Abstract

Education policy in recent years has dramatically repositioned the role and status of teachers, trainee teachers and teacher education in the UK and beyond. This paper focuses specifically on education policy in England; however, it has broader significance for those interested in education and teacher education in international policy contexts. Two corpora were constructed for the project; one collated education policy documents in 2010–2021, and another collated education policy documents in 1970–2009. The analysis used the corpus linguistic tool Wordsmith 8. Keywords, concordance, and collocation, were used to examine themes within the discourse of the focus corpus, supported by a critical policy discourse analysis frame. The themes identified in this analysis were governance (control) and marketisation (choice). These themes have strong connections to analyses of the Global Education Reform Movement (GERM) and contribute to understanding how education policy discourses can frame teacher education. The positioning of trainee teachers as both product and subject of initial teacher education in education policy documents is explored in the analysis.

1. Introduction

1.1. Education policy & global education reform

Education policy in the last twenty years has repositioned teachers and teacher education (Cochrane-Smith & Fries, Citation2002) in the UK (Stanfield & Cremin, Citation2013) and beyond (Olmedo et al., Citation2013). Teacher education policy is a distinct subset of education policy, with direct and immediate implications for educational practice and wider society (Tatto & Menter, Citation2019). Teacher education policy intersects higher education and school-based education. It holds implications not just for those under direct regulation by these policies but more widely for pupils as future citizens (Hartung, Citation2017) in addition to teachers, schools, the wider community and the economy (Barber & Mourshed, Citation2007; Olmedo et al., Citation2013).

Policy reforms have been major and rapid as teacher education has been a focus of significant policy intervention in England (Cochran-Smith, Citation2016; Darling-Hammond & Lieberman, Citation2012), mirroring a broader global pattern of reform and recalibration influenced by the 2007 McKinsey report (Barber & Mourshed, Citation2007) the OECD report Teachers Matter (Citation2005) and the “Teach for All” movement. Sahlberg (Citation2011, Citation2012) refers to this Global Education Reform Movement as GERM. GERM (Sahlberg, Citation2011) frames activities around the value and preparation of teachers in economic terms and encourages non-state actors to invest in and shape the processes of teacher preparation (and schooling). It reframes education as an economic activity in a global market, and educational problems (such as attainment gaps) as “teacher” problems. These ideas have spread internationally; for example, “Teach for All” began in America and spread to the UK, Australia across Europe and beyond exerting a global influence (Crawford-Garrett & Thomas, Citation2018). In framing educational problems as “teacher” problems, teacher education is problematised and framed as a problem to be resolved through policy (Mayer Citation2021).

Olmedo et al. (Citation2013) identify that global education reforms play out nationally through formal policy and internationally, with increasingly complex networks of actors participating in (and shaping) the training and preparation of teachers. National education policy offers insights about policy translation and implementation into practice at a local level (Menter, Citation2019).

Mooney Simmie and Edling (Citation2019) made a comparative analysis of teacher education policy in Ireland and Sweden, noting a marked shift in the construction of teachers from agents with a clear democratic assignment to functionally competent subjects of policy. Rönnberg (Citation2017)discussed the impact of marketisation on education in Sweden and the global activity of edu-business in constructing a schools crisis (problematisation) as a business opportunity for “edu-preneurs”. Mayer (Citation2021) argues that in Australia and England, teacher education is framed as “a politically constructed ideological policy problem” (p121). In this project, the corpora were constructed to examine the discourses in education policy documents and how they construct this “problem” at a national level. The research questions are: How do education policies in England from 2010–2021 construct teacher education? Is this distinct from previous education policies in England? Are there discourses discoverable through corpus-based discourse analysis of education policies in England that relate to discourses in global education reform?

1.2. Policy & Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA)

Policy documents are an important source of information for research. Policy takes us beyond the rhetorical flourishes we see in political speeches or campaign materials and instead articulates the intentions of the government in concrete terms. As Mooney Simmie and Edling (Citation2019) argue: “Policy documents are an important vehicle for powerful voices to legitimate what is thinkable and what is unthinkable in society, and to normalise viewpoints that need to be revealed.” (p833). However, policy analysis is a contested area of study plagued by theoretical and methodological critiques, as Taylor (Citation1997) and Ball (Citation1994) discussed.

The method adopted in this paper is a corpus linguistics based critical discourse analysis (CDA).CDA approaches identify patterns of language use and the construction of ideas and critically examine these discourses to explore their role in a broader socio-political context (Halliday, Citation1978). There are different methodological and theoretical dimensions in CDA approaches (Fairclough et al., Citation2011) though these are all based upon a critical and systematic reading of text. Burch (Citation2018) conducted a CDA of the SEND code of practice (2014), exploring the idea of governance and governmentality concerning ideas of preparation for adulthood and disability.CDA can make use of individual texts (as in Burch, Citation2018) or multiple texts. Corpus approaches make use of a body of texts.

Corpus linguistics is a computer-based approach for analysing text using statistical tools. Corpus linguistics can be used as a basis for discourse analysis as it offers a systematic method to identify points of analysis. The use of corpus-based CDA in education policy is a relatively new area of study. Where it is conducted effectively, corpus-based CDA addresses some critiques of interpretive approaches by using a systematic methodology and replicable design. Mulderrig has substantially contributed to scholarship using corpus based CDA of education policy in England.

Mulderrig (Citation2011) examined the role of language and governance in New Labour educational policy using a corpus of educational policy texts. The lexico-grammatical analysis offers evidence of using the pronoun “we” to forge unity and consent. The analysis Mulderrig (Citation2012)conducted identified deixis in educational policy using corpus-based CDA, making the case that policy rhetoric under new Labour included dramatically more personalisation and linked this to third-wave political thinking, specifically about education as a response to global challenges. In 2014, Mulderrig critically examined the construction of “enabling participatory governance” in education policy discourse, which examined the discourse of “participation” as a rhetorical tool (Mulderrig, Citation2014).

1.3. Education policy context

In 2010, the Conservative party in England formed a coalition government with the Liberal Democratic party. Following re-election, a majority was established, and a period of Conservative government remained for over a decade. During this period, prime minister Mr Cameron and later governments adopted a series of major policy reforms. In this project, the political movement to reform is called the “modern conservative era” (spanning 2010 to the present) to distinguish it from previous conservative reform movements (such as Thatcherism, for example).

