by a Phase 2 quantitative survey.

3.2.1. Phase 1 qualitative research

Interviews and focus groups were conducted. Undergraduate students were recruited through university mass email system under the banner invitation of the University’s Working Group on Innovative Learning Spaces. Respondents were selected based on several demographic characteristics, including the current program of study, and year of study and residency (i.e., residence versus commuters).

Ten in-depth interviews were completed, with an average duration of 30.1 minutes. Four focus group interviews were also conducted with six to eight students per session, and an average time of 63.6 minutes. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed for content analysis. In addition, on-site fieldwork observations were conducted from October 18 to 23, 2018. Our research team visited 39 ILS sites to gain a deeper insight on students’ behaviors, traffic, and facilities near the ILS, with notes taken as additional sources of data.

The primary purpose of student focus groups is to develop a user-generated definition, collectively, of ILS types by mapping and sorting ILS sites into meaningful categories (i.e., types) through interactive discussions. This exercise is grounded in the theories of classification (Niknazar & Bourgault, Citation2017). Each classification represents a rationale and is domain-specific; in turn, each domain could develop unique rules on how objects shall be grouped. Supported by activation theory and network model of memory, concept-mapping (CM) technique has been adopted in marketing, education, and counselling research (Joiner, Citation1998) as CM is designed to elicit respondents’ cognitive process to classify ILS into different types, creating domain-specific classification, allowing respondents to draw simple associations among the various objects (Davies, Citation2011).

Furthermore, in-depth interviews were conducted to gain greater details on individual student’s perception and explain their classification’s value. Individuals are free to express the concepts and categories that are formed in their mind during the cognitive process of classification (Niknazar & Bourgault, Citation2017). On top of that, students were invited to tell their preferences, usage occasions and unmet needs for different ILS types. The detailed treatment for the qualitative approach based on concept mapping and idea generation sorting methodology; followed by quantitative validation in 7 ILS sites, were reported in Chin et al. (Citation2021).

Combining the information from all sources not only assists in drafting the questions and attributes for the questionnaire in the second phase, but also helps us to understand students’ feedback on the ILS types.

3.2.2. Phase 2 quantitative survey

To properly measure the extent of usage and preferences of ILS, an attitude and usage study was conducted via a large-scale quantitative survey. Again, undergraduate students were invited to participate through the university mass email system. Seven-point Likert-type scale questions were used. Students were asked to express their usage pattern, preferences and needs for each ILS type generated from the qualitative data.

3.2.3. Data analysis process

The qualitative data was firstly analysed by the research team through a content analysis by using NVivo. Focus group data was analysed using a concept-mapping (CM) process with the photo sorting technique (Chin et al., Citation2021). Then, findings from in-depth interviews and focus group discussions generated survey questions on the types of ILS, as well as potential usage pattern and preferences for the quantitative stage questionnaire.

For the quantitative survey, to improve face validity, the questionnaire was reviewed by a panel of three qualified academics, and pilot-tested with 30 students before fielding the survey online using the university mass email system. A total of 999 usable responses was collected from November 21 to 26, 2018. SPSS (version 25) was used for data analysis.

4. Findings

4.1. Phase 1 qualitative research—five ILS types

Using a data-driven approach and based on a concept-mapping (CM) process using photo sorting technique, our research team grouped the 39 ILS sites into five distinct types (Table and Figures ). The detailed process was described in Chin et al. (Citation2021). The five ILS types form the bases for quantitative evaluation in the second phase. Phase 1 research findings are reported as follows:

Figure 1. An example of Indoor (quiet) ILS.

Figure 2. An example of Indoor (talking allowed) ILS.

Figure 3. An example of Outdoor ILS.

Figure 4. An example of Indoor (sofa) ILS.

Figure 5. Comprehensive ILS (Library).

