?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the effectiveness of the academic advising system in higher education institutions in Oman, with an emphasis on the College of Banking and Financial Studies in Muscat. The study adopted a sequential mixed approach (SMA), combining qualitative and quantitative methods. A structured questionnaire involving 128 advisees, in addition to in-depth interviews with three advisors, have been employed in the data collection. The study used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and non-parametric tests of chi-square and Spearman rank correlation to conclude that advisee-induced factors as well as advisor-induced factors have an influential impact on the effectiveness of the academic advising process. Furthermore, the study established a positive link between advisee performance and satisfaction with academic advising. The implications of the factors influencing the academic advising process were discussed, and some recommendations were made to enhance the effectiveness of academic advising in higher education institutions in Oman.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Academic advising represents resources for higher education institutions that support students to navigate their learning journeys successfully. Advisors assist in monitoring the academic progress of the student and recommend students with potential for certain opportunities that will enhance their experience, retention, and graduation.

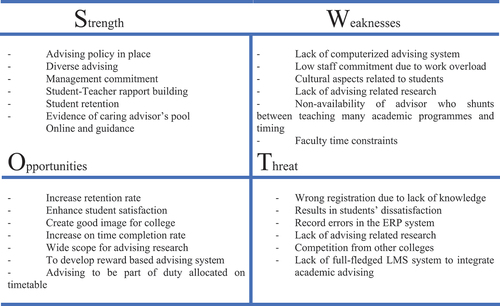

This paper examined the effectiveness of the practical implementation of the advising systems in higher education institutions (HEI) in Oman, with a focus on the College of Banking and Financial Studies (CBFS), the first government institution in Oman to be awarded institutional accreditation from the Oman Academic Accreditation Authority (OAAA). The paper identified the weaknesses, strengths, opportunities, and threats of the existing model and provided some recommendations to enhance its effectiveness.

The findings of the study revealed the first-hand experiences of the practitioners of the academic advising system, which is intended for teachers, education managers, and policy makers in higher education who are involved in academic advising.

Introduction

With the qualitative focus on student-centric learning in higher education, the importance of academic advising has become a sine qua non in student support systems in higher educational institutions (Campbell & Nutt, Citation2008; Chan et al., Citation2019). Academic advising has been touted as one of the most important ways to increase student retention and overall student satisfaction (Azianti et al., Citation2021; Paul & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015; Soden, Citation2017). By its early definition by Winston et al. (Citation1984), academic advising is a continuous process where the advisee and the advisor meet regularly and the former is helped to achieve his or her academic, career, and personal goals. It is about relationship-building in which the academic advisor acts as a mentor, guide, and positive influence on their students’ attainment (Gordon-Starks, Citation2015; Holland et al., Citation2020). The goal of academic advising is to promote intellectual and personal growth in students by providing them with the skills and attitudes they need to pursue their studies successfully. On similar lines, Iatrellis et al. (Citation2017) describe academic advising as an interaction between assigned academic advisors and students to provide students with guidance and advice. In addition, Drake et al. (Citation2013) view that different approaches to academic advising involve different sets of strategies that academic advisors use in practice. The main function of an academic advisor is to provide holistic support to students as they navigate their higher education and postgraduate journeys, which will be reflected in their performance and persistence (Aaishah et al., Citation2021; Loucif et al., Citation2020).

Academic advising systems encourage students to identify issues affecting their academic progress. This is also to make effective referrals to appropriate support services to help students in their academic endeavors. However, with the increase in staff-to-student ratio in several institutions, coupled with other administrative responsibilities for these teachers who are advisors, there has been growing concern about the efficacy of the system. To ensure effective advising and student satisfaction with the process, the advisor should have good knowledge and information of the College rules and regulations, good communication skills, and a positive relationship with students (Mottarella et al., Citation2004; Mu & Kevin, Citation2019).

