Abstract

Pointed polysynchronous interactions (PPIs) were initiated by the participants of this study to promote more adequate interactions between learner–learner, learners–teachers, and learners–learning materials in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) science hybrid learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This photovoice study spotlighted Indonesian primary school teachers’ initiatives in helping their pupils enhance their English proficiency while learning mathematics. We investigated their efforts for scaffolding when teaching mathematics to the first graders, with a particular focus on translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing. As collaborative research, this photovoice study involved a mathematics’ teacher and her co-teacher to provide photos of how translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing were practiced within the PPIs. The teachers described their photos using the SHOWeD technique before we analyzed the data thematically, then returned them to the teachers for validation. Results showed successful practices of translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing, while some challenges arouse because of time limitation for hybrid learning recommended by the Indonesian government. Translation enhanced the students’ academic and social performances but required longer time of implementation. Meanwhile, trans-semiotizing was advocated to strengthen the teacher’s translanguaging because of the students' English proficiency. Feasibility of alternating L2 and L1 in interaction and connecting them with semiotic resources to negotiate meaning are suggested to practice if hybrid learning should be conducted continuously during new normal.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The adaptation of pointed polysynchronous interactions (PPIs) in Content and Language and Integrated Learning (CLIL) refers to the implementation of polysynchronous interaction (PI) in the hybrid learning environment, enabling students to engage in dynamic interactions with their teachers, peers, and learning materials. PPIs achieve this by leveraging both synchronous and asynchronous modes of delivery, utilizing available school devices to their fullest potential. For instance, a teacher may use his/her personal mobile phone with a tripod to point to a specific activity, allowing remote students to access it. The implementation of PPIs in the CLIL classroom requires the teacher to dedicate a significant amount of time to inviting students’ engagement in activities conducted in English. By practicing translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing, PPIs can enhance CLIL lesson interactions, with a dual focus on content and language, especially for the first graders.

1. Introduction

Polysynchronous interactions (PIs) introduced by Dalgarno (Citation2014); Dalgarno and Webster (Citation2015) have attracted participants of this study to adapt it to implement Indonesian Pembelajaran Tatap Muka Terbatas (PTMT) or limited face-to-face learning, as part of the transition from forced remote learning to new normal situations due to the COVID-19 pandemic. PTMT allowed only 50% of student total numbers in the classroom to attend face-to-face learning and hybrid learning was considered the most feasible practice to carry out. This unexpected new form of learning environment in Indonesian schools proved hard because of the teachers’ lack of expertise to practice it. With one group of students participating in face-to-face learning at school, while the other group learns remotely from home, interaction patterns are vital for young learners. However, the learning engagement in all sessions should resemble the traditional face-to-face learning and prevent them from learning loss (Kim et al., Citation2021; Safira & Ifadah, Citation2021).

While it is connected to the specific practice of recent hybrid learning situated in grade one CLIL mathematics classroom, PPIs were an adaptation of PIs to provide opportunities for students—teacher, student—student, students—learning materials to facilitate dynamic interactions by using English as a vehicular language for learning. PPIs, as designated by the participants of this study, aim at allowing the dynamic interactions within two modes of delivery by maximizing the existing devices provided by common Indonesian primary schools. The devices were (1) a desktop computer, connected to an LCD screen, for running the remote class, (2) a laptop that was pointed to the students in the classroom, and (3) a teacher’s personal mobile phone with tripod. This initial practice was piloted to gain interactions so that remote students could feel the display of specific activity in the classroom. When the mobile phone’s camera was pointed to specific activity, students in the classroom and at home could get the access to it. Moreover, specific standard requirements of hybrid learning during the pandemic suggested by Ali (Citation2020) should be applied. It requires significant learning time to provide attention to the students within two delivery modalities and manage them to engage in interactions. To make it works, the teacher should make the learning interactive as both the teacher and students need to participate in the teaching and learning activities vigorously to encapsulate the unique learning opportunities, like today.

Seminal works related to CLIL for young learners had contributed to strategies of using proper English as a medium of instruction to gain success in learning content or subject matter (Anderson et al., Citation2015; M. D. P. Agustín Llach, Citation2014; M. P. Agustín Llach, Citation2017; Y. Coyle & Roca de Larios, Citation2020). They provoked arguments about linguistics factors to support the achievement in English medium classrooms vary as each claims to be the most powerful one. Based on the current circumstances, multiple varieties of translations, translation and translanguaging, as well as translanguaging and trans-semiotizing have been acknowledged as ways to help students achieve new knowledge (Canepari, Citation2020; Chen et al., Citation2021; Darvin et al., Citation2020; Fernández-Fontecha et al., Citation2020). However, systematic scaffolding strategies to achieve right balance of cognitive and linguistics demands to amplify the young learners’ learning in the CLIL classroom (Ellison, Citation2019; Liu & Fang, Citation2020) during the forced-remote learning as well as transition to new normal had not been explored extensively.

Accordingly, simultaneous interactions of learner–learner, learners–content, and learners–teacher through face-to-face, asynchronous online, and synchronous online communication (Ruiz-Alonso-Bartol et al., Citation2021) using English as a medium of instruction in CLIL mathematics class should be well targeted. Young learners in primary schools should be facilitated by the activities that meet the learning goals and accommodate their learning style. The scenarios implemented by the participants of this study help explain the language scaffolding in terms of successful practices, challenges, as well as prospects of translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing to enhance PPIs. Hence, if learning should be conducted continuously throughout two modes of delivery, this study should contribute to strategies of providing the most convenient language scaffolding to young learners in CLIL mathematics classes by encouraging their active engagement.

With this in mind, systematic scaffolding strategies in learning CLIL mathematics for young learners through translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing should be investigated, especially in specific settings such as PPIs. Furthermore, this photovoice study aimed at investigating the efforts of a CLIL mathematics teacher and her co-teacher to scaffold their students’ significant aspects of their mathematics learning by alternating between using L2 and L1 while maintaining PPIs. This study was conducted to answer the question; “How is PPI carried out in CLIL mathematics hybrid learning by translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing?”

