Abstract

Engagement is an essential aspect of the learning process. To attain academic success, students must always be engaged. Because of the epidemic’s global spread, most learning has been moved online. Traditional students today face a new challenge with the proliferation of online education. This abrupt adjustment may impact their learning behaviour and willingness to embrace change. Consequently, their enthusiasm for studying may decrease dramatically. During COVID-19, this study investigated the level of engagement among Jordanian EFL students in their virtual classrooms. A “student course engagement questionnaire” was administered to 602 Jordanian EFL university students (males = 323, females = 297). The results showed that Jordanian EFL Students generally had a moderate engagement level during the epidemic. While skills, emotional, and interaction engagement factors received a moderate level of engagement, only the performance factor received a high engagement level. Fewer than one-quarter of Jordanian EFL students acknowledged dissatisfaction with their virtual English classes, whereas the highest percentage reported being somewhat satisfied. The study’s sample perceptions towards their engagement level were statistically significant due to their gender and university level. The presence of a teacher adds substantially to the development of interactive engagement communities and, as a result, the improvement of students’ language skills. When the teacher’s role is creatively played, a constant teacher-student interaction arises. These findings were taken into consideration when providing limitations and recommendations.

1. Introduction

There has been a downturn in educational activities worldwide due to the pandemic, causing disruptions to career plans and learning opportunities. With the commencement of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, academic institutions have taken drastic measures to limit the blow-out of the disease by maintaining safe learning environments and minimising physical contact. Online learning received numerous investments during the pandemic as a much-needed alternative to face-to-face teaching, necessitating a study to evaluate how effective classroom instruction is (Al-khresheh, Citation2022a; Oraif & Elyas, Citation2021; Thaheem et al., Citation2021; Yassine et al., Citation2022).

When the Coronavirus outbreak occurred, traditional classrooms went virtual. This has led institutions of learning to look beyond attracting students with physical aesthetics to promptly educate, retain, and graduate students through effective engagement techniques. Engaging students while simultaneously teaching and managing the classroom is challenging and complex. Student engagement is typically characterised as the level of cognitive, emotional, and behavioural communication between students and their learning environment (Alghamdi et al., Citation2020; Cents-Boonstra et al., Citation2020; Gonzalez et al., Citation2020), but it is seen as essential for students’ future success (Quin, Citation2017).

New ideologies, cultures, and mechanisms form the basis of remote learning, which may be unfamiliar to educators and learners worldwide (Almaghaslah & Alsayari, Citation2020), and Jordan is no different. The Jordanian “Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research” announced in March 2020 the suspension of teaching activities on universities’ campuses and the switch to synchronous online learning platforms as the primary means of learning (Alsoud & Harasis, Citation2021). As a result of this announcement, Basheti et al. (Citation2022) stated academic institutions in Jordan needed to upgrade their existing virtual learning modalities by utilising technology to create virtual classrooms over the Internet. During the pandemic, continuous learning and teaching were provided via these online platforms.

Due to the fact that most learners were not familiar with the virtual learning platforms prior to the outbreak, it was hypothesised that the level of English language students’ engagement on virtual learning platforms in Jordan was significantly impacted by the pandemic. Following the dramatic and unexpected transition from traditional to virtual learning, the primary objective of this study is to determine how COVID-19 has affected English language students’ engagement in virtual classrooms. A further objective of this study is to compare the changes that have taken place in online and on-site learning environments due to the transition to virtual classrooms. Accordingly, this study is guided by three research questions:

What level of engagement do university students have in classes when online learning is incorporated in the Jordanian EFL context?

To what extent do Jordanian EFL students feel satisfied receiving instruction via online classes?

Do gender and university level statistically affect how Jordanian EFL students perceive their virtual engagement?

2. Literature review

2.1. Traditional classroom education to online distance learning

As the largest sector in Jordan’s economy, the Information and Communications Technology sector has been growing at a 25% annual rate (Younesi & Hawamdeh, Citation2021), accounting for 12% of the country’s GDP and supporting more than 84,000 jobs. Technology was indispensable during and after the pandemic because it provided the only means of communication, keeping people informed about global events and ensuring the continuity of learning worldwide. Despite the physical distance between people during the COVID-19 pandemic, a virtual environment was created to get people from all over the world together, thereby creating a unique yet diverse classroom (Bird et al., Citation2022; Oraif & Elyas, Citation2021; Osman, Citation2020; Thaheem et al., Citation2021).

Among the many benefits of virtual learning classrooms are saving time, protecting individual health and community safety, introducing learners to new learning approaches, providing extra time to study alone, and making online learning materials simple (Al-Balas et al., Citation2020; Dung, Citation2020; Liu et al., Citation2021). Despite not being a novel learning method, online instruction has proven to be an adequate substitution for face-to-face instruction (Elzainy et al., Citation2020; Onyema, Citation2019). Kazem and Ashoor (Citation2022) argue that online learning leads to inconsistent educational results because of the lack of a physical instructor, which further erodes student-teacher relationships. The result is a low level of engagement that will eventually negatively impact language learners.

Recently, the use of technology has dramatically improved the way we learn. In particular, e-learning has been widely utilised in education as one of many notable examples of the influence of modern technology (Alodwan, Citation2021). The use of information technology in the design of virtual learning experiences was emphasised by Hoq (Citation2020) in his study on e-learning during the Coronavirus pandemic. As a result of a virtual learning environment, students can access course materials from anywhere at any time without having to visit a physical classroom or communicate directly with the instructors (Khlaif et al., Citation2021; Verawardina et al., Citation2020).

An examination of students’ language acquisition methods in Moodle-based language acquisition programs conducted by Khabbaz and Najjar (Citation2015) asserted that evolving technologies in language learning might impede autonomous learning. Sen and Antara (Citation2018) found that online instruction is not a viable substitute for face-to-face instruction during a crisis. Virtual classrooms, especially in rural areas, are also hindered by technological challenges in a developing country like Jordan (Cacault et al., Citation2021; Di Vaio et al., Citation2020).

2.2. The Jordanian context and covid-19 education

The rapid expansion of technology in education brought about by the pandemic is a welcome development, even though technology has some disadvantages. A seamless technological shift can be facilitated with proper training and awareness of its utility. Therefore, a review of COVID-19ʹs effects on Jordanian education is required.

With COVID-19, education underwent a profound change resulting in the emergence of e-learning platforms whereby learning is now conducted virtually or remotely (Khlaif et al., Citation2021). Due to Jordan’s robust education system and high student population, it has become essential to focus on this group during the global pandemic (Basheti et al., Citation2022; Bataineh & Atoum, Citation2021).