Although academic advising systems are intended to enhance student experience in higher educational institutions, based on a review of recent studies on their implementation, several challenges are identified (Mangundu, Citation2022). Based on user feedback, these shortcomings are identified as a risk to achieving the objectives of the academic advising system. Despite global research on the topic (Azianti et al., Citation2021; Loucif et al., Citation2020; Mu & Kevin, Citation2019), there has been limited exploration of the same in Omani higher educational institutions in recent times. This exploration is particularly important as students in Oman enroll in college at a younger age. They face numerous challenges because of the abrupt change in educational environment from secondary education, resulting in high probation rates and low success and graduation rates. There is an average of 7,000 students dropping out of degree courses a year in Oman due to the lack of a career guidance system to advise students on their future (Shaibany, Citation2016; Thumiki, Citation2019). The high dropout rate is putting considerable financial pressure on the government’s scholarship system and taking away a potential knowledge pool from the private sector. There are also concerns about students who take longer to complete their courses or those who change institutions after going through academic struggles.

The main objective of this paper is to evaluate the effectiveness of the practical implementation of the advising systems in higher education institutions (HEI) in Oman. The College of Banking and Financial Studies (CBFS) has been selected as a case study as it is the first government institution in Oman to be awarded institutional accreditation from the Oman Academic Accreditation Authority (OAAA). The experience of the College in academic advising is worth examining, and the lessons to be learned can serve as a model for other colleges in Oman.

The findings of the study will reveal the first-hand experiences of the practitioners of the academic advising system, which is intended for teachers and education managers in higher education who are involved in academic advising. The study is expected to uncover areas for improvement that can help design and deploy more equitable advising strategies for educational institutions across Oman.

Literature review

This section reviews global deliberations on academic advising carried out at higher educational institutions in the past two decades. Since the beginning of the current century, effective academic advising systems have been recognized and recommended as a vital element in students’ success, academic retention, and satisfaction. Azianti et al. (Citation2021) investigated the link between students’ satisfaction and academic advising service among students at the UiTM Pasir Gudang campus in Malaysia. The study concluded that the number of years of study and the frequency of meetings with advisors affect students’ satisfaction with academic advising. Moreover, the study showed that reliability and empathy play essential roles in the success of academic advising services, with both having a significant relationship with students’ satisfaction. Soden (Citation2017) conducted a qualitative study using focus groups and interviews about perceptions of academic advising and student retention at Lindenwood University in the USA. The results of the study revealed a positive link between progressive academic advising strategies and student retention. Similarly, Paul and Fitzpatrick (Citation2015) investigated student satisfaction with servant leadership—based advising in a sample of 428 graduates in the southeast United States. The study confirmed a positive correlation between servant leadership and student satisfaction with advising.

Although academic advising for higher education students has traditionally been seen as a ’faculty function’ (Tuttle, Citation2000, p. 15), of late, several practical difficulties in its implementation have been found in different quarters of higher education institutions. Learners have consistently given feedback that they have had limited benefit from the advisory systems, especially when they deal with advisors with questionable competence, experience, and care (Mastrodicasa, Citation2001).

Various structural models for academic advising are identified, in which each style depends on the extent of engagement by the faculty advisor in the process (Kramer, Citation2003). Different institutional models were developed under which academic advising is commonly structured (Kuhtmann, Citation2004; Tuttle, Citation2000). The most popular model is the faculty-only model, in which each learner is assigned to a faculty member who belongs to the learner’s area of specialisation for all academic advising matters. Another one is the satellite model, also known as the multiversity model, in which separate advising offices are maintained and controlled by the different academic specialisation units. Yet another model is the self-contained model, where all learners have access to trained professional academic advisors and are supervised by the academic dean. In this model, a learner does not have any direct interaction with their faculty. In a modified version of this model, the shared-supplementary model, faculty members provide basic academic advising but are assisted by professionals from a specialized section. Usually, this model provides coordination and training for the members of the faculty, as well as liaising with students for their other academic needs. In addition to the human academic advisors, there are recent examples of automated academic advising that have been shown to be very effective. This includes rule-based expert systems (Al-Ghamdi et al., Citation2012); recommender systems (Fong & Biuk-Aghai, Citation2009); and chatbot-based systems (Amin Kuhail et al., Citation2022).

In more recent times, challenges in the academic advising system have been identified and addressed. According to Habley et al. (Citation2012), without a consensus definition, advisors face the challenge of communicating to each other about a common approach taken for advising or agreeing on the goals and activities of advising. Another issue raised by Cobb et al. (Citation2018) is the difference in approaches to academic advising adopted by academics. Significant differences exist at various higher educational institutions where academic advisors share multiple roles and responsibilities as educators, counselors, and mentors. Cobb et al. (Citation2018) further draw attention to various factors influencing the advisory role. This includes the level of commitment and involvement with the advisee, as well as the advisee’s willingness to engage in the process.

