?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Meaningful learning occurs when individuals connect their existing knowledge with their current understanding. Unfortunately, many teaching practices neglect the learners' subconscious knowledge, also known as their ”funds of knowledge.” The result is a disconnect between school and home knowledge, social injustice towards students whose parents lack formal education, and frustration among learners.In this paper, we argue that mathematical concepts found in cultural games can teach children in grades 4-6 mathematics in Ghana. By describing math-rich games from Ghanaian culture and showing where they fit into the curriculum, we aim to provide teachers with examples of incorporating cultural games into their instruction. Our project emphasizes the importance of using games to enhance teacher pedagogy by blending established teaching methods with innovative strategies incorporating artistic games.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Making mathematics relevant to learners involves presenting concepts in a way that makes sense in their culture (d’Ambrosio, Citation2016). Students perceive mathematical concepts as abstract and insignificant when they cannot connect them to what goes on in their everyday life (Bishop, Citation1997). Learners draw on and connect their everyday experiences to form a mental picture of what they have heard from their teacher to make sense of mathematical concepts. Therefore, daily activities play a vital role in the understanding of mathematics.

Mathematical concepts exist in the daily activities of all cultures (Bishop, Citation1997; D. Mereku & Mereku, Citation2013). In several African communities, activities like cultural games have mathematical concepts (Bhuda & Marumo, Citation2021; Chikodzi & Nyota, Citation2010; D. Mereku & Mereku, Citation2013). For example, D. Mereku and Mereku (Citation2013) demonstrated how children could learn (fairness and chance) probability, problem-solving strategies, pattern recognition, making and testing the hypothesis, reasoning and disproving, and common multiple with Ghanaian cultural games. However, there is still much more to demonstrate how cultural games can be deliberately used in mathematics instruction in Ghana.

Children love games. In play, they practice mathematical ideas; therefore, through cultural games, children learn mathematics. If teachers deliberately connect cultural games to teach mathematics, children will enjoy mathematics instruction and learn well. Also, the repetitive nature of games gives children the chance to engage in constant practice, which is fundamental to the sustained understanding of mathematical concepts. However, very few studies have addressed continuous practices of using cultural games to understand mathematics. Children need several mathematical examples and practice to make sense of mathematical concepts (Fouze & Amit, Citation2017). Cultural games provide these learning moments with fun.

Language, as a cultural phenomenon, weaves people together just as fibers make a fabric. It defines how we communicate, form, and build relationships, and think about patterns of life. In the classroom too, learners and teachers use language to verbalize their thinking. Children learning in their mother tongue are more likely to enroll and succeed in school (Ball, Citation2010). Additionally, mother tongue-based education primarily benefits disadvantaged groups, including children from rural communities” (Ball, Citation2010). The medium of instruction in primary schools in Ghana toggles between the English language and learners’ mother tongue since 1987. The reasons for adopting the mother tongue in Ghanaian schools have been nurturing cultural identity and facilitating the transfer of learning. The current working policy requires using the local language (L1) as a medium of instruction from kindergarten to stage 3 (Anyidoho, Citation2018). When the local language is used to study mathematics, students do better (Ball, Citation2010; Seudib et al., Citation2020). We argue that cultural games provide ample opportunity for children to use their language in learning.

Since independence, there have been several attempts to improve mathematical instruction in Ghana’s basic schools using culturally accessible examples (D. K. Mereku, Citation2010). While teachers have taught mathematics for several years, using their strategies, cultural games have been missing from the pedagogical practice. If teachers harness cultural games in conjunction with culturally relevant strategies to teach mathematics concepts, children’s understanding of math concepts will improve. Similar to the United States, where education has evolved from changing learner’s cultural practices to accepting and including each learner’s ways of knowing (Ladson-Billings, Citation1995; Paris, Citation2012) in Ghana, we argue that when teachers present mathematical concepts to students through cultural games, students’ mathematical proficiency will improve. The assumption is that cultural games are children’s primary ways of learning.

The purpose of this paper is to survey African cultural games with mathematical concepts to provide elementary school teachers with culturally suitable strategies for improving student learning and their teaching pedagogy. The central question is: what mathematical concepts covered in Ghana’s basic school curriculum can be taught using cultural games? Sub questions are:

What concepts do teachers teach in primary schools?

What games will address these mathematical concepts?

What are the implications for curriculum and instruction?

In what follows, we will present a review of the literature on mathematics instruction in Ghana, highlighting the key concepts teachers cover in basic education as well as the established ways of teaching mathematics. We will then present games that address the mathematical concepts in the mathematics curriculum and how these cultural games can be used for pedagogy, Our paper demonstrates the value of cultural games in enhancing students’ learning of Mathematical concepts and improving teacher pedagogy

2. Cultural games

In Ghana, teachers are expected to incorporate games into their teaching despite the fact that the syllabus (MOE,1997) does not provide a clear definition of games (Nabie, Nabie, Citation2011). Various authors have defined games differently. For instance, Bhuda and Marumo (Citation2021) define games among the Ndebele as context-specific human activities involving players who follow the rules with the aim of winning at the end of the activity. On the other hand, Garegae-Garekwe sees games as tools that help children in Botswana communicate with the world.

Cultural games, “refer to those contests or playful activities shared by the members of the community over several generations” (Nabie, Citation2008, p. 15). These games are not exclusive to specific ethnic or tribal groups but can be shared across similar cultures. For example, children from various ethnic groups in Ghana play the konko car game. In our study, we use cultural games and games interchangeably to describe any activity with rules passed down by generations in which learners participate to identify a winner.

3. Ghana basic school mathematics philosophy

The teaching philosophy accepted in Ghanaian basic schools is that schools should provide learners with an environment where they can “expand, change, enhance and modify how they view the world” (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment [NaCCA], Citation2019, p. vi). Therefore, constructivist-based teaching approaches are valued, where teachers use the knowledge children bring to Ghanaian schools (NaCCA, Citation2019). If the learning environment encourages the wealth of knowledge among children, then constructivist teaching approaches such as the guided discovery method, problem-solving strategy, and inquiry teaching methods will define classrooms. The current rationale for school curriculum, teaching, and learning philosophy is constructivists.

A teacher in Ghana needs to facilitate a constructivist learning process. While several authors have bemoaned the progress of mathematics education being distant from Ghanaian children’s learning styles, many advocates for constructivist learning situated in children’s cultural knowledge (D. K. Mereku, Citation2010; Fletcher, Citation2018; Okyere, Citation2022). If teachers create an environment that will involve learners physically and cognitively during the learning process, then learners’ prior knowledge and beliefs are acknowledged. Fletcher (Citation2018) has argued that teachers hold the key to learners’ success in Mathematics and science education in Ghana. Rightly so, learners need to reorganize and reconstruct their existing knowledge and beliefs for understanding. For example, the average Ghanaian child comes to school with a different measurement system than the western one taught in school. These measurement systems are grounded in everyday social and cultural practices. The National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NaCCA) in Ghana acknowledges that the rationale for basic school mathematics in Ghana is that mathematics is part of everyday life and necessary for national development (NaCCA, Citation2019).

