Abstract

This study examines academic staff’s perceptions and applications of the deliberative and dynamic curriculum renewal model (DDCRM) in terms of developing curriculum renewal strategies, identifying graduate attributes, mapping learning pathways, auditing learning outcomes, developing and updating curricula and implementing programmes. The study was conducted at 21 faculties of education of the public universities across Saudi Arabia. The data included a total of 218 academic staff responded to a 5-point Likert scale and multiple-choice questions. A descriptive analysis, t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Scheffe test were used to analyse the data. The results indicate inconsistencies between academic staff perceptions and the application of DDCRM. The factors, both university-and system-related, included a lack of graduate attributes in the current accreditation requirements, heavy focus on short-termism in higher education and a lack of competencies seem to account for this inconsistency.

1. Introduction

Higher education has become a vital component of the education system, satisfying the needs of society and students, transmitting culture and increasing opportunities for knowledge creation and transformation by academics in the developmental universities (Colombari & Neirotti, Citation2022). However, the effectiveness of the higher education sector depends on how the higher education curriculum addresses challenging times of rapid change and upheaval. A important aspect of these challenges and changes has been the drive to produce systematic evidence of effectiveness. Curriculum is considered one of the most important components that can reveal the quality of higher education institutions (Cortese, Citation2003). The curriculum for higher education at universities needs to play a strategic role in finding solutions to today’s challenges in the fields of health, science, education, technology, renewable energy, psychology and the environment (C. Desha & Hargroves, Citation2014; Yates, Citation2012).

A few studies have explored the variation among disciplines regarding the major components of the curriculum, and a recent study has clarified how to conceptualise curriculum change (Barnett et al., Citation2001). However, recent studies have indicated that the common form of curriculum renewal in higher education institutions worldwide depends on individual academics undertaking their own development and updating of curricula in the absence of interactions with colleagues, industry or other local and wider university-implemented curricula, with a minimal amount of time invested in conducting academic reviews (C. J. Desha et al., Citation2009). Recently, the deliberative and dynamic curriculum renewal model (DDCRM) has been developed through collaboration with numerous universities (C. Desha & Hargroves, Citation2011; Fenner et al., Citation2005; Lozano, Citation2010; Rose et al., Citation2015). In order to be among the world’s top-ranked, the universities need to aim to be of the highest quality (Perkin, Citation2007). To accomplish this goal, the renowned universities in many parts of the world have implemented DDCRM as a whole-of-system approach that responds to emerging challenges and opportunities, encompassing curriculum renewal and organisational change at the level of staff and institution (Smith, Citation2013). However, in 1Saudi Arabian universities, and to a great extent in many other Arab countries, this approach has rarely been considered in higher education. Saudi universities have recently sought to develop their curricula and programmes to obtain accreditation from Saudi Arabia’s National Commission for Assessment and Academic or from international organisations (e.g. professional international accreditation, such as the Council for the Accreditation of Education Preparation). Many of the universities in Saudi Arabia, including most faculties of education, still face difficulties implementing improvements in curriculum renewal processes (Yusuf, Citation2017). A significant first step in this process is to understand the academic staff’s perceptions of the DDCRM as a gateway to improving future curriculum renewal processes. Although the importance of perceptions is a strong predictor, inconsistencies have been highlighted between perceptions and implementation (Judson, Citation2006; Mama & Hennessy, Citation2013). These inconsistencies have been attributed to contextual factors that interfere with the ability to implement the perceptions (Fang, Citation1996; Keys, Citation2005). Thus, perceptions, implementations and factors need to be considered to obtain a comprehensive conceptualisation of the integration process (Davis, Citation2010). Though previous studies in this area have provided useful information, a comprehensive research on academic staff perceptions and the application of the DDCRM, as well as the factors affecting their perceptions and application, is lacking. As such, this study aims to seek answers of the following research questions:

What is the extent of the perceived importance of the DDCRM by academic staff for curriculum renewal in Saudi faculties of education (SFEs)?

What is the extent of the DDCRM application by academic staff and in their curriculum renewal practices?

How and what degree do academic staff’s perceptions of the DDCRM align with their applications of the DDCRM?

What factors affect academic staff’s perceptions and applications of DDCRM?

