?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Literature on the modern university suggest that top-ranked world-class universities are the ideal, and emerging nation-states should establish such institutions. Appearing at the top in international university rankings has become the aim as it guarantees attraction and retention of top talent. This study investigated the status of a university that was established to be world-class. To contribute to research and literature on the flagship university in emerging nations, the views of 321 professional administrative staff on whether Nazarbayev University (NU) is a top university were captured. First, a survey questionnaire was administered to 321 respondents. The second stage of the study involved 16 semi-structured interviews. Quantitative and qualitative data indicated positive experiences and perspectives among the respondents. These findings demonstrate that a university should be relevant to its society and not necessarily appear at the top in international rankings to be considered good and valuable by its people.

1. Introduction

One of the challenges of modern higher education policy and practice has been to link university business with national expectations (Tian & Liu, Citation2019; Udam & Heidmets, Citation2013). The idea of a good university (Connell, Citation2019; Hazelkorn & Gibson, Citation2019), flagship university (Douglas, Citation2016b; Marginson, Citation2018) or a global/world-class university (Karran & Mallinson, Citation2018; Salmi, Citation2009) is not universally agreed with different understandings from stakeholders including the state, employers, the community, students, and academics (Altbach, Citation2004). Kazakhstan attained independence when the former Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 (Engvall & Cornell, Citation2015). Nazarbayev University (NU) was established to be a model modern research university in 2010, “four years after the first President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev, announced in his annual address to the nation his plan to create the first research and world-class university in the country (Institutional Evaluation Programme, Citation2017, p. 4). The university, located in Kazakhstan’s capital city, Astana, was also established to become a “global level research university” (OECD, Citation2017), a “prestigious international university there to create a unique academic environment” (Nazarbayev, Citation2006), an Oxford or Harvard of Central Asia (Koch, Citation2015), and is described as Kazakhstan’s flagship academic institution (NU, Citation2023). It is structured along with international university policies and practices, which Koch (Citation2015) refers to as the domestication of elite international education. For example, the university has partnership arrangements with world-class Western universities, such as Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, the London School of Economics, the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the University of Cambridge, and the University of Pennsylvania (Koch, Citation2015; Starr & Engvall, Citation2017). As a model institution, NU was mandated to ensure that the lessons of NU’s experience are transferred to and understood by other institutions (educational reform leadership), to develop and maintain academic excellence and to develop a faculty-led program of world-class research (research excellence) among other key responsibilities (NU Brochure, Citation2019, p. 1)

Universities all over the world provide advanced education for the academic profession, policymakers, and public and private sector professionals involved in the modern complex globalised economies (Altbach & Salmi, Citation2011) of the 21st century. Furthermore, universities play a key societal role by serving as cultural institutions, centres for social commentary and criticism. To Pusser (Citation2006), the university is the place where open conversation and collaboration in a public space, where critiques could be generated in pursuit of the public good, and it is there “to serve society, not to agree with it” (Connell, Citation2019, p. 173). University education can help Kazakhstan, like other countries, to become more globally competitive by developing a skilled, productive human capital and spreading new ideas and technologies. These can be achieved if there is highly qualified faculty, excellence in research results, the high quality of teaching and learning, high levels of government and non-government sources of funding, international and highly talented students, academic freedom, well-defined autonomous governance structures, and well-equipped facilities for teaching, research, administration, and often student life (Altbach & Salmi, Citation2011, p. 3). To establish such universities, governments can upgrade a few existing universities that have the potential to excel, encourage several existing institutions to merge and transform into a new university, or governments can decide to create new world-class universities from scratch (Salmi, Citation2013). Kazakhstan adopted the last approach and created Nazarbayev University (NU) in 2010. Case studying NU, this paper aims to critique the idea of a world-class university and argue that nation-states should concentrate on establishing good universities that serve the communities and be not concerned with international comparisons via ranking regimes. Consequently, in this paper, NU is referred to as a flagship university for Kazakhstan. The views of local/Kazakh citizens who are professional administrative staff members are utilised to address the following key research questions:

Is NU serving the interests of the local Kazakhstani community?

Can NU be described as a top exemplary university (flagship) in Kazakhstan?

Local administrative staff were utilised because at NU, 74% of academic staff were international and 94% of professional administrative staff were local Kazakhstan citizens. The locals were the participants because of their expert knowledge of the country, the education system and experiential knowledge of NU.

2. Literature review

2.1. Kazakhstan university education: a conspectus

The first higher education institutions in Kazakhstan were established in the 1920s. According to Ahn et al. (Citation2018), by 1932, Kazakhstan had 20 universities that focused on a limited number of disciplines such as agriculture, veterinary and medical sciences. As Kazakhstan was part or a colony of the Soviet Union ruled from Moscow (Sharipov, Citation2021), the rapid development of higher education during the 1930s was accompanied by other government programs that included collectivisation (forced consolidation of individual households into collectives or cooperatives), a period when at least 38% (1 450 000 people) of the population died due to the 1931 to 1933 famine (Pianciola, Citation2001). The period also witnessed the repressions of the Kazakh intelligentsia when representatives of the Alash movement and other well-educated Kazakhstani citizens were killed (Tanatarova, Citation2015). There were also difficulties in supplying universities with qualified applicants because of the poor quality of the secondary school education system.

The after-war decades were characterised by economic and demographic growth due to tselina, cultivation of virgin lands, and many Russians, Ukrainians, and other ethnicities moved to Kazakhstan (Sharipov, Citation2021). There was also the deportation of “unreliable” nations (Saparbekova et al., Citation2014) like Koreans, Germans, Caucasian nations, and others to Kazakhstan (Saparbekova et al., Citation2014). These demographic movements changed Kazakhstan’s socio-ethnic composition, and higher education witnessed what Sharipov (Citation2021) refers to as the early beginnings of internationalisation. In 1989, the late stages of the Soviet period, the number of higher education institutions reached 55 with 287 400 students (Ahn et al., Citation2018) out of a population of 16.5 million, meaning only 1.7% pursued higher education (Zimovina, Citation2003). Also, the period had very few comprehensive universities as the majority were narrow, specialising in engineering or pedagogical institutions. Other notable features of the higher education system were centralised, with universities reporting to several ministries in some cases. To Froumin et al. (Citation2014), Kazakhstan’s higher education aimed at preparing ideologically loyal citizens and educated specialists who could support the extraction of raw materials and industry. Furthermore, the iron curtain policy (Sharipov, Citation2021) meant that any exchanges of ideas or free movement of people was only between the 15 states of the Soviet Union, with only Russia and Ukraine having permission to exchange students and faculty with other communist countries and allies.