Michael Gove, appointed as secretary of state for education in the 2010 coalition government, made significant changes to the education landscape in England through major educational reform (Kauko, Citation2022). These significant reforms included: the establishment of free schools and the roll-out of academies (Academies Act, Citation2010); reform of Early Years, SEND and the Primary National Curriculum; changes to the Secondary National Curriculum and assessment regimes at GCSE and A- level, implementation of standardised assessments across schooling phases (Hilton, Citation2018; Pratt, Citation2016). The removal of public funding across a range of facets, including the education maintenance allowance (Balloten,Citation2011) and schools buildings programmes, accompanied a rise in tuition fees for higher education and increasing opportunities for private providers. Major reforms of teacher education and a reconsideration of the role of universities in teacher education were introduced concurrently with a reimagining of the status of teaching (Maguire, Citation2014, Department for Education Citation2010). In addition, teachers in “free schools” were not required to be qualified, and academies and free schools did not have to abide by national public pay and conditions regulations for teachers, new “Teacher Standards”(Department for Education, Citation2011) were introduced, and new methods of teacher preparation via the schools direct route were introduced in this period (Macbeath, Citation2011). This era of reform has been strongly identified with minister Gove (Finn, Citation2015). However, these reforms could be considered the beginning of a much longer-term programme of reform by the “neoliberal modernisers” (Wright, Citation2012) in the modern conservative government. Changes implemented during Mr Gove’s ministry from 2010–2014 have generally persisted (Spicksley, Citation2022), and the trajectory of neoliberal modernisation continues to the present.

The “modern conservative” period was selected to capture a particular moment education policymaking in England, with the educational reforms delivered as a “raft” with the explicit intention to build a coherent policy framework to reform teacher education: “The Early Career Framework builds on Initial Teacher Training and provides a platform for future development” (Department for Education, Citation2019, P5.) As such, this short period of bold policy intervention presents an opportunity to examine discourses in action, explicit and implicit, in the language of education policy.

2. Method

Two corpora were constructed for this project, one collated education policy documents in the modern conservative era (2010–2021) and a second collated education policy documents in the period (1970–2009). The two corpora were analysed using corpus linguistics tools to identify keywords, and then further exploration of concordance and collocation were used to examine themes within the discourse.

2.1. The focus corpus: Modern Conservative Education Policy (MCEP)

The focus corpus in this project comprised ten education policy documents dating from 2010 to 2019 relating to teaching and teacher education. It includes legislation, review reports and statutory guidance documents. The focus corpus spans four periods of government led by three prime ministers. This corpus was specially constructed for the project, and it comprises documents that capture teacher education policy in the modern conservative era. The focus corpus is called the Modern Conservative Education Policy corpus (MCEP). This corpus was constructed to capture the “zeitgeist” of contemporary conservative education policy (in the Cameron, May and Johnson periods of governance). It is referred to throughout this work as MCEP (Modern Conservative Education Policy corpus) for brevity, though perhaps a longer acronym like MCTEP (to include teaching) might have been more specific.

2.2. The reference corpus: Education Policy Corpus (EPC)

The MCEP corpus was compared with a reference corpus of education policy documents from the period 1970–2009. The reference corpus spans thirteen periods of government led by seven prime ministers. The reference corpus includes government briefings, parliamentary briefings (circulars), reports following reviews commissioned by governments, white papers, green papers, statutory guidance documents and acts of parliament (laws). The reference corpus comprises 40 education policy documents related to teaching and teacher education and is named the Education Policy Corpus (EPC). The reference corpus reflects language use in education policy documents. Comparison with a large body of reference material can highlight specific language practice in the focus corpus, in this case, the MCEP. The EPC represents several different eras of government policymaking and offers a diachronic insight into the language use of policy. A range of document types are included in this corpus to ensure a representative comparison with the MCEP.

The benefit of a specialist corpus for comparison is that it reflects specific language practices; in this example, a mixture of policy and legislative language is represented, different from everyday English. A non-specialist comparative corpus would reflect the differences between the language of policy and everyday language in practice. However, it would not give a focused insight into the construction of teacher education in education policy, which is the focus of this study.

2.3. Limitations

Two natural limitations of this method are the size and static nature of the corpora. This project uses two domain-specific corpora tailored to reflect the research topic. However, as Sinclair (Citation2005) notes, the more domain-specific the research interest, the smaller the corpus can be. In contrast with some of the mega corpora based research, this project smaller corpora for analysis (274392 words in the MCEP focus corpus, 2308156 words in the EPC reference corpus). The decision to use specialist corpora was a purposeful design choice to capture the use of legislative English more accurately than a larger non-specialist corpus would.

The use of static corpora is also a limitation of this project. The corpora constructed for this project are static. As such will become outdated without continuous maintenance- they offer a snapshot of a time period which was part of the intention of the design. They are designed to capture a “moment” and compare with a broader time scale but will not be able to offer more dynamic insights into policy issued after the date of construction.

2.4. Materials

The corpora were prepared by collating public domain policy documents into readable format for corpus analysis software. Wordsmith 8 (Scott, Citation2020) was used to search the corpora and compile descriptive statistics. Descriptive statistics can be used to identify features of the language in the focus corpus. Raw frequency counts would not offer comparable data as the corpora are different sizes. Instead, the relative frequency is calculated per thousand words (ptw), and this “normalised” frequency measure is used throughout. (Normalised frequency is the term used in linguistics to describe relative frequency). Keywords, concordances and collocation are reported in this project. Keywords identify the frequency of unusual words in comparison to a reference corpus and are an important basis for corpus analysis.

A word list was generated (using wordsmith 8 software) for each corpus, and the words generated were sorted by normalised frequency. The MCEP and EPC word lists were used to identify candidate keywords. Candidate keywords were assessed for keyness. Keyness is defined as “the statistically significantly higher frequency of particular words in a corpus under analysis in comparison with another corpus” (Baker et al., Citation2008, p. 278). Keyness in this study gives an indication of how related the focus corpus (MCEP) and comparison corpus (EPC) are to one another. Keyness measures can help to reveal the presence of discourses, but keywords are not discourses in of themselves; instead, they point us towards concepts “that may help to highlight the existence of types of (embedded) discourse or ideology” (Baker, Citation2004, p. 347).