2. Literature review

Research on curriculum development in Saudi higher education has been limited, but emerging issues have been identified in a few studies. Alqahtani (Citation2021) conducted a survey to explore the academic standards of educational programmes at Saudi universities. He indicated the importance of standards for the planning, design and evaluation phases and standards of administrative and formal procedures for approving educational programmes. Another study, conducted by Alnefaie and Gritter (Citation2016) attempted to raise EFL teachers’ awareness of how they participate in the curriculum development process. Although previous Saudi studies highlighted the importance of academic standards in educational programmes and the need to raise teachers’ awareness of how to participate in the curriculum development process, the first research gap could be identified in the relationship between perceptions and application. The second gap is the absence of evaluation studies on curriculum development. Even though universities continued articulating their plans for developing and updating curriculum development at the time of the current study, they omitted, formally and systematically, to evaluate the status of curriculum development. Therefore, especially regarding academic staff responses, there will be no insights to inform subsequent phases of the initiative. Furthermore, without in-depth exploration, the profound issues accompanying the implementation will remain concealed and the complexity of the implementation will be underestimated. The final gap is related to the methodology underpinning the previous Saudi context. Focusing on the perceptions of questionnaire-based surveys, the findings are exclusively based on sight, from which application is absent. A need emerges for comprehensive research on academic staff perceptions and application and the factors that will address this gap and provide an in-depth exploration.

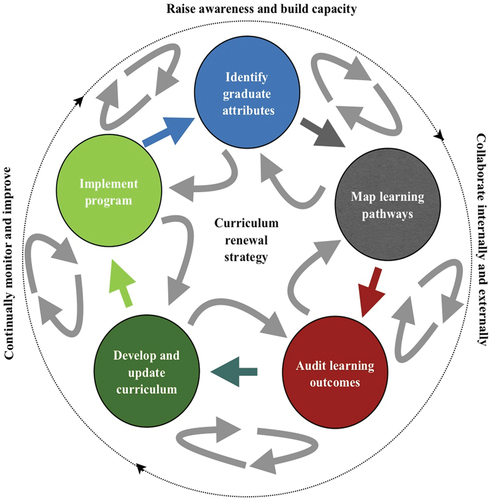

In the 21st century, tertiary educators have sought to document the iterative and vibrant nature of curriculum renewal and to highlight the need for an overarching strategy to drive the curriculum renewal process. Recently, the DDCRM has been developed through collaboration with numerous universities (C. Desha & Hargroves, Citation2011; Fenner et al., Citation2005; Lozano, Citation2010; Rose et al., Citation2015). The DDCRM comprises six essential “linear” deliberative elements, accompanied by four “cyclic” dynamic elements, which involve internal and external contexts throughout the process of developing the curriculum and building a community of learning around the process. The following are the deliberative elements for curriculum development: developing curriculum renewal strategies, identifying graduate attributes, mapping learning pathways, auditing learning outcomes and developing and updating curricula and implementing programmes. The dynamic elements involve raising awareness and building capacity, internal and external collaboration and continual monitoring and evaluation. The effectiveness of the model lies in that it provides a holistic approach to blending a deliberative process with a dynamic approach (Figure ).

Figure 1. The deliberative-dynamic model of curriculum development (C. Desha & Hargroves, Citation2014).

The curriculum renewal strategy is considered the centre of the curriculum renewal process in the DDCRM, which provides clarity and focus, aspirations, goals and milestones and potentially comprises the programme or department and institutional level (C. Desha & Hargroves, Citation2011; Fenner et al., Citation2005; Lozano, Citation2010; Rose et al., Citation2015). Early in the process, graduate attributes should be identified at the programme level to ensure that the curriculum renewal strategy is translated into meaningful knowledge and skill sets for graduating students that respond to a range of demands and predicted trends. Once graduate attributes are identified, mapping learning pathways through a programme provides an opportunity for an inclusive process to best present knowledge and skills to students as an integrated component of the programme that can be easily tracked and opportunities for synergies identified. Auditing the current existing content that delivers on the graduate attributes provides a key benchmark to inform the development of new materials. This will help identify priority action areas for curriculum renewal in the programme. A key aspect of the process is then to take time to check that the knowledge and skills designed into the learning path deliver the intended graduate attributes before going ahead and creating such material. Then, developing and updating the curriculum becomes a prioritised, informed and creative process of designing a learning experience that targets graduate attributes assigned to specific courses, threaded through learning pathways (C. Desha & Hargroves, Citation2014). Developed and updated curriculum is implemented with a clear understanding about the roles of existing and new content, delivery methods and assessment in which evaluation takes place with intentionality, focused on whether the curriculum fulfils expectations in developing learning outcomes (Rose et al., Citation2015). Raising awareness regarding the curriculum renewal process and capacity-building activities related to the ability to participate in the process are key dynamic activities undertaken by internal and external stakeholders. This may include faculty, staff, students and employers, through activities such as keynote lectures, public addresses, lunchtime seminars, media articles and the internal and external promotion of existing initiatives. To inform the curriculum renewal process, both internal and external collaborations are encouraged. External collaboration is important to ensure the relevance of changes to potential employers, current and future students, and current and future legislative and market environments. Internal collaboration is critical to assist in embedding the process into the programme design process. The dynamic activities also ask for monitoring and evaluation to encourage continual improvement within and between each of the steps and throughout programme delivery. This involves evaluating whether the intentions of the curriculum renewal strategy are being met through the implemented course-level changes and ensuring adherence to the curriculum renewal strategy (C. Desha & Hargroves, Citation2014).

