?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The main purpose of this study was to explore the impact of the Tigray People Liberation Front (TPLF) armed violence on educational institutions, students’ educational attainments, and the role of actors playing in school governance and redirecting the education process. This study was positioned to yield preliminary evidence which can serve as input for concerned bodies when designing intervention programs in the study area that aims to give a response to the spoiled education system brought by the violence. In doing so, a convergent mixed-method research design was used. The study sample was bounded to n = 398 participants. Both qualitative and quantitative data were collected simultaneously, and the analysis was drawn upon both strands in search of patterns. As a result, the following findings were obtained. The TPLF armed violence instigated the destruction of school infrastructures and generated substantial impediments to the supply of schooling. As a result, students’ educational attainment and learning outcomes were significantly lowered as compared to before the violence. As well, students’ dropout rate, out-of-school students’ rate, and related educational wastage have been amplified. This, in turn, requires sound school governance and the active participation of all actors including parents and the local community at large be part of the solutions for those educational issues hampered by the TPLF violence. In the end, possible conclusions and suggestions were made.

1. Introduction

For citizenship and professional practice, education is a fundamental right. Promoting and safeguarding education in general, as well as maintaining educational equity, requires respecting human rights (Singh et al., Citation2021). Education plays a crucial role in protecting people, particularly children, from abuse or neglect. All societies must uphold this right to foster and achieve stable and harmonious international relations and create morally upright citizens for the future. Unfortunately, in nations of armed violence, this right frequently disappears (Manuchehr, Citation2011). Education has long been recognized as a crucial instrument for enhancing both individual and national development, but current disputes in our society pose a threat to the responsibilities that educational systems play in this process (Agbor et al., Citation2022). People frequently attend school because they believe that investing in their education will increase their capacity to generate income in the long run. However, the benefits of education, such as advancements in the economy, society, and culture are impacted by growing warfare (Jones & Naylor, Citation2014).

According to experts in the field such as Justino (Citation2014), armed violence has serious negative impacts on the educational system in three key ways. First, armed violence is linked to the destruction of resources and infrastructure required to keep operating educational systems. Second, violence causes communities to break down as a result of people fleeing violent places, which has an impact on how and where children are educated. Third, when it comes to access to different types of education, violence frequently has distributional and equitable impacts that may prohibit many children from going to school. Indeed, no deep dive into the literature is needed to understand the impact of violence, such as damaged school infrastructure, loss of human capacity, and hazards to the safety and security of children and staff in an environment of active conflict (Omoeva et al., Citation2018). Teachers and children are killed, kidnapped, maimed, or traumatized in schools that are taken over by the armed forces or displaced people (Jones & Naylor, Citation2014). The provision of high-quality education and the restoration of educational systems are severely hampered by a combination of devastation and displacement. Furthermore, armed violence has significant distributional implications that influence access to education inequality and the overall supply of education (Jaiswal, Citation2017).

In literature, it has been demonstrated that armed violence and education can interact in a variety of ways in different parts of the world. For instance, Sub-Saharan Africa is historically the region of the world most impacted by armed violence and is one of the main violence locations having a significant impact on education (Agbor et al., Citation2022). Due to school closings or demolition, as well as the uprooting of the community and the teachers, children and teenagers, miss out on an education (Manuchehr, Citation2011). Every violence has its combination of circumstances and causative variables that lead to its commencement (Omoeva et al., Citation2018). Confrontations are ongoing disputes or frictions between individuals or groups of individuals that have the potential to turn into armed violence (Agbor et al., Citation2022). Human rights abuses, atrocities, a lack of human security and health, unemployment, and almost all industries have been negatively impacted, but education is now one of the most impacted during the ongoing violence (Singh et al., Citation2021). News stories from the North and East part of the Amhara region, Ethiopia, showed how the Tigray People Liberation Front (hereafter, TPLF) armed violence affects children’s access to education. It has proven to be one of the main barriers to the achievement and sustainability of the Education for All goals set by the international community in Jomtien, Thailand, in 1990.

Following the formation of armed groups in Ethiopia like TPLF, which is a left-wing ethnic nationalist group, a banned political party, and the former ruling party of Ethiopia provoked violence several times in the Northern part of Ethiopia. As a result, structural insecurity increased, causing investment to be hindered and public goods to be obstructed, further impoverishing the nation (Spoldi & Spoldi, Citation2021). During the years of violence, children’s education was disrupted and many of them frequently choose not to return to school or do so very reluctantly. This situation hurts the fundamental right to children’s education (Cervantes Duarte & Fernández-Cano, Citation2016).

During the recent TPLF armed violence that took place in the Amhara region and other parts of the country from the beginning of July 2021 to the end of the year, school institutions’ buildings, infrastructures, pedagogical centres and learning resources, as well as other governmental and NGO service providers have been collapsed intentionally. Students, teachers, parents, and the larger community experienced several economic problems and psychosocial traumas. As a result, all pupils in conflict-affected areas endured school closure. More tragically, educational administrative reports disclosed that the invasion of TPLF prevented seventy-five primary schools and five high schools in the Gubalafto district as well as nine primary schools and four high schools in Woldiya town of the Amhara region, Ethiopia, where this study was conducted. A total of 27, 876 (M, 13950 and F, 13926) students (see Table ) and 1,286 (M, 736 and F, 549) primary school teachers in both of these conflict-affected areas were hardly impacted. Parents, schools, and teachers had no choice but to oversee educational activities.

Table 1. Results of students’ education enrolment and educational wastage

Although it appears that the essence, cause, and effects of violence on education have been discussed by several academics with a variety of backgrounds and specializations (E.g., Agbor et al., Citation2022; Franzoni et al., Citation2012; Jones & Naylor, Citation2014; Omoeva et al., Citation2018; Utsumi, Citation2022), particularly, the terrible effects of TPLF armed violence on fundamental and public education institutions and students’ educational attainment have not been fully and exclusively addressed especially in the current study area. Therefore, the main focus of the current study became revealing how the TPLF armed violence impacted public primary education institutions and their service delivery in two conflict-affected areas including Guba Lafto district and Woldiya town of the Amhara region, Ethiopia. Due to the cost constraints of the researchers, the current study was focused on only primary school institutions in the aforementioned areas. In light of this, the following basic research questions are proposed to determine the study’s focus and course. These are:

How has the TPLF armed violence affected the supply of primary schools’ infrastructures and learning facilities?

How has the TPLF armed violence affected the demand for education services?

Does TPLF violence bring a significant impact on students’ educational attainment?

What looks like the status of concerned actors’ role played in re-establish responsive school governance to redirect the devastating effects of schooling?

It is a fact that exploring the impact of armed violence on all spheres of education systems is so broad. Hence, we positioned this study’s focus on revealing only the above-mentioned concerns.