Mathematics learning built on cultural life is a process d’Ambrosio (Citation2016) calls Ethnomathematics. Arguing that each culture has a unique way of understanding and creating new knowledge, d’Ambrosio argues for exploiting these unique ways for societal advancement. Similarly, our paper demonstrates the value of cultural games in enhancing students learning of Mathematical concepts and highlights the value of cultural games in improving teacher pedagogy by simultaneously using established ways of teaching maths with cultural games. For instance, average Ghanaian parents employ mathematical concepts like ratios and proportions, and estimations during cooking. Therefore, teachers’ task is to use constructivist teaching strategies such as Ethnomathematics to facilitate meaningful learning. In what follows, we address post-independence mathematics instruction in Ghana, what others, African scholars, have written about cultural games and mathematics, and the role cultural games can play in providing instruction that advances the national educational goals.

4. Post-independence mathematics instruction in Ghana

After independence, there was a post-colonial desire to change the content and curriculum materials our colonial masters, mainly the British, provided. D. K. Mereku (Citation2010, Citation2000) provides an overview of mathematics education in Ghana, acknowledging the role colonial masters and others played in defining the content of the curriculum. School Mathematics in Ghanaian schools was all about arithmetic, algebra, and geometry (D. K. Mereku, Citation2000). Elementary school mathematics was mainly arithmetic, and secondary school mathematics focused on arithmetic, algebra, and geometry. Behaviorist teaching strategies like training pupils to perform arithmetic quickly were paramount. Children had to respond quickly to questions teacher’s read out only once, so oral arithmetic drills were central to mathematics instruction (D. K. Mereku, Citation2000 cites Gyang, Citation1979, p. 23). Mereku identified three problems with the imported curricula, the irrelevance for the Ghanaian child, the emphasis on drills, and the complexity of the language.

Therefore, between 1960–1971, mathematics scholars and education officersFootnote1 worked on a new mathematics curriculum. Their efforts gave birth to the Mathematics curriculum projects like Africa Mathematics Project (AMP) for elementary schools and the Joint School Project (JSP) for secondary schools developed for the countries involved (Williams, Citation1976). The countries included were Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Uganda, Tanzania, and Zambia (Williams). The desire for change in what pupils learn in school had heightened. The content and teaching methods were adapted to Ghanaians’ daily business transactions and focused mostly on addition and subtraction. However, there needed to be continuity between earlier AMP curricula and the new Joint School Mathematics project, because elementary school graduates lacked the prerequisites for secondary school mathematics (Eshun, Citation2000; K. D. Mereku, Citation1998). Additionally, most teachers needed more content knowledge to teach the curriculum.

Mathematics teaching changed with the implementation of the 1987 curriculum. Discovery, differential learning strategies, and adapting teaching activities to encourage teaching skills with materials became paramount (Eshun, Citation2000; K. D. Mereku, Citation1998). While the curriculum called for discovery learning, the teachers had neither enough content knowledge nor pedagogical knowledge to implement the new curriculum (D. K. Mereku, Citation2000; Eshun, Citation2000; K. D. Mereku, Citation1998). Therefore, many students struggled to understand the senior secondary school mathematics syllabus content in the 1987 educational reform (K. D. Mereku, Citation1998). The reforms affected all school subjects, and the mathematics syllabus included several new topics like

“number bases, sets of numbers, vectors, clock arithmetic, points in a number plane, transformational geometry, probability and statistics; and some of the new terms are added, commutative, distributive, place value, ray, intersection, line segment, mode, rational numbers, integers, to mention only a few.” (D. K. Mereku, Citation2010, p. 79).

In an address at the 6th National Biennial Delegates Conference of the Mathematical Association of Ghana (MAG), President Eshun outlined the promises and challenges with the 1987 mathematics curriculum. While there were several promising aspects of the JSP, Eshun’s criticism argued for more continuity. The JSP was for senior high school students and did not consider the material covered in the AMP, the Junior secondary school curriculum (Eshun). Also, The two programs focused on group learning however, cultural games which emphasize group learning were not part of JSP or AMP. Therefore, Eshun made a case for Teaching for Understanding (TFU), a framework with four features. In the first stage, teachers need to identify an area or topic, for example, area, fraction, and labeled knowledge. Second, teachers need to define understanding goals, which include building and validating knowledge and awareness of the purposes and uses of knowledge. Thirdly, students demonstrate mastery performance, and understanding when they solve problems, explain processes, also using technology.

Therefore, the 2001 curriculum was developed with the Teaching for Understanding framework. The four-year senior high school syllabus was reduced to three years, with a revised 2007 curriculum in 2011. From 2011 to 2019, the students learned from seven main content areas: algebra, vectors, etc (Ministry of education, teaching syllabus for core Mathematics, 2010, p ii). Interestingly, none of these concepts were taught using cultural games, even though discussions had begun in the mathematics education community concerning using cultural games in mathematics instruction (D. Mereku & Mereku, Citation2013). For example, Mereku and Mereku articulated how pebble-picking games can strengthen students’ problem-solving strategies like try and error, pattern recognition, making and testing the hypothesis, reasoning, and disproving. They selected three of four singing games, and suggested that Sansaw Akroma singing game can be used to teach the least common multiple with the movement of the stones (Mereku and Mereku).

An analysis of the morabaraba game in Southern Africa, Bhuda and Marumo (Citation2021), revealed that the game has mathematical concepts like quadrilateral, ratio and proportion, symmetry, counting, and some operations on counting on natural numbers. It was also revealed that as learners play together, despite efforts to make the learners speak louder, they tend to be very quiet and concentrate on their next move, they were few verbal exchanges (Bhuda & Marumo, Citation2021). Similarly, Chikodzi and Nyota (Citation2010) studied how mathematical concepts in cultural games can improve mathematics performance in the rural areas of Zimbabwe. They shared many games that have mathematical concepts in Zimbabwe.

5. Cultural games for advancing national educational goals

Like mathematics, certain accepted rules need to be followed to arrive at an accepted and desirable end. Games sharpen players’ deductive thinking and build contest-specific vocabularies, logical reasoning, and discovery pattern. Therefore, in line with Ghana’s Education Strategic Plan (ESP), game is critical to children’s growth and development (ESP, 2018–2030 p. 21) National Curricular goals encourage psychomotor, affective and cognitive learning (NaCCA, Citation2019) and cultural games advance these learning domains.