2. Literature review

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is an approach for teaching the students content subject through additional language or the language that the students do not use daily with dual focus on language and content (D. Coyle et al., Citation2010). In primary school level, CLIL potentially supports the young learners’ second language acquisition (Serra, Citation2007) by gaining significant progress in vocabulary and understanding in new concept to be performed in tasks with different cognitive demands (Tragant et al., Citation2016). Particular to mathematics subject taught using English as a medium of instruction, using L2 in alternation with L1 is a major issue as students are demanded to be able to understand mathematic knowledge both in L1 and L2 (Serra, Citation2007). According to Valdés-Sánchez and Espinet (Citation2020), interactions in a CLIL classroom involve the content to teach, the language(s) to use, and the conversation leader. In line with the statement, Liu (Citation2020) emphasized the importance of students’ engagement in dynamic flow of multilingual and multimodal interactions in CLIL. Hence, interactions in CLIL classrooms that rely on face-to-face peers’ collaboration as well as in remote classrooms during the COVID-19 pandemic have been extensively studied.

When the class goes hybrid, potential activities that encourage interactions of face-to-face students with those in the online synchronous classroom are essential. This invites effective and engaging interactions between student–student, student–teacher, and student–learning materials. Polysynchronous interactions proposed by Dalgarno and Webster (Citation2015) could make it happen due to potential scenarios (Oztok et al., Citation2014) of how polysynchronous communication is in practice and emphasized on students’ engagement. Polysynchronous interaction occurs through technical functionality that flows flexibly and simultaneously between asynchronous and synchronous possibilities, in line with the users’ specific needs (Oztok et al., Citation2014). Attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, the implementation of polysynchronous interaction depends on the school and students’ access to technology and internet connection. When learning is switched to digital, Xie (Citation2020) proposed an emphatic design by incorporating four types of engagement (i.e., behavioral, cognitive, affective, and social engagement) and three contextual features (e.g., physical environment, technological, and social features).

Dalgarno and Webster (Citation2015) illustrated how some university students implemented polysynchronous learning using Adobe Connect for the online synchronous mode of delivery and in the designated school focused on promoting essential information and activities should facilitate the learning without exceptions. The teachers adapted the concept to provide equal attention for students who attend the class face-to-face and online and simultaneously experience learning mathematics and English. As polysynchronous interactions challenge the teachers’ pedagogically and technologically (Mayer & Sekayi, Citation2018), it requires co-teaching since teaching management should resemble the face-to-face setting (Lohmann et al., Citation2021), focusing on the importance of teaching expectations, modeling the pertinent behaviors, as well as providing accurate feedback to the students’ learning. Substantially, Yang and Yang (Citation2021) observed that social participation for students in the CLIL classrooms was urgent, and they predicted some potential consequences if conducted remotely during the pandemic.

In an English medium classroom, PPIs could involve both the utilization of technology and the languages as communication vehicles. Several translanguaging studies have shown that bi/multilingual are given agency to use various linguistic and semiotic resources creatively and critically and construct new meanings and new configurations of language practices through everyday interactions (Choi, Citation2020; Wei, Citation2018). In mathematics classrooms where English is the medium of instruction, like in bilingual, EMI, or CLIL context, the teacher should consider students’ linguistic abilities as valuable resources for appropriating mathematical understandings (Garza, Citation2017). The teacher plays a critical role in the mathematics class when the students do not use the medium of instruction daily. Therefore, some practices evidence translanguaging as a powerful tool to mediate understanding instead of repetition of questions like, “How do you say … … in English?” rather than the translation of finding equal wordings mentioned in L1 to L2. Translanguaging practices may involve translation which is traditionally applied with monolingual ideology when individuals need to convey message from one language to another in specific contexts. Translation plays a vital role in encompassing both the process of moving from one source to another and the result of that process, while translanguaging is always a living practice and process, never a finished product, and has diverse temporal fluxes (Baynham & Lee, Citation2019). Thus, translanguaging moves vertically across different languages, registers, modalities, and so on, whereas translation travels horizontally towards a particular product’s end.

Currently, translanguaging is the most popular practice among non-native speakers of English as a new paradigm to describe the complex multilingual learning and multimodal practices that occur in the communication process (Liu & Fang, Citation2020). It provides opportunities for both non-native English-speaking students and teachers to communicate more intensively without any burden in using only English as a medium of instruction in curricular subjects such as mathematics and science. The role of the home language in facilitating the students’ mathematics learning was explained by Schüler-Meyer et al. (Citation2019), who perceived that home language is a resource for mathematics learning in various ways, such as participating in mathematical discourses, activating everyday out-of-school experiences, and upgrading resources for meaning-making processes. Tai and Wei (Citation2021) explored that teachers and students could work together in negotiating a new knowledge in bi/multilingual classrooms so that mathematics teachers could switch the language flexibly between the students’ home languages and English.

Specific for CLIL classroom in primary level, trans-semiotizing, which focuses on linking the language and various semiotic resources to activate the teacher-learners interaction in daily context (García, Citation2018; García & Wei, Citation2014; Wei & Lin, Citation2019) is proper to fulfill the needs of teacher’s and students’ active interaction due to the young learners’ short attention span. According to Lin and Wu (Citation2015), trans-semiotizing played a critical role in students’ meaning-making process. During face-to-face learning, Wei and Lin (Citation2019) urged trans-semiotizing through visual, prosody, gestures, or bodily movements. In the same vein, Liu (Citation2020) exemplified that translanguaging/trans-semiotizing is relevant when the teacher used subject-related words for teaching science both in L1 or L2 by connecting them to the semantic resources, respectively. To the purpose of remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic using social media, Chen et al. (Citation2021) advocated texts, emojis, pictures, and audio as semantic resources used for the teacher–student interactions, while Michel and O’Rourke (Citation2019) endorsed linguistics and semiotic resources for class interactions.

A study related to the digital instruction for promoting content knowledge during the pandemic had been elucidated by Metscher et al. (Citation2021), focusing on the digital practices by modeling activities through online synchronous platform’s facilities to engage and scaffold the learning. Chen et al. (Citation2021) specified semiotic resources for learning conducted through social media. Michel and O’Rourke (Citation2019) suggested more practical evidence about integrating linguistic and semantic resources to activate teachers’ and students’ interactions. Contrasting to the previous data, Lohmann et al. (Citation2021) exposed more specific classroom management for teaching young learners within the hybrid environment to maintain best practices during face-to-face learning before the pandemic by explicit teaching expectations, comparing teaching practices before and during the pandemic, and motivating the students’ learning by providing feedback. Nevertheless, the polysynchronous interactions to accommodate the students’ learning during the transition to the schools reopening post-COVID-19 pandemic have not been published adequately. Dealing with the currently limited face-to-face learning, the teachers’ understanding of students’ learning needs will lead them to choose the most appropriate delivery modes. The steps suggested by Dalgarno and Webster (Citation2015), Oztok et al. (Citation2014), and Ali (Citation2020) were encountered by teachers in one of the internationally tailored primary schools in East Java Province, Indonesia. To fill the gap, the experience of the Indonesian primary school mathematics teacher and her co-teacher in practicing translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing within PPIs during the PTMT should be investigated.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research design

This study utilized photovoice as a method (Mulder & Dull, Citation2014; Wang & Burris, Citation1997) to give voices to the young learners’ mathematics teacher and her co-teacher who used English as a medium of instruction within face-to-face and virtual classroom using zoom platform, polysynchronously. Previously known as “photo novella,” it is now known as “photovoice” and used to document the works of Chinese farm workers. Simmonds et al. (Citation2015) have investigated the broader range of photovoice in various disciplines such as health, education, economics, sociology, anthropology, and geography. As for education, qualitative research utilizing photographs for descriptive data is feasible for critically describing the teachers’ or learners’ experience.