3. Methodology

The perceptions and applications of the academic staff were examined using a survey method. The data were collected using a web-based questionnaire. The respondents were asked to respond to statements about the DDCRM elements using a 5-point Likert-type scale: 5) “Very Important”, (4) “Important”, (3) “Slightly Important”, (2) “Fairly Important” and (1) “Not Important” for the levels of importance and (5) “Very High”, (4) “High”, (3) “Moderate”, (2) “Low” and (1) “Very Low” for the levels of the application. The criteria for data analysis are presented in Table .

Table 1. Criteria for data analysis

A questionnaire was used to conduct this survey so that participants could respond to the questions with the assurance that their responses would be anonymous, which would enable them to be more truthful than they might be in a personal interview (Leedy & Ormrod, Citation2019). Furthermore, a 5-point Likert-type scale was used in the current study survey to illustrate a scale with equal intervals among responses and has become widely used in research, particularly for collecting data on opinions and reported practices (Cohen et al., Citation2018). The survey comprised 33 statements, which were common for the DDCRM used in higher education, divided into four sections. These statements were developed from a range of materials generated by C. Desha and Hargroves (Citation2011), Sheehan et al. (Citation2012) and Rose et al. (Citation2015). However, the survey items were refined by the researcher for contextual relevance. Next, the survey was field tested using a three-step process. First, it was pilot tested with 14 academics from different SFEs to ensure its validity and reliability in the context of the DDCRM. Second, a group of five experienced teaching academics reviewed the questionnaire content item by item and made further editorial revisions. Third, the reliability of the survey was measured using Cronbach’s alpha (a) reliability coefficient to determine the internal consistency of the academic staff’s perception questionnaire (ASQ) subscales (perception of curriculum renewal strategy, identifying graduate attributes, mapping learning pathways, auditing learning outcomes, developing and updating curriculum and implementing programme) and total items (Table ).

Table 2. Cronbach’s alpha and number of items of the ASQ subscales and total items for academic staff (n = 218)

According to DeVellis (Citation1991), a degree of reliability that is higher than 0.70 is considered acceptable for Cronbach’s alpha scores. The Cronbach’s alpha scores for the ASQ subscales were 0.72 and 0.93, respectively, and for the total items, a = 0.93, which suggested that the subscales and total items of the ASQ achieved a highly acceptable level of internal consistency. According to Nunnally and Bernstein (Citation2017), if you want validity, you must have reliability, but it is not a sufficient condition for validity. All participants in this study were native Arabic speakers, therefore, to ensure validity, the ASQ was prepared in Arabic. Moreover, a probability (random) quantitative sample was employed, and data were collected from various universities to effectively examine variations in academic staff’s perceptions of the DDCRM. Cohen et al. (Citation2018) indicated that a probability (random) sample is one of the best methods for selecting a research sample because it has a lower risk of bias compared to a nonprobability sample. As such, the widely accepted cluster and systematic random sampling techniques were adopted in order to draw a representative sample for the current study. In this technique, the participants are first randomly selected (Gay et al., Citation2011). This is considered an appropriate technique especially when the population is dispersed over a wide geographic area (Gay et al., Citation2011). As 21 SFEs across various regions of Saudi Arabia were involved in this study, it was considered a convenient method for this study. As required, before starting the study, all the necessary ethical approvals were obtained from Umm Al-Qura University, which handles providing approval and the consent form for conducting new research in faculties of education in Saudi Arabia (Umm Al-Qura University Ref No: 4201110158) in 12 June 2021. Table presents the demographic characteristics of the academic staff members who completed the online survey.

Table 3. Summary of academic staff’s demographic characteristics

The study participants represented 21 SFEs, which were categorised to involve five response categories that represented regional information. The regions included the west region, which had more than a third (42.7%, n = 93) of the respondents, the central region, which had almost a third of (30.7%, n = 67), the southern region, which had 10.1% (n = 22), the northern region, which had 8.7% (n = 19) and the eastern region, which comprised 7.8% (n = 17). Table presents the distribution of the participating academic staff by participation in curriculum development activities. More than one-third (40.4%, n = 88) of the respondents had taken workshops. Other activities included teamwork (29.8%, n = 65) within the academic network specifically formed for curriculum development purposes or participation in educational agencies (23.9%, n = 25). Regarding the qualitative data, 6% of the participants reported that they had worked at their universities as members of curriculum centres to develop and review educational programmes.