Learning mathematics involves whole body active participation. Like mathematics, games too involve active participation. It involves participants’ emotions, cognition and psychomotor (Addo, Citation2013). The advantage of games over mathematics is that games are fun. Indigenous games have indigenous knowledge and experiences. Studies have shown using indigenous to teach mathematics improves proficiencies, performance, and a sense of relevance of mathematical concepts (Bhuda & Marumo, Citation2021; Chikodzi & Nyota, Citation2010; D. Mereku & Mereku, Citation2013). Some culturally specific African games have mathematical concepts. Games involve the use of the hand, the heart and the head. For instance, players go through some mental process (Bhuda, & Marumo), learn how to be team players and master certain skills during the game, such as, logical thinking. When games are used in teaching and learning, learners actively partake in the learning process.

Studies have addressed the importance of mother tongue in children’s learning (Anyidoho, Citation2018; Ball, Citation2010; Seudib et al., Citation2020). Until 1970, many students’ languages, cultural ways were viewed as deficient and undemanded(deficit approaches) and that education involves inculcating the demanded and seemingly superior cultural practices; the formulation of funds of knowledge (Moll and Gonzalez, Citation1994). Observing Native American children in US schools Moll and Gonzalez took the position that important cultural resources for teaching in schools (p .442). Locating identifying and documenting these resources was the focus of their work. Similarly we are in this paper, highlighting the need to document cultural resources, what Moll and Gonzales call “Funds of Knowledge” from community members. Their “mediated” approach, studying students’ house holds, to instruction, resonates with our quest to locate cultural games children played or have played in the past for mathematics instruction. They provided evidence that meaningful language learning incorporates ones cultural background, and we argue the same for mathematics learning in Ghana.

National educational goals require that education becomes relevant to the learner (NaCCA, Citation2019; ESP, 2018–2030). The teaching and learning philosophy of the current syllabus expect teachers to make the classroom lively for learners (Armah, Citation2021; NaCCA, Citation2019; ESP, 2018–2030). While there are several studies emerging on indigenous games and instruction (Bhuda & Marumo, Citation2021; Chikodzi & Nyota, Citation2010; D. Mereku & Mereku, Citation2013; Fouze & Amit, Citation2017; Nabie, Citation2015; Nkopodi & Mosimege, Citation2009), few have addressed its direct alignment with the curriculum Ghana. In what follows, we present our method of surveying African cultural games with mathematical concepts, and identifying culturally suitable strategies for improving mathematics teaching and learning.

6. Method

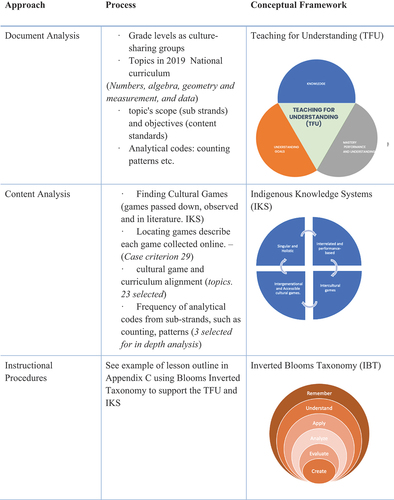

In this case study of African cultural games and mathematics instruction, we analysed Ghana’s national mathematics curriculum documents for basic 4–6 (Grade/Primary 4–6) and surveyed cultural games. Yin (Citation2018) distinguishes between the mode, method, and unit of inquiry in case study research. Therefore, in our study, the case study is the mode, the document and content analysis our method, and the cultural game is our unit of inquiry (See Appendix A for Cultural Games). The document analysis complemented the content analysis, providing the context for studying and utilising cultural games in mathematics instruction (Bowen, Citation2009). We examined curriculum documents to determine the mathematical concepts coverage requirements for teachers in instruction. Grade-level groupings are culture-sharing groups and therefore serve as a framework for organising and addressing the cultural games that could support learning mathematical processes (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018). Then, because we attempt to gain an in-depth understanding of each game selected, the games serve as cases (Yin, Citation2018).

First, we used the broad framework of grade levels as culture-sharing groups to examine curriculum documents (See Appendix B: Table ). In our document analysis, we reviewed the topics in the curriculum document and the topic’s scope and objectives at each grade level using a systematic procedure (Bowen, Citation2009). Because the 2019 curriculum was built on previous curriculum reforms starting in 2001, and the Teaching for Understanding framework, we considered it for “selecting, appraising and synthesizing” information (Bowen p.28). Therefore, we reviewed the curriculum to determine the knowledge, goals, mastery performance, and understanding. After reading through the curriculum to understand its’ structure within each topic or strand, we searched for analytic topics, substrands, and content standards, that would support the selection of games. Based on our initial analysis, we acknowledged that the curriculum topics (Numbers, algebra, geometry and measurement, and data) would guide our selection of games to match each issue.

Second, we collected data on cultural games to provide insight into improving primary school mathematics instruction. The inclusion of the games follows three criteria:

The game must be suitable for children to play.

Games must have at least one mathematical concept that aligns with the curriculum topics.

It must be a cultural game that originated in Ghana.

Our goal was to deeply understand each game we selected, including what it is, how it works, and how it intersects with mathematical concepts (Yin, Citation2018). While we drew from various sources, we also wanted to give the reader access to online audio-visual documentation of these games. Therefore, each game represented here, we played as young children, observed others play, games passed to us from our communities, and collected from the literature (D. Mereku & Mereku, Citation2013) on cultural games played in Ghana and is recorded online. We provide the links to these materials in the appendix and sometimes in the text (See Appendix A). Because we would like to examine the current mathematics curriculum and existing games, we source various data on cultural games. For the content analysis, using the mathematics curriculum as a guide, we a) wrote descriptions of each game collected online, b) determined if the cultural game aligned with the curriculum content standard for numbers, algebra, geometry and measurement, and data, c) assigned games with a high frequency of analytical codes from sub-strands, such as counting, patterns, and so on to the content standard of the grade case (NaCCA, Citation2019). We first identified 29 games with mathematical concepts, then we selected and described 23 games aligned with the case criterion. From the twenty three, we selected three for an in-depth description within the paper. Drawing on Nzewi’s work, African Systems of Thought and cultural forms like musical arts, Indigenous knowledge Systems guided the thematic categories that emerged from the analysis of cultural games: a) Singular and Holistic approaches to games, b) Interrelated and performance-based games, c) intercultural games, and d) intergenerational and accessible cultural games. (Addo, Citation2009; Nzewi, Citation2007). In transcribing each cultural game, a striking feature emerges that several games fit across curriculum levels, and some work better at one level than another. Table summarises the 2019 mathematics curriculum and where the games fit in grade-level culture-sharing groupings (See Appendix B).