After gaining independence in 1991 (Pomfret, Citation2014), Kazakhstan embarked on restructuring and modernising higher education in line with well-established international standards. The Law on Higher Education in 1993 allowed the establishment of private institutions in Kazakhstan. Overall, in the 1990s, 114 higher education institutions were established. During the 1997–1997 academic year, more than half of the institutions (50.7%) were already private (OECD, Citation2007). The privatization of state universities led to the creation of joint stock companies. It this scheme the government shares the ownership of a university with other stakeholders. Joint stock companies have the legal status of privately owned universities and although still subject to government regulation, they enjoy greater autonomy in decision making and financial management and more flexibility in terms of governance. Any private company or individual can buy the shares of corporate universities (Bayetova & Robertson, Citation2019; Sagintayeva & Kurakbayev, Citation2015). In many cases, private universities were just diploma factories that provided degrees in return for money, and three decades into independence, the Ministry of Education and Science is still terminating some universities’ licences (Sharipov, Citation2021). From around the year 2000, the privatisation of state universities was encouraged and the private sector became involved in the provision of higher education (Azimbayeva & Harford, Citation2017), leading to massification in line with international trends. Foreign universities’ branch campuses are also increasing in numbers, further showing the promotion of the privatisation of university education.

Another notable change was introducing a 4-year bachelor’s degree from the 5-year Soviet-era degree in 2000. Further changes were introduced to align university education with international practice and institutional structures (Piven & Pak, Citation2006). In 2010, Kazakhstan signed the Lisbon Convention of the Bologna Process (BP), becoming its 47th signatory and the first Central Asian country to do so (Kazinform, Citation2010; MoES, Citation2010). This promoted the internationalisation of university education through faculty and student mobility through programs like Erasmus Mundus and Jean Monnet (see https://www.inform.kz/en/eu-supports-education-more-than-30-kazakh-students-gained-erasmus-scholarships-in-2019_a3561080). In 2017, the number of international students in Kazakhstan universities was 13,898 or 2.8%. Compared to 2016, international students increased only by 8.3% (MoES, Citation2018, p. 118). To facilitate student mobility, the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) was adopted. In 1998, Kazakhstan signed an agreement with Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia permitting degree equivalence recognition, thereby increasing student and graduate mobility opportunities between the four countries (Poletaev & Rakisheva, Citation2011). Furthermore, students were encouraged to study abroad through initiatives such as the Bolashak scholarship program (Sagintayeva & Jumakulov, Citation2015). The legislation was passed to support research, for example, the Law on Science in 2001, Law on Innovative Activities in 2003, Patent Law in 2003, and the Law on Support of Innovative Activities in 2006.

A critical development since 2011 has been the provision of free access by all higher education institutions in Kazakhstan to the world’s leading scholarly publications and the tools to mine databases of publications (OECD, Citation2017). There is also a drive to increase the number of new PhD students; the target was 1000 for 2015 and 2000 for 2020. Other targeted indicators were to have one top-ranked university by 2015 and two by 2020 and increase research output in publications in top-ranked journals. The establishment of NU in 2010 was part of the plan to achieve these aims. It marked the beginnings of the modernisation of university education in Kazakhstan with research output representation in respected international journals, substantial internationalisation programs, international faculty and student body and other trends commonly linked to modern globalisation processes encouraged and observed.

Many locate these changes within the wider policy of higher education internationalisation. Internationalisation in Kazakhstan involves students and faculty studying abroad through scholarships (Kuzhabekova et al., Citation2022; Lee & Kuzhabekova, Citation2018; Sordi, Citation2018), growing number of international students studying in Kazakhstan, (Mukhamejanova, Citation2019), the hiring of international faculty from Western universities to work in Kazakhstan (Kuzhabekova & Lee, Citation2018), partnerships with well-established and top Western universities (Jumakulov et al., Citation2019), the increasing use of the English language in higher education (Oralova, Citation2012; Zenkova & Khamitova, Citation2017) among many initiatives that are meant to help Kazakhstan’s higher education to be globally competitive.

2.2. From world-class university to the flagship university: the good university model for Kazakhstan

Salmi (Citation2013) raised the fundamental question of whether a young university can achieve world-class status. When NU was established in 2010, the government envisioned it as an autonomous world-class university, and a decade later, some critics are describing the idea as a failure because of NU’s absence in popular world university rankings (Osipian, Citation2021). A world-class university (WCU) “performs highly influential research, embody a culture of excellence, has great facilities, and retain a brand name that transcends national borders” (Douglas, Citation2016b, p. 3). The World Bank sees a high concentration of talented faculty and a high level of autonomy as generic traits of a WCU. The brand status of world-class designation is conferred rather than self-claimed (Ramirez, Citation2017; Rhoads et al., Citation2014). Consequently, world university rankings are used to identify world-class universities as rankings define what quality means (Marginson, Citation2016a). Most of these top universities are structured along with American and European models and the idea of the university (Luo, Citation2013), culminating in Pusser and Marginson’s (Citation2013) argument that rankings are an imperial project embodying the interests of the globally powerful states. Therefore, they reflect prestige and power (Marginson, Citation2007).

Some of the consistently top-ranked universities that appear in the different ranking regimes, such as QS World University Rankings and Times Higher Education, are more than a century old. Oxford has been in existence for 925 years, Stanford, 130 years and Harvard is 385 years old (Phillpott, Citation2019). The age of a university is an important impact factor in rankings, but there is no agreement of what constitutes a WCU (Altbach, Citation2004) “beyond the fact of occupying a superior hierarchical position in relation to other institutions” (Amsler & Bolsmann, Citation2012, p. 283). Furthermore, to Amsler and Bolsmann (Citation2012, p. 294), this is where elite people are funded by elite people to teach elite people knowledge of elites. Again, higher rankings attract top talent: students, administrators, and academics (Marginson, Citation2016a). Shahjahan and Edwards (Citation2021) used the theory of Whiteness to illustrate how university structures continue to be modelled along with White western ideals and culture, and hence the vision to be world-class, to be like Oxford, Cambridge or Stanford and the like. Attempts to establish a WCU are white aspirations of the future and educational agenda in response to global trends. WCU, like Whiteness, “represents status, desirability, development and global power” (Shahjahan & Edwards, Citation2021, p. 179). This perspective unmasks the hegemonic tendencies within the idea of WCU (Blanco, Citation2017). These critical observations of a WCU, the vision of NU when it was established ten years ago, portrays a WCU, not as a good university but an imperial entity.

On the other hand, a good university “is democratic, engaged, truthful, creative, and sustainable (Connell, Citation2019, p. 171). This emphasises the university as a place of collective activity where research, teaching, and other services combine for the good of society, following social justice principles and prioritising disadvantaged social groups. Pusser (Citation2006) views the university as a public sphere or place where critiques are generated to pursue the public good. A good university can also be seen as one that responds to its society’s demands, for example, economic demands such as relevant skills for a country’s development. In other words, a good university takes aboard the concerns of the state, academia, and the market (Hazelkorn, Citation2016; Udam & Heidmets, Citation2013) to provide good university education or quality university education (Harvey & Newton, Citation2007).