2. Literature review

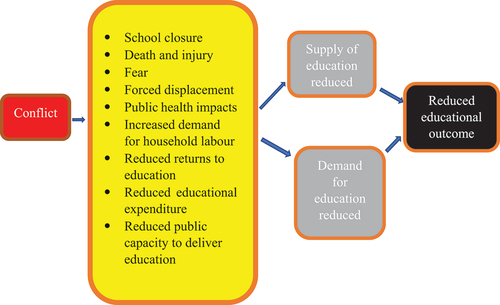

A country’s educational system suffers severe damage from armed violence which can be both direct and indirect, which can affect actors, students, and educational institutions (Utsumi, Citation2022). Jones and Naylor (Citation2014) recognized two ways that armed violence affects the education and learning process. These are: (i) direct effects on education include school closures brought on by targeted attacks, collateral damage, military use of school facilities and use by displaced populations, deaths and injuries among students and teachers, fear of sending children to school, and teacher attendance due to targeted attacks, general insecurity and restricting freedom of movement. (ii) indirect effects on education, such as forced population displacement, public health effects of the conflict that limit access and learning, decreased returns to education, decreased educational expenditure because of global resource constraints and shifting priorities, and decreased public capacity to provide education.

UNESCO’s (Citation2011) publication titled “the hidden crisis: armed conflict and education”, reported several consequences armed violence had on the supply-side and demand side of the educational system. According to the document, violence brought a shortage of supply to the education system such as educational materials and school infrastructures destroyed, both of which are necessary to support purposeful education in schools. It also resulted in the shameful forced evacuation of local communities and student parents’ homes, which causes them to lose their economies and has an impact on how their children are educated and how they send back to attend school even after the violence is over.

On the other hand, demand-side barriers to education such as increasing the financial costs of educational disputes, causing physical and mental health issues for students and teachers, the permanence of fear and uncertainty, and restricting human development practices, all of which further amplify the effects of violence on education’s supply-side (UNESCO, Citation2011). Poverty is a significant barrier to the restoration of education in places impacted by violence. It is well known that purposeful and planned attacks on educational institutions and infrastructure during times of violence cost the sector money. Furthermore, violence exposes the region to (i) serious economic losses of people and institutions, (ii) lack of access to essential supplies for reopening and reorganizing damaged school infrastructure, and (iii) puts families in danger of experiencing extreme poverty and destitution, as a result of which some of them are unable to send their children to school because numerous families could be unable to pay for their children’s tuition, uniforms, books, or school supplies when the schools reopened after the violence.

Armed violence has not only affected the physical structures of educational institutions but also harshly impacts students’ educational achievement and their learning motivation. The body of literature has suggested that raising children’s academic achievement is a top objective for educators, researchers, teachers, and parents at all times (Hibi & Assadi, Citation2021; Hussain et al., Citation2021). However, growing up in a hostile environment is not always easy. Armed conflicts influence millions of children, causing daily life disruptions and atrocities that will haunt them in the future (Cervantes Duarte & Fernández-Cano, Citation2016). Violence can lead to poor learning conditions, a lack of educational resources and psychological traumas for children thereby hindering their ability to study and work hard (Agbor et al., Citation2022; Jones & Naylor, Citation2014). Fewer children enrolling and attending school leads to an increase in educational waste, such as absenteeism, dropout rates, and student repetition rates. Long-term, this affects the returns to education on the labour market by changing the employment opportunities and wages that school-leavers can expect. It has an impact on the private returns to education, also referred to as the real and perceived worth of education concerning family costs. The demand for skilled labour could decline because of a weak economy and infrastructure degradation as a result of violence (Jones & Naylor, Citation2014).

It is crucial to develop strong school governance both during and after the education crisis to redirect its process. According to scholars such as Martina and Anthony (Citation2020) remark, two important educational settings of school governance such as the social environment and the educational environment should be taken in to account by key actors. Them, the family, peer groups, media, other socialization tools including the government and its educational policies, religious organizations, and their contributions to education are all included in the social environment.

On the other hand, the school setting, including extracurricular and co-curricular activities, is referred to as the educational environment. The achievement of students’ educational goals depends critically on each of these contexts. Therefore, analysing the role of responsibilities assigned in terms of decisions and actions is necessary for the governance of education affected by armed violence (Franzoni et al., Citation2012). In this context, school governors play a key role because they can: i) redefine the guidelines for the development of culture, knowledge, and methods to achieve learning output and outcome; ii) encourage and facilitate the resolution of some major issues brought by the violence (such as dropout rates, bullying, and damage to school infrastructure); and iii) deal with the regular measurement and evaluation processes of performance.

Moreover, Franzoni et al. (Citation2012) suggested that the ability to address the need for quality and sustainability of education systems after armed violence is becoming a critical component of the value of sustainable development and social growth, which calls for complex actions. According to them, emphasis should be given to enhancing a mature governance approach that emphasizes the role of network relations with all concerned stakeholders; the rise and balance in value of variety in demand-side and supply-side educational needs expressed by the local community; the ability to respond to the need for quality and sustainability of educational systems after the violence; and increase and balance in value of supply-side of education. Likewise, Hibi and Assadi (Citation2021) in their study urgently call for more adaptable educational programs and techniques that could lead to noticeably higher educational achievement today. The aforementioned school governance after a crisis brought by armed acts of violence is impossible to do without the cooperation, integration, and coordination of parents, schools, and society at large.

Parents and schools are the main players in developing their responsibilities and forms of involvement to restore educational practice after violence is over to generate new and varied activities to relate to one another following the unique educational setting (Lara & Saracostti, Citation2019). As family demands increase, their participation in children’s education extends outside the classroom thereby children perform better in school when their parents are involved in their education (Chen, Citation2021). Therefore, to increase parental involvement in school resiliency from violence-related traumas, schools must have a close relationship with parents. Effective school, family, and community partnerships should be welcomed by school administrators who wish to support students’ academic progress and create a setting where all students, teachers, and families can feel safe, cared for, stimulated, and happy than traumatized the violence (Epstein et al., Citation2002).

In conclusion, the following conceptual framework presented in the Figure displays the consequences of armed violence on educational institutions and their service delivery.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework adapted from Garcia-Coles and Sanchez Danday (Citation2019).

3. Methods and materials

3.1. Study design and setting

A mixed-methods convergent research design (Cohen et al., Citation2007; Creswell, Citation2018) was applied in this study process. To find patterns in the investigation, both qualitative and quantitative data were collected concurrently, and both strands of the analysis were used. The study setting was placed in primary schools affected by the TPLF armed violence found in two conflict-affected areas such as Gubalafto district and Woldiya town found in East Amhara, Ethiopia. This study’s time frame was between January 2022 to June 2022. During this time, the violence has been reverted by the federal government and the study areas were liberated from the invader, the TPLF. All the required tasks needed for the current study were done during the aforementioned timeframe.

3.1.1. The study participants

Three categories of participants such as primary school principals, teachers, and students’ parents have been involved in the current study. The researchers believed that the above-mentioned bodies who have an active role in the school activities can provide the appropriate information needed for the study. Therefore, the target population of the study is all these three groups. In sum, a total of 398 samples were included in the current study. To illustrate moreover:

First, primary school principals (n = 22) were selected through a purposive sampling technique. Since they are needed for this study to obtain in-depth qualitative data, their selection process was purposively bounded from schools where highly affected by the violence.

Second, sample teachers (n = 336) were selected using simple random sampling. Since their population is large in number and known, the sample size was determined by using a statistical method, considering Yamane’s formula, n = where n = sample size, N = population size, and e = precision rate. Although there are several formulas available in the literature and user-friendly software used to determine sample size, we looked up Yamane’s formula because of its easiness enough when the whole population size is known. Considering into account this, a total of 305 teachers at a 95% confidence interval plus, 10% of contingency, which is approximately 31 was determined. Hence a total of 336 teachers (out of a total of 1286 teachers) were selected through simple random sampling.