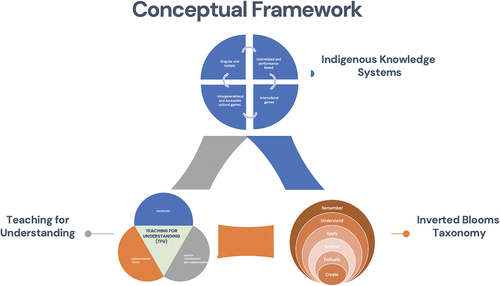

Finally, we outlined instructional procedures for one game, which provides implications for teaching practice. Rather than use a hierarchical lens from Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objective, we recognised Indigenous Knowledge Systems as central to curriculum alignment and the practises we outlined. Airasian et al. (Citation2001) revision of Bloom’s original taxonomy connects cognition and knowledge activities in a hierarchy—remember, understand, apply, analyse, evaluate, and create. However, in 2009, Wineburg and Schneider challenged the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, arguing that it may be pointing in the wrong direction. Their argument makes sense in the Indigenous knowledge systems space. Therefore we paid attention to assessment models and their alignment with learning objectives using the conceptual framework in Figure . Verifying each game placement on the chart with a discussion of assessment/objective relationships in the curriculum increased intercoder agreement and, therefore, the dependency on the study. Our curriculum topics are predefined codes, and our coded learning objectives inform game selection. The themes that emerged from exploring the goals, games, and assessments helped us verify the curriculum documents’ alignment and the suitability of each game for teaching mathematical concepts. Below is a layout of our content and document analysis which led to our design of the instructional process. We note that the process was iterative, moving back and forth in review and confirmation. (See Figure )

7. Concepts in the 2019 Ghanaian mathematics curriculum

Ghana’s 1961 Education Act formalised and regulated education in the country and set the stage for various education reforms (1974, 1987, 2007 and 2019) enacted to improve education in the country. In 2019 the Ghana Education Service ratified a new curriculum for primary or elementary and junior secondary schools, premised on the 4Rs of Reading, writing, arithmetic, and creativity. Mathematics, arithmetics, operations on arithmetic, and creativity were the reasons for lower and upper primary schools’ mathematics curricula (NaCCA, Citation2019). The intent was to provide adequate mathematics education for all Ghanaian children to contribute effectively to national development. The objectives of the mathematics curriculum are to address, Problem Solving Skills; Critical Thinking; Justification of Ideas; Collaborative Learning; Attention to Precision; Cultural Identity to Precision, and Pattern recognition. Ghana’s 1961 Education Act formalised and regulated education in the country. Unlike the previous ones, the 2019 reforms included workshops for teachers to implement the curriculum successfully. The researchers observed that teachers had moderate to high self-esteem after the workshops (Agormedah et al., Citation2022).

Content-wise, the 2019 curriculum constructivist curriculum has four primary content areas—Numbers, algebra, geometry and measurement, and data. Teachers introduce whole numbers, operations on real numbers, and their fractions under numbers. Under algebra, teachers teach patterns and relationships, equations and inequalities, functions and unknown expressions. Geometry and measurement have four sections lines and shapes, measurements and geometrical reasoning. Data introduces collection, organisation, interpretation and analysis of data and chances. (NaCCA, Citation2019). Teachers use problem-solving and creativity skills in learners to teach these mathematical concepts.

8. Games with mathematical concepts in the curriculum

The curriculum provides ample opportunity to introduce cultural games as a critical teaching strategy for children’s understanding of mathematical concepts in the four curriculum areas—Numbers, algebra, geometry and measurement, and data. The questions we asked were, Which games address numbers, algebra, geometry and measurement, or help children learn about data? While we drew from various sources, we also wanted to give the reader access to online audio-visual documentation of these games. Of the twenty three games selected for this project, descriptions of twenty are in Appendix A and three are presented below.

Pilolo (Pronounced Pee low low)

This game involves a stick (depending on the number of players), non-participants and players. The children first choose a leader, and the rest become subordinates. The leader picks up a stick, breaks it into equal lengths, and hides them from the subordinate players whose eyes are closed. Second, the leader shouts, “Pilolo,” and the subordinates will respond, “Yaafo bε mli” which translates to “one cannot cry, or there’s no crying in this game”. After the response, players must find the hidden sticks individually and report to the designated point. The first player to find a stick secretly runs to the selected point and gives it to the game’s leader without showing or telling the other playmates where they found it. If players bring a piece which was not part of the original stick, it’s not counted (not part). Every player needs to find their own sticks. The leadership role rotates after players find all sticks. The game ends when everyone has a turn playing leader and subordinate.

The purpose of this game; is to bring about the quest for curiosity, exploration and research. In the European setting, children used it in their hunt for treasure and inspired the book “Treasure Island”. In Ghana, this game encourages persistence in search of what we want for with patience and resilience, we will prevail.

Chempε. (Pronounced Chaim pair)

Chempε or Kyempε means divide into two equal parts. Children who agree to play this game must separate anything they are holding into two equal parts upon the request of the other player. In some contexts, a child will call out to you, “Chempε,” and you will need to share your lunch or anything in your hands. In this seasonal game, a child says “No Chempε” quickly before an approaching child can ask them to divide their meal or possessions. It is a game of chance and anticipation.

Oware (Pronounced or-wah-ree)

“Oware” known as mancala in other countries, can be played by digging twelve holes in two rows in the ground to represent the wells for pebbles. Carving the holes of hollow shapes or wells (two rows with six holes in each row) out of wood is the most common version we see today. Then, the players use forty-eight palm kennels or hard, dry sizable seeds or even stones or pebbles to play. To begin playing “Oware”, each of the twelve holes has to be filled with four palm kennels. The game requires two players. While the rules for this game are quite different from place to place, the game’s goal is to capture the pebbles of your opponent. Moving anticlockwise, each player takes turns sowing seeds in the wells of the game. If a player places the last kennel in turn in the opponent’s well and brings the number of kennels to two or three, they may capture the seeds. The player who seizes over half the seeds wins the game. It requires intellectual abilities to defeat your opponent.

9. Discussing the implications for curriculum and instruction

9.1. Cultural games in learning engagement

The Indigenous Knowledge Systems approach propounded by Nzewi supports learning engagement within the lesson (Nzewi, Citation2007). Consider the learning engagement when teachers use a cultural game in their lessons. Playing the games draws the children into the lesson, providing practice and enjoyable learning (Fouze & Amit, Citation2017). They make the point that cultural games improve students’ motivation and participation in the classroom. In Appendix C, we have outlined a lesson on fractions using the game Chempε. Here we demonstrate that cultural games are effective as advance organizers for getting the child’s attention in the lesson.