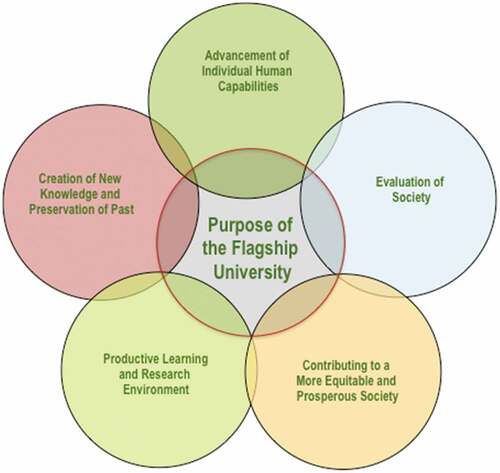

Altbach (Citation2004), Ramirez (Citation2017) are among some of the prominent scholars who argue that the WCU concept goes against the idea of a good university. Douglas (Citation2016b) argues for nation-states to concentrate on establishing national flagship universities. In a flagship university, “teaching and research would purposefully advance socioeconomic mobility and economic development. As part of an emerging national investment in education, public universities also had a role in nurturing and guiding the development of other educational institutions” (Douglas, Citation2016b, p. 31). It is a comprehensive research-intensive university located in one of its country’s largest urban areas (ARENA Centre for European Studies, Citation2018). Such a university has broad access, a wide selection of academic programs, engagement with local economies and leadership in developing public education. When one observes NU’s goals when it was established and current operations, it perfectly aligns with the flagship university model and not the widely publicised WCU. However, being a flagship university is not incompatible with WCU as both models focus on research productivity. However, the former “aims much higher to help articulate a larger purpose. And national and regional relevance and international engagement are mutually compatible goals-indeed the markers of the best universities” (Douglas, Citation2016a, p. 40). Flagship universities have a set of goals, shared good practices, logic, and the resources to pursue them. Besides engaging in high-quality research and scholarship, they are expected to deliver knowledge products to enhance national and regional development (Bunting et al., Citation2013). Figure below illustrates the purpose of a flagship university.

2.3. Current study

Contemporary research shows a consistent desire by national authorities throughout the world to establish WCUs through increased investment (Salmi, Citation2009, p. 2013). There is also a substantial body of scholarship questioning the concept of WCU and advocating for universities that are responsive and relevant to national and regional developments (Douglas, Citation2014, Citation2016a), not rankings. Salmi (Citation2013) identified Kazakhstan and Saudi Arabia as examples of emerging economies that declared the ambition to establish WCU, and such status is pronounced through global university rankings. Finland (Aarrevaara et al., Citation2009) and China (Zhang et al., Citation2013) are the other countries that have stated they aim to create WCUs.

With many of the world’s leading ranking higher education professionals questioning the idea of WCU (Altbach, Citation2004; Amsler & Bolsmann, Citation2012; Connell, Citation2019; Pusser & Marginson, Citation2013), this study is attempting to add to the growing body of research and literature, that investigates the establishment of WCU, and arguing that young universities should concentrate on being relevant to and serving their nations, and not being seen as world-class. As a result, the term flagship university is employed to describe NU, but being cognizant that at its establishment, the official aim was to create a WCU.

Previous research that promotes the flagship university idea has identified the presence of a high calibre of students, the best faculty, high research output, good funding, and devotion to institutional self-improvement. To Douglas, the challenge for universities that are leaders in their national systems is “to more overtly shape and pronounce their missions and, ultimately, to meaningfully increase their role in the societies that gave them life and purpose” (2016a, p. 5). Most of the research and publication on this critical topic utilise official statistics, like Bunting et al. (Citation2013) and Altbach and Salmi (Citation2011). Karran and Mallinson (Citation2018) collected empirical data from 1500 academics in the UK, and other works are commentaries and/or critiques of published world university rankings. To understand whether NU is a flagship university that is executing its mandate to the satisfaction of the people of Kazakhstan, this study sought the participation of local Kazakhstani professional administrative staff. Despite the rise of the roles of professional administrative staff in WCU, research university or flagship university, this university population is rarely utilised as research respondents. The following research questions guided the research study:

Research Question 1: Can the binary response variable, NU is a top university, be predicted by four predictor variables, highest education completed, age, international experience, and university position/rank. Which predictor variables are associated with the likelihood of considering NU as the flagship university in Kazakhstan. In other words, can NU’s flagship university status be significantly predicted by the four preceding variables?

Research Question 2: Do the four predictor variables of gender, international student experience, education and the number of years spent working at NU significantly predict the nominal response variable, NU is a flagship university. Specifically, do the three predictor variables significantly predict the cumulative odds and then the cumulative probabilities of being at or below a particular ranking viewpoint of NU as a flagship university, or the cumulative odds and then the cumulative probabilities of being above that level of viewing NU?

For the semi-structured interviews, the qualitative research questions were:

What are the views of the professional administrative staff towards the idea that NU is a flagship university in Kazakhstan?

What aspects of NU and their experiences and understandings contribute to perspectives of NU as a flagship university in Kazakhstan?

The mixed methods research question was: How can the understandings that emerge from the qualitative data (semi-structured interviews) be used to provide a deeper understanding of the administrative staff’s perceptions towards NU’s flagship university status?

3. Methodology

This study adopted a sequential QUAN-QUAL empirical mixed-methods approach (Creswell & Clark, Citation2007). In an explanatory sequential mixed method design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to explain and elaborate on the quantitative data (Cohen et al., Citation2018). The sampling frame provided by the NU human resources department had 706 individuals as Kazakhstan nationals with titles such as managers, directors, specialists, and advisors (Nazarbayev University Human Resources Department, Citation2020). The local professional administrative staff were utilised because at AU, 74% of academic staff were international, and 94% of the professional administrative staff were local Kazakh citizens. The locals were the participants because of their expert knowledge of the country, the education system and the experiential knowledge of NU. As the study assessed the university’s relevance to the country, Kazakh citizens were considered the most appropriate. The study adopted a random sampling strategy that ensured all administrative staff were relevant participants. The survey instrument was sent to all 706 individuals. 321 individuals completed and returned the survey. Out of the same sample of 321 participants, 16 were interviewed to seek elaboration, enhancement, illustration, and clarification of the results from the quantitative method (Buck et al., Citation2009; Greene et al., Citation1989). The 16 interviews are considered in this article. Adopting this approach enabled using qualitative results to explain and interpret quantitative findings.