In this project, keyness was determined using a combination of three statistical tests (using the Wordsmith8 software): Dunning’s Log Likelihood (LL) measures “keyness” in terms of statistical significance (this is preferable to chi-square because chi-square depends on normal distribution which is not present in a whole corpus.) Bayes Information Criterion (BIC): BIC uses LL and the size of the two corpora—Bayes factor as degrees of evidence against a null hypothesis. BIC score is an important measure to consider when evaluating keyness, as the size of the corpus has an impact on measures of significance. Log ratio- this measure is a binary log of the ratio of relative frequencies developed by Hardie (Citation2014). It is a procedure to highlight effect size rather than statistical significance and is a simple-to-understand measure- because it is a binary log, every point difference represents a doubling of the effect size. The statistical tests provide a measure of confidence by exploring effect size rather than just looking at frequency differences or the statistical significance of these differences. Gabrielatos (Citation2018, Citation2012) warns us that statistical significance is an “unreliable and misleading” measure of keyness alone because of the impact of sample size on this measure; therefore, it is useful to use multiple measures to identify keyness.

The keywords identified were examined further using concordance and collocation. Concordance links each search word with the text it appears with (the word and its concurrent sentence). Collocation reports the commonly co-occurring words and their statistical significance. This data offers a “way in” to examining the text and provides a focus for a more detailed analysis. Further analysis is important in offering a more contextually embedded interpretation of the text and discourse, though this is still a limited interpretation given the need to focus on some specific elements of text rather than others. Hyatt (Citation2013) offers a useful heuristic for educational policy analysis that underpins the critical discourse analysis in this work. The frame functions in two parts; the first is policy context. The macro context explores features such as drivers, levers (for implementation), trajectory (impact) and the warrant (or justification) of policies. Policy context is explored in the context and discussion sections of this work. The second part of Hyatt’s (Citation2013) frame is the deconstruction of policy. Policy as a social semiotic activity is examined using various tools to identify specific features such as legitimation, interdiscursivity, intertextuality, evaluation, presupposition/implication and the lexico-grammatical construction of policy. The deconstruction part of Hyatt’s frame is used in the discussion of results and conclusion of this work.

3. Results

3.1. Corpus analysis results

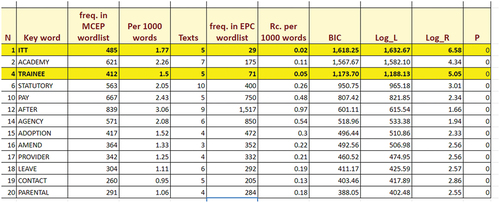

Keyword analysis was conducted using the MCEP word list as the focus corpus and the EPC wordlist as the reference corpus. Each Candidate Key Word (CKW) was ranked by effect size and statistical significance to construct a keyword (KW) list. A minimum threshold was applied so that words which appeared in only one or two texts in the focus MCEP corpus were excluded from the ranking. This was to prevent data from a single text skewing the data as a whole and undermining the analysis. The focus MCEP corpus comprised ten texts, so controlling for distortion of this kind was important to ensure the representativeness of KW identification. The criteria for candidate keywords (CKW) to be identified as keywords (KW) in this analysis were: words must appear in three or more texts (to control for distortion effects) and must reach keyness criteria in 3 measures BIC, LL, and Log R. In Figure , the keywords meeting the criteria are presented.

Figure 1. Keywords identified in the MCEP corpus.

The top 3 keywords were ITT, Academy and Trainee. The keywords which followed scored significantly lower on the three measures of keyness (particularly on the Log R measure) and will not be explored further in this paper.

Academy is a keyword by our criteria; this term recently gained greater importance due to the “Academies” (schools and Free schools programmes) of new Labour and modern Conservative governments. As such, the term has a particular policy significance and reflects wider discourses in policy and public life. The analysis of this KW will appear in an associated publication (forthcoming) and not be explored further here.

The terms ITT and Trainee met the criteria to be considered keywords in this project. This paper examines these two keywords in detail and reflects on the discourses they help to uncover. Just these two keywords (ITT and Trainee) form the basis of this article to offer a rigorous examination within publication word limits.

The keyword analysis of the MCEP word list revealed the term ITT to be key. The term ITT is an abbreviation of “Initial Teacher Training”. “ITT” occurs with high relative frequency in the MCEP- with 1.77 occurrences per thousand words (n 485 occurrences) in the MCEP as compared to 0.2 ptw (n 29 occurrences) in the EPC reference corpus. The three measures used to assess keyness confirmed this [BIC score 1618.25; Log L 1632.67; Log R 6.58]. Concordance for this term was computed to explore the usage of the term in the MCEP corpus.

3.2. Keywords identified in the MCEP corpus

We can observe how the term ITT is used by looking at the word list, computing the concordances for the words appearing with high frequency in this word list, and then looking at collocate clusters. Clusters are strings of three or four words that occur around the word selected and give context for word use in the corpus. Clustering words into recognisable phrases or expressions using the corpus analysis software makes identifying descriptive themes simpler than a line-by-line analysis of thousands of words.

Collocation cluster length was set at four items (words) to keep the number of clusters manageable, as there were many repetitions of the same words. The minimum frequency was ten. Six clusters were identified with this method, all were associated with the same combination of words.

3.3. Collocate clusters of keyword ITT

The word cluster collocations around the keyword ITT demonstrate a strong pattern of intertextual referencing. In this case, collocations reference other education policy documents within the MCEP and self-reference its own title.

The results (presented in Table ) showed that ITT co-occurs with high relative frequency with the terms’ core content’, “framework for core content” and “framework for ITT”. This reflects the use of the title “Core Content Framework for ITT” (CCF), which is the name of a document issued in Citation2016 , updated and reissued with the same title in Citation2019 following a call for a common curriculum core for ITT programmes in the Carter review of ITT Citation2015.

Table 1. Collocate clusters of keyword “ITT”

As such, this keyword of ITT and its close alignment with the terms Core Content and Framework reflects the intertextual and self-referential terminology evident across the MCEP. The frequency and consistency of this lexical bundle reflects explicit language use to build and assert authority through the repeated use of this terminology.

3.4. Collocates to keyword ‘ITT’

Where collocate words appeared less than twenty times or in less than three texts, they were excluded from the analysis, as data were insufficient to calculate a relationship between the collocate and keyword.

The same pattern of terms appears in the collocation analysis as in the concordance, with a high number of intertextual and self-referential words appearing. As the keyword “ITT” is an abbreviation of “Initial Teacher Training”, we observe a high frequency of the terms Initial, Teacher and Training and “Core Content Framework” regularly occurring in the MCEP.

Collocation can be examined in several ways; a simple frequency count of words co-occurring with a keyword is a simple measure that can be used to inform measures of relationships. In addition, we can calculate the association between collocates and KW by calculating a Dice coefficient or Z number. Both the Z number and Dice are reported in Table to demonstrate the magnitude of the relationship between keyword ITT and its collocates.

