Abstract

Self-regulated learning (SRL) has been promoted as playing a key role in proactive, life-long learning. The present study aimed to investigate the effect of different types of teacher feedback on students’ self-regulated learning (SRL) in a special educational needs (SEN) context. It employed a mixed method, quasi-experimental with repeated-measures pre-test-treatment-post-test design. Forty-five students from a SEN school were explicitly taught SRL strategies over nine sessions. Participants were divided into two matched groups and provided different types of feedback (DF group) or corrective feedback only (CF group). Data was collected from individual interviews and student artefacts. Consistent with research on the benefits of explicit SRL instruction in mainstream school contexts, this study in the SEN context found statistically significantly higher student SRL scores at post-test than pre-test. Comparing scores between the feedback groups turned out not statistically significant. However, insightful qualitative differences were found in analyses of assignments and interview data at all three phases of SRL. Findings coalesced around the themes of Skill and Will, providing insights to students’ motivation and affect, influencing student volition. These findings suggest both changes at the practice and policy level in SEN contexts to bring about feedback-rich learning environments to facilitate SRL.

Public Interest Statement

Learners with special educational needs (SEN) like mild intellectual disabilities or autism have difficulties in reading, staying on-task, monitoring their progress towards learning goals and forming accurate judgements on their learning expectations, task difficulty and appraisals on their learning. This study explores how to teach students with SEN to become proactive towards their learning, through explicit instruction and feedback supports provided throughout learning tasks. We found that to facilitate motivation and volition, students need to be equipped with not only academic skills but also provided with feedback guidance to apply strategies, for example, to manage their emotions towards tasks that they view as challenging and learn how and when to engage in help-seeking for their learning.

1. Introduction

There are different aspects to self-regulated learning (SRL). One aspect is metacognition involving observable skills such as planning, monitoring and evaluation, which is consciously controlled and assessable. Other aspects can be tacit to include self-generated thoughts, feelings and behaviours towards “learning that is self-directed, intrinsically motivated, and under the deliberate, strategic control of the learner” (Baker & Cerro, Citation2000, p. 101). One definition that seeks to encompass these various aspects of SRL is the one adopted for this study: self-regulated learners are students who are “metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviourally proactive regulators of their own learning” (Zimmerman, Citation1990, p. 4).

It is commonly accepted that SRL is essential and crucial for lifelong learning and progress in academic tasks, such as reading comprehension (Zimmerman, Citation2008). However, it is not clear if this applies to the SEN context where students are often thought to have reactive instead of proactive SRL behaviours (Buzza & Dol, Citation2015) and learning these skills may be considered challenging.

Considerable research in SRL has found that explicit instruction in SRL is beneficial in mainstream settings (Schunk & Zimmerman, Citation2007; Schünemann et al., Citation2013). Though there are studies in the special needs context (SEN) (Buzza & Dol, Citation2015; Kang, Citation2010), these are limited to the study of isolated strategies such as goal setting (Kang, Citation2010) or self-control (Buric & Soric, Citation2012; Nelson & Manset-Williamson, Citation2006). There is a need to explore SRL in the SEN context in a more comprehensive manner, looking at how SEN students self-regulated at each phase of Zimmerman’s SRL model (Zimmerman, Citation2002) for example, how they set goals, use strategies and reflect after feedback.

As an experienced special educator, I have observed that in schools elsewhere, teachers tend to provide praise and corrective feedback in their classrooms (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007). However, because student response and reactions to them may differ, there is a need to explore different types of teacher feedback that students with SEN need as social guidance and additional support (Tay & Kee, Citation2019) and that they may need in applying SRL strategies (Schünemann et al., Citation2013).

In short, how can teachers help students with learning disabilities or challenges in learning, even those who are considered low-achieving, to engage in learning SRL? In particular, this study aims to explore the impact of explicit instruction in SRL and feedback as instruction and additional social support for students with SEN. The findings will contribute to an understanding of how students can be encouraged to become agents in their own learning and actively choose to engage in proactive learning behaviours.

1.1. The importance of SRL in students with SEN

One main concern for students with SEN is that students with difficulties in reading tend to fall further and further behind peers throughout school. It could be that these difficulties in reading comprehension stem from a lack of SRL skills, such as matching task expectations and difficulty (Holtzheuser & McNamara, Citation2014). As such, it is important that SRL be taught explicitly to students with SEN.

Unfortunately, special educators tend to focus on teaching low-level, deficit skills instead of modelling the full spectrum of SRL skills (Kang, Citation2010). They report that they face great challenges in classroom management (Lindsay et al., Citation2013; Scott, Citation2017). Hence, they may prioritize reducing disruptive behaviours in the classroom for students and focus on teaching low-level, deficit skills instead of modelling the full spectrum of SRL skills (Anderson, Citation2015). As such, they fail to teach proactive SRL behaviours such as students analysing their tasks, setting effective goals, activating, altering and sustaining specific learning practices (Zimmerman, Citation2008).

Failing to learn proactive SRL behaviours may lead to dire consequences, such as falling behind in academic progress, failing in school or being unable to accomplish desired life outcomes (Buzza & Dol, Citation2015). According to the study, when faced with undesired outcomes, learners may exhibit reactive SRL behaviour, which involves modifying their learning behaviours based on feedback from external sources or prompts from teachers, feedback or teacher’s prompts. It is then too late to inform and modify behaviours.

Explicit instruction in SRL is thus important for all students, including those with SEN. According to Schünemann et al. (Citation2013), it involves providing clear and explicit verbal instructions and cognitive modelling to demonstrate how skills are applied successfully. It can also involve a sequence of patterned steps from observation to instruction, emulation and self-control.

Social guidance and feedback learners receive would play a key role in students emulating the expert model in order to regulate their behaviour (Schunk & Zimmerman, Citation2007; Schünemann et al., Citation2013). Learners must internalise their behaviours and gain flexibility to apply them in new contexts or different tasks to achieve full self-regulation.

Another aspect that would need explicit instruction is with respect to students’ volition, which consists of “strength of will to complete a task and the diligence of pursuit” (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2002, p. 126). Volitional strategies, such as help-seeking, are also crucial for learners to achieve mastery in learning. Teacher feedback towards student use of volitional strategies such as help-seeking may be needed for students to strive towards mastery in learning. However, there are differences in how learners seek help (Chou et al., Citation2018). Executive help-seekers may overuse help that is available merely to get the correct answer, while instrumental help-seekers only seek help that they need for their learning.