Through virtual classrooms, learners and educators could simplify course content, collaborate over long distances, and facilitate online examinations and discourses despite geographical constraints (Al-Okaily et al., Citation2020; Bond et al., Citation2020). In response to the pandemic, Jordan’s Ministry of Education developed Darsak, a continuous learning portal incorporating materials from the private sector. Two online lecture channels covering core subjects, including English, mathematics, and Arabic, were then established due to the pandemic.

Furthermore, the “Ministry of Higher Education” has integrated online learning into its long-term plans since it has become a predominant mode of learning in recent years and has proved to be a successful model in Jordan (Basheti et al., Citation2022).

Similarly, Alodwan (Citation2021) concluded after conducting a study in Jordan that COVID-19 lessened students’ motivation to learn because it caused disengagement, isolation, and a lack of interaction between them and the community. A chatbot technology was developed by Wu et al. (Citation2020) to increase learners’ engagement by reducing feelings of social isolation and detachment through daily conversations and as a supplement to course materials on e-learning platforms. To keep EFL students engaged with their virtual classroom lessons and maintain optimal academic performance, finding ways to minimise detachment and maximise engagement is crucial.

2.3. Engagement in the foreign language classrooms

The concept of engagement gained through technology-based instructional experiences will serve as the research’s theoretical foundation. According to the principle of engagement, students engage in learning activities through social contact and meaningful activity assignments (Bernacki et al., Citation2020). Technology-based learning, according to researchers, comprises collaborative efforts and project-based individual and group assignments, which can encourage innovative, meaningful, and authentic learning (Buckley, Citation2018). The primary premise of engagement theory is that students must be actively involved in their education. Engagement theory holds that students involved and enmeshed intellectually, socially, and behaviorally lead to enhanced learning (Lawson & Lawson, Citation2013). This research will be guided by three comment components of engagement theory: intellectual, social, and behavioural engagement. These comment components were classified into skills engagement, emotional engagement, participation or interaction engagement, and performance engagement (Handelsman et al., Citation2005; Oraif & Elyas, Citation2021; Orak & Al-khresheh, Citation2021)

Intellectual engagement signifies that students are cognitively invested in their academic work, which can result in going above and beyond expectations and embracing learning challenges (Kahn, Citation2014). Intellectual engagement is characterised by a student’s motivation and interest in the subject, which leads to high-quality instruction. Intellectual engagement is also defined as a person’s cognitive and psychological investment in learning (Sefcik, Citation2013; Willms et al., Citation2009). Social engagement refers to the positive student, peer, and teacher interactions (Eldegwy et al., Citation2018). Social engagement in learning settings refers to the extent to which students network and connect for academic and social purposes online, in forums, and on portable devices (Martin, Citation2011). Behaviour engagement signifies that students adhere to behavioural norms, such as regular attendance and participation, and refrain from disruptive and negative behaviours (Al-khresheh, Citation2022b; Baron & Corbin, Citation2012). Students lack a personal voice in large classrooms, which diminishes engagement. Behavioural involvement can involve students setting personal goals like passing an English proficiency test or improving research abilities under the teacher’s guidance.

Particularly, students’ engagement with language learning is a critical factor in their success throughout all education levels (Carroll et al., Citation2019; Dixson, Citation2015). Educators, school leaders, and faculty members’ level of engagement is determined by the degree to which they participate in curriculum design, the provision of learning opportunities, and the decision-making process (Wang & Fredricks, Citation2014). As a prerequisite for success, engagement is defined as feeling a sense of belonging to a place or activity (Bond et al., Citation2020; Dubeau et al., Citation2017; Stevens et al., Citation2018; Wigfield et al., Citation2015). Marx et al. (Citation2016) define student engagement as the degree of communication between the students and their learning atmosphere on a cognitive, emotional, and behavioural level.

Furthermore, Handelsman et al. (Citation2005) cited Skinner and colleagues’ who referred to engagement as “children’s initiation of action, effort and persistence on schoolwork, as well as their ambient emotional states during learning activities” (p. 24). Student engagement is also thought to contribute to high levels of academic success and prevent dropouts (Carroll et al., Citation2019; Lei et al., Citation2018). Observable behaviour directly associated with learning is also measured as part of engagement (Cents-Boonstra et al., Citation2020; Korlat et al., Citation2021).

Efficacious engagement of students can take many forms. According to Bowden et al. (Citation2017), student engagement encompasses four distinct, yet interdependent dimensions: cognitive, behavioural, affective, and social. In behaviorally engaged students, observable behaviours directly related to learning are undertaken (Skinner, Citation2016). A student can engage in a behavioural engagement at two levels: passive participation, which involves focusing on class material, and active participation, which involves participating in class assignments and asking questions (Nguyen et al., Citation2018). A cognitively engaged student is someone who understands the importance of education and expresses it through setting learning goals for themselves (Van Uden et al., Citation2014). A cognitive dimension also entails regular and active mental processes aimed at primary engagement objects (Vivek et al., Citation2014). Affective dimensions of engagement pertaining to student passion, mutual emotional levels and long-term dedication toward tertiary education (Bowden, Citation2013). A sense of connection with the institution, social interaction, inclusiveness, and affiliation are all social dimensions of engagement (Eldegwy et al., Citation2018). They indicate students’ affective reactions to classroom activities, as evidenced by their expressions of enjoyment (Hollister et al., Citation2022; Van Uden et al., Citation2014).

In terms of the importance of engaging students, research suggests that active participation leads to enhanced academic achievements (Aji & Khan, Citation2019; Sanitchai & Thomas, Citation2018), even though more participation does not necessarily constitute engagement as it is viewed as just one dimension of engagement (Kanellopoulou & Giannakoulopoulos, Citation2020). Engaged students have a remarkable chance of achieving their academic and personal goals (Myint & Khaing, Citation2020).

During language learning, it is critical to evaluate student engagement in the learning process to determine whether or not the instructions and academic practices are adequate. By incorporating this approach, educators can develop more engaging teaching strategies that improve learning outcomes. Delfino (Citation2019) makes the case that the data collected during the learning process is crucial to helping academic institutions better serve their students’ learning needs.

Certain factors have been identified as contributing to student engagement in language learning, especially in a virtual environment. DeVito (Citation2016) identifies the factors contributing to student achievement: a supportive classroom environment, a supportive family, communication, interactions between learners and teachers, collaboration, academic challenge, enriching educational experiences, and active involvement of students in the classroom. The factors that affect students’ engagement in traditional and virtual classrooms can be optimised by educators who are open-minded and willing to take part in virtual training that will enhance their teaching process. Active participation by students will bring significant benefits to the virtual classroom teaching process as they will become more involved in learning. A teacher’s ability to interact with their students can significantly impact their engagement, as claimed by Quin et al. (Citation2017).