’

Peno et al. (Citation2016) observe that relationships between mentor and mentee can be formal or informal, can extend to more than two individuals or teams, and may even involve psychosocial and instrumental support too. Regardless of the model or approach to academic advising, teaching faculty play an important role in completing tasks effectively. A “mentoring relationship” is operationalized by faculty engagement with them and the learners (Yarbrough, Citation2002, p. 65). The faculty are expected to provide “specific insight and expertise” that guides the students (Yarbrough, Citation2002, p. 67).

Based on the above literature and to assess the effectiveness of the academic advising system at the CBFS, the paper validates the following two hypotheses:

H1:

There is a positive relationship between the effectiveness of academic advising and student performance at CBFS.

H2:

The effectiveness of the academic system at CBFS depends on factors related to both advisors and advisees.

Materials and methods

The study adopted a sequential mixed approach (SMA). It combines qualitative and quantitative methods to address the practice and challenges of the academic advising system in the CBFS.

Both primary and secondary data collection methods have been used. Primary data were combined using structured questionnaires designed for college advisees, and in-depth interviews with three academic advisors were conducted, in addition to gathering general perspectives on academic advising (AA) from a variety of faculty, including tertiary and preparatory programs. Secondary sources included documents pertaining to higher education and college advising policies and procedures.

The academic system is an essential student support system in the higher educational institutions in Oman. The effectiveness of the practical implementation of the academic system was evaluated using a survey questionnaire with a total of 23 questions assessing the experience of the advisees with academic advising, their overall GPA, and satisfaction, in addition to their personal information. The questionnaire has been subjected to validity and relatability tests on a pilot sample of 10 respondents. The results showed a high internal consistency of 97.4 percent based on Cronbach’s alpha. This indicates that the questionnaire is valid and reliable to measure what it is intended to measure.

A stratified random sampling has been employed to represent the population of advisees and academic advisors in the College. The sample was chosen in proportion to the number of advisees in the various programs. The final sample size for the survey included 128 respondents after the rejection of 11 incomplete questionnaires. The sample for the survey was determined based on this formula.

Where

n = sample size

Z = level of precision, i.e., 1.96 for a 5 percent level of significance.

P = Academic advice prevalence (0.52 from a random cohort).

R = nonresponse rate (5 percent)

D = margin of error (8.5 percent)

The study employed descriptive analysis to assess the experience of the advisees with the advising process at the CBFS. Moreover, some nonparametric tests, such as the Chi-square test and Spearman rank correlation, have also been used to validate the hypotheses of the study. Factor analysis has also been used to identify the factors influencing the effectiveness of the advising process.

Empirical findings

Table shows that most of the advisees who participated in the survey are female, with a share of 68.8 percent, while males represented only 31.3 percent. This is due to the large female population in the College. The advisees’ level of study shows that 28.9 percent belong to the foundation and the first year. About 31 percent participated in the fourth year, while 24.2 percent and 16.4 percent are from the third and second levels, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of the advisees (N = 128)

Source: Authors calculation

Concerning the areas of specialisation of the advisee, the results indicated that more than 64 percent of the advisees are enrolled in accounting, auditing, and finance programs. Those enrolled in business have a share of 19.5 percent, higher national diploma (HND) holders have a share of 12.5 percent, and those enrolled in Islamic finance have the smallest share (3.1 percent).The latter is a relatively new program in higher education in Oman.

The number of visits an advisee makes to the academic advisor ranges from none to three or more. Approximately 20.3 percent of advisees do not consult their advisors. Almost 48 percent of the advisees make one visit to their respective advisors, usually at the start of the semester. 22.7 percent make two visits, and 9.4 percent make more than three visits. The last categories usually involve those who have issues with their academic progression.

Source: Authors calculation

From Table , it is observed that all the results of the views, except statement 12, are statistically significant per the Chi Square test (P-value<0.05), indicating that there is a clear pattern in the views of the advisees toward the degree of agreement with the given statements of academic advising. For example, more than 52 percent agree and strongly agree that advisees know their responsibilities, as compared to 20 percent who disagree. For the second statement, about 41 percent agree and strongly agree that their academic advisor is receptive to their needs and concerns, while 35.2 percent are neutral, and 24.2 percent disagree and strongly disagree with the statement.