4. Findings

The current study investigated the relationship between academic staff perceptions and the application of the DDCRM at the SFE. It explored the level of importance of the DDCRM and its application among the academic staff, alignment between their perceptions and applications of the DDCRM, and identified factors affecting its perceptions and application at their institutions.

4.1. Academic staff perceptions and applications

This section addresses the first three research questions: levels of importance (RQ1), application of DDCRM (RQ 2) and alignment between perceptions and applications of DDCRM (RQ 3). However, as described in the literature section, the DDCRM comprises of six essential elements, namely, developing curriculum renewal strategies, identifying graduate attributes, mapping learning pathways, auditing learning outcomes, developing and updating curricula and implementing programmes. Therefore, this sub-section is organised around an analysis of these six elements, along with each of the first three research questions. RQ1, RQ2 and RQ3 were used to frame the analysis and presentation of results in this sub-section.

4.1.1. Curriculum renewal strategy area

In Table , the mean scores for the level of importance and application of the curriculum renewal strategy items are summarised. As it can be seen, 4.5 or more was the mean score for all four items of curriculum renewal strategy indicating that the clear majority of the participants agreed on their importance. Among them, the most important statement was item 1, Providing clarity in all steps of the curriculum development process (M = 4.78, SD = 0.59). The overall mean score for the level of importance of curriculum renewal strategy items was M = 4.67, SD =.54.

Table 4. Paired samples t-test comparison between the levels of importance and application of curriculum renewal strategy items (N = 218)

However, the mean score for the level of application of these four items ranged between low (M = 2.59) and moderate level (M = 3.40). Item 4, Aligning with the whole programme’s goals, received the highest score (M = 3.40, SD = 0.95) and item 2, Engaging staff in the focus process of curriculum development, received the lowest score (M = 2.59, SD = 1.06). The overall mean score for the level of application of all curriculum renewal strategy items was M = 3.24, SD =.98. This shows that the mean score for the level of importance of curriculum renewal strategy items was not supported by the corresponding mean level of application. In order to examine this discrepancy, a paired samples t-test was conducted, also shown in Table . Analysing the results of this test, showed that the mean score for the level of importance (M = 4.67, SD = 0.54) far exceeded the level of application (M = 3.24, SD =.98), (t (217) = 18.972, p < .05). This indicates that the academic staff at SFEs perceived the four items of curriculum renewal strategy as important, but they could not apply them at a high level.

4.1.2. Identify graduate attributes area

Table shows the mean scores for the levels of importance and application of the identify graduate attributes items. In terms of importance, most participants agreed on the importance of items for identifying graduate attributes, with mean scores ranging between M = 4.50 and M = 4.59. All three items met “very important” mean score for the level of importance (4.5 or more), with the most important statement being item 2, Transferring into meaningful knowledge and skills (M = 4.59, SD = 0.63). In summary, for each item, there was significant agreement among the participants. Moreover, the overall mean score for the level of importance for identifying graduate attributes items was M = 4.55, SD =.54. In terms of application, for most participants, the mean score for the level of application for the four items ranged between M = 3.01 and M = 3.19, where the highest scoring statement was item 2, Transferring into meaningful knowledge and skills (M = 3.19, SD = 1.04). The lowest application was found for item 1, Linking with the curriculum renewal strategy (M = 3.01, SD = 1.69). In summary, the overall mean score for the application level for all identify graduate attributes items was M = 3.09, SD =.84.

Table 5. Paired samples t-test comparison between the levels of importance and application of identify graduate attributes items (N = 218)

Regarding alignment between levels of importance and application of identifying graduate attribute items, the mean score for the level of importance for the curriculum renewal strategy items was not supported by the corresponding score for the application of practices. However, to analyse the discrepancy between the levels of importance and application of identifying graduate attribute items, a paired samples t-test was conducted, as shown in Table . The results indicated a statistically significant difference, with the mean score for the level of importance (M = 44.55, SD = 0.54) exceeding that of the level of application (M = 3.09, SD =.84); (t [217] = 21.440, p < .05). These results suggest that the study participants perceived identifying graduate attribute items as important, but they could not apply them at a high level.

