Abstract

Using an integration of the Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction (ARCS) model and the Self-Determination Theory (SDT). This study explored university students’ motivation to learn through the use of gamification. A quantitative approach was used to obtain data from 60 students who participated in a gamified course utilizing a closed-ended questionnaire. The students were chosen using a random sampling method. Structural equation model (SEM) was used to assess the collected quantitative data. It was revealed through the study that the satisfaction attribute of motivation influences students’ engagement in learning whereas attention, relevance, confidence and relatedness do not. This research added to the existing discussion on the use of ARCS and SDT to explain why students are motivated to learn when gamification is used in universities.

1. Introduction

Engaging students in the learning process can be challenging, especially in the present time when many students are intensely involved with digital technologies outside of formal learning. Several studies have shown that the longer students are motivated to learn the more they become engaged in the learning process. Hence, more recently, there has been a surge of interest in exploring techniques that will motivate students to learn. One such technique is gamification.

Gamification is the use of game-related features or concepts in non-game contexts such as marketing or education (Manzano-León et al., Citation2021). It involves the use of game elements for making teaching and learning fun (Torres-Toukoumidis et al., Citation2021). According to Hanus and Fox (Citation2015), gamification has been successfully implemented in a wide range of sectors and its benefits are receiving much attention. With regards to education, it is believed that gamification has the potential of transforming the education sector (B. Huang et al., Citation2018; Hew et al., Citation2016; Manzano-León et al., Citation2021; Thurston, Citation2018). A number of researchers (McColgan et al., Citation2018; Turan et al., 2016; Mohamad et al., Citation2018) have shown that gamification can develop skills, reduce mental effort consumed in learning, and engage students to learn. Moreover, Dreimane (Citation2019) and Koivisto and Hamari (Citation2019) hold the view that gamification has a strong link with student motivation and involvement in learning. Hence, it is not surprising that Gamification in educational settings usually focus on a learner’s motivation or activity participation. Understanding motivation and its attributes that affect student behaviour towards learning is important.

Even though it is widely accepted that gamification is beneficial, it has been found that its implementation is rife with challenges. The need for a critical consideration of its application to avoid any pitfall in its implementation (Scheiner & Witt, Citation2013) is critical. For instance, Hamzah et al. (Citation2015) and Bovermann and Bastiaens (Citation2020) believe that there is a strong correlation between human psychology and gamification and that calls for having or acquiring skills that can effectively utilise gamification to motivate students to learn. However, Scheiner et al., (Citation2017) are of the view that “excessive” use of external rewards through gamification to motivate students to learn can impact negatively on their intrinsic motivation. The subjectivity of, “excessive” is of itself a mammoth challenge. Again, Scheiner et al. (Citation2017) believe that practitioners of gamification are likely to be inclined to use gamification to evoke fun mainly for entertainment instead of utilising gamification to induce fun whilst studying to enhance learning. In addition, it has been claimed that although there has been substantial amount of research on gamification in education, there has been relatively little research on motivation regarding gamification in education (Fazamin et al., Citation2015). The aforesaid challenges call for better understanding of motivation in education.

This study seeks to address the question—What role does gamification play in motivating students to engage in the learning process? It also seeks to discover the key factors that account for how gamification affects students’ motivation to study. By developing and experimentally testing a research model to explain the factors that affect students’ motivation to learn through gamification, the study adds to the body of knowledge.

The remaining part of the paper proceeds as follows: literature related to the study is presented, followed by the hypotheses development to address the question and the analysis and discussion of the results. Finally, implications for practice and concluding remarks are provided.

2. Literature review

2.1. Influence of gamification in general

Gamification is gaining influence in a wide range of sectors besides education such as business and health and has recently attracted a lot of attention from both business and academics (Behl et al., Citation2022). Many firms are using or attempting to use gamification in various areas of their businesses due to the potential benefits gamification offers. Human resource management, marketing and sales are a few of them (Karakas & Alperen, Citation2012; Yamabe & Nakajima, Citation2013). Gamification is used in these settings to train and inspire employees, encourage consumer engagement with companies, and even persuade individuals to change their behavior (Wünderlich et al., Citation2020). And these have mostly been made possible because of the fun that gamification evokes (Lu & Ho, Citation2020). According to Noorbehbahani et al. (Citation2019), Gamification also has a lot of promise for e-marketing, since one of the main goals of marketing is to increase client loyalty and engagement by persuading and inspiring individuals to be involved. The health sector has also experienced the benefit of gamification in some form or another. The present mortality risks are associated with illness including diabetes, hypertension and excessive cholesterol. These illnesses are brought on by a lifestyle that includes stress, eating a lot of sweets and fat, and not exercising (Sola et al., Citation2015). Changes in lifestyle are therefore required to prevent such diseases and advance a healthy living. Over the past two decades the use of ICT, typically gamification, has played a major role in managing health lifestyles (Kharrazi et al., Citation2012; Wattanasoontorn et al., Citation2013). Also, according to Rajani et al. (Citation2021), some studies have demonstrated that gamification has a positive effect on the cognitive elements of behavioural change, such as self-efficacy and motivation, which have proven to help reduce smoking.

2.2. Influence of gamification in education

Gamification is gaining popularity in education to boost student engagement, motivation, and performance (Hallifax et al., Citation2019; Saleem et al., Citation2022; Zahedi, Citation2019). Researchers in the field of computer science have studied several engagement techniques. The most important of these is gamification, or the application of game aspects (Zahedi, Citation2019).