Table 2. Views of the advisees on the academic advising system in % (N = 128)

Regarding the accessibility of the academic advisor, 40.6 percent of the advisees admitted that advisors are accessible during regular office hours or by appointment, compared to 23 percent who disagree and 36.7 percent who neither agree nor disagree. About 56 percent of the advisees agree and strongly agree that academic advisors are knowledgeable about academic courses, programs, and procedures, while more than half of the advisees agree and strongly agree that their academic advisors help them understand and be informed about academic requirements. Similarly, more than 40 percent of the advisees agree and strongly agree that they are freely talking with academic advisors, and advisors provide accurate and appropriate information about their interest areas and major, referring them to the appropriate person, office, or resource when necessary.

Only 38.3 percent of advisees agree or strongly agree that academic advisors care about them as individuals; 38.3 percent admit that advisors help advisees understand their own abilities, interests, and potential.41 percent of the advisees are neutral about the statement that academic advisors facilitate their self-understanding of their abilities, interests, and potential.

Approximately 45 percent of advisees said their academic advisor encouraged their growth and development as students and individuals, while 26 percent disagreed. Regarding the academic advisor discussing academic goals and progress toward these goals, 39.1 percent agree and strongly agree, 29.7 percent are neutral, and about 31 percent disagree and strongly disagree with that statement. The result of this statement is not significant (P-value>0.05), indicating that there is no clear pattern concerning the role of the advisor in discussing the academic goals and progress toward these goals. In contrast, approximately 34% indicated that their academic advisor discusses their long-term and career goals, compared to 29.7 percent who disagree and strongly disagree and 36.7 percent who are neutral. These are two weak points that should be addressed to enhance the effectiveness of the advising system at the College.

More than 50 percent agree and strongly agree that their academic advisor respects their right to make their own decisions, while 29 percent are neutral, and about 20 percent disagree with that. About 42 percent of the advisees see the advising as a cooperative effort, and 44 percent claim that their academic advisors have a positive and constructive attitude toward working with advisees. A friendly relationship between student and advisor should be required by the advisees during their course, and this will provide stronger communication and proper solutions for their academic-related issues. A solid training program in those areas is highly important. This seems to be absent from advising training and professional development programs, as observed by McGill et al. (Citation2020).

Regarding the effectiveness of the advising process, 39.1 percent of the advisees demonstrated that their advisors have worked effectively with them, while 28 percent disagree and strongly disagree, and 33 percent are neutral. The same conclusion has been reported by Umar (Citation2017), who is studying academic advising at the College of Engineering (A’Sharqiyah University). He demonstrated that 50 percent of the academic advisors and advisees are of the view that the process of academic advising is ineffective and needs further improvement.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.942, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at 0.000, indicating high sampling adequacy and a justification for proceeding with factor analysis, as shown in Table .

Table 3. Factor Analysis for components of academic advising

Factor analysis led to two factors, accounting for 72.9 percent of the cumulative variance. This represents a high percentage, indicating that the model captures the most important factors impacting the effectiveness of academic advising in the College of Banking and Financial Studies (CBFS). The results of the rotated components of the effectiveness of the academic advising matrix are shown in Table and interpreted as follows: the first factor, “advisor-induced factors,” including knowledge and attitude towards the advising process. This consists of items 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17. This factor explains 66.3 percent of the total variance.

Table 4. Rotated components of the academic advising matrix

Advisees appear to believe that advisors are encouraging their growth and development. They facilitate their own understanding of their abilities, interests, and potential. They also provide them with accurate information about their areas of interest and major. Moreover, advising creates an opportunity for the advisees to discuss their academic goals and progress toward these goals. All these are important factors influencing the effectiveness of the academic advising process at the College.

The second factor, “advisee-induced factors,” related to the advisee’s attitude and behavior. This consists of two items: 2 and 9. This factor accounts for 6.6 percent of the sum of squared loadings. Awareness among the advisees of their responsibility in the advising process and the frequency of their visits to the academic advisors seem to be influential factors in the effectiveness of the academic process.