4.1.3. Map learning pathways area

Table shows the mean scores for the level of importance and application of mapping learning pathways. In terms of importance, most participants agreed on the importance of items for mapping learning pathways, with mean scores ranging between M = 4.53 and M = 4.67. All seven items met the “very important” mean score for the level of importance (4.5 or more). The most important statement among them was item 3, Representing required component knowledge and skill sets (technical and enabling) with M = 4.67, SD = 0.57. In summary, for each item, there was significant agreement among the participants. Moreover, the overall mean score for the level of importance for map learning pathways was M = 4.59, SD =.47. In terms of application, for most participants, the mean score for the level of application for the seven items ranged between M = 2.69 and M = 4.07, with item 4, Identifying appropriate levels of coverage at each year level, being the highest scoring item (M = 4.07, SD =.72). The lowest application was found for item 1, Analysing current content against new knowledge and skills (M = 2.69, SD = 0.83). In summary, the overall mean score for the level of application for all map learning pathway items was M = 3.30, SD =.51.

Table 6. Paired samples t-test comparison between the levels of importance and application of mapping learning pathways (N = 218)

In terms of alignment between levels of importance and application of mapping learning pathways, the mean score for the level of importance was not supported by the corresponding score for the application of practices. However, to analyse the discrepancy between the levels of importance and application of mapping learning pathways items, a paired samples t-test was conducted, as shown in Table . The results indicated a statistically significant difference, where the mean score for the level of importance (M = 4.59, SD = 0.47) exceeded that for the level of application (M = 3.30, SD =.51), (t [217] = 26.867, p < .05). These results suggest that the study participants perceived mapping learning pathways as important but could not apply them at a high level.

4.1.4. Audit learning outcomes area

Table shows the mean scores for the level of importance and application of the auditing learning outcomes items. In terms of importance, most participants agreed on the importance of items for auditing learning outcomes, with the mean scores ranging between M = 4.58 and M = 4.67. All three items met the “very important” mean score for the level of importance (4.5 or more), with the most important statement being item 1, Evaluating knowledge and skill development gaps in the current curriculum (M = 4.67, SD = 0.57). In summary, for each item, there was significant agreement among the participants. Moreover, the overall mean score for the level of importance for auditing learning outcomes items was M = 4.62, SD =.52.

Table 7. Paired samples t-test comparison between the levels of importance and application of auditing learning outcomes items (N = 218)

In terms of application, for most participants, the mean score for the level of application for the three items ranged between M = 2.77 and M = 2.94, with the highest scoring being item 2, Resourcing implications and priorities for moving forward in curriculum renewal (M = 3.05, SD =.86). The lowest application was found for item 1, Evaluating knowledge and skill development gaps in the current curriculum (M = 2.77, SD = 0.82). In summary, the overall mean score for the level of application for all audit learning outcomes items was M = 2.92, SD =.75. In terms of alignment between levels of importance and application of auditing learning outcomes items, the mean score for the level of importance for mapping learning pathways items was not supported by the corresponding score for the application of practices. However, to analyse the discrepancy between the levels of importance and application of auditing learning outcomes items, a paired samples t-test was conducted, as shown in Table . The results indicated a statistically significant difference, with the mean score for the level of importance (M = 4.62, SD =.52) being greater than that for the level of application (M = 2.292, SD =.75); (t (217) = 26.664, p < .05). These results suggest that the study participants perceived auditing learning outcomes items as important but could not apply them at a high level.

4.1.5. Develop and update curriculum areas

Table shows the mean scores for the levels of importance and application of the develop and update curriculum items. Most participants agreed on the importance of items for developing and updating curricula, with the mean scores ranging between M = 4.51 and M = 4.61. All eight items met the “very important” mean score for the level of importance (4.5 or more), with the most important statement being item 7, Providing ongoing capacity-building opportunities for academic staff (M = 4.68, SD = 0.57). In summary, for each item, there was significant agreement among the participants. Moreover, the overall mean score for the level of importance for audit learning outcomes items was M = 4.57, SD =.49.

Table 8. Paired samples t-test comparison between the levels of importance and application of develop and update curriculum items (N = 218)

For most participants, the mean score for the level of application for the eight items ranged between M = 3.06 and M = 3.41, with the highest scoring item being item 8, Incorporating research opportunities (M = 3.41, SD =.86). The lowest application was found for item 2, Considering content and assessment implications for the course (M = 3.06, SD = 0.83). In summary, the overall mean score for the level of application for all develop and update curriculum items was (M = 3.24, SD =.67). Regarding the alignment between levels of importance and application of develop and update curriculum items, the mean score for the level of importance for developing and updating curriculum items was not supported by the corresponding score for application of practices. However, to analyse the discrepancy between the levels of importance and application, a paired samples t-test was conducted, as shown in Table . The results indicated a statistically significant difference, with the mean score for the level of importance (M = 4.57, SD =.49) being greater than that for the level of application (M = 3.24, SD =.67); (t (217) = 23.410, p < .05). These results suggest that the study participants perceived developing and updating curriculum items as important but could not apply them at a high level.