Studies (e.g., Gee, Citation2003; Rosas et al., Citation2003) have shown that employing games in teaching has a number of significant advantages. Getting knowledge when needed, receiving feedback right away, regulating self-learning, and collaborating in teams are a few of these advantages. Gamification has also been thought to have the potential to significantly change education (Attali & Arieli-Attali, Citation2015; Nehring et al., Citation2018). Thurston (Citation2018) affirms that gamification increases student interest in their studies.

To better understand the impact of games on education, Zirawaga et al. (Citation2017) focused on learning theories such the cognitive information processing theory and the social activism theory in their study. They discovered that students are driven to complete a gamified course. Additionally, they learned that using games as teaching tools can help students feel more confident and can liven up otherwise dull and monotonous teaching methods.

The pedagogical use of gamification provides some solace to many students who are alienated by conventional methods of teaching and learning (Alsawaier, Citation2018). Additionally, using gamification to address the current loss in student motivation and engagement in the educational system may be a partial solution. Alsawaier (Citation2018) goes on to suggest that gamifying curriculum and course content for higher education could have a huge positive impact on university settings.

In order to increase student engagement in learning, using innovative teaching methods in higher education, especially in non-STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) programs, is encouraged (Gil-Doménech & Berbegal-Mirabent, Citation2019). The study by Gil-Doménech and Berbegal-Mirabent, in which students acknowledged a high level of interest and motivation to learn due to the competitive aspect of the gamified activities, indicates that gamification is one technique that can assist in this regard.

Even though gamification in education has been the topic of extensive research, its effectiveness is still not entirely obvious from the literature (Van Roy & Zaman, Citation2018). The best times, places, and strategies for implementing gamification aspects in the classroom are still up for debate among academic scholars and practitioners (R. Huang et al., Citation2020).

2.3. Influence of gamification on motivation

Motivation is regarded as a drive which influences an interest in one to behave in a particular way or do something. The drive can be influenced by an external factor (extrinsic motivation), such as doing an assignment because one will get a mark. The drive also can be fuelled from within (intrinsic motivation). For instance, doing an activity because the doing of that activity makes one happy. Gamification is initially used to develop extrinsic motivation which ultimately, is expected to influence intrinsic motivation. A very recent study by Saleem et al. (Citation2022) affirms the significant positive impact that gamification in education has on motivation. Their study findings demonstrate that gamification is becoming more widely recognized as a valuable tool for creating more engaging learning environments. Results from other studies have also shown that gamification can be regarded as a useful method to motivate users to utilize educational systems and raise their level of interaction and engagement (Bouchrika et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2022). Earlier, Ofosu-Ampong et al. (Citation2019), claimed that regardless of the method utilized, incorporating game components alone does not directly improve learning outcomes. Hence, they are of the view that, in order to determine how the game features can result in students’ meaningful involvement, it is necessary to link the gamified system to their interactions and behavioural intents such as motivation.

Motivation is sometimes referred to as a “prerequisite” for learning. As a result, many academics have been interested in it for a long time (Park, Citation2017). Motivation is a complex integration of cognitive, emotional, physical, cultural, previous experiences and environmental factors (Reynolds et al., Citation2017; Schunk et al., Citation2014). No wonder McMillan and Forsyth (Citation1991) has postulated that no single model or theory can be used in every situation and that each motivation theory is inadequate on its own and hence should be considered simultaneously with related theories in order to take appropriate action to increase students’ engagement in learning. Reynolds et al. (Citation2017) have opined that it is vital to note that motivation correlates with learning. However an attribute of motivation may not necessarily impact positively on learning, necessitating the need to identifying attributes of motivation that influence learning.

Two main motivation theories related to gamification which are noteworthy and hence considered in this study are Keller’s Attention, Relevance, Confidence and Satisfaction motivational model and Deci and Ryan’s Self Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). SDT is a popular paradigm for assessing students’ motivation and involvement in learning (Karra et al., Citation2019; Sailer & Homner, Citation2019) whereas J. M. Keller et al. (Citation2020) also claims that the ARCS model is one of the most reliable motivation models for measuring and promoting learning motivation; hence this study is underpinned by the integration of both theories to determine the impact of gamification on motivation. Although various studies have been done on the use of gamification to motivate students in learning, there is scarce studies on the impact of gamification on the determinants of motivation. Drawing on the relevance of the self-determination theory and the ARCS motivation model, this study seeks to bridge that gap. Specifically, the objective of this study is to explore the significant determinants that explain the impact of gamification on students’ motivation to learn.