3.2. Participants

After obtaining permission from the school principal, the researchers recruited participants to conduct the study. A female mathematics teacher and a female grade one homeroom teacher who taught in International Class Program (ICP) were recruited to share their CLIL mathematics co-teaching by employing translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing during PTMT. They agreed to participate in the study and allow their photos to be published. They also agreed to take photos of PPIs as collaborative researchers. Teacher A was a 23-year-old mathematics teacher who had just started to teach mathematics in grade one ICP class for a year. Graduating from science education, she was assigned by the school to teach science and mathematics because of her ability to communicate and deliver the lesson in English. Meanwhile, Teacher B was a grade one homeroom teacher whose education background was English education. This 37-year-old female teacher had been teaching English for 13 years and co-teaching in CLIL context with the ICP science and mathematics teachers for 10 years. During the PTMT, Teacher B helped Teacher A in conditioning the students for PPIs within face-to-face and virtual settings.

3.3. Data collection and analysis

In voicing the participants’ experience when implementing translation, translanguaging, or trans-semiotizing to maintain PPIs during PTMT, the participants took some photos (Call-Cummings et al., Citation2019; Pierce, Citation2018). Then, they followed the tasks committed to them (Mulder & Dull, Citation2014) that they should take the original photos from their hybrid teaching activities and write the description of each photo based on the teacher’s intention with the image and its meaning. They took photos during the first half of semester one of the academic year 2021/2022 and then narrated them by answering the questions using SHOWeD technique (Capous Desyllas & Mountz, Citation2019; Latz & Mulvihill, Citation2017):

What do you See here?

What is really Happening here?

How does this relate to Our lives?

Why does this situation, concern, or strength exist?

What can we Do about it?

Furthermore, reflection towards the photos was carried out by following three steps adopted from Koltz et al. (Citation2010), which consisted of (1) selecting photographs, (2) contextualizing photos, and (3) codifying photographs. The participants were invited to participate in a group dialog session to present selected photos along with their description related to their scaffolding practices by translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing. During this session, the interviews were carried out (Latz & Mulvihill, Citation2017) to clarify the significant stories behind the photos in order to contextualize the photos. All data selected from the group dialog were codified thematically based on the steps suggested by qualitative analysis to gain insight into the teacher’s experience. The themes emerged after the verbatim data were analyzed thematically (Miles et al., Citation2014; Saldana, Citation2013). In addition, member checking was selected to validate the data of this study at al., 2016; Rallis and Rossman (Citation2009) by returning the data to the participants and asking if the researchers’ interpretations match what they meant to say or do.

4. Results

All selected photos as the data of this study were representing the teachers’ voices about their efforts of scaffolding the students’ learning to practice PPIs during the PTMT. Overall, some lexical objects, such as words and clauses in the photovoices presented in this article, were coded to show reoccurring patterns of the emergent themes and portrayed narratively.

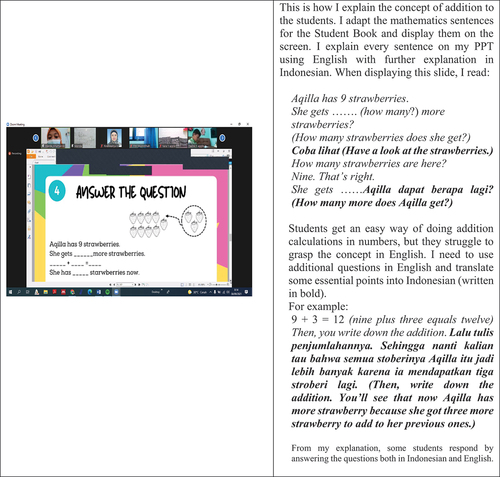

4.1. Free or sense-to-sense translation for words domestication

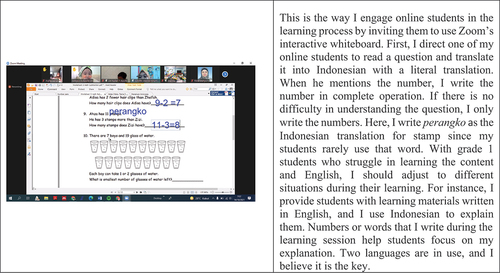

Teacher A asserted that she translated particular words to bridge the students’ understanding about mathematics concepts. For example, she selected literal or sense to sense translation to explain concept of addition to her students. However, she did not use this kind of translation solely because she used pictures to illustrate the mathematical problem in sentences when developing the PPT. She also used Zoom’s interactive whiteboard, which could help her boost student participation, scaffold learning, and maximize teaching time. Figure elucidates this situation.

Figure 1. Teacher A’s photovoice – free or sense-to-sense translation, visuals, and mathematical functions.

A photograph of glasses to illustrate English math word problems involving addition and subtraction shared in virtual classroom

When she read “She gets … … .more strawberries?” with insertion of the question, “how many,” she also pointed to her Zoom’s annotate pen to circle a group of three strawberries that guided students to think about encoding the number of strawberries into number 3. “She gets …… ” was translated to “Aqilla dapat berapa lagi? (How many more does Aqilla get?)” to grab the students’ focus in completing the sentence. It was followed by encoding the explanation into addition as mathematics operation, 9 + 3 = 12. To ensure that all students could get the learning point, the teacher asked them to copy the addition she had written, onto their notebook. “Then you write down the addition,” along with understandable Indonesian translation, Lalu tulis penjumlahannya. Sehingga nanti kalian tau bahwa semua stroberinya Aqilla itu jadi lebih banyak karena ia mendapatkan tiga stroberi lagi. (Then, write down the addition. You’ll see that now Aqilla has more strawberries because she got three more strawberries to add to her previous ones.) The dialogs exemplified by Teacher A clearly explored the way she modified the English language to grab the students’ attention and understanding by free or sense to sense translation. Her translation was used to make sense of her explanation in the L1. This domestication was selected to anticipate the students’ anxiety about misunderstanding the mathematics concept.