Social status might also have contributed to low levels of engagement in virtual classrooms during the pandemic since many families lack internet access or the necessary technology to participate in virtual classrooms (Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018). A student’s learning motivation and competence are affected by the support and expectations of the family, including a family’s socioeconomic status, parental support, and material resources (Elliot et al., 2017; Ericsson et al., Citation2018). The same applies to people who lack digital skills and educational resources that allow them to learn online. During the pandemic, many students have been unable to access virtual classrooms due to low internet speeds and a lack of adequate devices (Van Lancker & Parolin, Citation2020). Students lacking technical know-how may also have difficulty accessing technology, compromising their engagement.

In the case of students with special needs and learning disabilities, virtual classrooms are not considered to be as effective as face-to-face instruction because they require heightened physical attention and guidance from their teachers (Yassine et al., Citation2022). Pandemic-induced lockdowns or an inability to tolerate uncertainty will make it difficult for students with mental health issues or those from abusive homes to participate fully in online learning. Long-term school closures may negatively affect students’ mental and physical health, according to McGowan (Citation2020).

As a result of less engagement and disconnectedness from learning, students often have poor social outcomes, low academic performance, and disruptive behaviour. Therefore, ensuring effective learning and student success requires an emotional, behavioural, and psychological level of student engagement (Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018; Van Uden et al., Citation2014; Yassine et al., Citation2022).

Research has demonstrated that both on-campus and online learning has advantages and disadvantages. Both in-classroom and online students achieved alike in practice-based language education classes, as measured by their internship performance (Halim, Citation2021; Kissau, Citation2015). Mollenkopf et al. (Citation2017) compared student-teacher outcomes in online and face-to-face programs and found that both programs produced equally good results for graduate students in teacher education. According to Ortega-Maldonado et al. (Citation2017), online students are generally older and have full-time jobs, a more diverse range of work, and life experience. They develop superior analytical abilities compared to on-campus students, resulting in higher self-efficacy, beliefs, competencies, and knowledge levels.

A study conducted among EFL learners who received online instruction found that technology-related factors such as technical difficulty and unfriendliness influenced their satisfaction with online learning. Even the best-designed online course can lead to ineffective learning (Hossain, Citation2021; Wingo et al., Citation2017). In recent years, evidence indicates that students are less tolerant of delays in downloading learning resources and expect educators to be available 24/7 to answer their questions in online discussions and late emails (Roberts et al., Citation2012). Students’ dissatisfaction was also impacted by unclear learning expectations, inadequate faculty interaction, and unclear evaluation criteria (Martin et al., Citation2018; Pham et al., Citation2019).

In a study by Alkhalil et al. (Citation2021), Jordanian students reported being satisfied with their university’s online teaching and learning capabilities. According to Elshami et al. (Citation2021), online learning is convenient and flexible. It offers many tools and resources that learners find helpful. Peer interaction also seemed to enhance student learning opportunities while optimising their learning experience (Elshami et al., Citation2020). Additionally, their findings indicate that interactive multimedia during online learning stimulates problem-solving skills, authenticity, and knowledge development (Gedik et al., Citation2013). Last but not least, they assert that online discussion aids in virtual classroom success (He & Freeman, Citation2009; Kwon et al., Citation2019) as students engage in the content through active discussion rather than passive listening via discourses and reflections (Elshami et al., Citation2021).

In the wake of the Coronavirus pandemic, a rich library of literature demonstrates its impact on educational activities, including the rapid shift to virtual classrooms from traditional classrooms. COVID-19 has not been studied in depth in terms of how it affects EFL students’ engagement and feelings in virtual classroom lessons. In light of this, it was necessary to conduct this research. Therefore, this study aims to examine Jordanian EFL students’ engagement with online learning in the wake of the virus and their perception of online learning.

3. Research design

Jordanian University EFL students were studied in this research to determine how much they engage in virtual classrooms. In order to accomplish this, This study employed a quantitative descriptive design, which resulted in a bigger sample size and a quicker data collection process. This study utilised survey research because it is the most fundamental method for quantitative outcome research studies. Furthermore, it is regarded as reasonably simple to administer and can lessen or eliminate physical dependence. Target sample members were sent a questionnaire via random sampling. It was decided to employ random sampling to enhance the chances of error-free data analysis. This is the simplest method for gathering data and is the best way to choose a sample from a population of interest (Babbie, Citation2005; Gay & Airasian, Citation2005).

3.1. Participants

This study included 602 Jordanian male and female university EFL students between the ages of 18 and 28, all of whom are bachelor’s students majoring in the English language. They represent different university levels: freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors. The coronavirus outbreak has forced them to study from home. It is the first time that they are studying at home. Their social and socioeconomic backgrounds are homogeneous. They are all native Arabic speakers. Table represents their statistical characteristics.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants

3.2. Instrument

This study employed a questionnaire as it does not allow much variation, making it a good tool for examining the phenomenon in depth. A questionnaire can be completed at any time and from any location by the respondent, providing them with immense flexibility. Moreover, it would provide better insight into an existing case (Gay & Airasian, Citation2005). A “Student Course Engagement Questionnaire” (SCEQ) by Handelsman et al. (Citation2005) was used in the study. It was distributed to 602 Jordanian university students in order to measure their engagement in their online English courses. Multiple studies have validated the SCEQ and have demonstrated that it is an effective method for assessing student course engagement (Nguyen et al., Citation2018). The coefficient alpha was between 0.76 and 0.82, which indicates high internal consistency. In the questionnaire, 23 items were rated on a Likert scale to assess students’ perceptions of their behaviour, thoughts, and feelings when engaging with their course. The items were classified into four main categories. The first is “Skills course engagement”: This construct involves taking notes, reading assigned materials, and attending classes. The second one is “Emotional course engagement”: The expression of this construct is non-observed behaviour that demonstrates emotional engagement in the course, such as thinking about it between classes and finding ways to make it relevant and interesting. The third one is “Participation/interaction course engagement”: A student who participates actively in class and interacts with the instructor and other students, for example, by raising their hand and participating in small group discussions, is characterised by this construct, which denotes observable behaviours. The last one is “Performance course engagement”: Performance in class, for example, achieving good grades and performing well on tests, describes this construct. The responses to the SCEQ were rated on a five-point Likert-type scale: 1 (very characteristic of me), 2 (characteristic of me), 3 (moderately characteristic of me), 4 (not really characteristic of me), 5 (not at all characteristic of me).