2.4. Self-determination theory of motivation

The Self Determination Theory (SDT), which was introduced by Ryan and Deci (Citation2000) helps in understanding human motivation. Ryan and Deci (Citation2000) postulate that human beings are motivated by meeting three basic needs, specifically, autonomy, competence and relatedness. Autonomy signifies the control people have over actions they can take or the opportunity they can have to choose without being coerced. Competence implies having a sense of mastery of a task or being effective to carry out an activity. Relatedness means having a feeling of closeness and recognition by others. Ryan and Deci (Citation2000) posit that intrinsic motivation is more effective in increasing engagement and performance as compared to extrinsic motivation. The SDT, however, confirms that through the use of an external factor such as a reward to motivate, it is likely that one can develop a natural interest with the passage of time. In other words, extrinsic motivation can be used to develop intrinsic motivation. Likewise, the use of gamification based on external motivators such as points and badges can be used to introduce students to a course and eventually develop their intrinsic motivation to be engaged in the course. Gagné et al. (Citation2015) agrees that feelings of autonomy, competence and relatedness are associated with the intrinsic and extrinsic forms of motivation. Meeting those needs is essential for the engagement and development of human beings. In addition, Ryan and Deci (Citation2000) posit that motivation is contextual. Hence there is the need to understand the background and the environment of the people whose motivation are being targeted for effectiveness (Ruhi, Citation2015). Researchers (for example, Dichev & Dicheva, Citation2017) are of the view that Self-Determination Theory serves as the foundation for understanding the impact of motivation on gamification. Figure is a diagrammatic representation of the Self Determination Theory.

2.5. Keller’s ARCS motivational model

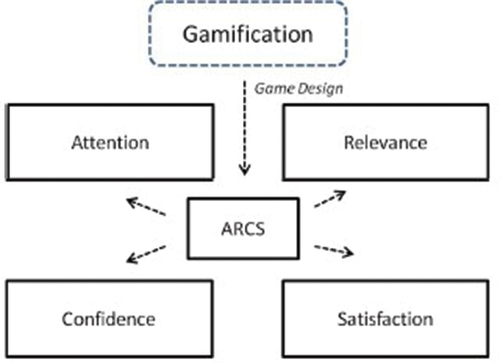

The Attention, Relevance, Confidence and Satisfaction (ARCS) motivational model designed by John Keller like SDT, offers important characteristics that altogether effectively address motivation. Lisa-Maria and Horst (Citation2015) are of the view that, the four attributes of Attention, Relevance, Confidence and Satisfaction are frequently considered as important antecedents of performance in learning. Attention denotes that students must find contents they interact with appealing to direct their focus. This is achieved through various ways including promoting participation, using visual demonstrations and encouraging role playing. Relevance implies that students must identify the present and future worth of a course for the course to appeal to them. Confidence signifies allowing students to go through activities having significant level of challenge or difficulty to maintain interest. Satisfaction, on the other hand, means students feeling content with their interaction in the course by the introduction of convincing and interesting elements such as rewards and immediate feedback within the course. According to Kapp (Citation2012), the application of the motivational model of Keller influences the identification of the needed requirements for implementing gamified systems. Moreover, ARCS highlights the essential attributes associated with human motivation and behavioral change (Gopalan et al., Citation2017). In addition, the ARCS model has scales which have been proven to be reliable for measuring the individual attributes since the model has been validated in a variety of applications and different cultures such as Europe, Asia, America (Orji et al., Citation2019). Hence the need to mainly consider this theory in this research. Figure shows how the factors interact diagrammatically.

Figure 2. Gamification and Keller’s Motivational Model (Schunk, Citation1996).

3. The adapted research model

The research model is composed of the four constructs of the ARCS model AT, RV, CO and SA and the RT construct of SDT. In the adopted research model, Autonomy and Competence of SDT are dropped since they are explained by Confidence in the ARCS model. Relatedness of SDT is added to ARCS to obtain the integrated model of ARCSR (Attention, Relevance, Confidence, Satisfaction and Relatedness). The studies of the influence of motivation in education is limited to either ARCS or SDT. For example, studies on motivation by Orji et al. (Citation2019), Ozdamli (Citation2018), and Hamzah et al. (Citation2015) are based on ARCS while Bovermann and Bastiaens (Citation2020), Wang et al. (Citation2019) and Wood’s (Citation2016) studies are linked to SDT. Therefore, an integrated model was developed to determine its validity in establishing the relationship between gamification and motivation of students. The proposed conceptual framework of the determinants of motivation in relation to gamification in learning is as shown in Figure .

4. Hypotheses development

4.1. The influence of gamification on attention (AT)

Attention is about generating and sustaining learners’ interests. Keller (Citation2010) posits that before any learning can be realised, the learner’s attention must be captured and that no matter how effective motivational tactics are, they lose their potency when learners’ attention are not sustained to keep them focused and engaged. Although literature studied does not specifically relate Attention to Gamification and motivation, various studies done indicate that motivation supports gamification (Fazamin et al., Citation2015; Orji et al., Citation2019; Ozdamli, Citation2018). Hence the hypothesis below was made:

H1.

Through gamification, attention (AT) significantly relates to motivation (MO).

4.2. The influence of gamification on relevance (RV)

Relevance with regards to learning denotes offering a learning experience which is useful and meaningful to the learner. It has been found through goal, expectancy-value and self-determination theories that students are motivated to engage in learning activities that help them to achieve their goals and hence the perceived value of an activity is an important antecedent of motivation (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000; Wigfield & Eccles, Citation2000). Also, van der Meij et al. (Citation2018) in their study using a tool to motivate students based on the ARCS model to appreciate the relevance of what is taught, reported a positive effect on students’ self-efficacy after using the motivating tool. Consequently, we hypothesised that:

H2.

Through gamification, relevance (RV) influences motivation (MO).