Table 1. ILS types distribution

4.1.1. Indoor (quiet) ILS

Students highlight that Indoor (quiet) ILS could be enhanced by partitioning which provides an enclosed area for privacy, helping one to become more focused. This also blocks sound and provides a physical barrier from other people. Electric outlet for charging devices is expected. Quiet ILS tends to cater to single, two or a small group of people, depending on the physical setup:

There is more focus here. You can study with friends but not talking. Interviewee 4.

There are not that many of these ILS so less people can study here. Interviewee 10.

4.1.2. Indoor (talking allowed) ILS

Respondents find that Indoor (talking allowed) ILS with tables and chairs are conducive for discussions. As these spaces can be part of a common area or alongside a corridor, an acceptable noise level is expected. On-site observations found that these spaces are mostly used during class-changing period, and students may not be willing to stay there for a long time as there are less facilities, such as vending machine or drinking fountain.

The place is convenient for group discussions or preparation for presentations. The location is good and we can also shoot video. Interviewee 4.

Because the place is part of a corridor, there is traffic and people talking … I do not believe the place is suitable for work, but better for discussion. Interviewee 9.

4.1.3. Outdoor ILS

Outdoor ILSs are unique because they give a sense of openness. For areas that are close to takeout food outlets, naturally, students would use the space for dining:

This place is good for waiting and chit chatting with friends, as no one will bother you. You can also eat something here as it is close to eateries but there is no shelter. Focus Group 1.

Given they are not weather protected, this encourages transient usage. Sceneries and green are refreshing, alongside with natural lighting and the possibility of fresh air. Field observations found that students would gather there before and after classes, but seldomly stay for long since it may be uncomfortable to sit there. Yet, there are issues of sun, rain, temperature and lack of support such as charging, toilet and water. As well, there is a lack of amenities compared with indoors:

It is too hot for the summer. There are no power outlets and you cannot charge your devices. Interviewee 4.

4.1.4. Indoor (sofa) ILS

Interviewees notice when sofa is the main furniture for the ILS, it becomes a category of its own. Sofa has a connotation of being comfortable for lazing around, and not for serious work. When positioned without a table and when the height is usually lower, sofa connotes a relaxing atmosphere:

I usually sit here when I don’t have anything to do. I just want to stick to my phone on social networks … Focus Group 3.

There are a lot of sofa chairs but no table, so it is not convenient for studying. Interviewee 10.

On-site fieldwork found that these ILS are comfortable for student to use but the usage is relatively low as most of these ILS sites are located in isolated zones on campus.

4.1.5. Comprehensive (library)

The last category is recognized as a comprehensive ILS, i.e., the Library, in the sample university. The Library is recognized as an important venue for informal learning outside classrooms (Cunningham & Walton, Citation2016), and therefore included a priori in this study. Over the last few years, the Library has made efforts in changing from storage of hardcopy articles and books, to providing services including venues for group meeting, self-study and virtual conferencing.

There are many seats, quite convenient and the environment is comfortable. There are hot water and printer access. Focus Group 1

The Library has been transformed into an interactive learning space, attracting over 2.9 million visitors each year (Library Staff, personal communication, 2018), and has equipped the facilities that could be found in other ILS. However, it is the only ILS type that could fulfil students’ multiple needs at once, for example, meeting in the co-working space and then go for self-study in a quiet room. Yet, there are limitations:

A disadvantage in the library is that you are not allowed to eat. Also, the temperature is often too cold. Focus Group 4

Fieldwork also noted that some students would use the Library for non-academic activities, such as sleeping or playing computer games, revealing a diverse but unintended behaviours for this type of ILS. Despite these disadvantages, this comprehensive-type of ILS would be ideal for students to conduct various of activities.

4.2. Phase 2 quantitative survey—respondent profile

Of the 999 respondents, Year 1 students (Freshmen) represent the largest share in this sample (30.33%), while Year 2 students (Sophomores) account for the least share (22.22%). Year 3 (Junior) and Year 4 (Senior) students account for 23.42% and 24.02%, respectively. The study sample has a good representation of all majors from the six colleges and two schools at the university. The majority of respondents (95.9%) studied full time.