4.2. Literal translation for words foreignization and sentence pattern recognition

Teacher A described her photo (Figure ) about how she encouraged her students to translate sentences related to mathematical functions. She provided an example of translating one word that the students rarely used in their daily life, stamp – perangko. Using Zoom’s annotate facility, she wrote the word for both students in the classroom and at home. Furthermore, the student who was assigned to read and translate that sentence continued to translate every English words into Indonesian

The following figure helps explain the use of literal translation.

A photograph of glasses to illustrate English math word problems involving addition and subtraction shared in virtual classroom

Teacher A argued that translation plays an essential role in teaching mathematics to young learners. To clarify her photovoice narrative, Teacher A analyzed that whenever students needed a further explanation for the lesson, she provided additional notes in the Indonesian language and literal translation for specific words. Therefore, both teacher and students used literal translation to grab others’ attention, in different portions. It was clarified by Teacher A when she attended the group dialog session that all students practiced literal translation whenever they were asked to read English sentences and translated them into Indonesian. Meanwhile, she also used free translation for extended explanation needed by the students. The following is her explanation.

In addition to literal translation, I also use Indonesian colloquial variations for providing further explanation for my students. The literal translation is for keywords, while free translation to Indonesian colloquial variations is to clarify the explanation for mathematics context. In contrast, students constantly use literal translation to translate English sentences into Indonesian. Explaining the mathematical operation can also be carried out using English, step by step, without translation. I can do it along with drawing pictures then counting the objects with students. It would be more fun if I could use Zoom’s interactive whiteboard for mutual activity. I enjoy translating and I think my students do too, if it does not take longer time to practice. (Teacher A, 20 Oct 2020, Zoom Interview)

From Teacher A’s photovoice and explanation, it was inferred that young learners in an English medium classroom benefitted from literal translation, word-for-word translation, or foreignization since they needed to notice different sentence patterns in both L2 and L1. They could pick up on every phrase that was translated for their expanded vocabulary. Teacher A believed that by translating specific words, she might help her students better understand what they were learning. While her students translate every single word into Indonesian, she helped out to scaffold mathematics learning by decoding what was mentioned by her student on to the classroom or Zoom’s interactive whiteboard. However, she asserted that she struggled to manage the time as much as possible to facilitate her students’ mathematics learning and intensified their engagement.

4.3. Translanguaging and trans-semiotizing

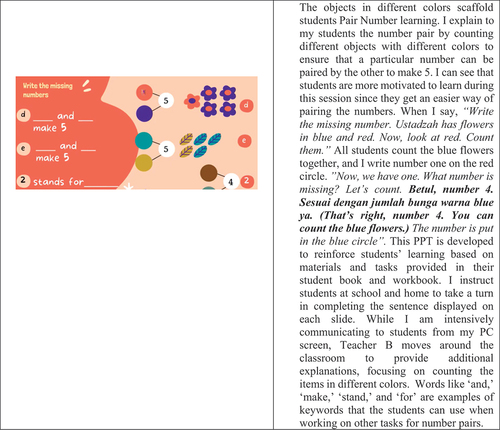

Translanguaging and trans-semiotizing have been believed to empower the students’ learning in CLIL setting. Teacher A affirmed that flexibility in using L1 and L2 in learning mathematics in this setting has made the teacher and learners interact more intensively. Translanguaging and trans-semiotizing serve important pedagogical and social functions. Teacher’s translanguaging functions as a linguistically responsive approach that provides English-Indonesian bilingual students with access to mathematics discourse patterns in addition to knowledge. When presenting Figure in group dialog sessions, she confirmed that she used learning materials written in English for her class, with colorful objects to explain the Pair Number concept to the students in order to invite the students’ interactions. The following figure is Teacher A’s photovoice that elucidates how trans-semiotizing could be practiced within translanguaging lens.

A photograph of a slide from the teacher’s PowerPoint presentation shared to students to find the missing numbers in Pair Number’s lesson

By using visuals, Teacher A convinced that translanguaging was more effective to practice in young learners’ class. She asserted that pictures in different colors had made her students find an easier way of grouping objects based on colors. She understood that her students would pay more attention to objects and colors but simultaneously they could recognize the English words written for explaining the pictures. All of those English words were the keywords for the students’ learning. Her statements were also agreed by Teacher B as she encouraged Teacher A to use colorful objects for some essential reasons.

My educational background in Teaching English to Young Learners (TEYL) is advantageous in supporting Teacher A in teaching mathematics using English. By using colorful objects, I also get an easier way of assisting Teacher A in helping students to understand mathematics using English. For this hybrid learning, a collaboration between a subject teacher and a homeroom teacher like me should be emphasized. (Teacher B, 30 Oct 2020, Zoom Interview)

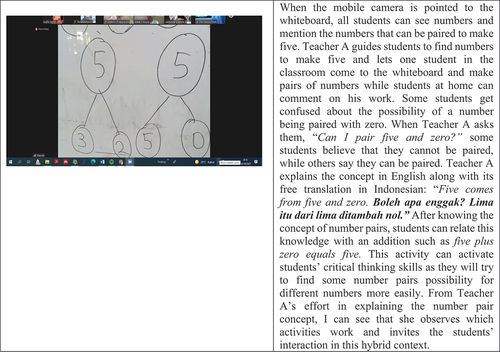

A photograph of teacher’s explanation about Pair Number using Zoom’s interactive whiteboard.

The Teacher B narration (Figure ) evidences the teacher’s ability to provide multisemiotic resources to clarify her explanation and make it work well with students and invite their polysynchronous interaction. By translanguaging and trans-semiotizing, it can stimulate the learners’ agency because it allows them to link the teacher’s explanation with the text or pictures displayed by the teacher. Little change Teacher A made by pointing her camera to the classroom whiteboard for additional remarks towards the number pair and inviting the students’ critical thinking skills was urgent. Her decision to ask the students referential questions like, “Can I pair five and zero?” while writing the numbers on the whiteboard could simplify her explanation. To reiterate her explanation, she posed a referential question in Indonesian to follow her declarative statement that encouraged students not to get confused by the last possibility of pairing a number with zero. “Five comes from five and zero. (Boleh apa enggak? Lima itu dari lima dan atau ditambah nol.)” Teacher A extended Teacher B’s photovoice and explanation that she had to add her lesson plan with notes for alternative activities.