Third and the last sample category i.e., students’ parents (n = 40) were included in the current study through a purposive sampling technique to obtain qualitative information using focus groups. Previous and current active participation in school activities was set as the main used selection criteria of parent participants as a sample.

3.2. Instrumentation and procedures

Four data-gathering strategies such as questionnaires, interviews, focus group discussions and document analysis were used to elicit pertinent information from the sample respondents about the impacts of the TPLF armed violence on the educational system of the study area. It has been known that collecting data during traumatic and stressful periods instigated by, for instance, violence is questionable. This is because individuals who have experienced trauma may have little space left for information as well their constant state of tension can leave them unable to concentrate and pay attention to provide the needed information during the process of collecting data. Taking into account these issues, we weren’t directly starting to collect the data when the violence is over. Rather we preferred to collect data after when several psycho-social supports and training were given to those who lived in the conflict-affected areas by many NGO and government offices. Those training and support were supposed to help people including the current study’s target participants recovered from the trauma caused by the violence Therefore, the data collection process started a while after the violence was over and much psychological support has been given to them. Details of the instrumentation process are presented as follows:

a) Questionnaire

The questionnaire was initially developed in the English language and contained both open-ended and closed-ended item questions to obtain the response of school teachers (n = 336). The questionnaire was initially written in the English language while considering various literature, most of the items were adapted from UNESCO (Citation2011) and previous studies. Hence, a pool of items was prepared and given to teacher participants to rate their level of agreement about the extent of educational damage as well as the actors’ role play in the education process before and after the violence. The corresponding meaning of the items was then translated into the Amharic language, which is the mother tongue of the respondents, and then reviewed by two language teachers to see if the translated items had the same meaning. Ambiguities in the wording and inappropriate response categories of some questions were simplified to make them obvious and understandable. The questionnaire was, therefore, updated and made ready for distribution.

Before distribution, the questionnaire’s objective and proper completion was briefly explained to the respondents by the researchers. It was intended to disseminate and collect surveys from (n = 336) primary school teachers. Unfortunately, 21 respondents declined to respond and the answers on 7 surveys were rife with mistakes. As a result, both the unreturned and uncleared (n = 28 which represents 8%) questionnaires were eliminated from the study. The 92% return rate was sufficient to move further with the analysis.

3.2.1. Interview

Semi-structured interview guiding questions were prepared and administered to primary school principals (n = 22). The interview questions gave more emphasis on uncovering the extent of schools’ infrastructure damage, the emerging school governance and the role of actors play to curb the devastating effects of the TPLF violence on the education systems. All interviewees gave their complete consent before the interview session began, and they voluntarily agreed for the researchers to utilize a recorder while conducting the interview. To gather complete information during the interview meetings with interviewees, the researcher probed and prodded (Kumar, Citation2011) the interview guide questions. Their response has been captured using an audio recorder.

3.2.2. Focus group discussion

FGD meetings containing ten participants in a single FGD with chosen parents (n = 40) were held to better understand from the perspective of parents the consequences made by the TPLF armed violence on their children’s education and to assess their involvement and determine how they helped the educational system rebound from the TPLF catastrophes. The FGD sessions were conducted in their native tongue (Amharic). As in the interview, the consent of the participants was obtained. Since discussions are forbidden from being recorded because they have no interest to be recorded, the researchers chose and assigned one moderator (an aide of the researcher) to take notes during them.

According to the researcher’s prior expectation, holding three FGD meetings with the same set of questions is sufficient to reach at saturation point for responses (when not hearing anything new anymore). Unfortunately, it was not as expected. To reach at saturation level, therefore, one more additional FGD was carried out.

3.2.3. Document analysis

To confirm, strengthen and support the information gathered from respondents through questionnaires, FGDs, and interviews, document analysis was also used as a data-gathering tool for the current study. As a result, relevant documents from school meetings and proceedings, records of supervision, registries of student academic achievement and enrolment, and different photo galleries were scrutinized. The student academic achievements are used to compare student learning outcome differences before and after the violence. Student enrolment and educational wastage (such as out-of-school and drop-out-school students) rates are also compared to examine student dropout trends before and after the violence. When analysing the already-existing documents, the researchers focused primarily on the documents’ applicability and relevance to the topics under investigation. The researchers were able to use it only when the sources were deemed trustworthy and appropriate to the study focus.

3.3. Data analysis method

Two techniques, thematic analysis (Creswell, Citation2018) and both descriptive and inferential statistical analyses (Kumar, Citation2011) were used in this study to analyse both qualitative and quantitative data respectively. This study answered the planned basic research questions based on the data they need. Hence as seen on page 4 of this paper, the two basic research questions mentioned in numbers (i) and (ii) were addressed mostly in qualitative data using thematic analysis with the support of some quantitative data. The remaining two questions mentioned in numbers (iii) and (iv) were answered quantitatively through descriptive and inferential statistics techniques with the support of some qualitative data. The initial step in the analysis of qualitative data was to translate the data (Creswell, Citation2018) from Amharic into English. Then, data were transcribed, arranged into portions that could be searched for later, and sorted into themes that made sense. To help readers better understand the concepts, several key themes were divided into sub-themes.

Additionally, descriptive and inferential statistical techniques such as frequency, percentage, independent samples t-test and paired samples t-test were used to analyse the quantitative data. The percentages are used to show differences in student enrolment rates before and after the war thereby indicating student dropout. The paired sample t-test is run on data retrieved from student registry archives to show differences in the academic achievement of the same group of students before and after the war. Finally, the results were condensed into a more comprehensible explanation.

3.4. Ethical considerations

In light of the fact, scholars have noted that every stage of research raises an ethical dilemma faced specifically in educational research, which can be exceedingly complicated and regularly throw researchers into moral predicaments which may look quite absurd (Cohen et al., Citation2007). Thus, the following ethical issues were considered: (i) The researchers politely asked individual participants for their consent to participate in the study. A letter of reference from the Woldia University Research and Development Office outlining the purpose of the study and the cooperation needed from them was presented. (ii) Since conducting violence was very much ethnically sensitive, the researchers employed the methodological guidelines and orientations developed by Woldia University Research and Development Office on January 2022 and the directive of the University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) that guides how to keep balance when studying the impact of the TPLF armed violence on education in general and our case suite in particular.

Moreover, the researchers have carefully planned, carried out, and reported on each study activity while adhering to the required guidelines for the research format and ethical standards. Additionally, the researchers gave all of the effort to properly recognize and acknowledge all used material and records. (iii) To protect study participants’ privacy, information collected from them was kept confidential and only available to the researcher. The confidentiality of every respondent was maintained throughout reporting of gathered and analysed data by representing their names with codes (for instance, school principals coded as P1, P2 … . P22 and participants in FGD as FGD1, … FGD4).

