Abstract

Chinese international students compose the largest group of full-tuition-paying students globally and are important to hosting destinations both culturally and financially. However, the obstructed international mobility caused by COVID-19 has changed their international applications. As the world gradually resumes its previous mobility level, it is important to comprehend what pull factors can effectively attract students for marketing purposes. This quantitative research re-examines the established pull factors considered and valued by prospective Chinese international students and their parents and discovered that (1) a combination of five to six factors can be sufficient for Chinese students to decide on an overseas destination, (2) cost, global rankings, and Chinese employment prospects have become the most substantial factors in destination choices, (3) opportunities for immigration and overseas employment are no longer significant, and (4) students and parents view international education with different interpretations. The marketing implications are discussed.

1. Introduction

1.1. The number of Chinese international students

Chinese people have a long history of pursuing international education, which can arguably be traced back to 1842 and the Westernization movement carried out by the Qing Dynasty. Since then, a substantial number of Chinese students have pursued the advancement of their knowledge in foreign countries. More recently, the continuing pursuit of overseas education was made possible by the reform and opening-up policy of 1978, when China and its people fundamentally realized nationwide deficiencies in vast disciplines, which provoked a booming demand for pursuing international knowledge (Liu, Citation2016; Mok, Citation2016, 2023).

Such enthusiasm continues today. As evidenced by the figures provided by the Ministry of Education of China, 6,560,600 Chinese people obtained an international degree between 1978 and 2019, especially in the tertiary education sector (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2020). Based on this sheer volume, China has become the top exporting country of international students (Choudaha, Citation2017), contributing to approximately a quarter of the world’s international students (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Citation2020).

Chinese international students, in their vast volume, have brought substantial benefits to the hosting countries and universities. One of the most evident is the considerable income that these students can provide for the hosting destinations (Bound et al., Citation2020; Ruiz, Citation2014). America, Australia and the United Kingdom, three of the top destination choices of Chinese overseas students have reported a net gain in the international education industry of 44 billion dollars (Anderson, Citation2016; Bureau of Economic Analysis, Citation2019), 16 billion dollars (Australian Education International, Citation2012), and 14 billion dollars (British Council, Citation2012), respectively. For universities, some studies have found that massive layoffs and budget deficiencies have already occurred (Hegarty, Citation2014) due to a low enrollment rate of full-tuition-paying international students (Welch, Citation2022a). Thus, the benefits of maintaining an adequate number of overseas students are arguably critical for the economy of a multitude of universities and countries (Marginson & Xu, Citation2022; Redden, Citation2019).

1.2. The influence of COVID-19 on the international education of Chinese students

Although the largest number of international students originate from China, the COVID-19 pandemic has heavily obstructed the mobility of Chinese students in their pursuit of international education in many ways. As reported, 23.74% of C9Footnote1 Chinese university students expressed a willingness to study abroad before the pandemic (Lin, Citation2020). This number, however, decreased by half to 11.49% in 2020 due to the immobility induced by the pandemic (Lin, Citation2020).

Such a downward trend in pursuing the international education of Chinese international students is influenced by two mobility factors. On the one hand, the sudden aversion to international education is a partial result of the obstruction of international outbound mobility caused by massive global lockdowns at the peak of the pandemic. According to a white paper on Chinese overseas students published by one of the major organizations in the industry, New Oriental (Citation2021) reports that due to lockdown policies, (1) Seventy-nine percent of Chinese students failed to travel abroad to study, (2) Sixty percent of the students had to unwillingly study online, and (3) seventeen percent of applicants were exploring alternative means for overseas education. Such funding has been backed by international research as well. According to Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) research (Citation2021), forty-seven percent of international students decided to postpone their plans to study abroad, and sixteen percent of these chose to forfeit current offers and reapply to safer countries for overseas study.

On the other hand, the inbound immobility of Chinese students has greatly hindered decisions regarding studying abroad. Due to frequent emergency flight fuses, plane tickets to China were not only scarcely available but also extremely expensive (Deng et al., Citation2021). According to reports (e.g., S. S. Chen, Citation2022), a ticket for a one-way trip from New York to Guangzhou can be as high as 25,000 USD, approximately seven times the normal fare. In addition, an even harsher reality is that these tickets are in such high demand that a significant proportion of travelers are not able to obtain them. In other words, even if students intend to pay such a high price, they may still be “trapped in double bind” (Ma & Miller, Citation2021, p. 1598).

1.3. Newest policies facilitating international mobility from and to China

Fortunately, the abovementioned difficulties have been addressed to a certain extent. Not only have many countries adopted more flexible approaches for pandemic prevention regarding international travel (e.g., Australian Government Department of Home Affairs, Citation2022; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2022). From the Chinese perspective, policies have shifted from strict zero tolerance to coexistence with the COVID-19 virus, effective January 2023. This shifting means that prospective Chinese international students do not have to consider the limitations of flight availability and quarantine-related inconveniences when making study abroad decisions.

Because of the most recent policy-related changes, the volume of Chinese students who pursue overseas education in the higher education sector is likely to regain its previous glory. Since more Chinese students will resume or choose to study abroad, and because of the benefits these international students bring to institutions, a re-examination of the factors that attract Chinese international students to certain destinations could provide timely insights into the marketing for higher education regarding the modifications of the significance of existing attractive factors in the eyes of decision-pending Chinese international students due to the global epidemic.

2. Literature review

2.1. The pull factors of destination decisions

Some scholars argue that both push and pull factors can act as variables influencing international education decisions (e.g., Bodycott, Citation2009). In academia, the push and pull model has also been adopted to understand why Chinese students choose to study at a particular nation or university (e.g., Dimmock & Ong Soon Leong, Citation2010; Li & Bray, Citation2007; Yang, Citation2007). However, researchers (e.g., Bodycott & Lai, Citation2012; C. F. Lee, Citation2014; Dimmock & Ong Soon Leong, Citation2010) also acknowledge that the push factors are the social, political, and economic developments in students’ home countries that motivate them to pursue education abroad. On the other hand, pull factors are the elements that induce students to select one destination over others (Mazzarol et al., Citation2001; S. W. Lee, Citation2017). In other words, push factors are the reasons for international students to pursue overseas education and have little to factor in destination choice. Therefore, as a paper that intends to determine the elements for destination decisions, only the pulling dimension of the push and pull model is adopted because the push factors are less relevant for an analysis aiming to provide marketing insights for higher education destinations aiming to appeal to international students (as they are only decisive in terms of the willingness to pursue overseas education, not the choice of destination).