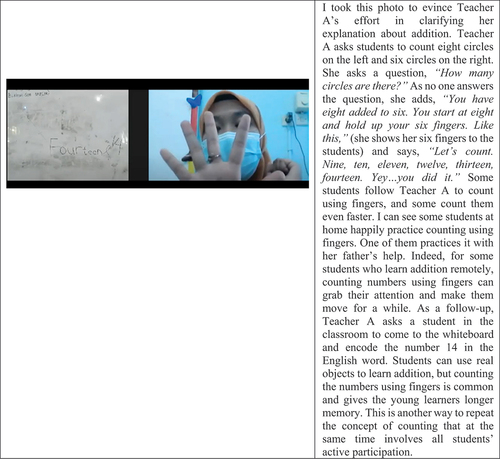

4.4. Bodily movements to reduce language anxiety

Non-verbal semiotics such as bodily movement or facial expressions used by the teacher in explaining the lesson in L2 is urgent for young learners. Teacher A and B agreed that some of their students had English language anxiety as a result of difficulties learning the language, fears of making mistakes, prejudices about the subject, and concerns about English language competition among students. They decided to include bodily movement in addition to translanguaging in their hybrid teaching because of the fact that students needed movements other than sitting still and listening to the teacher’s explanation. Furthermore, they asserted that teachers had to find less threatening activities that support young learners’ motoric skill development. They verified that bodily movements had sustained the class interactions.

A photograph of a female mathematics teacher showing her fingers to count number written on the classroom’s whiteboard pointed by a mobile phones’ camera and pinned to see by the students in both physical and virtual classrooms

Despite a traditional sense of adding by fingers, Teacher B’s photovoice (Figure ) found pure sensation of using fingers to finish addition tasks. She mentioned that some bodily movements like collecting the blocks based on particular mathematics operations like addition and subtraction could not be handled during the pandemic. Both teachers missed the time of involving the students in racing to find the results of addition or subtraction on the card placed on the box. Teachers A and B were happy that Teacher A’s example of counting using fingers had been practiced by almost all students in the classroom of those who were at home. All teachers believed that students could learn better by movements as they picked up personal experience about what they learn. They agreed that students interacted with their teachers and friends more intensively by movements. Therefore, Teachers A and B conformed bodily movements on the notes they would make in addition to their lesson plans.

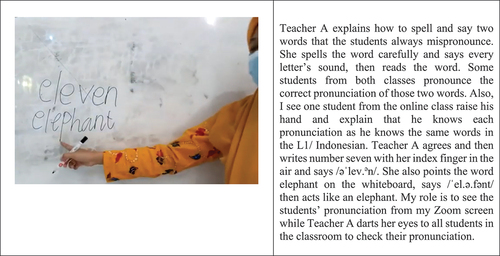

4.5. Phonics session for explaining incongruence between sounds and symbols in L2

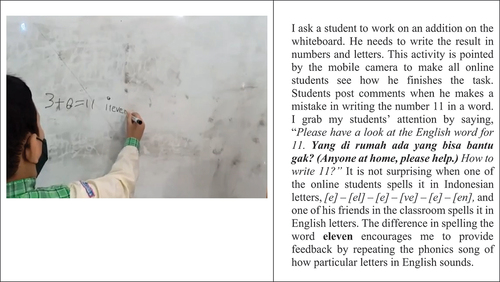

Misspelling and mispronunciation were common for the first graders in the classes taught by the participants of this study. Teacher A found that students encountered problems in pronouncing numbers like six and eleven, and writing number 11 in letters. Figures display the photos taken by the teachers to evidence the students’ misspelling and mispronunciation and how the teacher explained the phonics by trans-semiotizing. The problems occurred due to the incongruence between sounds and symbols in L2 they found during their L1 literacy program. For instance, a student misspelled “eleven” by writing “i-l-e-v-e-n” since the sound/I/is for the letter I in Indonesian. The following photos were taken to explain the teachers’ voices about their efforts to link literacy and numeracy in English.

Figure 7. Teacher B’s photovoice - Teacher A’s clarification about two different words pronunciations.

A photograph of a boy writing the word “eleven” on the classroom whiteboard, which is a result of adding 3 and 8 in math problem pointed by using mobile phone’s camera to see the students in both physical and virtual classrooms.

Misspelling when writing numbers in English letters requires the teacher’s attention and explanation (Figure ). Teacher A argued that literacy and numeracy in the target language are critical for her grade one students. She had to find the most appropriate way to deal with the students’ spelling and pronunciation problems. She inserted a phonics session by singing a phonics song to remind students that letters’ sounds were urgent. Her explanation is as follows:

For hybrid modes of delivery, I should be concerned about the shorter time allotment for mathematics class. All the activities should be effective, so students get their learning portion appropriately. Students’ phonics times could be given more specific times during regular face-to-face learning, like 10–15 minutes using various multimodalities. Now, I have time constraints and should provide corrective feedback to their mispronunciation and misspelling. Inserting an attractive session for phonics, particularly when phonics problems occur, is quite challenging. (Teacher A, 20 Oct 2020, Zoom Interview)

Additionally, Teacher B took a photo of Teacher A’s effort in explaining how to read and write numbers by trans-semiotizing hints (Figure ). It provides students with the idea of co-constructing their knowledge to understand the incongruency of sounds and symbols in L2. While pronouncing the word, Teacher A’s hand wrote the letters to form a word on the whiteboard. She used the classroom whiteboard and pointed her mobile camera to it to get all students’ attention. Teacher B considered this essential as she could see the students’ response and engagement when Teacher A explained steps or processes while writing them on the whiteboard. They listened to the teacher’s pronunciation and imitated it.

A photograph of a female mathematics teacher pointing the classroom’s whiteboard to explain different pronunciation of a word “elephant” from a word “eleven” to her students in PPI

Related to Teacher A’s initiative in scaffolding the students’ phonics learning by trans-semiotizing, the following is Teacher B’s explanation.

Different sounds made by letters in Indonesian and English make young learners misspell or mispronounce certain words. Students need modeling and experience of using the English words. That is why mathematics teachers need to be aware of English phonics. Teacher A is creative because she can make phonics learning easier and more enjoyable. I also hear one student who attends the class from home who practices how to say/əˈlev.ən/and/ˈel.ə.fənt/with the gestures exemplified by the teacher. (Teacher B, 30 Oct 2020, Zoom Interview)

Hence, both teachers agreed that making meaning of her teaching is critical for the students’ simultaneous content and language learning. They acknowledged that incongruency between sounds and symbols in L2 should be one of their attentions. Hints were provided by Teacher A by moving her index finger in the air to form number 11 and acting like an elephant to remind students not to make mistakes in saying and writing eleven and elephant. As a co-teacher in mathematics class, Teacher B worked with Teacher A to succeed in hybrid learning by modifying their teaching for two delivery modes.