4.3. Penetration of the ILS types

Almost all (93.8%) students visited the comprehensive ILS (the library), reflecting its importance and popularity as a learning space. About half of the respondents visited Indoor (quiet) ILS (51.0%), Indoor (talking allowed) ILS (49.9%) and Outdoor ILS (55.4%). The penetration seems high for Indoor (quiet) which constitutes only 5.1% of the ILS sites on campus (Table ). Similarly, Indoor (talking allowed) constitutes about 23% of all ILSs and have a penetration of close to 50%. Lastly, 35.9% of respondents visited Indoor (sofa) but they constitute only about 18% of total ILS, possibly explained by the low availability or inconvenient locations. Other than the comprehensive-type ILS, the relatively low penetration of the ILS reveals that there may be limited promotion of ILS, as reflected in comments that ILSs are difficult to find because students do not know the locations and they are not listed on the campus map.

4.4. Main purpose and usage pattern for each type of ILS

4.4.1. Comprehensive (Library)

The comprehensive-type ILS, i.e., the library, has been considered a venue for academic activities. The top 3 reasons for going to the comprehensive ILS are self-study (39.5%), group discussion for academic purpose (16.3%) and study with friends (12.4%). The prominent purpose of group discussion reflects the changing role of the library. The enhanced facilities, such as computers and comfortable seats provide flexible usage occasions, including waiting for class and for friends. Highest frequency of usage is observed for comprehensive-typed ILS (Table ), as 75.7% of students visit there at least once a week, with 78.7% of students visited there in the past 7 days. As well, 57.1% the students spend an hour or more at the comprehensive-type ILS, also the highest among all ILS types. Yet, student interviews find it is always crowded as some students occupy the spaces for sleeping and relaxing for a long time, limiting other students to study there.

Table 2. Visiting pattern for different types of ILS

4.4.2. Indoor (quiet) ILS

Over half of the students indicate self-study (52.1%), followed by waiting for class (13.0%) and study with friends (11.1%), as the purposes of visit in Indoor (quiet) ILS. The quiet nature of this type of ILS also attracts students to wait for class (13.0%) or simply take a rest there (5.5%). Student interviews reveal that the quiet nature helps them stay focus. Therefore, despite there are only 2 indoor (quiet) ILS on campus, they have a high usage frequency with 41.2% of respondents visited more than once a week (Table ). In addition, over 40% of students visited in the past 7 days. Nearly half of the respondents stayed over an hour, possibly due to activities such as studying and discussion.

4.4.3. Indoor (talking allowed) ILS

Expectedly, Indoor (talking allowed) ILS is used mostly for group project and discussions (20.4%), they are also used for studying with friends (14.0%) or self-study (11.6%). Certain level of noise is expected. Most students use the ILS for waiting for class (25.9%) and some for resting (6.6%). Student interviews report the ILS design stimulates their creativity, and they are also ideal for taking a rest before or after class due to proximity to classrooms. Consistent with Indoor (quiet) ILS, nearly 40% of students visit more than once a week and in the past 7 days (Table ). Different from the Library and Indoor (quiet) ILS, Indoor (talking allowed) ILS not only attracts self-study but also invites discussion activities. Therefore, the time spent varies, with nearly 40% of students spent up to 30 minutes and close to 35% of students spending an hour or more, showing usage from both short discussions and long hours of self-study.