The push and pull factor model was proposed by Mazzarol and Soutar (Citation2002) after surveying 2,485 students in four different countries and regions with the majority of research subjects being Chinese. This study based the selection of pull factors for examination on this model with supplements from more recent and influential studies that also focus on Chinese international students. Mazzarol and Soutar (Citation2002) proposed four main categories of factors that heavily influence destination choices for Chinese students: “knowledge and awareness of host”, “recommendations from friends and relatives”, “cost issues”, and “environment”.

Specifically, (Mazzarol & Soutar, Citation2002) discovered that Chinese students are drawn to those countries and institutions that (1) have great educational quality, (2) have a strong reputation, (3) have plentiful employment opportunities, (4) provide students with the chance to live in a more developed region, and (5) have potential immigration opportunities. In other words, the classical pull factors that attract Chinese overseas students are likely to be “highly ranked quality of education”, “good reputation of cities, institutions, and programmes”, “having employment opportunities at the destination”, “better economic development of the destinations”, and “potential of immigration”, which are all examined items of this study.

The findings of Mazzarol and Soutar (Citation2002) have been supported and supplemented by other research regarding why Chinese international students favor certain destinations for international education. For example, in Canada, J. M. Chen (Citation2016) discovered that Chinese students favor (1) internationally reputable universities and cities, (2) countries that provide abundant employment and immigration opportunities, and (3) institutions recommended by friends and family. Moreover, in Britain, a study by Cebolla-Boado et al. (Citation2018) pointed out that Chinese students’ destination choices are highly correlated with the (1) pedagogical level, (2) cultural and language immersive experience, and (3) employment opportunities at the destination.

Such findings have also been confirmed by Chinese researchers in the field.

For example, Zhou and Li (Citation2012) argued that when Chinese people seek tuition overseas, the consideration factors include (1) economic development, (2) the language used in tuition and daily life, (3) employment and immigration policies, and (4) the cost of tuition and living in the destination.

Congregating on findings in the literature, the pull factors that have been cross-verified by highly quoted studies on the reasons for Chinese international students to choose one destination over others are (1) the reputations and locations of institutions, (2) the employment and immigration opportunities, (3) the economic development of the destination, (4) recommendations from family and friends, (5) language in use, and (6) the cost of the overseas experience, which will be used for the questionnaire design.

2.2. The influence of COVID-19

However, the COVID-19 epidemic has shifted the world in a way that has hardly been witnessed before. Massive lockdowns, closure of nonessential facilities, disruptions to international travel and shipping, significant declines in global financial investment (World Trade Organization, Citation2020), and a global unemployment phenomenon (Gruszczynski, Citation2020) represent only a few of the symptoms of COVID-19 on the international scale, under which educational institutions are severely impacted as well (Evans Darrell et al., Citation2020). Although these entities have adopted active pedagogical countering measures to combat restrictions on international mobility, such as hosting online virtual classrooms (Evans Darrell et al., Citation2020; Longhurst et al., Citation2020), the effectiveness of such measures, compared to face-to-face teaching, is arguably suboptimal at best (Franchi, Citation2020; Srinivasan, Citation2020).

Moreover, the decisions of Chinese overseas students regarding cross-border education have been influenced by these inconveniences caused by international and pedagogical restrictions relating to the coronavirus. One difference that has already emerged regarding the choice of destinations relates to the application process.

According to reports from two major Chinese organizations that assist Chinese students in their international applications (EIC Education, Citation2021; New Oriental, Citation2021), because of the inconvenience associated with mobility in 2020, Chinese students now have strong tendencies to apply to multiple destinations so that they have a better chance of avoiding unexpected travel restrictions and social lockdowns. Thus, it is evident that the pandemic has influenced international students’ destination decisions, which may render the existing pull factors ineffective.

2.3. Research objectives and questions

To restate the aim of this research, this paper intends to re-examine the influence of pre-COVID-19 pull factors in the pandemic coexisting phase for the consideration of destination institutions regarding marketing strategies for attracting the largest group of full-tuition-paying students in these difficult times.

Bearing this research focus in mind, the initial hypothesis is proposed:

(1) Each of the identified pull factors is still influential for the destination decisions in the Chinese context

Furthermore, this research also acknowledges that major personal decisions in China are heavily influenced by family members (J. Pan & Chen, Citation2014; Wang, Citation2001), which could correspond with the pull factor of “recommendations of family and friends”, which has been identified by some researchers (e.g., S. W. Lee, Citation2017). Thus, this study separately examines the influence of pull factors for students and parents, which specified the research hypotheses in the following way:

(2) Each of the identified pull factors is still influential for students to make destination decisions.

(3) Each of the identified pull factors is still influential for parents to make destination decisions.

(4) Each of the identified pull factors is similarly influential for students and parents to make destination decisions.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research design

To understand which pull factors are still considered significant by Chinese international students and their parents when making destination decisions, we devised a questionnaire based on the pull factors that have been identified in past literature. The key composition of the questionnaire is a Likert scale section (with 1 being the least important and 7 the most important) that was designed to rate the importance of each factor. To limit the possibility of misunderstanding the examined factors, not only was the questionnaire presented to respondents in Chinese but also some of the general and open-to interpretation terms were decomposed into more specific items. For example, the factor “cost of overseas experiences” can be a congregation of two main subitems, “cost of tuition” and “cost of living”. Thus, to gain limit the possibility of overlooking either factor, the “cost of overseas experiences” is represented by “cost of tuition” and “cost of living” in the questionnaire. A detailed description between representative items and push factors is shown in Table :

Table 1. Pull factors and corresponding subfactors

3.2. Data collection

From November 2022 to January 2023, data were collected through three channels of questionnaire distribution: online survey platforms, study abroad agencies, and universities’ global cooperation programmes.