4. Results

The impact of TPLF armed violence on the educational system in conflict-affected areas is highlighted in this part with a focus on primary schools found in Gubalafto district and Woldiya town. In terms of the study’s primary objective, this section concentrated on evaluating the degree to which school infrastructures, learning environments, and students’ educational attainment have been impacted by the TPLF violence and outlining how parents, school administrators, and the local community are involved in school activities to enhance the hampered educational system after the TPLF violence was over. To show more about this devastating scenario, we determined how the TPLF battle affected school infrastructures and learning facilities, delivery of educational services, and students’ educational outcomes including school enrolment rate, attendance rates, and academic performance. Furthermore, the expected actors’ role played in school governance and redirecting the education process was scrutinized:

4.1. The effect of TPLF armed violence on school infrastructures and learning facilities

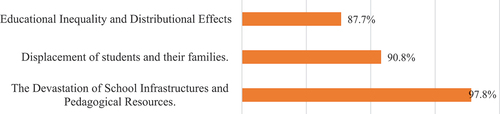

According to data gathered from study participants, the TPLF violence brought substantial negative effects on the delivery of education in conflict-affected areas, particularly in three key assortments. First, the TPLF armed violence destroyed educational materials and school infrastructure, both of which are necessary to maintain functional schools. Second, the violence brought shame to surrounding communities, forcing students’ parents to flee their homes and, as a result, to lose their jobs. Third, the TPLF had brought inequitable effects on human resource development, as it prevented teachers and students from continuing their studies and professional development programs. The following Figure illustrates more about this issue:

4.1.1. The devastation of school infrastructures and pedagogical resources

The destruction of school facilities is one of the most obvious effects of armed violent. Others include the inability of the government to provide educational products and services, and a lack of funding or the diverting of educational funds to military projects (UNESCO, Citation2011) are the following results from catastrophic violence. According to the evidence from various segments of respondents, TPLF violence has a typical influence on school instructors, and pupils, (FGD1 & FGD2). Likewise, as observed in Figure , a large number of respondents, 97.8%, revealed the TPLF fighters devastated school infrastructure and pedagogical resource centres intentionally. Figure shows a sample of damage brought by this terrorist group, which supports the participants’ opinion.

Figure 3. Examples of damaged classroom and students’ book store (picture: Amhara media corporation).

As observed in Figure , a large volume of school infrastructures and educational facilities were damaged when the TPLF armed group stayed in the conflict-affected areas. The left is a damaged classroom building and its roof, and the right side is a spoiled room storing students’ text books.

Speaking more, an interview with the school principal disclosed the situation as follows:

... the TPLF armed groups used schools as military bases and camps, they harmed the school infrastructures, buildings, and other resources used for learning. For cooking, they made use of and burned student seating chairs and tables. Due to their storage of warriors’ dead and injured, the classrooms were covered in blood. While they were here, they wasted textbooks, lab materials, and students’ data. As a result, even though the area was freed from the TPLF now, it is extremely challenging to resume teaching and learning (P1).

Additional interviews with other school administrators stated that “children have not been able to locate in a proper learning environment and this makes their learning very difficult due to the destruction of school buildings, classrooms, and chairs” (P15). As well, “the TPLF violence has had a significant negative impact on other educational line-ups. Students lost access to a variety of textbooks, library volumes, laboratory works, etc.” (P9).

From these perspectives, it is clear that the TPLF violence gravely harmed not only the schools’ facilities and services but also the morale of both instructors and pupils. The restart and continuation of teaching and learning activities were greatly laden by this problem.

4.1.2. Displacement of students and their families

It is well known that when the TPLF controlled the areas, education suffered. The delivery of education was considerably disrupted at this time due to the relocation of students’ families and occasionally majority of the community was displaced into other regions of the nation. Regarding this, 90.8% of respondents seen in Figure , revealed that children and their families have been forced to displace their habitats due to the violence caused by TPLF. Although schooling was possible, “for the majority of them, this was normally inconceivable because they are intending to get back to their home soon” (a respondent said in FGD3).

During their displacement, they have been under a lot of financial strain. According to information gathered from multiple interview sessions, when schools reopened after the violence, some families were unable to pay to enrol their children in school and cover the costs of uniforms, textbooks, school supplies, and other expenses (P1, P2, P7-P13 & P19). A conversation with FGD2 supported this result as in certain circumstances children cannot attend school because their employment is necessary to contribute to the family’s income in addition to barriers to the availability of education when they returned from being displaced.

4.1.3. Educational inequality and distributional effects

The TPLF violence created significant distributional effects on schooling along geographical dimensions, according to FGD and interview meetings (FGD1, P7, P15 & P16). Regarding this, 87.7% of respondents as seen in Figure , confirmed the educational inequality and distributional effects created by the TPLF on their educational practice and professional development. This led to discrepancies in educational access for both students and teachers, in addition to the overall supply of education. Students were not allowed to attend school during the violence. Similarly, to this, teachers lost the possibility of renewing and upgrading their knowledge, including attending postgraduate training, summer education, and extension programs. But others who are outside the area of violence had such chances (P2 & P8). This may surely exacerbate educational and economic disparities among teachers in various geographic areas who have even the same position before the violence.

4.2. The impact of TPLF violence on education demand

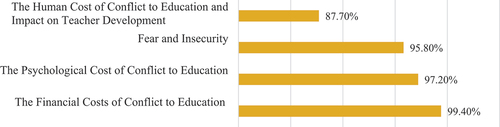

The TPLF violence had negative inducements on education demand in addition to the supply-side effects because of a variety of factors, such as increasing the cost of violence on education, negative effects on students’ and teachers’ physical and mental health, the persistence of fear and insecurity, and restricting human development practices. To illustrate this concern, respondents’ responses was presented in the following Figure .

4.2.1. The financial costs of violence to education: increases poverty

Similar sentiments were seen, which were articulated in a global report by UNESCO (Citation2011) regarding the education crisis brought on by violence. Likewise, the TPLF violence caused the current study areas’ people and institutions to suffer serious economic losses and a lack of access to necessary supplies to reopen and reorganize the damaged school infrastructures (P3 & P17). As well, the violence put families in danger of experiencing extreme poverty and destitution because of which some of them are unable to send their children to school. As presented in Figure , this result is confirmed by 99.4% of respondents that the TPLF violence exacerbated the financial cost of violence to education in the areas.

Furthermore, these issues were discussed in focus group discussions with school principals and parents (FGD2 & FGD3). Since students’ absence from school may severely impact their acquisition of knowledge, these impacts have long-term ramifications for students and their families, in addition to short-term ones. Also, according to the participant (P2)‘s testimony, “several heads of households who worked jobs other than farming were unable to maintain their families because they were fired from their prior positions. Their kids were consequently compelled to quit school”. Related standpoints revealed in an interview with P11, “even though there are many reasons for students to withdraw from school, one is that they are withdrawn to cope with the increased household workload because some of them lost their parents during either at the violence battle or deliberate killing by the TPLF armed groups.”

Therefore, in all sessions, it was emphasized that kid employment as a substitute for what their parents do for the family is a major barrier to children continuing their education.

Additional, Interviews with other school principals exposed that:

… in some cases, this violence changed the distribution of family labour and income conditions. For example, the cereals on their land and home have been taken by the TPLF armed groups. Working parents have been either injured or died. In this circumstance how could children come to education? Who fulfils their basic educational needs? No one else … … Due to these, some students have been obligated to withdraw from school to give their effort to the household (P9).