Table 2. Collocates to keyword “ITT”

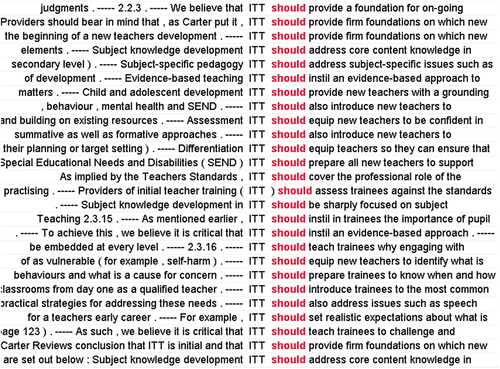

In , the word “Should” has a strong relationship with the keyword ITT. In the concordance analysis, the keywords’ ITT’ and ‘Should ‘appear together, demonstrating the instructional nature of the texts in the MCEP corpus. “Should” is not merely an encouragement in this corpus but an example of deontic modality. In linguistics, the deontic modality is directive. The magnitude of how directive the language use is, can be explored through the frequency of imperative terms like should and conjunctions with terms like “must”. In examining the concordance data, we can observe the high frequency of the words ITT and should as direct, instructional language. This use of the explicitly directive modality represents a shift towards obligation and permission, where epistemic modalities (recognisable through terms that indicate possibility or prediction) have been replaced with regulatory and directive language. Figure demonstrates the co-occurrence data of KW: ITT and “Should”.

Figure 2. Concordance example keyword “ITT” and “should” in the MCEP corpus.

3.5. Concordance example ‘ITT’ and ‘should’ in the MCEP corpus

This use of the deontic modality is also explicitly evident in the phrasing of the CCF strands “Learn that … ” and “Learn how … ”. The use of deontic modality is a feature of the linguistic practice of creating “assumed consensus”. Levitas (Citation1999) argued that such linguistic practices indicate the socio-semiotic activity of turning opinion into fact.

3.6. The discursive construction of the keyword ‘Trainee(s)’ in the MCEP

The keyword “Trainee” appeared 1.5 times per thousand words (n 412 times) in the MCEP, which is a high relative frequency. This contrasts with the EPC comparison corpus where the term trainee occurred 0.05 ptw (n 71 times). The three measures of keyness confirmed “Trainee” to be a keyword for our analysis [BIC score 1173.7; Log L 1188.13; Log R 5.05].

“Trainees” plural did not appear as a KW in the MCEP analysis, but rather than treating the two terms differently in analyses of the two corpora “, Trainee” and “Trainees” were lemmatised for consistency. Concordances were computed to examine the use of the word Trainee(s) in the focus and reference corpus. The concordances were examined in terms of patterns, clusters and context (in sentence) to examine the discourse constructing the term “Trainee(s)” in the two collections of education policy.

3.7. Collocate clusters

Cluster length was set at four as too few clusters could be found for longer word combinations (clusters). The minimum frequency was set at ten. Only one cluster was found, “Trainee Teacher”, which occurred 15 times, see Table .

Table 3. Collocate clusters of keyword “Trainee”

3.8. Collocate clusters of the keyword ‘Trainee(s)’

Collocates are words which appear close to the keyword. Patterns of collocation help us examine a term’s construction in the context of a sentence. The pattern of collocates in relation to the KW Trainee(s) were the words Teacher (15), Teachers (10) and Support (8). The data for collocation words Teachers and Support with the keyword “Trainee(s)” were insufficient to calculate association data. For the word Teacher, the low frequency means that exploration of the data should be treated with caution, so association data will not be reported here. In order to examine the use of the term “Trainee(s)” in the MCEP further (despite its low frequency), its use was contrasted with the use of the term “Trainee(s)” in the reference corpus (the EPC). This offered the opportunity to compare the different constructions of the term “Trainee” in the focus and reference corpus.

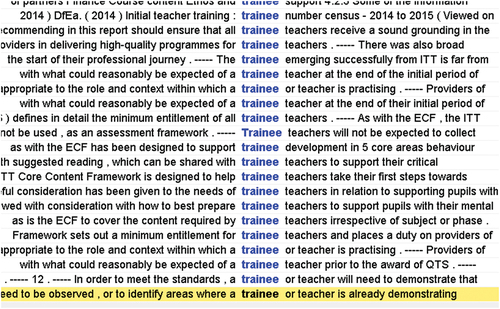

In the MCEP example in Figure we can observe the keyword Trainee(s) used in relation to “Trainee teacher” and in combination with the terms“a”, “the”and “all”.

Figure 3. Concordance example keyword “Trainee(s)” in the MCEP corpus.

3.9. Concordance example ‘Trainee(s)’ in the MCEP

In the MCEP concordance, the positioning of “trainee(s)” is as a “unit” of training- that is, the subject of the programme of training. Trainee(s) are constructed as a homogenous unit: the “trainee” as the subject of the training process, a “product” of a process, but not a person, with individual characteristics.

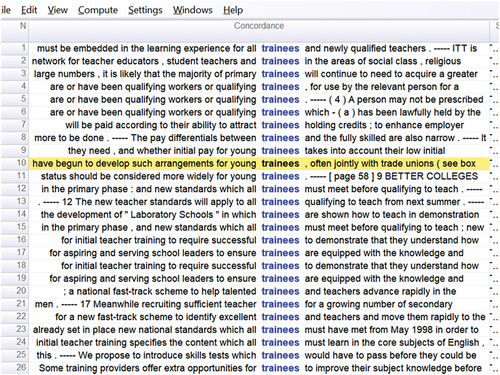

In the EPC, we see adjectival collocates, adjectives combined with the term “Trainee(s)” to describe various features of trainee teachers as persons, from their age to their differing performances on training programmes. For example, in the EPC sample, the terms qualifying, young, successful, talented, and excellent are associated with the keyword “trainee”.

In the example in Figure , “trainee(s)” in the EPC are still the subject of training and are positioned as the subject of policymaking and regulatory discourse- but the use of adjectives in association with the term trainee(s) identifies some different characteristics, and for some human subjectivity to remain. In the EPC, trainees are not merely the product of the training process.

Figure 4. Concordance example “Trainee(s)” in the EP Corpus.