Through this combination, the research team was able to collect 1,335 responses, with the majority obtained through agencies and university programmes (58.13% and 36.03%, respectively), where a high number of prospective international students (and their parents) can be found. Among the 1,335 responses, 1099 were from students and 236 were from parents.

3.3. Profiles of respondents

Of the student respondents, 61% were females, and 39% were males, which is similar to the gender ratio provided by titans of the industry (New Oriental, Citation2021). Among both genders, 398 of them had the intention to study abroad for their bachelor’s degrees, 565 were interested in obtaining their master’s degrees, and 91 subjects were considering acquiring their doctorates, which makes the sample representative.

The parent respondents, on the other hand, were almost exclusively the parents of prospective bachelor’s students or master’s students (133 and 49, or 72.28% and 26.63%, respectively), with only two exceptions (1.09%).

3.4. Data handling

Before recording the collected data, 97 reports were omitted due to blanks in answers, leaving 1,054 valid surveys for the student group and 184 for the parent group.

4. Findings

4.1. Factors considered by students

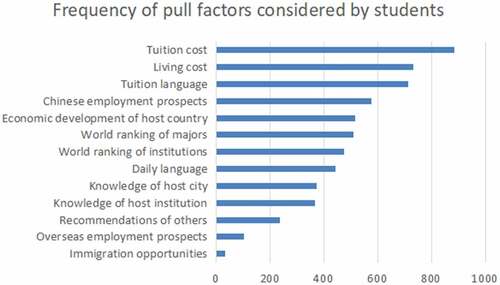

After a descriptive statistical analysis, it was observed that when choosing a destination for international education, over half of the Chinese students in the sample considered “tuition cost” (83.87%), “living cost” (69.55%), “tuition language” (67.74%), and “Chinese employment prospects” (54.84%) to be the primary factors. In addition, they also take “economic development of host country” (48.95%), “world rankings of majors” (48.39%), “world rankings of institutions” (45.16%), “daily language” (41.94%), “knowledge of host city” (35.48%), “knowledge of host institution” (34.89%) and “recommendations from others” (22.58%) into account. However, they are less likely to regard “overseas employment prospects” (9.68%) or “immigration opportunities” (3.23%) as important when choosing destinations.

Detailed data can be seen in Table and Figure .

Table 2. Pull factors considered by international students

A frequency-based top-down illustration of pull factors that students (instead of parents) deem important. The factor rating, top-down, is “Tuition cost”, “Living cost”, “Tuition language”, “Chinese employment prospects”, “Economic development of host country”, “World ranking of majors”, “World ranking of institutions”, “Daily language”, “Knowledge of host city”, “Knowledge of host institution”, “Recommendations of others”, “Overseas employment prospects”, and “Immigration opportunities”.

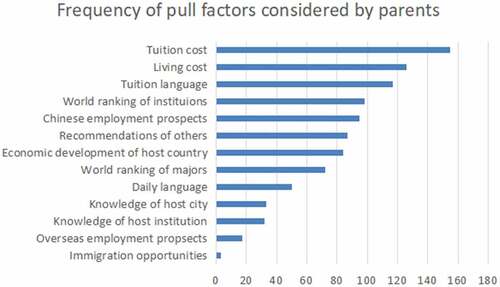

4.2. Factors considered by parents

For the parents, the data reveal results with minor differences compared to the student group. From the most frequent to the least frequent, the factors are “tuition cost” (84.24%), “living cost” (68.48%), “tuition language” (63.59%), “world ranking of institutions” (53.26%), “Chinese employment prospects” (51.63%), “recommendations of others” (47.28%), “economic development of host country” (45.65%), “world ranking of majors” (39.13%), “daily language” (27.17%), “knowledge of host city” (17.93%), “knowledge of host institution” (17.39%), “overseas employment prospects” (9.24%) and “immigration opportunities” (1.63%). The figures can be found in Table and Figure .

Table 3. Pull factors considered by parents of international students

A frequency-based top-down illustration of pull factors that parents (instead of students) deem important. The factor rating, top-down, is “Tuition cost”, “Living cost”, “Tuition language”, “World ranking of institutions”, “Chinese employment prospects”, “Recommendations of others”, “Economic development of host country”, “World ranking of majors”, “Daily language”, “Knowledge of host city”, “Knowledge of host institution”, “Overseas employment prospects”, and “Immigration opportunities”.

4.3. Significance level of pull factors for the two groups

The student respondents and the parent respondents do not appear to value the pull factors similarly. Even though they do agree on the importance of certain factors, namely, “Living cost”, “Tuition language”, “World ranking of institutions”, “World ranking of majors”, and “Oversea employment prospects”, the cognition of the importance of other factors are significantly different. The detailed comparison can be seen in Table .

Table 4. Comparison of factor importance between the student group and the parent group

5. Discussion

5.1. A combination of five to six factors is decisive enough for the destination decision

As displayed in Tables , the consideration ratio, which is the likeliness of individuals in the sample considering a certain pull factor, totals 566.30% and 526.62% for the student group and the parent group, respectively, meaning that the 1,054 student samples and the 184 parent respondents are likely to deliberate a combination of 5.6630 and 5.2662 factors for destination choices, respectively. In other words, for individuals in this study, a combination of five to six satisfactory pull factors can be decisive for the final choice. Therefore, understanding the top five to six considerations can be paramount for the marketing choices of international higher education organizations. Taking a closer examination, for students, the five to six primary considerations, in decreasing importance, are likely to be “tuition cost”, “living cost”, “tuition language”, “Chinese employment prospects”, “world ranking of majors”, and “world ranking of institutions”. For the parents, the most likely five to six factors of deliberation are (in decreasing order of importance) “tuition cost”, “living cost”, “tuition language”, “world ranking of institutions”, “Chinese employment prospects”, and the “recommendation of others”.

5.2. Critical factors shared in both groups

The five to six main pull factors influencing both groups illustrate a certain resemblance. Both students and parents value cost issues, global educational rankings, tuition languages and prospects for Chinese employment. In other words, Chinese international students, as well as their stakeholders, favor destinations that could allow them to obtain an education with elite colleges and programmes at an affordable price that could put the students at an advantage for better employment in China.