One more aspect that can promote student volition is reflective thinking and self-monitoring of emotions (Grothérus et al., Citation2019). Students with SEN, especially low-achieving students, may face obstacles and challenges in their learning tasks; such emotion regulation strategies can help reduce stress and deal with negative emotions, helping them feel efficacious towards their studies (Buric & Soric, Citation2012).

Past studies generally often focus narrowly on specific skills such as goal setting (Kang, Citation2010) or one aspect of SRL such as self-efficacy (Schunk & Rice, Citation1993; Van Loon & Roebers, Citation2020). Those on emotional or volitional strategies are few. There is a need for a study to “paint a full portrait of SRL” (Vandevelde et al., Citation2011, p. 423) in all three SRL aspects of metacognition, motivation, and behaviour, and the kind of support that is necessary for students with SEN to learn SRL. Of particular focus in this study is the support provided by teachers’ feedback.

1.2. Types of feedback

In the social cognitive perspective, feedback can be an instructional tool. It can provide social guidance for students when they learn new skills such as SRL strategies. Such feedback in the learning environment provides scaffolds for students to analyse their learning processes and engage in higher-order thinking (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007). Social guidance is effective in building self-regulatory skills and helps promote skills such as reading and writing (Schunk & Zimmerman, Citation2007). It helps students to adapt new skills learnt to new contexts and to self-regulate their own behaviours. As such, teachers play a powerful role in the classroom, intentionally guiding students through the type of feedback they provide.

Hattie and Timperley’s (Citation2007) model specifies four different types of feedback that operate at four levels of depth, known as “feedback specificity.” The four levels are Task level (FT), Process level (FP), Self-regulation (FSR) and Self level (FS).

1.2.1. Typical feedback for students with SEN

Of these levels of feedback, Self level (FS) is not recommended to be provided on its own (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007). Students may enjoy receiving an FS like “Well done!” or “You are smart!” which serve as positive affirmations and praise (Silver & Lee, Citation2007). However, it can also serve to distract student attention from task processes and self-regulation, depending on the way students perceive it. As such, although students might prefer praise (FS), this information may not be useful towards their learning (Silver & Lee, Citation2007).

Task level (FT) provides information on how well a task is performed, confirming students’ correct response or result. Corrective feedback (CF) is one type of FT provided when the teacher highlights errors, with a symbol (such as a cross) or underscore and may include an indication of how the error is to be corrected (Tay & Lam, Citation2022). CF provides information on how well a task is performed and confirming students’ correct response or result. As pointed out before, SEN students are most commonly provided this type of corrective feedback in classrooms and, therefore, CF is used as control condition in this study.

1.2.2. Differentiated feedback

In this study, the term “Differentiated feedback” (DF) means different types of feedback, namely, Process level (FP), Self-regulation (FSR) that is targeted to facilitate aspects of SRL at the three phases of Zimmerman’s (Citation2002) SRL model. In this study, DF, comprising FP and FSR, is used as experimental condition presented as instruction or social supports for learning. Through synthesizing previous studies on feedback in the SEN context, the following section describes DF that is appropriate for each of Zimmerman’s three SRL phases: Forethought, Performance and Self-Reflection.

In the Forethought phase, feedback should contain information about learning goals, specific skills and targets. Feedback on process (FP) is the elaborated or process-level feedback commonly used when students engage in tasks at the Performance phase, but it has also found positive effects on goal setting at the Forethought phase (Alitto et al., Citation2016; West et al., Citation2001). Kang (Citation2010) specifically found that feedback information (FP) about learning goals, specific skills and targets helps students with SEN form evaluations about their task and informs on their progress towards their goals.

At the Performance phase, when students engage in their learning tasks, FP can be provided to help students in their strategy use, to invest effort and seek further feedback information. In past studies involving feedback, a significant impact of different types of Process-level feedback (FP) has been found in strategy use and motivation in students with SEN. When students with reading disabilities were given explicit strategy-value feedback in their reading comprehension task, they benefited in forming more positive, adaptive attributions for incorrect strategy use in their self-judgements and in turn, their sense of self-efficacy those in the guided reading group (Nelson & Manset-Williamson, Citation2006). When students engage in their learning tasks, FP can be provided to help students in their strategy use, to invest effort and seek further feedback information.

In Butler, Beckingham & Lauscher’s (Citation2005) case study of students with learning disabilities, students were explicitly taught procedural knowledge and strategy use and to articulate and self-monitor the use of strategy in Mathematical problem-solving. Students benefitted in constructing and reflecting on knowledge on strategy use, self-assessment, and strategy revision. Their motivation and positive affect were seen in their enthusiastic approach to such challenging tasks.

At the Self-reflection phase, FSR is feedback that focuses on self-reflection and evaluation. FSR can provide information about performance outcomes, self-judgements of student learning to facilitate accurate self-evaluation. Overall, in past studies, there seems to be a lack of provision of FSR (Gan & Hattie, Citation2014). FSR was provided in strategic questioning like “What are we trying to do here?” (Butler et al., Citation2005), requiring some rephrasing, affirmation and completion of tentative answers. For students with SEN, expressing detailed or elaborate answers to such open-ended questions may pose as a challenge or threat (Nind, Citation2008). As such, FSR may be best presented as statements in the SEN context.

1.2.3. The gap: providing feedback for students with SEN to develop SRL

As can be seen, the studies mentioned in the previous section tend to focus on isolated aspects of SRL, such as goal-setting. A search on Google Scholar revealed that there have been no studies using Zimmerman’s model to target different types of feedback at each phase, Forethought, Performance and Self-reflection. In addition, although there are studies on explicit instruction for SRL, there is a lack of study on feedback strategies in the teaching of SRL (Buric & Soric, Citation2012; Chou et al., Citation2018).

Without SRL, low-achieving students may depend on teacher feedback but do not know how to use it (Çakır et al., Citation2016). It is important to overcome such barriers of poor feedback literacy in low-achieving students like those with SEN (Carless & Boud, Citation2018). As such, we need to study the relation between feedback and SRL (Çakır et al., Citation2016).

As such, the present study explores the benefit of feedback as instruction in the special needs context for facilitating agency in students towards their learning. The research question was “What is the impact of differentiated feedback (i.e. feedback at forethought, performance, and self-reflection) compared with corrective feedback on SRL of students with SEN?” If there is an impact, how will students with SEN display SRL behaviours differently given corrective or differentiated feedback?