In the comparison of the use of Trainee (s) in the two corpora, a shift is observable in language use between the older policy corpus (EPC) and the recent policy corpus (MCEP). The EPC featured adjectival collocates, which identify characteristics of trainee teachers, whereas the MCEP used directive terms which address Trainee (s) as a homogenous unit without human characteristics. This demonstrates a shift in focus, depersonalising teacher education policy and moving towards a process orientation.

3.10. Summary of corpus results

The corpus-based analysis identified two keywords: ITT and Trainee. These were explored using collocation, clustering and concordance. ITT appeared with the word “should”, emphasising the directive nature of the MCEP. Repeated intertextual references appeared with the term ITT where the documents 'self-referenced’ related policy documents; this created a sense of the “authoritative” nature of the policies and enhanced the directive tone of the MCEP. The term Trainee(s) was also identified as a keyword, and there was a difference in the way this appeared in the two corpora, with the EPC making featuring adjectival collocates; the use of humanising descriptive adjectives which related to characteristics like age (“young”) or differential performance (“excellent”) during training. In the MCEP, the keyword trainee appears with determiners such as “the” or “all” this highlighted the construction of trainee teachers as a homogeneous unit and served to emphasise the primacy of “process” in the MCEP construction of teacher education.

3.11. Identifying discourses in the MCEP

Discourse analysis takes us beyond the analysis of the data used in corpus linguistics and moves us to shift towards a consideration of social semiotics. Social semiotic activity explores the wider codes of language and communication within social structures or processes; in essence, discourses are about the social construction of meaning. The discourse analysis in this project used a line-by-line analysis of the KW concordances and identified overall discursive themes. Two interlinked themes emerged in this exploration of discourses: Governance (Control) and Marketisation (Choice). The discourses which emerged from both the corpus analysis and a line-by-line analysis of themes highlighted national policy approaches in English education policy, which reflect wider international trends in the Global Education Reform Movement (GERM).

3.12. Governance and the language of control

The language of regulation is an explicit feature of all education policy (because the purpose of policy is to regulate), so it is not surprising to see the overall discursive theme of “governance” discourse appear in this analysis.

Regulating discourse in the MCEP has some distinct legislative and rhetorical features: multiple interlinking regulatory frameworks to enforce compliance and the use of imperatives and intertextuality (self-referencing) to assert authority. In combination, this pattern of regulation and rhetoric creates a sense of inevitability in the control of teaching.

Regulatory frameworks introduced by the modern conservative government contain, constrain and control their areas of focus. The first example of this regulatory framing is the Teachers Standards (2011). These standards outline professional standards for qualified teachers working in English schools. They are also a means of regulating the qualification of initial trainee teachers’ performance (trainees are assessed against these standards at the end of the training period) and to establish professional mis/conduct (Teaching Regulation Authority, Citation2022). As Smith (Citation2013) noted, these Teacher Standards (Citation2011) reflect a shift in policy stance from a previous focus on competencies to an emphasis on standards. The second regulatory framework of relevance in this discussion is the ITT Core Content Framework or CCF (Department for Education, Citation2016,Citation2019), which outlines “standards” for core content for initial training. Third, the Early Career Framework (ECF) sets out standards for further professional development for teachers in their early careers. In the shift towards “standards,” consensus is asserted, and room for debate is removed- standards imply a technical certitude about teaching. As Allais (Citation2010) points out, standards are not (despite this language) empirically derived. The interpenetration of discourses (interdiscursivity) of governance and marketisation are examples of policy steering, or in Hyatt’s (Citation2013) terms these discourse act as policy levers.

The interlocking regulatory frameworks above form a policy body (Gillborn & Youdell, Citation2000) that defines and regulates all stages of teacher professional performance. As statutory guidance, much, if not all, of these frameworks contain legally enforceable guidance.

“All ITT programmes involve an accredited provider that must demonstrate compliance in relation to the statutory ITT criteria and provide training that enables trainees to meet the Teachers Standards.” [108]

This level of explicit governance rhetoric is a powerful policy strategy. Modern Conservative education policy in relation to teachers and teaching has created an inexorable wall of regulation. Beck (Citation2009) identified that much of this regulation is reductive and technicised. In this raft of frameworks, there is no room to consider the role of professional judgement, consideration of context (Biesta et al., Citation2021; Biesta, Citation2012) nor differences in subject-specific professional knowledge or skills, nor is nuance offered concerning diversity in the age or stage of education where teachers are working, let alone diversity in terms of pupils. Bacchi (Citation2012) would refer to these omissions as silences.

Ball (Citation2015) has written extensively about the role of regulation in teaching and its impact on teacher behaviour and school culture. In the analysis of this project, we see evidence of both explicit regulation Citation2019, Citation2022 and self-regulation or what Foucault calls governmentality. “Governmentality is not just about national and local political control, but also refers to the self, so is also how and why the self shapes its own conduct in particular ways.” (Perryman et al., Citation2017., p 748). The use of managerial language fosters self-regulation in the form of governmentality, using references to “standards” and quality to encourage judgement and self-judgement. The MCEP data offers many examples of managerial language, audit culture (Apple, Citation2004) or, as Evans (Citation2011) has it, “discourses of administration” within this regulatory discourse. In the examples (below), we see the terms compliance and quality assurance appear:

“All ITT programmes involve an accredited provider that must demonstrate compliance in relation to the statutory ITT criteria and provide training that enables trainees to meet the Teachers Standards.” [108]

“The ITT criteria cover issues such as recruitment, training and quality assurance.” [110]

This managerial terminology reveals a technicist approach to initial teacher training (ITT), with regulatory control, compliance, quality standards and the teacher development process described as something of a “production line”. As such, it demonstrates the explicit regulatory power of the policies and the deontic modality of the language surrounding this regulation. The language of control is evident in the use of “must” and the unchallenged establishment of practices that implicitly reinforce these power relations. We can see specific examples of normalising discourse utilising the language of “quality” (evoked evaluation) where consensus is assumed (presupposition).

In the corpus analysis, the use of the imperative form “Should” was identified as a linguistic pattern to assert authority. In this wider exploration of discourse, we see how this links into a broader establishment of regulatory standards as “norms” to support not only top-down government and explicit regulation but also to encourage self-governance and the assertion of authority.