The abovementioned commonalities in consideration factors are the partial results of the COVID-19 pandemic. First, it has been discovered that cost issues are of tremendous significance in destination decisions, especially tuition costs.

Indeed, international tuition costs have demonstrated a rapidly rising trend (Palvia et al., Citation2018; Tomlinson, Citation2017), with reports of a 41.2% increase in the last decade in certain countries (Alexander, Citation2021). After the pandemic, such costs may become even heavier for international students. Due to the economic crisis influenced by COVID-19, the Board of Governors at the University of Guelph opted to retain the same tuition fees for domestic students while raising them by 10% to 15% for foreign students (Keung, Citation2020). Under such circumstances, it would be inevitable for international students to reconsider their destination choices based on the expenditure they must face.

Second, Chinese international students continued to show a preference for English-medium programmes. Starting from the second or third grade (if not before), Chinese students commence their study of English, as stipulated by provincial or municipal governments. On the eve of college admission, they will have learned English for no less than 10 years, which intuitively explains such a preference.

However, due to the global trend of opting for English as a tuition medium at multilingual universities (Dafouz & Smit, Citation2016), such a preference can no longer be construed as significant when marketing institutions with Anglophone environments.

However, due to the “ranking orientated mindset” (Mok et al., Citation2021, p. 8), students from China still favor universities with high world rankings, as it is widely believed by Chinese graduates and recruiters that the ranking of a school can heavily influence the employment success rate (Lv et al., Citation2014). Thus, although Chinese international students would consider cost issues to be more important, subject and institution rankings can still be effective pulling factors for attracting them.

5.3. Some factors are no longer important

This study also distinguishes three pull factors that cannot be construed as important, which include employment prospects at the destination, immigration opportunities, and the recommendations of friends and family.

The lesser amount of consideration given to employment and immigration in the host country corresponds with the figures for returning overseas students released by the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (Citation2020). Including the 580,000 Chinese students who returned in 2019, over 4.23 million Chinese international students had returned after the completion of their overseas tuition since 1978 (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2020). The returning trend is especially found in the year 2021 (Dong et al., Citation2021), with the number of those who went back to China after international tuition had doubled comparing to the figure of 2019. These data not only signify that the majority of Chinese international students opt to return to China but also demonstrate that Chinese students largely do not intend to pursue overseas employment and/or immigration, which could explain the lack of significance for these two factors.

Another explanation for this phenomenon is political. With the growing influence of the new geo-political realities emerging from the “new cold war” between China and the ally led by the USA, recent research has suggested that there has been a reverse trend of Chinese international students choosing to return to China in recent years against the worsening relations between China and some major powers in the West (Mok et al., Citation2022; Welch, Citation2022b).

The recommendations by friends and family represent another factor that has little importance for students. Although 47.28% of parents in this study noted the influential power of recommendations, only 22.58% of students would even consider recommendations from others when making destination decisions. Thus, unlike some other research (e.g., Jon et al., Citation2014; S. W. Lee, Citation2017), this study did not find the power of endorsement to be of great significance. However, this is not to claim that students no longer need information input for decision making. It only suggests that friends and family play less significant roles comparing to the past.

As it involved quantitative research, this study could not provide detailed insights regarding the lack of significance of the recommendation factor. However, it is plausible to comprehend such an occurrence from the perspective of the shifting family power dynamic. Traditionally, with each family housing multiple children,

Chinese families were mostly patriarchal, with fathers at the center of decision-making (Kang, Citation2011; Song, Citation2020). In other words, the children had to listen to their fathers’ opinions when making their decisions regarding studying abroad.

However, because of the one-child policy that began in 1979, the family axis has slowly shifted to the child (Song, 2012). Many Chinese parents even become obedient to their children’s every need (Ren, Citation2006). In other words, Chinese parents are now likely to support whatever destination decisions are made by their offspring, which decreases the significance of recommendations for the student group.

5.4. Students and parents emphasize different aspects of the international education experience

Although there were similarities in what the students and parents reported in terms of the factors they primarily considered, they also assigned values to many pull factors in a statistically disparate manner, which reflects a difference in their priorities relating to the experience.

The students, on the one hand, tend to value “Chinese employment prospects” and “daily language” more than their parents. It appears that they may contemplate international education as a type of investment (Altbach & Knight, Citation2007), not an expenditure. Therefore, it is the return that matters. By living in an Anglophone environment and using English for daily communication, they can enhance their ability to use this global language (Crystal, Citation2003; L. Pan, Citation2015) so that they can pursue better employment opportunities (L. Pan & Block, Citation2011). As Tran et al. (Citation2020) stated, “Considering employers” emphasis on graduates’ communication skills, investment in English language capital is a critical factor for international graduates’ professional achievement’ (p. 504).

The parents, on the other hand, appear to favor “tuition cost”, “knowledge of host city”, “knowledge of host institution”, “economic development of host country”, and the “recommendation of others”. These factors are generated by a combination of considerations. First, the “tuition cost”, along with the “living cost”, reflects the negative impact of COVID-19 on Chinese families. Not only have over 5 million Chinese families lost their jobs (Zhang, Citation2020), but over 18 million Chinese enterprises have also reported significant financial losses as a result (Dhar, Citation2020). Therefore, as the providers for students, parents have inevitably been put in a more difficult position.

moneywise.

Second, “knowledge of host city”, “knowledge of host institution”, and the “recommendation of others” can be interpreted as having the same origin, which is the high involvement level of Chinese parents in the education of their children (Cheung & Pomerantz, Citation2011). Such involvement is so common in China that Chinese scholars are no longer researching the level of involvement or its effects but studying how to effectively involve Chinese parents in daily pedagogy and administration at different levels of schools (e.g., X. Gao & Xue, Citation2020). Arguably, this phenomenon is derived from the values of Confucianism. Mencius, who perfected Confucianism, proposed the notion that “the foundation of a nation is the families”, which has influenced Chinese people for thousands of years. In China, the basic units of society are the families (Saich, Citation2017), not individuals (Jin et al., Citation2005). Chinese family members take pride in helping each other and would be culturally condemned if they failed to bring value to those they are supposed to take care of. Influenced by this cultural cognition, parents, as the caretakers of children, must think about major decisions for their children, international education included. However, such overseas environments are unfamiliar settings for parents, which means that they must rely on the information provided by trustworthy sources to familiarize themselves with the destination that they would like to advise for their children.