3.3. Data collection and analysis

In advance of data collection, preparations were conducted to get consent from five English language departments in Jordan. Considering COVID-19 restrictions, data were collected online at the end of the second semester of the academic year 2020–2021, within one month. During the data collection period, the participants had been studying remotely for almost a year and a half. As a result, they can share their experiences with online learning. Using Google Forms, an electronic survey was created and snowballed out to study participants. The Google form link was sent to a group of EFL teachers tasked with sending them to their students. Teachers were informed of the study’s purpose and asked to explain it gently to students. They were requested to provide the questionnaire’s link to their students at the end of their lectures, emphasising the importance of the study. The Google link form was circulated multiple times to reach the sample population. The participants were informed of the study’s purpose on the questionnaire’s first page. All participants were requested to agree to use their data in this study. In addition to keeping all data confidential, it was stated that data would not be revealed unless necessary for this study.

As a next step, SPSS version 26 was used to code and analyse the data. At each measurement level, descriptive measures were included in the data analysis. Microsoft Office Excel was used to tabulate the data. Frequency, percentage, means and standard deviations were presented. To determine whether quantitative variables were significantly associated, ANOVA was applied to study the impact of two independent variables (gender and university level) on a dependent variable (Participants’ perceptions). Remarkably, this was done to answer the third research question.

3.4. Validity and reliability of the questionnaire

A panel of EFL experts reviewed the instrument to ensure content validity and suitability for the study. They were asked to avoid redundant statements, examine all items’ dimensions, and check language accuracy. In accordance with the suggestions of the experts, all statements with a consensus of 80% or higher among the experts were retained as dimensions. No items were eliminated. A few words have been modified throughout. A reliability test was also performed using SPSS software to check the internal consistency of the questionnaire. Table displays that Cronbach’s Alpha values ranged from 0.624 to 0.835. These values are considered within the desired range for such instruments. Furthermore, the correlation between the items and their dimension was statistically significant.

Table 2. Cronbach’s Alpha

Considering the Cronbach’s alpha values for each engagement factor separately in Table , Table below presents the correlation coefficients between the degree of each item and the overall questionnaire score. At the level of significance (0.01), all indicated correlation coefficients are significant. As a result, the questionnaire items have been deemed valid for the purposes for which they were designed.

Table 3. Item correlation coefficients values

4. Results

Each factor was measured by means and standard deviations to determine the level of engagement. In order to present the analysed data, the tabulation method was used. Due to the five-point Likert scale in this study, the following formula was used to determine the arithmetic averages: (The highest value in the scale—the lowest value)/5 = (5–1)/5 = 0.80. Thus, the categories are as follows: (1–1.79) is very low; (1.80–2.59) low; (2.60–3.39) moderate, (3.40–4.19) high, (4.20–5) very high.

4.1. Skills engagement

As shown in Table , the level of skills engagement in students’ virtual classrooms was generally moderate, with a mean of 3.26 and a standard deviation of 0.72. The top item receiving the most skills engagement was “coming to class every day or logging on to the class webpage regularly”, while the remaining items received moderate engagement. There was moderate skill engagement among the students, as evidenced by this table.

Table 4. Descriptive analysis for the students’ skills engagement

4.2. Emotional Engagement

Similarly, Table demonstrates that the emotional factor had a moderate level of engagement, with a mean of 3.14 and a standard deviation of 0.76. The study participants reported moderate engagement with all items in this factor. Among the items, “Really desiring to learn the material” had the highest mean (mean = 3.30, SD = 1.05), while “Applying course material to my life” returned the lowest (mean = 2.97, SD = 1.14). It is evident from these results that the students were emotionally engaged in their virtual classrooms. There was also a moderate level of engagement.

Table 5. Descriptive analysis for the students’ emotional engagement

4.3. Participation/interaction engagement

According to Table , the level of engagement in participation and interaction factor was moderate, with a mean of 3.33 and a standard deviation of 0.77. The highest engagement levels were reported with item 6, “helping fellow students” (mean = 3.54, SD = 1.11). In comparison, the lowest mean value was reported with item 4 (mean = 3.18, SD = 1.15), “Going to the professor’s office hours or contacting him/her to review assignments or tests, or to ask questions”. According to these results, students were also moderately engaged in their online classrooms when online learning was implemented.

Table 6. Descriptive analysis for the students’ participation/interaction engagement

4.4. Performance engagement

With a mean of 3.53 and a standard deviation of 1.02, the performance factor received a high level of engagement compared to previous engagement factors. Performance engagement was highest for “Getting a good grade” and “Doing well on tests”, while moderate engagement was reported for “Being confident that I can learn and do well in class”. Additionally, this indicates that the students were engaged in their performance.

4.5. Overall engagement level

Given the statistical results for each engagement factor separately, Table , Table summarises the overall results for all engagement factors. According to the table, Jordanian EFL students were moderately engaged in English classes when online learning was implemented. With the performance engagement factor, the mean was 3.44, and the standard deviation was 0.79, indicating that it was “High”. Regarding participation or interaction engagement, the average value was 3.33, and the standard deviation was 0.77, which is considered “Moderate.” In terms of skills engagement, it ranked third (3.26, SD = 0.72) and was defined as moderate. As the fourth-ranking factor (mean = 3.14, SD = 076), emotional engagement is also defined as “Moderate.”

Table 7. Descriptive analysis for the students’ performance engagement

Table 8. Descriptive analysis for the students’ engagement factors

4.6. Students’ feeling towards receiving instructions in online English classes

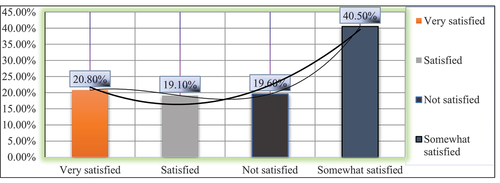

As shown in Figure , 40.50% of students felt “Somewhat Satisfied” with their English class experience, 20.80% “Very Satisfied,” 19.10% “Satisfied,” and 19.60% “Not Satisfied.” However, these percentages indicate that the students demonstrated engagement in their virtual classes

Figure 1. Descriptive Analysis of Students’ Feelings about their Virtual Learning Experience

4.7. The anova analysis of the study variables

The two-way ANOVA analysis of the study variables is shown in Table below to illustrate statistically significant differences. According to the table’s data, there are statistically significant differences in perception between the study sample members based on their gender, which skew toward the male gender. Further, the university-level variable also significantly impacts the perceptions of study sample members.

Table 9. The Anova analysis of the study variables

In order to ascertain the discrepancies’ directions, the post-test was employed to find the least significant difference. The direction of these differences is illustrated in Table .