5. Discussion

PPI that had been practiced by the teachers in this study evidenced the urgency of mutual interactions within hybrid learning with English as a medium of instruction. How the teachers believed that all students should be equally educated within this mode of learning has aroused the teachers’ agency in using mandatory language of instruction with Bahasa Indonesia as the additional language and semiotic resources as modality for communication. The teacher’s ability in using both languages in conceptual development process is urgent because specific focus on form and content involve linguistic structures in both languages to gain the content meaning (Serra, Citation2007). The participants of this study argued that they had provided simultaneous, engaging instruction for both the online and in-person learners by translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing.

Translation that used to be excluded from language class (Canepari, Citation2020) was still promoted by the participants of this study in addition to translanguaging and trans-semiotizing (Chen et al., Citation2021; Lin, Citation2019; Liu, Citation2020; Wu & Lin, Citation2019) because of the facts that they should find the most appropriate ways of teaching the students without adding to their anxiety on dual focus for language and content learning in hybrid modes of delivery. It was revealed that the teachers could opt to use sense-to-sense translation for words domestication or literal translation for word foreignization to provide learning keywords. Alternating the type of translations is possible for the teacher to grab the students’ attention towards the concept explanation (see Figures ) since all learning materials are written in English. The teacher’s decision to select either one type of translation is determined by how urgent the translation for a process of moving the content from the source to targeted language for all students in different modes of delivery. Meanwhile, the students could practice literal translations for improving their vocabulary and target language sentence patterns recognition. When literal translation is practiced by the students, the teacher can guide them to translate an English text that they read into Indonesian to understand the content or to finish the tasks. Hence, Canepari (Citation2020) conceded that different forms of translation are feasible to be synergized with CLIL approach whenever students need to be motivated and facilitated by experience to practice communication.

Translanguaging, which gains its popularity for its potential of providing the multilingual (including bilingual) students flexibility to alternate the languages used in English medium classroom, to negotiate meaning (Daniel et al., Citation2019; Espinosa et al., Citation2016; Gallagher & Colohan, Citation2017; García & Wei, Citation2014; Lin & He, Citation2017; Nikula & Moore, Citation2016) continues to be popular when the class goes online due the COVID-19 pandemic (Chen et al., Citation2021). Following that, the participants of this study considered translanguaging for scaffolding the young learners’ CLIL mathematics learning because of the fact that grade one students who enrolled in the primary school during the pandemic should face forced learning remote learning with shorter time of second language learning opportunity. The use of Bahasa Indonesia in addition to teaching materials written in English functioned for bridging the students’ understanding about mathematical concepts (see Figure ) like “Let’s count.” which was followed by the explanation in Indonesian. However, translanguaging could not be practiced exclusively like what have been reported by Carbonara and Scibetta (Citation2020). Different pictures, colors, and shapes (see Figure ) were also used by the participants of this study to support the situation of accepting input in one language and producing input in another (Zein, Citation2019).

With respect to the teachers’ practice of translanguaging, trans-semiotizing involved semiotic resources in accordance to their language repertoires. Canagarajah (Citation2018) declared that communication can not only depend on words, but it should be mediated, shaped, and embedded in diverse other semiotic resources. The participants of this study had proved it. Figure shows how the teacher engaged all students in face-to-face and remote classrooms to pair number 5 by activating the students’ critical thinking skills. Instead of using Zoom’s interactive whiteboard, she chose to point her phone at a classroom whiteboard and instruct all students to follow how she moved her board marker to draw lines, circles, and numbers. Furthermore, as shown in Figure , the teacher was showing her fingers and counting numbers with remote students, while the co-teacher moved around the classroom to observe the students’ activity in counting numbers. Moreover, in order to address the inconsistency between sounds and symbols in English, the teacher explained the English numbers’ spellings multiple activities, saying the letter, pronounce it, and writing it simultaneously (see Figure ). She also asked one student in the classroom to write a number with its English word on a whiteboard to be corrected by his classmates. For other crucial cases like confusing English pronunciation for two different numbers, she explained the English pronunciation to all students by involving all students to follow her in writing each letter and say its sound. Liu (Citation2020) delineated that teacher and students practice translanguaging and trans-semiotizing in CLIL for students’ meaning-making by multilingual and multimodal resources.

The photovoice data in this current study display that the teachers apprehend translation, translanguaging, as well as trans-semiotizing as scaffolding to maintain the students–teachers–learning materials interactions within the hybrid learning during Indonesian PTMT through PPIs. Moreover, the teachers were more likely to choose translanguaging and trans-semiotizing due to the reason of the insufficient times of PTMT, which required the teacher’s creativity in managing two modes of delivery, simultaneously. In this present study, all teachers agreed to exploit learning materials in English to be presented with supplementary assistance of pictures of particular objects, body language, and facial expression to encode verbal language to texts and symbols in mathematics. They found this exploitation worked well with the students as attention grabbing and stimulus to practice PPIs as all students could get the opportunities to take part in teaching and learning process, attentively. This has been predicted by Yang and Yang (Citation2021) that interactive learning activities became one of the vulnerable forms of CLIL students’ satisfaction during the forced remote learning during the pandemic.

PPI that had been the teachers’ initiative model of interactions during hybrid learning was asserted that all teachers stereotypically favor teaching CLIL mathematics to be scaffolded by translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing based on existing situations. Canepari (Citation2020) disclosed that translation to be practiced in young learners' CLIL mathematics class elevates their academic and social performances. According to Liu (Citation2020) translanguaging and trans-semiotizing could be planned systematically to scaffold CLIL learning, Carbonara and Scibetta (Citation2020); Chen et al. (Citation2021) convinced that translanguaging/trans-semiotizing empowers the young learners’ language learning and makes young learners’ agency visible. In a more general sense, this current study’s results testify the teachers’ positive feedback to select the most suitable language scaffolding for their CLIL mathematics subject. Any of the three kinds of scaffolding could be selected by the teachers and put them into systematic lesson planning or all of them could be used in alternation. For hybrid learning, particularly, the teachers are required to be creative and innovative in teaching the students both language and content subject with greater access to technology to improve digital literacy.