For the favored factor of the “economic development of the host country”, some scholars have identified preferences such as immigration and/or employment opportunities (e.g., Gong & Huybers, Citation2015; Tran et al., Citation2020). However, this interpretation is now less accurate, as evidenced by the number of Chinese international students returning to China (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2020). The preference for a nation with a better economy is possibly the result of seeking a better education. The relationship between higher education and economic development has been known for many decades (e.g., Rokicki et al., Citation2020; Spring, Citation1998). In the last few years, with the global economy evolving to become knowledge-based (Marginson, Citation2010), the quality of higher education has become interdependent with economic development (Krstić et al., Citation2020). In other words, economic development can be a reliable indicator of the quality of higher education, attracting Chinese students and their parents.

5.5. Recommendations to enhance institutions’ appeal

Based on the previous discussion, this study proposes two methods to appeal to full-tuition-paying international students and Chinese students in particular. These two approaches are (1) offering financial aid and (2) emphasizing the return on investment.

Because COVID-19 caused a global economic downturn, the household finances of most new and current tertiary students have been negatively impacted, which may mean that they require more financial aid than they anticipated (SimpsonScarborough, Citation2020). Some may argue that this would weaken the income that destinations receive, but the provision of financial assistance for foreign students has long been proven to be beneficial for both students and universities. In 1993, Citation1993) discovered that practices such as direct financial aid and indirect discounts on tuition had been successful in increasing the number of enrollments, which could generate far better revenue. Under the most recent economic downturn, such measures have received satisfactory results regarding overall enrollment (Bamberger et al., Citation2020); some students even stated that financial assistance was “the most critical factor in their decision to study abroad” (Abbas et al., Citation2021, p. 4). Thus, applicable financial assistance for boosting Chinese international enrollment may be a necessity.

Because Chinese international students treat international education as an investment, another recommendation for institutions is to market the investment return based on alumni data. As evidenced by the returning trend of Chinese students (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2020; Z. P. Gao, Citation2012), the majority of Chinese students return to their home country for employment. However, it has also been repeatedly noted that international education can no longer guarantee a job offer back in China (e.g., Jia, Citation2012; Wei & Zeng, Citation2014), which corresponds with the high level of consideration regarding Chinese employment prospects observed in this research. Should the institutions be able to work with Chinese study abroad agencies to advertise figures such as the Chinese employment rate, the average salary of graduates, and the Chinese career paths of the institution’s alumni, they would find more interest in enrollment.

Analyzing the findings generated from the present research from a broader political economy perspective, we must also note the motivations of Chinese students for overseas study would also be affected by other contextual factors, such as the impact of the new geo-political realities on choices of study destinations. Based on a survey on Asian students’ overseas learning preferences, Mok and Zhang, in their recent research, reflect upon the future of international higher education from geopolitical and sociopsychological perspectives (Mok & Zhang, Citation2021). After the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis, racial and cultural discrimination against Asians has become increasingly popular as a social movement in some major societies in the West, which has led to the #STOPASIANHATE movement (Touraine, Citation2002; Cabral, Citation2021). The anti-Asian movement or more broadly cultural discrimination and racism that Asian students experienced during the COVID-19 crisis emerged in 2020 and has also affected the intentions of Chinese and Asian students to learn overseas (Mok and Mok, Citation2022, Citation2023). Hence, a better contextualization of the present studies against the broader political economy context would enable us to develop an even better understanding of the students’ desires and choices of overseas study destinations.

6. Conclusions and recommendations for future research

China has always been one of the top sender country of international students (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Citation2020). From both cultural exchange and institutional finance perspectives, it is important to retain timely knowledge regarding what attracts Chinese international students to certain studying destinations. However, although many studies have looked at the destination choices students in the higher education sector during COIVD-19 (e.g., Mok, Citation2022), little has examined the pull factors after this global pandemic. This research, with a sample size over 1,000, provides timely knowledge to what are and what are not significant for the destination decision of Chinese international students in the co-existence phase of COVID.

This work also has certain limitations that suggest ideas for further analyses. First, as a quantitative study, this paper considers the what, not the how. In other words, students’ perceptions regarding these new priorities cannot be answered by this research; however, these factors are no less significant for designing marketing methods to attract Chinese international students, which yields a demand for further qualitative research.

In addition, as evidenced by the changes in application behavior mentioned in the article (EIC Education, Citation2021; New Oriental, Citation2021), it is anticipated that the COVID-19 pandemic has more influence over the destination choice of Chinese international students beyond the traditional pull factors. Thus, observational research regarding application behaviors along with several actual applications may be a beneficial supplement to studies regarding the destination decisions of Chinese international students.

Finally, all data were collected in Shandong province, where both Confucius and Mencius were born. In terms of famous people originating from Shandong, a substantial number of ministers and lords over thousands of years can be observed, but no kings or queens can be observed. This cultural distinction from the rest of the states in China is perhaps influential regarding the fact that the research subjects value employment. As evidenced by first-hand observation, international students from other provinces majoring in commerce would discuss which businesses they would like to operate prior to their graduations. Those from Shandong, on the other hand, would exchange information about different employment positions, especially governmental jobs. Therefore, similar research into other provinces could assist in understanding whether the employment factor is influential for all Chinese students as a whole or only for Shandong residents.

Disclosure statement

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Notes

1. C9 is the alliance of the top nine Chinese universities. It is normally interpreted as the Chinese equivalent of the Ivy League.