An additional feature of this wider theme of the assertion of power and control is the use of intertextuality to increase the legitimacy of policy. The analysis of the MCEP identified the practice of intertextual and intratextual referencing within the documents in the corpus. This linguistic practice of referencing “authoritative” sources builds the text’s authority and reinforces the authority of the texts being so referenced. As such, it is an “establishing” practice which asserts and reifies authority:

“The fundamental aim of the framework of core content is to ensure that ITT programmes enable trainees to meet the Teachers Standards in full at the level appropriate to the end of a period of initial teacher training.” [388]

“In line with the Carter review’s recommendation, the aim of the framework is: To support those who deliver ITT and applicants and trainees to have a better understanding of the essential elements of good ITT core content.” [425]

Governmental authority is established in regulatory discourses in the MCEP through the explicit establishment of regulatory standards and the use of intertextual references to reinforce the authority of the policies, by each repeatedly referring to the authority of the other. Regulatory discourse is reinforced implicitly via assumed consensus (presupposition) through the language of standards and quality, encouraging self-regulation (governmentality). The explicit and implicit regulatory discourse through the MCEP creates an inexorable wall of regulation asserting power (the power of government) and control (regulation and self-regulation).

3.13. Marketisation of education and the language of ‘choice’

The second discursive theme that makes the MCEP distinct from the EPC is marketisation, the explicit use of market or economic language in relation to initial teacher training. The fragmentation of ITT provision noted by Whiting et al. (Citation2018) is evident in the MCEP’s frequent consideration of providers within the “ITT system”. The word “system” features as a collocate of keyword ITT in the MCEP, it features 26 times (which is statistically significant, see Table ). In the EPC the word “system” and ITT feature together 0 times.

In the theme of marketisation, we also note the discussion of “informed choices” within ITT and the emphasis on ITT as a process, with “trainees” featuring in this marketised conceptualisation of ITT as both consumers and as a product. In the MCEP, increasing use of economic language and models concerning the ITT’ Market’ can be observed, for example:

“It is important that all schools are able to access information about how to get involved with ITT to improve choice in the system.” [85]

“To recommend ways to improve choice in the ITT system by improving the transparency of course content” [95]

“Applicants must have access to clear and available information about routes into teaching and the range of courses available in order for them to be intelligent consumers of ITT provision.” [318]

“We believe that applicants should be making informed choices about their ITT programmes” [321]

The word “consumer(s)” occurs in concordance with ITT 5 times in the MCEP and 0 times in the EPC. The word “choice” features in concordance with ITT 13 times in the MCEP and 0 times in the EPC. This demonstrates the difference between the two corpora in their construction of ITT. Interest in “choice” within initial teacher education is a feature of a particular neoliberal conception of education, where competition within the market is dominant (Apple, Citation2005). Mulderrig (Citation2008) calls this “systematic competitiveness”, noting that education in England has been specifically structured to create a “competitive market” where providers compete for teacher training applicants.

In addition to the role of the “consumer” of ITT, in the analysis of the MCEP data, the role of “Trainee” as “product” was apparent. The corpus analysis of the MCEP identified a depersonalised and homogenous treatment of the KW “Trainee”, distinct from the wider EPC.

The discourse of marketisation in the modern conservative education policy corpus is constructed from several subtle strands. The language of choice, the conception of the system of ITT as a competitive marketplace where consumers of the ITT’ product’ (that is, teacher training programmes) are “consumers” evaluating the quality of products; and simultaneously are the product (of the training process) themselves.

4. Conclusion

4.1. How do education policies in England from 2010–2021 construct teacher education?

The project compared education policy corpora to explore the construction of teacher education in the modern conservative period. Two major interdiscursive themes emerged. The first theme was regulation or governance (control). This explored the language of power and control that dominates the MCEP. The features of this “Control” discourse were the establishment of authority (through intertextual self-referencing), the assertion of normative values (via standards), and language practices (such as the language of quality) which encouraged governmentality (self-government). The theme of control is evident in the corpus-based and critical discourse analyses of the MCEP. The second theme that emerged in the discourse analysis was “marketisation”. The marketisation theme identified distinct language patterns around competition (a “system” of competition between providers), “choice” (for consumers- who are also the product) and a process-product approach to teacher education for example, in the depersonalisation of “trainee(s)”. The marketisation theme is evident in the corpus and discourse analyses. Teacher education in the MCEP is a competitive marketplace system, where the product is both the training and the “trainee” and the “process” is centrally controlled via an extensive policy framework.

4.2. Is this distinct from previous education policies in England?

Yes. In the MCEP, the emerging discourses were demonstrably different from previous education policies in the EPC. Themes of control and choice emerged in the MCEP through policy and language practices. Interlocking policy regulation and statutory guidance, including professional frameworks and standards, are examples of policy practices which regulate teacher education (Stanfield & Cremin, Citation2013). The language practices of authority building through intertextuality, the managerial language of standards and processes, and the deontic modality emphasise authority and control. The use of “should” was identified as a collocate which reflected a directive turn in the policies of the MCEP. This lexico-grammatical construction (using deontic modality) in the MCEP directs and controls action, reducing the agency of those subject to the policies. Corpus-based discourse analysis of the MCEP revealed the depersonalisation of professional training through an emphasis on process rather than people, supporting the arguments of Biesta (Citation2012).

4.3. Are there discourses discoverable through corpus-based discourse analysis of education policies in England that relate to discourses in global education reform?

In this project, the topoi (discourses) revealed through corpus-based CDA of national education policy in England connect to global educational reform themes. This project offers further evidence of reform themes in teacher education policy which connect local policies to international trends. Mooney Simmie and Edling (Citation2019) examine how policy frames teacher education in Ireland and Sweden, identifying the “substantive and converging paradigm shift” (p.843) from a progressivist focus towards an essentialist model. This shift repositions the teacher from an agentive role to a subjective one, or in their terms, into a “technically competent functionary.” (Mooney Simmie & Edling, Citation2019, p.844). These international observations mirror the analysis in this project of the shifting construction of “Trainee” teachers from individuals with adjectival features to a homogenous unit. The analysis in this project also connects to the observation of a shift towards the marketisation of education in Swedish teacher education identified by Rönnberg (Citation2017).

Sahlberg (Citation2011, 2012) drew attention to the alignment of education and economic interests, highlighting that one significant dimension of the global educational reform movement (GERM) is reforming education systems to align with the economic and market practices of private capital. At a local level, in England, this has been characterised as “privatising as state reform” (Verger et al., Citation2016, p. 7). The new analysis in this project- highlighting the rhetoric of “choice” supports this argument that through policy discourse (and accompanying reform in practice), we can observe a change in the balance of contributions between public and private actors in education (Macbeath, Citation2011,Citation2012; Maguire, Citation2014).