3.1. Survey (quantitative) data

3.1.1. Sample

The overall sample consisted of 321 professional administrative staff employed at NU. The survey was electronically administered using Qualtrics. The instrument contained 26 items, including demographic variables and typically took 20 minutes to complete. Most items were measured on some form of Likert scale, with some Yes/No answers that allowed for follow-up questions. Overall, the sample had more females (68.22%) than males (31.78%), and over 80% of the staff were aged 40 and under. Regarding work experience, only 14.33% had international work experience. 68.54% had experience working at another university in Kazakhstan before they joined NU. Academically, 81.31% had a master’s degree qualification, and 5.3% had doctoral degrees. For professional designation within the university, 59.50% held titles of manager or senior manager.

3.1.2. Variables

The following are the variables used for data analysis in this paper:

NU is a top university- for this binary dependent variable, participants indicated their view on whether NU is a top leading university in Kazakhstan (1 = Yes, 2 = No). This dependent variable was created from a question where respondents indicated their level of agreement with the statement (1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = disagree, and 4 = strongly disagree).

NU is a modern research university- this ordinal dependent variable, participants indicated their level of agreement with the statement (1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = disagree, and 5 = strongly disagree).

Education- referring to highest education completed (1 = diploma/certificate, 2 = bachelor’s degree, 3 = graduate degree—masters/doctorate).

Age- the age in years of the participant (1 = 30 and under, 2 = 31 to 39, 3 = 40 to 49, and 4 = 50 and above).

International work experience- for this predictor variable, the participants indicated whether they had worked at any university outside Kazakhstan (1 = Yes, 2 = No).

University position/title- participants indicated their professional designations at NU (1 = administrative assistant, 2 = specialist, 3 = manager/senior manager, and 4 = director.

Gender- recorded variable of sex with 1 = male and 2 = female.

International student experience- participants indicated whether they had studied abroad during their student time (1 = Yes and 2 = No).

Years of experience working at NU (3 and less = 1, 4 to 6 = 2, 7 to 9 = 3, and 10 or more = 4).

4. Results

Using STATA statistical software, the multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted to estimate the probability of considering NU as a top (flagship) university in Kazakhstan from four predictor variables (Research Question 1). The dependent variable was NU is a top university or not, and the independent variables were the highest level of education, age, international university work experience, and university job title. The highest level of education was a categorical variable with three levels, so dummy coding was used for the following models. A two-predictor model with education and age as the predictor variables was fitted first. The full model with all the four predictors was fitted next. The log-likelihood ratio chi-square test statistic for the two-predictor model LRX2 (3) = 9.77, p < .001, indicated that the overall model with five predictors (including dummy variables for education) was significant. The log-likelihood ratio chi-square test for the full model LRX2 (5) = 13.83, p < .001, indicated that the overall model with all the predictors was significant.

The education predictor was a categorical variable with three levels. In the model, three dummy variables were automatically created with level 1 (certificate/diploma holders) as the reference level. For the dummy variable _Ieducation_2, odds ratio = 1.94. Since the reference level is level 1 (certificate/diploma holders), the odds ratio compares level 2 with level 1. It can, therefore, be interpreted that the odds of considering NU as the flagship university in Kazakhstan for bachelor’s degree holders is 1.94 times as large as the odds for the certificate/diploma holders when holding other predictors constant.

For the dummy variable _Ieducation_3, odds ratio = 2.97. Since it is the ratio of the odds for level 3 to the odds for level 1, it indicates that the odds of considering NU to be a top university for graduate (master’s and doctorate degrees) degree holders are 2.97 times the odds for the certificate/diploma holders when holding other predictors constant. In other words, the higher the level of one’s education, the more one considered NU as a flagship university. The professional administrative staff who are graduate degree holders recognise NU’s flagship university status more than certificate or diploma holders. Probably, the more time spent studying in universities the more one develops an understanding of university business and how to evaluate different institutions.

The predictor age is a continuous variable. Odds ratio = 1.741, which is more than 1. When an odds ratio is more than 1, it means an increase in the odds of success for each one-unit increase in the predictor when holding other variables constant. For each unit increase in age, the odds of considering NU as a top university increases by 1.741. So, the older the respondent the more they viewed NU as a top flagship university. This could be attributed to the participants’ knowledge of many other universities in Kazakhstan whose infrastructure and academic cultures are still considered conservative and not modern as is found at the very Westernised NU.

The other predictor, foreign/international work experience, is a dichotomous variable. Odds ratio = 4.022, p = .116, which is not statistically significant. When the odds ratio takes a value greater than 1, it means that there is a significant effect of the predictor variable on the odds of success when holding other variables constant. Therefore, having international work experience does significantly influence whether that professional administrative member views NU as a top university.

The title or position at NU was the other continuous variable. Odds ratio .793, which is less than 1. The Wald z = −0.94. The associated p-value P > |z| = .348, so we fail to reject the null hypothesis and conclude that there is no significant effect of one’s position or job title on the outcome variable. In other words, whether a person is an administrative assistant, a manager, or a director does not significantly predict whether that person considers NU as a top university

For research question 2, the multinominal logistic regression analysis was conducted to predict the ordinal outcome variable, NU is a modern and advanced research university, from a set of predictor variables, such as years of experience, study abroad experience, highest education qualifications and age. Although the multinominal logistic regression model is normally used to estimate nominal response variables, it is an alternative to estimate ordinal response variables when the proportional odds assumption is violated in the proportional odds models (Liu, Citation2016). The log-likelihood ratio test for the fitted model (16) = 66.84, p

.01, which indicated that the four-predictor model provided a better fit than the null model with no independent variables in predicting the logit of being in any other category of considering NU as an advanced research university with being in the base category (it is not a research university). Table displays the odds ratios for all the four predictor variables across four comparisons.

Table 1. Odds ratios for all predictor variables across the four comparisons (Y = J vs Y = 1)

For years of experience, the odds ratio of being in category 2 versus category 1, category 3 versus category 1, category 4 versus category 1 and category 5 versus category 1 were 0.47, 1.079, 0.730 and 0.096, respectively. Among them, only odds ratio of being in category 3 versus the base category indicated that the odds increased by 1.079. It is very close to 1. For the other three comparisons the odds decreased by .47, .73, and .10. All the odds are not statistically significant.

For study abroad experience the odds ratios for the four binary comparisons (i.e., categories 2 vs. 1, 3 vs. 1, 4 vs. 1, and 5 vs. 1) were .740, 1.297, .350, and .10 respectively. All these had a p .01, which indicated that there was no relationship between experience studying abroad and the odds of being in category 2, 3, 4, or 5 versus the base category 1. Studying abroad did not influence one’s view of NU as a flagship university.