References

- Abbas, J., Alturki, U., Habib, M., Aldraiweesh, A., & Al-Rahmi, W. M. (2021). Factors affecting students in the selection of country for higher education: A comparative analysis of international students in Germany and the UK. Sustainability, 13(18), 10065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810065

- Alexander, L. (2021, May15). Undergraduate international tuition fees to increase by an average of 2.1 percent next year: Student groups advocate for lower international, deregulated program tuition. The Varsity. https://thevarsity.ca/2021/05/15/undergraduate-international-tuition-fees-to-increase-by-an-average-of-2-1-per-cent-next-year/

- Altbach, P. G., & Knight, J. (2007). The internationalization of higher education: Motivations and realities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3–4), 290–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307303542

- Anderson, S. (2016). International students who started billion‐ dollar companies. International Educator. https://www.nafsa.org/sites/default/files/ektron/files/underscore/iejulaug16fro ntlines.pdf

- Australian Education International. (2012 , November). Research snapshot. https://aei.gov.au/research/Researchnapshots/Documents/Export%20Income%202011.pdf

- Australian Government Department of Home Affairs. (2022). Entering and leaving Australia. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/covid19/entering-and-leaving-australia

- Bamberger, A., Bronshtein, Y., & Yemini, M. (2020). Marketing universities and targeting international students: A comparative analysis of social media data trailsTeaching in Higher Education, 25(4), 476–492.

- Bodycott, P. (2009). Choosing a higher education study abroad destination: What mainland Chinese parents and students rate as important. Journal of Research in International Education, 8(3), 349–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240909345818

- Bodycott, P., & Lai, A. (2012). The influence and implications of Chinese culture in the decision to undertake cross-border higher education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16(3), 252–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315311418517

- Bound, J., Braga, B., Khanna, G., & Turner, S. (2020). A passage to America: University funding and international students. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 12(1), 97–126. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20170620

- Bowen, W. G., & Breneman, D. W. (1993). Student aid: Price discount or educational investment? The Brookings Review, 11(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.2307/20080361

- British Council. (2012, September). The British Council makes a major contribution to prosperity and growth. https://www.britishcouncil.org/about/prosperity-and-growth

- Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2019) . Table 2.2 U.S. trade in services, by type of service and by country or affiliation. U.S. Department of Commerce.

- Cabral, S. (2021, May21). Covid ‘hate crimes’ against Asian Americans on rise. BBC News. May 20, 2022, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-56218684

- Cebolla-Boado, H., Hu, Y., & Soysal, Y. N. (2018). Why study abroad? sorting of Chinese students across British universities. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 39(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2017.1349649

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). International travel. The United States of America. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/international-travel/index.html#print

- Chen, J. M. (2016). Three levels of push-pull dynamics among Chinese international students’ decision to study abroad in the Canadian context. Journal of International Students, 7(1), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v7i1.248

- Chen, S. S. (2022, August15). Shi Wan Yuan Dou Qiang Bu Dao Yi Zhang Ji Piao? Shu Qi Hui Guo Wei He Zhe Me Nan [One hundred thousand yuan cannot buy a plane ticket? Why is it so difficult to return for the summer]. China Business Network. https://www.163.com/dy/article/HER0JFHE0519DDQ2.html

- Cheung, C. S. S., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2011). Parents’ involvement in children’s learning in the United States and China: Implications for children’s academic and emotional adjustment. Child Development, 82(3), 932–950. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01582.x

- Choudaha, R. (2017). Three waves of international student mobility (1999–2020). Studies in Higher Education, 42(5), 825–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1293872

- Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language. Cambridge University Press.

- Dafouz, E., & Smit, U. (2016) Toward a dynamic conceptual framework for English-medium education in multilingual university settings. Applied Linguistics, 37(3), 397–415.

- Deng, J. Y., Bai, J. J., Lu, Y. Y., Lu, Z. Y., & Yang, Q. W. (2021). Xin Xing Guan Zhuang Bing Du Fei Yan Yi Qing Qi Jian Zhong Guo Liu Xue Sheng Hui Guo Ge Li Xin Li Zhuang Kuang Fen Xi Yu Gan Yu Ping Jia [The interference assessment and psychological analysis for returning Chinese overseas students during the Covid-19 pandemic]. Guang Dong Yi Xue, 10, 1161–1166. https://doi.org/10.13820/j.cnki.gdyx.20210894

- Dhar, B. K. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on Chinese Economy. Economic Affairs, 9(3/4), 23–26.

- Dimmock, C., & Ong Soon Leong, J. (2010). Studying overseas: Mainland Chinese students in Singapore. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 40(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920903155666

- Dong, N., Dou, Y., & Wang, J. (2021). Dashuju Fenxi 2021 Nian Liuxue Guiguo Jiuye Xuesheng Shou Chao Baiwan, Shutong Haigui Jiuye “Zhonggengdu” Xu Chixu Jingzhun Fali [Big data reveals that more than 1 million students came back after receiving international education in 2021, there is a need for precise efforts to dredge the “middle-segment jam” of their employment]. National Development and Reform Commission. https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/wsdwhfz/202109/t20210907_1296152.html

- EIC Education. (2021) . Zhong Guo Liu Xue Shi Chang 2021 Pan Dian Yu 2020 Zhan Wang. [The inventory of 2021 and outlook of 2022 for the Chinese international education market] EIC Education.

- Evans Darrell, J. R., Huat, B. B., Wilson Timothy, D., Smith Claire, F., Nirusha, L., & Wojciech, P. (2020). Going virtual to support anatomy education: A STOP GAP in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Anatomical Sciences Education, 13(3), 279–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1963

- Franchi, T. (2020). The impact of the covid‐ 19 pandemic on current anatomy education and future careers: A student’s perspective. Anatomical Sciences Education, 13(3), 312. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1966

- Gao, Z. P. (2012). Hai Wai Ke Ji Ren Cai Hui Liu Yi Yuan De Ying Xiang Yin Su Fen Xi [The factor analysis of returning willingness of overseas technology talents]. Ke Yan Guan Li, 8, 98–105. https://doi.org/10.19571/j.cnki.1000-2995.2012.08.013

- Gao, X., & Xue, H. P. (2020). Jia Ting Bei Jing, Jia Zhang Can Yu He Chu Zhong Sheng Ying Zi Jiao Yu Can Yu Lai Zi CEPS2015 Shu Ju De Shi Zheng Yan Jiu [A study of family background, parental involvement and shadow education involvement of middle school students a CEPS2015 empirical study data]. Jiao Yu Xue Shu Yue Kan, 9, 3–11+71. https://doi.org/10.16477/j.cnki.issn1674-2311.2020.09.001