4.4.4. Outdoor ILS

Students report that Outdoor ILSs are for short gatherings. Dining is the most popular purpose, whether it is dining alone (20.6%) or dining with friends (18.8%). Outdoor ILS seems to be an ideal place for students to spend time for waiting for class (20.2%) or friends (9.7%) or socializing with them (10.1%). Students express that Outdoor ILS provides a relaxing atmosphere for them to dine and to chill out. However, they tend to visit less frequently compared with indoor ILS, with only 37.2% of respondents went there at least once a week (Table ). Yet, 47.1% of respondents visited in the past 7 days. Student interviews disclose poor hygiene, unstable weather and uncomfortable seating arrangement drive students away, and it is less used than most indoor ILS. The time spent there is relatively shorter, with over half of the respondents stay up to 30 minutes, while 90% of the users leave within an hour. The time spent reflects the relatively transient use occasions, such as dining and waiting.

4.4.5. Indoor (sofa) ILS

Sofa is a unique ILS option for students to relax, rather than for studying or doing assignments. Student interviews reported that given there are no tables, they will not study there. The result echoes the qualitative findings as 37.6% of students take a rest at sofa ILS. Sofa also serves as a transient place between classes and activities since students use Sofa ILS to wait for friends (20.1%) and wait for classes (18.3%). Sofa also serves as a venue for socializing (5.8%) and spending time alone (4.5%). Not used for academic purpose, students tend to visit sofa ILS less frequently; only 19.2% of respondents visited sofa ILS at least once a week, and over half of the respondents visited sofa ILS less than once per month (Table ), which is the least visited among all ILS types. Besides, only 27.9% of respondents report they visit the sofa area in past 7 days, again, the lowest among five ILS types. Lastly, given one would not study there, they tend to take a short break and relax; 70% of respondents stay in this kind of ILS for a short period of time of up to 30 minutes, denoting the short break nature in its usage.

4.5. Preference share for ILS types

To understand preferences for different ILS types, a constant sum scale chip-game was used in the quantitative survey, which asked respondents to distribute a total of 100 visits to the five ILS types. Results show that students would allocate close to half (46.7%) of the visits to the comprehensive-typed. The popularity of a comprehensive-typed (i.e. Library) ILS reflects it as the top choice for students to conduct learning-related activities outside classroom. Besides, it also provides computers, printers, group discussion rooms and individual studying space, attracting students’ visits.

Other indoor ILS types are the second choices of students since they can also provide a learning atmosphere. Students slightly prefer Indoor (talking allowed) ILS (18.2% of visits) over Indoor (quiet) ILS (15.7% of visits). This may be due to the versatile nature of Indoor (talking allowed) ILS, permitting both self-study and intense group discussion. On the other hand, Indoor (quiet) ILS could be more restrictive as it discourages talking. However, both Indoor (quiet) and Indoor (talking allowed) constitute more than 1.5 times the visits allocated to Outdoor ILS (10.5%). This is consistent with the findings reported earlier, reflecting concerns of discomfort and hygiene at outdoor ILS. Sofa ILS has the lowest share, at 8.8% of visits.

4.6. ILS user satisfaction

A mean of 4.96 on a 7-point scale was received for overall satisfaction in using ILS at PolyU, indicating that students were moderately satisfied with the provision of ILS now of data collection, with rooms for improvement. Open-ended comments reveal that some students appreciate the variety of ILS and their comfortable atmosphere motivates students to study more. However, it is not easy to find a seat due to under-capacity, especially during exam period. Besides, students expressed that the facilities, such as tables, chairs and charging stations, are insufficient and some are broken. Nevertheless, the score provides a baseline for tracking changes when subsequent improvements are made.

In a similar fashion, an average score of 4.80 for ILS maintenance reflects a satisfactory score but with rooms for improvement. Open-ended comments show that some students thought the ILS sites are poorly managed because some are dirty and poorly maintained. Anecdotal comments indicate that outdoor ILSs are dusty, computer desks are oily, and the toilets have unpleasant odours. Students are also unsure of proper feedback channels to voice their suggestions. However, the top-3-box scores (those who selected 5, 6 or 7 on the 7-point scale) show that the majority of respondents are positive on their satisfaction and ILS maintenance (Table ).