6. Conclusion

To answer the question about the implementation of PPIs for CLIL mathematics hybrid learning during the Indonesian PTMT through translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing, the introduction of the urgency of polysynchronous interactions in an Indonesian internationally-tailored primary school was explained. English as a medium of instruction in mathematics or other subjects’ classrooms was reviewed. The most recent literature on English-medium classroom activities was adjusted with the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus was narrowed to the CLIL context in the primary level, which required intensive interactions, termed by the research setting as PPIs. As this adjustment demanded upon the teacher’s creativity in using the target language as well as the students’ L1, the teacher could select a translation, translanguaging, trans-semiotizing, or a combination of those three, to support students’ responsibility to do double tasks to learn a new language and study subject matter. In fact, translation was more time-consuming during PTMT compared to translanguaging/trans-semiotizing that could be practiced simultaneously. Therefore, from the teachers’ voices reflected from their photos of PPIs showed that collaboration between the mathematics teacher and homeroom teacher was urgent. They worked hand-in-hand to monitor students’ understanding of mathematics concepts and English. English literacy and numeracy were also scaffolded, from phonics to English language used to finish students’ tasks. Furthermore, both teachers’ agreement in alternating or combining translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing based on the existing situations had encouraged students to engage in the teaching and learning process.

Although this study was conducted at one school, we believe that it provides new insight into the teachers’ efforts to deal with challenges of hybrid teaching to young learners’ mathematics lessons using English and a feasible approach to provide equal attention to all students and qualified activities for all students their engagements. Simultaneous delivery modes in Indonesian internationally tailored schools differed from previous empirical studies because of the need to reinforce students’ literacy and numeracy skills in the L2. This program is critical for students’ language acquisition during their starting time to enroll in formal education to facilitate proficiency in their L1 before their L2. In turn, the teachers’ experience in practicing translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing should align with students’ agency as the class participants. In particular, Bahasa Indonesia should function to amplify the students’ learning. Regarding the study’s limitations, it is suggested that further researchers recruit more teachers to get more photovoices about their experience in providing exposure to English in learning the subject through translation, translanguaging, and trans-semiotizing.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Ria Pusvita Sari, M.Pd for sharing information about PPIs implemented at her school and granting permission to interview grade one homeroom and mathematics teachers. The insights they provided are highly beneficial for the researchers as well as readers to understand how to carry out PPIs in CLIL classrooms as part of the transition to the post-COVID-19 pandemic period.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fauzan

Fauzan is an Indonesian linguistics associate professor at the Indonesian Language and Education Department of Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang, and a member of Masyarakat Linguistik Indonesia (MLI) – an association for linguistics enthusiasts in Indonesia. His research interests focus on linguistics, pragmatics, second language learning, and education. (E-mail: [email protected], tel: +62 341 464318)

Rina Wahyu Setyaningrum

Rina Wahyu Setyaningrum is a faculty member of the English Language Education Department of Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang. Her research focuses on Teaching English to Young Learners (TEYL), Bilingual Education, and Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). (E-mail: [email protected], tel: +62 341 464318)

Suparto

Suparto is a teaching staff at the English Language Education Department of Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang. He was a professional staff for public communication and international collaboration to the Minister of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia from 2018 to 2019. His research interests are English language education, educational technology, and educational policy. (E-mail: [email protected], tel: +62 341 464 318)

References

- Agustín Llach, M. D. P. (2014). Exploring the lexical profile of young CLIL learners: Towards an improvement in lexical use. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 2(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.2.1.03agu

- Agustín Llach, M. P. (2017). The effects of the CLIL approach in young foreign language learners’ lexical profiles. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(5), 557–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1103208

- Ali, S. S. (2020). Educators teaching online and in person at the same time feel burned out. In NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/educators-teaching-online-person-same-time-feel-burned-out-n1243296

- Anderson, C. E., McDougald, J. S., & Medina, L. C. (2015). CLIL for young learners. In N. C. Giannikas, L. McMaughlin, G. Fanning, & N. D. Muller (Eds.), Children learning English: From research to practice (pp. 137–151). Garnet Education.

- Baynham, M., & Lee, T. K. (2019). Translation and translanguaging. Routledge.

- Call-Cummings, M., Hauber-Özer, M., Byers, C., & Mancuso, G. P. (2019). The power of/in Photovoice. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 42(4), 399–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2018.1492536

- Canagarajah, S. (2018). The unit and focus of analysis in lingua franca English interactions: In search of a method. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(7), 805–824. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1474850

- Canepari, M. (2020). The usefulness of different forms of translation in a CLIL environment. International Journal of English Linguistics, 10(2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v10n2p1

- Capous Desyllas, M., & Mountz, S. (2019). Using photovoice methodology to illuminate the experiences of LGBTQ former foster youth. Child & Youth Services, 40(3), 267–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2019.1583099

- Carbonara, V., & Scibetta, A. (2020). Integrating translanguaging pedagogy into Italian primary schools: Implications for language practices and children’s empowerment. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(3), 1049–1069. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1742648

- Chen, Y., Zhang, P., & Huang, L. (2021). Translanguaging/trans-semiotizing in teacher-learner interactions on social media: Making learner agency visible and achievable. System, 104(October 2021), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102686

- Choi, J. (2020). Multilingual learners learning about translanguaging through translanguaging. Applied Linguistics Review, 11(4), 625–648. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2018-0117

- Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge University Press.

- Coyle, Y., & Roca de Larios, J. (2020). Exploring young learners’ engagement with models as a written corrective technique in EFL and CLIL settings. System, 95, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102374

- Dalgarno, B. (2014). Polysynchronous learning: A model for student interaction and engagement. Proceedings of ASCILITE 2014 - Annual Conference of the Australian Society for Computers in Tertiary Education, 673–677. https://bit.ly/3YzvrE0

- Dalgarno, B., & Webster, L. (2015). A case study of polysynchronous learning on university bioscience education. Proceedings of the European Distance and E-Learning Network 2015 Annual Conference, 763–770. https://bit.ly/3WvJo3E

- Daniel, S. M., Jiménez, R. T., Pray, L., & Pacheco, M. B. (2019). Scaffolding to make translanguaging a classroom norm. TESOL Journal, 10(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.361

- Darvin, R., Lo, Y. Y., & Lin, A. M. Y. (2020). Examining CLIL through a critical lens. English Teaching & Learning, 44(2), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-020-00062-2

- Ellison, M. (2019). CLIL in the primary school context. In S. Garton & F. Copland (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Teaching English to Young Learners (pp. 247–268). Routledge.

- Espinosa, C. M., Herrera, L. Y., & Gaudreau, C. M. (2016). Reclaiming Bilingualism: Translanguaging in a Science Class. In O. Garcia & T. Kleyn (Eds.), Translanguaging with multilingual Students: Learning from Classroom Moments (pp. 160–177). Routhledge.