- Gong, X., & Huybers, T. (2015). Chinese students and higher education destinations: Findings from a choice experiment. Australian Journal of Education, 59(2), 196–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944115584482

- Gruszczynski, L. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and international trade: Temporary turbulence or paradigm shift. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 11(2), 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.29

- Hegarty, N. (2014). Where we are now –the presence and importance of international students to universities in the United States. Journal of International Students, 4(3), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v4i3.462

- Jia, H. (2012). Hai Wai Liu Xue Gui Guo Ren Yuan Jiu Ye Nan Cheng Yin Fen Xi Yu Jian Yi Ji Yu Bei Jing Shi De Diao Cha Fen Xi [The analysis and recommendation for hard-to-employ returning overseas students an investigation in Bei Jing]. Xian Dai Jing Ji Tan Tao, (11), 37–41.

- Jin, G., Liu, Q., & Lam, L. W. (2005). From ‘republicanism’ to ‘democracy’: China’s selective adoption and reconstruction of modern Western political concepts (1840-1924). History of Political Thought, 26(3), 468–501.

- Jon, J. E., Lee, J. J., & Byun, K. (2014). The emergence of a regional hub: Comparing international student choices and experiences in South Korea. Higher Education, 67(5), 691–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9674-0

- Kang, L. G. (2011). Cong Fu Quan Dao Ping Quan Zhong Guo Jia Ting Zhong Quan Li Bian Qian Wen Ti Tan Tao [From patriarch to equality an exploration on power transition in Chinese families]. Shan Xi Qing Nian Gan Bu Guan Li Xue Yuan Xue Bao, (1), 91–94.

- Keung, N. (2020, May28). The University of Guelph is hiking tuition for international students amid COVID-19 – and they aren’t happy. Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2020/05/27/the-university-of-guelph-is-hiking-tuition-for-international-students-amid-covid-19-and-they-arent-happy.html

- Krstić, M., Filipe, J. A., & Chavaglia, J. (2020). Higher education as a determinant of the competitiveness and sustainable development of an economy. Sustainability, 12(16), 6607. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166607

- Lee, C. F. (2014). An investigation of factors determining the study abroad destination choice: A case study of Taiwan. Journal of Studies in International Education, 18(4), 362–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315313497061

- Lee, S. W. (2017). Circulating east to east: Understanding the push–pull factors of Chinese students studying in Korea. Journal of Studies in International Education, 21(2), 170–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315317697540

- Li, M., & Bray, M. (2007). Cross-border flows of students for higher education: Push–pull factors and motivations of mainland Chinese students in Hong Kong and Macau. Higher Education, 53(6), 791–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-005-5423-3

- Lin, J. (2020). Guo Nei Ding Jian Da Xue Ben Ke Bi Ye Sheng Jiu Ye Qing Kuang Ji Qu Shi Fen Xi [Employment situation and trend analysis for Chinese undergraduates from elite universities an investigation based on employment quality reports of C9 universities from 2017 to 2019]. Gao Deng Jiao Yu Xue Bao, 43(3), 11–18+85.

- Liu, Y. (2016). Xin Zhong Guo Chu Guo Liu Xue Zheng Ce Bian Qian Yan Jiu 1949-2014 [The changes regarding International Education Policy of People’s Republic of China 1949-2014]. [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Northeast Normal University. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFDLAST2017&filename=1016109888.nh

- Longhurst, G. J., Stone, D. M., Dulohery, K., Scully, D., Campbell, T., & Smith, C. F. (2020). Strength, weakness, opportunity, threat (SWOT) analysis of the adaptations to anatomical education in the United Kingdom and republic of Ireland in response to the covid‐ 19 pandemic. Anatomical Sciences Education, 13(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1967

- Lv, H. Y., Du, J., & Liu, Z. G. (2014). Gao Xiao Bi Ye Sheng Jiu Ye Lv De Ying Xiang Yin Su Fen Xi [An analysis of influential factors regarding employment rate of higher education graduates]. Da Qing Shi Fan Xue Yuan Xue Bao, 3, 93–97. https://doi.org/10.13356/j.cnki.jdnu.2095-0063.2014.03.025

- Ma, H., & Miller, C. (2021). Trapped in a double bind: Chinese overseas student anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Communication, 36(13), 1598–1605. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1775439

- Marginson, S. (2010). Higher education in the global knowledge economy. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(5), 6962–6980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.05.049

- Marginson, S., & Xu, X. (2022). The ensemble of diverse music: Internationalization strategy and endogenous agendas. In S. Marginson & X. Xu (Eds.), Changing Higher Education in East Asia (pp. 1). Bloomsbury.

- Mazzarol, T., & Soutar, G. N. (2002). ‘Push‐ pull’ factors influencing international student destination choice. International Journal of Educational Management, 16(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540210418403

- Mazzarol, T., Soutar, G. N., & Thein, V. (2001). Critical success factors in the marketing of an educational institution: A comparison of institutional and student perspectives. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 10(2), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1300/J050v10n02_04

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2020 , December). Statistics on Chinese learners studying overseas in 2019. http://en.moe.gov.cn/news/press_releases/202012/t20201224_507474.html

- Mok, K. H. (2016). Transnationalizing and internationalizing higher education in China: Implications for regional cooperation and university governance in Asia. In Y. C. Oh, G. W. Shin, & R. J. Moon (Eds.), Internationalizing higher education in korea (pp. 47–72). Asia-Pacific Research Center.

- Mok, K. H. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and international higher education in East Asia. In S. Marginson & X. Xu (Eds.), Changing higher education in East Asia (pp. 225–246). Bloomsbury.

- Mok, K. H. (2023). China’s three-pronged approach managing the new geo-politics in international higher education. In K. H. Mok, Globalizing China: Social and governance reforms (pp. 29–51). Routledge.

- Mok, K. H., & Mok, W. C. E. (2023). Health hazard and symbolic violence: The impact of double disturbance on international learning experiences. In A. Hou (Ed.), Reimagining higher education, system reform and quality management. Springer.