Additionally, in the introduction of this lesson, the children play in small groups, reducing the tendency for didactic teaching (Fletcher, Citation2005). Also, they deconstruct and create knowledge while playing Chempε as the lesson proceeds. The lesson, therefore, begins with the “create” stage of Bloom’s Taxonomy. If learners believe learning is enjoyable, they will successfully make sense of the content knowledge teachers present through discovery learning (D. K. Mereku, Citation2000; Eshun, Citation2000; Fletcher, Citation2018; K. D. Mereku, Citation1998). Consequently, the lesson’s opening encourages learner autonomy and sets the children up for success through holistic experiences (Nzewi, Citation2007).

Also, the lesson highlights Ghana’s unique culture of understanding and creating new knowledge critical for ethnomathematics (d’Ambrosio, Citation2016). Cultural games provide ample ethnomathematical processes for teaching fractions in stage/grade 4 when a teacher prepares a lesson with Chempε in the introduction and early development of the lesson. Students engage in a singular and holistic indigenous knowledge system. As the lesson proceeds, the children “evaluate” and “analyze” their experience, the next two stages of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning (Wineburg & Schneider, Citation2009).

Chempε/Fractions lesson with oranges relies on the children’s indigenous knowledge. They use familiar knowledge on a new playground, the mathematics classroom. They use their hand, heart, and head to play a game passed on to them in their mother tongue (Bhuda & Marumo, Citation2021; Nabie, Citation2008Bishop, Citation1997). The lesson, therefore, connects their lived experience to mathematics learning objectives.

Further, the students create new knowledge by discussing the game and showing foundational learning (Wineburg & Schneider, Citation2009). With the teacher’s help, students break down the game into cases to discover fractions in the game they play. Students engage in some quantification and the breaking down of their creation. Additionally, they create knowledge for themselves in the lesson while making sense of the various forms of fractions in the game (Wineburg and Schneider). When the teacher provides examples to check for understanding, the students apply their new knowledge to solve related fractional problems. Their ability to apply this concept to solve problems indicates their understanding. Teachers can then confidently ascertain the lesson’s goal that students know, like fractions and how to add them. The students construct knowledge with Chempε, a cultural game they learn individually, affirming their child’s development in a cyclic process emphasizing students’ backgrounds and learning development (Nzewi & Nzewi, Citation2007). Additionally they play in small groups encouraging groups learning the curriculum demands (Eshun, Citation2000)

10. Guided discovery through cultural games

Mathematical concepts are present in our everyday lives, and we use them without realising the mathematical concepts we absorb. If teachers highlight these processes, children will discover many mathematical concepts they learn during play, the point of ethnomathematics (d’Ambrosio, Citation2016). For example, when we mix ingredients while preparing food and measure angles when constructing our homes, we deliberate over ratios and proportions. Armah (Citation2021) argued for making Ghana a mathematical friendly nation, confirming our point that mathematics is every where. Cultural games offer opportunities to, through guided discovery, these everyday experiences to teach mathematics.

The Ghanaian cultural game “Pilolo” offers constructivist-based teaching approaches the national curriculum encourages in Ghanaian schools (NaCCA, Citation2019). Embedded in Pilolo are mathematical concepts such as addition, subtraction, and probability. For a deep understanding and appreciation for mathematics while preserving and promoting Ghanaian cultural traditions. Here again, when playing Pilolo develop their cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skills while having fun (Nabie, Citation2008). We will describe the discovery learning process in Pilolo.

The game of Pilolo involves three sets: sticks (the number of which depends on the number of players), non-participants, and players. First, the children choose a leader, and the rest become subordinates. By selecting leaders, they are exhibiting learner autonomy as well as they sense of fairness (D. Mereku & Mereku, Citation2013). The leader creates five columns, with the first containing the names of all participants and the last containing the sum of the scores between the first and last columns. The leader then picks up a stick, breaks it into equal lengths, and hides them from the subordinate players, whose eyes are closed. The leader then shouts “Pilolo,” and the subordinates respond with “Yaafo bε mli,” which translates to “One cannot cry, or there’s no crying in this game.” Here again, mother-tonge based learning occurs (Ball, Citation2010; Gay, Citation2010; Ladson-Billings, Citation1995; Paris, Citation2012). After the response, players must find the hidden sticks individually and report to the designated point. Therefore Pilolo provide the pratice children need with mathematical concepts (Fouze & Amit, Citation2017).

The first player to find a stick secretly runs to the selected point and gives it to the game’s leader without showing or telling the other players where they found it. That player receives 100 points, the second player 90 points (depending on agreement), and the third player 80 points. If players bring a piece that was not part of the original stick, it does not count. Each player must find their sticks, and the leadership role rotates after all players have found them. The game ends when everyone has had a turn playing leader and subordinate. The winner is the player with the highest total score against their name. Pilolo therefore, relies on chance while providing opportunities for adding, and problems-solving (D. Mereku & Mereku, Citation2013).

In mathematical learning, incorporating games in instruction can effectively engage students and enhance their learning experiences. Educators can use games like pilolo to make learning more enjoyable and foster a positive attitude towards mathematics. Demystifying mathematics with cultural games in the classroom can improve mathematical proficiency, performance, and relevance of mathematical concepts (Anyidoho, Citation2018; Ball, Citation2010; Seudib et al., Citation2020). Using cultural games benefits the individual student, the teacher, the community, and the nation (NaCCA, Citation2019; ESP, 2018–2030).

10.1. Teaching with cultural intention - problem-solving

We have argued that cultural games also support, problem-solving in student learning. One of the rationales of Ghana’s mathematics syllabus is to enhance learners’ problem-solving abilities(MoE, 2007; ESP, 2018–2030). One suggested way to meet this rationale is becoming familiar with Polya’s four basic problem-solving principles (Schoenfeld, Citation2016). The first is “understanding” which aligns with the Teaching for Understanding (TFU) framework of Ghana 2001 curriculum. Once teachers have identified a topic, such as operations in real numbers systems, then they would outline the understanding goals (Eshun, Citation2000). The second stage in Polya’s principles is making a plan, which also connects with the TFU framework focus on defining goals because here teachers build and validate knowledge through this case study of cultural games.