4.3. The influence of gamification on confidence (CO)

Confidence is about learners believing that they can succeed or exercise control over their learning processes. According to Orji et al. (Citation2019), the level of learners’ confidence are often correlated with their motivation towards the effort they make in achieving their learning objectives. The ARCS’ confidence can be likened to SDT’s autonomy and competence. Studies done related to SDT have highlighted that autonomy and competence are crucial components of motivation (Bandura, Citation1997; Wang et al., Citation2019; Wigfield & Eccles, Citation2000; Wood, Citation2016). Also, Fazamin et al. (Citation2015) in their study using the ARCS-G model found out that gamification significantly improves satisfaction and confidence of students. Moreover, it has been found out that a virtual tutoring system (VTS) used to motivate students to read based on the autonomy and competence attributes of the self-determination theory promoted students’ engagement in reading and learning (Park & Kim, Citation2016). Consequently, it is hypothesised that:

H3.

Through gamification, confidence (CO) relates positively to motivation (MO).

4.4. The influence of gamification on satisfaction (SA)

Satisfaction denotes fulfilment and agreement. Learners should be satisfied of what they achieved during the learning process. In other words, learners must gain some enjoyment from what they accomplish in order to motivate and retain their motivation (Orji et al., Citation2019). This implies there is relationship between motivation and satisfaction. Also, Ozdamli (Citation2018) in a study conducted to examine the effect of gamification applications adapted to an ARCS model, found out that students who were involved in a gamified course were highly motivated in confidence and satisfaction as compared to those involved in traditional course. Hence we hypothesize that:

H4.

Through gamification, satisfaction (SA) positively influences motivation (MO).

4.5. The influence of gamification on relatedness (RT)

Relatedness signifies having a feeling of being close and accepted by each other. It has been alleged that the need for relatedness is less understood, especially, in the classroom. Probably, this is one of the reasons interest in relatedness is gaining momentum in SDT-related research (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Wang et al. (Citation2019) on the other hand posit that relatedness contributes significantly to motivation. Therefore, we hypothesise that:

H5.

Through gamification, relatedness (RT) positively relates to motivation (MO).

5. Method

5.1. Approach

A quantitative approach was used to conduct this exploratory study. Since this study is part of a larger study, it focussed and reported on the quantitative aspect. The potential advantage of using quantitative approach is that there is less bias in the data, which allows the researcher to independently verify that the participants fit the necessary profile for the study, without divulging more identifying information.

5.2. The study context

One course was taught using blended learning approach. Thus the teaching of the course involved traditional instructor-led classroom activities and the use of technology in the classroom and outside the classroom. The technological components involved the use of MOODLE (Modular Object oriented Dynamic Learning Environment) and Kahoot. MOODLE was used to host course materials to allow students to interact with them. Also, MOODLE was used to administer quizzes which marked and placed scores on score boards (Leaderboard). Some of the quizzes allowed multiple trial of questions (Freedom to fail) with reduced marks as the number of trials increases to encourage students to try harder. Kahoot! was occasionally used in the classroom to test the students’ understanding of key concepts and also introduce competition in the classroom with a view of engaging the students to learn. In effect, the gamification elements considered were Points, Leaderboards and Freedom to fail.

5.3. Population and sample

A total of 60 Diploma students who enrolled in an Information Technology course at Pentecost University in Ghana, took part in this study. Since the researchers are from IT background, the researchers saw it necessary to gamify a course in Information Technology which they taught in-person using traditional methods.

5.4. Data collection instrument and measures

A questionnaire, modified from previous works for data collection for aspects of learning and motivation was used. The AT, RV, CO and SA constructs were taken from the 12-scale Reduced Instructional Materials Motivation Survey (RIMM) of J. M. Keller (Citation1987) while the RT construct was adapted from Need for Relatedness at College Questionnaire (NRC-Q) of Guiffrida et al. (Citation2008). The instrument consisted of 22 items (see Appendix). This number is made up of 20 items from the five constructs and two items from the demographic attributes. Each construct had 3 close-ended questions. A 5-point Likert scale was used with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and increasing to 5 representing “strongly agree”. Each respondent, on average, spent at least 20 minutes to fill the questionnaire. The online questionnaires were completed after the respondents had taken a semester course. To enhance the rate of response, students were regularly reminded to complete the online questionnaires. Overall, 56 questionnaires were received. Of the 56 respondents, 78.6% were males and 21.4 % were females, 21.4% were in the age range of 16 and 19, whereas 78.6% were more than 19 years; 28.6% have up to 2 years of game play experience, 50.0% % have up between 3 and 5 years of game play experience, whereas 21.4% have over 5 years of game play experience (see ).

Table 1. Shows the demographics

5.5. Ethical issues

Before administering the questionnaires to the participants, they were told that their involvement was optional, and their anonymity was guaranteed. Additionally, the respondents were informed of the purpose of the study before administering the online questionnaire to them.

5.6. Data analysis

In this study, PLS-SEM (partial least square structural equation modelling) with the aid of the SmartPLS 3 software was used to analyse the data. PLS-SEM is very good at exploring essential correlations that occur between constructs while SmartPLS 3 enables one to assess the validity (convergent and discriminant) of variables and their reliability directly in the SmartPLS 3 software without resorting to manually calculating them as done in other statistical software (Hair et al., Citation2014). Although IBM SPSS Amos (Analysis of Moment Structures) is also suitable for understanding relationships between variables, PLS-SEM was used because it has been noted that for a small sample size, PLS-SEM can work, but Amos might not provide a suitable model fit in such a circumstance (Dash & Paul, Citation2021). The data analysis was done in a two-way approach recommended by Schumacker and Lomax (Citation2010). These approaches are the measurement model and the structural model. The measurement model was done to determine the association between latent items and the observed items. Through the measurement model, convergent and discriminant validities were assessed. The structural model, on the other hand was constructed to identify the association between the dependent and independent variables. The structural model was tested using the bootstrap method with a parameter setting of 5,000 samples. The resultant model was employed to analyse the path coefficients of the suggested research model. In essence, the data analysis was done in a two-way approach to ensure the validity and reliability of the data as well as determining the association between the dependent and independent variables in the model.