4.1.6. Implement programme areas

Table shows the mean scores for the levels of importance and application of the implement programme items. Most participants agreed on the importance of items for implementing the programme, with the mean score ranging between M = 4.24 and M = 4.92. All items met the “very important” mean score for the level of importance (4.5 or more) except item 1, Addressing the intended learning outcomes (M = 4.24, SD =.69). The most important statement was item 7, Involving activities that allow for interaction and communication with professional bodies (M = 4.92, SD = 0.29). In summary, for each item, there was significant agreement among the participants. Moreover, the overall mean score for the level of importance for implement programme items was (M = 4.68, SD =.26).

Table 9. Paired samples t-test comparison between the levels of importance and the application of implement programme items (N = 218)

In terms of application, for most participants, the mean score for the level of application for the eight items ranged between (M = 3.39) and (M = 3.98), with the highest scoring statement being item 4, Understanding the content of renewal curriculum (M = 3.98, SD =.98). The lowest application was found for item 8, Supporting renewed curriculum by institutional management (M = 3.39, SD = 0.98). In summary, the overall mean score for the level of application for all develop and update curriculum items was (M = 3.82, SD =.86). In terms of alignment between levels of importance and application of implement programme items, the mean score for the level of importance was not supported by the corresponding score for application of practices. However, to analyse the discrepancy between the levels of importance and application of implement programme items, a paired samples t-test was conducted, as shown in Table . The results indicated a statistically significant difference, with the mean score for the level of importance (M = 4.68, SD =.26) being greater than that for the level of application (M = 3.82, SD =.86); (t (217) = 14.244, p < .05). These results suggest that the study participants perceived implementing programme items as important but could not apply them at a high level.

4.2. Alignment between academic staff’s perceptions and applications

In terms of alignment between levels of importance and application of the DDCRM elements, as displayed in Table , the mean score for the level of importance was not supported by the corresponding mean score for application.

Table 10. Paired samples t-test comparison between the levels of importance and application (N = 218)

To analyse the discrepancy between the levels of importance and application of the DDCRM elements, a paired samples t-test was conducted, as shown in Table . The results also indicate a statistically significant difference with the mean score for the level of importance (M = 4.75, SD = 0.47) exceeding that for the level of application (M = 3.23, SD = 0.99), (t [217] = 21.410, p < .05). These results suggest that the study participants perceived the DDCRM elements and items as important but could not apply them. Consequently, a substantial gap existed between academic staff members’ endorsement of the DDCRM as important for curriculum renewal and its practical application in SFEs.

4.3. Factors affecting academic staff’s perceptions and applications

The results indicate several barriers to applying the DDCRM in SFEs. These barriers were reorganised into 10 key category barriers: persistent traditional education practices, lack of faculty competencies, growing disconnect between practices and science, persistent old curriculum development models, lack of convenient access to emerging knowledge, focus on short-termism in higher education, lack of access to information in foreign languages, insufficient resources, lack of interaction between professional bodies and employers and accreditation requirements that do not include graduate attributes. The frequency counts across categories were examined to identify the primary barriers to applying the DDCRM, as summarised in Table .

Table 11. Frequencies of barriers to DDCRM application

Overall, the results indicate that there were 1821 responses of the barriers to the application of DDCRM listings. Table summarises the frequencies and percentages of these barriers across the 10 category barriers. Accreditation requirements do not include graduate attributes (11.80%), focus on short-termism in higher education (11.75%), lack of faculty competencies (11.69%), persistent traditional education practices (11.47%), persistent old curriculum development models (11.25%) and lack of convenient access to emerging knowledge (10.37%) were identified as the key barriers to applying the DDCRM. The “Other” category received comments (4.77%), with barriers such as large class sizes, time limitations and constraints. Consequently, all 10 category barriers were merged as prominent barriers to DDCRM application within the SFEs.

5. Discussion

As outlined above, the results of this study clearly show that there’s a significant gap between the perceived importance of various elements of the DDCRM and actual implementation of these elements in SFE practices. Most participants agreed with high ratings that it essential to use the DDCRM, reflecting the academic staffs’ willingness to apply it to their institutions. In contrast, they did not apply these Deliberative and Dynamic Curriculum Renewal elements consistently in their practice. Thus, the challenge for SFE is to move from perceiving the importance of these DDCRM practices to fully applying such practices. In terms of the level of importance of DDCRM elements, the findings of this study matched those from previous research (Rose et al., Citation2015), which indicated that the DDCRM is important for renewal and developing higher education curricula. This finding suggests that the academic staff in the SFEs had a high level of prior knowledge of the importance of deliberative and dynamic curriculum renewal. A possible explanation for this finding can also be explained by the recent educational reforms within the Saudi academic system by adapting different international approaches to the Saudi curriculum context.