2. Method

This study employed a mixed method, quasi-experimental with repeated measures pre-test-treatment-post-test design.

2.1. Participants

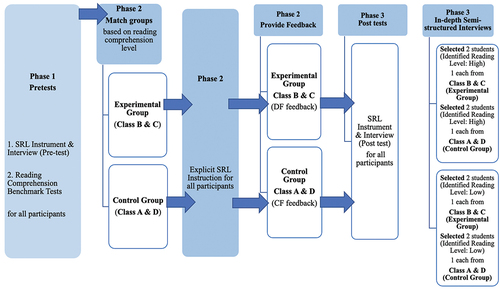

Participants were forty-five 13- and 14-year-old students from a SEN school in Singapore. They consisted of 30 males and 15 females (N = 45) diagnosed with mild intellectual disability and/or autism of IQ ranging from 50 to 70. They were from four intact classes. As the classes contain students of diverse ability, comparison groups were created by matching students on reading ability across two classes, in order to present students with learning tasks on reading comprehension. Figure shows the outline of the experimental design.

The experimental group was provided differentiated feedback (DF, N = 24) and the treatment comparison group (CF, N = 21) was provided corrective feedback only. Of these, one student from the DF group and one from the CF group did not complete the post-test due to indefinite medical leave.

Informed consent was obtained from students’ parents through a telephone call. They were also given a printed Information Sheet and an attached parental consent form. Students were briefed on details of the interventions, video-recording and interview processes. Student consent was obtained on a simplified student consent and assent from.

Students were also informed of their right to take a break or withdraw from their voluntary participation at any time during the interview process or lessons. All identifiers were removed from the data to assure privacy, anonymity and confidentiality. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Nanyang Technological University (NTU)’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

2.2. Instruments

Before intervention, benchmark reading passages and their corresponding running records from the AtoZ reading resource website (LAZEL, Citation2019), were used to assess the students’ reading ability.

The groups were also split further by reading ability into low reading and high reading groups for further comparisons. According to the reading AtoZ benchmark tests, the Low Reading group was assessed to be at instructional level A to G, while the High Reading group was assessed to be at Level H to N. The groups were split into Low Reading group (DF, n = 8; CF, n = 6) and High Reading group (DF, n = 15; CF, n = 14). Refer to Appendix B for participant data.

This was assessed to target reading instruction, not to assess performance or improvements in reading ability after the intervention. This is because the aim and scope of this study was to focus on SRL, not on performance outcomes in reading.

A quantitative measurement of SRL was obtained on an instrument modified from H. Y. Tay’s (Citation2011) self-report questionnaire of 35 items based on the Self-Regulated Learning Interview Schedule (SRLIS) (Zimmerman, Citation2000). The instrument was shortened to a total of 13 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale.

Questions 1 to 5 were related to the Forethought Phase. Questions 6, 7, 9 and 11 were for the Performance Phase, and Questions 8, 10, 12 and 13 were for Self-reflection. The highest total raw score to be obtained on the SRL instrument would be 65, if the highest point of 5 on each question was scored and the lowest raw score would be 13, with the minimum score of 1 on each question.

A high level of internal consistency of the full SRL scale was indicated by Cronbach’s alpha at pre-test, α = 0.80 and at post-test, α = 0.86. However, because of the small number of questions in each phase, the reliability scores were lower in each subscale. At pre-test, the Cronbach’s alpha was Forethought (α= .62), Performance (α= .47), and the Self-reflection (α= .61). At post-test for each subscale, Cronbach’s alpha was at Forethought (α= .78), Performance (α= .57) and the Self-reflection (α= .75).

The language was simplified to suit learners with learning disabilities who may comprehend language of ages nine to 12. Some open-ended question prompts taken from the original Self-Regulated Learning Interview Schedule (SRLIS) (Zimmerman, Citation2000) for eliciting more details on the questions, for example, for strategy use, “Do you use any method/way to help you remember information (what is in the passage)?”

The instrument, shown in Appendix A, took 20 to 25 min to be administered in a one-on-one interview process by the teacher-researcher. To elicit and clarify responses, visual cue cards and some open-ended question prompts taken from the original SRLIS were used.

2.3. Procedure

All four classes were taught nine English Language reading comprehension lessons, each lasting 45 min, by the teacher-researcher. Lessons were taken twice a week over a duration of 7 weeks. Figure shows the flow of the nine reading lessons. In the first lesson, the teacher demonstrated setting process and outcome goals. All students were guided to select and prioritise their goals on a “Yes, No, Maybe” template.

In subsequent sessions, explicit, direct instruction on SRL was followed by guided and independent practice. SRL strategies taught for reading included task strategies such as brainstorming, visualising the story, rereading the passage, highlighting details and matching question to answer. It was emphasised that students could use them whenever they read to become better at reading.

Feedback intervention was presented throughout the lessons. Table displays examples of differentiated feedback presented. The students were presented with the feedback during the brainstorming and discussion and while they attempted to answer the questions

Table 1. Examples of feedback

During each lesson, students were presented with one reading passage suited to their reading ability and a comprehension quiz of five multiple-choice questions. At the end of each lesson, students self-assessed their performance on their goals as “poor,” “okay,” or “well done” by colouring one to a maximum of three stars on a given self-monitoring log sheet. Verbal feedback was also provided during this process. Including a self-monitoring sheet, in each lesson, each student would typically receive minimum four to about eight feedbacks related to their reading task.

In Lessons 2 to 4, the skill of finding details was taught, including strategies of highlighting and matching question to answer. In Lesson 6 to 8, the skill of prediction was taught including the skill of reasoning based on clues within the passage and writing notes on them. As such, the strategy use was compared for pre- and post-data from Lesson 2 with 4 and Lesson 6 with 8.

After lessons 2, 4 and 8, eight students attended brief one-on-one, in-depth interviews on the same day after school in a vacant classroom. To obtain a representative sample, students of high or low reading level and one each from the experimental and control group were selected. They gave responses on their learning after each task phase according to Zimmerman’s model.

All student participants and interviewees were debriefed after the intervention sessions and interviews.

2.4. Data analyses

To find the effect of explicit SRL instruction, two-tailed paired group t-tests were conducted for the overall SRL score and also the SRL scores at each phase after checking for the normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. However, if the sample violated the assumption of symmetrical distribution, then a non-parametric two-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to determine whether there are median differences in the repeated measures of two paired groups at pre- and post-intervention.