Let us consider oware; for example, four palm kennels need to be placed in each of the twelve holes to start a game of oware. Two players are needed to play. Although the game’s rules vary in different locations, the main objective is to collect more pebbles than your opponent. The game proceeds in an anti-clockwise direction, with each player taking turns to sow seeds in the holes of the game. Anti-clockwise is a direct cultural expression, as we shake hands in Ghanaian, in an anticlockwise direction. Therefore the children are drawing from both their funds of knowledge and are using culturally sustaining practices in their play and learning (Moll & Gonzalez, Citation1994, Paris, Citation2012) If a player places the final kennel in their opponent’s hole, and there are two or three kennels in it, they can take those seeds. The player who captures more than half of the seeds wins. The game requires intellectual skills to outwit one’s opponent.

The Oware game involves an iterative process of devising a plan based on the player’s understanding of the game and executing it. The students, therefore, demonstrate mastery as per TFU framework and performance and execution of Polya’s principles (Eshun, Citation2000; Schoenfeld, Citation2016). The game’s objective is for players to capture more seeds by picking them from a hole. Players go through the cognitive process of finding ways to capture more seeds. When teachers use Oware in the classroom, students can develop an awareness of the fundamental principles of problem-solving and an understanding of mathematical concepts.

Drawing on Gay’s culturally responsive teaching and Paris’s culturally sustaining pedagogy, we argue for identifying and documenting funds of knowledge that mediate the established mathematical pedagogical practices (Gay, Citation2010; Paris, Citation2012). Gay’s responsive teaching is relevant for conceptualizing cultural games as a pedagogical and cognitive tool in mathematics instruction. Also, because Ghanaians centre community culture, we can sustain culture by using cultural games for mathematics learning and signal that we care about our culture (Addo & Adu, Citation2022). For instance, playing Oware can enhance a child’s cultural numeration system. Oware involves placing seeds on a board with two rows of holes, and children can have fun while learning to count in their own language. If a child has a strong foundation in their first language, they are more likely to develop proficiency in a second language more quickly (Ball, Citation2010). Therefore, using cultural games can also benefit language acquisition.

11. Suggestions for future research

Several mathematical concepts in kindergarten to grade three and upper grades need attention. Future research in these areas will support connecting everyday cultural events with mathematical learning. Also, an experimental study using games as an intervention to determine if students’ mathematical proficiency will improve will be another viable future study. It will provide empirical evidence for the value of connecting with culture for student learning. Future research on deliberate attempts to collect games from the area will increase the teachers’ self-efficacy with mathematics instruction and affirm their positive response to the cultural context and student learning autonomy.

12. Conclusion

We play games throughout our lives. There are several established ways of teaching mathematics concepts without games. Using Chempε, a cultural game about fractions, our paper demonstrates the value of games in enhancing students learning of mathematical concepts. We also demonstrate the critical role cultural games play in guided discovery learning, with Pilolo as our example. Oware, the well-knowing pebble game we used to for problemspoving with intention. While several studies have described the importance of games in instruction, the lesson plan in this paper gives teachers a practical example for using cultural games. Also, the description of math-rich games from the Ghanaian culture and where they reside in the curriculum provides teachers with examples of where to utilize cultural games in instruction. Our report highlights the importance of games in improving teacher pedagogy by connecting established ways of teaching maths with innovative strategies with cultural games.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. They included W. T. Martin of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, J. E. Phythian of the University College, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, Lucy Tagoe, Office of the Chief Education Officer, Ministry of Education, Accra, and others.

References

- Addo, A. O. (2009). Reconceptualising African Music Arts: Epistemology and Pedagogy meet.review of meki nzewi, a contemporary study of musical arts: Informed by African Indigenous Knowledge Systems 5 volumes & CD. The World of Music, 51(1), 156–27.

- Addo, A. O. (2013). African Traditional and Oral Literature as Pedagogical Tools in Content Area Classrooms (Vol. K-12, pp. 21–40).

- Addo, A. O., & Adu, J. (2022). Examining the use of folk resources for creative arts education in Ghana’s Basic Schools. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 23(4). Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.26209/ijea23n4.

- Agormedah, E. K., Ankomah, F., Frimpong, J. B., Quansah, F., Srem-Sai, M., Hagan, J. E., Jr., & Schack, T. (2022, September). Investigating teachers’ experience and self-efficacy beliefs across gender in implementing the new standards-based curriculum in Ghana. Frontiers in Education, 7(932447), 1–12. Frontiers Media SA.

- Airasian, P. W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M. C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (Anderson, L.W., Krathwohl, D.R., Ed.). Complete. Longman.

- Anyidoho, A. (2018). Shifting sands: Language policies in education in Ghana and implementation challenges. Ghana Journal of Linguistics, 7(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjl.v7i2.10

- Armah, P. H. (2021). Making Ghana a Mathematics-friendly nation: A Key to our national development agenda. Ghana Web.

- Ball, J. (2010). Enhancing learning of children from diverse language backgrounds: Mother tongue-based bilingual or multilingual education in early childhood and early primary school years. Early Childhood Development Intercultural Partnerships, University of Victoria.

- Bhuda, M. T., & Marumo, P. (2021). The Ndebele indigenous games pertinent to primary school mathematics learning: Why indigenous games are a vital tool for mathematics teaching and learning. Gender and Behavior, 116–124.

- Bishop, A. J. (1997). The relationship between mathematics education and culture. In Opening address Delivered of Iranian Mathematics Education Conference. Kermannshah, Iran. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255590052

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Chikodzi, I., & Nyota, S. (2010). The interplay of culture and mathematics: The rural Shona classroom. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 3(10), 3–15.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

- d’Ambrosio, U. (2016). An Overview of the History of ethnomathematics. In Current and Future Perspectives of Ethnomathematics as a Program. ICME-13 Topical surveys. Springer.

- Eshun, B. A. (2000). Mathematics Education Today. Paper delivered at the 6th National Biennial Delegates Conference of the Mathematical Association of Ghana (MAG), at St.Paul’s Secondary School, Denu.

- Fletcher, J. (2018). Performance in Mathematics and Science in basic schools in Ghana. Academic Discourse: An International Journal, 10(1), 1–18.

- Fletcher, J. A. (2005). Constructivism and mathematics education in Ghana. Mathematics Connection, 5, 29–36.

- Fouze, A. Q., & Amit, M. (2017). Development of mathematical thinking through integration of ethnomathematic folklore game in math instruction. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 14(2), 617–630. https://doi.org/10.12973/ejmste/80626

- Gay, G. (2010). Acting on beliefs in teacher education for cultural diversity. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109347320

- Gyang, S. D. (1979). ’Mathematics Education in the Proposed Junior Secondary School in Ghana’. ( Diploma Dissertation). The University of Leeds, School of Education.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

- Mereku, D. K. (2000). School mathematics in Ghana: 1960–2000. Mathematics Connection, 1(1), 18–24.