This indicates a significant number of people were disposed to an economic shock. Even after the violence was over, some of them find themselves unable to cover the costs of their children’s education, including uniforms, various school fees, extracurricular guides, and other educational resources.

4.2.2. The psychological cost of violence to education

Children’s psychological and mental illnesses were another effect of the armed violence both during and after it ended. As indicated in Figure above, 97.2% of respondents confirmed this fact. Similarly, multiple open-ended item responses assured that several obstacles were made by TPLF in which children experience post-traumatic symptoms when returning to school which limits their learning readiness. Interviews with school administrators revealed that “schools including Hara primary and high schools, Gubarja primary school, and Doro Gibr primary school were used as a place of the mass grave (P15) during the violence time by the TPLF forces (see the following Figure ). Due to this, students are still disturbed to attend their education, although mass graves have been removed from the aforementioned campuses.

Additionally, a response from P11 unveiled that:

the TPLF violence brought a devastating effect on students’ health since they have witnessed numerous instances of individuals being shot in front of them, their sisters and moms being raped as they watch, and schools being demolished, pupils have been exposed to various sorts of mental illness and sadness, which has had an overwhelming impact on their health. Due to these factors, kids experienced extreme trauma and are more prone to experience depression; as a result, they are less prepared to learn and less able to study, which causes them to perform below expectations.

Also, P22 added that:

Students exhibit a variety of health-related problem signs because of the violence and their poor mental health. They start to lose hope, experience anxiety, have unsteady learning, and have a higher chance of dropping out. Their level of assurance has dropped. Furthermore, the lack of basic amenities such as food, water, and health care put the health of not only students but also the majority of the population at risk. This makes it worsens students to drop out of school.

These psychological conditions all result in behavioural conditions. This, in turn, could make it more difficult for teachers to oversee classroom management and student attendance at learning centres.

4.2.3. Fear and insecurity: its effect on students’ return to education

Feelings of dread and insecurity are linked to other difficulties that pupils returning to school in conflict-affected communities must overcome. The witness of the 95.8% of participants in Figure , provided proof that parents, teachers, and children share a fear that the violence may revive. When students hear gunshots either for joy or sadness in their locality, they feel like the TPLF armed group comes back. Additionally, in an interview with P1, “kids are terrible when they see armament vehicles; they assume that the defence force is retreating from the area and that violence will come again”. In a similar vein, several school administrators during the interview sessions stated that “children are not fully attending their education due to the dread of violence which may revive as they heard from their big brothers, sisters, and parents” (P12). Also, due to widespread media reports of the violence, “parents have not been able to settle their children down from dread of another violence” (a respondent in FGD3). Moreover, from another interview with a school principal who is a parent at the same noticed by saying this:

Students are terrified that another violence would break out when they see the destruction left by the TPLF on the school grounds. They label everyone with a weapon, including armed members of the local militia, as a killer and robber of the TPLF’s armed warriors. They were afraid that violence was about to break out, as they heard and saw various planes and helicopters flying over the sky. They relate this incidence to the regularity with which helicopters flew every day during the previous violence period. They are consequently displaying a great lot of fear. Due to this, it is very difficult for them to stay in school (P5).

These results indicate fear sentiments of the pupils and partly of the parents persist for some time. Children’s mental health and cognitive abilities are negatively affected by these conditions, resulting in increased anxiety and insecurity. In turn, this has an impact on students’ school attendance and performance as well as on future human development.

4.2.4. The human cost of violence to education: impact on teacher development

Teacher development is an early casualty of the violence that has been blocked and unable to maintain pre-service and in-service training programs. Interview with P13 stated that:

In terms of the advantage and advancement of teachers, violence had a significant effect on them. The government administration at all levels diverted all budget codes, except for monthly salaries, to battling the TPLF invader. This created budget limitations for other services. As a result of budget restrictions, some teachers were unable to take advantage of numerous educational possibilities to advance their careers.

This idea was supported by 87.7% of respondents (see Figure ). They unveiled that the violence cost both public and private school teachers’ time and money. They have suffered since the TPLF prevented them from participating in further educational programs like summer, PGDT, and other in-service training opportunities. As a result, they experience an economic crisis, which causes instructors to worry more and more about their daily lives and may cause them to lose interest in education more than what they do for a living.

4.3. Impact of TPLF violence on students’ education enrolment and learning outcome

Numerous pieces of data from schools and education administration offices show that the relationship between violence and education is very context-dependent and that it can change quickly when violence arises or is resolved. Violence can force students, parents and guardians into poverty, make it difficult for them to succeed in school and hurt their behaviour, which can result in expulsion from educational institutions. Moreover, out-of-school students and drop-out students have been aggravated as compared with other none conflict-affected areas which is another indicator of educational inequality and distributional effects. Table displays front-by-front detail about how the violence boosted educational wastage such as out-of-school and dropout students’ rates as compared to before and after the TPLF violence.

As seen in Table , the enrolment rate especially the registered students to attend their education after the violence was lower (75.5%) than before the violence (84,7%). It implies about one-fourth (24.5%) out of the total expected enrolment was absent from class after the violence. Although several reasons are contributing to students’ decision to stop attending school, the violence either directly or indirectly increased the number of pupils who do so. The TPLF violence exacerbates out-of-school students’ rate (24.5%) as compared with data observed before the violence (15.5%). This result shows a rise in the out-of-school students’ rate by 9% in the 2021/22 academic year, which is after the TPLF violence than before.

A similar continuum was seen in students’ dropout rates. As seen in Table , students are much more likely to drop out of school after the violence (2.3%) than before violence (1.3%). This discovery highlighted the negative causal consequences of TPLF armed violence exposure on how it harmfully affects children’s time that would have been spent in school and their ability to grow academically. These effects could have a significant impact on the future life prospects of the affected children, including their ability to access the labour market, their ability to earn an adult living, and their health outcomes which may exacerbate the long-term risks associated with the onset or resurgence of violent.

More than the comparisons of out-of-school and dropout rates, the current study compared students’ learning outcomes to scrutinize whether it was significantly impacted by the violence (see Tables ). Students’ learning outcome was obtained from education registries. All students’ learning outcome registered in the office before and after the violence was considered as two sets for comparison.

Table 2. Results of students’ learning outcome before and after the TPLF violence

Table 3. Comparison of students’ learning outcome before and after the TPLF violence

Taking into account the numbers of students’ learning outcome scores in two groups i.e., before and after the violence (see Table ), an independent samples t-test was calculated to compare mean scores of students’ learning outcomes whether significantly affected by the TPLF violence or not. Before going ahead with the analysis, Levene’s test of homogeneity of variance was performed to test whether the error variance of learning outcomes is equal across groups (see Table ). As assessed by Levene’s test for equality of variances, the variances were found homogeneous (F (1.411), p > .05), indicating the assumption was achieved for further analysis.

As seen in Table , a significant difference in the mean score of students’ learning outcomes was found between before and after the violence (t (56879) = 389.653, p < .0.001). The mean score of students’ learning outcomes observed after the TPLF violence (M = 60.084, SD = 5.690) was very lower than before the violence (M = 78.814, SD = 5.759) academic year. The effect sizes of these two mean scores’ differences are shown by Cohen’s d = 3.271, indicating the violence brought negatively a significant very large effect on students’ learning outcomes.