Statistical significance was set at a p-value of less than .05, for rejecting the null hypothesis that the differences in means are due to chance. Once it was established that both control and intervention groups benefitted from the explicit instruction of SRL, further comparisons were made to explore the effects of differentiated feedback on SRL.

To find the effect of differentiated feedback, post-test SRL instrument scores for the experimental (DF) and control (CF) groups were analysed using with further comparisons at each SRL phase, after checking for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. However, if the sample violated the assumption of symmetrical distribution, then a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used (Heiman, Citation2001).

The DF and CF groups were also split further by reading ability into low reading and high reading groups for further comparisons, using the Mann-Whitney U test. This was to determine the effect of feedback by reading ability groups. Refer to Appendix B for participant data.

The Low Reading group was assessed to be from AtoZ Level A to G (DF, n = 8; CF, n = 6) and High Reading group at Level H to N (DF, n = 15; CF, n = 14). This allowed for further comparisons, using the Mann-Whitney U test to determine the effect of feedback by reading level.

The student responses to the open-ended interview questions in general, post-intervention scores on the SRL instrument. Further qualitative data were collected in three, brief in-depth, semi-structured interviews. Table contains an excerpt of the items, consisting of a total of 15 questions in the semi-structured interviews. These interviews were transcribed from the video-recordings.

Table 2. Excerpt of items in the semi-structured, in-depth interview sessions

From the data in transcripts, the teacher-researcher grouped together and coded responses according to whether they indicated Forethought as in planning and goal-setting or the use of strategies in Performance phase. For Self-Reflection, the responses provided reasons or attributions towards their planning or strategy use from the previous phases according to Zimmerman’s model. The quotes that were similar and repeated in the interviews into a priori codes of “goals,” “strategy use” and “self-reflection”.

As shown in Table , new codes under “self-reflection” emerged such as “self-check,” “consequences” and “self-efficacy” also emerged. Initially, these were organised as “metacognition,” “behaviour” and “motivation” (Zimmerman, Citation1990) according to the definition of SRL. However, many of the responses overlapped could not clearly categorise student-initiated behaviours that signalled metacognitive awareness compared to those actions directed by teacher or feelings.

Table 3. Themes arising from the coded transcripts

To reach an agreement on the categorisation of the codes, the second author who is an expert on SRL provided an external review and discussion on the codes, advising for further clarification based on the emerging patterns. Thereafter, a priori codes were reorganised using the definition of Skill and Will from McCombs and Marzano (Citation1990). The recurring patterns of self-beliefs, reactions, feelings and attributions made by students were classified under the common theme of Will, while responses on strategies and skills in different phases of SRL were considered Skill.

A third source of data was also obtained to support the data from a self-reported questionnaire on strategy use. These data were from counting instances of accurate strategy use in student assignments for highlighting details in Lesson 2 compared with Lesson 4. Similarly, all student assignments from Lessons 6 and 8 were coded for strategy use such as highlighting the correct details, the clues in the context and written notes on their paper.

Such additional data allow teachers to assess if students actually use the skills and strategies taught in the classroom and whether they apply them accurately (Schunk & Rice, Citation1993). In this study, strategy use was not analysed but reported as descriptive statistics. Also, correct answers on the assignments or the mistakes made were not coded or analysed as this study focused on SRL, not performance outcomes. Both quantitative and qualitative results have been integrated and discussed in a complementary manner in the next section.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative results

3.1.1. Effect of explicit SRL instruction overall SRL scores

The Shapiro–Wilk tests of normality were non-significant in overall SRL scores. Refer to Appendix C for data on the tests for normality. Hence, paired-samples t-tests were conducted to compare the overall SRL in pre and post conditions. There was a significant difference in SRL scores for pre (M = 42.07, SD = 9.32) and post (M = 47.37, SD = 10.04) conditions; t (42) = −5.15, p < .001. These results suggest that intervention has an effect on total SRL scores. Specifically, our results suggest that when intervention was given, the mean of SRL increased (Mean Difference = −5.30).

In addition, there was a significant difference in the SRL scores for pre (M = 40.69, SD = 10.16) and post-SRL scores (M = 46.13, SD = 9.63) in DF group; t (22) = −3.35, p = .003. However, there was a non-significant difference in the scores for pre (M = 43.65, SD = 8.22) and post-SRL scores (M = 48.80, SD = 10.56) for CF group; t (19) = −4.17, p = .001. This finding suggests that although all students benefited from the explicit instruction on SRL, the feedback received by the DF group added further to the positive effect.

3.1.2. Effect of explicit SRL at each phase

Further paired-samples t-tests were conducted to compare pre- and post-intervention SRL scores at each of the three phases. Significant statistical differences were found at the Forethought phase with pre (M = 15.44, SD = 4.24) compared to post-SRL scores (M = 17.98, SD = 4.52); t (42) =-4.05, p < .001 and at the Performance phase with pre (M = 12.49, SD = 2.94) compared to post-SRL scores (M = 14.05, SD = 3.39); t (42) =-2.81, p = .008.

As for the Self-reflection phase, because the sample violated the assumption of symmetrical distribution, the non-parametric two-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank test was used instead. Of the participants, 25 students showed improvement in post SRL scores compared to pre SRL performance, whereas 8 out of 43 showed no improvement. There were significant median differences in SRL scores (Mdn = 25) for pre (Mdn = 15) compared to post scores (Mdn = 16); z= −2.82, p = .005.

3.1.3. Effect of differentiated feedback

There was non-significant median differences in SRL score (Mdn = 8) for CF (Mdn = 149) compared to DF score (Mdn = 15); z = .55, p = .58. Also, in comparing CF and DF post-test scores, there was non-significant median differences in SRL score (Mdn = 9) for CF (Mdn = 75) compared to DF paired score (Mdn = 85); z = 1.44, p = .14.

A Mann-Whitney U test was run to determine if there were differences in SRL score between DF and CF. Distributions of the SRL score for DF and CF were similar, as assessed by Forethought Phase, Performance Phase, and Self-Reflection Phase. SRL score for CF (mean rank = 23.35) was non-significantly higher than for DF (mean rank = 20.83), U = 203.00, Z=-.658, p = .511.