- Mereku, D. K. (2010). Five decades of school mathematics in Ghana. Mathematics Connection, 9(8), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.4314/mc.v9i1.61558

- Mereku, K. D. (1998). Education and training of basic school teachers in Ghana. Lokaliseret, 19, 1–17.

- Mereku, D., & Mereku, C. (2013). Ghanaian case study of singing games in ethnomathematics. Journal of African Culture and International Understanding, 6, 16–24.

- Moll, L. C., & Gonzalez, N. (1994). Lessons from research with language-minority children. Journal of Reading Behavior, 26(4), 439–456.

- Nabie, M. J. (2008). Cultural games in Ghana: Exploring mathematics pedagogy with primary school teachers.

- Nabie, M. J. (2011). Primary school teachers’ mathematical conceptions of cultural games.Sss. International Journal of Basic Education, 2(1), 99–109.

- Nabie, M. J. (2015). Where cultural games count: The voices of primary classroom teachers. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 3(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.18404/ijemst.97065

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment [NaCCA]. (2019). Teacher Resource Pack: Primary 1-6. MoE, NaCCA.

- Nkopodi, N., & Mosimege, M. (2009). Incorporating the indigenous game of morabaraba in the learning of mathematics. South African Journal of Education, 29(3), 377–392. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v29n3a273

- Nzewi, M. (2007). A contemporary study of musical arts: Informed by African In- digenous knowledge systems. CIIMDA.

- Okyere, M. (2022). Culturally responsive teaching through the adinkra symbols of Ghana and its impact on students’ mathematics proficiency. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation University of Alberta Canada.

- Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12441244

- Schoenfeld, A. H. (2016). Learning to think mathematically: Problem solving, metacognition, and sense making in mathematics (Reprint). Journal of Education, 196(2), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205741619600202

- Seudib, E. N., Kwasi, S. A., & Dassah, F. T. (2020). Math-Phobia and mathematical performance challenges, a linguistic ramification of colonized nations of Africa: Evidence from Ghana. International Journal of Education Humanities and Social Science, 3(4), 95–120.

- Williams, G. A. (1976). The development of a modern mathematics curriculum in Africa. The Arithmetic Teacher, 23(4), 254–261. https://doi.org/10.5951/AT.23.4.0254

- Wineburg, S., & Schneider, J. (2009). Was Bloom’s Taxonomy pointed in the wrong direction? Phi Delta Kappan, 91(4), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171009100412

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage publications.

Appendix A.

Cultural Games

Aanto wakyire [pr.: antour waachir]

A group of players sit together in a circle to play this game. One player, the moderator, runs around the outside perimeter of the circle, chanting ”aanto wakyire oo‘. The children sitting in the circle respond, ’Yee, yee,” while clapping to the beat of the chant. The moderator leaves a cloth or object behind an unsuspecting player and then runs around the circle again. They aim to hit the player on the back before they know anything is behind them. All the children laugh. If the unsuspecting child notices the object, they pick it up and run after the moderator, and the excitement mounts. The moderator then speeds to sit in the open spot. The game continues till there is a mutual decision to end it.

Alasa (Pronounced Ah- lah- sah)

Children use seeds of a fruit called Alasa or the African Star Apple for this game. Before the game begins, players agree on the number of seeds they will each need for the game, for example, 5,10,15,20. They then clear the ground floor so that the sand wouldn’t impede the movement of seeds and dig a hole in the middle of the ground to serve as a radius point. They measure every player’s side from the spot by counting the thumb and first finger length of 3 to 5. Each player batches the seeds into the hole with the thumb and first finger, one by one, until everyone plays. Those players whose Alasa seeds couldn’t enter the radius point will try again until they can make the shot. The measurement accuracy is central to the game’s success, as each seed must enter the hole simultaneously.

Alikoto(Pronounced Ali kow tow)

This spinning game requires at least two people to play. Players spin the Alikoto (a spinning top) and wait to see whose Alikoto falls flat on its head. It is best to play the game in the sand. The one with the Alikoto that falls first will receive a hit on the hand of the one whose Alikoto remains spinning. Alikoto tsεmɔ en ji mɛni? In Ghanaian Language, Ga Adangbe means ”What is spinning the top?”

Ampe (Pronounced Arm pay)

Ampe game involves clapping your hands, jumping and throwing your feet. Even though primarily girls play ampe, boys join in the game for fun too. The goal is to predict what the other player will do when they thrusts one foot out. At the start of the game, two or more children may choose evens or odds. The left foot must meet the right foot of the other player (evens) or the left foot of the other player (Odds). The children also keep scores, counting in tens, hundreds, and thousands. The child who reaches the predetermined number first wins the game.

Change Your Style

In the creative movement game, the moderator calls out, ”Change your style,‘ and the rest of the children make a new move. And they stand stiff when the moderator says, ’be like that”. The game encourages following directions and coming up with spontaneous creative movements. At the same time, some actions were humourous, but the children developed the habit of obeying commands.

Chaskele

In this game, the players put a basket or bucket in the middle of a place or field. One person uses his legs to count to a particular agreed point for all players. At the same time, others do it by jumping length to an agreed point. They draw a horizontal line through that point which can cover everyone too. All the players of this game stand behind the line drawn and throw their cornsticks into the basket. All those players who succeed in their throws will stand aside till all players finish throwing their cornsticks on their first throw. Those who fail in their first attempt will continue to throw, while their cornsticks will be battered by those who are successful in their first attempt until everyone can win their throw. And they begin the sequence repeatedly until they get tired and decide to stop. Children learn not to ever give up mentality because one has to throw till one wins the throw. The game is akin to internationally recognised cricket.

Counters ball.

The counters ball is another reproduction of a soccer match but played with bottle tops, turkey berries or pebbles, a slate or a smooth floor, and two players. A rectangle is drawn and designed like a football pitch on slate. Players arrange the counters (Bottle tops) players on the rectangle. Each player moves the counters to hit the turkey berry or pebble. After a given duration, the player who scores the most in the goalpost wins.

Four corners/Four Poles

We play ”Four Corners” in an open space or uncompleted building room. There were at least four players and a moderator. First, we label the corners of the room, or the people standing with four corners perpendicular to each other, ”A, B, C, and D.’ The moderator is blindfolded and stands in the middle of the room and calls on any of the alphabet labels. The player standing at that corner leaves the game when they hear their alphabet. They repeat the process till the last person still at the post becomes the winner. One player throws the ball into the square in the four poles version. After the ball touches the ground, any player may kick the ball once and can only play again after another player has kicked the ball. When the ball enters a player’s goal, they are eliminated from the game and replaced by another player waiting their turn.