Table 10. Multiple comparisons—least significant differences

This table shows that Freshmen and Juniors have statistically significant differences in favour of Juniors. In addition, there is a statistically significant difference between freshmen and sophomores in favour of juniors. There is a statistically significant difference between sophomores and juniors in favour of Juniors. Juniors and seniors have a statistically significant difference in favour of Juniors.

5. Discussion

Theoretically, studies have demonstrated that engaging students in the learning process improves their concentration and attention and fosters more sophisticated critical thinking. Students with higher levels of engagement practise tremendous academic success and fulfilment. They are more likely to persist academically despite obstacles. They do more effectively on standardised test scores. They are more socially adept. Engaged enrolled in online learning achieve higher academic performance, improved social-emotional health, and enhanced school and peer relationships. There is a correlation between student disengagement and adverse outcomes, including absenteeism, dropping out, and even aggression (Bond et al., Citation2020; Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018). In light of these theoretical assumptions of student engagement, this section discusses the current study’s findings, taking into account an unanticipated learning setting induced by COVID-19.

The pandemic had a detrimental effect on educators and learners, resulting in moderate engagement in the virtual classroom. In contrast, Hollister et al. (Citation2022) found that 72 percent of online learners felt their experience was negatively impacted by low engagement during lectures. In addition to having difficulty maintaining contact with peers and instructors, many students also experienced difficulty adjusting to the pace of their studies.

When online learning was adopted, the performance factor had the highest level of engagement (Mean = 3.44, SD = 0.79), which is related to students’ grades. There was a moderate level of participation, skills, and emotional state among students, which may have been due to distractions caused by current events in the world, a lack of technical knowledge due to a sudden shift to virtual classrooms, and a fear of contracting the deadly virus, which impacted their emotional levels.

In terms of performance factor, students were highly engaged, possibly because the lockdown left them with plenty of time to study without distractions. In agreement with this study, Gonzalez et al. (Citation2020) found that online learning systems demonstrated reasonable progress in students’ academic year and a noticeable improvement in their learning performance. As Aji and Khan (Citation2019); and Sanitchai and Thomas (Citation2018) have also concluded, active engagement in virtual classrooms results in improved academic performance. Furthermore, Gonzalez et al. (Citation2020) reported that the COVID-19 confinement caused a significant improvement in students’ performance and changed their learning strategies to a more continuous habit resulting in improved performance.

Other studies indicated that low engagement levels during online learning might hinder grade-level performance. Bird et al. (Citation2022) found that a rapid switch from traditional classrooms to virtual classrooms resulted in a reduction of 8.5% in course completion, a rise in failures and dropouts, and an increase in negative impacts on students who were less academically prepared. According to Cacault et al. (Citation2021), having access to a live-streamed lecture as a substitute for attending a classroom lecture lowers the engagement rate of low-ability students while improving the engagement rate of high-ability students.

There was a high percentage of dissatisfaction with virtual classroom learning (40%) among EFL learners, followed by 20.4% who were somewhat satisfied, 18.9% who were satisfied, and 20.6% who were very satisfied with their experience. A variety of factors might affect these responses, including technical difficulties, the absence of interaction, technical expertise, etc.

This finding agrees with Wingo et al. (Citation2017) who argued that learners encounter technical difficulties and a lack of user-unfriendliness when participating in online courses, leading to ineffective learning experiences. A similar result was also found in a study carried out by Martin et al. (Citation2018) and Pham et al. (Citation2019) who argued that several factors contribute to students’ dissatisfaction with virtual classroom learning, including a lack of communication with faculty, uncertain learning prospects, and imprecise assessment measures.

Elzainy et al. (Citation2020) also supported the results of this study, which found that most students were dissatisfied with how educators practised e-learning in a study conducted at Saudi University. In a typical example, Roberts et al. (Citation2012) state that students’ expectations of instructors being available online 24/7 to respond to their comments and emails about online discussions were not met, therefore, the reason for their dissatisfaction.

Despite this, many students have stated their satisfaction with online learning in studies like Elshami et al. (Citation2020) who found that online classroom learning was convenient, flexible, provided a high level of communication, and provided a variety of communication tools that learners found satisfactory. Gedik et al. (Citation2013) conducted another study in which learners expressed satisfaction with virtual classrooms because they improved their problem-solving skills, provided authentic learning and helped them acquire new knowledge.

Students from Jordanian EFL classes perceived their English classes differently based on their university level and gender, indicating statistically significant differences in engagement. Considering the significant differences between perceptions and university level of students, this is possibly attributed to students’ awareness and maturity, especially those in their last two years of study and taking core subjects (such as juniors and seniors). Gender differences favoured males concerning the variable. A possible explanation for this could be that men are slightly more tech-savvy than women. The study’s results align with those of He and Freeman (Citation2009), who stated that females do not feel as confident when using computers compared to males since they have practised less and feel more apprehensive than men. This is contrary to Liu et al. (Citation2021) and Alghamdi et al. (Citation2020), who found significant differences between males and females in favour of females during the Covid-19 lockdown. Furthermore, Korlat et al. (Citation2021) found that female students were more engaged in virtual classes than male students.

6. Implications

The study’s findings suggest involving students in the learning process in virtual or traditional classrooms might increase their concentration and inspires them to participate in higher-level critical thinking. Involving students in the learning process, whether virtual or traditional, enhances their focus and concentration and offers an effective way to think critically. Varying classroom activities can surely make students more engaged and motivated. Moreover, minimising teacher control, engaging students, and adapting the new medium to meet everyone’s needs is the most efficient method compared to either properly disposing of the teacher or forcing a return to the status quo.

Teachers should be more engaged and encouraging, fostering great social environments and positive relationships with their students. Teachers should create aural and visual stimulation in a cooperative classroom. In cooperative learning, the teacher is responsible for fostering positive student interactions. The teacher has to set up interactions between students within the context of academic activities and get students ready to work together. Teachers should also introduce students to innovative new learning approaches. It is believed that innovation in education improves educational outcomes. Innovative classrooms are filled with students acquiring communication skills and interacting with their peers. Therefore, students become more able to personalise their experiences and contribute to the classroom learning environment. Through constructive critique, teachers act as creative guides, broadening their students’ experiences. Therefore, the teacher’s role must shift from one of authority to one of collaboration and participation. Successful online teachers have several characteristics in common, including the ability to think creatively, relevant experience, subject matter competence, and a large amount of preparation time with their students. An online teacher facilitates students’ academic success while enrolled in one or more virtual classes.

It is necessary to motivate students to utilize the modern media. This would help them turn something familiar into something new and beneficial in the classroom. Virtual teaching technology should not be required, but it should be pushed as a desirable choice and a potentially valuable educational tool. It could provide a broader selection of easily accessible materials and enhance students’ communication skills and academic performance.