- Mok, K. H., Xiong, W., Ke, G., & Cheung, J. O. W. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on international higher education and student mobility: Student perspectives from mainland China and Hong Kong. International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101718

- Mok, K. H., & Zhang, Y. L. (2021). Remaking international higher education for an unequal world. Higher Education Quarterly, 76(2), 230–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12366

- Mok, K. H., Zhang, Y. L., & Bao, W. (2022). Brain drain or brain gain: A growing trend of Chinese international students returning home for development. In K. H. Mok (Ed.), Higher Education, innovation and entrepreneurship from comparative perspectives. higher education in Asia: Quality, excellence and governance (pp. 245–267). Springer.

- New Oriental. (2021 , May). 2021 Zhong Guo Liu Xue Bai Pi Shu [ The 2021 white paper of Chinese overseas studies]. http://www.199it.com/archives/1269816.html

- Palvia, S., Aeron, P., Gupta, P., Mahapatra, D., Parida, R., Rosner, R., & Sindhi, S. (2018). Online education: Worldwide status, challenges, trends, and implications. Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 21(4), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/1097198X.2018.1542262

- Pan, L. (2015). English as a global language in China. English Language Education, 2, 90366.

- Pan, L., & Block, D. (2011). English as a ‘global language’ in China: An investigation into learners’ and teachers’ language beliefs. System, 39(3), 391–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.07.011

- Pan, J., & Chen, G. H. (2014). Jia Ting Jue Ce, She Hui Hu Dong, and Lao Dong Li Liu Dong [Family decision-making, social assistance and labor mobility]. Jing Ji Ping Lun, 3, 40–50+99. https://doi.org/10.19361/j.er.2014.03.004

- Quacquarelli Symonds. (2021). Navigating a complex global higher education climate amidst crisis. QS Report. https://www.qs.com/portfolio-items/international-student-survey-2021/

- Redden, E. 2019 Number of enrolled international students drops Inside Higher Ed. http://ir.westcliff.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Number-of-Enrolled-Intern ational-Students-Drops.pdf

- Ren, Z. X. (2006). Bu Liang Qin Zi Hu Dong Yu Bing Tai Jia Ting Jie Gou Dui Ji Ge Zhong Guo Wen Ti Jia Ting De Pou Xi [Unhealthy parent‒child interaction and abnormal family structures a dissection of a few Chinese family problems]. Shan Dong Da Xue Xue Xue Bao (Zhe Xue She Hui Ke Xue Ban), (5), 122–125.

- Rokicki, T., Perkowska, A., Klepacki, B., Szczepaniuk, H., Szczepaniuk, E. K., Bereziński, S., & Ziółkowska, P. (2020). The importance of higher education in EU countries in achieving the objectives of the circular economy in the energy sector. Energies, 13(17), 4407. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13174407

- Ruiz, N. G. (2014, August). The geography of foreign students in US higher education: Origins and destinations. Global Cities Initiative, https://www.immigrationresearch.org/system/files/geography_of_foreign_students.pdf

- Saich, T. (2017). Governance and politics of China. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- SimpsonScarborough. (2020). Higher Ed & COVID-19: National student survey. https://impact.simpsonscarborough.com/covid19/

- Song, K. (2020). Cong Zhong Guo Jia Ting San Jiao Jie Gou Zhong Quan Li Bian Qian De Shi Jiao Jie Du Fu Mu De Er Tong Guan [Interpreting the parents’ view of children from the perspective of power transition in the triangle structure of Chinese families]. Jiao Yu Dao Kan (Xia Ban Yue), 11(second half monthly), 88–91.

- Spring, J. (1998). Education and the rise of the global economy. Routledge.

- Srinivasan, D. K. (2020). Medical students’ perceptions and an anatomy teacher’s personal experience using an e-learning platform for tutorials during the Covid-19 crisis. Anatomical Sciences Education, 13(3), 318–319. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1970

- Tomlinson, M. (2017). Student perceptions of themselves as ‘consumers’ of higher education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(4), 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1113856

- Touraine, A. (2002). The importance of social movements. Social Movement Studies, 1(1), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742830120118918

- Tran, L. T., Rahimi, M., Tan, G., Dang, X. T., & Le, N. (2020). Poststudy work for international graduates in Australia: Opportunity to enhance employability, get a return on investment or secure migration? Globalization, Societies and Education, 18(5), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2020.1789449

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2020). Education: From disruption to recovery. UNESCO Publishing. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

- Wang, S. B. (2001). Zhong Guo She Hui De Qiu Zhu Guan Xi Zhi Du Yu Wen Hua De Shi Jiao [The seek and help relationship in Chinese society a perspective of system and culture]. She Hui Xue Yan Jiu, 4, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.19934/j.cnki.shxyj.2001.04.001

- Wei, H. Y., & Zeng, X. Q. (2014). Hai Wai Liu Xue Gui Guo Ren Yuan Jiu Ye De Wei Guan Ying Xiang Yin Su De Shi Zheng Yan Jiu [An empirical study of microinfluential factors for employment of returning overseas students]. Zhong Guo Xing Zheng Guan Li, (10), 84–86.

- Welch, A. (2022a). Australia’s China challenge. International Higher Education, 109(Winter), 44–45.

- Welch, A. (2022b). A plague on higher education? COVID, Camus and Culture Wars in Australian universities. Higher Education Quarterly, 76(2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12377

- World Trade Organization. (2020, March). Services trade barometer. https://bit.ly/39womJC

- Yang, M. (2007). What attracts mainland Chinese students to Australian higher education (version 1). CQUniversity. https://hdl.handle.net/10018/5964

- Zhang, H. (2020). The influence of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic on family violence in China. Journal of Family Violence, 37(5), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00196-8

- Zhou, X. L., & Li, X. (2012). Guo Ji Liu Xue Sheng Gao Deng Jiao Yu De Fa Zhan Xian Zhuang, Qu Shi Ji Dui Wo Guo De Qi Shi [The developmental status quo and trend of international students at higher education and its revelation for China]. Dang Dai Zhi Ye Jiao Yu, (7), 94–96.