For the education predictor, the odds ratio for the four binary comparisons (i.e., categories 2 vs. 1, 3 vs. 1, 4 vs. 1, and 5 vs. 1) were 1.103, .649, .441, and .488 respectively. OR(3,1) = −.433, z = −.932, p = .05 and OR(4,1) = −.818, z = .-353, p

.05, and in both these two cases, they were statistically significant. However, all the odds are close to zero.

With regard to age, the odds ratios for four binary comparisons (i.e., categories 2 vs. 1, 3 vs. 1, 4 vs. 1, and 5 vs. 1) were 1.672, 1.243, 2.230, and 1.807 respectively. OR(2,1) = .514, z = 1.335, p .05. OR(4,1) = .802, z = 1.004, p

.05. These two were statistically significant. This means that the odds of being in categories 2 and 4 versus the base category increased by 1.672 and 2.230 respectively, for one-unit increase in the predictor age when holding all other predictors constant. OR(3,1) = .218, z = .466, p

.05 indicated that there was no relationship between age and the odds of being in category 3 versus the base category 1. Similarly, OR(5,1) was not statistically significant.

4.1. Method: semi-structured interviews

From the 321 survey respondents, 25 professional administrative staff agreed and were sampled to be interviewed. Although the initial plan was to interview 25 administrative staff; at interview number 16, there was a realisation that the collection of new qualitative data was no longer changing the coding manual as the recent interviews produced already discovered data. Marshall et al. (Citation2013) referred to this as the point of saturation, which is the stage at which the performance of your research declines, i.e., each new interview makes a more negligible contribution than the previous one. The interviews drew narratives from the respondents on their views towards NU as a top university, a relevant institution, and an exemplary university in Kazakhstan. The interviews were done over zoom due to COVID-19 imposed restrictions. Data analysis for the qualitative data from the interviews started early by alternating between data collection and data analysis, which involved creating meanings from raw data. The cyclical process (Yeh & Inman, Citation2007) continued throughout the process. It was common to ask specific probing questions based on what was captured from the previous interview. Transcription was done manually. Data were segmented into meaningful analytical units, for example, sentences and paragraphs. These units were then coded under themes. As interview questions were informed by and related to the survey questionnaire, the main variables comprised the main themes or categories of the coded data.

To interpret the 16 semi-structured interviews, summative content analysis was used, involving counting and comparison of the (mostly) predetermined characteristics (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). The analysis probed and looked for clarifications of the ideas and perspectives that emanated from the quantitative survey questionnaire discussed above. Thirty interviews were carried out in total, but the analyses in this paper only utilised 16. This is because, by then, there was a realisation that the collection of new qualitative data was no longer changing the coding manual as the recent interviews produced already discovered data concerning this paper’s research aims. Marshall et al. (Citation2013) referred to this as the point of saturation. The data analysis consisted of the following steps:

Transcription. Initially, all zoom recorded interviews were transcribed.

Classification and coding. Following the input-process-output model (Van Damme, Citation2004; Westerheijden, Citation2007), some of the main features of a modern research university (flagship university) as outlined in contemporary literature and as also captured in the questionnaire were classified into six categories and divided into characteristics of modernity, top local university, local relevance, international competitiveness/comparisons, desirability to the locals and challenges or room for improvement.

Comparison and evaluation. The answers of all the 16 interviews, recorded as NU1 to NU16, were coded separately. Then the interviews were compared with each other and generalised where possible, as captured in the results section below.

4.2. Findings from interview data

The in-depth semi-structured interviews provided narratives from the professional administrative staff of their views towards NU as an exemplary or flagship university for Kazakhstan. The participants’ identities were anonymized and coded as NU1 to NU16. All other identifiers were also left out to respect research sensibilities of anonymity and confidentiality.

4.3. Exemplary university for Kazakhstan

To address the issue of NU as an example in Kazakhstan, other interviewees were impressed by the administrative structure and culture at the university they consider modern and democratic, which spurs them to work to achieve the university’s strategic goals. “NU is more professionally run than most other universities in Kazakhstan” (NU6, NU10, NU13). For NU15, “In terms of university administration in post-Soviet countries, none is like AU. We are autonomous and professional without unnecessary outside interference.” “It is the only autonomous university in this country,” added NU2. To address the question of what makes NU different and a good example, a question was asked for participants to explain why. NU3 provided more details:

NU is different. The academic culture here is different. Communication is not always top-down. We are allowed to write messages to the University President. In other universities in Kazakhstan, you get disciplined or fired if you do so. As an employee, I feel important to the university. My work is valued, and I am considered valuable. In other places I have worked, you are just a part of the chain that is not recognised. It is client or student oriented.

NU15 pointed out, “Our graduate students are in top league universities, e.g., Harvard, Stanford, Oxford, and Cambridge. This is a good assessment of NU and the teaching and learning taking place here.” Like most other respondents, AU8 observed what he considered modern practices.

In my role, I work on the retention of students and assisting undecided students to choose AU and our programs. Academic advising is not a practice in Kazakhstan. We are the pioneers here at AU. This is done in the West and not in Kazakhstan. Also, because of its merit-based recruitment, we recruit the cream. AU is not operating as a business. The state fully covers student funding.

Another question directly asked respondents why they would recommend NU to their family members and not any other university in Kazakhstan. NU9 echoed further approval of NU’s position:

This is a modern university and an example of other universities in this country. I have visited many universities, and comparatively, NU is a top institution that is recognised internationally. In 2017, NU was a founding member of the Asian University Association, something like Asia’s Ivy league. Other top universities in this association are the University of Tokyo, Tyna Hong Kong University, and the National University of Singapore.

Other related responses mentioned the presence of international faculty from Western universities and the fact that it provides English education (NU16, NU8). However, NU5’s narratives described a powerful interpretation of inequality of access hidden behind the general rosy portrayal of NU. She pointed out that “foundational courses are mainly for the middle class and rich. IELTS, SAT and TOFEL tests require family support to prepare for them as a secondary school does not have the required materials.” Respondents expressed many positives about AU, although they also pointed out that students from rural backgrounds and low-income families were likely to find it challenging to enter NU because of the use of the English language. Other comments supporting the flagship status of NU were from NU2, who said, “I can tell you as I compare with other universities in this country, AU is at the top. So many things, such as student services, infrastructure and generally all resources, are very modern.” Similarly, NU13 mentioned, “It is the top university in this country.” “There is unparalleled access to international partners and resources. Other universities are not funded as is done here,” NU6 observed. Other related responses were “It should be a model for other local universities. There is a modernity of practice here” (NU14) and “conditions of service are excellent for us here; there is no need to go abroad” (AU7)

4.4. Flagship university status

There was an overwhelming approval to the view that NU is a top university in Kazakhstan. Response ranged from admiring modern infrastructure and democratic administrative structure. NU4 was excited about the institution, and he said:

This university is a modern institution, ahead of time in the Kazakhstan context. The support provided to students and the infrastructure is unprecedented. The governance system is also modern. I find AU outside and on top of this country’s education system. It is unfair to compare it with other universities in Kazakhstan.