4.4. Responsive school governance: roles of key actors to curb education from crisis

Creating sound school governance is very urgent to make a responsible decision when a crisis happens in education systems like during the TPLF violence. Hence, it calls concerned institutions and dynamics such as district education officials, school leaders, parents, and local community leaders to play their roles effectively and be responsible to determine priorities as well as redirecting the hindered education process.

4.4.1. The role of district education offices

It was supposed that some educational services could have been provided to the injured schools by the district education office and zonal education department in collaboration with the Amhara regional education bureau. Responses from the interview with participants identified far-apart perspectives. For instance, an interview with P3 disclosed that “due to the restrictions brought on by TPLF, schools cannot offer essential services that children and the community require. Concerned government offices didn’t provide us with much support at all. I believe that the repercussions of this violence are long overdue.”

From the additional interview, it was disclosed that:

Our prior experience shows that building an educational institution requires a lot of time due to resource constraints and a lack of commitment. Unfortunately, now most schools have been destroyed and need a quick repair. I think it will be very difficult to give a fast response because our previous experience didn’t show well in giving fast decisions not only during the crisis but also the normal tasks. It will be necessary for all stakeholders to show more than just participation to deliver the necessary resources on time (P21).

This finding indicates efforts to re-establish damaged schools are at the substandard level. During further interviews with P5 and P6, they specifically criticized the zonal and district education offices’ supportive role to replace damaged teaching infrastructures, including staff offices, classrooms, and teaching resources (such as student-set tables, chalkboards, and blackboards). Unfortunately, even if schools received some materials from the aforementioned offices, they did have not an immediate role to resume teaching duties. Politicized support predominates.

Based on empirical data from the participants, it can be reasonable to conclude that most schools did not get enough demand-driven support. Poor students never have enough books and pens (P16, P18 & P20). The district and zonal education administrations are still supposed to provide a lot of sustenance despite nothing having been supplied yet. This could be due to offices’ limited resources as a result of their status as TPLF violence victims too. To reenergize subsidiary processes and planning services with new capacity in some schools, the regional and zonal education departments are currently called upon to work with NGOs. Hence it would be better if context-damaged-based assistance becomes the most essential way to restart education from the crisis in the violence-affected areas.

4.4.2. The role of school-level actors

The majority of respondents revealed that some gaps in the schools’ other administrative activities had emerged as a result of the principals’ increased emphasis on gathering students in one location, treating their post-traumatic distress, and attending to their urgent educational needs. Additionally, it has been theorized from numerous FGD meetings that the integration of some schools’ principals with local authorities is becoming more challenging than it was before the TPLF violence. The relationship may occasionally be founded on face-to-face interactions with individuals who have strong ties to the schools.

4.4.3. The role of parents

Drawing inspiration from Barrera-Osorio et al (Citation2021) work on parental involvement in education, this study examined parental and community involvement and their role played in school activities to address the catastrophic effects of the TPLF violence. Before addressing this concern, first, it is important to compare their participation and the role played before and after the TPLF violence. Data on nine items were presented to teachers to rate their agreement about what looks like the extent of parents’ participation and their role play in education activities before and after the TPLF violence. Their response was determined using paired samples t-test. The result was presented in the following Tables .

Table 4. Results of parents’ involvement in education before and after TPLF Violence

Table 5. Results of paired mean comparison of parental involvement in education activity

Paired samples t-test was calculated to determine whether there is a significant difference in parents’ participation in educational activities. As seen in Table , a significant mean score difference in parents’ role in the education activities was found between the time before the TPLF violence and after the violence (t (307) = 47.762, p < .0.001). As seen in Table , the mean score of participants’ judgement about parents’ involvement observed after the TPLF violence (M = 21.76, SD = 3.446) was very lower than before the violence (M = 34.98, SD = 3.440) time. The effect seizes of these two mean scores’ difference was Cohen’s d = 2.721, indicating the TPLF violence brought negatively a significant very large effect on parents’ role played in school to support students’ learning after the TPLF violence.

Further qualitative data shows parents’ involvement in some school activities seems good. They were involved in repairing and rebuilding damaged school buildings and infrastructure after the TPLF violence was over. However, interview data obtained from P9 and P17 show that other critical school activities which demand their unreserved effort were found at a sub-standard level and even the worst thing, a small portion of the community members participated in the looting of education sector resources. This practice exacerbates the existing problem.

According to abridged ideas obtained from FGD and interview sessions (FGD2, FGD4, P17, P19), despite believing that they were actively involved in the process of restoring damaged schools, their involvement is currently hampered by two major issues. The first is that they still experience anxiety and fear because of the ongoing rumour that the TPLF wants to renew the battle, they have lessened their involvement in school projects because they believe that even if the school is restored today, the violence would continue and demolish it once more. The second is that their financial position made it difficult for them to take part actively in supporting education activities in schools. The majority of parents do little to improve their children’s academic achievement. These two concerns threaten to sustain parents’ role played in the process of re-establishing and enhancing schooling services.

4.4.4. The role of local community leaders

According to the information collected, the relationship established between the local community and the schools has two aspects:

First, in an interview with school principals, they agreed with the notion that after the violence, schools are only partially connected with the local population. When the area was retaken from the TPLF, there is considerable integration between schools and the nearby villages. The neighbourhood was determined to repair the school facilities as soon as they could. However, this circumstance is not predictable in advance (P1 & P5). Also, the majority of attendees at the meeting with FGD2 concurred that a positive relationship was created while the area was freed from the TPLF, but they were also unsatisfied with the current state of affairs. From the discussion with participants described previously, it is conceivable to imagine how the local community and the school will actively work together to re-establish the school’s services after the area is liberated from the TPLF armed group. However, due to a new possibility that the battle will revive and undo their accomplishments, such unity has now begun to dissolve.

Second, discussions with FGD1 and FGD4 pronounced that elementary schools are run by the local community in this study area, so the community wasted their unreserved time, energy, and money on the schools. Compared to last year, now the TPLF violence has weakened the community’s economy. As a result, community participation has diminished. Community funding for schools is becoming very low. Because the community is now waiting for others’ help, not helping schools.

5. Discussion

The current study results show that TPLF violence had negative effects on children’s education instigated by the destruction of schools’ physical facilities and educational resources, restriction of financial resources, and escalation of educational disparities. This finding is in line with earlier research findings. Previous research has noted that when the eco-environment changes from favourable to hostile due to a man-made or natural disaster, such as violence, the supply of education is called into question (Singh et al., Citation2021). For instance, Frounfelker et al. (Citation2019) conclude educational access is frequently hindered, and school infrastructures and educational resources are lost during violent times because places are destabilized. As well, Mayai (Citation2022) and Spoldi and Spoldi (Citation2021) acknowledged educational institutions struggled to fulfil their roles as places of instruction, turned into bases for armed groups, and were either destroyed or shut down. In this circumstance, continuing students’ education is very difficult.

The other result of this study shows students often skip important school years or enrol in grades that are below what would normally be considered “age-appropriate” due to the widespread destruction of educational facilities. This demonstrated the detrimental causal effect of violence exposure in terms of reducing the number of school years spent by kids and limiting their ability to advance through the grades. Previous study findings remarked that violence can undermine the educational process in numerous ways, which may be the cause of this in some cases (Mayai, Citation2022). The TPLF combat had a direct or indirect impact on the reduction in students’ enrolment and the risen in out-of-school children due to three reasons despite the availability of other reasons why kids leave school. First, schools in violence zones are more likely to be destroyed. Second, whether or not the new location includes a school, parents are likely to remove their kids from a school in a dangerous neighbourhood and relocate them. Third, those who are moved lose their income, which has a detrimental impact on their ability to afford the education of their kids.