Because of the various ways remote learning provides connection, students and teachers can build a dynamic environment accommodating student diversity. A dynamic classroom focuses on the learning processes rather than the outcomes. It promotes active rather than passive learning, enables students to understand issues better, and promotes favourable learning attitudes and behaviours (Oraif & Elyas, Citation2021). It is critical to remember that online students have various preferences regarding the most effective teaching strategies. As a result, online teachers must adapt their approaches to better meet their students’ needs. Teachers in a collaborative classroom contribute to a dynamic setting that promotes visual and auditory engagement. Beyond merely knowledge transfer, the teachers bring new teaching methods to the class. Students develop as thinkers and creators by creating their individual experiences and encouraging the learning environment. Using both visible and audible assistance, the instructor can act as a creative mentor who encourages the students’ learning by giving them insightful feedback. COVID-19ʹs primary value is highlighting this unique teaching and learning technique’s usability and potential and implementing it in the worldwide education system. Traditional educational techniques have been impacted by the rapid global advancement of technology, particularly in Jordan.

These dramatic changes in education are attributable to the impact of digital tools on the instructional decisions of both teachers and students. Digital learning can assist students and teachers in understanding the most successful teaching practices, resulting in more effective teaching and learning. In this crisis and beyond, enhanced online education offerings are required. This is required worldwide to facilitate language teaching and learning. Due to emergency conditions, universities are required to offer online and/or distance learning. Teachers must therefore adjust.

7. Limitations and directions for future research

There are some limitations to this study that need to be considered. The study was conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic. In light of this, a post-study comparing students’ perceptions of receiving instruction via online classes might be a good recommendation for future research. Using a questionnaire, this study investigated students’ perceptions of engagement using a quantitative approach. Further studies should be conducted using another qualitative method, such as interviewing. Students might have a better chance of expressing their level of engagement with virtual classes through an interview. Each engagement factor was examined in this study. Further research could also focus on a specific factor, such as skills. Students’ perspectives were taken into account in this study. Another suggestion for upcoming research is to examine the same topic from the teachers’ perspective. Previous research indicated that student engagement leads to more inspiring teaching performances and vice versa. To fully comprehend the connection between student involvement and teaching effectiveness, further in-depth research must be conducted in the future.

8. Conclusion

The findings suggest that a teacher’s presence contributes significantly to developing interactive engagement communities and improving students’ language abilities. A consistent teacher-student dynamic occurs when the teacher’s role is creatively played. All factors received a moderate level of engagement by Jordanian EFL students, except for the performance factors, which received a high engagement level. It is estimated that 19.60% of students were dissatisfied with their experience joining English classes. However, the majority reported a somewhat satisfying experience. Regarding engagement level, there was a statistically significant difference between students’ perceptions based on their age and university level.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aji, C., & Khan, J. (2019). The impact of active learning on students’ academic performance. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 7(3), 204–22. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2019.73017

- Al-Balas, M., Al-Balas, H. I., Jaber, H. M., Obeidat, K., Al-Balas, H., Aborajooh, E. A., Al-Taher, R., & Al-Balas, B. (2020). Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: Current situation, challenges, and perspectives. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 341. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02257-4

- Alghamdi, A., Karpinski, A. C., Lepp, A., & Barkley, J. (2020). Online and face-to face classroom multitasking and academic performance: Moderated mediation with self-efficacy for self-regulated learning and gender. computers in Human Behavior, 102, 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.018

- Alkhalil, S. M., Manasrah, A. A., Dabbour, L. M., Bashayreh, E. A., Abdelhafez, E. A., & Rababa, E. G. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic and the e-learning in higher institutions of education: Faculty of engineering and technology at Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan as a case study. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 31(1–4), 464–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2020.1829243

- Al-khresheh, M. (2022a). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teachers’ creativity of online teaching classrooms in the Saudi EFL context. Frontiers in Education, 7(1041446), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.1041446

- Al-khresheh, M. (2022b). Teachers’ perceptions of promoting student-centred learning environment: An exploratory study of teachers’ behaviours in the Saudi EFL context. Journal of Language and Education, 8(3), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2022.11917

- Almaghaslah, D., & Alsayari, A. (2020). The effects of the 2019 novel Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak on academic staff members: A case study of a pharmacy school in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy, 13, 795–802. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S260918

- Alodwan, T. (2021). Online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspectives of English as foreign language students. Educational Research and Reviews, 16(7), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2021.4169

- Al-Okaily, M., Malqudah, H., Matar, A., Lutfi, A., & Taamneh, A. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on acceptance of e-learning system in Jordan: A case of transforming the traditional education systems. Humanities and Social Sciences Reviews, 8(4), 840–851. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2020.8483

- Alsoud, A. R., & Harasis, A. A. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on student’s e-learning experience in Jordan. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(5), 1404–1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16050079

- Babbie, E. (2005). The basic of social research. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- Baron, P., & Corbin, L. (2012). Student engagement: Rhetoric and reality. Higher Education Research and Development, 31(6), 759–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.655711

- Basheti, I. A., Nassar, R. I., & Halalsah, I. (2022). The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the learning process among students: A comparison between Jordan and Turkey. Education Sciences, 12(5), 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/edusci12050365

- Bataineh, K. B., & Atoum, M. S. (2021). A silver lining of coronavirus: Jordanian universities turn to distance education. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology, 17(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJICTE.20210401.oa1

- Bernacki, M. L., Crompton, H., & Greene, J. A. (2020). Towards convergence of mobile and psychological theories of learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 60, 101828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101828

- Bird, K. A., Castleman, B. L., & Lohner, G. (2022). Negative impacts from the shift to online learning during the COVID-19 crisis: Evidence from a statewide community college system (EdWorkingPaper: 20-299). Annenberg Institute at Brown University. https://doi.org/10.26300/gx68-rq13

- Bond, M., Buntins, K., Bedenlier, S., Zawacki-Richter, O., & Kerres, M. (2020). Mapping research in student engagement and educational technology in higher education: A systematic evidence map. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0176-8

- Bowden, J. (2013). What's in a relationship? Affective commitment, bonding and the tertiary first year experience – a student and faculty perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 25(3), 428–451. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-07-2012-0067

- Bowden, J. L. H., Conduit, J., Hollebeek, L. D., Luoma-Aho, V., & Solem, B. A. (2017). Engagement valence duality and spillover effects in online brand communities. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(4), 877–897. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-04-2016-0072

- Buckley, A. (2018). The ideology of student engagement research. Teaching in Higher Education, 23(6), 718–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1414789