The analysis has shown that the effectiveness of academic advising is a two-step process. Part of it is induced by the advisee, and part of it is induced by the academic advisor, and any policy related to academic advising needs to take these two factors into consideration if it is to be effective.

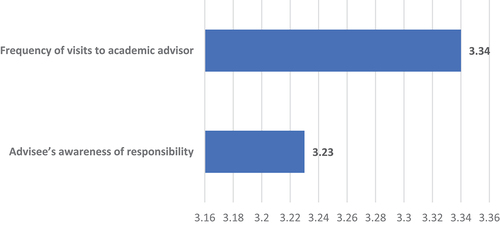

Table shows that the visit frequency to academic advisor has more average impact on advising effectiveness as compared to the responsibility awareness of advisee, with an average of 3.34 and 3.23 points respectively. Alpha Cronbach indicates that these two items have high internal consistency and reliability for advisee-induced factor, amounting to 68 percent. Figure shows the average effectiveness of advisee-induced factors.

Figure 1. Average effectiveness of advisee-induced factors.

Table 5. Average and reliability of the advisee-induced factors

The average effectiveness and reliability analysis for the adviser-induced factors is shown in Figure . Visit frequency to the academic advisor has a greater average impact on advising effectiveness as compared to the advisee’s awareness of his or her responsibilities, with an average of 3.34 and 3.23 points, respectively.

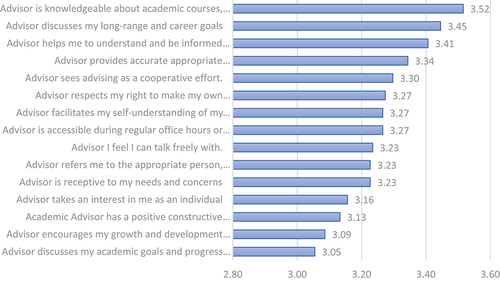

Table reveals a high level of internal consistency among the items of the advisor-induced factors, with Alpha Cronbach’s coefficient amounting to 96 percent, indicating high reliability. The advisor’s knowledge about academic courses, programs, and procedures has the highest mean score (3.52). Followed by the advisor’s discussion of the advisee’s long-range and career goals (3.45), helping the advisees understand and be informed about academic requirements (3.41). Following that, providing accurate and relevant information about the advisees’ interests and major (3.34); and viewing the advising process as a collaborative effort (3.30).

Table 6. Average and reliability of the advisee-induced factors

Among the weakest areas identified are the advisor’s lack of discussion of academic goals and progress toward these goals with the advisee (3.05). Followed by a lack of encouragement with the advisee’s growth and development as a student and individual (3.09). Then there was the advisor’s lack of a positive, constructive attitude toward working with advisees (3.13). Finally, there is the advisor’s lack of interest in the advisee (3.16). These areas should be addressed to enhance the effectiveness of academic advising in higher education in Oman. Figure provides the average effectiveness of advisor-induced factors.

Figure 2. Average effectiveness of advisor -induced factors.

Table shows the relationship between the advisees’ performance and their satisfaction with the academic advising. The result showed a positive link between the two variables, with a Spearman correlation coefficient of 65.5%. This result is supported by many findings (Azianti et al., Citation2021; Paul & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015; Soden, Citation2017). In fact, internal statistics of the College showed that the retention rate increased from 83.96 percent in 2014/2015 (when academic advising was introduced) to 93.91 percent in 2015/2016, reaching 89.8 percent in 2018/2019.

Table 7. Relationship between student performance and satisfaction with academic advising

For further details on the discussion, based on the various feedback received, a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis has been attempted and shown in Figure . The analysis takes into account both internal and external factors affecting the academic advising system at the chosen higher education institution.

Figure 3. SWOT analysis for academic advising system.

It is expected that the SWOT analysis would further help the College while strategizing future action in academic advising.

Advisors’ perspectives on the academic advising system

To understand the perspectives of advisors who were part of the implementation of the new academic advising (AA) system, three formal interviews were conducted with teaching faculty involved in academic advising at CBFS. Based on the input, the following can be summarized:

There was no second opinion from any advisees on the relevance of academic advising (AA) to colleges, for it can advise students about learning styles, how to choose subjects as per their abilities, and can direct them to the most sensible route towards graduation. Most advisors opined that students mostly rely on their advisors for guidance related to selecting modules throughout their academic journey, especially when it comes to prerequisites for a program. Also, if students find difficulties in their studies, the advisor will have to mentor them to overcome their challenges and act as a bridge between them and their lecturers. However, there was a view that not much change in students’ attitudes was seen, and perhaps only a very small percentage of students followed the advisors’ suggestions.