3.1.4. Differences at SRL phases

The phase data were also analysed to compare between the CF and DF groups. At the Forethought phase, there was significant statistical difference for both CF scores for pre (M = 16.20, SD = 4.15) and post (M = 19.10, SD = 3.96) conditions; t (19) =-4.06, p = .001 as well as DF scores pre (M = 14.78, SD = 4.29) compared to post (M = 17.00, SD = 4.83) conditions in DF group; t (22) = −2.21, p = .038.

However, at the Performance phase, while there was significant statistical difference for the CF group with pre (M = 12.50, SD = 2.98) compared to post (M = 14.35, SD = 3.72) conditions; t (19) = −2.11, p = .05, it was not the case with the DF group with pre (M = 12.48, SD = 2.97) and post (M = 13.78, SD = 3.13) conditions for DF; t (22) = −1.82, p = .08.

Lastly, at the Self-reflection phase, there was a non-significant difference for the CF group in the scores for pre (M = 14.95, SD = 3.80) and post (M = 15.35, SD = 3.67) conditions; t (19) = −.818, p =.423. However, there was a significant difference in the scores for pre (M = 13.43, SD = 3.95) and post (M = 15.35, SD = 3.59) conditions in DF group; t (22) = −3.28, p = .003.

3.1.5. Differences in the reading ability groups

Further tests were conducted using the Mann Whitney U to compare the High Reading Ability CF, with High Reading Ability DF. The findings showed that the DF High Ability (mean rank = 12.87) was non-significantly lower than for that in the CF High Ability group (mean rank = 17.29), U = 73.00, z=-1.40, p = .162. Similarly, SRL scores for DF Low Reading Ability (mean rank = 9.22) were non-significantly higher than for that in the CF Low Ability group (mean rank = 6.17), U = 16.00, z=-1.30, p = .193.

3.2. Qualitative findings

3.2.1. Analysis of artefacts

The descriptive statistics in Table shows that students in both groups improved in accurate strategy use in their assignments, consistently up to Lesson 8. In Lesson 8, even though notes copied and written were part of strategy use, they were counted as separate instances, not included in strategy use, in order to show students’ quality of work. These data complement the quantitative results.

Table 4. Average instances of strategy use in assignments

Even though quantitative differences between the two feedback groups were not statistically significant, the findings in strategy use in student assignments revealed differences in the quality of work produced. The DF group had on average more instances of accurate strategy use in all lessons compared to the CF group. As expected, students in the high reading group from both CF and DF had on average more instances of accurate strategy use than those in the low reading level.

When only copying notes from teacher example is counted, those in the high reading level in the CF group of copied more notes on average compared to those of high reading level in the DF group. Still, if both notes copied and notes written are counted, students of high reading level in the DF group had copied and written more notes with an average of 13.63 instances compared to those of high reading level in the CF group, with an average of 12.86.

Those of low reading level in both CF and DF groups had copied or written fewer notes compared to those of high reading level, respectively. Still, of students of low reading level, those in the DF group copied or wrote more notes on average, 3.44 compared to the average, 3.00, of low reading level in the CF group both in Lesson 6. This finding was consistent in Lesson 8.

3.2.2. Analysis of interview data

The interview responses gathered from the general (involving all students) and in-depth interviews (with selected students) were organised into themes of Will and Skill. In this study, will is defined as a state of motivation that is “integrally related to mood and affect” (p.52), involving emotional regulation, desire and effort (McCombs & Marzano, Citation1990), while Skill is defined as cognitive ability or metacognitive capacity, including the self-awareness of learning goals and ability or application of strategies that are used in support of goals (Panadero & Alonso-Tapia, Citation2014). Table shows the examples of quotes from the interviews at each phase to illustrate how feedback affected students’ Will and Skill.

Table 5. Findings in the SRL phases

3.2.3. Forethought phase

Though all students were generally to be more self-aware of goals, there was a difference in Skill between the two groups. The DF group benefitted in knowing targets and details in their goals, while the CF group aimed for correct answers. This was found in students in both high and low reading levels.

In the theme of Will, both groups showed a sense of satisfaction or self-efficacy through their feelings of achievement when they were asked how goal setting helped. Students in both high and low levels in the DF group displayed positive motivational beliefs and self-reflected on their goals.

In the CF group, those of high reading levels, meaning high Skill, were found to be similar to students in the DF group in self-reflecting on why they need to read. Those of low level also mentioned engaging in compensatory behaviours, like helping friends, that influenced their affect. This difference in Will, in their motivational beliefs towards engaging in their learning, can affect their volition in effort into their learning tasks in the Performance phase.

3.2.4. Performance phase

Both feedback groups mentioned use of strategies and seeking help from friends, parents or teachers. In terms of their Skill, those in the DF group mentioned taking steps towards their personal development regardless of their reading level. There were only three students in the CF group of high reading level who self-reflected on their strategy use.

In the DF group, students in both low and high levels self-reflected reasons for or not seeking help, like wanting to figure things out for themselves. In contrast, students in CF, even those of high level, focused on obtaining correct answers, and appeared to avoid asking for help, even those who were of high ability, saying “If I don’t know, talk quiet, High very soft.” Those of low ability also waited for teacher cues and tended to make statements that attribute to task difficulty saying “sometimes I can’t understand. Cause I so confused” instead of asking for help.

Regarding Will, both groups shared feelings about difficulties in reading and motivated themselves to cope with difficult questions or ignore distractions. Those provided with DF displayed positive instances of Will, or volition in putting in effort even in difficult tasks, regardless of their reading level.

It was surprising that those given CF of high reading level exhibited Will, being better able to self-reflect in the Forethought phase but exhibited negative instances of volition in the Performance phase. They mentioned choosing to avoid tasks by engaging in other “feel good” activities when faced with difficult tasks. These negative instances of Will suggested that Skill alone may be insufficient in driving students’ volition to decide to pursue actions towards their learning.

3.2.5. Self-reflection phase

Those in the DF group were better able to explain how they checked answers, reflect on their strategy use and explain how they self-checked their answers. The CF group seemed uncertain. This benefit of DF feedback in terms of Skill was regardless of reading level. Only two students in the CF group, one each from high and low reading level, were like the DF group.

Most in the CF group, even of high reading level, mentioned depending on others like teachers or parents to find mistakes in their work. Then, they reacted accordingly to check their answers again. This means that most students provided CF displayed negative instances of Skill. Such negative instances of Skill seemed to impact Will or volition such that students took reactive, not proactive, steps of actions towards their learning.