Table 3. Overall satisfaction and maintenance of ILS

Pearson correlation was used measure the relationship between the overall satisfaction and ILS maintenance. A moderately high and positive correlation was observed at r = 0.59 (p < .001), reflecting regular maintenance is related to user satisfaction.

4.7. ILS future development

Students were asked to indicate the top 5 most important spaces to add on campus. Close to half (44.2%) of the students express the need for more individual study spaces. This overwhelmingly exceeds the need for group-related space: 15.2% for group discussion, 14.2% for group study, and 9.0% for group project with technical support. Besides, space for resting (8.4%) and socializing with access to food and drink (7.3%) are also demanded by students. On the subject of development strategy, students prefer decentralized location (61.0%) for ILS instead of centralized location (39.0%), reflecting the need for ILS to be more conveniently located and be planned in a distributed manner.

5. Discussion

5.1. An overview on usage pattern and student feedback of ILS

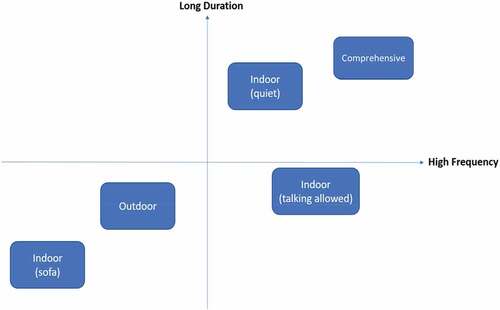

This paper represents one of the first effort in comparing all ILS types within one campus, providing empirical support to the ILS literature and highlighting the importance of master planning in designing ILS on campus (Meshram, Citation2006). The usage pattern and feedback of different ILS types within the sample university are summarized in Table and Figure .

Figure 6. Positioning map of the Five ILS type.

Table 4. Overall usage patterns by ILS types

The usage patterns reflect a thorough use of facilities as a results of the university’s master planning of ILS. Significant usage was observed in the comprehensive type, evidenced by the frequency of visit, time of last visit and visit duration. Besides the tradition and long-term indoctrination, this could also be the result of availability of infrastructural support including computers, printers and self-study spaces. Most importantly, the comprehensive-type ILS offers a one-stop experience, enabling students to stay for long hours for multiple purposes, without the need to change locations and offering more spaces for large group of students. Yet, the comprehensive-type ILS is usually overcrowded and students are unable to find a seat, exacerbated by some students’ seat occupying behaviour for sleeping, relaxing and seat hoarding.

Furthermore, Figure shows the positioning map of ILS types based on time spent and frequency of usage. While the ILS types are distributed in different positions of the quadrants, they are currently serving different purposes in terms of usage occasions. The pictorial illustration provides directional indication, but not all ILS types need to move to the top right quadrant. This needs to be considered alongside with practical needs, space availability and investments required.

Our research found that the other ILS could supplement the highly used comprehensive-typed ILS by developing a well-designed master plan. For instance, the other types of Indoor ILS may serve the overflow from the comprehensive-typed ILS. Indoor (quiet) ILS is the closest substitute given its quiet nature and the proliferation for study (self or group) use occasions. Besides, Indoor (talking allowed) ILS supports socialization and collaboration, apart from learning and studying. Group discussions and study with friends indicate that this ILS type not only supports conventional studying, but also offers spaces for peer learning. Designing different types of ILS elucidates how a university could determine the appropriate amount of space for various purposes and maximize the use of ILS (Abramson & Burnap, Citation2006). This practice could avoid a sprawling, fragmented and isolated environment at universities (Coulson et al., Citation2015). As a result, each type of ILS should not be considered individually, a general master plan could assist higher education institutions to better utilize the entire campus for purposely designed ILS.