The current study found that providing clarity in all steps of the curriculum development process was one of the most important indicators of the curriculum renewal strategy, with deliberative and dynamic curriculum renewal. This finding is consistent with previous findings, which indicates that the process of curriculum renewal requires considerable planning and clarity (Leal Filho et al., Citation2019). Also, transferring meaningful knowledge and skills was found to be the most important for identifying graduate attributes. Moreover, the most important item for mapping learning pathways was Representing required component knowledge and skill sets (technical and enabling). This result agrees with that obtained by Oliver and Jorre de St Jorre (Citation2018), who suggested that all providers and universities should make graduate attributes more visible by embedding them in the assessed curricula, clearly identifying and explaining them, and continuing to regularly revise the attributes to ensure that they fit the purpose of curriculum in a rapidly changing environment.Also, Evaluating knowledge and skill development gaps in the current curriculum and Resourcing implications and priorities for moving forward in curriculum renewal were the most important for auditing learning outcomes. This result is in agreement with that of Zhao and Shi (Citation2021), which indicates a considerable crossover among the broad categories of attributes identified as important to employers and industry bodies and the recommendation for universities that were to revise their own graduate attributes on the basis of universities’ history, vision and specialty. Another important item cited in this study was Providing ongoing capacity-building opportunities for academic staff. This finding is supported by the result of Honkimäki et al. (Citation2021), where a top-down curriculum reform creates conflict between academia’s own ideas regarding curriculum renewal. Also, benefiting from the platforms, media and technology implications for curriculum was found to be the most important for developing and updating the curriculum. This finding is supported by Marshall (Citation2010), who emphasised technologies as vehicles to enable changes that are intended or to reinforce the current identity.

Regarding application, the study found that the academic staff applied dynamic and deliberative curriculum renewal elements only at low-to-moderate levels. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies conducted at different universities (Rose et al., Citation2015; Watson et al., Citation2013), which indicate that the transition to the DDCRM is still slow and that the research explaining how to use this model to incorporate new content into university curricula remains limited. However, the relationship between perceptions and application of DDCRM (as it emerged from the data analysis) suggests the need for a more thorough examination of the involved factors. Current accreditation requirements, focus on short-termism in higher education, lack of faculty competencies, persistent traditional education practices, persistent old curriculum development models and lack of convenient access to emerging knowledge are factors that negatively influence some academic staffs’ application of the DDCRM.

6. Future research

The current study explored the relationships and factors affecting academic staff perceptions and applications of deliberative and dynamic curriculum renewal models. However, due to the limitations of the study, it wasn’t possible to do a detailed assessment of the academic staff members’ views. A further study comprising personal interviews and focus groups with academic staff could be both interesting and informative. Such research could provide additional understanding of the influence of these factors.

7. Conclusion

This study has examined academic staff members’ perceptions, application and factors affecting the use of the DDCRM model in Saudi Arabia. To date, no research study has explored the use of the DDCRM model in SFE and in the Asia-Pacific region. The main goal of curriculum development is to have an effective design. This study has confirmed that exploring academic staff members’ perceptions of the importance of the DDCRM model in developing curricula could be useful in several ways. Most significantly, exploring their application of the DDCRM model was useful in identifying the gap between levels of importance and the application of DDCRM elements and in examining the barriers to the effective application of the DDCRM model in SFE to determine what shift will be required to facilitate systemic change within SFE. This is particularly so if the application, including a whole system approach, involves a curriculum renewal strategy, identifying graduate attributes, mapping learning pathways, auditing learning outcomes, developing and updating the curriculum and implementing the programme.

The findings of this study indicate that academic staff members are aware of the DDCRM model and perceive most of its elements to be important and useful. They also perceived a lack of application of DDCRM. These findings might benefit decision makers, university leaders, and the Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia by providing a comprehensive lens for investigating the current application of the DDCRM model and the factors affecting its application. The findings should also encourage the taking of appropriate action to improve the preparedness of all academic staff at SFE.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (8.3 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2195747.

References

- Alnefaie, S. K., & Gritter, K. (2016). Teachers’ role in the development of EFL curriculum in Saudi Arabia: The marginalised status. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1240008. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1240008

- Alqahtani, S. (2021). The academic standards of educational programs at Saudi universities (Arabic language as a model). Educational Journal, 2(27), 14–17.

- Barnett, R., Parry, G., & Coate, K. (2001). Conceptualising curriculum change. Teaching in Higher Education, 6(4), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510120078009

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. Routledge.