Both feedback groups were found to be similar in their Will. They based their self-judgements on obtaining correct answers and attributing wrong answers to task difficulty. Both groups displayed feelings of frustration or confusion when faced with challenging tasks.

Differences were that those provided with DF made self-efficacy attributions to their ability and effort. They saw corrections as a learning opportunity and displayed Will to achieve in their learning, regardless of their reading levels.

However, those in the CF group saw corrections as an adverse consequence, adding that they were unhappy, upset or angry. Such strong emotions about task difficulty and corrections can be linked to negative instances of Will or volition towards tasks, also affecting a sense of self-efficacy, which, in turn, may affect effort and volition towards future tasks.

Not surprisingly, students in the CF group self-reflected external reasons such as not being able to read. One unexpected finding was that those of low reading level in the CF group were like those in the DF group in displaying positive Will, citing their own ability for their self-satisfaction, saying, “you can do whatever for yourself” or “If I find mistakes, I just erase and write again.” This could be because students of low ability, being unsure of their Skill, may depend on Will. This can result in a positive focus on their effort in tasks or sometimes negative attributes such as one student in the CF group mentioning “too lazy to think, because I’m lazy.” These aspects, especially the Will displayed strongly in this phase, will affect students’ volition towards subsequent learning tasks, in the next cycle of SRL.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the effect of differentiated teacher feedback on students’ SRL in a SEN context. The findings contribute to a better understanding of both constructs (SRL and teacher feedback) and suggest implications at the practice and policy level.

4.1. Explicit SRL instruction

The present study contributes to the extant SRL literature in suggesting that students with SEN, just like their mainstream counterparts, benefit from explicit SRL instruction. It adds to the limited research in SRL involving students with SEN (Nelson & Manset-Williamson, Citation2006) and increased strategy use (Butler et al., Citation2005). The qualitative data of strategy use observed from assignments complemented this quantitative finding.

Past research often narrowly focussed on particular SRL aspects such as goal setting. In the present study, the mixed-method design allowed for multiple sources of data to explore SRL in a holistic manner at the three cyclical phases using Zimmerman’s (Citation2002) model. The quantitative findings suggest that students benefitted from SRL instruction, at the Forethought phase and Performance Phase but not significantly at the Self-reflection phase. The findings from interview data are consistent with the benefits of explicit SRL instruction on goal-setting including reflection (Buzza & Dol, Citation2015; Kang, Citation2010) and enhanced self-efficacy (Schunk & Rice, Citation1993) in students with SEN.

For students with SEN, it is important for the curriculum to include explicit instruction in SRL, involving teacher modeling and observational learning. The finding that students had inaccurately evaluated tasks suggests that students may be unsure how to assess their performance, leading them to display reactive rather than proactive SRL. This concurs with Nelson and Manset-Williamson’s (Citation2006) finding that learners with SEN tended to inflate their sense of self-efficacy at pre-test and adjust it after performance outcomes are known. Explicit instruction in SRL seems to benefit students’ with SEN in engaging in accurate self-judgments based on their tasks, which in turn, affects their self-efficacy.

Few previous studies mention the influence of affect or motivational components on Will, even in mainstream settings (Vandevelde et al., Citation2011). This study sheds further light on this area with the finding of these students’ Will to persist in tasks, even those that they find challenging (Butler et al., Citation2005). This could mean that explicit instruction in SRL facilitates volition in help-seeking and desire to invest effort in coping with difficult questions or tasks (Chou et al., Citation2018).

It might also be because explicit instruction equipped students with Skill in task strategies, therefore, empowering them with strategic actions they could take. This, in turn, appears to enhance their Will to never give up. Overall, the findings suggest that the DF group benefitted more from the explicit instruction than the CF group. These findings have important implications for the role of feedback in teaching SRL for students with SEN.

4.2. The impact of teacher feedback

The present study fills the gap in the lack of studies connecting SRL and how differentiated feedback impacts aspects of SRL in the SEN context. The qualitative findings provide valuable insights to Skill and Will at each phase.

In the Forethought phase, quantitative finding in both the DF and CF groups is consistent with the qualitative responses. The positive instances of Will demonstrated regardless of reading levels in the DF group indicate the impact of feedback, the constructive reflection that is a type of Process-level feedback (FP) provided. The CF group with high Skill could also could reflect similarly. This seems to suggest that students with SEN of high reading level are perhaps better able to self-regulate their Will, given their Skill in learning tasks.

The CF group of low Skill appear to be affected by their Will where cognitive appraisals of the tasks may have discouraged them and prevented them from dealing effectively with negative emotion such as anxiety or hopelessness (Burić & Sorić, 2011). This was similar to Gaeta, Teruel and Orejudo’s (Citation2012) finding that students’ effort and persistence for goal achievement is controlled by their motivation and emotion and has an effect on the use of strategies to control and direct their mental processes.

At the Performance phase, surprisingly, significant differences were found when comparing pre- and post-SRL scores in both the CF group and not the DF group. This could be because CF placed value on their correct answers and the related CF that was provided, possibly increasing the effectiveness of CF (Sato & Loewen, Citation2018).

However, the qualitative findings were consistent with those in the Forethought phase, showing the impact of feedback especially on the DF group. FP had an impact on Skill added to past research involving students with SEN (Butler et al., Citation2005; Nelson & Manset-Williamson, Citation2006). The positive impact of DF was regardless of the reading level when notes written in Lesson 6 was compared to Lesson 8. Unlike the CF group, the DF group put in additional effort to write their own notes. They also mentioned using strategies and reflecting reasons for personal development and taking steps towards their learning throughout the phases.

Students with SEN given FP in the Performance phase seemed to be more willing to engage in volitional strategies to invest effort and take steps towards goals or mastery of skills. Those given CF tended to focus on correct answers. One implication is that teachers need to provide feedback for self-monitoring, perhaps including the use of self-recording for visual tracking of progress (Zimmerman & Kitsantas, Citation1999). This should importantly include on-going strategy-value information that can guide students in correcting their strategy use and in engaging in self-corrections (Butler et al., Citation2005). This is so that students are guided to invest effort or being certain in their Skill to try out strategies, not just to obtain correct answers.

Students in both low and high reading level given FP at the Performance phase mentioned Skill of seeking for help or Will in reflecting on whether to ask or not. Both high and low level students in the CF group seemed to avoid seeking help or reflecting upon their learning. As such, FP provided in the present study appears to be useful in guiding students with SEN to gauge learning situations and judge whether to depend on themselves or seek external help (Chou et al., Citation2018) and develop agency in seeking further feedback information for mastery toward learning.