6. Results

6.1. Descriptive statistics

shows the profile of the participants. Of the 56 respondents, the majority of the participants (78.6%) were males and 21.4 % were females. There were more participants in the age group above 19 years old, which is in keeping with their level of study., 21.4% were in the age range of 16 and 19, whereas 78.6% were more than 19 years; 28.6% have up to 2 years of game play experience, 50.0% % have up between 3 and 5 years of game play experience, whereas 21.4% have over 5 years of game play experience (see ).

Inferential statistics

Measurement model testing

Convergent validity (CV). In this study, CV was assessed by composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) as postulated by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). As shown in Table , the CR, shown in bold, is greater than the minimum value of 0.6 as recommended by Hair et al. (Citation2014). According to Hair et al. (Citation2014), composite reliability values within the range of 0.6 and 0.7 are considered reliable in exploratory research. Table shows that the Composite reliability values of all the constructs are greater than the recommended minimum of 0.6. Also, the AVE was greater than the minimum of 0.5 as recommended by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981).

Table 2. Convergent validity

Discriminant validity (DV). Fornell and Larcker’s (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981) principles were employed to measure the DV to determine that all the constructs are distinct from each other in order to obtain valid results. The square roots of the AVEs of a given construct were measured against the links between that construct and other constructs. It can be seen in Table that the square roots of the AVEs, (shown in the diagonal values) were greater than the other correlations (off diagonal values) and hence, the discriminant validity was considered to be reliable for all the constructs.

Table 3. Discriminant validity

6.2. Structural model testing

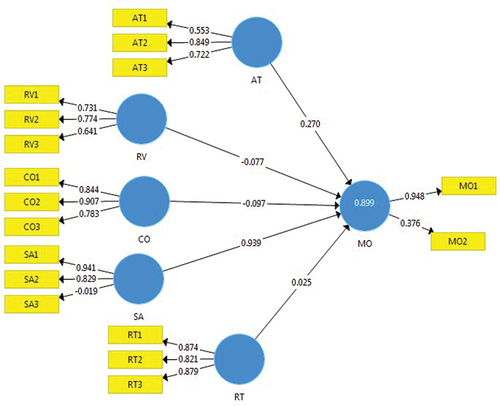

The model’s goodness-of-fit criteria are at an acceptable level. As shown in Figure , only one out of the five assumptions was confirmed by the data.

H1 evaluates whether attention (AT) significantly relates to motivation (MO). The results revealed that attention has no insignificant impact on motivation (b = 0.270, t = 0.941, p = 0.347). Hence, H1 was not supported.

H2 assesses whether relevance (RV) has a significant relationship with motivation (MO). The findings showed that motivation is not significantly impacted by relevance (b = −0.077, t = 0.865, p = 0.387). H2 was therefore not supported.

H3 evaluates the significance of the relationship between relevance (RV) and motivation (MO). The results demonstrated that relevance has no significant effect on motivation (b = −0.097, t = 1.080, p = 0.280). Therefore, H3 was not supported.

H4 evaluates whether satisfaction (SA) significantly relates to motivation (MO). The results revealed that satisfaction has a significant impact on motivation (b = 0.939, t = 3.947, p = 0.000). Hence, H4 was supported.

H5 determines whether relatedness (RT) and motivation (MO) have a meaningful relationship. According to the results, relatedness has no significant effect on motivation (b = 0.025, t = 0.381, p = 0.704). Consequently, H5 was not supported.

The results are presented in Table .

Table 4. Results of hypothesis testing

The results of the path analysis revealed that Satisfaction (SA) influenced motivation significantly (b = 0.939, p < 0.000), confirming H4. In others words, the respondents have indicated that they were satisfied with gamification, confirming the fourth hypothesis (H4) that satisfaction positively influences motivation. This result in effect addresses the research goal by indicating that gamification plays a significant role in motivating students to engage in learning. The result has also shown that satisfaction is a key attribute of motivation that accounts for how gamification impacts students’ learning. Figure , in addition, gives the predictive power of the model. It is noted that the model explained a remarkable 89.9% change in all the dependent variables of AT, RV, CO, SA and RT.

Attention (AT), however, did not significantly influence motivation (b = 0.270, p < 0.347). Also, Relevance (RV) (b = −0.077, p < 0.387); Confidence (CO) (b = −0.097, p < 0.280) and Relatedness (RT) (b = 0.025, p < 0.704) did not significantly influence motivation to learn through gamification. Consequently, H1, H2, H3 and H5 were not confirmed. Figure , in addition, gives the predictive power of the model. It is noted that the model explained a remarkable 89.9% change in all the dependent variables of AT, RV, CO, SA and RT.

To summarize, the model utilized in this study revealed a significant level of variation in the dependent variables. These variables have a good predictive power, confirming the model’s consistency and robustness. Table shows the results of the research model’s structural path analysis.

7. Discussion

This study aimed to:

explore the role gamification plays in motivating students to learn

discover the significant determinants that explain the impact of gamification on students’ motivation to learn.