The areas for improvement in the system include the lack of continuity with the same students over a period; this is in addition to the challenges in addressing the need for a high number of advisees. Besides these, some advisees are not responsive to follow-up meetings, especially when advisors allocate a formal time. A solution to some of these issues was suggested by designing a more user-friendly application to be integrated with the learning management system (LMS) or enterprise resource planning (ERP) system for both advisors and advisees.

Further views expressed were these: “Work overload for advisors is raised by many as a major challenge in the system.” Academic staff already have their teaching commitments. As opposed to foreign universities, in this part of the world, the advisors are loaded with teaching hours and other related academic duties like examinations, marking, etc., which probably leaves them with very little time. A strong view is that there should be a timed academic advising hour in a week so that the advisors’ work is accounted for as per duty time. There was a view that AA should be done by trained administrative staff.

An alternate view was expressed by a few, who suggested that academic advising could be linked with promotion and reward by the management. Some expressed the desire that each faculty member do the AA task sincerely in letter and spirit, rather than as a process, so that AA would be more meaningful. Moreover, advisors should have access to all academic records, the financial implications of allotting subjects, and a bit of cultural sensitivity about the student’s background.

Discussion and implications

The qualitative focus on student-centric learning in higher educational institutions is evaluated by the effective implementation of academic advising systems. Academic advising was considered one of the most important methods for increasing student achievement (Holland et al., Citation2020). The analysis report concentrated on the concepts of the academic advisory system and their implementation in the College of Banking and Financial Studies. As a result, a survey was conducted at the College to assess the effectiveness and challenges of the academic advising system adopted.

When compared to the literature review studies, advisees from higher education institutions (HEIs) in Oman have a similar view on the limited effectiveness of the system indicated by Tuttle (Citation2000) even after two decades and by Umar (Citation2017) more recently. The current study also reveals consistency in the approach of those involved in the system, regardless of the model used in academic advising mentioned by Peno et al. (Citation2016). One of the difficulties in the implementation of the advising system is the advisors’ preoccupation and workload, which negatively impacted the advising (Cobb et al., Citation2018).

Academic advising is multifaceted and plays a crucial role in a student’s life at college. If the students believe that they are underserved or are not receiving the proper services and guidance, it could risk their perception of the educational institution. Many students prefer a continuous and progressive relationship with their advisors, which will develop as they progress through their academic lives, as supported by the findings of Grites (Citation1979), Ford and Ford (Citation1989), and Frost (Citation1991). Higher educational institutions in Oman should consider re-evaluating the system currently in place (which is traditional and prescriptive). For effective academic advising, the institution should provide the necessary training and support to the advisors to meet the students’ perceptions and prioritize the academic advising activity.

However, it is to be noted that there is a strong positive link between academic advising and student retention, which underscores the purpose behind the systems across universities worldwide (Azianti et al., Citation2021; Paul & Fitzpatrick, Citation2015; Soden, Citation2017). The study has found that nearly half of the academic advisors have a positive and constructive attitude toward working with the advisees, and the benefits of communication lead to solving issues. This ratio is deemed to be enhanced with the right training and professional development programs, as stated by McGill et al. (Citation2020). Moreover, for a sustainable system of academic advising, the cooperation of both advisors and advisees is essential.

Conclusion

Quality academic advising is key to student success and retention, and the role of the faculty advisor is of paramount importance in the process. The study looked into the effectiveness of academic advising in Oman’s higher education institutions, with a particular focus on the College of Banking and Financial Studies. The perceptions of the advisees and the advisors on academic advising have been assessed, and key challenges have been identified with the help of a survey that included 128 advisees in addition to in-depth interviews with three advisors.