Students with SEN given CF tended to view corrections with adverse reactions rather than as a personal development. This has implications for educating students with SEN in the use of volitional and emotional management strategies that could help students face their challenges in managing negative emotional reactions and lack of confidence to stay in pursuit of tasks (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2002). This means feedback to help students with SEN manage emotional and volitional challenges may be crucial in developing Will towards learning.

At the Self-reflection phase, the quantitative findings were non-significant. However, there were qualitative findings that students from the DF group expressed a sense of control over their learning (Grothérus et al., Citation2019) and mentioned investing more time and effort in their tasks in their self-reflections. FSR provided at this phase seems beneficial in enhancing self-efficacy in students with SEN and adjusting negative attributions arising from dissatisfaction. This concurs with past findings enhanced students’ sense of self-efficacy (Grothérus et al., Citation2019; Nelson & Manset-Williamson, Citation2006; Schunk & Rice, Citation1993) in students with SEN.

Although emotions and self-reactions might appear automatic, they can actually be controlled and learnt as part of SRL (Panadero & Alonso-Tapia, Citation2014). Teachers could provide scaffolding hints like “You should be able to” or a recording sheet that can signal to students their emotions and motivation (Järvelä, Citation2011). This can help make an abstract concept-like effort become more concrete and visually observable so that students with SEN can self-monitor their progress.

The special education curriculum should include feedback strategies for teachers and specify structures on how differentiated feedback, FP and FSR, should be provided to their students. Such structures or perhaps, feedback scripts, can help teachers direct feedback towards SRL, concurrently with the teaching of other educational skills. Teachers can perhaps use feedback scripts specially simplified in language suited for students with SEN (Kang, Citation2010).

4.3. Limitations and recommendations for further research

The findings presented here are supported by previous research on exemplary modeling experiences enhancing self-efficacy beliefs in mainstream students (Zimmerman & Kitsantas, Citation2002) and in students with SEN (Nelson & Manset-Williamson, Citation2006). However, there are limitations to the findings because the SRL instrument used relied on self-report. Challenges with self-report may stem from students with SEN having difficulties in recalling strategy use.

Previous studies involving self-efficacy judgements found that students with SEN may respond by scoring or judging themselves higher even if they do not comprehend or have the wrong interpretation of the questions asked. This may result in students consistently overestimating or underestimating their use of strategies, leading to systematic error (Schunk & Rice, Citation1993; Van Loon & Roebers, Citation2020). This may explain why differences in SRL scores between the two feedback groups or between reading levels were found not to be statistically significant.

This study contributes an SRL instrument with good overall internal consistency and acceptable levels or reliability at its Forethought and Self-reflection subscales. The lower levels of internal consistency in the Performance subscale may be due to too few items in each subscale or that the open-ended question prompts included may have signalled the items as challenging or provided a sense of ambiguity to students with SEN (Zarcone et al., Citation1991). The instrument has been validated with mainstream students (H. Y. Tay, Citation2011) but not with those with SEN. Therefore, future research can focus efforts on developing and validating SRL instruments suitable for use with students with SEN and to explore how interventions can help students form accurate self-evaluations.

There is a need for further research on the saliency of the type of feedback provided at each phase, especially with the effect of explicit metacognitive instruction. This study was limited to CF being verbally provided and marked on paper, so studies on different types of CF that can be provided will be useful (Sato & Loewen, Citation2018). There is also so much more to how motivation, volition and affect are defined and related to learning tasks and interrelated to feedback effects as well as learner competencies and dispositions (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2002). Further research and exploration are necessary for clarity on how to facilitate agency in students, especially in the SEN context.

Another limitation is that the intervention duration may have been too short. Other studies had found large effect sizes and had found maintenance effects in students with learning disabilities (Berkeley & Larsen, Citation2018). Therefore, it is recommended that in further studies, the number of intervention sessions can be increased over a longer period and designed to study sustained improvements or effects maintained after a delay.

5. Conclusion

This study found that explicit instruction can facilitate SRL and explored how different types of feedback can impact Skill and Will of students with SEN. The findings urge us all to reframe students with SEN to be agentic learners who can engage in proactive behaviours. In schools, we need to support teachers with professional development and exposure to exemplary modeling in all aspects of SRL, including strategy use and self-monitoring as well as quality feedback practices. This will be a step towards helping students with SEN in their learning within and beyond school.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tay Hui Yong

Tay Hui Yong is a senior lecturer in the Learning Sciences and Assessment Academic Group, NIE, focusing on classroom practices that result in engaged learning, especially through Assessment for Learning (AfL). She has presented papers and her recent works include a book on authentic assessment published by Routledge, book chapters in scholarly books and research articles in peer-reviewed journals.

Nithiyah Sokumaran

Nithiyah Sokumaran is a lead curriculum writer at Thomson Kids Specialised Learning Centre, developing a primary curriculum and levelled supports for mainstream students who have reading, spelling and comprehension difficulties and present with dyslexia, ADHD and/or autism. She has been a special educator for the past 17 years and is keen on curriculum reform towards learner-centredness and developing self-determination in students with SEN.

References

- Alitto, J., Malecki, C. K., Coyle, S., & Santuzzi, A. (2016). Examining the effects of adult and peer mediated goal setting and feedback interventions for writing: Two studies. Journal of School Psychology, 56, 89–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.03.002

- Anderson, K. T. (2015). The discursive construction of lower-tracked students: Ideologies of meritocracy and the politics of education. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23, 110. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v23.2141

- Baker, L., & Cerro, L. C. (2000). Assessing metacognition in children and adults. In G. Schraw & J. Impara (Eds.), Issues in the measurement of metacognition (pp. 99–145). Buros Institute of Mental Measurements.