Our research also observed the relevance of master planning and the Theory of Constraints. As the sample university is located in the city centre with limited opportunities for expansion on its limited land, the geographical location poses a challenge for senior management to plan the layout of the campus. The sample university utilizes Outdoor ILS for dining and waiting, both for solo and group situations. Even though there is negative feedback on the condition and weather, Outdoor ILS has a role to play in the portfolio of ILS. Since most Outdoor ILS areas are located next to foodservice and take-away catering outlets, most students would use Outdoor ILS for a quick bite. On the other hand, Indoor (sofa) ILS serves an entertaining purpose (i.e., relaxing or rest) for students. Students rarely just use sofa area during their time on campus, perhaps due to limited availability and the transient nature of usage. The main purpose of using sofa (i.e., to rest and to wait for friends or class) highlights that sofa is not an ILS for congregation, long discussion or studying, which tends to be less utilized by students. These two types of ILS tend to be less important for studying and learning but socialization plays an essential role for students’ campus life. Adopting a well-designed master plan and acknowledging the constraints that the university owns, senior management could turn some peripheral areas, which are less discoverable, to be ILS for students’ use. Although the location may not be ideal, it echoes the intention of realizing the resources to improve the overall system as elucidated in the Theory of Constraints literature (Goldratt, Citation1990). Using the master plan to incorporate both learning and socializing in ILS could enhance student experiences, promoting a more welcoming campus (Bady & Konczal, Citation2012).

Overall, this research argues that different types of ILS would demonstrate a different usage pattern and preferences for students. However, such preferences do not justify the need of having the comprehensive-typed ILS only and remove other types of ILS. As TOC notes if the constraints are of physical nature, the goal is to make the object of constraints as effective as possible (Rahman, Citation1998), the adoption of a master plan helps central management to exert more monitoring in order to maintain the right usage and throughput. Additional types of ILS could be renovated to meet the anticipated capacity behind demand issue and utilize the land resources that usually inhibits campus development (Cunningham & Walton, Citation2016).

5.2. Needs assessment of different types of ILS

Existing ILS breakdown and preferences of ILS indicate that each type of ILS represents a unique usage and could be supplementary to one another, despite the figures are rough indication and not used for apple-to-apple comparison. Suggestions for each ILS type are made to improve the ILS and to formulate a new direction in the master plan by combining the current usage and students’ feedback on future development.

Comprehensive-type ILS provides an excellent venue for informal learning but suffers from space constraints. From a capacity planning point of view, the findings suggest the priority is to have more Indoor ILS (Beckers et al., Citation2016) to mitigate the overcrowding issue. Students expressed an overwhelming need for more self-study spaces and group discussion areas on campus. Indoor (quiet) and Indoor (talking allowed) ILS are ideal choices for fulfilling students’ demands based on usage occasion analyses, and students also expressed high intention to use indoor facilities. Given the scarce resources, this problem can be addressed by repurposing under-utilized areas in different zones on campus and including desired amenities to compensate for the lack of flexibility. A campus-wide blanket search and inventory of un- or under-utilized spaces could be a good start to encourage students to use the entire campus without spending a huge investment for a second comprehensive-type ILS, i.e., the library.

Aside from the Library, the duration of using Indoor (quiet) ILS is longer than other types, reflecting the self-study purpose of using the space. Unlike the Library, these ILS areas were reported as having limited facilities, such as washrooms, drinking fountains and printers nearby. Besides, Indoor (talking allowed) ILS areas were occupied for waiting for class or taking a rest, although serendipitous learning could possibly be taken place. This underscores the diversity of usage occasions, as these ILS are conveniently located near classrooms and lecture halls. Furthermore, the medium usage frequency could be due to the lack of basic amenities, pointing to the need for inclusion of facilities nearby if more Indoor (quiet) ILSs are to be built. Yet, the usage of this ILS type implies the desirability of it, despite a less preferred option than the Library. Hence, improvements can be made, such as more comfortable chairs with better back support for extended usage and different on-site facilities, including drinking water and printers. A relatively larger space to accommodate different behaviors with partitions and different furniture and fixtures for flexible use could be needed, otherwise, it can create disruptions among users with different purposes. These enhancements could increase students’ usage intention by providing a more well-rounded experience and enhance their satisfaction with the space.