The study revealed some gaps in academic advising and that there is no complete endorsement of the academic advising system in the College. This was identified because the roles and responsibilities of the advisors have not been clearly defined and rewarded by the higher educational institutions in Oman. Both advisees and advisors have expressed concern about the effectiveness of the existing academic advising system. To improve the effectiveness of the academic system in higher education in Oman, awareness of the importance of the academic system among advisees should be enhanced, particularly during induction programs, so that advisees can be more committed to meeting their advisors regularly. Moreover, the roles and responsibilities of the advisors should be clearly defined, and advising should be linked to promotion and salary so that faculty view it as a legitimate professional responsibility. Other motivations include recognition of outstanding advisors through a certificate of merit, an “Advisor of the Year,” and allowing advisors to attend national and international conferences to support professional development that reinforces advisor growth. A more user-friendly application should be integrated with the learning management system (LMS) or enterprise resource planning (ERP) system to facilitate academic advising and the exchange of information among advisors, advisees, and other stakeholders in the process. Recent automated academic advising systems, such as rule-based expert systems, recommender systems, and chatbot-based systems, could be considered.

This study has some limitations: the sample included one government institution, suggesting that faculty and advisees across various types of higher education institutions perceive academic advisory support in the same way would overstate the findings. Replicating this quantitative study at a variety of institution types may reveal different perceptions and challenges to the academic advising process. The study could be extended by additional investigation into the factors that account for the most variance in student advisor satisfaction and exploring the relationships between servant leadership behaviors, student advisor satisfaction, and retention through graduation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the College of Banking and Financial Studies (CBFS) for the research grant provided for completing the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Binu James Mathew

Dr Binu James Mathew is an Asst Professor and former Deputy Head, (Academic), Quality Assurance Unit, at College of Banking and Financial Studies (CBFS), Muscat, Oman.

Dr Mathew has over 27 years of teaching, training and research experience in English language and general management subjects. Previously, he worked with the University of Mumbai, and Institute of Management Studies, Mumbai.

He holds a PhD from IIT Bombay, MA and M.Phil. (Research) in English, MBA in Customer Relationship Management and is a Cambridge University CELTA-qualified teacher. He is also a certified trainer conducting Corporate Training courses in the soft skills areas that include Business Communication, Customer Service, Emotional Intelligence & Teamwork.

He has widely presented papers at several international conferences and published his research papers in national and international journals.

References

- Aaishah, J., Alagappan, D., Fikry, W., Zainal, S., Hadi, F., Shaharuddin, N., & Abd Rahman, N. (2021). The Effectiveness of Academic Advising on Student Performance. International Journal of Advanced Research in Future Ready Learning and Education, 25(1), 20–19.

- Al-Ghamdi, A., Al-Ghuribi, S., Fadel, A., Al-Aswadi, F., & AL-Ruhaili, T. (2012). An expert system for advising postgraduate students. (IJCSIT) International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technologies, 3(3), 4529–4532.

- Amin Kuhail, M., Al Katheeri, H., Negreiros, J., Seffah, A., & Alfandi, O. (2022). Engaging Students with a Chatbot-Based Academic Advising System. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2074645

- Azianti, I., Liyana, R., Herda, I., & Noor, A. (2021). Students’ Satisfaction towards Academic Advising Service. Asian Journal of University Education, 17(3), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.24191/ajue.v17i3.14497

- Campbell, S., & Nutt, C. (2008). Academic advising in the new global century: Supporting student engagement and learning outcomes achievement. Peer Review, 10(1), 4–7.

- Chan, Z., Chan, H., Chow, H., Choy, S., Ng, K., Wong, K., & Yu, P. K. (2019). Academic advising in undergraduate education: A systematic review’. Nurse Education Today, 75(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.01.009

- Cobb, C., Zamboanga, B., Xie, D., Schwartz, S., Meca, A., & Sanders, G. (2018). From advising to mentoring: Toward proactive mentoring in health service psychology doctoral training programs. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 12(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000187

- Drake, J., Jordan, P., & Miller, M. (Eds.). (2013). Academic advising approaches: Strategies that teach students to make the most of college. Jossey-Bass.

- Fong, S., & Biuk-Aghai, R. P. (2009). An automated university admission recommender system for secondary school students. In The 6th International Conference on Information Technology and Applications (ICITA 2009), Cairns, Australia. ISBN: 978-981-08-3029-8.