Darling-Hammond and Lieberman (Citation2012) and Cochran-Smith (Citation2016) observed significant policy intervention to reform teacher education in England. This project sought to examine the nature of this reform through a critical analysis of the text and subtext of the policy documents involved. The findings of this project exemplify themes observed elsewhere in analyses of the global education reform movement (GERM). The theme of governance and regulation explored power and control through explicit and implicit legislative and language practices in the MCEP corpus. The theme of marketisation emerged through the language of choice and competition, which is linked to a neoliberal conception of education (Apple, Citation2005). The analysis contributes specific examples to support the understanding of the problematisation of teacher education (Biesta, Citation2021) and its current construction (Furlong, Cochran-smith & Brennan, Citation2009).

Policymakers should be alert to the risks of policy borrowing and global agendas exerting undue influence on national education policies (Ball, Citation2012). The effects of this influence amplify reductive and technicist conceptions of education (Beck, Citation2009), advance the interests of international edu-business and silence context-sensitive and nuanced approaches to education and teacher preparation, which involve professional judgment (Biesta, Citation2012). Policy makers should consider whether global solutions are the most effective response to local, context specific challenges. What might the unintended consequences of a de-skilled and disenfranchised workforce of teachers be for education and society?

Teacher education in the UK and beyond faces significant changes and major challenges. This work identified discourses connecting national policy to global reform trends. This methodology could be used in future works to map out further topoi in the global education reform movement to understand better the patterns of influence and interest shaping policy and practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Academies Act, (2010) https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/32/contents

- Allais, S. (2010). The implementation and impact of national qualifications frameworks: Report of a study in 16 countries, International Labour Office,

- Apple, M. W. (2004). Creating difference: Neo-liberalism, neo-conservatism and the politics of educational reform. Educational Policy, 18(1), 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904803260022

- Apple, M. W. (2005). Education, markets, and an audit culture. Critical Quarterly, 47(1 –2), 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0011-1562.2005.00611.x

- Bacchi, C. (2012). Introducing the ‘What’s the problem represented to be?’ approach. In A. Bletsas, C. Beasley (Eds.), Engaging with carol bacchi: Strategic interventions and exchanges (pp. 21–24). University of Adelaide Press.

- Baker, P. (2004). Querying Keywords: Questions of difference, frequency and sense in keyword analysis. Journal of English Linguistics, 32(4), 346–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424204269894

- Baker, P., Gabrielatos,C., Khosravihik, M., Krzyzanowski, M., McEnery, A. & Wodak, R. (2008). A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse & Society, 19(3), 273–305.

- Ball, S. J. (1994). Education Reform: A critical and post-structural approach. Open University Press.

- Ball, S. J. (2012). Global education inc: New policy networks and the neo-liberal imaginary. Routledge.

- Ball, S. J. (2015). What is policy? 21 years later: Reflections on the possibilities of policy research. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(3), 306–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1015279

- Balloten, B. (2011). Axing the Education Maintenance Allowance: Rationing provision and increasing inequality.Race Equality Teaching,29(3), 8–11.

- Barber, M., & Mourshed, M. (2007). How the world’s best-performing school systems come out on top. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/social-sector/our-insights/how-the-worlds-best-performing-school-systems-come-out-on-top#

- Beck, J. (2009). Appropriating professionalism: Restructuring the official knowledge base of England’s ‘modernised’ teaching profession. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 30(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690802514268

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2012). Giving teaching back to education: Responding to the disappearance of the teacher. Phenomenology & Practice, 6(2), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.29173/pandpr19860

- Biesta, G., Takayama, K., Kettle, M., & Heimans, S. (2021). Teacher education policy: Part of the solution or part of the problem? Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 49(5), 467–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2021.1992926

- British Educational Research Association (BERA). (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational Research. https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018

- Burch, L. F. (2018). Governmentality of adulthood: a critical discourse analysis of the 2014 special educational needs and disability code of practice. Disability & Society, 33(1), 94–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1383231

- Carter, A. (2015). Carter review of initial teacher training (ITT). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/399957/Carter_Review.pdf

- Cochran‐smith, M., & Fries, M. K. (2002). The discourse of reform in teacher education: Extending the dialogue. Educational Researcher, 31(6), 26–29.

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2016). ‘Foreword’ in teacher education group teacher education in times of change. Policy Press.

- Crawford-Garrett, K., & Thomas, M. (2018). Teacher education and the global impact of teach for all. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-417

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Lieberman, A. (Eds.). (2012). Teacher education around the world: Changing policies and practices. Routledge.

- Department for Education. (2010). The importance of teaching: The schools white paper.

- Department for Education. (2011). Teachers’ standards. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/teachers-standards

- Department for Education. (2016) . A framework of core content for initial teacher training (ITT). Crown publishing.

- Department for Education. (2019). ITT Core Content Framework. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/attachment_data/file/843676/Initial_teacher_training_core_content_framework.pdf

- Evans, A. M. (2011). Governing student assessment: Administrative rules, silenced academics and performing students. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(2), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903277727

- Fairclough, N., Mulderrig, J., & Wodak, R. (2011). Critical discourse analysis. In T. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse studies: A Multidisciplinary introduction (pp. 357–378). Sage.

- Finn, M. (Ed.). (2015). The gove legacy: Education in Britain after the coalition. Springer.

- Furlong, J., Cochran-Smith, M., & Brennan, M. (2009). Policy and politics in teacher education: International perspectives. Routledge.

- Gabrielatos, C. (2018). Keyness Analysis: Nature, metrics and techniques. In Corpus approaches to discourse: A critical review. Routledge.

- Gabrielatos, C., & Marchi, A. (2012). Keywords: Appropriate metrics and practical issues. CADS International Conference. http://repository.edgehill.ac.uk4196

- Gillborn, D., & Youdell, D. (2000). Rationing education: Policy, practice, reform, and equity. Open University Press.

- Halliday, M. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. Edward Arnold.