One must place NU within the national context to appreciate such a response. NU is the only autonomous university in the country and arguably the best funded. Many other interviewees echoed related comments. To NU10, “By this country’s standards, NU is modern. It has a great support system for students.” “NU is new and unique in Kazakhstan. It is a top university in Central Asia, the post-Soviet area” (NU1). The unique nature of NU’s infrastructure was a common observation from the participants. Some respondents describe NU as a top university. NU11 said, “It is very modern in terms of how it is being equipped, e.g., laboratories, technologies and other student and faculty support.” “Look at student accommodation. In other universities, there is overcrowding, but here, it is hotel-like accommodation. This is the best it can be for a student in this country” (NU7). As demonstrated by these comments from the participants, the unusual nature of the infrastructure shows how this makes NU a top and exemplary university. NU10 comparatively observed:

But NU does not compare to the University of Leicester, where I studied. Yes, the buildings at Leicester were old compared to the modern structures here, but I liked everything else there as a student.

4.5. International rankings

At its inception, NU was earmarked to be a world-class university and aspires to be a top-ranked institution in the country and the region (NU, Citation2023; OECD, Citation2017). This was put to the participants, and NU4 said:

Look at other universities in this country, e.g., L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian NationalUniversity. According to international rankings such as QS and THE, this is a top university but visit and see from the inside; it is well behind NU.

While modern technology and infrastructure are vital for modern university operations, participants were also impressed by the learning and professional practices they observed at NU. According to NU4:

Kazakhstan’s education system is accused of being corrupt at times. Here, the use of international staff, even among the administrative staff, has helped professionalise university service, unlike in many places in this country. These professionals are not linked or related to local groups or clans, which discourages favouritism.

Similarly, from NU12’s observations, “There is a high academic culture at AU. International faculty bring internationally recognised practices. Our Soviet academic practices were not good or professional in some respects.” The presence of international staff is widely observed as promoting the status of NU as the top university. Respondents such as NU10 said, “There are high-profile professors at this university.” “Our faculty in Kazakhstan used to be subjective and unfair, but here 80% are international, and they promote internationally accepted university practices” (NU10).

5. Discussion and conclusion

A flagship institution is, generally, simply a national university with sanctions and funding from national governments, one with the best students, the best teachers, high research output, and some influence on regional politics and economic activity. (Douglas, Citation2016b, p. 36).

Taken together, the quantitative and qualitative data support the above conceptualisation of a flagship university, and in this case, regarding NU. The purpose of this study was to examine local professional administrative staff’s views towards NU. As Kazakhstan citizens, the study assumed that they were the most suitable to assess this modern institution in the contemporary international higher education debate on international university rankings (Amsler & Bolsmann, Citation2012; Hazelkorn, Citation2015; Marginson, Citation2007, Marginson, Citation2016a), world-class universities (Altbach & Salmi, Citation2011; Blanco, Citation2017), research universities or simply, the good university (Connell, Citation2019; Marginson, 2016b). Using Douglas’s above definition of a flagship university, this study captured the views of locals to add to the growing body of research about relevant universities as opposed to world-class universities. The participants had excellent knowledge of Kazakhstan’s higher education system, and some have international experience as students and workers.

The positive views from the locals should also be contextualised within the seismic socio-economic processes that Kazakhstan has been undergoing since the fall of the Soviet Union. The changes are generally referred to as the transition to the market system or the opening of the country to internationally accepted norms and practices (Aitzhanova et al., Citation2014; OECD, Citation2017). Key in these policy changes has been the introduction of a trilingual policy with the English language joining Kazakh and Russian languages (Karabassova, Citation2020; Tokayev, Citation2019). NU is an English university and consequently a key signifier of modern Kazakhstan and the path to the future. The future is Western and English. One therefore, using the Whiteness analytics and critiques as was done in Shahjahan and Edwards (Citation2021) views NU in the eyes of the locals as a national aspiration and worthwhile investment.

There was a clear pattern of a positive view towards NU from all the different participants’ groupings. The statistical analysis suggests that one’s level of education, university working experience or job title were not significant differentiating factors on how one viewed NU. The evidence from the study contests the world-class university argument as the participants showed that they are concerned with a good university education that is responsive to Kazakhstan’s past and development needs. Without mentioning concepts such as world-class or flagship university, the interview data confirmed statistical data by consistently referring to NU as a top university, a good university, an exemplary university, and a modern university. All these descriptors confirm the flagship university status of NU in the eyes of the locals. Critical scholars on the topic issue of university rankings have argued that they are not against international standards of excellence focused on research productivity but advocate for a university grounded in national and regional service (Douglas, Citation2016b; Salmi, Citation2009). Furthermore, the qualitative interviews provide more evidence of how the people of Kazakhstan have given NU the flagship university status. Age, gender, work experience or international exposure, among other variables, did not differentiate the narrative towards NU. One would have expected the views of top administrators to differ from those of young and lowly ranked staff members. The narratives were positive towards NU, with many referring to it as a top university and a great workplace. This should be understood in the context of most modern international universities that represents the adoption of worldwide best practices, the creative domestication of foreign university models (Altbach, Citation2004), as was done in Kazakhstan. The interview data further corroborate quantitative data by revealing the changing face of Kazakhstan’s university education with NU as the leading catalyst of the modern transformation. The democratic and merit-based student recruitment and enrollment system was consistently referred to in the narratives and pointed out as a critical element of why NU is modern and breath of fresh air in university education. Other narratives mentioned the promotion of the bottom-up approach in the institution’s administrative style, further illustrating how NU represents a tremendous change in higher education practice in the post-Soviet era. It can be argued that contextual and institutional factors, such as level of education, work experience, study abroad experience or job title/position at NU, do not significantly influence one’s perception towards NU as a flagship university in Kazakhstan. The administrative system at NU, its international staff texture, modern facilities, and democratic practices, among other institutional factors, seem to have a neutralising effect on taming any critical views among the staff. Altogether, the analysis shows an overwhelmingly positive view of NU as the ideal university for Kazakhstan, hence the use of the term flagship university and not a world-class university. It is a university that is attempting to balance academic excellence and social relevance. As Douglas (Citation2016b) argued, the flagship university model is not a wholesale repudiation of rankings or the desire for a global presence but aims higher to articulate national and regional relevance.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Nazarbayev University Institutional Research Ethics Committee (NU-IREC) and the approval number is: 250/24022020 “

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Aarrevaara, T., Dobson, I., & Elander, C. (2009). Brave new world: Higher education reform in Finland. Higher Education Management and Policy, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1787/hemp-21-5ksj0twnffvl

- Ahn, E. S., Dixon, J., & Chekmareva, L. (2018). Looking at Kazakhstan’s higher education landscape: From transition to transformation between 1920 and 2015. In J. Huisman, A. Smolentseva, & I. Frumin (Eds.), 25 years of transformations of higher education systems in post-Soviet countries (pp. 199–227). Palgrave.