- Fernández-Fontecha, A., O’Halloran, K. L., Wignell, P., & Tan, S. (2020). Scaffolding CLIL in the science classroom via visual thinking: A systemic functional multimodal approach. Linguistics and Education, 55, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2019.100788

- Gallagher, F., & Colohan, G. (2017). T(w)o and fro: Using the L1 as a language teaching tool in the CLIL classroom. The Language Learning Journal, 45(4), 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2014.947382

- García, O. (2018). The multiplicities of multilingual interaction. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(7), 881–891. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1474851

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Garza, A. (2017). “Negativo por negativo me va dar un … POSITIvo”: Translanguaging as a vehicle for appropriation of mathematical meanings. In J. Langman & H. Hansen-Thomas (Eds.), Educational Linguistics (pp. 99–118). Springer.

- Kim, L. E., Leary, R., & Asbury, K. (2021). Teachers’ narratives during COVID-19 partial school reopenings: An exploratory study. Educational Research, 63(2), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2021.1918014

- Koltz, R. L., Odegard, M. A., Provost, K. B., Smith, T., & Kleist, D. (2010). Picture perfect: Using photo-voice to explore four doctoral students’ comprehensive examination experiences. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 5(4), 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2010.527797

- Latz, A. O., & Mulvihill, T. M. (2017). Photovoice research in education and beyond: A practical guide from theory to exhibition. Routledge.

- Lin, A. M. Y. (2019). Theories of trans/languaging and trans-semiotizing: Implications for content-based education classrooms. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1515175

- Lin, A. M. Y., & He, P. (2017). Translanguaging as dynamic activity flows in CLIL classrooms. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 16(4), 228–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2017.1328283

- Lin, A. M. Y., & Wu, Y. (2015). ‘May I speak Cantonese?’ – Co-constructing a scientific proof in an EFL junior secondary science classroom. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 18(3), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2014.988113

- Liu, Y. (2020). Translanguaging and trans-semiotizing as planned systematic scaffolding: Examining feeling-meaning in CLIL classrooms. English Teaching & Learning, 44(2), 149–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-020-00057-z

- Liu, Y., & Fang, F. (2020). Translanguaging theory and practice: How stakeholders perceive translanguaging as a practical theory of language. RELC Journal, 53(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220939222

- Lohmann, M. J., Randolph, K. M., & Oh, J. H. (2021). Classroom management strategies for hyflex instruction: Setting students up for success in the hybrid environment. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 807–814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01201-5

- Mayer, G., & Sekayi, D. (2018). Pedagogical practices of teaching assistants in polysynchronous classroom: The role of professional authonomy. InSight: AJournal of Scholarly Teaching, 13, 131–149.

- Metscher, S. E., Tramantano, J. S., & Wong, K. M. (2021). Digital instructional practices to promote pedagogical content knowledge during COVID-19. Journal of Education for Teaching, 47(1), 121–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1842135

- Michel, M., & O’Rourke, B. (2019). What drives alignment during text chat with a peer vs. a tutor? Insights from cued interviews and eye-tracking. System, 83, 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.02.009

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Sage.

- Mulder, C., & Dull, A. (2014). Facilitating self-reflection: The integration of photovoice in graduate social work education. Social Work Education, 33(8), 1017–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2014.937416

- Nikula, T., & Moore, P. (2016). Exploring translanguaging in CLIL. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(2), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1254151

- Oztok, M., Wilton, L., Lee, K., Zingaro, D., Mackinnon, K., Makos, S. & Hewitt, J. (2014). Polysynchronous: Dialogic construction of time in online learning. E-Learning and Digital Media, 11(2), 154–161. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2014.11.2.154

- Pierce, J. (2018). Storytelling through photos: A photovoice lens on ethical visual research. Research in Ethical Issues in Organizations, 19, 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1529-209620180000019005

- Rallis, S. F., & Rossman, G. B. (2009). Ethics and trustworthiness. In J. Heigham & R. A. Croker (Eds.), Qualitative Research in Applied Linguistics: A Practical Introduction (pp. 263–287). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ruiz-Alonso-Bartol, A., Querrien, D., Dykstra, S., Fernández-Mira, P., & Sánchez-Gutiérrez, C. (2021). Transitioning to emergency online teaching: The experience of Spanish language learners in a US university. System, 104, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102684

- Safira, A. R., & Ifadah, A. S. (2021). The readiness of limited face to face learning in the new normal era. JCES (Journal of Character Education Society), 4(3), 643–651. https://bit.ly/3YLmjMH

- Saldana, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

- Schüler-Meyer, A., Prediger, S., Kuzu, T., Wessel, L., & Redder, A. (2019). Is formal language proficiency in the home language required to profit from a bilingual teaching intervention in mathematics? A Mixed methods study on fostering multilingual students’ conceptual understanding. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 17(2), 317–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-017-9857-8

- Serra, C. (2007). Assessing CLIL at primary school: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), 582–602. https://doi.org/10.2167/beb461.0

- Simmonds, S., Roux, C., & Avest, I. T. (2015). Blurring the boundaries between photovoice and narrative inquiry: A narrative-photovoice methodology for gender-based research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(3), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691501400303

- Tai, K. W. H., & Wei, L. (2021). Co-Learning in Hong Kong English medium instruction mathematics secondary classrooms: A translanguaging perspective. Language and Education, 35(3), 241–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2020.1837860

- Tragant, E., Marsol, A., Serrano, R., & Llanes, À. (2016). Vocabulary learning at primary school: A comparison of EFL and CLIL. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 19(5), 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1035227

- Valdés-Sánchez, L., & Espinet, M. (2020). Coteaching in a science-CLIL classroom: Changes in discursive interaction as evidence of an English teacher’s science-CLIL professional identity development. International Journal of Science Education, 42(14), 2426–2452. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2019.1710873

- Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory Needs Assessment. Health Education and Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400309

- Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039

- Xie, K. (2020). Projecting learner engagement in remote contexts using emphatic design. Education Technology Research & Development, 69, 81–85.

- Yang, W. H., & Yang, L. Z. (2021). Evaluating learners’ satisfaction with a distance online clil lesson during the pandemic. English Teaching & Learning, 46(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-021-00091-5

- Zein, S. (2019). Translanguaging in the EYL Classroom as a Metadiscursive Practice. In S. Zein & R. Stroupe (Eds.), English Language Teacher Preparation in Asia: Policy, Research and Practice (pp. 47–62). Routledge.