Data received from 56 students were used to test the model. Five constructs from ARCS model and SDT theory were utilised to create the model.

The research model explained 89.9% of the change in Motivation (MO). This finding proposes that the research model significantly predicted the use of gamification in motivating students to learn. However, according to the structural equation modelling, only the Satisfaction (SA) attribute of motivation was influenced by gamification agreeing with previous research such as Keller (Citation2010).

The hypothesis testing results indicate that Attention (AT), Relevance (RV), Confidence (CO) and Relatedness (RT) do not motivate students to learn using gamification. This discovery is in contrast with propositions that, considering an activity to be relevant motivates one to carry out that activity (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000; van der Meij et al., Citation2018; Wigfield & Eccles, Citation2000). This finding also on one hand disagrees with the findings of Ozdamli (Citation2018) that students involved in gamified courses were highly motivated in Confidence (CO) and on the other hand agrees that they were highly motivated in Satisfaction (SA). However, it should be noted that the data shows strong evidence that Attention, Relevance, Confidence and Relatedness do motivate students to learn using gamification. It is not surprising that studies such as Greenland et al. (Citation2016) and Weinberg (Citation2001) highlighting the limitations and misinterpretations of p-values, caution that no matter how big a p-value is, it cannot be used to draw a firm conclusion that “no relationship” exists. It has been noted among other circumstances that a smaller sample size can give a large p-value. Hence the disparity noted between the data and the hypothesis testing could be the use of a small sample size in this study. This calls for further studies using large sample sizes and in different contexts such as different institutions, level of study (Diploma, Undergraduate and Postgraduate), mode of study, gender and culture, among others, to further support or reject the claim for using gamification to enhance motivation to learn.

8. Limitations of the current study

The findings in this study are subject to at least three limitations.

First, the data for this study was collected using a cross-sectional strategy. It is advised that future research employ longitudinal studies to collect data from participants in order to better understand how the integration of ARCS and SDT attributes of motivation influence students to learn when gamification is applied and how that influence varies over time.

Second, although a significant value of about 90 percent of the variance was explained by motivation (MO) when gamification is employed, future studies should explore other elements that may account for remaining unaccounted 10% in order to better understand how students are motivated to learn when gamification is applied.

Third, only a quantitative method was employed to carry out this study. Future studies should use mixed-method to obtain a richer understanding of the impact of gamification on students’ motivation to engage in learning.

9. Conclusion and implication for practice

Notwithstanding the limitations indicated, the study contributes to the body of knowledge by constructing and experimentally verifying a research model to explain the determinants that impact student’s motivation to learn with gamification.

Approximately 90% of the variance in motivation was reported by the research model. This suggests that future research should look into additional factors including age, gender and game experience to learn more about attributes of motivation that contributes to learning through gamification.

Knowing the attributes that motivate students to learn can ultimately influence the choice and application of suitable technology to increase students’ engagement in learning. The finding of this study could be of value to scholars, educators, lecturers, policymakers and other stakeholders, given the era of online teaching and the hybrid teaching modes that are prevalent post the COVID-19 era.

Finally, the proposed research model has been shown to be effective in exploring attributes of motivation which are influenced by gamification. The findings of this study also have practical implications including:

The institution providing a conducive environment for the adoption of gamification.

The institution’s management increasing lecturer’s awareness of gamification by providing training on what can be done with the technology and what advantages can be obtained.

The university’s administrators encouraging lecturers to learn about gamification with the aim of obtaining the necessary skills and knowledge to apply it in teaching.

Lecturers assessing the motivating needs of students prior to the application of gamification.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alsawaier, R. S. (2018). The effect of gamification on motivation and engagement. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 35(1), 56–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-02-2017-0009

- Attali, Y., & Arieli-Attali, M. (2015). Gamification in assessment: Do points affect test performance? Computers and Education, 83, 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.12.012

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

- Behl, A., Jayawardena, N., Pereira, V., Islam, N., Del Giudice, M., & Choudrie, J. (2022). Gamification and e-learning for young learners: A systematic literature review, bibliometric analysis, and future research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 176, 121445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121445

- Bouchrika, I., Harrati, N., Wanick, V., & Wills, G. (2021). Exploring the impact of gamification on student engagement and involvement with e-learning systems. Interactive Learning Environments, 29(8), 1244–1257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1623267

- Bovermann, K., & Bastiaens, T. (2020). Towards a motivational design? Connecting gamification user types and online learning activities. RPTEL, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-019-0121-4

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121092

- Dichev, C., & Dicheva, D. (2017a). Gamifying education: What is known, what is believed and what remains uncertain: A critical review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0042-50

- Dreimane, S. (2019). Gamification for education: Review of current publications. In L. Daniela (Ed.), Didactics of smart pedagogy (pp. 453–464). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01551-0_23

- Fazamin, A., Ali, H., Mohd Saman, Noraida, M. H., Saman, Y., Yusoff, M., & Yacob, A. (2015). Influence of gamification on students’ Motivation in using E-Learning applications based on the motivational design model. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (Ijet), 10(2), 30. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v10i2.4355

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gagné, M., Forest, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Crevier-Braud, L., van den Broeck, A., Kristin Aspeli, A., Bellerose, J., Benabou, C., Chemolli, E., Tomas Güntert, S., Halvari, H., Laksmi Indiyastuti, D., Johnson, P. A., Hauan Molstad, M., Naudin, M., Ndao, A., Hagen Olafsen, A., Roussel, P., Wang, Z., & Westbye, C. (2015). The multidimensional work motivation scale: Validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(2), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2013.877892

- Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy Computers in Entertainment. Computers in entertainment, 1(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1145/950566.950595.