Small poles

Small poles, the local Ghanaian version of soccer, is a culture. Children, usually boys, place two blocks of cement 3 or 4 ft apart and set them up as goalposts in any open space. There is no goalkeeper; therefore, the game is populist and brings together the community, young and old. You will find the game of small poles played on school playgrounds, yards, and markets .When there is a foul against an opponent and it is close to an opponent’s goal poles, it is a penalty. The referee stands within the goal poles of the defending team and measures 15 feet towards the center. One player from the attacking team puts the ball on the 15th foot and kicks the ball towards the defending goal poles.

Stay” (game)

Stay,”is a street football game, involving at least two people, which startswith ‘total’. Either hands or legs may be used for totals. A player bounces the football at the back of the hand or top of the foot without making it fall. Each person will select and play ‘total number’ with a football. After everyone’s number is counted and recorded, Player A will play the ball with the highest frequency to play far away so the person with the lowest count can go and catch it. When player B catches the football, he will run toward all players with higher totals. Then, asPlayer B approaches a player with a higher count, player B says, ”stayshould catch you there,” and he will throw the ball; when the player does not hit it with his leg, this player takes over from the one with the lowest count. When a player passes the ball to another player, they must stay motionless with arms folded behind them and plays the ball with their head. They lose the game if you move while heading the ball or when it is passing by. Concentration, therefore, is needed on each participant's part to remain in the game. Watch the street football version here.

Tuumatu

”Tuumatu‘ is the Ghanaian version of Hopscotch. It starts with players drawing lines and half-circle shapes on the ground. Then the players fill a small polythene bag with sand and throw it to a point. The goal is to jump to the end and return, avoiding the square with the polythene bag. In another version, the player jumps with the bag tied to their legs and ensures her leg doesn’t touch the line drawn, or else she is out of the game. The player hops on one leg until they can complete the task successfully. The player who hops successfully to the end blocks a player from stepping into the rectangle or ’home.‘ It requires great care and balance. ’Tuumatu” is now a December festival in James Town, Accra, Ghana celebrating children’s games.

Where to find these Cultural Games Online

Antoakyire (https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=549437956420478), 7 memorable games from Ghana: https://www.changeforghana.org/post/7-memorable-ghanaian-games (Alikoto, Oware, Chempε, Zanzamaa, Alasa, Pilolo, Chaskele) 10 Exciting Ghanaian Childhood Games that we Absolutely need to bring back. https://kuulpeeps.com/2021/07/08/10-exciting-ghanaian-childhood-games-that-we-absolutely-need-to-bring-back/pop-culture (Alikoto, Pilolo, Kpitingε, Counters Ball, Zanzamaa, Pampana, Rubber Tie Throwing, Kalo, Chaskele Tumatu) 20 Memorable Games: https://gh.opera.news/gh/en/sports/13dade732607df68ceeefbf975ec7add (Chaskele, Kpitingε, Counter’s Ball, Ampe, Alikoto, Pilolo, Oware, Ludo, Tuumatu, Chempε, Zanzama, Rubber Tie Throwing, Kalo, Nkuro, Practical Numbers, stay, Anto nkyire, police and thief, Konko car, bamboo fireworks). These are 10 Childhood games in Ghana we can’t forget. https://www.pulse.com.gh/news/local/old-times-nostalgia-these-are-the-10-childhood-games-in-ghana-we-cant-forget/1cdzc5g (Chaskele, Maame ne Paapa, Alikoto, Pilolo, Practical Numbers, Ampe, Counter’s Ball, Kpitingε, Zanzama, Kyin dan ho (go around the house). Seven games you played if you were born and raised in Ghana: https://braperucci.africa/7-childhood-games-you-definitely-played-if-you-were-born-and-raised-in-ghana/ (Ampe, Change your style, Tsaskele, small poles, Zanzama, mama ne dada, police and thief) Ghana’s Most Entertaining Childhood Games That Is Being Forgotten: https://gh.opera.news/gh/en/digital-technology/e1e871ae51448bfe18c8b0e1f8c15ad5 (Alikoto, Oware, Pilolo, Chaskele, Ludu, Chempε, Counters Ball, Rubber Tie, Ampe).

Appendix B

Table A1. Cultural Games that support learning Mathematical Processes

Appendix C

Lesson Plan

Academic Level: Class/Grade 4

Topic: Understanding Fractions Content Standard: Demonstrate an understanding of strategies for comparing, adding and subtracting fractions (same denominator, or one being a multiple of the others) Objectives: Students will 1.Play Chempε (kyempε), a Ghanaian cultural game utilising fractions 2.Describe the mathematical functions that they experienced while playing Chempε (kyempε). 3.Identify and add like fractions as individuals and in groups after playing Chempε (kyempε). Instructional materials ●oranges or any other fruit ●a piece of paper for each group and a pencil Relevant Previous Knowledge (RPK) Students can count, add and subtract integers Introduction (5–8 minutes) - Create ●Begin this lesson by introducing (or reviewing) the process of playing Chempε (kyempε). ●Students will be assigned to small groups of 6 or 8 players, depending on the class size. Each group gathers in one of the four corners of the classroom to play Chempε (kyempε). ●Each group received three or four fruits and a sheet of paper for recording information. Game Description: Chempε or Kyempε means divide into two equal parts. Children who agree to play this game must separate anything they are holding into two equal parts upon the request of the other player. In some contexts, a child calls out to you, ”Chempε,‘ and you need to share your lunch or anything in your hands. In this seasonal game, a child says ’No Chempε” quickly before an approaching child can ask them to divide their meal or possessions. It is a game of chance and anticipation.

Development of lesson (10–15 Minutes) Evaluate and Analysis During the game, serial or multiple Chempε (kyempε) situations may occur. Students record all the unique cases and apply the addition whenever possible.

First case (students with only one Chemp3)

Student describe what happened during the game:

Students verbalise their thoughts on their cases, proving that when a whole is divided into equal parts, the total number of equal parts goes to the bottom of the fraction (the denominator), and the number of parts of the whole goes to the top of the fraction (the numerator). Define the terms ”fraction,‘ ’numerator,‘ ’denominator,” and any other challenging words in the student’s home language.

Second Case (students with only two or more Chempε of the same item)- Sub division

Kwadwo, for example, is aggressive and acquires three halves of oranges. The students consider how many oranges he has. Ask the students with these situations to come in front to illustrate how they will put the halves together and count the number of oranges. Expected response:

Transfer of learning: (Apply) Group work/Same denominator: The teacher solves these questions with students.

Assessing the learning: Individual work (Bloom’s Understand)

Closing the lesson: (3 minutes) (Bloom’s Remember)

Review work completed using questions.

Introduce homework: Encourage students to play the game, record and add what they will learn from playing it in their notebooks.