- Ford, J., & Ford, S. (1989). A caring attitude and academic advising. National Academic Advising Journal, 9(2), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.12930/0271-9517-9.2.43

- Frost, S. H. (1991, November). Academic advising for student success: A system of shared responsibility. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 3. School 43 of Education and Human Development, the George Washington University. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED340274

- Gordon-Starks, D. (2015). Academic Advising is Relationship Building. NACADA Academic Advising Today. (accessed on 12 June, 2022). Available online at: https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Academic-Advising-is-Relationship-Building.aspx

- Grites, T. J. (1979). Academic advising: Getting us through the eighties (AAHE-ERIC Higher Education Research Report No. 7). American College Testing Program.

- Habley, W., Bloom, J., & Robbins, S. (2012). Increasing persistence: Research-based strategies for college student success. Jossey-Bass.

- Holland, C., Westwood, C., & Hanif, N. (2020). Underestimating the Relationship Between Academic Advising and Attainment: A Case Study in Practice. Frontiers in Education, 5(145), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00145

- Iatrellis, O., Kameas, A., & Fitsilis, P. (2017). Academic advising systems: A systematic literature review of empirical evidence. Education Sciences, 7(4), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7040090

- Kramer, G. L. (Ed.). (2003). Faculty Advising Examined: Enhancing the Potential of College Faculty Advisors. Anker Publishing Co.

- Kuhtmann, M. S. (2004). Mission impossible? Advising and institutional culture. NACADA Journal, 24(1–2), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.12930/0271-9517-24.1-2.99

- Loucif, S., Laila, G., & Joao, N. (2020). Considering students’ abilities in the academic advising process. Education Sciences, 10(9), 254–267. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090254

- Mangundu, J. (2022). Higher education institutional innovation: An analysis of challenges to e-academic advising during emergency remote teaching. South African Journal of Information Management, 24(1), a1569. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajim.v24i1.1569

- Mastrodicasa, J. (2001). But you teach chemistry, how can you advise me at orientation? Paper presented at the annual conference of the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators, Seattle, WA, March, 17–21.

- McGill, C., Heikkila, M., & Lazarowicz, T. (2020). Professional development, performance expectations and academic advisors’ perceptions of relational skills: A sequential explanatory mixed methods study. New Horizon in Adult Education and Human Research Development, 32(4), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/nha3.20296

- Mottarella, K., Barbara, A., & Kara, C. (2004). What do students want in advising? A policy capturing study. NACADA Journal, 24(1–2), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.12930/0271-9517-24.1-2.48

- Mu, L., & Kevin, F. (2019). Effective advising: How academic advising influences student learning outcomes in different institutional contexts. The Review of Higher Education, 42(4), 283–1307. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2019.0066

- Paul, W., & Fitzpatrick, C. (2015). Advising as servant leadership: Investigating student satisfaction. NACADA Journal, 35(2), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.12930/NACADA-14-019

- Peno, K., Mangiante, E., & Kenahan, R. (2016). Mentoring in formal and informal contexts. Information Age Publishing.

- Shaibany, S.(2016). Higher education student dropout rate in Oman is a cause for concern. Opinion, Times of Oman, 23rd January, 2016. http://timesofoman.com/article/75995

- Soden, S. (2017). Perceptions of Academic Advising and Student Retention. Dissertations, 224. https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/dissertations/224

- Thumiki, V. (2019). Student Dropout from Foundation Program at Modern College of Business & Science, Sultanate of Oman. International Journal of Higher Education, 8(5), 118–133. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v8n5p118

- Tuttle, K. (2000). Academic advising. New Directions for Higher Education, 2000(111), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.11102

- Umar, T. (2017) Academic advising, a case study of A’Sharqiyah University-Oman. In: Academic Advising Practice; 21 - 22 Nov 2017, Rustaq College of Education, Oman. (Unpublished). https://eprints.kingston.ac.uk/id/eprint/48523/

- Winston, R., Miller, T., Ender, S., & Grites, T. (Eds.). (1984). Developmental academic advising: Addressing students’ educational, career, and personal needs. Jossey-Bass.

- Yarbrough, D. B. (2002). Collaborative writing: Perspectives on theory, practice, and product. In L. J. Gurak & M. M. Lay (Eds.), Research in Technical Communication (pp. 57–84). Ablex Publishing.