For Outdoor ILS, the key is to enhance its functionality and usage by more frequent maintenance and cleaning as a starter. Improvements should address poor hygiene, noise and unstable weather-related issues to overcome the lack of shelter, a the potential cause of the short duration at Outdoor ILS. Fans should be provided to improve the ventilation of some areas and anti-mosquito machines can be installed. Students may be more willing to use them for group discussions and other learning purposes if the issues of climate control, shelter and device charging could be resolved.

For Indoor (sofa) area, its role would be to act as a buffer zone for students between classes. The strategy is to place them in appropriate places where students would go en-route to and from classes. Odd spaces or wide corridors could be converted easily as the space requirements and investments are minimal, and yet sofas can be flexibly arranged. The key is to find the right type of furniture, which will provide a relaxing atmosphere but also blend into the existing building structure. However, for existing areas that are considerable in size, with a large number of sofas, due to low utilization, these areas could be converted to the other indoor ILS types to increase utilization.

6. Limitations and future research

To begin with, as it is a case study in a university in Hong Kong, the classification of ILS and the results could be limited to the context in Asia-pacific and / or universities in a metropolitan area. Universities from the globe could design the ILS based on their unique features and geographical location. Our study may not include all types of ILS, but the systematic thinking and classification methodology could provide a pivotal guide for academic developers to evaluate their ILS, designing a proper mix of different types of ILS for their universities. Similar approach could be also conducted to understand students’ preferences and usage, enlightening the ILS development for respective universities.

While some findings are generalizable (e.g., types of ILS), the contextual parameters may mean different university environments could result in different usage patterns and user needs, and, hence deriving different conclusions. Cultural differences may also come into play. PolyU is centrally located in a business district, while other universities may be located in a suburban or rural area. These may create dynamics on students’ needs and usage of ILS. As more studies of similar nature using the same approach are conducted, theories about ILS development can be conjectured in order to provide guidance on how each ILS type should be designed under relevant constraints.

Besides, this study spent minimal attention in how ILS benefit students’ learning outcomes and learning experiences. Due to its exploratory nature, this paper presents the types of ILS and describe their usages. Future research should further understand whether ILS could help students to learn better. For example, whether the existence of ILS motivate students to work harder. These results would provide more information for university management to develop the master plan, along with the usage and preference results that this study synthesized.

7. Conclusion

This study adds to the body of knowledge in ILS literature by championing a case study approach in measuring ILS preference and behavior for an entire university, which can be extended to any universities using the same procedure. Based on a capacity planning, conceptual mapping and theory of constraints guided approach, the benefits of this work provide user-generated classification of ILS types and usage occasions, as well as recommend prioritized development of specific ILS types, and preferred features and functionalities for each ILS type. These recommendations provide valuable inputs to the master planning process in ILS development. A base-line assessment on usage and preference with ILS satisfaction, is recommended for any universities that wish to embark on this approach. The broader implication is that an adequate number of ILS with preferred designs would attract students to stay on campus longer for informal learning and socializing. The general principle adopted in the study applies to any universities, but given each university operates under different context, user-generated output in the qualitative phase will drive the quantitative measurement (such as ILS types and use occasions) on a university-wide basis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abramson, P., & Burnap, E. A. (2006). Space planning for institutions of higher education. Council of Educational Facility Planners, International.

- Bady, A., & Konczal, M. (2012). From master plan to no plan: The slow death of public higher education. Dissent, 59(4), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1353/dss.2012.0090

- Beckers, R., van der Voordt, T., & Dewulf, G. (2016). Why do they study there? Diary research into students’ learning space choices in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(1), 142–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1123230

- Cha, S. H., & Kim, T. W. (2015). What matters for students’ use of physical library space? The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(3), 274–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.03.014

- Chin, D. C., Hsu, C. H. C., & Yau, K. T. (2021). Developing a taxonomy of informal learning space. International Journal of Education, 13(4), 86–105. https://doi.org/10.5296/ije.v13i4.19016

- Cochran, J. K., & Uribe, A. M. (2005). A set covering formulation for agile capacity planning within supply chains. International Journal of Production Economics, 95(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2003.11.014

- Coulson, J., Roberts, P., & Taylor, I. (2015). University planning and architecture: The search for perfection. Routledge.