- Berkeley, S., & Larsen, A. (2018). Fostering self-regulation of students with learning disabilities: Insights from 30 years of reading comprehension intervention research. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 33(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/ldrp.12165

- Buric, I., & Soric, I. (2012). The role of test hope and hopelessness in self-regulated learning: Relations between volitional strategies, cognitive appraisals and academic achievement. Learning & Individual Differences, 22(4), 523–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.03.011

- Butler, D. L., Beckingham, B., & Lauscher, H. J. N. (2005). Promoting strategic learning by eighth-grade students struggling in mathematics: A report of three case studies. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 20(3), 156–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5826.2005.00130.x

- Buzza, D. C., & Dol, M. (2015). Goal setting support in alternative math classes: Effects on motivation and engagement. Exceptional Education International, 25(1), 35–66. https://doi.org/10.5206/eei.v25i1.7716

- Çakır, R., Korkmaz, Ö., Bacanak, A., & Arslan, Ö. (2016). An exploration of the relationship between students’ preferences for formative feedback and selfregulated learning skills. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 4(4), 14–30.

- Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

- Chou, C. Y., Lai, K. R., Chao, P. Y., Tseng, S. F., & Liao, T. Y. (2018). A negotiation-based adaptive learning system for regulating help-seeking behaviors. Computers & Education, 126, 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.010

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

- Gaeta, M. L., Teruel, P. M., & Orejudo, S. (2012). Motivational, volitional and metacognitive aspects of self regulated learning. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 10(26), 73–94. https://doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.v10i26.1485

- Gan, M. J., & Hattie, J. (2014). Prompting secondary students’ use of criteria, feedback specificity and feedback levels during an investigative task. Instructional Science, 42(6), 861–878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-014-9319-4

- Grothérus, A., Jeppsson, F., & Samuelsson, J. (2019). Formative Scaffolding: How to alter the level and strength of self-efficacy and foster self-regulation in a mathematics test situation. Educational Action Research, 27(5), 667–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2018.1538893

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

- Heiman, G. W. (2001). Understanding research methods and statistics: An integrated introduction for psychology. Houghton Mifflin.

- Holtzheuser, S., & McNamara, J. (2014). Bridging literacy acquisition and self-regulated learning: Using a SRL framework to support struggling readers. Exceptionality Education International, 24(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.5206/eei.v24i1.7707

- Järvelä, S. (2011). How does help seeking help?–New prospects in a variety of contexts. Learning & Instruction, 21(2), 297–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.07.006

- Kang, Y. (2010). Self-regulatory training for helping students with special needs to learn mathematics. ( Doctoral dissertation). https://doi.org/10.17077/etd.yucmgqwa.

- LAZEL. (2019). Reading A-Z. US State standards. Retrieved from https://www.readinga-z.com/curriculum-correlations/us-state-standards/

- Lindsay, S., Proulx, M., Thomson, N., & Scott, H. (2013). Educators’ challenges of including children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 60(4), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2013.846470

- McCombs, B. L., & Marzano, R. J. (1990). Putting the self in self-regulated learning: The self as agent in integrating will and skill. Educational Psychologist, 25(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2501_5

- Nelson, J. M., & Manset-Williamson, G. (2006). The impact of explicit, self-regulatory reading comprehension strategy instruction on the reading-specific self-efficacy, attributions, and affect of students with reading disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 29(3), 213–230. https://doi.org/10.2307/30035507

- Nind, M. (2008). Conducting qualitative research with people with learning, communication and other disabilities: Methodological challenges. ESRC National Centre for Research Methods, Retrieved from. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/491/.

- Panadero, E., & Alonso-Tapia, J. (2014). How do students self-regulate? Review of Zimmerman’s cyclical model of self-regulated learning. Anales de Psicologia, 30(2), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.2.167221

- Sato, M., & Loewen, S. (2018). Metacognitive instruction enhances the effectiveness of corrective feedback: Variable effects of feedback types and linguistic targets. Language Learning, 68(2), 507–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12283

- Schünemann, N., Spörer, N., & Brunstein, J. C. (2013). Integrating self-regulation in whole-class reciprocal teaching: A moderator–mediator analysis of incremental effects on fifth graders’ reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(4), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.06.002

- Schunk, D. H., & Rice, J. M. (1993). Strategy fading and progress feedback: Effects on self-efficacy and comprehension among students receiving remedial reading services. The Journal of Special Education, 27(3), 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/002246699302700301

- Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2007). Influencing children’s self-efficacy and self-regulation of reading and writing through modeling. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 23(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560600837578

- Scott, T. M. (2017). Training classroom management with preservice special education teachers: Special education challenges in a general education world. Teacher Education and Special Education, 40(2), 97–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406417699051

- Silver, R., & Lee, S. (2007). What does it take to make a change? Teacher feedback and student revisions. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 6(1), 25–49.

- Tay, H. Y. (2011). The use of self-regulated learning in authentic assessments ( Doctoral Dissertation).

- Tay, H., & Kee, K. N. N. (2019). Effective questioning and feedback for learners with autism in an inclusive classroom. Cogent Education, 6(1), 1634920. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1634920

- Tay, H. Y., & Lam, K. W. L. (2022). Students’ engagement across a typology of teacher feedback practices. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 21(3), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-022-09315-2

- Vandevelde, S., Van Keer, H., & De Wever, B. (2011). Exploring the impact of student tutoring on at-risk fifth and sixth graders’ self-regulated learning. Learning & Individual Differences, 21(4), 419–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.01.006

- Van Loon, M. H., & Roebers, C. M. (2020). Using feedback to improve monitoring judgment accuracy in kindergarten children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.05.007

- Wendling, B., Schrank, F., & Schmitt, A. (2007). Educational interventions related to the woodcock-johnson III tests of achievement. In Assessment service bulletin no. 8 (pp. 1–30). Riverside Publishing. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/cf25/1ca2238c909d9ca4928c418a598860599aa2.pdf

- West, R. L., Welch, D. C., & Thorn, R. M. (2001). Effects of goal-setting and feedback on memory performance and beliefs among older and youngeradults. Psychology and Aging, 16(2), 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.16.2.240

- Zarcone, J. R., Rodgers, T. A., Iwata, B. A., Rourke, D., & Dorsey, M. F. (1991). Reliability analysis of the motivation assessment scale: A failure to replicate. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 12(4), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0891-4222(91)90031-M

- Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educational Psychologist, 25(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2501_2

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeider (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166–183. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207312909

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (1999). Acquiring writing revision skill: Shifting from process to outcome self-regulatory goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(2), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.2.241

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (2002). Acquiring writing revision and self-regulatory skill through observation and emulation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 660–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.660

Appendix A:

Modified SRL Instrument

There is no right or wrong answer. Circle your answer.

Your teacher gives you reading comprehension work to do.

Appendix B:

Participants’ Reading Level & Matched Groups

Appendix C:

Data on Tests for Normality