- Aitzhanova, A., Katsu, S., Linn, J. F., & Yezhov, V. (2014). Kazakhstan 2050: Toward a modern society for all. Oxford University Press.

- Altbach, P. G. (2004). Globalisation and the university: Myths and realities in an unequal world. Tertiary Education and Management, 10(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:TEAM.0000012239.55136.4b

- Altbach, P. G., & Salmi, J. (2011). The road to academic excellence: The making of world-class research universities. The World Bank.

- Amsler, S. S., & Bolsmann, C. (2012). University rankings as social exclusion. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 33(2), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2011.649835

- ARENA Centre for European Studies. (2018) . European flagship universities: Balancing academic excellence and social relevance. University of Oslo.

- Azimbayeva, G., & Harford, J. (2017). Comparing post-Soviet changes in higher education governance in Kazakhstan, Russia, and Uzbekistan. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1399968

- Bayetova, N., & Robertson, D. (2019). Privatization and Kazakhstan’s emerging higher system. The World View. Center for International Higher Education.

- Blanco, G. (2017). Jean Baudrillard’s radical thinking and its potential contribution to the sociology of higher education illustrated by debates about world-class universities. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 26(4), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2017.1322913

- Buck, G., Cook, K., Quigley, C., Eastwood, J., & Lucas, Y. (2009). Profiles of urban, low SES, African American girls’ attitudes toward science: A sequential explanatory mixed-methods study. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 20(10), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689809341797

- Bunting, I., Cloete, N., & van Schalkwyk, F. (2013). An empirical overview of eight flagship universities in Africa: 2001-2011. Centre for Higher Education Transformation.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research Methods in Education. Routledge.

- Connell, R. (2019). The good university: What universities actually do and why it’s time for radical change?. Monash University Publishing.

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage.

- Douglas, J. A. (2014). The flagship university: A response to the world-class university paradigm. University World News, 25 April, https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20140423113704590, Retrieved on May 10, 2021.

- Douglas, J. A. (2016a). The evolution of flagship universities: From the traditional to the new. Centre for Studies in Higher Education.

- Douglas, J. A. (2016b). The new flagship university: Changing the paradigm from global ranking to national relevancy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Engvall, J., & Cornell, S. E. (2015). Asserting statehood: Kazakhstan’s role in international organisations. Central Asia-Caucasus Institute.

- Froumin, I., Kouzminov, Y., & Semyonov, D. (2014). Institutional diversity in Russian higher education: Revolutions and evolution. European Journal of Higher Education, 4(3), 209–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2014.916532

- Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737011003255

- Harvey, L., & Newton, J. (2007). Transforming quality evaluation: Moving on. In D. F. Westerheijden, B. Stensaker, & M. J. Rosa (Eds.), Quality assurance in higher education trends in regulation, translation, and transformation (pp. 225–246). Springer.

- Hazelkorn, E. (2015). Global rankings and the geopolitics of higher education: Understanding the influence and impact of rankings on higher education, policy and society. Routledge.

- Hazelkorn, E. (2016). Global rankings and the geopolitics of higher education: Understanding the influence and impact of rankings on higher education, policy and society. Routledge.

- Hazelkorn, E., & Gibson, A. (2019). Public goods and public policy: What is public good, and who and what decides? Higher Education, 78(2), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0341-3

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Institutional Evaluation Programme. (2017). Nazarbayev University. European Universities Association. https://www.iep-qaa.org/downloads/publications/iep_report%20final_nu.pdf

- Jumakulov, Z., Ashirbekov, A., Sparks, J., & Sagintayeva, A. (2019). Internationalizing research in Kazakhstan higher education: A case study of Kazakhstan’s State program of industrial innovative development 2015 to 2019. Journal of Studies in International Education, 23(2), 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318786445

- Karabassova, L. (2020). Understanding trilingual education reform in Kazakhstan: Why is it stalled? In D. Egéa (Ed.), Education in Central Asia: Education, equity, economy (pp. 37–52). Springer.

- Karran, T., & Mallinson, L. (2018). Academic freedom and world-class universities: A virtuous circle? Higher Education Policy, 32(3), 397–417. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-018-0087-7

- Kazinform. (2010). Kazakhstan joined the bologna process at sitting of bologna ministerial forum. Kazinform Report, March 12, http://www.inform.kz/eng/article/2247114, Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- Koch, N. (2015). Domesticating elite education: Raising patriots and educating Kazakhstan’s future. In M. Ayoob & M. Ismayilo (Eds.), Identity and Politics in Central Asia and the Caucasus (pp. 82–100). Routledge.

- Kuzhabekova, A., Ispambetova, B., Baigazina, A., & Sparks, J. (2022). A critical perspective on short-term international mobility of faculty: An experience from Kazakhstan. Journal of Studies in International Education, 26(4), 454–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153211016270

- Kuzhabekova, A., & Lee, J. (2018). Relocation decision of international faculty in Kazakhstan. Journal of Studies in International Education, 22(5), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318773147

- Lee, J. T., & Kuzhabekova, A. (2018). Reverse flow in academic mobility from core to periphery: Motivations of international faculty working in Kazakhstan. Higher Education, 76(2), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0213-2

- Liu, X. (2016). Applied ordinal logistic regression using Stata. Sage.

- Luo, Y. (2013). Building world-class universities in China. In J. Shin & B. Kehm (Eds.), Institutionalisation of world-class university in global competition (pp. 165–183). Springer.

- Marginson, S. (2007). Global position and position-taking: The case of Australia. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(1), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315306287530

- Marginson, S. (2016a). Higher education and the common good. Manchester University Press.

- Marginson, S. (2018). Public/Private in higher education: A synthesis of economic and political approaches. Studies in Higher Education, 43(2), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1168797

- Marshall, B., Cardon, P., Poddar, A., & Fontenot, R. (2013). Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in is research. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 54(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2013.11645667

- Ministry for Education and Science. (2010) . State program of education development for 2011-2020, Decree of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan No. 1118. Government of Kazakhstan.

- Ministry for Education and Science. (2018). National report on the state and development of the education system of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Information Analytic Centre.