This study also shows large numbers of kids are not going to school because they are needed to work to support the family who was impacted by the TPLF violence. Since the exposed kids’ schooling declined, it stands to reason that their employment in later life did as well (Bharati, Citation2021). According to UNESCO (Citation2011) report, these effects result in lost investments and expenses to the education sector because efforts to restore and replace school infrastructures will shift funds from other areas. Since investing in education typically yields positive returns, this decreased investment will eventually have a more significant effect by lowering national income. Furthermore, children who have less access to school miss out on the opportunity to develop their human capital, which constitutes a lost investment. Because of this, scholars like Cervantes Duarte and Fernández-Cano (Citation2016) noted one key factor preventing children from returning to school after violence is, the poor financial situation of certain families which forces children to look for immediate jobs. Children’s educational rights have been gravely infringed over the years when schools have been closed. Public spending on education decreases to the absolute minimum when governments enter civil violence to help pay for the costs of the fight, according to authors (Spoldi & Spoldi, Citation2021).

The current investigation uncovered the post-traumatic symptoms caused by the TPLF battle that students experienced when returning to school made worse their learning. Children’s psychological and mental illnesses were another effect of the TPLF armed violence, both while and after it ended. According to the literature, it is known that necessities such as psychologically supportive environments, educational and employment opportunities, as well as other resources that foster optimal psychosocial development and mental health, are regularly denied to children during violence (Frounfelker et al., Citation2019). Young people may become frustrated and afraid of the future as a result of terrible experiences in a violence or violence setting and the psychological and social pressures they faced there (Alotaibi, Citation2021). Therefore, as pioneered by Frounfelker et al. (Citation2019), removing the psychological and structural obstacles to such interaction has the potential to improve the community and individual well-being. It’s important to involve kids and teenagers by boosting their self-efficacy, sense of worth, and capacity to be respected members of their community.

According to the study’s findings, students are not completely participating in their studies due to their parents’ and children’s concerns that violence would break out again. Parents’ and students’ perceptions of fear may last for a while. Children’s mental health and cognitive abilities will be negatively affected by this condition, resulting in increased anxiety and insecurity. In turn, this has an impact on future human development as well as school attendance and performance. Working in anxious, scared circumstances is not conducive to any greatest performance. A similar study found that structural insecurity is a significant contributor to poverty and health problems, particularly those that affect children and vulnerable groups (Spoldi & Spoldi, Citation2021). Agbor et al. (Citation2022). Hence, paying close attention to what occurs in the classroom after times of violence since the way activities are handled in the classroom can worsen the long-term impacts. When teachers are afraid and do not feel safe, they unintentionally project their fears onto the students.

Every concerned actor’s role and responsibility must be placed at the centre to minimize all challenging consequences which are brought by the TPLF armed violence. This study finding identifies two major factors that affect stakeholders’ efforts to support schools and to mitigate all of the adverse effects in the aftermath of the TPLF violence. First, it is plausible to conclude that most schools do not receive adequate demand-driven support. To reactivate subsidiary processes with new capacity in some schools, the region, and zone education departments has to call upon to work with NGOs and CBOs. Second, since the elementary schools are operated by the local community, community resilience in the education sector can be characterized as efforts to maintain or enhance the educational environment in a time of turmoil (Utsumi, Citation2022). Given that the TPLF fight has hurt the local community’s economy compared to last year, community participation decreased as a result. School funding from the community is rapidly declining. Because instead of assisting schools, the community is currently waiting for assistance. Therefore, it would be preferable if context-damaged-based aid took on a central role in helping violence-affected areas to restart and maintain education in the wake of the crisis.

According to the corpus of literature cited by Agbor et al. (Citation2022), learning is subpar because instruction is subpar, and going back to school while violence is going on is impractical. To ensure that conditions are improved and schools carry out the duty for which they are permitted to operate, more work needs to be done. The only long-term solution to this problem is to end the fight, even though the impacts may last for a very long period. So, it makes sense to involve regional organizations that have been established in areas where common activities are carried out. In any event, partnerships have to be long-lasting. For instance, it is essential to establish a permanent committee and actively involve influential community members who may provide input to school representatives and stakeholders. Local school administrators frequently consult with zone and regional education offices to make decisions regarding educational matters such as school improvement plans during the crisis, re-establishing school infrastructure with the aid of the local community, maintaining damaged school infrastructures and resources, helping helpless students because their parents or guardians died in battle, etc. If this were done, the number of student dropouts might be decreased.

In previous studies, it was confirmed that the participation of parents and the community in school activities promote resilience which may signify different things depending on how their contributions are evaluated (Utsumi, Citation2022). Their participation helps to prevent a decline in the enrolment rate after the violence because individual community members are determined to band together as they work to maintain their children’s education. However, the current study findings showed that efforts to encourage parents and community people to engage in school decision-making and to attend parent association meetings were falling short. A similar study conducted by Urii and Bunijevac (2017) listed several obstacles to such results, like time constraints, access issues, financial constraints, lack of knowledge, feelings of inadequacy, lack of school experience, or being busy with necessities, that can deter parents from contacting schools. Therefore. the school principal, who acts as the organization’s legal agent, is in charge of the school’s overall operations by coming together all actors including the parents. The principal may advocate activities intended to ensure the standard of working out educational deals and has independent authority over building a strong partnership with student parents in the schooling services.

6. Conclusion

This study focused on the impact of the TPLF armed violence on primary schools in the Gubalafto district and Woldia town of the north Wollo zone. After a half year of the TPLF armed violence, several devastating consequences were put on the education systems in the conflict-affected areas. School infrastructures have been demolished. Additionally, the demand for education was negatively challenged due to the economic and social structures of families and created ongoing insecurity. These problems brought a significant diminution in students’ educational attainments and amplified educational wastage. To tackle this challenge, the effort and contribution played by school governing bodies in all aspects of schoolwork have shown a priceless return in the process of resilience education. This may be due to a lack of concern about the current crisis in school leadership and education. Therefore, government bodies should walk out of carelessness towards the TPLF violence to give rise to serious damage to the schools. Better school governance must be formed to curb the devastating effect of TPLF violence on education by enhancing the commitment of government bodies, the local community, parents, and teachers. Moreover, the government’s role of delivering all school-needed materials and guarantying the security system should be in place before any other activities. Since the current study was limited to seeing the effects caused by TPLF violence on the supply and demands of education, students’ educational attainment and the status of concerned actors’ role to resilience the education process, other impacts such as the psychological, social and economic dimensions of the education system caused by the TPLF violence weren’t addressed. This may make the study not representative in its coverage of the TPLF violence impact on the overall education sector due to only space constraints. Therefore, detailed examination and further studies are needed to take remedial action for the conflict-affected areas.