- Gil-Doménech, D., & Berbegal-Mirabent, J. (2019). Stimulating students’ engagement in mathematics courses in non-STEM academic programmes: A game-based learning. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 56(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2017.1330159

- Gopalan, V., Aida, J., Bakar, A., Nasir Zulkifli, A., Alwi, A., & Che Mat, R. (2017). A Review of the Motivation Theories in Learning. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 10150053661(10), 20043–20044. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.424452

- Greenland, S., Senn, S. J., Rothman, K. J., Carlin, J. B., Poole, C., Goodman, S. N., & Altman, D. G. (2016). Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: A guide to misinterpretations. European Journal of Epidemiology, 31(4), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0149-3

- Guiffrida, D., Gouveia, A., Wall, A., & Seward, D. (2008). Development and validation of the need for relatedness at college questionnaire (NRC-Q). Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 1(4), 251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014051

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications.

- Hallifax, S., Serna, A., Marty, J. C., & Lavoué, É. (2019, September). Adaptive gamification in education: A literature review of current trends and developments. In European conference on technology enhanced learning (pp. 294–307). Springer, Cham.

- Hamzah, W. M. A. F. W., Ali, N. H., Saman, M. Y. M., Yusoff, M. H., & Yacob, A. (2015). Influence of gamification on students’ motivation in using e-learning applications based on the motivational design model. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (Ijet), 10(2), 30–34. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v10i2.43505

- Hanus, M. D., & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & Education, 80, 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.08.019

- Hew, K. F., Huang, B., Chu, K. W. S., & Chiu, D. K. W. (2016). Engaging Asian students through game mechanics: Findings from two experiment studies. Computers & Education, 92-93, 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.010

- Huang, B., Hew, K. F., & Lo, C. K. (2018). Investigating the effects of gamification-enhanced flipped learning on undergraduate students’ behavioral and cognitive engagement. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(8), 1106–1126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1495653

- Huang, R., Ritzhaupt, A. D., Sommer, M., Zhu, J., Stephen, A., Valle, N., Li, J., & Li, J. (2020). The impact of gamification in educational settings on student learning outcomes: A meta-analysis. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(4), 1875–1901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09807-z

- Kapp, K. M. (2012). The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education. Pfeiffer.

- Karakas, F., & Alperen, M. (2012). Reorienting self-directed learning for the creative digital era. European Journal of Training and Development, 36(7), 712–731. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591211255557

- Karra, S., Karampa, V., & Paraskeva, F. (2019). Gamification design framework based on self-determination theory for adult motivation. In L. Uden, D. Liberona, G. Sanchez, & S. Rodríguez-González (Eds.), Learning Technology for Education Challenges. LTEC 2019. Communications in Computer and Information Science (Vol. 1011, pp. 67–78). Springer.

- Keller, J. M. (1987). Development and use of the arcs model of motivational design. Journal of Instructional Development, 10(3), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02905780

- Keller, J. M., Ucar, H., & Kumtepe, A. T. (2020). Development and validation of a scale to measure volition for learning. Open Praxis, 12(2), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.12.2.10820

- Kharrazi, H., Lu, A. S., Gharghabi, F., & Coleman, W. (2012). A scoping review of health game research: Past, present, and future. Games for Health Journal, 1(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2012.0011

- Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.10.013

- Lisa-Maria, P., & Horst, T. (2015). Creating a theory-based research agenda for gamification. Twentieth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Savannah.

- Li, X., Xia, Q., Chu, S. K. W., & Yang, Y. (2022). Using gamification to facilitate students’ self-regulation in E-Learning: A case study on students’ L2 English Learning. Sustainability, 14(12), 7008. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127008

- Lu, H. P., & Ho, H. C. (2020). Exploring the impact of gamification on users’ engagement for sustainable development: A case study in brand applications. Sustainability, 12(10), 4169. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104169

- Manzano-León, A., Camacho Lazarraga, P., Guerrero, M. A., Guerrero-Puerta, L., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Trigueros, R., & Alias, A. (2021). Between level up and game over: A systematic literature review of gamification in education. Sustainability, 13(4), 2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042247

- McColgan, M., Colesante, R., Andrade, A., & Roeske, K. P. (2018). Working with the Wesley college cannon scholar program: improving retention, persistence, and success. Journal of STEM Education, 19(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-017-0062-7

- McMillan, J. H., & Forsyth, D. R. (1991). What theories of motivation say about why learners learn. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 1991(45), 39–52. available at. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.37219914507.

- Mohamad, S. N. M., Sazali, N. S. S., & Salleh, M. A. M. (2018). Gamification approach in education to increase learning engagement. International Journal of Humanit Arts Social Sciences, 4(1), 22–32.

- Nehring, N., Baghaei, N., & Dacey, S. (2018). Improving students’ performance through gamification: A user study. CSEDU, 213–218.