- Cacault, M. P., Hildebrand, C., Laurent-Lucchetti, J., & Pellizzari, M. (2021). Distance learning in higher education: Evidence from a randomised experiment. Journal of the European Economic Association, 19(4), 2322–2372. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvaa060

- Carroll, M., Lindsey, S., Chaparro, M., & Winslow, B. (2019). An applied model of learner engagement and strategies for increasing learner engagement in the modern educational environment. Interactive Learning Environments, 4(1), 757–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1636083

- Cents-Boonstra, M., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Denessen, E., Aelterman, N., & Haerens, L. (2020). Fostering student engagement with motivating teaching: An observation study of teacher and student behaviours. Research Papers in Education, 36(6), 754–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1767184

- Delfino, A. P. (2019). Student engagement and academic performance of students of Partido State University. Asian Journal of University Education, 15(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.24191/ajue.v15i3.05

- DeVito, M. (2016). Factors influencing student engagement. [Thesis – Sacred Heart University]. http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/edl/11

- Di Vaio, A., Boccia, F., Landriani, L., & Palladino, R. (2020). Artificial intelligence in the agri-food system: Rethinking sustainable business models in the COVID-19 scenario. Sustainability, 12(12), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124851

- Dixson, M. D. (2015). Measuring student engagement in the online course: The Online Student Engagement Scale (OSE). Online Learning, 19(4), 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v19i4.561

- Dubeau, A., Plante, I., & Frenay, M. (2017). Achievement profiles of students in high school vocational training programs. Vocations and Learning, 10(1), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-016-9163-6

- Dung, D. T. (2020). The advantages and disadvantages of virtual learning. IOSR – Journal of Research and Method in Education, 10(3), 45–48. https://doi.org/10.9790/7388-1003054548

- Eldegwy, A., Elsharnouby, T., & Kortam, W. (2018). How sociable is your university brand? An empirical investigation of university social augmenters’ brand equity. International Journal of Educational Management, 32(5), 912–930. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-12-2017-0346

- Elshami, W., Abuzaid, M., & Abdalla, M. E. (2020). Radiography students’ perceptions of peer assisted learning. Radiography, 26(2), e109–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2019.12.002

- Elshami, W., Taha, M. H., Abuzaid, M. M., Saravanan, C., Kawas, S. A., & Abdalla, M. E. (2021). Satisfaction with online learning in the new normal: Perspective of students and faculty at medical and health sciences colleges. Medical Education Online, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2021.1920090

- Elzainy, A., El Sadik, A., & Al Abdulmonem, W. (2020). Experience of e-learning and online assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic at the college of medicine, Qassim University. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 15(6), 456–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2020.09.005

- Ericsson, K. A., Hoffman, R. R., Kozbelt, A., Williams, A. M., Ericsson, K. A., & Collins, H. (2018). The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Gay, L., & Airasian, P. (2005). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and application (8th ed.) ed.). Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Gedik, N., Kiraz, E., & Ozden, M. Y. (2013). Design of a blended learning environment: Considerations and implementation issues. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.6

- Gonzalez, T., de la Rubia, M. A., Hincz, K. P., Comas-Lopez, M., Subirats, L., Fort, S., Sacha, G. M., & Xie, H. (2020). Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PLoS One, 15(10), e0239490. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239490

- Halim, A. (2021). Online instructional strategies for English language learning. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Literature, 6(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.33369/joall.v6i1.12452

- Handelsman, M., Briggs, W., Sullivan, N., & Towler, A. (2005). A measure of college student course engagement. The Journal of Educational Research,98(3), 98(3), 184–192. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.98.3.184-192

- He, J., & Freeman, L. (2009). Are men more technology-oriented than women? The role of gender on the development of general computer self-efficacy of college students. Journal of Information Systems Education, 21(2), 203–212.

- Hollister, B., Nair, P., Hill-Lindsay, S., & Chukoskie, L. (2022). Engagement in online learning: Student attitudes and behavior during COVID-19. Front. Educ, 7, (851019). https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.851019

- Hoq, M. Z. (2020). E-Learning during the period of pandemic (COVID-19) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An empirical study. American Journal of Educational Research, 8(7), 457–464. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-8-7-2

- Hossain, M. (2021). English language teaching through virtual classroom during COVID-19 lockdown in Bangladesh: Challenges and propositions. Journal of English Education and Teaching, 5(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.33369/jeet.5.1.41-60

- Kahn, P. (2014). Theorising student engagement in higher education. British Educational Research Journal, 40(6), 1005–1018.

- Kahu, E. R., & Nelson, K. (2018). Student engagement in the educational interface: Understanding the mechanisms of student success. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344197

- Kanellopoulou, C., & Giannakoulopoulos, A. (2020). Engage and conquer: An online empirical approach into whether intrinsic or extrinsic motivation leads to more enhanced students’ engagement. Creative Education, 11(2), 143–165. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2020.1120

- Kazem, N. A. A. K., & Ashoor, A. S. (2022). A statistical approach and analysis computing based on autoregressive integrated moving averages models to predict COVID-19 outbreak in Iraq. International Journal of Nonlinear Analysis and Applications, 13(1), 1391–1415. http://dx.doi.org/10.22075/ijnaa.2022.5745

- Khabbaz, M., & Najjar, R. (2015). Moodle-based distance language learning strategies: An evaluation of technology in language classroom. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 4(4), 205–210. http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.4p.205

- Khlaif, Z. N., Salha, S., & Kouraichi, B. (2021). Emergency remote learning during COVID-19 crisis: Students’ engagement. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7033–7055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10566-4

- Kissau, S. (2015). Type of instructional delivery and second language teacher candidate performance: Online versus face-to-face. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(6), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.881389

- Korlat, S., Kollmayer, M., Holzer, J., Lüftenegger, M., Pelikan, E. R., Schober, B., & Spiel, C. (2021). Gender differences in digital learning during COVID-19: Competence beliefs, intrinsic value, learning engagement, and perceived teacher support. frontiers in Psychology, 12(12), 637776. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.637776

- Kwon, K., Park, S. J., Shin, S., & Chang, Y. C. (2019). Effects of different types of instructor comments in online discussions. Distance Education, 40(2), 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2019.1602469

- Lawson, M. A., & Lawson, H. A. (2013). New conceptual frameworks for student engagement research, policy, and practice. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 432–479. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313480891

- Lei, H., Cui, Y., & Zhon, W. (2018). Relationships between student engagement and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 46(3), 517–528. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.7054

- Liu, X., He, W., Zhao, L., & Hong, J. (2021). Gender differences in self-regulated online learning during the COVID-19 lockdown. frontiers in Psychology, 12, 752131. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.752131

- Martin, R. (2011). M-learning and student engagement: Factors that support students’ engagement in m-learning (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Murdoch University.