- Mukhamejanova, D. (2019). International students in Kazakhstan: A narrative inquiry of human agency in the process of adaptation. Comparative Education and Development, 21(3), 146–163. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCED-07-2018-0024

- Nazarbayev, N. (2006). Address of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev, to the People of Kazakhstan. https://www.akorda.kz/en/addresses/addresses_of_president/address-of-the-president-of-the-republic-of-kazakhstan-nursultan-nazarbayev-to-the-people-of-kazakhstan-march-1-2006

- Nazarbayev University. (2019). Brochure. https://nu.edu.kz/wpcontent/uploads/2020/03/Brochure-2019_NU_ENG.pdf, Retrieved on May 15, 2021.

- Nazarbayev University. (2023). General information: About us. Available at: https://nu.edu.kz/about Retrieved on January 30, 2023)

- Nazarbayev University Human Resources Department. (2020) . Academic and administrative staff list. Nazarbayev University.

- OECD. (2017). Higher education in Kazakhstan 2017: Reviews of national policies for education. OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268531-en. Retrieved on April 20, 2021.

- Oralova, G. (2012). Internationalisation of higher education in Kazakhstan: Issues of instruction in foreign languages. Journal of Teaching and Education, 1(2), 127–133.

- Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2007) . Higher education in Kazakhstan. OECD Publishing.

- Osipian, A. A. (2021). Why world-class status is still mostly out of reach? University World News, April 25, https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20210420153825830, Retrieved on May 12, 2021.

- Phillpott, S. (2019). The 20 oldest universities in the world. Career Addict. https://www.careeraddict.com/oldest-universities-world, Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- Pianciola, N. (2001). The collectivization famine in Kazakhstan, 1931-1933. Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 25(3–4), 237–251.

- Piven, G., & Pak, I. (2006). Higher education in Kazakhstan and the Bologna process. Russian Education and Society, 48(10), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.2753/RES1060-9393481007

- Poletaev, D., & Rakisheva, B. (2011). Educational migration from Kazakhstan to Russia as an aspect of strategic cooperation within the customs union. In Vinokurov, E. (Ed.), Eurasian integration-historical and social aspects (pp. 198–219). Eurasian Development Bank.

- Pomfret, R. (2014). Kazakhstan’s progress since independence. In A. Aitzhanova, S. Katsu, J. F. Linn, & V. Yezhov (Eds.), Kazakhstan 2050: Toward a modern society for all (pp. 15–35). Oxford University Press.

- Pusser, B. (2006). Reconsidering higher education and the public good: The role of public sphere. In W. Tierney (Ed.), Governance and the public good (pp. 11–27). State University of New York Press.

- Pusser, B., & Marginson, S. (2013). University rankings in critical perspective. The Journal of Higher Education, 84(4), 544–568. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2013.0022

- Ramirez, G. B. (2017). Jean Baudrillard’s radical thinking, and its potential contribution to the sociology of higher education illustrated by debates about world-class universities. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 26(4), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2017.1322913/

- Rhoads, R. A., Wang, X., Shi, X., & Chang, Y. (2014). China’s rising research universities: A new era of global ambition. Johns Hopkins University.

- Sagintayeva, A., & Jumakulov, Z. (2015). Kazakhstan’s Bolashak scholarship program. International Higher Education, 79(79), 21–23. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2015.79.5846

- Sagintayeva, A., & Kurakbayev, K. (2015). Understanding the transition of public universities to institutional autonomy in Kazakhstan. European Journal of Higher Education, 5(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2014.967794

- Salmi, J. (2009). The challenge of establishing world class universities. Directions in development series. The World Bank.

- Salmi, J. (2013). The vintage handicap: Can a young university achieve world-class status? International Higher Education, 70(70), 2–6. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2013.70.8701

- Saparbekova, A., Kocourková, J., & Kučera, T. (2014). Sweeping ethno-demographic changes in Kazakhstan during the 20th century: A dramatic story of mass migration waves from the turn of the 19th century to the end of the Soviet era. AUC Geographica, 49(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.14712/23361980.2014.7

- Shahjahan, R. I., & Edwards, K. T. (2021). Whiteness as futurity and globalisation of higher education. Higher Education, 87(4), 747–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00702-x

- Sharipov, M. (2021). Globalisation and Kazakhstan higher education: Past, present, and future. Nazarbayev University.

- Sordi, A. D. (2018). Sponsoring student mobility for development and authoritarian stability: Kazakhstan’s Bolashak programme. Globalizations, 15(2), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2017.1403780

- Starr, S. F., & Engvall, J. (2017). Kazakhstan in Europe: Why Not?. Central Asia-Caucasus Institute.

- Tanatarova, Z. T. (2015). Repressions of 1937-1938 in Kazakhstan and their consequences. International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education, 2(1), 100–106.

- Tian, L., & Liu, N. C. (2019). Rethinking higher education in China as a common good. High Education, 77(4), 623–640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0295-5

- Tokayev, K. J. (2019). About trilingualism: It is a very complex and important question. ZONA KZ. https://zonakz.net/2019/03/27/tokaev-o-trexyazychii-eto-ochen-slozhnyj-i-vazhnyj-vopros/.

- Udam, M., & Heidmets, M. (2013). Conflicting views on quality: Interpretations of a good university by representatives of the state, the market and academia. Quality in Higher Education, 19(2), 210–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2013.774805

- Van Damme, D. (2004). Standards and indicators in institutional and programme accreditation in higher education: A conceptual framework and a proposal. In L. Vlasceanu & L. C.Barrows (Eds.), Indicators for institutional and programme accreditation in higher/tertiary education, 125–157. UNESCO.

- Westerheijden, D. F. (2007). States and Europe and quality of higher education. In D. F. Westerheijden, B. Stensaker, & M. J. Rosa (Eds.), Quality assurance in higher education: Trends in regulation, translation, and transformation (pp. 73–98). Springer.

- Yeh, J. Y., & Inman, A. G. (2007). Qualitative data analysis and interpretation in counseling psychology: Strategies for best practices. The Counselling Psychologist, 35(3), 369–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006292596

- Zenkova, T., & Khamitova, G. (2017). English medium-instruction as a way of internationalization of higher education in Kazakhstan: An opinion survey in the innovative university of Eurasia. E-TEALS: An E-Journal of Teacher Education and Applied Language Studies, 8(1), 126–158. https://doi.org/10.2478/eteals-2018-0006

- Zhang, H., Patton, D., & Kenney, M. (2013). Building global-class universities: Assessing the impact of the 985 project. Research Policy, 42(3), 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.10.003

- Zimovina, E. P. (2003). Dynamics of the number and composition of the population of Kazakhstan in the second half of the twentieth century. Bulletin Population and Society, 103-104. assessed April 6, 2021 http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2003/0103/analit03.php