7. Implications and recommendations of the study

The current study attempted to examine the impact of the TPLF armed violence on public education. Therefore, the study’s results may have several implications and values for the concerned. Hence, the authors of this study suggested all concerned stakeholders use this study’s findings in their job because it may have the following values:

The study result serves as a wake-up call for all concerned stakeholders and suggests working together in coordination to minimize the adverse effect of the TPLF violence put on education and to push forward the school activity which needs a collective effort.

The current study results help education experts, school supervisors, and teachers to adapt some practices regarding how to apply sound school governance to improve the painfully affected education institutions and students’ educational attainment by the TPLF.

The study discusses how to lead and govern education during the crisis. This in turn can serve for concerned stakeholders as a benchmark for the improvement of school programs in terms of the required school activities to redirect and resilience educational practices and students’ learning in the aftermath of violence.

The study also serves as a stepping-stone for research institutions, professionals, and researchers who need further study in the field and related issues. Therefore, it suggested the concerned bodies use this study as a preliminary report when dealing with similar issues.

8. Limitations and suggestions for future study

This study was limited to seeing only the impact of TPLF violence on public education by drawing the sample from selected primary schools found in two violence-affected areas of East Amhara such as Gubalafto district and Woldiya town. Because of the researchers’ cost constraint, it was impossible to cover to what extent all educational functions have been impacted by the violence at a time. Therefore, only the impact of TPLF violence on public education perspectives from the supply-side, demand-side, and school governance observed in primary schools were the main coverage. Thus, other issues were not included. Therefore, the authors suggest scholars and research institutions to further explore not only the overall educational consequences brought by the TPLF violence but also the social, economic, political, and other aspects.

Abbreviations

| CBO | = | Community-Based Organizations |

| FGD | = | Focus Group Discussion |

| NGO | = | Non-Governmental Organizations |

| PGDT | = | Post Graduate Diploma in Teaching |

| TPLF | = | Tigray People Liberation Front |

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate and acknowledge Woldia University Research and Development Office for granting this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yalalem Assefa

Yalalem Assefa, is an Assistant Professor, Department of Adult Education and Community Development, Woldia University, Ethiopia. Currently, he is a doctoral student of Educational Policy and Leadership at Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. His research interest includes adult education, lifelong learning, indigenous knowledge, educational policy and leadership, and educational technology.

Shouket Ahmad Tilwani

Shouket Ahmad Tilwani is an Assistant Professor, Department of English, College of Science and Humanities, Al-Kharj, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, 11942, Saudi Arabia. His research interest includes English Literature, World Literature, New Literatures in English, Postcolonial Literature, Contemporary Literature, Oriental Literature, Discourse Analysis.

Bekalu Tadesse Moges

Bekalu Tadesse Moges is an Assistant Professor, Department of Pedagogical Science, Woldia University, Ethiopia. Currently, he is a doctoral student of Educational Policy and Leadership at Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. His research interest includes quality education, technologies in education, educational research, educational policy and leadership.

References

- Agbor, M. N., Etta, M. A., & Etonde, H. M. (2022). Effects of armed conflicts on teaching and learning: Perspectives of secondary school teachers in Cameroon. Journal of Education, 2022(86), 164–25. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i86a09

- Alotaibi, N. M. (2021). Future Anxiety Among Young People Affected by War and Armed Conflict: Indicators of social work practice. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(729811), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.729811

- Barrera-Osorio, F., Gertler, P., Nakajima, N., Patrinos, H. A., & Barrera-Osorio, F. (2021). Promoting Parental Involvement in Schools : Evidence from Two Randomized Experiments. 21.

- Bharati, T. (2021). The Long Shadow of the Kargil War: The Effect of Early Life Stress on Education ( HiCN Working Paper 347). www.hicn.org

- Cervantes Duarte, L., & Fernández-Cano, A. (2016). Impact of Armed Conflicts on Education and Educational Agents: A multivocal review. Revista Electrónica Educare (Educare Electronic Journal, 20(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.20-3.12

- Chen, G. (2021). Parental involvement is key to student success. Public School Review.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. R. B. (2007). Research Methods in Education (6th ed.). Routledge.

- Creswell, J. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approach. SAGE Publications. http://library1.nida.ac.th/termpaper6/sd/2554/19755.pdf

- Epstein, J. L., Sanders, M. G., Sheldon, S. B., Simon, B. S., Salinas, K. C., Jansorn, N. R., & Williams, K. J. (2002). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action. Corwin Press.

- Franzoni, S., Gennari, F., Gandini, G., & Salvioni, S. (2012, January). School Governance: The roles of key actors. In conference proceeding International Congress for School, Effectiveness and Improvement (ICSEI), Sweden.

- Frounfelker, R. L., Islam, N., Falcone, J., Farrar, J., Ra, C., Antonaccio, C. M., Enelamah, N., & Betancourt, T. S. (2019). Living through war: Mental health of children and youth in conflict-affected areas. International Review of the Red Cross, 101(911), 481–506. https://doi.org/10.1017/S181638312000017X

- Garcia-Coles, E. R., & Sanchez Danday, A. S. Q. (2019). Will Raising Compulsory School Attendance Reduce Dropouts? Will Raising Compulsory School Attendance Reduce Dropouts? Journal of Education and Practice, 10(17), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.7176/JEP

- Hibi, W., & Assadi, N. (2021). What is the Effect of Parents ’ Involvement on the Students ’ Educational Attainment in Mathematics and Their Value System at School from the Teachers ’ Perspective? Creative Education, 2021(12), 1118–1139. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2021.125083

- Hussain, K., Muhiuddin, G., & Oad, L. (2021). The Influence of Parental Relationship on Students ’ Educational Attainment at Secondary Level in Karachi, Pakistan. Multicultural Education, 7(11), 415–423. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5722503

- Jaiswal, S. (2017). Role of Parental Involvement and Some Strategies That Promote Parental Involvement. Journal of International Academic Research for Multidisciplinary, 3(2), 95. www.jiarm.com

- Jones, A., & Naylor, R. (2014). The quantitative impact of armed conflict on education: counting the human and financial costs. http://educationandconflict.org/sites/default/files/publication/CfBT 023_Armed Conflict_Online.pdf

- Justino, B. P. (2014, September). Background Paper for Fixing the Broken Promise of Education for All Barriers to Education in Conflict-Affected. Relief Web International, 1–15. http://allinschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/OOSC-2014-Conflict-and-education-final.pdf

- Kumar, R. (2011). Research Methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners. SAGE Publications. http://library1.nida.ac.th/termpaper6/sd/2554/19755/.pdf

- Lara, L., & Saracostti, M. (2019). Effect of parental involvement on children’s academic achievement in Chile. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(JUN), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01464

- Manuchehr, T. N. (2011). Education rights of children during war and armed conflicts. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 302–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.090

- Martina, Z., & Anthony, M. (2020). Dynamics of Socio-Educational Environment on the Attainment of Students ’ Educational Aspirations. Greener Journal of Psychology and Counselling, 3(1), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.15580/GJPC.2019.1.060619106

- Mayai, A. (2022). War and Schooling in South Sudan, 2013-2016. Journal on Education in Emergencies, 8(1), 14–49. https://doi.org/10.33682/q16e-7ckp

- Omoeva, C., Hatch, R., & Moussa, W. (2018). The effects of armed conflict on educational attainment and inequality. Education Policy and Data Center Working Paper, (18–03).