- Martin, F., Wang, C., & Sadaf, A. (2018). Student perception of helpfulness of facilitation strategies that enhance instructor presence, connectedness, engagement and learning in online courses. The Internet and Higher Education, 37, 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2018.01.003

- Marx, A. D., Simonsen, J. C., & Kitchel, T. (2016). Undergraduate student course engagement and the influence of student, contextual, and teacher variables. Journal of Agricultural Education, 57(1), 212–228. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2016.01212

- McGowan, M. (2020). Coronavirus school closures: Dozens of Australian private schools move to online learning. Australia news. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/mar/17/coronavirus-school-closures-dozens-ofaustralian-private-schools-move-to

- Mollenkopf, D., Vu, P., Crow, S., & Black, C. (2017). Does online learning deliver? A comparison of student teacher outcomes from candidates in face-to-face and online program pathways. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 20, 1.

- Myint, K. M., & Khaing, N. N. (2020). Factors influencing academic engagement of university students: A meta-analysis study. Journal of Myanmar Academic Arts and Sciences, 18(9b), 185–199.

- Nguyen, T., Cannata, M., & Miller, J. (2018). Understanding student behavioral engagement: Importance of student interaction with peers and teachers. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2016.1220359

- Onyema, E. M. (2019). Integration of emerging technologies in teaching and learning process in Nigeria: The challenges. Central Asian Journal of Mathematical Theory and Computer Sciences, 1(1), 35–39.

- Oraif, I., & Elyas, T. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on learning: Investigating EFL learners’ engagement in online courses in Saudi Arabia. Education Sciences, 11(99), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11030099

- Orak, S. D., & Al-khresheh, M. (2021). In between 21st century skills and constructivism in ELT: Designing a model derived from a narrative literature review. World Journal of English Language, 11(2), 166–176. https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v11n2p166

- Ortega-Maldonado, A., Llorens, S., Acosta, H., & Coo, C. (2017). Face-to-face vs online: An analysis of profile, learning, performance and satisfaction among post graduate students. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 5(10), 1701–1706. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2017.051005

- Osman, M. E. (2020). Global impact of COVID-19 on education systems: The emergency remote teaching at Sultan Qaboos University. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1802583

- Pham, L., Limbu, Y. B., Bui, T. K., Nguyen, T. H., & Pham, T. H. (2019). Does e-learning service quality influence e-learning student satisfaction and loyalty? Evidence from Vietnam. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(7), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0136-3

- Quin, D. (2017). Longitudinal and contextual associations between teacher–student relationships and student engagement. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 345–387. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316669434

- Quin, D., Hemphill, S., & Heerde, J. (2017). Associations between teaching quality and secondary students’ behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement in school. Social Psychology of Education, 20(4), 807–829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9401-2

- Roberts, D. H., Newman, L. R., & Schwartzstein, R. M. (2012). Twelve Tips for Facilitating Millennials’ Learning. Medical Teacher, 34(4), 274–278. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.613498.

- Sanitchai, P., & Thomas, D. (2018). The relationship of active learning and academic achievement among provincial university students in Thailand. APHEIT International Journal, 7(1), 47–61.

- Sefcik, M. (2013). Intellectual engagement, good grades and doing school. Ed Canada Network. https://www.edcan.ca/articles/intellectual-engagement-good-grades-and-doing-school/

- Sen, S., & Antara, N. (2018). Influencing factors to stay off-campus living by students. International Multidisciplinary Research Journal, 8, 40–44. https://doi.org/10.25081/imrj.2018.v8.3698

- Skinner, E. (2016). Engagement and disaffection as central to processes of motivational resilience and development. In K. R. Wentzel & D. B. Miele (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school. Routledge Handbooks Online.

- Stevens, R., Cronley, T., Eckert, A., Kidd, M., Liondos, N., Newall, G., Pilkington, M., Rekic, B., & Ructtinger, L. (2018). Cultivating student engagement - Part 1. Scan, 37(9), 26–31.

- Thaheem, S. K., Abidin, M. J., Mirza, Q., & Pathan, H. U. (2021). Online teaching benefits and challenges during pandemic COVID-19: A comparative study of Pakistan and Indonesia. Asian Education and Development Studies, 11(21), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-08-2020-0189

- Van Lancker, W., & Parolin, Z. (2020). COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. The Lancet Public Health, 5(5), e243–e244. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(20)

- Van Uden, J. M., Ritzen, H., & Pieters, J. M. (2014). Engaging students: The role of teacher beliefs and interpersonal teacher behavior in fostering student engagement in vocational education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 37, 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.08.005

- Verawardina, U., Asnur, L., Lubis, A. L., Hendriyani, Y., Ramadhani, D., Dewi, I. P., Darni, R., Betri, T. J., Susanti, W., & Sriwahyuni, T. (2020). Reviewing online learning facing the COVID-19 outbreak. International Research Association for Talent Development and Excellence, 12(3s), 385–392.

- Vivek, S. D., Beatty, S. E., Dalela, V., & Morgan, R. M. (2014). A generalised multidimensional scale for measuring customer engagement. The Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 22(4), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP10696679220404

- Wang, M., & Fredricks, J. (2014). The reciprocal links between school engagement, youth problem behaviors, and school dropout during adolescence. Child Development, 85(2), 722–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12138

- Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Fredricks, J. A., Simpkins, S., Roeser, R. W., & Schiefele, U. (2015). Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Development of achievement motivation and engagement (pp. 657–700). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy316

- Willms, J., Friesen, S., & Milton, P. (2009). What did you do in school today? Transforming classrooms through social, academic, and intellectual engagement. Canadian Education Association.

- Wingo, N. P., Ivankova, N. V., & Moss, J. A. (2017). Faculty perceptions about teaching online: Exploring the literature using the technology acceptance model as an organising framework. Online Learning, 21(1), 15–35.https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i1.761

- Wu, E. H., Lin, C. H., Ou, Y. Y., Liu, C. Z., Wang, W. K., & Chao, C. Y. (2020). Advantages and constraints of a Hybrid Model K-12 E-Learning assistant chatbot. IEEE Access, 8(1), 77788–77801. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2988252

- Yassine, F. A., Maaitah, T. A., Maaitah, D. A., & Al-Gasawneh, J. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 on the university education system in Jordan. Journal of South-West Jiaotong University, 57(1), 649–663. https://doi.org/10.35741/.0258-2724.57.1.58

- Younesi, M., & Hawamdeh, Z. M. (2021). Teaching English language online during COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: Views and attitudes. Zeichen Journal, 7(4), 15–21