- Cox, A. M. (2018). Space and embodiment in informal learning. Higher Education, 75(6), 1077–1090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0186-1

- Cunningham, M., & Walton, G. (2016). Informal learning spaces (ILS) in university libraries and their campuses. New Library World, 117(1/2), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/NLW-04-2015-0031

- Davies, M. (2011). Concept mapping, mind mapping and argument mapping; What are the differences, and do they matter? Higher Education, 62(3), 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9387-6

- Goldratt, E. M. (1988). Computerized shop floor scheduling. The International Journal of Production Research, 26(3), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207548808947875

- Goldratt, E. M. (1990). The haystack syndrome: Sifting information out of the data ocean. North River Press.

- Hajrasouliha, A. (2017). Campus score: Measuring university campus qualities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 158, 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.10.007

- Halla, F. (2007). A SWOT analysis of strategic urban development planning: The case of Dar es Salaam city in Tanzania. Habitat International, 31(1), 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2006.08.001

- Harrop, D., & Turpin, B. (2013). A study exploring learners’ informal learning space behaviors, attitudes, and preferences. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 19(1), 58–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2013.740961

- Ibrahim, N., & Fadzil, N. H. (2013). Informal setting for learning on campus: Usage and preference. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 105, 344–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.11.036

- Ibrahim, N., Fadzil, N. H., & Saruwono, M. (2018). Learning outside classrooms on campus ground: A case study in Malaysia. Asian Journal of Behavioural Studies, 3(9), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.21834/ajbes.v3i9.68

- Joiner, C. (1998). Concept mapping in marketing: A research tool for uncovering consumers’ knowledge structure associations. Association for Consumer Research. In Advances in consumer research (Vol. 25, pp. 311–322). Association for Consumer Research.

- Matthews, K. E., Adams, P., & Gannaway, D. (2009, May). The impact of social learning spaces on student engagement. Queensland University of Technology. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual Pacific Rim First Year in Higher Education Conference (Vol. 13, pp. 1-10). Queensland University of Technology.

- Matthews, K. E., Andrews, V., & Adams, P. (2011). Social learning spaces and student engagement. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.512629

- Meshram, D. S. (2006). Interface between city development plans and master plans’. ITPI Journal, 3(2), 1–9. https://www.itpi.org.in/pdfs/newsletters/newsletter-2006-apr.pdf

- Morieson, L., Murray, G., Wilson, R., Clarke, B., & Lukas, K. (2018). Belonging in space: Informal learning spaces and the student experience. Journal of Learning Spaces, 7, 2. https://libjournal.uncg.edu/jls/article/view/1667

- Niknazar, P., & Bourgault, M. (2017). Theories for classification vs. classification as theory: Implications of classification and typology for the development of project management theories. International Journal of Project Management, 35(2), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.11.002

- Radloff, P. (1998, February). Do we treat time and space seriously enough in teaching and learning? In Teaching and Learning in Changing Times. Proceedings of the 7th Annual Teaching Learning Forum. The University of Western Australia.

- Rahman, S. U. (1998). Theory of constraints. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 18(4), 336–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443579810199720

- Temple, P. (2008). Learning spaces in higher education: An under-researched topic. London Review of Education, 6(3), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/14748460802489363

- Waldock, J., Rowlett, P., Cornock, C., Robinson, M., & Bartholomew, H. (2017). The role of informal learning spaces in enhancing student engagement with mathematical sciences. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 48(4), 587–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2016.1262470