- Colombari, R., & Neirotti, P. (2022). Closing the middle-skills gap widened by digitalization: How technical universities can contribute through Challenge-Based Learning. Studies in Higher Education, 47(8), 1585–1600. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1946029

- Cortese, A. D. (2003). The critical role of higher education in creating a sustainable future. Planning for Higher Education, 31(3), 15–22.

- Davis, N. (2010). Global interdisciplinary research into the diffusion of information technology innovations in education. In A. McDougall, J. Murnane, A. Jones, & N. Reynolds (Eds.), Researching IT in education (pp. 158–166). Routledge.

- Desha, C., & Hargroves, K. C. (2011). Informing engineering education for sustainable development using a deliberative dynamic model for curriculum renewal. Proceedings of the 2011 Research in Engineering Education Symposium, UPM University Madrid, Spain. (pp. 1–7). https://eprints.qut.edu.au/70569/

- Desha, C., & Hargroves, K. (2014). Higher education and sustainable development: A model for curriculum renewal. Earthscan-Routledge.

- Desha, C. J., Hargroves, K., & Smith, M. H. (2009). Addressing the time lag dilemma in curriculum renewal towards engineering education for sustainable development. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 10(2), 184–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370910949356

- DeVellis, M. (1991). Reliability test of attitudinal instruments. Annual Research Conference, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

- Fang, Z. (1996). A review of research on teacher beliefs and practices. Educational Research, 38(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188960380104

- Fenner, R. A., Ainger, C. M., Cruickshank, H. J., Guthrie, P. M., & Ferrer‐balas, D. (2005). Embedding sustainable development at Cambridge University Engineering Department. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 6(3), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370510607205

- Gay, L. R., Mills, G. E., & Airasian, P. W. (2011). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and applications. Pearson Higher Ed.

- Honkimäki, S., Jääskelä, P., Kratochvil, J., & Tynjälä, P. (2021). University-wide, top-down curriculum reform at a Finnish university: Perceptions of the academic staff. European Journal of Higher Education, 12(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2021.1906727

- Judson, E. (2006). How teachers integrate technology and their beliefs about learning: Is there a connection? Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 14(3), 581–597.

- Keys, P. M. (2005). Are teachers walking the walk or just talking the talk in science education? Teachers and Teaching, 11(5), 499–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600500238527

- Leal Filho, W., Skanavis, C., Kounani, A., Brandli, L. L., Shiel, C., Do Paco, A., Pace, P., Mifsud, M., Beynaghi, A., Price, E., Salvia, A. L., Will, M., & Shula, K. (2019). The role of planning in implementing sustainable development in a higher education context. Journal of Cleaner Production, 235, 678–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.322

- Leedy, P. D., & Ormrod, J. E. (2019). Practical research: Planning and design. ERIC.

- Lozano, R. (2010). Diffusion of sustainable development in universities’ curricula: An empirical example from Cardiff University. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18(7), 637–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.07.005

- Mama, M., & Hennessy, S. (2013). Developing a typology of teacher beliefs and practices concerning classroom use of ICT. Computers & Education, 68, 380–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.05.022

- Marshall, S. (2010). Change, technology and higher education: Are universities capable of organisational change? Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(8). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1018

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. (2017). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Oliver, B., & Jorre de St Jorre, T. (2018). Graduate attributes for 2020 and beyond: Recommendations for Australian higher education providers. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(4), 821–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1446415

- Perkin, H. (2007). History of universities. In J. F. (Ed.), International handbook of higher education (pp. 159–205). Springer Publication.

- Rose, G., Ryan, K., & Desha, C. (2015). Implementing a holistic process for embedding sustainability: A case study in first year engineering, Monash University, Australia. Journal of Cleaner Production, 106, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.066

- Sheehan, M., Desha, C., Schneider, P., & Turner, P. (2012). Embedding sustainability into chemical engineering education: Content development and competency mapping.

- Smith, M. H. (2013). The natural advantage of nations: Business opportunities, innovations and governance in the 21st century. Earthscan.

- Watson, M. K., Lozano, R., Noyes, C., & Rodgers, M. (2013). Assessing curricula contribution to sustainability more holistically: Experiences from the integration of curricula assessment and students’ perceptions at the Georgia Institute of Technology. Journal of Cleaner Production, 61, 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.09.010

- Yates, L. (2012). My school, my university, my country, my world, my Google, myself … What is education for now? The Australian Educational Researcher, 39(3), 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-012-0062-z

- Yusuf, N. (2017). Changes required in Saudi universities curriculum to meet the demands of 2030 vision. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 9(9), 111–116. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v9n9p111

- Zhao, R., & Shi, W. -B. (2021). Study of graduate attributes of the University of Sydney and implications for building Chinese world-class universities. The International Journal of Electrical Engineering & Education, 0020720920984311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020720920984311