- Hardie, A. (2014). Log Ratio- an informal introduction. http://cass.lancs.ac.uk/?p=1133

- Hartung, C. (2017). Global citizenship incorporated: Competing responsibilities in the education of global citizens. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 38(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1104849

- Hilton, A. (2018). Academies and free schools in England: A History and philosophy of the gove act. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429468995

- Hyatt, D. (2013). The critical policy discourse analysis frame: Helping doctoral students engage with the educational policy analysis. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(8), 833–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.795935

- Intellectual Property Office. (2014). Changes to copyright law, Exceptions to copyright: Research. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/changes-to-copyright-law

- Kauko, J. (2022). Politics of evidence: Think tanks and the academies act. British Educational Research Journal, 00, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3824

- Levitas, R. (1999). The concept of social exclusion and the new Durkheimian hegemony. Critical Social Policy, 16(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/026101839601604601

- Macbeath, J. (2011). Education of teachers: The English experience. Journal of Education for Teaching, 37(4), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2011.610988

- Macbeath, J. (2012). Future of Teaching Profession. Faculty of Education, Cambridge University. www.ei-ie.org

- Maguire, M. (2014). Reforming teacher education in England: ‘an economy of discourses of truth’. Journal of Education Policy, 29(6), 774–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2014.887784

- Mayer, D. (2021). The connections and disconnections between teacher education policy and research: Reframing evidence. Oxford Review of Education, 47(1), 120–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1842179

- Menter, I. (2019). The interaction of global and national influences. In M. T. Tatto & I. Menter (Eds.), Knowledge. Policy and Practice in Teacher Education (pp. 268–279). Bloomsbury.

- Mooney Simmie, G., & Edling, S. (2019). Teachers’ democratic assignment: A critical discourse analysis of teacher education policies in Ireland and Sweden. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(6), 6, 832–846. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2018.1449733

- Mulderrig, J. (2008). Using Keywords analysis in CDA: Evolving discourses of the knowledge economy in education. In B. Jessop, N. Fairclough, & R. Wodak (Eds.), Knowledge-based economy in Europe (pp. 149–170). Sense.

- Mulderrig, J. (2011). Manufacturing Consent: A corpus-based critical discourse analysis of New Labour’s educational governance. Journal of Educational Philosophy and Theory, 43(6), 562–578. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2010.00723.x

- Mulderrig, J. (2012). The hegemony of inclusion: A corpus-based critical discourse analysis of deixis in education policy. Discourse & Society, 23(6), 701–728. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926512455377

- Mulderrig, J. M. (2014). Enabling participatory governance in education: A corpus-based critical analysis of policy in the United Kingdom. In P. Smyers, D. Bridges, N. Burbules, & M. Griffiths Eds., International handbook of interpretation in educational research. ISBN 9789401792813 (p. 1–470p. 1–470). Springer International Handbooks of EducationSpringer International Handbooks of Education.

- Ofsted. (2019). The Education Inspection Framework. 2005 (May), 1–14. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/

- Ofsted. (2022) Initial Teacher Education (ITE) inspection framework and handbook. February. 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/initial-teacher-education-ite-inspection-framework-and-handbook/initial-teacher-education-ite-inspection-framework-and-handbook#annex-a–instructions-and-guidance-for-thematic-subject-inspections

- Olmedo, A., Bailey, P. L. J., & Ball, S. J. (2013). To infinity and beyond …: hierarchical governance, the teach for all network in Europe and the making of profits and minds. European Educational Research Journal, 12(4), 492–512. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2013.12.4.492

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2005). Teachers Matter: Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers. OECD Publications. https://www.oecd.org/education/school/34990905.pdf

- Perryman, J., Ball, S. J., Braun, A., & Maguire, M. (2017). Translating policy: Governmentality and the reflective teacher. Journal of Education Policy, 32(6), 745–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1309072

- Pratt, N. (2016). Neoliberalism and the (internal) marketisation of primary school assessment in England. British Educational Research Journal, 42(5), 890–905. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3233

- Rönnberg, L. (2017). From national policymaking to global edu-business: Swedish edu-preneurs on the move. Journal of Education Policy, 32(2), 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1268725

- Sahlberg, P. (2011). Finnish lessons: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland?. Teachers College Press.

- Sahlberg, P. (2012). How GERM is infecting schools around the world? Retrieved from https://pasisahlberg.com/text-test/

- Scott, M. (2020). WordSmith Tools version 8. Lexical Analysis Software.

- Sinclair, J. (2005). Corpus and text - basic principles. In M. Wynne (Ed.), Developing linguistic corpora: A guide to good practice (pp. 1–16). Oxbow Books.

- Smith, H. J. (2013). A critique of the teaching standards in England (1984–2012): Discourses of equality and maintaining the status quo. Journal of Education Policy, 28(4), 427–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.742931

- Spicksley, K. (2022). The very best generation of teachers ever: Teachers in post-2010 ministerial speeches. Journal of Education Policy, 37(4), 655–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1866216

- Stanfield, J., & Cremin, H. (2013). Importing control in initial teacher training: theorising the Construction of Specific Habitus in Recent Proposals for Induction into Teaching. Journal of Education Policy, 28(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.682608

- Taylor, S. (1997). Critical Policy Analysis: Exploring contexts, texts and consequences. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 18(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/0159630970180102

- Teaching Regulation Agency. (2022) . Teacher misconduct: The prohibition of teachers, Advice on factors leading to the prohibition of teachers from the teaching profession (TRA-00114-2018). Crown Copyright.

- Verger, A., Fontdevila, C., & Zancajo, A. (2016).The Privatization of Education: A political economy of global education reform. Teachers College Press, New York.

- Whiting, C., Whitty, G., Menter, I., Black, P., Hordern, J., Parfitt, A., Reynolds, K., & Sorensen, N. (2018). Diversity and complexity: Becoming a teacher in England in 2015-16. Review of Education, 6(1), 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3108

- Wright, A. (2012). Fantasies of empowerment: Mapping neoliberal discourse in the coalition government’s schools policy. Journal of Education Policy, 27(3), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2011.607516

Appendix

Teacher education policy corpus

Data accessibility statement

BERA ethical guidelines (BERA Citation2018) were followed throughout this research project.

The dataset which was collected and analysed for this study consisted solely of publicly accessible, published texts and involves no contact with human subjects.

The data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain:

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-education

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/search/results/?_q=education+policy

Additional relevant information

The UK Intellectual Property Office (Citation2014) introduced a new copyright exception in 2014 for any material which is copyrighted for text and data mining for non-commercial research purposes. The exception covers using material for the purpose of computational analysis if the material is lawfully accessed. This exception states that researchers are allowed to make copies of any copyright material for the purpose of computational analysis if they already have the right to read the work (that is, work that they have “lawful access” to). They will be able to do this without having to obtain additional permission to make these copies from the rights holder (Intellectual Property Office, Citation2014, p. 6).

Data access request

The licensing agreement for the corpus analysis software does not allow the license holder to share access to the corpora constructed using the software.