- Noorbehbahani, F., Salehi, F., & Zadeh, R. J. (2019). A systematic mapping study on gamification applied to e-marketing. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 13(3), 392–410. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-08-2018-0103

- Ofosu-Ampong, K., Boateng, R., Anning-Dorson, T., & Kolog, E. A. (2019). Are we ready for Gamification? An exploratory analysis in a developing country. Education and Information Technologies, 25(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-10057-7

- Orji, R., Reilly, D., Oyibo, K., & Orji, F. A. (2019). Deconstructing persuasiveness of strategies in behaviour change systems using the ARCS model of motivation. Behaviour & Information Technology, 38(4), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1520302

- Ozdamli, F. (2018). ARCS motivation model adapted to gamification applications on a programming language course. International Journal of Learning Technology, 13(4), 327–351. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLT.2018.098502

- Park, S. W. (2017). Motivation theories and instructional design. Pressbooks.

- Park, S. W., & Kim, C. (2016). The effects of a virtual tutee system on academic reading engagement in a college classroom. Educational Technology Research and Development, 64(2), 195–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-015-9416-3

- Rajani, N. B., Mastellos, N., & Filippidis, F. T. (2021). Impact of gamification on the self-efficacy and motivation to quit of smokers: Observational study of two gamified smoking cessation mobile apps. JMIR Serious Games, 9(2), e27290. https://doi.org/10.2196/27290

- Reynolds, K. M., Roberts, L. M., & Hauck, J. (2017). Exploring motivation: Integrating the ARCS model with instruction. Reference Services Review, 45 (2), 149–165. Reference Services Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-10-2016-0057

- Rosas, R., Nussbaum, M., Cumsille, P., Marianov, V., Correa, M., Flores, P., Grau, V., Lagos, F., López, X., López, V., Rodriguez, P., & Salinas, M. (2003). Beyond Nintendo: Design and assessment of educational video games for first and second grade students. Computers, 40(1), 71–94.andEducation. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-1315(02)00099-4

- Ruhi, U. (2015). Level up your strategy: Towards a descriptive framework for meaningful enterprise gamification. Technology Innovation Management Review, 5(8), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/918

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Deci Self-deteremination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness The. Guilford Press.

- Sailer, M., & Homner, L. (2019). The gamification of learning: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09498-w

- Saleem, A. N., Noori, N. M., & Ozdamli, F. (2022). Gamification applications in E-learning: A literature review. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 27(1), 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-020-09487-x

- Scheiner, C. W., & Witt, M. (2013). The backbone of gamification: A theoretical consideration of play and game mechanics. In M. Horbach (Ed.), Informatik 2013 (pp. 2372–2386). Ges. für Informatik.

- Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2010). A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, outledge. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Schunk, D. H. (1996). Learning Theories. Prentice Hall Inc.

- Schunk, D. H., Meece, J. L., & Pintrich, P. R. (2014). Motivation in Education: Theory, Research, and Applications (4th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Sola, D., Couturier, J., & Voyer, B. (2015). Unlocking patient activation in chronic disease care. British Journal of Healthcare Management, 21(5), 220–225. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2015.21.5.220

- Thurston, T. N. (2018). Design Case: Implementing gamification with ARCS to engage digital natives. Journal on Empowering Teaching Excellence, 2(1). Article 5. DOI. https://doi.org/10.26077/vsk5-5613.

- Torres-Toukoumidis, A., Carrera, P., Balcazar, I., & Balcazar, G. (2021). Descriptive study of motivation in gamification experiences from higher education: Systematic review of scientific literature. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 9(4), 727–733. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2021.090403

- van der Meij, H., van der Meij, J., Voerman, T., & Duipmans, E. (2018). Supporting motivation, task performance and retention in video tutorials for software training. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(3), 597–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-017-9560-z

- Van Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2018). Need-supporting gamification in education: An assessment of motivational effects over time. Computers & Education, 127, 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.018

- Wang, C. J., Liu, W. C., Kee, Y. H., & Chian, L. K. (2019). Competence, autonomy, and relatedness in the classroom: Understanding students’ motivational processes using the self-determination theory. Heliyon, 5(7), e01983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01983

- Wattanasoontorn, V., Boada, I., García, R., & Sbert, M. (2013). Serious games for health. Entertainment Computing, 4(4), 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2013.09.002

- Weinberg, C. R. (2001). It’s time to rehabilitate the P-value. Epidemiology, 12(3), 288–290. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-200105000-00004

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value Theory of Achievement Motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015

- Wood, D. R. (2016). The impact of students’ perceived relatedness and competence upon their motivated engagement with learning activities: a self-determination theory perspective (Doctoral dissertation, University of Birmingham).

- Wünderlich, N. V., Gustafsson, A., Hamari, J., Parvinen, P., & Haff, A. (2020). The great game of business: Advancing knowledge on gamification in business contexts. Journal of Business Research, 106, 273–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.062

- Yamabe, T., & Nakajima, T. (2013). Playful training with augmented reality games: Case studies towards reality-oriented system design. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 62(1), 259–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-011-0979-7

- Zahedi, L. R. (2019, June). Implications of gamification in learning environments on computer sci-ence students: A comprehensive study. Proceedings of the 126th Annual Conference and Exposition of American Society for Engineering Education, Tampa, Florida, USA.

- Zirawaga, V. S., Olusanya, A. I., & Maduku, T. (2017). Gaming in education: Using games as a support tool to teach history. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(15), 55–64.

Appendix

This questionnaire is part of a study to explore the relationships between gamification and motivation of student. Kindly tick (√) the appropriate option to indicate your response.

Demography

Demography undefined